Abstract

Background:

A substantial portion of child deaths take place in countries with recent history of armed conflict and political instability. However, the extent to which armed conflict is an important cause of child mortality, especially in Africa, remains unknown.

Methods:

Using information on (1) geocoded location, timing, and intensity of armed conflicts and (2) the location, timing, and survival of under-1 and under-5 children in 35 African countries from 1995 to 2015, we matched child survival with proximity to armed conflict. We measured the increase in mortality risk for children exposed to armed conflicts within 50km in the year of birth and, to study conflicts’ extended health risks, up to 250km away and 10 years prior to birth. We also examined the effects of conflicts of varying intensity and chronicity (conflicts lasting several years), and effect heterogeneity by residence and child sex. We then estimate the number and portion of under-1 and under-5 deaths related to conflict.

Findings:

We analyzed 15,441 armed conflict events that led to 968,444 armed conflict deaths, 1.99 million births, and 133,361 infant deaths (infant mortality rate of 67 deaths per 1,000 births). A child born within 50km of an armed conflict had a risk of dying before reaching age one of 5.2 per 1,000 births higher than being born in the same region during periods without conflict (95% CI 3.7-6.7; a 7.7% increase above baseline). This ranged from 3.0% increase for armed conflicts with 1-4 deaths to 26.7% increase for armed conflicts with >1,000 deaths. We find evidence of increased mortality risk from an armed conflict up to 100km away, and for 8 years after conflicts, with cumulative increase in infant mortality 2-4 times higher than the contemporaneous increase. In the entire continent, the number of infant deaths related to conflict from 1995 to 2015 were between 3.2 and 3.6 times the number of direct deaths from armed conflicts.

Conclusions:

Child mortality in Africa is substantially and sustainably increased in times of armed conflict, on a scale with malnutrition, and several times greater than existing estimates of conflict’s effects. The toll of conflict on children, all presumably non-combatants, underscores the indirect toll of conflict on civilian populations, and the importance of developing interventions to address child health in areas of conflict.

Introduction

The extent to which armed conflicts – events such as civil wars, rebellions, and interstate conflicts – are an important driver of child mortality is unclear. While young children are rarely direct combatants in armed conflict, the violent and destructive nature of such events might harm vulnerable populations residing in conflict-affected areas.1,2 A recent review estimates that deaths of non-combatants outnumber deaths of those directly involved in the conflict, often more than five-to-one.3 At the same time, national child mortality rates continue to decline, even in highly conflict-prone countries such as Angola or the Democratic Republic of the Congo.4 With few notable exceptions, such as the Rwanda genocide or the ongoing Syrian Civil War, conflicts have not had clear reflections in national child mortality trends.5-7 The Global Burden of Disease estimates that, since 1994, conflicts caused less than 0.4% of under-5 deaths in Africa, raising questions about the role of conflict in the global epidemiology of child mortality.8

The extent to which conflict matters to child mortality therefore remains largely unmeasured beyond specific conflicts.9-11 In Africa, conflict-prone countries also have some of the highest child mortality rates, but this may be a reflection of generalized under-development resulting in proneness to conflict as well as high child mortality rates, rather than a direct relationship.12 In this analysis we aim to shed new light on the effects of armed conflict on child mortality. We establish the effects on child mortality of armed conflict in whom conflict-related deaths are not the result of active involvement in conflict, but of other consequences of conflict. We examine the duration of lingering conflict effects, and the geographical breadth of the observed effects, using geospatially explicit information on conflict location and number of conflict-related casualties. We then use our findings to estimate the burden of armed conflict on under-1 and under-5 children in Africa.

We use a dataset of geospatially explicit information on armed conflict in Africa, including location, timing, and number of armed conflict deaths. These data have been used primarily in political science to study features of armed conflict, such as why armed conflicts erupt or end and the role of state and non-state participants in conflict.13,14 The availability of location and timing, however, enables identification of the relationship with location and timing of child births and deaths. We use this identification throughout this analysis. Recognizing the extent to which armed conflicts spill over to jeopardize the lives of young children would help prioritize approaches to deliver critical services and other protective measures to populations living in unstable areas.

Methods

Overview

This analysis proceeds in several stages. We first estimate the relationship between armed conflict and child mortality. We examine the mortality response of infants (children under the age of 1) to the intensity and duration of nearby armed conflicts. We then present a series of extended analyses on the long-term destructive effects of conflict, on the spatial limits of conflict’s effects, on possible mechanisms leading from conflict to child mortality, and on the mortality implications for children up to age 5. Finally we use these findings to project the portion and number of under-5 and under-1 deaths related to armed conflict across the entire continent. Below we detail our primary data sources and empirical strategies.

Conflict Data

Our primary data on armed conflict comes from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program Georeferenced Events Dataset (UCDP GED).15,16 The UCDP GED includes detailed information about the time, location, type, and intensity of conflict events from 1946 to 2016 (exact location available from 1989). A distinctive feature of this dataset is that it was created for research purposes and includes a stringent definition of conflict events. An event is defined as “the incidence of the use of armed force by an organized actor against another organized actor, or against civilians, resulting in at least 1 direct death in either the best, low or high estimate categories at a specific location and for a specific temporal duration.”17 The data is collected using a standardized process where potential events are identified from news sources, NGO reports, case studies, truth commission reports, historical archives and other sources of information.17,18 Potential events are then triple-read, coded, and subjected to data quality checks.16 Where conflicts took place is determined using the conflict source information, and the process is described with UCDP GED documentation.13,16 We use all conflict events with at least one armed conflict death in the UCDP’s best estimates of the number deaths from 1989 to 2015.

The only alternative with a scope approaching that of UCDP GED is the Armed Conflict Location Events Dataset (ACLED).19 The ACLED has a more limited time span, and in addition was found to be more prone to data quality concerns and inconsistent sub-national coding in comparison with UCDP GED.13 As a result, we use UCDP GED in the primary analyses and show results with ACLED in the Appendix.

Child Mortality Data

We used all available Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in African countries from 1995-2015 as the primary data sources on child mortality in this analysis. The DHS are nationally representative surveys that are conducted in many low-income and middle-income countries.20,21 We used all surveys with individual-level information on child survival and geospatial information.22 In geo-referenced surveys, enumerators use global positioning system (GPS) devices to identify the central point of each cluster’s populated area (a cluster is analogous to a village or a neighborhood). These coordinates are displaced by up to 2 km in urban clusters, 5 km in 99% of rural clusters, and 10 km in a random sample of 1% of rural clusters.23 We used 105 surveys carried out in 35 African countries between 1995 and 2015, which contained data on 45,815 clusters, including the location and timing of 1.99 million births, 133,361 under-1 deaths and 204,101 under-5 deaths. We created a child-level indicator of whether or not the child survived his or her first year of life, which we use as our primary outcome in all under-1 analyses. As a secondary outcome, we use the child’s height-for-age (children must have been alive during the survey) to create an indicator for whether or not the child’s growth was stunted (two standard deviations below the median of the NCHS/WHO growth reference).24 All births and deaths were assigned to the cluster’s GPS location at the time of the survey. However, because conflict may induce migration and displacement, we tested this assumption in sensitivity analyses (below).

Estimation Framework

Our empirical approaches exploit the longitudinal aspect of the information from each DHS cluster, and do not depend on cross-sectional differences. We estimate conflicts’ effects by comparing death probabilities associated with infant outcomes within the same DHS cluster over time. In doing that we control for all stable cross-sectional differences between DHS clusters. In other words, our models answer the question “what does infant mortality look like in cluster A during times of conflict compared with times without conflict?” and not the question “what does infant mortality look like in cluster A near a conflict compared with cluster B that is not near a conflict?” We model the relationship between armed conflict and child mortality using the following linear probability models:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where y – an indicator that equals 1 if the child did not survive his or her first year of life and 0 otherwise – is indexed for child i, cluster l, country c, birth month (January-December) m, and year of birth t. In secondary analyses, y represents whether or not the child was stunted. The main predictor in eq. (1), Dlct, is an indicator, indexed to the child’s cluster and year, representing whether or not the child was exposed to armed conflict (of any intensity) within 50km during their first year of life. In eq. (2) the main predictors are a vector of indicators, , representing exposure to conflict of intensity q. We classify conflict intensity in two distinct ways. First, the intensity index q represents the quartile of the number of conflict deaths for all conflicts in our data, plus one indicator for conflicts with >1,000 conflict deaths to capture very large conflicts (5 indicators in total). Second, the intensity index q represents the consecutive years of conflict in the child’s cluster leading up to the first year of life (censored at 5 years), which is meant to capture the chronicity of conflict. We estimate the βq terms, which represent the impact of armed conflict exposure of intensity q on under-1 mortality.

We use a series of fixed effects to avoid cross-sectional comparisons, including η (DHS cluster fixed effects), φ (country-month fixed effects), and γ (birth year fixed effects). The DHS cluster fixed effects allow identifying the main effects within each DHS cluster; the country-month fixed effects control for seasonal differences (e.g. “January in Kenya” effects); and the year fixed effects control for shared effects over time (e.g. global component of rising temperatures). Put another way, our models isolate variation in conflict exposure from other time-invariant, seasonal, or time-trending factors that could be correlated with mortality. For instance, by including cluster fixed effects, we use only within-cluster variation in conflict and mortality over time, which controls for all time invariant cross-sectional differences between clusters (e.g. that wealthier – and healthier – villages also have lower conflict). We use a total of 45,815 DHS cluster fixed effects, 410 country-month fixed effects, and 21 year fixed effects (a total of 46,243 indicator variable fixed effects). We use robust standard errors clustered at the level of the DHS cluster throughout (we use the first ‘cluster’ to refer to statistical clustering of the standard errors, and the second to refer to the physical DHS cluster).25

The X represents a vector of child-level, mother-level, or time-varying cluster level controls. This vector includes several variables that, at a local level, could plausibly affect both the risk of conflict as well as child mortality, including average temperature and rainfall (that have been shown to influence conflict incidence), night light luminosity (a correlate of poverty), and food price index (if food insecurity may simultaneously exacerbate conflict risk and infant mortality risk).26-28 We also control for the child’s gender, the mother’s age, and the mother’s education.

In addition to examining the effect of contemporaneous, nearby conflict, we estimate the lagged and distant effects of conflict over time and space. For this analysis, we added temporal and spatial bands to eq. (1). We added 10 time indicators for past conflict, one for each of the 10 years leading up to birth.We then use our findings to estimate the portion and number of under-5 and infant deaths related to conflict. To project the number of deaths from conflict to the entire continent, we use the following procedure. We obtained the number of births in each 0.1 degree latitude by 0.1 degree longitude cell (roughly 10 km × 10 km) in each year, and identified in which cells and years were children born and exposed to armed conflict.29,30 We then use estimates of under-1 and under-5 mortality rate in that grid cell to estimate the number of under-1 and under-5 deaths.31 Next, we apply our coefficients to scale down the under-1 and under-5 mortality rate in exposed cells to what would be expected if there had been no conflict. Finally, we take the difference between the observed number of child deaths and those in the conflict-free counterfactual (see SA3 for more details on this methodology). We show findings for both under-5 and under-1 children.

We conducted multiple robustness checks and extended analyses. In Appendix SA1.1 we show the sensitivity of our findings to the choice of fixed effects and adjustors. We then test the sensitivity of our main estimates to leaving each country out of the analysis, in turn (SA1.2). We also examine the assumption of stable residence. Conflict can force migration such that the location of the women’s interview would be different from the location of the child’s first year of life. To examine this potential bias, we restricted our sample to those mothers who indicated they have lived in the same house for at least 10 years prior to the child’s birth (SA1.3). We then examine our primary models using a different source of conflict data, from ACLED (SA1.4).13 Our last robustness check tests the sensitivity of our findings to the precision of the conflict event location in UCDP (SA1.5).

Our extended analyses focus on testing our observed effects in different populations. We first focus on the mortality effects of conflict (during the year before birth) on neonatal mortality, as a suggestion of conflict’s impacts on maternal health (SA2.1). We then show an analysis of effects on children up to age 5. We discuss our approach to this analysis and the findings in SA2.2. In SA2.3 we show how conflicts of different intensities persist over time. Section SA2.4 shows effect heterogeneity by place of residence (urban and rural) and by child sex (boys and girls). Finally, in section SA2.5 we show the effects by our two measures of intensity – conflict chronicity and deadliness – simultaneously (from short conflicts with few casualties to very prolonged conflicts with 1000+ casualties), and in section SA2.6 we show response of stunting rates to armed conflict.

We used R statistical software for all analysis and statistical code is available upon request.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. ZW and EB had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

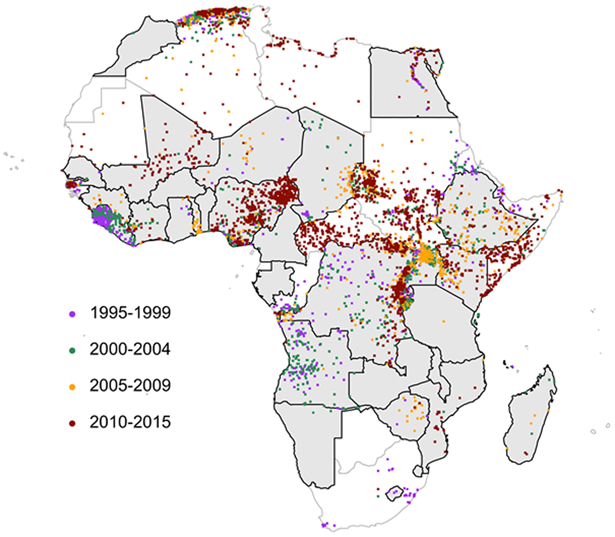

Our data consists of 1.99 million births, 133,361 under-1 deaths, and 204,101 under-5 deaths in 35 countries between years 1995 and 2015. These data were linked to 15,441 armed conflict events with 968,444 conflict-related deaths. Table 1 provides country-level data on the study sample, including information on the number of births, child deaths, and conflict events available for analysis. Figure 1 shows the distribution of armed conflicts recorded in the UCDP GED database between 1995 and 2015, broken into four 5-year periods (Figure S13 shows conflict sizes).

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics (Conflicts)

| Conflict Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of conflicts | Conflict deaths (N) |

Children exposed, N (% of births) |

||

| Total | 15,441 | 968,444 | 252,027 | (12.7%) |

| 1-4 deaths | 8,095 | 16,362 | 69,683 | (3.5%) |

| 5-18 deaths | 4,309 | 40,854 | 57,050 | (2.9%) |

| 19-74 deaths | 2,181 | 76,157 | 62,952 | (3.2%) |

| 75-1000 deaths | 793 | 174,552 | 50,663 | (2.6%) |

| 1001+ deaths | 63 | 660,519 | 11,679 | (0.6%) |

Notes: Conflict data (top portion) from UCDP GED database. Only conflicts to which children in our sample were exposed are included in this table.

Figure 1:

The distribution of armed conflicts in Africa, 1995-2015. The map shows the UCDP conflict location data in the continent, with changing location over time. The study countries are gray with thick borders. The map shows the regional changes in high-density conflicts, as well as the lack of any obvious decline in the frequency of conflict in more recent years.

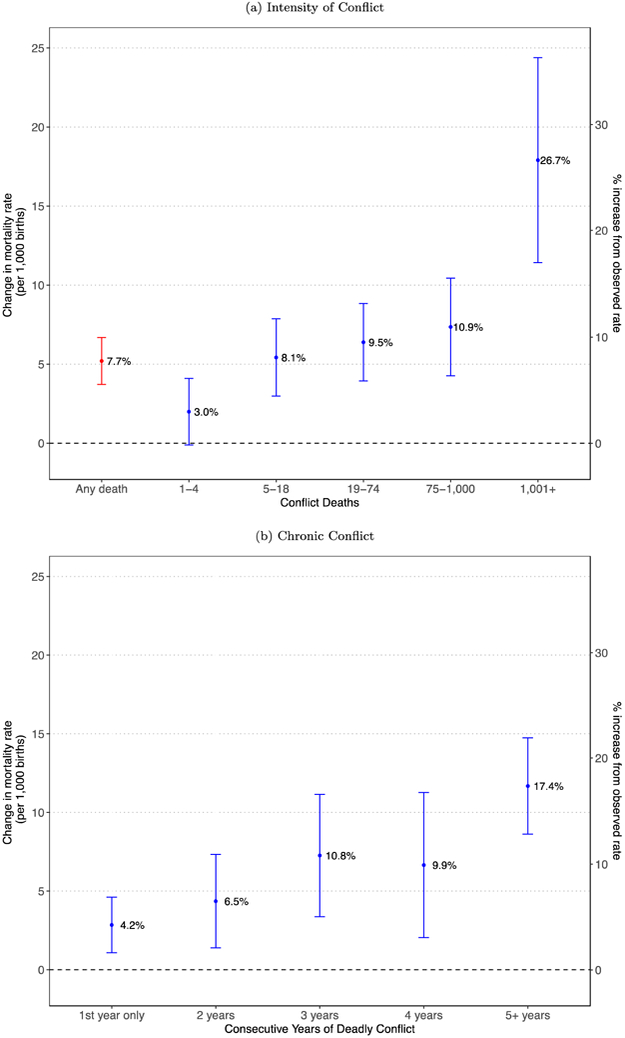

We find a large and significant increase in the probability of dying before reaching age 1 from nearby armed conflict (Figure 2a). The Figure and Table 2 show that deadly conflict within 50km during a child’s first year of life leads to an increase of 5.2 infant deaths per 1,000 births (95% CI 3.7-6.7). Using the observed under-1 mortality rate in our sample (67 deaths per 1,000 births), this represents a 7.7% [5.5%-9.9%] increase in mortality rate. This effect increases with exposure to conflicts with higher intensity: the infant mortality effect size rises by ~75% with each quantile increase in conflict intensity, 2.0 deaths per 1,000 births for conflicts with 1-4 deaths, 5.4 for 5-18 deaths, 6.4 for 19-74, 7.4 for 75-1000, and 17.9 for conflicts with >1000 deaths. Figure 2b also shows that the effects of conflict increase for more chronic conflicts: the impact of conflict lasting 5 or more consecutive years is more than 4-times greater than an unsustained (less than 1 year) conflict in the child’s first year of life (11.7 and 2.8 deaths per 1,000 births, respectively).

Figure 2:

Impact of deadly conflict in first year of life on under-1 mortality. The top panel (Figure 2A) shows the effect of any conflict within 50km of the infant’s cluster (red bar, equation 1), as well as the rising risk from conflicts of increasing intensity (equation 2). The bottom panel (Figure 2B) shows the increasing risk from conflicts of increasing duration. We estimate the exposure based on whether or not the conflict lasted for less than 1 year, 1-2 years, and so on up to 5 or more years of consecutive conflict near the child’s cluster. The left Y axis indicated the increase in mortality risk in deaths per 1,000 births; the right Y axis converts that risk to the percent increase above baseline mortality risk.

Table 2:

Descriptive statistics (Children)

| Child Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Births | Deaths | Rate | |

| Total | 1,985,109 | 133,361 | 67.18 |

| Conflict in first year of life? | |||

| Yes | 252,027 | 18,795 | 74.58 |

| 1-4 deaths | 69,683 | 4,297 | 61.66 |

| 5-18 deaths | 57,050 | 3,948 | 69.2 |

| 19-74 deaths | 62,952 | 4,776 | 75.87 |

| 75-1,000 deaths | 50,663 | 4,540 | 89.61 |

| 1,001+ deaths | 11,679 | 1,234 | 105.66 |

| No | 1,733,082 | 114,566 | 66.11 |

Notes: Child outcomes indicate the mortality rates in our sample overall and among those exposed to conflicts of different intensity. The mortality rate is based on a cross-section over the entire study period. Of note, the lower rate in cluster areas with 1-4 conflict-related deaths relative to areas without any conflict is a cross-section difference that fails to capture the within-cluster effects that measure mortality rate in times of conflict relative to times of no-conflict, as reflected in our main analyses.

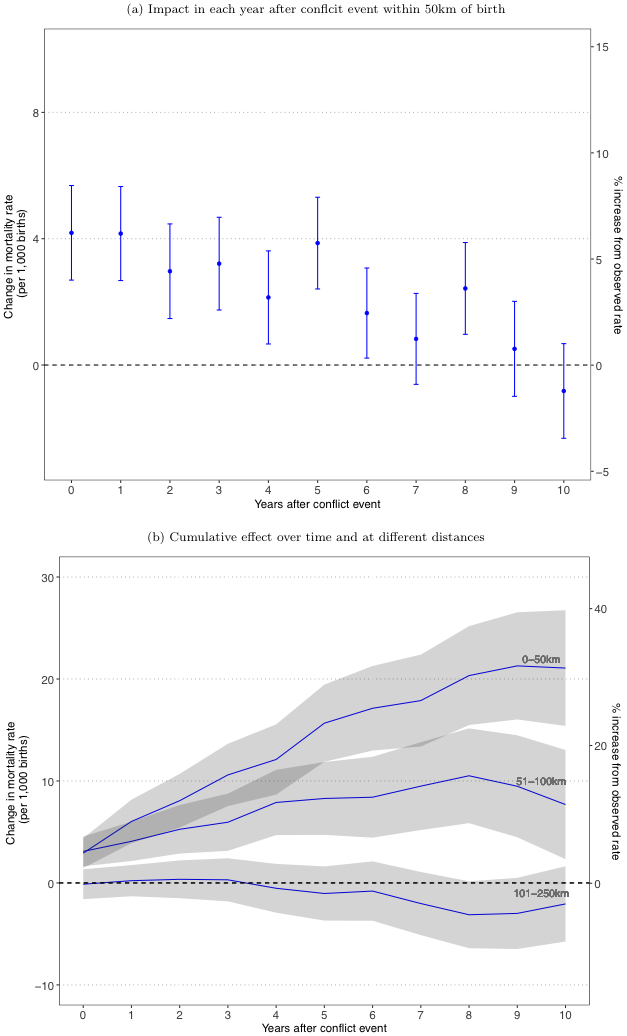

Figure 3 shows the lingering effects of conflict. Figure 3a shows the mortality effect of conflict (of any intensity) up to 10 years prior to birth (births from 1995-1998 include conflict information for less than 10 years before birth, because conflicts were only geocoded as far back as 1989). We find that conflict is followed by elevated mortality risk for infants born up to 8 years subsequent to the conflict (Table 3). Figure 3b shows the cumulative 10-year effect of armed conflict by distance from the conflict: 31.4% increase for conflicts 0-50km away (95% CI 22.9-39.8%), 11.4% for conflicts 50+−100km away (95% CI 3.5-19.4), and −3.1% for conflicts 100+−250km away (NS). Finally, we examine the extent to which conflict elevates related risk factors.

Figure 3:

Impact of conflict on under-1 mortality over time. The top panel (Figure 3A) shows the coefficients from a regression with conflict exposure indicators for each year up to 10 years before birth. Each coefficient represents the independent lingering risk of mortality in the first year of life from historical conflict taking place up to 10 years before birth. Conflicts up to 8 years prior to birth show an independent relationship with increased under-1 mortality. The bottom panel (3B) shows the cumulative mortality risk over time for conflicts that occurred within 0-50km, 50+ - 100km, and 100+ - 250km from a child’s birth, estimated in one regression, and reveals an attenuated effect at farther distances. Grey bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Regression results for the impact of conflict on under-1 mortality

| Under-1 Mortality (Per 1,000 Births) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary | Categorical | Binary | Categorical | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Any Conflict | 5.201*** (0.756) |

5.075*** (0.756) |

||

| 1-4 Deaths | 1.991* (1.073) |

1.827* (1.073) |

||

| 5-18 Deaths | 5.423*** (1.245) |

5.298*** (1.246) |

||

| 19-74 Deaths | 6.385*** (1.25) |

6.280*** (1.251) |

||

| 75-1,000 Deaths | 7.355*** (1.577) |

7.290*** (1.575) |

||

| 1,001+ Deaths | 17.904*** (3.307) |

17.695*** (3.308) |

||

| mother’s educ=primary | −4.312*** (0.635) |

−4.298*** (0.635) |

||

| mother’s educ=secondary | −11.935*** (0.747) |

−11.947*** (0.747) |

||

| mother’s educ=higher | −16.956*** (1.221) |

−16.980*** (1.221) |

||

| age of mother | −0.523*** (0.035) |

−0.523*** (0.035) |

||

| child is female | −11.442*** (0.366) |

−11.441*** (0.366) |

||

| temperature (degrees c) | 3.431*** (0.633) |

3.369*** (0.633) |

||

| rainfall (mm) | −0.001 (0.001) |

−0.001 (0.001) |

||

| night lights (intensity) | −0.003 (0.002) |

−0.003 (0.002) |

||

| food prices (price index) | 0.12 (0.087) |

0.123 (0.087) |

||

| country-month FE | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| birth year FE | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| DHS cluster FE | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Observations | 1,985,109 | 1,985,109 | 1,984,717 | 1,984,717 |

| R2 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.048 |

Note:

0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

Each column represents a separate statistical model. In Columns 1 & 3 conflict is represented as a binary exposure, while in Columns 2 & 4 it is broken down into 5 binary categories representing conflict intensity. The estimates in rows 1-6 represent the increase in the probability of death (per 1,000 births) before reaching age 1 for infants exposed to conflict during their first year of life, relative to infants born in the same area during years without conflict. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Person-level controls are shown in rows 7-11, and cluster-level, time-varying controls in rows 12-15

The Appendix contains several additional cogent findings. Analysis of neonatal mortality identifies a strong effect of conflict in the year leading up to birth on survival in the first month of life, suggesting possible harms to maternal health and care during pregnancy, labor, and delivery; we find that the under-1 effect goes down by nearly 30% when excluding deaths in the first month of life (SA2.1). Next, we find that the risk of dying before age 5 is elevated both for children in the first year of life as well as in the second year of life (SA2.2). While the absolute risk increase for children in the second year of life is smaller than in the first year, the baseline mortality rate is also lower, and the proportional increase is nearly as high as that for under-1 children, 4.8% increase. Finally, analysis of effect heterogeneity by the child’s residence (urban/rural) revealed a significantly stronger effect in rural areas; an increase of 6.6 deaths per 1,000 births in rural areas compared 2.4 in urban areas (p-value on rural by conflict interaction term < 0.01, SA2.4). Figure S12 and Table S18 (SA2.6 and SA4.7) show that being born near a conflict results in increased risk of being stunted. Although we have fewer observations for this analysis, we identify a consistent effect, with an overall conflict effect leading to 1.0% (95% CI 0.2-1.8) higher rates of stunting, a 2.9% increase above a 34.4% average prevalence.

Multiple robustness analyses are shown in the Appendix. The effect size is stable when leaving countries out, remaining between 4.1 (Liberia out) and 6.9 (Nigeria out) deaths per 1,000 births. When restricting our sample to children who have not migrated, we lose nearly 75% of our sample, but observe an overall effect size only moderately attenuated (3.7 per 1,000 births, 95% CI 0.5-7.0).

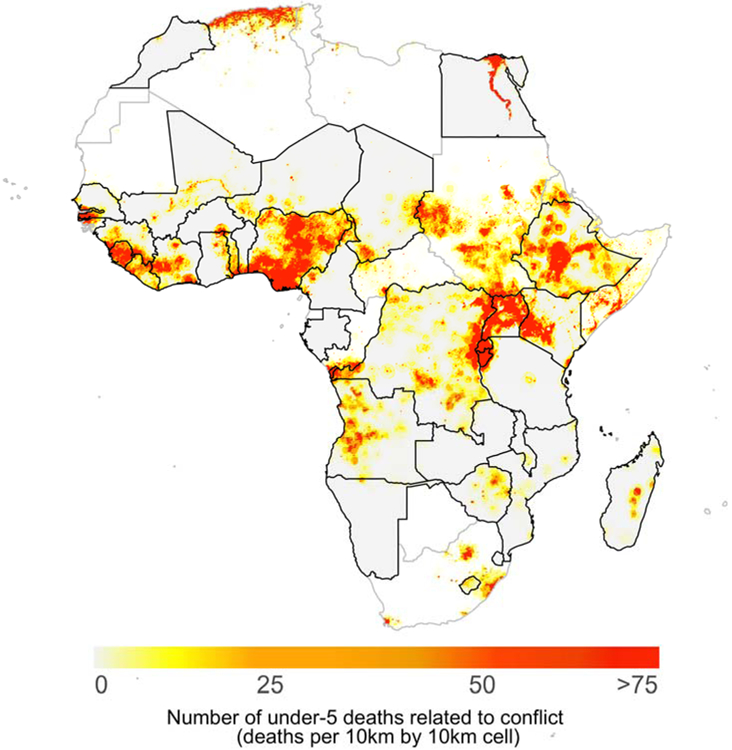

We use our findings to estimate the number of conflict-related child deaths throughout Africa (SA3). We geospatially linked child births and mortality rates from 1995 to 2015 to all conflicts in Africa from 1989 to 2015, and use the increased under-5 and under-1 mortality related to conflict to estimate the number of children who would not have died in the absence of conflict.32,33 We estimate that 4.9-5.5 million under-5 deaths between 1995 and 2015 were related to armed conflict (6.6-7.4% of all under-5 deaths). Figure 4 shows the distribution of under-5 deaths related to armed conflict. We estimate that 3.1-3.5 million under-1 child deaths are related to conflict from 1995 to 2015 (6.6 to 7.3% of all under-1 deaths during the entire period). Compared with the number of armed conflict deaths in the UCDP dataset, the ratio of under-1 deaths to armed conflict deaths is 3.2-3.6 (5.0-5.7 for under-5 deaths). To the extent that conflict also likely elevates the mortality risk of other non-participant vulnerable groups such as school-age children, adolescents, women, non-combatant men, or the elderly, our estimates represent a floor to the indirect effects of conflict on mortality.

Figure 4:

Number of under-5 deaths due to conflict in Africa. We used 0.1 degree × 0.1 degree gridded estimates of the number of births, the infant mortality rate, and conflict timing and location to estimate the number of observed deaths in each grid cell, and then the number of deaths expected in the absence of conflict. We then aggregated the grid cell level estimates for the period 1995 to 2015. We used national infant mortality rates for countries without gridded infant mortality rate. The scale indicates the number of deaths in each grid cell (roughly 10km × 10km). The biggest clusters of child deaths are apparent in Nigeria, East-Central Africa (Uganda, DRC, Burundi, Kenya), Ethiopia, Lybia, Egypt, and West Africa (centered around Sierra Leone). Thick borders and gray background represent study countries.

Discussion

More frequent and more intense armed conflicts have taken place in Africa over the past 30 years than in any other continent.34,35 This analysis shows that the impacts of armed conflict extend beyond the deaths of combatants and physical devastation: armed conflict substantially increases the risk of death of young children, for a long period of time. It may not be surprising that young children are vulnerable to nearby armed conflicts, but we show that this burden is substantially higher than previously indicated. We present evidence that armed conflicts contribute to death and stunting for many years and over wide areas, and while we stop short of directly examining the effects on other vulnerable populations like young women, we find indirect evidence of harms to these populations as well.

The Global Burden of Disease indicates that “Conflict” and “Interpersonal violence” make up around 0.4% of under-1 and under-5 deaths in Africa, and does not otherwise constitute a risk factor.8 While these estimates may reflect efforts to count casualties of conflict and violence, our analysis suggests that this is a substantial under-estimate: the portion of deaths among under-1 and under-5 children related to conflict is approximately 10-fold higher. The risk is clearest for conflicts contemporaneous with a child’s first year of life, though the effects are even larger for chronic conflicts and when considering long-term effects.

This study supports a complex role for conflict in child mortality. The contemporaneous and geographically proximate increase in mortality is consistent with direct compromise of the safety of young children – deaths from direct injuries or harm to the parents or homes of young children. However, we also find increasing risk of stunting and neonatal mortality, suggesting additional pathways are involved. Complications of labor and delivery, and infectious diseases exacerbated by nutritional deficiencies are dominant causes of death in these age groups in Africa, and, in addition to direct injuries and harm, may be the most relevant proximate causes of death involved in the observed increased risk. However, the chronic and long-term effects may additionally involve increased risk from a compromised environment – the destruction of infrastructure for basic goods such as vaccinations, water, sanitation, food security, maternal and antenatal care and potential effects on human resources for health. In particular, the elevation of risk among neonates and the observed effects from conflict in the year before birth supports pathways that affect maternal health and healthcare, including nutrition.

The findings of this study depend on data and approaches with unique limitations that deserve further elaboration. First, we attempt to identify the causal effects of armed conflict, but our interpretations are limited by the observational nature of the data. Our various fixed-effects control for differences between areas where conflict does and does not occur (cluster fixed-effects), general time trends (year fixed-effects), and seasonality (country-month fixed-effects). However, residual confounders that change within the same DHS cluster over time, that we did not control for, and that are correlated with conflict and infant mortality limit the causal strength of this work.

Second, the fact that conflict leads to migration and displacement could bias our estimates. Displacement could have the effect of biasing our observed estimate up (e.g. if healthier families leave the conflict zones, and we count them as not-near-conflict), or down (e.g. if mortality risk of displaced populations is same as those who stayed, in which case the mortality effect of conflict far from conflict areas would look more like the mortality effect inside conflict areas). We test for this by restricting our sample to mothers who indicated they lived in the same house for at least 10 years prior to the child’s birth (SA1.3), and results were very similar. However, only 40% of households were asked this migration question, leading to imprecise estimates.

Third, to estimate the number of deaths related to conflict, we assume the average effect of conflict in our sample is applicable to the rest of the countries in Africa. It is possible that conflict has a different effect in countries like Somalia, Sudan, or the Central African Republic, which have all been plagued by conflict for decades. If the effect is substantially different in these countries, this could lead to unpredictable bias of our estimates. Finally, our analysis relies on location estimates from DHS surveys and the UCDP conflict data. Imprecision in location estimates would create measurement error in exposure to conflict, which would attenuate our estimates toward the null. DHS clusters are randomly scrambled by up to 2km in urban areas and up to 5km in rural areas, which could create measurement error in conflict exposure. The use of a 50km radius to measure conflict exposure should make this measurement error small, while not expanding the annulus to a size that might affect the plausibility of conflict impacts. The location of some conflict events is also not perfectly precise, increasing the chance for measure error within a small geographic unit of exposure. However, when we drop conflict events that lack precision (indicated by UCDP) or weight observations by the level of precision, our results are unchanged (see Appendix SA1.5).

The echoes of armed conflict are clearly reflected in child mortality data. This analysis suggests several intuitive implications. First, our findings suggest that the burden of conflict on child health in Africa – and likely elsewhere – is largely unknown. Our estimates of the effect of armed conflict are large, and suggest that conflict may be a sizeable under-recognized risk factor for child mortality. Second, the distribution of deaths by age, distance, and duration of conflict provide important clues about which populations may be most vulnerable, including their locations and the causes of death that may be most directly implicated. Third, this study leads to several intuitive analyses into the burden of conflict beyond Africa, into additional “spillovers” of conflict on families and health systems, mechanisms by which conflicts increase mortality risk, and the effectiveness of potential interventions for building resilience and expediting recovery in conflict zones. Finally, we hope this revised awareness of the civilian toll of conflict will increase awareness and work into the prevention of armed conflict and its consequences.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The burden of armed conflict on child mortality is unclear. On the one hand, the vulnerability of young children and the destructiveness and intensity of armed conflict suggest that, intuitively, conflict exacts a high toll on children. On the other hand, child mortality continues to fall even in countries heavily affected by conflict, and the Global Burden of Disease estimates that conflict accounts for less than 0.4% of child deaths in Africa (the focus of this study). Empirical studies looking into the effects of armed conflict on the civilian population show impacts on educational attainment, personal economic outcomes, and national economic growth. Studies from specific conflicts also show impacts on stunting in children and maternal healthcare. However, the continent-wide effect of armed conflict on mortality remains unknown.

Added value of this study

We provide unique insights along several important dimensions in the study of armed conflict. First, our scope is uniquely broad: we analyze 15,441 armed conflict events resulting in 968,444 conflict-related deaths between 1995-2015 and link those by location and timing to 1.99 million births, 133,361 under-1 deaths, and 204,101 under-5 deaths in 35 countries between years 1995 and 2015, all in Africa. Second, we identify and demonstrate a strong and stable increase of 7.7% in the risk of dying before reaching age 1 among babies born within 50km of an armed conflict. We show that this increase in risk rises from 3.0% for armed conflicts resulting in 1-4 deaths to 26.7% for conflicts resulting in more than 1,000 deaths; and from 4.2% for conflicts lasting less than a year to 17.4% for conflicts lasting more than 5 years. We identify the boundaries in space (up to 100km) and time (up to 8 years following conflict) of increased infant mortality risk. We estimate that, between 1995 and 2015, the number of infant deaths related to conflict outnumbered the number of armed conflict deaths 3.2-3.6-to-1.

Implications of the available evidence

The burden of conflict on infant and child mortality is substantial and higher than available estimates. The available evidence suggests that conflict increases mortality risk through impacts on maternal health, infectious disease risk, and malnutrition. These findings have implications for the targeting of interventions for promoting child health during and following armed conflicts. To our knowledge, this work is the first comprehensive analysis of the large and lingering impacts of armed conflicts on the health of non-combatant populations. Future analyses should identify effects in other conflict-prone regions. In addition, this work should prompt re-examination of the role of armed conflict as an important cause or risk factor for child mortality.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support

The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Centre for Global Child Health at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Footnotes

Role of the Funding Organization or Sponsor

None

References

- 1.Akresh R, De Walque D. Armed conflict and schooling: Evidence from the 1994 Rwandan genocide: World Bank; Washington, DC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta S, Clements B, Bhattacharya R, Chakravarti S. Fiscal consequences of armed conflict and terrorism in low-and middle-income countries. European Journal of Political Economy 2004; 20(2): 403–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise PH. The Epidemiologic Challenge to the Conduct of Just War: Confronting Indirect Civilian Casualties of War. Daedalus 2017; 146(1): 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 2016; 388(10053): 1725–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. The Lancet 2015; 385(9966): 430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2014; 384(9947): 957–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guha-Sapir D, Schlüter B, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Lillywhite L, Hicks MH-R. Patterns of civilian and child deaths due to war-related violence in Syria: a comparative analysis from the Violation Documentation Center dataset, 2011–16. The Lancet Global Health 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Burden of Disease Data Visualizations: GBD Compare. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (accessed January 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akresh R, Lucchetti L, Thirumurthy H. Wars and child health: Evidence from the Eritrean–Ethiopian conflict. Journal of development economics 2012; 99(2): 330–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bundervoet T, Verwimp P, Akresh R. Health and civil war in rural Burundi. Journal of Human Resources 2009; 44(2): 536–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoiu C, Shemyakina ON. Armed conflict, household victimization, and child health in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Economics 2014; 108: 237–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinney MV, Kerber KJ, Black RE, et al. Sub-Saharan Africa's mothers, newborns, and children: where and why do they die? PLoS medicine 2010; 7(6): e1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundberg R, Eck K, Kreutz J. Introducing the UCDP non-state conflict dataset. Journal of Peace Research 2012; 49(2): 351–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.How Kreutz J. and when armed conflicts end: Introducing the UCDP Conflict Termination dataset. Journal of Peace Research 2010; 47(2): 243–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croicu M, Sundberg R. UCDP GED Codebook version 17.1 Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundberg R, Melander E. Introducing the UCDP georeferenced event dataset. Journal of Peace Research 2013; 50(4): 523–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundberg R, Lindgren M, Padskocimaite A. UCDP Geo-referenced event dataset (GED) codebook. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bond D, Bond J, Oh C, Jenkins JC, Taylor CL. Integrated data for events analysis (IDEA): An event typology for automated events data development. Journal of Peace Research 2003; 40(6): 733–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raleigh C, Linke A, Hegre H, Karlsen J. Introducing acled: An armed conflict location and event dataset: Special data feature. Journal of peace research 2010; 47(5): 651–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aliaga A, Ren R. Optimal sample sizes for two-stage cluster sampling in Demographic and Health Surveys. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian S. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. International journal of epidemiology 2012; 41(6): 1602–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Heydrich C, Warren JL, Burgert CR, Emch M. Guidelines on the use of DHS GPS data: ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgert CR, Colston J, Roy T, Zachary B. Geographic displacement procedure and georeferenced data release policy for the Demographic and Health Surveys. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Organization WH. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry Geneva; 1995. WHO technical report series 1995; 854: 2009–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cameron AC, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources 2015; 50(2): 317–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuirk E, Burke M. The economic origins of conflict in Africa: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke MB, Miguel E, Satyanath S, Dykema JA, Lobell DB. Warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa. Proceedings of the national Academy of sciences 2009; 106(49): 20670–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jean N, Burke M, Xie M, Davis WM, Lobell DB, Ermon S. Combining satellite imagery and machine learning to predict poverty. Science 2016; 353(6301): 790–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatem AJ, Campbell J, Guerra-Arias M, de Bernis L, Moran A, Matthews Z. Mapping for maternal and newborn health: the distributions of women of childbearing age, pregnancies and births. International Journal of Health Geographics 2014; 13(1): 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alegana VA, Atkinson PM, Pezzulo C, et al. Fine resolution mapping of population age-structures for health and development applications. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2015; 12(105): 20150073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.IHME. Africa Under-5 and Neonatal Mortality Geospatial Estimates 1998–2017. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golding N, Burstein R, Longbottom J, et al. Mapping under-5 and neonatal mortality in Africa, 2000–15: a baseline analysis for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 2017; 390(10108): 2171–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linard C, Gilbert M, Snow RW, Noor AM, Tatem AJ. Population distribution, settlement patterns and accessibility across Africa in 2010. PloS one 2012; 7(2): e31743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allansson M, Melander E, Themnér L. Organized violence, 1989–2016. Journal of Peace Research 2017; 54(4): 574–87. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gleditsch NP, Wallensteen P, Eriksson M, Sollenberg M, Strand H. Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset. Journal of peace research 2002; 39(5): 615–37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.