Abstract

This study tested sexual abuse as a unique predictor of subsequent adolescent sexual behaviors, pregnancy, and motherhood when in company with other types of maltreatment (physical abuse, neglect) and alternative behavioral, family, and contextual risk factors in a prospective, longitudinal study of maltreated (N=275) and comparison (N=239) nulliparous females aged 14-19 years-old assessed annually through 19 years old. Hierarchical regression was used to disentangle risk factors that account for the associations of maltreatment type on risky sexual behaviors at 19 years old, adolescent pregnancy, and adolescent motherhood. Findings indicate that sexual and physical abuse remain significant predictors of risky sexual behaviors, and that sexual abuse remains a significant predictor of adolescent motherhood when alternative explanatory variables are controlled.

Keywords: adolescence, risky sexual behavior, adolescent motherhood, sexual abuse

Introduction

Becoming a mother during adolescence is an atypical developmental trajectory that can interfere with the adaptive emergence to adulthood (Arnett, 2000) and constitutes a “developmental discordance” (Shanahan, 2000) for adolescents who do not do not yet possess the psychological and emotional tools necessary to realize the mastery of the additional demands and responsibilities required to parent a child. From a developmental life course perspective, such discordances occur when there is an asynchrony between subjective age and psychosocial maturation such that adaptive transitions to the next developmental stage are jeopardized (More, 1953). This asynchrony can lead to maladaptive behaviors when coupled with an inability to adequately cope with increasing demands (Benson & Elder, 2011). Indeed, adolescent motherhood has been shown to have physical and mental health consequences for mothers (Patel & Sen, 2012; Lee et al., 2016), and can negatively impact economic wellness that persists into middle adulthood (Assini-Meytin & Green, 2015). Moreover, children born to adolescent mothers are at risk for developmental and cognitive deficiencies (Jahromi, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Zeiders, 2016) underscoring the potent intergenerational impact that young motherhood can confer on offspring. Although adolescent motherhood rates have decreased in recent years in the United State (US; Martin et al., 2017), primary prevention remains a public health priority due to the fact that US rates are substantially higher than in other western industrialized nations (Sedgh, Finer, Bankole, Eilers, & Singh, 2015) and that sociodemographic disparities persist (Romero et al., 2016). Increasing the precision of primary prevention efforts involves identifying at-risk groups that would benefit from targeted intervention. Adolescents who have been identified as victims of child maltreatment (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse, and neglect) is one such group (Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes, & Johnson, 2004; Wilson, Mitchell, & MacKenzie, 2014). Child maltreatment, when considered through the lens of developmental psychopathology, can offer important clues into why otherwise healthy individuals diverge from normative developmental pathways to maladaptive outcomes (Toth & Cicchetti, 2013).

Child Maltreatment and Sexual Risk Behaviors

There have been several approaches to the study of how maltreatment might impact sexual development. In a retrospective cohort study of 5,060 females (Hillis, Anda, Felitti, & Marchbanks, 2001) those reporting childhood adversity (including child maltreatment) were more likely to have also engaged in early sexual initiation (prior to age 15) and HIV-risk behaviors. A birth cohort study of 1,265 New Zealanders showed that, of the 533 women with complete data, those who became pregnant by age 20 were significantly more likely to have retrospectively reported experiencing sexual abuse in childhood (Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2001). In a sample of 210 adolescent mothers, 12% reported sexual trauma prior to age 13 and 43% reported polytraumatization; that is, the experience of multiple traumatic events throughout development (Killian-Farrell, Rizo, Lombardi, Meltzer-Brody, & Bledsoe, 2017). While these approaches offer valuable insight into population trends and associated risk factors, the precision of this work is compromised by the retrospective nature of maltreatment recollections and an inability to explicate plausible alternative explanations.

In contrast, studies that have included individuals with documented maltreatment followed forward in time can be used to draw powerful inferences about the link between maltreatment and subsequent sexual risk-taking outcomes. For example, Widom and colleagues identified children in the criminal justice system who had documented histories of abuse or neglect prior to age 11 (N=676) and matched controls with no criminal justice system history or involvement (N=520). From an interview conducted 20 years after the documented maltreatment, they found that maltreated females were more likely to report prostitution, but found no relationship for promiscuity (i.e., having sex with >10 people per year) or teen pregnancy (Widom & Kuhns, 1996). However, the teen pregnancy rate reported in the control group was relatively high (i.e., 20.9%) and was twice the national average for that time period (Henshaw & Feivelson, 2000) signaling significant risk in the control group that could attenuate the ability to detect group main-effects (Shenk, Noll, Peugh, Griffin, & Bensman, 2015).

In a study of 859 high-risk youth (both males and females), those with documented maltreatment reported more risky sexual behaviors in adolescence (Thompson et al., 2017). In a prospective study following 251 adolescents (169 with documented maltreatment) longitudinally, maltreatment was related to subsequent risky sexual behaviors (i.e., ≥ 4 sexual partners and lack of condom use during last sex) for both males and females in adolescence (Negriff, Schneiderman, & Trickett, 2015). In another prospective cohort study tracking 435 females longitudinally throughout adolescence (266 with documented maltreatment), birthrates confirmed through medical records were significantly higher than for matched comparisons (Noll & Shenk, 2013). Finally, in a meta-analysis of 21 studies, those who experienced sexual abuse were 2.21 times more likely to experience an adolescent pregnancy than those who did not, even after controlling for study heterogeneity (e.g., prospective versus retrospective designs) (Noll, Shenk, & Putnam, 2009).

Differing Types of Maltreatment

Although findings are by-and-large consistent across multiple studies, it is not altogether clear whether or not different types of maltreatment confer comparable or unique risks for these sexual risk outcomes. This will be important to understand given that targets for intervention may differ for various types of trauma. For example, given that neglect involves a lack of surveillance, involvement, and nurturing on the part of parents (Mennen, Kim, & Trickett, 2010), victims of neglect may require increased parental monitoring and guidance in order to stave off these outcomes. Alternatively, the interpersonal violence involved in physical abuse cases can foster heightened externalizing behaviors including delinquency and substance use (Lansford et al., 2007; Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2010) that often co-occur with risky sexual behaviors during adolescence. The Traumagenic Dynamics Model posits that, because of the explicit sexual nature of sexual abuse, these victims may require intensive intervention focused on the reparations of sexual boundary violations, powerlessness, and trust (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). Noll and colleagues also put forth a model of ‘cognitive distortions’ showing that sexual abuse victims displayed a heightened preoccupation with sex (which included sexually intrusive thoughts) coupled with a marked shame and ambivalence toward sexual activity during late adolescence (Noll, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003). Although these theoretical models, along with a convincing meta-analysis (Noll et al., 2009), suggests that sexual abuse poses inordinate risk for outcomes of a sexual nature, sexual abuse should be examined in company with other types of maltreatment in order to assert its unique impact on sexual development.

While there has been very little research that has explicitly examined differing types of maltreatment within the same predictive models, one notable exception (Negriff et al., 2015) examined how differing types impacted risky sexual behaviors at mean age 18. Findings indicated that sexually abused females were at higher risk for having had sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and neglected females were more likely to had been pregnant than females with other maltreatment types or comparison females. While this is an impressive study, the associations examined are at the zero-order with few additional alternative explanatory variables considered in models beyond demographics. This is an important point to be made because it is widely accepted that maltreatment does not occur in a vacuum. There are demographic, familial, psychological, and behavioral contexts that co-occur with maltreatment, many of which are also associated with risky sexual behaviors and teen pregnancy. Hence, it is possible that zero-order associations between maltreatment and sexual risk-taking could be explained by these co-occurring contexts. If this is indeed true, then interventions that target these particular contexts would suffice for both victims of maltreatment as well as adolescents in general. If, on the other hand, alternative explanations can be ruled out as explaining away the impact of maltreatment, then a strong case can be made that interventions addressing the trauma of maltreatment per se are necessary, and even essential, if we are to stave off subsequent sexual risk-taking and impact teen birthrates. Moreover, different types of maltreatment also co-occur and it is rare that children experience only one type. This is illustrated nicely in a sample of 2,292 children mean aged 9, 52% of whom had well-documented maltreatment, where only 1% experienced sexual abuse in isolation (Vachon, Krueger, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2015). Hence, if we are to truly understand the unique impact of maltreatment types so that we can hone in on the best ways to intervene for victims, it will be important to isolate the impact of co-occurring contextual risk factors, various types of maltreatment, and the impact of other types of trauma and adversity.

One powerful attempt at ruling out alternative explanations comes from a study by Garwood and colleagues (2015) who linked protective service, health, income assistance, juvenile justice, mental health, runaway shelter, and special education data for 3,281 adolescent females. In addition to demographics, poverty status, and family variables (including caregiver’s education level, mother’s age at the target adolescent’s birth, and parent’s mental health treatment), exact dates of mental health interventions, juvenile court offenses, and sexually transmitted infections were used to identify services and incidences occurring prior to an adolescent becoming pregnant. Results indicated that documented maltreatment was a significant predictor of teen pregnancy even after controlling for neighborhood disadvantage, caregiver factors, and prior mental health and behavioral problems. Although this paper does not distinguish between types of maltreatment, it makes an important contribution for several reasons. Not only is maltreatment documented, but the set of potential alternative explanatory variables is extensive, each occurring before the onset of teen pregnancy. The ability to model and test the impact of risk factors that occur prior to pregnancy facilitates temporal ordering, thus strengthening causal inference and allowing for tests of mediation that can signal potent avenues of intervention.

Alternative Explanatory Variables

A host of contextual, psychosocial, and behavioral risk factors has been well-documented as correlates of adolescent sexual risk behaviors. These variables should be taken into account when attempting to discern the relative impact of maltreatment on sexual risk-taking given that many also correlate significantly with maltreatment. In addition to poverty and other neighborhood characteristics as discussed above, important familial contexts have been shown to be powerful predictors of teen pregnancy. For example, living in close proximity to others who have been adolescent mothers (e.g., sisters, friends, or mother) increases the likelihood that an adolescent will become a teen mother herself (Cox, Shreffler, Merten, Schwerdtfeger Gallus, & Dowdy, 2015; Wall-Wieler, Roos, & Nickel, 2018). Having both a sister and a mother who were adolescent mothers increased the risk of pregnancy by nearly four-fold (East, Reyes, & Horn, 2007). The extent to which parents are nurturing and willing to engage the adolescent in communication about sexual activity and contraception use is another important familial context that has been shown to be protective against pregnancy (Bonell, Wiggins, Fletcher, & Allen, 2014) and risky sexual behaviors in adolescence (Khurana & Cooksey, 2012).

Poor psychosocial functioning including depressive symptomology has been shown to increase the likelihood of motherhood prior to age 20 (Quinlivan, Tan, Steele, & Black, 2004), and low self-esteem is associated with a lack of condom use (Davies et al., 2003) and adolescent pregnancy (Corcoran et al., 2000). Cognitive ability, on the other hand, seems to function as a protective psychosocial factor. Combining data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Bearman & Burns, 1998) and the Biosocial Factors in Adolescent Development project (Halpern, Udry, & Suchindran, 1997), Halpern and colleagues demonstrated that vocabulary scores were correlated with postponement of sexual initiation (Halpern, Joyner, Udry, & Suchindran, 2000). Longitudinal data from the Healthy and Alive! project showed that, in a sample of 3,163, those with higher academic performance postponed sexual initiation and sexual activities until later in adolescence (Santelli et al., 2004).

Adolescent attitudes and beliefs can also impact sexual risk behaviors. For example, religiosity and religion-based behaviors have been shown to be protective in terms postponing sexual debut and diminished the engagement in risky sexual behaviors (Hawes & Berkley-Patton, 2014; Lefkowitz, Gillen, Shearer, & Boone, 2004). In a study of both sexually abused and comparison females, being preoccupied with sex in terms of thinking about sex, consuming pornography, and entertaining sexual fantasies was associated with increases in high risk sexual behaviors such as inconsistent condom use and a high number of sexual partners in late adolescence (Noll, Trickett, et al., 2003). Various attitudes underlying the motivation to become pregnant can be conceptualized as “pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions” and have been shown to be significantly associated with adolescent pregnancy risk. For example, idealizing pregnancy and positive or ambivalent attitudes toward child-rearing have been shown to be characteristics of teen mothers (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2013; East, Chien, & Barber, 2012; Quinlivan et al., 2004). In addition, perceived invulnerability to sexually transmitted infections and a lack of knowledge and use of contraception have also associated with pregnancy-risk behaviors such as early coital initiation, multiple sex partners, and sex under the influence of substances (Miller, 2002; Polacsek, Celentano, O’Campo, & Santelli, 1999).

Since the 1970s, there has been consensus that problem behaviors in adolescence cluster together and co-vary (Jessor, 2018). As such, it will be important to take into account other, non-sexual risk behaviors as possible contributors to sexual risk taking in models that purport a comprehensive understanding of the unique variation associated with each. For example, in several studies, alcohol and other drug use were powerful predictors of sexual initiation for adolescents (Santelli et al., 2004) and illicit drug use was a significant predictor of adolescent motherhood (Quinlivan et al., 2004; Santelli et al., 2004). Similarly, externalizing behaviors such as theft, physical assault, truancy, and other delinquent behaviors were correlated with adolescent pregnancy in females in a secondary data analysis of the National Survey on Child and Adolescent Well-being (Helfrich & McWey, 2014). Finally, affiliation with high-risk and deviant peers was predictive of adolescent sexual behaviors in a study of 517 adolescents followed longitudinally (Lansford, Dodge, Fontaine, Bates, & Pettit, 2014).

The Present Study

The present study utilized a sample of adolescent females 14–17 years old with and without a documented history of maltreatment followed longitudinally through 19 years old. The overarching goal was to examine whether differing types of maltreatment (sexual abuse, physical abuse, or neglect) account for unique variation in sexual risk-taking sexual behavior outcomes including pregnancy, and motherhood at age 19. We also sought to take into account a comprehensive set of additional contextual antecedent, psychosocial functioning, attitude and belief, and non-sexual risk behavior variables occurring prior to age 19 outcomes which had been previous documented in the literature as important indicators of sexual risk-taking during adolescence. We also included several important covariates in these models that could have confounding effects including household income and the number of alternative traumas (aside from maltreatment) that the adolescent may have experienced. To better inform prevention efforts, we included all of these variables within the same models and evaluated the relative contribution of each in accounting for variation in outcomes. We examined the three distinct outcomes (age 19 high-risk sexual behaviors, adolescent pregnancy, and adolescent motherhood) because not every adolescent who engages in risky sexual activity becomes pregnant, and not every pregnancy results in an adolescent becoming a mother. Much of the extant literature combined these outcomes or did not make deliberate distinctions between them. Using the present approach would shed light on the differential predictors of each and, thus, whether or not distinct avenues of intervention might be warranted. Because of the explicitly sexual nature of sexual abuse, we hypothesized that sexual abuse will remain a significant predictor of these sexual risk-taking outcomes when in company with other forms of maltreatment and alternative explanatory variables. However, we expected that the relationship of both physical abuse and neglect to outcomes would be accounted for by one or more of the alternative explanatory variables.

Methods

Data Sources

Data come from the Female Adolescent Development Study, a prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 514 ethnically diverse adolescent females (mean age 15), conducted between 2007 and 2012. The purpose was to examine the impact of maltreatment on sexual development in adolescent females. Maltreated females (n = 275) were recruited through local child protective services (CPS) agencies for having a substantiated incidence of sexual abuse, physical abuse, or neglect within the prior 12-months. Maltreated females were all in in-home care at the time of study entry. Comparison females (n = 239) were recruited from an hospital-based outpatient adolescent health center that serves low income families within the same catchment areas as the protective service agencies. All participants completed comprehensive annual study assessments for 4 years until age 19 (see BLINDED FOR REVIEW for full description of procedures). During the course of the five-year study, self-reported maltreatment was repeatedly assessed and confirmed via CPS records. Comparison females with substantiated maltreatment reports were excluded from analyses to preserve the integrity of the groups; the final analytic sample was 435 (maltreated, 266; comparison, 169). Procedures were approved by the local Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was secured from the National Institutes of Health.

Variables and Variable Definitions

Alternative Explanatory Variables.

A comprehensive measurement model was employed that included measures selected from large national surveys of adolescent behaviors and widely used questionnaires or assessment tools, the psychometrics for which have been published elsewhere. Table 1 provides a description of these measures as well as the Time 1 sample range, means, standard deviations and estimates of internal consistency/alpha reliability. The table also depicts significant maltreatment versus comparison group differences.

Table 1.

Alternative Explanatory Predictor Variables: Measures and Sample Descriptive Statistics (N=435)

| Construct | Measure Name, Citation & Description | Range | α | x̄ | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteems | Self-perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988); global self-esteem subscale; 4-items averaged (1=“not at all like me” to 4 “very much like me”) | 1 – 4 | .91 | 2.68 | 0.74 |

| Cognitive abilitys,p | Woodcock-Johnson III Brief IQ Standard Score (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001); Population µ =100; SD = 15 |

59 – 128 | NA | 90.20 | 12.95 |

| Depressions | BDI (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); depressive symptoms; 21-items (0 = “low” to 3 = “high”) | 0 – 55 | .84 | 11.33 | 10.07 |

| Substance Uses,n | Monitoring the Future (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2005); past year use tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs; 22 items (0 = “never” to 6 = “40 or more times”) |

0 – 56 | NA | 5.39 | 7.71 |

| Externalizings,p | CBCL-Parent form (Achenbach, 1991); 33-items (0= “not true” to 2 = “very true”) | 0 – 47 | .81 | 12.79 | 11.50 |

| Risky Peerss | Monitoring the Future (Johnston et al., 2005); # of friends using substances or engaging in sexual behaviors; 10-items (0 = “none” to 4 = “most or all”) |

0 – 28 | .72 | 8.97 | 5.95 |

| Preoccupation with Sex |

SAAQ (Noll, Trickett, et al., 2003); frequency of activities that signal sexual preoccupation such as consuming pornography or fantasize about sex 15 items (1 = “never” to 5 = “almost every day”) |

16 – 75 | .91 | 30.05 | 12.68 |

| Low Birth Control Efficacy | SAAQ; learned about contraception from friends or sex partner; 2-items (0= “no, never” to 4= “yes, and found it informative”) + prefer ineffective birth control methods such as rhythm method; 4-items (0= “not preferred” to 5= “most preferred”) | 0 – 22 | .71 | 5.95 | 4.79 |

| Religiousness | Religious Commitment Inventory (Worthington et al., 1989); religious beliefs; 12-items (0 “none” 4 “very much”) + frequency of activity; 1-item (0= “never” to 6 = “> 2 per week”) | 0 – 54 | .90 | 17.20 | 13.34 |

| Pregnancy-vulnerable Cognitions | Role-timing & Desires Scale (East, 1998); expected difficulties of motherhood; 5 items (0 = “extremely” to 9 “none” + desire to become pregnant now, in 1 year, or in 2 years; 3-items (0 = “no” to 9 = “very much”) | 0 – 37 | .87 | 6.82 | 7.01 |

| Lack of Parental Warmthn | Child Report of Parent Behaviors Inventory-30 (Schulderman & Schulderman, 1988), warmth subscale; 10-items (1= “like my parents” to 3= “not like my parents”) | 10 – 30 | .77 | 26.25 | 4.02 |

| Parental Approval of sexual activityn | Add Health (Resnick et al., 1997); parent approval of dating and sexual activity; 6-items (1= “strongly disapprove” to 5= “strongly approve”) | 6 – 54 | .83 | 23.70 | 7.04 |

| Sister Adol. Mothern | Self-report; (0 = “no” 1 = “yes”) | 0 – 1 | NA | 0.27 | 0.45 |

| Mother Adol. Mother | Self-report; (0 = “no” 1 = “yes”) | 0 – 1 | NA | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| Peer Adol. Mother | Self-report; (0 = “no” 1 = “yes”) | 0 – 1 | NA | 0.48 | 0.50 |

=neglect group significantly different from others, p<.05.

=physical abuse group significantly different from others, p<.05;

=sexual abuse group significantly different from others, p<.05;

α = internal consistency reliability; NA = clinical assessment tool, count variable, or no/yes variable; not amenable to alpha calculation; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; SAAQ = Sexual Attitudes and Activities Questionnaire;

Outcomes.

High-risk sexual behaviors were assessed via the Sexual Attitudes and Activities Questionnaire (SAAQ) at age 19 (Noll, Trickett, et al., 2003). Risky sexual behavior is a summed composite of: number of HIV risk behaviors (e.g., intercourse without a condom, condom failure during intercourse, intercourse or oral sex with an intravenous drug user, intravenous drug use, one night stands); age at first voluntary intercourse; number of sexually transmitted infections; number of sexual partners in the previous year; and number of additional risky sexual behaviors (e.g., number of lifetime partners with whom the adolescent engaged in unprotected sex, oral sex, sex while under the influence). Pregnancy at or before age 19 was assessed via self-reports at each annual assessment. Several efforts were made to add validity to self-reported pregnancy outcomes including assessing pregnancy history at multiple time points and assessing the accuracy of pregnancy confirmation (e.g., “missed my period” or “confirmed by doctor”). Motherhood at or before age 19 was determined via self-report at each annual assessment and subsequently confirmed via official medical charts once consent was secured to obtain labor and delivery records.

Covariates.

Demographic characteristics were assessed via caregiver reports of adolescent age, minority status, household income level, and adolescent self-report of the occurrence of 18 traumatic events in addition to maltreatment (e.g., loss, exposure to violence, etc.) assessed via the Comprehensive Trauma Interview (Barnes, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2009; Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003). A summation of these events indicates the number of alternative traumas experienced (sample range 0-18; =4.60; SD=2.96).

Data Analysis

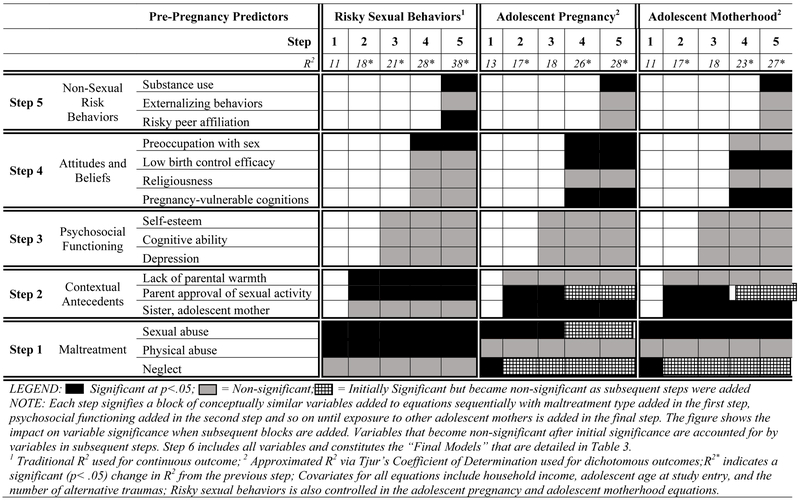

Zero-order associations were generated to demonstrate the magnitude of associations between pre-pregnancy predictors and outcomes: risky sexual behaviors, adolescent pregnancy and adolescent motherhood (Table 2). Pearson R coefficients were generated for the association between continuous variables, phi coefficients were generated for the association between dichotomous variables, and point-biserial coefficients were generated for associations between continuous and dichotomous variables (Davenport & El-Sanhury, 1991; Linacre, 2008). Predictor variables showing non-zero associations with one or more outcomes were elevated to hierarchical regression (HR) models (Figure 1) with covariates held constant (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). HR is a framework for model comparison where several regression models are systematically built by adding variables to a previous model in distinct steps; later models always include models from previous steps and indicate whether newly added variables result in a significantly improved proportion of explained variance. Thus, the relative contribution to the coefficient of determination, or R2, for each step can be evaluated. In the present analyses 5 distinct blocks of pre-pregnancy, alternative predictor variables were tested in ordered steps in groups that were formed to include conceptually similar constructs: Step 1: Maltreatment type; Step 2: Contextual antecedents; Step 3: Psychosocial functioning; Step 4: Attitudes and beliefs; and Step 5: Non-sexual risk behaviors. R2 values were evaluated to determine whether subsequent steps resulted in significant R2 change, suggesting that one or more of the predictor variables included in the previous step significantly contribute to the overall R2 after accounting for all other variables in the previous steps. Subsequent steps can result in changes to previously significant variables. This systematic approach illuminates which predictor variables account for overlapping variability in the dependent variables and which remain significant when in the company of other predictors.

Table 2.

Zero-order Associations between Alternative Explanatory Predictor Variables and Three Outcomes: Risky Sexual Behaviors, Adolescent Pregnancy, and Adolescent Motherhood (N= 435)

| Risky Sexual Behaviors |

Adolescent Pregnancy (N/Y) |

Adolescent Motherhood (N/Y) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-sexual Risk Behaviors | Externalizing behaviors | 0.21* | 0.16* | 0.08 |

| Substance use | 0.49* | 0.29* | 0.21* | |

| Risky peer affiliation | 0.42* | 0.22* | 0.17* | |

|

| ||||

| Attitudes & Beliefs | Preoccupation with sex | 0.34* | -0.03 | -0.01 |

| Low birth control efficacy | 0.12* | 0.20* | 0.16* | |

| Religiousness | -0.10* | -0.02 | -0.04 | |

| Pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions | 0.17* | 0.23* | 0.20* | |

|

| ||||

| Psychosocial Functioning | Self-esteem | -0.11* | -0.04 | -0.04 |

| Cognitive ability | -0.10 | -0.14* | -0.12* | |

| Depression | 0.17* | 0.08 | 0.05 | |

|

| ||||

| Contextual Antecedents | Sister was an adolescent mother (N/Y) | 0.07 | 0.17* | 0.21* |

| Mother was an adolescent mother (N/Y) | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.03 | |

| Friends are adolescent mothers (N/Y) | 0.05 | -0.03 | -0.04 | |

| Lack of parental warmth | 0.15* | 0.02 | 0.004 | |

| Parent approval of sexual activity | 0.33* | 0.20* | 0.17* | |

|

| ||||

| Maltreatment | Sexual abuse (N/Y) | 0.13* | 0.10* | 0.11* |

| Neglect (N/Y) | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.10* | |

| Physical abuse (N/Y) | 0.11* | 0.04 | -0.02 | |

|

| ||||

| Covariates | Household income | -0.12* | -0.13* | -0.11* |

| Age at study entry | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.13 | |

| Other traumas | 0.26* | 0.21* | 0.12* | |

= p < .05; Pearson R coefficients used for continuous variable associations, phi coefficients used for dichotomous (0 = “no”, 1 = “yes”; N/Y) variable associations, and point-biserial coefficients used for associations between continuous and dichotomous variables.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical Regressions of Risky Sexual Behaviors, Adolescent Pregnancy, & Adolescent Motherhood Regressed on Predictor Variables

R2 for linear regression was used as the coefficient of determination for the linear model for the continuous outcome (e.g., risky sexual behaviors; Cliff, 1987). Tjur’s Coefficient of Determination was used to approximate R2 for logistic models with dichotomous outcomes (i.e., pregnancy and motherhood; Tjur, 2009). This method uses the difference between the calculated mean of the predicted probabilities for each of the two categories of the dependent variable, has an upper bound of 1.0, and can be interpreted in a similar manner to traditional R2. Final models (see Table 3) include parameter estimates for models that include all steps and thus illuminate the most potent predictors.

Table 3.

Final Models

| Risky Sexual Behaviors a | Adolescent Pregnancy b | Adolescent Motherhood b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | SE | 95% CL | OR Point Estimate | 95% Wald CL | OR Point Estimate | 95% Wald CL | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Non-Sexual Risk Behaviors |

Substance use | 0.06 | 0.01 | (0.04, 0.09)* | 1.06 | (1.01, 1.10)* | 1.05 | (1.004, 1.10)* | ||||

| Externalizing behaviors | 0.003 | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.02) | 1.02 | (1.00, 1.05) | 1.01 | (0.97, 1.04) | |||||

| Risky peers | 0.03 | 0.01 | (0.01, 0.04)* | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.05) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Attitudes and Beliefs | Preoccupation with sex | 0.04 | 0.001 | (0.04, 0.05)* | 1.04 | (1.002, 1.23)* | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.004) | ||||

| Low birth control efficacy | 0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.02, 0.04) | 1.10 | (1.04, 1.16)* | 1.09 | (1.02, 1.16)* | |||||

| Religiousness | -0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.98 | (0.96, 1.003) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.03) | |||||

| Pregnancy-vulnerable cog | 0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.003, 0.03) | 1.04 | (1.11, 1.23)* | 1.03 | (1.12, 1.16)* | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Psychosocial Functioning | Self-esteem | 0.07 | 0.12 | (−0.17, 0.30) | 1.14 | (0.73, 1.78) | 1.20 | (0.72, 1.98) | ||||

| Cognitive ability | -0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.98 | (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.01) | |||||

| Depression | 0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.01) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.02) | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.02) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Contextual Antecedents | Low of parental warmth | 0.04 | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.08)* | 1.03 | (0.96, 1.10) | 1.02 | (0.94, 1.10) | ||||

| Parent approval of sex activity | 0.04 | 0.002 | (0.04, 0.05)* | 1.02 | (0.98, 1.07) | 1.02 | (0.97, 1.07) | |||||

| Sister, adolescent mother | 0.24 | 0.16 | (−0.09, 0.56) | 2.0 | (1.13, 3.54)* | 2.74 | (1.44, 5.22)* | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Maltreatment | Sexual abuse | 0.50 | 0.20 | (0.11, 0.87)* | 1.67 | (0.81, 3.45) | 2.45 | (1.35, 4.29)* | ||||

| Physical abuse | 0.48 | 0.21 | (0.06, 0.89)* | 1.39 | (0.63, 3.08) | 1.05 | (0.39, 2.82) | |||||

| Neglect | 0.37 | 0.28 | (−0.16, 0.91) | 1.93 | (0.75, 4.94) | 2.20 | (0.77, 6.28) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.27 | |||||||||

= significant at p<.05 (df= 19,415) for all models; Covariates included household income, adolescent age at study entry, and number of alternative traumas; Risky sexual behaviors also controlled in the adolescent pregnancy and adolescent motherhood models.

= logistic regression; 95% Wald CL = Wald Confidence Limits (used only for Logistic Regressions;

= linear regression;

NOTES:

Results

This sample has been described in prior publications (BLINDED FOR REVIEW). At enrollment (Time 1), the analytic sample was mean aged 15.3 years (SD = 1.07), had a median household income of between $30–39,000, and was 43% Caucasian, 48% African American, 8% Bi- or Multi-racial, 0.5% Hispanic, and 0.5% Native American. The majority (57%) lived in single-parent homes. Among the maltreated group, sexual abuse was experienced by 137 (43%), physical abuse by 89 (37%), and neglect by 40 (20%). There were no significant differences between groups with respect to age, household income, minority status, household makeup, and region of residence (zip code).

Additionally, although detailed birthrates for this sample have been published elsewhere (BLINDED FOR REVIEW), we thought it prudent—given that the focus of the current analysis is on differential pregnancy outcomes—to report additional details regarding outcomes of pregnancies for those who did not give birth. Of the 109 adolescents who reported at least one pregnancy (25% of the sample), 39 did not give birth (13 sexually abused; 12 physically abused; 5 neglected; 9 comparison). There were 32 reported miscarriages (10 sexually abused; 11 physically abused; 4 neglected; 7 comparison) and 7 reported abortions (3 sexually abused; 1 physically abused; 1 neglected; 2 comparison). There were no statistically significant differences among groups (maltreated versus comparison nor across maltreatment types) for rates of miscarriages or abortions.

Table 1 presents sample descriptive statistics and depicts maltreatment-type differences among alternative risk factors at the zero-order. Physically abused females showed higher externalizing behaviors and lower cognitive ability than other subgroups. Neglected females showed lower parental warmth, higher parental approval of sexual activity, and more often had a sister who was an adolescent mother. Sexually abused females were more likely to use substances, report more externalizing behaviors, affiliate with risky peers, have lower self-esteem, lower cognitive abilities, and higher depression symptoms. Table 2 shows association magnitudes between risk factors measured at Time 1 and subsequent age-19 outcomes. All variables, with the exception of having a mother or close friend who was an adolescent mother, showed zero-order associations with one or more outcome and were included as predictor variables in HR models.

For the three HR equations, Figure 1 shows the impact of each step on the R2 and which predictor variable reached significance in any given step (black signals significance, horizontal dashes signal non-significance). Checkered patterns signal a predictor variable that showed significance in one Step, but then dropped below significance in a subsequent Step. For example, neglect was a significant predictor of pregnancy in Steps 1, but dropped below significance in Step 2. Thus, although neglect is an important zero-order correlate of pregnancy, its predictive power falls to zero when contextual antecedents (namely parental approval of sexual activity and sister was a teen mom) are taken into account. In other words, neglected females are at high-risk for becoming pregnant, but this association is accounted for by the accompanying family contextual factors. Similarly, sexual abuse was a significant predictor of pregnancy in Steps 1, 2, and 3, but dropped below significance in Step 4 when attitudes and beliefs were added. This suggests that, although sexual abuse is strongly associated with pregnancy, preoccupation with sex, pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions, and low birth control efficacy are likely the driving factors behind this association. In contrast, sexual and physical abuse were important predictors of risky sexual behaviors in Step 1 and remained so throughout later steps. Sexual abuse also remained a potent predictor of motherhood throughout later steps.

Final models (depicted in the Step 5 columns of Figure 1 and in Table 3) demonstrate the most potent predictors of our outcomes, contributing unique variation above and beyond all other included variables. Sexual and physical abuse, risky peer affiliations, substance use, sexual preoccupation, parental approval of dating and sexual activity and a lack of parental warmth were all potent predictors accounting for 38% of the variation in risky sexual behaviors. Substance use, pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions, low birth control efficacy, sexual preoccupation, and having a sister who was an adolescent mother accounted for 28% of the variation in adolescent pregnancy. Sexual abuse, substance use, pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions, low birth control efficacy and having a sister who was an adolescent mother accounted for 27% of the variation in adolescent motherhood.

Discussion

The results reported here represent important advancements in understanding adolescent pregnancy and motherhood in several ways: the outcomes are rigorously obtained; the set of predictors is the most comprehensive to date and includes a large set of variables identified in previous literature as important correlates of adolescent sexual risk-taking that have been components, or targets, of existing prevention programs (Goesling, Colman, Trenholm, Terzian, & Moore, 2014); predictor variables were prospectively assessed to ensure temporal ordering and providing a clear delineation between pre-pregnancy alternative explanatory variables and subsequent outcomes; and the potential overlap in predictors is systematically tested to illuminate the most potent predictors of adolescent high-risk sexual behaviors, pregnancy, and motherhood.

Is there something unique about sexual abuse?

At the zero-order, all forms of child maltreatment correlated with one or more outcomes, but closer examination revealed that magnitudes were markedly diminished and/or fully accounted for when alternative risk factors were simultaneously considered. For example, substance use accounted for the same variance as neglect in the pregnancy and motherhood models suggesting that neglect in-and-of-itself does not necessarily elevate risk. Rather, substance use that co-occurs with neglect may be the mechanism by which neglected adolescents show inordinate risk for these outcomes and should be targeted for this type of maltreatment. Pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions and sexual preoccupation accounted for the same variance as sexual abuse in the pregnancy model, suggesting that sexually abused adolescents may adopt a positive or ambivalent stance to becoming a teen mother and/or become pregnant through increased sexual activity associated with sexual thoughts and fantasies, which in turn place them at risk for becoming pregnant.

Our hypothesis that sexual abuse would confer unique risk was confirmed when examining the outcome of adolescent motherhood; sexual abuse remained a significant contributor to the variation of adolescent motherhood even after the statistical control of multiple predictors. Findings indicated that sexually abused adolescents were 2.45 times more likely to become an adolescent mother as compared to those who did not experience sexual abuse even when all other risk factors were taken into account. This finding demonstrates the highly robust impact that sexual abuse can have on normative sexual development and the risk for becoming a teenage mother.

These finding indicate that sexual abuse impacts psychosocial development in ways that cannot be explained by other associated risk factors such as parental and socio-demographics, family characteristics, psychosocial functioning, attitudes and beliefs, other non-sexual risk behaviors, and even other forms so abuse and alternative traumatic experiences that might have also occurred during development. This suggest that there is indeed something unique about sexual abuse that should be taken into account when approaching the prevention of teen childbearing. Plausible mechanisms for such a connection likely span several levels of human experience including psychosexual maldevelopment, interpersonal and attachment disruptions, and biological sequelae.

Psychosexual maldevelopment.

In some obvious ways, the experience of sexual abuse differs from other forms of maltreatment because of its explicitly sexual nature. Theory articulating the specific avenues by which early sexual violation impacts development have not evolved much since Finkelhor and Brown put forth their Traumagenic Dynamics Model in 1985. This model outlined four basic tenets of victimization that can impact normative sexual development: (1) traumatic sexualization, where maladaptive scripts for sexual behavior are developed and reinforced because the child is coerced into, and rewarded for, sexual activity; (2) betrayal, when the child feels betrayed by a trusted protector and/or betrayed by others’ reactions to disclosure or a failure to stop the abuse; (3) stigmatization, when the victim internalizes excessive guilt and shame that can become emblematic of the “self” in future sexual situations; and (4) powerlessness, or an inability to control aspects of sexual relationships or to assert needs or desires (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). These four dynamics, in isolation or in combination, may influence later sexual risk behavior in terms of victims reluctantly agreeing to risky sexual activity, confusing sex with intimacy or love, difficulty in trusting others, and impairments in discerning exploitive partners. Victims may also see themselves as “damaged goods” or assumed to be highly promiscuous or unable to assert sexual limits and boundaries. Indeed, in a study of females being treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, aspects of this model were found to mediate risky sexual behaviors (Senn, Carey, & Coury-doniger, 2012).

In addition, sexual abuse may, in-and-of-itself, constitute a developmental discordance (Shanahan, 2000) where the victim lacks adequate emotional maturity to make sense of the exploitation and accommodate early sexual experiences into a larger developmental context. There are other aspects of sexual abuse that constitute developmental discordances as well. For example, sexually abused females were found to have entered puberty earlier than their non-abused counterparts (Noll et al., 2017). Early puberty is not only a risk factor for poor mental health and externalizing behavior problems in adolescence, but it has been shown to be correlated with early sexual debut and risky sexual behaviors (Cavanagh, 2004; Negriff & Susman, 2011).

Interpersonal and attachment disruptions.

It has been documented that sexual abuse victims endure subsequent sexual victimizations (Pittenger, Huit, & Hansen, 2016). One prospective study documented rates of domestic violence and rape and at 2 and 3 times (respectively) more than a matched comparison group who were not sexually abused (Barnes et al., 2009). This may indicate an over-affiliation with abusive partners where it might be difficult to negotiate condom use, for example, and an inability to navigate situations in which there is a power differential in the dynamics of sexual consent.

Attachment disruptions have also been documented in sexual abuse survivors such that dyadic relationships are characterized as insecure attachments, specifically anxious and/or avoidant (Kwako, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2010). Not only might this manifest in dysfunctional romantic attachments, but when insecurity is high, sexual behaviors may be more directly motivated by attachment needs for reassurance and intimacy than by personal needs. Attachment insecurity may also help explain why sexual abuse was such a strong predictor of adolescent motherhood (as opposed to adolescent pregnancy) in the present study. Perhaps sexual abuse survivors view having a baby as somehow reparative of damaged relationships with loved ones, or that becoming a mother will somehow create an unbreakable bond. However, this phenomenon needs more research before these assertions can be made, especially if alternative, more parsimonious explanations would account the motivation to bring a pregnancy to term—a lack of access to reproductive services or religion and cultural beliefs, for example.

Biologic sequelae.

Early life adversity and trauma impact the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis in ways that can manifest in permanent changes to the stress-response system characterized by marked attenuation or blunting (McEwen & Seeman, 1999). This phenomena has been explicitly observed over the life course of sexual abuse survivors (Trickett, Noll, Susman, Shenk, & Putnam, 2010). A theoretical model has been proposed stipulating that disruptions in the HPA axis reduce one’s ability to recognize, react and effectively respond to sexual threats thus helping to explain the high rates of victimization experienced by sexual abuse survivors (Noll & Grych, 2011). In this model, the physiological reaction elicited by threats of imminent harm to the self are muted which has the potential to disrupt cognitive processing and coping behavior precluding adaptive responding. Hence, this model may help explain why sexual abuse survivors engage in more sexual risk-taking and why they may be inefficient at protecting themselves and negotiating safe and healthy sexual relations. In brain imaging studies, Heim and colleagues (2013) found a thinning of the genital somatosensory cortex in women with a history of sexual abuse which they hypothesize will help explain a heightened sexual activity and promiscuity. While this finding is indeed intriguing, it is in need of replication.

Additional Risk Factors to Target

Many risk factors have been shown to correlate with adolescent pregnancy, but, as demonstrated in Table 2, not all risk factors correlate with all three outcomes, nor do zero-order correlations necessarily prognosticate outcomes in multivariate systems. For example, parental approval of sexual activity and a lack of parental warmth are important predictors of high-risk sexual behavior at the zero-order, but have little effect on adolescent pregnancy and motherhood when considered in the context of the larger set of risk factors. Psychosocial factors, such as self-esteem and psychological well-being, have little effect on any outcome when considered together with low birth control efficacy and substance use for example.

On the other hand, several risk factors indeed emerged as important despite accounting for others. Pregnancy-vulnerable cognitions, or as an inability to discern negative consequences of motherhood and an expressed desire to become a young mother, may signal a lack of receptiveness to more traditional messaging around efficacy and sexual health (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2013). These individuals may view motherhood as being accompanied by increased social status and as their next logical station in life (East, 1998). Prevention programs that encourage adolescents to form multiple avenues towards gaining status (e.g., through participation in sports and the arts), and promote alternative life course options (e.g., matriculation, job training, career guidance) may increase the efficacy of extant pregnancy prevention programming. Finally, findings confirm the power of a family milieu that includes a sister who was an adolescent mother, suggesting that targeting younger siblings of adolescent mothers may be a vitally important prevention strategy (Anand & Kahn, 2013; East, Khoo, & Reyes, 2006; East et al., 2007).

Limitations

Despite the methodological rigor of this prospective, longitudinal study, which included a comprehensive set of pre-pregnancy predictors, there are several limitations. Hispanic adolescents, who have the highest rate of adolescent pregnancy in the U.S. are underrepresented in this sample (Hamilton, Martin, Osterman, Curtin, & Matthews, 2015). This study only considered substantiated cases of maltreatment and may underestimate the effects for adolescents whose maltreatment goes undisclosed or unsubstantiated. Finally, despite the comprehensive set of predictors previously identified in the literature as being important targets for prevention, only 27–38% of the variation in outcomes was accounted for, underscoring that adolescent risky sexual behavior, pregnancy and motherhood are complex processes that are far from fully understood.

Conclusions

This study is unique in its prospective design, comprehensive assessment of pre-pregnancy predictors, and the systematic demonstration of how testing the relative potency of these predictors can add efficiency and precision to adolescent pregnancy prevention efforts. Results suggest that existing adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection prevention programs, which generally target a large set of constructs (including sexuality education, contraception efficacy, accessing services, motivations, mental health, peer influences, parent involvement, and other risk factors), could be substantially streamlined and/or optimized by a greater focus on the most potent risk factors. Given that there are approximately 31 such programs that have been identified with some evidence of effectiveness (Goesling et al., 2014), policymakers and practitioners need practical guidance in identifying individual prevention programs to adopt for broad dissemination (Office of Adolescent Health, 2013; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 2012).

Results also suggest that prevention programs should recognize the unique issues that sexual trauma confers on risk for becoming a young mother. Clinicians delivering interventions designed to treat sexual abuse, such as Trauma Focuses Cognitive Behavior Therapy (TF-CBT; Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer, 2011), should likewise be cognizant of the risk for adolescent motherhood that these victims face. There is recent momentum to study trauma and maltreatment in conglomerate form and lump all types of stressors into single categories of “toxic stress” (Van der Kolk, 2015), “adverse childhood experience” (Felitti et al., 1998), or polyvictimization (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2011). While this type of research is no doubt important in advancing our knowledge of stress and victimization, results reported here suggest that there are notable exceptions, and that studying trauma-specific domains (i.e., sexual abuse) may illuminate important disparities (i.e., teen pregnancy and HIV). Admittedly, this kind of work will be difficult given the high rates of polyvictimization among maltreated children (Vachon et al., 2015), yet if we refrain from attempting to disentangle unique effects of differing types of maltreatment, we will lose vital information needed to design or tailor interventions targeting trauma- specific issues. Given that over 50,000 children are known victims of sexual abuse each year in the U.S. and approximately 1 in 4 women will be sexually abused prior to age 18, the findings herein suggests that intervening with sexual abuse victims directly could have a substantial impact on national adolescent motherhood rates (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2014; DHHS, 2017).

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This research was supported in part by grants awarded Noll by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award R01HD052533 and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number 5UL1TR001425–02. Guastaferro, Reader, & Rivera were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P50 DA039838 and T32DA017629. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, & Kahn LB (2013). The Effect of Teen Pregnancy on Siblings’ Sexual Behavior, 23. Retrieved from http://som.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Siblings_4_18_13(1).pdf

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assini-Meytin LC, & Green KM (2015). Long-term consequences of adolescent parenthood among African American urban youth: A propensity matching approach. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 529–535. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.005.Long-term [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & Trickett PK (2009). Sexual and physical revictimization among victims of severe childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(7), 412–420. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, & Burns LJ (1998). Adolescents, health, and school: Early analyses from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 82(601), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Benson JE, & Elder GH (2011). Young adult identities and their pathways: A developmental and life course model. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1646–1657. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.017.Two-stage [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Wiggins M, Fletcher A, & Allen E (2014). Do family factors protect against sexual risk behaviour and teenage pregnancy among multiply disadvantaged young people? Findings from an English longitudinal study. Sexual Health, 11(3), 265–273. 10.1071/SH14005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Chen H, Smailes E, & Johnson JG (2004). Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP, 25(2), 77–82. 10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE (2004). The Sexual Debut of Girls in Early Adolescence: The Intersection of Race, Pubertal Timing, and Friendship Group Characteristics. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(3), 285–312. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.00076.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Schootman M, Cottler LB, & Bierut LJ (2013). Characteristics of sexually active teenage girls who would be pleased with becoming pregnant. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(3), 470–476. 10.1007/s10995-012-1020-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliff N (1987). Analyzing Multivariate Data. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, Franklin C, Bennett P, Corcoran J, Franklin C, & Bennett P (2000). Ecological factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Social Work Research, 24(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cox RB, Shreffler KM, Merten MJ, Schwerdtfeger Gallus KL, & Dowdy JL (2015). Parenting, peers, and perceived norms: What predicts attitudes toward sex among early adolescents? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(1), 30–53. 10.1177/0272431614523131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport E, & El-Sanhury N (1991). Phi/Phimax: Review and Synthesis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 821–828. [Google Scholar]

- Davies SL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Crosby RA, & Sionean C (2003). Pregnancy desire among disadvantaged African American adolescent females. American Journal of Health Behavior, 27(1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Runyon MK, & Steer RA (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression & Anxiety, 28(1), 67–75. 10.1002/da.20744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL (1998). Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and Families, 60(1), 150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Chien NC, & Barber JS (2012). Adolescents’ pregnancy intentions, wantedness, and regret: Cross-lagged relations with mental health and harsh parenting. Journal of Marriage and Families, 74(1), 167–185. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00885.x.Adolescents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Khoo ST, & Reyes BT (2006). Risk and Protective Factors Predictive of Adolescent Pregnancy: A Longitudinal, Prospective Study. Applied Developmental Science, 10(4), 188–199. 10.1207/s1532480xads1004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Reyes BT, & Horn EJ (2007). Association between adolescent pregnancy and a family history of teenage births. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(2), 108–115. 10.1363/3910807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, & Browne A (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55(4), 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Ormrod R, & Hamby SL (2011). Polyvictimization in developmental context. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4, 291–300. 10.1080/19361521.2011.610432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, & Hamby SL (2014). The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(3), 329–333. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garwood SK, Gerassi L, Jonson-Reid M, Plax K, & Drake B (2015). More than poverty - Teen pregnancy risk and reports of child abuse reports and neglect. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 164–168. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.004.More [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, Terzian M, & Moore K (2014). Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 499–507. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Joyner K, Udry JR, & Suchindran C (2000). Smart teens don’t have sex (or kiss much either). Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 213–225. 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Udry JR, & Suchindran C (1997). Testosterone predicts initiation of coitus in adolescent females. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, & Matthews TJ (2015). National Vital Statistics Reports Births : Final Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports, 64(12), 1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1988). Manual for the perceived competence scale for adolescence. Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SM, & Berkley-Patton JY (2014). Religiosity and risky sexual behaviors among an African American church-based population. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), 469–482. 10.1007/s10943-012-9651-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim CM, Mayberg HS, Mletzko T, Nermoff CB, & Pruessner JC (2013). Decreased cortical representation of genital somatosensory field after childhood sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 616–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich CM, & McWey LM (2014). Substance use and delinquency: High-risk behaviors as predictors of teen pregnancy among adolescents involved with the child welfare system. Journal of Family Issues, 35(10), 1322–1338. 10.1177/0192513X13478917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw BSK, & Feivelson DJ (2000). Teenage abortion and pregnancy statistics by state, 1996. Family Planning Perspectives, 32(6), 272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, & Marchbanks PA (2001). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives, 33(5), 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi LB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, & Zeiders KH (2016). Trajectories of Developmental Functioning Among Children of Adolescent Mothers: Factors Associated With Risk for Delay. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(4), 346–363. 10.1352/1944-7558-121.4.346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R (2018). Reflections on six decades of research on adolescent behavior and development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–4. 10.1007/s10964-018-0811-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2005). Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2004. Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana A, & Cooksey EC (2012). Examining the effect of maternal sexual communication and adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval on adolescent risky sexual involvement. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(6), 557–565. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian-Farrell C, Rizo CF, Lombardi BM, Meltzer-Brody S, & Bledsoe SE (2017). Traumatic experience, polytraumatization, and perinatal depression in a diverse sample of adolescent mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–24. 10.1177/0886260517726410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & Trickett PK (2010). Childhood sexual abuse and attachment: An intergenerational perspective. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(3), 407–22. 10.1177/1359104510367590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Fontaine RG, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (2014). Peer rejection, affiliation with deviant peers, delinquency, and risky sexual behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(10), 1742–1751. 10.1007/s10964-014-0175-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, & Bates JE (2010). Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 190–194. 10.1177/1077559509352359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (2007). Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatment, 12(3), 233–245. 10.1177/1077559507301841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM, Shearer CL, & Boone TL (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 150–159. 10.1080/00224490409552223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre J (2008). The expected value of a point-biserial (or similar) correlation. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 22(1), 1154. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, PhD., Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, PhD., (2017). Births: Final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports (Vol. 66). Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Seeman T (1999). Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennen FE, Kim K, & Trickett PK (2010). Child neglect: Definition and identification of youth’s experiences in official reports of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(9), 647–658. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.007.Child [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC (2002). Family Influences on Adolescent Sexual and Contraceptive Behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 39(1), 22–26. 10.1080/00224490209552115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More DM (1953). Developmental concordance and discordance during puberty and early adolescence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 18(1), 1–128. 10.1080/03004430801902296.Dondi [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, & Trickett PK (2015). Child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior: Maltreatment types and gender differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 36(9), 708–716. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000204.Child [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, & Susman EJ (2011). Pubertal timing, depression, and externalizing problems: A framework, review, and examination of gender differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(3), 717–746. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00708.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, & Grych JH (2011). Read-react-respond : An integrative model for understanding sexual revictimization. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 202–215. 10.1037/a0023962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Horowitz LA, Bonanno GA, Trickett PK, & Putnam FW (2003). Revictimization and Self-Harm in Females Who Experienced Childhood Sexual Abuse Results From a Prospective Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(12), 1452–1471. 10.1177/0886260503258035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, & Putnam KT (2009). Childhood sexual abuse and adolescent pregnancy: A meta-analytic update. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(4), 366–378. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, Long JD, Negriff S, Susman EJ, Shalev I, … Putnam FW. (2017). Childhood Sexual Abuse and Early Timing of Puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 65–71. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, & Putnam FW (2003). A prospective investigation of the impact of childhood sexual abuse on the development of sexuality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 575–586. 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Adolescent Health. (2013). Evidence-Based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Programs. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/teen_pregnancy/db/31-effective-tpp-progams.pdf

- Pittenger SL, Huit TZ, & Hansen DJ (2016). Applying ecological systems theory to sexual revictimization of youth: A review with implications for research and practice. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 26, 35–45. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polacsek M, Celentano DD, O’Campo P, & Santelli JS (1999). Correlates of condom use stage of change : Implications for intervention. AIDS Education and Prevention, 11(1), 38–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan J. a, Tan LH., Steele A., & Black K. (2004). Impact of demographic factors, early family relationships and depressive symptomatology in teenage pregnancy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 197–203. 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, … Udry JR (1997). From Harm Longitudinal Study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Pazol K, Warner L, Cox S, Kroelinger C, Besera G, … Barfield W (2016). Reduced disparities in birth rates among teens aged 15 – 19 years -- United States, 2006 – 2007 and 2013 – 2014. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 409–414. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6516a1.htm#suggestedcitation [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, & Middlestadt S (2004). Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(3), 200–208. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulderman E, & Schulderman S (1988). Questionnaire for children and youth (CRPBI-30). Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Winnepeg. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, & Singh S (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: Levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 223–230. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, & Coury-doniger P (2012). Mediators of the relation between childhood sexual abuse and women’s sexual risk behavior: A comparison of two theoretical frameworks. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 1363–1377. 10.1007/s10508-011-9897-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ (2000). Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Reviews of Sociology, 26, 667–692. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shenk CE, Noll JG, Peugh JL, Griffin AM, & Bensman HE (2015). Contamination in the prospective study of child maltreatment and female adolescent health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(March 2015), 37–45. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed). Boston: Pearson International Edition. [Google Scholar]

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2012). What Works 2011– 2012: Curriculum-based Programs That Help Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Lewis T, Neilson EC, English DJ, Litrownik AJ, Margolis B, … Dubowitz H (2017). Child maltreatment and risky sexual behavior: Indirect effects through trauma symptoms and substance use. Child Maltreatment, 22(1), 69–78. 10.1177/1077559516674595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjur T (2009). Coefficients of determination in logistic regression models- A new proposal: The coefficient of discrimination. The American Statistician, 63, 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, & Cicchetti D (2013). A developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 18(3), 135–139. 10.1177/1077559513500380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, Susman EJ, Shenk CE, & Putnam FW (2010). Attenuation of cortisol across development for victims of sexual abuse. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children Youth and Families, & Children’s Bureau. (2017). Child Maltreatment 2015. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Rogosch FA, & Cicchetti D (2015). Assessment of the Harmful Psychiatric and Behavioral Effects of Different Forms of Child Maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry, E1–E9. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wall-Wieler E, Roos LL, & Nickel NC (2018). Adolescent pregnancy outcomes among sisters and mothers : A population-based retrospective cohort study using linkable administrative data. Public Health Reports, 133(1), 100–108. 10.1177/0033354917739583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, & Kuhns JB (1996). Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health, 86(11), 1607–1612. 10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Mitchell O, & MacKenzie DL (2014). Drug Courts’ Effects on Criminal Offending In Bruinsma G & Weisburg D (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 1170–1178). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, & Mather N (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward L, Fergusson DM, & Horwood LJ (2001). Risk factors and life processes associated with teenage pregnancy: Results of a prospective study from birth to 20 years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1170–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington EL, Berry JT, Hsu K, Gowda KK, Bleach E, & Bursley KH (1989). Measuring religious values: Factor analytic study of the religious values survey In American Psychological Association. Richmond, VA. [Google Scholar]