Abstract

Objectives

Recently, the Hospital Frailty Risk Score based on a derivation and validation study in the UK has been proposed as a low-cost, systematic screening tool to identify older, frail patients who are at a greater risk of adverse outcomes and for whom a frailty-attuned approach might be useful. We aimed to validate this Score in an independent cohort in Switzerland.

Design

Secondary analysis of a prospective, observational study (TRIAGE study).

Setting

One 600-bed tertiary care hospital in Aarau, Switzerland.

Participants

Consecutive medical inpatients aged ≥75 years that presented to the emergency department or were electively admitted between October 2015 and April 2018.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary endpoint was all-cause 30-day mortality. Secondary endpoints were length of hospital stay, hospital readmission, functional impairment and quality of life measures. We used multivariate regression analyses.

Results

Of 4957 included patients, 3150 (63.5%) were classified as low risk, 1663 (33.5%) intermediate risk, and 144 (2.9%) high risk for frailty. Compared with the low-risk group, patients in the moderate risk and high-risk groups had increased risk for 30-day mortality (OR (OR) 2.53, 95% CI 2.09 to 3.06, p<0.001 and OR 4.40, 95% CI 2.94 to 6.57, p<0.001) with overall moderate discrimination (area under the ROC curve 0.66). The results remained robust after adjustment for important confounders. Similarly, we found longer length of hospital stay, more severe functional impairment and a lower quality of life in higher risk group patients.

Conclusion

Our data confirm the prognostic value of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score to identify older, frail people at risk for mortality and adverse outcomes in an independent patient population.

Trial registration number

NCT01768494; Post-results.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, risk management, preventive medicine

Strength and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to validate the Hospital Frailty Risk Score following its publication and initial validation.

The validation in a Swiss Tertiary care hospital is the first step in assessing the applicability of the risk score in multinational settings.

In addition to associations with adverse clinical outcomes, we assess associations of higher hospital frailty risk scores with functional impairment, quality of life and need for postacute care.

Due to the study design, there was no routine frailty assessment in our patients and we were not able to compare the score with other frailty assessments or screening scores.

As the score is dependent on documentation and coding of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, variation in coding could contribute to misclassification.

Introduction

With the increase in the ageing, multimorbidity patient population, the proportion of frail patients is expected to further raise.1 Frailty describes a state of increased risk for decline in health after an exposure to a stressor event (eg, hospitalisation for an acute illness) increasing the risk for adverse events such as falls, delirium, disability and death.2–4 Importantly, identifying patients at risk for frailty early during the course of hospitalisation may help to improve treatment strategies including a comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve the care and outcomes of patients.5

Several tools to identify frailty have been developed in the last 20 years.6 Yet none has emerged as a gold standard. Current instruments show only a moderate power to identify frailty,7 and some tools require time-consuming manual assessment.8 9 Moreover, in most hospitals, there is no routine assessment of older patients and only a subset of patients is screened for frailty.6 For these reasons, patients who may benefit from a specific frailty-directed treatment approach may be missed in usual hospital care. To improve the care of frail patients, the recently published Hospital Frailty Risk score10 was developed for early identification of patients with characteristics of frailty, who are at risk of adverse healthcare outcomes and who could be identified without any additional assessment apart from routinely collected data. The score relies on the diagnostic codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), a coding system that is implemented in many administrative hospital databases worldwide. This provides the opportunity to systematically screen older patients in a low-cost manner.10 In a three-step approach, this score was developed and later validated within three patient populations from the UK showing high prognostic performance. Still, international validation is needed before the more wide-spread use of this score in other healthcare systems. Herein, we aimed to validate the Hospital Frailty Risk Score in a Swiss tertiary care hospital. We investigated associations of the score with adverse clinical outcomes such as 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay and 30-day readmission, as well as functional outcomes including functional impairment, quality of life and discharge location.

Methods

Study design and study population

This is a secondary analysis of the TRIAGE study, a prospective, observational cohort study initially designed to understand the value of admission biomarkers to predict later adverse outcomes.11 12 We included consecutive medical patients presenting with a medical urgency at the Kantonsspital in Aarau (Switzerland), a 600-bed tertiary care hospital with most medical admissions entering the hospital over the ED. As an observational quality control study, the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the hospital approved the study and waived the need for individual informed consent (main Swiss IRB: Ethikkommission Kanton Aargau (EK 2012/059). The study was registered at the ‘ClinicalTrials.gov’ registration website (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01768494) and the study protocol has been published previously.13

In accordance with the initial study, we selected medical inpatients aged ≥75 years that were admitted between October 2015 and April 2018. The cohort includes elective and emergency admissions. In case of multiple admissions of the same patient, only the first admission was used for the analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question or the design of the study.

Follow-up and initial data collection

We used ICD-10 diagnostic codes of the incident admission assigned to patients after discharge by professional hospital coders according to the information of medical records. The electronic records contained up to 38 diagnosis fields coded according to ICD-10. Regarding follow-up, 30 days after hospital admission, patients were contacted by telephone for a structured interview to obtain information on vital status, clinical outcomes, location of living and functional measurements. Functional status was obtained using the EQ-5D-3L standardised measure of health, which was administered as recommended.14 We assessed mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety and depression, using dichotomized data with levels 2 and 3 indicating ‘impairment’ and level 1 indicating ‘no impairment’. Moreover, we used the EQ-VAS, recording the self-rated health on a visual analogue scale with values between 0 and 100 with higher points indicating better health states.

We used the Barthel Index to measure activities of daily living (ADL),15 with a cutoff <95 points indicating functional impairment. We assessed readmission to any facility, location after discharge and identified patients who were living at home before hospital admission and were discharged to a location other than home.

All information was stored in a centralised, password-secured database (SecuTrial; interActive Systems GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Calculation of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score

For each patient, the Hospital Frailty Risk Score was calculated retrospectively using all available ICD-10 diagnostic codes that were documented for the particular admission as recommended.10 The score is an aggregate of 109 ICD-10 diagnostic codes that were found to be associated with frailty risk. Each of these ICD-10 diagnostic codes was awarded with specific values proportional to how strongly they predicted frailty. According to the aggregate score, patients were divided into the three frailty risk categories low risk (<5 points), intermediate risk (5–15 points) and high risk (>15 points) as recommended.10

Research aims and statistical approach

We investigated associations of the Hospital Frailty Risk with adverse clinical outcomes. Our primary endpoint is all-cause 30-day mortality. Secondary endpoints include hospital length of stay, long hospital stay (>10 days) and hospital readmission within 30 days. Moreover, we examined associations with functional impairment using the Barthel Index (<95 points indicating impairment), Quality of Life measurements using the EQ-5D standardised measure and discharge location other than home for patients who were living at home before admission.

Statistical analysis

We expressed patient characteristics using descriptive statistics including mean with SD, median with IQR and frequencies, as appropriate. Frequency comparison was done using the χ2 test.

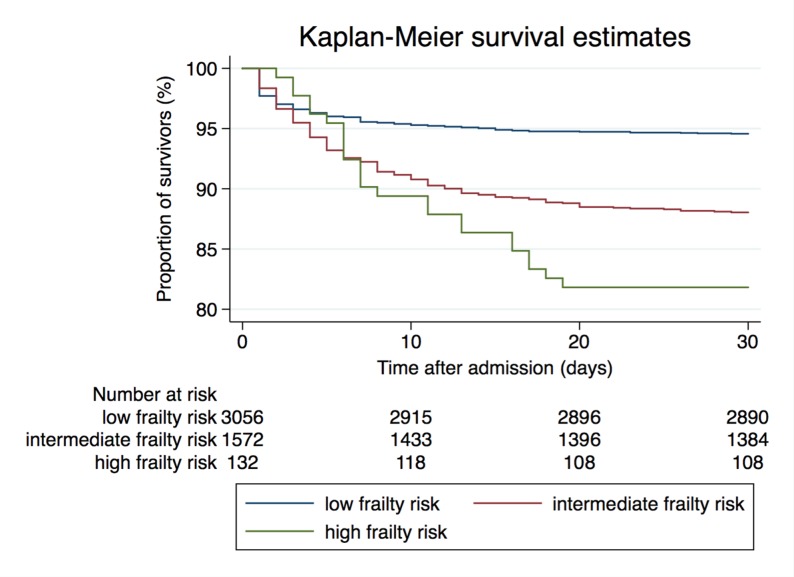

To investigate associations of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score with outcomes, we used univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Models were adjusted for age (model 1), age and gender (model 2), and age, gender and comorbidities that were not included in the calculation of the frailty risk score (model 3). We performed another analysis adjusting for the structured early warning score NEWS (national early warning score) to comprise physiological parameters that might be an important modifier of outcomes. NEWS was calculated retrospectively as recommended16 based on admission data. We provide ORs or regression coefficients (RCs) with 95% CIs as appropriate. We used receiver operating statistics reporting area under the curve (AUC) as a measure of discrimination. We considered AUCs of 0.6–0.7 as moderate, 0.7–0.8 as fair, 0.8–0.9 as good, and >0.9 as excellent. Also, for graphical illustration we generated Kaplan-Meier survival estimates stratified by frailty risk groups.

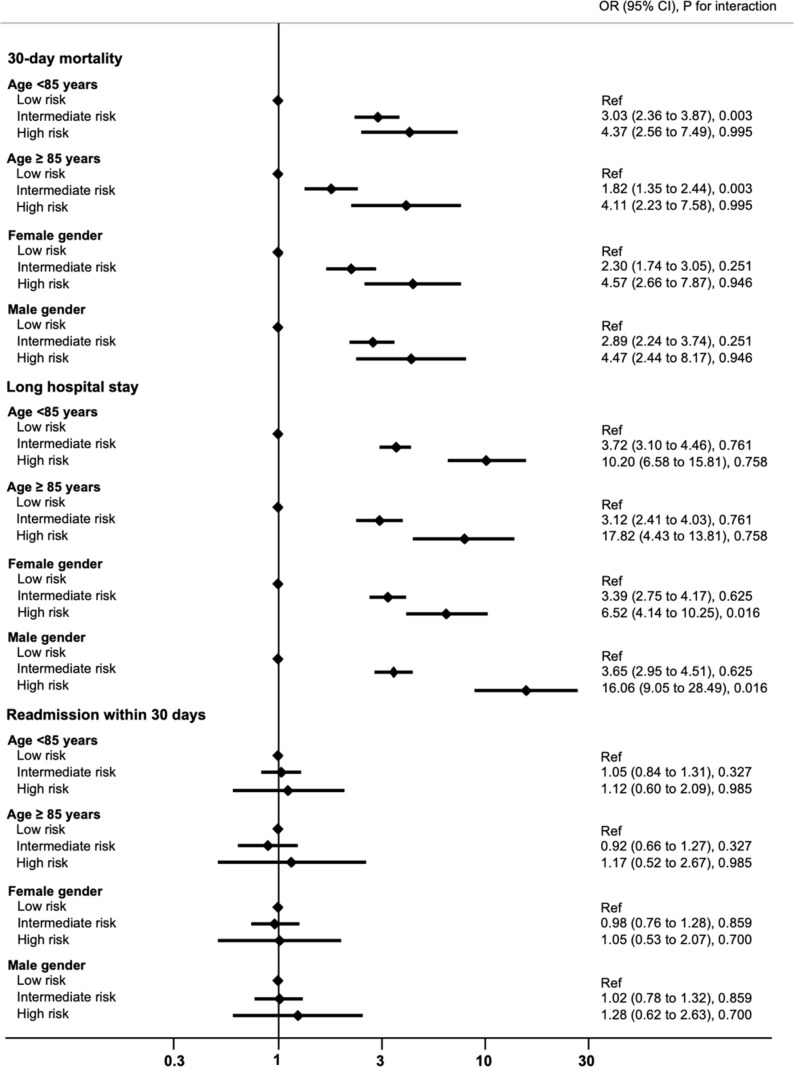

We repeated analyses in predefined subgroups stratified by age and gender.

All tests were two-tailed and carried out at 5% significance levels. Analyses were performed with STATA V.12.1.

Results

Patient population

A total of 4957 patients with a median age of 82 years were included in this analysis. At the time of admission, the majority of patients (63.4%) resided at home. A total of 63.5% (3150) of patients were in the low frailty risk group, 33.5% (1663) in the intermediate risk group and 2.9% (144) were in the high-risk group. Minimum score was 0 points, maximum score 30.3 points, quartiles were 1.4, 3.4 and 6.7 points, mean 4.5 points (SD 4.3). Baseline characteristics of the general population and stratified by Hospital Frailty Risk categories are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total cohort and stratified by the frailty risk group

| Characteristics | Total cohort | Frailty risk (points) | P value | ||

| Low risk (<5) | Intermediate risk (5–15) | High risk (>15) | |||

| N (%) | 4957 | 3150 (63.5%) | 1663 (33.5%) | 144 (2.9%) | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 2426 (49.0%) | 1634 (52.0%) | 733 (44.2%) | 59 (41.0%) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 82 (78, 86) | 82 (78, 85) | 83 (79, 87) | 83 (79, 87) | <0.001 |

| Vital signs, median (IQR) | |||||

| Blood pressure systolic (mm Hg) | 148 (129, 168) | 149 (131, 168) | 147 (125, 166) | 151 (132, 176.5) | 0.007 |

| Blood pressure diastolc (mm Hg) | 80 (68, 93) | 80 (69, 93) | 80 (68, 92) | 80 (69, 97) | 0.25 |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 81.5 (70, 95.2) | 80.5 (69, 94.8) | 82 (70.9, 96) | 85 (73, 101) | 0.009 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 95.8 (92.8, 98) | 96 (93.5, 98) | 95.4 (92.1, 97.6) | 95.05 (92, 97.4) | <0.001 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.8 (36.4, 37.3) | 36.8 (36.4, 37.3) | 36.8 (36.4, 37.4) | 36.6 (36.4, 37.1) | 0.007 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 698 (14.1%) | 486 (15.4%) | 205 (12.3%) | 7 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Malignant disease | 494 (10.0%) | 354 (11.2%) | 131 (7.9%) | 9 (6.2%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 699 (14.1%) | 436 (13.8%) | 249 (15.0%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.17 |

| COPD | 257 (5.2%) | 178 (5.7%) | 75 (4.5%) | 4 (2.8%) | 0.099 |

| Dementia | 338 (6.8%) | 104 (3.3%) | 218 (13.1%) | 16 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 1282 (25.9%) | 715 (22.7%) | 540 (32.5%) | 27 (18.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2608 (52.6%) | 1726 (54.8%) | 826 (49.7%) | 56 (38.9%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 531 (10.7%) | 424 (13.5%) | 100 (6.0%) | 7 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 668 (13.5%) | 193 (6.1%) | 396 (23.8%) | 79 (54.9%) | <0.001 |

| Location prior to admission, n (%) | |||||

| Home | 3144 (63.4%) | 2194 (69.7%) | 895 (53.8%) | 55 (38.2%) | <0.001 |

| Home with assistance service | 264 (5.3%) | 107 (3.4%) | 142 (8.5%) | 15 (10.4%) | |

| Nursing home | 370 (7.5%) | 161 (5.1%) | 190 (11.4%) | 19 (13.2%) | |

| Other hospital | 457 (9.2%) | 275 (8.7%) | 161 (9.7%) | 21 (14.6%) | |

| Unknown or other | 722 (14.6%) | 413 (13.1%) | 275 (16.5%) | 34 (23.6%) | |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Associations of frailty risk score with mortality

A total of 524 (10.7%) patients died within 30 days of admission, consisting of 221 (7.1%) of those in the low-risk group, 267 (16.2%) in the intermediate-risk group and 36 (25.2%) in the high-risk group. Regression analyses showed corresponding ORs of 2.53 (95% CI 2.09 to 3.06, p<0.001) for the intermediate-risk group and 4.40 (95% CI 2.94 to 6.57, p<0.001) for the high-risk group, respectively, compared with the low-risk group. Results remained robust after adjustment for confounders (age, gender and comorbidities not included in the score) (table 2, figure 1).

Table 2.

Associations of elevated frailty risk groups with adverse clinical outcomes the low frailty risk group

| Outcome | Overall, n (%) | Low risk, n (%) | Intermediate risk, n (%) | High risk, n (%) | P value | Intermediate risk, OR (95% CI), P value | High risk, OR (95% CI), P value | ||

| Unadjusted | Fully adjusted | Unadjusted | Fully adjusted | ||||||

| All-cause 30-day mortality | 524 (10.7%) | 221 (7.1%) | 267 (16.2%) | 36 (25.2%) | <0.001 | 2.53 (2.09 to 3.06), p<0.001 | 2.65 (2.17 to 3.25), p<0.001 | 4.4 (2.94 to 6.57), p<0.001 | 4.83 (3.17 to 7.37), p<0.001 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR)* | 5 (2, 9) | 4 (2, 7) | 7 (4, 12) | 11.5 (7, 18) | <0.001 | 3.74 (3.34 to 4.14), p<0.001 | 3.77 (3.39 to 4.15), p<0.001 | 10.04 (8.92 to 11.16), p<0.001 | 10.07 (9.02 to 11.13), p<0.001 |

| Long hospital stay >10 days | 1010 (20.4%) | 386 (12.3%) | 543 (32.7%) | 81 (56.2%) | <0.001 | 3.47 (2.99 to 4.02), p<0.001 | 3.66 (3.14 to 4.28), p<0.001 | 9.21 (6.51 to 13.01), p<0.001 | 9.75 (6.83 to 13.92), p<0.001 |

| 30-day readmission | 586 (11.8%) | 372 (11.8%) | 195 (11.7%) | 19 (13.2%) | 0.87 | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.24), p=0.643 | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24), p=0.69 | 1.47 (0.95 to 2.26), p=0.081 | 1.67 (1.08 to 2.59), p=0.022 |

| Functional impairment, n (%) | |||||||||

| Barthel Index, median (IQR)* | 95 (70, 100) | 100 (85, 100) | 80 (55, 100) | 50 (20, 75) | <0.001 | −15.76 (-17.87 to −13.64), p<0.001 | −14.59 (-16.69 to −12.48), p<0.001 | −40.55 (-47.01 to −34.09), p<0.001 | −39.7 (-46.06 to −33.33), p<0.001 |

| Barthel Index <95 points | 1052 (46.5%) | 529 (36.3%) | 472 (62.9%) | 51 (92.7%) | <0.001 | 2.98 (2.48 to 3.58), p<0.001 | 2.87 (2.37 to 3.47), p<0.001 | 22.37 (8.04 to 62.23), p<0.001 | 25.03 (8.91 to 70.32), p<0.001 |

| Quality of life, n(%) | |||||||||

| Impairment of mobility | 408 (18.0%) | 162 (11.1%) | 217 (28.9%) | 29 (51.8%) | <0.001 | 3.25 (2.59 to 4.08), Pp<0.001 | 3.1 (2.46 to 3.92), p<0.001 | 8.61 (4.97 to 14.91), p<0.001 | 8.45 (4.82 to 14.81), p<0.001 |

| Impairment of self-care | 1010 (44.5%) | 480 (32.9%) | 484 (64.4%) | 46 (82.1%) | <0.001 | 3.69 (3.07 to 4.44), p<0.001 | 3.63 (2.99 to 4.4), p<0.001 | 9.40 (4.7 to 18.79), p<0.001 | 9.59 (4.74 to 19.41), p<0.001 |

| Impairment of usual activities | 1366 (60.2%) | 767 (52.5%) | 553 (73.5%) | 46 (82.1%) | <0.001 | 2.51 (2.08 to 3.05), p<0.001 | 2.35 (1.92 to 2.87), p<0.001 | 4.16 (2.08 to 8.31), p<0.001 | 3.98 (1.97 to 8.06), p<0.001 |

| Pain/discomfort | 910 (42.7%) | 574 (40.8%) | 314 (46.3%) | 22 (48.9%) | 0.039 | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.51), p=0.017 | 1.21 (1 to 1.47), p=0.047 | 1.39 (0.77 to 2.52), p=0.278 | 1.28 (0.7 to 2.33), p=0.43 |

| Anxiety/depression | 629 (30.3%) | 394 (28.2%) | 213 (33.2%) | 22 (56.4%) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.55), p=0.023 | 1.26 (1.02 to 1.55), p=0.029 | 3.29 (1.73 to 6.26), p<0.001 | 3.11 (1.62 to 5.99), p=0.001 |

| EQ-VAS, mean (SD)* | 70.8 (18.3) | 72.1 (17.9) | 68.2 (19.0) | 61.8 (17.6) | <0.001 | −3.9 (-5.83 to −1.97), p<0.001 | −3.75 (-5.69 to −1.81), p<0.001 | −10.3 (-17.53 to −3.08), p=0.005 | −11.12 (-18.29 to −3.94), p=0.002 |

| Discharge other than home | 1092 (22.0%) | 504 (16.0%) | 530 (31.9%) | 58 (40.3%) | <0.001 | 2.46 (2.13 to 2.83), p<0.001 | 2.53 (2.18 to 2.92), p<0.001 | 3.54 (2.5 to 5.01), p<0.001 | 3.81 (2.68 to 5.42), p<0.001 |

Quality of life measures were adapted from EQ-5D. We dichotomised levels into ‘no impairment’ (level 1) and ‘impairment’ (levels 2 and 3). Frequencies of reported impairment (levels 2 and 3) were analysed.

The fully adjusted model was adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities not included in the score.

*Linear regression analyses were calculated reporting regression coefficient, 95% CI, p value.

EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analogue health scale.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates stratified by the three Hospital Frailty Risk Score groups.

We also investigated the discriminative performance of the score and found only moderate results for mortality (AUC 0.66) (table 3).

Table 3.

Discriminative performance of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score regarding clinical and functional outcomes

| Outcome | AUC (95% CI) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| All-cause 30-day mortality | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.68) |

| Long hospital stay (>10 days) | 0.72 (0.70 to 0.74) |

| 30-day readmission | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) |

| Functional impairment | |

| Barthel Index <95 points, n (%) | 0.69 (0.67 to 0.71) |

| Quality of life, n (%) | |

| Impairment of mobility | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.74) |

| Impairment of self-care | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.73) |

| Impairment of usual activities | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.68) |

| Pain/discomfort | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) |

| Anxiety/depression | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.58) |

| Discharge other than home, n (%) | 0.64 (0.63 to 0.66) |

Quality of life measures were adapted from EQ-5D. We dichotomised levels into ‘no impairment’ (level 1) and ‘impairment’ (levels 2 and 3). Frequencies of reported impairment (levels 2 and 3) were analysed.

AUC, area under the receiver operating curve.

Associations of Frailty Risk Score with other adverse clinical outcomes

We also found significant results regarding the length of hospital stay and long hospital stay (>10 days). Compared with the low-risk group corresponding ORs for long hospital stay were 3.47 (95% CI 2.99 to 4.02, p<0.001) for the intermediate-risk group and 9.21 (95% CI 6.51 to 13.01, p<0.001) for the high-risk group. Again, results remained robust after adjustment for the confounders mentioned.

Regarding hospital readmission within 30 days, we did only find a significant association for the high-risk group compared with the low-risk group in the fully adjusted model (fully adjusted OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.59, p=0.022) (table 2).

Associations with functional impairment, quality of life and location after discharge

Regarding functional status, we found significantly higher proportions of impairment (Barthel Index <95 points) in higher frailty risk groups with corresponding ORs of 2.98 (95% CI 2.48 to 3.58, p<0.001) and 22.37 (95% CI 8.04 to 62.23, p<0.001). Similar results were found for quality of life measures 30 days after admission with corresponding ORs for the high-risk group of 8.61 (95% CI 4.97 to 14.91, p<0.001) for impairment of mobility, 9.40 (95% CI 4.7 to 18.79, p<0.001) for impaired self-care, 4.16 (95% CI 2.08 to 8.31, p<0.001) for impairment of usual activities and 3.29 (95% CI 1.73 to 6.26, p<0.001) for suffering from anxiety or depression.

Compared with patients in the low-risk group, patients in the high-risk group who resided at home at the time of admission had a 3.5-fold increased risk of not being able to be discharged back home (OR 3.54 (95% CI 2.5 to 5.01, p<0.001) (table 2).

Additional results of regression analyses of all models with stepwise adjustment for confounders are shown in the online supplementary material tables A1 and A2.

bmjopen-2018-026923supp001.pdf (112.9KB, pdf)

Subgroup analyses and cut-offs

Analyses of subgroups showed similar associations of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score with 30-day mortality, long hospital stay and hospital readmission among different age groups and stratified by gender with no evidence for effect modification (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Associations of elevated hospital frailty risk with adverse clinical outcomes in subgroups stratified by age and gender.

ROC analyses of modified cut-offs of the risk score did not show significant differences in AUCs for the outcome 30-day mortality compared with the initial cut-offs (online supplementary material table A3).

Discussion

Within this independent validation study including medical inpatients ≥ 75 years of age in a Swiss tertiary care setting, we found significant associations between the Hospital Frailty Risk Scores and several adverse clinical outcomes, specifically all-cause 30-day mortality, hospital length of stay and long hospital stay (>10 days). Moreover, we found significant associations of the intermediate-risk and high-risk groups with functional impairment, measured by the Barthel Index and reduced quality of life, as assessed by the EQ-5D. Last, we found patients of the higher risk group who were admitted from home significantly less likely to return back home at the time of discharge.

Compared with the three cohorts of the original publication (one development cohort and two validation cohorts) by Gilbert et al, 10 a similar proportion of patients were classified in the intermediate-risk group (33.5% vs 20.3% to 37.6%) but a smaller proportion of patients were classified in the high-risk group (2.9% vs 9.0% to 20.0%). This might be due to variation in ICD-10 coding and different healthcare systems and patient populations studied. Regarding the tertiary nature of the setting, it can be expected that some older people with severe frailty might have been managed in other secondary care settings or geriatric clinics. However, compared with the results of Gilbert et al, we found even stronger associations of the high frailty risk group compared with the low-risk group with regard to 30-day mortality (adjusted OR 4.83, 95% CI 3.17 to 7.37, p<0.001 vs adjusted OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.68 to 1.75), and long hospital stay (adjusted OR 9.75, 95% CI 6.83 to 13.92, p<0.001 vs adjusted OR 6.03, 95% CI 5.92 to 6.10). Besides, results remained robust when adjusting for NEWS, a structured early warning score that comprises physiological parameters that might be an important modifier of outcomes.

Regarding the discriminative performance of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, we found similar results as Gilbert et al with regard to 30-day mortality (AUC 0.66 vs 0.60), long hospital stay (AUC 0.72 vs 0.68) and hospital readmission within 30 days (AUC 0.54 vs 0.56). Overall, these results show significant associations of the Hospital Frailty Risk Score with adverse outcomes, however, with moderate discriminatory ability. Thus, future studies should aim to further refine the score to increase its sensitivity and specificity.

While we found the score to be helpful with strong prognostic abilities, in our cohort there were only a few patients in the highest risk category with thus limited sensitivity. It is thus possible that the score could be further improved by changing the risk categories for specific patient populations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to validate the Hospital Frailty Risk Score following its publication and initial validation. Moreover, the validation in a Swiss tertiary care hospital in an unselected medical cohort including emergency admissions and elective admissions is a first step in assessing whether the risk score is applicable in multinational settings.

In addition to Gilbert et al, we were able to show associations of higher hospital frailty risk scores not only with adverse clinical outcomes but also with functional impairment, quality of life and need for postacute care. Our data thus extend the prior study and provide new evidence that the score is valuable in risk stratification of patients based on ICD-10 codes.

A general strength of the score is the easy calculation using routine hospital data which provides a systematic method to screen for patients at risk for frailty without any need to apply a manual score bringing along resource intensive assessment and potential interoperator reliability issues.8 9 17 Moreover, instead of focusing only on symptoms and diagnoses that are known to be related to frailty, the score contains a wider set of ICD-10 codes focusing on codes that are actually in routine use.

However, the dependency of the ICD-10 codes from administrative databases is also a weakness of the score as they are coded only after hospital discharge and the score can only be applied early in the admission process to those with prior ICD-10 code records. In addition to that, calculating the score based on previous admissions has the potential to miss or misclassify frailty. Moreover, important components of frailty such as polypharmacy, general weakness and dependence on activities of daily living might not be adequately reflected in ICD-10 codes. Their absence may in part explain the relatively poor overlap of the score with the established frailty assessment tools Fried18 and Rockwood scales9 in the original study by Gilbert et al.10 This raises the question of whether the ‘hospital frailty risk score’ is, in fact, measuring frailty or whether it is predominantly a measure of comorbid disease and adverse outcome.

Our report has several limitations. First, this is a secondary analysis of a former prospective study. We did address this limitation by adjusting for confounders. Furthermore, as we were able to externally validate the previous findings accurately, we are confident that there is no additional bias. Second, due to the study design, there was no routine frailty assessment in our patients. As a consequence, we were not able to compare the Hospital Frailty Risk score with other frailty assessments or screening scores. Yet, there is no unique accepted gold standard in frailty screening to compare it to as there are two major paradigms of frailty (frailty phenotype vs frailty index).2 17 19 20 Using multiple clinical and functional outcomes as well as quality of life measures, we tried to address a broad variety of potential adverse outcomes associated with frailty.

Third, though we had a large sample size, only a few patients were in the high frailty risk group, which may impact CIs. Lastly, the score is dependent on documentation and coding of ICD-10. Thus, variation in coding could contribute to misclassification.

The development of a gold standard for frailty risk assessment has proven to be a challenging task.17 19 The attempt has left us with a multitude of screening tools, suited for a variety of patient populations and a large variability of application methods.6 Recent research suggests that a single universal frailty measurement method may not be the best approach. As some methods are useful for broad population screenings while others are based on clinical assessment, a two-tiered system may be the way forward.20 The Hospital Frailty Risk Score could be used as a screening tool to assess all older patients admitted to a hospital using all previously and currently documented ICD-10 codes. This could easily identify high-risk patients in need of a complete in-depth clinical assessment. As a low-cost, swift and consecutively widely used tool, the Hospital Frailty Risk Score could ensure that less patients with frailty are missed. Identifying frail patients is vital, as they may benefit from improved outcomes when they undergo geriatric assessment and receive a particular frailty-adjusted treatment approach.21

The Frailty Risk Score needs further validation in a wide variety of patient settings. Its place in the screening of geriatric patients, possibly in combination with other frailty assessment methods, as well as the practicability in clinical practice, has yet to be investigated. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether its theoretical benefits can be translated into improved patient care and patient outcome.

Conclusion

The Hospital Frailty Risk Score is an easy to use and low-cost tool using administrative hospital data to identify frail people at risk for adverse outcomes who might benefit from a standardised geriatric assessment and from a particular frailty-adjusted treatment approach. Our data further validate this score in an independent patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This multidisciplinary and interprofessional trial was only possible in close collaboration with personnel from multiple departments within the Kantonsspital Aarau, including social services (Anja Keller, Regina Schmid), nursing (Susanne Schirlo, Petra Tobias), central laboratory (Martha Kaeslin, Renate Hunziker), medical control (Juergen Froehlich, Thomas Holler, Christoph Reemts), and information technology (Roger Wohler, Kurt Amstad, Ralph Dahnke, Sabine Storost), the Clinical Trial Unit (CTU) at the University Hospital of Basel (Stefan Felder, Timo Tondelli), and all participating patients, nurses, and physicians.

Footnotes

AE and SIH contributed equally.

Contributors: PS had complete access to all study data and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. BM and PS were involved in the conceptualisation and design of the study. SH, AK, DK, BM and PS were responsible for the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data. AE, SIH and PS performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. TS, MAM and ON reviewed the draft and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. AE and SIH contributed equally to this work.

Funding: ThermoFisher provided an unrestricted research grant for the study. PS is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Professorship, PP00P3_150531/1) and the Research Council of the Kantonsspital Aarau (1410.000.044).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethikkommission Kanton Aargau.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/withthedoi:10.5061/dryad.71638rk.

References

- 1. Rechel B, Grundy E, Robine JM, et al. Ageing in the european union. Lancet 2013;381:1312–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62087-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hubbard RE, Peel NM, Samanta M, et al. Frailty status at admission to hospital predicts multiple adverse outcomes. Age Ageing 2017;46:801–6. 10.1093/ageing/afx081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:681–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;7:Cd006211 10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur J Intern Med 2016;31:3–10. 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, et al. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1537–51. 10.1111/jgs.12420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, et al. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:1229–37. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet 2018;391:1775–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kutz A, Hausfater P, Amin D, et al. The triage-proadm score for an early risk stratification of medical patients in the emergency department - development based on a multi-national, prospective, observational study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0168076 10.1371/journal.pone.0168076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schuetz P, Hausfater P, Amin D, et al. Biomarkers from distinct biological pathways improve early risk stratification in medical emergency patients: the multinational, prospective, observational TRIAGE study. Crit Care 2015;19:377 10.1186/s13054-015-1098-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schuetz P, Hausfater P, Amin D, et al. Optimizing triage and hospitalization in adult general medical emergency patients: the triage project. BMC Emerg Med 2013;13:12 10.1186/1471-227X-13-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:64–7. 10.3109/09638288809164105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. RCoP. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pritchard JM, Kennedy CC, Karampatos S, et al. Measuring frailty in clinical practice: a comparison of physical frailty assessment methods in a geriatric out-patient clinic. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:264 10.1186/s12877-017-0623-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M157. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:64 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cesari M, Gambassi G, van Kan GA, et al. The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: different instruments for different purposes. Age Ageing 2014;43:10–12. 10.1093/ageing/aft160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:Cd006211 10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026923supp001.pdf (112.9KB, pdf)