Abstract

Objectives

Injury is an important issue in public health. Spinal curvature disorders are deformities characterised by excessive curves of the spine. The prevalence of spinal curvature disorders is not low, but its relationship with injury has not been studied. The aim of this study is to investigate whether spinal curvature disorders increase the risk of injury.

Design

Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Using data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database from 2000 to 2010.

Participants and exposure

Patients with spinal curvature disorders were selected using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. A cohort without spinal curvature was randomly frequency-matched to the spinal curvature disorders cohort at a ratio of 2:1 according to age, sex and index year.

Primary outcome measures

The risk of injury was analysed using Cox’s proportional hazards regression models adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, urbanisation level and socioeconomic status.

Results

A total of 20 566 patients with spinal curvature disorders and 41 132 controls were enrolled in this study. The risk of injury was 2.209 times higher (95% CI 2.118 to 2.303) in patients with spinal curvature disorders than in the control group. The spinal curvature disorders cohort exhibited higher risk of developing injury compared with the control group, regardless of age, sex, comorbidities, urbanisation level and subgroup of spinal curvature disorders. Based on the subgroup analysis, the spinal curvature disorders cohort had higher risks of unintentional injury and injury diagnoses such as fracture, dislocation, open wound, superficial injury/contusion, crushing and injury to nerves and spinal cord compared with the control cohort.

Conclusions

Patients with spinal curvature disorders have a significantly higher risk of developing injury than patients without spinal curvature disorders. Aggressive detection and management of spinal curvature disorders may be beneficial for injury prevention.

Keywords: public health, spine, bone diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, scoliosis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first nationwide population-based cohort study to assess the associations between spinal curvature and injury.

The main strengths of this study are the large population-based dataset and the retrospective cohort design, which minimise selection bias.

This study cohort is large enough to examine each risks of injury among subgroups.

The limitation of this study is the lack of information on the severity of spinal curvature disorders, detailed patient characteristics and injury severity.

Introduction

The spine has a gentle curve when viewed from the side and a straight appearance when viewed from the back. This structure absorbs the stress from body movement and gravity. Kyphosis is a convex curvature of the spine that creates a hunchback appearance. Lordosis refers to the inward concave curving of the cervical and lumbar regions of the spine.1 2 When disorders of the spine occur, the natural curvatures of the spine are misaligned or exaggerated in certain areas.

Possible spinal curvature disorders include scoliosis, hyperkyphosis and hyperlordosis, which can be graded in severity by the Cobb angle.3 Scoliosis indicates a lateral displacement or curvature of the spine,4 which is defined by a curve in the spine with a Cobb angle of 10° or greater in adults.5 Hyperkyphosis and hyperlordosis are commonly referred to as kyphosis and lordosis by the medical community. The evaluation of these conditions is challenging due to the lack of standardised diagnostic criteria. Generally, the Cobb angle of a normal thoracic spine ranges between 20° and 50° in young people.1 6

Among community-dwelling individuals ≥60 years old, the current incidence of hyperkyphosis is between 20% and 40%.7–9 There are multiple contributing factors to spinal curvature disorders, such as vertebral fractures with low bone density,10–12 short vertebral height as in Scheuermann’s disease,13 degenerative disc disease,14 postural changes,15–18 muscle weakness,15 19–23 intervertebral ligament degeneration24 and systemic physical activity practice.25–28

Injury is an important issue in public health,29 especially among the elderly.30 Injuries can be divided into several types according to various factors, such as injury diagnosis, cause of injury or intentionality of injury according to the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan.31 The occurrence of injury influences the capacity for activity and can cause complications, economic burden and even mortality.32–35 Thus, determining the modifiable risks and strategies for the prevention or management of injury deserves more clinical attention.

The potential relationship between spinal curvature disorders and injury is not precisely known. Sinaki et al demonstrated that thoracic hyperkyphosis in the context of reduced muscle strength plays an important role in increasing body sway, gait unsteadiness and risk of falls in osteoporosis.23 De Groot et al suggest that patients with flexed posture (characterised by protrusion of the head and increased thoracic kyphosis) have impaired postural control during walking and may therefore have higher risk of falling.36 However, no study has described the sequential association between spine curvature disorders and injury. We conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study to investigate whether spinal curvature disorders increases the risk of injury.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Taiwan’s NHIRD has been built since Taiwan established a universal healthcare system in 1995. This database includes the medical records of the Taiwanese population of around 23.81 million, and the coverage reached 99.6% in 2016. In this study, data were collected from the NHIRD, and 1 000 000 people were randomly and anonymously selected from the entire population. The disease diagnosis codes in the NHIRD dossier are based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).37 This study was approved after a complete ethical review by the Institutional Review Board of National Defense Medical Center Tri-Service General Hospital and the informed consent was not necessary.

Study design and sampled participants

This study was a retrospective cohort design. Patients were selected if they were diagnosed with spinal curvature disorders with three or more outpatient visits and spinal curvature disorders inpatients from 2 January 2000, to 31 December 2010, according to the following ICD-9 codes: kyphosis (ICD-9-CM 737.0, 737.1, 737.41), lordosis (ICD-9-CM 737.2, 737.42), kyphoscoliosis and scoliosis (ICD-9-CM 737.3, 737.43), and unspecified (ICD-9-CM 737.40, 737.8, 737.9) from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) spinal curvature disorders diagnosed before 2000, (2) injury before tracing, (3) age <20 years and (4) unknown gender. The patients were divided into four groups based on the ICD codes.

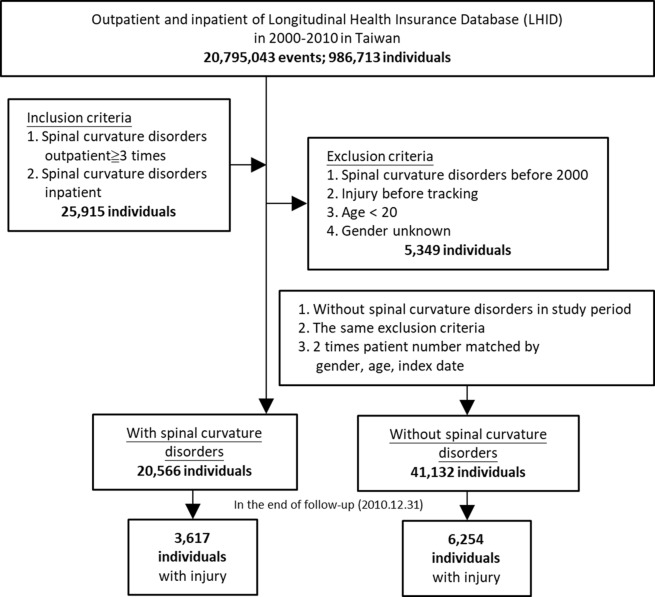

For the control cohort, we randomly selected patients without spinal curvature disorders in this period from among insured individuals. We excluded control subjects according to the same criteria. The spinal curvature disorders cohort and control cohort were frequency matched by gender, age and index rate (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of study sample selection from Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database.

Patient and public involvement

This retrospective cohort study used Taiwan NHIRD with anonymised identifications. Therefore, patients and public were not involved.

Outcome measures

All study participants were followed from the index date until the first diagnosis of injury (ICD-9-CM 800–999), withdrawal from the National Health Insurance programme or the end of 2010. Based on the definition of injury categories from prior studies,31 38 the causes of injury were classified as traffic injuries (ICD-9-CM E800–E849), poisoning (ICD-9-CM E850–E869), falls (ICD-9-CM E880–E888), burns and fires (ICD-9-CM E890–E899), drowning (ICD-9-CM E910), suffocation (ICD-9-CM E911–E915), crushing/cutting/piercing (ICD-9-CM E916–E920) and other unintentional injuries (ICD-9-CM E870–E879, E900–E909, E951–E949). The intentionality categories of injuries include unintentional (ICD-8-CM E800–R949), intentional (ICD-9-CM E950–E979, E990–E999) and unknown.

Comorbidities

Baseline comorbidities include diabetes (ICD-9-CM 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401–405), ischaemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM codes 410–414), stroke (ICD-9-CM 430–438), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM 585), liver cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM 570, 571, 572.1, 572.4, 573.1–573.3), chronic obstructive lung disease (ICD-9-CM codes 490, 491, 495 and 496) and cancer (ICD-9-CM 140–208). The population was also stratified according to the number of comorbidities (0, 1 and ≥2).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.21. χ2 and t-tests were used to evaluate the distributions of categorical and continuous variables between patients with spinal curvature disorders and the control group. The incidence rates of injury were calculated according to gender, age, number of comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine the risk of injury, which is presented as a HR with a 95% CI. The difference in injury risk between the two groups was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We enrolled 20 566 patients who had spinal curvature disorders and 41 132 subjects without spinal curvature disorders in the control group. The majority of patients were ≥65 years old (52.82% and 51.58% for spinal curvature disorders and control group, respectively). Females accounted for more than half of the subjects (64.61%) in each cohort. There is a significant difference in the number of comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium between the spinal curvature group and control group (table 1). The average period of follow-up was 5.48 years for the spinal curvature disorders cohort and 6.24 years for the control group.

Table 1.

Demographic data for patients with and without spinal curvature disorders

| Variables | Spinal curvature disorders | P value | |||

| With | Without | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 20 566 | 33.33 | 41 132 | 66.67 | |

| Gender | 0.999 | ||||

| Male | 7279 | 35.39 | 14 558 | 35.39 | |

| Female | 13 287 | 64.61 | 26 574 | 64.61 | |

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||

| 20–40 | 3107 | 15.11 | 6529 | 15.87 | |

| 41–64 | 6597 | 32.08 | 13 386 | 32.54 | |

| ≥65 | 10 862 | 52.82 | 21 217 | 51.58 | |

| No of comorbidities | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 12 469 | 60.63 | 19 513 | 47.44 | |

| 1 | 6074 | 29.53 | 12 021 | 29.23 | |

| ≥2 | 2023 | 9.84 | 9598 | 23.33 | |

| Urbanisation level | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 (The highest) | 8147 | 39.61 | 14 344 | 34.87 | |

| 2 | 7807 | 37.96 | 17 780 | 43.23 | |

| 3 | 2021 | 9.83 | 2946 | 7.16 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 2591 | 12.60 | 6062 | 14.74 | |

| Insurance premium (NT$) | <0.001 | ||||

| <18 000 | 20 193 | 98.19 | 40 541 | 98.56 | |

| 18 000–34 999 | 324 | 1.58 | 482 | 1.17 | |

| ≥35 000 | 49 | 0.24 | 109 | 0.27 | |

Table 2 shows that the incidence of injury was higher in the spinal curvature disorders cohort than that in the control cohort (10905.25 and 9059.47 incidences per 1 00 000 person-years, respectively). Compared with the control group, patients with spinal curvature disorders were associated with a significantly higher risk of injury (adjusted HR 2.209 (95% CI 2.118 to 2.303)). The spinal curvature disorders cohort exhibited a higher risk of injury compared with the control group, regardless of age, sex, comorbidities and urbanisation level. The risk of injury was also significantly higher in the spinal curvature disorders cohort than in the control cohort among patients with insurance premiums <NT$18 000 New Taiwan dollars and NT$18 000–NT$34 999. Table 3 shows the risks of injury stratified by subgroup of spinal curvature disorders (kyphosis, lordosis, kyphoscoliosis and scoliosis, and unspecified type). All subgroups of spinal curvature disorders had a significantly higher risk of injury compared with the control cohort (adjusted HR 2.777 (95% CI 2.553 to 3.021), 2.087 (95% CI 1.235 to 3.527), 2.113 (95% CI 2.021 to 2.210), 2.727 (95% CI 2.119 to 3.509), respectively).

Table 2.

Risk of injury stratified by variables

| Variables | With spinal curvature disorders | Without spinal curvature disorders | Ratio | Adjusted HR*(95% CI) | ||||

| Event | PYs | IR† (per 105 PYs) | Event | PYs | IR† (per 105 PYs) | |||

| Total | 3617 | 33167.52 | 10905.25 | 6254 | 69032.77 | 9059.47 | 1.204 | 2.209 (2.118 to 2.303)*** |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1308 | 12003.99 | 10896.38 | 2288 | 24100.91 | 9493.42 | 1.148 | 2.098 (1.958 to 2.249)*** |

| Female | 2309 | 21163.52 | 10910.28 | 3966 | 44931.86 | 8826.70 | 1.236 | 2.279 (2.162 to 2.402)*** |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 20–40 | 289 | 2945.11 | 9812.88 | 177 | 6082.11 | 2910.17 | 3.372 | 6.665 (5.512 to 8.060)*** |

| 41–64 | 885 | 7561.59 | 11703.89 | 603 | 8360.88 | 7212.16 | 1.623 | 6.154 (5.527 to 6.852)*** |

| ≥65 | 2443 | 22660.82 | 10780.72 | 5474 | 54589.78 | 10027.52 | 1.075 | 1.666 (1.587 to 1.749)*** |

| No of comorbidities | ||||||||

| 0 | 2008 | 14400.78 | 13943.69 | 2653 | 22738.69 | 11667.34 | 1.195 | 2.424 (2.284 to 2.572)*** |

| 1 | 1142 | 11337.55 | 10072.72 | 2077 | 21977.53 | 9450.56 | 1.066 | 2.203 (2.047 to 2.371)*** |

| ≥2 | 467 | 7429.19 | 6286.02 | 1524 | 24316.54 | 6267.34 | 1.003 | 1.674 (1.507 to 1.860)*** |

| Urbanisation level | ||||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 1012 | 9790.98 | 10336.04 | 1759 | 20803.62 | 8455.26 | 1.222 | 2.225 (2.056 to 2.409)*** |

| 2 | 1522 | 14516.01 | 10484.97 | 2813 | 31263.20 | 8997.80 | 1.165 | 2.145 (2.012 to 2.285)*** |

| 3 | 325 | 2422.89 | 13413.73 | 463 | 4925.73 | 9399.62 | 1.427 | 2.766 (2.390 to 3.202)*** |

| 4 (The lowest) | 758 | 6437.64 | 11774.50 | 1219 | 12040.22 | 10124.40 | 1.163 | 2.131 (1.942 to 2.339)*** |

| Insurance premium (NT$) | ||||||||

| <18 000 | 3545 | 32458.79 | 10921.54 | 6161 | 67962.43 | 9065.30 | 1.205 | 2.210 (2.118 to 2.305)*** |

| 18 000–34 999 | 68 | 643.84 | 10561.63 | 88 | 965.58 | 9113.69 | 1.159 | 2.297 (1.651 to 3.194)*** |

| ≥35 000 | 4 | 64.89 | 6164.28 | 5 | 104.76 | 4772.81 | 1.292 | 1.868 (0.430 to 8.119)‡ |

***P<0.001.

*Adjusted HR: multivariable analysis including gender, age, number of comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium.

†Indicates incidence rate per 1 00 000 PYs.

‡P=0.405.

IR, incidence rate; NT$, New Taiwan dollars; PYs, person-years.

Table 3.

Risk of injury stratified by subgroup of spinal curvature disorders

| Spinal curvature disorders | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

| Kyphosis | ||

| With | 1.579 | 2.777 (2.553 to 3.021)*** |

| Without | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Lordosis | ||

| With | 1.033 | 2.087 (1.235 to 3.527)† |

| Without | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Kyphoscoliosis and scoliosis | ||

| With | 1.146 | 2.113 (2.201 to 2.210)*** |

| Without | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Unspecified | ||

| With | 1.388 | 2.727 (2.119 to 3.509)*** |

| Without | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

***P<0.001.

ICD-9-CM code: kyphosis (ICD-9-CM 737.0, 737.1, 737.41), lordosis (ICD-9-CM 737.2, 737.42), kyphoscoliosis and scoliosis (ICD-9-CM 737.3, 737.43), and unspecified (ICD-9-CM 737.40, 737.8, 737.9).

*Adjusted HR: multivariable analysis including gender, age, comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium.

†P=0.006.

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Table 4 shows the incidence and adjusted HR of injury according to the injury diagnosis, cause of injury and intentionality of injury at the end of the follow-up period. The spinal curvature disorders cohort had a significantly higher risk of unintentionality of injury compared with the control cohort (adjusted HR 1.537 (95% CI 1.200 to 2.605)). The spinal curvature disorders cohort had significantly higher risk in injury diagnoses of fracture, dislocation, open wound, superficial injury/contusion, crushing, injury to nerve and spinal cord and other injury compared with the control cohort (adjusted HR 1.502 (95% CI 1.398 to 1.614), 1.732 (95% CI 1.172 to 2.558), 1.597 (95% CI 1.310 to 1.939), 1.414 (95% CI 1.131 to 1.761), 4.949 (95% CI 1.093 to 30.895), 2.428 (95% CI 1.310 to 4.500) and 1.387 (95% CI 1.284 to 1.499), respectively). They also had significantly higher risk of traffic injuries, falls, suffocation, crushing/cutting/piercing and other injuries compared with the control cohort (adjusted HR 1.379 (95% CI 1.191 to 1.597), 1.552 (95% CI 1.429 to 1.686), 6.442 (95% CI 2.335 to 17.776), 2.595 (95% CI 1.056 to 3.409) and 1.612 (95% CI 1.443 to 1.800), respectively). Significantly higher risk of unintentional injury was also observed in the spinal curvature disorders cohort (adjusted HR 1.537 (95% CI 1.200 to 2.605)).

Table 4.

Risk of injury stratified by injury diagnosis, cause of injury and intentionality of injury in the end of follow-up

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | |

| Injury diagnosis | ||

| Fracture | 1.193 | 1.502 (1.398 to 1.614)* |

| Dislocation | 1.859 | 1.732 (1.172 to 2.558)* |

| Sprains and strains | 1.510 | 1.341 (0.927 to 1.942) |

| Intracranial/internal injury | 0.835 | 0.996 (0.808 to 1.501) |

| Open wound | 1.244 | 1.597 (1.310 to 1.939)* |

| Injury to blood vessels | 0.297 | 0.287 (0.007 to 11.122) |

| Superficial injury/contusion | 1.321 | 1.414 (1.131 to 1.761)* |

| Crushing | 4.460 | 4.949 (1.093 to 30.895)** |

| Foreign body entering through orifice | 1.469 | 1.921 (0.970 to 3.803) |

| Burn | 2.018 | 1.453 (0.968 to 2.180) |

| Injury to nerves and spinal cord | 2.379 | 2.428 (1.310 to 4.500)* |

| Poisoning | 0.999 | 0.983 (0.809 to 1.602) |

| Others injury | 1.270 | 1.387 (1.284 to 1.499)* |

| Cause of injury | ||

| Traffic injuries | 1.370 | 1.379 (1.191 to 1.597)* |

| Poisoning | 1.150 | 1.423 (0.906 to 2.234) |

| Falls | 1.258 | 1.552 (1.429 to 1.686)* |

| Burns and fires | 2.498 | 1.567 (0.977 to 2.567) |

| Drowning | NA‡ | NA‡ |

| Suffocation | 1.972 | 6.442 (2.335 to 17.776)* |

| Crushing/cutting/ piercing |

1.788 | 2.595 (1.056 to 3.409)* |

| Other injuries | 1.401 | 1.612 (1.443 to 1.800)* |

| Intentionality of injury | ||

| Unintentional | 1.335 | 1.537 (1.200 to 2.605)* |

| Intentional | 2.330 | 2.218 (0.994 to 3.424) |

| Unknown | 1.095 | 1.076 (0.419 to 1.830) |

Some patients did not provide information about cause and intentionality of injury.

*P<0.05.

†Adjusted HR: multivariable analysis including gender, age, comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium.

‡NA, non-applicable due to only one drowning event in patients with spine curvature disorders and no drowning event in the control group.

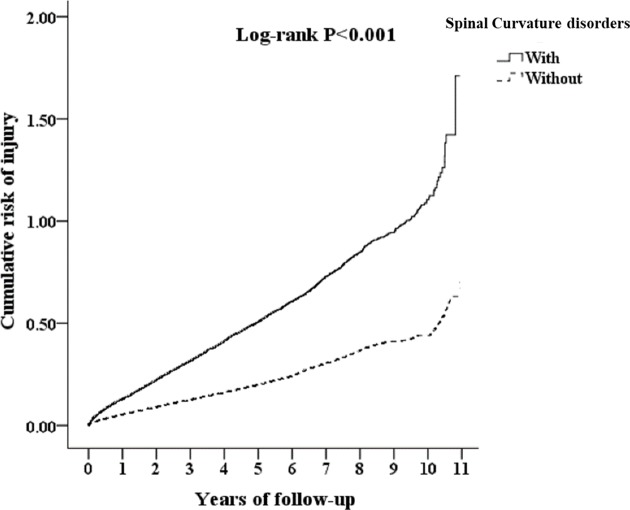

We used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to assess the cumulative incidence. The injury rates of spinal curvature disorders subjects (17.59%, in 20 566) and non-spinal curvature disorders control (15.20%, in 41 132), and in two-tailed test, while setting the significance as p<0.05, the estimated statistical power for this study is 0.999. There were significant differences in the cumulative incidence of injury among the patients with and without spinal curvature disorders from the first to the 11th follow-up year (log-rank test; p<0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for cumulative risk of injury among aged 20 over stratified by spinal curvature disorders with log-rank test.

Discussion

This is the first nationwide population-based cohort study to investigate the associations between spinal curvature disorders and injury. We found that patients with spinal curvature disorders had 2.209 times higher risk of developing injury compared with those without spinal curvature disorders. Although the spinal curvature disorders and non-spinal curvature disorders cohorts had different prevalence of comorbidities, urbanisation level and insurance premium on the index day, spinal curvature disorders remained an independent risk factor for injury in the adjusted Cox regression analysis. As shown in table 2, patients in the spinal curvature disorders cohort had a higher incidence of injury than patients in the control cohort in most of the subgroup analyses of sex, age, comorbidity, urbanisation level and socioeconomic status. This observation strengthens the finding that spinal curvature disorders independently increases the risk of injury.

For subgroup analysis of injury events, we found that patients with spinal curvature disorders had higher risk of unintentional injury and injury diagnoses such as fracture, dislocation, open wound, superficial injury/contusion, crushing and injury to nerves and spinal cord. The severity of spinal curvature disorders is defined by the measurement of the Cobb angle of curvature.3 Chest wall compliance decreases in severe cases, which leads to difficulty in breathing, increased risk of respiratory muscle fatigue,39 40 increased dead space fraction, alveolar hypoventilation with hypercapnia,41 hypoxaemia,42 ventilation–perfusion mismatch, apnoeic events with nocturnal hypoventilation and arterial oxygen desaturation,39 43 and exercise limitations.44 45 Previous studies also suggest that spinal curvature disorders is associated with reduced muscle strength, increased body sway and gait unsteadiness.23 46–48 The increased risk of unintentional injury in our study may be explained by these systemic manifestations of spinal curvature disorders.

We found that patients with spinal curvature disorders had higher risks of various injury causes, such as traffic injuries, falls, suffocation, crushing/cutting/piercing and other unintentional injuries. Among these causes, risk of suffocation (adjusted HR 6.442) was much higher than that of other injuries. Although respiratory muscle fatigue15 16 and lung function impairment were found in patients with spinal curvature,17 there are insufficient studies explaining the mechanism between spinal curvature disorders and suffocation. Further studies for analysing this correlation are warranted.

After stratifying patients with injury by age, we found that the adjusted HR of subjects aged 20 to 40 years and 41 to 64 years was much higher than that in those aged 65 years and above (adjusted HR: 6.665, 6.154 and 1.666, respectively). This contrasts with the concept that risk of injury is higher among the elderly, especially for fracture due to car crashes.49 The actual mechanisms remain unknown for this phenomenon. We found that older patients with spinal curvature disorders had more comorbidities than younger patients with these disorders (table 2). Previous studies showed that age and chronic illness are associated with disability in daily living activities.50 51 Therefore, older patients with spinal curvature disorders may present less activity. On the other hand, previous studies also demonstrated that impaired balance control52 and changes in the capacity of maintaining position53 can be found in young patients with scoliosis. It is possible that daily activities may be less limited in younger populations with spinal curvature disorders, which increases the risk of injury. Future studies on this correlation are warranted.

The treatment of spinal curvature disorders includes supportive care, bracing, pulmonary rehabilitation, non-invasive ventilation and surgery.54–58 Treatment may also improve pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and arterial blood gas, as well as eliminate obstructive apnoea.59 We found spinal curvature disorders were associated with higher risk of injury. However, whether providing assistive devices or protective gear to patients with spinal curvature disorders decreases the incidence of injury remains uncertain. Future studies focusing on the association between early detection, adequate treatment of spinal curvature disorders and the prevention of injury is warranted.

This study has some limitations. First, the severity of spinal curvature disorders, the subjective symptoms and physical examinations were not recorded which might confound the incidence rate of spinal curvature disorders. Second, there is no information on patient characteristics from the NHIRD. The data lacked information about smoking, dietary habits, alcoholism, substance use, obesity and bone mineral density, which might influence the time and incidence rate of injury occurrence. Third, the severity of injuries that would impact the patient’s daily life was not evaluated. Fourth, other bias might remain in this retrospective cohort study, despite the meticulous adjustment of the model for potential confounders.

In conclusion, our study suggests that patient with spinal curvature disorders exhibit higher risk of developing injury than patients without spinal curvature disorders, especially the risks of unintentional injury and injury diagnoses such as fracture, dislocation, open wound, superficial injury/contusion, crushing and injury to nerves and spinal cord. Aggressive detection and management of patients with spinal curvature disorders may be beneficial for injury prevention from a public health perspective.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

W-CC and C-HS contributed equally.

Contributors: Y-LK, C-HS and W-CC led the project and interpreted the data. C-HC, T-WH and C-HT conducted this study and analysed the data. S-YC, C-KP and W-EC interpreted the data. Y-LK, C-HS and W-CC wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Data were collected from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, and personal medical information about an identifiable person was not contained in this database. Because the enrolled people were randomly selected from the entire population, patient consent was not necessary. This study was approved after a complete ethical review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Defense Medical Center Tri-Service General Hospital (approval number: TSGHIRB No. 1-105-05-142).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data from this study.

References

- 1. Fon GT, Pitt MJ, Thies AC. Thoracic kyphosis: range in normal subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980;134:979–83. 10.2214/ajr.134.5.979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Voutsinas SA, MacEwen GD. Sagittal profiles of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;210:235–42. 10.1097/00003086-198609000-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. C J. Outline for the study of scoliosis. Amer Acad Orthop Surg Instructional Course Lectures 1948;5:261–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vasiliadis ES, Grivas TB, Kaspiris A. Historical overview of spinal deformities in ancient Greece. Scoliosis 2009;4:6 10.1186/1748-7161-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kane WJ. Scoliosis prevalence: a call for a statement of terms. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;126:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boseker EH, Moe JH, Winter RB, et al. Determination of “normal” thoracic kyphosis: a roentgenographic study of 121 “normal” children. J Pediatr Orthop 2000;20:796–8. 10.1097/01241398-200011000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kado DM, Huang MH, Karlamangla AS, et al. Hyperkyphotic posture predicts mortality in older community-dwelling men and women: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1662–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52458.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryan SD, Fried LP. The impact of kyphosis on daily functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1479–86. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takahashi T, Ishida K, Hirose D, et al. Trunk deformity is associated with a reduction in outdoor activities of daily living and life satisfaction in community-dwelling older people. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:273–9. 10.1007/s00198-004-1669-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ensrud KE, Black DM, Harris F, et al. Correlates of kyphosis in older women. The Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kado DM, Huang MH, Karlamangla AS, et al. Factors associated with kyphosis progression in older women: 15 years’ experience in the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:179–87. 10.1002/jbmr.1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pavlovic A, Nichols DL, Sanborn CF, et al. Relationship of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis to bone mineral density in women. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2269–73. 10.1007/s00198-013-2296-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Axenovich TI, Zaidman AM, Zorkoltseva IV, et al. Segregation analysis of Scheuermann disease in ninety families from Siberia. Am J Med Genet 2001;100:275–9. 10.1002/ajmg.1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schneider DL, von Mühlen D, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Kyphosis does not equal vertebral fractures: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Rheumatol 2004;31:747–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kado DM, Prenovost K, Crandall C. Narrative review: hyperkyphosis in older persons. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:330–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyle JJ, Milne N, Singer KP. Influence of age on cervicothoracic spinal curvature: an ex vivo radiographic survey. Clin Biomech 2002;17:361–7. 10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, et al. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:260–7. 10.2106/JBJS.D.02043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hinman MR. Comparison of thoracic kyphosis and postural stiffness in younger and older women. Spine J 2004;4:413–7. 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mika A, Unnithan VB, Mika P. Differences in thoracic kyphosis and in back muscle strength in women with bone loss due to osteoporosis. Spine 2005;30:241–6. 10.1097/01.brs.0000150521.10071.df [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brocklehurst JC, Robertson D, James-Groom P. Skeletal deformities in the elderly and their effect on postural sway. J Am Geriatr Soc 1982;30:534–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1982.tb01693.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chow RK, Harrison JE. Relationship of kyphosis to physical fitness and bone mass on post-menopausal women. Am J Phys Med 1987;66:219–27. 10.1097/00002060-198710000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sinaki M, Itoi E, Rogers JW, et al. Correlation of back extensor strength with thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis in estrogen-deficient women. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996;75:370–4. 10.1097/00002060-199609000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinaki M, Brey RH, Hughes CA, et al. Balance disorder and increased risk of falls in osteoporosis and kyphosis: significance of kyphotic posture and muscle strength. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1004–10. 10.1007/s00198-004-1791-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Birnbaum K, Siebert CH, Hinkelmann J, et al. Correction of kyphotic deformity before and after transection of the anterior longitudinal ligament–a cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2001;121:142–7. 10.1007/s004020000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Esparza-Ros F, Vaquero-Cristóbal R, Alacid F, et al. Sagittal spinal curvatures in maximal trunk flexion of young female dancers. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:595.1–595. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093494.95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. López-Miñarro PM, Alacid J, Manuel F, et al. Sagittal spinal curvatures and pelvic inclination in kayakers. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Fisica y del Deporte 2014;14:633–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaquero-Cristóbal RE, Gómez-Durán F. Thoracic and lumbar morphology in standing, sitting and maximal trunk flexion with extended knees in dancers. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte 2015;32:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 28. López-Miñarro PA, Muyor JM. Comparison of sagittal spinal curvatures and pelvic tilt in highly trained athletes from different sport disciplines. Kinesiology 2017;49:109–16. 10.26582/k.49.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj Prev 2016;22:3–18. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yeo YY, Lee SK, Lim CY, et al. A review of elderly injuries seen in a Singapore emergency department. Singapore Med J 2009;50:278–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chien WC, Chung CH, Lai CH, et al. A retrospective population-based study of injury types among elderly in Taiwan. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2014;21:3–8. 10.1080/17457300.2012.717084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National estimates of the ten leading causes of nonfatal injuries, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC. 2004. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.html (Accessed 24 May 2010).

- 33. Mackenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. The national study on costs and outcomes of trauma. J Trauma 2007;63:S54–67. Discussion S81-6 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815acb09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization. Global burden of disease. 2010. www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/ (Accessed 01 May 2010).

- 35. World Health Organization. Global status on road safety. 2015. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2015/ (Accessed 04 Apr 2016).

- 36. de Groot MH, van der Jagt-Willems HC, van Campen JP, et al. A flexed posture in elderly patients is associated with impairments in postural control during walking. Gait Posture 2014;39:767–72. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization. Manual of the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death, Ninth Revision. 1977.

- 38. Lin CL, Chung CH, Tsai YH, et al. Association between sleep disorders and injury: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Inj Prev 2016;22:342–6. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones RS, Kennedy JD, Hasham F, et al. Mechanical inefficiency of the thoracic cage in scoliosis. Thorax 1981;36:456–61. 10.1136/thx.36.6.456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Di Bari M, Chiarlone M, Matteuzzi D, et al. Thoracic kyphosis and ventilatory dysfunction in unselected older persons: an epidemiological study in Dicomano, Italy. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:909–15. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bergofsky EH, Turino GM, Fishman AP. Cardiorespiratory failure in kyphoscoliosis. Medicine 1959;38:263–318. 10.1097/00005792-195909000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Naeye RL. Kyphoscoliosis and cor pulmonale; a study of the pulmonary vascular bed. Am J Pathol 1961;38:561–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shannon DC, Riseborough EJ, Kazemi H. Ventilation perfusion relationships following correction of kyphoscoliosis. JAMA 1971;217:579–84. 10.1001/jama.1971.03190050037007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shneerson JM. The cardiorespiratory response to exercise in thoracic scoliosis. Thorax 1978;33:457–63. 10.1136/thx.33.4.457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kesten S, Garfinkel SK, Wright T, et al. Impaired exercise capacity in adults with moderate scoliosis. Chest 1991;99:663–6. 10.1378/chest.99.3.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lynn SG, Sinaki M, Westerlind KC. Balance characteristics of persons with osteoporosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:273–7. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. de Groot MH, van der Jagt-Willems HC, van Campen JP, et al. Testing postural control among various osteoporotic patient groups: a literature review. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:573–85. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Katzman WB, Vittinghoff E, Kado DM, et al. Thoracic kyphosis and rate of incident vertebral fractures: the Fracture Intervention Trial. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:899–903. 10.1007/s00198-015-3478-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brorsson B. Age and injury severity. Scand J Soc Med 1989;17:287–90. 10.1177/140349488901700406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu SC, Leu SY, Li CY. Incidence of and predictors for chronic disability in activities of daily living among older people in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:1082–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:451–8. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gauchard GC, Lascombes P, Kuhnast M, et al. Influence of different types of progressive idiopathic scoliosis on static and dynamic postural control. Spine 2001;26:1052–8. 10.1097/00007632-200105010-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Silferi V, Rougier P, Labelle H, et al. [Postural control in idiopathic scoliosis: comparison between healthy and scoliotic subjects]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2004;90:215–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Skaggs DL, Bassett GS. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: an update. Am Fam Physician 1996;53:2327–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Wright JG, et al. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1512–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1307337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Negrini S, Minozzi S, Bettany-Saltikov J, et al. Braces for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;6:CD006850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fuschillo S, De Felice A, Martucci M, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves exercise capacity in subjects with kyphoscoliosis and severe respiratory impairment. Respir Care 2015;60:96–101. 10.4187/respcare.03095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Obayashi H, Urabe Y, Yamanaka Y, et al. Effects of respiratory-muscle exercise on spinal curvature. J Sport Rehabil 2012;21:63–8. 10.1123/jsr.21.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Menon B, Aggarwal B. Influence of spinal deformity on pulmonary function, arterial blood gas values, and exercise capacity in thoracic kyphoscoliosis. Neurosciences 2007;12:293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.