Abstract

Homologous recombination (HR) is a universally conserved mechanism used to maintain genomic integrity. In eukaryotes, HR is used to repair the spontaneous double strand breaks (DSBs) that arise during mitotic growth, and the programmed DSBs that form during meiosis. The mechanisms that govern mitotic and meiotic HR share many similarities, however, there are also several key differences, which reflect the unique attributes of each process. For instance, even though many of the proteins involved in mitotic and meiotic HR are the same, DNA target specificity is not: mitotic DSBs are repaired primarily using the sister chromatid as a template, whereas meiotic DBSs are repaired primarily through targeting of the homologous chromosome. These changes in template specificity are induced by expression of meiosis-specific HR proteins, down-regulation of mitotic HR proteins, and the formation of meiosis-specific chromosomal structures. Here, we compare and contrast the biochemical properties of key recombination intermediates formed during the pre-synapsis phase of mitotic and meiotic HR. Throughout, we try to highlight unanswered questions that will shape our understanding of how homologous recombination contributes to human cancer biology and sexual reproduction.

Keywords: homologous recombination, mitotic recombination, meiotic recombination, Rad51, Dmcl, presynaptic complex

1. Introduction.

Homologous recombination (HR) contributes to the maintenance of genome integrity among ah kingdoms of life and serves as a driving force in evolution [1, 2]. The importance of HR is reflected in the fact that the protein participants, nucleoprotein structures, and general reaction mechanisms are broadly conserved throughout biology [3–7]. HR plays essential roles in DSB repair [8, 9], the rescue of stalled or collapsed replication forks [10, 11], chromosomal rearrangements [12–14], horizontal gene transfer [15], and meiosis [16–18]

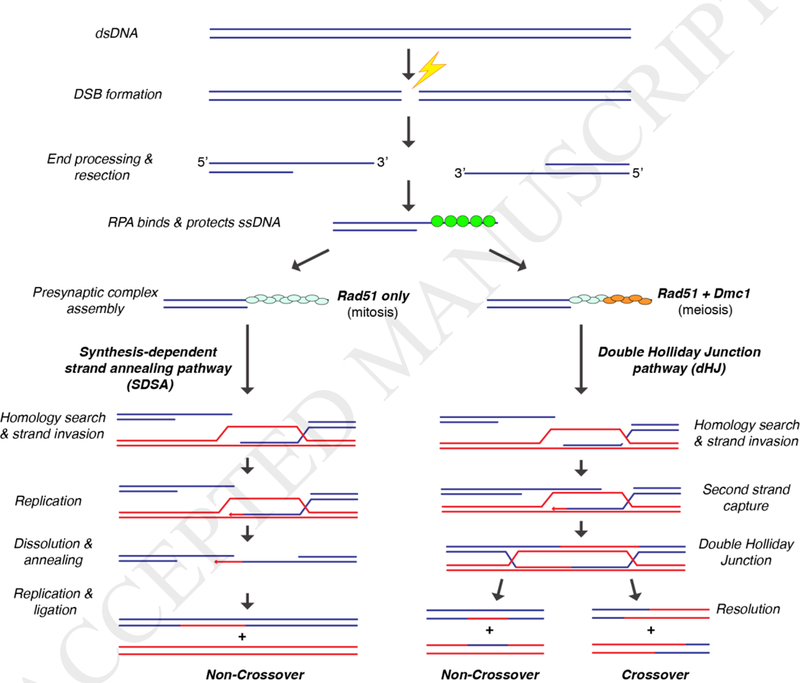

Many of the DNA transactions that take place during HR are catalyzed by the Rad51/RecA family of recombinases [19, 20]. These proteins are highly conserved ATP-dependent proteins that form extended helical filaments on the single stranded DNA (ssDNA) that is produced during DSB end processing and resection [3–5] (Fig. 1). The resulting nucleoprotein filaments are referred to as presynaptic complexes. During HR, the presynaptic complex must locate a homologous double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) that can be used as a template for guiding repair of the originally damaged DNA [3–5, 8]. The presynaptic complex then pairs the bound presynaptic ssDNA with the complementary strand from within the homologous dsDNA while displacing the non-complementary from the duplex to generate a D-loop intermediate. This strand invasion reaction is central to all processes involving HR, and the resulting intermediates can be channeled through a number of interrelated pathways to restore the continuity of the broken DNA [3–5, 8] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. General overview of homologous recombination.

General Schematic of HR pathways that occur after strand resection. Synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) is the preferred repair pathway during mitotic growth, yielding non-crossover recombination products. Meiotic recombination yields double Holliday junctions (dHJs), and resolution of these intermediates can yield either crossover or non-crossover recombination products.

Detailed understanding of presynaptic complex assembly mechanisms, regulation, and activities, are ongoing areas of research. As such, this review will focus on our current understanding of the presynaptic complex, with an emphasis on the biochemical properties of protein components of the presynaptic complexes that are, or may be, differentially regulated during mitotic and meiotic HR. The review will also focus primarily upon S. cerevisiae as a model system, and proteins from other organisms will be discussed when warranted. We will not discuss the downstream repair events, but instead we direct readers to several recent reviews that cover these topics in great detail [21, 22].

2. DSB processing and end-resection.

Initiation of mitotic DSBs is generally spontaneous, except in the specific case of mating type switching in S. cerevisiae [23, 24]. Sources of exogenous DNA damage include oxidative stress, UV irradiation, and stalled or collapsed replication forks. Stalled or collapsed replication forks are the primary cause of DSBs, and as a consequence, several HR proteins are up-regulated during Gl/S phase [25]. In mammalian cells, HR is the dominant DNA repair pathway during Gl/S phase, whereas non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) predominates during other stages of the cell cycle. In yeast, HR is initiated by 5’→3’ resection of the newly generated dsDNA through the concerted action of Mrel 1-Rad50-Xrs2 (MRX), Sgs1, Exo1, and Sae2 [26], yielding long ssDNA overhangs (Fig. 1) [27, 28]. In mammalian cells, repair is initiated through related pathways involving the Mre11-RAD50-NBS1 complex (MRN), Bloom helicase (BLM), the DNA2 helicase/nuclease, and Exonuclease 1 (EXO1) [29].

The programmed DSBs that form during meiosis are initiated by the protein Spo11, which is a universally conserved enzyme that utilizes a conserved tyrosine residue to cleave the DNA [30, 31]. In contrast to the random DSBs that form during mitotic growth, most meiotic DSBs occur within well-defined regions, a characteristic feature of which is general chromatin accessibility, although there may be other contributing factors at play as well [32]. After initiating cleavage, Spo11 remains bound to the cleaved DNA, and must be removed through the endonuclease activity of the MRX complex [33]. Once Spo11 is removed, the dsDNA ends can be processed further to yield the ssDNA overhangs necessary for presynaptic complex formation, and this resection process likely occurs though mechanisms similar to what takes place with mitotic DSBs [33, 34]. One exception to this is that Sgsl is not required for long tract resection of meiotic DSBs. Instead, long tract resection involves the ExoI enzyme, which is also capable of digesting through chromatin [35] with the help of the Swr1 chromatin remodeling enzyme [36].

The protein complex RPA (replication protein A) is loaded co-incident with DSB end resection (Fig. 1) [28, 37–39]. RPA is heterotrimeric complex that binds tightly to resected ssDNA ends during both mitotic and meiotic HR, serving to protect the ssDNA and remove secondary structure [39, 40]. The RPA-coated ssDNA serves as a platform for the assembly of the presynaptic complex, which is responsible for conducting the homology search and subsequent strand invasion steps of HR (Fig. 1). Although often depicted as separate stages, it is likely that DSB processing and presynaptic complex assembly are coupled events that take place concurrently, however, at present there are few details describing how these reactions might be coordinated with one another.

3. The presynaptic complex

At the core of the presynaptic complex are members of the Rad51/RecA family of DNA recombinase [41, 42] (Fig. 1). In eukaryotes, the mitotic recombinase is Rad51, and the importance of this protein to HR is reflected in the DNA repair deficiencies observed in S. cerevisiae rad51 mutants and the finding that homozygous null rad51 mutant mice exhibit embryonic lethality [43–45]. Rad51, like other members of the Rad51/RecA family, assembles into extended helical filaments on ssDNA, and the bound ssDNA is extended by ~50% relative to the contour length of normal B-form DNA [4, 46, 47]. As revealed by the structure of bacterial RecA, the bound DNA is organized into an unusual base triplet architecture wherein each base triplet is maintained in near B-form conformation, while the phosphodiester backbone between base triplets is held in a highly stretched conformation, giving rise to the overall extension of the DNA [48]. We have referred to this extended nucleic acid architecture as RS-DNA (Rad51/RecA-stretched DNA), to help distinguish it from other extended nucleic acid structures, such as S-DNA [49], and to highlight its unique potential as a major contributing factor to recombination mechanisms. Consistent with this idea, we and others have shown that early strand invasion intermediates appear to be stabilized in three nucleotide increments, and this feature of the reaction appears to be broadly conserved [48, 50].

Interestingly, most eukaryotes have two Rad51/RecA recombinases, Rad51, which functions during both mitotic and meiotic repair [51, 52], and Dmc1, which is only expressed during meiosis [53]. Rad51 and Dmc1 were identified over 25 years ago, yet we still have a poor understanding of why most eukaryotes require these two recombinases [54, 55]. Rad51 and Dmc1 are thought to have arisen from a gene duplication event in the early evolutionary history of eukaryotes, and these proteins still share ~45% amino sequence identity across species [56, 57]. Prevailing hypotheses to explain the need for both recombinases include (i) each recombinase is required to interact with a specific subset of mitotic- or meiotic-specific accessory factors, (ii) there are as yet other unrecognized biochemical differences between the recombinases making each uniquely suited to their roles in mitotic or meiotic HR, or (iii) both [54, 55]. As will be described below, it is clear that Rad51 and Dmc1 interact with different subsets of HR accessory factors, however, it seems unlikely that this in and of itself would provide the initial evolutionary pressure necessary to drive differential usage of the two recombinases. Other biochemical differences between these two proteins have been difficult to define. Recent studies have shown that Dmc1 can stabilize mismatched base triplets, whereas Rad51 cannot, leading us to hypothesize that differences in fidelity may account for the requirement for a meiosis-specific recombinase, perhaps allowing Dmc1 to more readily promote recombination between different parental alleles [50]. However, this hypothesis remains to be tested. We also have recently shown that Rad51 and Dmc1 are sufficiently distinct from one another that when mixed in vitro, they spontaneously segregate into separate homotypic filaments bound to the same ssDNA (see below) [58], which is in good agreement with a number of in vivo observations [52, 59]. The ability to self-segregate represents a clear biochemical distinction between Rad51 and Dmc1, and one could speculate that ability to assemble into separate filaments might have represented an early evolutionary step necessary to drive further specialization of the Rad51 and Dmc1 lineages within the Rad51/RecA family.

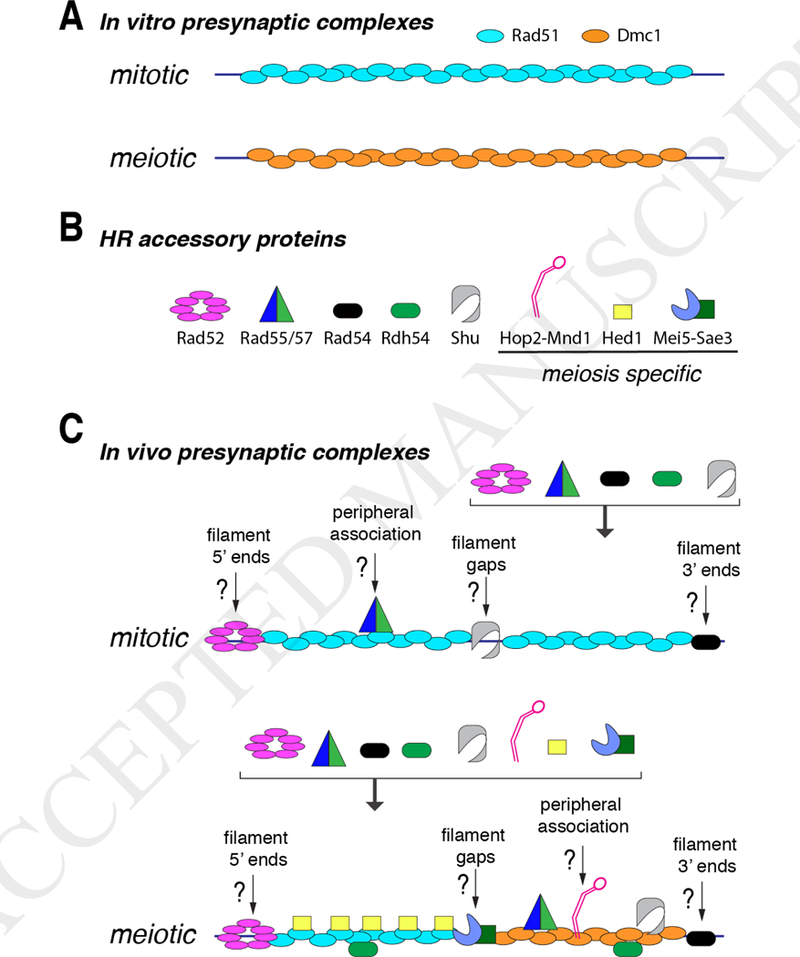

Both Rad51 and Dmc1 can, in isolation, assemble into long filaments on ssDNA that promote stand invasion reactions in vitro (Fig. 2A) [47, 52]. However, these simple recombinase filaments do not actually reflect the full complexity of HR as it occurs in living cells (Fig. 2B-C). Indeed, as will be discussed in more detail below, both recombinases require additional protein cofactors to support recombination in vivo, including proteins that promote and regulate presynaptic complex assembly, stability, and strand invasion activities (Fig. 2B) [43, 44]. Thus, a major challenge facing the field will be to move towards fully understanding the complicated protein composition, overall structural organization and detailed mechanistic features of native presynaptic complexes (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo presynaptic complexes.

(A) Schematic representations of the most commonly analyzed forms of mitotic and meiotic presynaptic complexes used for in vitro biochemical analysis. These filaments typically contain just Rad51 or just Dmc1, and in some cases will include single accessory factors such as Rad54 (not depicted). (B) Representation of several accessory factors know to associate with the presynaptic complex and affect recombination; this is not a comprehensive list, but includes many of the key factors known to play roles before and during strand invasion. (C) Hypothetical representations of mitotic and meiotic presynaptic complexes including the recombinase proteins together with the associated accessory factors. As indicated in the main text, the spatial distributions, stoichiometry, binding mechanisms, and exact biochemical roles of these accessory factors remain poorly understood.

4. Recombinase organization within the meiotic presynaptic complex

Importantly, mitotic presynaptic complexes contain Rad51, whereas meiotic presynaptic complexes contain both Rad51 and Dmc1 [51, 60]. The organization of Rad51 and Dmc1 within the meiotic presynaptic complex has been an ongoing area of research, spurned by early fluorescence microscopy studies that had suggested the existence of partially offset Rad51 and Dmc1 co-foci [61–64]. These observations led to the proposal of an asymmetric loading model in which Rad51-only filaments formed on one end of a meiotic DSB, and Dmc1-only filaments formed on the other end of the same DSB [62, 63, 65]. Several genetic and biochemical studies have also supported this asymmetric loading model, and further suggested that the Dmc1- and Rad51-containing DSB ends might be biochemically distinct from one another [66]. However, more recent super-resolution imaging studies have shown that S. cerevisiae Rad51 and Dmc1 filaments are often bound to the same ssDNA ends in vivo. This finding argued against asymmetry at meiotic DSBs and instead supports a model in which Rad51 and Dmc1 form separate filaments in a side-by-side configuration on the same ssDNA [67]. Remarkably, the meiotic presynaptic complexes were quite small, typically comprised of just ~30 recombinase monomers (sufficient to cover ~100 nucleotides of ssDNA), which was surprising given that the ssDNA overhangs were on the order of ~800 nucleotides in length [64, 68]. As indicated above we have recently shown that S. cerevisiae Rad51 and Dmc1 can assemble into homotypic filaments bound to the same ssDNA molecules in vitro (Fig. 2C), bearing a strong resemblance to expectations based on the cell biology and genetic studies [58]. An important implication of this result is that the biochemical information necessary to drive homotypic filament formation is encoded within the recombinases themselves, such that additional factors are not necessary to guide assembly of Rad51 and Dmc1 into separate filaments. We anticipate that segregation of the recombinases into homotypic filaments may provide an avenue for separation of Rad51- and Dmc1-specific protein components, yielding a highly segregated meiotic presynaptic filament with respect to the distribution of protein components (Fig. 2C). How development of such an segregated presynaptic complex might influence recombination mechanisms remains unknown. Furthermore, it remains to be seen whether Rad51 and Dmc1 from other eukaryotes can also form segregated filaments, although cell biological studies of Arabidopis thaliana Rad51 and Dmc1 suggest that they also separate into spatially distinct, side-by-side foci [69].

5. Factors that promote presynaptic complex assembly

Recombination mediator proteins act as molecular chaperones that promote the assembly or stability of the presynaptic complex [25, 43]. Recombination mediators work by allowing Rad51 and Dmc1 filaments to assemble onto ssDNA that is already bound by RPA, which itself also binds very tightly to ssDNA [25, 43] (Fig. 2C). Examples of HR mediators include Rad52 and Mei5-Sae3 in S. cerevisiae, and BRCA2 in humans [25, 70–73].

S. cerevisiae Rad52 is perhaps the most important paradigm for understanding mediator function and is the namesake of the RAD52 epistasis group genes [25, 43, 44]. Rad52 has the most severe phenotypes of the RAD52 epistasis group, and Rad52 fulfills Rad51-dependent and Rad51-independent roles during DNA damage repair [74]. Rad52 forms foci at sites of DNA damage in vivo and is essential for co-localization of Rad51 at the same sites [38, 75]. Biochemical assays have demonstrated that Rad52 promotes the loading of Rad51 onto ssDNA in the presence of RPA, thus defining Rad52 as a recombination mediator (Fig. 2C). Rad52 assembles into a heptameric ring structure and has both ssDNA and dsDNA binding activity [76]. Rad52 also contains RPA- and Rad51-binding domains, enabling each heptamer to bind several RPA and/or Rad51 molecules simultaneously [25, 77, 78]. Despite the extent of our knowledge on Rad52 genetics and biochemistry, it is still mechanistically unclear how Rad52 assists in loading and development of Rad51 filaments. One simple possibility is that Rad52 simply increases the local concentration of Rad51, allowing it to overcome any inhibitory effects of RPA, but this model remains to be validated.

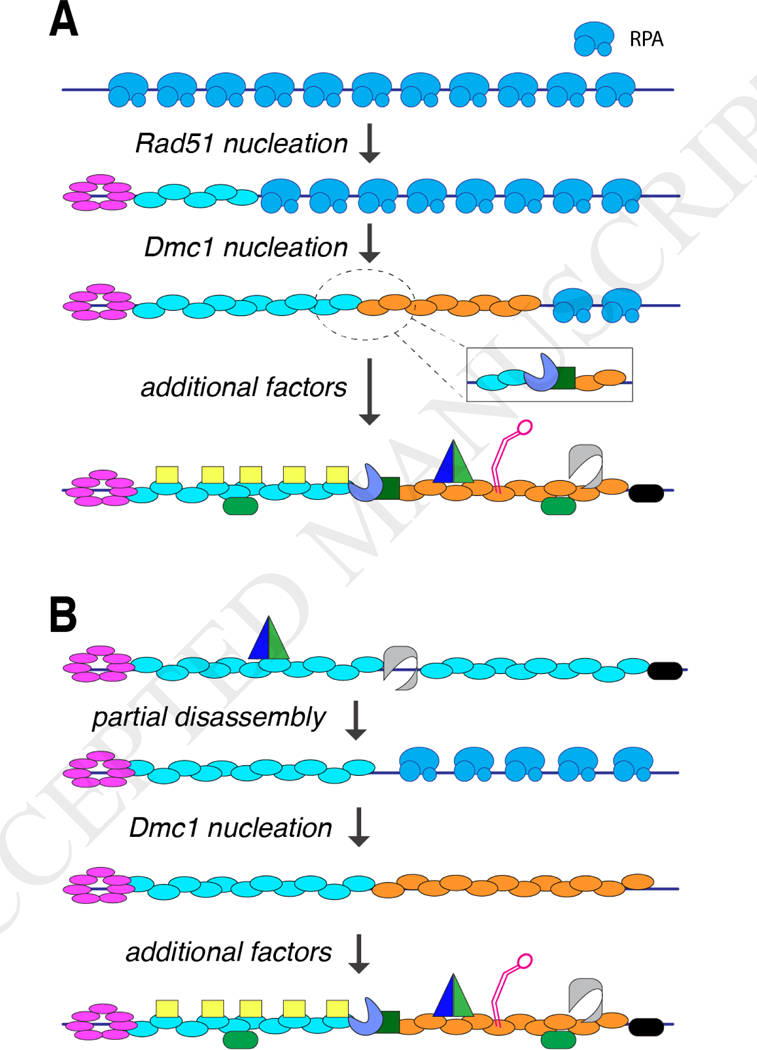

Interestingly, Rad52 does not directly promote Dmc1 loading onto RPA-ssDNA [51, 79]. Instead, Dmc1 loading is facilitated by the heterodimeric Mei5-Sae3 complex both in vivo and in vitro [80, 81], whereas Mei5-Sae3 does not stimulate the strand exchange activity of Rad51 [82]. These findings support a model in which Mei5-Sae3 functions as a Dmc1-specific mediator [80, 82]. However, it does not appear as though Mei5-Sae3 can act independently of other factors. In particular, it could be argued that Rad52 may indirectly mediate Dmc1 filament formation because Rad51 is itself required for efficient Dmc1 filament formation in vivo [83]. Therefore, there seems to exist a recruitment mechanism to help ensure that both Rad51 and Dmc1 are recruited to the same processed DSBs, as opposed a scenario in which one of the two recombinases might outcompete the other for binding (Fig. 3). Mei5-Sae3 interacts with Rad51 [84], so one possibility is that meiotic presynaptic complexes are assembled de novo beginning with Rad52-mediated assembly of Rad51 filaments, allowing for recruitment of the Mei5-Sae3 mediator complex, which in turn initiates recruitment and assembly of Dmc1 filaments (Fig. 2C & Fig. 3A) [84]. An alternative possibility, is that meiotic filaments begin as mitotic-like filaments, which are then actively remodeled to allow for association of Dmc1 and other meiosis-specific co-factors (Fig. 3C). Future work will be essential to establish how cells coordinate the assembly of Rad51 and Dmc1 at the same DSB ends to ensure that Dmc1 is properly positioned for performing strand invasion.

Figure 3. Possible mechanisms for meiotic presynaptic complex assembly.

(A) Hypothetical mechanism for de novo assembly of a meiotic presynaptic complex. In this example, assembly initiates with the Rad52-mediated nucleation of a Rad51 filament. The Rad51 filament then allows for subsequent nucleation of a Dmcl filament, either mediated through direct contacts between Rad51 and Dmcl, or perhaps though an indirect interaction involving an accessory factor such as Mei5-Sae3 (as depicted in the inset). (B) Alternative mechanism in which meiotic presynaptic complexes begin as normal mitotic filaments, followed by partial disassembly of the Rad51 filament, allowing for assembly of the Dmcl filament. Note that in both panels, the accessory factors are depicted as binding in a separate stage of the reaction, but it is likely that they binding as the Rad51 and Dmcl filaments are being assembled.

BRCA2 is an important tumor suppressor protein for understating the contribution that HR makes to human cancer biology, and it appears to act as the primary mediator of RAD51 filament assembly in human cells [70, 71, 85]. BRCA2 and its roles in DNA repair and cancer biology have been reviewed extensively elsewhere [85], so here we only briefly touch upon its biochemical properties. Human BRCA2 is an extremely large protein (3,418 amino acids), and as a consequence initial biochemical studies relied on the use of BRCA2 fragments to gain insight into its function [70, 71]. Studies with fragments of BRCA2 showed that RAD51 bound to BRCA2 via a number of conserved degenerate BRC repeats [86]. Fragments of BRCA2 were also found to bind to Dmc1, indicating a possible role for BRCA2 during meiosis [87]. Early biochemical insights into the function of full-length BRCA2 function came from studies of the Ustilago maydis BRCA2 homolog Brh2, which at 1075 amino acids in length is much smaller than its human counterpart [88]. This study revealed that Brh2 binds preferentially to dsDNA/ssDNA junctions and acts as a mediator by recruiting Rad51 to facilitate filament nucleation [88]. More recently, it has been possible to obtain recombinant human BRCA2 expressed from insect cells [70]. Studies with full-length human BRCA2 have confirmed its function as a RAD51 mediator [70], and have also shown that it acts as a mediator for DMC1 [70]. In addition to RAD51 and DMC1, human BRCA2 physically and/or genetically interacts with many other proteins that participate in HR, such as DSS1, PALB2, and RAD52 [89, 90]. How these interactions impact the regulation of HR remains an intensive topic of investigation. Interestingly, it was thought that human RAD52 played little or no role in mammalian HR, but recent studies have revealed that deletion of both BRCA2 and RAD52 is synthetically lethal [72]. This finding has reinvigorated interest in trying to define the roles that RAD52 plays in higher organisms [91].

6. Rad51 paralogs & presynaptic complex stability

Rad51 paralogs typically share ~20–30% sequence homology with the ATPase domain of Rad51, but these proteins have lost the ability to perform DNA strand exchange [92]. Four Rad51 paralogs have been biochemically characterized from S. cerevisiae, including the Rad55/57 complex [93] and the Shu complex [94–97]. Although biochemical analysis of these proteins remains limited, as discussed below, an emerging theme is that these proteins may function by increasing the stability of Rad51 filaments.

Genetic studies in S. cerevisiae suggest that Rad55/57 may function by stabilizing the Rad51 presynaptic complexes, but the mechanism by which this occur remains uncertain [98, 99]. The Rad55/57 heterodimer can be purified from yeast, but a detailed understanding of its mechanism of action remain to be discovered [93]. It is known that Rad55/57 interacts directly with Rad51 filaments, and this interaction seems to counteract the anti-recombinase activities of the Sf1 helicase Srs2 (see below) [100]. In general, one can envision at least two mechanisms to account for Rad55/57 function. For instance, one intriguing possibility is that Rad55/57 may bind to and promote extension of Rad51 filaments. Alternatively, Rad55/57 may cap the Rad51 filaments, thus restricting the ability of Rad51 to dissociate from ssDNA. Rad55/57 also interacts with Rad52 and the Shu complex, although detailed understanding of these interactions and their functional consequences remain unknown [95]. The roles that Rad55/57 may play in meiosis remain poorly understood, and it remains unknown whether Rad55/57 functions similarly with Rad51 and Dmc1. Interestingly, deletion of the RAD55 ox RAD57 genes results in weaker MMS sensitivity than other Rad52 epistasis group genes in mitotic cells [101], but causes a complete loss of homolog bias in meiotic cells [102]. This striking meiotic phenotype suggests that Rad55/57 may play different roles during mitotic and meiotic repair, and this observation also suggests that Rad55/57 might be most important for inter-homolog recombination.

S. cerevisiae Shu complex proteins (Shu1, Shu2, Psy3, and Csm2) have been identified in a number of genetic assay for DNA repair defects, and deletion of any one of the four Shu complex proteins results in sensitivity to DNA damaging agents [96]. Csm2 and Psy3 are Rad51 paralogs, which form a heterodimeric complex that can bind to DNA, but unlike Rad51 they do not require ATP for DNA-binding activity [103–105]. Shul and Shu2 are unrelated to Rad51, and do not bind to DNA in the absence of Csm2-Psy3. Biochemical data suggest that the Shu complex may act similarly to Rad52 by mediating the assembly of Rad51 onto RPA-bound ssDNA, although like Rad52, the details of this mechanism remain to be determined [95]. Interestingly, genetic assays have revealed that csm2Δ cells exhibit chromosome segregation defects during meiosis that manifest in poor spore viability [97, 106], and similar spore viability phenotypes are observed for shulΔ, shu2Δ and psy3Δ mutants [97]. These deletion mutants also exhibit a reduction in inter-homolog recombination, suggesting that like Rad55/57, the Shu complex may somehow contribute to homolog bias during meiotic recombination, although the basis for this finding remains unknown [96]. Importantly, Shu complex proteins have recently been identified in many species, including humans, suggesting that these proteins may play a broadly conserved role in eukaryotic HR [96].

Five RAD51 paralogs have been identified in humans, including RAD51B, RAD51C, Rad51D, XRCC2, and XRCC3 [73, 107], and mutations in these proteins have been linked with human breast and ovarian cancers, and other severe genetic disorders [73]. These patient phenotypes, together with many genetic studies, have clearly established the importance of the Rad51 paralogs to human genome integrity. However, biochemical analysis of the human Rad51 paralogs remains sparse, consequently we have a limited understanding of their mechanisms of action. These proteins appear to exist as two major complexes, RAD51B-RAD51C-RAD51D- XRCC2 (BCDX2) and RAD51C-XRCC3 (CX3), but it is not yet clear how these complexes function during HR, or whether these two complexes play distinct roles [73, 108]. Biochemically, the human paralogs have been implicated in a number of HR related processes including, presynaptic filament stabilization, strand opening, DNA-protein network formation [109–111] The role of the paralogs during meiosis is an active area of research, and little is known at this time.

Moving forward, in addition to understanding their mechanisms of action, another particularly relevant question that remains unanswered is with regards to how the Rad51 paralogs are organized within the context of the presynaptic complex (Fig. 2C). For instance, are they integral components of the recombinase filaments themselves, or are they only associated with the presynaptic complex through peripheral contacts with Rad51 or Dmc1? What is the relative stoichiometry of the different components, and do they undergo turnover? If they are integral components, does this mean that the recombinase filaments are discontinuous, with these accessory factors filling in the gaps? And if so, how does their presence affect the homology search and strand exchange reactions? Although we pose these questions with respect to the Rad51 paralogs, in many respects, the same questions remain to be addressed for most other recombination accessory factors that associate with the presynaptic complex.

7. Anti-recombinase regulation of the presynaptic complex

Mediators and Rad51 paralogs promote the assembly and stability of the presynaptic complex. However, the disassembly of the presynaptic filament also plays a fundamental role in the regulation of HR. In S. cerevisiae, a key factor in promoting presynaptic complex disassembly is Srs2, which is closely related to the bacterial protein UvrD [112]. Srs2 is an SF1 type helicase that exhibits robust, ssDNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis activity [100, 113]. Srs2 is a highly processive motor that can translocate rapidly (~140 bp/sec) on ssDNA while actively disrupting a number of HR intermediates, including Rad51- and RPA-ssDNA filaments, and heteroduplex joint DNA molecules [113–116]. The ability of Srs2 to disrupt Rad51-containing HR intermediates is central to its activity as an anti-recombinase [112, 116–119] One main function of Srs2 is to help channel mitotic HR intermediates through the SDSA pathway, which helps prevent crossover formation and the formation of aberrant chromosomal rearrangements [118, 120] (Fig. 1).

Central questions regarding Srs2 are what regulatory mechanisms control its actions, and what features, if any, allow it to distinguish normal recombination intermediates from potentially “aberrant” recombination intermediates. HR accessory proteins that have been implicated in Srs2 regulation include Rad55/57 [100], Rad52 [121, 122], and the Shu complex [94]. Although we do not yet have mechanistic details, given what we know of these proteins, some possible scenarios to explain their functions is that they promote more rapid reassembly of the Rad51 filaments, or they may stabilize the Rad51 filaments thus slowing their disruption. In either case, these activities may not need to completely halt the activity of Srs2, but instead result in a more subtle shift in equilibrium distribution of free Rad51 and Rad51 bound to ssDNA, which could alter the distribution of HR intermediates [100].

Srs2 expression is up-regulated upon entry into meiosis, but the potential roles of Srs2 during meiotic recombination are poorly understood [123, 124] Intriguingly, Srs2 overexpression disrupts Rad51 foci in vivo, but has no significant impact upon Dmc1 foci [125]. This observation suggests the possibility that Srs2 may be differentially regulated depending upon recombinase identity, which, if correct, might provide insight into the increased preference for crossover formation during meiotic recombination. Consistent with this notion, we have recently found that Srs2 anti-recombinase activity in vitro is completely inhibited by Dmcl (J.B.C. unpublished). The inability of Srs2 to act upon Dmc1-containing HR intermediates, raises the question of what its function(s) might be during meiosis. One possibility is that its anti- recombinase activities are confined to the Rad51 subsections of the meiotic presynaptic complexes, which may help ensure that strand invasion is driven by Dmcl. Alternatively, Srs2 activity may only act upon Rad51-mediated repair events that occur in meiosis [126, 127]. Future research will be essential to more fully understand the function and regulation of Srs2 during meiosis.

Finally, although S. cerevisiae Srs2 has emerged as an important paradigm for understanding how anti-recombinases contribute to HR, and mechanistic studies of this important HR regulatory factor may also yield insights into other helicases/anti-recombinases that participate in HR, such as Mph1 and Sgs1 [25, 124, 128]. Despite its importance in yeast, there are as yet no known Srs2 homologs in higher eukaryotes, however, there are a number of proteins that may function by similar mechanisms, including BLM, RECQ5 and FBH1 [129, 130], and future work will be essential to more fully understand details of their participation in HR.

8. Are Rad54 and Rdh54 the motors that drive the presynaptic complex?

Rad54 and Rdh54 belong to a broadly conserved class of Swi2/Snf2-related proteins that participate in nearly all aspects of mitotic and meiotic HR [25, 43, 44, 131, 132]. Indeed, their overall importance to HR has made it difficult to fully understand precisely what they are doing, and they also seem to be at least partially redundant, making it difficult to discern why both proteins are necessary. These proteins are ATP-dependent motor proteins that can translocate along dsDNA [131, 133–135]. This translocation activity is thought to help prevent the accumulation of Rad51 or Rad51 filaments on chromatin, and also is utilized when stripping Rad51, and possibly Dmcl, from strand invasion intermediates, allowing for enzymes involved in downstream stages of repair to access the DNA [136–140]. Rad54 and Rdh54 both associate with the presynaptic complex (Fig. 2C), but it remains unclear how their DNA motor activities might contribute to the function of the presynaptic complex [132, 133]. Possible functions of these proteins within the context of presynaptic complexes include, but are not limited to, stabilizing the presynaptic complex [141], facilitating nucleosome and chromatin remodeling during the homology search processes [142–145], enabling the presynaptic complex to actively translocate along dsDNA while searching for homology [133, 135], promoting strand invasion by inducing supercoiling in the homologous dsDNA [146], or catalyzing branch migration after strand invasion has taken place [147]. However, it remains unclear whether some or all of these activities reflect the roles of Rad54, and possibly Rdh54, during the early stages of HR, or whether other activities might also contribute.

Thus far, simple biochemical explanations fall short in explaining the individual contributions that Rad54 and Rdh54 might make during the early stages of HR, but genetic studies have suggested that Rad54 is more important for inter-sister repair in haploids, whereas Rdh54 plays a more important role during inter-homolog recombination in diploids [148]. Moreover, there is clear evidence for differential regulation of Rad54 and Rdh54 during meiosis. Accordingly, biochemical studies have suggested that Rad54 preferentially stimulates Rad51- mediated strand invasion, whereas Rdh54 preferentially stimulates Dmc1-mediated strand invasion [149]. The meiosis-specific protein Hed1 binds to Rad51 and prevents the association of Rad54, which in turn contributes to the down-regulation of Rad51 strand invasion activity for inter-homolog recombination during meiosis [150–154]. In contrast, Hed1 and Mek1, a protein kinase that phosphorylates both Rad54 and Hed1 [151], have no known effects on Rad54 interactions with Dmc1, thus helping to ensure that Dmc1 is the only recombinase active for inter-homolog recombination events [151–154]. Although genetic studies have suggested that Rdh54 plays a more important role for inter-homolog recombination than Rad54 during meiosis, precisely what this role is remains to be determined.

Finally, Rad54, is highly conserved among eukaryotes, for instance yeast and human Rad54 share 47% sequence identity [155], and many of the biochemical activities attributed to yeast Rad54 have also been found for the human protein. Humans have a two different Rad54 homologs, RAD54L and RAD54B, both of which participate in HR and may have overlapping roles [134, 156]. Like their yeast homologs, the human RAD54 proteins are robust ATPases [157–159], they stimulate supercoiling of dsDNA, and they also remove RAD51 from dsDNA [131]. Interestingly, yeast Rdh54 has a higher degree of similarity with the human RAD54B protein [160], although genetic and biochemical evidence seems to suggest that these proteins may act differently during meiosis. Without a greater understanding of the function of the yeast Rdh54 protein, the question of conservation will remain an open area of debate. Moreover, many questions that remain unanswered regarding the exact roles of yeast Rad54 and Rdh54 also apply to these human proteins. In particular, it will be essential to establish whether the different human RAD54 homologs have redundant functions during HR, or whether each fulfills a unique and necessary role, and if so, it will be important to fully define their mechanistic contributions.

9. How does Hop2-Mnd1 promote dsDNA capture?

Hop2-Mnd1 is an HR factor that is meiosis-specific in S. cerevisiae [161–164], and stimulates strand exchange by Dmc1 [165]. The crystal structure of Hop2-Mnd1 from Giardia lambia reveals that the complex forms a long tripartite intertwined coiled-coil domain with a winged- helix domain located at one end, resembling a fishing hook (Fig. 2C) [166]. The winged-helix domain (WHD) region binds preferentially to dsDNA, and mutations lead to a loss of function [167, 168]. Principle models for Hop2-Mnd1 function include stabilization of the presynaptic filament, recruitment of dsDNA to the presynaptic complex, or perhaps both [161]. An alternative model, based on the ability of Hop2-Mnd1 to condense dsDNA forming aggregate complexes with Dmc1 and Rad51, proposes that Hop2-Mnd1 condenses dsDNA during the homology search [169]. This interesting model aligns itself with current ideas regarding liquid- liquid phase separation, but it still needs further experimentation to validate. Currently, it is unclear whether Hop2-Mnd1 is a stable component of the presynaptic complex, or if it only binds to facilitate recruitment of dsDNA. In addition, it remains uncertain how Hop2-Mnd1 actually associates with the presynaptic complex, and although most models depict it as wrapping around the Dmc1-ssDNA filament, there is as yet no direct support for this configuration. Addressing these issues may help discern the functional consequences of Hop2- Mnd1 interactions with presynaptic complex.

Interestingly, in higher eukaryotes Hop2-Mnd1 participates in both mitotic and meiotic recombination [168]. Hop2-Mnd1 may also play a role in the immortalization of some cancers [170]. As indicated above, S. cerevisiae Hop2-Mnd1 may facilitate dsDNA capture by Dmc1, thus serving as homology search co-factor [162, 165]. Perhaps the best piece of evidence for this model comes from studies in human cancer cell lines, which has linked the HOP2 and MND1 genes to the Rad51-dependent process of Alternative Telomere Lengthening (ALT). ALT provides cancer cells with a means to prevent telomere shortening in the absence of telomerase, and accounts for telomere length maintenance in ~15% of all human cancers. Although many questions remain regarding ALT mechanisms, recent work has revealed extensive mobility of ALT presynaptic complexes in vivo, and this mobility is dependent upon RAD51, HOP2, and MND1 [170]. It remains uncertain how HOP2-MND1 contributes to these reactions, but an obvious inference is that HOP2-MND1 forms bridging contacts between the RAD51-ssDNA presynaptic complex and the homologous dsDNA. Exactly how this takes place, and what other protein participants might be necessary, remains to be established. However, establishing a better mechanistic understanding how S. cerevisiae Hop2-Mnd1 functions during yeast meiosis may also help yield insights into how HOP2-MND1 contributes to ALT during immortalization of human cancer cells, and what roles HOP2-MND1 fulfill during human development.

10. Summary

In this review we have focused on our current understanding of the biochemical properties of the eukaryotic presynaptic complex, with an emphasis on describing how the composition, properties, and regulation of this key HR intermediate vary during mitosis and meiosis. Our present knowledge of these differences remains somewhat limited, in particular with respect to differences in structural organization and regulation, highlighting the need for future studies. Key advances in the field will necessitate more complex biochemical reconstitutions to better mimic the native structure and properties of the presynaptic complexes, and this will also allow for advances in our understanding of the structural organization of the higher-order nucleoprotein complexes that participate in HR. From a broader perspective, the examples cited here also illustrate mechanistic themes that are common throughout biological processes involving the use of large macromolecular complexes to regulate nucleic acid metabolism. For instance, developmentally controlled variations in protein composition, incorporation of regulatory components that can yield alternative reaction outcomes, and the utilization of ATP hydrolysis- driven mechanical forces to physically disrupt or remodel nucleoprotein complexes. Thus, advances in our understanding of the nucleoprotein complexes that participate in HR may yield broad insights into more general aspects of protein-nucleic acid interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chaoyou Xue and Upasana Roy for comments on the manuscript. This work was support by National Institutes of Health grants to E.C.G. (R35GM118026 and P01CA092584). J.B.C. is the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research Fellow for the Damon-Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG 2310–17).

List of abbreviations:

- HR

homologous recombination

- DSB

DNA double strand break

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

- ssDNA

single stranded DNA

- SDSA

synthesis-dependent strand annealing

- dHJ

double Holliday junction

- NHEJ

non-homologous end joining

- MRX

Mre11- Rad50-Xrs2

- EXO1

Exonuclease 1

- RPA

replication protein A

- WHD

winged-helix domain

- ALT

alternative telomere lengthening

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The Authors declare they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Coop G, Przeworski M, An evolutionary view of human recombination, Nat Rev Genet, 8 (2007) 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ortiz-Barrientos D, Engelstadter J, Rieseberg LH, Recombination rate evolution and the origin of species, Trends Ecol Evol, 31 (2016) 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bianco PR, Tracy RB, Kowalczykowski SC, DNA strand exchange proteins: a biochemical and physical comparison, Front Biosci, 3 (1998) D570–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kowalczykowski SC, An overview of the molecular mechanisms of recombinational DNA repair, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 7 (2015) a016410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Morrical SW, DNA-pairing and annealing processes in homologous recombination and homology-directed repair, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 7 (2015) a016444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cromie GA, Connelly JC, Leach DR, Recombination at double-strand breaks and DNA ends: conserved mechanisms from phage to humans, Mol Cell, 8 (2001) 1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Prentiss M, Prevost C, Danilowicz C, Structure/function relationships in RecA protein- mediated homology recognition and strand exchange, Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 50 (2015) 453–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Paques F, Haber JE, Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 63 (1999) 349–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Symington LS, Rothstein R, Lisby M, Mechanisms and regulation of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics, 198 (2014) 795–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cox MM, Goodman MF, Kreuzer KN, Sherratt DJ, Sandler SJ, Marians KJ, The importance of repairing stalled replication forks, Nature, 404 (2000) 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Flores-Rozas H, Kolodner RD, Links between replication, recombination and genome instability in eukaryotes, Trends Biochem Sci, 25 (2000) 196–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kolodner RD, Putnam CD, Myung K, Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Science, 297 (2002) 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Maikova A, Haber JE, Mutations arising during repair of chromosome breaks, Annu Rev Genet, 46 (2012) 455–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mehta A, Haber JE, Sources of DNA double-strand breaks and models of recombinational DNA repair, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 6 (2014) a016428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Soucy SM, Huang J, Gogarten JP, Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life, Nat Rev Genet, 16 (2015) 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Baudat F, Imai Y, de Massy B, Meiotic recombination in mammals: localization and regulation, Nat Rev Genet, 14 (2013) 794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Barchi M, Cohen P, Keeney S, Special issue on “recent advances in meiotic chromosome structure, recombination and segregation”, Chromosoma, 125 (2016) 173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hunter N, Meiotic recombination: the essence of heredity, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7(2015)a016618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cox MM, Motoring along with the bacterial RecA protein, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 8 (2007) 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shinohara A, Ogawa H, Ogawa T, Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein, Cell, 69 (1992) 457–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kohl KP, Sekelsky J, Meiotic and mitotic recombination in meiosis, Genetics, 194 (2013) 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Matos J, West SC, Holliday junction resolution: regulation in space and time, DNA Repair, 19 (2014) 176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Haber JE, Mating-type gene switching in Saccharomyces cerevisaie Annu Rev Genet, 32 (1998) 561–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Haber JE, Mating-type genes and MAT switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics, 191 (2012)33–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sung P, Klein H, Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 7 (2006) 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Symington LS, End resection at double-strand breaks: mechanism and regulation, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 6 (2014) a016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chang HHY, Pannunzio NR, Adachi N, Lieber MR, Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair, Nat Rev Cell Biol, 18 (2017) 495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Symington LS, Mechanism and regulation of DNA end resection in eukaryotes, Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 51 (2016) 195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nimonkar AV, Genschel J, Kinoshita E, Polaczek P, Campbell JL, Wyman C, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC, BLM-DNA2-RPA-MRN and EXO1-BLM-RPA-MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair, Genes Dev, 25 (2011)350–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Keeney S, Giroux CN, Kleckner N, Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family, Cell, 88 (1997) 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Diaz RL, Alcid AD, Berger JM, Keeney S, Identification of residues in yeast Spollp critical for meiotic DNA double-strand break formation, Mol Biol Cell, 22 (2002) 1106–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pan J, Sasaki M, Kniewel R, Murakami H, Blitzblau HG, Tischfield SE, Zhu X, Neale MJ, Jasin M, Socci ND, Hochwagen A, Keeney S, A hierarchical combination of factors shapes the genome-wide topography of yeast meiotic recombination initiation, Cell, 144 (2011) 719–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Neale MJ, Pan J, Keeney S, Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked double-strand breaks, Nature, 436 (2005) 1053–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Keeney S, Spo11 and the formation of DNA double-strand breaks in meiosis, Genome Dyn Stab, 2 (2008) 81–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mimitou EP, Yamada S, Keeney S, A global view of meiotic double-strand break end resection, Science, 355 (2017) 40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Adkins NL, Niu H, Sung P, Peterson CL, Nucleosome dynamics regulate DNA processing, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 20 (2013) 836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cejka P, Cannavo E, Polaczek P, Masuda-Sasa T, Pokharel S, Campbell JL, Kowalczykowski SC, DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgsl-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmil and Mrel 1-Rad50-Xrs2, Nature, 467 (2010) 112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lisby M, Barlow JH, Burgess RC, Rothstein R, Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins, Cell, 118 (2004) 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chen H, Lisby M, Symington LS, RPA coordinates DNA end resection and prevents formation of DNA hairpins, Mol Cell, 50 (2013) 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chen R, Wold MS, Replication protein A: single-stranded DNA’s first responder : dynamic DNA-interactions allow replication protein A to direct single-strand DNA intermediates into different pathways for synthesis or repair, BioEssays, 36 (2014) 1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sung P, Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast RAD51 protein, Science, 265 (1994) 1241–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Shibata T, DasGupta C, Cunningham RP, Radding CM, Purified Escherichia coli recA protein catalyzes homologous pairing of superhelical DNA and single-stranded fragments, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 76 (1979) 1638–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Filippo JS, Sung P, Klein H, Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination, Annu Rev Biochem, 77 (2008) 229–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Heyer W-D, Ehmsen KT, Liu J, Regulation of homologous recombination in eukaryotes, Annu Rev Genet, 44 (2010) 113–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tsuzuki T, Fujii Y, Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Nakao K, Sekiguchi M, Matsushiro A, Yoshimura Y, MoritaT, Targeted disruption of the Rad51 gene leads to lethality in embryonic mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 93 (1996) 6236–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Egelman EH, Stasiak A, Structure of helical RecA-DNA complexes: Complexes formed in the presence of ATP-gamma-S or ATP, J Mol Biol, 191 (1986) 677–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lee MH, Chang Y-C, Hong EL, Grubb J, Chang C-S, Bishop DK, Wang T-F, Calcium ion promotes yeast Dmc1 activity via formation of long and fine helical filaments with single-stranded DNA, J Biol Chem, 280 (2005) 40980–40984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen Z, Yang H, Pavletich NP, Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures, Nature, 453 (2008) 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].King GA, Gross P, Bockelmann U, Modesti M, Wuite GJL, Peterman EJG, Revealing the competition between peeled ssDNA, melting bubbles, and S-DNA during DNA overstretching using fluorescence microscopy, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110 (2013) 3859–3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee JY, Terakawa T, Qi Z, Steinfeld JB, Redding S, Kwon Y, Gaines WA, Zhao W, Sung P, Greene EC, Base triplet stepping by the Rad51/RecA family of recombinases, Science 349 (2015)977–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bishop DK, RecA homologs Dmcl and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis, Cell, 79 (1994) 1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cloud V, Chan Y-L, Grubb J, Budke B, Bishop DK, Dmcl catalyzes interhomolog joint molecule formation in meiosis with Rad51 and Mei5-Sae3 as accessory factors, Science 337 (2012) 1222–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bishop DK, Park D, Xu L, Kleckner N, DMC1: A meiosis-specific yeast homolog of E. coli recA required for recombination, synaptonemal complex formation, and cell cycle progression, Cell, 69 (1992) 439–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Brown MS, Bishop DK, DNA strand exchange and RecA homologs in meiosis, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 7 (2015) a016659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Neale MJ, Keeney S, Clarifying the mechanics of DNA strand exchange in meiotic recombination, Nature, 442 (2006) 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chintapalli SV, Bhardwaj G, Babu J, Hadjiyianni L, Hong Y, Todd GK, Boosalis CA, Zhang Z, Zhou X, Ma H, Anishkin A, van Rossum DB, Patterson RL, Reevaluation of the evolutionary events within recA/RAD51 phylogeny, BMC Genomics, 14 (2013) 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lin Z, Kong H, Nei M, Ma H, Origins and evolution of the recA/RAD51 gene family: evidence for ancient gene duplication and endosymbiotic gene transfer, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103 (2006) 10328–10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Crickard JB, Kaniecki K, Kwon Y, Sung P, Greene EC, Spontaneous self-segregation of Rad51 and Dmcl DNA recombinases within mixed recombinase filaments, J Biol Chem, 293 (2018)4191–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Brown MS, Grubb J, Zhang A, Rust MJ, Bishop DK, Small Rad51 and Dmcl complexes often co-occupy both ends of a meiotic DNA double strand break, PLoS Genetics, 11 (2015)el005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lao JP, Cloud V, Huang C-C, Grubb J, Thacker D, Lee C-Y, Dresser ME, Hunter N, Bishop DK, Meiotic crossover control by concerted action of Rad51-Dmc1 in homolog template bias and robust homeostatic regulation, PLoS Genetics, 9 (2013) e1003978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bishop DK, RecA homologs Dmc1 and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis, Cell, 79 (1994) 1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Shinohara M, Gasior SL, Bishop DK, Shinohara A, Tid1/Rdh54 promotes colocalization of rad51 and dmc1 during meiotic recombination, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97 (2000) 10814–10819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kurzbauer MT, Uanschou C, Chen D, Schlogelhofer P, The recombinases DMC1 and RAD51 are functionally and spatially separated during meiosis in Arabidopsis, Plant Cell, 24 (2012) 2058–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Brown MS, Bishop DK, DNA strand exchange and RecA homologs in meiosis, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 7 (2014) a016659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bishop DK, Nikolski Y, Oshiro J, Chon J, Shinohara M, Chen X, High copy number suppression of the meiotic arrest caused by a dmc1 mutation: REC114 imposes an early recombination block and RAD54 promotes a DMC1-independent DSB repair pathway, Genes Cells, 4 (1999) 425–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Shinohara M, Gasior SL, Bishop DK, Shinohara A, Tid1/Rdh54 promotes colocalization of Rad51 and Dmc1 during meiotic recombination, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 97 (2000) 10814–10819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Brown MS, Grubb J, Zhang A, Rust MJ, Bishop DK, Small Rad51 and Dmc1 Complexes Often Co-occupy Both Ends of a Meiotic DNA Double Strand Break, PLoS Genetics, 11 (2016) e1005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Brown MS, Grubb J, Zhang A, Rust MJ, Bishop DK, Small Rad51 and Dmc1 Complexes Often Co-occupy Both Ends of a Meiotic DNA Double Strand Break, PLoS Genetics, 11 (2015) e1005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kurzbauer M-T, Uanschou C, Chen D, Schlogelhofer P, The recombinases DMC1 and RAD51 are functionally and spatially separated during meiosis in Arabidopsis, Plant Cell, 24 (2012) 2058–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Jensen RB, Carreira A, Kowalczykowski SC, Purified human BRCA2 stimulates RAD51-mediated recombination, Nature, 467 (2010) 678–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Liu J, Doty T, Gibson B, Heyer W-D, Human BRCA2 protein promotes RAD51 filament formation on RPA-covered single-stranded DNA, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 17 (2010) 1260–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Liu J, Heyer W-D, Who’s who in human recombination: BRCA2 and RAD52, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108 (2011) 441–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, Jasin M, Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 7 (2015) a016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bai Y, Symington LS, A Rad52 homolog is required for RAD51-independent mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genes Dev, 10 (1996) 2025–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lisby M, Rothstein R, Choreography of recombination proteins during the DNA damage response, DNA Repair, 8 (2009) 1068–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kagawa W, Kurumizaka H, Ishitani R, Fukai S, Nureki O, Shibata T, Yokoyama S, Crystal structure of the homologous-pairing domain from the human Rad52 recombinase in the undecameric Form, Mol Cell, 10 (2002) 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ma CJ, Kwon Y, Sung P, Greene EC, Human RAD52 interactions with replication protein A and the RAD51 presynaptic complex, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 11702–11713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Sugiyama T, New JH, Kowalczykowski SC, DNA annealing by Rad52 protein is stimulated by specific interaction with the complex of replication protein A and single-stranded DNA, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95 (1998) 6049–6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lao JP, Oh SD, Shinohara M, Shinohara A, Hunter N, Rad52 promotes postinvasion steps of meiotic double-strand-break repair, Mol Cell, 29 (2008) 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ferrari SR, Grubb J, Bishop DK, The Mei5-Sae3 protein complex mediates Dmc1 activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J Biol Chem, 284 (2009) 11766–11770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hayase A, Takagi M, Miyazaki T, Oshiumi H, Shinohara M, Shinohara A, A protein complex containing Mei5 and Sae3 promotes the assembly of the meiosis-specific RecA homolog Dmcl, Cell, 119 (2004) 927–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Say AF, Ledford LL, Sharma D, Singh AK, Leung W-K, Sehorn HA, Tsubouchi H, Sung P, Sehorn MG, The budding yeast Mei5-Sae3 complex interacts with Rad51 and preferentially binds a DNA fork structure, DNA Repair, 10 (2011) 586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Gasior SL, Wong AK, Kora Y, Shinohara A, Bishop DK, Rad52 associates with RPA and functions with Rad55 and Rad57 to assemble meiotic recombination complexes, Genes Dev, 12 (1998) 2208–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Say AF, Ledford LL, Sharma D, Singh AK, Leung W-K, Sehorn HA, Tsubouchi H, Sung P, Sehorn MG, The budding yeast Mei5-Sae3 complex interacts with Rad51 and preferentially binds a DNA fork structure, DNA Repair, 10 (2011) 586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, Jasin M, Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2 and associated proteins, Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol, 7 (2015)a016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Chen P-L, Chen C-F, Chen Y, Xiao J, Sharp ZD, Lee W-H, The BRC repeats in BRCA2 are critical for RAD51 binding and resistance to methyl methanesulfonate treatment, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95 (1998) 5287–5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Thorslund T, Esashi F, West SC, Interactions between human BRCA2 protein and the meiosis-specific recombinase DMC1, EMBO J, 26 (2007) 2915–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Yang H, Li Q, Fan J, Holloman WK, Pavletich NP, The BRCA2 homologue Brh2 nucleates RAD51 filament formation at a dsDNA-ssDNA junction, Nature, 433 (2005) 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Zhao W, Vaithiyalingam S, San Filippo J, Maranon David G., Jimenez-Sainz J, Fontenay Gerald V., Kwon Y, Leung Stanley G., Lu L, Jensen RyanB., Chazin Walter J., Wiese C, Sung P, Promotion of BRCA2-dependent homologous recombination by DSS1 via RPA targeting and DNA mimicry, Mol Cell, 59 (2015) 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Yang H, Jeffrey PD, Miller J, Kinnucan E, Sun Y, Thoma NH, Zheng N, Chen P-L, Lee W-H, Pavletich NP, BRCA2 function in DNA binding and recombination from a BRCA2- DSS1-ssDNA structure, Science, 297 (2002) 1837–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Feng Z, Scott SP, Bussen W, Sharma GG, Guo G, Pandita TK, Powell SN, Rad52 inactivation is synthetically lethal with BRCA2 deficiency, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108 (2011)686–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Thacker J, A surfeit of RAD51-like genes?, Trends Genet, 15 (1999) 166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Sung P, Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase, Genes Dev, 11 (1997) 1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Bernstein KA, Reid RJD, Sunjevaric I, Demuth K, Burgess RC, Rothstein R, The Shu complex, which contains Rad51 paralogues, promotes DNA repair through inhibition of the Srs2 anti-recombinase, Mol Biol Cell, 22 (2011) 1599–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Gaines WA, Godin SK, Kabbinavar FF, Rao T, VanDemark AP, Sung P, Bernstein KA, Promotion of presynaptic filament assembly by the ensemble of S. cerevisiae Rad51 paralogues with Rad52, Nature Commun, 6 (2015) 7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Martino J, Bernstein KA, The Shu complex is a conserved regulator of homologous recombination, FEMS Yeast Res, 16 (2016) fow073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sasanuma H, Tawaramoto MS, Lao JP, Hosaka H, Sanda E, Suzuki M, Yamashita E, Hunter N, Shinohara M, Nakagawa A, Shinohara A, A new protein complex promoting the assembly of Rad51 filaments, Nature Commun, 4 (2013) 1676–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Malik PS, Symington LS, Rad51 gain-of-function mutants that exhibit high affinity DNA binding cause DNA damage sensitivity in the absence of Srs2, Nucleic Acids Res, 36 (2008) 6504–6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Fung CW, Mozlin AM, Symington LS, Suppression of the double-strand-break-repair defect of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae rad57 mutant, Genetics, 181 (2009) 1195–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Liu J, Renault L, Veaute X, Fabre F, Stahlberg H, Heyer W-D, Rad51 paralogs Rad55- Rad57 balance the anti-recombinase Srs2 in Rad51 filament formation, Nature, 479 (2011) 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].McKinney JS, Sethi S, Tripp JD, Nguyen TN, Sanderson BA, Westmoreland JW, Resnick MA, Lewis LK, A multistep genomic screen identifies new genes required for repair of DNA double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, BMC Genomics, 14 (2013) 251–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Schwacha A, Kleckner N, Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway, Cell, 90 (1997) 1123–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Godin S, Wier A, Kabbinavar F, Bratton-Palmer DS, Ghodke H, Van Houten B, VanDemark AP, Bernstein KA, The Shu complex interacts with Rad51 through the Rad51 paralogues Rad55-Rad57 to mediate error-free recombination, Nucleic Acids Res, 41 (2013) 4525–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Tao Y, Li X, Liu Y, Ruan J, Qi S, Niu L, Teng M, Structural analysis of Shu proteins reveals a DNA binding role essential for resisting damage, J Biol Chem, 287 (2012) 20231–20239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Zhang S, Wang L, Tao Y, Bai T, Lu R, Zhang T, Chen J, Ding J, Structural basis for the functional role of the Shu complex in homologous recombination, Nucleic Acids Res, 45 (2017) 13068–13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Rabitsch KP, Toth A, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Schaffner G, Aigner E, Rupp C, Penkner AM, Moreno-Borchart AC, Primig M, Esposito RE, Klein F, Knop M, Nasmyth K, A screen for genes required for meiosis and spore formation based on whole-genome expression, Current Biol, 11 (2001) 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Suwaki N, Klare K, Tarsounas M, RAD51 paralogs: roles in DNA damage signalling, recombinational repair and tumorigenesis, Sem Cell Dev Biol, 22 (2011) 898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Masson J-Y, Tarsounas MC, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Shah R, Mcllwraith MJ, Benson FE, West SC, Identification and purification of two distinct complexes containing the five RAD51 paralogs, Genes Dev, 15 (2001) 3296–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Amunugama R, Groden J, Fishel R, The HsRAD51B-HsRAD51C stabilizes the HsRAD51 nucleoprotein filament, DNA Repair, 12 (2013) 723–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Masson J-Y, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Benson FE, West SC, Complex formation by the human RAD51C and XRCC3 recombination repair proteins, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98 (2001) 8440–8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Lio Y-C, Mazin AV, Kowalczykowski SC, Chen DJ, Complex formation by the human Rad51B and Rad51C DNA repair proteins and their activities in vitro, J Biol Chem, 278 (2003) 2469–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Niu H, Klein HL, Multifunctional roles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Srs2 protein in replication, recombination and repair, FEMS Yeast Res, 17 (2017) fowl 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Krejci L, Van Komen S, Li Y, Villemain J, Reddy MS, Klein H, Ellenberger T, Sung P, DNA helicase Srs2 disrupts the Rad51 presynaptic filament, Nature, 423 (2003) 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].De Tullio L, Kaniecki K, Kwon Y, Crickard JB, Sung P, Greene EC, Yeast Srs2 helicase promotes redistribution of single-stranded DNA-bound RPA and Rad52 in homologous recombination regulation, Cell Reports, 21 (2017) 570–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Kaniecki K, De Tullio L, Gibb B, Kwon Y, Sung P, Greene EC, Dissociation of Rad51 presynaptic complexes and heteroduplex DNA joints by tandem assemblies of Srs2, Cell Reports, 21 (2017) 3166–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Antony E, Tomko EJ, Xiao Q, Krejci L, Lohman TM, Ellenberger T, Srs2 Disassembles Rad51 filaments by a protein-protein interaction triggering ATP turnover and dissociation of Rad51 from DNA, Mol Cell, 35 (2009) 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Veaute X, Jeusset J, Soustelle C, Kowalczykowski SC, Le Cam E, Fabre F, The Srs2 helicase prevents recombination by disrupting Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments, Nature, 423 (2003)309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Liu J, Ede C, Wright WD, Gore SK, Jenkins SS, Freudenthal BD, Todd Washington M, Veaute X, Heyer W-D, Srs2 promotes synthesis-dependent strand annealing by disrupting DNA polymerase δ-extending D-loops, eLife, 6 (2017) e22195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Kaniecki K, De Tullio L, Gibb B, Kwon Y, Sung P, Greene EC, Dissociation of Rad51 Presynaptic Complexes and Heteroduplex DNA Joints by Tandem Assemblies of Srs2, Cell Reports, 21 3166–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Ira G, Maikova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE, Srs2 and Sgsl-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast, Cell, 115 (2003) 401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Burgess RC, Lisby M, Altmannova V, Krejci L, Sung P, Rothstein R, Localization of recombination proteins and Srs2 reveals anti-recombinase function in vivo, J Cell Biol, 185 (2009) 969–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Seong C, Colavito S, Kwon Y, Sung P, Krejci L, Regulation of Rad51 recombinase presynaptic filament assembly via interactions with the Rad52 mediator and the Srs2 anti- recombinase, J Biol Chem, 284 (2009) 24363–24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Palladino F, Klein HL, Analysis of mitotic and meiotic defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Srs2 DNA helicase mutants, Genetics, 132 (1992) 23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Lorenz A, Modulation of meiotic homologous recombination by DNA helicases, Yeast, 34 (2017) 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Sasanuma H, Furihata Y, Shinohara M, Shinohara A, Remodeling of the Rad51 DNA strand-exchange protein by the Srs2 helicase, Genetics, 194 (2013) 859–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Argunhan B, Leung WK, Afshar N, Terentyev Y, Subramanian VV, Murayama Y, Hochwagen A, Iwasaki H, Tsubouchi T, Tsubouchi H, Fundamental cell cycle kinases collaborate to ensure timely destruction of the synaptonemal complex during meiosis, EMBO J, 36 (2017) 2488–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Prugar E, Burnett C, Chen X, Hollingsworth NM, Coordination of Double Strand Break Repair and Meiotic Progression in Yeast by a Mek1-Ndt80 Negative Feedback Loop, Genetics, 206 (2017) 497–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Jain S, Sugawara N, Mehta A, Ryu T, Haber JE, Sgs1 and Mph1 helicases enforce the recombination execution checkpoint during DNA double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics, 203 (2016) 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Brosh RM, DNA helicases involved in DNA repair and their roles in cancer, Nat Rev Caner, 13 (2013) 542–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Bernstein KA, Gangloff S, Rothstein R, The RecQ DNA helicases in DNA repair, Annu Rev Genet, 44 (2010) 393–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Heyer W-D, Li X, Rolfsmeier M, Zhang X-P, Rad54: the Swiss Army knife of homologous recombination?, Nucleic Acids Res, 34 (2006) 4115–4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Mazin AV, Mazina OM, Bugreev DV, Rossi MJ, Rad54, the motor of homologous recombination, DNA repair, 9 (2010) 286–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC, Visualization of Rad54, a chromatin remodeling rrotein, translocating on single DNA molecules, Mol Cell, 23 (2006) 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Ceballos SJ, Heyer W-D, Functions of the Snf2/Swi2 family Rad54 motor protein in homologous recombination, BBA - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1809 (2011) 509–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Prasad TK, Robertson RB, Visnapuu M-L, Chi P, Sung P, Greene EC, A DNA translocating Snf2 molecular motor: S. cerevisiae Rdh54 displays processive translocation and can extrude DNA loops, J Mol Biol, 369 (2007) 940–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Li X, Zhang X-P, Solinger JA, Kiianitsa K, Yu X, Egelman EH, Heyer W-D, Rad51 and Rad54 ATPase activities are both required to modulate Rad51-dsDNA filament dynamics, Nucleic Acids Res, 35 (2007) 4124–4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Solinger JA, Kiianitsa K, Heyer W-D, Rad54, a Swi2/Snf2-like recombinational repair protein, disassembles Rad51:dsDNA filaments, Mol Cell, 10 (2002) 1175–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Wright William D., W.-D. Heyer, Rad54 functions as a heteroduplex DNA pump modulated by Its DNA substrates and Rad51 during D Loop formation, Mol Cell, 53 (2014) 420–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Chi P, Kwon Y, Moses DN, Seong C, Sehorn MG, Singh AK, Tsubouchi H, Greene EC, Klein HL, Sung P, Functional interactions of meiotic recombination factors Rdh54 and Dmc1, DNA Repair, 8 (2009) 279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Holzen TM, Shah PP, Olivares HA, Bishop DK, Tidl/Rdh54 promotes dissociation of Dmcl from nonrecombinogenic sites on meiotic chromatin, Genes Dev, 20 (2006) 2593–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Mazin AV, Alexeev AA, Kowalczykowski SC, A novel function of Rad54 protein: stablization of the Rad51 nucleoprotein filament J Biol Chem, 278 (2003) 14029–14036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Alexeev A, Mazin A, Kowalczykowski SC, Rad54 protein possesses chromatin-remodeling activity stimulated by the Rad51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 10 (2003) 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Zhang Z, Fan H-Y, Goldman JA, Kingston RE, Homology-driven chromatin remodeling by human RAD54, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 14 (2007) 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Wolner B, Peterson CL, ATP-dependent and ATP-independent roles for the Rad54 chromatin remodeling enzyme during recombinational repair of a DNA double strand break, J Biol Chem, 280 (2005) 10855–10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Kwon Y, Seong C, Chi P, Greene EC, Klein H, Sung P, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologous recombination factor Rdh54, J Biol Chem, 283 (2008) 10445–10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Van Komen S, Petukhova G, Sigurdsson S, Stratton S, Sung P, Superhelicity-driven homologous DNA pairing by yeast recombination factors Rad51 and Rad54, Mol Cell, 6 (2000) 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Bugreev DV, Mazina OM, Mazin AV, Rad54 protein promotes branch migration of Holliday junctions, Nature, 442 (2006) 590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Klein HL, RDH54, a RAD54 homologue in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for mitotic diploid-specific recombination and repair and for meiosis, Genetics, 147 (1997) 1533–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Nimonkar AV, Dombrowski CC, Siino JS, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Kowalczykowski SC, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dmcl and Rad51 proteins preferentially function with Tid1 and Rad54 proteins, respectively, to promote DNA strand invasion during genetic recombination, J Biol Chem, 287 (2012) 28727–28737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Liu Y, Gaines WA, Callender T, Busygina V, Oke A, Sung P, Fung JC, Hollingsworth NM, Down-regulation of Rad51 activity during meiosis in yeast prevents competition with Dmc1 for repair of double-strand breaks, PLoS Genetics, 10 (2014) el004005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Niu H, Wan L, Busygina V, Kwon Y, Allen JA, Li X, Kunz RC, Kubota K, Wang B, Sung P, Shokat KM, Gygi SP, Hollingsworth NM, Regulation of meiotic recombination via Mek1-mediated Rad54 phosphorylation, Mol Cell, 36 (2009) 393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Busygina V, Saro D, Williams G, Leung W-K, Say AF, Sehom MG, Sung P, Tsubouchi H, Novel attributes of Hed1 affect dynamics and activity of the Rad51 presynaptic filament during meiotic recombination, J Biol Chem, 287 (2012) 1566–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Busygina V, Sehorn MG, Shi IY, Tsubouchi H, Roeder GS, Sung P, Hedl regulates Rad51-mediated recombination via a novel mechanism, Genes Dev, 22 (2008) 786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Crickard JB, Kaniecki K, Kwon Y, Sung P, Lisby M, Greene EC, Regulation of Hedl and Rad54 binding during maturation of the meiosis - specific presynaptic complex, EMBO J, 37 (2018) e98728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Thoma NH, Czyzewski BK, Alexeev AA, Mazin AV, Kowalczykowski SC, Pavletich NP, Structure of the SWI2/SNF2 chromatin-remodeling domain of eukaryotic Rad54, Nat Struct Mol Biol, 12 (2005) 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Mason JM, Dusad K, Wright WD, Grubb J, Budke B, Heyer W-D, Connell PP, Weichselbaum RR, Bishop DK, RAD54 family translocases counter genotoxic effects of RAD51 in human tumor cells, Nucleic Acids Res, 43 (2015) 3180–3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Tanaka K, Kagawa W, Kinebuchi T, Kurumizaka H, Miyagawa K, Human Rad54B is a double-stranded DNA-dependent ATPase and has biochemical properties different from its structural homolog in yeast, Tidl/Rdh54, Nucleic Acids Res, 30 (2002) 1346–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Sarai N, Kagawa W, Fujikawa N, Saito K, Hikiba J, Tanaka K, Miyagawa K, Kurumizaka H, Yokoyama S, Biochemical analysis of the N-terminal domain of human RAD54B, Nucleic Acids Res, 36 (2008) 5441–5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Swagemakers SMA, Essers J, de Wit J, Hoeijmakers JHJ, Kanaar R, The human Rad54 recombinational DNA repair protein Is a double-stranded DNA-dependent ATPase, J Biol Chem, 273 (1998) 28292–28297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [160].Miyagawa K, Tsuruga T, Kinomura A, Usui K, Katsura M, Tashiro S, Mishima H, Tanaka K, A role for RAD54B in homologous recombination in human cells, EMBO J, 21 (2002) 175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [161].Pezza RJ, Voloshin ON, Vanevski F, Camerini-Otero RD, Hop2/Mndl acts on two critical steps in Dmc1-promoted homologous pairing, Genes Dev, 21 (2007) 1758–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [162].Tsubouchi H, Roeder GS, The importance of genetic recombination for fidelity of chromosome pairing in meiosis, Dev Cell, 5 (2003) 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [163].Gerton JL, DeRisi JL, Mnd1p: An evolutionarily conserved protein required for meiotic recombination, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99 (2002) 6895–6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [164].Henry JM, Camahort R, Rice DA, Florens L, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Gerton JL, Mndl/Hop2 facilitates Dmc1-dependent interhomolog crossover formation in meiosis of budding yeast, Mol Biol Cell, 26 (2006) 2913–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]