Abstract

Aim

The purpose of this study was to produce a modified Greek translation of the CS and to test this version in terms of reliability and validity.

Materials and methods

Translation of the modified Constant score testing protocol was done according to established international guidelines. Sixty-three patients with shoulder pain caused by degenerative or inflammatory disorders completed the Greek version of CS along with the Greek versions of SF-12 and Quick Dash Scores and the ASES Rating Scale and were included into the validation process. To assess test–retest reliability, 58 individuals completed the subjective part of the test again after 24–36 hours, while abstaining from all forms of treatment; internal consistency was measured using Cronbach's alpha (α); reliability was assessed with test–retest procedure and the use of Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), whereas the validity of the reference questionnaire was evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficient in relation to control questionnaires.

Results

There were no major problems during the forward–backward translation of the CS into Greek. The internal consistency was high (Cronbach's alpha 0.92) while the test–retest reliability for the overall questionnaire was also high (intra-class coefficient 0.95). Construct validity was confirmed with high values of Pearson's correlation between CS and Q-DASH (0.84), SF-12 (0.80) and ASES score (0.86) in respect.

Conclusion

A translation and cultural adaptation of CS into Greek was successfully contacted. The Greek version of the modified Constant Score can be a useful modality in the evaluation of shoulder disorders among Greek patients and doctors.

Keywords: Constant score, Outcome assessment, Questionnaire, Validity, Translation, Greek language

Patient-reported outcome measures provide the patients' perspective of the impact of a disease and its treatment on their health and quality of life. The principal types of outcome measures for musculoskeletal disorders are joint-specific, such as the Constant Score (CS), as well as disease-specific and generic outcome measures (DASH and SF-12 scores). In general, outcome measures need to have high validity and reliability, namely measuring what it is supposed to and showing a minimum of intra-observer and inter-observer error respectively. They should also be responsive by being sensitive to change.

The Constant score was devised by C. Constant with the assistance of the late Alan Murley during the years 1981–1986. The score was first presented in a university thesis in 1986 and the methodology was published in 1987.6 This functional assessment score was conceived as a system of assessing the overall value, or functional state, of a normal, a diseased or a treated shoulder. It is composed of objective and subjective sections divided into four subscales, including pain (15 points maximum), activities of daily living (20 points maximum), range of motion [ROM] (40 points maximum) and strength (25 points maximum). The higher the score the higher the quality of function (minimum 0, maximum 100). The Société Européenne pour la Chiurgie de l'Épauleet du Coude (SECEC) adopted this score in 1991 and charged its Research and Development Committee to study the score and issue guidelines. It was unanimously agreed that the score should be retained as a minimal data set for presentations and communications to the Society and to the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, respectively.4, 6 It was widely accepted that this score does not provide sufficient information for the assessment of certain conditions, particularly instability.13 However, at present, it is considered to be the most appropriate score for assessing overall shoulder function, but despite its wide adaptation by the orthopedic community, the CS has been criticized for several reasons including the inadequacy to address patient's pain using only a single pain scale, the interpretation of function mainly by the patient as there is no correlation to any certain activity and the lack of initial standardization of the method of strength measuring.14, 17, 18 Another weakness of this system is that it requires a large amount of objective data collection by the clinician, thus affecting inter-rater reliability and also appropriateness of age correction, and validity for specific purposes.1, 17, 18 To address the weaknesses of the score, Constant et al.5 published the modified CS in 2008 with specific modifications and guidelines for its use. Although this version helped clinicians to better understand the system, a standardized test protocol was not available in this report. In 2013 Ban et al.1 published a Danish translation and cultural adaptation of the modified CS and provided a standardized test protocol for both the English and Danish versions. Accordingly, in 2016 Çelik9 successfully conducted a translation and cultural adaptation of the modified CS and its standardized test protocol into Turkish, as well as an assessment of its reliability and validity.

Even though the CS is widely used in Greece to assess shoulder pathologies, translated and culturally adapted versions of the modified CS and standardized test protocols have not yet been provided. Cross-cultural adaptations may contribute to a better understanding of the measurement properties. The need for validated translations has become more essential with the growing number of multicenter and multinational studies, which provide more statistical power to randomized controlled trials. Given the prevalence and socioeconomic impact of shoulder disorders we believe that a Greek cultural adaptation and validation of the CS would be extremely beneficial for Greek-speaking surgeons and patients.

The purpose of this study was, at first, to develop a standardized, easy handled test protocol in the original language (English) according to the initial version, the recommendation guidelines published in 2008 and the recent translations in Danish and Turkish1, 5, 9 and then to translate and cross-cultural adapt this new test protocol of the CS into Greek. The whole process was completed with a reliability and validity check of the Greek CS according to international guidelines.25

Materials and methods

The whole process involved three steps: the development of an English test protocol, its translation into Greek and finally the validity check procedure of the translated Greek CS version.

A. Development of the English test protocol

In this first step of the process an English test protocol of the CS that included all sub elements of the score according to the original6 and the modified guidelines5 was created by two members of our clinic's medical staff with certified excellent knowledge of the English language and medical terminology. The recent Danish translation of the CS by Ban et al.1 provided a valuable source of support to our attempt. Each member worked separately and finally two versions of the initial English test protocol were discussed with the project coordinator [A.P.] so that a final form of the English version to be translated in Greek was established (Appendix S1a). This initial workgroup focused its efforts on creating a brief and simple questionnaire without affecting the overall quality and validity of the primary score and guidelines. Their ultimate goal was to produce a score which would fit in an A4-size page adding to the score's flexibility in terms of an easy-filling, storing-friendly form. It is known that in clinical practice larger multi-paged questionnaires are usually quite cumbersome as individual parts and may be lost or left blank by the patient.

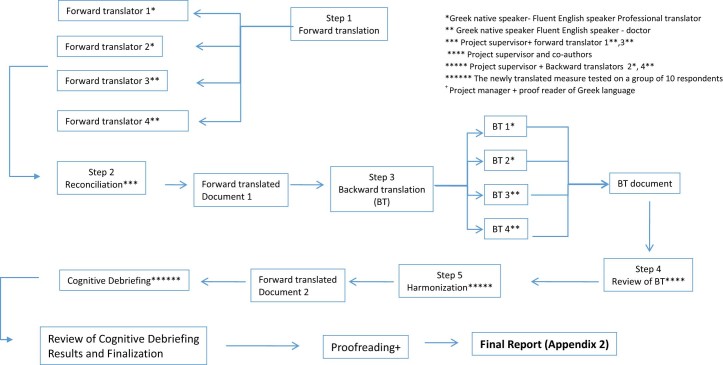

B. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation into Greek [Fig. 1]

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic scheme of the procedure followed for translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Greek version of CS.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the reference English CS into Greek was performed in 5 stages, consistent with the stages recommended by Beaton et al.2 and the principles of the ISPOR Task Force guidelines25 for translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcomes.

Four individual conversions were conducted translating the initial English score into Greek. Two were conducted by medical doctors (one resident and one Professor in Orthopedics) with certified excellent knowledge of the English language. The other two conversions were performed by officially validated, independent professional translators. All participants in this process were native Greek speakers and two of them (medical doctors) had already been involved in other similar projects in the past, translating medical questionnaires. The translations were completed independently. Results of the 4 individual conversions were gathered and evaluated by the medical doctors involved in the procedure in collaboration with one of the two independent professional translators. The final step was to assemble a Greek score through cross-editing of the 4 individual translations. During this procedure there were no significant diversions observed between the 4 individual translations or the initial English form.

Back translation procedure has been a matter of controversy between researchers. This process is considered an essential part of such projects for some10, 20, 21, 23 while others believe that more problems are generated than solved.7, 15 In an attempt to stay in accordance with the ISPOR principles,24 we decided to include this particular step in our project methodology. As mentioned before this task was undertaken by 4 individual translators who were not involved in any of the previous steps. Two of them were medical doctors in our clinic with a certified excellent knowledge of English and 2 were professional translators. All individuals were native Greek speakers and one medical doctor had former experience of such projects. Back translation check was carried out by the project supervisor [A.P.] in collaboration with one of the authors. Back translated text was compared to the text-source (Greek language), checking for any misinterpretations or mistakes. No significant inconsistencies were noted during this procedure, thus establishing equivalence in meaning for our questionnaire in relation to the source. All back-translated questionnaires were compared to the initial English score by the project's supervisor and 2 independent translators of each previous step (forward and back translation). No major deviations were noted between the two different versions of the English text and equivalence in meaning between the source-text (English) and the target-text (Greek) was established. The Translated Greek Constant Score test protocol is shown in Appendix S1b.

Cognitive pretesting of the final Greek version of CS was performed in 10 patients of our clinic to determine the acceptability and comprehensibility of the translation. The subjective part of the test was evaluated by 10 Greek patients, 6 men and 4 women with a mean age of 44.6 years (range 18–80 years), whereas the objective part was performed by 3 medical doctors of our clinics staff (2 residents and 1 consultant) who were asked at the end to make their comments and remarks. All patients had Greek as their native language and were diagnosed with some sort of shoulder disorder excluding instability or previous shoulder surgery. Medical doctors who participated in this stage of the project had not been involved in any of the previous steps and came across the translated Greek version of CS for the first time on the day of the pretesting procedure. For every single sub-element of the score's subjective part, patients were asked to answer the following questions: “do you understand the meaning of this?” and “can you describe the meaning of this in your own words?” in order to evaluate the clarity of the score's questions. These preliminary results were assessed by the project's supervisor and the necessary alterations and improvements were made leading to the formation of the final version of the score. In the final step of this procedure, the finalized text of the Greek version of Constant Score was delivered to an officially certified proficient user of Greek language for syntax and grammar check. The whole procedure of translation and cultural adaptation is illustrated in Fig. 1.

C. Validity and reliability check

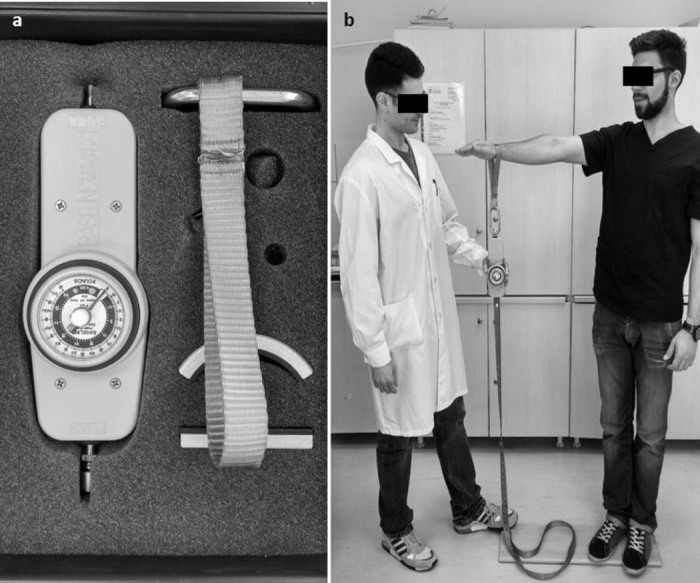

Sixty-three consecutive patients with shoulder pain were recruited. All patients were seen at the orthopedic outpatient clinic of our university hospital. Exclusion criteria were shoulder instability, age less than 18, poor knowledge of Greek language and the inability to read Greek text. Patient's sex, age, dominant hand, medical history, educational status, occupation and diagnosis were recorded (Table I). All patients gave their informed consent upon receiving complete information on the study and agreed to complete the Greek version of Constant Score and also the Greek version of SF-12, the American Shoulder and Elbow Score (ASES) (there is no official Greek translation; the test was explained by the performing doctors) and the Greek version of Quick-DASH Score as to certify the validity of the translated version of the reference test protocol. For strength measurements, included in the reference questionnaire, we used the Baseline® hydraulic push–pull dynamometer (Baseline® Hydraulic Manual Muscle Testers) (Fig. 2a). To facilitate measurements, patients stood on a wooden platform of our own design which was connected to the dynamometer through an inelastic strap, as shown in Fig. 2b. The strength score was calculated as the best out of 3 consecutive attempts, calibrating the dynamometer to zero after each measurement if necessary. To assess consistency and reliability of the procedure 58 of these patients (35 men and 23 women) with a mean age of 47.1 years (range 18–79) were re-evaluated completing the subjective part (A and B sections) of the Greek Constant Score again, 24–36 hours after the initial test, without having received any form of treatment in the meantime. All results were collected and recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2011). For statistical analysis we used version 17 of the SPSS software for Windows (Statistical Package for Social Science version 17.0). Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach's alpha8 (α), reliability was assessed with test–retest procedure and the use of Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC),19 whereas the validity of the reference questionnaire was evaluated using the Pearson's correlation coefficient16 in relation to control questionnaires.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Variable | No. (%), mean (range) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 37(58.7) |

| Female | 26(41.3) |

| Dominant side (R/L) | 57/6(90.5) |

| Age, y | 47.6(18–83) |

| Medical history | |

| Diabetes | 11(17.4) |

| Thyroid | 9(14.2) |

| Occupation | |

| Currently employed | 32(50) |

| Retired | 24(38) |

| Students | 7(12) |

| Educational status | |

| University | 25 |

| High School | 28 |

| Primary School | 10 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Adhesive capsulitis | 11(17.4) |

| Impingement syndrome | 24(38) |

| Calcifying tendinitis | 9(14.2) |

| Rotator cuff tear | 11(17.4) |

| Glenohumeral arthritis | 5(7.9) |

| Rotator cuff arthropathy | 3(4.8) |

| Acromioclavicular arthritis | 2(3) |

Figure 2.

(a) The Baseline® hydraulic push–pull dynamometer (Baseline® Hydraulic Manual Muscle Testers) that was used for strength measurements. (b) The wooden platform of our own design; the dynamometer was connected to the platform through an inelastic strap and the patient stood on the platform during the muscle strength evaluation procedure.

Results

No major inconsistencies were found regarding forward (English to Greek) and back translation procedures. As far as culturaladaptation is concerned no issues arose since the subjective part of Constant Score does not include any elements that could vary significantly among different cultures and lifestyles (daily personal hygiene, eating manners etc). Difficulties were encountered though during preliminary testing of the score. For sub-element 2 of section “A” in particular involving an unrated scale assessing pain, 6 out of 10 participants asked for further explanations and 2 of them eventually did not manage to fill this part although they had been given thorough instructions. Further clarification was also asked regarding the word “sternum” (meaning and location of the bone) mentioned in the sub-element 4 of section “B” assessing the level of comfortable use of the affected arm during daily activities. Interesting issues arose following medical doctor's remarks in relation to the objective part of Constant Score. All 3 participants asked for instructions regarding the grading of internal rotation in sub-element 4 of section “C”. Their main concern was over deciding which anatomic area was reached by the patient, as landmarks of different grading value described in the questionnaire were in a rather close proximity to each other in some cases (eg. sacroiliac joint – waist – 12th thoracic vertebrae). Such issues led to certain modifications regarding the form of the questionnaire. Specifically the unrated pain scale was replaced by a rated one graded from 0 to 15 (0 = no pain, 15 = intolerable pain). The inability to use the unrated pain scale on behalf of the majority of the patients during the cognitive pretesting procedure urged the authors to replace it. This decision led to what could be considered as the most significant modification and main deviation from the baseline recommendations on performing Constant Score. Regarding the problems with sub-element 4 in section “B” (localization of the anatomic landmark “sternum”), we responded with the addition of “breast”, as a descriptive word besides “sternum”, which we believed it was a highly recognizable term in the public. Comments and remarks expressed by the medical doctors who participated in the pilot testing procedure were listed as top priority issues. Hence we felt that the evaluation method of internal rotation should be enhanced to reassure proper and reliable scoring procedure. Therefore an illustrated appendix was added to the questionnaire providing instructions on how to perform the different range of motion tests, also expanded to include external rotation measurements. The final form of our translated Constant Score Test Protocol including all the above modifications and additions is shown in Appendix S2. The instructions for performing range of motion testing and measurement of strength are shown in Appendix S3a (English) and Appendix S3b (Greek).

Internal consistency is calculated using Cronbach's alpha (α) and is a measure based on the correlations between different items on the same test (or the same subscale on a larger test). This parameter represents the degree to which every test item proposed to assess shoulder function produces similar scores.8, 19 According to the literature a reliable measurement should involve a test sample of 30–40 patients3 and an alpha (α) value over 0.7 would show good internal consistency.11, 19 Internal consistency of our protocol was measured for both pilot testing procedures and revealed Cronbach's alpha (α) values of 0.92 and 0.93 respectively. These results demonstrate high internal consistency and are statistically acceptable.3

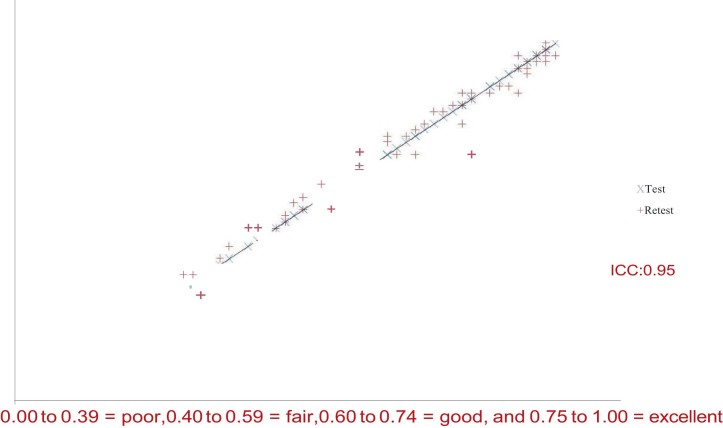

Test–retest reliability represents the degree to which subsequent test measurements, under the same circumstances, produce consistent results over time. The reproducibility was investigated by calculating the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC, 2-way random model for agreement) between the test and re-test. A test is considered reliable when it produces same results for every participant in consecutive measurements under same conditions. The Interclass Correlation Coefficient ranges between 0.00 and 1.00. Prices in the region of 0.75–1.00 show excellent internal correlation.19 Our sample consisted of 58 patients retested 24–36 hours after the initial evaluation without having received in the meantime any kind of treatment for their shoulder condition. Statistical analysis revealed an ICC value of 0.95 which demonstrates excellent test–retest reliability for our Greek version of Constant Score (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Test–retest reliability for the Greek version of Constant Score.

Construct validity examines whether a test “measures what it claims” and is evaluated in relation to other tests already validated to serve into the same purpose.8, 22 The Greek version of Constant Score was checked relatively to the Greek version of SF-12, ASES Shoulder Score (with no official Greek translation) and the Greek version of Quick-DASH Score using correlation coefficient Pearson (Pearson's r).16 The Pearson correlation assumes that the 2 variables are measured on at least interval scales and it determines the extent to which values of the 2 variables are “proportional” to each other. According to the literature a score has adequate construct validity when Pearson's r reaches rates over 0.8. Statistical analysis revealed high percentages of construct validity for our Greek version of Constant Score in relation to the 3 control scores. In fact, Pearson's r in relation to SF-12, ASES and Q-DASH was 0.80, 0.86 and 0.84 respectively.

Discussion

Our purpose to perform the first official translation and cultural adaptation of the modified Constant Score into Greek has been successfully accomplished. This conversion has been carried out in accordance with the international ISPOR25 guidelines and was followed by establishing internal consistency, reliability and construct validity according to international literature recommendations. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the modified CS were found to be acceptable. In general, we did not encounter major difficulties during the translation and cultural adaptation of the score because it did not involve too much of – what could be – confusing scientific terminology and, moreover, it did not include questions that could differ according to lifestyle options and cultural habits (personal hygiene, eating habits, etc).

The CS was originally developed as a scoring system for the evaluation of functional outcome in patients with general shoulder problems but is often criticized for relying on imprecise terminology and for lack of a standardized protocol.18 Blonna et al.3 showed significant improvement of both inter- and intra-observer reliability after using standardized CS protocols and provided such a version without however incorporating the new and modified guidelines provided by Constant et al.5 in 2008. Hirschmann et al.12 emphasized the importance of standardized torso and arm positions ensuring high reliability when performing the strength measurement of the CS. They found that the degree of shoulder abduction influenced strength values. Intra-observer reliability was most reliable at 90 degrees of abduction without stabilization of the torso. Roy et al.18 conducted a systematic review of the psychometric evidence related to CS and, regarding the content validity of the score studies, suggested that the description in the original publication was insufficient to accomplish standardization between centers and evaluators. Despite this limitation, in this review the Constant–Murley score correlated strongly (≥0.70) with shoulder-specific questionnaires, reached acceptable benchmarks (ρ > 0.80) for its reliability coefficients and was responsive (effect sizes and standardized response mean > 0.80) for detecting improvement after intervention in a variety of shoulder pathologies. Recent publications of translation and cultural adaptation of the modified CS by Ban et al.1 into Danish and Çelik9 into Turkish provided a standardized test protocol incorporating the new and modified guidelines provided by Constant together with its reliability and validity assessment. These are the only publications until now that utilize standardized protocols with incorporated updated guidelines for the use of CS and guided us throughout the evaluation process.

Our purpose to provide a standardized test protocol (in both English and Greek) which would fit in an A4-size page was accomplished adding to the score's flexibility in terms of an easy-filling, storing-friendly form. The mean time (minutes:seconds) for completion of the subjective part (A + B) of the Greek CS was 2:45 (range, 2:01–4:10) and none of the questions were left blank by the patients. However, despite our efforts, we were unable to fully standardize all parameters included in the initial guidelines. In particular, the replacement of the unrated VAS pain scale, suggested in the initial publication, by a rated one can be highlighted as a significant deviation from the original recommendations. Ban et al.1 used a 15-centimeter “paper” VAS for both pain and activities and a ruler was used for calculations; this proved to be not practical and caused problems for our patients to understand how to fill this section. Çelik9 graduated the line from 0 to 15 points for pain and from 0 to 4 points for ADL. Our modification was to provide only a numerical scale for pain from 0 to 15. In addition, the modified CS guideline introduced a time period (the previous 24 hours) to assess pain that was incorporated in the text with bold letters (Appendices S1a and S2). Accordingly, a time period for the assessment of ADL (within the past week) in section B was also added with bold letters to assist patients in evaluation of their ADL.3, 25 In section C (range of motion) movements were divided equally in the same table into forward flexion, abduction, external rotation and internal rotation, as in the original versions5, 6 taking into account that the modified version5 highlights also that all movements must be painless and active, a goniometer to be used and the patient has to be in a seated position to avoid spinal tilting. As it is difficult to assess internal and external rotation in a seated position we agreed with Ban et al.1 and Çelik9 that a standing position is better for all movement assessments and the patient has to be closely watched to avoid spinal tilting. Comments and remarks expressed by the medical doctors who participated in the pilot testing procedure regarding internal rotation and abduction measurements led us to add an illustrated appendix (Appendix S3a and b), thus providing instructions on how to perform the different range of motion tests, expanded also to include external rotation measurements. A standardized test protocol was used finally for the strength test (section D). The modified CS advises that strength should be measured by either an Isobex device or a defined spring balance technique. This measurement is recorded at 90° of abduction in the scapular plane with the wrist in a position of pronation, so that the hand is facing downward. The strap is placed on the wrist and the patient is instructed to push maximally upward for 3 s. Verbal encouragement is advisable at this point. The final score is the better score of the 3 measurements. Testing of strength premises absence of pain; if the patient has severe pain the score is 0 as it is if the patient has less than 90° of abduction. In any case, the standardization of “totally painless” movement required during testing abduction strength seems impossible, as the vast majority of the examined patients felt at least minimal pain during the test regardless of the severity of their shoulder condition. All these instructions have been incorporated in our modified CS protocol to facilitate measurements together with an illustrated picture of the appropriate setting and a numerical scale for direct calculation of the score by the physician.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that Constant Score has received much criticism over several issues, it is still widely used to assess the functional status of patients suffering from shoulder disorders. A simple one-paged, standardized English test protocol of the modified Constant Score was developed incorporating all recent modifications of the original score and we suggest its usage for international standardized assessment of the CS. A translation and cultural adaptation of this test into Greek was successfully conducted. The Greek version of the modified Constant Score can be a useful modality in the evaluation of shoulder disorders among Greek patients and doctors achieving good to excellent results in terms of reliability, internal consistency and construct validity. Future studies should be conducted to confirm the responsiveness of the Greek version of the modified CS.

Footnotes

IRB: Not applicable.

Disclaimers: None.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jses.2017.02.004.

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

(a) The initial form of the English version that includes all the sub elements according to the original Constant score and the modified guidelines. (b) The initial, translated into Greek version of the CS.

The final translated form of the CS questionnaire.

Instructions for performing range of motion testing and measurement of strength in English (a) and in Greek (b).

References

- 1.Ban I., Troelsen A., Christiansen D.H., Svendsen S.W., Kristensen M.T. Standardized test protocol (Constant Score) for evaluation of functionality in patients with shoulder disorders. Dan Med J. 2013;60:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaton D.E., Bombardier C., Guillemin F., Ferraz M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3189. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blonna D., Scelsi M., Marini E., Bellato E., Tellini A., Rossi R. Can we improve the reliability of the Constant-Murley score? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conboy V.B., Morris R.W., Kiss J., Carr A.J. An evaluation of the Constant-Murley shoulder assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constant C.R., Gerber C., Emery R.J., Søjbjerg J.O., Gohlke F., Boileau P. A review of the Constant score: modifications and guidelines for its use. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constant C.R., Murley A.H. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook D.A., Beckman T.J. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med. 2006;119:166. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.036. e7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronbach L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Çelik D. Turkish version of the modified Constant-Murley score and standardized test protocol: reliability and validity. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2016;50:69–75. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2016.14.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein J., Santo R.M., Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eremenco S.L., Cella D., Arnold B.J. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschmann M.T., Wind B., Amsler F., Gross T. Reliability of shoulder abduction strength measure for the Constant-Murley score. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1565–1571. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1007-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leggin B., Iannotti J. Shoulder outcome measurement. In: Iannotti J.P., Williams G.R., editors. Disorders of the shoulder: diagnosis and management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 1024–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillkrona U. How should we use the Constant Score? A commentary. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:362–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenna S.P., Doward L.C. The translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health. 2005;8:89–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.08203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson K. Notes on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc R Soc Lond. 1895;58:240–242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocourt M.H., Radlinger L., Kalberer F., Sanavi S., Schmid N.S., Leunig M. Evaluation of intratester and intertester reliability of the Constant-Murley shoulder assessment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy J.S., MacDermid J.C., Woodhouse L.J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Constant-Murley score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrout P.E., Fleiss J.L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperber A.D., Devellis R.F., Boehlecke B. Cross-cultural translation: methodology and validation. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1994;25:501–524. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swaine-Verdier A., Doward L.C., Hagell P., Thorsen H., McKenna S.P. Adapting quality of life instruments. Value Health. 2004;7(Suppl 1):S27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terwee C.B., Bot S.D., de Boer M.R., van der Windt D.A., Knol D.L., Dekker J. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weeks A., Swerissen H., Belfrage J. Issues, challenges, and solutions in translating study instruments. Eval Rev. 2007;31:153–165. doi: 10.1177/0193841x06294184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., Eremenco S., McElroy S., Verjee-Lorenz A., [ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation] Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright R.W., Baumgarten K.M. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:436–444. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) The initial form of the English version that includes all the sub elements according to the original Constant score and the modified guidelines. (b) The initial, translated into Greek version of the CS.

The final translated form of the CS questionnaire.

Instructions for performing range of motion testing and measurement of strength in English (a) and in Greek (b).