Abstract

Background:

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a progressive, enduring, and often irre-versible adverse effect of many antineoplastic agents, among which sensory abnormities are common and the most suffering issues. The pathogenesis of CIPN has not been completely understood, and strategies for CIPN prevention and treatment are still open problems for medicine.

Objectives:

The objective of this paper is to review the mechanism-based therapies against sensory abnormities in CIPN.

Methods:

This is a literature review to describe the uncovered mechanisms underlying CIPN and to provide a summary of mechanism-based therapies for CIPN based on the evidence from both animal and clinical studies.

Results:

An abundance of compounds has been developed to prevent or treat CIPN by blocking ion channels, targeting in-flammatory cytokines and combating oxidative stress. Agents such as glutathione, mangafodipir and duloxetine are expected to be effective for CIPN intervention, while Ca/Mg infusion and venlafaxine, tricyclic antidepressants, and gabapentin dis-play limited efficacy for preventing and alleviating CIPN. And the utilization of erythropoietin, menthol and amifostine needs to be cautious regarding to their side effects.

Conclusions:

Multiple drugs have been used and studied for decades, their effect against CIPN are still controversial ac-cording to different antineoplastic agents due to the diverse manifestations among different antineoplastic agents and complex drug-drug interactions. In addition, novel therapies or drugs that have proven to be effective in animals require further inves-tigation, and it will take time to confirm their efficacy and safety.

Keywords: Antineoplastic agents, adverse effect, CIPN, clinical outcomes, animal study, mechanism, prevention and treatment

1. INTRODUCTION

Chemotherapeutic agents, also known as antineoplastic agents, are used worldwide as the first line of clinical cancer treatment. These agents work by targeting actively growing and dividing cancerous cells. However, these agents also affect normal healthy cells and induce various side effects, such as nausea, dizziness, fatigue, somnolence and insomnia. Among these effects, the impairment of the peripheral nervous system by chemotherapeutic agents results in peripheral neuropathy, a condition referred to as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). CIPN is an important issue affecting chemotherapeutic patients. The antineoplastic agents associated with CIPN include platinum-based drugs (e.g., carboplatin, cisplatin and oxaliplatin), taxanes (e.g., paclitaxel and docetaxel), epothilones (e.g., ixabepilone), vinca alkaloids (e.g., vincristine and vinblastine), bortezomib, and thalidomide. Patients thus frequently suffer progressive, enduring, often irreversible and dose-limiting nerve damage during the administration of antineoplastic drugs.

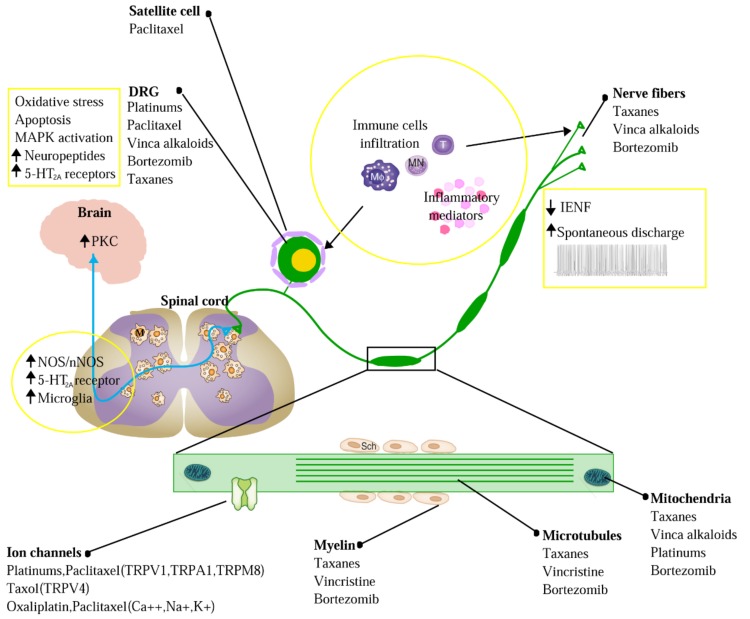

Aggravation of CIPN by chemotherapeutic agents triggers the abnormal cutaneous sensations of tingling, numbness, pressure, persistent pain and thermal hyperalgesia. Although the pathogenesis of CIPN has been studied for decades, it is not completely understood. Accumulated evidence indicates that the initiation and progression of CIPN are tightly related with the impairment of chemotherapeutic agent-induced intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENF) [1], oxidative stress [2], abnormal spontaneous discharge, ion channel activation [3], the up-regulation of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the activation of the neuro-immune system [4, 5] (Fig. 1). Based on these findings, multiple drugs have been used to intervene in CIPN, and their effects have been evaluated over the past several decades.

2. NERVE-PROTECTIVE THERAPY

Although most chemotherapeutic agents do not permeate the blood-brain barrier, they do penetrate the less efficient blood-nerve barrier and can preferentially accumulate in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and nerve terminals [6]. The high concentrations of these drugs result in increased expression of activating transcription factor-3 (ATF-3; a marker of axonal injury), a decreased density of IENFs in limbs, and abnormal nerve conduction velocities (NCVs; indicating damage to axons and the myelin sheath) [1, 7, 8]. The combined damage of peripheral never fibers, axons and myelin sheaths is thought to be closely linked to CIPN.

2.1. Erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a cytokine produced in the kidney that is involved in the regulation of hematopoiesis. EPO has been demonstrated to possess neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties; it enhances nerve regeneration and promotes functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury [9]. Previous studies have shown that EPO partially but significantly prevents the reduction of NCV and IENF loss induced by cisplatin and docetaxel in rodents [10-13]. The clinical application of EPO greatly benefitted the treatment of anemia induced by paclitaxel [14] and cisplatin [15]. EPO therefore is a promising candidate for concomitant use against haematological toxicity and undesirable chemotherapeutic activity. However, because recombinant EPO is associated with tumor cell growth [16], its use as a CIPN treatment must be approached with caution.

2.2. N-acetylcysteine and Glutathione

N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant, activates glutathione peroxidase, resulting in an increase in the whole blood concentration of glutathione [17]. Glutathione prevents the accumulation of platinum adducts in dorsal root ganglia via its high affinity for heavy metals. Glutathione-mediated neuroprotection has also been linked to the prevention of platinum-induced apoptosis by inhibiting the activation of the p53 signaling pathway [18-20]. Treatment with eight cycles of glutathione (1,500 mg/m2) before the delivery of oxaliplatin significantly reduced the incidence of moderate to severe neuropathy (Grade 2-4) compared with a placebo group [21]. Thus, glutathione and its precursor, N-acetylcysteine, appear to be promising options for preventing the development of neurotoxicity induced by platinum-based drugs. Whether these antioxidant drugs will decrease the effect of platinum-based drugs on cancer remains to be evaluated.

3. ION CHANNEL-TARGETED THERAPIES

In addition to morphological impairment, treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs results in enhanced excitability and reduced thresholds in peripheral nociceptors [3, 22]. These electrophysiological changes in neuronal activity are associated with intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations, indicating the involvement of ion channels. Cumulated evidence indicates that the robust activation of voltage-gated sodium, potassium and calcium ion channels, as well as the transient receptor potential (TRP) family, plays a critical role in the pathology of painful CIPN [23-25]. It has been reported that an up-regulation of TRPV1, TRPA1 and the NaV1.6 sodium channel after chemotherapeutic exposure is responsible for the heat/cold evoked pain response [26-29]. In contrast, the inhibition of TRPV4 and voltage-dependent calcium channels resulted in attenuated mechanical allodynia in CIPN animal models [23, 30, 31].

3.1. Lidocaine and Mexiletine

Lidocaine and mexiletine are antiarrhythmic compounds with similar structures and electrophysiologic properties. Both are known to block sodium channels. The effect of lidocaine and mexiletine was first examined in rodent models, which revealed a significant reversion of mechanical and cold allodynia induced by oxaliplatin and vincristine [32-34]. In addition, intravenous lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg in 10 minutes followed by 1.5 mg/kg/h over 5 hours) demonstrated transient anti-allodynic effect in eight out of nine CIPN patients, and persistent analgesic effect (23 days) in five patients [35]. Furthermore, topical lidocaine (5-8%) has a powerful analgesic effect against neuropathic pain associated with diabetes, herpes and trauma [36-38]. However, although lidocaine was demonstrated to improve wrinkle severity in post-chemotherapy patients when administered with hyaluronic acid and abobotulinumtoxin A [39], there remains a lack of convincing evidence supporting its efficacy.

3.2. Calcium and Magnesium Infusion

Calcium and magnesium (Ca/Mg) infusion is one of the most promising strategies used for CIPN prevention. Increasing the extracellular calcium concentration by intravenous delivery of calcium and magnesium facilitates the action of sodium channels, thereby blocking them [40, 41]. In a large phase III study involving 720 advanced colorectal cancer patients, 551 patients received a Ca/Mg infusion (2.25 mmol calcium glubionate and 4 mmol MgCl in 100 mL 5% glucose) prior to chemotherapy. Ca/Mg infusion greatly decreased the incidence of all grades of sensory neurotoxicity induced by oxaliplatin [42]. In another double-blinded trial, Ca/Mg (1 g calcium gluconate combined with 1 g magnesium sulfate) markedly reduced the occurrence of Grade 2 neurotoxicity induced by oxaliplatin [43]. However, in a double-blind phase III study involving 353 patients with colon cancer, intravenous Ca/Mg showed no benefit regarding the incidence of oxaliplatin-induced acute neurotoxicity symptoms (including cold intolerance, muscle cramps, and throat discomfort) as well as the occurrence of Grade 2 neurotoxicity when compared to placebo [44]. Furthermore, another two cases show that Ca/Mg infusions altered neither the acute nor chronic neurotoxicity induced by oxaliplatin [45, 46]. Thus, the utility of Ca/Mg infusion must be further examined.

3.3. Gabapentin and Pregabalin

Gabapentin and pregabalin are anticonvulsants, which display an anti-nociceptive effect through the blockade of voltage gated calcium channels at presynaptic terminals and the down-regulation of excitatory neurotransmitters [47-50]. A powerful analgesic effect of both gabapentin and pregabalin on peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel and oxaliplation has been reported. However, gabapentin did not affect vinctistine-induced allodynia [51, 52]. To evaluate the clinical efficacy of gabapentin, 115 patients with symptomatic CIPN were randomly selected to receive gabapentin (at a target dose of 2700 mg/day in three divided doses) or a placebo, and CIPN-related symptoms were evaluated weekly. CIPN scores were improved in both groups during the trial, but gabapentin did not reduce the average pain compared to the placebo. It has also been reported that gabapentin caused modest side effects, including drowsiness, fatigue and dizziness [53]. In contrast, the effect of pregabalin was successfully demonstrated in three clinical cases, with side effects similar to those of gabapentin [54-56]. Oral administration of pregabalin (at a target dose of 150 mg/day in three divided doses, much less than gabapentin) significantly reduced the severity of sensory neuropathy induced by oxaliplatin by 1-2 grades. However, in a Phase III trial involved 143 patients, pre-administration of oral pregabalin (flexible daily doses of 150–600 mg) during oxaliplatin infusion did not improve chronic pain, as well as the life quality and mood of the cancer patients [57]. Thus, the efficacy of gabapentin and pregabalin against CIPN must be further confirmed.

3.4. Menthol

TRPM8 displays a multifaceted role in cold allodynia [58] and cool-mediated analgesia [59, 60]. Menthol, a natural cooling compound, has been applied for the relief of neuropathic [61] and inflammatory [62] pain. Topical 1% menthol cream applied twice daily for 4-6 weeks to painful areas significantly reduced the neuropathic pain and improved sensation (i.e., alleviated numbness) induced by multiple chemotherapeutic agents in most cases [63, 64]. However, 2 patients suffered worse pain following menthol treatment. Because higher doses of menthol resulted in allodynia [65], an efficient and safe dose of menthol must be carefully selected.

4. ANTI-INFLAMMATORY THERAPIES

Chemotherapeutic drugs lead to the activation of inflammatory cascades and the release of abundant cytokines and chemokines with pro- and anti-inflammatory characteristics, which play an essential role in the pathology of neurotoxic drug-induced nerve damage. These inflammatory mediators contain growth factors, bradykinin, prostaglandins, serotonin, norepinephrine, nitric oxide and interleukins. Among these factors, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, and chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) are the most notably related with CIPN [66]. Chemotherapy-related matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2, MMP3, MMP9 and MMP24) [67, 68] further trigger the initiation and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and CCL2. TNFα and IL-1β directly affect A- and C-fibers and cause spontaneous discharge from these nerves [69], which is associated with the acute and chronic pain induced by paclitaxel and vincristine. The blockage of the nerve growth factor-tyrosine kinase receptor A pathway [70] or treatment with antibodies against TNFα [71] or CCL2 [72], as well as the up-regulation of anti-inflammatory IL-1ra and IL-10 [73], strikingly ameliorated bortezomib- and paclitaxel-induced allodynia. The benefits of blocking pro-inflammatory signaling further emphasize its potential role in the initiation and aggravation of CIPN. Interestingly, this pathological progression involves not only neural cells but also non-neural immune cells; general chemotherapeutic agents are known to result in macrophage infiltration, T lymphocyte recruitment [74-76], Schwann cell activation [77, 78], and an increase in the communication between these cells and satellite cells around DRG neurons.

4.1. Metformin

Metformin is a widely used anti-diabetes drug that activates the adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. Recently, the effect of metformin on CIPN has been reported. Intraperitoneal administration of metformin significantly prevented the impairment of peripheral IENFs and mechanical allodynia, as well as the numbness induced by cisplatin in mice. A similar effect was observed on mechanical allodynia induced by paclitaxel [79]. Additionally, studies have shown that metformin alleviated pain occurring in response to peripheral nerve injury in rodents [80]. The activation of AMPK is believed to block nociceptive progress by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [81]. Furthermore, metformin produced an anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNFα and IL-6) and suppressing the macrophage response via ATF-3 induction in an AMPK-dependent manner [82]. In addition, clinical studies have reported that the AMPK activator metformin effectively reduced neuropathic pain in patients suffering from lumbar radiculopathy pain [81]. These findings urge the inclusion of a systematic assessment of neuropathy in trials using metformin on cancer patients, as well as side effects such as lactic acidosis [83] and hepatocellular and cholestatic hepatic injury [84].

4.2. Minocycline

Minocycline is a widely semisynthetic, second-generation tetracycline derivative with broad-spectrum activity and a long half-life after administration. It is widely accepted that minocycline inhibits the activation of monocytes, decreases the release of proinflammatory cytokines [85], and plays an important role in inhibiting the development and maintenance of hypersensitivity in rats [86]. In 2011, J. Boyette-Davis et al. reported that minocycline treatment effectively prevented the loss of IENFs and mechanical sensitivity in oxaliplatin- and taxol- treated animals [7, 87]. In 2017, a polit study reported that minocycline (100 mg twice daily) did not reduce the overall sensory neuropathy (including tingling, burning pain and numbness) associated with paclitaxel. However, minocycline significantly decreased the average pain score and fatigue when compared to placebo [88]. Additionally, researchers have shown that minocycline exhibits anti-inflammatory [89], anti-apoptotic [90], and free-radical scavenging effects [91], and also possesses anti-tumorigenic potential [92]. Therefore, minocycline might be a promising candidate for CIPN prevention and treatment. However, there is no clinical evidence to support the neuroprotective efficiency of minocycline in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Large clinical trials and animal studies are needed to uncover its effect on CIPN.

5. NEUROTRANSMITTER-BASED THERAPY

The monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine have been known to participate in the descending inhibitory nociception pathway and to play an important role in opioid-mediated supraspinal analgesia [93]. Recent data have demonstrated a stronger anti-nociceptive effect of norepinephrine than serotonin [94], and an increase in both norepinephrine and serotonin results in a greater analgesic effect than an increase in either one alone [95]. These data suggest that targeting serotonin and norepinephrine may represent an efficient strategy in treating painful CIPN. It is necessary to evaluate the effect of the most commonly used monoamine reuptake inhibitors, including serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), on CIPN.

5.1. Venlafaxine and Duloxetine

Venlafaxine, which inhibits serotonin more strongly at lower doses and inhibits norepinephrine at higher doses, has been used as a preventive strategy against CIPN [50]. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial, venlafaxine (37.5 mg b.i.d. for ten days) along with oxaliplatin infusion significantly reduced the incidence of peripheral neuropathy compared with a placebo. Although venlafaxine displayed clinical activity against oxaliplatin-induced symptomatic acute neurosensory toxicity, its side effects, including nausea (43.1%) and asthenia (39.2%), should not be ignored [96].

Unlike venlafaxine, the inhibition by duloxetine of serotonin and norepinephrine is relatively balanced, and duloxetine has been applied to treat rather than prevent CIPN in the clinic [95]. Recently, duloxetine was the subject of a large clinical trial to determine its effect on chemotherapy-induced pain. 231 patients were divided into two groups: those receiving duloxetine during the initial treatment period and a placebo during crossover period as one group, and the opposite administration order as the other. At the end of the initial period, compared to placebo group, the duloxetine group reported a larger decrease in average pain and impaired life function due to pain, as well as relief in numbness and tingling in 41% patients. Interestingly, a greater benefit was observed in platinum-treated patients than in taxanes-treated patients in terms of analgesia. In addition, compared to venlafaxine, fewer adverse effects were reported after duloxetine administration [97]. All of these data suggest that duloxetine may improve CIPN therapy over venlafaxine [98]. However, a direct comparison is necessary.

5.2. Tricyclic Antidepressants

Amitriptyline, desipramine and nortriptyline are tricyclic antidepressants that are known to work through the serotonin/norepinephrine pathway [99]. Although repeated amitriptyline administration reduced mechanical allodynia but not cold hyperalgesia in oxaliplatin-treated rats [100], human studies did not report any benefits of amitriptyline in either the prevention or attenuation of CIPN [101-103]. A phase III trial of 51 patients was designed to evaluate the use of nortriptyline for the alleviation of the symptoms of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy [104]. Nortriptyline was reported to cause a dramatic decrease in pain when compared to a placebo. However, no difference in paresthesiae was observed. In addition, tricyclic antidepressants may also participate in anticholinergic, antihistaminergic, and antiadrenergic progress, leading to systemic side effects including dry mouth, drowsiness, weight gain, and orthostatism [105]. These data suggest that CIPN is more complex than other neuropathic pain syndromes, and tricyclic antidepressants alone are not sufficient for CIPN therapy.

6. ANTIOXIDANTS

One of the anti-neoplastic actions of chemotherapy is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to induce apoptosis in cancer cells [2]. However, various oxidative stresses have been detected in the peripheral and spinal nerve systems in response to chemotherapy. Increased neuronal oxidative stress has been reported to expend endogenous antioxidants, affect bioenergetic metabolism, activate ion channels, and promote the occurrence of inflammatory events [106-110]. These pathological changes result in neuronal apoptosis and structural damage in nerves, including microtubular disruption and demyelination [111]. Therefore, oxidative stress-mediated neurodegeneration is believed to be closely linked with CIPN.

6.1. Amifostine

Amifostine is a cytoprotective antioxidant that acts by accelerating DNA repair and suppressing Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis [112]. Amifostine exerts a protective effect against nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and ototoxicity [113, 114]. Several placebo-controlled and/or random trials have investigated the effect of amifostine on the neurotoxicity induced by cisplatin, carboplatin, doxorubicin and paclitaxel. In patients subjected to chemotherapy, premedication with amifostine (740 mg/m2) protected against sensory neuropathy induced by carboplatin/paclitaxel compared to a placebo [115]. Furthermore, a significant remission in severe clinical neuropathy induced by paclitaxel [116] and a decrease in cisplatin resulted in neurotoxicity after six cycles of treatment [117]. Hypocalcemia, hypotension, vomiting, sneezing and nausea are the most common side effects of amifostine treatment [115, 118].

6.2. Mangafodipir

The contrast agent mangafodipir is utilized clinically for magnetic resonance imaging of the liver with no side effects. Mangafodipir is now considered an antioxidant due to its superoxide dismutase mimetic activity resulting from chelate bonding. This property lends mangafodipir a cytoprotective effect against chemotherapy [119]. It has also been shown that compared to a placebo, intravenous delivery of mangafodipir (0.2 mL/kg) before oxaliplatin treatment significantly reduced severe neuropathy events [120]. Furthermore, in a phase II study, intravenous administration of mangafodipir after oxaliplatin treatment for four cycles resulted in an improvement or stabilization in neuropathy, and after eight cycles, a sustainable downgrade or stabilization was reported [121]. These data suggest that mangafodipir could play a pivotal role in CIPN prevention and treatment. However, the toxicity of manganese limits the clinical use of mangafodipir. Thus, the replacement of Mn2+ (i.e., by Ca2+) [122] may be beneficial for developing novel therapies for CIPN.

7. COMBINED MEDICINE

Combined medicine has attracted increasing attention for use in CIPN intervention. Medics introduced a combination of tricyclic antidepressants and others drugs, including antiepileptics and opioids, in the form of topical creams [123, 124]. A topical gel containing baclofen (10 mg), amitriptyline HCL (40 mg), and ketamine (20 mg) in a pluronic lecithin organogel (BAK-PLO) was evaluated for its efficacy in treating CIPN. Patients who received BAK-PLO for four weeks reported a marked reduction in tingling, cramping, and shooting/burning pains when compared to placebo-treated patients [125]. The efficacy of an amitriptyline-katamine (KA) cream containing 2% ketamine and 4% amitriptyline was further tested in a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 462 patients, who were asked weekly to describe any numbness, pain or tingling that they were experiencing. Unfortunately, KA cream displayed only a weak improvement in CIPN over a six-week period [103]. Notably, no evident systemic toxicity was observed in either case.

Additional drugs such as the nerve protective agent olesoxime and the ion channel-targeting neurosteroids have been established promising effect on CIPN in preclinical studies, which, however, are required to be further confirmed in human studies (Table 1). Besides, nutraceuticals, including acety-L-carnitine, glutamine, vitamin E and A-Lipoic acid, have also been applied for CIPN intervention but achieved little positive clinical outcomes (Table 2) [126].

8. CONCLUSION

CIPN is a common dose-limiting adverse condition caused by motor, sensory and autonomic nerve impairment induced by antineoplastic agents, of which sensory deficits are the most prominent clinically. Based on the pathogenesis of CIPN, an abundance of compounds has been developed to prevent or treat CIPN by blocking ion channels, targeting inflammatory cytokines and combating oxidative stress. The current effective mechanism-based therapeutics such as glutathione and mangafodipir appear to be promising for preventing the CIPN, while duloxetine is expected to be effective for CIPN treatment. However, more well-designed clinical studies are required regarding the type of chemotherapeutic agents used and their side effects. In addition, quite a few preclinical studies have investigated the promising effect of agents such as minocycline and metformin against pain and numbness in CIPN associated with taxol, paclitaxel and platinum drugs, as well as the protective effect on IENFs. Further investigations should be conducted to confirm their efficacy and safety on human.

Fig. (1).

Sketch-map of the mechanism of CIPN. CIPN was initiated and progressed by chemotherapeutic-agents through intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENF) impairment, oxidative stress, abnormal spontaneous discharge, activation of ion channels, up-regulation of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the activation of neuro-immune system. Solid dots refer to the target of different chemotherapeutic agents. Contents in the yellow boxes refer to the pathological progress in peripheral and central nerve systems underlying CIPN. Abbreviation: MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; IENF, intraepidermal nerve fiber; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; T, T lymphocyte; MN, monocytes; MΦ, macrophage; M, microglia; Sch, Schwann cell.

Table 1.

Promising agents based on preclinical study.

|

Possible

Mechanism |

Trail | Dose | Chemotherapeutic Drugs | Outcome | Adverse Effect | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve-Protective Agents | |||||||

| Olesoxime | Mitochondrial proteins in the specific neuroactive steroid binding site [127] | Rat | Vincristine, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin |

Prevented the degeneration of sensory terminal arbor; reduced the mechanical allodynia |

[128-130] | ||

| Monastrol | Kinesin-5 inhibitor | Mouse | Bortezomib | Alleviated axonal injury | [131] | ||

| Ion Channel Targeted Agents | |||||||

| Neurosteroid (3α-androstanediol and allopregnanolone) | L- and T-type calcium and gabaа channel [132] | Rat | Vincristine, oxaliplatin and paclitaxel |

Repair the IENF loss; normalize NCV; suppressed the thermal hypersensitivity and mechanical allodynia |

[133-135] | ||

| Antioxidants | |||||||

| Vitamin E | Antioxidation | Preclinical | 300 mg/day | Cisplatin | Decreased the incidence and severity of PN* | Diarrhea [136] | [137] |

| Carvedilol | Antioxidant and mitoprotective properties | Rat | 10 mg/kg | Oxaliplatin | Reduce the IENF loss; normalize NCV; decrease mechanical allodynia |

[138] | |

| Anti-Inflammatory Agents | |||||||

| Minocycline | Inhibition the activation of monocytes | Rat | 25 mg/kg/day for 4 days | Oxaliplatin | Repair the IENF loss;; suppressed mechanical allodynia | [87] | |

| Rat | 10 mg/kg/day for 7 days | Taxol | Repair the IENF loss;; suppressed mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia | [139] | |||

| Thalidomide | Immunomodulatory effect | Rat | 50 mg/kg/day for 7 days | Taxol | Repair the IENF loss;; suppressed mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia |

[139] | |

| Metformin | AMPK activator | Mouse | 200 mg/kg/day for 14 days | Cisplatin Paclitaxel |

Repair the IENF loss;; suppressed sensory deficits and mechanical allodynia | [79] | |

| Pifithrin-μ | Inhibitor of p53 | Mouse | 8 mg/kg/day for 10 days | Cisplatin | Prevent the IENFs loss;; suppressed numbness and mechanical allodynia | [140] | |

*As reported in the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.03 (NCI-CTCAe v4.03). Abbreviation: AMPK, adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase; PN, peripheral neuropathy; GABA, γ-Aminobutyric acid; IENF, intraepidermal nerve fiber; NCV, nerve conduction velocity.

Table 2.

Drugs that have been demonstrated no benefits in clinic.

|

Possible

Mechanism |

Trail | Dose | Chemotherapeutic Drugs | Outcome | Adverse Effect | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve-Protective Agents | |||||||

| Acety-L-carnitine | Neurotrophic factor [141] PKCγ and MAPKs [142] |

Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | 3,000 mg/day | Taxane | No effect and increased PN after 24 weeks’ treatment | [143] | |

| ex vivo | Paclitaxel and carboplatin |

No effect | [144] | ||||

| Pilot study | Paclitaxel and cisplatin |

Decreased PN severity * | Insomnia | [145] | |||

| Double-blind, randomized phase II | 1,000 mg every 3 days | Sagopilone | Lowered incidence of grade 3 or 4* | [146] | |||

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Decreased PN severity and fatigue; improving physical conditions | [147] | |||||

| Glutamine | Nerve growth factor [125] | Pilot study | 15 g twice a day for seven consecutive days every 2 weeks | Oxaliplatin | Reduced the incidence and severity of PN* | [148] | |

| Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trail |

30 g/day | Docetaxel and paclitaxel |

No effect | [149-151] | |||

| Ion Channel Targeted Agents | |||||||

| Carbamazepine | Voltage-gated sodium channels | Randomized, controlled, multicenter phase II |

4–6 mg/L plasma | Oxaliplatin | No effect | Hyponatremia and drug interactions | [152] |

| Oxcarbazepine | Randomized, openlabel, controlled |

600mg twice a day | Oxaliplatin | Reduced severity of PN* | [153] | ||

| Antioxidants | |||||||

| Vitamin E | Antioxidation | Randomized phase III | 400 mg/day | Taxanes, cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin or combination |

No effect | [154] | |

| Α-Lipoic acid | Disulfide at C6 and C8 can be oxidized by free-radical-mediated oxidative stress |

Double-blind and placebo-controlled | 1800 mg/day | Oxaliplatin, cisplatin or combined | No significant benefits on pain or functional outcomes | [155] | |

| Vitamin B | Numerous Intermediary metabolic pathways |

Pilot, randomised, placebo-controlled | Two capsules** daily |

Oxaliplatin, taxanes or vincristine | No significant benefits | [156] | |

*As reported in the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.03 (NCI-CTCAe v4.03). Abbreviations: PKC, protein kinase C; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PN, peripheral neuropathy.

**Vintamin B capsules: 50 mg of thiamine, 20 mg of riboflavin, 100 mg of niacin, 163.5 mg of pantothenic acid, 30 mg of pyridoxine, 500 μg of folate, 500 μg of cyanocobalamin, 500 μg of biotin, 100 mg of choline and 500 μg of inositol.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review was financially supported by the National Natural Science Funds of China (81371247 and 81473749), the National Key Basic Research program of China (2013CB531906) and the Development Project of Shanghai Peak Disciplines-Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koskinen M.J., Kautio A.L., Haanpää M.L., Haapasalo H.K., Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P.L., Saarto T., Hietaharju A.J. Intraepidermal nerve fibre density in cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(12):4413–4416. [PMID: 22199308]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butturini E., Carcereri de Prati A., Chiavegato G., Rigo A., Cavalieri E., Darra E., Mariotto S. Mild oxidative stress induces S-glutathionylation of STAT3 and enhances chemosensitivity of tumoural cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;65:1322–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.015. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed. 2013.09.015]. [PMID: 24095958]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H., Dougherty P.M. Enhanced excitability of primary sensory neurons and altered gene expression of neuronal ion channels in dorsal root ganglion in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(6):1463–1475. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000176. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000176]. [PMID: 24534904]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisignano M., Baron R., Scholich K., Geisslinger G. Mechanism-based treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014;10(12):694–707. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.211. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.211]. [PMID: 25366108]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makker P.G., Duffy S.S., Lees J.G., Perera C.J., Tonkin R.S., Butovsky O., Park S.B., Goldstein D., Moalem-Taylor G. Characterisation of immune and neuroinflammatory changes associated with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170814. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0170814]. [PMID: 28125674]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavaletti G., Cavalletti E., Oggioni N., Sottani C., Minoia C., D’Incalci M., Zucchetti M., Marmiroli P., Tredici G. Distribution of paclitaxel within the nervous system of the rat after repeated intravenous administration. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21(3):389–393. [PMID: 10894128]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyette-Davis J., Xin W., Zhang H., Dougherty P.M. Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain. 2011;152(2):308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.030. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.pain.2010.10.030]. [PMID: 21145656]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamieson S.M., Liu J.J., Connor B., Dragunow M., McKeage M.J. Nucleolar enlargement, nuclear eccentricity and altered cell body immunostaining characteristics of large-sized sensory neurons following treatment of rats with paclitaxel. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28(6):1092–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.009]. [PMID: 17686523]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin Z.S., Zhang H., Bo W., Gao W. Erythropoietin promotes functional recovery and enhances nerve regeneration after peripheral nerve injury in rats. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010;31(3):509–515. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1820. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1820]. [PMID: 20037135]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassem L.A., Yassin N.A. Role of erythropoeitin in prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2010;13(12):577–587. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.577.587. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2010.577. 587]. [PMID: 21061908]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cervellini I., Bello E., Frapolli R., Porretta-Serapiglia C., Oggioni N., Canta A., Lombardi R., Camozzi F., Roglio I., Melcangi R.C., D’incalci M., Lauria G., Ghezzi P., Cavaletti G., Bianchi R. The neuroprotective effect of erythropoietin in docetaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy causes no reduction of antitumor activity in 13762 adenocarcinoma-bearing rats. Neurotox. Res. 2010;18(2):151–160. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9127-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12640-009-9127-9]. [PMID: 19876698]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bianchi R., Brines M., Lauria G., Savino C., Gilardini A., Nicolini G., Rodriguez-Menendez V., Oggioni N., Canta A., Penza P., Lombardi R., Minoia C., Ronchi A., Cerami A., Ghezzi P., Cavaletti G. Protective effect of erythropoietin and its carbamylated derivative in experimental Cisplatin peripheral neurotoxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(8):2607–2612. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2177. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2177]. [PMID: 16638873]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianchi R., Gilardini A., Rodriguez-Menendez V., Oggioni N., Canta A., Colombo T., De Michele G., Martone S., Sfacteria A., Piedemonte G., Grasso G., Beccaglia P., Ghezzi P., D’Incalci M., Lauria G., Cavaletti G. Cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: neuroprotection by erythropoietin without affecting tumour growth. Eur. J. Cancer. 2007;43(4):710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.028. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.ejca.2006.09.028]. [PMID: 17251006]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber B., Largillier R., Ray-Coquard I., Yazbek G., Meunier J., Alexandre J., Dauba J., Spaeth D., Delva R., Joly F., Pujade-Lauraine E., Copel L. A potentially neuroprotective role for erythropoietin with paclitaxel treatment in ovarian cancer patients: a prospective phase II GINECO trial. Support. Care Cancer. 2013;21(7):1947–1954. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1748-0. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1748-0]. [PMID: 23420555]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomaidis T., Weinmann A., Sprinzl M., Kanzler S., Raedle J., Ebert M., Schimanski C.C., Galle P.R., Hoehler T., Moehler M. Erythropoietin treatment in chemotherapy-induced anemia in previously untreated advanced esophagogastric cancer patients. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;19(2):288–296. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0544-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s10147-013-0544-7]. [PMID: 23532629]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradeep S., Huang J., Mora E.M., Nick A.M., Cho M.S., Wu S.Y., Noh K., Pecot C.V., Rupaimoole R., Stein M.A., Brock S., Wen Y., Xiong C., Gharpure K., Hansen J.M., Nagaraja A.S., Previs R.A., Vivas-Mejia P., Han H.D., Hu W., Mangala L.S., Zand B., Stagg L.J., Ladbury J.E., Ozpolat B., Alpay S.N., Nishimura M., Stone R.L., Matsuo K., Armaiz-Peña G.N., Dalton H.J., Danes C., Goodman B., Rodriguez-Aguayo C., Kruger C., Schneider A., Haghpeykar S., Jaladurgam P., Hung M.C., Coleman R.L., Liu J., Li C., Urbauer D., Lopez-Berestein G., Jackson D.B., Sood A.K. Erythropoietin stimulates tumor Growth via EphB4. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(5):610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.008. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.008]. [PMID: 26481148]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S., Raghuvanshi B.P., Shukla S. Toxic effects of lead exposure in rats: involvement of oxidative stress, genotoxic effect, and the beneficial role of N-acetylcysteine supplemented with selenium. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2014;33(1):19–32. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2014009712. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2014009712]. [PMID: 24579807]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park I.H., Kim M.K., Kim S.U. Ursodeoxycholic acid prevents apoptosis of mouse sensory neurons induced by cisplatin by reducing P53 accumulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;377(4):1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.014. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.014]. [PMID: 18558085]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S.A., Choi K.S., Bang J.H., Huh K., Kim S.U. Cisplatin-induced apoptotic cell death in mouse hybrid neurons is blocked by antioxidants through suppression of cisplatin-mediated accumulation of p53 but not of Fas/Fas ligand. J. Neurochem. 2000;75(3):946–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750946.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750946.x]. [PMID: 10936175]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bragado P., Armesilla A., Silva A., Porras A. Apoptosis by cisplatin requires p53 mediated p38alpha MAPK activation through ROS generation. Apoptosis. 2007;12(9):1733–1742. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0082-8. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1007/s10495-007-0082-8]. [PMID: 17505786]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cascinu S., Catalano V., Cordella L., Labianca R., Giordani P., Baldelli A.M., Beretta G.D., Ubiali E., Catalano G. Neuroprotective effect of reduced glutathione on oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(16):3478–3483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.061. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.07.061]. [PMID: 12177109]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carozzi V.A., Renn C.L., Bardini M., Fazio G., Chiorazzi A., Meregalli C., Oggioni N., Shanks K., Quartu M., Serra M.P., Sala B., Cavaletti G., Dorsey S.G. Bortezomib-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: an electrophysiological, behavioral, morphological and mechanistic study in the mouse. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072995. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072995]. [PMID: 24069168]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami K., Chiba T., Katagiri N., Saduka M., Abe K., Utsunomiya I., Hama T., Taguchi K. Paclitaxel increases high voltage-dependent calcium channel current in dorsal root ganglion neurons of the rat. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;120(3):187–195. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12123fp. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1254/jphs.12123FP]. [PMID: 23090716]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagiava A., Tsingotjidou A., Emmanouilides C., Theophilidis G. The effects of oxaliplatin, an anticancer drug, on potassium channels of the peripheral myelinated nerve fibres of the adult rat. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(6):1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.09.005. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.neuro.2008.09.005]. [PMID: 18845186]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adelsberger H., Quasthoff S., Grosskreutz J., Lepier A., Eckel F., Lersch C. The chemotherapeutic oxaliplatin alters voltage-gated Na(+) channel kinetics on rat sensory neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;406(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00667-1. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00667-1]. [PMID: 11011028]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anand U., Otto W.R., Anand P. Sensitization of capsaicin and icilin responses in oxaliplatin treated adult rat DRG neurons. Mol. Pain. 2010;6:82. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-82. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-6-82]. [PMID: 21106058]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nassini R., Gees M., Harrison S., De Siena G., Materazzi S., Moretto N., Failli P., Preti D., Marchetti N., Cavazzini A., Mancini F., Pedretti P., Nilius B., Patacchini R., Geppetti P. Oxaliplatin elicits mechanical and cold allodynia in rodents via TRPA1 receptor stimulation. Pain. 2011;152(7):1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.051. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.051]. [PMID: 21481532]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sittl R., Lampert A., Huth T., Schuy E.T., Link A.S., Fleckenstein J., Alzheimer C., Grafe P., Carr R.W. Anticancer drug oxaliplatin induces acute cooling-aggravated neuropathy via sodium channel subtype Na(V)1.6-resurgent and persistent current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(17):6704–6709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118058109. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1118058109]. [PMID: 22493249]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ta L.E., Bieber A.J., Carlton S.M., Loprinzi C.L., Low P.A., Windebank A.J. Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 is essential for cisplatin-induced heat hyperalgesia in mice. Mol. Pain. 2010;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-15. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-6-15]. [PMID: 20205720]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flatters S.J., Bennett G.J. Ethosuximide reverses paclitaxel- and vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2004;109(1-2):150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.029. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.029]. [PMID: 15082137]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alessandri-Haber N., Dina O.A., Yeh J.J., Parada C.A., Reichling D.B., Levine J.D. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 is essential in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2004;24(18):4444–4452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0242-04.2004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/ JNEUROSCI.0242-04.2004]. [PMID: 15128858]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egashira N., Hirakawa S., Kawashiri T., Yano T., Ikesue H., Oishi R. Mexiletine reverses oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain in rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;112(4):473–476. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10012sc. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1254/jphs.10012SC]. [PMID: 20308797]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamei J., Nozaki C., Saitoh A. Effect of mexiletine on vincristine-induced painful neuropathy in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;536(1-2):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.033. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.033]. [PMID: 16556439]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling B., Authier N., Balayssac D., Eschalier A., Coudore F. Behavioral and pharmacological description of oxaliplatin-induced painful neuropathy in rat. Pain. 2007;128(3):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.016. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.016]. [PMID: 17084975]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Heuvel S.A.S., van der Wal S.E.I., Smedes L.A., Radema S.A., van Alfen N., Vissers K.C.P., Steegers M.A.H. Intravenous lidocaine: Old-school drug, new purposer of intractable Pain in Patients with chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Pain Res. Manag. 2017;2017:8053474. doi: 10.1155/2017/8053474. [PMID: 28458593]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanai A., Segawa Y., Okamoto T., Koto M., Okamoto H. The analgesic effect of a metered-dose 8% lidocaine pump spray in posttraumatic peripheral neuropathy: a pilot study. Anesth. Analg. 2009;108(3):987–991. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819431aa. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013 e31819431aa]. [PMID: 19224814]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navez M.L., Monella C., Bösl I., Sommer D., Delorme C. 5% Lidocaine medicated plaster for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: A review of the clinical safety and tolerability. Pain Ther. 2015;4(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s40122-015-0034-x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40122-015-0034-x]. [PMID: 25896574]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolff R.F., Bala M.M., Westwood M., Kessels A.G., Kleijnen J. 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN): a systematic review. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010;140(21-22):297–306. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.12995. [PMID: 20458651]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shamban A. Safety and efficacy of facial rejuvenation with small gel particle hyaluronic acid with lidocaine and abobotulinumtoxinA in Post-chemotherapy patients: A Phase IV investigator-initiated Study. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2014;7(1):31–36. [PMID: 24563694]. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaoka K., Vogel S.M., Seyama I. Na+ channel pharmacology and molecular mechanisms of gating. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12(4):429–442. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474468. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/138161206775474468]. [PMID: 16472137]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armstrong C.M., Cota G. Calcium block of Na+ channels and its effect on closing rate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96(7):4154–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4154. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.7.4154]. [PMID: 10097179]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knijn N., Tol J., Koopman M., Werter M.J., Imholz A.L., Valster F.A., Mol L., Vincent A.D., Teerenstra S., Punt C.J. The effect of prophylactic calcium and magnesium infusions on the incidence of neurotoxicity and clinical outcome of oxaliplatin-based systemic treatment in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47(3):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.006. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca. 2010.10.006]. [PMID: 21067912]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grothey A., Nikcevich D.A., Sloan J.A., Kugler J.W., Silberstein P.T., Dentchev T., Wender D.B., Novotny P.J., Chitaley U., Alberts S.R., Loprinzi C.L. Intravenous calcium and magnesium for oxaliplatin-induced sensory neurotoxicity in adjuvant colon cancer: NCCTG N04C7. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(4):421–427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5911. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5911]. [PMID: 21189381]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loprinzi C.L., Qin R., Dakhil S.R., Fehrenbacher L., Flynn K.A., Atherton P., Seisler D., Qamar R., Lewis G.C., Grothey A. Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of intravenous calcium and magnesium to prevent oxaliplatin-induced sensory neurotoxicity (N08CB/Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.0536. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.0536]. [PMID: 24297951]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han C.H., Khwaounjoo P., Kilfoyle D.H., Hill A., McKeage M.J. Phase I drug-interaction study of effects of calcium and magnesium infusions on oxaliplatin pharmacokinetics and acute neurotoxicity in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:495. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-495. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-495]. [PMID: 24156389]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ao R., Wang Y.H., Li R.W., Wang Z.R. Effects of calcium and magnesium on acute and chronic neurotoxicity caused by oxaliplatin: A meta-analysis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2012;4(5):933–937. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.678. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/etm.2012.678]. [PMID: 23226752]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer C.S., Nieto-Rostro M., Rahman W., Tran-Van-Minh A., Ferron L., Douglas L., Kadurin I., Sri Ranjan Y., Fernandez-Alacid L., Millar N.S., Dickenson A.H., Lujan R., Dolphin A.C. The increased trafficking of the calcium channel subunit alpha2delta-1 to presynaptic terminals in neuropathic pain is inhibited by the alpha2delta ligand pregabalin. J. Neurosci. 2009;29(13):4076–4088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0356-09.2009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0356-09.2009]. [PMID: 19339603]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauer C.S., Rahman W., Tran-van-Minh A., Lujan R., Dickenson A.H., Dolphin A.C. The anti-allodynic alpha(2)delta ligand pregabalin inhibits the trafficking of the calcium channel alpha(2)delta-1 subunit to presynaptic terminals in vivo. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38(2):525–528. doi: 10.1042/BST0380525. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/ BST0380525]. [PMID: 20298215]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kukkar A., Bali A., Singh N., Jaggi A.S. Implications and mechanism of action of gabapentin in neuropathic pain. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2013;36(3):237–251. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0057-y. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s12272-013-0057-y]. [PMID: 23435945]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piccolo J., Kolesar J.M. Prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2014;71(1):19–25. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130126. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2146/ajhp130126]. [PMID: 24352178]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng P., Xi Q., Xia S., Zhuang L., Gui Q., Chen Y., Huang Y., Zou M., Rao J., Yu S. Pregabalin attenuates docetaxel-induced neuropathy in rats. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 2012;32(4):586–590. doi: 10.1007/s11596-012-1001-y. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11596-012-1001-y]. [PMID: 22886975]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gauchan P., Andoh T., Ikeda K., Fujita M., Sasaki A., Kato A., Kuraishi Y. Mechanical allodynia induced by paclitaxel, oxaliplatin and vincristine: different effectiveness of gabapentin and different expression of voltage-dependent calcium channel alpha(2)delta-1 subunit. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32(4):732–734. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.732. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1248/bpb.32.732]. [PMID: 19336915]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rao R.D., Michalak J.C., Sloan J.A., Loprinzi C.L., Soori G.S., Nikcevich D.A., Warner D.O., Novotny P., Kutteh L.A., Wong G.Y. Efficacy of gabapentin in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial (N00C3). Cancer. 2007;110(9):2110–2118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23008. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23008]. [PMID: 17853395]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saif M.W., Hashmi S. Successful amelioration of oxaliplatin-induced hyperexcitability syndrome with the antiepileptic pregabalin in a patient with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2008;61(3):349–354. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0584-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s00280-007-0584-7]. [PMID: 17849118]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saif M.W., Syrigos K., Kaley K., Isufi I. Role of pregabalin in treatment of oxaliplatin-induced sensory neuropathy. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(7):2927–2933. [PMID: 20683034]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takenaka M., Iida H., Matsumoto S., Yamaguchi S., Yoshimura N., Miyamoto M. Successful treatment by adding duloxetine to pregabalin for peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2013;30(7):734–736. doi: 10.1177/1049909112463416. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1177/1049909112463416]. [PMID: 23064035]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Andrade D.C., Jacobsen T.M., Galhardoni R., Ferreira K.S.L., Braz Mileno P., Scisci N., Zandonai A., Teixeira W.G.J., Saragiotto D.F., Silva V., Raicher I., Cury R.G., Macarenco R., Otto H.C., Wilson Iervolino B.M., Andrade de Mello A., Zini Megale M., Henrique Curti Dourado L., Mendes B.L., Lilian R.A., Parravano D., Tizue F.J., Lefaucheur J.P., Bouhassira D., Sobroza E., Richelmann R.P., Hoff P.M., PreOx W., Valerio da Silva F., Chile T., Dale C.S., Nebuloni D., Senna L., Brentani H., Pagano R.L., de Souza A.M. Pregabalin for the prevention of oxaliplatin-induced painful neuropathy: A randomized, double-blind trial. Oncologist. 2017 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0235. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist. 2017-0235]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xing H., Chen M., Ling J., Tan W., Gu J.G. TRPM8 mechanism of cold allodynia after chronic nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(50):13680–13690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2203-07.2007. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/ JNEUROSCI.2203-07.2007]. [PMID: 18077679]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Proudfoot C.J., Garry E.M., Cottrell D.F., Rosie R., Anderson H., Robertson D.C., Fleetwood-Walker S.M., Mitchell R. Analgesia mediated by the TRPM8 cold receptor in chronic neuropathic pain. Curr. Biol. 2006;16(16):1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.061. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.cub.2006.07.061]. [PMID: 16920620]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knowlton W.M., Palkar R., Lippoldt E.K., McCoy D.D., Baluch F., Chen J., McKemy D.D. A sensory-labeled line for cold: TRPM8-expressing sensory neurons define the cellular basis for cold, cold pain, and cooling-mediated analgesia. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(7):2837–2848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1943-12.2013. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI. 1943-12.2013]. [PMID: 23407943]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wasner G., Naleschinski D., Binder A., Schattschneider J., McLachlan E.M., Baron R. The effect of menthol on cold allodynia in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2008;9(3):354–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00290.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00290.x]. [PMID: 18366513]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu B., Fan L., Balakrishna S., Sui A., Morris J.B., Jordt S-E. TRPM8 is the principal mediator of menthol-induced analgesia of acute and inflammatory pain. Pain. 2013;154(10):2169–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.043. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.043]. [PMID: 23820004]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fallon M.T., Storey D.J., Krishan A., Weir C.J., Mitchell R., Fleetwood-Walker S.M., Scott A.C., Colvin L.A. Cancer treatment-related neuropathic pain: proof of concept study with menthol--a TRPM8 agonist. Support. Care Cancer. 2015;23(9):2769–2777. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2642-8. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2642-8]. [PMID: 25680765]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colvin L.A., Johnson P.R., Mitchell R., Fleetwood-Walker S.M., Fallon M. From bench to bedside: a case of rapid reversal of bortezomib-induced neuropathic pain by the TRPM8 activator, menthol. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(27):4519–4520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.5017. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.5017]. [PMID: 18802169]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mahn F., Hüllemann P., Wasner G., Baron R., Binder A. Topical high-concentration menthol: reproducibility of a human surrogate pain model. Eur. J. Pain. 2014;18(9):1248–1258. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.484.x. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.484.x]. [PMID: 24777959]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diezi M., Buclin T., Kuntzer T. Toxic and drug-induced peripheral neuropathies: updates on causes, mechanisms and management. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2013;26(5):481–488. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328364eb07. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e328364eb07]. [PMID: 23995278]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawasaki Y., Xu Z.Z., Wang X., Park J.Y., Zhuang Z.Y., Tan P.H., Gao Y.J., Roy K., Corfas G., Lo E.H., Ji R.R. Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat. Med. 2008;14(3):331–336. doi: 10.1038/nm1723. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1723]. [PMID: 18264108]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X.M., Lehky T.J., Brell J.M., Dorsey S.G. Discovering cytokines as targets for chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Cytokine. 2012;59(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.027. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.cyto.2012.03.027]. [PMID: 22537849]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schäfers M., Sorkin L. Effect of cytokines on neuronal excitability. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;437(3):188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.052. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.neulet.2008.03.052]. [PMID: 18420346]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakahashi Y., Kamiya Y., Funakoshi K., Miyazaki T., Uchimoto K., Tojo K., Ogawa K., Fukuoka T., Goto T. Role of nerve growth factor-tyrosine kinase receptor A signaling in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;444(3):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.082. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc. 2014.01.082]. [PMID: 24480438]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alé A., Bruna J., Morell M., van de Velde H., Monbaliu J., Navarro X., Udina E. Treatment with anti-TNF alpha protects against the neuropathy induced by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in a mouse model. Exp. Neurol. 2014;253:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.020. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.020]. [PMID: 24406455]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pevida M., Lastra A., Hidalgo A., Baamonde A., Menéndez L. Spinal CCL2 and microglial activation are involved in paclitaxel-evoked cold hyperalgesia. Brain Res. Bull. 2013;95:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.03.005. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2013.03.005]. [PMID: 23562605]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ledeboer A., Jekich B.M., Sloane E.M., Mahoney J.H., Langer S.J., Milligan E.D., Martin D., Maier S.F., Johnson K.W., Leinwand L.A., Chavez R.A., Watkins L.R. Intrathecal interleukin-10 gene therapy attenuates paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in dorsal root ganglia in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007;21(5):686–698. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.012. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.012]. [PMID: 17174526]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang Z.Z., Li D., Liu C.C., Cui Y., Zhu H.Q., Zhang W.W., Li Y.Y., Xin W.J. CX3CL1-mediated macrophage activation contributed to paclitaxel-induced DRG neuronal apoptosis and painful peripheral neuropathy. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014;40:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.014. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.014]. [PMID: 24681252]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kiya T., Kawamata T., Namiki A., Yamakage M. Role of satellite cell-derived L-serine in the dorsal root ganglion in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2011;174:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.046. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.046]. [PMID: 21118710]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peters C.M., Jimenez-Andrade J.M., Jonas B.M., Sevcik M.A., Koewler N.J., Ghilardi J.R., Wong G.Y., Mantyh P.W. Intravenous paclitaxel administration in the rat induces a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by macrophage infiltration and injury to sensory neurons and their supporting cells. Exp. Neurol. 2007;203(1):42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.022. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2006. 07.022]. [PMID: 17005179]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Watanabe T., Nagase K., Chosa M., Tobinai K. Schwann cell autophagy induced by SAHA, 17-AAG, or clonazepam can reduce bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;103(10):1580–1587. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605954. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605954]. [PMID: 20959823]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zheng H., Xiao W.H., Bennett G.J. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp. Neurol. 2012;238(2):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.023. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08. 023]. [PMID: 22947198]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mao-Ying Q.L., Kavelaars A., Krukowski K., Huo X.J., Zhou W., Price T.J., Cleeland C., Heijnen C.J. The anti-diabetic drug metformin protects against chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100701. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100701]. [PMID: 24955774]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Melemedjian O.K., Yassine H.N., Shy A., Price T.J. Proteomic and functional annotation analysis of injured peripheral nerves reveals ApoE as a protein upregulated by injury that is modulated by metformin treatment. Mol. Pain. 2013;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-9-14. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1744-8069-9-14]. [PMID: 23531341]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor A., Westveld A.H., Szkudlinska M., Guruguri P., Annabi E., Patwardhan A., Price T.J., Yassine H.N. The use of metformin is associated with decreased lumbar radiculopathy pain. J. Pain Res. 2013;6:755–763. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S52205. [PMID: 24357937]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang N.L., Chiang S.H., Hsueh C.H., Liang Y.J., Chen Y.J., Lai L.P. Metformin inhibits TNF-alpha-induced IkappaB kinase phosphorylation, IkappaB-alpha degradation and IL-6 production in endothelial cells through PI3K-dependent AMPK phosphorylation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009;134(2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.010. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.010]. [PMID: 18597869]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Berlo-van de Laar I.R., Vermeij C.G., Doorenbos C.J. Metformin associated lactic acidosis: incidence and clinical correlation with metformin serum concentration measurements. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2011;36(3):376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01192.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j. 1365-2710.2010.01192.x]. [PMID: 21545617]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saadi T., Waterman M., Yassin H., Baruch Y. Metformin-induced mixed hepatocellular and cholestatic hepatic injury: case report and literature review. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2013;6:703–706. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S49657. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S49657]. [PMID: 23983487]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang C.Y., Chen Y.L., Li A.H., Lu J.C., Wang H.L. Minocycline, a microglial inhibitor, blocks spinal CCL2-induced heat hyperalgesia and augmentation of glutamatergic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-11-7]. [PMID: 24405660]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raghavendra V., Tanga F., DeLeo J.A. Inhibition of microglial activation attenuates the development but not existing hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;306(2):624–630. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052407. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.103.052407]. [PMID: 12734393]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boyette-Davis J., Dougherty P.M. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Exp. Neurol. 2011;229(2):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.02.019. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.02.019]. [PMID: 21385581]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pachman D.R., Dockter T., Zekan P.J., Fruth B., Ruddy K.J., Ta L.E., Lafky J.M., Dentchev T., Le-Lindqwister N.A., Sikov W.M., Staff N., Beutler A.S., Loprinzi C.L. A pilot study of minocycline for the prevention of paclitaxel-associated neuropathy: ACCRU study RU221408I. Support. Care Cancer. 2017;25(11):3407–3416. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3760-2. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3760-2]. [PMID: 28551844]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ledeboer A., Sloane E.M., Milligan E.D., Frank M.G., Mahony J.H., Maier S.F., Watkins L.R. Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain. 2005;115(1-2):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.009. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.009]. [PMID: 15836971]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kelly K.J., Sutton T.A., Weathered N., Ray N., Caldwell E.J., Plotkin Z., Dagher P.C. Minocycline inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in a rat model of ischemic renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004;287(4):F760–F766. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00050.2004. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1152/ajprenal.00050.2004]. [PMID: 15172883]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kraus R.L., Pasieczny R., Lariosa-Willingham K., Turner M.S., Jiang A., Trauger J.W. Antioxidant properties of minocycline: neuroprotection in an oxidative stress assay and direct radical-scavenging activity. J. Neurochem. 2005;94(3):819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03219.x. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03219.x]. [PMID: 16033424]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suk K. Minocycline suppresses hypoxic activation of rodent microglia in culture. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;366(2):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.038. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.038]. [PMID: 15276240]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zemlan F.P., Kow L.M., Pfaff D.W. Spinal serotonin (5-HT) receptor subtypes and nociception. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983;226(2):477–485. [PMID: 6308209]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hall F.S., Schwarzbaum J.M., Perona M.T., Templin J.S., Caron M.G., Lesch K.P., Murphy D.L., Uhl G.R. A greater role for the norepinephrine transporter than the serotonin transporter in murine nociception. Neuroscience. 2011;175:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.057. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.057]. [PMID: 21129446]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bellingham G.A., Peng P.W. Duloxetine: a review of its pharmacology and use in chronic pain management. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2010;35(3):294–303. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181df2645. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0b013 e3181df2645]. [PMID: 20921842]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Durand J.P., Deplanque G., Montheil V., Gornet J.M., Scotte F., Mir O., Cessot A., Coriat R., Raymond E., Mitry E., Herait P., Yataghene Y., Goldwasser F. Efficacy of venlafaxine for the prevention and relief of oxaliplatin-induced acute neurotoxicity: results of EFFOX, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(1):200–205. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr045. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1093/annonc/mdr045]. [PMID: 21427067]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith E.M., Pang H., Cirrincione C., Fleishman S., Paskett E.D., Ahles T., Bressler L.R., Fadul C.E., Knox C., Le-Lindqwister N., Gilman P.B., Shapiro C.L. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(13):1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1001/jama.2013.2813]. [PMID: 23549581]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hershman D.L., Lacchetti C., Dworkin R.H., Lavoie Smith E.M., Bleeker J., Cavaletti G., Chauhan C., Gavin P., Lavino A., Lustberg M.B., Paice J., Schneider B., Smith M.L., Smith T., Terstriep S., Wagner-Johnston N., Bak K., Loprinzi C.L. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–1967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914]. [PMID: 24733808]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhao Z., Zhang H.T., Bootzin E., Millan M.J., O’Donnell J.M. Association of changes in norepinephrine and serotonin transporter expression with the long-term behavioral effects of antidepressant drugs. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(6):1467–1481. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.183. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.183]. [PMID: 18923402]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sada H., Egashira N., Ushio S., Kawashiri T., Shirahama M., Oishi R. Repeated administration of amitriptyline reduces oxaliplatin-induced mechanical allodynia in rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;118(4):547–551. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12006sc. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1254/jphs.12006SC]. [PMID: 22466962]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kautio A.L., Haanpää M., Saarto T., Kalso E. Amitriptyline in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic symptoms. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.043. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.043]. [PMID: 17980550]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kautio A.L., Haanpää M., Leminen A., Kalso E., Kautiainen H., Saarto T. Amitriptyline in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic symptoms. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(7):2601–2606. [PMID: 19596934]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gewandter J.S., Mohile S.G., Heckler C.E., Ryan J.L., Kirshner J.J., Flynn P.J., Hopkins J.O., Morrow G.R. A phase III randomized, placebo-controlled study of topical amitriptyline and ketamine for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a University of Rochester CCOP study of 462 cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer. 2014;22(7):1807–1814. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2158-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s00520-014-2158-7]. [PMID: 24531792]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hammack J.E., Michalak J.C., Loprinzi C.L., Sloan J.A., Novotny P.J., Soori G.S., Tirona M.T., Rowland K.M., Jr, Stella P.J., Johnson J.A. Phase III evaluation of nortriptyline for alleviation of symptoms of cis-platinum-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2002;98(1-2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00047-7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00047-7]. [PMID: 12098632]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bet P.M., Hugtenburg J.G., Penninx B.W., Hoogendijk W.J. Side effects of antidepressants during long-term use in a naturalistic setting. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1443–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.05.001. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.05.001]. [PMID: 23726508]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Di Cesare Mannelli L., Zanardelli M., Failli P., Ghelardini C. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: oxidative stress as pathological mechanism. Protective effect of silibinin. J. Pain. 2012;13(3):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.009]. [PMID: 22325298]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Doyle T., Chen Z., Muscoli C., Bryant L., Esposito E., Cuzzocrea S., Dagostino C., Ryerse J., Rausaria S., Kamadulski A., Neumann W.L., Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6149–6160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012]. [PMID: 22553021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Florea A.M., Büsselberg D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3(1):1351–1371. doi: 10.3390/cancers3011351. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/cancers3011351]. [PMID: 24212665]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Joseph E.K., Chen X., Bogen O., Levine J.D. Oxaliplatin acts on IB4-positive nociceptors to induce an oxidative stress-dependent acute painful peripheral neuropathy. J. Pain. 2008;9(5):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.335. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.335]. [PMID: 18359667]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sawicka E., Długosz A., Rembacz K.P., Guzik A. The effects of coenzyme Q10 and baicalin in cisplatin-induced lipid peroxidation and nitrosative stress. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2013;70(6):977–985. [PMID: 24383321]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Areti A., Yerra V.G., Naidu V., Kumar A. Oxidative stress and nerve damage: role in chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy. Redox Biol. 2014;2:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.006. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.redox.2014.01.006]. [PMID: 24494204]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Majsterek I., Gloc E., Blasiak J., Reiter R.J. A comparison of the action of amifostine and melatonin on DNA-damaging effects and apoptosis induced by idarubicin in normal and cancer cells. J. Pineal Res. 2005;38(4):254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00197.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00197.x]. [PMID: 15813902]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gurney J.G., Bass J.K., Onar-Thomas A., Huang J., Chintagumpala M., Bouffet E., Hassall T., Gururangan S., Heath J.A., Kellie S., Cohn R., Fisher M.J., Panandiker A.P., Merchant T.E., Srinivasan A., Wetmore C., Qaddoumi I., Stewart C.F., Armstrong G.T., Broniscer A., Gajjar A. Evaluation of amifostine for protection against cisplatin-induced serious hearing loss in children treated for average-risk or high-risk medulloblastoma. Neuro-oncol. 2014;16(6):848–855. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not241. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/ not241]. [PMID: 24414535]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gallegos-Castorena S., Martínez-Avalos A., Mohar-Betancourt A., Guerrero-Avendaño G., Zapata-Tarrés M., Medina-Sansón A. Toxicity prevention with amifostine in pediatric osteosarcoma patients treated with cisplatin and doxorubicin. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2007;24(6):403–408. doi: 10.1080/08880010701451244. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 08880010701451244]. [PMID: 17710657]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hilpert F., Stähle A., Tomé O., Burges A., Rossner D., Späthe K., Heilmann V., Richter B., du Bois A. Neuroprotection with amifostine in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer with carboplatin/paclitaxel-based chemotherapy--a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II study from the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologoie (AGO) Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Support. Care Cancer. 2005;13(10):797–805. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0782-y. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0782-y]. [PMID: 16025262]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lorusso D., Ferrandina G., Greggi S., Gadducci A., Pignata S., Tateo S., Biamonte R., Manzione L., Di Vagno G., Ferrau’ F., Scambia G. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of amifostine as cytoprotectant in first-line chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2003;14(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg301. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ annonc/mdg301]. [PMID: 12853351]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kemp G., Rose P., Lurain J., Berman M., Manetta A., Roullet B., Homesley H., Belpomme D., Glick J. Amifostine pretreatment for protection against cyclophosphamide-induced and cisplatin-induced toxicities: results of a randomized control trial in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14(7):2101–2112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2101. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2101]. [PMID: 8683243]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Duval M., Daniel S.J. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of amifostine in the prevention of cisplatin ototoxicity. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;41(5):309–315. [PMID: 23092832]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yri O.E., Vig J., Hegstad E., Hovde O., Pignon I., Jynge P. Mangafodipir as a cytoprotective adjunct to chemotherapy--a case report. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(4):633–635. doi: 10.1080/02841860802680427. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1080/02841860802680427]. [PMID: 19169914]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Karlsson J.O., Adolfsson K., Thelin B., Jynge P., Andersson R.G., Falkmer U.G. First clinical experience with the magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent and superoxide dismutase mimetic mangafodipir as an adjunct in cancer chemotherapy-a translational study. Transl. Oncol. 2012;5(1):32–38. doi: 10.1593/tlo.11277. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1593/tlo.11277]. [PMID: 22348174]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Coriat R., Alexandre J., Nicco C., Quinquis L., Benoit E., Chéreau C., Lemaréchal H., Mir O., Borderie D., Tréluyer J.M., Weill B., Coste J., Goldwasser F., Batteux F. Treatment of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy by intravenous mangafodipir. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(1):262–272. doi: 10.1172/JCI68730. [http://dx.doi.org/10. 1172/JCI68730]. [PMID: 24355920]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Karlsson J.O., Kurz T., Flechsig S., Näsström J., Andersson R.G. Superior therapeutic index of calmangafodipir in comparison to mangafodipir as a chemotherapy adjunct. Transl. Oncol. 2012;5(6):492–502. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12238. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1593/tlo.12238]. [PMID: 23323161]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chaparro L.E., Wiffen P.J., Moore R.A., Gilron I. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;7(7):CD008943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008943.pub2. [PMID: 22786518]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]