Abstract

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by distressing thoughts and repetitive behaviors that are interfering, time-consuming, and difficult to control. Although OCD was once thought to be untreatable, the last few decades have seen great success in reducing symptoms with exposure and response prevention (ERP), which is now considered to be the first-line psychotherapy for the disorder. Despite these significant therapeutic advances, there remain a number of challenges in treating OCD. In this review, we will describe the theoretical underpinnings and elements of ERP, examine the evidence for its effectiveness, and discuss new directions for enhancing it as a therapy for OCD.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure with response prevention, obsessive-compulsive disorder, treatment efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Considered one of the most debilitating psychiatric illnesses,[1,2] obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by distressing thoughts and repetitive behaviors that are interfering, time-consuming, and difficult to control.[3] Historically, OCD was thought to be untreatable, as people with the disorder did not respond that well to traditional psychodynamic psychotherapy, medication, or available behavioral interventions such as systematic desensitization or aversion therapy.[4] The first significant nonpharmacological advance in treatment occurred after Meyer[5] reported that patients’ OCD symptoms improved when they were exposed to feared stimuli while, crucially, refraining from performing compulsions. Subsequent studies indicated that this method of exposure and response prevention (ERP) was effective in both a hospital and outpatient setting and that a majority of patients experienced significant improvement which was maintained for many up to two years post-treatment.[6,7,8] Since then, ERP has become the first-line psychotherapeutic treatment for OCD and will, therefore, be the focus of the current paper. In this review, we will describe the theoretical underpinnings and elements of ERP, examine the evidence for its effectiveness, and discuss new directions for enhancing it as a therapy for OCD.

ELEMENTS OF EXPOSURE AND RESPONSE PREVENTION

Mowrer's[9] two-factor theory of fear and avoidance provided an influential framework for understanding the etiology of OCD that inspired the development of behavioral treatments for the disorder, including ERP. Specifically, Mowrer asserted that individuals experience anticipatory anxiety in the presence of environmental stimuli that are associated with painful or aversive experiences through classical conditioning. Subsequent avoidance of the feared stimuli serves to alleviate people's anxiety, which in turn reinforces the avoidant behavior through operant conditioning. Similarly, individuals with OCD experience anxiety-provoking obsessions that are triggered by various situations and subsequently perform compulsions or engage in avoidance behaviors to decrease the anxiety associated with these thoughts. Paradoxically, these ritual and avoidance behaviors reinforce individuals’ fear and strengthen both obsessions and compulsions. ERP aims to break this cycle of symptoms by eliminating rituals and avoidance, thereby teaching patients how to tolerate distress without engaging in counterproductive behaviors and providing “corrective information” that challenges people's existing fear response.[4]

ERP can be conducted at varying levels of intensity, including outpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment settings, depending on the severity of the patients’ symptoms. Irrespective of the symptom severity, however, ERP typically shares certain elements across settings.[4] First, there is an assessment and treatment planning phase during which the clinician provides psychoeducation about OCD and its treatment and collects information about the patient's symptoms. The patient and clinician work together to identify external (situations, objects, people, etc.) and internal (thoughts and physiological reactions) stimuli that trigger the person's obsessive thoughts and subsequent distress. Importantly, they also catalog the specific content of the person's obsessions and compulsions, discuss the functional relationship between the two, and identify the feared outcome if the rituals are not performed. For example, one patient might repeatedly wash his hands to disinfect them, thereby preventing a feared outcome of contracting an illness and dying. Another patient, however, might wash her hands because she is disgusted by the physical sensation of having residue on her hands and will, therefore, keep washing them until they “feel right.” The patient and clinician then work collaboratively to rank different situations in order from least to most distressing (as measured by subjective units of distress or SUDs), which results in a fear hierarchy.

Over the subsequent treatment sessions, the clinician coaches the patient as he or she repeatedly confronts the situations on his or her fear hierarchy while refraining from engaging in compulsions. For example, a man who has a fear of contracting an illness from unclean surfaces might hold his hands on various bathroom surfaces for a prolonged period of time, but not wash his hands afterward. The patients may also engage in imaginal exposures during which they envision their feared outcome triggered by their obsessive thoughts (e.g., pushing someone into oncoming traffic and then being sent to prison). By practicing both in vivo and imaginal exposures, the patients learn that the consequences they fear do not occur, as well as how to tolerate distress and uncertainty without engaging in compulsions.[4] Following each in-session exposure, the therapist and patient engage in post-exposure processing to review the patient's experience and how his or her expectations were violated and what he or she learned. The patients are also asked to practice exposures on their own for homework and to attempt to eliminate all rituals in their day-to-day life. As patients habituate to various scenarios, they then gradually work their way up the fear hierarchy to confront increasingly distressing situations. Typically, a course of ERP will conclude with relapse prevention planning.

EFFICACY

Since ERP was recognized as a viable treatment for OCD, a large body of literature has supported its efficacy. Early studies demonstrated its superiority in reducing patients’ OCD symptoms relative to relaxation therapy, anxiety management, or a wait-list condition.[10,11,12,13,14] Subsequent reports have similarly pointed to its effectiveness across multiple countries, treatment settings, and intensity.[11,12,13,14,15] Indeed, a meta-analysis by Eddy et al.[16] indicated that approximately two-thirds of patients who received ERP experienced improvement in symptoms, and approximately one-third of patients were considered to be recovered. Moreover, although the majority of patients treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (without ERP specifically) or cognitive therapy also experienced a reduction in symptoms post-treatment, ERP outperformed the other treatments. Specifically, there was a slightly stronger effect size for ERP, and it resulted in lower OCD severity scores post-treatment relative to the other two modalities.[17]

Importantly, research indicates that the treatment is effective not only with highly controlled study samples of OCD that are not necessarily representative of the general clinical population but also with less restricted samples with comorbidities and complicated treatment histories and that are concurrently taking medication.[11,18] That patients in a representative outpatient treatment setting experienced significant symptom improvement after a course of ERP speaks to the treatment's generalizability. A review by Storch et al.[15] provides further support for the treatment's utility in a variety of settings (e.g., home vs. office), delivered in different intensities (e.g., weekly vs. intensive treatment), and with pediatric and adolescent populations. Moreover, ERP has also been shown to lead not only to symptom reduction but also to a decrease in sleep disturbances and improved quality of life more generally.[15,19,20]

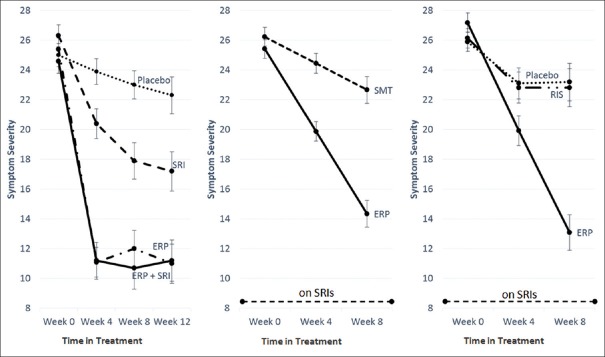

Treatment studies have also examined the efficacy of ERP relative to and in combination with medication. A review of four studies indicated that medication neither enhanced nor impeded treatment with ERP.[21] That is, individuals taking a combination of medication and ERP had similar outcomes to individuals in ERP alone but improved more than individuals on medication alone. In a subsequent study examining the combined effects of ERP with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (the pharmacological frontline treatment for OCD), Foa et al.[22] randomized OCD participants into one of four treatment conditions as follows: ERP only, clomipramine only, ERP plus clomipramine, and placebo. At the end of 12 weeks, participants treated with ERP or a combination of ERP plus medication showed a greater decrease in symptoms relative to those treated with clomipramine alone [Figure 1, left panel]. Moreover, those in the ERP plus medication condition did not differ in post-treatment symptom severity from those treated with ERP alone, indicating that medication did not bolster the efficacy of ERP.[7]

Figure 1.

Effectiveness of exposure and response prevention versus other treatments. SRI – Serotonin reuptake inhibitor; ERP – Exposure and response prevention; SMT – Stress management therapy; RIS – Risperidone; symptom severity was assessed with the Yale–Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS); error bars – Standard error

More recent studies have similarly tested the effectiveness of ERP as an augmentation approach for individuals who benefit from serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) but continue to suffer from clinically significant OCD symptoms. Simpson et al.[23] found that patients on a stable dose of SRIs experienced greater symptom reduction after additional treatment with 17 weeks of ERP compared to those who received augmentation with stress management training [Figure 1, center panel]. A similar pattern of findings emerged when comparing augmentation with ERP to that with risperidone. Specifically, individuals taking SRIs had lower OCD severity scores immediately[24] and 6 months[25] following additional treatment with ERP than those who had additional treatment with risperidone or placebo [Figure 1, right panel]. The OCD severity of groups who received risperidone or placebo did not significantly differ from one another post-treatment.

Although the current guidelines recommend ERP as the first-line treatment for OCD, only about half of the patients who receive it will reach complete symptom remission.[26] There are a number of factors that are associated with poor response, including lack of adherence to treatment, poor insight, comorbid depression, and OCD severity (for a review of treatment-resistance Middleton, Wheaton, Kayser, & Simpson (2019)[27]). Approximately 20–30% of patients drop out of ERP prematurely,[11] perhaps unsurprising given the challenging and time-consuming nature of the treatment. Moreover, there is variation in the extent to which patients adhere to treatment recommendations even if they do complete a full course of ERP. One study found that low adherence to completing exposures assigned between ERP sessions predicted higher symptom severity post-treatment.[28] Similarly, clinicians are susceptible to making errors in how they deliver the treatment to patients, which likewise inhibits its effectiveness.[29] Given the strong association of adherence to treatment outcome, future interventions that increase patient and therapist fidelity to ERP would be worthwhile.

Research investigating the relationship between outcomes and other factors such as insight and depression and symptom severity has yielded mixed results. Whereas some studies indicate that individuals with poor insight have a lower response to ERP than do those with good or fair insight, other studies fail to find an association between the two.[27] Discrepant findings may be due to a restricted range of insight in OCD study samples. That is, people with very low insight may be less likely to seek treatment for symptoms than do those with better insight.

Similarly, some studies have found that people suffering from severe symptoms and those with comorbid depression have worse treatment outcomes than people with no or mild depression and those with less severe OCD. However, a meta-analysis by Olatunji et al.[30] reported no differences in treatment outcome effect sizes for a range of moderators, including depression and symptom severity. One explanation for these inconsistent findings is that these factors may impact treatment adherence rather than outcomes more directly. For example, individuals with poor insight (e.g., a man who believes that his feared outcomes are realistic or that his rituals will prevent negative events) may be less likely to adhere to treatment and engage in exposures than someone who recognizes her fears and behaviors as excessive and unrealistic.

MECHANISMS OF CHANGE

Researchers have proposed different theories of how ERP works or its mechanism of action. Early cognitive models of OCD proposed that people develop the disorder when they misinterpret the significance of normal, intrusive thoughts that the majority of individuals will experience at some point in their lives.[31,32] Dysfunctional thoughts such as an inflated sense of responsibility for preventing harm to oneself and others, overestimation of threat, intolerance of uncertainty, a need for perfectionism, and over-importance of and need to control thoughts have also been identified as potential etiological and maintaining factors for OCD, as they cause people to interpret their intrusive thoughts as significant and potentially dangerous.[33] According to this perspective then, ERP works by disconfirming people's distorted beliefs through exposures. For example, if a woman overestimates the likelihood of danger, then repeated exposures to feared situations in which she tests this belief would presumably lead to less-biased thinking, thereby resulting in decreased OCD symptoms. Since its inception, the cognitive theory of OCD has received empirical support,[34] including from studies showing that decrements in dysfunctional thinking mediate symptom improvement post-treatment.[35] However, other studies have found that OCD severity predicts changes in dysfunctional thinking, thus calling into question the causal direction of change.[36] Specifically, Olatunji et al.[37] found that changes in OCD symptoms preceded altered beliefs about inflated responsibility rather than the other way around.

A behavioral perspective asserts that ERP works by breaking the conditioned response between obsessions and compulsions.[5] According to this model, compulsions temporarily alleviate people's anxiety that obsessive thoughts trigger. The decrease in distress strengthens the rituals and conditions people to continue using them when confronted with subsequent intrusive thoughts. On the other hand, when individuals confront triggering situations while simultaneously refraining from engaging in rituals, their distress decreases naturally in the absence of their feared outcome. With repeated exposure, the fear response is eventually extinguished and OCD symptoms subside.

According to emotion processing theory, fear and other emotions are stored in memory structures that contain information about stimuli that elicit the emotional response, as well as the response itself.[7] This theory states that exposure therapy provides information that is contradictory to the existing fear structure when patients’ dreaded outcomes do not occur. Consequently, individuals form new, more realistic memory structures that do not include a pathological fear response. Repeated practice confronting distressing situations strengthens the activation of this competing structure, thereby weakening the occurrence of the fear response.

More recently, researchers have proposed that inhibitory learning is central to extinction through exposure therapy.[38,39] Specifically, this theory purports that the initial conditioned association between the stimulus and the unconditioned fear response does not disappear, but rather that a new association is learned that competes with the former response. Craske et al. explain that “…after extinction, the [conditioned stimulus] possesses two meanings; its original excitatory meaning (conditioned stimulus–unconditioned stimulus) as well as an additional inhibitory meaning (conditioned stimulus–no unconditioned stimulus)” (p. 11-12).[38] Therefore, the newly formed association inhibits the memory of the original excitatory response with repeated practice, but does not prevent it from being reactivated at some point in the future, thus underscoring the importance of continued exposure to once-feared stimuli.

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the neural mechanisms underlying the etiology and treatment of psychiatric disorders, including OCD. For example, using a neurobiological framework, Gillan and Robbins[40] propose that compulsions are the result of excessive habit formation and that obsessions develop when the sufferer makes inferences about his or her behavior (e.g., “I check the knobs on the stove so I must be afraid of accidentally starting a fire”). Therefore, when refraining from engaging in compulsions during ERP, the patients are learning to break the habitual ritualistic behavior, which, in turn, reduces obsessions. A number of studies examining neural mechanisms of change have identified differences in the brain from pre- to post-treatment with psychotherapy.[41,42,43] However, researchers have yet to identify how these changes are directly related to processes that then lead to clinical improvement.[44]

NEW DIRECTIONS

Despite the success of ERP in treating OCD, there is room for improvement. As noted above, many people drop out of treatment prematurely and a substantial number of those who do complete a course of ERP do not achieve a clinically significant reduction of symptoms. Some especially notable challenges in treating OCD include addressing people's limited access to evidence-based treatments, finding novel ways to improve upon ERP to increase its efficacy, and integrating biological and psychological frameworks to fine-tune treatment.

Access to care

There are numerous barriers to treatment, including high costs of care, stigma surrounding mental health issues, and lack of access to clinicians who are trained in evidence-based practices.[45,46,47] One solution to improve access to care is the development of an internet-based ERP program that individuals can use to guide themselves through treatment with the support of a therapist through e-mail, phone, or the online treatment platform.[48,49] Results from studies implementing these internet programs are promising; they have demonstrated not only the feasibility, but also the efficacy, of delivering ERP online. Specifically, individuals who completed these online programs experienced a clinically significant decrease in OCD symptoms[47,49,50] which were maintained at follow-up.[49,51] Given the growing ubiquity of internet access and cellular phones, continuing to develop programs that increase the dissemination of ERP is worthwhile.

Enhancing exposure and response prevention

Technological advances have been used not only to disseminate ERP but also in an attempt to improve its effects. Najmi and Amir (2010) recruited individuals with subclinical OCD contamination concerns to complete attention bias modification (ABM) before a subsequent behavioral approach task. In the attention task, half of the participants were placed in an active condition, in which they were trained to shift their attention away from “threatening” words (i.e., related to contamination), whereas the other half in the nonactive condition did not receive such training. The authors found that relative to those in the nonactive condition, individuals in the active ABM group were less avoidant of contaminated objects during a subsequent behavioral approach task. It is possible, then, that reducing attention to threat may diminish avoidance behaviors, thus making people more willing to engage in exposures.[52] However, a subsequent study using a clinical population found that ABM alone did not reduce OCD symptoms, thus suggesting that it may be more effective in addition to ERP rather than in place of it.[53]

Virtual reality is similarly being studied as a way to enhance exposure therapy for a number of disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety disorders.[54,55] Although it has not been tested extensively with OCD patients, a preliminary study demonstrated its effectiveness in triggering and measuring anxiety in people through a virtual reality platform.[56] Virtual reality may be especially effective in designing exposures to situations or stimuli that are impossible to reproduce in vivo and are otherwise left to imaginal exposures.

Craske et al.[39] have proposed a number of ways to enhance extinction learning based on the aforementioned inhibitory learning perspective. This orientation emphasizes that the overarching goal of exposure should be distress tolerance rather than fear reduction. Accordingly, the authors outline ideas for how to translate this approach into clinical practice with exposure therapy, such as maximizing the extent to which people's expectancies of feared outcomes are violated, pairing a previously extinguished cue with a new conditioned stimulus, removing safety signals, and practicing exposures in multiple contexts (e.g., with different people, settings, times of day, etc.[39]). By homing in on processes thought to underlie mechanisms of change, it may be possible to maximize the benefits of extinction learning, thus leading to greater improvement in psychopathological symptoms.

Finally, some studies have investigated the advantage of enhancing ERP with medication implicated in facilitated extinction learning. Specifically, research demonstrated that, relative to those given a placebo pill, patients taking d-cycloserine before engaging in exposure therapy experienced a faster rate of symptom improvement in the first few weeks of receiving ERP.[57] However, there were no group differences in symptom improvement by the end of treatment, suggesting that the drug's utility lies primarily in speeding up treatment response.[58]

Integrating biological and psychological approaches

Investigations on the biological underpinnings of OCD have identified genetic factors and abnormalities in neurocircuitry that are associated with the disorder.[59] However, very little research has bridged the gap between biological and psychological approaches in psychopathology, and consequently, there is a dearth of information regarding how information about genetics or neurobiology might meaningfully improve our treatment of psychiatric disorders. Notable exceptions are recent studies that have identified gene variants of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) that mediate outcome to psychotherapeutic treatment. The BDNF gene codes for a protein that promotes neuron development and growth and helps to regulate the neurophysiological response to stress, making it especially relevant to better understanding mood and anxiety disorders.[60] A series of studies have reported that variants of the BDNF gene are associated with improved treatment outcomes with medication for schizophrenia,[61] with dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder,[62] and, most recently, with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for children with anxiety disorders.[63]

FAAH, on the other hand, is a gene in the endocannabinoid system, which plays an important role in regulating anxiety and facilitating fear extinction, which is central to ERP as noted above.[60] Dincheva et al.[64] found an association between a variant of FAAH and accelerated fear extinction in late stages of an extinction learning task as well as reduced levels of anxiety. This finding suggests that it may be possible to identify individuals who are more responsive to treatments that entail extinction learning. However, a more recent study in children with anxiety disorders found only minimal evidence of a correlation between gene variants in the endocannabinoid system and response to CBT.[60] The authors assert that though further research on the endocannabinoid system specifically and on “therapygenetics” (p. 153) more generally is worthwhile, we are unlikely to identify single gene variants that predict response to psychological treatments.

Finally, several surgical and noninvasive neurological interventions are available to patients who have not had success with psychotherapy or medication. Neuromodulating methods such as transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), as well as surgical procedures such as deep brain stimulation, work to decrease symptoms by targeting underlying neurocircuitry implicated in the pathophysiology of OCD.[65,66,67,68] Few studies have examined the effect of augmenting therapy with these methods and fewer still specifically for the treatment of OCD. However, there are encouraging reports that indicate some benefit of combining tDCS with CBT for treatment-resistant depression,[69] suggesting it might likewise be useful as an augmentation for the treatment of other disorders. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that combining DBS with CBT (which included ERP) resulted in a reduction of OCD symptoms in a treatment-refractory sample.[70] Indeed, DBS has been shown to enhance fear extinction,[71,72] thus highlighting its potential usefulness when paired with a treatment such as ERP. Finally, in their meta-analysis, Berlim et al.[73] found that repetitive TMS was an effective augmentation for medication when treating refractory OCD. None of the studies included in the meta-analysis examined TMS in combination with ERP; hence, whether or not they would be beneficial when used together merits further study.

Morphometric studies have revealed that the thickness[74] and volume[75] of different brain regions in individuals with OCD are correlated with treatment outcomes with exposure therapy. What remains to be seen, however, is if variation in neurocircuitry, such as genetic variants, can ultimately predict differential response to treatment and whether brain imaging findings at baseline can be usefully applied to individual patients. Since OCD is caused by a complex interaction among genetic, neurocircuitry, environmental, and developmental factors, it is essential that researchers continue to integrate psychological and biological approaches to more effectively treat this debilitating disease.

ALTERNATIVES TO EXPOSURE AND RESPONSE PREVENTION

Although ERP has been identified as a (nonpharmacological) gold standard treatment for OCD, other psychotherapeutic treatments have been developed and their efficacy empirically supported (see Manjula and Sudhir review in this issue for more details).

Two that have been found to be effective in treating OCD include cognitive therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Despite the fact that ERP, cognitive therapy, and ACT are considered distinct treatments grounded in different theoretical perspectives, they share common elements that perhaps make them more similar than they seem on the surface.[76] Moreover, though some data support their efficacy as standalone treatments for OCD,[77,78] some argue that integrating components of cognitive therapy (Rector, in press) or ACT into ERP may have added benefits.[79] Future research in this area is needed.

CONCLUSION

ERP is a highly efficacious treatment for many people who suffer from OCD. Although there are a number of explanations for its mechanism of action, it is still unclear exactly how it works or why some people respond to it whereas others do not.[44] Although up to half of people will achieve minimal symptoms after acute treatment with ERP as either a monotherapy[22] or in combination with medication,[23,24] many who undergo the therapy will remain symptomatic and some will not benefit at all. These shortcomings underscore the need to continue to improve upon ERP by enhancing it with new methods, incorporating genetic and neurobiological approaches, and developing alternative treatments.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baxter AJ, Vos T, Scott KM, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2363–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association AP. Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TB. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Therapist Guide. USA: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer V. Modification of expectations in cases with obsessional rituals. Behav Res Ther. 1966;4:273–80. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(66)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foa EB, Goldstein A. Continuous exposure and complete response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive neurosis. Behav Ther. 1978;9:821–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foa EB, McLean CP. The efficacy of exposure therapy for anxiety-related disorders and its underlying mechanisms: The case of OCD and PTSD. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks IM, Hodgson R, Rachman S. Treatment of chronic obsessive-compulsive neurosis by in-vivo exposure. A two-year follow-up and issues in treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;127:349–64. doi: 10.1192/bjp.127.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mowrer OH. A stimulus-response analysis of anxiety and its role as a reinforcing agent. Psychol Rev. 1939;46:553–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A quantitative review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:44–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramowitz JS. The psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:407–16. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fals-Stewart W, Marks AP, Schafer J. A comparison of behavioral group therapy and individual behavior therapy in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:189–93. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeston MH, Ladouceur R, Gagnon F, Thibodeau N, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive thoughts: A controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:405–13. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay M, Crino R, Andrews G. Controlled trial of exposure and response prevention in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:135–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storch EA, Mariaskin A, Murphy TK. Psychotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:296–301. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:1011–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Deacon BJ. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: A review of meta-analytic findings. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:557–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Levitt JT, Foa EB. Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diefenbach GJ, Abramowitz JS, Norberg MM, Tolin DF. Changes in quality of life following cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:3060–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Lack CW, Geffken GR, Jacob ML, Goodman WK, et al. Sleep-related problems in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:877–85. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foa EB, Franklin ME, Moser J. Context in the clinic: How well do cognitive-behavioral therapies and medications work in combination? Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:987–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Ledley DR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:621–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, Maher MJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1190–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foa EB, Simpson HB, Rosenfield D, Liebowitz MR, Cahill SP, Huppert JD, et al. Six-month outcomes from a randomized trial augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors with exposure and response prevention or risperidone in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:440–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson HB, Huppert JD, Petkova E, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR. Response versus remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:269–76. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Middleton R, Wheaton MG, Kayser R, Simpson HB. Treatment resistance in obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Kim YK, editor. Treatment Resistance in Psychiatry. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson HB, Marcus SM, Zuckoff A, Franklin M, Foa EB. Patient adherence to cognitive-behavioral therapy predicts long-term outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1265–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12l07879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillihan SJ, Williams MT, Malcoun E, Yadin E, Foa EB. Common pitfalls in exposure and response prevention (EX/RP) for OCD. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2012;1:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rachman S. A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salkovskis PM. Obsessional-compulsive problems: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23:571–83. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Group OC. Cognitive assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:667–81. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hezel DM, McNally RJ. A theoretical review of cognitive biases and deficits in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychol. 2016;121:221–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilhelm S, Berman NC, Keshaviah A, Schwartz RA, Steketee G. Mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: Role of maladaptive beliefs and schemas. Behav Res Ther. 2015;65:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woody SR, Whittal ML, McLean PD. Mechanisms of symptom reduction in treatment for obsessions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:653–64. doi: 10.1037/a0024827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olatunji BO, Rosenfield D, Tart CD, Cottraux J, Powers MB, Smits JA, et al. Behavioral versus cognitive treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: An examination of outcome and mediators of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:415–28. doi: 10.1037/a0031865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A, et al. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B. Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillan CM, Robbins TW. Goal-directed learning and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:pii: 20130475. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linden DE. How psychotherapy changes the brain – The contribution of functional neuroimaging. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:528–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porto PR, Oliveira L, Mari J, Volchan E, Figueira I, Ventura P, et al. Does cognitive behavioral therapy change the brain? A systematic review of neuroimaging in anxiety disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21:114–25. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxena S, Gorbis E, O’Neill J, Baker SK, Mandelkern MA, Maidment KM, et al. Rapid effects of brief intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy on brain glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:197–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheaton MG, Schwartz MR, Pascucci O, Simpson BH. Cognitive-behavior therapy outcomes for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Exposure and response prevention. Psychiatr Ann. 2015;45:303–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blanco C, Olfson M, Stein DJ, Simpson HB, Gameroff MJ, Narrow WH, et al. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder by U.S. Psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:946–51. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, Timpano KR, Jenike M, Wilhelm S, et al. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:470–5. doi: 10.1002/da.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel SR, Wheaton MG, Andersson E, Rück C, Schmidt AB, La Lima CN, et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder in new york. Behav Ther. 2018;49:631–41. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Kaldo V, Paxling B, Andersson G, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: A pilot study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wootton BM, Dear BF, Johnston L, Terides MD, Titov N. Self-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) for obsessive-compulsive disorder: 12 month follow-up. Internet Interv. 2015;2:243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersson E, Enander J, Andrén P, Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Hursti T, et al. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2193–203. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersson E, Steneby S, Karlsson K, Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Enander J, et al. Long-term efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder with or without booster: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2877–87. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Najmi S, Amir N. The effect of attention training on a behavioral test of contamination fears in individuals with subclinical obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:136–42. doi: 10.1037/a0017549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moritz S, Wess N, Treszl A, Jelinek A. The attention training technique as an attempt to decrease intrusive thoughts in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): From cognitive theory to practice and back. J Contemp Psychother. 2011;41:135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powers MB, Emmelkamp PM. Virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:561–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reger GM, Gahm GA. Virtual reality exposure therapy for active duty soldiers. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:940–6. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim K, Kim CH, Cha KR, Park J, Han K, Kim YK, et al. Anxiety provocation and measurement using virtual reality in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:637–41. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilhelm S, Buhlmann U, Tolin DF, Meunier SA, Pearlson GD, Reese HE, et al. Augmentation of behavior therapy with D-cycloserine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:335–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chasson GS, Buhlmann U, Tolin DF, Rao SR, Reese HE, Rowley T, et al. Need for speed: Evaluating slopes of OCD recovery in behavior therapy enhanced with d-cycloserine. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pauls DL, Abramovitch A, Rauch SL, Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: An integrative genetic and neurobiological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:410–24. doi: 10.1038/nrn3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lester KJ, Coleman JR, Roberts S, Keers R, Breen G, Bögels S, et al. Genetic variation in the endocannabinoid system and response to cognitive behavior therapy for child anxiety disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174:144–55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krebs MO, Guillin O, Bourdell MC, Schwartz JC, Olie JP, Poirier MF, et al. Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene variants association with age at onset and therapeutic response in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:558–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perroud N, Salzmann A, Prada P, Nicastro R, Hoeppli ME, Furrer S, et al. Response to psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder and methylation status of the BDNF gene. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e207. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lester KJ, Hudson JL, Tropeano M, Creswell C, Collier DA, Farmer A, et al. Neurotrophic gene polymorphisms and response to psychological therapy. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e108. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dincheva I, Drysdale AT, Hartley CA, Johnson DC, Jing D, King EC, et al. FAAH genetic variation enhances fronto-amygdala function in mouse and human. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6395. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brunelin J, Mondino M, Bation R, Palm U, Saoud M, Poulet E, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. Brain Sci. 2018;8:pii: E37. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, Rezai AR, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2384–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaafari N, Rachid F, Rotge JY, Polosan M, El-Hage W, Belin D, et al. Safety and efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:164–77. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.575177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Senço NM, Huang Y, D’Urso G, Parra LC, Bikson M, Mantovani A, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Emerging clinical evidence and considerations for optimal montage of electrodes. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2015;12:381–91. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2015.1037832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.D’Urso G, Mantovani A, Micillo M, Priori A, Muscettola G. Transcranial direct current stimulation and cognitive-behavioral therapy: Evidence of a synergistic effect in treatment-resistant depression. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:465–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mantione M, Nieman DH, Figee M, Denys D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy augments the effects of deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3515–22. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arumugham SS, Reddy YC. Commonly asked questions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14:151–63. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2014.874287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Do Monte FH, Quirk GJ. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral striatum enhances extinction of conditioned fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200782109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Berlim MT, Neufeld NH, Van den Eynde F. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): An exploratory meta-analysis of randomized and sham-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fullana MA, Cardoner N, Alonso P, Subirà M, López-Solà C, Pujol J, et al. Brain regions related to fear extinction in obsessive-compulsive disorder and its relation to exposure therapy outcome: A morphometric study. Psychol Med. 2014;44:845–56. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoexter MQ, Dougherty DD, Shavitt RG, D’Alcante CC, Duran FL, Lopes AC, et al. Differential prefrontal gray matter correlates of treatment response to fluoxetine or cognitive-behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:569–80. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tolin DF. Alphabet soup: ERP, CT, and ACT for OCD. Cogn Behav Pract. 2009;16:40–8. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bluett EJ, Homan KJ, Morrison KL, Levin ME, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety and OCD spectrum disorders: An empirical review. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:612–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilhelm S, Steketee G, Fama JM, Buhlmann U, Teachman BA, Golan E, et al. Modular cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A wait-list controlled trial. J Cogn Psychother. 2009;23:294–305. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Twohig MP, Abramowitz JS, Bluett EJ, Fabricant LE, Jacoby RJ, Morrison KL, et al. Exposure therapy for OCD from an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) framework. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2015;6:167–73. [Google Scholar]