Abstract

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 1%–3% of children worldwide and has a profound impact on quality of life for patients and families. Although our understanding of the underlying etiology remains limited, data from neuroimaging and genetic studies as well as the efficacy of serotonergic medications suggest the disorder is associated with the fundamental alterations in the function of cortico-striato-thalamocortical circuits. Significant delays to diagnosis are common, ultimately leading to more severe functional impairment with long-term developmental consequences. The clinical assessment requires a detailed history of specific OCD symptoms as well as psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Standardized assessment tools may aid in evaluating and tracking symptom severity and both individual and family functioning. In the majority of children, an interdisciplinary approach that combines cognitive behavioral therapy with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor leads to meaningful symptom improvement, although some patients experience a chronic, episodic course. There are limited data to guide the management of treatment-refractory illness in children, although atypical antipsychotics and glutamate-modulating agents may be used cautiously as augmenting agents. This review outlines a clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of OCD, highlighting associated challenges, and limitations to our current knowledge.

Keywords: Adolescents, children, diagnosis, obsessive–compulsive disorder, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common neuropsychiatric condition identified by the World Health Organization as one of the 10 most disabling medical illnesses.[1] The disorder is characterized by recurrent, persistent, and unwanted intrusive thoughts or images (obsessions) and/or repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) performed to limit distress.[2] Childhood-onset OCD (CO-OCD) appears to represent a specific subtype with unique epidemiological, etiological, and clinical characteristics.[3,4] Compared to adult-onset OCD, it is linked with higher familial and genetic risk;[5] higher prevalence of comorbid tic, ADHD, and anxiety disorders;[6] and potentially higher persistence rates.[7] On average, diagnosis is delayed by 3 years after symptom onset;[8] treatment delays are therefore common and may be associated with poorer outcomes. Contributing factors include limited awareness of the disorder among both clinicians and patients, shame or embarrassment associated with symptoms, lack of insight, and accommodation of compulsive behaviors by family.[9] Untreated symptoms typically follow a chronic, episodic course associated with significant functional impairment in addition to increased risk of other psychiatric disorders in adulthood.[10,11] An understanding of the challenges inherent in the assessment and diagnosis of patients with CO-OCD and the principles guiding management is therefore critical to ensuring optimal outcomes for children and families.

Epidemiology

Most epidemiological studies report OCD prevalence between 0.25% and 4%,[12,13,14] although exact prevalence is affected by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) version used to determine the diagnosis.[9] Approximately half of all patients with OCD present before the age of 15 years.[15] There are three peaks of onset in males, the first prepuberty at 8–10 years, the second in early adulthood between 18 and 22, and the third later in the second decade.[16,17] In females, peak onset is between 10 and 20 years.[18] Clinical samples of individuals with CO-OCD have a male predominance, while epidemiological studies of children and adolescents report equal rates overall for both genders.[19] Males are more likely to have prepubertal onset, a positive family history of OCD, and comorbid tic disorder.[20] The prevalence of OCD is consistent across diverse socioeconomic strata and across countries, suggesting that race and culture are unlikely to be causal factors.[19] However, cultural factors may influence the content of obsessions and compulsions.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Environmental factors

There are no clearly established environmental risk factors for CO-OCD. Many patients describe symptom onset following a stressful precipitating event.[21] A recent retrospective study found no evidence for an association between adverse childhood experiences and OCD, although such experiences were associated with the presence of psychiatric comorbidities in individuals with OCD, including depression.[11] Some data suggest a possible association with higher recalled rates of perinatal complications and advanced paternal age.[22] A large body of work suggests an association between streptococcal infection and an abrupt, early-onset form of OCD, termed pediatric autoimmune disorder associated with Streptococcus (PANDAS),[23] although the strength of this association is controversial and evidence for causation is limited. These patients are thought to develop postinfectious autoimmunity targeting the basal ganglia, as described for Sydenham's chorea, a neuropsychiatric complication of rheumatic fever.[24] More recent epidemiological data also suggest an association between nonstreptococcal pharyngitis and OCD that is greater than for other anxiety disorders.[25] The broader category of pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) has been proposed to include all cases of acute-onset OCD or restricted food intake with associated neuropsychiatric symptoms, independent of streptococcal infection.[26] PANS/PANDAS may account for approximately 5% of children attending general pediatric OCD (POC) outpatient clinics.[27]

Genetics

While the underlying biological mechanisms remain to be elucidated, meta-analyses of family studies suggest heritability between 45% and 65%,[28,29] higher than most other anxiety and mood disorders in youth and higher than in patients with the adult-onset illness.[30] The risk of OCD in a first-degree relative of a proband may be as high as 10%–17%, compared to 2%–3% in controls.[31] Molecular genetic studies including segregation analyses, linkage studies, candidate gene studies, and genome-wide association studies suggest a complex disorder for which many gene variants likely confer vulnerability, each with a relatively small effect. Genetic association studies have implicated single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes involved in glutamatergic transmission and synaptic function, although none has yet reached genome-wide significance.[32,33,34,35] Genes that affect serotonergic and dopaminergic function may also contribute to OCD susceptibility.[36]

Pathophysiology

Although results of structural studies have been inconsistent, functional neuroimaging data provide support for dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, and interconnecting pathways. Importantly, different symptom dimensions may be mediated by distinct but overlapping neural systems.[37,38] These may include a ventromedial “emotion” circuit and a dorsolateral “cognitive” circuit.[39] Hyperactivation of the orbitofrontal cortex has been proposed to mediate persistent thoughts about threat and harm, which in turn lead to attempts to neutralize the perceived threat. In addition to the involvement of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex in the regulation of fear and anxiety associated with some symptom dimensions, growing evidence suggests dysfunctional reward circuitry.[40] With respect to neurotransmitters, a proposed role for serotonergic dysregulation is suggested by symptom responsiveness to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), worsening of symptoms with serotonin agonists, and an association between OCD severity and cerebrospinal fluid levels of 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid, the main metabolite of serotonin. Dopamine has also been strongly linked to disorders presenting with obsessive–compulsive behavior.[41] Other studies have implicated glutamatergic neurotransmission, the neuropeptides oxytocin and vasopressin, and opioid peptides.[42,43,44]

Immune dysfunction

While evidence for causative pathogenic autoantibodies in CO-OCD including PANDAS is lacking,[45,46] data from studies in patients with “classic” OCD suggest an association with aberrant innate immune activation. This includes altered levels of systemic cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1 β[47,48,49,50] as well as lower than expected immunoglobulin levels.[51,52,53] Moreover, a recent positron emission tomography imaging study in adults with OCD – many with CO – showed the increased volume of translocator protein-18 distribution in cortico-striato-thalamocortical circuits, implicating widespread microglial activation.[54] It is unclear whether changes in cellular and soluble inflammatory markers represent underlying etiology, a consequence of disease progression, or associated epiphenomena.

Outcomes

CO-OCD interferes with normal neurodevelopment and is associated with higher prevalence of anxiety disorders in adulthood.[10] Longitudinal data suggest that 41% of children have persistent OCD, with one-third experiencing moderate-to-severe symptoms.[11] In addition, a meta-analysis of outcome data suggested that 40% of children experience full remission and 19% of children have subclinical symptoms or partial remission at follow-up.[7] A more recent follow-up study suggested 66% of participants were in remission and a total of 85% of participants had responded to treatment at 3-year follow-up, with a significant improvement in psychosocial functioning.[55] Remission predictors include older age at OCD onset, shorter duration of illness, and outpatient status. Factors that may contribute to a more benign course include the presence of a precipitating event, episodic nature of the symptoms, and good social/occupational adjustment.[56,57] Factors that contribute to a more disabling, chronic course include early age of onset, presence of tics, comorbid major depressive disorder, parental psychopathology, poor response to medication, and severity at onset.[57,58,59,60] In a recent follow-up study of children with PANS/PANDAS, 88% were not experiencing clinically significant symptoms at up to 4.8 years following initial treatment; the authors suggest this may support conceptualization of PANDAS as a subacute illness, although some children developed more chronic symptoms.[61]

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Given the high prevalence and significant cost associated with delayed treatment, OCD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of all children and adolescents presenting with repetitive behaviors or anxiety. Since youth with obsessions and compulsions often do not spontaneously report symptoms (particularly violent or sexual obsessions) or may minimize their severity, a systematic approach to assessment is critical and should be informed by history taken from both the patient and family. Diagnostic criteria and critical elements of the assessment process are discussed below.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 diagnostic criteria

OCD is listed as a “neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorder” along with anxiety disorders in ICD-10, and was similarly classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV. However, given increasing evidence for differences in the phenomenology and etiology of OCD compared with other anxiety disorders, it now falls within “OCD and related disorders” (OCRDs) in DSM-5.[19] The diagnosis requires the presence of obsessions, compulsions, or both. Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or images that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted and cause anxiety or distress; the individual attempts to ignore, suppress, or neutralize them.[62] Compulsions are defined as repetitive behaviors or mental acts that the individual feels driven to perform in response to an obsession or according to rigidly applied rules; these are aimed at reducing anxiety or distress or preventing a dreaded situation.[62] The obsessions or compulsions must be time-consuming or cause significant distress. The level of insight and presence of tics are included as specifiers.[62] Compared to adults, children with OCD may not always realize that their worries or behaviors are excessive, seeing rituals as protective acts; nevertheless, a range of insight is seen in children and adolescents (Selles et al., 2018)[63] as in adults. The symptom content may differ by age, with religious and somatic symptoms reported to be more common in children compared to adolescents or adults. Other symptoms noted particularly in children include “just right” obsessions, compulsions that may involve family members such as parents, and superstitious rituals associated with magical thinking.[64]

Pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome/pediatric autoimmune disorder associated with Streptococcus diagnostic criteria

As defined by Swedo et al. in the first case series published in 1998, PANDAS is characterized by acute onset of OCD and/or a tic disorder between the ages of three and puberty, evidence of preceding Group A streptococcal infection, other neurological abnormalities, and an episodic course.[23] More recently, PANS has been defined as abrupt, dramatic onset of OCD, or severely restricted food intake with concurrent acute onset of at least two of anxiety; emotional lability and/or depression; irritability, aggression, or severely oppositional behavior; behavioral regression; deterioration in school performance; sensory or motor abnormalities; and somatic signs and symptoms.[26] We recently reported a 5% prevalence of PANS/PANDAS among a general clinic population of children with OCD.[27]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses to consider include generalized anxiety disorder; specific phobias; other OCRDs including body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder; eating disorders; tic disorders; autism spectrum disorder; and genetic syndromes. Psychotic disorders should also be ruled out, particularly in the mid-to-late teens. Finally, OCD symptoms should be distinguished from normative behavior, in particular, nonimpairing rituals in preschoolers that are appropriate to the developmental stage.

Assessment

Standardized assessment tools

A structured systematic assessment may be facilitated by the use of standardized tools including the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS), a 10-item clinician-rated instrument designed to assess symptom severity.[65] The child version (CV) of the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory (OCI-CV)[66] and the Children's Florida Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory (C-FOCI)[67] are self-report instruments developed to screen for OCD symptoms in clinical and nonclinical settings and do not require as much clinician time. The Child Behavior Checklist – obsessive–compulsive scale (CBCL-OCS) may also be used for screening purposes[68] and measures such as the OCI-CV and C-FOCI are preferred over the Leyton Obsessional Inventory-CV.[69]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder symptoms

The assessment should begin by characterization of the duration and severity of OCD symptoms in addition to precipitating, exacerbating, perpetuating, and ameliorating factors. Family or school stressors or physical illness are often reported to precede the onset or worsening of OCD. As unrecognized symptoms may be present, a review of all OCD symptom categories is helpful. Overlapping groups or “symptom dimensions” are generally stable throughout development and in pediatric OCD Include ‘just right’ (symmetry obsessions, ordering, repeating, counting and checking compulsions and hoarding), ‘forbidden thoughts’ (sexual, religious and aggressive obsessions) and ‘contamination’ (contamination and somatic obsessions and cleaning compulsions). Of note, checking and somatic symptoms move to the ‘forbidden thoughts’ dimension in adult OCD.[70] Other common compulsions include reassurance-seeking, counting, praying, and mental rituals. Many individuals experience multiple symptoms at any one time, and these may change over the course of the illness.[71] While children may be less likely to have insight into the irrationality of their obsessions and compulsions compared to adults,[6] a range of insight is present in children as in adults. While some studies in adults suggest an association between insight and both OCD symptom severity[72] and outcomes,[73] more work is required to understand these relationships in children.

Associated signs and symptoms

While sleep disturbances are often reported by parents of children with OCD, previous studies that use objective sleep measures have been limited.[74] A recent study by our group demonstrated a clinically relevant sleep disturbance in 70% of children with OCD compared to 15% of healthy controls, particularly increased wakening, delayed subsequent sleep, and poorer sleep hygiene. Unlike adult OCD, there was no circadian shift.[75]

Abnormalities in prefrontal-striatal circuits may affect executive function, which is impaired in adults with OCD[76] and may represent an endophenotype given deficits in decision-making and planning that aggregate in families with OCD.[77] However, differences in cognitive dysfunction may differ between adults and youth,[78] and studies of executive function deficits in children are limited. Recent data suggest that parents of children with OCD report significantly greater executive dysfunction compared to parents of healthy controls.[79] However, objective testing reveals more subtle deficits affecting planning but not impulsivity, cognitive flexibility, attention, or spatial working memory in a laboratory setting.[79] CO-OCD may also be associated with a slower processing speed.[80]

Neurological soft signs (NSS) are defined by the abnormal motor or sensory findings in the absence of a localized neurological disorder and have been implicated in OCD. A meta-analysis of studies assessing NSS in adults with OCD suggested significantly higher rates compared to matched controls, present bilaterally and in multiple domains (motor coordination, sensory integration, and primitive reflexes).[81] These subtle neurologic abnormalities may characterize subgroups of patients with more severe symptoms[82] and poorer treatment response.[83] In children, deficits in visuospatial and fine-motor skills based on neuropsychological testing may also predict poor long-term outcomes.[84] It is unclear whether executive dysfunction or neurologic soft signs represent potential endophenotypes in children.

Functional consequences

Quality of life is related to OCD symptom severity and impairment.[85] Clinicians should review the functional consequences of OCD symptoms in home, school, and social environments. Psychoeducational assessment should be considered if there is any history of academic difficulties. Indeed, students with OCD report difficulty with concentration on school work and homework completion,[86] and a recent pilot study identified significantly higher rates of math deficits in patients with CO-OCD compared to healthy controls.[87] Coercive and disruptive behaviors may be assessed using the Coercive and Disruptive Behaviour Scale-POCD.[88] Family functioning and accommodation of symptoms can be assessed using the OCD Family Functioning Scale[89] and the Family Accommodation Scale,[90] respectively. The latter measures ways in which family members take part in the performance of rituals, facilitate avoidance of anxiety-provoking situations, or modify routines. Family accommodation is associated with increased parental anxiety symptoms and is associated with treatment outcomes.[91] In a multisite study of family functioning impairment, our group recently showed that 50% of mothers, 30% of fathers, and 70% of youth reported daily occupational/school impacts; most patients and their parents reported often or always feeling stressed/anxious or frustrated/angry. Commonly disrupted routines related to bedtime, morning, family events, mealtimes, and work/school. More mothers than patients or fathers reported feeling sad while more patients compared to their parents reported feelings of guilt. Importantly, family accommodation predicted family impairment.[89]

Pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome/pediatric autoimmune disorder associated with Streptococcus

In assessing children for PANS/PANDAS, standard laboratory investigations may be ordered according to clinical judgment to rule out suspected medical diagnoses including active infection, immune deficiency, and neurologic disease. These may include a complete blood count, liver/renal function, urinalysis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, streptococcal antibodies including antistreptolysin-O antibody and anti-DNAase B, and throat culture. As many healthy individuals have positive anti-streptococcal antibodies by adolescence, a minimum of two blood draws are required to establish increasing titers following acute infection. Additional investigations in the setting of suspected infection, autoimmune disease, or immunodeficiency may include anti-nuclear antibodies, swabs and cultures of active lesions, immunoglobulin levels, and lymphocyte phenotyping. Given the unclear and likely heterogeneous etiology of patients meeting diagnostic criteria for PANS, the medical workup should be patient specific with a general approach informed by consensus guidelines.[26]

Psychiatric comorbidities

Up to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have one or more comorbid psychiatric conditions. A thorough screening is critical as the presence of psychiatric comorbidities may affect treatment response,[92] and some comorbidities such as bipolar disorder or unipolar depression should be treated first to allow optimization of OCD-specific therapy.[93] The most common comorbidities include major depressive disorder (66%); attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, more often inattentive subtype), oppositional defiant disorder or anxiety disorders (50%), and enuresis or speech and language disorders (33%).[94] Tics are thought to occur in 10%–40% of patients with CO-OCD.[95] Comorbid OCRDs – including body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding disorder, and trichotillomania – are all characterized by repetitive thinking or behavior and are more prevalent among patients with OCD. Finally, suicidal ideation and completed suicide attempts are more common in adult patients with OCD than the general population and require regular assessment in all age groups.[96]

Psychiatric history

Details of previous OCD treatment that may affect management include the duration, maximum dose, and tolerability of the past medications. SRI trials are often discontinued prematurely or involve a suboptimal dose. In assessing the past psychotherapy trials, details of the specific therapeutic modality should be established; while cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) including exposure and response prevention (ERP) has established efficacy, supportive therapy, and relaxation training do not.[97] Other factors that may inform treatment include a history of substance use, which may affect adherence to the management plan. The past mood instability particularly in response to SRI monotherapy may suggest increased risk of hypomanic or manic symptoms with the administration of serotonergic agents. Moreover, any history of panic attacks or anxiety regarding medication side effects should be elicited and may prompt very cautious titration of serotonergic agents to avoid triggering further anxiety symptoms. Finally, clinicians should take a thorough family history of OCD and OCRDs, as well as any treatment trials that have effectively treated symptoms in family members.[9]

Medical history and comorbidities

Relevant medical history includes neurological conditions, head injuries or seizures, endocrine abnormalities, symptoms that may overlap with possible medication side effects, and pregnancy. While limited data addressing, the prevalence of medical comorbidities exists for CO-OCD, multiple conditions including migraines and respiratory diseases are more common among adults with OCD[98] and should be queried in children. Guidelines for the evaluation of youth with PANS point to the need for a thorough personal and family history of immune-mediated disorders.[26] Moreover, a recent large birth cohort study based on the Swedish National Register data suggested increased rates of multiple autoimmune diseases among patients with classic OCD as well as their first-degree relatives, including inflammatory bowel disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, celiac disease, psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, Sjögren's syndrome, Guillain–Barré syndrome, and scarlet fever.[99] The previous work has also suggested a familial relationship between OCRDs and rheumatic fever; an autoimmune disease thought to arise from humoral and cellular autoreactivity following Group A streptococcal pharyngitis.[100] An improved understanding of shared genetic and environmental risks for comorbid medical conditions – in addition to the effects of medical comorbidities on OCD symptom content – may pave the way for further interventional trials and facilitate collaborative multidisciplinary care for children affected by multiple physical and psychiatric conditions.

TREATMENT

General approach

The two first-line evidence-based treatment approaches for the management of pediatric OCD are CBT and SRI medications, including both serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and clomipramine). The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry practice parameter recommends CBT as the initial treatment for children with mild-to-moderate OCD, in combination with SRIs for moderate-to-severe cases.[101] Indeed, for many moderate-to-severe cases, a combination of CBT and medication is an optimal first-line approach. However, for cases in which potential medication side effects outweigh benefits, including those with mild illness and a CY-BOCS score under 15, an initial trial of CBT alone may be preferred. An initial trial of SSRI monotherapy may be optimal for those with marked to severe illness (e.g., CY-BOCS score 24 and above) who do not have access to a CBT-trained clinician or who have limited motivation.[101]

Evidence for combined treatment

The POC Treatment Study (POTS) showed no difference between CBT alone and sertraline monotherapy with respect to OCD severity after 12 weeks. However, CBT was associated with higher remission rates, and a combination of CBT and sertraline was superior to either alone.[102] A subsequent meta-analysis confirmed superior response to combined treatment compared to SSRI monotherapy, but not CBT alone.[103] Indeed, a recent review of randomized trials directly comparing SRIs to CBT also found the latter to be more effective in achieving a response in youth with OCD when delivered by well-trained clinicians.[104] For those demonstrating a partial response to an SSRI, a follow-up to the original POTS study (POTS-II) demonstrated the superiority of full CBT augmentation, compared to medication monotherapy or medication management with brief instruction in CBT by a psychiatrist. These results highlight the need for OCD-trained CBT therapists in the management of CO-OCD.[105]

Response predictors

Positive response predictors for both CBT and SRIs include lower OCD severity and functional impairment, greater insight, less family accommodation, and absence of comorbid externalizing symptoms.[91] Comorbid tics are a negative predictor of response to SSRIs, and initiation with CBT alone or combined with an SSRI is preferable to SSRI monotherapy in this group.[106] For CBT, a poorer response is associated with a family history of OCD, other family psychopathology, and dysfunction within the family structure.[107,108]

Treatment of comorbidities

In the presence of significant psychiatric comorbidities, the order of treatment requires careful consideration. Other conditions, including eating disorders, depression, and mood instability, may require specific pharmacological or psychological treatment before targeting OCD. Stimulant treatment for ADHD should be used cautiously until OCD symptoms have stabilized, as these medications may increase anxiety.[109] On the other hand, if a child experiences ongoing academic difficulties despite improvement in OCD symptoms, other diagnoses including ADHD must be ruled out or treated.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT for POC as delivered in clinical trials is a short-term treatment, usually between 12 and 20 weekly sessions. Goals include improved control, tolerance of distress and uncertainty, and an enhanced sense of self-efficacy. The first step involves psychoeducation covering OCD neurobiology and symptoms, as well as an explanation of treatment options. A recent report suggests a potential role for genetic counseling as part of the psychoeducation process, with positive impacts on parental treatment orientation.[110] Families can be referred to online resources such as the Pediatric International OCD Foundation website at http://kids.iocdf.org.

Elements of cognitive behavioral therapy

The most promising treatment protocols incorporate ERP, cognitive strategies, and relapse prevention with modifications for pediatric patients to include family members.[111] Response prevention is based on the assumption that rituals and compulsions reduce distress through negative reinforcement. Exposure relies on a gradual decrease in distress after prolonged exposure to a stimulus during which the individual does not engage in compulsive behaviors. The goal is to alter the reaction to the obsession (not necessarily the intensity of the obsession itself), with more rapid attenuation of distress in subsequent exposures. While ERP is central to most manualized programs examined in controlled trials, few POC clinicians actually use exposure techniques, leading to apparent treatment resistance.[112] Cognitive techniques vary from a focus on coping statements to modification of thought appraisal,[113] although anecdotally may be less helpful in children. Overall limitations of CBT include lack of access to qualified practitioners and comorbidities interfering with engagement, as well as significant rates of ERP discontinuation because of the anxiety created by exposures. A previously agreed upon reward for effort, given promptly following ERP, together with reinforcing parent and therapist praise may provide effective positive reinforcement.[113] Emerging evidence also suggests a role for other behavioral modalities – in particular acceptance and commitment therapy[114,115] – that focus on modifying the experience of obsessions rather than their severity or frequency.

Family involvement

Emerging evidence points to the efficacy of family-based CBT.[116] Moreover, symptom reduction is similar in group- and individual-delivered sessions compared to wait-list controls, and may also be effective when delivered by webcam.[117] We recently showed that a group-and-family-based CBT program significantly improves a wide range of domains for youth/families that extends beyond OCD symptom severity.[118] In addition, family interventions designed to reduce family accommodation of OCD symptoms, including enabling of trigger avoidance and rituals, may run concurrently with individual or group CBT and are effective in adults;[119] studies in POC are ongoing. Parental involvement may be particularly beneficial in treating young children. Further work is needed to determine the effects of programs targeting parents on distress tolerance, family accommodation, and symptom severity.

Pharmacotherapy

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

SRIs include SSRIs as well as the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) clomipramine. Although there is some evidence for higher efficacy of clomipramine, initial treatment should begin with an SSRI given the increased frequency and seriousness of adverse effects with clomipramine.[104] Medications in this class have been associated with a 29%–44% reduction in symptoms and are generally safe and well-tolerated.[97] Although a range of SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram) are similarly effective, there are significant differences in adverse effects.[120] Thus, SSRI selection should consider side effect profiles, potential drug interactions, and family history of responsiveness. In the UK, only sertraline and fluvoxamine are licensed for use in children.[121] SSRIs with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for POC include fluoxetine (for children over 7 years), sertraline (for children 6 years and older), and fluvoxamine (for children over 8 years). Paroxetine is approved for treatment of adult but not POCD. Despite lack of FDA approval, escitalopram has demonstrated efficacy in adult OCD and citalopram in children.[122] Any of these may be prescribed based on the clinical judgment, and all may be formulated as oral suspensions if children are unable to swallow pills.[9]

Adverse effects of SSRIs often precede benefits and include initial increased anxiety, irritability, fatigue, headache, nausea, diarrhea, insomnia, and possible weight gain. Youth – particularly younger children – may be especially prone to behavioral activation, often up to several weeks after starting the medication. This often resolves with dosage decreases.[123] SSRI-induced mania is far less common and may occur in the context of a family or personal history of bipolar disorder. Antidepressants have been associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation among youth, resulting in a black box warning for suicidality in patients under the age of 18 years. However, there is no evidence of an increase in completed suicide and – for fluoxetine – no effect on suicidality when considering mediating effects of depressive symptoms.[124] In POCD, SSRI-induced benefits typically outweigh the risks of a suicidal event,[125] with no absolute risk difference between SSRIs and placebo. With respect to long-term impacts, there is no evidence to date that SSRIs negatively affect neurodevelopment.[126]

Assessment and monitoring

Baseline laboratory and clinical evaluations may include measurement of blood pressure, weight, abdominal circumference, and height. Before initiation of clomipramine, a family cardiac and seizure history should be obtained, in addition to a lipid profile, liver enzymes, renal function, and an ECG. Physical complaints before the medication trial should also be recorded to allow differentiation from new adverse effects.

Duration of a treatment trial

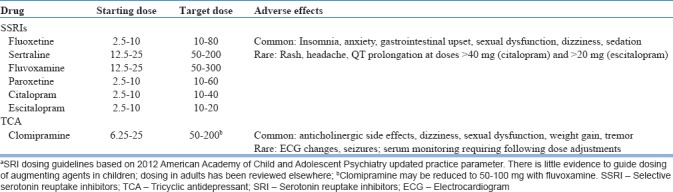

SSRI optimization requires titration to the maximum tolerated dose within the recommended range and a minimum trial of 12 weeks, including 3 weeks at the highest dose.[101] Dosage increases may be made every 2–4 weeks. Recommended doses [Table 1] are typically higher than those required for depression.[101] Unlike depression, which has a nonlinear dose-response curve, an increase from medium to high SSRI dose in adults with OCD results in a 7%–9% improvement in severity,[127] although the benefit of doses beyond the FDA-approved range has not been well-established in children and the greatest incremental gains occur early in SSRI treatment.[128] Given the relatively benign side effect profile, a dose escalation strategy is often preferred to the use of augmenting agents with higher associated risks.[129] Symptom reduction is more common than remission. In clinical trials, “response” is typically defined by either a ≥25% or ≥35% decrease in Y-BOCS–defined OCD severity. Meta-analyses suggest that SRI treatment results in an approximate 30%–40% reduction in symptom severity and a response rate of approximately 50% in OCD-affected youth.[120]

Table 1.

Dosing guidelines for first-line pharmacologic agents in childrena

Clomipramine

The mechanism of clomipramine is thought to be related to its specific inhibition of serotonin reuptake,[104] as other TCAs with less serotonergic activity are not effective. Clomipramine may be used as an alternative following two failed SSRI trials. Its use requires a detailed personal and family history of heart disease and seizures, physical examination, and ECG at baseline as well as 1–2 weeks following dose adjustment. Serum levels of clomipramine and its nonserotonergic metabolite, desmethylclomipramine (DCMI), should be used to determine dose adjustments.[130] The possible adverse effects are classified as anticholinergic (dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and urinary hesitancy), anti-histaminergic (sedation and weight gain), autonomic anti-adrenergic (postural hypotension, intracardiac conduction slowing, sweating, increased blood pressure, and tremor), and anti-serotonergic (sexual dysfunction and nausea), and at toxic levels can also cause confusion and seizures.

Treatment augmentation

Second-line medication strategies should be considered for individuals who continue to experience moderate-to-severe symptoms despite adequate trials of multiple SRIs in addition to CBT with a skilled therapist. Augmenting and alternative treatment strategies have less evidence in children than in adults. These include augmentation of SSRIs with clomipramine or augmentation of SRIs with antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, or glutamate modulators.[101]

While no RCTs have examined the combination of clomipramine with an SSRI in children, it may maximize SRI. Furthermore, combination with fluvoxamine may help minimize levels of the clomipramine metabolite DCMI, which contributes to noradrenergic effects but does not affect serotonin reuptake. Fluvoxamine, which inhibits cytochrome P450-mediated hepatic metabolism of clomipramine, may therefore be considered as a third agent following one or two trials of another SSRI. This protocol permits lower clomipramine dosages and increased tolerability but requires monitoring of ECG indices and serum clomipramine levels.

Atypical antipsychotics combine serotonin and dopamine receptor inhibition. In adults, meta-analyses have demonstrated the modest benefit from risperidone and aripiprazole, with weaker evidence for olanzapine and quetiapine.[131] Importantly, no controlled trials of antipsychotic augmentation exist in children. Small observational trials of aripiprazole and risperidone augmentation have shown some benefit but associated metabolic side effects require regular monitoring.[132,133] The use of low doses may mitigate long-term metabolic risks to some extent, but ERP augmentation of SSRI treatment should be optimized before the addition of an antipsychotic when possible and may be comparatively more effective.[134] In most cases, a clomipramine trial is warranted before consideration of augmentation with an antipsychotic given that more evidence exists for the efficacy of clomipramine and that long-term metabolic risks of antipsychotics in children with OCD have not been well-characterized.[129] This is consistent with recent North American and UK practice parameters recommending a minimum of two different adequate SSRI trials or an SSRI and clomipramine before consideration of augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic in both children and adults.[101,135]

Other strategies described in adults include venlafaxine and duloxetine replacement monotherapy or benzodiazepine augmentation, but to date, there are few controlled studies in children and limited evidence for efficacy in adults. In some cases, benzodiazepines may be helpful for short-term use. Increasing evidence suggests glutamate dysregulation may contribute to OCD pathogenesis,[129] and glutamate modulators may be a reasonable option for the treatment-refractory disease. These include antiepileptics such as topiramate and lamotrigine, n-acetylcysteine, memantine, riluzole, D-cycloserine, and ketamine.[136] Other approaches that show promise for refractory adult OCD include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation, but there is no evidence for these approaches in pediatric disease. For severe refractory OCD cases, intensive residential treatment can also be considered.[137]

Treatment of pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome/pediatric autoimmune disorder associated with Streptococcus

Optimal long-term management of PANDAS/PANS remains a matter of debate. A recent systematic review points to the lack of systematic studies of immune-modulating therapies, with some support but generally inconclusive evidence for the use of antibiotics (penicillin, amoxicillin, or cephalosporins), intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroids.[138] Recent treatment guidelines are therefore largely based on expert consensus.[139] Small studies suggest that OCD symptoms in this population respond well to standard treatments; SSRIs should be initiated at a low dose given the risk of behavioral activation. There is also early evidence that the PANDAS/PANS subgroup responds to CBT.[140] Further controlled trials are needed in both PANDAS/PANS and classic OCD to understand the role of inflammatory changes and assess the benefit of therapies targeting innate or adaptive immunity.

Treatment duration

Effective medication regimes that have led to symptom improvement or remission should be continued for at least 6–12 months. Importantly, the cumulative improvement was demonstrated over a 1-year period in a trial of sertraline.[120] Medication may be then be gradually discontinued over several months, although the relapse rate following discontinuation is high. In adult responders, these rates range between 24% and 89% after 6 months[9] but are reduced in those who have also received CBT.[141] Tapering should be done slowly, ideally over a low-stress period; if symptoms re-emerge, booster, or refresher ERP sessions can be tried before returning to a higher medication dose. For individuals who have had multiple relapses and moderate-to-severe illness, long-term treatment may be required.[101]

CONCLUSIONS

POCD is a common but under-recognized neuropsychiatric disorder associated with multiple psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Delays to treatment are common and may have a critical long-term impact on development and function. However, early evidence-based treatment significantly modifies this trajectory. Indeed, outcomes are more optimistic than for adult OCD; up to two-thirds of children achieve remission and a substantial additional proportion show a partial response. A structured diagnostic assessment facilitated by standardized assessment scales allows the clinician to elicit symptoms that may otherwise go unreported. In addition to obsessions, compulsions, and insight, functional domains that may be affected in OCD include sleep, executive function/planning, and school performance. The assessment should also include the impact of OCD on family function in addition to family accommodation of OCD symptoms, which in turn may predict family function and treatment outcomes. The current mainstay of treatment includes CBT, both individual and family based, and SRIs. Limited access to CBT often poses a significant barrier to optimal treatment; the current research is aimed at establishing more accessible and economic formats. For children who do not respond to multiple medication trials in combination with CBT, evidence-based treatment is lacking. An improved understanding of the genetic and biological basis of OCD may lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Financial support and sponsorship

SES is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, and British Columbia Mental Health and Substance Use Research Institute.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollander E, Doernberg E, Shavitt R, Waterman RJ, Soreni N, Veltman DJ, et al. The cost and impact of compulsivity: A research perspective. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:800–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.do Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF, Curi M, Quatrano S, Katsovitch L, Miguel EC, et al. A family study of early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;136B:92–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chabane N, Delorme R, Millet B, Mouren MC, Leboyer M, Pauls D, et al. Early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: A subgroup with a specific clinical and familial pattern? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:881–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Grootheest DS, Cath DC, Beekman AT, Boomsma DI. Twin studies on obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005;8:450–8. doi: 10.1375/183242705774310060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geller DA, Biederman J, Faraone S, Agranat A, Cradock K, Hagermoser L, et al. Developmental aspects of obsessive compulsive disorder: Findings in children, adolescents, and adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:471–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart SE, Geller DA, Jenike M, Pauls D, Shaw D, Mullin B, et al. Long-term outcome of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis and qualitative review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:4–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fireman B, Koran LM, Leventhal JL, Jacobson A. The prevalence of clinically recognized obsessive-compulsive disorder in a large health maintenance organization. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1904–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart SE, Hezel D, Stachon AC. Assessment and medication management of paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Drugs. 2012;72:881–93. doi: 10.2165/11632860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wewetzer C, Jans T, Müller B, Neudörfl A, Bücherl U, Remschmidt H, et al. Long-term outcome and prognosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder with onset in childhood or adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s007870170045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Micali N, Heyman I, Perez M, Hilton K, Nakatani E, Turner C, et al. Long-term outcomes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Follow-up of 142 children and adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:128–34. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flament MF, Whitaker A, Rapoport JL, Davies M, Berg CZ, Kalikow K, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder in adolescence: An epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:764–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyman I, Fombonne E, Simmons H, Ford T, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the british nationwide survey of child mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:324–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglass HM, Moffitt TE, Dar R, McGee R, Silva P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in a birth cohort of 18-year-olds: Prevalence and predictors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1424–31. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1094–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anholt GE, Aderka IM, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, Schruers K, van der Wee NJ, et al. Age of onset in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Admixture analysis with a large sample. Psychol Med. 2014;44:185–94. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, Park K, Schwartz S, Shapiro S, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:420–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart SE, Lafleur D, Dougherty DD, Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Jenike MA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, editors. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Boston, Massachusetts: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 367–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coskun M, Zoroglu S, Ozturk M. Phenomenology, psychiatric comorbidity and family history in referred preschool children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomsen PH. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: A study of parental psychopathology and precipitating events in 20 consecutive Danish cases. Psychopathology. 1995;28:161–7. doi: 10.1159/000284916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Liu X, Luo H, Deng W, Zhao G, Wang Q, et al. Advanced paternal age increases the risk of schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perlmutter S, et al. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:264–71. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams KA, Swedo SE. Post-infectious autoimmune disorders: Sydenham's chorea, PANDAS and beyond. Brain Res. 2015;1617:144–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlovska S, Vestergaard CH, Bech BH, Nordentoft M, Vestergaard M, Benros ME, et al. Association of streptococcal throat infection with mental disorders: Testing key aspects of the PANDAS hypothesis in a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:740–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang K, Frankovich J, Cooperstock M, Cunningham MW, Latimer ME, Murphy TK, et al. Clinical evaluation of youth with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): Recommendations from the 2013 PANS consensus conference. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25:3–13. doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaspers-Fayer F, Han SH, Chan E, McKenney K, Simpson A, Boyle A, et al. Prevalence of acute-onset subtypes in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:332–41. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mataix-Cols D, Boman M, Monzani B, Rück C, Serlachius E, Långström N, et al. Population-based, multigenerational family clustering study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:709–17. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nestadt G, Samuels J, Riddle M, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Liang KY, LaBuda M, et al. A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:358–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eley TC, Bolton D, O’Connor TG, Perrin S, Smith P, Plomin R. A twin study of anxiety-related behaviours in pre-school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:945–60. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nestadt G, Grados M, Samuels JF. Genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:141–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor S. Molecular genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comprehensive meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:799–805. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart SE, Yu D, Scharf JM, Neale BM, Fagerness JA, Mathews CA, et al. Genome-wide association study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:788–98. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattheisen M, Samuels JF, Wang Y, Greenberg BD, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, et al. Genome-wide association study in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Results from the OCGAS. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:337–44. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC) and OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS). Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive-compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1181–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pauls DL, Abramovitch A, Rauch SL, Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: An integrative genetic and neurobiological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:410–24. doi: 10.1038/nrn3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mataix-Cols D, van den Heuvel OA. Common and distinct neural correlates of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:391–410. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.006. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauch SL, Britton JC. Developmental neuroimaging studies of OCD: The maturation of a field. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1186–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Heuvel OA, Remijnse PL, Mataix-Cols D, Vrenken H, Groenewegen HJ, Uylings HB, et al. The major symptom dimensions of obsessive-compulsive disorder are mediated by partially distinct neural systems. Brain. 2009;132:853–68. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Figee M, Vink M, de Geus F, Vulink N, Veltman DJ, Westenberg H, et al. Dysfunctional reward circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:867–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denys D, de Vries F, Cath D, Figee M, Vulink N, Veltman DJ, et al. Dopaminergic activity in tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pittenger C, Bloch MH, Williams K. Glutamate abnormalities in obsessive compulsive disorder: Neurobiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132:314–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marazziti D, Baroni S, Giannaccini G, Catena-Dell’Osso M, Piccinni A, Massimetti G, et al. Plasma oxytocin levels in untreated adult obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2015;72:74–80. doi: 10.1159/000438756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perreault ML, Seeman P, Szechtman H. Kappa-opioid receptor stimulation quickens pathogenesis of compulsive checking in the quinpirole sensitization model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:976–91. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dale RC, Heyman I, Giovannoni G, Church AW. Incidence of anti-brain antibodies in children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:314–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morer A, Lázaro L, Sabater L, Massana J, Castro J, Graus F, et al. Antineuronal antibodies in a group of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder and tourette syndrome. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gray SM, Bloch MH. Systematic review of proinflammatory cytokines in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:220–8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell RH, Goldstein BI. Inflammation in children and adolescents with neuropsychiatric disorders: A systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:274–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Şimşek Ş, Yüksel T, Çim A, Kaya S. Serum cytokine profiles of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder shows the evidence of autoimmunity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19:pii: pyw027. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, Ravi V, Kalmady S, Cherian A, Yc JR, et al. Plasma cytokine abnormalities in drug-naïve, comorbidity-free obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:949–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calaprice D, Tona J, Parker-Athill EC, Murphy TK. A survey of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome characteristics and course. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:607–18. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawikova I, Grady BP, Tobiasova Z, Zhang Y, Vojdani A, Katsovich L, et al. Children with tourette's syndrome may suffer immunoglobulin A dysgammaglobulinemia: Preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:679–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams KA. IgA deficiency is associated with pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. Abstract. Clinical Immunology Society Annual Meeting. Boston, Massachusetts. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Attwells S, Setiawan E, Wilson AA, Rusjan PM, Mizrahi R, Miler L, et al. Inflammation in the neurocircuitry of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:833–40. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melin K, Skarphedinsson G, Skärsäter I, Haugland BS, Ivarsson T. A solid majority remit following evidence-based OCD treatments: A 3-year naturalistic outcome study in pediatric OCD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27:1373–81. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Denys D, Burger H, van Megen H, de Geus F, Westenberg H. A score for predicting response to pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:315–22. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skoog G, Skoog I. A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder [see commetns] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:121–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leonard HL, Lenane MC, Swedo SE, Rettew DC, Gershon ES, Rapoport JL, et al. Tics and tourette's disorder: A 2- to 7-year follow-up of 54 obsessive-compulsive children. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1244–51. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shetti CN, Reddy YC, Kandavel T, Kashyap K, Singisetti S, Hiremath AS, et al. Clinical predictors of drug nonresponse in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1517–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leon J, Hommer R, Grant P, Farmer C, D’Souza P, Kessler R, et al. Longitudinal outcomes of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27:637–43. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selles RR, Højgaard DRMA, Ivarsson T, Thomsen PH, McBride N, Storch EA, et al. Symptom insight in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Outcomes of an international aggregated cross-sectional sample. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;57:615–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalra SK, Swedo SE. Children with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Are they just “little adults”? J Clin Invest. 2009;119:737–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI37563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children's yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: Reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–52. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foa EB, Coles M, Huppert JD, Pasupuleti RV, Franklin ME, March J, et al. Development and validation of a child version of the obsessive compulsive inventory. Behav Ther. 2010;41:121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Storch EA, Khanna M, Merlo LJ, Loew BA, Franklin M, Reid JM, et al. Children's florida obsessive compulsive inventory: Psychometric properties and feasibility of a self-report measure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in youth. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2009;40:467–83. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Bagner DM, Johns NB, Baumeister AL, Goodman WK, et al. Reliability and validity of the child behavior checklist obsessive-compulsive scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:473–85. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Storch EA, Park JM, Lewin AB, Morgan JR, Jones AM, Murphy TK, et al. The leyton obsessional inventory-child version survey form does not demonstrate adequate psychometric properties in American youth with pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:574–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Rosario MC, Pittenger C, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis of the symptom structure of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1532–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacob ML, Storch EA. Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review for nursing professionals. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;26:138–48. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eisen JL, Rasmussen SA, Phillips KA, Price LH, Davidson J, Lydiard RB, et al. Insight and treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:494–7. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.27898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Catapano F, Perris F, Fabrazzo M, Cioffi V, Giacco D, De Santis V, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: A three-year prospective study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alfano CA, Kim KL. Objective sleep patterns and severity of symptoms in pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder: A pilot investigation. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:835–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jaspers-Fayer F, Lin SY, Belschner L, Mah J, Chan E, Bleakley C, et al. A case-control study of sleep disturbances in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2018;55:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Snyder HR, Kaiser RH, Warren SL, Heller W. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is associated with broad impairments in executive function: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3:301–30. doi: 10.1177/2167702614534210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cavedini P, Zorzi C, Piccinni M, Cavallini MC, Bellodi L. Executive dysfunctions in obsessive-compulsive patients and unaffected relatives: Searching for a new intermediate phenotype. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brennan E, Flessner C. An interrogation of cognitive findings in pediatric obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;227:135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stewart SE, Negreiros J, Belschner L, Lin S. Neurocognition in pediatric obessive-compulsive disorder: Clinical impacts and future considerations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:S291. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geller DA, Abramovitch A, Mittelman A, Stark A, Ramsey K, Cooperman A, et al. Neurocognitive function in paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19:142–51. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1282173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jaafari N, Fernández de la Cruz L, Grau M, Knowles E, Radua J, Wooderson S, et al. Neurological soft signs in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Two empirical studies and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1069–79. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tapancı Z, Yıldırım A, Boysan M. Neurological soft signs, dissociation and alexithymia in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and healthy subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2018;260:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hollander E, Kaplan A, Schmeidler J, Yang H, Li D, Koran LM, et al. Neurological soft signs as predictors of treatment response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:472–7. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bloch MH, Sukhodolsky DG, Dombrowski PA, Panza KE, Craiglow BG, Landeros-Weisenberger A, et al. Poor fine-motor and visuospatial skills predict persistence of pediatric-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder into adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:974–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Storch EA, Small BJ, McGuire JF, Murphy TK, Wilhelm S, Geller DA, et al. Quality of life in children and youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28:104–10. doi: 10.1089/cap.2017.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Keller M, McCracken J. Functional impairment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(Suppl 1):S61–9. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Negreiros J, Belschner L, Selles RR, Lin S, Stewart SE. Academic skills in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A preliminary study. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30:185–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lebowitz ER, Vitulano LA, Omer H. Coercive and disruptive behaviors in pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder: A qualitative analysis. Psychiatry. 2011;74:362–71. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2011.74.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stewart SE, Hu YP, Hezel DM, Proujansky R, Lamstein A, Walsh C, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the OCD family functioning (OFF) scale. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25:434–43. doi: 10.1037/a0023735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stewart SE, Beresin C, Haddad S, Egan Stack D, Fama J, Jenike M, et al. Predictors of family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20:65–70. doi: 10.1080/10401230802017043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lebowitz ER, Panza KE, Su J, Bloch MH. Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12:229–38. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stewart SE, Hu YP, Leung A, Chan E, Hezel D, Lin SY, et al. A Multi-Site Study of Family Functioning Impairment in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Am Acad of Child and Adoles Psychiatry. 2017;56:241–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brauer L, Lewin AB, Storch EA. Evidence-based treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48:280–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Geller D, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Frazier J, Coffey BJ, Kim G, et al. Clinical correlates of obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents referred to specialized and non-specialized clinical settings. Depress Anxiety. 2000;11:163–8. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<163::AID-DA3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leckman JF, King RA, Gilbert DL, Coffey BJ, Singer HS, Dure LS, 4th, et al. Streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and exacerbations of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:108–18.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fernández de la Cruz L, Rydell M, Runeson B, D’Onofrio BM, Brander G, Rück C, et al. Suicide in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A population-based study of 36 788 Swedish patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1626–32. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Watson HJ, Rees CS. Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled treatment trials for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:489–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Witthauer C, T Gloster A, Meyer AH, Lieb R. Physical diseases among persons with obsessive compulsive symptoms and disorder: A general population study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:2013–22. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0895-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mataix-Cols D, Frans E, Pérez-Vigil A, Kuja-Halkola R, Gromark C, Isomura K, et al. A total-population multigenerational family clustering study of autoimmune diseases in obsessive-compulsive disorder and tourette's/chronic tic disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1652–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bright PD, Mayosi BM, Martin WJ. An immunological perspective on rheumatic heart disease pathogenesis: More questions than answers. Heart. 2016;102:1527–32. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Geller DA, March JS for the AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.GPediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric OCD treatment study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1969–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.O’Kearney R. Benefits of cognitive-behavioural therapy for children and youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Re-examination of the evidence. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:199–212. doi: 10.1080/00048670601172707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ivarsson T, Skarphedinsson G, Kornør H, Axelsdottir B, Biedilæ S, Heyman I, et al. The place of and evidence for serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in children and adolescents: Views based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2015;227:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, Khanna M, Compton S, Almirall D, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric OCD treatment study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1224–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.March JS, Franklin ME, Leonard H, Garcia A, Moore P, Freeman J, et al. Tics moderate treatment outcome with sertraline but not cognitive-behavior therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:344–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Torp NC, Dahl K, Skarphedinsson G, Compton S, Thomsen PH, Weidle B, et al. Predictors associated with improved cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:200–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chu BC, Colognori DB, Yang G, Xie MG, Lindsey Bergman R, Piacentini J, et al. Mediators of exposure therapy for youth obsessive-compulsive disorder: Specificity and temporal sequence of client and treatment factors. Behav Ther. 2015;46:395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Abramovitch A, Dar R, Mittelman A, Wilhelm S. Comorbidity between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder across the lifespan: A systematic and critical review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:245–62. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Andrighetti H, Semaka A, Stewart SE, Shuman C, Hayeems R, Austin J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: The process of parental adaptation and implications for genetic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:912–22. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9914-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rosa-Alcázar AI, Sánchez-Meca J, Rosa-Alcázar Á, Iniesta-Sepúlveda M, Olivares-Rodríguez J, Parada-Navas JL, et al. Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Span J Psychol. 2015;18:E20. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2015.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Krebs G, Isomura K, Lang K, Jassi A, Heyman I, Diamond H, et al. How resistant is ‘treatment-resistant’ obsessive-compulsive disorder in youth? Br J Clin Psychol. 2015;54:63–75. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Turner CM. Cognitive-behavioural theory and therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: Current status and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:912–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Coyne LW, McHugh L, Martinez ER. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Advances and applications with children, adolescents, and families. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20:379–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bluett EJ, Homan KJ, Morrison KL, Levin ME, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety and OCD spectrum disorders: An empirical review. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:612–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, Compton S, Khanna M, Flessner C, et al. Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment study for young children (POTS jr) – A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:689–98. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Storch EA, Caporino NE, Morgan JR, Lewin AB, Rojas A, Brauer L, et al. Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Selles RR, Belschner L, Negreiros J, Lin S, Schuberth D, McKenney K, et al. Group family-based cognitive behavioral therapy for pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder: Global outcomes and predictors of improvement. Psychiatry Res. 2018;260:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Thompson-Hollands J, Abramovitch A, Tompson MC, Barlow DH. A randomized clinical trial of a brief family intervention to reduce accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A preliminary study. Behav Ther. 2015;46:218–29. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, Mullin B, Martin A, Spencer T, et al. Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1919–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krebs G, Heyman I. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:495–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alaghband-Rad J, Hakimshooshtary M. A randomized controlled clinical trial of citalopram versus fluoxetine in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:131–5. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0634-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Murphy TK, Segarra A, Storch EA, Goodman WK. SSRI adverse events: How to monitor and manage. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:203–8. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gibbons RD, Coca Perraillon M, Hur K, Conti RM, Valuck RJ, Brent DA, et al. Antidepressant treatment and suicide attempts and self-inflicted injury in children and adolescents. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:208–14. doi: 10.1002/pds.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cousins L, Goodyer IM. Antidepressants and the adolescent brain. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:545–55. doi: 10.1177/0269881115573542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bloch MH, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF, Pittenger C. Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:850–5. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]