Abstract

Island systems provide excellent arenas to test evolutionary hypotheses pertaining to gene flow and diversification of dispersal-limited organisms. Here we focus on an orbweaver spider genus Cyrtognatha (Tetragnathidae) from the Caribbean, with the aims to reconstruct its evolutionary history, examine its biogeographic history in the archipelago, and to estimate the timing and route of Caribbean colonization. Specifically, we test if Cyrtognatha biogeographic history is consistent with an ancient vicariant scenario (the GAARlandia landbridge hypothesis) or overwater dispersal. We reconstructed a species level phylogeny based on one mitochondrial (COI) and one nuclear (28S) marker. We then used this topology to constrain a time-calibrated mtDNA phylogeny, for subsequent biogeographical analyses in BioGeoBEARS of over 100 originally sampled Cyrtognatha individuals, using models with and without a founder event parameter. Our results suggest a radiation of Caribbean Cyrtognatha, containing 11 to 14 species that are exclusively single island endemics. Although biogeographic reconstructions cannot refute a vicariant origin of the Caribbean clade, possibly an artifact of sparse outgroup availability, they indicate timing of colonization that is much too recent for GAARlandia to have played a role. Instead, an overwater colonization to the Caribbean in mid-Miocene better explains the data. From Hispaniola, Cyrtognatha subsequently dispersed to, and diversified on, the other islands of the Greater, and Lesser Antilles. Within the constraints of our island system and data, a model that omits the founder event parameter from biogeographic analysis is less suitable than the equivalent model with a founder event.

Introduction

Island biogeography is concerned with colonization and diversification of organisms on islands, including empirical tests of evolutionary hypotheses pertaining to gene flow in dispersal-limited organisms1,2. Islands are geographically widespread and diverse, and vary in shapes and sizes, age and geologic origins, and show different degrees of isolation3. Darwin already recognized that this combination of attributes makes islands appealing objects of scientific study4. Modern biogeography recognizes the interplay among island histories, the specifics of their geography, and various attributes of organisms that inhabit them5.

Amongst island systems some of the best studied in terms of biogeographic research are Hawaii6–8, Galapagos9–11, Azores12–14, Canary15–17 and Solomon18–20 islands, as well as large continental fragments such as Madagascar21–23 and New Zealand24–26. However, the Caribbean island system27–30 is the single most ‘published’ island system in biogeography literature (Google Scholar title hits 237 compared with 195 for the second, New Zealand). The Caribbean Basin, also known as West Indies, lies in the tropical zone between South and North American continents, and to the east of the Gulf of Mexico. Combining over 700 islands, the Caribbean is considered among the world’s biodiversity hotspots31–33. In its most broad categorization, the Caribbean comprises three regions: (1) Greater Antilles with the largest islands of Cuba, Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti), Puerto Rico and Jamaica representing 90% of all land in Caribbean Sea; (2) Lesser Antilles with numerous smaller, mostly volcanic, islands and (3) the Lucayan platform archipelago (the Bahamas).

The Greater Antillean islands of Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico, but not Jamaica, are parts of the old proto-Antillean arc that began its formation over 130 million years ago (MYA). Through Caribbean plate tectonics, the proto-Antillean arc drifted eastward until settling at its current location around 58 MYA34,35. Researchers disagree on the timing of the proto-Antillean arc connection with South or North America in the Cretaceous or even on the existence of such a connection. However, that distant past may have had little biological relevance for current biotas due to a catastrophic effect of the bolide that crashed into Yucatan around 65 MYA which arthropods would likely not have survived36–38. The emergence of the Greater Antilles as relevant biogeographic units is therefore more recent. Various studies estimate that earliest contiguous permanent dry land on the Greater Antilles has existed since the middle Eocene, approximately 40 MYA38–42.

Although it may be possible that the Greater Antilles have remained isolated from continental landmasses since the early Cenozoic, a hypothesized land bridge potentially existed around 35–33 MYA38,43. This land bridge, known as GAARlandia (Greater Antilles – Aves Ridge), is hypothesized to have connected the Greater Antilles with the South American continent for about 2 million years, due to a sea level drop and subsequent exposure of land at Aves Ridge. As a means of biotic evolution on the Greater Antilles, the GAARlandia hypothesis allows for a combination of overland dispersal and subsequent vicariance and can be tested with the help of time calibrated phylogenies and fossils. While patterns of relationships that are consistent with predictions based on GAARlandia have been found in some lineages44–48 it is not a good model for explaining the biogeographical history of others27,29,49,50.

Among the islands forming the Greater Antilles, Jamaica is a geological special case since it was originally a part of the Central American tectonic plate. Jamaica emerged as an island around 40 MYA but remained partially or fully submerged until its reemergence in mid-Miocene around 15 MYA30,51–53, and was never part of the hypothetical GAARlandia landbridge. Consequently, Jamaica’s biota is distinct from other regions of Greater Antilles54.

The Lesser Antilles formed more recently. Northward of Guadalupe they split into two arches of distinct origins. The older, outer arc formed volcanically in Eocene-Oligocene, but its islands are largely composed of limestone signifying that they were submerged and have undergone orogenic uplift since the Miocene. The Lesser Antilles’ inner arc is of more recent volcanic origin (<10 MYA) and its islands continue to be formed55–59. With no history of continental connection, most of the Lesser Antilles have been completely isolated for at least a few million years, and thus their biotas must have originated via overwater dispersal30,60,61.

Spiders and other arachnids are emerging as model organisms for researching biogeography of the Caribbean27,44,48,62–64. Spiders are globally distributed and hyperdiverse (~47,000 described of roughly 100,000 estimated species65,66) organisms that vary greatly in size, morphology and behavior, habitat specificity, and importantly, in their dispersal biology67–69. While some spiders show good active dispersal70, others are limited in their cursorial activities but exhibit varying passive dispersal potential. Many species are able to passively drift on air currents with behavior called ballooning67,71 to colonize new areas. Some genera of spiders, like Tetragnatha or Nephila are known to easily cross geographic barriers, disperse large distances, and are one of the first colonizers of newly formed islands72–74. These are considered to be excellent aerial dispersers, while other lineages are not as successful. For example, the primitively segmented spiders, family Liphistiidae and the mygalomorph trapdoor spiders, likely do not balloon and have highly sedentary lifestyle imposing strict limits on their dispersal potential. As a consequence, bodies of sea water or even rivers represent barriers that limit their gene flow, which leads to micro-allopatric speciation75–80. Unlike the above clear-cut examples, the dispersal biology of most spider lineages is unknown, and their biogeographic patterns poorly understood.

This research focuses on the tetragnathid spider genus Cyrtognatha and its biogeography in the Caribbean. Cyrtognatha is distributed from Argentina to southern Mexico and the Caribbean65,81. A recent revision recognized 21 species of Cyrtognatha but cautioned that only a fraction of its diversity is known82. Its biology is poorly understood as these spiders are rarely collected and studied (a single Google scholar title hit vs 187 title hits for Tetragnatha). Considering their phylogenetic proximity to Tetragnatha, as well as its described web architecture, it seems likely that Cyrtognatha species disperse by ballooning83–85. Through an intensive inventory of Caribbean arachnids, we obtained a rich original sample of Cyrtognatha that allows for the first reconstruction of their biogeographic history in the Caribbean. We use molecular phylogenies to reconstruct Cyrtognatha evolutionary history with particular reference to the Caribbean, and compare estimates of clade ages with geological history of the islands. We use this combined evidence to test the vicariant versus dispersal explanations of Caribbean colonization, and to look for a broad agreement of Cyrtognatha biogeographic patterns with the GAARlandia landbridge hypothesis. We also greatly expand our understanding of Cyrtognatha diversity in the Caribbean region.

Materials and Methods

Field collection and identification

Material for our research was collected as a part of a large-scale Caribbean Biogeography (CarBio) project. Extensive sampling was conducted across Caribbean islands and in Mexico, using visual aerial search (day and night), and beating66,86. Collected material was fixed in 96% ethanol and stored at −20/−80 °C until DNA extraction. Species identification was often impossible due to juvenile individuals or lack of match with the described species (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detailed information on Cyrtognatha specimens and outgroups.

| Genus | Species/MOTU | Voucher code | Location | Lat. | Lon. | COI accession number | 28S accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392873 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924072 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392894 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924073 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392865 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924071 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392845 | Puerto Rico | 18.17213 | −65.77074 | MH924069 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392808 | Puerto Rico | 18.28925 | −65.77877 | MH924066 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392813 | Puerto Rico | 18.28925 | −65.77877 | MH924067 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392764 | Puerto Rico | 18.28925 | −65.77877 | MH924065 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392745 | Puerto Rico | 18.28925 | −65.77877 | MH924063 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392732 | Puerto Rico | 18.28925 | −65.77877 | MH924062 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392911 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924074 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392843 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924068 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392763 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924064 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00392853 | Puerto Rico | 18.29574 | −65.79065 | MH924070 | |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00782105 | Puerto Rico | 18.17326 | −66.59015 | MH924075 | MH924140 |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00782116 | Puerto Rico | 18.17326 | −66.59015 | MH924077 | MH924141 |

| Cyrtognatha | elyunquensis | 00782110 | Puerto Rico | 18.17326 | −66.59015 | MH924076 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782473 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924028 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782595 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924036 | MH924135 |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782517 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924032 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782495 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924029 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782505 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924030 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782511 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924031 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785757 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924047 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00784817 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924039 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00784739 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924038 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785433 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924040 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785697 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924044 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782558 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924034 | MH924134 |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785592 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924042 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785705 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924045 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785514 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924041 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782583 | Hispaniola | 19.07796 | −69.46635 | MH924035 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00782543 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924033 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785737 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924046 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00785647 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −070.111 | MH924043 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00787109 | Hispaniola | 19.03627 | −70.54337 | MH924048 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00787194 | Hispaniola | 19.03627 | −70.54337 | MH924050 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00787211 | Hispaniola | 19.03627 | −70.54337 | MH924051 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00787181 | Hispaniola | 19.03627 | −70.54337 | MH924049 | |

| Cyrtognatha | espanola | 00784482 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924037 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP1 | 00001244 A | Guadeloupe | 16.04208 | −061.63816 | MH924053 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP1 | 00001272 A | Guadeloupe | 16.04208 | −061.63816 | MH924054 | MH924138 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP1 | 00001314 A | Guadeloupe | 16.04208 | −061.63816 | MH924055 | MH924139 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP1 | 00001319 A | Guadeloupe | 16.04208 | −061.63816 | MH924056 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP1 | 00001325 A | Guadeloupe | 16.04208 | −61.63816 | MH924057 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2 | 00787050 | Hispaniola | N/A | N/A | MH924082 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2 | 00787032 | Hispaniola | N/A | N/A | MH924080 | MH924143 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2 | 00787053 | Hispaniola | N/A | N/A | MH924083 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2 | 00787040 | Hispaniola | N/A | N/A | MH924081 | MH924144 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2 | 00787095 | Hispaniola | 19.03750 | −70.96918 | MH924084 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2B | 00786963 | Hispaniola | 18.82208 | −070.6838 | MH924079 | MH924142 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP2C | 00784541 | Hispaniola | 18.09786 | −71.18925 | MH924078 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00002436 A | Jamaica | 18.04833 | −76.61814 | MH924086 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00003042 A | Jamaica | 18.04833 | −76.61814 | MH924090 | MH924145 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00003025 A | Jamaica | 18.04833 | −76.61814 | MH924089 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00002399 A | Jamaica | 18.04833 | −76.61814 | MH924085 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00002589 A | Jamaica | 18.04833 | −76.61814 | MH924087 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00002990 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924088 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004283 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924100 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004492 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924112 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004414 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924106 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004313 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924103 | MH924146 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004384 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924105 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00003825 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924092 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00003822 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924091 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004474 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924111 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004456 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924109 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004029 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924094 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004432 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924107 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004294 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924101 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004170 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924096 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004335 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924104 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004444 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924108 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004206 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924098 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004209 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924099 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004202 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924097 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004462 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924110 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004310 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924102 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004010 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924093 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP4 | 00004136 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924095 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP5 | 00003183 A | Jamaica | 18.34769 | −77.64158 | MH924114 | MH924148 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP5 | 00002964 A | Jamaica | 18.34769 | −77.64158 | MH924113 | MH924147 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP6 | 00003815 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924116 | MH924150 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP6 | 00003173 A | Jamaica | 18.05350 | −76.59950 | MH924115 | MH924149 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00782814 | Cuba | 20.01309 | −76.83400 | MH924120 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00782885 | Cuba | 20.01309 | −76.83400 | MH924121 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00782894 | Cuba | 20.01309 | −76.83400 | MH924122 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00000564 A | Cuba | 20.31504 | −76.55337 | MH924119 | MH924152 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00000232 A | Cuba | 20.31504 | −76.55337 | MH924117 | MH924151 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00000317 A | Cuba | 20.31504 | −76.55337 | MH924118 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP7 | 00784348 | Cuba | 20.00939 | −76.89402 | MH924123 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00784418 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924124 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00784494 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924125 | MH924153 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00787280 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924129 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00784608 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924126 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00787174 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924127 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP8 | 00787178 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924128 | MH924154 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP10 | 00001639 A | Grenada | 12.09501 | −61.69500 | MH924058 | MH924137 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP10 | 00001673 A | Grenada | 12.09501 | −61.69500 | MH924059 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP10 | 00001688 A | Grenada | 12.09501 | −61.69500 | MH924060 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP10 | 00001792 A | Grenada | 12.09501 | −61.69500 | MH924061 | |

| Cyrtognatha | SP10B | 00001680 A | Saint Lucia | 13.96448 | −60.94473 | MH924130 | MH924155 |

| Cyrtognatha | SP12 | 00787269 | Hispaniola | 19.05116 | −70.88866 | MH924052 | MH924136 |

| Cyrtognatha | atopica GB | N/A | Argentina | N/A | N/A | GU129638 | |

| Cyrtognatha | sp. GB | N/A | Hispaniola | N/A | N/A | KY017951 | |

| Cyrtognatha | sp. GB | N/A | Panama | N/A | N/A | GU129630 | GU129609 |

| Cyrtognatha | sp. GB | N/A | Panama | N/A | N/A | GU129629 | |

| Arkys | cornutus GB | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | FJ607556 | KY016938 |

| Chrysometa | linguiformis | 00784514 | Cuba | 22.56010 | −83.83318 | MH924027 | MH924133 |

| Leucauge | argyra | 00782551 | Hispaniola | 19.35504 | −70.11100 | MH924131 | MH924156 |

| Metellina | mengei GB | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | KY269213 | |

| Pachygnatha | degeeri GB | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | KY268868 | |

| Tetragnatha | elongata | 00001397 A | Florida, USA | 29.61958 | −82.30660 | MH924132 | MH924157 |

Molecular procedures

DNA isolation took place at University of Vermont (Vermont, USA; UVM) using QIAGEN DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA), at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC using an Autogenprep965 for an automated phenol chloroform extraction, and at EZ Lab (Ljubljana, Slovenia). The latter protocol involved robotic DNA extraction using Mag MAX™ Express magnetic particle processor Type 700 with DNA Multisample kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and following modified protocols87 (Vidergar, Toplak & Kuntner, 2014).

We targeted two genetic markers: (1) the standard Cytochrome C oxidase subunit 1 (COI) barcoding region, which has repeatedly been shown to be taxonomically informative in species delimitation88,89; and (2) the nuclear 28S gene for a subset of terminals representing all sampled species. We used the forward LCO1490 (GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG)90 and the reverse C1-N-2776 (GGATAATCAGAATATCGTCGAGG)91 for COI amplification. The standard reaction volume was 25 µL containing 5 µL of Promega’s GoTaq Flexi Buffer and 0.15 µL of GoTaq Flexi Polymerase, 0.5 µL dNTP’s (2 mM each, Biotools), 2.3 µL MgCl2 (25 mM, Promega), 0.5 µL of each primer (20 µM), 0.15 µL BSA (10 mg/mL; Promega), 2 µL DNA template and the rest was sterile distilled water. We used the following PCR cycling protocol: an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 94 °C followed by 20 touch-up method cycles of 60 s at 94 °C, 90 s at 44°→ 54 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, followed by 15 cycles of 90 s at 94 °C, 90 s at 53.5 °C, 60 s at 72 °C and the final extension period of 7 min at 72 °C.

The primer pair for 28S were the forward 28Sa (also known as 28S-D3A; GACCCGTCTTGAAACACGGA)92 and the reverse 28S-rD5b (CCACAGCGCCAGTTCTGCTTAC)93. The standard reaction volume was 35 µL containing 7.1 µL of Promega’s GoTaq Flexi Buffer and 0.2 µL of GoTaq Flexi Polymerase, 2.9 µL dNTP’s (2 mM each, Biotools), 3.2 µL MgCl2 (25 mM, Promega), 0.7 µL of each primer (20 µM), 0.2 µL BSA (10 mg/mL; Promega), 1 µL DNA template and the rest was sterile distilled water. We used the following PCR cycling protocol: an initial denaturation step of 7 min at 96 °C followed by 20 touch-down method cycles of 45 s at 96 °C, 45 s at 62 °C → 52 °C, 60 s at 72 °C, followed by 15 cycles of 45 s at 96 °C, 45 s at 52 °C, 60 s at 72 °C and the final extension period of 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were purified and sequenced at Macrogen (Amsterdam, NL).

We used Geneious v. 5.6.794 for sequence assembly, editing and proofreading. For alignment, we used the default settings and the automatic optimization option in the online version of MAFFT95. We concatenated the COI and 28S matrices in Mesquite96.

We obtained 103 original Cyrtognatha COI sequences and mined four additional Cyrtognatha COI sequences from GenBank (Table 1). We excluded a single sequence, representing Argentinian C. atopica (GU129638), from most analysis, due to its poor quality, as already discussed by Dimitrov and Hormiga97. Moreover, we added three COI sequences from GenBank (Arkys cornutus, Metellina mengei, Pachygnatha degeeri) and three original COI sequences (Leucauge argyra, Chrysometa linguiformis, Tetragnatha elongata) to be used as outgroups. We obtained 22 original sequences of 28S gene fragment representing all putative species of Cyrtognatha and included one from GenBank. Additionally, we incorporated three original 28S sequences (Leucauge argyra, Chrysometa linguiformis, Tetragnatha elongata) and a single one from GenBank (Arkys cornutus) to be used as outgroups (Table 1). The concatenated matrix contained 1244 nucleotides (663 for COI and 581 for 28S).

Species delimitation

Because the current taxonomy of Cyrtognatha based on morphology is highly incomplete82, we undertook species delimitation using COI data. To estimate molecular taxonomic operational units (MOTUs), we used four different species delimitation methods, each with its online application: PTP (Poisson tree process)98, mPTP (multi-rate Poisson tree process)99, GMYC (generalized mixed yule coalescent)100 and ABGD (automatic barcode gap discovery)101. We ran these species delimitation analyses using the default settings, with the input tree for GYMC from BEAST2102 and the input trees for PTP and mPTP from MEGA 6.0103.

Phylogenetic analyses

We used MrBayes104 to reconstruct an all-terminal phylogeny for a complete set of our original Cyrtognatha material and outgroups using COI (Table 1). For Bayesian analysis we used the Generalised time-reversible model with gamma distribution and invariant sites (GTR + G + I) as suggested by AIC and BIC criterion in jModelTest2105. We ran two independent runs, each with four MCMC chains, for 100 million generations, with a sampling frequency of 1000 and relative burn-in set to 25%. The starting tree was random.

For a species level phylogeny, we then selected two individuals per MOTU and added 28S sequence data for two partitions and analyzed this concatenated dataset under a Bayesian framework. As above, jModelTest2 suggested GTR + G + I as the appropriate model, this time for both partitions. These analyses had 28 terminals including outgroups (Table 1). The settings in MrBayes were as above, but the number of MCMC generations was set to 30 million. Due to high mutation rates in noncoding parts of nuclear genes like 28S, insertions and deletions accumulate through evolution106,107, resulting in numerous gaps in a sequence alignment. We treated gaps as missing data but also ran additional analyses applying simple gap coding with FastGap108.

Molecular dating analyses

We used BEAST2102 for time calibrated phylogeny reconstruction (chronogram) constrained based on the results from the above described species level phylogeny. We used a single COI sequence per MOTU and trimmed the sequences to approximately equal lengths. We then modified the xml file in BEAUti102 to run three different analyses. The first analysis was run using GTR + G + I as suggested by jModelTest2. The second analysis employed the package and model bModelTest109. The third analysis used the package and RBS model110. All parameters were set to be estimated by BEAST. We used a Stepping-Stone Sampling (SS) approach, implemented as Model_Selection 1.4.1 extension in BEAST2, to calculate marginal likelihoods of models employing either strict or relaxed molecular clock (see Supplementary Note S2 for details and Baele et al.111,112 for justification). We then performed likelihood ratio test (LRT) and Bayes Factor test (BF), using calculated marginal likelihood scores and discovered that a relaxed log normal clock model better fits our data (LTR: p < 0.001; logBF = 27.1). Following Bidegaray-Batista and Arnedo113 we set ucld.mean prior as normally distributed with mean value of 0.0112 and standard deviation of 0.001, and the ucld.stdev as exponentially distributed with the mean of 0.666. We ran an additional analysis using a fossil calibration point on the basal node of Caribbean Cyrtognatha clade. Cyrtognatha weitschati, known from Dominican amber of Hispaniola, is hypothesized to be 13.65–20.41 million years old. We used an exponential prior with 95% confidence interval spanning from a hard lower bound at 13.65 MYA to the soft upper bound at 41 MYA. This upper bound corresponds with the time of Hispaniola appearance. We used SS sampling approach to calculate marginal likelihood scores for models with either a Yule or a Birth-Death tree prior (Supplementary Note S2). As suggested by the results of LRT (p < 0.001) and BF (logBF = 21.4) tests on those two models, we opted for a Yule process as a tree prior. The trees were summarized with TreeAnnotator102, with 20% burn-in based on a Tracer114 analysis, target tree set as Maximum clade credibility tree and node heights as median heights.

All metafiles from BEAST and MrBayes were evaluated in Tracer to determine burn-in, to examine ESS values and to check for chain convergence. For visualization of trees we used FigTree115. All MrBayes and BEAST analyses were run on CIPRES portal116.

Ancestral area estimation

We used BioGeoBEARS117 in R version 3.5.0118 to estimate ancestral range of Cyrtognatha in the Caribbean. We used a BEAST produced ultrametric tree from the above described molecular dating analysis as an input. We removed the outgroup Tetragnatha elongata and conducted the analyses with the 13 Cyrtognatha MOTUs from six areas (Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Lesser Antilles and Panama). We estimated the ancestral range of species with all models implemented in BioGeoBEARS: DEC (+J), DIVALIKE (+J) and BAYAREALIKE (+J). We used log-likelihoods (LnL) with Akaike information criterion (AIC) and sample-size corrected AIC (AICc) scores to test each model’s suitability for our data. All of our Cyrtognatha’s MOTUs are single island endemics, therefore we were able to reduce the parameter “max_range_size” to two29,119,120.

Results

We collected 103 Cyrtognatha individuals from Cuba, Jamaica, Dominican Republic/Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and Lesser Antilles (Fig. 1, Table 1). We confirmed that all individuals are morphologically Cyrtognatha, although we were not able to identify most species. However, we did identifiy two known species: C. espanola (Bryant, 1945) and C. elyunquensis (Petrunkevitch, 1930), the latter, clearly a Cyrtognatha, was previously placed in Tetragnatha and not transferred to Cyrtognatha in the recent revision of the genus65. The CarBio collections from Mexico yielded no Cyrtognatha specimens.

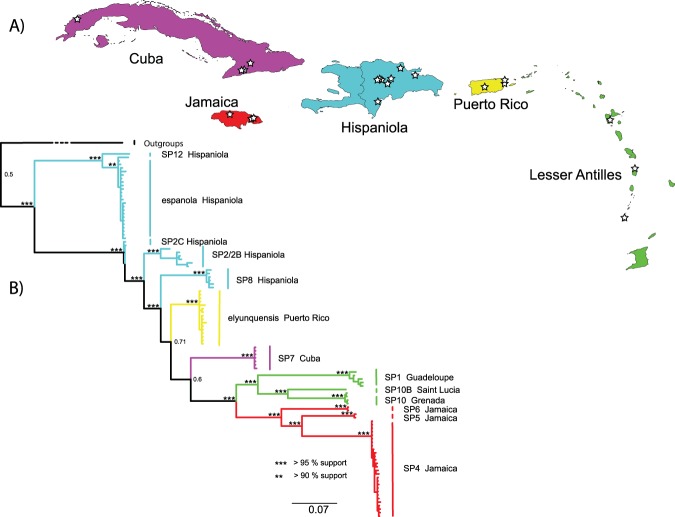

Figure 1.

(A) Map of the Caribbean with indicated sampling localities. (B) The all-terminal mitochondrial Bayesian phylogeny of Cyrtognatha. Branch colors match those of the islands in A. Notice that all putative species form exclusively single island endemic pattern.

We obtained COI sequences for all Cyrtognatha individuals. Using computational methods for species delimitation our Cyrtognatha dataset is estimated to contain from 11 to 14 MOTUs (Supplementary Note S1). The results from PTP, mPTP and ABGD were mostly consistent, disagreeing only on the status of three putative species. To these species that are supported by some but not all analyses, we added the label B or C after the species name: Cyrtognatha SP10B, Cyrtognatha SP2B and Cyrtognatha SP2C. On the other hand, we dismiss the results from GMYC analyses using either a single versus multiple threshold option, which failed to recover reliable MOTUs. The composition of our dataset is most likely not compatible with GMYC method as it cannot detect switches between inter- and intraspecific branching patterns, offering us from 1 to 39 MOTUs.

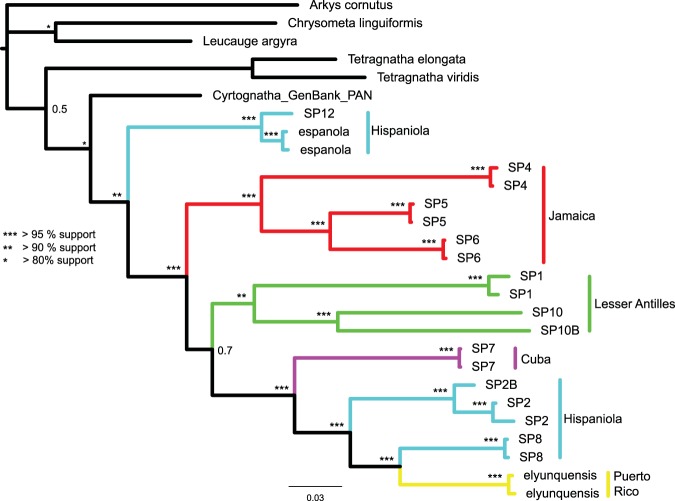

The two gene and the all-terminal, COI, phylogenies yielded nearly identical networks both supporting the monophyly of the Caribbean taxa. However, the root placement in the mtDNA phylogeny is different such that the phylogenetic trees appear to be in strong conflict even though the phylogenetic networks are mostly congruent (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1). Given that stronger evidence for root placement is expected to come from the two gene phylogeny, we ran an additional analysis constraining the root of the mtDNA phylogeny to reflect that, with otherwise the same settings (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S2). Our all-terminal Bayesian phylogeny supports Caribbean Cyrtognatha monophyly, albeit with only three non-Caribbean samples. Most terminal clades were well supported with lower supports for some deeper nodes (Supplementary Fig. S1). This phylogeny strongly recovers all putative species groups as single island endemics. Furthermore, all geographic areas harbor monophyletic lineages, with the exception of Hispaniola that supports two independent clades. The unconstrained all-terminal COI phylogeny recovers the Lesser Antillean clade as sister to all other Caribbean taxa. However, this relationship is not recapitulated in the concatenated, species level, phylogeny (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S3). The concatenated phylogeny also supports monophyly of the Caribbean taxa but recovers the clade of C. espanola and C. SP12 from Hispaniola as sister to all other Caribbean Cyrtognatha. The species level phylogeny is generally better supported, with the exception of a clade uniting species from Lesser Antilles, Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. In both Bayesian analyses the chains successfully converged and ESS as well as PRSF values of summarized MCMC runs parameters were appropriate104.

Figure 2.

Species level Bayesian phylogeny of Cyrtognatha based on COI and 28S. Relationships agree with Cyrtognatha and Caribbean Cyrtognatha monophyly.

Chronograms produced by BEAST, using either exclusively COI mutation rate or incorporating the additional fossil for time calibration, exhibited very similar time estimates (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S5). We decided to proceed with the mutation rate-only calibrated phylogeny for further analyses because it is less likely to contain known potential biases when calibrating with scarcely available fossils and geological information121,122. The molecular dating analyses based on the three different models in BEAST largely agreed on node ages with less than 1 million years variation. However, the log files from the chronogram based on GTR + G + I model consistently exhibited low ESS values (<50), even with MCMC number of generations having been increased to 200 million. The analyses using the remaining models, RBS and bModelTest, were more appropriate since MCMC chains successfully converged, and the lowest ESS values were 981 and 2214 respectively, thus far exceeding the suggested 200. Additional examination of the log files produced by bModelTest phylogeny with bModelAnalyzer from AppStore.exe109 revealed that MCMC chains spent most time in modified TN93 model with the code 123143 which contributed for 49.56% of posterior probability (for details on bModelTest method of model selection see109). The BEAST chronogram using bModelTest (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S4) yielded the best supported results, amongst the above mentioned approaches, based on ESS values, and was therefore used in subsequent biogeographical analyses. This chronogram (Fig. 3) supports a scenario in which Cyrtognatha diverged from the closely related genus Tetragnatha at 18.7 MYA (95% HDP: 12.8–26.7 MYA). The Caribbean clade is estimated to have split from the mainland Cyrtognatha (represented here by a species from Panama) 15.0 MYA (95% HDP: 10.5–20.7 MYA). The clade with lineages represented on Lesser Antilles diverged from those on Greater Antilles at 11.5 MYA (95% HDP: 8.3–15.6 MYA).

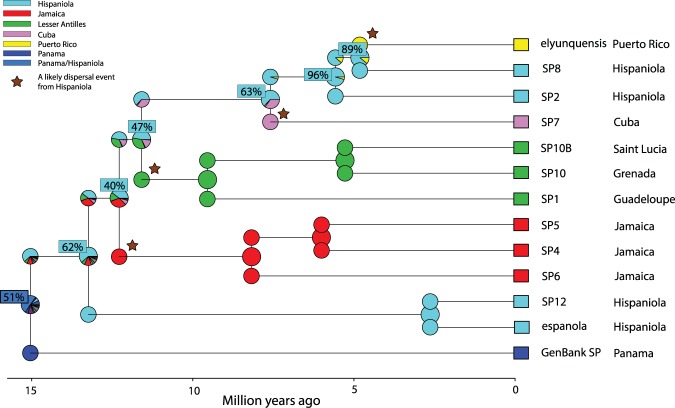

Figure 3.

Time-calibrated BEAST phylogeny of Cyrtognatha. This chronogram suggests Cyrtognatha colonized the Caribbean in mid-Miocene and refutes ancient vicariant scenarios. The lack of any land bridge connection of the Caribbean with mainland at least since early Oligocene (cca. 33 MYA; GAARlandia) suggests that colonization happened by overwater dispersal. Confidence intervals of clade ages agree with geological history of Caribbean islands.

The comparison of all six models of ancestral area estimation with BioGeoBEARS recovered DIVALIKE + J as most suitable for our data due to highest LnL scores in all tests (Supplementary Table S1). The estimation of ancestral states suggests that the most recent common ancestor of all Caribbean Cyrtognatha in our dataset most likely (62%) resided on Hispaniola (Fig. 4). Moreover, all the Greater Antillean island clades as well as the Lesser Antillean clade most likely originated from Hispaniola with the following probability: Jamaican clade (47%), Lesser Antillean clade (40%), Cuban clade (63%) and Puerto Rican clade (89%) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 4.

Ancestral area estimation of Cyrtognatha with BioGeoBEARS. The biogeographical analysis, using the most suitable model for our data (DIVALIKE + J, max_range_size = 2), revealed that Hispaniola was most likely colonized first. Following colonization, Cyrtognatha diversified within Hispaniola and subsequently dispersed from there to all other islands of the Caribbean (stars).

Recently, Ree and Sanmartin123 identified certain biases in the selection of those models that employ the founder event (the +J variants of the models in BioGeoBEARS). We followed their concerns and also analyzed the data using the DIVALIKE model that omits the founder event117. These alternative results (Supplementary Fig. S6) differ from those above in detecting an exclusively vicariant cladogenetic set of events. As we discuss below these alternative results are less credible in the context of Caribbean geological history, as the putative vicariant events are too recent.

Discussion

We reconstruct the first Cyrtognatha phylogeny using molecular data from over 100 individuals of this rarely collected group. Our results support Cyrtognatha as a relatively young clade, having diverged from a common ancestor with its possible sister genus Tetragnatha, in early- to mid-Miocene, and colonized the Caribbean in mid-Miocene. As we discuss below, these estimated ages, combined with the phylogenetic patterns, refute ancient vicariant explanations of their Caribbean origin, including the GAARlandia hypothesis. Instead, the patterns suggest colonization of Hispaniola, and subsequent dispersal to other islands.

The all-terminal phylogeny (Fig. 1) reveals clear patterns of exclusively single island endemic (SIE) species. This holds true even for the three MOTUs on the Lesser Antilles island group, as they appear on Guadelupe, St. Lucia and Grenada (Table 1). Even in the absence of the oceanic barriers, i.e. within the larger islands, we find evidence of short range endemism124. While we do not claim to have thorough regional sampling, we find patterns of local endemism in regions where our sampling is particularly dense, providing the strongest test with available data. Many Caribbean spiders such as Spintharus44, Micrathena125 Selenops126 and Nops127, as well as other arachnid lineages such as Amblypygi64 and Pseudoscorpiones63, demonstrate a similar pattern. The distribution and quantity of SIEs depends on island properties such as maximum elevation, size, isolation and geological age128–132. While our focus was not on the effect of physical properties of islands on SIEs, the patterns seem to point towards a higher number of SIEs on the islands with a higher maximum elevation: Hispaniola (3098 m) is occupied by 4 or 6 MOTUs (depending on the delimitation method), Jamaica (2256 m) by three MOTUs and all other islands (<2000 m) by a single MOTU. The Caribbean islands, with the exception of Hispaniola, also harbor exclusively monophyletic Cyrtognatha lineages. The most rigorous tests of island monophyly would require thorough sampling within each island. However, if the patterns we observe represent biogeographic reality, we might explain this observed pattern with a combination of the niche preemption concept and organisms’ dispersal ability133–135. A combination of the first colonizer’s advantageous position to occupy empty niches and rare overwater dispersal events of their closely related species leads to competitive exclusion and lower probability for newcomers to establish viable populations on already occupied islands136–138. While niche preemption is better studied in plants, it is also applicable to animals, including spiders1,139.

Inferred dates indicate that Cyrtognatha most likely colonized the Caribbean through long distance overwater dispersal after the last hypothesized land connections. An ancient vicariant hypothesis would predict that the early proto-Antilles were connected to the continental America and were colonized in the distant past, possibly over 70 MYA140 and the GAARlandia landbridge putatively existed around 35–33 MYA. These hypothetical scenarios are not consistent with the dates reflected in our BEAST chronogram (Fig. 3) in which we estimate that the Caribbean Cyrtognatha split from its continental population as late as 15 MYA. This suggests that the genus Cyrtognatha is much younger than the most reasonable possible vicariant timeframe. While the estimated most recent common ancestral node is anchored by a single Central American representative, this inference is reasonable if our dating estimates are sound. If more extensive sampling on the continent broke up Caribbean monophyly, this would be evidence of more frequent dispersal between the islands and the continents, but would not likely change our estimations of the age of this ancestral node. More extensive sampling on the Caribbean could feasibly uncover Cyrtognatha taxa that share an older ancestor than that inferred from the Panamanian specimen, thus pushing back estimates of the timing of original colonization, however, given our relatively dense sampling on the Caribbean we find this unlikely.

Although, as explained above, overwater dispersal is the likely scenario, the reconstructed biogeographic patterns do not directly refute vicariance. Indeed, the biogeographic reconstruction (Fig. 4) of a combined ancestral area Panama + Hispaniola at the Cyrtognatha root leaves the possibility of a vicariant interpretation. However, this reconstruction is unlikely to reflect reality, and may be an artifact of our sparse continental taxon sampling.

Likewise, the alternative biogeographic reconstruction that omits the founder event (+J) (Supplementary Fig. S6) is consistent with vicariant origins of all Caribbean subclades. However, in the context of known Caribbean geological events, vicariance is extremely unlikely, thus questioning the validity of this alternative biogeographic history. For example, biotas on Lesser Antilles could not have originated vicariantly with those from Hispaniola given the geological knowledge that Lesser Antilles are de novo islands of volcanic origin, and thus had to be colonized.

There is further evidence that supports overwater dispersal in Cyrtognatha. First, the Jamaican lineage split from the one on Hispaniola soon after colonization of the Caribbean even though Jamaica was never a part of the proto-Antilles, and was thus never physically connected to Hispaniola. Secondly, Puerto Rico was a part of the proto-Antilles but was colonized only recently (4.8 MYA). The results of Jamaican and Puerto Rican colonization from Hispaniola thus are most consistent with a scenario of colonization by overwater dispersal.

The mid-Miocene (ca. 15 MYA) is considered as the start of the modern Earth141 in that the climate began to stabilize and the ocean currents started to take their current form. This combination of events enabled the colonization of the Caribbean islands from eastern-northern parts of South America for example via vegetation rafts passively drifting with water currents142. That also meant that the wind directions and the hurricane paths most likely resembled those of today143, from East to West direction144. In fact, hurricanes may create numerous dispersal/colonization opportunities, especially for the organisms with poor active dispersal abilities140,145. Wind directions and tropical storms are relevant for tetragnathid spiders like Cyrtognatha that disperse by ballooning and could facilitate their colonization of the Caribbean islands in a stepping stone146 or leap-frog147 manner.

With the examination of the relationships in the time calibrated phylogeny (Fig. 3), a colonization of the Caribbean from the continental America may have occurred sometime between 10.5 and 20.7 MYA. The most likely scenario indicates the original colonization of the Greater Antilles (Hispaniola; Fig. 4). Such patterns of colonization of Greater Antilles in Miocene are also evident in many other lineages including vertebrates, invertebrates and plants29,41,148–155. More rigorous tests of Cyrtognatha monophyly, as well as the number and directionality of colonization pathways onto the Caribbean, would require more thorough sampling across potential source populations on the mainland.

Our inference of ancestral ranges proposes an early within island diversification of Cyrtognatha ancestors occupying Hispaniola and predict that Hispaniola is the ancestral area for all Caribbean clades (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S5). The path of colonization does not resemble a straightforward pattern such as the stepping-stone pattern. The colonization sequence seems more random or resembles a “leap-frog” pattern. In our case the clear example of island being “leap frogged” is Puerto Rico. A leap frog pattern could indicate a role of hurricanes in movement among Caribbean islands140,156.

Conclusions

Our phylogenetic analysis of the tetragnathid spider genus Cyrtognatha facilitates reconstruction of its biogeographic history in the Caribbean. The ancestor of this relatively young lineage appears to have colonized the Caribbean overwater in the Miocene and further diversified into an exclusively single island endemic biogeographic pattern seen today. Further sampling of these rarely collected spiders in continental America is needed to confirm the timing, number and source of colonization of the Caribbean and to contrast those from other Caribbean spider clades. For example, Spintharus44,48 and Deinopis157 patterns clearly support ancient vicariance, but Argiope27 readily disperses among the islands. Tetragnatha, the sister lineage of Cyrtognatha, may prove to be of particular interest in comparison, because its biogeographic history on the islands may mirror their global tendency towards repeated colonization of even most remote islands.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the entire CarBio team (http://www.islandbiogeography.org/participants.html) for collecting the material across the Caribbean. Moreover, we thank Lisa Chamberland and other members of the Agnarsson lab (http://www.theridiidae.com/lab-members.html) for the help with material sorting and molecular procedures. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DEB-1314749, DEB-1050253), and the Slovenian Research Agency (J1-6729, P1-0236, BI-US/17-18-011).

Author Contributions

Research design: K.Č., I.A., G.B., M.K. Material acquisition and molecular procedures: I.A., G.B., K.Č., M.K. Data analyses: K.Č. K.Č. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to writing and revising the paper.

Data Availability

All data generated in this study and protocols needed to replicate it are included in this published article and its Supplementary Material Files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-36590-y.

References

- 1.Losos, J. B., Ricklefs, R. E. & MacArthur, R. H. The Theory of Island BiogeographyRevisited (eds Losos, J. B. & Ricklefs, R. E.) 476p (Princeton University Press, 2009).

- 2.Henderson, S. J. & Whittaker, R. J. Islands in Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

- 3.Weigelt P, Jetz W, Kreft H. Bioclimatic and physical characterization of the world’s islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:15307–15312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306309110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (Murray, London, 1859).

- 5.Warren BH, et al. Islands as model systems in ecology and evolution: prospects fifty years after MacArthur-Wilson. Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:200–217. doi: 10.1111/ele.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Grady P, DeSalle R. Out of Hawaii: the origin and biogeography of the genus Scaptomyza (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Biol. Lett. 2008;4:195–199. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricklefs RE. Historical biogeography and extinction in the Hawaiian Honeycreepers. Am. Nat. 2017;190:E106–E111. doi: 10.1086/693346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy SR, Dawson TE, Gillespie RG. Stable isotopes of Hawaiian spiders reflect substrate properties along a chronosequence. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4527. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgar GJ, Banks S, Fariña JM, Calvopiña M, Martínez C. Regional biogeography of shallow reef fish and macro-invertebrate communities in the Galapagos archipelago. J. Biogeogr. 2004;31:1107–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournié G, et al. Biogeography of parasitic nematode communities in the Galápagos giant tortoise: Implications for conservation management. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvajal-Endara S, Hendry AP, Emery NC, Davies TJ. Habitat filtering not dispersal limitation shapes oceanic island floras: species assembly of the Galápagos archipelago. Ecol. Lett. 2017;20:495–504. doi: 10.1111/ele.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fattorini S, Rigal F, Cardoso P, Borges PAV. Using species abundance distribution models and diversity indices for biogeographical analyses. Acta Oecologica. 2016;70:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ávila SP, et al. How did they get here? The biogeography of the marine molluscs of the Azores. Bull. la Soc. Geol. Fr. 2009;180:295–307. doi: 10.2113/gssgfbull.180.4.295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaefer H, et al. The Linnean shortfall in oceanic island biogeography: A case study in the Azores. J. Biogeogr. 2011;38:1345–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planas E, Ribera C. Description of six new species of Loxosceles (Araneae: Sicariidae) endemic to the Canary Islands and the utility of DNA barcoding for their fast and accurate identification. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2015;174:47–73. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinbauer MJ, et al. Biogeographic ranges do not support niche theory in radiating Canary Island plant clades. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016;25:792–804. doi: 10.1111/geb.12425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomé B, et al. Along for the ride or missing it altogether: Exploring the host specificity and diversity of haemogregarines in the Canary Islands. Parasites and Vectors. 2018;11:190. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2760-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliver PM, Travers SL, Richmond JQ, Pikacha P, Fisher RN. At the end of the line: Independent overwater colonizations of the Solomon Islands by a hyperdiverse trans-Wallacean lizard lineage (Cyrtodactylus: Gekkota: Squamata) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2018;182:681–694. doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pikacha P, Morrison C, Filardi CE, Leung L. Factors affecting frog species richness in the Solomon Islands. Pacific Conserv. Biol. 2017;23:387–398. doi: 10.1071/PC17011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weeks BC, et al. New behavioral, ecological, and biogeographic data on the montane avifauna of Kolombangara, Solomon Islands. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2017;129:676–700. doi: 10.1676/16-156.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agnarsson I, et al. Systematics of the Madagascar Anelosimus spiders: Remarkable local richness and endemism, and dual colonization from the Americas. Zookeys. 2015;2015:13–52. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.509.8897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacon CD, Simmons MP, Archer RH, Zhao LC, Andriantiana J. Biogeography of the Malagasy Celastraceae: Multiple independent origins followed by widespread dispersal of genera from Madagascar. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;94:365–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei R, et al. Phylogenomic reconstruction of sportive lemurs (genus Lepilemur) recovered from mitogenomes with inferences for Madagascar biogeography. J. Hered. 2017;108:107–119. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esw072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallis GP, et al. Rapid biological speciation driven by tectonic evolution in New Zealand. Nat. Geosci. 2016;9:140. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opell BD, Helweg SG, Kiser KM. Phylogeography of Australian and New Zealand spray zone spiders (Anyphaenidae: Amaurobioides): Moa’s Ark loses a few more passengers. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;118:959–969. doi: 10.1111/bij.12788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCulloch GA, Wallis GP, Waters JM. Does wing size shape insect biogeography? Evidence from a diverse regional stonefly assemblage. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017;26:93–101. doi: 10.1111/geb.12529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agnarsson I, et al. Phylogeography of a good Caribbean disperser: Argiope argentata (Araneae, Araneidae) and a new ‘cryptic’ species from Cuba. Zookeys. 2016;2016:25–44. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.625.8729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds RG, et al. Archipelagic genetics in a widespread Caribbean anole. J. Biogeogr. 2017;44:2631–2647. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker DB, Hedges SB, Colli GR, Pyron RA, Sites JW. Genomic timetree and historical biogeography of Caribbean island ameiva lizards (Pholidoscelis: Teiidae) Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:7080–7090. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricklefs RE, Bermingham E. The West Indies as a laboratory of biogeography and evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008;363:2393–2413. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittermeier, R. A., Turner, W. R., Larsen, F. W., Brooks, T. M. & Gascon, C. Global Biodiversity Conservation: The Critical Role of Hotspots in Biodiversity Hotspots (eds Zachos, F. E. & Habel, J. C.) 3–22 (Springer, 2011).

- 33.Bowen BW, Rocha LA, Toonen RJ, Karl SA. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013;28:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pindell JL, Maresch WV, Martens U, Stanek K. The Greater Antillean Arc: Early Cretaceous origin and proposed relationship to Central American subduction mélanges: Implications for models of Caribbean evolution. Int. Geol. Rev. 2012;54:131–143. doi: 10.1080/00206814.2010.510008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lomolino, M. V., Riddle, B. R. & Whittaker, R. J. Biogeography: Biological Diversity across Space and Time (Sinauer Associates Inc., 2017).

- 36.Hedges SB, Hass CA, Maxson LR. Caribbean biogeography: molecular evidence for dispersal in West Indian terrestrial vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:1909–1913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penney D, Selden PA. Spinning with the dinosaurs: the fossil record of spiders. Geol. Today. 2007;23:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2451.2007.00641.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iturralde-Vinent MA, MacPhee RDE. Paleogeography of the Caribbean region: Implications for Cenozoic biogeography. Bull. Am. Museum Nat. Hist. 1999;238:1–95. [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacPhee RDE, Grimaldi DA. Mammal bones in Dominican amber. Nature. 1996;380:489–490. doi: 10.1038/380489b0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacPhee, R. D. E. & Iturralde-Vinent, M. A. First Tertiary land mammal from Greater Antille: An early Miocene sloth (Xenarthra, Megalonychidae) from Cuba. Am. Museum Novit. 1–13 (1994).

- 41.Iturralde-Vinent MA. Meso-Cenozoic Caribbean paleogeography: Implications for the historical biogeography of the region. Int. Geol. Rev. 2006;48:791–827. doi: 10.2747/0020-6814.48.9.791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham A. Geohistory models and Cenozoic paleoenvironments of the Caribbean region. Syst. Bot. 2003;28:378–386. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali JR. Colonizing the Caribbean: Is the GAARlandia land-bridge hypothesis gaining a foothold? J. Biogeogr. 2012;39:431–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02674.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dziki A, Binford GJ, Coddington JA, Agnarsson I. Spintharus flavidus in the Caribbean - a 30 million year biogeographical history and radiation of a ‘widespread species’. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1422. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Říčan O, Piálek L, Zardoya R, Doadrio I, Zrzavý J. Biogeography of the Mesoamerican Cichlidae (Teleostei: Heroini): colonization through the GAARlandia land bridge and early diversification. J. Biogeogr. 2013;40:579–593. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alonso R, Crawford AJ, Bermingham E. Bermingham, E. Molecular phylogeny of an endemic radiation of Cuban toads (Bufonidae: Peltophryne) based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes. J. Biogeogr. 2012;39:434–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02594.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver, P. F., Cruz, A., Johnson, S., Dupin, J. & Weaver, K. F. Colonizing the Caribbean: biogeography and evolution of livebearing fishes of the genus Limia (Poeciliidae). J. Biogeogr.43, 1808–1819 (2016).

- 48.Agnarsson I, et al. A radiation of the ornate Caribbean ‘smiley-faced spiders’, with descriptions of 15 new species (Araneae: Theridiidae, Spintharus) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2018;182:758–790. doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uit de Weerd DR, Robinson DG, Rosenberg G. Evolutionary and biogeographical history of the land snail family Urocoptidae (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) across the Caribbean region. J. Biogeogr. 2016;43:763–777. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nieto-Blázquez ME, Antonelli A, Roncal J. Roncal, J. Historical biogeography of endemic seed plant genera in the Caribbean: Did GAARlandia play a role? Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:10158–10174. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pindell JL, Kennan, Stanek KP, Maresch WV, Draper G. Foundations of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean evolution: Geol. Acta. 2009;4:303–341. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boschman LM, van Hinsbergen DJJ, Torsvik TH, Spakman W, Pindell JL. Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic. Earth-Science Rev. 2014;138:102–136. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan, G. S. Quaternary land vertebrates of Jamaica in Biostratigraphy of Jamaica (eds Wright, R. E. & Robinson, E.) 417–442 (Geological Society of America Memoir, 1993).

- 54.Buskirk RE. Zoogeographic patterns and tectonic history of Jamaica and the northern Caribbean. J. Biogeogr. 1985;12:445. doi: 10.2307/2844953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagle F, Stipp JJ, Fisher DE. K-Ar geochronology of the Limestone Caribbees and Martinique, Lesser Antilles, West Indies. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1976;29:401–412. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(76)90145-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peck, S. B. Diversity and distribution of beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera) of the northern Leeward Islands. Maarten Insecta Mundi678 (2011).

- 57.Ricklefs RE, Lovette IJ. The roles of island area per se and habitat diversity in the species-area relationships of four Lesser Antillean faunal groups. J. Anim. Ecol. 1999;68:1142–1160. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00358.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garmon, W. T., Allen, C. D. & Groom, K. M. Landscapes and Landforms of the Lesser Antilles (Springer, 2017).

- 59.Munch P, et al. Pliocene to Pleistocene carbonate systems of the Guadeloupe archipelago, french lesser antilles: A land and sea study (the KaShallow project) Bull. la Soc. Geol. Fr. 2013;184:99–110. doi: 10.2113/gssgfbull.184.1-2.99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hedges SB. Historical Biogeography of West Indian Vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1996;27:163–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Surget-Groba Y, Thorpe RS. A likelihood framework analysis of an island radiation: phylogeography of the Lesser Antillean gecko Sphaerodactylus vincenti in comparison with the anoleAnolis roquet. J. Biogeogr. 2013;40:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02778.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crews SC, Puente-Rolón AR, Rutstein E, Gillespie RG. A comparison of populations of island and adjacent mainland species of Caribbean Selenops (Araneae: Selenopidae) spiders. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010;54:970–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cosgrove JG, Agnarsson I, Harvey MS, Binford GJ. Pseudoscorpion diversity and distribution in the West Indies: sequence data confirm single island endemism for some clades, but not others. J. Arachnol. 2016;44:257–271. doi: 10.1636/R15-80.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Esposito LA, et al. Islands within islands: Diversification of tailless whip spiders (Amblypygi, Phrynus) in Caribbean caves. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015;93:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Spider Catalog. World Spider Catalog Version 19.0, http://wsc.nmbe.ch (2018).

- 66.Agnarsson, I., Coddington, J. A. & Kuntner, M. Systematics: Progress in the study of spider diversity and evolution in Spider Research in the 21st Century: Trends and Perspectives (ed. Penney, D.) (Siri scientific press, 2013).

- 67.Bell JR, Bohan DA, Shaw EM, Weyman GS. Ballooning dispersal using silk: world fauna, phylogenies, genetics and models. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2005;95:69–114. doi: 10.1079/BER2004350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu L, Si X, Didham RK, Ge D, Ding P. Dispersal modality determines the relative partitioning of beta diversity in spider assemblages on subtropical land-bridge islands. J. Biogeogr. 2017;44:2121–2131. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee VMJ, Kuntner M, Li D. Ballooning behavior in the golden orbweb spider Nephila pilipes (Araneae: Nephilidae) Front. Ecol. Evol. 2015;3:2. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2015.00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lafage D, Sibelle C, Secondi J, Canard A, Pétillon J. Short-term resilience of arthropod assemblages after spring flood, with focus on spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) and carabids (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Ecohydrology. 2015;8:1584–1599. doi: 10.1002/eco.1606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reynolds AM, Bohan DA, Bell JR. Ballooning dispersal in arthropod taxa: conditions at take-off. Biol. Lett. 2007;3:237–40. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuntner, M. & Agnarsson, I. Phylogeography of a successful aerial disperser: The golden orb spider Nephila on Indian Ocean islands. BMC Evol. Biol. 11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Szymkowiak P, Górski G, Bajerlein D. Passive dispersal in arachnids. Biol. Lett. 2007;44:75–101. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Edwards JS, Thornton IWB. Colonization of an Island Volcano, Long Island, Papua New Guinea, and an Emergent Island, Motmot, in Its Caldera Lake. VI. The Pioneer Arthropod Community of Motmot. Source J. Biogeogr. 2016;28:1379–1388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00637.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu X, et al. A genus-level taxonomic review of primitively segmented spiders (Mesothelae, Liphistiidae) Zookeys. 2015;488:121–151. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.488.8726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu X, et al. Pre-Pleistocene geological events shaping diversification and distribution of primitively segmented spiders on East Asian margins. J. Biogeogr. 2016;43:1004–1019. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu X, et al. Extant primitively segmented spiders have recently diversified from an ancient lineage. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015;282:20142486–20142486. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bond JE, Hedin MC, Ramirez MG, Opell BD. Deep molecular divergence in the absence of morphological and ecological change in the californian coastal dune endemic trapdoor spider Aptostichus simus. Mol. Ecol. 2001;10:899–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bond JE, Beamer DA, Lamb T, Hedin MC. Combining genetic and geospatial analyses to infer population extinction in mygalomorph spiders endemic to the Los Angeles region. Anim. Conserv. 2006;9:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00024.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hedin MC, Starrett J, Hayashi C. Crossing the uncrossable: Novel trans-valley biogeographic patterns revealed in the genetic history of low-dispersal mygalomorph spiders (Antrodiaetidae, Antrodiaetus) from California. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:508–526. doi: 10.1111/mec.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.GBIF. Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Nat. Hist (2012).

- 82.Dimitrov D, Hormiga G. Revision and cladistic analysis of the orbweaving spider genus. Cyrtognatha. Bull. Am. Museum Nat. Hist. 2009;1881:140. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dimitrov D, et al. Tangled in a sparse spider web: single origin of orb weavers and their spinning work unravelled by denser taxonomic sampling. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012;279:1341–1350. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wheeler WC, et al. The spider tree of life: phylogeny of Araneae based on target-gene analyses from an extensive taxon sampling. Cladistics. 2017;33:574–616. doi: 10.1111/cla.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alvarez-Padilla F, Dimitrov D, Giribet G, Hormiga G. Phylogenetic relationships of the spider family Tetragnathidae (Araneae, Araneoidea) based on morphological and DNA sequence data. Cladistics. 2009;25:109–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coddington, J. A., Griswold, C. E., Silva, D., Penaranda, E. & Larcher, S. F. Designing and testing sampling protocols to estimate biodiversity in tropical ecosystems (Int. Congr. Syst. Evol. Biol. 1991).

- 87.Vidergar, N., Toplak, N. & Kuntner, M. Streamlining DNA barcoding protocols: Automated DNA extraction and a new cox1 primer in arachnid systematics. PLoS ONE9, e113030 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, deWaard JR. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003;270:313–321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Čandek K, Kuntner M. DNA barcoding gap: Reliable species identification over morphological and geographical scales. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015;15:268–277. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hedin MC, Maddison WP. A Combined molecular approach to phylogeny of the jumping spider subfamily Dendryphantinae (Araneae: Salticidae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001;18:386–403. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nunn GB, Theisen BF, Christensen B, Arctander P. Simplicity-correlated size growth of the nuclear 28S ribosomal RNA D3 expansion segment in the crustacean order isopoda. J. Mol. Evol. 1996;42:211–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02198847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Whiting MF. Mecoptera is paraphyletic: multiple genes and phylogeny of Mecoptera and Siphonaptera. Zool. Scr. 2002;31:93–104. doi: 10.1046/j.0300-3256.2001.00095.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maddison, W. & Maddison, D. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis version 3.51, http://www.mesquiteproject.org (2018).

- 97.Dimitrov D, Hormiga G. An extraordinary new genus of spiders from Western Australia with an expanded hypothesis on the phylogeny of Tetragnathidae (Araneae) Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2011;161:735–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00662.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang J, Kapli P, Pavlidis P, Stamatakis A. A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2869–76. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kapli P, et al. Multi-rate Poisson tree processes for single-locus species delimitation under maximum likelihood and Markov chain Monte Carlo. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:1630–1638. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fujisawa T, Barraclough TG. Delimiting species using single-locus data and the generalized mixed yule coalescent approach: A revised method and evaluation on simulated data sets. Syst. Biol. 2013;62:707–724. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Puillandre N, Lambert A, Brouillet S, Achaz G. ABGD, automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:1864–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bouckaert R, et al. Beast2: A software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;10:1003537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist FMR. BAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:772–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Golenberg EM, Clegg MT, Durbin ML, Doebley J, Ma DP. Evolution of a noncoding region of the chloroplast genome. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1993;2:52–64. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kelchner SA. The Evolution of Non-Coding Chloroplast DNA and Its Application in Plant Systematics. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 2000;87:482. doi: 10.2307/2666142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Borchsenius, F. FastGap 1.2, http://www.aubot.dk/FastGap_home.htm (2009).

- 109.Bouckaert R, Drummond AJ. bModelTest: Bayesian phylogenetic site model averaging and model comparison. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017;17:42. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0890-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bouckaert R, Alvarado-Mora MV, Rebello Pinho JR. Evolutionary rates and HBV: issues of rate estimation with Bayesian molecular methods. Antivir. Ther. 2013;18:497–503. doi: 10.3851/IMP2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baele G, et al. Improving the accuracy of demographic and molecular clock model comparison while accommodating phylogenetic uncertainty. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012;29:2157–2167. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Baele G, Li WL, Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Lemey P. Accurate model selection of relaxed molecular clocks in bayesian phylogenetics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:239–43. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bidegaray-Batista L, Arnedo MA. Gone with the plate: the opening of the Western Mediterranean basin drove the diversification of ground-dweller spiders. BMC. Evol. Biol. 2011;11:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G. & Suchard, M. A. Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 1–3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Rambaut, A. FigTree v 1.4.3, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (2018).

- 116.Miller, M. A., Pfeiffer, W. & Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees in Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (2010).

- 117.Matzke NJ. Probabilistic historical biogeography: New models for founder-event speciation, imperfect detection, and fossils allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Front. Biogeogr. 2013;5:242–248. doi: 10.21425/F55419694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://cran.r-project.org/ (2018).

- 119.Lam AR, Stigall AL, Matzke NJ. Dispersal in the Ordovician: Speciation patterns and paleobiogeographic analyses of brachiopods and trilobites. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018;489:147–165. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pereira AG, Schrago CG. Arrival and diversification of mabuyine skinks (Squamata: Scincidae) in the Neotropics based on a fossil-calibrated timetree. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3194. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heads M. Old taxa on young islands: A critique of the use of island age to date island-endemic clades and calibrate phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 2011;60:204–218. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hipsley CA, Müller J. Beyond fossil calibrations: Realities of molecular clock practices in evolutionary biology. Front. Genet. 2014;5:138. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ree RH, Sanmartín I. Conceptual and statistical problems with the DEC + J model of founder-event speciation and its comparison with DEC via model selection. J. Biogeogr. 2018;45:741–749. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Harvey MS. Short-range endemism among the Australian fauna: Some examples from non-marine environments. Invertebr. Syst. 2002;16:555–570. doi: 10.1071/IS02009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.McHugh A, Yablonsky C, Binford GJ, Agnarsson I. Molecular phylogenetics of Caribbean Micrathena (Araneae: Araneidae) suggests multiple colonisation events and single island endemism. Invertebr. Syst. 2014;28:337–349. doi: 10.1071/IS13051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Crews SC, Gillespie RG. Molecular systematics of Selenops spiders (Araneae: Selenopidae) from North and Central America: Implications for Caribbean biogeography. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010;101:288–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01494.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sánchez-Ruiz A, Brescovit AD, Alayón G. Four new caponiids species (Araneae, Caponiidae) from the West Indies and redescription of Nops blandus (Bryant) Zootaxa. 2015;3972:43–64. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3972.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kallimanis AS, et al. Biogeographical determinants for total and endemic species richness in a continental archipelago. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010;19:1225–1235. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9748-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gray A, Cavers S. Island biogeography, the effects of taxonomic effort and the importance of island niche diversity to single-island endemic species. Syst. Biol. 2014;63:55–65. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Whittaker RJ, Triantis KA, Ladle RJ. A general dynamic theory of oceanic island biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 2008;35:977–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dalsgaard B, et al. Determinants of bird species richness, endemism, and island network roles in Wallacea and the West Indies: Is geography sufficient or does current and historical climate matter? Ecol. Evol. 2014;4:4019–4031. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Steinbauer MJ, Otto R, Naranjo-Cigala A, Beierkuhnlein C, Fernández-Palacios JM. Increase of island endemism with altitude - speciation processes on oceanic islands. Ecography (Cop.). 2012;35:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2011.07064.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bellemain E, Ricklefs RE. Are islands the end of the colonization road? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Silvertown J, Francisco-Ortega J, Carine MA. The monophyly of island radiations: An evaluation of niche pre-emption and some alternative explanations. J. Ecol. 2005;93:653–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mwangi PN, et al. Niche pre-emption increases with species richness in experimental plant communities. J. Ecol. 2007;95:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01189.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wiens, J. A. The Ecology of Bird Communities: Volume 2: Processes and Variations (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- 137.Fukami T. Historical contingency in community assembly: Integrating niches, species pools, and priority effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015;46:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110411-160340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Esselstyn JA, Maher SP, Brown RM. Species interactions during diversification and community assembly in an island radiation of shrews. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Garb JE, Gillespie RG. Island hopping across the central Pacific: Mitochondrial DNA detects sequential colonization of the Austral Islands by crab spiders (Araneae: Thomisidae) J. Biogeogr. 2006;33:201–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01398.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hedges, S. B. Biogeography of the West Indies: An overview in Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and perspectives (eds Woods, C. A. & Sergile, F. E.) (CRC Press, 2001).

- 141.Pound MJ, Haywood AM, Salzmann U, Riding JB. Global vegetation dynamics and latitudinal temperature gradients during the mid to late Miocene (15.97–5.33Ma) Earth Sci. Rev. 2012;112:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ketmaier V, Giusti F, Caccone A. A. Molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of the land snail genus Solatopupa (Pulmonata) in the peri-Tyrrhenian area. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;39:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]