Abstract

Background

Sugarcane served as the model plant for discovery of the C4 photosynthetic pathway. Magnesium is the central atom of chlorophyll, and thus is considered as a critical nutrient for plant development and photosynthesis. In plants, the magnesium transporter (MGT) family is composed of a number of membrane proteins, which play crucial roles in maintaining Mg homeostasis. However, to date there is no information available on the genomics of MGTs in sugarcane due to the complexity of the Saccharum genome.

Results

Here, we identified 10 MGTs from the Saccharum spontaneum genome. Phylogenetic analysis of MGTs suggested that the MGTs contained at least 5 last common ancestors before the origin of angiosperms. Gene structure analysis suggested that MGTs family of dicotyledon may be accompanied by intron loss and pseudoexon phenomena during evolution. The pairwise synonymous substitution rates corresponding to a divergence time ranged from 142.3 to 236.6 Mya, demonstrating that the MGTs are an ancient gene family in plants. Both the phylogeny and Ks analyses indicated that SsMGT1/SsMGT2 originated from the recent ρWGD, and SsMGT7/SsMGT8 originated from the recent σ WGD. These 4 recently duplicated genes were shown low expression levels and assumed to be functionally redundant. MGT6, MGT9 and MGT10 weredominant genes in the MGT family and werepredicted to be located inthe chloroplast. Of the 3 dominant MGTs, SsMGT6 expression levels were found to be induced in the light period, while SsMGT9 and SsMTG10 displayed high expression levels in the dark period. These results suggested that SsMGT6 may have a function complementary to SsMGT9 and SsMTG10 that follows thecircadian clock for MGT in the leaf tissues of S. spontaneum. MGT3, MGT7 and MGT10 had higher expression levels Insaccharum officinarum than in S. spontaneum, suggesting their functional divergence after the split of S. spontaneum and S. officinarum.

Conclusions

This study of gene evolution and expression of MGTs in S. spontaneum provided basis for the comprehensive genomic study of the entire MGT genes family in Saccharum. The results are valuable for further functional analyses of MGT genes and utilization of the MGTs for Saccharum genetic improvement.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-019-5437-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Saccharum, Magnesium transporter, Gene evolution, Gene expression

Background

Magnesium (Mg) is the 8th most abundant element on earth, the 4th most abundant element in vertebrates, and the 2nd most abundant cation in plants. Mg’s ionic radius is among the smallest but the hydrated radius is so far the largest of all cations [1]. Due to its unique chemical property, Mg plays an essential role in plant growth and development, such as being the central atom of the porphyrin ring of chlorophyll, enabling plants to perform photosynthesis [2, 3], and a co-enzyme in the form of Mg2+-ATP complexes or acts as a cofactors for more than 300 enzymes that are involved in enzyme activation [4–6]. Mg also alleviates plant toxicity from aluminum (Al) and heavy metals [7], and is involved in protein synthesis by bridging ribosome sub-units [8]. Due to its potential for leaching in highly weathered soils and the interaction with Al [9], Mg2+ bind weakly to negative charged soil colloids and root cell walls by its unique chemical property, which leads to the easy loss of exchangeable Mg2+ from soil. As a result, the magnesium deficiency is an issue of crucial importance in acid soils [10]. One third of the tropics, or 1.7 billion hectares is acid soil [11]. Consequently, the magnesium deficiency hindered the production of tropical crop such as sugarcane.

Since Mg is one of the essential macroelements in plants, deficiency of Mg causes marked inhibition of plant growth and development, including symptoms such as leaf interveinal chlorosis, particularly in mature leaves due to the high mobility of Mg in plants [9], which therefore decreases photosynthesis efficiency. Mg deficiency alsonegatively impacts carbon allocation to sink organs [12], and inhibits plant root growth [13], which leads to a deleterious effect on both crop productivity and quality [12].

Plant Mg-uptake from soil solution is controlled by 2 predominantly processes: mass flow and diffusion. To maintain concentration of Mg in tissues, plants have a series of highly-efficiency transport methods for Mg uptake, storage and translocation. The MGT family is composed of several membrane proteins that maintain Mg homeostasis to support plant growth. The main MGT genes were originally identified from Salmonella typhimurium, which belongs to the CorA family of bacteria [14]. In Salmonella typhimurium, CorA is a single copy gene encoding a 37-kD integral membrane protein [15]. In plants, Li et al. (2001) first identified 10 MGTs in the model plant Arabidopsisthaliana [16]. MGT families were also identified in rice (Oryza sativa) [17] and maize (Zea mays) [18], However, the relationships between gene structure and gene divergence of MGTs have not been reported in previous studies. Gene families were originated from duplicated events including the whole genome duplication (WGD), segment duplication and tandem duplication, playing key roles in organism evolutionary process. The retained duplicated genes tend to diverge in regulatory and coding regions and were accomplished by three main types of mechanisms, exon/intron gain/loss, exonization/pseudoexonization, and insertion/deletion [19]. In Arabidopsis, AtMGT9 was found to play an essential role in pollen development [20], and AtMGT10 is essential for chloroplast development and photosynthesis [21], whereas AtMGT6, as a Mg uptake transporter, is required for growth under low Mg conditions [22]. In Oryza sativa, OsMGT1 was found to play an important role in the tolerance to Al toxicity and salt stress [23]. In maize, ZmMGT10 is essential in response to Mg deficiency, and confers low Mg tolerance when the ZmMGT10 gene is overexpressed in Arabidopsis thaliana [24].

Identifying MGTs in sugarcane and studying the regulatory mechanism in response to Mg stress is of particular interest because sugarcane is a model C4 crop. Indeed, sugarcane contributes about 80% of the world sugar and about 40% of ethanol production worldwide. Consequently, the effects of Mg on sugarcane yield and quality have been studied, and field experiments have clearly established that yield can be significantly improved when N and P utilization are balanced with K, S, and Mg. [25, 26]. However, these studies largely focused on phenotypic features, physiological function and the pathology of Mg deficiency [12, 27–29]. In addition, due to hyper-ploidy, the modern sugarcane cultivar has one of the most complex genomes among all the crops, being both an aneuploid and autopolyploid with an extreme ploidy level that can range from octoploidy (x = 8) to dodecaploidy (x = 12). The chromosome number of different species in the genus Saccharum ranges from 36 to 170 (S. officinarum, 2n = 70 to 140; S. robustum, 2n = 66 to 170; S. spontaneum, 2n = 36 to 128) [30]. To date, our understanding of the regulatory mechanism in response to Mg stress and MGT in Saccharum remains very limited due to lack of reference genome in the past.

In this study, basing on the recent sequencing S. spontaneum genome [31], we identified the MGTs in S. spontaneum (SsMGTs). Phylogenetics, comparative genomics and gene expression patterns were used to study the evolutionary relationship and potential function of MGT families in Saccharum.

Results

Identification of MRS2/MGT family genes in S. spontaneum

Based on comparative genomics technology, ten members of MRS2/MGTs were identified from the Sorghum bicolor genome (Table 1). Using these sorghum MGTs as a reference, 10 orthologous MGTs were identified in the monoploidy genome database of AP85–441 [31]. Open reading frame of the SsMRS2/MGTs were analyzed based on an online tool ORF finder [32]. The SsMRS2/MGT proteins were 290–539 amino acid (aa) residues in length, with an average length of 414 aa, and the corresponding molecular masses ranged from 39.13 to 58.68 kDa, average molecular weight was 47.63 kDa, the computed theoretical isoelectric points varied greatly, ranging from 4.66(SsMGT1) to 9.29(SsMGT5). These 10 genes were named SsMGT1-SsMGT10.

Table 1.

Information about the putative MGT genes in Sorghum bicolor

| Corresponding genename in sugarcane | GeneID | TranscriptID | ProteinID | Gene location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SsMGT1 | Sobic.006G082200 | XM_002446449 | XP_002446494 | Chr06:45079489..45081310forward |

| SsMGT2 | Sobic.007G185200 | XM_002445725 | XP_002445770 | Chr07:61831349..61833678reverse |

| SsMGT3 | Sobic.003G395600 | XM_002458906 | XP_002458951 | Chr03:70601663..70609036 reverse |

| SsMGT4 | Sobic.006G137200 | XM_002446702 | XP_002446747 | Chr06:49948483..49953310 forward |

| SsMGT5 | Sobic.010G210500 | XM_002438717 | XP_002438762 | Chr10:55405378..55409126 reverse |

| SsMGT6 | Sobic.001G095000 | XM_002463854 | XP_002463899 | Chr01:7305915..7311750 forward |

| SsMGT7 | Sobic.001G309400 | XM_002464953 | XP_002464998 | Chr01:59477626..59480767 forward |

| SsMGT8 | Sobic.001G512100 | XM_002465855 | XP_002465900 | Chr01:78001611..78004021 forward |

| SsMGT9 | Sobic.001G135100 | XM_002466617 | XP_002466662 | Chr01:10653760..10659627 reverse |

| SsMGT10 | Sobic.003G395600 | XM_002458906 | XP_002458951 | Chr03:70601663..70609036 reverse |

These sorghum MGTs were also used as reference to search the recent published genome of Saccharum hybridR570 [33], and 9 MGTs were identified (Additional file 1). Noteworthy, a pair of tandem duplicated genes (Sh06 p004330 and Sh06 p004340) were found in the Saccharum hybridR570 genome, and were likely originated from S. officinarum as the tandem duplicated genes of MGT which were not found in S. spontaneum (Additional file 2). These two ShMGTs shared high (72%) sequence similarity, suggesting that they were originated from the very recent tandem duplication event. Two orthologs of SsMGTs (SsMGT3, SsMGT6) were absented in the R570 genome, which may be caused by the incomplete Saccharum genome (Additional file 1).

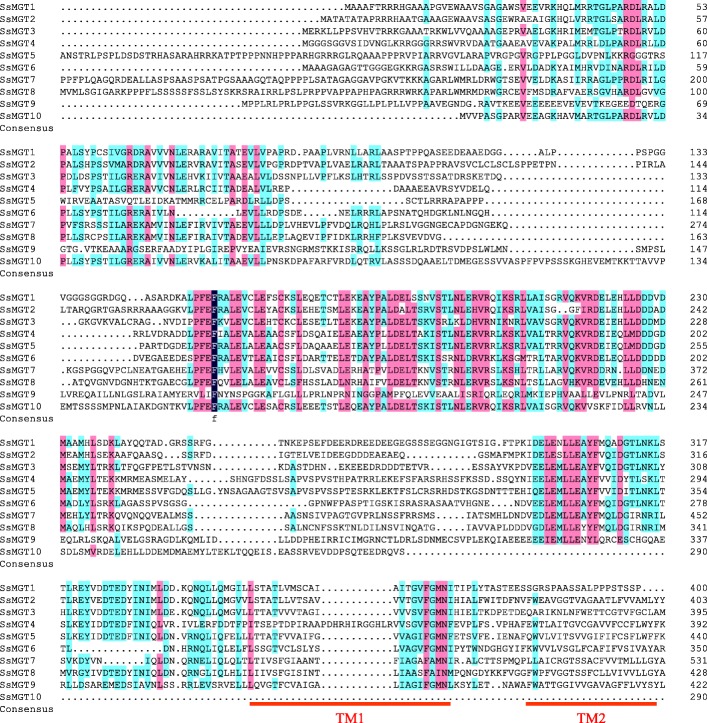

A multiple protein sequence alignment was performed to analyze the conservation of motifs in the examined plant species (Fig. 1). Eight of theSsMGTs in sugarcane shared a common GMN motif with Arabidopsis, Oryza sativa and Zea mays except for SsMGT7 and SsMGT8. SsMGT7 contained an AMN motif instead of GMN, and SsMGT8 contained an AIN motif instead of GMN, similarly to OsMRS2/MGT in Oryza sativa [17]. Nine of these SsMRS2/MGT contained the complement CorA TM domain except for SsMGT10 [34].

Fig. 1.

Multiple protein sequence alignment of the SsMGT family was performed using by DNAMAN software. The degree of similarity of 10 SsMGTs protein sequences are displayed in different colors (100%, deep blue; 75–99%, cherry red and 50–74% colored by cyan). TM domains are marked with red lines, the typical conserved GMN motifs are highlighted by red boxes

Using the WoLF PSORT program, 8 of the SsMGT proteins were predicted to be located in chloroplasts, the remaining 2 SsMGT proteins were predicted to be localized in the mitochondria (SsMGT3) or plasma membrane (SsMGT5) (Table 2), indicating that these SsMGTs mainly play a role in the chloroplasts to maintain Mg2+ homeostasis in sugarcane. The analysis of the TM domain revealed that 9 of the SsMGTs, except SsMGT10, contained 9 protein TM domains near their C-terminal ends, which were similar to the CorA/MRS2/MGT transporters from other plant species, including Arabidopsis, rice and maize. Significantly, both SsMGT1 and SsMGT3 contained only onetransmembrane domain, and SsMGT10 have no transmembrane domains (Additional file 3). Pairwise comparisons among the SsMGTs showed that all these MGTs are independent, and shared protein sequence similarities that ranged from 21 to 63% with an average of 39%, indicating theMGTs are an ancient gene family with high sequence divergence (Additional file 4).

Table 2.

Characterization comparison of the MGT genes between Sorghum bicolor and Saccharum

| S. bicolor | S. spontaneum | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Gene ID | Amino acids size | Molecular weights(kDa) | Domains | Isoelectric point (PI) | Transmembrane helices | Predicted locationa | Gene name | Gene ID | Amino acids size | Molecular weights(kDa) | Domains | Isoelectric point (PI) | Transmembrane helices | Identity% | Predicted locationa |

| SbMGT1 | Sobic.006G082200 | 421 | 45.02 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.66 | 2 | chlo | SsMGT1 | AP850373380 | 400 | 42.92 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.66 | 1 | 89.87% | chlo |

| SbMGT2 | Sobic.007G185200 | 359 | 39.02 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.82 | 2 | chlo | SsMGT2 | AP851129300 | 410 | 44.5 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.1 | 2 | 72.60% | chlo |

| SbMGT3 | Sobic.003G369600 | 414 | 46.21 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.91 | 2 | mito | SsMGT3 | AP851069690 | 410 | 46.02 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.15 | 2 | 93.25% | mito |

| SbMGT4 | Sobic.006G137200 | 441 | 48.91 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.27 | 2 | plas | SsMGT4 | AP850864340 | 399 | 45.07 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.27 | 1 | 86.33% | chlo |

| SbMGT5 | Sobic.010G210500 | 348 | 39.62 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.82 | 2 | plas | SsMGT5 | AP851097490 | 446 | 49.75 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 9.29 | 2 | 83.62% | Plas |

| SbMGT6 | Sobic.001G095000 | 387 | 42.71 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.86 | 2 | cyto | SsMGT6 | AP850291960 | 357 | 39.13 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.09 | 2 | 89.72% | chlo |

| SbMGT7 | Sobic.001G309400 | 478 | 52.38 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 8.33 | 2 | mito | SsMGT7 | AP850490950 | 539 | 58.68 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 7.7 | 2 | 91.49% | chlo |

| SbMGT8 | Sobic.001G512100 | 432 | 48.3 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 9.33 | 2 | chlo | SsMGT8 | AP851016400 | 492 | 55.02 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 8.99 | 2 | 92.89% | chlo |

| SbMGT9 | Sobic.001G135100 | 458 | 50.74 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.38 | 2 | chlo | SsMGT9 | AP851096250 | 428 | 47.62 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 5.3 | 2 | 97.19% | chlo |

| SbMGT10 | Sobic.003G395600 | 443 | 48.55 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.81 | 2 | chlo | SsMGT10 | AP851092670 | 290 | 31.91 | Mrs2_Mfm1p-like | 4.8 | 0 | 90.59% | chlo |

achlo Chloroplast, mito Mitochondria, plas Plasma membrane, cyto Cytoplastic

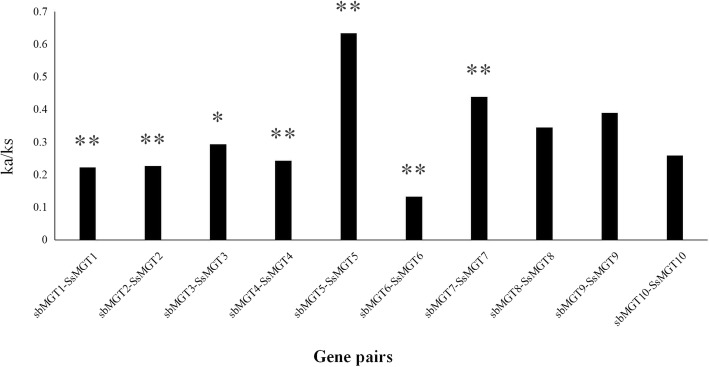

Nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) was analysed to investigate the evolutionary function constraint in S. spontaneum, 10 pairs of orthologous SsMGT genes between S. spontaneum and sorghum were calculated. The results show that, except for SsMGT5, the Ka/Ks ratios of other 9 genes were less than 0.5 (Fig. 2), suggesting that purifying selection was the main force for driving the evolution of MGT genes [35].

Fig. 2.

The non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution ratios of the 10 pairs of orthologous MGTs genes from sorghum and sugarcane were calculated by the easy_kaks calculate program. * and ** represent p value< 0.05 and p value< 0.01 respectively

Phylogenetic analysis of SsMGTs and other plant MGTs

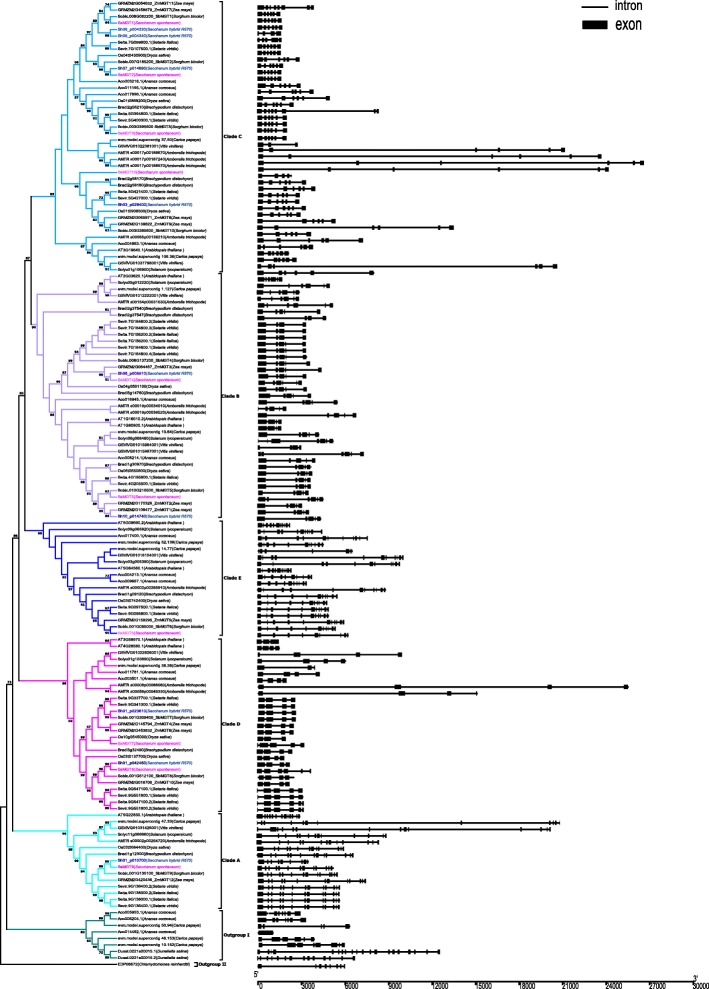

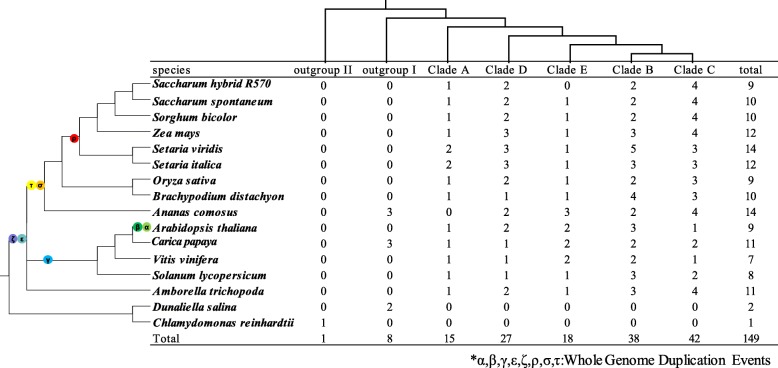

To analyze the phylogenetics of the MGT gene family, a total 149 MGTs from 16 representative plant species and 2 species as outgroups (Chlamydomonas reinhardtiianddunaliella salina) were used to construct the phylogenetic tree using the Neighbor-Joining and Maximum Likelihood method (Fig. 3, Additional files 5, 6 and 7 ). These MGT genes were phylogenetically divided into 5 clades (A, B, C, D and E) based on the previously reported ZmMGTs [18] (Additional file 7). The distribution of MGT gene numbers of the examined species showed that the ancient WGD did not contribute to the expansion of the MGT gene family (Fig. 4), whereas the MGT number in each clade gradually increased.Noteworthy, pineapple MGTs were divided into the outgroup, close to the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and before MGTs of Dunaliella salina, speculating that horizontal gene transfer may contribute to the gene expansion of MGT in pineapple. Different from ZmMGTs research [18], phylogenetic tree in this study showed that the Clade D and Clade E were classed into different cluster, which may be caused by integrating more MGT families from representative species for phylogenetic analysis. Moreover, all 5 clades contained MGT genes from the 12 representative angiosperms plants, suggesting that MGT genes from each of the 5 clades appeared before the emergence of angiosperms. The evolution history of MGT clade could be sorted by age in duplicated descending order: Clade A, Clade D, Clade E, Clade B and Clade C.

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny and schematic diagram for intron/exon organization of MGT genes from 14 plant species

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of MGTs families based on the current data for angiosperms

Among the ten SsMGTgenes, within clade A, SsMGT9 was retained from the first round of gene duplication in angiosperms; within clade D, SsMGT7 and SsMGT8 were originated from last common ancestral (LCA) in the second round of gene duplication in angiosperms by a gene duplication event which occurred after the divergence of monocots and dicots; within clade E, SsMGT6 was retained from the third round of gene duplication in angiosperms; within clade B, SsMGT4 and SsMGT5 were duplicated from LCA in the 4th round of gene duplication in angiosperms before the split of dicots and monocots; within clade C, SsMGT1 and SsMGT2 were derived from the ρWGD events, SsMGT3 originated from the LCA of angiosperms, SsMGT10 was retained in monocots from the gene duplication event before emergence of angiosperms.

Exon/intron organization of the SsMGTs family and MGTs in other plant species

In the examined plant species, the gene structure of MGTs varied in both exon number and size. To investigate the structural characteristics and evolution of the MGT genes in different species, we analysed the gene features and patterns of the MGTs (Fig. 3). The exon number of MGTs ranged from 1 to 20 with an average about 7 (Additional files 8 and 9), and 103 of the 149 MGTs have exon numbers ranging from 4 to 6. We thus speculated that the LCA exon number of angiosperms MGT gene is between 4 and 6. Each of the subgroups had a similar exon number except for Ananas comosus.

The exon number of SsMGTs ranged from 5 to 13, and 6 of SsMGTs harboured 6 exons (Additional file 8). Moreover, the SsMGTs gene structure showed a pattern similar to SbMGTs and ZmMGTs from the same clade, suggesting the conservatism of the MGT gene structure in the Panicoideae. In clade A, MGTs genes have higher exon number than in other clades. These genes contained 9–14 exons of MGTs genes, which is likely due to the exon splitting as their protein sizes remained consistent. In clade B, MGTs exon number ranged from 4 to 7, The first exon and second intron of SsMGT5 is larger than that of SbMGT5, which indicated an expansion and exonization of the second intron. In clade C, MGTs exon number ranged from 4 to 8, while the number of SsMGT exons was conserved. In clade D, MGTs exon number ranged from 3 to 6, gene structures were more conserved in monocots than in dicots, and gene expansions only existed in the dicots. Important to note, both SsMGT7 and 8 have one more exon than the other monocots MGTs, which was likely caused by exonization. In clade E, MGTs exon number ranged from 7 to 12, the exon number of SsMGT6 was less than the other MGTs, which may be caused by the pseudo-exonization in this gene. These results suggested that MGTs experienced gene structure reconstruction under different evolutionary dynamics in S. spontaneum as well as in angiosperms.

Based on the pairwise synonymous substitution rates (Ks) in angiosperms (Table 3, Additional file 10), we estimated the divergence time among 5 clades of MGT family. The median values of pairwise Ks ranged from 1.74 to 2.89, corresponding to a divergence time ranging from 142.3 to 236.6 Mya, indicating that the MGTs in the 5 clades are ancient and divergent. Moreover, the divergence times among the 4 SsMGTs ranged from 52.6 to 96.7 Mya (Table 4). Taken together, these results suggest that the MGT family is an ancient gene family with a recent gene duplication event in Gramineae.

Table 3.

Divergence time among 5 clades of MGTs family in angiosperms

| Clade-Clade | Median Ks | Gene pairs used | Divergence time (Mya) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-B | 2.88637 | 234 | 236.6 |

| A-C | 2.49044 | 162 | 204.1 |

| A-D | 2.30398 | 270 | 188.9 |

| A-E | 2.16215 | 172 | 177.2 |

| B-C | 1.73644 | 412 | 142.3 |

| B-D | 1.9539 | 460 | 160.2 |

| B-E | 2.20187 | 436 | 180.5 |

| C-D | 2.29602 | 608 | 188.2 |

| C-E | 2.26799 | 355 | 185.9 |

| D-E | 2.47121 | 252 | 202.6 |

Table 4.

Divergence between paralogous SsMGTs pairs inS. spontaneum

| Gene1 | Gene2 | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | Divergence time (Mya) | P-Value (Fisher) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SsMGT1 | SsMGT2 | 0.268 | 0.642 | 0.417 | 52.6 | 1.56519E-11 |

| SsMGT7 | SsMGT8 | 0.347 | 1.180 | 0.295 | 96.7 | 6.86283E-24 |

Gene expression and functional analysis of MGTs in two Saccharum species

Gene expression pattern information provides initial reference for evaluating their potential function in plant. In this study, to understand the potential function of MGTs in Saccharum species, we investigated gene expression patterns based on 4 sets of RNAseq data: 1) Different developmental stages;2) Leaf gradient; 3) Time course and 4) Hormone treatment. The Reads Per Kilobase of exon per Million (RPKM) reads ofMGT6, MGT9 and MGT10 in each leaf segment (LF1, 6, 10, and 15) were further verified by qRT-PCR data. The results were positively correlated with RPKM values (Additional files 11 and 12), demonstrating the reliability of gene expression results based on RNA-seq analysis.

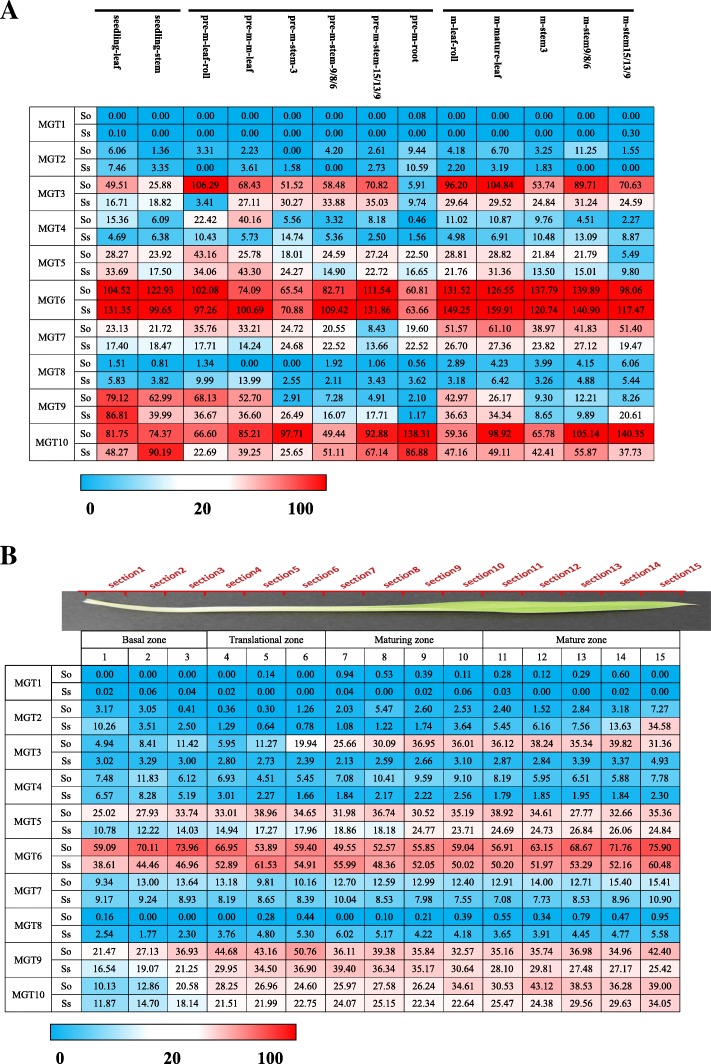

In the SaccharumMGT families, transcription of MGT1 was undetectable in all the examined tissues from Sacchaurm plants.MGT2/4/5/8 presented low expression in all the examined tissue (Fig. 5a).MGT6, MGT9 andMGT10 had predominant expression levels among the gene families, indicating that the 3 genes were the main members in the MGT families.MGT3/7/10 showed varying expression levels in the examined tissues from the 2 Saccharum species.

Fig. 5.

a The expression pattern of MGTs based on RPKM in 2 Saccharum species. b The expression patterns of MGTs based on RPKM across leaf segments in 2 sugarcane species

Expression pattern of MGTs at different developmental stages

To investigate gene functional divergence among the Saccharum species, we analyzed the transcriptome profile of MGTs among 2 Saccharum species, S. officinarum and S. spontaneum, at 3 developmental stages and in 6 different tissues, including the 2 leaf (leaf, leaf roll) and 3 stalks (mature, maturing and immature) and the root tissue of pre-mature Saccharum (Fig. 5a, Additional file 13). Among the 10 MGTs analyzed, 4 genes (MGT1, MGT2, MGT4 and MGT8) displayed very low or undetectable levels in all the examined tissues. MGT3 presented higher expression levels in leaf and mature stem (sink tissues) at the mature stage than the young tissues, higher in S. officinarum than in the S. spontaneum, and higher in the leaf than in the stem. MGT6 was the most highly expressed gene among the gene families and displayed a constitutive expression pattern.Both MGT5 and MGT9 were observed to have higher expression levels in leaf tissues including the mature leaf and leaf roll than in the stems and root. In leaf tissue, MGT9 expression levels were observed to decrease gradually during the development of the Saccharumspecies, and MGT9 likely functions in the seedling period of sugarcane development. In contrast to MGT5 and MGT9, MGT10 was abundant in the examined tissues and presented higher expression levels in mature stems than in other tissues.

Expression pattern of MGT under hormone treatment

Phytohormone-mediated regulation of gene expression plays the crucial role in plant growth and development. After subjected to magnesium deficiency and magnesium toxicity stress, abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene and other signal transduction related hormone concentrations and its transporter’s expression levels in Arabidopsis thaliana were significantly up-regulated or down-regulated [36–38]. In this research, we analyzed the gene expression in the leaves of seedlings of Saccharum plants treated with ABA and GA. Gene expression levels were altered in response to ABA or GA treatment, especially for MGT3, MGT4, MGT9 and MGT10 (Additional file 14). Furthermore, the gene expression of different MGTs varied in response to different ABA treatment times. For instance, SoMGT3 and SoMGT9 showed a rise sharply in leaf, whereas SsMGT4 in leave, SoMGT8, SoMGT9, SsMGT10 and SoMGT10 in stem were decreased its expression level as the ABA treatment time was increased. Under GA treatment, the expression of SoMGT2, SoMGT3 and SsMGT9 was induced in leaf, the transcript of SoMGT4 and SoMGT5 wasinduced in the stem tissue. The expression of MGT10 was suppressed in the stem tissue. The transcript of SsMGT4 was inhibited in the leaf tissue at 48 h and 96 h, but was induced in the stem tissues at 96 h.

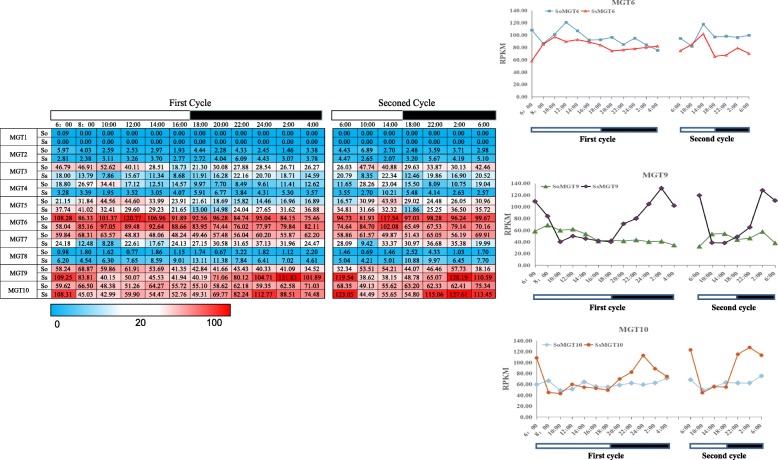

Expression pattern of MGTs during the circadian rhythms

Since Mg is the central element in chlorophyll [3] and the plantsphotosynthetic apparatus is regulated by the circadian clock at the transcriptional level [39], we performed gene expression analysis for MGT during the diurnal cycles in the 2 Saccharum species.MGT9 and MG10 were observed to have a peak expression in the middle of the night period in S. spontaneum, but showed no diurnal expression in S. officinarum, indicating diurnal rhythms regulate these 2 MGTs in S. spontaneum rather than S. officinarum (Fig. 6). In contrast, the dominant MGT6 displayed a diurnal expression pattern with peak levels in the middle of the day in both of the 2 analyzed Saccharum species, suggesting MGTs correlate with diurnal rhythms in Saccahrum (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The expression pattern of MGTs based on RPKM in circadian rhythms

Expression pattern of MGTs in different developmental gradient of the leaf

To further understand the functional divergence for photosynthesis, we exploited the continuous developmental gradient of the leaf transcriptome of MGTs in maize, rice and 2 Saccharum species (Fig. 5b, Additional file 15). Consistently, 4 genes (MGT1, MGT2, MGT4 and MGT8) displayed very low or undetectable expression levels in all the examined segments of the leaf tissues (Fig. 5b). The expression of MGT3 and MTG5 gradually increased from the base to the tip of the leaf in S. officinarum and showed higher expression levels in S. officinarum than in S. sponteneum, indicating gene functional divergence after the split of S. spontaneum and S. officinarum. MGT6 presented abundant expression level in all the examined leaf segments, further supporting that this gene is aconstitutively expressed gene in the MGT family. MGT9’s expression was high in the translational zone but low in the basal zone. MGT10 displayed gradually increase expression from the base to the tip of the leaf in both of the 2 analyzed Saccharum species.

SsMGT3 complements a S. typhimurium strain MM281 deficient in Mg2+ uptake

To verify the SsMGTs function for magnesium transportation, we transferred the SsMGT3to Salmonellatyphimurium strain MM281 which is lack of Mg-transporting systems [16, 40, 41]. The MM281 cells do not survive in the low-Mg medium (< 1 mM) at pH 7.5 [42], but the transformed MM281 could survive in N-minimal medium containing low-Mg concentration. The result show that SsMGT3 could recover the magnesium uptake function in MM281 (Additional file 16). Supporting that SsMGTs play vital role in transporting magnesium in sugarcane.

Discussion

Mg plays a fundamental role in plants since 15–20% of total Mg participates in chloroplast formation in the leaf. Due to its tendency to form octahedral complexes, Mg also plays a predominant role as a cofactor of a series of enzymes involved in photosynthetic carbon fixation and metabolism, with the remaining fraction being stored in the vacuole [43]. The CorA gene in bacteria, the MRS2/MGT gene in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa participate in magnesium transport [16–18, 44]. Mg is typically highly mobile in plants [41]. The Mg uptaken by roots is uploaded to the xylem and transported from the root to the young leaf via long-distance transportation through stems. Due to its high mobility, Mg is also transported from old leaves to young leaves (i.e. transport from source to sink), and in a continuous supply cycle, as Mg is transported from the stem to the roots [45]. Ten members of MGT gene family were identified in Saccharum inthe monoploidy genome of AP85–441 [31]. Based on comparative genomics and gene expression patterns of the MGT families, gene evolution andtheir potential function divergence for photosynthesis wereinvestigated to further understand the mechanism of MGT in Saccharum.

WGD or polyploidization, gene deletion and diploidization, are the major driving forces for the divergence and biological diversity of angiosperms [46]. The commelinids originated from about 120 to 100 Mya, approaching to the origin of monocotyledons from about 150 to 130 [47]. Three ancient WGD events (τ, σ and ρ) occurred before the emergence of the Poaceae lineage. A recent study demonstrated that the number of WGD events in pineapple have one less ancient WGD (ρ) event than other sequenced gramineous plants [48]. In this study, we selected the MRS2/MGTs from 16 species including 14 representative plant species and 2 outgroups for phylogenetic analysis, providing the representative phylogenetic position for analyzing the gene evolution. And based on previous study about the WGD in angiosperms [48–52], along with the phylogeny relationship of MGT genes, MGT families in angiosperms have undergone over 4 rounds of gene duplications after the ε ancient WGD event. So, we put forward a hypothesis that the MGT is an ancient gene family with at least 5 LCAs prior to the emergence of angiosperms. The gene number of the 5 clades were similar among the 14 representative plant species despite the different ancient WGD events that occurred in these plant species, suggesting that gene expansion of MGT in angiosperm was not caused by ancient WGD events. It is obvious that gene loss occurred following the WGD events in the lineages of A. thaliana and lineages of Poaceae, which were mainly due to the gene functional redundancy of the MGT family as the multiple LCA existed before these WGD events. The divergence of 5 clades of the MGT gene family was estimated using the Ks in this study (Tables 3 and 4), and the results suggested that the MGT families in angiosperms (about 142~237 Mya) probably occurred before σ WGD in angiosperm (about 130 Mya) and after ε WGD in gymnosperm (about 245 Mya) [49].

By using more representative phylogenetic position for MGT family analysis, we were able to estimate the evolutionary history of the clades in duplicated descending order, clade A, clade D, clade E, clade B, and clade C. The results showed that the clade D was retained from the second gene duplication event, while clade E originated from the third gene duplication event, which is inconsistent with previous studies [17, 18]. However, the phylogenetic analysis for MGT from 2 previous studies only used 3 plant species (maize, rice and Arabidopsis) or 2 plant species (rice and Arabidopsis), making it possible that the reduced number of plant species provided insufficient information for phylogenetic construction and discrimination of clade position in the phylogenetic tree.

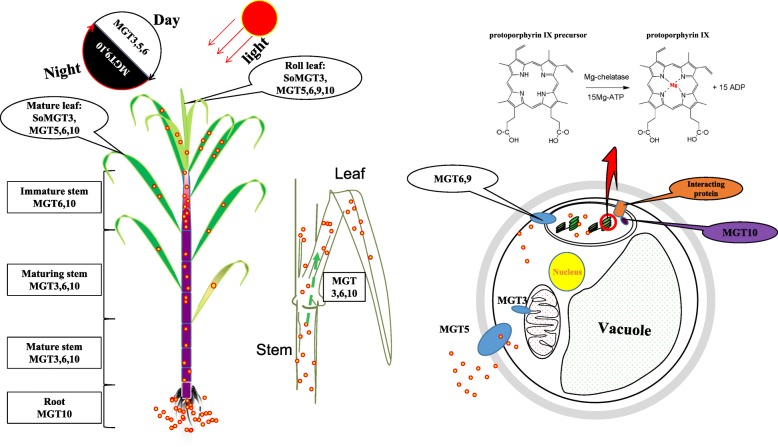

Distributed in clade A, SsMGT9 was retained from the first round of gene duplication in angiosperms. It is interesting that except pineapple, all other plant species contained at least 1 MGT in Clade A. The Ka/Ks of SsMGT9/SbMGT9 also supported SsMGT9 being under functional constraining divergence after the split of Sorghum bicolor and S. spontaneum. These results indicated the gene functional constraint of the orthologous genes.The genes in clade A contained more exons than other clades (Additional file 8). According to phylogeny relationship, Clade A belong to the older group of the MGT families. For this reason, the MGTs in clade A were speculated to have more events for introns gain/loss according to ‘introns-early’ theory during the lengthy evolutionary process [53, 54].Consequently, we assumed that the evolution of gene structures of MGTs in clade A were mainly derived by the spitted of exon [55].In Saccharum, MTG9 was one of the MGTs with highest expression levels in functional photosynthesis region, the maturing zone of leaf (Fig. 5b) and had peak expression in the middle of the night period in S. spontaneum but showed no diurnal expression pattern in S. officinarum. Moreover, the expression of SoMGT9 rise sharply in leaf and decrease in stem at ABA treatment. Under GA treatment, SsMGT9 was induced in leaf, while SoMGT9 show an unstable change in leaf. Suggesting that MGT9 may involve in the crosstalk of the gene network in response to the two hormones (Additional file 14). SsMGT9 was predicted to be located in chloroplast (Table 2), and its closest orthologous gene from both Arabidopsis (ATMGT10, At5G22830) [56] and rice (OsMRS2–6, Os03t0684400) [17] in clade A were found to be located in chloroplast. Moreover, OsMRS2–6 possessed the Mg2+ transport ability to transport Mg into the chloroplast matrix during the day as a chloroplast device [17]. Therefore, we deduced that MGT9 plays a role as a MGT for chlorophyll formation for photosynthesis and has functional divergence between S. spontaneum and S. officianrum (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic model of MGT proteins based on gene expressions in sugarcane. MGT3 presented higher expression levels in leaves and mature stems (sink tissues) at the mature stage than that in the young tissues, in S.officinarum than in the S. spontaneum, and in leaf than in the stem. OsMGT1/OsMRS2–2 astheclosest orthologous genes of SoMGT3 specifically response to aluminum stress and salt stress at the root [58], indicating that SoMGT3 is likely to be involved in magnesium homeostasis in mature stems and leaf tissues during the light period in S. officinarum, but plays a limited role in S. spontaneum. Mg2+ is inserted into protoporphyrin IX via the magnesium-chelatase enzyme [2]. MGT6 was the most highly expressed gene among the gene families and displayed a constitutive expression pattern. It was induced by light with an expressional peak at noon. In pre-mature plants, MGT6 was highly expressed in the leaf and lowly expressed in roots. Magnesium concentrations of the chloroplast matrix in the light period were higher than in the dark period [90]. These results suggested that MTG6 is the dominant MGT for the maintenance of magnesium concentration in chloroplast during the light period in Saccharum. MGT5 and MGT9 had higher expression level in leaf than in the stems and root. In leaf, expressional level of MGT9 was gradient decrease from the base to the tip of leaf in the Saccharum, suggesting that MGT5 and MGT9 possibly played roles in leaf of sugarcane, and MGT9 probably functioned in the seeding stage of sugarcane. While MGT10 was abundant in the examined tissues and presented higher expression levels in root and mature stem than in other tissues, suggesting that MGT10 probably played a complementary role in magnesium transport in leave tissues in the light and dark period in S. spontaneum. It also may be responsible for the long-distance transport of magnesium from source (root) to sink (leaf)

In clade B, SsMGT5 was assumed to be retained from σ WGD as Aco008214.1 distributed the outgroup of subgroup of Poaceae. In Saccahrum, MGT4 and MGT5 were lowly expressed in the examined tissues and MGT5 had higher expression levels than MGT4. However, in sorghum, SbMGT4 and SbMGT5 were highly expressed in the 2 reproductive parts of the pistil and anther, respectively (Additional file 17) [57]. Thus, we can speculate that MGT4 and MGT5 in sugarcane, as the close relative of sorghum, may not participate in vegetative growth but instead participates in the development of sugarcane reproductive organs. Further experiments would be necessary for testing this hypothesis.

In clade C, SsMGT1 and SsMGT2 were assumed to be derived from the ρWGD events based on the reference phylogenetic position of Aco003216.1, SsMGT3 originated from the LCA of angiosperms, SsMGT10 retained in monocots from the gene duplication event before emergence of angiosperms. Therefore, the evolution history of these 4 MGTs could be sorted by age in duplicated descending order: SsMGT10, SsMGT3, SsMGT1/ SsMGT2.MGT1 was undetectable in all examined tissues of Sacchaurm, which is similar to the SbMGT1 expression pattern in Sorghum bicolor (Additional file 17) [57], and MGT2 had low expression levels in all the detected tissues of Saccharum. These results may be caused by gene function redundancy because of the recent ρWGD. MGT3 had higher expression levels in S. officnarum than in S. spontaneum, and was abundant in the mature zone of leaf tissues, in mature stems, and probably was induced by light (Figs. 5b and 6). In rice, the closest orthologous genes of SsMGT3 is OsMGT1/OsMRS2–2 (Os01t0869200) which provides a specific response to Al stress and salt stress in the root [58]. MGT3 is likely involved in Mg homeostasis in mature stems and in the leaves during the light period in S. officinarum but possibly plays a limited role in S. spontaneum. MGT10 was one of the most abundant genes, and its expression was repressed during the light period (Figs. 6 and 7, Additional file 18). These results led us to hypothesize MGT10 is the predominant MGT for maintaining the Mg concentration in chlorophyll during the night period in Saccharum. It is interesting that the gene expression correlates with the evolutionary history of the 4 MGTs in Saccharum, as demonstrated by the results that rank the expression levels as SsMGT10 > SsMGT3 > SsMGT1/SsMGT2.

In clade D, SsMGT7 and SsMGT8 originated from the LCA of the second-round gene duplication in angiosperms by a recent gene duplication event which occurred after the divergence of monocots and dicots. Comparing with other species in the clade, SsMGT7 and SsMGT8 have 1 and 2 more exons, and the two gene sizes were larger than those of other MGTs in monocotyledon plants. Their structure may be underwent exon/pseudoexon in recent replication events [19], while the intron structure may be generated from the Intron transposition/ transposon insertion/tandem genomic duplication/ Intron transfer or self-splicing type II intron, so we analyzed these two MGTs exon distribution basing on CDS sequence (Additional file 19), the exon 1 in MGT7 was likely originated from exonization event after the spilt of sorghum and Saccharum, similarly, the exon 5 and exon 6 in MGT8 were indicated to be caused by exonization event after the spilt of sorghum and Saccharum. These exonization were predicted to located in the non-conserved regions of the MGTs, thus may not have strong effect on the functional divergence. MGT7 presented higher expression levels than MGT8 in the examined tissues of Saccharum and have higher expression level in the high sucrose S. officinarum than in S. spontaneum (Fig. 5). In Arabidopsis, the closest orthologous gene, AtMGT6(AT3G58970), was found to be sensitive to Mg deficiency since the gene was strongly induced by Mg2+ deficiency in cortex and epidermal cells, including root hairs [22]. Thus, MGT7 was assumed to have functional divergence between the 2 Saccharum species and may give rise to the response to Mg deficiency in sugarcane.

In clade E, SsMGT6 was the single gene retained from the common third round of gene duplication event of the MGT families (Fig. 4). MGT6 was the most abundant gene among the MGT families and was induced by light with the expression peak at the noon (Fig. 6), suggesting that MTG6 was the dominant MGT to maintain the Mg concentration in chlorophyll during the light period in Saccharum. In Spinacia oleracea. L., Mg concentration in stroma was observed to be markedly higher in the light period than in the dark period [59]. It is possible that MGT6 plays a role in the transport of Mg ions to the stroma in the chloroplast matrix during daylight. Of note, the 3 dominant MGTs, MGT6, MGT9 and MTG10 may have a complementary function for the transport of Mg in the leaf tissue in the light and dark period in S. spontaneum (Fig. 7).

Conclusions

In this research, we identified ten SsMGTs in the monoploid genome of Saccharum spontaneum. The Ks analysis suggested that SsMGT family is an ancient gene family with recent gene duplication events in Poaceae. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, MGT genes were predicted to contain at least 5 LCAs before the origin of angiosperms. SsMGT1/SsMGT2 were observed tooriginate from the recent ρWGD, while SsMGT7/SsMGT8 were duplicated after the split of dicots and monocots. The truncation of MGT10 was caused by the pre-mature stop coding. The exon 1 in MGT7 and the exon 5 and exon 6 in MGT8 were likely originated from exonization event after the spilt of sorghum and Saccharum. These 4 genes were observed to have low expression levels in Saccharum, indicating potential functional redundancy caused by the recent duplication of MGTs. Three MGTs, MGT6, MGT9 and MGT10, weredominantly expressed among the MGT families in the tissues of Saccharum. MGT6’s gene expression was induced in the light period in S. spontaneum and S. officinarum, while, MGT9 and MTG10 displayed higher expression levels in the dark period in S. spontaneum, suggesting that MGT6 may have a function to complementary MGT9 and MTG10 which is regulated by the circadian clock for MGT in the leaf tissues in S. spontaneum. The remaining 3 MGTs, MGT3, MGT5 and MGT7, had higher expression levels in S. officinarum than in S. spontaneum, suggesting their functional divergence after the split of S. spontaneum and S. officinarum. To further understand the function of MGTs in Saccharum, experiments such as targeted gene regulation network based on gene expressional profiles, gene over-expression, enzyme activity, and gene knock out technology like CRISPR-Cas9 system, would be necessary. Our study provides the foundation work for the future study of the MGT gene family to characterize the physiological role and molecular mechanisms leading to photosynthesis in sugarcane. The functional complementarity experiment result inSalmonella typhimurium strain MM281 suggested that the function of SsMGTs issimilar with that of OSMRS2/MGTs and ZmMGTs, namely transporting magnesium in sugarcane.

Methods

Plant materials

Two founding Saccharum species, S. spontaneum SES208 (Ss, 2n = 8x =64, originated in USA) and S. officinarum LAPurple (So, 2n = 8x = 80, originated in USA), were used for the gene expression pattern analysis [60]. The plant material was identified by Irvine JE [61], and These Saccharum species were planted in the campus of Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University (Fuzhou, China).

For expression pattern analysis at different developmental stages, samples were collected from 12-month old plants (mature plants) and 9-month old plants (pre-mature plants) for leaf roll, leaf (full expansion leaf), top immature internode (i.e. internode number 3), premature internode (i.e. internode number 9 for ‘LA Purple’ due to short internode, and internode number 6 for SES208 due to long internode) and mature internode (i.e. internode number 15 for ‘LA Purple’ and internode number 9 for SES208 due to long internode – most SES208 plants have about 12 internodes). The internodes were numbered from top to bottom according to the protocol for sugarcane established by Moore [62]. Stem and leaf tissues from seedlings of these 2 species were collected 35 days after planting [63, 64].

Leaves from the mature plants of LAPurple and SES208 were collected to investigate the gene expression under circadian rhythms. In this experiment, from 6 a.m. on March, 22,017 to 4 a.m. on March 3, 2017, samples were collected at 12 time points (6 a.m., 8 a.m., 10 a.m., noon, 2 p.m., 4 p.m., 6 p.m., 8 p.m., 10 p.m., midnight, 2 a.m., 4 a.m.) for RNA isolation. In addition, 7 time points (at 4 h intervals) were collected for a second round of circadian rhythms. The sunset time on 2nd March 2017 was 6 p.m. in Fuzhou. The method was previously described [48, 65].

Similarly, both LAPurple and SES208 were used for the developmental gradient of the leaf experiment. 2 Saccharum species plants were grown under the following conditions: light intensity of 350 μmol/m2/sec, 14:10 l/D, 30 °C L/22 °C D and 60% relative humidity. Tissues were collected from 11-day-old second leaves of the Saccharum plants, and 15-day-old second leaves of LApurple after planting 3 h into the light period. These leaves were cut into 15 1-cm segments. Samples were pooled from an average of 4 plants per biological replicate and 3 biological replicates in total were prepared. The tissues collection approach followed for this experiment was previously described [65, 66].

The plants for hormone treatment were grown in a growth chamber at 30 °C, 70% RH, and a 14 h:10 h L:D photoperiod. Seedlings were treated with GA (200 μM), ABA (200 μM) for 24, 48, and 96 h. Stem and leaf tissues from the seedlings of the two-sugarcane species were collected from 35-day-old plants [63].

Collected tissues were frozen immediately using liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C prior to RNA isolation. The RNA-seq method that was used in this study are followed by our previous work [63, 64].

Database search for the MGTs gene family

Ten and 9 MRS2/MGT proteins were obtained from the TAIR [67] and TIGR [68] databases, respectively [16–18]. Putative members of the MRS2/MGT gene family in the sorghum genome were identified using the BLASTP program from the Phytozome V12.1 [69], with Arabidopsis and rice MRS2/MGT protein sequences as queries. Sequences with e-values < 10− 10 were selected as the preliminary MRS/MGT candidates. Subsequently, we used SbMGTs as query sequences to BLAST search the MGT from representative monoploidy genome S. spontaneum genome [31].

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic tree

The CDS sequences of the MGT genes were translated into protein sequences by the ExPASy Translate tool [70]. The putatively conserved domains of MGT proteins were detected using BLASTp [71] and InterPro [72]. The isoelectric point and relative molecular mass of the proteins were predicted using ExPASy Compute pI/Mw tool [73]. The exon-intron structures for the MGT genes were drawn using the TBtools [74], the transmembrane domain of the MGTs were predicted by TMHHM [75], and the subcellular location predicted by WOLF PSORT [76].

The amino acid sequences of MRS2/MGT gene family members in 9 monocotyledons (Zea mays, Sorghumbicolor, Oryzasativa, Brachypodiumdistachyon, Ananas comosus, Setaria viridis, Setaria italica, Saccharum cultivar R570 and S. spontaneum), 5 dicotyledons (Arabidopsisthaliana, Carica papaya, Amborellatrichopoda, Solanumlycopersicum and Vitisvinifera) and 2 Chlorophyta species (Dunaliella salina and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) were identified by searching public databases available from various resources.

The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining(NJ) method [77]. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches [78]. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method [79] and were in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The analysis involved 149 amino acid sequences [80]. The Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree was also constructed by MEGA7, with 100 nonparametric bootstrap replicates. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model, and then the topology with superior log likelihood value was selected.

The non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution ratios of the 10 pairs of orthologous genes from sorghum and sugarcane were calculated by the easy_kaks calculation program [81]. Meanwhile, Fisher’s exact test for small samples was applied to verify the validity of Ka and Ks calculated by this method [82]. The divergence time (T) was calculated by T = Ks/ (2 × 6.1 × 10− 9) × 10− 6 Mya [83].

Analysis of the expression profile of MGTs in Saccharum based on RNA-seq

Five μg total RNA of each sample was used for the construction of cDNA libraries. The cDNA libraries were prepared using Illumina® TruSeq™ RNA Sample Preparation Kit (RS-122–2001(2), Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA-seq libraries were pooled and sequenced with 100 single reads on Illumina HiSeq2500 at the Center for Genomics and Biotechnology at the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University.

Raw data was aligned to reference gene models using TRINITY [84]. Trinity combines 3 independent software modules: Inchworm, Chrysalis, and Butterfly, applied sequentially to process large volumes of RNA-seq reads. Trinity partitions the sequence data into many individual de Bruijn graphs, each representing the transcriptional complexity at a given gene or locus, and then processes each graph independently to extract full-length splicing isoforms and to tease apart transcripts derived from paralogous genes. There is 59.84% overall alignment rate in this study.

Sub-cellular localization analysis

GATEWAY technology (Invitrogen) was used in this study, a translational fusion between each isolated gene and GFP was designed. The attB recombination sites: 5′- GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTG (for the forward primer) and 5′- GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTG (for the reverse primer), PCR products were used in a BP clonase reaction for recombination into the p207-DONOR vector. Positive clones were then used in an LR clonase reaction for recombination into the pMDC84 destination vector, which contains two copies of the 35S promoter [85]. A. tumefaciens was transformed with the expression vectors and then agroinfiltrated in Nicotiana tabacum cv. Petite Havana (SR1) leaves. Middle leavesfrom seven-week-old plants were infiltrated with an A. tumefaciens culture grown for 2 days at 28 °C, the leaf was used to localize GFP fluorescence by a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8X DLS).

Validation of RPKM values for MGT genes using RT-qPCR

RNA (≤1 μg) from each sample was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Takara, Code, RR047A) in a 20 ml reaction volume with 1 ml of random primers and 1 ml of mixed poly-dT primers (18–23 nt). The cDNA was diluted 1:19 in water for further RT-qPCR experiments. Specific primers (S1) were designed by Integrated DNA technologies [86]. The TransStart Tip Green RT-qPCR SuperMix kit was used for RT-qPCR, and the reaction cycle was: 95 °C for 30s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30s, and 95°C for 10s. The consistency of the melting curve demonstrated the reliability of RT-qPCR results. In order to normalize the expression levels, 2 constitutively expressed genes, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH) and the eukaryotic elongation factor 1a (eEF-1a) were used as reference genes, each sample had 3 biological replicates and 4 technical replicates. The relative expression levels for each MGT gene in different tissues of 2 sugarcane species were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method [87].

Additional files

The BLASTP result of ShMGTs by using SsMGTs and SbMGTs as query. (XLS 112 kb)

Divergence between a pair of tandem duplicated genes (Sh06_t004330 and Sh06_t004340) and the identity between these two genes. (PPTX 78 kb)

Transmembrane Protein Topology prediction of SsMGTs with a Hidden Markov Model. (DOC 71 kb)

The similarity between SsMGT proteins was calculated by NCBI BLASTP. (DOC 34 kb)

Amino acid sequences of 16 species. (FASTA 133 kb)

Phylogenetic analysis of MGTs from 16 plant species by Maximum Likelihood method. (PDF 53 kb)

A schematic diagram for the relationship of the 5 clades of the phylogenetic tree constructed by NJ method. (DOC 170 kb)

The exon number of MGTs. (XLS 38 kb)

The proportion of the same number of exons in all MGTs. (DOC 25 kb)

The non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution ratios of each MGTs from 10 representative plants. (XLSX 804 kb)

RT-qPCR of SsMGT. (DOC 51 kb)

: qRT-PCR primers. (DOC 29 kb)

The expression levels of MGTs in S. officinarum based on RPKM in parenchyma cells and sclerenchyma cells from S. officinarum. (DOC 32 kb)

The expression patterns of MGTs with hormone treatment. (PDF 1945 kb)

Expression patterns of MGT genes across leaf gradient segments in maize and rice [88]. (XLSX 24 kb)

Complementation of the MM281 mutant by SsMGT3. (PDF 418 kb)

The expression patterns of MGTs in Sorghumbicolor based on qTeller [57, 89]. Abbreviation: Lvs: Young leaves were harvested 20 days after sowing; stg1inf: Primodial inflorescences were harvested 10 days before flower emergence; stg2inf: Whole inflorescences were harvested at the time of flower emergence; anth: Whole anthers were harvested at the time anthesis; pist: Pistils were harvested at the time anthesis; sd5: Whole seeds were harvested 5 days after pollination; sd10: Whole seeds were harvested 10 days after pollination; emb: Developing embryos were harvested 25 days after pollination; endo: Developing endosperms were harvested 25 days after pollination. (DOC 58 kb)

Subcellular localization of SoMGT10, SoMGT10 were localized to the chloroplast in tobacco. 35S:SoMGT10–GFP constructs were introduced into tobacco, and fluorescence was visualized by confocal laser microscopy. Bars = 25 μm. (PPTX 7792 kb)

The exon-intron structures of MGT genes in sugarcane, sorghum, maize, millet, green bristle grass and rice. The corresponding exons with similar sequences based on sequence alignments were indicated with solid lines. Sequence similarity values are shown as percentage. Exons that had experienced exon gain events are labeled with blue box, and exonization/ pseudoexonization events are labeled with red box. For gene IDs, Ss indicates S. spontaneum, Sh indicates Saccharum hybrids, Sb indicates Sorghum bicolor, GRMZM indicates Zea mays, Seita indicates Setaria italic, Sevir indicates Setaria viridis and Os indicates Oryza sativa. A. SsMGT7, B. SsMGT8. (PDF 13824 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Professor Legong Li (College of Life Sciences, Capital Normal University, China) for providing Salmonella typhimurium strain MM281, MM1927 and plasmid pTrc99A.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Fujian Province, the 863 program (SS2013AA100604), NSFC (31201260) and Science and Technology Major Project of Fujian Province (2016NZ0001). Yongjun Wang is supported by the K + S scholarship from the International Magnesium Institute, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. These funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The gene sequences of MGTs were deposited in NCBI with accession NO. MH379211-MH379220.The S. spontaneum genome project [31] was deposited into Genbank with accession numbers: QVOL00000000.

Abbreviations

- eEF-1a

Eukaryotic elongation factor 1a

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- Ka

Non-synonymous

- Ks

Synonymous

- LCA

Last common ancestor

- MGT

Magnesium transport

- ORFs

Open reading frames

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq

RNA Sequencing

- RPKM

Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

- WGD

Whole genome duplication

Authors’ contributions

YW, XH and JZ conceived the study and designed the experiments. YW, XH, JX, ZC, TF, ZZ, HW, ALH, QY, RM and JZ carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. JZ, YW, and XH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yongjun Wang, Email: yongjunwang_123@163.com.

Xiuting Hua, Email: xiutinghua@126.com.

Jingsheng Xu, Email: xujingsheng@126.com.

Zhichang Chen, Email: zcchen@fafu.edu.cn.

Tianqu Fan, Email: 15923245151@163.com.

Zhaohui Zeng, Email: 18065193769@163.com.

Hengbo Wang, Email: wanghengbo_0354@126.com.

Ai-Ling Hour, Email: 022446@mail.fju.edu.tw.

Qingyi Yu, Email: qyu@ag.tamu.edu.

Ray Ming, Email: rming@life.uiuc.edu.

Jisen Zhang, Email: zjisen@126.com.

References

- 1.Chen ZC, Peng WT, Li J, Liao H: Functional dissection and transport mechanism of magnesium in plants. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;74:142–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Black JR, Yin Q-z, Casey WH. An experimental study of magnesium-isotope fractionation in chlorophyll-a photosynthesis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;70(16):4072–4079. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beale SI. Enzymes of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 1999;60(1):43–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maguire ME, Cowan JA. Magnesium chemistry and biochemistry. Biometals. 2002;15(3):203–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1016058229972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaul O. Magnesium transport and function in plants: the tip of the iceberg. Biometals. 2002;15(3):307–321. doi: 10.1023/a:1016091118585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knoop V, Groth-Malonek M, Gebert M, Eifler K, Weyand K. Transport of magnesium and other divalent cations: evolution of the 2-TM-GxN proteins in the MIT superfamily. Mol Gen Genomics. 2005;274(3):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rengel Z, Bose J, Chen Q, Tripathi B. Magnesium alleviates plant toxicity of aluminium and heavy metals. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016;66(12):1298–1307. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Zhou M, Walsh J, Zhu L, Chen Y, Ming R. Sugarcane genetics and genomics. In: Sugarcane: physiology, biochemistry, and functional biology. Edited by Moore PH, Botha FC. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2014. p. 623–43.

- 9.Cakmak I, Yazici AM. Magnesium: a forgotten element in crop production. Better Crops. 2010;94(2):23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aitken R, Dickson T, Hailes K, Moody P. Response of field-grown maize to applied magnesium in acidic soils in North-Eastern Australia. Aust J Agric Res. 1999;50(2):191–198. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez PA, Logan TJ. Myths and science about the chemistry and fertility of soils in the tropics. SSSA Spec Publ. 1992;29:35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verbruggen N, Hermans C. Physiological and molecular responses to magnesium nutritional imbalance in plants. Plant Soil. 2013;368(1–2):87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermans C, Hammond JP, White PJ, Verbruggen N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(12):610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RL, Gottlieb E, Kucharski LM, Maguire ME. Functional similarity between archaeal and bacterial CorA magnesium transporters. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(10):2788–2791. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2788-2791.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith R, Banks J, Snavely M, Maguire M. Sequence and topology of the CorA magnesium transport systems of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Identification of a new class of transport protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(19):14071–14080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Tutone AF, Drummond RS, Gardner RC, Luan S. A novel family of magnesium transport genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13(12):2761–2775. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito T, Kobayashi NI, Tanoi K, Iwata N, Suzuki H, Iwata R, Nakanishi TM. Expression and functional analysis of the CorA-MRS2-ALR-type magnesium transporter family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54(10):1673–1683. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Du H, Huang K, Chen X, Liu T, Gao S, Liu H, Tang Q, Rong T, Zhang S. Identification, and functional and expression analyses of the CorA/MRS2/MGT-type magnesium transporter family in maize. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57(6):1153–1168. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu G, Guo C, Shan H, Kong H. Divergence of duplicate genes in exon–intron structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(4):1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109047109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Li L-g, Liu Z-h, Yuan Y-j, Guo L-l, Mao D-d, Tian L-f, Chen L-b, Luan S, Li D-p. Magnesium transporter AtMGT9 is essential for pollen development in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2009;19(7):887. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Yang R, Li L, Huang J. The magnesium transporter MGT10 is essential for chloroplast development and photosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2017;10(12):1584–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao D, Chen J, Tian L, Liu Z, Yang L, Tang R, Li J, Lu C, Yang Y, Shi J. Arabidopsis transporter MGT6 mediates magnesium uptake and is required for growth under magnesium limitation. Plant Cell. 2014. 10.1105/tpc.114.124628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chen ZC, Yamaji N, Horie T, Che J, Li J, An G, Ma JF. A magnesium transporter OsMGT1 plays a critical role in salt tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2017;174(3):1837–1849. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Wang N, Ding J, Liu C, Du H, Huang K, Cao M, Lu Y, Gao S, Zhang S. The maize CorA/MRS2/MGT-type mg transporter, ZmMGT10, responses to magnesium deficiency and confers low magnesium tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;95(3):269–278. doi: 10.1007/s11103-017-0645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lifang H. Effects of phosphorus, potassium, sulfur, and magnesium on sugar cane yield and quality in Yunnan. Better Crops Int. 2001;15(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh V, Shukla A, Gill M, Sharma S, Tiwari K. Improving sugarcane productivity through balanced nutrition with potassium, sulphur, and magnesium. Better Crops India. 2008;24:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gransee A, Führs H. Magnesium mobility in soils as a challenge for soil and plant analysis, magnesium fertilization and root uptake under adverse growth conditions. Plant Soil. 2013;368(1–2):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber DM, Jones JB. The role of magnesium in plant disease. Plant Soil. 2013;368(1–2):73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo W, Nazim H, Liang Z, Yang D. Magnesium deficiency in plants: an urgent problem. Crop J. 2016;4(2):83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asano T, Tsudzuki T, Takahashi S, Shimada H, Kadowaki K-i. Complete nucleotide sequence of the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) chloroplast genome: a comparative analysis of four monocot chloroplast genomes. DNA Res. 2004;11(2):93–99. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Zhang X, Tang H, Zhang Q, Hua X, Ma X, Zhu F, Jones T, Zhu X, Bowers J, et al. Allele-defined genome of the autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum L. Nat Genet. 2018;50(11):1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Huang Y, Tan H, Yang X, Tian L, Luan S, Chen L, Li D. An endoplasmic reticulum magnesium transporter is essential for pollen development in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2015;231:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garsmeur O, Droc G, Antonise R, Grimwood J, Potier B, Aitken K, Jenkins J, Martin G, Charron C, Hervouet C. A mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2638. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palombo I, Daley DO, Rapp M. Why is the GMN motif conserved in the CorA/Mrs2/Alr1 superfamily of magnesium transport proteins? Biochemistry. 2013;52(28):4842–4847. doi: 10.1021/bi4007397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alder MN, Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Glazko GV, Cooper MD, Pancer Z. Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate. Science. 2005;310(5756):1970–1973. doi: 10.1126/science.1119420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheng Y, Ding Y, Fu Y, Yang D, Liang Z, Guo W. The research development of the response mechanisms to magnesium stresses in plants. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermans C, Vuylsteke M, Coppens F, Cristescu SM, Harren FJ, Inzé D, Verbruggen N. Systems analysis of the responses to long-term magnesium deficiency and restoration in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2010;187(1):132–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo W, Cong Y, Hussain N, Wang Y, Liu Z, Jiang L, Liang Z, Chen K. The remodeling of seedling development in response to long-term magnesium toxicity and regulation by ABA–DELLA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55(10):1713–1726. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodd AN, Kusakina J, Hall A, Gould PD, Hanaoka M. The circadian regulation of photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2014;119(1–2):181–190. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9811-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hmiel S, Snavely M, Florer J, Maguire M, Miller C. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: genetic characterization and cloning of three magnesium transport loci. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(9):4742–4751. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4742-4751.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kehres DG, Maguire ME. Structure, properties and regulation of magnesium transport proteins. Biometals. 2002;15(3):261–270. doi: 10.1023/a:1016078832697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L-G, Sokolov LN, Yang Y-H, Li D-P, Ting J, Pandy GK, Luan S. A mitochondrial magnesium transporter functions in Arabidopsis pollen development. Mol Plant. 2008;1(4):675–685. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo W. Chapter 11 - Magnesium homeostasis mechanisms and magnesium use efficiency in plants. In: Plant Macronutrient Use Efficiency. Edited by Hossain MA, Kamiya T, Burritt DJ, Tran L-SP, Fujiwara T: Academic Press; 2017:197–213.

- 44.Bui DM, Gregan J, Jarosch E, Ragnini A, Schweyen RJ. The bacterial magnesium transporter CorA can functionally substitute for its putative homologue Mrs2p in the yeast inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(29):20438–20443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang R-J, Luan S. Regulation of calcium and magnesium homeostasis in plants: from transporters to signaling network. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017;39:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leitch A, Leitch I. Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science. 2008;320(5875):481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1153585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiao Y, Li J, Tang H, Paterson AH. Integrated syntenic and phylogenomic analyses reveal an ancient genome duplication in monocots. Plant Cell. 2014. 10.1105/tpc.114.127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Ming R, VanBuren R, Wai CM, Tang H, Schatz MC, Bowers JE, Lyons E, Wang M-L, Chen J, Biggers E. The pineapple genome and the evolution of CAM photosynthesis. Nat Genet. 2015;47(12):1435. doi: 10.1038/ng.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011;473(7345):97. doi: 10.1038/nature09916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku H-M, Vision T, Liu J, Tanksley SD. Comparing sequenced segments of the tomato and Arabidopsis genomes: large-scale duplication followed by selective gene loss creates a network of synteny. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(16):9121–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160271297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennetzen JL, Schmutz J, Wang H, Percifield R, Hawkins J, Pontaroli AC, Estep M, Feng L, Vaughn JN, Grimwood J. Reference genome sequence of the model plant Setaria. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):555. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Consortium TG. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485(7400):635. doi: 10.1038/nature11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogozin IB, Sverdlov AV, Babenko VN, Koonin EV. Analysis of evolution of exon-intron structure of eukaryotic genes. Brief Bioinform. 2005;6(2):118–134. doi: 10.1093/bib/6.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeffares DC, Mourier T, Penny D. The biology of intron gain and loss. Trends Genet. 2006;22(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy SW, Gilbert W. The evolution of spliceosomal introns: patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(3):211. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drummond R, Tutone A, Li Y-C, Gardner R. A putative magnesium transporter AtMRS2-11 is localized to the plant chloroplast envelope membrane system. Plant Sci. 2006;170(1):78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davidson RM, Gowda M, Moghe G, Lin H, Vaillancourt B, Shiu SH, Jiang N, Robin Buell C. Comparative transcriptomics of three Poaceae species reveals patterns of gene expression evolution. Plant J. 2012;71(3):492–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen ZC, Yamaji N, Motoyama R, Nagamura Y, Ma JF. Upregulation of a magnesium transporter gene OsMGT1 is required for conferring aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2012. 10.1104/pp.112.199778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Ishijima S, Uchibori A, Takagi H, Maki R, Ohnishi M. Light-induced increase in free Mg2+ concentration in spinach chloroplasts: measurement of free Mg2+ by using a fluorescent probe and necessity of stromal alkalinization. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;412(1):126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, Arro J, Chen Y, Ming R. Haplotype analysis of sucrose synthase gene family in three Saccharum species. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):314. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Irvine J. Saccharum species as horticultural classes. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(2):186–194. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore PH. Anatomy and morphology. In ‘sugarcane improvement through breeding’. (Ed. DJ Heinz). (Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands). 1987; pp. 85–142.

- 63.Chen Y, Zhang Q, Hu W, Zhang X, Wang L, Hua X, Yu Q, Ming R, Zhang J. Evolution and expression of the fructokinase gene family in Saccharum. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Q, Hu W, Zhu F, Wang L, Yu Q, Ming R, Zhang J. Structure, phylogeny, allelic haplotypes and expression of sucrose transporter gene families in Saccharum. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2419-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu W, Hua X, Zhang Q, Wang J, Shen Q, Zhang X, Wang K, Yu Q, Lin Y-R, Ming R. New insights into the evolution and functional divergence of the SWEET family in Saccharum based on comparative genomics. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):270. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1495-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li P, Ponnala L, Gandotra N, Wang L, Si Y, Tausta SL, Kebrom TH, Provart N, Patel R, Myers CR. The developmental dynamics of the maize leaf transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1060. doi: 10.1038/ng.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.TAIR [https://www.arabidopsis.org/].Accessed 8 Apr 2017.

- 68.TIGR [http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/].Accessed 8 Apr 2017.

- 69.Phytozome V12.1 [https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html].Accessed 8 Apr 2017.

- 70.ExPASy Translate [https://web.expasy.org/translate/].Accessed 31 Mar 2017.

- 71.BLASTP [https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins]. Accessed 8 Apr 2017.

- 72.Interpro [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/]. Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

- 73.ExPASy Compute pI/Mw tool [https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/]. Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

- 74.Chen CJ, Xia R, Chen H, He YH (2018). TBtools, a Toolkit for biologists integrating various HTS-data handling tools with a user-friendly interface. BioRxiv Preprint Mar. 27, 2018.

- 75.TMHHM [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/]. Accessed 3 Mar 2018.

- 76.WoLF PSORT II [https://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html]. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

- 77.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39(4):783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. New York: Academic Press. 1965;97–166.

- 80.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Easy KaKs [https://github.com/tangerzhang/FAFU-cgb/tree/master/easy_KaKs]. Accessed 26 Dec. 2017.

- 82.Graham JGU. Fisher's Exact Test. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc. 1992;155(3):395–402.

- 83.Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290(5494):1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.TRINITY [https://github.com/trinityrnaseq/trinityrnaseq/wiki].Accessed 15 June 2017.

- 85.Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 2003;133(2):462–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Integrated DNA technologies [https://www.idtdna.com/pages]. Accessed 2 Jan 2018.

- 87.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.qTeller. [http://www.qteller.com/]. Accessed 26 Dec 2017.

- 89.Wang L, Czedik-Eysenberg A, Mertz RA, Si Y, Tohge T, Nunes-Nesi A, Arrivault S, Dedow LK, Bryant DW, Zhou W. Comparative analyses of C 4 and C 3 photosynthesis in developing leaves of maize and rice. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(11):1158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Portis AR. Evidence of a low stromal Mg2+ concentration in intact chloroplasts in THE dark: I. STUDIES WITH THE IONOPHORE A23187. Plant Physiol. 1981;67(5):985–989. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.5.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The BLASTP result of ShMGTs by using SsMGTs and SbMGTs as query. (XLS 112 kb)

Divergence between a pair of tandem duplicated genes (Sh06_t004330 and Sh06_t004340) and the identity between these two genes. (PPTX 78 kb)

Transmembrane Protein Topology prediction of SsMGTs with a Hidden Markov Model. (DOC 71 kb)

The similarity between SsMGT proteins was calculated by NCBI BLASTP. (DOC 34 kb)

Amino acid sequences of 16 species. (FASTA 133 kb)

Phylogenetic analysis of MGTs from 16 plant species by Maximum Likelihood method. (PDF 53 kb)

A schematic diagram for the relationship of the 5 clades of the phylogenetic tree constructed by NJ method. (DOC 170 kb)

The exon number of MGTs. (XLS 38 kb)

The proportion of the same number of exons in all MGTs. (DOC 25 kb)

The non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution ratios of each MGTs from 10 representative plants. (XLSX 804 kb)

RT-qPCR of SsMGT. (DOC 51 kb)

: qRT-PCR primers. (DOC 29 kb)

The expression levels of MGTs in S. officinarum based on RPKM in parenchyma cells and sclerenchyma cells from S. officinarum. (DOC 32 kb)

The expression patterns of MGTs with hormone treatment. (PDF 1945 kb)

Expression patterns of MGT genes across leaf gradient segments in maize and rice [88]. (XLSX 24 kb)

Complementation of the MM281 mutant by SsMGT3. (PDF 418 kb)

The expression patterns of MGTs in Sorghumbicolor based on qTeller [57, 89]. Abbreviation: Lvs: Young leaves were harvested 20 days after sowing; stg1inf: Primodial inflorescences were harvested 10 days before flower emergence; stg2inf: Whole inflorescences were harvested at the time of flower emergence; anth: Whole anthers were harvested at the time anthesis; pist: Pistils were harvested at the time anthesis; sd5: Whole seeds were harvested 5 days after pollination; sd10: Whole seeds were harvested 10 days after pollination; emb: Developing embryos were harvested 25 days after pollination; endo: Developing endosperms were harvested 25 days after pollination. (DOC 58 kb)

Subcellular localization of SoMGT10, SoMGT10 were localized to the chloroplast in tobacco. 35S:SoMGT10–GFP constructs were introduced into tobacco, and fluorescence was visualized by confocal laser microscopy. Bars = 25 μm. (PPTX 7792 kb)