Abstract

Numerous pathogenic bacteria produce proteins evolved to facilitate their survival and dissemination by modifying the host environment. These proteins, termed effectors, often play a significant role in determining the virulence of the infection. Consequently, bacterial effectors constitute an important class of targets for the development of novel antibiotics. ExoU is a potent phospholipase effector produced by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Previous studies have established that the phospholipase activity of ExoU requires non-covalent interaction with ubiquitin, however the molecular details of the mechanism of activation and the manner in which ExoU associates with a target lipid bilayer are not understood. In this review we describe our recent studies using site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) and EPR spectroscopy to elucidate the conformational changes and membrane interactions that accompany activation of ExoU. We find that ubiquitin binding and membrane interaction act synergistically to produce structural transitions that occur upon ExoU activation, and that the C-terminal four-helix bundle of ExoU functions as a phospholipid-binding domain, facilitating the association of ExoU with the membrane surface.

Introduction

Pathogenic bacteria produce a number of effector proteins to modify the host environment, attenuate the immune response and generally facilitate their own survival and dissemination in a hostile environment. One such effector protein is the bacterial phospholipase, ExoU, produced by the Gram negative opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa (P.a.) is a leading cause of hospital-acquired pneumonia (1) and chronically infects the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients (2). P.a. utilizes a Type III secretion system (3, 4) to inject effectors directly into the host eukaryotic cell cytosol. Of the four Type III effectors expressed by P.a., ExoU is the most cytotoxic. Type III secretion of ExoU by P.a. is strongly correlated with a poor clinical outcome both in clinical studies and animal models (5–8). This suggests that the development of therapeutic agents that inhibit or abrogate ExoU activity could provide a novel means to attenuate the morbidity and mortality association with P.a. infection.

ExoU is a relatively large (74 kDa) protein and, as described below, its physiological function requires both protein-protein interactions and association with a membrane lipid bilayer. Consequently, structural biology studies using high resolution methods such as NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography are not readily applicable. Site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) employing nitroxide spin labels in conjunction with EPR spectroscopy is ideally suited for such complex systems (9). SDSL EPR is not limited by protein size or system complexity. A collection of SDSL methods have been developed that allow characterization of local structural dynamics, accessibility, membrane localization, and distance distributions between pairs of spin labels (9–16). In this review we will examine the biology of ExoU as a PLA2 phospholipase and describe our recent studies using SDSL EPR to elucidate the conformational changes and membrane interactions associated with ExoU activation.

Phospholipase activity and the requirement of a eukaryotic cofactor

Early studies in yeast transformed with a plasmid encoding ExoU showed a phenotype where both vacuolar and cytoplasmic membranes were disrupted. By tagging membrane phospholipids with radiolabeled fatty acids, Sato et al. were able to demonstrate that ExoU is a PLA2-type phospholipase (17). Although ExoU exhibits little sequence homology with other phospholipases as a whole, it does contain a highly conserved serine - aspartate catalytic dyad characteristic of cytosolic phospholipases. Interestingly, initial attempts to demonstrate phospholipase activity in vitro with purified, recombinant ExoU were unsuccessful. Work from our lab and by others eventually established that the phospholipase activity of ExoU depended on the presence of an unknown cofactor present inside eukaryotic cells (17–19). The putative cofactor appeared to be a protein, as it could be inactivated by heat or by proteolysis with trypsin. Subsequently, we found that ExoU is activated in vitro by various isoforms of ubiquitin and/or ubiquitinated proteins (20). Importantly, activation of the in vitro phospholipase activity of ExoU does not depend on any of the enzymes involved in covalent ubiquitination. Based on these observations, we formulated the hypothesis that non-covalent interaction with ubiquitin provides a template for folding ExoU into a catalytically-competent conformation. To test this hypothesis we have sought to establish that ExoU undergoes a conformational change upon interaction with ubiquitin and to define the ExoU-ubiquitin binding interface. Results of our studies indicate a prominent role for the synergistic interaction of ExoU with ubiquitin and a substrate membrane interface in its molecular mechanism of activation.

Site-directed spin labeling studies of the ExoU - membrane interactions

Crystal structures of ExoU in complex with its chaperone, SpcU, were solved by two independent groups in 2012 (21, 22). The two structures are essentially identical and show ExoU to be a multi-domain protein with a chaperone-binding domain, a catalytic domain, a so-called bridging domain, and a C-terminal four-helix bundle domain (Figure 1). Although the bridging domain was initially conceived as simply connecting the catalytic and C-terminal domains we have recently shown it to be intimately involved in ubiquitin binding (23). To date, it has not been possible to crystallize ExoU alone in the absence of its chaperone, or in complex with ubiquitin. ExoU alone is perhaps too flexible to crystallize (a structural requirement for passage through the Type III secretion system), and indeed our initial SDSL studies indicated that ExoU samples multiple conformational states in the absence of a protein cofactor (24). The reason it has not been possible to crystallize an ExoU - ubiquitin complex is not currently known.

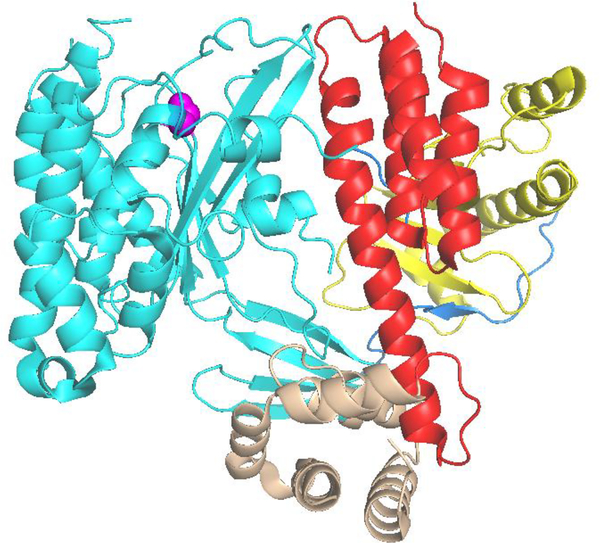

Figure 1.

Cartoon display of the ExoU-SpcU complex based on PDB entry 4AKX (21). The chaperone SpcU is in yellow. ExoU is composed of chaperone binding (blue), catalytic (cyan), bridging (brown) and membrane-binding (red) domains. The catalytic serine S142 is highlighted in magenta.

Although the reported crystal structures are of an inactive complex, they nonetheless define a domain structure for ExoU and facilitate the design of SDSL studies by providing guidance in the selection of sites for attachment of the nitroxide spin labels. To begin our interrogation of ExoU structural dynamics we focused on the C-terminal four helix bundle (see Figure 1). This region of ExoU is of particular interest as similar domains are not found in other phospholipases, although structurally similar domains have been recognized in other bacterial toxins (25, 26). Additionally, mutagenesis studies have implicated this domain as playing a key role in the membrane association of ExoU (27–30) such that this region of the protein is often referred to as the membrane localization domain or membrane binding domain (MBD).

We began by constructing forty-one variants of ExoU, each containing a single cysteine in the MBD (ExoU has no native cysteine residues). Residues were selected for modification so as to provide labeling sites throughout each of the four helices observed in the ExoU-SpcU crystal structures (see Figure 1), as well as within the three interhelical loops. Each variant was evaluated for functional integrity, with only two sites having less than 10% catalytic activity as compared to wild-type (wt) ExoU. Far UV circular dichroism (CD) indicated that all of the variants retained native-like secondary structure. Thus, we carried out structural analysis on this large collection of ExoU mutants using SDSL EPR spectroscopy (31).

Conformational changes in ExoU upon ubiquitin-membrane interaction.

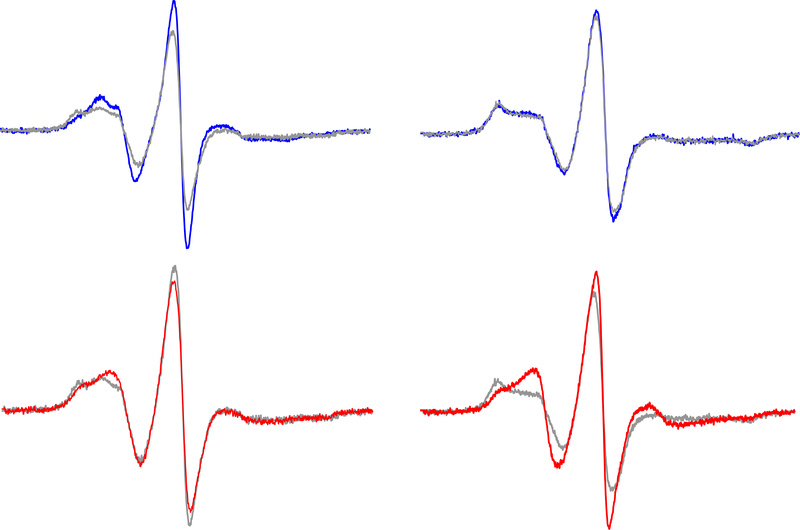

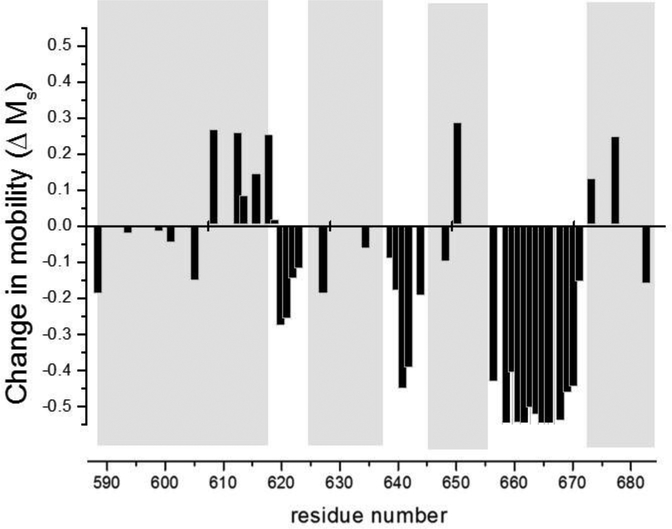

Each of the forty-one single cysteine mutants in the MBD of ExoU was spin labeled with a methanethiosulfonate spin label (32) to give the nitroxide side chain conventionally designated R1 (Figure 2), and examined by CW EPR under four experimental conditions: ExoU alone (Apo), in the presence of linear diubiquitin (diUb), in the presence of liposomes (Lipo), and in the presence of both liposomes and diUb (the holoenzyme state, Holo). CW EPR spectra are highly sensitive to the motional dynamics of the nitroxide side chain, and for spin-labeled proteins larger than ~ 20 kDa the rotational mobility of the nitroxide is determined primarily by tertiary contacts in the local environment surrounding the spin label (33–35). Consequently, a change in the EPR spectrum under a given set of conditions is indicative of a conformational change in the protein at that labeling site. Two representative examples of are shown in Figure 3 (for the full set of results for the C-terminal domain variants see reference (31)). For the first example labeled at residue N608, changes in the EPR spectrum were observed both upon addition of liposomes alone (the Lipo state, Figure 3 top left) and additional changes occurred upon the addition of both liposomes and ubiquitin (the Holo state, Figure 3 lower left). In the second example, labeled at residue 620, changes in the EPR spectrum were only observed upon transition to the Holo state (Figure 3, right). This latter result, in which local conformational changes occurred only in the Holo state, was by far the most common outcome for this collection of spin labeled ExoU variants (31). Pronounced conformational changes were observed upon transition from the Apo to Holo states for sites distributed throughout all four helices, as well as for sites in all three interhelical loops. When a parameter sensitive to spin label mobility in the Apo state was mapped onto the ExoU crystal structure we observed that the motional freedom of the nitroxide side chain was greatest in the interhelical loops and somewhat restricted within the helices, suggesting that the crystal structure accurately reflects the solution structure of ExoU in the Apo state. In addition, mapping changes in the mobility of the spin label upon transition from the Apo to the Holo state onto the crystal structure show that the interhelical loops, and in particular loop 1 (between the first and second helices) and loop 3 (between the third and fourth helices), become markedly less mobile in the presence of ubiquitin and liposomes (Figure 4). Finally, these studies indicate that a full conformational change in ExoU to its activated state requires interaction with both ubiquitin and a target membrane bilayer, at least in the C-terminal four-helix MBD.

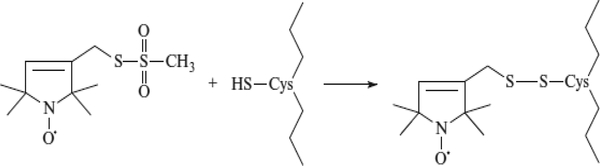

Figure 2.

Labeling scheme. Attachment of the methanethiosulfonate spin label MTSL to a cysteine residue in a protein or peptide introduces the nitroxide side chain designated R1.

Figure 3.

Conformational changes in ExoU upon activation. Representative continuous-wave (CW) EPR spectra for sites N608R1 (left) and R620R1 (right). At top are superimposed spectra in the Apo (blue) and Lipo (gray) states. At bottom are superimposed spectra in the Lipo (gray) and Holo (red) states. For the full set of forty-one labeling sites in the C-terminal MBD see reference (31).

Figure 4.

Changes in spin label mobility upon activation of ExoU. Histogram showing the change in scaled mobility (positive values indicate increased motion, negative values decreased motion) as a function of labeling site upon transition from the Apo to the Holo state. The gray panels correspond to the four helices identified in the ExoU-SpcU crystal structures (helix 1 – 4, left to right, respectively) and the white regions correspond to interhelical loops 1 – 3 (left to right, respectively). Significantly decreased motion was observed in all three interhelical loops.

Membrane association of ExoU

One of the most useful methodologies in SDSL is the ability to determine the location of the a spin label in a membrane bilayer based on its accessibility to paramagnetic relaxation agents such as molecular oxygen and metal ion complexes like nickel ethylenediaminediacetic acid (NiEDDA) (9, 36). Bimolecular collisions between a spin label and a given relaxation agent shorten the nitroxide spin-lattice relaxation time (T1), and these changes can be measured by either power saturation or saturation recovery EPR methods (37, 38). Based on the differential accessibility of the spin label to O2 and NiEDDA, which have inverse concentration gradients across a lipid bilayer, an EPR depth parameter (Φ) can be determined (9, 36). Calibration with lipid-analog spin labels of known depth then allows precise localization of the protein-bound nitroxide relative to the phospholipid head group (36). This methodology has previously been used to characterize the membrane interactions of antimicrobial peptides (39, 40), C2 membrane-binding domains of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (41) and protein kinase A (42), and a wide variety of other peripheral and integral membrane proteins (43–48).

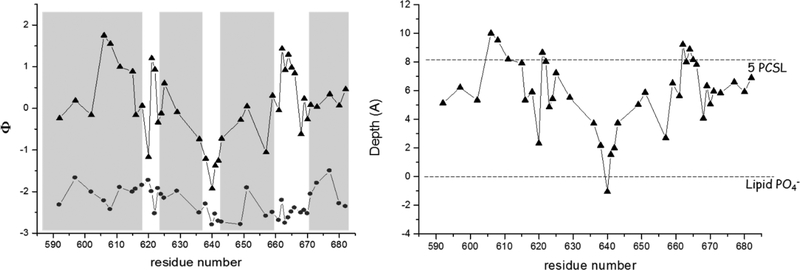

EPR depth parameters were determined for our collection of C-terminal MBD mutants in the Apo, Lipo, and Holo states using large unilamellar vesicles with a lipid composition mimicking the inner surface of the eukaryotic plasma membrane (31). In the Apo state we observed high accessibility to NiEDDA that as a function of labeling site followed a pattern that was again consistent with the expected secondary structure elements observed in the crystal structure, i.e. increased collision rates in the interhelical loops and somewhat diminished interactions within the helices. EPR depth parameters for sites in the Apo state were consistent with values expected for the aqueous phase (Figure 5), and no significant changes were observed upon addition of ubiquitin. We also examined membrane interaction in the presence of liposomes alone (the Lipo state) using a membrane composition representative of the inner leaflet of the eukaryotic plasma membrane, including a low concentration (1 mol %) of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Although ExoU is capable of hydrolyzing a broad range of phospholipids (49) it has a particularly high binding affinity for PIP2 (21, 50) and it has been suggested that hydrolysis of PIP2 is the initial step in cytoskeletal collapse and disruption of membrane integrity (51). In the Lipo state, several residues in the first and fourth helices penetrated the membrane to a depth of 4 – 6 Å, and a number of sites aligned with the headgroup phosphate (31). However, even more significant membrane interaction was observed in the Holo state, in the presence of both liposomes and ubiquitin. In the Holo state, a majority of sites were positioned 2 – 6 Â below the lipid phosphate, placing them in the interfacial region occupied by the glycerol backbone. In addition, several sites in the first helix and in the first and third interhelical loops penetrated the bilayer to depths of 8 – 10 Å (Figure 5), similar to the depth of a nitroxide attached at the fifth carbon of the lipid alkyl chain (5PCSL). Most notable were the changes observed in the localization of the third interhelical loop, which is highly accessible to the aqueous phase even in the Lipo state but becomes buried in the membrane in the Holo state (31). This strongly implicates the third interhelical loop as an important mediator of ExoU membrane association in the presence of ubiquitin.

Figure 5.

Membrane localization of ExoU. (Left) EPR depth parameter as a function of labeling site in the Apo (circles) and Holo (triangles) states. Increasing Φ values correspond to increasing depth in the membrane bilayer, with values around −2 corresponding to full exposure to the aqueous phase. (Right) Depth of spin labeled sites in the Holo state based on calibration with phosphatidylcholine spin labels (PCSL). The depths of the phosphate head group and of a nitroxide attached at the fifth carbon on the lipid alkyl chain (5PCSL) are shown for comparison. For details see references (31, 36, 41).

Double electron-electron resonance (DEER) studies of the four-helix bundle fold

Pulsed double electron-electron resonance (referred to as PELDOR or DEER) has had a remarkable impact on SDSL studies of protein structure over the past ten years. This EPR method (reviewed in (52)) involves the introduction of two spin labels into the system of interest and produces a measurement of the distance, or distribution of distances, between the two labels. Samples are flash-frozen and the experiment is carried out at cryogenic temperatures (typically 50K - 80K), currently a requirement to lengthen the nitroxide transverse relaxation time, providing a snapshot of the conformational states of the protein or complex. Magnetic dipole - dipole interactions between the spins induce oscillations in the recovery curve that are distance dependent, and deconvolution of the dipolar evolution curve yields a display of the distance distribution probability (52, 53) (see Figures 6 and 7).

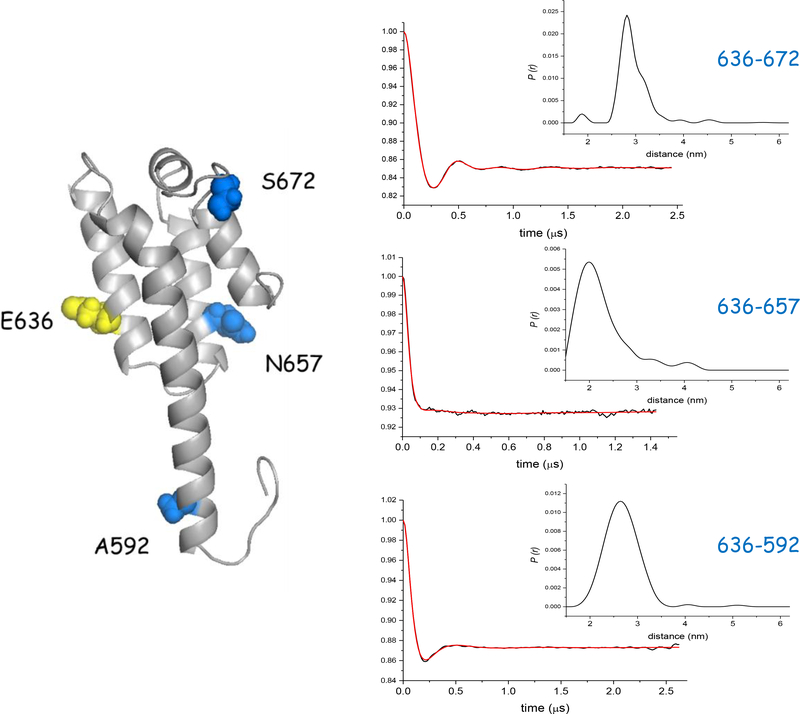

Figure 6.

DEER distance measurements in the Apo state. (Left) Cartoon representation of the four-helix MBD showing labeling sites. (Right) Dipolar evolution curves showing the background corrected dipolar evolutions (black) and fits (red) along with corresponding distance distributions (inset) for the 636–672 (top), 636–657 (middle), and 636–592 (bottom) spin label pairs.

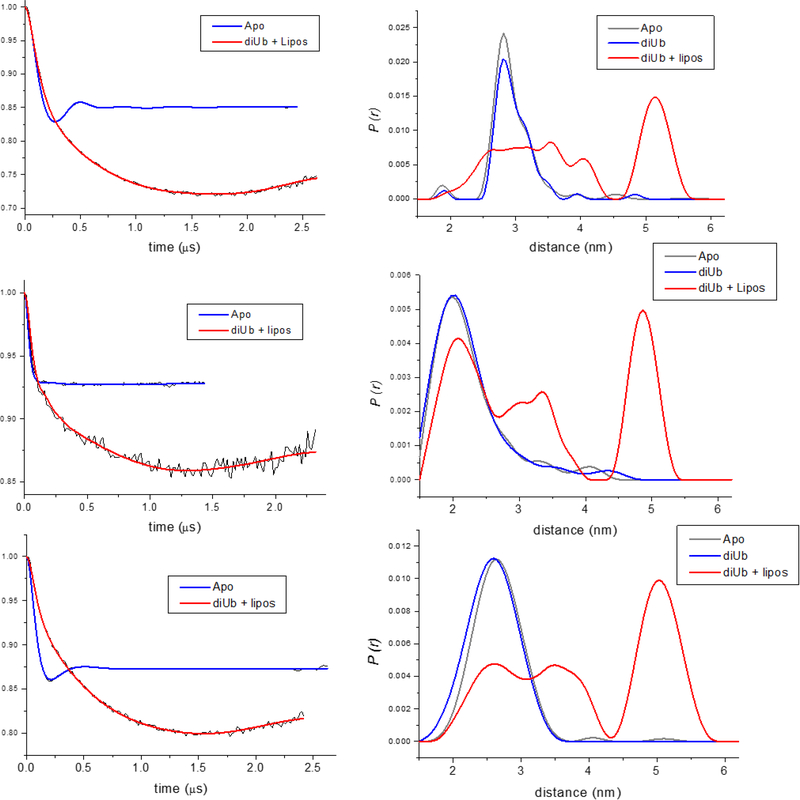

Figure 7.

Effect of membrane binding on DEER distance measurements. (Left) Dipolar evolution data (black) and superimposed fits for the Apo (blue) and Holo (red) states for (top to bottom) 636–672, 636–657, and 636–592 spin label pairs. (Right) Corresponding distance distributions for Apo (blue), ubiquitin-bound (gray), and Holo (red) states.

We carried out DEER studies on a series of spin labeled ExoU variants with pairs of labels in the MBD. A representative set of spin-label pairs is shown in Figure 6, with one site held constant (636R1, located in helix 2) and paired with sites in each of the other three helices. In the Apo state or when bound to ubiquitin, each of the pairs gave well-defined distance distributions that were in good agreement with expectations based on the ExoU-SpcU crystal structure (Figure 6). This again suggests that the crystal structures are accurate depictions of the MBD in the Apo state.

Results from DEER studies in the Holo state were quite different (Figure 7). In each case the dipolar evolution curve was dominated by a long exponential decay superimposed on any residual oscillations (Figure 7). Deconvolution of these decays by DeerAnalysis (54) gives distance distributions indicating a long (~ 50 Å) distance along with a broad distribution of shorter distances. This may indicate that the four-helix bundle is indeed separating, as suggested by the accessibility studies described above, with a mixture of fully and partially separated helices giving rise to the complex distance distributions. However, it is also possible that these results reflect aggregation of ExoU on the membrane surface that result in intermolecular dipolar interactions at distances of 50 Å or greater. To more fully understand these effects we are currently examining sample in which spin labeled ExoU is diluted with unlabeled (wt) protein to reduce intermolecular spin-spin interactions. Alternatively, deuteration of the protein can be used to significantly extend spin-spin relaxation times (55, 56) allowing very long distances to be detected. In addition, we have begun to investigate the use of nanodisc (ND) bilayers as membrane targets for ExoU (57). Nanodisc size can be controlled to limit the available surface area for protein-protein interaction, and a number of studies have now demonstrated the utility of ND as models for EPR studies of membrane properties (58) and in DEER studies of membrane proteins (59, 60).

Conclusions

Our studies using SDSL EPR have shown that the C-terminal membrane binding domain of ExoU undergoes significant conformational changes throughout the entire four-helix bundle upon interaction with membranes in the presence of a ubiquitin cofactor (i.e. in the enzymatically-active Holo state). This is noteworthy in that the C-terminal MBD is structurally and spatially distinct from the catalytic domain (Figure 1) where phospholipid hydrolysis is carried out. It should be noted that other phospholipases and membrane-surface active proteins also contain membrane binding domains that are distinct from their catalytic sites (61–63); for example the C2 domains of human cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) and protein kinase A (PKA), pleckstrin-homology domains, and ankyrin-repeat domains of group VIA phospholipases are all distinct from the catalytic domains of their respective enzymes. Indeed, membrane penetration by interhelical loops 1 and 3 of the ExoU MBD is remarkably similar to that observed for loops in the C2 domains of cPLA2 (41) and PKA (42). In each case the role of the membrane-binding domain appears to be to orient and localize the catalytic site in an appropriate position to carry out its catalytic function, and to enhance the affinity of the protein for the lipid bilayer.

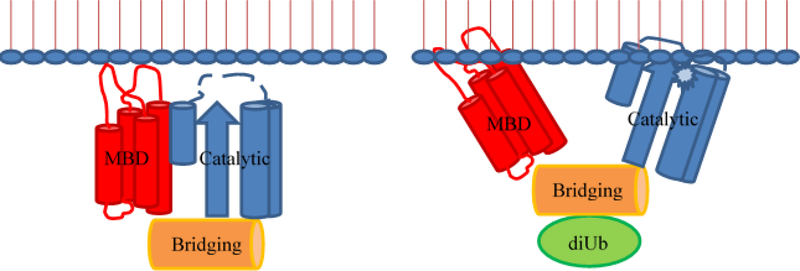

In addition to membrane penetration by the first and third interhelical loops, a majority of sites throughout the four helices in the C-terminal MBD (as defined by the ExoU-SpcU crystal structures, Figure 1) appear to associate with the membrane surface. This has led us to propose a model in which the helical bundle unfolds, with each individual amphipathic helix associating with the lipid bilayer (31). In an alternative model the four-helix bundle is displaced from the catalytic domain producing an allosteric conformational change in the catalytic domain and exposing the active site (Figure 8). Discrimination between these models awaits further studies using spin-diluted samples and/or nanodisc bilayers to eliminate possible complications due to protein aggregation on the membrane surface. Additional studies currently in progress will address the manner in which ubiquitin binding and membrane associate alter the structure of the catalytic domain.

Figure 8.

Model of synergistic activation of ExoU. Binding of diUb (green) or other ubiquitin isoform to the ExoU bridging domain (orange) and membrane association mediated by interhelical loops 1 and 3 in the membrane binding domain (MBD, red) produce a conformational change in the catalytic domain (blue) exposing the active site (star) to its phospholipid substrate.

Acknowledgements:

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM114234 (J.B.F) and AI104922 (D.W.F.). DEER instrumentation was supported by NIH grants S10RR022422 and S10OD011937.

Literature cited

- 1.Wisplinghoff H, et al. (2004) Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis 39(3):309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moradall MF, Ghods S, and Rehm BHA (2017) Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lifestyle: A Paradigm for Adaptation, Survival, and Persistence. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 7:1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galan JE & Collmer A (1999) Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science 284(5418):1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galan JE, Lara-Tejero M, Marlovits TC, & Wagner S (2014) Bacterial type III secretion systems: specialized nanomachines for protein delivery into target cells. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:415–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finck-Barbancon V, et al. (1997) ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol. Microbiol 25(3):547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy-Burman A, et al. (2001) Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J. Infect. Dis 183(12):1767–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser AR, et al. (2002) Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care Med 30(3):521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan E, et al. (2014) Risk of developing pneumonia is enhanced by the combined traits of fluoroquinolone resistance and type III secretion virulence in respiratory isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care Med 42(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klug CS & Feix JB (2008) Methods and applications of site-directed spin labeling EPR spectroscopy. Methods Cell Biol 84:617–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mchaourab HS, Steed PR, & Kazmier K (2011) Toward the fourth dimension of membrane protein structure: insight into dynamics from spin-labeling EPR spectroscopy. Structure 19(11):1549–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubbell WL, Lopez CJ, Altenbach C, & Yang Z (2013) Technological advances in site-directed spin labeling of proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 23(5):725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanucci GE & Cafiso DS (2006) Recent advances and applications of site-directed spin labeling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 16(5):644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mchaourab HS & Perozo E (2000) Determination of Protein Folds and Conformational Dynamics Using Spin Labeling EPR Spectroscopy Biological Magnetic Resonance, Volume 19, Distance Measurements in Biological Systems by EPR, eds Berliner LJ, Eaton SS, & Eaton GR (Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York: ), Vol 19, pp 185–247. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altenbach C, Lopez CJ, Hideg K, & Hubbell WL (2015) Exploring Structure, Dynamics, and Topology of Nitroxide Spin-Labeled Proteins Using Continuous-Wave Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol 564:59–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claxton DP, Kazmier K, Mishra S, & McHaourab HS (2015) Navigating Membrane Protein Structure, Dynamics, and Energy Landscapes Using Spin Labeling and EPR Spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol 564:349–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahu ID, McCarrick RM, & Lorigan GA (2013) Use of electron paramagnetic resonance to solve biochemical problems. Biochemistry 52(35):5967–5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato H, et al. (2003) The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J 22(12):2959–2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stirling FR, Cuzick A, Kelly SM, Oxley D, & Evans TJ (2006) Eukaryotic localization, activation and ubiquitinylation of a bacterial type III secreted toxin. Cell Microbiol 8(8):1294–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips RM, Six DA, Dennis EA, & Ghosh P (2003) In vivo phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU and protection of mammalian cells with phospholipase A2 inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem 278(42):41326–41332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson DM, et al. (2011) Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-modified proteins activate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa T3SS cytotoxin, ExoU. Mol. Microbiol 82(6):1454–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gendrin C, et al. (2012) Structural basis of cytotoxicity mediated by the type III secretion toxin ExoU from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS. Pathog 8(4):e1002637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halavaty AS, et al. (2012) Structure of the type III secretion effector protein ExoU in complex with its chaperone SpcU. PLoS. One 7(11):e49388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tessmer MH, et al. (2018) Identification of a ubiquitin-binding interface using Rosetta and DEER. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115(3):525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benson MA, et al. (2011) Induced Conformational Changes in the Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III Toxin, ExoU. Biophys. J 100(5):1335–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geissler B, Tungekar R, & Satchell KJ (2010) Identification of a conserved membrane localization domain within numerous large bacterial protein toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107(12):5581–5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geissler B, Ahrens S, & Satchell KJ (2012) Plasma membrane association of three classes of bacterial toxins is mediated by a basic-hydrophobic motif. Cell Microbiol 14(2):286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabin SD & Hauser AR (2005) Functional regions of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU. Infect. Immun 73(1):573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabin SD, Veesenmeyer JL, Bieging KT, & Hauser AR (2006) A C-terminal domain targets the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU to the plasma membrane of host cells. Infect. Immun 74(5):2552–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veesenmeyer JL, et al. (2010) Role of the membrane localization domain of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa effector protein ExoU in cytotoxicity. Infect. Immun 78(8):3346–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmalzer KM, Benson MA, & Frank DW (2010) Activation of ExoU phospholipase activity requires specific C-terminal regions. J. Bacteriol 192(7):1801–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessmer MH, Anderson DM, Buchaklian A, Frank DW, & Feix JB (2017) Cooperative Substrate-Cofactor Interactions and Membrane Localization of the Bacterial Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) Enzyme, ExoU. J Biol Chem 292(8):3411–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berliner LJ, Grunwald J, Hankovszky HO, & Hideg K (1982) A novel reversible thiol-specific spin label: papain active site labeling and inhibition. Anal Biochem 119(2):450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mchaourab HS, Kalai T, Hideg K, & Hubbell WL (1999) Motion of spin-labeled side chains in T4 lysozyme: effect of side chain structure. Biochemistry 38(10):2947–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Columbus L, Kalai T, Jeko J, Hideg K, & Hubbell WL (2001) Molecular motion of spin labeled side chains in alpha-helices: analysis by variation of side chain structure. Biochemistry 40(13):3828–3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Columbus L & Hubbell WL (2004) Mapping backbone dynamics in solution with site-directed spin labeling: GCN4–58 bZip free and bound to DNA. Biochemistry 43(23):7273–7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altenbach C, Greenhalgh DA, Khorana HG, & Hubbell WL (1994) A collision gradient method to determine the immersion depth of nitroxides in lipid bilayers: application to spin-labeled mutants of bacteriorhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91(5):1667–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altenbach C, Froncisz W, Hemker R, McHaourab H, & Hubbell WL (2005) Accessibility of nitroxide side chains: absolute Heisenberg exchange rates from power saturation EPR. Biophys. J 89(3):2103–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pyka J, Ilnicki J, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL, & Froncisz W (2005) Accessibility and dynamics of nitroxide side chains in T4 lysozyme measured by saturation recovery EPR. Biophys. J 89(3):2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhargava K & Feix JB (2004) Membrane binding, structure, and localization of cecropin-mellitin hybrid peptides: a site-directed spin-labeling study. Biophys. J 86(1 Pt 1):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pistolesi S, Pogni R, & Feix JB (2007) Membrane insertion and bilayer perturbation by antimicrobial peptide CM15. Biophys. J 93(5):1651–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frazier AA, et al. (2002) Membrane orientation and position of the C2 domain from cPLA2 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry 41(20):6282–6292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landgraf KE, Malmberg NJ, & Falke JJ (2008) Effect of PIP2 binding on the membrane docking geometry of PKC alpha C2 domain: an EPR site-directed spin-labeling and relaxation study. Biochemistry 47(32):8301–8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frazier AA, Roller CR, Havelka JJ, Hinderliter A, & Cafiso DS (2003) Membrane-bound orientation and position of the synaptotagmin I C2A domain by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry 42(1):96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altenbach C, Froncisz W, Hyde JS, & Hubbell WL (1989) Conformation of spin-labeled melittin at membrane surfaces investigated by pulse saturation recovery and continuous wave power saturation electron paramagnetic resonance. Biophys. J 56(6):1183–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altenbach C, Kusnetzow AK, Ernst OP, Hofmann KP, & Hubbell WL (2008) High-resolution distance mapping in rhodopsin reveals the pattern of helix movement due to activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105(21):7439–7444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuello LG, Cortes DM, & Perozo E (2004) Molecular architecture of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid bilayer. Science 306(5695):491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bavi N, et al. (2017) Structural Dynamics of the MscL C-terminal Domain. Sci Rep 7(1):17229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klug CS, Su W, & Feix JB (1997) Mapping of the residues involved in a proposed beta-strand located in the ferric enterobactin receptor FepA using site-directed spin-labeling. Biochemistry 36(42):13027–13033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato H, Feix JB, Hillard CJ, & Frank DW (2005) Characterization of phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III cytotoxin, ExoU. J. Bacteriol 187(3):1192–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyson GH & Hauser AR (2013) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate is a novel coactivator of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU. Infect. Immun 81(8):2873–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato H & Frank DW (2014) Intoxication of host cells by the T3SS phospholipase ExoU: PI(4,5)P2-associated, cytoskeletal collapse and late phase membrane blebbing. PLoS One 9(7):e103127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeschke G (2012) DEER distance measurements on proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 63:419–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pannier M, Veit S, Godt A, Jeschke G, & Spiess HW (2000) Dead-time free measurement of dipole-dipole interactions between electron spins. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 142(2):331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeschke G, et al. (2006) DeerAnalysis2006 - A comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR data. in Appl. Magn Reson, pp 473–498. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ward R, et al. (2010) EPR distance measurements in deuterated proteins. J Magn Reson 207(1):164–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt T, Walti MA, Baber JL, Hustedt EJ, & Clore GM (2016) Long Distance Measurements up to 160 A in the GroEL Tetradecamer Using Q-Band DEER EPR Spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 55(51):15905–15909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Springer TI, Kohn S, Feix JB. (2018) Investigating structural properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU toxin upon interaction with liposome and nanodisc bilayers by EPR spectroscopy. Biophys J 114(3):614. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stepien P, Polit A, & Wisniewska-Becker A (2015) Comparative EPR studies on lipid bilayer properties in nanodiscs and liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1848(1 Pt A):60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zou P & Mchaourab HS (2010) Increased sensitivity and extended range of distance measurements in spin-labeled membrane proteins: Q-band double electron-electron resonance and nanoscale bilayers. Biophys. J 98(6):L18–L20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Eps N, et al. (2017) Conformational equilibria of light-activated rhodopsin in nanodiscs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(16):E3268–E3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cho W & Stahelin RV (2005) Membrane-protein interactions in cell signaling and membrane trafficking. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 34:119–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lemmon MA (2008) Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9(2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dennis EA, Cao J, Hsu YH, Magrioti V, & Kokotos G (2011) Phospholipase A2 enzymes: physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev 111(10):6130–6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]