Abstract

Endothelins were discovered more than thirty years ago as potent vasoactive compounds. Beyond their well-documented vasomodulatory properties, however, the contributions of the endothelin pathway have been demonstrated in several neuroinflammatory processes and the peptides have been reported as a clinically relevant biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases. Several published works suggest that endothelin-1 greatly contributes to the progression of neuroinflammatory processes, particularly during infections in the central nervous system (CNS), and is associated with a loss of endothelial integrity at the blood brain barrier level. Because of the paucity of clinical trials with endothelin-1 antagonists in several infectious and non-infectious neuroinflammatory diseases, it remains an open question whether the 21 amino acid peptide is a mediator rather than a biomarker of the progression of neurodegeneration. The present review focuses on the potential roles of endothelins in the pathology of neuroinflammatory processes, including infectious diseases of viral, bacterial or parasitic origin in which the synthesis of endothelins or its pharmacology have been investigated from the cell to the bedside in several cases, and non-infectious inflammatory processes such as neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimers Disease or central nervous system vasculitis.

Keywords: Endothelin-1 (ET-1), cytokines, central nervous system, blood-brain barrier (BBB), chymase, mast cells, endothelin subtype B receptor (ETB), endothelin subtype A receptor (ETA), cerebral blood flow (CBF)

INTRODUCTION

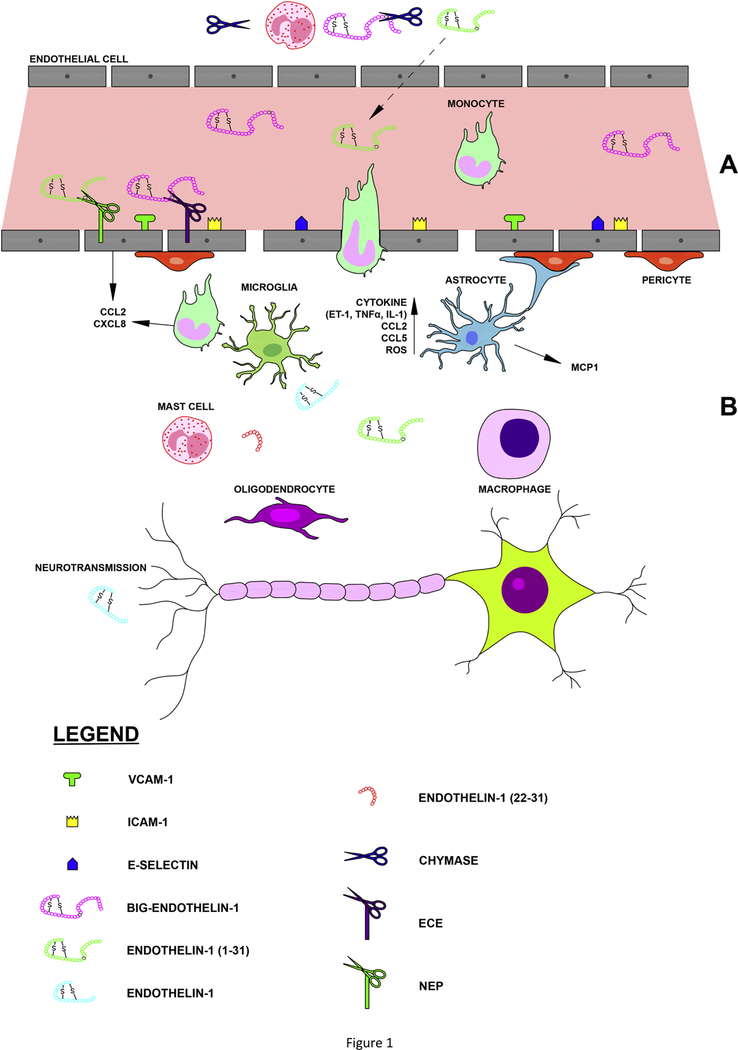

In the central nervous system (CNS), the response to adverse events such as infection and the development disorders is accompanied by an upregulation of the inflammatory response and alterations in the vasculature. In this regard, the endothelins have been demonstrated to mediate these responses (Figure 1). The endothelin (ET) family is comprised of three isoforms of 21-amino acid cyclic vasoactive peptides (ET-1, ET-2 and ET-3). A fourth isoform (ET-4) has been reported in the rat and mouse as the analogue to human ET-2 (Cunningham ME, et al., 1997; Khimji & Rockey, 2010; Motte, et al., 2006; Yanagisawa M, et al., 1988). ETs are synthesized from inactive precursor pro-polypeptides. The first product of the ET-1 gene is Pre-proendothelin, a peptide constituted of 212 amino acids. This peptide is processed by a carboxypeptidase to form proendothelin. Furin, an enzyme of the subtilisin family cleaves the proendothelin further to generate Big ET-1 (Blais, et al., 2002; D’Orleans-Juste, et al., 2003). The endothelin converting enzyme (ECE) then cleaves the bond between Trp 21 and Val 22 of Big ET-1 to generate ET-1 [Figure 1; (D’Orleans-Juste, et al., 2003; McMahon, et al., 1991)]. ECE is a zinc-dependent metalloendopeptidase localized in several cell types such as endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes and macrophages (Barnes & Turner, 1997, 1999; Hioki, et al., 1991; Hisaki, et al., 1993; Korth, et al., 1999; Takahashi M, et al., 1995).

Figure 1: ET-1 and cell-cell interactions in Central Nervous System diseases.

(A) In the sub-endothelial matrix (top of the figure), the biologically inactive precursor big-ET-1 (1–38) is cleaved by mast cell derived chymase, yielding ET-1 (1–31) which is subsequently released into the circulation where it is enzymatically-activated to ET-1 via the membrane bound neutral endopeptidase. As the major circulatory enzyme involved in the generation of ET-1, the endothelin converting enzyme (ECE) directly converts the 38-amino acid precursor to ET-1). Within the vessel lumen, the later peptide signals via two distinct G protein coupled receptors, namely ETA and/or ETB (not shown). In response to insults to the endothelium, ET-1 can induce remodeling of endothelial cells, with an increase in adhesion molecule production, and loss of BBB integrity. (B) After endothelial insults, ET-1 also increases the expression of chemokines such as CCL2 from endothelial cells and triggers the release of monocyte-derived CXCL8, resulting in margination of inflammatory cells and diapedesis across the BBB. Macrophages are well known to convert big-ET-1 to ET-1 and can secrete several cytokines such as interleukin-1 and TNFα, chemokines, including CCL2 and CCL5, reactive oxygen species, and ET-1 once differentiated within the CNS. ET-1 can also prompt astrocyte activation and proliferation and subsequent activation of microglial cells, resulting in reactive microgliosis. In neurons, ET-1 via its two receptors may act as a modulator of neuronal conductivity and/or neurotransmission.

The membrane bound-ECE family is comprised of the ECE-1, ECE-2 and ECE-3 isoforms with the former two moieties subdivided in functional isoforms (Emoto & Yanagisawa, 1995; Hasegawa, et al., 1998; Shimada, et al., 1994; Xu, et al., 1994). These sub-isoforms possess different N-terminal endings, are differently localized within the cell and preferably hydrolyze the ET-1 precursor Big-ET-1 (D’Orleans-Juste, et al., 2003).

The ECE-dependent pathway is not the sole pathway leading to the formation of ET-1. In embryos of mice whose ECE-1 and ECE-2 genes were knocked out, the production of ET-1 is only decreased by 33% (Yanagisawa H, et al., 2000). This suggests that other pathways involved in the production of ET-1 exist, independently of the canonical endothelin converting enzymes. One of those alternate pathways involves the contribution of mast cell-derived chymase. This serine protease matures Big ET-1 to ET-1. Chymase cleaves the 38-amino acid precursor Big ET-1 at the Tyr 31-Gly 32 bond leading to the formation of an intermediate 31-amino acid peptide, ET-1 (1–31). ET-1 (1–31) is further processed by the Neutral Endopeptidase, which hydrolyzes the Trp 21- Val 22 bond to form ET- in vitro (Hanson, et al., 1997; Nakano, et al., 1997) and in vivo (Fecteau, et al., 2005) (Figure 1).

The three human ET isoforms bind to two seven transmembrane G-protein-coupled cell surface receptors commonly known as ET receptor subtype A (ETA) and subtype B (ETB) (Arai, et al., 1990). ET-1 binds to ETA with the highest affinity compared to ET-2 and ET-3. On the other hand, all of the ET isoforms show equal binding affinity for ETB (Masaki, 2004; Rubanyi & Polokoff, 1994; Sakurai, et al., 1990). ET-1 is by far the most abundant and best described isoform (Struck, et al., 2005).

Some of the important functions of ET-1 include eliciting vasoconstriction and vasodilatation via release of nitric oxide (NO), ET clearance, salt balance and water homeostasis, inflammation, cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production (Bouallegue, et al., 2007; Khimji & Rockey, 2010; Kohan, et al., 2011; Speciale, et al., 1998; Wallace, et al., 1989). ET-1 is synthesized by a variety of cells, including endothelial cells, macrophages, cardiomyocytes, astrocytes, microglia and neuronal cells (D’Haeseleer, et al., 2013; Ehrenreich, et al., 1992; Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001; Kuwaki, et al., 1999; Miller, et al., 1996; Naidoo, Naidoo, Mahabeer, et al., 2004; Naidoo, Naidoo, & Raidoo, 2004; Yanagisawa M, et al., 1988). The plasma concentration of ET is usually low, approximately 0.2–5 pg/mL, with a short blood circulating half-life of 4–7 minutes (Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001).

ET-1: The vascular tone regulator

Although big ET-1, which has some vasoconstrictive properties, is found in the peripheral circulation, ET-1 has a 140-times higher vasoconstrictive potency (Rubanyi & Polokoff, 1994). ET-1 activation of ETA receptors mediates vasoconstriction through activation of phospholipase C, leading to the formation of inositol triphosphate (IP3), inducing the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum stores. Increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations result in contraction of the vascular smooth muscle cells (Bouallegue, et al., 2007; Khimji & Rockey, 2010; Wagner, et al., 1992). Conversely, the binding of ET-1 to ETB receptors mostly mediates vasodilation through activation of the PI3/Akt pathway, with ensuing activation of endothelial NO synthase, generating NO to cause relaxation of the vascular smooth muscle cells. Activation of ETB receptors present on vascular smooth muscle cells elicits vessel contraction (Khimji & Rockey, 2010; Tsukahara, et al., 1994). Therefore, ET-1 acts as a local modulator of vascular tone. As such, ET-1 plays significant roles in controlling vascular tone by acting directly or indirectly on vascular smooth muscle cells under normal homeostatic (non-disease) state. However, there are some suggestions that enhanced ET-1 secretion might be involved in the pathophysiology of many vascular diseases (Feldstein & Romero, 2007; Iglarz & Clozel, 2007; Marasciulo, et al., 2006).

ET-1: The inflammatory mediator

Initially regarded solely as a spasmogen, ET-1 is now also recognized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine (Sessa, et al., 1991; Teder & Noble, 2000). Production and secretion of ET-1 in endothelial cells are significantly higher during stress to the endothelium, and after exposure to inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001). ET-1 is also abundant in macrophages, leukocytes and fibroblasts (Gu, et al., 1991; Sessa, et al., 1991), indicating that ET-1 is closely associated with the inflammatory process. In this regard, several investigators have reported that ET-1 stimulates production of the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL-8) and (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) in monocytes and mesangial cells, which are known chemoattractants for neutrophils and monocytes (Helset, et al., 1994; Ishizawa, et al., 2004), suggesting that ET-1 contributes to leukocyte activation and trafficking. Moreover, ET-1 also acts as a mast cell activator, inducing degranulation and release of inflammatory cytokines from mast cells (Matsushima, et al., 2004). Interestingly, investigators have shown that ET-1 is also important in inducing traversal of inflammatory cells through endothelial cells into different tissues. shRNA knockdown of ET-1, the ETB receptor, and ECE-1 demonstrate that these components are independently involved in monocyte diapedesis (Reijerkerk, et al., 2012). In addition, ET-1 induces the upregulation of cellular adhesion molecules, such as Intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1), and e-selectin in human brain microvascular endothelial cells, facilitating margination, adherence, and infiltration of leukocytes across these cells into injured tissue (McCarron, et al., 1993). Furthermore, ET-1 causes platelet aggregation, and plays a role in the increased expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules and their synthesis of inflammatory mediators, thus contributing to vascular dysfunction (Matsuo, et al., 2001; Teder & Noble, 2000).

ET-1 is produced at significantly higher rates during a variety of infections (Dai, et al., 2012; Dietmann, et al., 2008; Koedel, et al., 1997; Machado, et al., 2006; Martins, et al., 2016; Petkova, et al., 2000; Petkova, et al., 2001; Wanecek, et al., 2000). In fact, ET-1 has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis and severity of bacterial, viral and parasitic disease processes including sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, rickettsial infections, Chagas disease and cerebral malaria (Dai, et al., 2012; Davi, et al., 1995; Freeman, et al., 2016; Goto, et al., 2012; Koedel, et al., 1997; Martins, et al., 2016; Petkova, et al., 2000; Petkova, et al., 2001; Samransamruajkit, et al., 2002; Schuetz, et al., 2008; Tschaikowsky, et al., 2000; Wanecek, et al., 2000; Wenisch, et al., 1996).

ET-1 in the Brain

In the brain, ET-1 is synthesized by vascular endothelial cells as well as by a variety of other cells including neurons and astrocytes (Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001; Schinelli, 2002). The components of this pathway are found throughout the brain suggesting a variety of potential functions. The receptors (ETA, ETB) as well as ET-1 and ET-3 are expressed by vascular, neuronal, and glial cells. ET immunoreactivity is present in neurons of the cerebral cortex, striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus, subfornical organ, median eminence, raphe nuclei, and pituitary gland (Giaid, et al., 1991; Lee, et al., 1990; Takahashi K, et al., 1991).

ET-1 is the predominant neural ET, but ET-3 predominates in the pituitary gland (Matsumoto, et al., 1989; Yoshizawa, et al., 1990). The ETA receptor is found on various neurons (Yamada & Kurokawa, 1998). ETB is localized to the neurons of the diagonal band of Broca, the fibers of the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, the fibers of the median eminence, and the thick fibers of hypothalamic neurons (Yamamoto & Uemura, 1998), which are also luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-rich . ECE-1 and ECE-2 are also found in the brain. Recent evidence suggests that the ETA receptor mediates signal transduction in the brain. Intraventricular injection of ET-1 in rats results in behavioral changes, including barrel rolling, body tilting, nystagmus, clonus, and tail extension. Most of these effects occur at doses that do not cause any changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) (Chew, et al., 1995). Injection of ET-1 into the periaqueductal gray matter reduces pain responses in mice subjected to the hot plate paradigm in a dose-dependent manner (D’Amico, et al., 1996). These data indicate that ET-1 has a role in neurotransmission that is important for an animal’s proprioception. In addition, ET-1 exacerbates apoptosis and neuronal cell death in ischemic models (Giuliani, et al., 2007; Leung, et al., 2004). In this regard, endothelin both enhances glutamate-induced neuronal toxicity and reduces clearance of glutamate by inducing a down regulation of glutamate transporters in astrocytes thereby, intensifying ischemic brain damage (Kobayashi, et al., 2005; Matsuura, et al., 2002).

ET-1 secreted under normal physiological conditions is beneficial in promoting cell proliferation. However, pathologically increased secretion of ET-1 from reactive astrocytes, microglia and neuronal cells in response to endothelial stress, triggered by irritants from drugs, cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species and infections, may be harmful and potentially detrimental to hosts (Kedzierski & Yanagisawa, 2001). It has been demonstrated in both animal models and human patients that elevated levels of ET-1 in blood or tissue subserve pathological roles of ET-1 (Dietmann, et al., 2008; McCarron, et al., 1993; Rolinski, et al., 1999). Furthermore, ET-1 exerts numerous effects on the immune system leading to neuroinflammation. For example, increased ET-1 production has been observed in various autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, and Kawasaki disease (Miyasaka, et al., 1992). Interestingly, plasma levels of ET-1 are increased in Multiple Sclerosis (D’Haeseleer, et al., 2013; Haufschild, et al., 2001); HIV (Chauhan, et al., 2007; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993; Hebert, et al., 2004); Herpesvirus (Bagnato, et al., 2001; Rosano, et al., 2003) and other diseases which affect the brain. We will herein attempt to summarize the contributions of ET-1 and components of the ET system in the pathogenesis of diseases of the central nervous system.

ROLE OF ET-1 IN CNS INFECTIONS

Bacterial toxins act on macrophages to synthesize pro-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines mediate the production of ET-1 from various sources, including brain microvascular endothelial cells (Figueras-Aloy, et al., 2003; Figueras-Aloy, et al., 2004; McCarron, et al., 1993; Piechota, et al., 2007; Tschaikowsky, et al., 2000; Weitzberg, et al., 1991). For instance, during bacterial meningitis, organisms traverse the blood-brain barrier (BBB) into the brain parenchyma by a number of mechanisms (Kim, 2010). Once in the brain, bacteria and bacterial factors activate glia which increase their production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, prompting activation of endothelial cells, an upregulation in cellular adhesion molecules and the margination of immune cells in the brain microvasculature (Saez-Llorens & McCracken, 2003). Infiltrating leukocytes secrete a variety of proteolytic products and toxins which damage the integrity of the endothelium. During these pathological processes, upregulated ET-1 causes further loss of endothelial integrity and increased BBB permeability, activates astrocytes, induces abnormal expression and production of cellular adhesion molecules including ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and e-selectin, enhanced production of chemoattractants by endothelial cells, besides acting as a neurotransmitter (Ehrenreich, et al., 1990; Hofman, et al., 1998; Koyama, et al., 2007; Koyama, et al., 2013; McCarron, et al., 1993; Miller, et al., 1996; Narushima, et al., 2003; Schwarting, et al., 1996; Wang, et al., 2013; Zidovetzki, et al., 1999). Adhesion molecules are then able to continue the cycle, inducing margination and binding of leukocytes to areas of injury.

Bacterial infections

Bacterial Meningitis

Despite appropriate antimicrobial strategies, adjunctive corticosteroids and supportive therapy, bacterial meningitis continues to be associated with high mortality and persistent residual neurological deficits, including stroke and paralysis (Grimwood, et al., 1995; Grimwood, et al., 2000; Kim, 2010; Merkelbach, et al., 2000; Sellner, et al., 2010). Meningitis is characterized by inflammation of meninges, usually by hematogenous spread following bloodstream infection or by direct extension of infectious organisms from contiguous foci (Chavez-Bueno & McCracken, 2005; Saez-Llorens & McCracken, 2003). An important role for ET-1 in the pathogenesis of bacterial meningitides has been described using animal models of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (Koedel, et al., 1998). Koedel and colleagues have demonstrated that after infection with S. pneumoniae, Wistar rats develop cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis as well as an increase in intracranial pressure, brain water content and CBF (Koedel, et al., 1998). Pre-treatment of the animals with a selective ETB receptor antagonist, BQ-788, abrogated these abnormalities (Koedel, et al., 1998), suggesting that ET-1 is important in the pathological presentation of bacterial meningitis. Leib et al. demonstrated that infant rats with S. pneumoniae meningitis exhibited extensive damage in the cortex and dentate gyrus (Leib, et al., 1996), likely induced by ET-1. When infected rats were treated with the non-selective (or dual) ETA/ETB receptor antagonist, bosentan, the cortical brain injury was mitigated and CBF was restored to levels comparable to that of uninfected controls (Pfister, et al., 2000).

Several groups have examined possible cellular mechanisms for the etiologic role of ET-1 in the pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis and the induction of host responses during the disease. ET-1 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are increased in both patients with bacterial meningitis and in experimental models of the disease as a result of increased production in several cell types that make up the neurovascular unit (Koedel, et al., 1997; Koedel, et al., 1998). Astrocytes have been suggested as a possible source of this increase in ET-1 secretion. Using an in vitro model of rat astrocytes infected with S. pneumoniae, investigators showed significant increases in astrocytic production of ET-1 (Koedel, et al., 1997). Treatment of cells with the ECE inhibitor phosphoramidon prevented the increase in ET-1 (Koedel, et al., 1997). Brain microvascular endothelial cells also contribute to the increase in ET-1 during bacterial meningitis, as S. pneumoniae infected brain endothelial cells exhibited an increase in both NO and ET-1 upon activation of ETB receptors (Koedel, et al., 1998). ET-1 is also likely to be critical in the trafficking of immune cells into the brain during bacterial meningitis. ET-1 and its components have been shown to induce monocyte diapedesis across the (Reijerkerk, et al., 2012). In this regard, ET-1 has been shown to induce the production of potent chemoattractants by endothelial cells, such as CCL2 and CXCL-8, which are significantly elevated in bacterial meningitis (Chen P, et al., 2001; Hofman, et al., 1998; Koyama, et al., 2007; Koyama, et al., 2013; Sprenger, et al., 1996; Zidovetzki, et al., 1999).

ET-1 plays a critical role in generating the host response during bacterial meningitis, causing cerebral vascular and CNS injuries. These abnormalities are likely mediated, in part, by increased ET-1 production in endothelial cells (Koedel, et al., 1997; Koedel, et al., 1998). There are still several gaps in our understanding of the precise processes involved in inducing leukocyte infiltration to the CNS, and these areas would benefit from further investigations.

Parasitic infections

ET-1 and malaria.

Malaria is a potentially life-threatening disease which affects approximately 216 million individuals and results in more than 400,000 deaths yearly (World Health Organization, 2017). Cerebral malaria (CM) is the most severe and potentially fatal neurological complication with Plasmodium infection (Hunt & Grau, 2003; Newton & Krishna, 1998), and children younger than 5 years-old are the most susceptible, accounting for > 70% of the malaria-related deaths (Birbeck, et al., 2010; Carter, et al., 2006; Idro, et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2014). Despite significant advances in the reduction of global transmission of malaria since 2000 (World Health Organization, 2017), CM continues to have a mortality rate of 20%, and, more than 25% of the survivors develop long-term neurological deficits (Birbeck, et al., 2010; Carter, et al., 2006; Idro, et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2014), creating enormous social and economic burdens in malaria-endemic regions (Onwujekwe, et al., 2000; World Health Organization, 2014).

Characterized by adherence of parasitized red blood cells to the brain microvasculature, vasospasms, and changes in levels of vasoregulatory molecules, hypoperfusion and ischemia, inflammation and impairment of the BBB (Adams S, et al., 2002; Cabrales, et al., 2010; Dai, et al., 2010; Desruisseaux, et al., 2008; Dorovini-Zis, et al., 2011; Grab, et al., 2011; Kennan, et al., 2005; Potchen, et al., 2010; Renia, et al., 2012), one could certainly deduce that ET-1 contributes to the pathogenesis of CM. Investigators have long demonstrated that plasma levels of ET-1 and big ET-1 are elevated in patients with P. falciparum infection in association with damage to the cerebral endothelium (Dietmann, et al., 2008; Wenisch, et al., 1996). The elevated levels of ET-1 and of components of the ET system, i.e. ECE, ETA and ETB have been tied to glial activation, a reduction in CBF and in damage to neuronal axons in animal models of experimental CM (Kennan, et al., 2005; Machado, et al., 2006).

Recent studies from the Desruisseaux laboratory, employing experimental models of CM demonstrate that ET-1 is critical in inducing the pathological sequelae of the disease (Dai, et al., 2012; Freeman, et al., 2016; Martins, et al., 2016). In mice infected with a non-neurotropic strain of Plasmodium berghei, which causes malaria in rodents, Martins et al. demonstrated that daily injections of ET-1 induced a CM-like phenotype in the mice, with decreased CBF, increased infiltration of inflammatory cells to cerebral vessels, leakage of the BBB, behavioral changes, and accelerated mortality (Martins, et al., 2016). Other investigators from our group have demonstrated that treatment of mice infected with a neurotropic strain of P. berghei, with a selective ETA receptor antagonist decreased the incidence of brain hemorrhages, improved survival, and prevented malaria-associated cognitive decline, with or without concomitant use of an anti-malarial artemisinin derivative (Dai, et al., 2012; Freeman, et al., 2016). The protective effects of the ETA receptor blocker were shown to result from mitigation of CM-associated cerebral vasculopathy. ETA antagonism prevented vasospasms, led to a decrease in leukocyte infiltration of the cerebral vasculature, likely as a result of decreased production of chemokines and cellular adhesion molecules, and resulted in decreased secretion of circulating inflammatory cytokines (Freeman, et al., 2016)

As with humans, experimental models of CM demonstrate persistent cognitive deficits and impairment of motor coordination, even after antimalarial treatment (Dai, et al., 2010; Desruisseaux, et al., 2008; Lackner, et al., 2006). Treatment with an ETA receptor antagonist prevented the long-term neurological sequelae in mice with experimental CM (Freeman, et al., 2016). Treatment also improved the survival of affected mice (Dai, et al., 2012; Freeman, et al., 2016).

Although the present data indicate that ET-1 is involved in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria, studies to determine the precise cells responsible for the increased levels of ET-1 and targets of ET-1 actions during CM are needed.

ET-1 and Chagas Disease

Chagas disease is a neglected tropical disease caused by the protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in endemic areas of Latin America and among immigrants to non-endemic areas (Bern & Montgomery, 2009; Roca, et al., 2011; Salvador, et al., 2013; Tanowitz, et al., 2011). The most important manifestations of Chagas disease are cardiomyopathy and the megasyndromes involving the gastrointestinal tract (Tanowitz, et al., 1992). Infection with T. cruzi results in an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, Toll-like receptors, components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, ET-1 and thromboxane A2 (Ashton, et al., 2007; Petkova, et al., 2001; Tanowitz, et al., 1990). Using selective deletion of the ET-1 gene in endothelial cells and in cardiomyocytes, Tanowitz et al. have shown that ET-1 is pivotal to the development of fibrosis and remodeling of the cardiomyocytes during infection (Tanowitz, et al., 2005).

CNS involvement in Chagas disease, however, while recognized since the discovery of T. cruzi more than a century ago (Carod-Artal & Gascon, 2010; Carod-Artal, 2013; Chagas, 1911, 1913; Pittella, 2009; Vianna, 1911), has been greatly understudied (Masocha & Kristensson, 2012); as the majority of research has been focused on the cardiomyopathic aspects. Nevertheless, Chagas disease is clearly associated with significant CNS disease. Intracellular T. cruzi in the amastigote stage have been reported in brain tissue in autopsy specimens; within CNS monocytic cells and glial cells (Chagas, 1911, 1913; De Queiroz, 1973; Mortara, et al., 1999; Pittella, 2009; Torres & Villaça, 1919; Vianna, 1911) as well as free organisms within inflammatory foci (De Queiroz, 1973). Intracellular replicating parasites within glial cells have been observed in animal models during acute disease, and parasites have also been observed within neurons (Ben Younes-Chennoufi, et al., 1988; Buckner, et al., 1999; Caradonna & Pereiraperrin, 2009).

In 1913, Carlos Chagas described an encephalopathy dubbed “forma nervosa” in over 200 individuals with Chagas disease (Chagas, 1913; Koberle, 1968). Since then, investigations increasingly point toward cerebral microvascular and CNS-derived etiologies in the pathogenesis of neuro-Chagas disease (Mangone, et al., 1994; Nisimura, et al., 2014; Pentreath, 1995). It has been reported that CNS microvasculature is disrupted in Chagas disease (Carod-Artal, et al., 2011; Nisimura, et al., 2014; Prado, et al., 2011; Tanowitz, et al., 1996); T. cruzi infection in mice results in a vasculitis associated with increased cerebral oxidative stress and an increase in leukocyte rolling/adhesion and arteriolar endothelial dysfunction (Nisimura, et al., 2014). The presence of small vessel disease, in several vascular beds in the CNS, is often an underlying etiology of stroke syndromes in Chagasic patients, suggesting an association with microcirculatory alterations (Carod-Artal, et al.; Prado, et al., 2011; Tanowitz, et al., 1996). Both acute and chronic CNS infection with T. cruzi are marked by lymphocyte infiltration (Britto-Costa, 1971; Pentreath, 1995; Silva AA, et al., 1999). Additionally, population studies and experimental models demonstrate brain atrophy and loss of neurons in several regions of the CNS during Chagas disease, including cortex, cerebellum and hypothalamus (Alencar A., 1964; Brandao & Zulian, 1966; Britto-Costa, 1971; Chuenkova & Pereiraperrin, 2011; Oliveira-Filho, et al., 2009). These pathological changes result in diverse manifestations of acute Chagasic CNS disease which include meningoencephalitis, which can be fatal if left untreated, (Alencar A & Elejalde, 1960; Bern, et al., 2011; Diazgranados, et al., 2009; Pittella, 2009; Py, 2011; Rassi, et al., 2012; Silva N, et al., 1999), and microcephaly and subependymal hemorrhage similar to TORCH syndromes (Bittencourt, 1976; Flores-Chavez, et al., 2008; Mendoza Ticona, et al., 2005).

ET-1 has been shown to contribute to the development of Chagasic cardiomyopathy (Tanowitz, et al., 2005). However, the modulations of ET-1 and its downstream effectors on virulence of the parasite with regard to entry into the CNS, inflammation, and glial and neuronal dysfunction have yet to be explored in CNS Chagas disease.

Viral infections

Past and recent studies in virus-mediated infections, have demonstrated that viral-induced inflammatory reactions of the CNS, triggers activation of neurons, astrocytes and microglia cells in the brain, resulting in the pathogenesis and processes of neurodegenerative diseases (Karim, et al., 2014; Zhou, et al., 2013). A wide range of viruses have been shown to be associated with different types of neurodegenerative diseases by inducing widespread neuronal dysfunctions and degenerations with devastating effects (Hou, et al., 2016; Koyuncu, et al., 2013; McGavern & Kang, 2011). Once in the host, viral infection of the CNS can induce activation of both innate and adaptive immune response (Rivest, 2009). Activated microglial, monocytic, neuronal and astrocytic cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines (endothelins, TNF-alpha, IL-1), chemokine (CCL2 and CCL5 and reactive oxygen species, which mediate the neuroinflammation-induced neurodegenerative diseases (Das Sarma, 2014; Perry VH & Teeling, 2013; Ransohoff & Perry, 2009; Ransohoff & Brown, 2012; Varvel, et al., 2016). Activation of microglia and neuroinflammation may also result in the break-down of the BBB and corresponding leakage of complement into the CNS, chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease (Orsini, et al., 2014; Strazza, et al., 2011; Xanthos & Sandkuhler, 2014).

HIV and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)

It has been demonstrated that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes neurodegeneration by disrupting the BBB, infiltrating the brain, infecting circulatory peripheral blood monocytic cells which then also migrate into the CNS (Miner & Diamond, 2016), resulting in a chronic neuroinflammatory disease and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) (Malik & Eugenin, 2016; Zayyad Spudich, 2015). HIV-1 and HAND continue to be a major concern in the infected population, despite the use of anti-retrovirals (Carroll & Brew, 2017; Heaton, et al., 2011; Tan & McArthur, 2012).

Abnormally elevated release of the vasoactive mediator ET-1 from activated monocytes, which persists despite anti-retroviral therapy, has been linked to HIV progression, mortality, and HIV-associated cardiovascular and neurocognitive disorders (Didier, et al., 2002; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993). Enhanced ET-1 secretion due to HIV infection induces endothelial damage and dysfunction and has been associated with cardiovascular and other HIV-associated comorbidities (Fitzpatrick, et al., 2016), including HAND (Didier, et al., 2002; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993). HAND is characterized by cognitive, motor, and behavioral abnormalities (Ances & Ellis, 2007; Antinori, Arendt, et al., 2007; Antinori, Trotta, et al., 2007; Gonzalez-Perez, et al., 2017; Kaul, et al., 2005; Letendre, 2011; McArthur, 2004; Sacktor, et al., 2001; Sacktor, 2002). Despite recent advances in antiretroviral therapy and in understanding of the pathogenesis of HIV, and its associated neuronal effects, the mechanisms by which HIV infection causes endothelial dysfunction and subsequent development of HAND remains poorly defined (Ances & Ellis, 2007). Early work by Lane and colleagues and by Fauci demonstrated that the HIV virus transmigrates into the CNS through infected monocytes which infiltrate the BBB (Fauci, 1996; Lane, et al., 1996). It has been demonstrated that once these HIV-infected monocytes/macrophages from the bloodstream have crossed the BBB into the CNS, the virus can then further infect microglia and brain monocytic/macrophagic cells (Boven, et al., 2000; Dallasta, et al., 1999; Trillo-Pazos, et al., 2003). The activated HIV-infected glial cells, including astrocytes, microglia and monocytes/macrophages secrete high levels of ET-1, and other neurotoxic inflammatory mediators, including cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6), platelet activating factor, and nitric oxide, all of which can cause neuronal injury (Chauhan, et al., 2007; Didier, et al., 2002; Didier, et al., 2003; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993; Kaul, et al., 2001; Swindells, et al., 1999). In addition, viral products, especially the HIV proteins gp120, Tat, Nef, and Rev have been shown to be both neurotoxic and cytotoxic to endothelial cells (Bennett, et al., 1995; Dreyer, et al., 1990; Huang MB, et al., 1999; Kanmogne, et al., 2001; Kaul, et al., 2001; Lannuzel, et al., 1995; Magnuson, et al., 1995; Patel, et al., 2000; Scutari, et al., 2017), and contribute to key processes in HAND through increased vasoconstriction, ET-1 secretion and neuroinflammation (Ramesh, et al., 2013; Rolinski, et al., 1999). The HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 stimulates macrophages and pulmonary arterial endothelial cells to secrete ET-1 (Didier, et al., 2002; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993; Kanmogne, et al., 2005), which is critical in monocyte diapedesis across the BBB (Hong & Banks, 2015; Scutari, et al., 2017). Cerebral macrophages in patients with HIV encephalopathy strongly express ET-1 (Avalos, et al., 2017; Cotter, et al., 2002; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993). Elevated ET-1 secretion has been linked to neuroinflammation and neuronal damage during HIV (Chauhan, et al., 2007; Rolinski, et al., 1999), but there has been no assessment of the role of ET-1 in the development of HAND.

Increased levels of ET-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV encephalopathy has been observed in association with neuronal injury, neuroinflammation, increased BBB leakage and edema, and neurological deficits (Rolinski, et al., 1999; Scutari, et al., 2017; Zhang X, et al., 2013). In addition, in vitro studies demonstrate that ET-1 is secreted in a human BBB model of astrocytes and brain microvascular endothelial cells exposed to HIV (Didier, et al., 2002). Furthermore, ET-1 has been shown to act as a chemoattractant for monocytes in the brain via associated increases in the secretion of MCP-1 and IL-8 (Helset, et al., 1994; Ishizawa, et al., 2004), properties which suggest a potential role for ET-1 in the development of HAND. In this regard, ET-1 likely contributes to the increased activation of macrophages and microglia in the CNS which have been shown to play a role in the development of HAND (Chauhan, et al., 2007; Ishikawa, et al., 1997; Lake, et al., 2017; Ma, et al., 1994; Perry VH & Teeling, 2013; Werner & Engelhard, 2007).

Herpes viruses

Herpes viruses are neurotropic pathogens that infect mostly humans (Deigendesch & Stenzel, 2017; Munawwar & Singh, 2016; Swanson & McGavern, 2015). Currently, there are nine (9) herpesvirus types known to infect humans: herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus (HHV) 6A and 6B (HHV-6A and HHV-6B), HHV-7, and Kaposi’s_sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or HHV-8 (Alba, et al., 2011; Cunningham C, et al., 2010; Davison, 2010; Meyding-Lamade & Strank, 2012; Norberg, 2010), all of which can migrate the immune system and induce the activation of innate and adaptive immune responses by triggering higher secretion and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Scheglovitova, et al., 2002).

KSHV, or HHV-8, is the causative agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), a tumor of lymphatic endothelial origin characterized by proliferating spindle cells containing elements of endothelial and inflammatory cells (Curtiss, et al., 2016; Gramolelli & Ojala, 2017; Kahn, et al., 2002; Naldi, et al., 2018; Weninger, et al., 1999).

Although rare, particularly after the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy, KS can disseminate to the CNS in immunosuppressed patients (Bahat, et al., 2002; Gorin, et al., 1985; Jellinger, et al., 2000; Levy, et al., 1984; Mossakowski & Zelman, 1997; Myers, et al., 1974; Pantanowitz & Dezube, 2008; Post, et al., 1986). CNS lesions, when present, typically occur in individuals with concurrent visceral involvement (Gorin, et al., 1985). Lesions are highly vascularized, often display central necrosis, and can be associated with contemporaneous infection with other opportunistic organisms (Bahat, et al., 2002; Barton, et al., 1983; Myers, et al., 1974; Rwomushana, et al., 1975; Vilaseca, et al., 1982; Welch, et al., 1984). KS-associated tumors can involve the cerebrum, cerebellum and dura matter (Ariza & Kim, 1988; Barton, et al., 1983; Buttner, et al., 1997; Myers, et al., 1974; Rwomushana, et al., 1975; Vilaseca, et al., 1982; Welch, et al., 1984), resulting in subdural hematoma, paresis, tonic clonic seizures, among neurological deficits (Ariza & Kim, 1988; Bahat, et al., 2002; Gorin, et al., 1985).

KSHV has long been shown to increase the secretion of angiogenic factors and inflammatory factors and to induce the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Dimaio & Lagunoff, 2012; Kang T, et al., 2008; Purushothaman, et al., 2016). However, the role of ET-1 in the pathogenesis of KSHV infection is still unclear. While some investigators demonstrate no increase in ET-1 during KS (Cacoub, et al., 1995), others have demonstrated an increase in big ET-1, the ET-1 precursor, during infection with KSHV (Speciale, et al., 2006). Bagnato and colleagues have demonstrated that ET-1 and its receptors are critical to angiogenesis and proliferation of KS tumors (Bagnato, et al., 2001; Bagnato, et al., 2011; Rosano, et al., 2003), with dual ETA/ETB receptor blockage abrogating ET-1-induced KS cell invasion and tumor growth and migration both in vitro and in an in vivo model of local cutaneous invasion (Bagnato, et al., 2001; Rosano, et al., 2003). While these data suggest that ET-1 is involved in the virulence and dissemination of KSHV-induced tumors, the effects of ET-1 on distant disease, including CNS disease, remains to be investigated.

Studies on the involvement of ET-1 in the pathogenesis of other herpes viruses are limited. There is evidence that CMV infection causes an increase in ETB receptor expression (Yaiw, et al., 2015), suggesting a potential role for ET-1 and its receptors in the pathogenesis of the virus. Scheglovitova and colleagues demonstrated that the effects of HSV-1 on endothelial production of ET-1 is pleiotropic and is dependent on the baseline spontaneous production of ET-1 from those cells and on interferon activation (Scheglovitova, et al., 2013). However, although herpesviruses are associated with CNS pathology, including increased secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators from circulatory immune cells which can traverse the BBB (Conrady, et al., 2010; DeBiasi, et al., 2002; Deigendesch & Stenzel, 2017; Harris & Harris, 2015; Koyuncu, et al., 2013; Marques, et al., 2006; Martino, et al., 2000), there is a paucity of investigations on a role for ET-1 in this process.

Flaviviruses

The Flaviviridae family consists of positive, single-stranded enveloped RNA viruses which can occasionally cause severe disease and mortality in humans and animals (Fernandez-Garcia, et al., 2009; Kimura T, et al., 2010). These vector-transmitted viruses include - Yellow Fever, Dengue virus (DENV), Japanese encephalitis virus, Chikungunya virus, West Nile virus and Zika virus (Brehin, et al., 2008; Chen LH & Wilson, 2016; Das, et al., 2010; Fernandez-Garcia, et al., 2009; Huang YJ, et al., 2014; Jhan, et al., 2017; Kimura T, et al., 2010; Lannes, et al., 2017; Lindenbach & Rice, 2003; Lum, et al., 2017). Disease from flaviviruses can range from asymptomatic to symptomatic manifestations, with high fever, chills, headache, back and muscle aches, dizziness, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting (Gould & Solomon, 2008; Murphy BR & Whitehead, 2011), and can sometimes result in fatal illness, such as encephalitis and hemorrhagic fever (Basu, et al., 2016; Imaizumi, et al., 2005). In addition, flavivirus infections can cause inflammation of the CNS (Furr & Marriott, 2012; Roach & Alcendor, 2017; Tsai, et al., 2016).

DENV infection results in important clinical symptoms which include fever, headache and rash (Guabiraba & Ryffel, 2014) (Singhi, et al., 2007; Thomas EA, et al., 2010). However, acute infection may result in severe disease such as in dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome (Guabiraba & Ryffel, 2014; Halstead, 2002). DENV has been shown to affect several vital organs, including the liver, heart, kidneys, and the brain (Basu & Chaturvedi, 2008). DENV invades the CNS by migrating through CNS through BBB disruption, inducing encephalitis (Li GH, et al., 2017; Li H, et al., 2017; Verma, et al., 2014). These syndromes prominently feature vascular leakage (Tsai, et al., 2016; van de Weg, et al., 2014). Interestingly, van de Weg and colleagues recently demonstrated that endothelial damage in patients infected with DENV was associated with significantly increased plasma levels of ET-1 (van de Weg, et al., 2014). Plasma leakage during DENV infection can lead to hypovolemic shock, coagulopathy, bleeding, organ impairment and death (Simmons, et al., 2012). Furthermore, DENV infection of endothelial cells may induce injury to the brain microvasculature, resulting in increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the cerebral microvascular milieu (Basu & Chaturvedi, 2008; Cardier, et al., 2006; Hendarto & Hadinegoro, 1992; Solomon, et al., 2000; van de Weg, et al., 2014).

While it is well established that flaviviruses enter into the CNS, to infect glial cells, and elicit a robust immune response, a relationship between such events and ET-1 has not been established.

Several viral infections of the CNS are associated with an increase in the secretion of ET-1 by activated endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, and glial cells, particularly astrocytes and microglia (Chauhan, et al., 2007; Didier, et al., 2002; Didier, et al., 2003; Ehrenreich, et al., 1993; Ma, et al., 1994; Zhang WW, et al., 1994). As of the time of this review, causative relationships between the pathological increase in ET-1 secretion and vascular dysfunction with resultant loss of BBB integrity or the robust immune response that occur during infection remains to be assessed. However, previous studies of parasitic diseases of the brain suggest that ET-1 likely plays an integral role in the pathogenesis of these infections in the CNS (Dai, et al., 2012; Freeman, et al., 2014; Freeman, et al., 2016; Martins, et al., 2016). Thus, further investigations are warranted to determine the role of ET-1 in the pathogenesis of neurological dysfunction during viral illnesses.

ENDOTHELIN-1 AND CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM VASCULITIS.

Potential roles of the Endothelin-1 pathway in Central Nervous System Vasculitis

ET-1 secreted predominantly by the endothelial cells (Yanagisawa M, et al., 1988) is found in high intramural concentrations in several inflammatory diseases of the vascular wall (Battistini, et al., 1993). Of relevance to the present section, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has been associated with high levels of plasma levels of ET-1 in patients (Dhaun, et al., 2009; Julkunen, et al., 1991). Furthermore, cultured endothelial cells exhibited increased secretion of ET-1 after exposure to sera from patients with SLE (Yoshio, et al., 1995). Nakamura and colleagues previously demonstrated that selective ETA antagonism prevented the progression of lupus nephritis in a murine model (Nakamura, et al., 1995), and more recently, Li Guo and colleagues showed that SLE patients with autoantibodies to ETA were more likely to develop pulmonary hypertension (Guo L, et al., 2015). Although there has not been any clear associations between ET-1 and neuropsychiatric SLE, high concentrations of vascular ET-1 have been observed in vasculitis-prone MRL/lpr mice (Sugimoto, et al., 2017), an established model of SLE (Perry D, et al., 2011), which has been well characterized as a model of spontaneous neuropsychiatric lupus (Gao, et al., 2009; Gulinello & Putterman, 2011; Gulinello, et al., 2012; Stock, et al., 2015; Wen, et al., 2013), with clear leukocyte infiltration to the choroid plexuses and breach of the blood-brain barrier (Mike, et al., 2018).

In Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis, mice that overexpress endothelial and astrocytic ET-1 present more severe inflammation and demyelination (Guo Y, et al., 2014). These outcomes are possibly the result of ET-1- induced alteration of the integrity of myelin sheets in the spinal cord via a Notch-1-dependent mechanism as well as suppression of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell-dependent repair of demyelinated neurons by the peptide (Hammond, et al., 2015). Correspondingly, investigators have demonstrated that repression of one of the mouse chymases, mouse Mast Cell Protease 4 (mMCP-4), mitigates disease-related increases in brain ET-1 levels during EAE (Desbiens, et al., 2016).

Thus, repressing the brain production of ET-1 with a chymase inhibitor may facilitate myelin repair in neurogenerative diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Interestingly, more than 30 years ago, inflammatory vasculitis had been reported especially in lesioned sections of the spinal cord of MS patients more than 30 years ago (Adams CW, et al., 1985). The role of chymase-dependent production of ET-1 in the development of vasculitis in MS patients, however, remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, in light of the importance of mast cell-derived chymase in ET-1 generation (see Introduction), we suggest that targeting chymase rather than the ECE to treat CSNV may be preferable. Indeed, homozygous repression of mMCP-4 does not prompt the impairment of embryonic development in genetically engineered mice (Tchougounova, et al., 2003). Furthermore, pharmacological interference with an ECE inhibitor enhances amyloid plaque formation (Eckman, et al., 2001; Pacheco-Quinto, et al., 2013; Wang S, et al., 2010).

ET-1 and ET receptors in Giant Cell Arteritis

Tissular levels of ET-1 and of its ETB receptors are significantly increased in arteries derived from inflammation prone-patients with giant cells arteritis (GCA). In a recent study, Regent and colleagues (2017) reported that the dual ETA/ETB antagonist macitentan combined with glucocorticoids, reduced vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation in vessels of patients with GCA (Regent, et al., 2017). Planas-Rigol and colleagues demonstrated that ET-1 immunoreactivity was predominant in leucocytes infiltrating the medial-intima interphases of vessels derived from GCA patients and that both ETA and ETB receptors in VSMC proliferation in such vessels through activation of Focal Adhesion Kinase (Planas-Rigol, et al., 2017).

Mast cells and Central Nervous System Vasculitis

The role of mast cells in the etiology of CNS vasculitis (CNSV) remains controversial. While some groups have suggested protective roles of those cells in large vessel vasculitis via histamine-dependent repression of pro-inflammatory IL- (Springer, et al., 2017), others have suggested that hyperactivated mastocytes contribute to inflammatory-dependent deterioration of blood vessels (Kiely, et al., 1997; Lipitsa, et al., 2015). Kiely and colleagues reported a role for mast cells in the genesis of mercuric chloride-induced vasculitis in Brown Norway rats (Kiely, et al., 1997). Furthermore, Lipïtsa et al. demonstrated that mastocyte-derived chymase is directly involved in intramural deposition of immunoreactants in the vascular wall (Lipitsa, et al., 2015). Pro-inflammatory mast cells are predominantly located on the abluminal side of blood vessels and can readily cross the BBB to gain direct contact with astrocytes, glial cells and other cellular moieties involved in the maintenance of the brain integrity, especially in diseases states (Silverman, et al., 2000).

Furthermore, cross-talk between mast-cells and Kallikrein-Kinin has been implicated in inflammatory propagation and enhanced cardiac parasitism and fibrosis in T. cruzi-infected mice (Nascimento, et al., 2017) yet it remains to be investigated if a similar cross talk comes into play within the BBB in CNSV.

The current state of knowledge on potential roles of ET-1 in inflammation-prone vasculitis of the CNS has been summarized. The mechanistic basis of this type of vascular dysfunction remains to be investigated, although its occurrence increases in several bacterial and viral-induced infections of the CNS. Targeting chymase rather than the overall mastocytic activity might represent a more effective approach to treating CNSV due to the neuroprotective roles mast cells reported in large vessel vasculitis.

ROLE OF ET-1 IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is one of the most common and devastating neurodegenerative diseases (Xie, et al., 2014), and is characterized by a substantial loss of neurons in the brain, which may lead to progressive memory decline and a deficits in cognitive functions (Ubhi & Masliah, 2013). These neuronal degenerative alterations in AD are induced by a number of factors which include beta-amyloid deposition, microtubule destabilization, deficiencies in neuronal communication and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Wang DB, et al., 2010). The development of neurodegenerative pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s disease, may be linked to environmental and genetic factors (Barber, 2012; El Gaamouch, et al., 2016; Grant, et al., 2002; Tanzi & Bertram, 2001; Tol, et al., 1999).

While the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD is multifactorial, the primary factors that initiate AD pathogenesis are soluble and aggregated neurotoxic beta-amyloid protein (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau which induce inflammatory activation of glial cells (Guerriero, et al., 2016; Schwartz & Deczkowska, 2016). Amyloid plaques, consisting of extracellular Aβ deposits from amyloid precursor protein (APP), and neurofibrillary tangles, composed of aggregates of misfolded and tau proteins, within neurons are typical characteristics of AD pathology (Lacosta, et al., 2017; Murphy MP & LeVine, 2010). Levels of Aβ in the brain are regulated by the relative rates of Aβ production and clearance over time (Jeong, 2017; Sun, et al., 2015), which under normal homeostatic conditions, are both rapid (Bateman, et al., 2006; Mawuenyega, et al., 2010). There are two Aβ peptides that result from the amyloidogenic processing of APP, namely the soluble Aβ1–40 and the less soluble and more toxic Aβ1–42 (Kirkitadze & Kowalska, 2005; Serrano-Pozo, et al., 2011). Excessive increase in Aβ1–42 or an increase in the Aβ1–42: Aβ1–40 ratio are thought to be pivotal to the etiology of the pathological cascade in AD patients (Palmer & Love, 2011).

Vascular dysfunction also plays an important role in the development of AD (Dickstein, et al., 2010). Recent data from brain imaging studies in humans and in experimental AD animal models suggest that cerebrovascular dysfunction may precede cognitive decline and onset of neurodegenerative changes in AD (Klohs, et al., 2014; Montagne, et al., 2017). ET-1 has been studied extensively as a mediator of vasomodulation, and the dysregulation of the endothelin system is instrumental to the progression of AD (Palmer, et al., 2013). Many studies have demonstrated that the concentration of ET-1 is increased in both the cerebral cortex (Minami, et al., 1995; Palmer, et al., 2012) and in cerebral blood vessels in AD (Luo & Grammas, 2010; Palmer, et al., 2013). This is in association with significant increases in Aβ which indirectly stimulates production of ET-1 (Pacheco-Quinto & Eckman, 2013; Pacheco-Quinto, et al., 2013; Palmer, et al., 2013). The exposure of human neuroblastoma cells and brain microvascular endothelial cells to Aβ induced increases in the expression of ECE-2 and ECE-1, resulting in increased production and secretion of ET-1 (Palmer, et al., 2009; Palmer, et al., 2012; Palmer, et al., 2013). In addition, ET-1 production is increased in the cerebral vasculature of mice infused with Aβ (Paris, et al., 2003). ET-1 expression is also modulated by astrocytes in AD and a number of other brain pathologies (D’Haeseleer, et al., 2013; Hammond, et al., 2014; Palmer, et al., 2012; Petrov, et al., 2002; Schinelli, 2006; Stiles, et al., 1997). Both astrocyte and glial cells can contribute to the development of secondary brain damage by activating ET receptors in both an autocrine and paracrine manner (Barker, et al., 2014; Esiri, 2007; Hostenbach, et al., 2016).

Most individuals with AD exhibit cognitive impairment and a reduction in CBF before the onset of dementia. (Palmer, et al., 2013). The correlation between cerebral vasoconstriction and microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction further leads to further ET-1 secretion and the release of free radicals which are toxic to neurons (Stankowska, et al., 2017). Hypoxia itself can upregulate components of the endothelin system (Ao, et al., 2002; Kang BY, et al., 2011; Li, et al., 1994; Yamashita, et al., 2001). In AD, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and glucose hypometabolism can result in cognitive decline with time (Daulatzai, 2017). Brain hypoperfusion is assessed by documenting a reduced ratio of myelin-associated glycoprotein compared to proteolipid protein-1 (Barker, et al., 2013; Barker, et al., 2014; Thomas T, et al., 2015) and the decrease in this ratio strongly correlates with the increased expression in ET-1 during AD (Barker, et al., 2014; Love & Miners, 2016; Thomas T, et al., 2015). Significant reduction in CBF has been associated with the presence of white matter lesions in AD resulting in more rapid progression to cognitive impairment compared to AD patients without white matter lesions (Hanaoka, et al., 2016; Kimura N, et al., 2012).

While there is a clear vascular component to the development of AD, it should be noted that neurological and neurodegenerative diseases may be influenced by other factors such as aging, infection (bacteria, virus, parasite) and inflammatory activation (Amor, et al., 2010; De Chiara, et al., 2012). In fact, there are several reports of chronic neuroinflammation due to injury or infection in association with the onset and progression of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease and Multiple Sclerosis (Chen WW, et al., 2016), manifested by activation of microglia, astrocytes, mast cells, T-cells, and inflammatory mediators released from these cells (Shabab, et al., 2017). AD is characterized by glial cell activation, transmigration of macrophages into the brain parenchyma, and accumulation of several essential proteins (Sokolova, et al., 2009; Walter, et al., 2007). It is widely thought that the accumulation of the Aβ is central in the pathogenesis of the disease, as it causes dysfunction and loss of synapses that lead to cognitive deficits (Murphy MP & LeVine, 2010; Sadigh-Eteghad, et al., 2015). Interestingly, ET-1 has been shown to contribute to the inflammatory process induced by Aβ. In a study by Bryial and colleagues, animals were treated with amyloid beta, resulting in increased the expression of the components of ET signaling, oxidative stress, and in cognitive impairment. Treatment with a selective ETA receptor antagonist mitigated these changes (Briyal, et al., 2011)

In summary, recent evidence suggests that ET-1 likely contributes to loss of endothelial functional integrity and cerebrovascular inflammation, by both direct and indirect actions on the cerebral vasculature, leading to neurodegeneration. This provides a potential role for ET-1 in the pathogenesis of AD and a target of therapy.

CONCLUSION

The mechanisms associated with the roles of the endothelin pathways in neuroinflammatory diseases are highly complex. A common pattern nonetheless is recognizable as in all the above described diseases, pathogen-triggered inflammatory response plays a pivotal role in the increase of tissue and/or blood levels of ET-1. This important cross-talk occurs within and outside of the CNS and involves the activation of either or both ETA and ETB receptors whose expression, in some of the diseases discussed above, can be independently or conjointly modulated. In most parasitic diseases described, ET-1 appears to be closely associated with a loss of endothelial integrity as well as changes in BBB permeability. Although interfering with the ET-1 pathway has been successful in reducing morbidity in experimental models of neuro-inflammatory infections, it remains to be validated whether the potent vasoactive peptide is a marker or a mediator in most neurological diseases studied in patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mario Desbiens for artistic support. This work was supported by a Joseph C. Edwards Cardiology Chair (PD-J), Studentship from the Fonds de la Recherche Québec en Santé (LD), Yale University Faculty Excellence and Diversity Initiative award (MSD), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-57883) (PD-J), and the United States National Institutes of Health: Grants AI076248 (HBT), NS069577 (MSD).

This review is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Herbert B. Tanowitz, MD (September 6, 1941 - July 17, 2018), Professor of Pathology and Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Dr. Tanowitz was an esteemed colleague, a friend and mentor who pioneered the studies of endothelin in parasitic diseases.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

Beta-amyloid protein

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CBF

Cerebral blood flow

- CM

Cerebral malaria

- CXCL

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand

- CCL

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand

- CNSV

CNS vasculitis

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- DENV

Dengue virus

- ET

Endothelin

- ET-1

Endothelin-1

- ECE

Endothelin converting enzyme

- ETB

Endothelin subtype B

- ETA

Endothelin subtype A

- EAE

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

- GCA

Giant cells arteritis

- HSV-1

Herpes simplex virus 1

- HSV-2

Herpes simplex virus 2

- HHV

Human herpesvirus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HAND

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders

- ICAM-1

Intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1

- KS

Kaposi’s sarcoma

- KSHV

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

- NO

Nitric oxide

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion protein 1

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- Adams CW, Poston RN, Buk SJ, Sidhu YS, & Vipond H (1985). Inflammatory vasculitis in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci, 69, 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams S, Brown H, & Turner G (2002). Breaking down the blood-brain barrier: signaling a path to cerebral malaria? Trends Parasitol, 18, 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba MA, Espigol-Frigole G, Prieto-Gonzalez S, Tavera-Bahillo I, Garcia-Martinez A, Butjosa M, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, & Cid MC (2011). Central nervous system vasculitis: still more questions than answers. Curr Neuropharmacol, 9, 437–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alencar A, & Elejalde P (1960). O sistema nervoso central na infestaçao experimental do camundongo albino pelo Schizotrypanum cruzi. J Brasil Neurol, 12, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Alencar A (1964). [Clinical and Biological Aspects of Neurological and Muscular Manifestations of South American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ Disease)]. Rev Neuropsiquiatr, 27, 57–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor S, Puentes F, Baker D, & van der Valk P (2010).Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology, 129, 154–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, & Ellis RJ (2007). Dementia and neurocognitive disorders due to HIV-1 infection. Semin Neurol, 27, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, & Wojna VE (2007). Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology, 69, 1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Trotta MP, Lorenzini P, Torti C, Gianotti N, Maggiolo F, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Nasto P, Castagna A, De Luca A, Mussini C, Andreoni M, Perno CF, & Group GS (2007). Virological response to salvage therapy in HIV-infected persons carrying the reverse transcriptase K65R mutation. Antivir Ther, 12, 1175–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Q, Hao C, Xiong M, & Wang D (2002). Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and endothelin-1 gene in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi, 31, 140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, & Nakanishi S (1990). Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature, 348, 730–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza A, & Kim JH (1988). Kaposi’s sarcoma of the dura mater. Hum Pathol, 19, 1461–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton AW, Mukherjee S, Nagajyothi FN, Huang H, Braunstein VL, Desruisseaux MS, Factor SM, Lopez L, Berman JW, Wittner M, Scherer PE, Capra V, Coffman TM, Serhan CN, Gotlinger K, Wu KK, Weiss LM, & Tanowitz HB (2007). Thromboxane A2 is a key regulator of pathogenesis during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Exp Med, 204, 929–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avalos CR, Abreu CM, Queen SE, Li M, Price S, Shirk EN, Engle EL, Forsyth E, Bullock BT, Mac Gabhann F, Wietgrefe SW, Haase AT, Zink MC, Mankowski JL, Clements JE, & Gama L (2017). Brain Macrophages in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected, Antiretroviral-Suppressed Macaques: a Functional Latent Reservoir. MBio, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato A, Rosano L, Di Castro V, Albini A, Salani D, Varmi M, Nicotra MR, & Natali PG (2001). Endothelin receptor blockade inhibits proliferation of Kaposi’s sarcoma cells. Am J Pathol, 158, 841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato A, Loizidou M, Pflug BR, Curwen J, & Growcott J (2011). Role of the endothelin axis and its antagonists in the treatment of cancer. Br J Pharmacol, 163, 220–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahat E, Akman S, Karpuzoglu G, Aktan S, Ucar T, Arslan AG, Nenonen N, Guven AG, & Karpuzoglu T (2002). Visceral Kaposi’s sarcoma with intracranial metastasis: a rare complication of renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant, 6, 505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber RC (2012). The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Scientifica (Cairo), 2012, 246210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker R, Wellington D, Esiri MM, & Love S (2013). Assessing white matter ischemic damage in dementia patients by measurement of myelin proteins. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 33, 1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker R, Ashby EL, Wellington D, Barrow VM, Palmer JC, Kehoe PG, Esiri MM, & Love S (2014). Pathophysiology of white matter perfusion in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Brain, 137, 1524–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes K, & Turner AJ (1997). The endothelin system and endothelin-converting enzyme in the brain: molecular and cellular studies. Neurochem Res, 22, 1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes K, & Turner AJ (1999). Endothelin converting enzyme is located on alpha-actin filaments in smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res, 42, 814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NW, Safai B, Nielsen SL, & Posner JB (1983). Neurological complications of Kaposi’s sarcomat. An analysis of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Neurooncol, 1, 333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, & Chaturvedi UC (2008). Vascular endothelium: the battlefield of dengue viruses. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol, 53, 287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Yadav P, Prasad S, Badole S, Patil D, Kohlapure RM, & Mourya DT (2016). An Early Passage Human Isolate of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus Shows Acute Neuropathology in Experimentally Infected CD-1 Mice. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 16, 496–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RJ, Munsell LY, Morris JC, Swarm R, Yarasheski KE, & Holtzman DM (2006). Human amyloid-beta synthesis and clearance rates as measured in cerebrospinal fluid in vivo. Nat Med, 12, 856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistini B, D’Orleans-Juste P, & Sirois P (1993). Endothelins: circulating plasma levels and presence in other biologic fluids. Lab Invest, 68, 600–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellapart J, Jones L, Bandeshe H, & Boots R (2014). Plasma endothelin-1 as screening marker for cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care, 20, 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Younes-Chennoufi A, Hontebeyrie-Joskowicz M, Tricottet V, Eisen H, Reynes M, & Said G (1988). Persistence of Trypanosoma cruzi antigens in the inflammatory lesions of chronically infected mice. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 82, 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BA, Rusyniak DE, & Hollingsworth CK (1995). HIV-1 gp120-induced neurotoxicity to midbrain dopamine cultures. Brain Res, 705, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C, & Montgomery SP (2009). An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis, 49, e52–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C, Martin DL, & Gilman RH (2011). Acute and congenital Chagas disease. Adv Parasitol, 75, 19–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbeck GL, Molyneux ME, Kaplan PW, Seydel KB, Chimalizeni YF, Kawaza K, & Taylor TE (2010). Blantyre Malaria Project Epilepsy Study (BMPES) of neurological outcomes in retinopathy-positive paediatric cerebral malaria survivors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol, 9, 1173–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt AL (1976). Congenital Chagas disease. Am J Dis Child, 130, 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais V, Fugere M, Denault JB, Klarskov K, Day R, & Leduc R (2002). Processing of proendothelin-1 by members of the subtilisin-like pro-protein convertase family. FEBS Lett, 524, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouallegue A, Daou GB, & Srivastava AK (2007). Endothelin-1-induced signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells. Curr Vasc Pharmacol, 5, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven LA, Middel J, Breij EC, Schotte D, Verhoef J, Soderland C, & Nottet HS (2000). Interactions between HIV-infected monocyte-derived macrophages and human brain microvascular endothelial cells result in increased expression of CC chemokines. J Neurovirol, 6, 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao HJ, & Zulian R (1966). Nerve cell depopulation in chronic Chagas’ disease. A quantitative study in the cerebellum. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 8, 281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehin AC, Mouries J, Frenkiel MP, Dadaglio G, Despres P, Lafon M, & Couderc T (2008). Dynamics of immune cell recruitment during West Nile encephalitis and identification of a new CD19+B220-BST-2+ leukocyte population. J Immunol, 180, 6760–6767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto-Costa R (1971). [Hypothalamic changes in the chronic phase of experimental chagas’ disease]. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 13, 336–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briyal S, Philip T, & Gulati A (2011). Endothelin-A Receptor Antagonists Prevent Amyloid-β-Induced Increase in ETA Receptor Expression, Oxidative Stress, and Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 23, 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner FS, Wilson AJ, & Van Voorhis WC (1999). Detection of live Trypanosoma cruzi in tissues of infected mice by using histochemical stain for beta-galactosidase. Infect Immun, 67, 403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner A, Marquart KH, Mehraein P, & Weis S (1997). Kaposi’s sarcoma in the cerebellum of a patient with AIDS. Clin Neuropathol, 16, 185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrales P, Zanini GM, Meays D, Frangos JA, & Carvalho LJ (2010). Murine cerebral malaria is associated with a vasospasm-like microcirculatory dysfunction, and survival upon rescue treatment is markedly increased by nimodipine. American Journal of Pathology, 176, 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P, Coutellier A, Maistre G, de Gennes C, Frances C, Piette JC, & Godeau P (1995). Plasma endothelin and Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol, 32, 1048–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caradonna K, & Pereiraperrin M (2009). Preferential brain homing following intranasal administration of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun, 77, 1349–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardier JE, Rivas B, Romano E, Rothman AL, Perez-Perez C, Ochoa M, Caceres AM, Cardier M, Guevara N, & Giovannetti R (2006). Evidence of vascular damage in dengue disease: demonstration of high levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules and circulating endothelial cells. Endothelium, 13, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ, & Gascon J (2010). Chagas disease and stroke. Lancet Neurol, 9, 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ, Vargas AP, & Falcao T (2011). Stroke in asymptomatic Trypanosoma cruzi-infected patients. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 31, 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ (2013). American trypanosomiasis. Handb Clin Neurol, 114, 103–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A, & Brew B (2017). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: recent advances in pathogenesis, biomarkers, and treatment. F1000Res, 6, 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JA, Lees JA, Gona JK, Murira G, Rimba K, Neville BG, & Newton CR (2006). Severe falciparum malaria and acquired childhood language disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol, 48, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas C (1911). Nova entidade morbida do homem: Rezumo geral de estudos etiolojicos e clinicos. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 3, 219–275. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas C (1913). Les formes nerveuses d’une nouvelle Trypanosomiase. Nouv Iconogr Salpetr, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Hahn S, Gartner S, Pardo CA, Netesan SK, McArthur J, & Nath A (2007). Molecular programming of endothelin-1 in HIV-infected brain: role of Tat in up-regulation of ET-1 and its inhibition by statins. Faseb J, 21, 777–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Bueno S, & McCracken GH Jr. (2005). Bacterial meningitis in children. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 795–810, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LH, & Wilson ME (2016). Update on non-vector transmission of dengue: relevant studies with Zika and other flaviviruses. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines, 2, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Shibata M, Zidovetzki R, Fisher M, Zlokovic BV, & Hofman F (2001). Endothelin-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 modulation in ischemia and human brain-derived endothelial cell cultures. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 116, 62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WW, Zhang X, & Huang WJ (2016). Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases (Review). Mol Med Rep, 13, 3391–3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew BH, Weaver DF, & Gross PM (1995). Dose-related potent brain stimulation by the neuropeptide endothelin-1 after intraventricular administration in conscious rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 51, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuenkova MV, & Pereiraperrin M (2011). Neurodegeneration and neuroregeneration in Chagas disease. Adv Parasitol, 76, 195–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrady CD, Drevets DA, & Carr DJ (2010). Herpes simplex type I (HSV- infection of the nervous system: is an immune response a good thing? J Neuroimmunol, 220, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter R, Williams C, Ryan L, Erichsen D, Lopez A, Peng H, & Zheng J (2002). Fractalkine (CX3CL1) and brain inflammation: Implications for HIV-1-associated dementia. J Neurovirol, 8, 585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Gatherer D, Hilfrich B, Baluchova K, Dargan DJ, Thomson M, Griffiths PD, Wilkinson GW, Schulz TF, & Davison AJ (2010). Sequences of complete human cytomegalovirus genomes from infected cell cultures and clinical specimens. J Gen Virol, 91, 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ME, Huribal M, Bala RJ, & McMillen MA (1997).Endothelin-1 and endothelin-4 stimulate monocyte production of cytokines. Crit Care Med, 25, 958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, & Friedman-Kien AE (2016). An Update on Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb), 6, 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico M, Berrino L, Maione S, Filippelli A, de Novellis V, & Rossi F (1996). Endothelin-1 in periaqueductal gray area of mice induces analgesia via glutamatergic receptors. Pain, 65, 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Haeseleer M, Beelen R, Fierens Y, Cambron M, Vanbinst AM, Verborgh C, Demey J, & De Keyser J (2013). Cerebral hypoperfusion in multiple sclerosis is reversible and mediated by endothelin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110, 5654–5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orleans-Juste P, Plante M, Honore JC, Carrier E, & Labonte J (2003). Synthesis and degradation of endothelin-1. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 81, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Reznik SE, Spray DC, Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB, Gulinello M, Desruisseaux MS (2010). Persistent cognitive and motor deficits after successful antimalarial treatment in murine cerebral malaria. Microbes Infect, 12, 1198–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Freeman B, Bruno FP, Shikani HJ, Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM, Reznik SE, Stephani RA, & Desruisseaux MS (2012). The novel ETA receptor antagonist HJP-272 prevents cerebral microvascular hemorrhage in cerebral malaria and synergistically improves survival in combination with an artemisinin derivative. Life Sci, 91, 687–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallasta LM, Pisarov LA, Esplen JE, Werley JV, Moses AV, Nelson JA, & Achim CL (1999). Blood-brain barrier tight junction disruption in human immunodeficiency virus-1 encephalitis. Am J Pathol, 155, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Sarma J (2014). Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is an amplifier of virus-induced neuropathology. J Neurovirol, 20, 122–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das T, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Hoarau JJ, Krejbich Trotot P, Denizot M, Lee-Pat-Yuen G, Sahoo R, Guiraud P, Ramful D, Robin S, Alessandri JL, Gauzere BA, & Gasque P (2010). Chikungunya fever: CNS infection and pathologies of a re-emerging arbovirus. Prog Neurobiol, 91, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daulatzai MA (2017). Cerebral hypoperfusion and glucose hypometabolism: Key pathophysiological modulators promote neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res, 95, 943–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davi G, Giammarresi C, Vigneri S, Ganci A, Ferri C, Di Francesco L, Vitale G, & Mansueto S (1995). Demonstration of Rickettsia Conorii-induced coagulative and platelet activation in vivo in patients with Mediterranean spotted fever. Thromb Haemost, 74, 631–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AJ (2010). Herpesvirus systematics. Vet Microbiol, 143, 52–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Chiara G, Marcocci ME, Sgarbanti R, Civitelli L, Ripoli C, Piacentini R, Garaci E, Grassi C, & Palamara AT (2012). Infectious agents and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol, 46, 614–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Queiroz A (1973). Tumor-like lesion of the brain caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 22, 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBiasi RL, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Richardson-Burns S, & Tyler KL (2002). Central nervous system apoptosis in human herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus encephalitis. J Infect Dis, 186, 1547–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deigendesch N, & Stenzel W (2017). Acute and chronic viral infections. Handb Clin Neurol, 145, 227–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbiens L, Lapointe C, Gharagozloo M, Mahmoud S, Pejler G, Gris D, & D’Orleans-Juste P (2016). Significant Contribution of Mouse Mast Cell Protease 4 in Early Phases of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Mediators Inflamm, 2016, 9797021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]