Abstract

Background

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) aims to temporarily replace much of the nicotine from cigarettes to reduce motivation to smoke and nicotine withdrawal symptoms, thus easing the transition from cigarette smoking to complete abstinence.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), including gum, transdermal patch, intranasal spray and inhaled and oral preparations, for achieving long‐term smoking cessation, compared to placebo or 'no NRT' interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group trials register for papers mentioning 'NRT' or any type of nicotine replacement therapy in the title, abstract or keywords. Date of most recent search is July 2017.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials in people motivated to quit which compared NRT to placebo or to no treatment. We excluded trials that did not report cessation rates, and those with follow‐up of less than six months. We recorded adverse events from included and excluded studies that compared NRT with placebo. Studies comparing different types, durations, and doses of NRT, and studies comparing NRT to other pharmacotherapies, are covered in separate reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Screening, data extraction and 'Risk of bias' assessment followed standard Cochrane methods. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months of follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence for each trial, and biochemically validated rates if available. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) for each study. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model.

Main results

We identified 136 studies; 133 with 64,640 participants contributed to the primary comparison between any type of NRT and a placebo or non‐NRT control group. The majority of studies were conducted in adults and had similar numbers of men and women. People enrolled in the studies typically smoked at least 15 cigarettes a day at the start of the studies. We judged the evidence to be of high quality; we judged most studies to be at high or unclear risk of bias but restricting the analysis to only those studies at low risk of bias did not significantly alter the result. The RR of abstinence for any form of NRT relative to control was 1.55 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.49 to 1.61). The pooled RRs for each type were 1.49 (95% CI 1.40 to 1.60, 56 trials, 22,581 participants) for nicotine gum; 1.64 (95% CI 1.53 to 1.75, 51 trials, 25,754 participants) for nicotine patch; 1.52 (95% CI 1.32 to 1.74, 8 trials, 4439 participants) for oral tablets/lozenges; 1.90 (95% CI 1.36 to 2.67, 4 trials, 976 participants) for nicotine inhalator; and 2.02 (95% CI 1.49 to 2.73, 4 trials, 887 participants) for nicotine nasal spray. The effects were largely independent of the definition of abstinence, the intensity of additional support provided or the setting in which the NRT was offered. Adverse events from using NRT were related to the type of product, and include skin irritation from patches and irritation to the inside of the mouth from gum and tablets. Attempts to quantitatively synthesize the incidence of various adverse effects were hindered by extensive variation in reporting the nature, timing and duration of symptoms. The odds ratio (OR) of chest pains or palpitations for any form of NRT relative to control was 1.88 (95% CI 1.37 to 2.57, 15 included and excluded trials, 11,074 participants). However, chest pains and palpitations were rare in both groups and serious adverse events were extremely rare.

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐quality evidence that all of the licensed forms of NRT (gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, inhalator and sublingual tablets/lozenges) can help people who make a quit attempt to increase their chances of successfully stopping smoking. NRTs increase the rate of quitting by 50% to 60%, regardless of setting, and further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of the effect. The relative effectiveness of NRT appears to be largely independent of the intensity of additional support provided to the individual. Provision of more intense levels of support, although beneficial in facilitating the likelihood of quitting, is not essential to the success of NRT. NRT often causes minor irritation of the site through which it is administered, and in rare cases can cause non‐ischaemic chest pain and palpitations.

Plain language summary

Can nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) help people quit smoking?

Background

We reviewed the evidence about whether NRT helps people who want to quit smoking to stop smoking at six months or longer. NRT aims to reduce withdrawal symptoms associated with stopping smoking by replacing the nicotine from cigarettes. NRT is available as skin patches that deliver nicotine slowly, and chewing gum, nasal and oral sprays, inhalators, and lozenges/tablets, all of which deliver nicotine to the brain more quickly than skin patches, but less rapidly than from smoking cigarettes.

Study characteristics

This review includes 136 trials of NRT, with 64,640 people in the main analysis. All studies were conducted in people who wanted to quit smoking. Most studies were conducted in adults and had similar numbers of men and women. People enrolled in the studies typically smoked at least 15 cigarettes a day at the start of the studies. The evidence is current to July 2017. Trials lasted for at least six months.

Key results

We found evidence that all forms of NRT made it more likely that a person's attempt to quit smoking would succeed. The chances of stopping smoking were increased by 50% to 60%. NRT works with or without additional counselling, and does not need to be prescribed by a doctor. Side effects from using NRT are related to the type of product, and include skin irritation from patches and irritation to the inside of the mouth from gum and tablets. There is no evidence that NRT increases the risk of heart attacks.

Quality of evidence

The overall quality of the evidence is high, meaning that further research is very unlikely to change our conclusions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Nicotine replacement therapy.

| Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who smoke cigarettes Settings: clinical and non‐clinical, including over the counter Intervention: nicotine replacement therapy of any form | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Nicotine replacement therapy of any form | |||||

| Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow‐up Follow‐up: 6 to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.55 (1.49 to 1.61) | 64,640 (133 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1, 2 | ||

| 105 per 1000 | 162 per 1000 (156 to 168) | |||||

| Limited behavioural support | ||||||

| 40 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (60 to 64) | |||||

| Intensive behavioural support | ||||||

| 150 per 1000 | 232 per 1000 (224 to 242) | |||||

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Most studies are judged to be at unclear or high risk of bias, but restricting to only studies at low risk of bias did not significantly alter the effect. 2There are likely to be some unpublished trials with less favourable results that we were unable to identify, and a funnel plot showed some evidence of asymmetry. However, given the large number of trials in the review, this does not suggest the results would be altered significantly were smaller studies with lower RRs included.

Background

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) aims to reduce motivation to smoke and the physiological and psychomotor withdrawal symptoms often experienced during an attempt to stop smoking, and therefore increase the likelihood of remaining abstinent (West 2001). Nicotine undergoes first‐pass metabolism in the liver, reducing the overall bioavailability of swallowed nicotine pills. A pill that could reliably produce high enough nicotine levels in the central nervous system would risk causing adverse gastrointestinal effects. To avoid this problem, nicotine replacement products are formulated for absorption through the oral or nasal mucosa (chewing gum, lozenges, sublingual tablets, inhalator, spray) or through the skin (transdermal patches).

Nicotine patches differ from the other products in that they deliver the nicotine dose slowly and passively. They do not replace any of the behavioural activities of smoking. In contrast the other types of NRT are faster‐acting, but require more effort on the part of the user. Transdermal patches are available in several different doses, and deliver between 5 mg and 52.5 mg of nicotine over a 24‐hour period, resulting in plasma levels similar to the trough levels seen in heavy smokers (Fiore 1992). Some brands of patch are designed to be worn for 24 hours whilst others are to be worn for 16 hours each day. Nicotine gum is available in both 2 mg and 4 mg strengths, and nicotine lozenges are available in 1 mg, 1.5 mg, 2 mg and 4 mg strengths. Nicotine nasal sprays are available in either 0.5 mg or 1 mg per spray strengths, and nicotine inhalators are available in both 10 mg and 15 mg strengths. The amount of nicotine absorbed by the user is less than the original dose. None of the available products deliver such high doses of nicotine as quickly as cigarettes. An average cigarette delivers between 1 and 3 mg of nicotine and a person who smokes 20 cigarettes per day absorbs 20 to 40 mg of nicotine each day (Henningfield 2005).

The availability of NRT products on prescription or for over‐the‐counter purchase varies from country to country. Table 2 summarises the products currently licensed in the United Kingdom.

1. Nicotine replacement therapies available in the UK.

| Type | Available doses |

| Nicotine transdermal patches | Worn over 16 hours: 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 25 mg doses Worn over 24 hours: 7 mg, 14 mg, 20 mg, 21 mg, 30 mg doses* |

| Nicotine chewing gum | 2 mg and 4 mg doses |

| Nicotine sublingual tablet | 2 mg dose |

| Nicotine lozenge | 1 mg, 1.5 mg, 2 mg and 4 mg doses |

| Nicotine inhalation cartridge plus mouthpiece | Cartridge containing 10 mg |

| Nicotine metered nasal spray | 0.5 mg dose/spray |

| Nicotine oral spray | 1 mg dose/spray |

Information extracted from British National Formulary

* 35 mg/24‐hour and 53.5 mg/24‐hour patches available in other regions.

This review was first published over 20 years ago, in 1996, and has been regularly updated since. In previous versions, this review addressed not only the effect of NRT in comparison to placebo for helping people stop smoking, but also looked at comparisons between different forms and doses of NRT, and between NRT and different pharmacotherapies. The evidence that NRT helps some people to stop smoking is now well accepted, and many clinical guidelines recommend NRT as a first‐line treatment for people seeking pharmacological help to stop smoking (Fiore 2008; Italy ISS 2004; Le Foll 2005; NICE 2008; NZ MoH 2014; Woolacott 2002; Zwar 2011). We have therefore split the previous version of the review; this review now only looks at NRT versus placebo or no pharmacotherapy, with the intention that, given the stability of this comparison, this review will no longer require regular updates. Studies which compare doses, delivery, forms, and schedules of NRT will now be covered in a companion review, which will continue to be regularly updated, and is in development at the time of writing. Comparisons between NRT and other frontline pharmacotherapies are covered in separate Cochrane Reviews (Cahill 2016; Hughes 2014). Where they meet our other inclusion criteria, studies of NRT in pregnancy are included in the main analysis of this review but are covered comprehensively in a separate Cochrane Review (Coleman 2015), which will continue to be updated. Readers specifically interested in NRT in pregnancy should refer to Coleman 2015.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), including gum, transdermal patch, intranasal spray and inhaled and oral preparations, for achieving long‐term smoking cessation, compared to placebo or 'no NRT' interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials. We also include trials where allocation to treatment was by a quasi‐randomized method, but use appropriate sensitivity analysis to determine whether their inclusion alters the results.

Types of participants

We include men or women who smoked and were motivated to quit, irrespective of the setting from which they were recruited or their initial level of nicotine dependence, or both. We included studies that randomized therapists, rather than smokers, to offer NRT or a control, provided that the specific aim of the study was to examine the effect of NRT on smoking cessation. We have not included trials that randomized physicians or other therapists to receive an educational intervention, which included encouraging their patients to use NRT, but have reviewed them separately (Carson 2012).

Types of interventions

Comparisons of NRT (including chewing gum, transdermal patches, nasal and oral spray, inhalators and tablets or lozenges) versus placebo or no NRT control. The terms 'inhaler' and 'inhalator' (an oral device which delivers nicotine to the buccal mucosa by sucking) are used interchangeably in the literature. We have used the term 'inhalator' throughout the rest of this review.

In some analyses we categorized the trials into groups depending on the level of additional support provided (low or high). The definition of the low‐intensity category was intended to identify a level of support that could be offered as part of the provision of routine medical care. If the duration of time spent with the smoker (including assessment for the trial) exceeded 30 minutes at the initial consultation or the number of further assessment and reinforcement visits exceeded two, we categorized the level of additional support as high. The high‐intensity category included trials where there were a large number of visits to the clinic or trial centre, but these were often brief, spread over an extended period during treatment and follow‐up, and did not include a specific counselling component. To provide a more fine‐grained analysis and to distinguish between high‐intensity group‐based support and other trials within the high‐intensity category, we have therefore specified where the support included multi‐session group‐based counselling with frequent sessions around the quit date.

Previously, this review had also included studies where all arms received NRT (e.g. testing different doses, types) and studies comparing NRT with bupropion. These comparisons are now covered elsewhere; comparisons between different NRT treatments are covered in a companion review, currently under development, and comparisons between NRT and bupropion are found in Hughes 2014.

Types of outcome measures

The review evaluates the effects of NRT versus control on smoking cessation, rather than on withdrawal symptoms. We excluded trials that followed up participants for less than six months, except for trials amongst pregnant women, where the interval between enrolment and delivery may have been shorter (if less than six months, these were excluded from the main analysis). For each study we chose the strictest available criteria to define abstinence. For example, in studies where biochemical validation of cessation was available, we regard only those participants who met the criteria for biochemically‐confirmed abstinence as being abstinent. Wherever possible we chose a measure of sustained cessation rather than point prevalence. We regard people who were lost to follow‐up as being continuing smokers. For the 2012 update and for this current update we collected data on adverse events in both the included and excluded studies, where they were reported. We have not attempted to pool these findings, apart from one meta‐analysis of reports of palpitations, tachycardia or chest pains. We have not included trials that evaluated the effect of NRT for individuals who were attempting to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked rather than to quit in this review. They are covered by a separate review on harm reduction approaches (Lindson‐Hawley 2016).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the specialized register of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group on 6 July 2017 for any reports of trials making reference to the use of nicotine replacement therapy of any type, by searching for 'NRT', or 'nicotine' near to terms for nicotine replacement products in the title, abstract or keywords. The most recent issues of the databases included in the register as searched for the current update of this review were:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 11, 2016;

MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20170526;

Embase (via OVID) to week 201724;

PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20170529.

The search strategy for the Register is given in Appendix 1. For details of the searches used to create the specialized register see the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library. The trials register also includes trials identified by handsearching of abstract books from meetings of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

For earlier versions of this review we performed searches of additional databases: Cancerlit, Health Planning and Administration, Social Scisearch, Smoking & Health, and Dissertation Abstracts. Since the searches did not produce any additional trials we did not search these databases after December 1996. During preparation of the first version of this review, we also sent letters to manufacturers of NRT preparations. Since this did not result in additional data we have not repeated the exercise for subsequent updates.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In previous versions of this review, one review author screened records retrieved by searches, to exclude papers that were not reports of potentially relevant studies. For the last two updates, two review authors independently screened references. Reports that linked to potentially relevant studies but did not report the outcomes of interest are listed along with the main study report in the 'References to Studies' section. The primary reference to the study is indicated, and for most studies the first author and year used as the study identifier corresponds to the primary reference. Where we extracted data for a study from more than one report we have noted this in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from the published reports and abstracts. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by referral to a third party. We made no attempt to blind these review authors either to the results of the primary studies or to which treatment participants received. We examined reports published only in non‐English language journals with the assistance of translators.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed included studies for risks of selection bias (methods of randomized sequence generation, and allocation concealment), performance and detection bias (the presence or absence of blinding), attrition bias (levels and reporting of loss to follow‐up), and any other threats to study validity, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool.

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted smoking cessation rates in the intervention and control groups from the reports at six or 12 months. Since not all studies reported cessation rates at exactly these intervals, we allowed a window period of six weeks at each follow‐up point. For trials which also reported follow‐up for more than a year we used 12‐month outcomes in most cases. (We note length of follow‐up for each study in the Characteristics of included studies table). For trials of NRT in pregnant women, we extracted smoking cessation outcomes at the closest follow‐up to end of pregnancy, and also at longest follow‐up post‐partum if reported. We only included studies in pregnant women in the main analysis if they reported results at six months or longer. Following the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's recommended method of data analysis, we use the risk ratio (RR) for summarizing individual trial outcomes and for estimates of pooled effect. Whilst there are circumstances in which odds ratios may be preferable, there is a danger that they will be interpreted as if they are risk ratios, making the treatment effect seem larger (Deeks 2005).

Dealing with missing data

We treated participants who dropped out or who were lost to follow‐up after randomization as being continuing smokers. We noted in the 'Risk of bias' table the proportion of participants for whom the outcome was imputed in this way, and whether there was either high or differential loss to follow‐up. The assumption that 'missing = smoking' will give conservative absolute quit rates, and will make little difference to the risk ratio unless dropout rates differ substantially between groups.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To assess heterogeneity we use the I2 statistic, given by the formula [(Q ‐ df)/Q] x 100%, where Q is the Chi2 statistic and df is its degrees of freedom (Higgins 2003). This describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). A value greater than 50% may be considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. When there are many trials, as in this review, the Chi2 test for heterogeneity will be unduly powerful and may identify statistically significant but clinically unimportant heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We estimated a pooled weighted average of risk ratios using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel method, with 95% confidence intervals.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In comparing NRT to placebo or control, we performed subgroup analysis for each form of NRT. We did additional subgroup analyses within type of NRT (gum, patch, etc.) to investigate whether the relative treatment effect differed according to the way in which smoking cessation was defined, the intensity of behavioural support, and the recruitment/treatment setting.

Summary of findings table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table. Also following standard Cochrane methodology, we used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the quality of evidence within the text of the review.

The Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Glossary of smoking‐related terms is included in this review (Appendix 2).

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

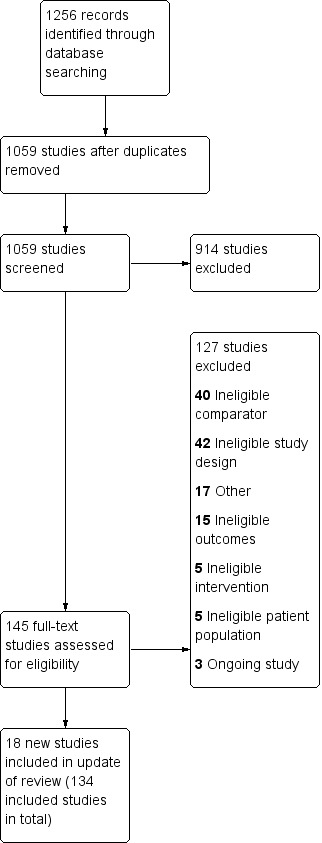

The review includes 136 studies, 18 of which are new in this update (Anthenelli 2016; Berlin 2014; Cummins 2016; Cunningham 2016; El‐Mohandes 2013; Fraser 2014; Gallagher 2007; Graham 2017; Hasan 2014; Heydari 2012; Heydari 2013; Johns 2017; Lerman 2015; NCT00534404; Scherphof 2014; Stein 2013; Tuisku 2016; Ward 2013). Two studies which gave different doses of NRT based on level of dependency are treated as four separate trials for the purpose of this review (Shiffman 2002 (2 mg); Shiffman 2002 (4 mg); Shiffman 2009 (2 mg); Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)). For this update, we also added longer follow‐up data for one previously included study (Coleman 2012). The most recent search screened 1059 studies. Along with the 18 new included studies, there were three ongoing studies, and 124 studies excluded at full‐text screening. The most common reasons for exclusion were ineligible study design and using an irrelevant comparison (NRT vs NRT rather than control). See Figure 1 for study flow information relating to the most recent search presented in a PRISMA diagram. Trials were conducted in North America (62 studies), Europe (56 studies), Australasia (two studies), Japan (two studies), South America (two studies), Iran (two studies), in multiple regions (two studies), and in India, Syria, Taiwan, and Thailand (one study each). The median sample size was 257 but ranged from fewer than 50 to over 8000 participants. We treated each of the intervention groups in the two studies by Shiffman in 2002 and 2009 separately in the meta‐analysis (Shiffman 2002 (2 mg); Shiffman 2002 (4 mg); Shiffman 2009 (2 mg); Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)), and listed Brantmark 1973b, CEASE 1999, Bolliger 2000b, Wennike 2003b, Bullen 2010, Schnoll 2010 in the Characteristics of included studies tables, despite being excluded studies, because they provided data on adverse events.

1.

Study flow diagram for most recent update

Participants

Participants were typically adult cigarette smokers with an average age of 40 to 50. Two trials recruited adolescents (Moolchan 2005; Scherphof 2014). Most trials had approximately similar numbers of men and women. Six trials recruited only pregnant women (Berlin 2014; Coleman 2012; El‐Mohandes 2013; Oncken 2008; Pollak 2007;Wisborg 2000); a further four recruited only women (Cooper 2005; Oncken 2007; Pirie 1992; Prapavessis 2007). Two trials recruited African‐American smokers (Ahluwalia 1998; Ahluwalia 2006).

Trials typically recruited people who smoked at least 15 cigarettes a day. Although some trials included lighter smokers as well, the average number smoked was over 20 a day in most studies. Ahluwalia 2006 recruited only people who smoked 10 or fewer cigarettes a day and two trials recruited only people smoking 30 or more a day (Hughes 1990; Hughes 2003). One trial recruited people with a history of alcohol dependence (Hughes 2003), one recruited methadone‐maintained smokers (Stein 2013), and one recruited people with a history of drug abuse including opiates or narcotics (Heydari 2013). Joseph 1996 recruited people with a history of cardiac disease, Hasan 2014 recruited people admitted to hospital with a cardiac or pulmonary illness, Gallagher 2007 recruited people diagnosed with psychotic‐spectrum or affective disorders resulting in long‐term mental illness and experiencing significant symptoms and functional impairment, and Gourlay 1995 recruited relapsed smokers.

Type and dose of nicotine replacement therapy

One hundred and thirty‐three studies contribute to the primary analysis of the efficacy of one or more types of NRT compared to a placebo or other control group not receiving any type of NRT. In this group of studies there were 56 trials of nicotine gum, 51 of transdermal nicotine patch, eight of an oral nicotine tablet or lozenge, seven offering a choice of products, four of intranasal nicotine spray, four of nicotine inhalator, two providing patch and gum (Hasan 2014; Stein 2013), one of oral spray (Tønnesen 2012), one providing patch and inhalator (Hand 2002), one providing patch and lozenge (Piper 2009), and one providing patch, gum and lozenge (Heydari 2013).

Three studies did not contribute to the primary analysis; two were conducted in pregnant women and did not follow up participants at six months or longer (Berlin 2014; El‐Mohandes 2013), and one was conducted in recently relapsed smokers and is hence reported narratively in the text (Gourlay 1995).

Most trials comparing nicotine gum to control provided the 2 mg dose. A few provided 4 mg gum to more highly addicted smokers, and two used only the 4 mg dose (Blondal 1989; Puska 1979). In three trials the physician offered nicotine gum but participants did not necessarily accept or use it (Ockene 1991; Page 1986; Russell 1983). In one trial participants self‐selected 2 mg or 4 mg doses; we treat the two groups as separate trials in the meta‐analysis (Shiffman 2009 (2 mg); Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)). The treatment period was typically two to three months, but ranged from three weeks to 12 months. Some trials did not specify how long the gum was available. Many of the trials included a variable period of dose tapering, but most encouraged participants to be gum‐free by six to 12 months.

In nicotine patch trials the usual maximum daily dose was 15 mg for a 16‐hour patch, or 21 mg for a 24‐hour patch. Thirty‐two studies used a 24‐hour formulation and nine a 16‐hour product; the rest did not specify. One study offered, among other dosage options, a 52.5 mg/24‐hour patch (Wittchen 2011). If studies tested more than one dose we combined all active arms in the comparison to placebo. For one study we included an arm with a lower maximum dose of 14 mg but excluded a 7 mg‐dose arm (TNSG 1991). The minimum duration of therapy ranged from three weeks (Glavas 2003a, half the participants of Glavas 2003b), to three months.

There are eight studies of nicotine sublingual tablets or lozenges. Three used 2 mg sublingual tablets (Glover 2002; Tønnesen 2006; Wallstrom 2000). One used a 1 mg nicotine lozenge (Dautzenberg 2001). One used 2 mg or 4 mg lozenges according to dependence level based on manufacturers' instructions (Piper 2009), and one used 2 mg or 4 mg based on participants' time to first cigarette of the day (TTFC); smokers whose TTFC was more than 30 minutes were randomized to 2 mg lozenges or placebo (Shiffman 2002 (2 mg)), whilst smokers with a TTFC less than 30 minutes had higher‐dose 4 mg lozenges or placebo (Shiffman 2002 (4 mg)). The two groups are treated in the meta‐analysis as separate trials. One trial did not report the lozenge dose (Fraser 2014). There are four trials of intranasal nicotine spray (Blondal 1997; Hjalmarson 1994; Schneider 1995; Sutherland 1992), one trial of oral nicotine spray (Tønnesen 2012), and four trials of nicotine inhalator (Hjalmarson 1997; Leischow 1996a; Schneider 1996; Tønnesen 1993).

As described above, seven studies tested combinations of patch and a short‐acting form of NRT (Hand 2002; Hasan 2014; Heydari 2013; Kornitzer 1995; Moolchan 2005; Stein 2013; Tønnesen 2000). Six studies offered participants a choice of products (Graham 2017; Johns 2017; Kralikova 2009; Molyneux 2003; Ortega 2011; Pollak 2007).

Treatment setting (studies in main comparison)

Twenty‐one trials in the main comparison recruited participants from primary care practices. A further two gum trials were undertaken in workplace clinics (Fagerström 1984; Roto 1987), and one in a university clinic (Harackiewicz 1988). One trial recruited through community physicians (Niaura 1994). Since participants in these trials were recruited in a similar way to primary care, we have aggregated them in the subgroup analysis by setting. We also included one patch trial conducted in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers and recruiting people with cardiac diseases in the primary care category (Joseph 1996). We kept four trials recruiting pregnant women in antenatal clinics in a separate category (Coleman 2012; Oncken 2008; Piper 2009; Wisborg 2000). Six of the gum trials, two of the nasal spray trials, an inhalator trial, an oral spray trial, and a patch trial were carried out in specialized smoking cessation clinics to which participants had usually been referred. Thirteen trials (five patch, three gum, three giving a combination of products and two giving a choice of products) were undertaken with hospital in‐ or outpatients, some of whom were recruited because they had a co‐existing smoking‐related illness. Three patch trials (Davidson 1998; Hays 1999; Sønderskov 1997) and one gum trial (split into Shiffman 2009 (2 mg) and Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)) were undertaken in settings intended to resemble 'over‐the‐counter' (OTC) use of NRT. Two trials were undertaken in drug abuse treatment centres (Heydari 2013; Stein 2013), one in schools (Scherphof 2014), and one in a psychiatric treatment setting. The remaining trials were undertaken in participants from the community, most of whom had volunteered in response to media advertisements, but who were treated in clinical settings.

Excluded studies

Thirty‐four previously included studies were removed from this update, as they did not contain a NRT‐versus‐control comparison. As described in the Methods, studies which contribute to comparisons between multiple forms of NRT are now found in a separate Cochrane Review, in development at the time of publication. Previously‐included studies that compare NRT with bupropion can be found in Hughes 2014. Other studies that were potentially relevant but excluded are listed with reasons in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Some studies contribute to the adverse events meta‐analysis but not to the main analysis (e.g. due to short follow‐up or short duration of time where comparison was NRT versus control); these are listed in the Characteristics of included studies but we do not count them as included studies. Some studies were excluded due to short follow‐up. Some of these had as their primary outcome withdrawal symptoms rather than cessation. We exclude studies that provided NRT or placebo to people trying to cut down their smoking but not to make an immediate quit attempt, and we consider them in detail in a separate review of interventions for reduction (Lindson‐Hawley 2016). We excluded two trials in which NRT was provided to encourage a quit attempt but participants did not need to be planning to quit: Velicer 2006 proactively recruited people by telephone, with those in one intervention group being mailed a six‐week course of nicotine patches if they were judged to be in the preparation stage or in contemplation and had more pros than cons for quitting; Carpenter 2011 encouraged all participants to make a practice quit attempt, and gave the intervention group trial samples of nicotine lozenges. We excluded one trial in which callers to the NHS Quitline were randomized to be offered free NRT or not to receive the offer; the control group had access to and used free NRT and other stop‐smoking medication at high levels (Ferguson 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

Six trials are included based only on data available from abstracts, conference presentations, or trial registries (Dautzenberg 2001; Johns 2017; Kralikova 2009; Mori 1992; Nakamura 1990; NCT00534404), so had limited methodological details.

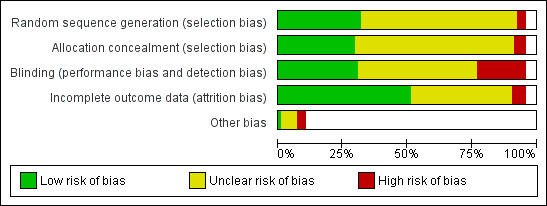

Overall, we judged 12 studies to be at low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains), 36 at high risk of bias (high risk of bias in at least one domain), and the rest at unclear risk of bias. The main findings were not sensitive to the exclusion from the meta‐analysis of trials at unclear risk, or of trials at unclear and at high risk of bias. A summary illustration of the risk of bias profile across trials is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Thirty‐nine studies (29%) reported allocation procedures in sufficient detail to be rated as being at low risk for their attempts to control selection bias, by using a system of treatment allocation which could not be known or predicted until a participant is enrolled and assigned to a study condition. Twenty‐four of these low‐risk trials (62%) also reported adequate sequence generation procedures. Most studies either did not report how randomization was performed and allocation concealed, or reported them in insufficient detail to determine whether a satisfactory attempt to control selection bias had been made (rated as being at unclear risk). A small number of nicotine gum trials randomized to treatment according to day or week of clinic attendance (Page 1986; Richmond 1993; Russell 1983), or to birth date (Fagerström 1984), and were consequently rated as being at high risk of bias. In one study (Gallagher 2007), study staff oversaw allocation and hence we rated this at high risk of bias. One study randomized by physician and there was no information about avoidance of selection bias in enrolment of smokers (Nebot 1992), so we also rated this as being at high risk.

We judged 44 of the included studies to be at low risk of performance and detection bias (33%). We judged 23 (17%) to be at high risk of bias in this domain, most commonly because they were not blinded (although we judged some studies which were not double‐blind to be at low risk in this domain due to other study factors). Forty‐three trials did not have a matched placebo control (24 gum trials, nine patch trials, six choice of product trials, three combination trials, and one lozenge trial). A further two had both a placebo and a non‐placebo control which we combined for the meta‐analysis control group (Buchkremer 1988; Russell 1983). Approximately one‐third of the trials reported some measure of blinding, but we did not assess whether the integrity of the procedure was tested, in line with the CONSORT guidelines (CONSORT 2001). Where they are done, assessments of blinding integrity should always be carried out before the clinical outcome has been determined, and the findings reported (Altman 2004). Mooney 2004 notes that few published trials report this information. While those that do provide some evidence that participants are likely to assess their treatment assignment correctly, it is insufficient to assess whether this is associated with differences in treatment effects. Further, there may be an apparent breaking of the blinding in trials where the treatment effect is marked, for either an intended outcome or an adverse event, but participants who successfully decipher assignment may disguise their unblinding actions (Altman 2004). It is also possible that those who believe that they are receiving a placebo may be more likely to stop trying to quit.

Definitions of abstinence varied considerably. Eighty‐nine trials (66%) reported some measure of sustained abstinence, which included continuous abstinence with not even a slip since quit day, repeated point prevalence abstinence (with or without biochemical validation) at multiple follow‐ups, or self‐reported abstinence for a prolonged period. Thirty‐nine (29%) reported only point prevalence abstinence at the longest follow‐up. In six studies it was unclear exactly how abstinence was defined. In four trials, participants who smoked two or three cigarettes a week were still classified as abstinent (Abelin 1989; Ehrsam 1991; Glavas 2003a; Glavas 2003b). Sensitivity analyses excluding these four trials made no difference to the overall findings. Most studies reported follow‐up at least 12 months from start of treatment. Fifteen gum trials, 19 patch trials, four combination trials, and one lozenge trial in the primary analysis had only six months follow‐up. We report the findings of a subgroup analysis by type of abstinence and length of follow‐up in the Results section.

One hundred and seventeen (87%) of the trials used biochemical validation of self‐reported smoking cessation at longest follow‐up. The most common form of validation was measurement of carbon monoxide (CO) in expired air. The 'cut‐off' level of CO used to define abstinence varied from less than 4 to 11 parts per million. Some of the 21 trials that did not validate all self‐report at longest follow‐up did use biochemical confirmation at earlier points, or validated some self‐reports. The main findings were not sensitive to the exclusion of 17 studies contributing to that analysis that did not attempt to validate all reported abstinence (Ahluwalia 1998; Buchkremer 1988; Clavel‐Chapelon 1992; Daughton 1991; Fraser 2014; Graham 2017; Huber 1988; NCT00534404; Otero 2006; Page 1986; Puska 1979; Roto 1987; Sønderskov 1997; Tuisku 2016; Villa 1999; Wisborg 2000; Wittchen 2011).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

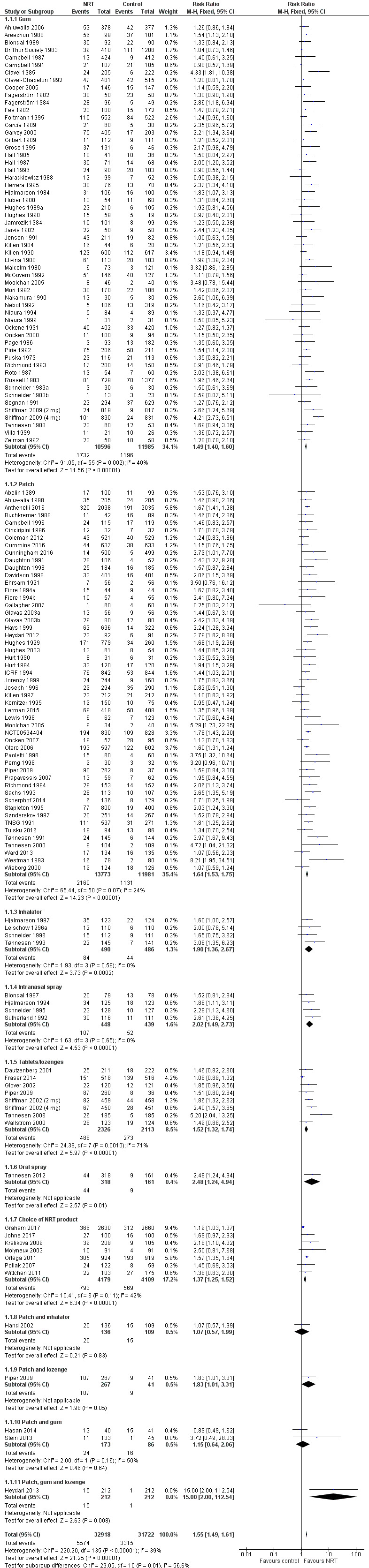

Any type of NRT versus placebo or no NRT control, six months or longer follow‐up

Analysis 1.1 included 131 trials (133 comparisons), with over 64,000 participants (Table 1). A small number of trials contributed to more than one subgroup and two trials were treated as two separate studies in the analyses. Each of the six forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) significantly increased the rate of cessation compared to placebo or no NRT, as did a choice of product. The pooled risk ratio (RR) for abstinence for any form of NRT relative to control was 1.55 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.49 to 1.61; 64,640 participants). The I2 statistic was 39%, indicating that little of the variability was attributable to between‐trial differences. The risk ratio and 95% CI for each type are tabulated below.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any type of NRT versus placebo/no NRT control, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow up.

| Type of NRT | RR | 95% CI | I² | N of studies | N of participants Intervention/Control |

| Gum | 1.49 | 1.40 to 1.60 | 40% | 56* | 10,596 / 11,985 |

| Patch | 1.64 | 1.53 to 1.75 | 24% | 51 | 13,773 / 11,981 |

| Inhalator | 1.90 | 1.36 to 2.67 | 0% | 4 | 490 / 486 |

| Intranasal spray | 2.02 | 1.49 to 2.73 | 0% | 4 | 448 / 439 |

| Tablets/lozenges | 1.52 | 1.32 to 1.74 | 71% | 8* | 2326 / 2113 |

| Oral spray | 2.48 | 1.24 to 4.94 | N/A | 1 | 318 / 161 |

| Choice of product | 1.37 | 1.25 to 1.52 | 42% | 7 | 4179 / 4109 |

| Patch and inhalator | 1.07 | 0.57 to 1.99 | NA | 1 | 136 / 109 |

| Patch and lozenge | 1.83 | 1.01 to 3.31 | N/A | 1 | 267 / 41 |

| Patch and gum | 1.15 | 0.64 to 2.06 | 50% | 2 | 173 / 86 |

| Patch, gum and lozenge | 15.00 | 2.00 to 112.54 | N/A | 1 | 212 / 212 |

| * includes 1 study treated as 2 for analysis; N/A: not applicable | |||||

Although the estimated effect sizes varied across the different products, confidence intervals were wide for the products with higher estimates which had small numbers of trials. One subgroup based on product type had a confidence interval which did not overlap with the pooled estimate; this group consisted of only one study in which only one participant in the control group had successfully quit smoking (Heydari 2013). In the tablets/lozenges subgroup, the I2 statistic was 71%, indicating substantial statistical heterogeneity. In all trials in this subgroup, more participants quit in the intervention arm than in control, but in one study new for this update the point estimate was considerably lower (RR 1.08) (Fraser 2014); this study drove the observed statistical heterogeneity.

Twelve studies had lower quit rates in the treatment than in the control group at the end of follow‐up (all of which had confidence intervals which crossed the line of no effect), and in a further 73% of trials the 95% confidence interval for the RR included 1 (i.e. the trials did not detect a significant treatment effect). Many of these trials had small numbers of smokers, and hence insufficient power to detect a modest treatment effect with reasonable certainty. One large trial of nicotine patches for people with cardiovascular disease had lower quit rates in the intervention than in the control group (Joseph 1996); at six months the quit rates were 14% for active patch and 11% for placebo, but after 48 weeks there had been greater relapse in the active group and rates were 10% and 12% respectively.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Any type of NRT versus placebo/no NRT control, outcome: 1.1 Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow up.

Sensitivity to definition of abstinence

For nicotine gum and patch we assessed whether trials that reported sustained abstinence at 12 months had different treatment effects from those that only reported a point prevalence outcome, or had shorter follow‐up (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2). Subgroup categories were sustained abstinence at 12 months or more, sustained abstinence at six months, point prevalence or unclear definition at 12 months, and point prevalence/unclear at six months. For nicotine gum 32/55 studies (56 comparisons) (58%) reported sustained 12‐month abstinence and the estimate was similar to that for all 55 studies: sustained 12‐month RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.31 to 1.56 (13,737 participants), compared with RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.40 to 1.60. The highest estimate was for the subgroup of eight studies reporting sustained abstinence at six months, where confidence intervals did not overlap: RR 2.77, 95% CI 2.14 to 3.59; 4187 participants. This seems to be attributable to one study (Shiffman 2009 (2 mg); Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)), and is unlikely to be of methodological or clinical significance. For nicotine patch, 21/49 studies (43%) reported sustained 12‐month abstinence, and the RR was also similar to that for all 49 studies: sustained 12‐month RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.74 (7622 participants), compared with RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.53 to 1.75 (25,754 participants) overall). For patch studies there was no evidence that the RRs differed significantly between subgroups.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup: Definition of abstinence, Outcome 1 Nicotine gum. Smoking cessation.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup: Definition of abstinence, Outcome 2 Nicotine patch: Smoking cessation.

Sensitivity to intensity of behavioural support

All trials provided the same behavioural support in terms of advice, counselling, and number of follow‐up visits to the active pharmacotherapy and control groups, but different trials provided different amounts of support. We conducted subgroup analyses by intensity of support for gum and patch trials separately (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2). There was no evidence of a significantly different effect between groups. For nicotine gum the RR was similar across all three subgroups. The control group quit rates varied as expected, averaging 3.5% with low‐intensity support, 9% with high‐intensity individual support and 11.7% with group‐based support. Nicotine patch trials showed the same pattern; the RRs were similar for each subgroup and the average control group quit rates were 9.0% with low‐intensity support, 9.5% with high‐intensity individual support and 17.0% with group‐based support.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup: Level of behavioural support, Outcome 1 Nicotine gum. Smoking cessation.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup: Level of behavioural support, Outcome 2 Nicotine patch. Smoking cessation.

Sensitivity to treatment settings

We conducted further subgroup analyses for each type of setting in which smokers were recruited or treated (with type of NRT as a subgroup beneath setting). The pooled RR for trials in community volunteers where care was provided in a medical setting was 1.62 (95% CI 1.53 to 1.72, 65 trials, 24,597 participants; Analysis 4.1) and was similar to that of trials conducted in smoking clinics (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.96, 12 trials, 3300 participants; Analysis 4.2), trials conducted in primary care settings (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.69, 24 trials, 11,974 participants; Analysis 4.3), trials conducted in hospitals (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.55, 13 trials, 7037 participants; Analysis 4.4), and trials conducted in settings similar to 'over the counter' (OTC) (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.55, 9 trials, 13,163 participants; Analysis 4.5). Pooled results from four trials in antenatal clinics were lower than in other settings (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.62, 1675 participants; Analysis 4.6); this was the only setting in which results did not show a statistically significant effect of the intervention. In a meta‐regression we checked whether there was any evidence of interaction between the treatment setting and type of NRT used. The effect of nicotine gum was highest in the OTC setting and this seems to be attributable to the same study that contributed heterogeneity in the abstinence subgroup analysis above (Shiffman 2009 (2 mg); Shiffman 2009 (4 mg)).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 1 Community volunteer (treatment provided in medical setting).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 2 Smoking clinic.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 3 Primary care.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 4 Hospitals.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 5 Community volunteer (treatment provided in 'over‐the‐counter' setting).

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Subgroup: Recruitment/treatment setting, Outcome 6 Antenatal clinic.

Control group quit rates varied by setting; the lowest rates were found in OTC (8.4%) and primary care (6.9%) studies, and the highest rate in smoking clinics (14.3%). Falling within this range, control group rates were 9.3% in antenatal clinics, 12.5% in community volunteers where treatment was provided in a medical setting, and 12.3% in hospitals.

Sensitivity to risk of bias and study methods

Excluding those studies at high risk of bias did not significantly alter the point estimate for the main comparison: RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.52 to 1.69, analysis not shown. Similarly, restricting the main analysis to only those 12 studies at low risk of bias across all domains led to results consistent with the main analysis: RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.71, analysis not shown. Removing those studies without biochemical validation did not substantially influence the effect estimate: RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.55 to 1.70, analysis not shown, nor did restricting the analysis to only placebo‐controlled studies: RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.53 to 1.70, analysis not shown.

Relapsed smokers

Although many of the trials reported here did not specifically exclude people who had previously tried and failed to quit with NRT, one trial recruited people who had relapsed after patch and behavioural support in an earlier phase of the study but were motivated to make a second attempt (Gourlay 1995). This study did not detect an effect on continuous abstinence (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.60, analysis not shown), although it did detect a significant increase in 28‐day point prevalence abstinence (RR 2.49, 95% CI 1.11 to 5.57). Quit rates were low in both groups with either definition of abstinence.

Adverse events

We have made no systematic attempt in this review to synthesize quantitatively the incidence of the various adverse events reported with the different NRT preparations. This was because of the extensive variation in reporting of the nature, timing and duration of symptoms. In the included studies, attrition rates in NRT groups were generally similar to or lower than in control groups. Appendix 3 summarises the main adverse events reported in the included and excluded studies, where the data were available.

The most common adverse events usually reported with nicotine gum include hiccoughs, gastrointestinal disturbances, jaw pain, and orodental problems (Fiore 1992; Palmer 1992). The only adverse event that appears to interfere with use of the patch is skin sensitivity and local skin irritation; this may affect up to 54% of patch users, but it is usually mild and rarely leads to withdrawal of patch use (Fiore 1992). The major adverse events reported with the nicotine inhalator and nasal and oral sprays are related to local irritation at the site of administration (mouth and nose respectively). For example, symptoms such as throat irritation, coughing, and oral burning were reported significantly more frequently with participants allocated to the nicotine inhalator than to placebo control (Schneider 1996); none of the experiences, however, were reported as severe. With the nasal spray, nasal irritation and runny nose are the most commonly reported adverse events. In the study of oral spray, hiccoughs and throat irritation were the most commonly reported adverse events (Tønnesen 2012). Nicotine sublingual tablets have been reported to cause hiccoughs, burning and smarting sensation in the mouth, sore throat, coughing, dry lips and mouth ulcers (Wallstrom 1999). Adolescents report similar adverse events to adults (Bailey 2012).

A review of adverse events based on 35 trials with over 9000 participants did not find evidence of excess adverse cardiovascular events amongst those assigned to nicotine patch, and the total number of such events was low (Greenland 1998). A meta‐analysis of adverse events associated with NRT included 92 RCTs and 28 observational studies, and addressed a possible excess of chest pains and heart palpitations among users of NRT compared with placebo groups (Mills 2010). The authors report an OR of 2.06 (95% CI 1.51 to 2.82) across 12 studies. We replicated this data collection exercise and analysis where data were available (included and excluded) in this review, and detected a similar but slightly lower estimate, OR 1.88 (95% CI 1.37 to 2.57; 15 studies; 11,074 participants; OR rather than RR calculated for comparison; Analysis 6.1). Chest pains and heart palpitations were an extremely rare event, occurring at a rate of 2.5% in the NRT groups compared with 1.4% in the control groups in the 15 trials in which they were reported at all. A recent network meta‐analysis of cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (Mills 2014), including 21 RCTs comparing NRT with placebo, found statistically significant evidence that the rate of cardiovascular events with NRT was higher (RR 2.29 95% CI 1.39 to 3.82). However, when only serious adverse cardiac events (myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death) were considered, the finding was not statistically significant (RR 1.95 95% CI 0.26 to 4.30). A sensitivity analysis demonstrated that lower‐level events, predominantly tachycardia and arrhythmia, accounted for the observed increased risk of cardiovascular events. Chest pains and palpitations are the only clinically significant adverse events to emerge from the trials, and no evidence of significant harm has been identified.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Palpitations in NRT vs placebo users, Outcome 1 Palpitations/chest pains.

When first licensed there was concern about the safety of NRT in smokers with cardiac disease (TNWG 1994). A trial of nicotine patch that recruited smokers aged over 45 with at least one diagnosis of cardiovascular disease found no evidence that serious adverse events were more common in smokers in the nicotine patch group (Joseph 1996). Events related to cardiovascular disease, such as an increase in angina severity, occurred in approximately 16% of participants, but did not differ according to whether or not they were receiving NRT. A review of safety in people with cardiovascular disease found no evidence of an increased risk of cardiac events (Joseph 2003). This included data from two randomized trials with short‐term follow‐up that we excluded from the present review (Tzivoni 1998; Working Group 1994), and a case‐control study in a population‐based sample. An analysis of 187 smokers admitted to hospital with acute coronary syndromes who received nicotine patches showed no evidence of difference in short‐ or long‐term mortality compared to a propensity‐matched sample of smokers in the same database who did not receive NRT (Meine 2005). A subgroup analysis within a network meta‐analysis of cardiovascular events (Mills 2014), found no increased risk of cardiovascular events with NRT amongst individuals with predisposing conditions that placed them at an increased risk of having an event (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.77 to 2.02). Another recent network meta‐analysis in people with cardiovascular disease found a slightly higher number of cardiovascular events with NRT but was not able to draw quantitative conclusions due to the low number of trials reporting adverse events and the variation in adverse event definitions used (Suissa 2017).

The six trials assessing NRT use in pregnant women did not detect significant increases in serious adverse events amongst the treatment groups (Berlin 2014; Coleman 2012; El‐Mohandes 2013; Oncken 2008; Pollak 2007; Wisborg 2000). The effects of NRT use on neonatal health are discussed further in a separate Cochrane Review, which found no statistically significant differences in rates of any serious adverse events between treatment and control groups (Coleman 2015). As mentioned previously, this separate review covers this topic comprehensively and will be regularly updated, so interested readers should refer to Coleman 2015 for more information on the adverse events profile of NRT in pregnancy.

Discussion

This review provides high‐quality evidence from trials including over 64,000 participants that offering nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to dependent smokers who are prepared to try to quit increases their chance of success over that achieved with the same level of support but without NRT. This applies to all forms of NRT and is independent of any variations in methodology or design characteristics of trials included in the meta‐analysis. In particular we did not find evidence that the relative effect of NRT was smaller in trials with longer follow‐up beyond our six‐month minimum for inclusion. We did not compare end‐of‐treatment risk ratios with post‐treatment follow‐up, and relapse rates may be higher in active treatment participants once they stop using NRT products, but later relapse is probably unrelated to NRT use (Etter 2006).

The absolute effects of NRT use will depend on the baseline quit rate, which varies in different clinical settings. Studies of people attempting to quit on their own suggest that success rates after six to 12 months are 3% to 5% (Hughes 2004). Use of NRT might be expected to increase the rate by 2% to 3%, giving a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 56. If, however, the quit rate without pharmacotherapy was estimated to be 15%, either because the population had other predictors of successful quitting or received intensive behavioural support, then another 8% might be expected to quit, giving an NNTB of 11.

Intensity of additional support and treatment setting

We did not detect important differences in relative effect within patch or gum studies by our classification of level of support. A letter prior to the previous update of this review identified inconsistencies in the classification of low‐ and high‐intensity support in this review (Walsh 2007). In response, we changed the classification of a small number of trials. This did not alter the conclusion that intensity of support does not appear to be an important moderator of NRT effect.

We also did not detect differences in relative effect according to the setting of recruitment and treatment. This subgroup analysis had considerable overlap with the support subgroup since, for example, people recruited in primary care settings typically had lower‐intensity support.

There has been continuing debate about the amount of evidence for the efficacy of NRT when obtained OTC without advice or support from a healthcare professional (Hughes 2001; Walsh 2000; Walsh 2001). The small number of placebo‐controlled trials in settings intended to replicate OTC settings support the conclusion that the relative effect of NRT is similar to settings where more advice and behavioural support is provided, although quit rates in both control and intervention groups have been low. One other meta‐analysis supports the conclusion of efficacy, although it differs in its inclusion criteria (Hughes 2003). In addition to the same three trials comparing nicotine patch to placebo in an OTC setting (Davidson 1998; Hays 1999; Sønderskov 1997), that review includes one study excluded here due to short follow‐up (Shiffman 2002a). It also pools four trials comparing NRT provided OTC to NRT provided under prescription. We exclude one trial that compared both gum and patch in these settings, but was not randomized (Shiffman 2002b), and another that has not been published and for which we have been unable to obtain reliable data for inclusion (Korberly 1999). The abstract reported that there were no significant differences in quit rates between users of nicotine patch who purchased it through a non‐healthcare facility, and those receiving it on prescription. It has also been suggested that the 'real world' effectiveness of NRT declines or disappears once it becomes available to purchase without requiring contact with a health professional who can offer behavioural support and guidance on appropriate use (Kotz 2014; Pierce 2002). A comparison of two cross‐sectional surveys in California found that quit rates for self‐selected NRT users were higher than rates for non‐users prior to OTC availability, but after the switch to OTC this difference disappeared (Pierce 2002). In addition, a prospective cohort study found that the odds of cessation in people who had used OTC NRT were lower than in people who had not used any cessation pharmacotherapy or accessed a national stop‐smoking service (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.94) (Kotz 2014). However, these observational studies are at risk of residual confounding from unmeasured confounders, such as psychological factors, as participants self‐selected their treatment. These studies are also at risk of bias, as unaided quit attempts are less likely to be recalled than those involving NRT.

A report of a prospective cohort study questioned the effectiveness of NRT outside of the clinical trial setting after finding no difference in relapse rates between smokers trying to quit who used NRT and those who did not use NRT (Alpert 2012). However, the design of this study has been criticized for not addressing initial quit rates in the two groups (Stapleton 2012). Furthermore, two multi‐country prospective cohort studies observed that NRT users had higher quit rates than non‐users (Kasza 2012; West 2007), although in the former study this effect was limited to NRT patches, with no effect detected for oral nicotine products. Again, these are observational studies and are at risk of confounding and bias.

Trials in special populations

Trials generally restricted recruitment to adults over the age of 18; in a small number of trials the age range was not specified. Two relatively small studies in adolescents did not detect an effect of NRT on quitting at six months or longer (Moolchan 2005; Scherphof 2014). A separate Cochrane Review of tobacco cessation interventions for young people did not detect an effect of NRT, although confidence intervals were wide and did not preclude the possibility of a clinically important effect (Fanshawe 2017). This is likely to remain an active area of research.

This review previously conducted a separate analysis on a subgroup of studies evaluating NRT in pregnant women. This is covered by a separate Cochrane review (Coleman 2015) which provides more comprehensive analysis of these studies and will be regularly updated (whereas this review is now marked as stable and will no longer be updated). Therefore, readers interested in this topic should refer to (Coleman 2015).

Evidence for differential treatment effects in different subgroups

We made no attempt to conduct separate analyses for any subgroups of trial participants, because subgroup results are uncommon in trial reports, and where data cannot be obtained from all studies there is a risk of bias from using incomplete data. Munafó 2004a has reported the results of a meta‐analysis of nicotine patch by sex. The researchers were able to include data from 11 out of 31 eligible trials (35%) and 36% of study participants. They found no evidence that the nicotine patch was more effective for men than for women, as has been hypothesized; although men showed a somewhat bigger benefit from NRT at 12 months, the difference was not significant. There was also no difference in average placebo quit rates between men and women, which has been reported in some studies. In a commentary some additional data were identified (Perkins 2004), but this did not alter the conclusions (Munafó 2004b). A second meta‐analysis of any type of NRT reported that in women the odds ratio for cessation declined with increasing length of follow‐up, with a non‐significant difference at 12 months (Cepeda‐Benito 2004). Amongst men the odds ratio declined less over time and remained significant. Based on a further subgroup analysis, they also reported that the decline in long‐term efficacy in women was greater in trials with low‐intensity support than with high‐intensity support, suggesting that the more intensive support helped prevent late relapse in women who had initially received NRT. Although there was no evidence of bias, the review could only include a subset of published studies, so the finding should be regarded as hypothesis‐generating. All review authors agreed that trials are underpowered to identify any interaction between treatment and any type of individual characteristics, and recommended public archiving of data from studies, as well as new research specifically designed to test group‐by‐treatment interactions. At the moment there does not appear to be sufficient evidence of clinically important differences between men and women to guide treatment matching.

Re‐treating relapsed smokers

Whilst end‐of‐treatment success rates may be quite high, many people relapse after the end of therapy. There is suggestive evidence that repeated use of NRT in people who have relapsed after an initial course may produce further quitters, although the absolute effect is small (Gourlay 1995). A subgroup analysis in another trial indicated that the relative effect of treatment with nicotine patch compared to placebo was at least as high for people who had used NRT before (Jorenby 1999, reported in Durcan 2002). The authors noted that there was no way to distinguish between people who had completely failed to quit using NRT and those who had been initially successful but relapsed.

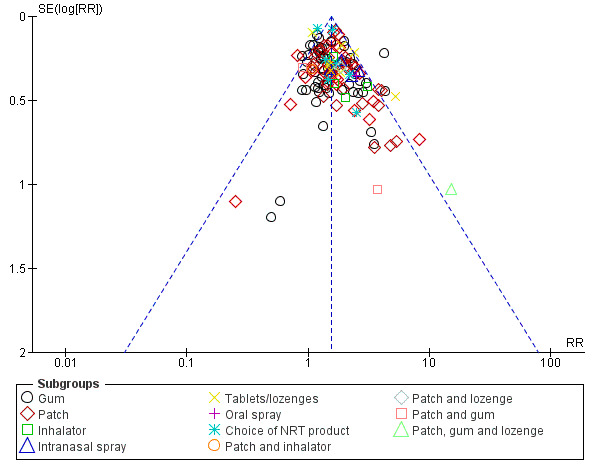

Limitations of the evidence base

Two possible limitations to this evidence base need to be borne in mind: risk of bias in individual studies and publication bias. For the former, although we judged most of our included studies to be at unclear or high risk of bias in at least one domain, restricting the analysis to only those studies at low risk of bias overall did not significantly alter the pooled effect. For the latter, we tried to partly address any shortcomings from having limited our analysis to reported data by approaching investigators, where necessary, to obtain additional unpublished data or to clarify areas of uncertainty. Although we took steps to minimize publication bias by writing to the manufacturers of NRT products when this review was first prepared, the response was poor and we have not repeated this exercise, although we have searched clinical trials registries. It is therefore possible that there are some unpublished trials, with less favourable results, that we have not identified despite our efforts to do so. A funnel plot (Figure 4) shows some evidence of asymmetry for trials in the main comparison; however, given the large number of trials in the review, the funnel plot does not suggest that results would be altered significantly were smaller studies with lower RRs included. A meta‐analysis has also demonstrated that nicotine gum and patch studies that received pharmaceutical industry funding have on average slightly higher effect sizes than other studies after controlling for some trial characteristics (Etter 2007). The practical effect of these considerations is that the magnitude of the effectiveness of NRT may be smaller than our estimates suggest.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Any type of NRT versus placebo/no NRT control, outcome: 1.1 Smoking cessation at 6+ months follow up.

A possible further limitation relates to length of follow‐up. This review excludes studies with less than a six‐month follow‐up from the start of treatment; the outcome used reflects the effect of NRT after the end of active treatment. A comparison of abstinence rates during treatment and abstinence at one year suggests that the relative effect of NRT declines once active therapy stops (Fagerström 2003), i.e. people who quit with the help of NRT are a little more likely to relapse after they discontinue treatment than those on placebo. The relative effect of NRT could continue to decline even after a year of follow‐up. However, a meta‐analysis comparing one‐year and long‐term outcomes in 12 NRT trials with follow‐up beyond one year suggested that the relative efficacy did not change, with similar relapse rates in the active and placebo groups, but further relapse does reduce the absolute difference in quit rates (Etter 2006).

Stability of the evidence base

This review was first published in 1996. Despite the number of included studies more than doubling over this time, the effect estimate has remained remarkably stable, and our intention is that this publication is the final time the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group will review the evidence comparing NRT to placebo or to no pharmacotherapy. This is not to say that all questions about NRT have been answered; evidence is still needed comparing different forms, doses, and durations of NRT, comparing NRT to other pharmacotherapies, and testing NRT in special populations where we may reasonably hypothesize that its effectiveness differs from that in the general population (e.g. pregnant women, adolescents). Further studies are also needed of electronic cigarettes containing nicotine, which some consider a form of NRT (but which we have never included in this review). However, we will cover these in separate reviews which we will continue to update regularly (Cahill 2016; Coleman 2015; Fanshawe 2017; Hartmann‐Boyce 2016; Hughes 2014). In summary, based on 20 years of research and 136 randomized controlled trials in over 64,000 participants, we believe the question of whether NRT helps people to quit smoking to be definitively answered. We consider that further research is highly unlikely to change our confidence in the effect of NRT, and funders and researchers should give careful thought before pursuing further studies comparing established forms of NRT with control.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

All of the commercially available forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), i.e. gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, inhalator, oral spray, lozenge and sublingual tablet, are effective as part of a strategy to promote smoking cessation. They increase the rate of long‐term quitting by approximately 50% to 60%, regardless of setting. These conclusions apply to smokers who are motivated to quit. There is little evidence about the role of NRT for individuals smoking fewer than 10 to 15 cigarettes a day.

The form of delivery of NRT is unrelated to effectiveness, so other considerations such as preferences, availability, or cost might determine the form of NRT chosen.

The effectiveness of NRT, in terms of the risk ratio, appears to be largely independent of the intensity of additional support provided. Intensive behavioural support is not essential for NRT to be effective. However, it should be noted that the absolute increase in success rates attributable to the use of NRT will be larger when the baseline chance of success is already raised by the provision of intensive behavioural support.

NRT causes non‐ischaemic chest pain and palpitations in a minority of users but there is no evidence of an excess of serious cardiac problems, even in people with established cardiac disease.

NRT commonly leads to minor adverse reactions which reflect irritation of the site of use of the form of NRT. These reactions are usually not severe enough to prompt discontinuation of treatment

Implications for research.

There is high‐quality evidence that nicotine replacement therapy increases quit rates at six months or longer in adults motivated to quit. We consider that further research is highly unlikely to change our confidence in the effect of NRT in this population.

Feedback

How should efficacy be measured?

Summary

The comment (December 2002) states that NRT is not more effective than abrupt cessation. We summarise the supporting arguments and our response to each below:

Reply

1. Pierce & Gilpin (Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Impact of over‐the‐counter sales on effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids for smoking cessation. JAMA 2002;288:1260‐4) found no difference in long‐term cessation rates between those who did and who did not use NRT.

This point is addressed in a letter commenting on the study (Stead LF et al. Effectiveness of over‐the‐counter nicotine replacement therapy. JAMA 2002;288:3109‐10). The main limitation of their study is that the comparison between groups of people who chose or did not chose to use NRT, These two groups probably differ in many respects related to their chance of successful quitting, and it is impossible to adjust for these possible confounders. Therefore the conclusions of the study are stronger than the evidence justifies.

The criticism authors also cite the Minnesota insurance review (Boyle RG et al. Does insurance coverage for drug therapy affect smoking cessation? Health Affairs 2002 Nov‐Dec;21:162‐8) but it does not seem to give further support to the point made. The main finding of Boyle et al was that introducing an insurance benefit did not increase use of NRT.

2. In the real‐world those relying exclusively upon NRT are relapsing and dying at pre‐NRT rates.

This is an assertion which is not supported by evidence.

3. NRT study instruction is designed and sequenced in order to foster device transfer. In fact the placebo group must be deprived of critical abrupt cessation instructional tips because if given and followed many could have a negative impact upon the active group.

The review does not make the assertion or implication attributed to it. In the studies involving behavioural support as well as active versus placebo NRT, both active and placebo groups are typically given instructions designed to maximise their chances of success. In these circumstances NRT if anything shows a larger advantage over placebo than it does in minimal support settings. If it is being asserted that placebo groups are being deprived of progressive cigarette weaning or some form of lapse management strategy, there is no evidence to suggest that this approach is effective.

4. The duration of abstinence for NRT groups should begin from the time they stop using NRT.

In response to this it should be noted that it is cigarettes which are causing the harm to health and the aim is to help people stop smoking. Secondly, studies that have followed up smokers long‐term show that the medication genuinely improves long‐term cessation rates and does not simply set the relapse clock back by the time period when nicotine replacement is being used.

5. There are clinic programmes achieving success rates at least as good as those using NRT.

It is necessary to make direct comparisons ensuring that the same criteria are applied to both groups to be able to draw conclusions.

Finally it must be noted that the Cochrane review shows that NRT is estimated to help some 7% smokers to stop long‐term who would not have stopped had they used a similar approach but without NRT. This effect is small but given the health benefits from stopping smoking it is a highly cost‐effective life‐preserving medication. That is not to say that other interventions, including a different kind of behavioural intervention that was incompatible with NRT could not get better results. However, it is not enough just to assert the possibility; with so many lives at stake it would be imperative to demonstrate the effectiveness of such approaches.

Contributors

Comment by John R. Polito. Response by Tim Lancaster & Lindsay Stead on behalf of review authors. Criticism editor Robert West.

How should effectiveness be measured

Summary

The comment (October 2003) suggests that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) alone cannot establish the effectiveness of an intervention in a population.

Reply

RCTs establish the size of effect of an intervention in a particular context in a sample who are eligible and willing to receive the intervention. It always remains possible that the effect size would be different in a different population under different conditions which is why it is important to assess in RCTs how representative the samples are, and how far the context of the trial represents the likely clinical scenarios in which the intervention will be applied. In other words an RCT seeks to achieve internal validity (corresponding to efficacy) and aspires to maximise external validity (corresponding to effectiveness). A 'real‐world' comparison of two groups that are not comparable, and where the differences are not adequately controlled for by design or analysis, does not permit attribution of differences or similarities in outcome to the intervention under investigation.

Contributors

Comment by John Pierce. Reply by Lindsay Stead & Tim Lancaster on behalf of review authors. Criticism Editors: Robert West (internal), Lisa Bero (external).

Impact of failure to assess blinding on validity

Summary

The comment (May 2004) drew attention to a recent paper (Mooney M, White T, Hatsukami D. The blind spot in the nicotine replacement therapy literature: assessment of the double‐blind in clinical trials. Addictive Behaviors 2004; 29(4):673‐684) that notes that most NRT trials do not report whether blinding was maintained, and of those that did, blinding failure was common. The comment also suggests that smokers failing to quit with an NRT‐assisted attempt will not benefit from NRT use in subsequent attempts, and questions whether people who quit smoking but continue to use NRT should be regarded as having quit or not.

Reply