Abstract

Animals need to be able to alter their developmental and behavioral programs in response to changing environmental conditions. This developmental and behavioral plasticity is mainly mediated by changes in gene expression. The knowledge of the mechanisms by which environmental signals are transduced and integrated to modulate changes in sensory gene expression is limited. Exposure to ascaroside pheromone has been reported to alter the expression of a subset of putative G protein-coupled chemosensory receptor genes in the ASI chemosensory neurons of C. elegans (Kim et al., 2009; Nolan et al., 2002; Peckol et al., 1999). Here we show that ascaroside pheromone reversibly represses expression of the str-3 chemoreceptor gene in the ASI neurons. Repression of str-3 expression can be initiated only at the L1 stage, but expression is restored upon removal of ascarosides at any developmental stage. Pheromone receptors including SRBC-64/66 and SRG-36/37 are required for str-3 repression. Moreover, pheromone-mediated str-3 repression is mediated by FLP-18 neuropeptide signaling via the NPR-1 neuropeptide receptor. These results suggest that environmental signals regulate chemosensory gene expression together with internal neuropeptide signals which, in turn, modulate behavior.

Keywords: chemoreceptor, gene expression, neuropeptide signaling, pheromone, plasticity

INTRODUCTION

Proper chemosensory gene expression and its flexible modulation are essential to generate and shape behaviors of animals. A key feature of chemosensory gene expression is that it is highly dynamic and is extensively modulated by changes in external and internal conditions (Barth et al., 1996; Fox et al., 2001; Sengupta, 2013; Ryu et al., 2017). It is now well-established that plasticity of chemosensory gene expression mediates behavioral changes and thus plays a pivotal role in the ability to find food sources or avoid predators. However, the mechanisms underlying this type of gene expression plasticity are still not well-known and require further detailed genetic, physiological, and behavioral analyses.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is an excellent model system in which to study plasticity of chemosensory gene expression. The C. elegans genome encodes over 1,500 predicted GTP-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptor (GPCR) genes, most of which appear to be putative chemoreceptor genes (Robertson and Thomas, 2006; Sengupta et al., 1996; Troemel et al., 1995). Gene expression of these chemoreceptor genes appears to be plastic and can be altered by external environmental conditions and/or the internal metabolic state including the presence of pheromones, upon starvation, or by alteration of the ambient temperature (Gruner et al., 2014; 2016; Kim et al., 2009; Nolan et al., 2002; Peckol et al., 2001; Ryan et al., 2014; Satterlee et al., 2004; Suo et al., 2006). For example, the expression of a srh-234 chemoreceptor gene in the ADL chemosensory neurons is down-regulated in starved animals (Gruner et al., 2014; 2016) and odr-10 diacetyl receptor expression in the AWA chemosensory neurons is modulated by the feeding state and somatic sex (Ryan et al., 2014). However, the molecular and neuronal mechanisms underlying plasticity of chemosensory gene expression have yet to be fully determined.

C. elegans secretes a complex cocktail of small chemicals collectively called dauer pheromone (Butcher et al., 2007; Edison, 2009; Golden and Riddle, 1982; Jeong et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2018). Distinct components of ascaroside pheromone appear to affect many aspects of C. elegans development and behavior (Ludewig and Schroeder, 2013). For example, at the early larval developmental stage, a set of ascaroside pheromones act as a population density indicator to determine dauer formation (Butcher et al., 2007; 2008; Cassada and Russell, 1975; Hirsh and Vanderslice, 1976; Jeong et al., 2005). In addition, ascarosides elicit acute behavioral changes (Greene et al., 2016; Jang et al., 2012; Park et al., 2017; Srinivasan et al., 2008; 2012). For example, acute exposure to ascr#3 (asc-ΔC9, C9 ascaroside, daumone-3) causes an avoidance behavior in adult animals, which is further modulated by previous experience and feeding state (Hong et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2018). It was previously shown that chronic exposure to ascaroside pheromone down-regulates expression of putative G protein-coupled chemosensory receptor genes including str-3 in the chemosensory ASI neurons (Kim et al., 2009; Neal et al., 2016; Nolan et al., 2002; Peckol et al., 2001). Here, we attempted to further investigate conditions in which str-3 expression is affected. We found that str-3 expression is repressed by the presence of ascaroside but not by the feeding state or ambient temperature. Pheromone exposure at the L1 larval stage was required for repression of str-3 GPCR expression, which could be de-repressed at any developmental stage when the pheromone was removed. Moreover, the down regulation of str-3 expression upon pheromone exposure was dependent on FLP-18 neuropeptide and its receptor, NPR-1. This study hence indicates that chemoreceptor expression in these chemosensory neurons is modulated by secreted pheromone cues that may reflect the internal metabolic and physiological conditions of the worms and is further influenced by endogenous neuropeptide signaling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Genetics

The C. elegans N2 strain was used as wild-type. All strains were maintained at 20°C on Escherichia coli OP50-seeded NGM plates. The mutants and transgenic strains used in this study included: CX3596 kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK742 srbc-64(tm1946); srbc-66(tm2943); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK787 srg-36 srg-37(kyIR88); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK487 flp-18(tm2179); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK1355 npr-1(ad609); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK488 unc-31(e169); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK 485 npr-4(tm1782); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, KHK486 npr-5(rb1393); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X, and KHK1763 flp-18(tm2179);npr-1(ad609); kyIs128[str-3p::gfp] X.

Crude pheromone and synthetic ascarosides

Crude pheromone was prepared following the protocol described in by Golden and Riddle (1984). The ascaroside pheromone components including ascr#2 (asc-C6-MK, C6 ascaroside, daumone-2), ascr#3 (asc-ΔC9, C9 ascaroside, daumone-3) and ascr#5 (asc-ωC3, C3 ascaroside), were chemically synthesized according to Butcher et al. (2007; 2008). Before use, pheromone was diluted with dH2O from 3 mM stock solution of pheromone in 100% ethanol.

Preparation of the str-3 repression assay plates

Crude pheromone plates were prepared by spreading 20 μl of diluted crude pheromone onto the assay plates, which were then incubated at 25°C for 3–4 h. The synthetic pheromone plates contained 1 μM ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 ascarosides. Aliquots (50 μg) of live E. coli OP50 or heat-killed E. coli OP50 were then seeded on the plates and dried in a hood overnight or for 3–4 h, respectively, prior to the assay. Well-fed 5–10 adults were placed on the plates and discarded when 60–80 eggs were obtained. The eggs were grown at 25°C until worms developed at each developmental stage.

Quantification of str-3 expression levels

For the GFP quantification of str-3 expression, the worms were anesthetized in 0.5 M or 1 M sodium azide (NaN3) on an agar pad, and the GFP fluorescence was observed with a Zeiss Axio Imager using 40× (for adult stage) and 63× (for L1) objectives and a CCD camera (Hamamatsu). The relative expression level of str-3p::gfp was measured at each developmental stage. The relative GFP levels of str-3 in the ASI sensory neurons were rated from 1 (dim) to 5 (bright) by the naked eye, and these values were confirmed using image J software.

Molecular biology

Genomic regions of the flp-18 gene were amplified by nested PCR and sequenced. The PCR products were then directly injected at a concentration of 10 ng/μl or 50 ng/μl with 50 ng/μl unc-122p::dsRed as a co-injection marker. The outer forward primer was tggatgcgtcaaatgttgtg, the outer reverse primer was gtcagtttgttccagtatccttc, the inner forward primer was ccactccgaaacatacggtac, and the inner reverse primer was cctgacagtcatcacatcacc.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

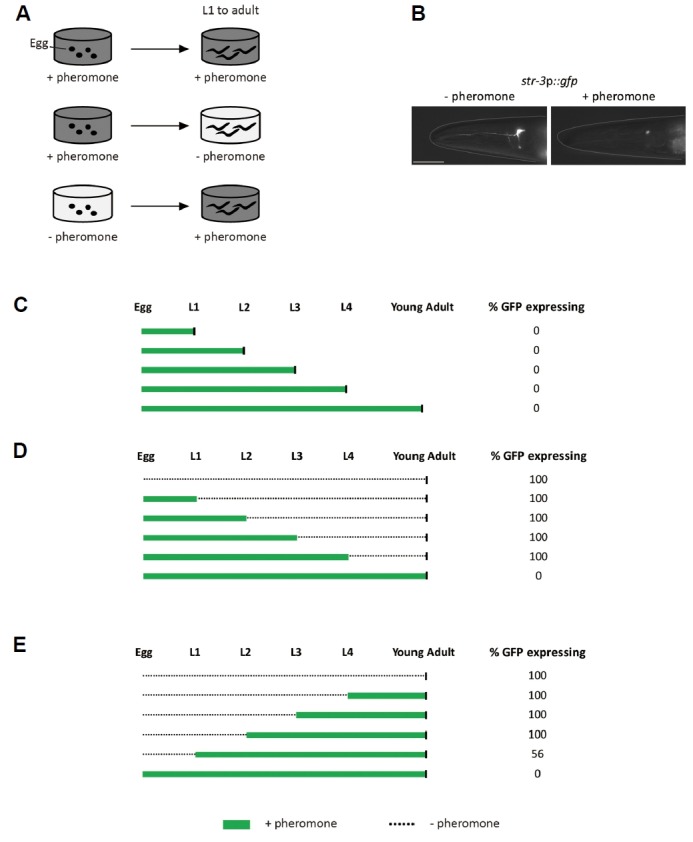

Pheromone-mediated str-3 repression in the ASI chemosensory neurons was imposed from egg to the L1 larval stage

To investigate the effects of dauer pheromones on str-3 repression at the different developmental stages, we first exposed worms expressing the str-3p::gfp transgene to crude pheromone from egg to each developmental stage. We then observed expression of the green fluorescent protein (gfp) in the ASI neurons by imaging of the GFP with a dissection microscope equipped for epifluorescence detection (Fig. 1A). Previously, down-regulated expression of gfp reporter gene under the control of str-3 promoter was validated via quantitative RT-PCR data in which endogenous str-3 message levels were also decreased upon addition of crude pheromone in a dose-dependent manner (Kim et al., 2009). We found that crude pheromone strongly down-regulated str-3p::gfp expression in the ASI neurons when animals were exposed to pheromone from egg to each developmental stage (Figs. 1B and 1C). We next removed the pheromone by transferring str-3p::gfp-repressed worms at each developmental stage onto plates seeded with 50 μg of live E. coli OP50 that did not contain pheromone, and then examined gfp expression as adults (Fig. 1A). str-3p::gfp expression was de-repressed, resulting in str-3p::gfp expression levels that were comparable to those of worms that had not been pre-exposed to pheromone (Fig. 1D). We then tested the critical period for pheromone-mediated str-3 repression by exposing worms to crude pheromone starting from each developmental stage through the young adult stage (Fig. 1A). We found that gfp expression in the ASI neurons was repressed only when the worms were exposed starting from the first L1 stage through the adult stage (Fig. 1E). gfp expression was not fully repressed in animals that were exposed to pheromone after the second L2 stage (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results suggest that str-3 expression can be repressed by pheromone in the developmental window of egg to L1 and de-repressed at any developmental stages.

Fig. 1. str-3 repression upon crude pheromone exposure is imposed from egg to the L1 stage.

(A) Experimental diagram of str-3 repression by crude pheromone exposure at each developmental stage. (B) Fluorescence images of GFP in the ASI neurons of str-3p::gfp transgenic animals taken at the adult stage in the absence or presence of crude pheromone. (C) Relative percentage of str-3p::gfp expression in the ASI neurons of animals at each developmental stage after exposure to crude pheromone during the indicated stages of development. (D–E) Relative percentage of str-3p::gfp expression in the ASI neurons of young adult animals that were exposed to crude pheromone during the indicated stages of development. (C–E) Black vertical bars indicate time of observation. n ≥ 30 for each. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

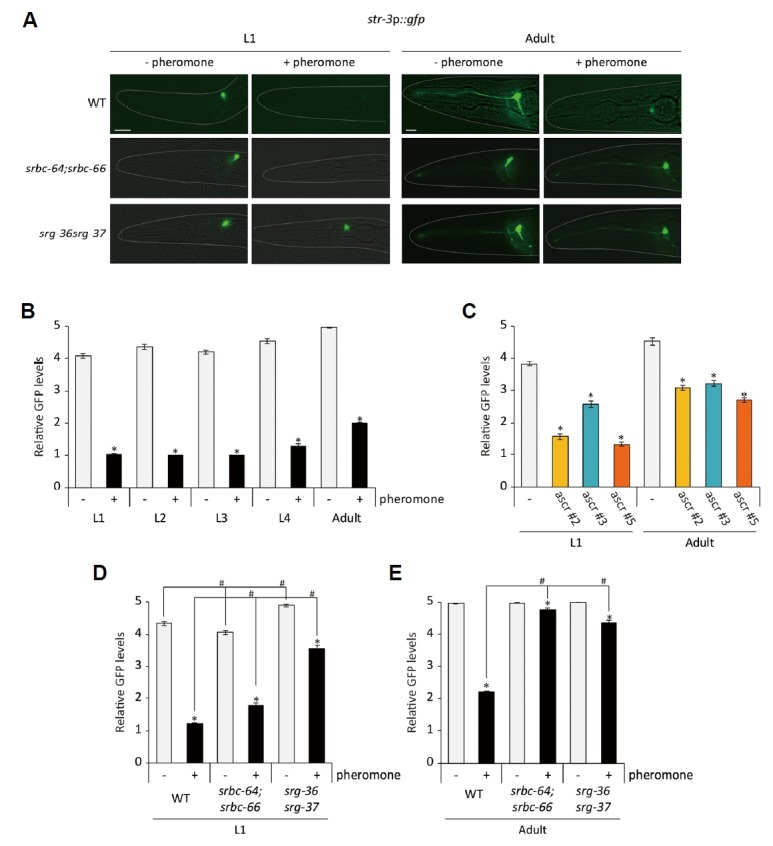

Crude pheromone contains ascaroside pheromone components including ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 (Supplementary Fig. S1)(Butcher et al., 2007; 2008). We previously showed that these chemically synthesized ascaroside pheromone components down-regulated str-3 expression in the ASI neurons when worms were exposed to each of these pheromone components from egg to the adult stage (Kim et al., 2009). We next determined whether these pheromone components could repress str-3p::gfp expression at the different developmental stages. Similar to crude pheromone, mixtures of ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 down-regulated str-3p::gfp expression in the ASI neurons when animals were exposed to pheromone mixtures from egg to the each developmental stage in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 2A and 2B, Supplementary Fig. S2)(Kim et al., 2009). Moreover, similar to crude pheromone, each pheromone component significantly repressed str-3 expression when animals were exposed from egg to the L1 stage or the adult stage (Fig. 2C)(Kim et al., 2009). We noted that the GFP levels in the adults were higher than those in the L1 worms in the presence or absence of pheromone (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that repression of str-3 in the ASI neurons requires early exposure to pheromone components.

Fig. 2. Exposure to ascaroside pheromone components causes str-3 repression via pheromone receptors in L1 larvae and adults.

(A) Representative images of srbc-64;srbc-66 and srg-36 srg-37 double mutants expressing the str-3p::gfp transgene in the ASI neurons at the L1 (left panels) and adult stage (right panels) upon exposure mixtures of 1 μM ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5. (B–C) Relative GFP levels are shown upon exposure to mixtures of 1 μM ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 (B) or individual 1 μM ascarosides (C). (D–E) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression in srbc-64;srbc-66 and srg-36 srg-37 double mutants at the L1 (D) and adult stage (E) upon 1 μM ascaroside pheromone mixtures. n ≥ 30 for each. The scale bar represents 10 μm. Error bars represent the SEM. * and # indicate different from the controls (absence of pheromone and wild-type animals, respectively) at P < 0.001 (Bonferroni t-test).

Mutations in the pheromone receptor genes abolished pheromone-mediated regulation of str-3 gene expression

It was previously shown that the SRBC-64 and SRBC-66 GPCRs and the SRG-36 and SRG-37 GPCRs mediate developmental roles of ascr#2/#3 and ascr#5, respectively (Kim et al., 2009; McGrath et al., 2011). Moreover, mutations in the srbc-64 and srbc-66 genes significantly suppressed pheromone-mediate down-regulation of str-3 expression in the ASI neurons when worms were exposed to 3 μM of each synthetic pheromone component from egg to adults (Kim et al., 2009). We found that mixtures of 1 μM ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 were unable to repress str-3 expression in the ASI neurons of srbc-64 (tm1946);srbc-66 (tm2943) double mutants, and the defects in str-3 repression were more robust in adults than in L1 larvae of srbc-64;srbc-66 double mutants (Figs. 2A, 2D and 2E).

We next examined pheromone-mediated str-3 regulation in srg-36 srg-37 (kyIR88) double mutants. Similar to srbc-64;srbc-66 double mutants, mixtures of 1 μM ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 did not repress str-3 expression in the ASI neurons of srg-36 srg-37 mutants, and these defects were also more robust in adults (Figs. 2A, 2D and 2E). These results support the notion that pheromone signals are transmitted to repress str-3 expression in the ASI neurons via srbc-64, srbc-66, srg-36, and srg-37 pheromone receptors.

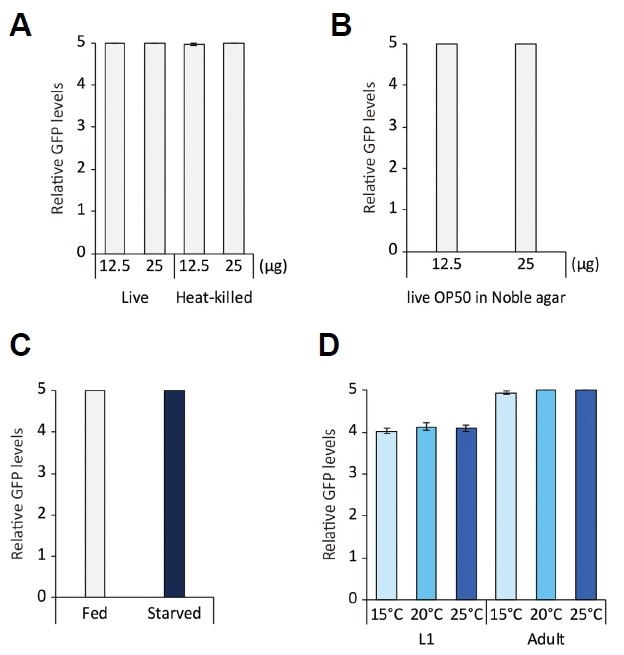

Food availability, internal feeding state, and ambient temperature did not affect str-3 expression

We next sought to further define conditions that affect str-3 expression. We first tested whether food quantity and/or quality could influence str-3 expression. Decreasing the amount of live OP50 from 50 μg to either 25 μg or 12.5 μg did not affect the level of str-3 expression (Fig. 3A). We next incubated str-3p::gfp transgenic worms on plates seeded with heat-killed OP50, which represents low-quality food used in dauer inducing conditions (Jeong et al., 2005). We found that str-3 expression was not affected by exposure to low-quality food (Fig. 3A). Incubation of str-3p::gfp transgenic worms on peptone-free noble agar plates, in which growth of OP50 is limited (Hosono et al., 1989), did not change the level of str-3p::gfp expression (Fig. 3B). These results imply that str-3 expression is not regulated by food availability.

Fig. 3. str-3 expression is not modulated by the quality or the quantity of food or ambient temperature.

(A) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression upon exposure to 12.5 μg or 25 μg live or heat-killed OP50. (B) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression upon exposure to 12.5 μg or 25 μg live OP50 cultivated on noble agar plates. (C) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression after starvation for 24 h. (D) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression following cultivation at 15°C, 20°C, or 25°C at the L1 or adult stage. n≥ 30 for each. Error bars represent the SEM.

To investigate whether str-3 expression is affected by the feeding state, we either fed or starved young adult str-3p::gfp transgenic animals for 24 h. We found that chronic starvation for 24 h did not alter the level of str-3 expression (Fig. 3C), indicating that the internal feeding state does not play a role in str-3 expression.

We next examined whether the cultivation temperature affected str-3 expression by incubating the str-3p::gfp transgenic worms at 15°C, 20°C, and 25°C. These different cultivation temperatures did not affect the level of str-3 expression (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results suggest that str-3 expression is regulated by pheromone exposure but not by changes in the feeding status or the ambient temperature.

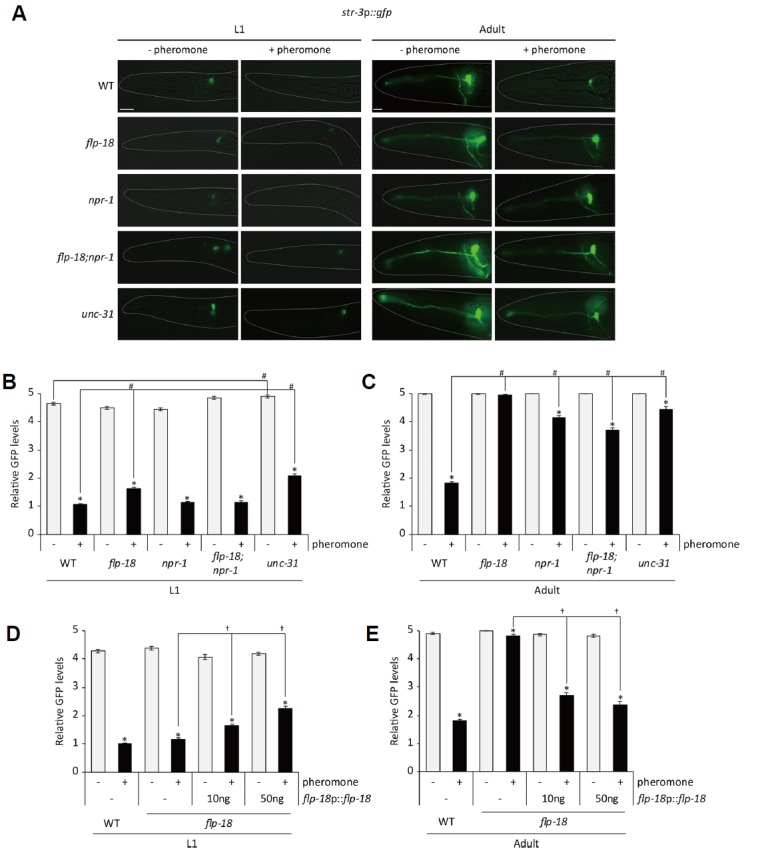

FLP-18 neuropeptide signaling was required for pheromone-mediated regulation of str-3 gene expression via a NPR-1 neuropeptide receptor

We next performed a candidate mutant screen to identify genes required for pheromone-mediated str-3 repression. First, we found that unc-31 mutants exhibited defects in str-3 repression, resulting in str-3p::gfp still being strongly expressed in unc-31 (e169 ) mutants grown on plates containing mixtures of ascr#2, ascr#3, and ascr#5 (Figs. 4A-4C). The defect of unc-31 mutants was severe in adults than in L1 larvae (Figs. 4A-4C). The unc-31 gene encodes a calcium-dependent activator protein (CAPS) that is required for dense-core vesicle exocytosis (Sieburth et al., 2007; Speese et al., 2007). These results suggest that neuropeptide signaling plays a role in pheromone-mediated str-3 repression.

Fig. 4. FLP-18 neuropeptide and NPR-1 neuropeptide receptor are required for pheromone-mediated str-3 repression.

(A) Representative images of flp-18, npr-1, and flp-18;npr-1 mutants expressing the str-3p::gfp transgene in the ASI neurons at the L1 (left two panels) and adult stage (right two panels) upon exposure to mixtures of 1 μM ascaroside pheromone. (B–C) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression in flp-18, npr-1, and flp-18;npr-1 mutants at the L1 (B) and adult stage (C) upon exposure to mixtures of 1 μM ascaroside pheromone. (D–E) Relative GFP levels of str-3p::gfp expression in flp-18 mutants expressing flp-18 genomic DNA driven by its own promoter upon exposure to mixtures of 1 μM ascaroside pheromone. n≥ 30 for each. Error bars represent the SEM. *, #, and † indicate different from the controls (absence of pheromone, wild-type animals, and no transgene, respectively) at P < 0.001 (Bonferroni t -test). The scale bar represents 10 μm.

As it has been reported that a flp-18 FMRFamide neuropeptide gene regulates dauer formation (Cohen et al., 2009), we examined pheromone-mediated str-3 repression in flp-18 (tm2179 ) null mutants. Similar to what we found with unc-31 mutants, pheromone did not repress str-3 expression in adult flp-18 mutants (Figs. 4A-4C). To confirm that defects in flp-18 mutants were caused by loss-of-function mutation of the flp-18 gene, we expressed flp-18 genomic DNA under the control of the flp-18 promoter in a flp-18 mutant background. The expression of flp-18 genomic DNA rescued the defects of adult flp-18 mutants (Figs. 4D and 4E). These results indicate that flp-18 neuropeptide signaling mediates pheromone-mediated str-3 repression.

FLP-18 neuropeptides play various physiological and developmental roles via neuropeptide receptors including NPR-1, NPR-4, and NPR-5 (Cohen et al., 2009; Rogers et al., 2003). We next asked which neuropeptide receptors couple to FLP-18 neuropeptide to mediate pheromone-mediated str-3 repression. We found that str-3 expression was not down-regulated upon pheromone exposure in npr-1 (ad609 ) mutants (Figs. 4A-4C). Although npr-5 mutants exhibited defects in dauer formation (Cohen et al., 2009), str-3 repression was either weakly or not affected in npr-4 (tm1782) or npr-5 (rb1393) mutants (Supplementary Fig. S3). Taken together, FLP-18 mediates str-3 repression at least partially via the NPR-1 neuropeptide receptor but not the NPR-4 and NPR-5 receptors.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we further analyzed conditions in which expression of a chemoreceptor str-3 gene is modulated via pheromone together with FLP-18 neuropeptide signaling. Since srbc-64/66 pheromone receptors act in the ASK chemosensory neurons to detect ascr#2 and ascr#3 (Kim et al., 2009) and str-3 is expressed in the ASI chemosensory neurons, FLP-18 could transmit signals from the ASK to the ASI neurons to regulate str-3 expression. However, flp-18 is not expressed in the ASK and other chemosensory neurons (Rogers et al., 2003), suggesting that FLP-18 play a different role in pheromone-mediated str-3 expression. Since expression of several chemoreceptor genes including str-3 is altered in the presence of pheromone, it is plausible that pheromone could eventually change chemosensory behavior( s) which the chemoreceptors play roles in. We examined attraction behavior to odorants including benzaldehyde and diacetyl (Bargmann et al., 1993) and found that compared to control animals, pheromone-treated animals did not exhibit altered chemotactic behavior to these odorants (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results indicate that chemosensory behaviors are not broadly affected by addition of pheromone but str-3-mediated chemosensory behavior(s) may be modulated in the presence of pheromone. Investigating site of FLP-18 action and identifying str-3 gene function would be the next step to understand this pheromone-mediated gene expression plasticity.

Supplementary data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, P40 OD010440) and the National BioResource Project (Japan) for strains. We also thank Piali Sengupta and K. Kim lab members for helpful comments and discussion on the manuscript. This work was supported by the KBRI Basic Research Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (18-BR-04), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015R1D1A1A 09061430, NRF-2017R1A4A1015534), and DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (18-BD-06) (K.K.), and NIH R01GM118775 (R.A.B).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Bargmann C.I., Hartwieg E., Horvitz H.R. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;74:515–527. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80053-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A.L., Justice N.J., Ngai J. Asynchronous onset of odorant receptor expression in the developing zebrafish olfactory system. Neuron. 1996;16:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher R.A., Fujita M., Schroeder F.C., Clardy J. Small-molecule pheromones that control dauer development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:420–422. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher R.A., Ragains J.R., Kim E., Clardy J. A potent dauer pheromone component in Caenorhabditis elegan that acts synergistically with other components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14288–14292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806676105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassada R.C., Russell R.L. The dauerlarva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1975;46:326–342. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M., Reale V., Olofsson B., Knights A., Evans P., de Bono M. Coordinated regulation of foraging and metabolism in C. elegans by RFamide neuropeptide signaling. Cell Metab. 2009;9:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison A.S. Caenorhabditis elegans pheromones regulate multiple complex behaviors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A.N., Pitts R.J., Robertson H.M., Carlson J.R., Zwiebel L.J. Candidate odorant receptors from the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae and evidence of down-regulation in response to blood feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14693–14697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261432998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden J.W., Riddle D.L. A pheromone influences larval development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1982;218:578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.6896933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden J.W., Riddle D.L. The Caenorhabditis elegans dauer larva: developmental effects of pheromone, food, and temperature. Dev Biol. 1984;102:368–378. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J.S., Brown M., Dobosiewicz M., Ishida I.G., Macosko E.Z., Zhang X., Butcher R.A., Cline D.J., McGrath P.T., Bargmann C.I. Balancing selection shapes density-dependent foraging behaviour. Nature. 2016;539:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner M., Grubbs J., McDonagh A., Valdes D., Winbush A., van der Linden A.M. Cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous regulation of a feeding state-dependent Chemoreceptor gene via MEF-2 and bHLH transcription factors. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner M., Nelson D., Winbush A., Hintz R., Ryu L., Chung S.H., Kim K., Gabel C.V., van der Linden A.M. Feeding state, insulin and NPR-1 modulate chemoreceptor gene expression via integration of sensory and circuit inputs. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh D., Vanderslice R. Temperature-sensitive developmental mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1976;49:220–235. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M., Ryu L., Ow M.C., Kim J., Je A.R., Chinta S., Huh Y.H., Lee K.J., Butcher R.A., Choi H., et al. Early pheromone experience modifies a synaptic activity to influence adult pheromone responses of C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2017;27:3168–3177 e3163. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono R., Nishimoto S., Kuno S. Alterations of life span in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans under monoxenic culture conditions. Exp Gerontol. 1989;24:251–264. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(89)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H., Kim K., Neal S.J., Macosko E., Kim D., Butcher R.A., Zeiger D.M., Bargmann C.I., Sengupta P. Neuromodulatory state and sex specify alternative behaviors through antagonistic synaptic pathways in C. elegans. Neuron. 2012;75:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong P.Y., Jung M., Yim Y.H., Kim H., Park M., Hong E., Lee W., Kim Y.H., Kim K., Paik Y.K. Chemical structure and biological activity of the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer-inducing pheromone. Nature. 2005;433:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature03201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Sato K., Shibuya M., Zeiger D.M., Butcher R.A., Ragains J.R., Clardy J., Touhara K., Sengupta P. Two chemoreceptors mediate developmental effects of dauer pheromone in C. elegans. Science. 2009;326:994–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1176331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig A.H., Schroeder F.C. Ascaroside signaling in C. elegans. WormBook. 2013:1–22. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.155.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath P.T., Xu Y., Ailion M., Garrison J.L., Butcher R.A., Bargmann C.I. Parallel evolution of domesticated Caenorhabditis species targets pheromone receptor genes. Nature. 2011;477:321–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal S.J., Park J., DiTirro D., Yoon J., Shibuya M., Choi W., Schroeder F.C., Butcher R.A., Kim K., Sengupta P. A forward genetic screen for molecules involved in pheromone-induced dauer formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6:1475–1487. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.026450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan K.M., Sarafi-Reinach T.R., Horne J.G., Saffer A.M., Sengupta P. The DAF-7 TGF-beta signaling pathway regulates chemosensory receptor gene expression in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3061–3073. doi: 10.1101/gad.1027702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D., Hahm J.H., Park S., Ha G., Chang G.E., Jeong H., Kim H., Kim S., Cheong E., Paik Y.K. A conserved neuronal DAF-16/FoxO plays an important role in conveying pheromone signals to elicit repulsion behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7260. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckol E.L., Troemel E.R., Bargmann C.I. Sensory experience and sensory activity regulate chemosensory receptor gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11032–11038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckol E.L., Zallen J.A., Yarrow J.C., Bargmann C.I. Sensory activity affects sensory axon development in C. elegans. Development. 1999;126:1891–1902. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H.M., Thomas J.H. The putative chemoreceptor families of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–12. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.66.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C., Reale V., Kim K., Chatwin H., Li C., Evans P., de Bono M. Inhibition of Caenorhabditis elegans social feeding by FMRFamide-related peptide activation of NPR-1. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1178–1185. doi: 10.1038/nn1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D.A., Miller R.M., Lee K., Neal S.J., Fagan K.A., Sengupta P., Portman D.S. Sex, age, and hunger regulate behavioral prioritization through dynamic modulation of chemoreceptor expression. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2509–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S.E., Shim T., Yi J.Y., Kim S.Y., Park S.H., Kim S.W., Ronnett G.V., Moon C. Odorant receptors containing conserved amino acid sequences in transmembrane domain 7 display distinct expression patterns in mammalian tissues. Mol Cells. 2017;40:954–965. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu L., Cheon Y., Huh Y.H., Pyo S., Chinta S., Choi H., Butcher R.A., Kim K. Feeding state regulates pheromone-mediated avoidance behavior via the insulin signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2018;37:e98402. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterlee J.S., Ryu W.S., Sengupta P. The CMK-1 CaMKI and the TAX-4 Cyclic nucleotide-gated channel regulate thermosensory neuron gene expression and function in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2004;14:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P. The belly rules the nose: feeding state-dependent modulation of peripheral chemosensory responses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P., Chou J.H., Bargmann C.I. odr-10 encodes a seven transmembrane domain olfactory receptor required for responses to the odorant diacetyl. Cell. 1996;84:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D., Madison J.M., Kaplan J.M. PKC-1 regulates secretion of neuropeptides. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:49–57. doi: 10.1038/nn1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speese S., Petrie M., Schuske K., Ailion M., Ann K., Iwasaki K., Jorgensen E.M., Martin T.F. UNC-31 (CAPS) is required for dense-core vesicle but not synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6150–6162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1466-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan J., Kaplan F., Ajredini R., Zachariah C., Alborn H.T., Teal P.E., Malik R.U., Edison A.S., Sternberg P.W., Schroeder F.C. A blend of small molecules regulates both mating and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2008;454:1115–1118. doi: 10.1038/nature07168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan J., von Reuss S.H., Bose N., Zaslaver A., Mahanti P., Ho M.C., O’Doherty O.G., Edison A.S., Sternberg P.W., Schroeder F.C. A modular library of small molecule signals regulates social behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo S., Kimura Y., Van Tol H.H. Starvation induces cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression through octopamine-Gq signaling in Caenorhabditis elegan. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10082–10090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0819-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel E.R., Chou J.H., Dwyer N.D., Colbert H.A., Bargmann C.I. Divergent seven transmembrane receptors are candidate chemosensory receptors in C. elegans. Cell. 1995;83:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Wang Y., Zhang X., Bhar S., Jones Lipinski R.A., Han J., Feng L., Butcher R.A. Biosynthetic tailoring of existing ascaroside pheromones alters their biological function in C. elegans. Elife. 2018;7:e233286. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.