Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a pivotal role in immune-tolerance, and loss of Treg function can lead to the development of autoimmunity. Natural Tregs generated in the thymus substantially contribute to the Treg pool in the periphery, where they suppress self-reactive effector T cells (Teff) responses. Recently, we showed that OX40L (TNFSF4) is able to drive selective proliferation of peripheral Tregs independent of canonical antigen presentation (CAP-independent) in the presence of low-dose IL-2. Therefore, we hypothesized that OX40 signaling might be integral to the TCR-independent phase of murine and human thymic Treg (tTreg) development. Development of tTregs is a two-step process: Strong T-cell receptor (TCR) signals in combination with co-signals from the TNFRSF members facilitate tTreg precursor selection, followed by a TCR-independent phase of tTreg development in which their maturation is driven by IL-2. Therefore, we investigated whether OX40 signaling could also play a critical role in the TCR-independent phase of tTreg development. OX40−/− mice had significantly reduced numbers of CD25−Foxp3low tTreg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ mature tTregs, while OX40L treatment of WT mice induced significant proliferation of these cell subsets. Relative to tTeff cells, OX40 was expressed at higher levels in both murine and human tTreg precursors and mature tTregs. In ex vivo cultures, OX40L increased tTreg maturation and induced CAP-independent proliferation of both murine and human tTregs, which was mediated through the activation of AKT-mTOR signaling. These novel findings show an evolutionarily conserved role for OX40 signaling in tTreg development and proliferation, and might enable the development of novel strategies to increase Tregs and suppress autoimmunity.

Keywords: Thymic Tregs, OX40L, IL-2, Treg proliferation, maturation

Introduction

CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a pivotal role in suppressing autoimmune responses mediated by self-reactive effector T cells (Teff) and thereby help maintain self-tolerance.1 Foxp3-deficient mice develop severe autoimmunity and lethal immunopathology.2 Similarly, mutations in the human FOXP3 gene are associated with fatal immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome.2,3 Natural Tregs (nTregs) are generated in the thymus. Although induced Tregs (iTregs) can be generated in the periphery from CD4+CD25−Foxp3− conventional (Tconv) T cells, nTregs emigrating from the thymus represent the major proportion of the peripheral Treg pool.4 According to the TCR-instructive model, most of the thymocytes expressing high-affinity TCRs for self-antigens are deleted through negative selection in the thymus.5 However, several of the self-reactive thymocytes can escape negative selection and migrate to the periphery and contribute to autoimmunity. On the other hand, thymocytes expressing TCRs with intermediate affinity for self-antigens can differentiate into CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs and migrate to the periphery, where they suppress the function of self-reactive Teff cells and help maintain self-tolerance.5 Thymic Tregs (tTregs) express self-antigen-specific TCRs; therefore, lack of expression of cognate antigens in the thymus can prevent their positive selection in the thymus and thus result in the loss of peripheral tolerance. For example, a lack of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein expression leads to impaired development of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific tTregs in the thymus and accelerated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.6 Thus, tTregs play an essential role in maintaining immune homeostasis and suppressing autoimmunity.

Development of tTregs occurs in two distinct phases: (i) a TCR-dependent phase where thymocytes expressing intermediate-affinity TCRs for self-peptides differentiate into CD4+CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors; and (ii) a TCR-independent phase in which Foxp3 expression is induced in these Treg precursors via STAT5 activation by common γ-chain (γc) cytokines, predominantly IL-2 and, to a lesser extent, IL-15 and IL-7.7 Alternatively, CD4+CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors can give rise to CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs, which are also regulated by common γc cytokines.8 A salient feature of CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs is that they both express higher levels of GITR (TNFRSF18), OX40 (TNFRSF4) and TNFRII (TNFRSF1b) compared to CD4+CD25−Foxp3− conventional (Tconv) T cells. Their cognate ligands, GITRL, OX40L and TNF-α, are expressed on thymic DCs and medullary thymic epithelial cells (TECs). The coupling of co-signaling driven by these ligands upon interaction with their cognate receptors with TCR-signals drives thymocyte differentiation into tTregs. In addition, these interactions can also promote IL-2-induced maturation of CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors into CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in the TCR-independent phase of thymic Treg differentiation.9 However, whether these ligands have a similar effect on the maturation of CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors remains unknown. Moreover, emerging studies suggest that, in addition to thymic differentiation, proliferation may also contribute significantly to tTreg numbers.10,11 However, the underlying mechanism of this tTreg expansion is poorly understood.

Unlike tTreg development and their role in maintaining self-tolerance in mice, which are well understood, there is a paucity of data concerning human tTreg development.12,13 This gap in knowledge regarding human Treg development has impeded our ability to develop effective strategies to rectify Treg deficiency as a means to ameliorate autoimmune diseases. Murine tTreg differentiation mainly starts during the CD4+ single-positive (SP) stage,7 whereas human tTreg differentiation occurs at an earlier CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) stage.14 However, both murine and human tTreg development is regulated by the common γc-cytokines IL-2 and IL-15, suggesting the existence of a common differentiation pathway.13,15

Previously, we have shown that OX40 signaling can induce selective proliferation of peripheral Foxp3+ Tregs, but not Foxp3− Tconv cells, in an IL-2-dependent manner. Furthermore, using MHC class-II−/− mice, we have demonstrated that this selective Treg proliferation is independent of canonical antigen presentation (CAP-independent) but requires IL-2.16,17,18 Therefore, we hypothesized that OX40-mediated signaling might regulate both murine and human thymic Treg generation primarily by inducing their proliferation during the TCR-independent phase of their development. To our surprise, not only did we find that OX40-mediated signaling could induce the CAP-independent proliferation of tTreg precursors and mature tTregs, but it could also drive maturation of tTreg-precursors. We found that AKT-mTOR activation was the key cell signaling mechanism driving CAP-independent tTreg proliferation, which was conserved between murine and human thymi, revealing an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of Treg development and homeostasis. These findings could have significant clinical implications, as they may aid in the development of novel therapies for autoimmune diseases.

Materials and methods

Animals and human tissue specimens

C57BL/6 J (Stock # 000664), OX40−/− (Stock # 012838) and Foxp3.eGFP mice (Stock # 018628) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Breeding colonies were established and maintained in a pathogen-free facility in the biological resources laboratory of the University of Illinois at Chicago (Chicago, IL). All animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Normal pediatric thymic tissues (n=10) were obtained through the Cooperative Human Tissue Network in Ohio in accordance with the policies stated by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board. Cooperative Human Tissue Network is funded by the National Cancer Institute, and other investigators may have received specimens from the same subjects.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-mouse CD25 (Clone # PC61.5), anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5), anti-mouse CD8a (53.6.7), anti-mouse/rat Foxp3 (FJK16S), anti-mouse CD134/OX40 (OX86), anti-human/mouse (S473) pAKT (SDRNR), anti-human/mouse pmTOR (MRRBY), anti-human CD4 (RTA-T4), anti-human CD8a (SK1), anti-human FOXP3− (236 A/E7 and PCH101), anti-human CD25 (BC96), anti-human CD134/OX40 (ACT35), anti-human CD11c (3.9), anti-human-CD123 (6H6), anti-human BDCA2 (201 A) and appropriate isotype control antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific. Anti-Bcl2 (BCL/10C4), anti-human/mouse Ki67 (11F6), anti-human CD13 (WM15) and anti-human OX40L (11C3.1) were purchased from Biolegend. CD4+/CD4+CD25+ EasySep T-cell isolation kits were from StemCell Technologies. Mouse recombinant OX40L-Fc was provided by Dr. Alan L Epstein (Keck School of Medicine, LA). Human recombinant OX40L-Fc was from Sino Biologicals. T cells were cultured in PRIME-XV® T Cell Expansion XSFM medium (Irvine Scientific). PD-98059 (MEK), Tyrphostin46 (EGFRK), LY 294002 (PI3K), BML-257 (AKT) and Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors were purchased from Enzo life sciences. Mouse anti-CD3 (Clone # 2C11) and anti-CD28 (Clone # PV10) were purchased from Bioxcell. Human and mouse recombinant IL-2, TGF-β and cell stimulation cocktail were purchased from eBioscience, Thermo Fisher.

Isolation of T-cell subsets, proliferation and suppression assays

Thymi from 6 to 8-week-old mice were excised, single-cell suspensions were prepared and CD4+/CD4+CD25−/CD4+CD25+ T cells were isolated according to the manufacturer’s (StemCell Technologies) protocol. Isolated cells were stained with Cell-Trace Violet (Life technologies) and treated with IL-2 (25 U/ml) and recombinant OX40L-Fc (5 μg/ml) for the indicated durations. Suppression assays were performed by co-culturing anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated CD4+CD25− (Teff) and CD4+CD25+ (Treg) cells at various ratios, that is, 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4 and 1:8, for 3 days. The extent of suppression was calculated using the percentages of proliferating Teff cells in the absence (no Treg control) or presence of Tregs as previously described.16 For kinase inhibitor assays, cells were pre-treated with indicated inhibitors for 2 h and then co-treated with IL-2 alone or OX40L+IL-2. Similarly, single-cell suspensions of human thymi were prepared and stained with Cell Trace Violet before treatment.

Thymic organ culture and thymic epithelial cell isolation

Human thymi were dissected into ~2 mm3 fragments and cultured over Matrigel (Corning) in 24-well transwell plates with PRIME-XV® T Cell Expansion XSFM medium in the presence of IL-2 or human OX40L-Fc+IL-2 as described previously.19 Human TECs were prepared by Liberase-TH (Roche life sciences) digestion, as described previously.20

Flow cytometry and FACS analysis

CD4+CD8−CD25+Foxp3−, CD4+CD8−CD25−Foxp3low and CD4+CD8−CD25+Foxp3+ constitute <1% of total thymocytes. Therefore, CD4SP thymocytes were purified using an EasySep mouse CD4+ T-cell isolation kit to enrich these populations. Cells were washed with PBS containing 0.5% BSA, surface-stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8a and anti-CD25, and the desired subsets of cells were sorted using a MoFlo Astrios cell sorter (Beckman and Coulter). Sorting purity was greater than 95%, as confirmed by post-sorting analysis. For flow cytometry analysis, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with appropriate isotype controls and test antibodies in the dark at 4 °C. Samples were analyzed using a CyAn ADP Analyzer (Beckman and Coulter) and LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using Summit v4.3 software (Beckman and Coulter).

Treg maturation and adoptive conversion assays

For IL-2-dependent Treg maturation assay, CD4+CD8−CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors were sorted from thymi of Foxp3.eGFP mice and cultured in PRIME-XV® T Cell Expansion XSFM medium with IL-2 (25 U/ml) and OX40L-Fc (5 μg/ml) for 0–5 days. For CD25−Foxp3low conversion assays, CD4+CD8−CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors were sorted and cultured as described above. For TGF-β-dependent adoptive Treg conversion assays, CD4+CD8−CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells were sorted from Foxp3.eGFP mice thymi and cultured in PRIME-XV® T Cell Expansion XSFM medium containing anti-CD3/anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (5 μg/ml each), recombinant mouse TGF-β (5 ng/ml) and IL-2 (50 U/ml) with or without OX40L (5 μg/ml) for 4 days.

Cell stimulation and IL-2 mRNA expression analysis

Total thymocytes from C57BL6-WT and OX40−/− mice were stimulated with a cell stimulation cocktail containing PMA and ionomycin overnight. Total RNA was isolated, and IL-2 mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR as described previously.16

Animal experiments

Six to 8-week-old female C57BL6/J mice were injected (i.p) with either PBS or recombinant OX40L (100 μg) once a week for 3 consecutive weeks. Animals were killed a week after the final injection, and organs (e.g., spleen, thymus and lymph nodes) were collected. Single-cell suspensions were prepared, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism GraphPad (V6.0). Data are expressed as the means±SEM of multiple experiments. Student’s t-tests were used to compare two groups, whereas ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used to compare more than two groups. A p-value<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

OX40 expression correlates with early stages of murine and human Foxp3+ thymocyte differentiation

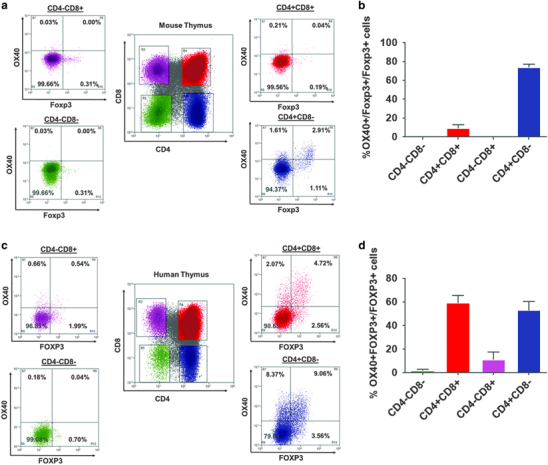

Murine and human tTreg development have distinct characteristics. Unlike murine CD4+Foxp3+ thymocytes, which predominantly appear during later CD4/CD8 SP stages, human CD4+FOXP3+ thymocytes appear at an earlier CD4+CD8+ DP stage.14 Furthermore, though it is known that OX40 signaling can regulate murine tTreg differentiation,9 its role in human tTreg differentiation is unknown. Therefore, we analyzed CD4−CD8− (DN), CD4+CD8+ (DP), CD4+CD8− SP and CD4−CD8+ SP human and murine thymocytes for Foxp3 and OX40 expression. As shown in Figures 1a and b, murine Foxp3+ thymocyte differentiation started predominantly during the CD4+ SP stage. Interestingly, OX40 expression was confined predominantly to the CD4+ SP thymocyte subset, and a major proportion of Foxp3+ thymocytes (73.92±6.36%) expressed OX40. Consistent with previous reports, we found human FOXP3+ thymocyte differentiation started at an earlier CD4+CD8+ DP stage and continued into CD4+ and CD8+ SP stages, which was different from murine tTreg development (Figures 1c and d). Intriguingly, we also observed OX40 expression in an earlier stage of CD4+CD8+DP human thymocytes, particularly in a major proportion of FOXP3+ thymocytes (60.31±6.24%). Frequencies of OX40+Foxp3+ thymocytes in different subsets of murine and human thymocytes are shown in Figures 1b and d, respectively. These results showed a strong correlation between OX40 expression and Foxp3+ thymocyte differentiation in both murine and human thymi, which suggested a role for OX40 signaling in tTreg development.

Figure 1.

OX40 expression correlates with early stages of Foxp3+ thymocyte development in murine and human thymi. (a) Six to 8-week-old C57BL6 female thymic CD4−CD8− DN (green), CD4+CD8+ DP (red), CD8+CD4− SP (pink) and CD8−CD4+ (blue) subsets were analyzed to enumerate OX40+Foxp3+ thymocytes. (b) Bar graph summarizing the results of a (values represent means±SEM, n=6). (c) Three week to 24-month-old pediatric human thymi were analyzed to enumerate OX40+FOXP3+ thymocytes as described in A. (d) Bar graph showing the percentages of OX40+Foxp3+cells within Foxp3+ cells (summarized from c). Values represent means±SEM, n=6. DP, double positive.

Loss of OX40 signaling significantly affects tTreg precursor and mature tTreg numbers

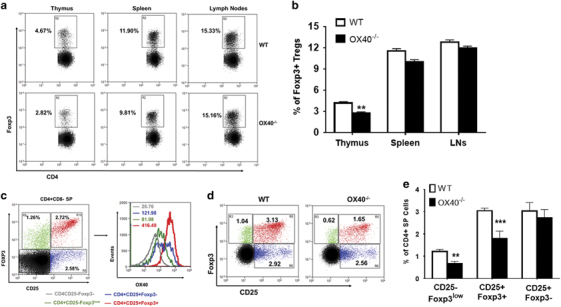

We investigated whether OX40 signaling was required for tTreg development using OX40−/− mice. We observed a significant reduction in Foxp3+ tTregs specifically in the thymus of OX40−/− mice compared to WT mice (4.10±0.18% vs 2.70%±0.17%). However, the differences in peripheral Tregs were not as significant (Figures 2a and b). The reduction observed in tTregs in OX40−/− mice relative to WT mice could result from the following possibilities: (1) a decrease in CD4+ SP thymocyte differentiation, which in turn can affect tTregs; (2) reduced generation of tTreg precursors; (3) reduction in the conversion of tTreg precursors into mature CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs; or (4) changes in the survival/proliferation of Treg precursors/mature Tregs. Therefore, we sought to determine which of these possibilities was responsible for the observed differences. We found no significant difference in the frequencies of CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes between WT and OX40−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S1A-B) implying that the reduced number of tTregs observed in OX40−/− mice is not due to a proportionate reduction in CD4+ SP or CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes. Next, we analyzed OX40 expression in the CD4+CD25+Foxp3− and CD4+CD25−Foxp3low subsets of tTreg precursors and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs, and observed the highest levels of OX40 expression in mature Tregs, followed by CD25+Foxp3−, CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells (Figure 2c). Furthermore, we compared the frequencies of these subsets between WT and OX40−/− mice. As shown in Figures 2d and e, we found a significant reduction in mature CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs (3.03%±0.06% vs 1.80%±0.19%) and CD25−Foxp3low tTreg precursors (1.21%±0.05% vs 0.66%±0.08%), but not in the CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors in OX40−/− mice relative to WT mice.

Figure 2.

Effects of the loss OX40 signaling on murine thymic Treg development. (a) Thymi from age- and sex-matched 6–8-week-old WT (top) and OX40−/− (bottom) mice were analyzed for Foxp3+ thymocytes within CD8−CD4+SP subsets. Numbers represent percentages of Foxp3+ thymocytes within CD8−CD4+SP subsets. (b) Bar graph summarizing results of (a) (values represent means±SEM, n=6, **p<0.01 vs WT). (c) CD8−CD4+SP thymocytes were gated from total thymocytes and OX40 expression was determined in CD4+CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells (gray), CD4+CD25−Foxp3low (green) and CD4+CD25+Foxp3− (blue) Treg precursors and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs (red), analyzed by histogram overlay. Numbers in histograms represent corresponding MFI values of OX40 expression. (d) Comparative analysis of CD4+CD25−Foxp3low (green), CD4+CD25+Foxp3− (blue) Treg precursors and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ (red) mature Treg frequencies between age- and sex-matched WT vs OX40−/− mice. (e) Bar graph summarizing results shown in d (values represent means±SEM, n=6, ***p<0.005, **p<0.01 vs WT). Treg, regulatory T cells.

OX40L treatment significantly increases proliferation of tTreg precursors and mature tTregs

Next, we determined the effect of OX40L treatment on tTreg precursors and mature tTregs. Treatment of WT mice with recombinant OX40L-Fc significantly increased Treg numbers in the thymus (3.01%±0.38% vs 6.40%±0.37%), spleen (13.62%±0.38% vs 26.89%±1.90%) and peripheral lymph nodes (12.52%±0.90% vs 25.16%±1.10%) (Figures 3a and b). We did not observe a significant increase in the frequencies of CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes upon OX40L treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1C-D). However, we did find a significant increase in mature CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs (2.32%±0.10% vs 3.80%±0.31%) and CD25−Foxp3low (1.56%±0.07% vs 3.19%±0.18%) tTreg precursors, but not in the CD25+Foxp3− tTreg precursors (Figures 3c and d), upon OX40L treatment. Thus, the increased tTregs observed in OX40L-treated mice could be due to an either increased survival/proliferation of CD25−Foxp3low tTreg precursors and mature Tregs or an increased conversion of tTreg precursors into mature Tregs. We had previously shown that OX40L can induce CAP-independent proliferation of peripheral Tregs.21 Therefore, using proliferation marker Ki67 expression, we analyzed whether OX40L treatment could induce proliferation of CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ tTregs in vivo. As shown in Figure 3e, we observed significantly higher frequencies of Ki67+ cells within CD25−Foxp3low precursors (19.56%±2.10% vs 29.04%±2.07%) and CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs (11.47%±1.44% vs 23.43%±1.86%) of OX40L-treated mice compared to control mice. Furthermore, OX40L-expanded Tregs retained the expression of suppressive markers, such as CTLA4, CD39, Helios and GITR (Figure 3f), and function (Figure 3g) when compared to control Tregs. These findings are consistent with our previous observations in peripheral Tregs.21

Figure 3.

OX40L increases CD4+CD25-Foxp3low and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ thymocyte proliferation in vivo. (a) Six-week-old female C57BL6 mice were administered PBS or soluble OX40L-Fc (100 μg) once a week for 3 consecutive weeks, and percentages of Foxp3+ thymocytes were analyzed as described for a. (b) Bar graph summarizing results of a (values represent means±SEM, n=6, ***p<0.005, **p<0.01 vs PBS). (c) Comparative analysis of CD4+CD25−Foxp3low (green), CD4+CD25+Foxp3− (blue) Treg precursor and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Treg (red) frequencies between age- and sex-matched PBS- vs OX40L-treated mice. (d) Bar graph summarizing results shown in c (values represent means±SEM, n=8, ***p<0.005, *p<0.05 Vs PBS). (e) Bar graph showing percentages of Ki67+CD25−Foxp3low and Ki67+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in PBS- (blue) vs OX40L (red)-treated mice (values represent means±SEM, n=8, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 vs PBS). (f) Histogram overlays showing CTLA4, CD39, Helios and GITR expression in mature Tregs between PBS- (blue) vs OX40L (red)-treated mice. f) CD4+ CD25− Teff cells and CD4+CD25+ Tregs were sorted from control and OX40L-treated thymocytes. Tregs were co-cultured with control Teff cells at the indicated Teff:Treg ratios, that is, 8:1, 4:1, 2:1, 1:1 and 1:0, for 3 days. Teff cell proliferation analyzed by Cell Trace Violet dilution. Suppression was calculated using proliferating Teff cell ratios between no Treg control vs various co-cultures (n=3). Teff, effector T cells; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Previously, CD25−Foxp3+ precursors were identified as a short-lived population in the thymus undergoing apoptosis in the absence of signaling by yc-cytokines (predominantly IL-2), which are available only in a limited quantity sufficient to support a finite number of cells.8 We stimulated thymocytes from WT and OX40−/− mice to determine whether OX40 signaling is critical for IL-2 expression. We found a significantly lower level of IL-2 mRNA expression in OX40−/− thymocytes compared to WT thymocytes. This observation was complemented by our observation of increased IL-2 mRNA expression in WT thymocytes upon OX40L treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, we found reduced expression of the pro-survival factor Bcl2 in OX40L-treated CD25−Foxp3low precursors (MFI: 52.55±3.55 vs 37.81±1.56) (Supplementary Fig. S3A-B) and to a lesser but nonsignificant extent in CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. Since Bcl2 can induce cell cycle arrest, reduced Bcl2 expression could support cell proliferation,22,23 which correlated with increased Ki67+ cells in these subsets of cells. Taken together, these results suggested that OX40 signaling can regulate tTreg generation by inducing the proliferation of both CD25−Foxp3low tTreg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ mature tTregs.

OX40L co-stimulation increases TCR-independent tTreg maturation and proliferation in an IL-2-dependent manner

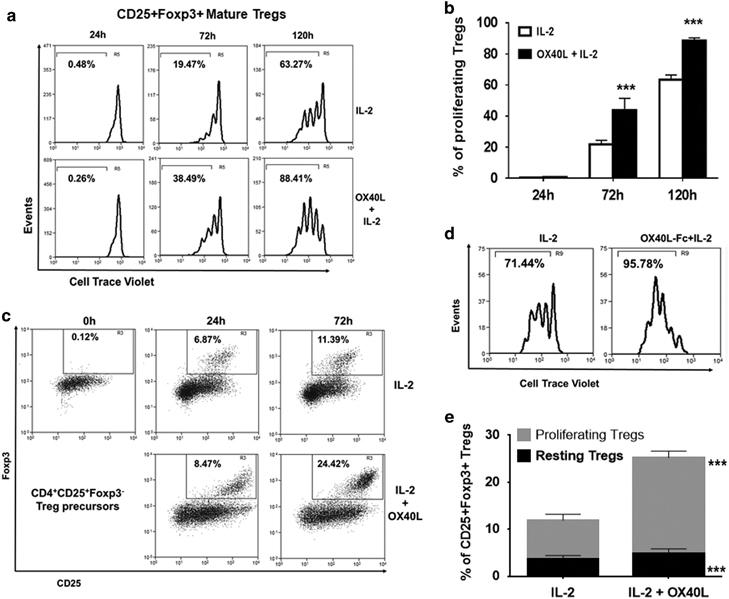

Next, we sought to investigate the effects of OX40 stimulation on tTreg maturation and proliferation. We treated CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature tTregs from Foxp3.eGFP mice with IL-2 or IL-2+OX40L (without antigenic stimulation) for different time intervals and analyzed the cell proliferation. As shown in Figures 4a and b, IL-2-induced tTreg proliferation in a time-dependent manner, which was further significantly increased by OX40L co-stimulation. An earlier report had shown a synergistic role for OX40L in the IL-2-induced conversion of CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors into mature CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs at 72 h.9 However, we observed that OX40L significantly increased the proliferation of mature Tregs at 72 h (Figures 4a and b). Therefore, we sorted CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors and cultured them in the presence of IL-2 with/without OX40L for 0–72 h and analyzed the Treg maturation and proliferation. We found an IL-2-dependent conversion of CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors into CD25+Foxp3+ tTregs occurred by 24 h, which was further enhanced by OX40L co-stimulation (Figure 4c). In addition, we found a significant increase in the proportion of proliferating tTregs upon OX40L treatment compared to IL-2 treatment alone at 72 h (71.44% vs 95.78%) (Figures 4d and e). Thus, OX40L-IL-2 co-signaling increased both tTreg maturation and proliferation.

Figure 4.

Effects of OX40L treatment on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs and CD4+CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors ex vivo. (a) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs sorted from Foxp3.eGFP murine CD4+SP thymocytes were treated with IL-2 (25 U/ml) alone (top) and IL-2+ OX40L-Fc (5 μg/ml) for 0–120 h. Cell proliferation was measured by Cell Trace Violet dilution. Numbers represent percentages of proliferating Tregs at indicated time intervals. (b) Bar graph summarizing results shown in a (values represent means±SEM, n=3, ***p<0.005 vs IL-2). (c) CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors sorted from Foxp3.eGFP murine CD4+SP thymocytes were labelled with Cell Trace Violet and cultured with IL-2 (top panel) or IL-2+OX40L (bottom panel) for 0–72 h, as described for a. Dot plots showing percentages of mature CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs converted from CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors. (d) Mature CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs were gated, and cell proliferation was measured by Cell Trace Violet dilution. Histograms show percentages of proliferating Tregs within converted CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. (e) Bar graph showing percentages of resting (black) and proliferating (gray) CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in culture (values represent means±SEM, n=3, ***p<0.005 vs IL-2). Treg, regulatory T cells.

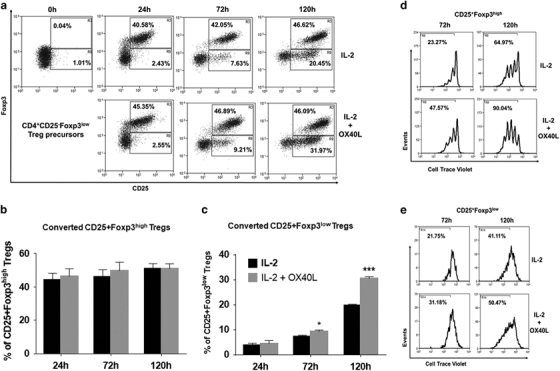

CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors have lower Foxp3 expression compared to CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs and represent an immature subset undergoing the Treg developmental program.24 We determined the effects of OX40L on the conversion of CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and found that they could readily become mature CD25+Foxp3high Tregs upon IL-2 treatment at 24 h (Figure 5a). However, addition of OX40L did not significantly increase the maturation of CD25−Foxp3low subsets (Figures 5a and b). There was a time-dependent increase in the differentiation of CD25−Foxp3low precursors into CD25+Foxp3low Tregs from 24 to 120 h in IL-2-treated cultures, which was significantly increased upon addition of OX40L (19.92%±0.37% vs 31.65%±0.66%) (Figures 5a and c). This increase in the CD25+Foxp3low population was unlikely to be due to the loss of Foxp3 expression from CD25+Foxp3high Tregs because the frequency of CD25+Foxp3high cells remained unaltered from 24 to 120 h (Figures 5a and c). In addition, proliferation assays revealed an additive effect of OX40L co-stimulation in increasing the proliferation of both CD25+Foxp3high and CD25+Foxp3low (to a lesser extent) Tregs compared to cells treated with IL-2 alone (Figures 5d and e). Collectively, these results suggested that OX40L co-stimulation could enhance the conversion of CD25−Foxp3low precursors into CD25+Foxp3low Tregs while also increasing the proliferation of both CD25+Foxp3high and CD25+Foxp3low Tregs. These results suggested the maturation and proliferation of tTregs as underlying mechanisms by which OX40 signaling can regulate tTreg generation.

Figure 5.

Effects of OX40L treatment on CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors. (a) CD25-Foxp3low Treg precursors sorted from Foxp3.eGFP murine CD4+SP thymocytes were labelled with Cell Trace Violet and cultured with IL-2 (top panel) or IL-2+OX40L (bottom panel) for 0–120 h, as described for a. Numbers within dot plots represent percentages of CD25+Foxp3high (Upper gate) and CD25+Foxp3low (lower gate) Tregs differentiated from CD25−Foxp3low precursors. (b) Bar graph showing the percentages of CD25+Foxp3high Tregs in IL-2- (black) and OX40L+IL-2 (gray)-treated cultures (c) Bar graph showing the percentages of CD25+Foxp3low Tregs in IL-2- (black) and OX40L+IL-2 (gray)-treated cultures (values represent means±SEM, n=3, *p<0.05, ***p<0.005 vs IL-2). (d) Histogram showing the percentages of proliferating cells within CD25+Foxp3high Tregs in IL-2- (top) vs IL-2+OX40L (bottom)-treated cultures at 72 h and 120 h. (e) Histogram showing the percentages of proliferating cells within CD25+Foxp3low Tregs in IL-2- (top) vs IL-2+OX40L (bottom)-treated cultures at 72 h and 120 h. Treg, regulatory T cells.

Though TGF-β-mediated adoptive conversion of CD4+CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells to iTregs mainly takes place in the periphery, several studies have suggested a role for TGF-β in tTreg generation.25,26 Therefore, we examined the effects of OX40 signaling on this process. We sorted thymic Tconv cells and stimulated them with anti-CD3/CD28/TGF-β with or without OX40L for 4 days in the presence of IL-2. Unlike the effects of OX40L on nTregs, which increased their proliferation, we found a significant reduction in iTreg generation upon OX40L treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4A-B).

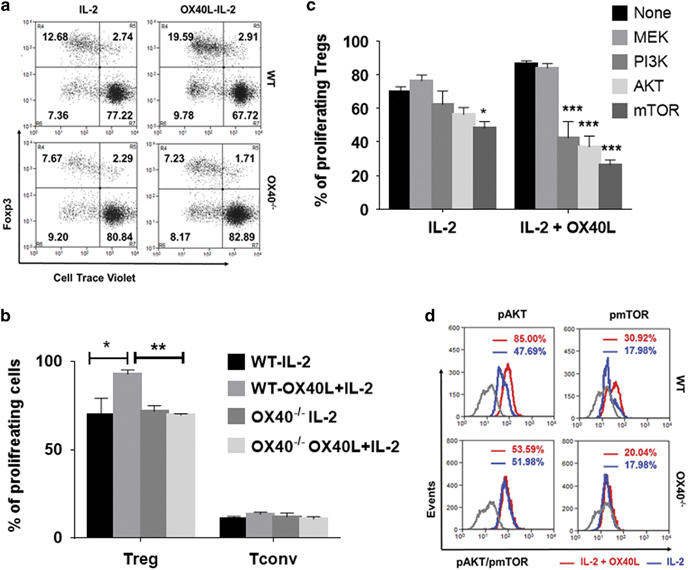

AKT-mTOR signaling is involved in OX40L-IL-2-induced CAP-independent tTreg proliferation

Next, we examined the effects of the loss of OX40 signaling in tTreg proliferation using OX40−/− mice. CD4+SP T cells from WT and OX40−/− mice were treated with IL-2 or OX40L+IL-2 for 5 days. Interestingly, we found similar basal proliferation rates of Tregs from either WT or OX40−/− mice in the presence of IL-2. However, OX40L+IL-2 co-signaling induced the selective proliferation of WT Foxp3+ Tregs but not Foxp3− Tconv cells. In addition, our results showed a significantly increased proliferation of CD4+Foxp3+Tregs from WT mice relative to those from OX40−/− mice (Figures 6a and b). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S5A-B, although IL-2 exerted a dose-dependent effect on the proliferation of tTregs from WT mice, OX40L induced a stronger proliferation rate even at lower doses of IL-2 (Supplementary Fig. S5A and B). In addition, OX40L also showed a dose-dependent effect in the presence of a constant low dose of IL-2 (25 U/ml) (Supplementary Fig. S5C and D).

Figure 6.

OX40 co-stimulation increases AKT-mTOR signaling to drive tTreg proliferation. (a) WT (top) and OX40−/− (bottom) CD8-CD4+SP thymocytes were treated with (right) or without (left) OX40L-Fc in the presence of IL-2 for 5 days. Numbers in the representative dot plots indicate percentages of resting (top right) vs proliferating (top left) CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs and resting (bottom right) vs proliferating (bottom left) CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells. (b) Bar graph showing the percentages of proliferating Tregs and Tconv cells (values represent means±SEM, n=6, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (c) Thymic CD4 SP cells were pre-treated with the indicated pharmacological kinase inhibitors (10 μM/ml) for 2 h and co-treated with IL-2 or OX40L+IL-2 for 5 days without any antigenic stimulation. Bar graph showing the percentages of proliferating Tregs in each of the culture conditions (values represent means±SEM, n=3, *p<0.05, ***p<0.005 vs No inhibitor control. (d) Histogram overlays showing MFI values of phospho-AKT and phospho-mTOR in Tregs expanded using IL-2 alone (blue) or IL-2+OX40L (red) in WT (top) vs OX40−/− (bottom) thymic CD4+ SP cells. Gray lines represent appropriate isotype controls. Treg, regulatory T cells

Next, we explored the cell signaling pathways involved in the OX40L-IL-2-induced CAP-independent proliferation of tTregs. Using a library of pharmacological kinase inhibitors, we screened for the kinase inhibitors that could block tTreg proliferation without significantly affecting tTreg survival (data not shown). As shown in Figure 6c, inhibitors of PI3K (86.76%±0.88% vs 42.56%±5.56%), AKT (88.76%±0.88% vs 37.69%±3.09%) and mTOR (86.76%±0.88% vs 26.40%±1.65%) signaling pathways significantly blocked OX40L-IL-2-induced tTreg proliferation, while MEK inhibitor treatment had no discernible effect (86.76%±0.88% vs 84.01%±2.64%) on tTreg proliferation. Moreover, IL-2-induced tTreg proliferation was not significantly blocked by MEK (65.58%±1.67% vs 72.36%±3.42%), PI3K (65.58%±1.67% vs 62.26%±4.62%) or AKT inhibitors (65.58%±1.67% vs 56.35%±2.38%), although mTOR inhibitor (65.58%±1.67% vs 50.22%±2.24%) treatment exerted a significant inhibitory effect. However, the mTOR inhibitory effect was much greater in cells co-treated with IL-2+OX40L relative to cells treated with IL-2 alone. To further clarify these findings, we analyzed the effects of IL-2 and OX40L on the activation of AKT and mTOR signaling pathways using CD4+SP thymocytes from WT and OX40−/− mice. We observed increased levels of phospho AKT and phospho mTOR in OX40L+IL-2-treated WT tTregs compared to cells treated with IL-2 alone; these results correlated well with the kinase inhibitor results (Figure 6d). Although the basal levels of these phosphoproteins remained unaltered in OX40−/− tTregs, as expected, we observed no significant increase in the activation of AKT and mTOR in OX40−/− tTregs upon OX40L treatment (Figure 6d). Collectively, these results suggested that increased activation of AKT-mTOR signaling is required for CAP-independent tTreg proliferation driven by OX40L+IL-2 co-signaling.

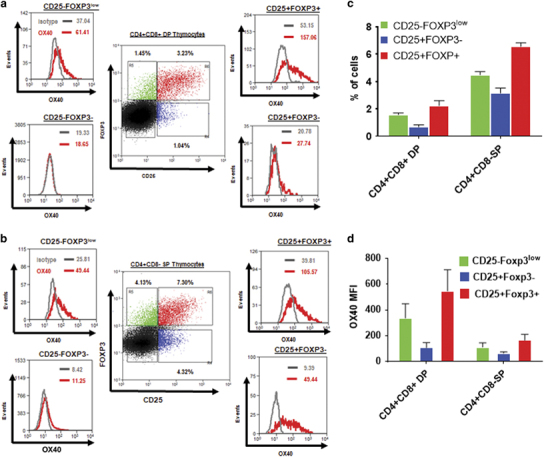

Human Treg precursors and mature Tregs preferentially express OX40 over Tconv cells, and the cognate ligand OX40L is expressed by thymic epithelial cells and plasmacytoid DCs

Next, we determined whether human tTreg differentiation occurred exclusively at the CD4+CD8+ DP stage or at both DP and SP stages. We analyzed human CD4+CD8+ DP (Figure 7a) and CD4+SP (Figure 7b) thymocytes for the presence of Treg precursors, as well as mature Tregs. Frequencies of the Treg precursors and mature Tregs in human thymi are summarized in Figure 7c. Interestingly, both CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes contained CD25−Foxp3low and CD25+Foxp3− tTreg precursors, as well as CD25+Foxp3+ mature tTregs. We also determined the OX40 expression in tTreg precursors and mature tTregs. We found the highest OX40 expression in the mature CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes, followed by CD25−FOXP3low and CD25+FOXP3− Treg precursors from both CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes (Figure 7d). We also found that DP Tregs had higher OX40 and CD25 expression than SP Tregs. In addition, we found higher OX40 expression in CD25+FOXP3− SP Treg precursors than their DP counterparts (Figure 7d). Moreover, both tTreg precursors and mature tTregs preferentially over-expressed OX40 compared to CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells in DP and SP thymocytes, as we had observed with murine thymocytes. These results are indicative of the existence of a two-step process of Treg development in the human thymus, and suggest that OX40 signaling may regulate human tTreg generation in the TCR-independent phase of Treg development by targeting both tTreg precursors and mature tTregs in a manner similar to that we had noted previously in the murine thymus.

Figure 7.

Human thymic Treg precursors and mature Tregs express OX40. (a,b) CD25+Foxp3− (blue) and CD25−FOXP3low (green) Treg precursors and CD25+FOXP3+ (red) mature Tregs were gated from CD4+CD8+ DP (a) and CD4+CD8-SP (b) human thymocytes, and OX40 expression in the respective populations is shown in the histograms. Numbers in dot plots represent percentages of the indicated subsets in gated CD4+CD8+DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes. Numbers in histograms represent MFI values of OX40 (red) and isotype (gray) control. (c). Bar graph showing the frequencies of CD25−FOXP3low (green), CD25+FOXP3− (blue) and CD25+FOXP3+ (red) subsets within CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+CD8−SP thymocytes from human thymi (values represent means±SEM, n=6). (d) Bar graph showing MFI values of OX40 expression in CD25−FOXP3low (green), CD25+FOXP3− (blue) and CD25+FOXP3+ (red) subsets within CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+CD8−SP thymocytes. SP, single positive; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Previous studies have identified OX40L expression in murine TECs, but not in thymic plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and conventional DCs (cDCs).9 Since the cell types expressing OX40L in the human thymus were unknown, we analyzed human thymic pDCs, cDCs and epithelial cells for OX40L expression. Human cDCs and pDCs were defined as CD11c+CD13+CD123−BDCA2− and CD11c−CD13−CD123+BDCA2+, respectively.27 We observed OX40L expression in human pDCs, whereas cDCs expressed very low levels of OX40L (Supplementary Fig. S6A-B), which differed from murine thymic pDCs.9 However, we found higher OX40L expression in CD45−EpCAM+ human cells (Supplementary Fig. S6C), similar to our findings in murine TECs. These findings suggested that cognate interactions between OX40L and OX40 could regulate tTreg development, likely through an evolutionarily conserved mechanism.

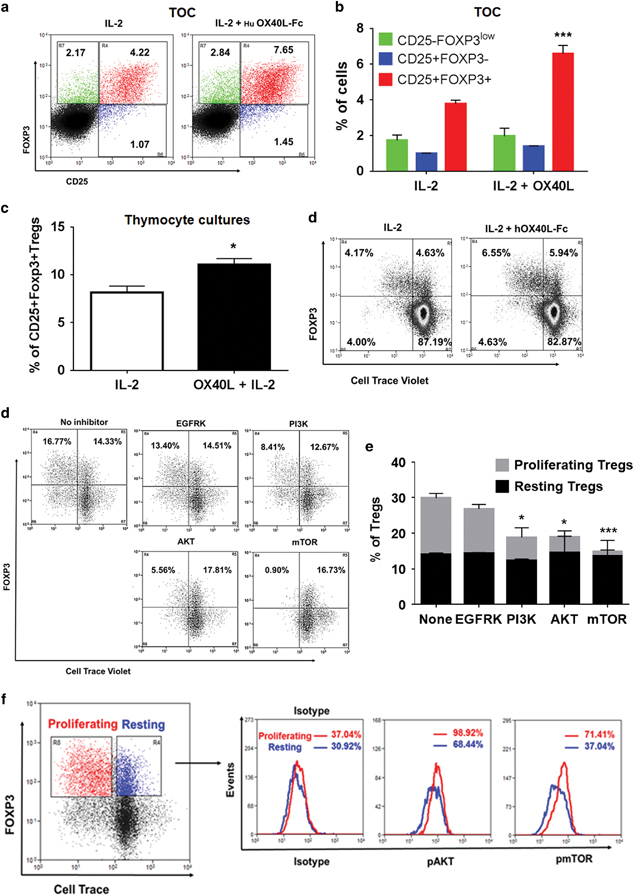

Mechanism of OX40L-IL-2-induced CAP-independent tTreg proliferation is conserved between the human and murine thymus

We evaluated whether OX40L/OX40 interactions could expand human thymic Tregs. First, we cultured human thymic fragments in 3D organ cultures with IL-2 alone or OX40L+IL-2 for 5 days. As shown in Figures 8a and b, we found a significant increase in CD25+FOXP3+ mature Tregs relative to total thymocytes (3.78%±0.20% vs 6.58%±0.47%) upon OX40L+IL-2 stimulation. Next, we cultured human thymocytes without antigen-presenting cells in 2D cultures with either IL-2 alone or OX40L+IL-2 for 5 days. We observed a significant increase in tTregs in OX40L+IL-2-treated thymocyte cultures compared to cultures treated with IL-2 alone (8.15%±1.88% vs 11.06%±1.82%) (Figure 8c). Moreover, OX40L+IL-2 treatment preferentially induced tTreg proliferation over tTconv cells in the absence of additional antigenic stimulation (Figure 8d). In contrast to earlier reports of suppression of Foxp3 by OX40 signaling, we did not observe any reduction in Foxp3 expression in either murine (Supplementary Fig. S7A) or human thymocytes in ex vivo cultures treated with OX40L (Supplementary Fig. S7C), or in vivo upon treatment with OX40L (Supplementary Fig. S7B). Furthermore, as we had observed previously with murine tTregs, kinase inhibitor assays predicted the involvement of PI3-AKT-mTOR signaling in human thymocyte proliferation (Figures 8e and f). These findings were corroborated by the observed increase in the levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-mTOR in proliferating tTregs compared to resting tTregs (Figure 8g). Taken together, our results indicated the existence of an OX40L+IL-2-induced CAP-independent tTreg proliferation mechanism regulated by AKT-mTOR signaling as an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of tTreg development.

Figure 8.

OX40L-IL-2 co-signaling induces human thymic Treg proliferation via the AKT-mTOR signaling axis. (a) Human thymic fragments were cultured in 3D TOC with human IL-2 (50 U/ml) or IL-2+human OX40L-Fc (5 μg/ml) for 5 days, and frequencies of CD25+Foxp3− (blue), CD25−FOXP3low (green) Treg precursors and CD25+FOXP3+ mature Tregs (red) were analyzed. (b) Bar graph summarizing the results shown in a (values represent means±SEM, n=3, ***p<0.005 vs IL-2). (c) Human thymocytes were cultured with human IL-2 (50 U/ml) or IL-2+human OX40L-Fc (5 μg/ml) for 5 days. Bar graph showing the percentages of CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs in cultures post-treatment (values represent means±SEM, n=6, *p<0.05 vs IL-2). (d) From the thymocyte culture experiments (c), CD4+CD8+DP and CD4+ SP thymocytes were gated, and Foxp3+ Treg proliferation within these populations was analyzed by Cell Trace Violet dilution. (e) Effects of the indicated kinase inhibitors (10 μM) on human thymic Treg proliferation analyzed as described for (c). (f) Bar graph summarizing the results shown in e (values represent means±SEM, n=3, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005 vs None). (e) Histogram overlays showing differences in the levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-mTOR between resting (blue) and proliferating (red) Tregs expanded from OX40L-IL-2-treated human thymocyte cultures. Numbers in the histograms indicate respective MFI values. TOC, thymic organ cultures; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Discussion

Tregs play a profoundly important role in the prevention of autoimmunity. Although numerous studies have provided insights into the development and function of murine tTregs,6,28 similar insights regarding the mechanism of human tTreg development and homeostasis have not yet been elucidated. Despite existing reports revealing several differences and similarities between murine and human tTreg development,14,15,29 further studies were needed to fully validate the relevance of the observations made in the murine models to humans.13,14,15 OX40 has been primarily characterized as a costimulatory molecule that is transiently expressed on activated T cells and promotes their survival and proliferation;30,31 it can also induce Th2 cell polarization.32,33 Further studies have shown that OX40 signaling, along with other TNFRSF members such as GITR and TNFRII, can facilitate tTreg differentiation,9 and a combined deficiency of OX40, GITR and TNFRII can significantly impair tTreg development.9 Moreover, we and others have shown that OX40 is constitutively expressed on murine Tregs under physiologic conditions34,35 and that OX40L can readily induce CAP-independent proliferation of peripheral Tregs in an IL-2-dependent manner.17,21 However, specific data regarding human tTreg development in general, and the role of OX40-mediated signaling in particular, is lacking. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the role of OX40-mediated signaling in the TCR-independent phase of both murine and human thymic tTreg generation.

Although human tTreg differentiation is initiated at an earlier CD4+CD8+ DP stage compared to murine tTreg differentiation, which starts at a later CD4+SP stage, OX40 expression correlated with the corresponding stages of tTreg development in both human and murine thymi. Interestingly, we observed a significant reduction in CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in the thymi of OX40−/− mice relative to those in WT mice. This is in apparent contrast to a previous report by Takeda et al. who reported a normal number of Tregs in OX40−/− mice. However, it should be noted that in their study, CD4+CD25+ expression was used to identify Tregs. Subsequently, Foxp3 expression was identified as the Treg lineage-specific marker in the thymus.36 Later, Piconese et al. reported a reduced number of CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs in OX40−/− mice,37 which is in line with our present findings. We have further extended these earlier observations by performing more detailed analyses of different subsets of Treg precursors and mature Tregs. We found a significant reduction in CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs, but not CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors. We also found a significant increase in CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs, but not CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors upon OX40L treatment, indicating that OX40 signaling might regulate tTreg generation by targeting CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs rather than CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors.

CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors were originally identified as a transient population that readily underwent apoptosis when common yc-cytokine signals were not available, and transgenic over-expression of the pro-survival factor Bcl2 prevented their apoptosis.8 However, we did not observe an increase in pro-survival factor Bcl2 expression in either CD25−Foxp3low or CD25+Foxp3+ cells upon OX40L treatment. Consistent with our findings, a previous study has shown that ectopic expression of Bcl2 failed to prevent apoptosis of Tregs when OX40, GITR and TNFRII signaling were blocked.9 Thus, increased survival of CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs is unlikely to be the mechanism by which OX40L increases tTregs. By contrast, we found increased Ki67 expression as well as Ki67+ cells within CD25−Foxp3low and CD25+Foxp3+ cells, indicating that proliferation might be the predominant mechanism underlying increased tTreg numbers, rather than increased survival.

We could not determine the effect of OX40L treatment on the proliferation of CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors in ex vivo cultures, as this particular subset of cells was rapidly converted (by 24 h) into CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs in the presence of IL-2. IL-2 has been shown to induce its receptor, IL-2Ra (CD25), expression in naive CD4+/CD8+ T cells under physiologic conditions without any antigenic stimulation,38 and it exerts a similar effect on CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors as well.8 Consistent with this observation, we found a significant increase in CD25 expression in CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors upon stimulation with OX40L+IL-2. Previously, OX40 co-stimulation has been shown to increase CD25 expression in CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs,9 which we have now shown also occurs in CD25−Foxp3low Treg precursors as well. We also noted an additive effect of OX40L on IL-2-dependent maturation of CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors in ex vivo cultures. More importantly, we found that OX40L treatment increased the proliferation of sorted mature Tregs and newly converted mature Tregs from CD25+Foxp3− and CD25−Foxp3low tTreg precursors in the absence of TCR stimulation. Thus, we describe two key roles played by OX40 signaling in the development of nTregs in the thymus: (1) OX40L augments IL-2-dependent maturation of CD25−Foxp3low and CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursors into CD25+Foxp3+ mature Tregs, which is a critical step in the TCR-independent phase of nTreg generation in the thymus. This IL-2-dependent maturation process is distinct from TGF-β-mediated iTreg generation, which requires TCR stimulation; and (2) OX40 signaling also increases proliferation of mature CD25+Foxp3+ nTregs. Unlike iTregs, which show unstable Foxp3 expression attributed to a higher propensity to undergo TSDR (Treg-specific demethylated region) methylation,39,40,41,42 OX40L-expanded nTregs show sustained Foxp3 expression. Further studies are required to validate the epigenetic regulation of the sustained Foxp3 expression in OX40L-expanded Tregs.

The critical role of OX40-mediated signaling in tTreg proliferation was further shown by the reduced proliferation of OX40−/− Tregs relative to their WT counterparts. In addition, we observed a significant reduction in IL-2 expression by OX40−/− thymocytes upon TCR activation, which is an essential factor for tTreg development.15 Previous studies have shown that OX40 stimulation can boost Treg expansion by increasing IL-2 secretion from Teff cells under low-inflammatory conditions.43 However, our results of OX40L-induced proliferation of sorted CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs, which were devoid of Teff cells, indicated a direct role for OX40 signaling in tTreg proliferation.

The role of IL-2-dependent STAT5 signaling in driving Treg maturation and survival is well-established.7,9 However, the cell signaling mechanisms driving CAP-independent tTreg proliferation induced by OX40L+IL-2 are unknown. Croft et al. have identified the involvement of the activation of PI3K/PKB (Akt) and NF-kB1 signaling by OX40 stimulation in promoting Teff cell survival and proliferation under varying conditions of TCR stimulation. Furthermore, they have shown that OX40L–OX40 interactions can result in the formation of a signalosome containing TRAF2, IKKa, IKKb, PI3K and AKT, leading to NF-kB1 activation.44,45,46,47,48 Although we have previously shown the involvement of NF-kB1 signaling in peripheral Treg proliferation induced by OX40L+IL-2,21 results from our kinase inhibitor assays herein suggested the involvement of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in both murine and human tTreg proliferation induced by OX40L+IL-2. This finding is further supported by the increased levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-mTOR that we noted in WT tTregs, but not in OX40−/− tTregs, upon OX40L+IL-2 stimulation compared to stimulation with IL-2 alone. These results revealed a key role for AKT-mTOR signaling in CAP-independent tTreg proliferation caused by OX40 signaling. We also observed increased levels of pAKT and pmTOR in proliferating human tTregs compared to resting tTregs. These findings are in contrast to earlier reports of the loss of FoxP3 expression due to either constitutive activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling49 or loss of PTEN activity, which leads to enhanced PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation.50 OX40 signaling has also been shown to negatively regulate Foxp3 expression and Treg functions under pro-inflammatory conditions.51 However, we did not observe any reduction in Foxp3 expression upon OX40L co-stimulation in both murine and human thymic Tregs in vitro or in thymic Tregs from OX40L-treated mice. By contrast, we observed a negative effect of OX40L treatment on the TGF-β-induced adoptive conversion of CD4+CD25−Foxp3− Tconv cells to CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ iTregs, a process that requires TCR stimulation; this is consistent with the reported negative effects of OX4051,52 and PI3K/AKT signaling on Foxp3 induction from Tconv cells.49,50

We observed the preferential over-expression of OX40 in CD25+FOXP3− and CD25−FOXP3low Treg precursors and CD25+Foxp3+ mature tTregs from both CD4+CD8+DP and CD4+SP human thymocytes, indicating that OX40 signaling might regulate human tTreg differentiation in both DP and SP stages. Higher levels of OX40 expression in CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs within DP thymocytes compared to their CD4+ SP counterparts are consistent with a higher TCR signal strength experienced by those cells during early stages of differentiation in the murine thymus.9,14 We have also observed low levels of OX40 expression in both murine and human circulating Tregs (data not shown), which is consistent with previous reports.53 We observed higher OX40L expression on human TECs at levels similar to murine TECs;9 thus, cognate interactions between OX40 expressed on Tregs and OX40L expressed on TECs might regulate human tTreg development as well. Human thymic organ culture results showed approximately twofold increase in CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs upon OX40L+IL-2 stimulation compared to stimulation with IL-2 alone and indicated the ability of OX40 signaling to increase human tTregs. More importantly, similar to our findings with murine thymocytes, we observed selective proliferation of tTregs, but not Tconv cells, in human thymocytes treated with OX40L+IL-2 in the absence of either APCs or TCR stimulation. Thus, notwithstanding the differences in the stages of tTreg development, both human and murine Tregs likely share a similar OX40-mediated mechanism of Treg development and homeostasis.

Treatment with an OX40 agonist increased the functional Treg numbers and was found to be protective against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis54 and T1D35,55 when given during antigen priming due to its primary effect on Tregs. By contrast, OX40L treatment during the effector phase increased Teff functions and exacerbated these diseases.54,56 A combinatorial therapy of OX40L with agents that can suppress its effects on Teff cells and enhance Treg function, such as Jagged-1 and IL-2, induced tolerance in type-1 diabetes16 and long-term allograft survival in transplantation models.57 An OX40 agonist was tested in combination with a PD-1 checkpoint blockade to treat murine tumors due to its potent Teff co-stimulatory functions. Although an initial study showed synergistic effects in a murine model of ovarian cancer,58 a recent study showed a weakened anti-tumor response in a lung carcinoma model upon concurrent treatment of the OX40 agonist with PD1 blockade.59 More recently, tumor infiltrating Tregs in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients were found to express higher levels of OX40 compared to Tconv cells. The use of an agonistic OX40 mAb for treating head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with the intention of suppressing FOXP3 expression while increasing Teff functions has been proposed.60,61 However, our results suggest that OX40 signaling might not only augment tTreg generation but also cause peripheral Treg proliferation.35 Given the immune-suppressive nature of tumor microenvironment62 as well as additional studies showing the ability of OX40 agonists to increase the expansion of Tregs in appropriate cytokine milieus,54 it is prudent to consider the potential effects of enhanced OX40-mediated signaling on Treg expansion when considering its immune-enhancing effects as a co-stimulator of Teff cells.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health for grants #R01 AI107516-01A1 and #1R41AI125039-01. We thank the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) for grant #2-SRA-2016-245- S-B to Dr. Prabhakar. We thank the American Heart Association for offering a post-doctoral fellowship #15POST25090228 to PK.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Cellular & Molecular Immunology website 10.1038/cmi.2018.8

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: key controllers of immunologic self-tolerance. Cell. 2000;101:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HM, Bautista JL, Hsieh CS. Thymic and peripheral differentiation of regulatory T cells. Adv Immunol. 2011;112:25–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387827-4.00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan MS. Thymic selection of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide (vol 2, pg 301, 2001) Nat Immunol. 2001;2:468–468. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieback E, Hilgenberg E, Stervbo U, Lampropoulou V, Shen P, Bunse M, et al. Thymus-derived regulatory T cells are positively selected on natural self-antigen through cognate interactions of high functional avidity. Immunity. 2016;44:1114–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lio CW, Hsieh CS. A two-step process for thymic regulatory T cell development. Immunity. 2008;28:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai X, Erman B, Alag A, Mu J, Kimura M, Katz G, et al. Foxp3 transcription factor is proapoptotic and lethal to developing regulatory T cells unless counterbalanced by cytokine survival signals. Immunity. 2013;38:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmud SA, Manlove LS, Schmitz HM, Xing Y, Wang Y, Owen DL, et al. Costimulation via the tumor-necrosis factor receptor superfamily couples TCR signal strength to the thymic differentiation of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:473–481. doi: 10.1038/ni.2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu FT, Yang W, Wang YH, Ma HD, Tang W, Yang JB, et al. Thymic B cells promote thymus-derived regulatory T cell development and proliferation. J Autoimmun. 2015;61:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazzal D, Gradolatto A, Truffault F, Bismuth J, Berrih-Aknin S. Human thymus medullary epithelial cells promote regulatory T-cell generation by stimulating interleukin-2 production via ICOS ligand. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1420. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:490–500. doi: 10.1038/nri2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caramalho I, Nunes-Cabaco H, Foxall RB, Sousa AE. Regulatory T-cell development in the human thymus. Front Immunol. 2015;6:395. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunes-Cabaco H, Caramalho I, Sepulveda N, Sousa AE. Differentiation of human thymic regulatory T cells at the double positive stage. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3604–3614. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caramalho I, Nunes-Silva V, Pires AR, Mota C, Pinto AI, Nunes-Cabaco H, et al. Human regulatory T-cell development is dictated by Interleukin-2 and -15 expressed in a non-overlapping pattern in the thymus. J Autoimmun. 2015;56:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P, Alharshawi K, Bhattacharya P, Marinelarena A, Haddad C, Sun Z, et al. Soluble OX40L and JAG1 induce selective proliferation of functional regulatory T-cells independent of canonical TCR signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39751. doi: 10.1038/srep39751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharya P, Gopisetty A, Ganesh BB, Sheng JR, Prabhakar BS. GM-CSF-induced, bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells can expand natural Tregs and induce adaptive Tregs by different mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:235–249. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopisetty A, Bhattacharya P, Haddad C, Bruno JC, Jr., Vasu C, Miele L, et al. OX40L/Jagged1 cosignaling by GM-CSF-induced bone marrow-derived dendritic cells is required for the expansion of functional regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:5516–5525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto Y, Douek DC, McFarland RD, Koup RA. Effects of exogenous interleukin-7 on human thymus function. Blood. 2002;99:2851–2858. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xing Y, Hogquist KA. Isolation, identification, and purification of murine thymic epithelial cells. J Vis Exp 2014, e51780 e-pub ahead of print Aug;10.3791/51780(90). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Alharshawi K, Marinelarena A, Kumar P, El-Sayed O, Bhattacharya P, Sun Z, et al. PKC- is dispensable for OX40L-induced TCR-independent Treg proliferation but contributes by enabling IL-2 production from effector T-cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6594. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vail ME, Chaisson ML, Thompson J, Fausto N. Bcl-2 expression delays hepatocyte cell cycle progression during liver regeneration. Oncogene. 2002;21:1548–1555. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinkel S, Gross A, Yang E. BCL2 family in DNA damage and cell cycle control. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1351–1359. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng GY, Yu AX, Dee MJ, Malek TR. IL-2 R Signaling Is Essential for Functional Maturation of Regulatory T Cells during Thymic Development. Journal of Immunology. 2013;190:1567–1575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W, Konkel JE. Development of thymic Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells: TGF-beta matters. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:958–965. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Gayo E, Sierra-Filardi E, Corbi AL, Toribio ML. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells resident in human thymus drive natural Treg cell development. Blood. 2010;115:5366–5375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang YQ, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:401–410. doi: 10.1038/ni1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayer AL, Yu A, Malek TR. Function of the IL-2 R for thymic and peripheral CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4062–4071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paterson DJ, Jefferies WA, Green JR, Brandon MR, Corthesy P, Puklavec M, et al. Antigens of activated rat T lymphocytes including a molecule of 50,000 Mr detected only on CD4 positive T blasts. Mol Immunol. 1987;24:1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(87)90122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallett S, Fossum S, Barclay AN. Characterization of the MRC OX40 antigen of activated CD4 positive T lymphocytes—a molecule related to nerve growth factor receptor. EMBO J. 1990;9:1063–1068. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maddur MS, Sharma M, Hegde P, Stephen-Victor E, Pulendran B, Kaveri SV. Human B cells induce dendritic cell maturation and favour Th2 polarization by inducing OX-40 ligand. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4092. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.So T, Song J, Sugie K, Altman A, Croft M. Signals from OX40 regulate nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 and T cell helper 2 lineage commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600205103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura N, Murata S, Ueki T, Mekata E, Reilly RT, Jaffee EM, et al. OX40 costimulation can abrogate Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of antitumor immunity. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:630–638. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alharshawi K, Marinelarena A, Kumar P, El-Sayed O, Bhattacharya P, Sun ZM, et al. PKC-theta is dispensable for OX40L-induced TCR-independent Treg proliferation but contributes by enabling IL-2 production from effector T-cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6594. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda I, Ine S, Killeen N, Ndhlovu LC, Murata K, Satomi S, et al. Distinct roles for the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction in regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3580–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piconese S, Pittoni P, Burocchi A, Gorzanelli A, Care A, Tripodo C, et al. A non-redundant role for OX40 in the competitive fitness of Treg in response to IL-2. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2902–2913. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sereti I, Gea-Banacloche J, Kan MY, Hallahan CW, Lane HC. Interleukin 2 leads to dose-dependent expression of the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor on CD25-negative T lymphocytes in the absence of exogenous antigenic stimulation. Clin Immunol. 2000;97:266–276. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, Kim YC, Laurence A, Punkosdy GA, Shevach EM. IL-2 controls the stability of Foxp3 expression in TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;186:6329–6337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenecke C, Czeloth N, Bubke A, Schmitz S, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, et al. Alloantigen-specific de novo-induced Foxp3+ Treg revert in vivo and do not protect from experimental GVHD. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3091–3096. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okada M, Hibino S, Someya K, Yoshmura A. Regulation of regulatory T cells: epigenetics and plasticity. Adv Immunol. 2014;124:249–273. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800147-9.00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baeyens A, Saadoun D, Billiard F, Rouers A, Gregoire S. Zaragoza B, et al. Effector T cells boost regulatory T cell expansion by IL-2, TNF, OX40, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells depending on the immune context. J Immunol. 2015;194:999–1010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Croft M, So T, Duan W, Soroosh P. The significance of OX40 and OX40L to T-cell biology and immune disease. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:173–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Croft M. Control of immunity by the TNFR-related molecule OX40 (CD134) Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.So T, Croft M. Regulation of PI-3-kinase and Akt signaling in T lymphocytes and other cells by TNFR family molecules. Front Immunol. 2013;4:139. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song J, So T, Croft M. Activation of NF-kappaB1 by OX40 contributes to antigen-driven T cell expansion and survival. J Immunol. 2008;180:7240–7248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.So T, Soroosh P, Eun SY, Altman A, Croft M. Antigen-independent signalosome of CARMA1, PKC theta, and TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) determines NF-kappa B signaling in T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2903–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008765108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, et al. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huynh A, DuPage M, Priyadharshini B, Sage PT, Quiros J, Borges CM, et al. Control of PI(3) kinase in Treg cells maintains homeostasis and lineage stability. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:188–196. doi: 10.1038/ni.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vu MD, Xiao X, Gao W, Degauque N, Chen M, Kroemer A, et al. OX40 costimulation turns off Foxp3+ Tregs. Blood. 2007;110:2501–2510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.So T, Croft M. Cutting edge: OX40 inhibits TGF-beta- and antigen-driven conversion of naive CD4 T cells into CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1427–1430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagar M, Jacob-Hirsch J, Vernitsky H, Berkun Y, Ben-Horin S, Amariglio N, et al. TNF activates a NF-kappa B-regulated cellular program in human CD45RA(-) regulatory T Cells that modulates their suppressive function. J Immunol. 2010;184:3570–3581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruby CE, Yates MA, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Chlebeck P, Wolchok JD, Houghton AN, et al. Cutting edge: OX40 agonists can drive regulatory T cell expansion if the cytokine milieu is right. J Immunol. 2009;183:4853–4857. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bresson D, Fousteri G, Manenkova Y, Croft M, von Herrath M. Antigen-specific prevention of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice is ameliorated by OX40 agonist treatment. J Autoimmun. 2011;37:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haddad CS, Bhattacharya P, Alharshawi K, Marinelarena A, Kumar P, El-Sayed O, et al. Age-dependent divergent effects of OX40L treatment on the development of diabetes in NOD mice. Autoimmunity. 2016;49:298–311. doi: 10.1080/08916934.2016.1183657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiao X, Gong W, Demirci G, Liu W, Spoerl S, Chu X, et al. New insights on OX40 in the control of T cell immunity and immune tolerance in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;188:892–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Z, Wang X, Cheng D, Xia Z, Luan M, Zhang S. PD-1 blockade and OX40 triggering synergistically protects against tumor growth in a murine model of ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shrimali RK, Ahmad S, Verma V, Zeng P, Ananth S, Gaur P, et al. Concurrent PD-1 blockade negates the effects of OX40 agonist antibody in combination immunotherapy through inducing T-cell apoptosis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:755–766. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montler R, Bell RB, Thalhofer C, Leidner R, Feng Z, Fox BA, et al. OX40, PD-1 and CTLA-4 are selectively expressed on tumor-infiltrating T cells in head and neck cancer. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5:e70. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bell RB, Leidner RS, Crittenden MR, Curti BD, Feng Z, Montler R, et al. OX40 signaling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Overcoming immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Oral Oncol. 2016;52:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Boehmer H, Daniel C. Therapeutic opportunities for manipulating T-Reg cells in autoimmunity and cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:51–63. doi: 10.1038/nrd3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.