This study characterized the β4-integrin interacting proteome using BioID proximity-dependent biotinylation in epithelial MDCK cells. The analysis identified several novel type II hemidesmosome (HD)-associated proteins and revealed potential connecting protein modules that could orchestrate the observed coordinated coassembly of HDs and focal adhesions (FAs). Curiously, unlike the formation of HDs, the assembly of β4-interactome did not depend on α6β4-heterodimerization.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Extracellular Matrix, Protein Complex Analysis, Mass Spectrometry, Kidney Function or Biology, BioID, Epithelium, Hemidesmosome, Integrin

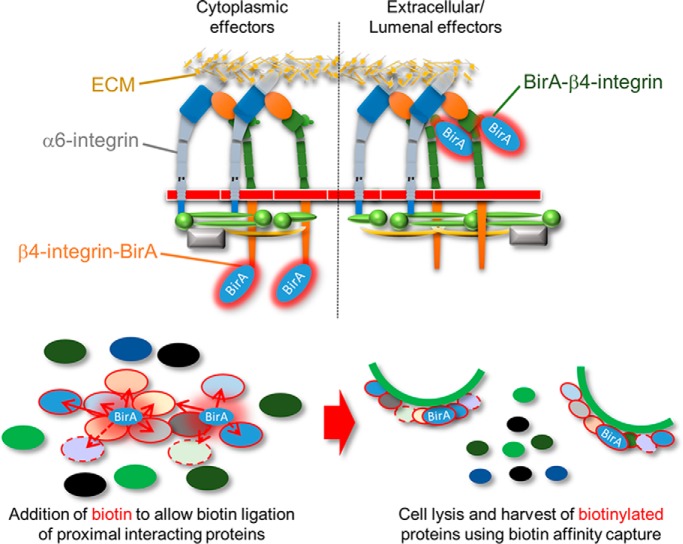

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

This study reports the first proteomic characterization of a type II hemidesmosomal complex.

This study characterizes the interactome of β4-integrin in the presence and absence of α6-integrin in a simple epithelial cell model.

The assembly of the β4-integrin interacting complex was largely independent of α6-integrin expression.

Abstract

Integrin-mediated laminin adhesions mediate epithelial cell anchorage to basement membranes and are critical regulators of epithelial cell polarity. Integrins assemble large multiprotein complexes that link to the cytoskeleton and convey signals into the cells. Comprehensive proteomic analyses of actin network-linked focal adhesions (FA) have been performed, but the molecular composition of intermediate filament-linked hemidesmosomes (HD) remains incompletely characterized. Here we have used proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) technology to label and characterize the interactome of epithelia-specific β4-integrin that, as α6β4-heterodimer, forms the core of HDs. The analysis identified ∼150 proteins that were specifically labeled by BirA-tagged integrin-β4. In addition to known HDs proteins, the interactome revealed proteins that may indirectly link integrin-β4 to actin-connected protein complexes, such as FAs and dystrophin/dystroglycan complexes. The specificity of the screening approach was validated by confirming the HD localization of two candidate β4-interacting proteins, utrophin (UTRN) and ELKS/Rab6-interacting/CAST family member 1 (ERC1). Interestingly, although establishment of functional HDs depends on the formation of α6β4-heterodimers, the assembly of β4-interactome was not strictly dependent on α6-integrin expression. Our survey to the HD interactome sets a precedent for future studies and provides novel insight into the mechanisms of HD assembly and function of the β4-integrin.

Laminin-rich basement membrane conveys critical signals and serves as a scaffold to guide epithelial cell polarity and morphogenesis (1–3). Multiple laminin receptors synergistically promote laminin assembly by increasing its local concentration at the cell surface and transmit downstream signaling into the cell (1). However, the molecular effectors conveying these signals remain incompletely characterized.

Integrins are a large family of αβ-heterodimeric extracellular matrix (ECM)1 receptors that recognize short peptide motifs found in many ECM proteins, including laminins (4). Integrins do not possess intrinsic enzymatic activity. Instead, they cluster together and interact with cytoplasmic effectors that in turn recruit numerous additional components to form large multiprotein complexes, collectively termed as integrin-associated complexes (5–7). β1- and β4-integrins form distinct adhesion complexes, focal adhesions (FA) and hemidesmosomes (HD), respectively, but they both bind to laminin and might thus synergistically contribute to laminin adhesion and signaling. β1-integrins form actin-linked FAs and convey many critical functions in epithelial cells (8–10). Unlike β1-integrin, β4-integrin pairs only with α6-subunit and contains an unusually large cytoplasmic tail that links to intermediate filament network at HDs. Two types of HDs exist, type I HDs are highly organized structures formed at the basal layer of stratified epithelium, such as in the skin epidermis, where they link the epidermal-dermal layers, providing mechanical strength and durability (11). Simple epithelial cells contain type II HDs that are less complex and much less studied (12). Although HDs are generally considered for their adhesive function, β4-integrins have also been implicated in the regulation of laminin-triggered polarity signals in epithelial cells (13–15).

Although a number of comprehensive proteomics-based studies have been performed in fibroblasts and lymphoblasts to characterize the components of FAs, little attention has been put on the composition of HDs in epithelial cells. Here we have characterized the β4-interactome in Madin Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells using biotin ligase (BirA)-based BioID proximity labeling technique (16). In MDCK cells, α6β4-integrins form adhesions that resemble type II HDs. The MDCK-HDs colocalized with basal laminin patches, presumably demarcating sites of cell-driven laminin-assembly. Efficient formation of MDCK-HDs required both α6- and β4-integrins. Proteomic analysis of β4-integrin proximal proteins identified ∼150 proteins including several proteins previously associated with HDs, but also many novel β4-interacting candidate proteins, such as proteins presumably involved in folding of integrin-β4. α6β4-integrin HDs were adjacent but distinct from actin-linked FAs. This was reflected by the presence of several proteins in the β4-interactome that might indirectly couple α6β4-integrin mediated adhesions to the actin cytoskeleton. Surprisingly, the composition of β4-interactome was found to be largely unaffected by depletion of α6-integrin expression. An increased abundance of a few FA-associated proteins, such as KN Motif and Ankyrin Repeat Domains 2 (KANK2), and proteins involved in folding at the ER, such as protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs), where observed in the β4-interactome of α6-depleted cells. Therefore, our data suggests that β4-integrin can associate with most of its hemidesmosomal effectors without forming a heterodimer with α6-integrin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

MDCK Heidelberg strain II cells (gift from Dr. Kai Simons (Max-Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany)) were routinely cultured in MEM containing 5% fetal bovine serum with 1% penicillin and streptomycin (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibodies and Reagents

Mouse monoclonal anti-Itgβ1 (TS2/16) and rat monoclonal anti-Itgβ1 (AIIB2) were gifts from Dr. Karl Matlin (University of Chicago, Chicago). Guinea pig polyclonal anti-plectin antibody was a gift from Dr. Marija Plodinec (Biozentrum, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland). Goat polyclonal anti-Itgβ4 (sc-6628) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc (sc-789) antibodies were purchased from Santa-Cruz. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-LNγ1 (L9393) and anti-ERC1 (HPA019523) as well as mouse monoclonal antibodies anti-β-tubulin (T4026) and anti-talin (T3287) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit polyclonal anti-laminin-5 (ab14509) was from Abcam, Cambridge, UK, rat monoclonal anti-Itgα6/GoH3 (555734) was from BD Biosciences, Becton Dickinson Oy, Vantaa, Finland and mouse monoclonal anti-utrophin (MANCHO3/8A4) was from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City. All secondary antibodies, nonspecific goat and rat IgG isotype controls and HRP-conjugated streptavidin were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearchEurope Ltd., Cambridge, UK. Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin and Alexa Fluor 555-streptavidin were from Thermo Fisher Scientific and DAPI was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

Two to six independent biological replicates of each sample (Parental MDCK cells; hβ4-BirA cells; hβ4-BirA+α6KO cells; BirA-hβ4 cells; BirA-hβ4+α6KO cells; BirA-GFP cells and myrGFP-BirA cells) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS (supplemental Tables S1, S2, and S4). Proteins that were enriched at least 3-fold in hβ4-BirA or BirA-hβ4 cells when compared with control cells were determined as components of β4-interactome. The β4-interactome was also validated by comparing it with BirA-GFP- and myr-GFP-BirA-interactomes (supplemental Table S2). Colocalization analysis was done using samples from at least three independent experiments. The number of images for each assay is indicated in figure legends. The test of normality was performed using Shapiro-Wilk test. Single comparisons were tested for significance with student′s two-tailed unpaired t test and multiple comparisons with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s post hoc test. Analysis of bitmaps of segmented objects (>100 pixels ∼1 μm2) in different cell lines was performed on samples from 3–5 independent experiments as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was tested with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s or Games-Howell′s post hoc test.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Microscopy

Cells were seeded at 3 × 104/cm on 11 mm Ø acid washed glass coverslips in 24-wells for confocal microscopy or on CELLview™ glass bottom dishes (Greiner, Bionordika, Helsinki, Finland) for TIRF microscopy and cultured for 6 days. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS+/+ (PBS with 0.5 mm MgCl2 and 0.9 mm CaCl2) for 15 min at room temperature. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described (17). Confocal images were acquired with the Zeiss LSM 780 laser scanning confocal microscope using 40× Plan-Apochromat objective (NA = 1.4) and TIRF images were acquired with the Zeiss Cell Observer spinning disc confocal equipped with Hamamatsu camera (EMCCD) using the alpha Plan-Apochromat 63x oil objective (NA = 1.46). Image acquisition software was ZEN (black edition, LSM 780; blue edition Cell Observer; Carl Zeiss Oy, Vantaa, Finland).

Image Analysis

Colocalization in TIRF images was assessed with the Pearson′s correlation coefficient measured with the Colocalization Threshold plugin in FIJI using Costes method auto threshold determination and excluding zero intensity pixels. Segmentation of adhesions from TIRF images was performed with the Squassh plugin developed for FIJI (18).

Immunoprecipitation, Surface Biotinylation and Streptavidin Precipitation

Lysates prepared in RIPA buffer (0.15 m NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 10 mm TRIS-HCl pH 7.5) were rotated 30 min at +4 °C with Benzonase® Nuclease (Novagen, Helsinki, Finland) and centrifuged through a 0.45 μm Spin-X® filter (Corning, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Helsinki, Finland). Immunoprecipitation was performed in a sequential manner as previously described (19) using protein G Dynabeads® (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell surface biotinylation was performed as previously described (20) for cells that were seeded 24 h prior at a density of 4.5 × 104/cm onto 10 cm Ø tissue culture dishes. Streptavidin precipitation was performed similar to immunoprecipitation, but using MyOne™ Dynabeads® (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

BirA biotinylation products were separated on 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Helsinki, Finland), and other proteins of interest on 6–7.5% SDS-PAGE gels. Western blotting was done overnight at +4 °C at 20V in 20% ethanol 0.025 m Tris 0.192 m glycine onto nitrocellulose membranes (PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland). Immunolabeling and detection was performed as previously described (17). Labeling with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (to visualize surface biotinylated integrins or BirA biotinylation products) was done for 1 h at room temperature. BirA biotinylation products were also visualized directly by colloidal Coomassie staining (21).

Molecular Cloning and Expression of β4-BirA Fusion Constructs

C- and N-terminal fusion of BirA with human integrin β4 was generated by exponential megapriming (EMP) PCR (22) using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Bio Nordika Oy, Helsinki, Finland). A linker consisting of six glycines was incorporated between BirA and integrin β4 in both cases. For the C-terminal fusion, BirA was amplified from pcDNA3.1 mycBioID plasmid (23) with 5′-AAACTCATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTGGGCGGAGGCGGAGGCGGAAAGGACAACACCGTGCCC-3′ and 5′-CTTCTCTGCGCTTCTCAGG-3′ and the product used as a reverse megaprimer with 5′-GACCATCATCATCATCATCATTG-3′ to amplify pcDNA3.1/Myc-His beta4 (24) (Addgene, Cambridge, MA #16039). For the N-terminal fusion, BirA was amplified with 5′-AAGGACAACACCGTGCCC-3′ and 5′-GCCTTCTTGCAGCGGTTTCCGCCTCCGCCTCCGCCCTTCTCTGCGCTTCTCAGG-3′ and used as a forward megaprimer with 5′-TGCCAAGGTCCCAGAGAG-3′ reverse primer to amplify pcDNA3.1-BirA-hβ4-Myc as described above to insert BirA after the signal sequence of integrin-β4. The subsequent EMP-cloning steps were conducted as previously described (22). N-terminally BirA-tagged GFP (BirA-GFP) and myristoylated C-terminally BirA-tagged GFP (myr-GFP-BirA) were used as additional controls. To generate stable cell lines, plasmids were linearized with MluI (New England Biolabs), purified and electroporated into MDCK cells using Ingenio® Electroporation Kit (Mirus Bio Immuno Diagnostic OY, Hämeenlinna, Finland) with Nucleofector™ Device (Lonza, Bio Nordika Oy, Helsinki, Finland). Neomycin-resistant clonal cells were screened for expression by Western immunoblotting using anti-Myc antibodies.

Biotin Ligation and Sample Preparation for LC-MS/MS

Cells were seeded as 4.5 × 104/cm on a 10 cm Ø dish (Western blotting) or three 15 cm Ø dishes (LC-MS/MS) and cultured for 24 h in the presence of 50 μm biotin. Cells were washed three times with cold PBS+/+, scraped into 50 ml falcon tubes and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min at +4 °C. Cell pellets were snap frozen with liquid nitrogen. Cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins purified from cell lysates using Strep-Tactin Sepharose beads (IBA Lifesciences, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Helsinki, Finland) as described in (25). For LC-MS/MS samples were prepared as follows: cysteine bonds were reduced with 5 mm Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at 37 °C and alkylated with 10 mm iodoacetamide (Fluka, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Helsinki, Finland; Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. A total of 1 μg of Sequencing Grade Modified Trypsin (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) was added and samples digested overnight at 37 °C. Samples were quenched with 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and purified with C-18 Micro SpinColumns (Nest Group Inc., Thermo Fischer Scientific, Helsinki, Finland) eluting the samples to 0.1% TFA in 50% acetonitrile (ACN). Samples were dried by vacuum concentration and peptides were reconstituted in 30 μl buffer A (0.1% TFA and 1% ACN in LC-MS grade water) and vortexed thoroughly.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on an Orbitrap Elite ETD hybrid mass spectrometer using the Xcalibur version 2.2 SP 1.48 coupled to EASY-nLCII-system (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific) via a nanoelectrospray ion source. 6 μl and 5 μl of peptides were loaded from Strep-Tag and BioID-samples, respectively. Samples were separated using a two-column setup consisting of a C18 trap column (EASY-Column™ 2 cm x 100 μm, 5 μm, 120 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by C18 analytical column (EASY-Column™ 10 cm x 75 μm, 3 μm, 120 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were eluted from the analytical column with a 60min linear gradient from 5 to 35% buffer B (buffer A: 0.1% FA, 0.01% TFA in 1% acetonitrile; buffer B: 0.1% FA, 0.01% TFA in 98% acetonitrile). This was followed by 5 min 80% buffer B, 1 min 100% buffer B followed by 9 min column wash with 100% buffer B at a constant flow rate of 300 nl/min. Analysis was performed in data-dependent acquisition mode where a high resolution (60,000) FTMS full scan (m/z 300–1700) was followed by top20 CID-MS2 scans (energy 35) in ion trap. Maximum fill time allowed for the FTMS was 200 ms (Full AGC target 1,000,000) and 200 ms for the ion trap (MSn AGC target 50,000). Precursor ions with more than 500 ion counts were allowed for MSn. To enable the high resolution in FTMS scan preview mode was used. The MS data, thermo.raw files, spectral libraries (msf-files), and converted mgf-formats for all the above runs are available in a publicly accessible PeptideAtlas raw data repository (http://www.peptideatlas.org/PASS/PASS01198) with deposit ID:PASS01198.

LC-MS/MS Data Analysis

SEQUEST search algorithm in Proteome DiscovererTM software (Version 1.4.1.14, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for peak extraction and protein identification from the acquired MS2 spectral data files (Thermo.RAW) using the dog reference proteome (taxonomy Canis lupus familiaris) database (28793 entries, http://www.uniprot.org/, version 2015–09). The decoy database was the reverse of the target database. All data were reported based on 95% confidence for protein identification, as determined by the false discovery rate (FDR) ≤5%. Allowed error tolerances were 15 ppm and 0.8 Da for the precursor and fragment ions, respectively. Database searches were limited to fully tryptic peptides allowing one missed cleavage, and carbamidomethyl +57,021 Da (C) of cysteine residue was set as fixed, and oxidation of methionine +15,995 Da (M) as dynamic modifications. For peptide identification FDR was set to <0.05. For label-free quantification, SCs for each protein in each sample was extracted and used in relative quantification of protein abundance changes.

Protein Identification with MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

MDCK cells growing on a 10 cm TC-dish were lysed with RIPA buffer and immunoprecipitated as described above using protein G Dynabeads® and β4-integrin antibodies. Immunoprecipitated β4-integrin complexes were washed three times with RIPA buffer, dissolved into SDS sample buffer and separated using SDS-PAGE and proteins were visualized by colloidal Coomassie staining (21). Three bands (>200, ∼150 and ∼120kD) were visible on the gel. The gel pieces were excised and de-stained by three 5 min incubations with 50 mm ammoniumbicarbonate containing 40% acetonitrile. The gel pieces were then reduced with 20 mm DTT, followed by alkylation with 40 mm iodoacetamide each for 30 min at room temperature. The gel pieces were then washed once with de-staining buffer and twice with 40 mm ammoniumbicarbonate with 9% acetonitrile, followed by an overnight trypsin-treatment (Sigma-Aldrich, proteomics grade) at 37 °C. 0.5 μl of the supernatant was applied to the mass spectrometers sample plate (anchor chip (800–384), Bruker Nordic AB, Solna, Sweden) and allowed to dry, followed by addition of 0.5 μl of the matrix solution (0.8 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 85% acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and 1 mm NH4H2PO4). Mass spectra were recorded with a UltrafleXtreme MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometer in automatic mode, which first measured MS spectra using external calibration (Bruker peptide calibration standard). For the MS spectra the measuring algorithm selected up to 10 ions for MS/MS interrogation. Flex analysis as part of Bruker compass 1.3 and BioTools 3.2 were used for the peaklist generation. Other Mammalia reference sequence database (2,247,961 entries, version NCBInr_2013–01) was searched using the Mascot search engine (Version 2.4.1, Matrix science) applying combined MS and MS/MS data to maximize identification confidence to identify multiple proteins. Database searches were limited to fully tryptic peptides (C-terminal to R and K, if next residue is anything but P) allowing one missed cleavage, carbamidomethyl +57,021 Da (C) of cysteine residue was set as fixed and oxidation of methionine +15,995 Da (M) as dynamic modification. Typical search conditions were 20 ppm mass tolerance for MS and 0.7 Da for MS/MS data, no species restriction.

Retrovirus-mediated Gene Knockdown

DGKD cells were generated by infection of MDCK cells with retroviruses encoding for shRNA constructs and selection of infected cells with puromycin as previously described (13). Two targeting sequences were selected and KD efficiency was determined by qPCR as previously described (supplemental Table S6–S7) (13). Knockdown efficiency of DG was assessed with the ΔΔCT method using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and TATA binding protein (TBP) as housekeeping genes for normalization (supplemental Table S7).

Lentivirus-mediated Gene Knockout

Gene editing with Cas9 and sgRNA expressing lentivirus (LentiCRISPR) was achieved as previously described (26). Two separate target sequences from constitutive early exons were selected for each gene (supplemental Table S8). Target sequences with no off-target sites with less than three mismatches in the Canis lupus familiaris genome were selected based on FASTA similarity search tool (EMBL-EBI, Hinxton, UK). gRNA oligos with BsmBI (New England Biolabs) overhangs were subcloned into lentiCRISPRv1 or v2 and used for lentivirus preparation. To produce lentiviruses, 70–80% confluent 293T-D10 on CellBind® 10 cm Ø tissue culture dishes (Corning) were cotransfected with lentiCRISPR, pPAX2 and VSVg plasmids using Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in Opti-MEM™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For infection, viral supernatant was either used directly (LentiCRISPRv2), or concentrated 100× and then used as 1/10 dilution (LentiCRISPRv1) as described before (27). Subconfluent MDCK cells, seeded at a density of 6 × 104/24-well the previous day, were infected for a period of 24 h, expanded for another 24 h without virus and then trypsinized, reseeded and cultured for 24 h in the presence of 6 μg/ml puromycin to select transduced cells. Clonal cell lines were established from the puromycin resistant population and analyzed by western immunoblotting and sequencing the targeted genomic DNA region. To generate double α6/β4-KO and β1/β4-KO cells, clonal β4KO cells were transduced with α6-targeting lentiCRISPR vector as described above, expanded and negatively selected by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) based on live staining with anti-α6 (GoH3) or anti-β1 (AIIB2) antibodies. Antibody staining for FACS was performed as previously described (28). Alexa Fluor 488-negative cell population was collected with the BD FACSAria™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For amplification of the targeted genomic locus, genomic DNA was extracted using the QuickExtractTM DNA Extraction Solution (Epicentre, Lucigen, Immuno Diagnostic Oy, Hämeenlinna, Finland) and amplified with the Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) using exon-flanking primers, listed in (supplemental Table S9. PCR products were either directly sequenced or first subcloned into pJET2.1/blunt cloning vector using the CloneJET™ PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing results are listed in (supplemental Table S10).

Gene Ontology Enrichment and Protein Interaction Network

Enriched gene ontology terms were extracted from The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (29) and analyzed with REVIGO (30). Interactions were retrieved from Protein Interaction Network Analysis platform (PINA) (31, 32), IRefWeb (33), IntAct and BioGRID and visualized using Cytoscape v3 (34).

Heatmaps

For heatmap visualizations, hierarchical clustering of specifically enriched proteins based on normalized average SC values was performed with Cluster 3.0 software using Euclidean distance as the similarity metric and single linkage as the clustering method. Normalized average SC values of the clustered genes were visualized with the Matrix2png program (35).

RESULTS

α6β4-integrins in MDCK Cells Colocalize with Laminins in Basal Adhesion Patches That Are Distinct from Focal Adhesions

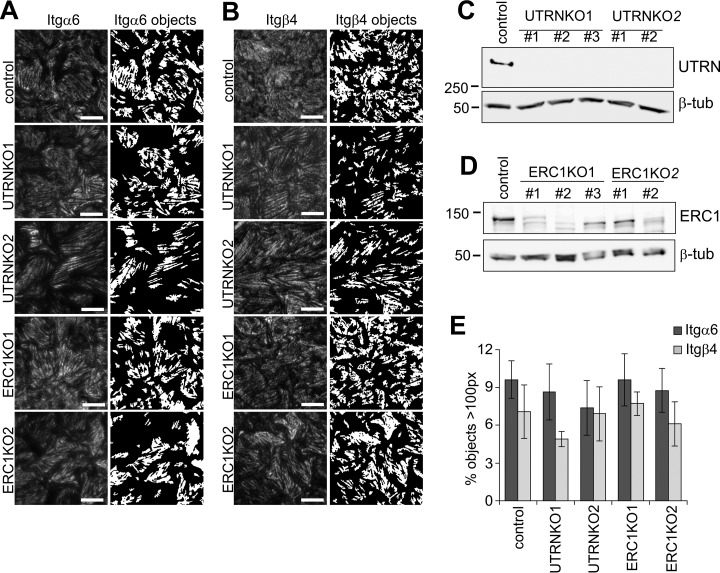

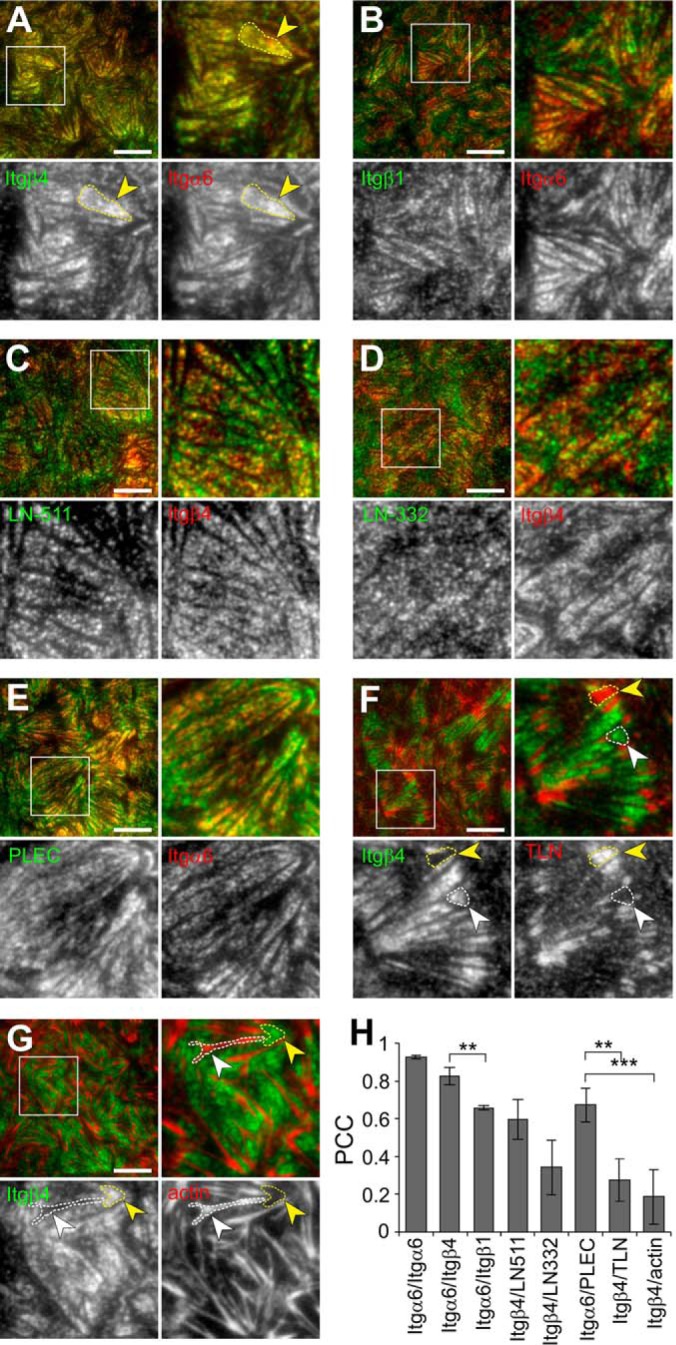

To better characterize the HDs formed in simple epithelial cells, we analyzed the adhesions formed by α6β4-integrin in MDCK cells by coimmunofluorescence staining and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) -microscopy. α6- and β4-subunits colocalized in parallel elongated patches at the basal membrane (see yellow arrowhead in Fig. 1A). Although α6-integrin can also form a heterodimer with β1-integrin, a stronger colocalization was seen with β4-subunit (Fig. 1A, 1B and 1H). MDCK cells express laminin-332 (LN-332) and -511 (LN-511), both of which are ligands of α6β4-integrin (11, 36). In confluent MDCK cells, β4-integrin showed stronger colocalization with LN-511 (Fig. 1C, 1D and 1H). MDCK cells downregulate LN-332 synthesis in confluent conditions and produce relatively more LN-511 (36, 37). Therefore, the stronger colocalization with LN-511 can be expected. To confirm that the α6β4-integrin staining demarcated HDs rather than FAs, we showed that α6β4-positive patches colocalized with a HD marker plectin (Fig. 1E and 1H) but were mutually exclusive for a FA marker talin as well as actin stress fibers (Fig. 1F–1H, yellow and white arrowheads indicate representative areas of mutual exclusion). Thus, in MDCK cells α6β4-integrins form structures resembling type II HDs described in breast epithelial cells (12). Because of the lack of working antibodies against markers that would allow us to distinguish between type I and II HDs in canine cells, we will refer to them as MDCK-HDs.

Fig. 1.

Integrin α6β4 colocalizes with plectin and laminin deposits at MDCK-HDs. A–G, TIRF microscopy of coimmunofluorescence stained integrin α6 (red) and β4 (green) (A), integrin α6 (red) and β1 (green) (B), integrin β4 (red) and laminin-511 (green) (C), integrin β4 (red) and laminin-332 (green) (D), integrin α6 (red) and plectin (green) (E), integrin β4 (green) and talin (red) (F), integrin β4 (green) and actin (red) (G). H, Quantification of colocalization between immunostained proteins in TIRF images by measuring Pearson's correlation coefficients (Mean ± S.D., n = 12–21 images from 3–4 experiments). Single comparisons were tested for significance with student′s two-tailed unpaired t test and multiple comparisons with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s post hoc test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Scale bars = 10 μm.

Generation and Characterization of MDCK Cell Lines Expressing BirA-tagged β4-Integrin Constructs

To investigate the molecular composition of MDCK-HDs, we labeled integrin β4 proximal proteins in live cells by using proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) technology as described previously (23). In the presence of exogenous biotin, a humanized version of Escherichia coli -derived biotin ligase (BirA) converts biotin into highly reactive biotinoyl-5′-AMP that will readily react with primary amines in the immediate vicinity of the BirA. When fused to a protein of interest, BirA can be used to specifically biotinylate proteins that are proximal (within ∼10–30 nm) to it and its fusion partner. BioID method is particularly suitable method to detect also weaker and more transient interactions that would be difficult to preserve in traditional pull-down assays. Here, BirA was fused to either the C- (hβ4-BirA) or N terminus (BirA-hβ4) of human integrin β4 (hβ4), and these constructs (supplemental Fig. S1) were introduced into MDCK cells by stable transfection as confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 2A). Cell surface expression of both fusion constructs was confirmed by surface biotinylation assay (Fig. 2B). β4-myc, hβ4-BirA, and to lesser extent, BirA-hβ4 fusion proteins colocalized with endogenous α6-integrin at MDCK-HDs (Fig. 2C and 2D). The BirA-hβ4 was detected as two bands, a full-length form (Fig 2A and 2B, blue arrowheads) and a truncated form (yellow arrowheads in Fig. 2A and 2B). It was noted, that the truncated form was particularly prominent in the surface-expressed pool of BirA-hβ4 (Fig. 2B). Myc-tagged hβ4 and hβ4-BirA, but not BirA-hβ4, coprecipitated a ∼120kDa protein. Peptide mass fingerprinting analysis of a similarly migrating band from β4-integrin immunoprecipitations identified this protein as α6-integrin (supplemental Table S5). These data suggest that only hβ4-BirA formed a stable heterodimer with α6-subunit (Fig. 2B). Distinct patterns of BirA-biotinylated proteins were observed in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 expressing cells (Fig. 2E) and could be efficiently precipitated with streptavidin beads in the presence of biotin (Fig. 2F). In hβ4-BirA expressing cells, the biotinylated proteins colocalized with α6-integrin within MDCK-HDs thereby confirming that hβ4-BirA, with the cytoplasmic proximity ligation activity, efficiently biotinylated proteins at HDs (Fig. 2G and 2H). Some BirA-hβ4 could be detected at the basal domain (Fig. 2C), but the staining intensity was weaker (Fig. 2C). Biotinylated targets in BirA-hβ4 expressing cells were also seen at the basal surface although they displayed a more diffuse staining pattern that only partially localized to α6-positive patches (Fig. 2G and 2H).

Fig. 2.

Biotinylation of MDCK-HD associated proteins by integrin β4-BirA fusion constructs. A, Expression of Myc-tagged human integrin β4 subunit (hβ4; red asterisk) and Myc-β4 integrin-BirA fusion constructs (hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4) was analyzed by western immunoblotting. Myc-tagged BirA-hβ4 is seen as a full-length (blue arrowheads) and truncated (yellow arrowheads) forms. B, Surface expression of the above-mentioned ectopic hβ4-fusion constructs. Indicated MDCK cell lines were surface biotinylated, followed by immunoprecipitation of Myc-tagged integrin β4 constructs by using Myc-antibodies. Surface-expressed proteins were visualized using streptavidin-HRP. Endogenous integrin α6 coimmunoprecipitating with hβ4 and hβ4-BirA constructs is indicated in the blot. C, Coimmunofluorescence staining of Myc-tagged hβ4, hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 (green) with endogenous integrin α6 (red) by TIRF microscopy. D, Colocalization between the different hβ4 constructs and endogenous integrin α6 measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (Mean ± S.D., n = 16–20 images from three experiments). Statistical significance was determined with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s post hoc test (*p < 0.05). E, Biotinylated proteins were visualized in hβ4-, hβ4-BirA- and BirA-hβ4-expressing MDCK cells by SDS-PAGE followed by blotting with streptavidin-HRP (left panel). Equal loading was confirmed by ponceau staining (right panel) F, Coomassie staining of streptavidin-precipitated biotinylated proteins. G, Costaining of endogenous integrin α6 (green) and biotinylated proteins (red) in hβ4-BirA- and BirA-hβ4-expressing MDCK cells imaged with TIRF microscopy in the presence or absence of biotin. H, Colocalization was measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (Mean ± S.D., n = 16–26 images from three experiments). Scale bars = 10 μm.

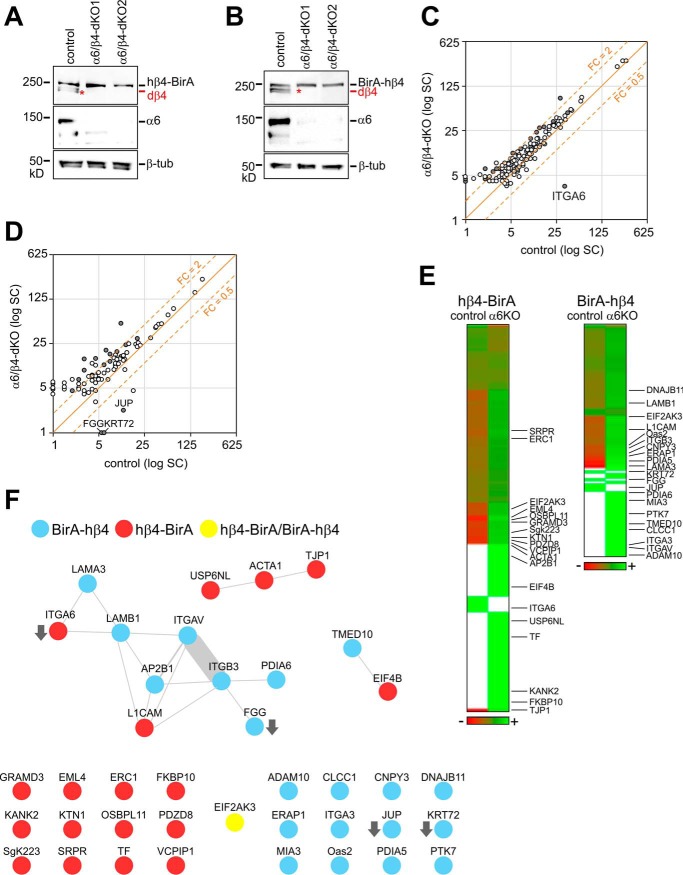

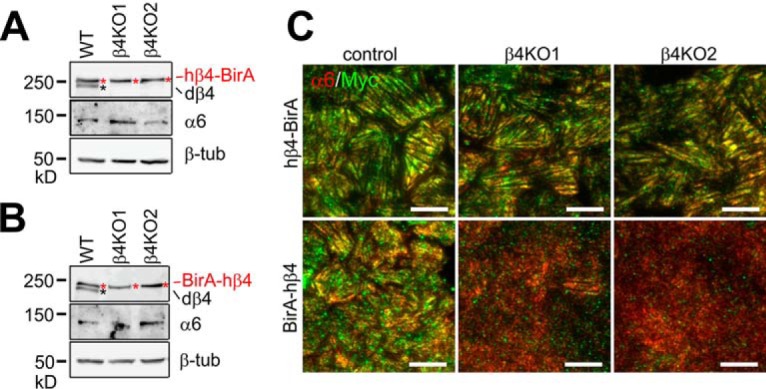

It is possible that endogenous β4-integrins competes with ectopic β4-fusion constructs for binding to α6-subunit potentially limiting the targeting of β4-fusions to MDCK-HDs. To facilitate efficient biotinylation of HD-associated β4-interactome, we knocked out the endogenous canine β4-integrin (β4KO) using lentivirus-mediated clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 system in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 MDCK cells (Fig. 3A and 3B, endogenous dog integrin β4 marked by a black asterisk). We found that only hβ4-BirA was targeted to MDCK-HDs in the absence of endogenous integrin β4 (Fig. 3C). Impaired HD-targeting of BirA-β4 in β4-KO MDCK cells probably relates to its inability to interact with α6-integrin (Fig. 2B). Despite the lack of efficient HD-targeting of N-terminally tagged hβ4, analysis of BirA-hβ4-interactome may nevertheless reveal novel proteins involved in the regulation of β4-integrin folding and trafficking.

Fig. 3.

Deletion of endogenous integrin β4 impairs HD targeting of BirA-hβ4. A–B, Knockout of endogenous β4 integrin (dβ4, black asterisk) in MDCK cells expressing hβ4-BirA (red asterisks in A) and BirA-hβ4 (red asterisks in B) was confirmed by Western blotting using integrin β4-antibodies. Integrin α6 expression levels were also determined and β-tubulin blotting was used as a loading control. C, Colocalization of endogenous α6-integrin (red) with exogenous myc-tagged hβ4-BirA (green, upper panels) or BirA-hβ4 (green, lower panels) was analyzed by TIRF microscopy. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Identification of the β4-integrin Interactome

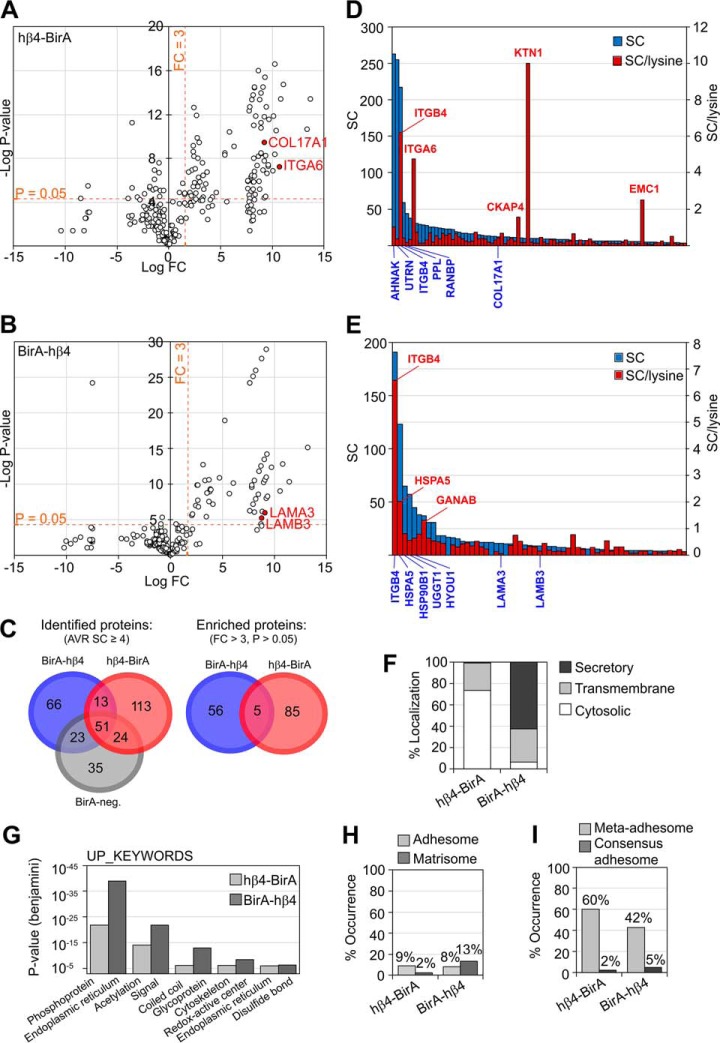

Biotinylated proteins were Strep-Tactin-precipitated and subjected to LC-MS/MS for identification and label-free quantification based on spectral counting. Specific enrichment of proteins in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 samples relative to the BirA-negative control was visualized by volcano blots (Fig. 4A and 4B). Total of 90 and 61 proteins were more than 3-fold enriched in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4, respectively (Fig. 4C and supplemental Table S1). For validation of the filtering efficiency (identification of high-confidence interactors) N-terminally BirA-tagged GFP (BirA-GFP) and myristoylated C-terminally BirA-tagged GFP (myr-GFP-BirA) were used as additional controls (supplemental Fig. S2D–S2F). All the pre-filtered β4-interactome proteins were significantly enriched also when compared with BirA-GFP- and myrGFP-BirA interactomes, suggesting that unspecific labeling is not a concern in our BioID experiment (supplemental Table S2, supplemental Fig. S2E–S2F). This was further corroborated by analyzing the β4-interactome against the Contaminant Repository for Affinity Purification (CRAPome) database that contains lists of most common contaminants found in negative controls of mainly affinity purification-based MS-analyses (38). Only limited overlap was noted and the pre-filtered β4-interacting proteins were rarer and less abundant in CRAPome data sets compared with those removed by filtering (supplemental Fig. S2A–S2B). Finally, comparative analysis of the pre-filtered β4-interactome with other BioID-based interactomes of several cell-cell junctional proteins strongly suggests that the biotinylated proteins in hβ4-BirA- and BirA-hβ4-expressing cells represent a specific set of proteins that interact with β4-integrin (supplemental Fig. S2C) (39–41).

Fig. 4.

Interactomes of C- and N-terminally tagged integrin-β4 identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS. Volcano blots of hβ4-BirA (A) and BirA-hβ4 (B) labeled proteins whose SC is > 4 in the respective samples. C, Venn diagrams of all the proteins identified in hβ4-BirA, BirA-hβ4 and negative control samples (Identified proteins), and of proteins that were specifically enriched in hβ4-BirA (A) and BirA-hβ4 (B) samples (FC > 3, p value < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t test) indicated by dotted lines). D–E, Enriched proteins were ranked by total SC or by counts per the number of lysines available for biotinylation for both hβ4-BirA (D) or BirA-hβ4 (E). Only cytosolic or luminal sequences of the longest canine protein product (UniProt) were used for the counting of lysines in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 -enriched proteins, respectively. If membrane topology data was not available, domains were estimated based on alignment to the corresponding human sequence with known domain information. F, Distribution of hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 biotinylated proteins between cytosolic compartment and secretory pathway based on UniProt entry information. G, Enrichment of non-redundant sequence features and protein domains between hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 biotinylated proteins analyzed by DAVID. H, Occurrence of literature-curated adhesome (42) and matrisome components (63) and I, components identified from purified adhesions by mass spectrometry (6) within the interactomes of integrin β4.

Only 5 proteins were shared between hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4, which is consistent with the biotin ligase activities being restricted to different cellular compartments. Enriched proteins were ranked based on total spectral count (SC) values and SC values normalized to the number of available lysine residues, which is a factor, along with protein copy number and proximity that defines labeling efficiency (Fig. 4D and 4E, supplemental Table S1). It is likely that large cytosolic proteins with multiple available biotinylation sites are overrepresented when compared with targets containing fewer available lysines, such as the short cytoplasmic tail of α6-integrin. Human integrin β4 was ranked in the top 3 in both hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 samples, suggesting that proximity translates into high ranking. In hβ4-BirA samples, the other top ranking proteins, based on total SC, were large junctional scaffold proteins AHNAK, Utrophin (UTRN) and periplakin (PPL). However, when normalized SCs were used, α6-integrin and integral membrane proteins, kinectin 1 (KTN1) and cytoskeleton associated protein 4 (CKAP4), ranked in the top (Fig. 4D). For BirA-hβ4, the top-ranking proteins, based on both total and normalized SCs, were ER-resident proteins involved in protein folding and glycosylation (Fig. 4E). The well-known HD component collagen XVII/BP180/BPAG2 (COL17A1) was moderately ranked in hβ4-BirA interactome (Fig. 4A and 4D) whereas two other HD components laminin chains α3 and β3 were moderately ranked (LAMA3 and LAMB3 in Fig. 4B and 4E) in BirA-hβ4 samples. Curiously, plectin was identified from all analyzed samples, including negative controls. Thus, it was not enriched in β4-interactome although we did show clear colocalization between plectin and α6-integrin (Fig. 1E, 1H).

Consistent with the subcellular localization of the biotin ligase domain, proteins enriched in hβ4-BirA samples were mostly cytosolic, whereas those enriched in BirA-hβ4, were proteins destined to the secretory pathway (Fig. 4F). Moreover, hβ4-BirA interactome was enriched with sequence features and domains associated with cytosolic proteins, whereas BirA-hβ4 proximal interactors where enriched with motifs found in secretory proteins (Fig. 4G). These results suggest that labeling is restricted to the appropriate subcellular compartment. About 8–9% of the proximal interactors in hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 belonged to the literature-curated adhesome (42), whereas, as expected, BirA-hβ4 labeled more proteins belonging to the literature-curated matrisome than hβ4-BirA (Fig. 4H) (43). Sixty percent of hβ4-BirA- and 42% of BirA-hβ4-enriched proteins belonged to the meta-adhesome, which is a collection of proteins identified from isolated FAs by mass spectrometry (Fig. 4I) (6). Two percent (hβ4-BirA) and 5% (BirA-hβ4) belonged to the consensus adhesome that represents the core components common to FAs isolated from various sources (Fig. 4I) (6).

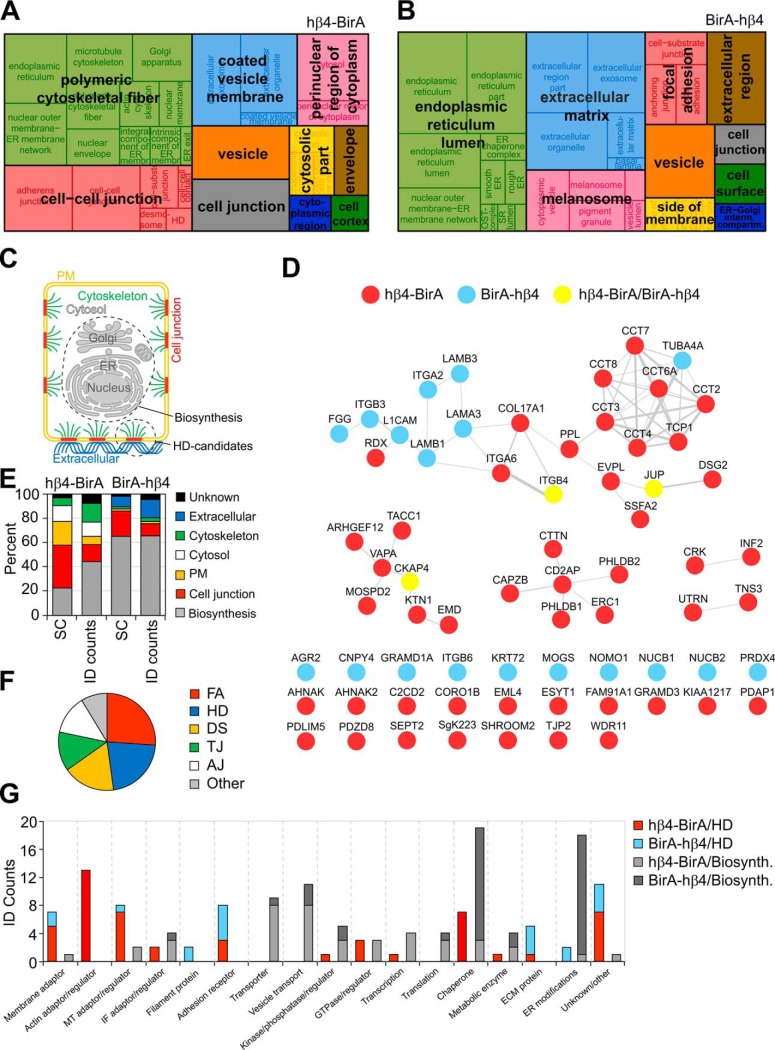

Bioinformatic Analysis of MDCK-HD Associated β4-interactome

Although the core HD components have been studied in detail in keratinocytes (44–46), the interaction landscape remains relatively unexplored in simple epithelial cells. Here we performed biotinylation of β4-interacting proteins in steady state conditions, and thus the β4-interactome is expected to contain components interacting with both maturing β4-complexes during their biosynthetic transport and with the mature α6β4-integrin at the cell surface and in endocytic compartments. The enrichment of GO terms within the interactome was visualized using REVIGO (Fig. 5A and 5B) (30). hβ4-BirA-labeled proteins fell under terms such as polymeric cytoskeletal fiber, cell-cell junction, coated vesicle membrane and perinuclear region of cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). ER lumen was the most overrepresented term among BirA-hβ4-enriched proteins, but terms for secreted components such as extracellular matrix and cell surface, as well as focal adhesion, also emerged (Fig. 5B). Thus, the analysis of subcellular localization of proximity-labeled proteins suggests that both hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 mature, although BirA-hβ4 matures with only low efficiency.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of the HD candidate proteins in the β4-integrin interactome. A–B, hβ4-BirA (A) and BirA-hβ4 (B) enriched cell component GO terms were extracted from DAVID and non-redundant terms visualized with REVIGO treemap with the block size corresponding to the number of proteins. C, Identified proximal proteins were assigned into different subcellular compartments in order to resolve potential HD candidates (colored) from biosynthesis-related proteins (gray). D, HD candidates were represented as a protein-protein interaction network and arranged based on protein complexes where applicable. Weights of the node-connecting lines reflect the number of publications reporting the interaction. E, Representation of proteins in different subcellular compartments relative to total SC and ID counts. F, Occurrence of established junctional proteins within the integrin β4 proximal proteins based on UniProt keywords (FA - focal adhesion; HD - hemidesmosome; DS - desmosome; TJ - tight junction; AJ - adherens junction). G, Manual curation of proximal proteins into functional categories based on UniProt entry and literature search.

To facilitate protein-protein interaction analysis of potential HD-associated proteins, we classified proteins into groups based on their annotated subcellular localizations (Fig. 5C). The HD localized proteins were manually curated based on the literature and their UniProt entries and then assigned into 6 different groups according to their subcellular compartment (Fig. 5E and (supplemental Table S3). Proteins that localized to the nucleus, ER, Golgi or mitochondria were classified into a biosynthesis group and proteins, for which there was no information available concerning their subcellular localization, were put into a group named unknown (Fig. 5E). In agreement with the observed defective maturation and HD targeting of BirA-hβ4, SC-based analysis revealed that more than 60% of proteins in the BirA-hβ4 complex belonged to the biosynthesis-related group whereas this group constituted less than 30% of total SCs in hβ4-BirA interactome (Fig. 5E). Members of the biosynthesis group were involved in folding, ER modifications, translation, post-translational modifications and vesicular transport (Fig. 5G and supplemental Table S3).

The second largest and abundant BirA-hβ4-associated group after the biosynthesis group was the extracellular protein group that included several laminin chains that were also shown to colocalize with α6β4-integrin (Fig. 1C, 1D, 1H and 5E). In hβ4-BirA samples, plasma membrane and cell junction groups containing the highest-ranking proteins were most prominent in total SCs (Fig. 5E). Based on UniProt keywords, the junctional proteins found in putative MDCK-HDs were designated as components of FAs, HDs, desmosomes (DS), tight junctions (TJ) and adherens junctions (AJ) (Fig. 5F). This is not unexpected as proteins can be shared between different types of junctions and adhesions. However, whether these proteins truly localize to HDs, needs to be validated case-by-case. Components mediating cell-ECM interactions, especially those involved in laminin-adhesion, are likely to be very closely positioned to HDs. The cytoskeletal proteins included several actin and microtubule-interacting proteins with regulatory or structural functions. Most of the keratins that were identified by mass spectrometry mapped to the human protein sequence and were therefore not considered specific.

To focus the PPI network analysis on proteins that localize to MDCK-HDs we decided to exclude the biosynthesis group from the analysis. The remaining putative HD-associated proteins were mapped to the human interactome and represented as protein-protein interaction networks (Fig. 5D). hβ4-BirA was better represented overall, but BirA-hβ4 contributed to the extracellular region and cell junction parts of the network. Proteins involved in the formation of laminin-based adhesions and known to interact with the intermediate filament network formed the most notable subnetwork that also included α6β4-integrin (Fig. 5D). Chaperonin Containing TCP1 (CCT) complex that assist folding and stabilization of diverse group of newly-made cytosolic proteins was also linked with this network (Fig. 5D) (47). Interestingly, three smaller nodes were found that represented actin-binding proteins and one node with proteins that associate with dystroglycan (DSG)-mediated laminin adhesions that in turn are known to connect to the actin cytoskeleton. More than one third of the proteins were not incorporated into any PPI-network in the analysis (Fig. 5D). Profiling of the MDCK-HD candidate proteins based on their functions highlighted the presence of membrane- and cytoskeleton-associated adaptors and regulators, receptors and ECM proteins (Fig. 5G and supplemental Table S3).

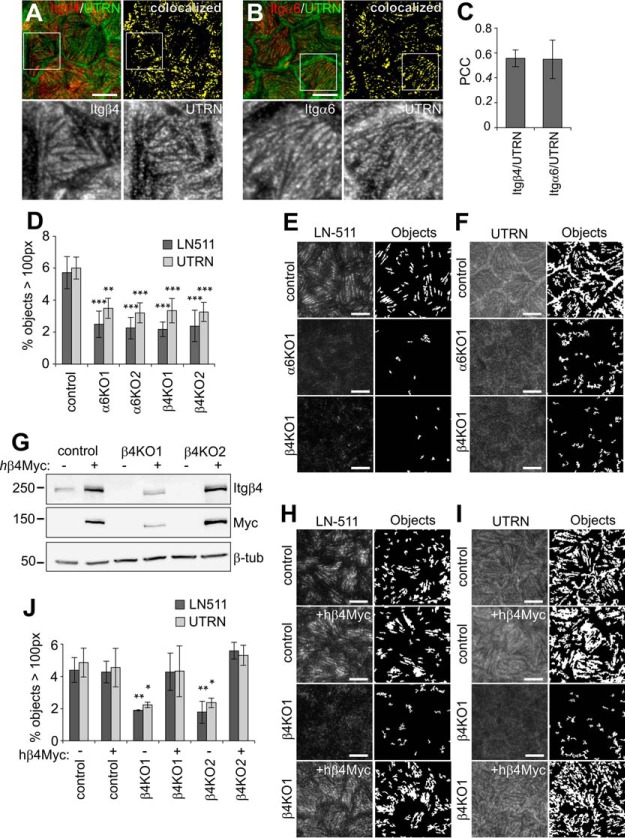

Integrin α6β4 Recruits Utrophin to MDCK-HDs Whereas Basal Localization of ERC1 Is Independent of Integrin α6β4 Expression

To validate if the proximally labeled proteins localize to HDs, we picked two candidate proteins that were efficiently labeled in hβ4-BirA expressing cells: Utrophin (UTRN) and ELKS/RAB6-interacting/CAST family member 1 (ERC1). UTRN was found to colocalize with α6- and β4-integrins in MDCK-HDs based on TIRF microscopy (Fig. 6A–6C). Importantly, HD-targeting of UTRN was abrogated in both α6- and β4-KO MDCK cells (Fig. 6D–6F). When Myc-tagged human integrin β4 was expressed in β4KO cells (Fig. 6G), the basal laminin assembly (Fig. 6H) and targeting of UTRN to MDCK-HDs (Fig. 6I) could be fully rescued (Fig. 6J). These data show that integrin α6β4 expression is critical for UTRN targeting to HDs. α6β4-integrins could recruit UTRN via direct interaction but because UTRN has been reported to associate with another laminin receptor, dystroglycan (DG) (48), it is also possible that α6β4-integrin-driven laminin assembly at HDs indirectly leads to DG-mediated UTRN recruitment (Fig. 6E and 6F). To study the HD-targeting of UTRN in more detail, we generated DG-knockdown (KD) MDCK cells. We found that UTRN recruitment was abrogated in DGKD cells (supplemental Fig. S3A and S3C). Moreover, basal laminin assembly was disrupted in DGKO cells (supplemental Fig. S3B and S3C), suggesting that proper laminin organization depends on both α6β4-integrin and DG. These results support a model where integrin α6β4 and DG synergistically assemble basal laminin network and thereby recruit UTRN to the forming HDs (49, 50).

Fig. 6.

HD-formation and HD-targeting of utrophin depends on integrin α6β4. A–B, TIRF images showing coimmunostaining of integrins β4 (A) and α6 (B) (red) with utrophin (UTRN, green). Colocalized pixels are shown as bitmaps (yellow). C, Colocalization of α6 and β4 integrins with UTRN measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (n = 12–15 images from three experiments). D, Quantification of segmented objects (>100 pixels; n = 16–32 images from 3–5 experiments were analyzed) from TIRF images of control, α6- and β4-KO cells stained for E, LN-511 and F, utrophin. G, Western immunoblot showing expression of Myc-tagged hβ4 in control and β4KO cells. H–I, TIRF-images and corresponding bitmaps of segmented laminin-511 (H) and UTRN (I) objects (>100 pixels) in control and β4KO cells with and without expression of hβ4. J, Quantification of segmentation data from H and I (n = 11–25 images from 3–5 experiments). Statistical significance tested with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s or Games-Howell′s (UTRN in J) post hoc test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Scale bars = 10 μm.

Similar to UTRN, ERC1 was found to colocalize with both integrin β4 and α6 in mature HDs in confluent MDCK cells (Fig. 7A–7C). ERC1, together with two other novel β4-interactome candidates, PHLDB1 and PHLDB2, participate in a protein complex containing KANK2 that has been show to activate β1-integrins but to reduce force transmission across FAs (51, 52). Interestingly, deleting integrin α6 or β4 expression had no significant effect on the basal localization of ERC1 (Fig. 7D and 7E). In subconfluent cells, ERC1 displayed partial colocalization with both HD-forming integrin β4 and an FA component vinculin (VCL, Fig. 7F–7H). Therefore, ERC1 appears to be recruited to the membrane independently of α6β4 integrins and could, in principle, be necessary for the recruitment of integrin-α6β4 to nascent laminin adhesions prior to HD assembly.

Fig. 7.

Basal targeting of ERC1 is independent of integrin α6β4 expression. A–B, TIRF images showing coimmunostaining of integrins β4 (A) and α6 (B) (red) with ERC1 (green). Colocalized pixels are shown as bitmaps (yellow). C, Colocalization of α6 and β4 integrins with ERC1 measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (n = 12–15 images from three experiments). D, TIRF images and corresponding bitmaps of segmented ERC1 objects (>100 pixels) in control, α6KO and β4KO cells. E, Quantification of ERC1 objects (n = 15–18 images from three experiments). F–G, TIRF images showing coimmunostaining of integrin β4 (F) and vinculin (VCL, G, (green) with ERC1 (red). Colocalized pixels are shown as bitmaps (yellow). H, Colocalization of β4 integrin and VCL with ERC1 measured by Pearson's correlation coefficient (n = 10 images from two experiments). Statistical significance was tested with one-way analysis of variance using Tukey′s or Games-Howell′s (ERC1 in E) post hoc test (not significant). Scale bars = 10 μm.

UTRN and ERC1 Are Both Dispensable for HD Formation in MDCK Cells

To study the possible role of ERC1 and UTRN in biogenesis of MDCK-HDs we knocked out their expression by using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Efficient depletion of UTRN was demonstrated by Western blotting (Fig. 8C). Significant down-regulation of ERC1 protein was also evident in all five different ERC1-KO MDCK cell lines (Fig. 8D). UTRN-KO and ERC1-KO MDCK cells did not display any significant defect in their ability to assemble HDs as judged by formation of integrin-α6 and -β4 positive foci (Fig. 8A, 8B, and 8E). These results indicate that neither UTRN nor ERC1 is essential for the HD-assembly.

Fig. 8.

Utrophin and ERC1 are dispensable for HD targeting of integrin α6β4. A–B, TIRF images of integrin α6 (A) and β4 (B) in control, UTRNKO and ERC1KO MDCK cells. Bitmaps showing segmentations of objects that are bigger than 100 pixels (right panels). C, Western immunoblots showing knockout of Utrophin in MDCK cells. D, Knockout efficiency of ERC1 analyzed by western immunoblotting. E, Quantification of segmented objects in UTRN- and ERC1-KO MDCK cells (n = 20–34 images/four experiments for α6 and 8–9 images/two experiments for β4). Scale bars = 10 μm.

Proximal Interactions of Integrin β4 Are Independent of the Formation of α6β4-Heterodimer

Formation of an αβ-heterodimer is considered a prerequisite for the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-exit and subsequent surface delivery of integrins (53). In order to study how α6β4-heterodimerization affects the composition of β4-interactome, we generated MDCK cells expressing either hβ4-BirA or BirA-hβ4 fusion protein but lacking expression of endogenous β4- and α6-integrins (α6/β4-dKO) (Fig. 9A and 9B). In principle, lack of α6-subunit should block maturation of both hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4. Biotinylated samples were collected from hβ4-BirA and BirA-hβ4 cells in the presence (control), or absence (α6/β4-dKO) of α6-integrin. Samples from cells without BirA-expression were used as a negative control. It is expected that depletion of integrin-α6 leads to ER retention of both β4-BirA and BirA-β4 fusion constructs, thereby preventing the association of proteins interacting with the mature integrin β4 and instead preferentially revealing interactions associated with the biosynthetic trafficking and folding of integrin β4. Increased SC were indeed observed for a few ER-resident β4-interacting proteins, such as Protein Disulfide Isomerase A5 (PDIA5), PDIA6, Signal Recognition Particle Receptor (SRPR) and FK506 Binding Protein 10 (FKBP10) peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase in the β4-interactome of α6KO cells when compared with controls (supplemental Table S4). To our surprise, however, only four proteins (including the depleted α6-integrin) displayed significantly reduced interaction with integrin-β4 in α6KO cells (Fig. 9C and 9D). Moreover, the SC of the labeled proteins between α6KO and control samples suggested no major change in the abundance of the vast majority of β4-interacting proteins (Fig. 9C and 9E). This suggests that the proximal interactions of β4-integrin remain largely unchanged despite the absence of α6-integrin.

Fig. 9.

Efficient assembly of integrin β4 interactome in integrin α6 knockout MDCK cells. Knockout of α6 integrin subunits in MDCK β4-KO cells expressing hβ4-BirA (A) and BirA-hβ4 (B) was confirmed by Western blotting. Endogenous dog integrin-β4 (dβ4) is indicated by a red asterisk. C–D, Scatter blots showing average SC of hβ4-BirA (C) and BirA-hβ4 (D) enriched proteins in control and α6/β4-dKO cells with significantly changed genes (p < 0.05; unpaired two-tailed t test) labeled gray. E, Heatmap comparing protein abundances between control and α6KO samples based on normalized average SCs (green corresponds to lower and red to higher levels). Proteins included are those found specific in either or both samples (proteins not enriched are labeled in white) and significantly changed proteins are indicated by gene symbols. F, Interactions reported in PINA, iRefWeb, IntAct and BioGRID resources for proteins found significantly changed in KO versus control samples. Weights of the node-connecting lines reflect the number of publications reporting the interaction.

Several β4-interacting proteins involved in the formation and regulation of actin-linked FAs displayed increased SCs in α6KO cells. When the β4-interacting proteins with significantly differing SCs in α6KO cells were mapped to the human interactome and represented as protein-protein interaction networks, two nodes were obtained, one centering on αVβ3-integrin and another representing an actin-linked junctional module (Fig. 9F). In addition, integrin-α3, ERC1, KANK2 and KTN1, all of which have been implicated in FA regulation, were among the proteins preferentially interacting with integrin-β4 in the absence of α6-subunit (Fig. 9E, supplemental Table S4).

DISCUSSION

Recent advancement in mass spectrometry analyses has enabled comprehensive proteomic characterization of various protein complexes, including cellular adhesions. The HD composition has been previously interrogated only by using traditional methods (11). Here we used BirA-based proximity biotinylation (BioID) technology to analyze the interactome of β4-integrin, a core component of laminin-adhering HDs. The BioID approach does not rely upon preservation of the protein-protein interactions throughout the adhesion purification procedure. This is particularly advantageous for the study of cell adhesion complexes that are notoriously difficult to preserve (7). It was noted, however, that fusing the BirA domain to the N terminus of β4-integrin affected its delivery to HD-like basal patches. Although reduced basal targeting likely limits efficient labeling of β4-interacting proteins at HDs, the BirA-β4-integrin construct revealed proteins that interact with β4-integrin in the ER and may be critical for its biosynthetic trafficking. Less than 5% of the proteins identified as potential β4-integrin interacting components of HDs are shared with the previously reported core consensus adhesome (6). The core consensus adhesome has been established by combining results from selected proteomic analyses of FAs isolated using mechanical and biochemical techniques (7). The limited overlap seen between the core consensus adhesome and β4-BioID-interactome is not surprising given that FAs and HDs are distinct complexes. Moreover, as the source cell type and the adhesion purification methods are different, drawing direct comparisons is problematic. Indeed, when Dong and colleagues employed the BioID-technology to characterize the interactomes of kindlin-2 and paxillin, two key components of FAs, they found that only 22% of their interactomes were included in the core consensus adhesome (54). Curiously, only one third of the proteins labeled in paxillin- and kindlin-2-BirA fusion protein expressing cells were common to both constructs suggesting that, when properly optimized, BioID labeling is strictly limited to proteins in the immediate vicinity of the BirA domain (54).

In our BioID-based β4-integrin interactome, we did identify some components previously associated with FAs, which may also mediate laminin interactions. Among the FA components were two β1-integrin binding proteins tensin-3 and a recently described talin activating protein KANK2 whose interaction with integrin-β4 was enhanced in α6KO cells (52, 55, 56). The α6β4-integrin staining did not overlap with the most intensive talin staining (Fig. 1F). However, the strongly talin-positive FAs we observed linked with stress fibers may not represent laminin-binding adhesions at all. Indeed, we observed partial colocalization of β1-integrins with α6-integrins in MDCK-HDs that were mutually exclusive for FA markers (Fig. 1B, 1F, 1G). Despite limited overlap, FA and HD patterns flanked each other tightly. Thus, it is expected that some molecular connections exist between these two structures and in the absence of functional HDs, such as in α6KO cells, remaining HD components may be relocated to FAs (Fig. 9F).

We also investigated a couple of the highly ranked hits, ERC1 and UTRN, for their potential roles in laminin adhesions in more detail. ERC1 was recently reported to regulate FA turnover in a complex with Liprin-α1 and LL5 (57). The LL5 complex in turn associates with integrin-mediated laminin adhesions in mammary epithelial cells, where it supposedly plays a role in the capture microtubules (58). Both LL5 isoforms, LL5α (PHLDB1) and LL5β (PHLDB2) were also identified in our β4-interactome. UTRN on the other hand is a homolog of dystrophin and is thought to link DG-mediated laminin adhesions to the actin cytoskeleton in non-muscle cells (48). We verified the localization of both ERC1 and UTRN at MDCK-HDs, but neither was an essential HD component as MDCK-HDs did form in UTRNKO and ERC1KO cells. It is thus more likely, that these proteins are accessory components rather than essential structural components. Our data show that in polarized cells ERC1 preferentially associates with HDs but in subconfluent cells it appears to be linked to both FAs and HDs. A potential role for ERC1 in orchestrating coordinated assembly of FAs and HDs is an interesting topic for further studies. The core structural components, at least in type I HDs, have been listed and their interactions precisely defined (11). From these core components, our screen picked up collagen XVII, laminin chains α3 and β3 and integrin α6. The absence of the other components may be related to the structural differences seen between type I and II HDs and thus further investigation is necessary.

The HD-like laminin patches we observed in MDCK cells were not only dependent on α6β4-integrins, but also on DG expression. Moreover, the role of β1-integrins in laminin assembly in MDCK cells has been previously suggested (3). Therefore, it is possible that these patches that we introduce as MDCK-HDs have a more integrated nature, containing several closely-associated laminin-binding receptor complexes. This could be one possible explanation as to why we identified components known to reside in both FAs and the DG complex in our integrin β4 interactome. Indeed, we confirmed that the recruitment of UTRN to laminin adhesions was dependent on both α6β4-integrins and DG. Clearly, further scrutiny and comparative analyses of the coexpressed laminin-binding receptor complexes is needed to resolve their individual contributions to laminin adhesion and signaling.

The most surprising finding of our study was that deletion of α6-integrin expression did not significantly affect the assembly of β4-integrin interactome. It is likely that β4-integrins alone are not able to form robust laminin adhesions. Indeed, efficient assembly of HD-associated laminin patches in the ECM was dependent on α6β4-integrin heterodimer expression, which agrees with mouse studies demonstrating that α6-deletion leads to loss of functional HDs and results in lethal fragility in epithelial tissues (59). However, β4-integrin, that does not form a heterodimer with α6-integrin, could still interact with multiple cytoplasmic effectors and associate with the intermediate filament network (60). Previous data have shown that integrin β4 is expressed in excess relative to α6-integrin (61). The potential relevance of β4-integrin complexes that do not contain α6-subunit merits further investigation. Interestingly, mutations in the integrin β4 gene contribute to epidermolysis bullosa, a genetic skin blistering disease caused by defective HDs, much more frequently than those in the integrin α6 gene (62).

In conclusion, we provide here the first comprehensive characterization of β4-integrin interactome in simple epithelium. We demonstrate that β4-integrin can associate with most of its proximal interactors, such as UTRN and ERC1, two novel β4-associated proteins, independently of α6-integrin expression. This interactome serves as valuable resource and as such provides interesting insight into the molecular characteristics of the assembly of HDs in simple epithelia.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The MS data, thermo.raw files, spectral libraries (msf-files), and converted mgf-formats for all the above runs are available in a publicly accessible PeptideAtlas raw data repository (http://www.peptideatlas.org/PASS/PASS01198) with deposite ID:PASS01198.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Riitta Jokela for overall expert technical assistance, Jaana Träskelin for expert technical assistance at Biocenter Oulu Virus Core Laboratory, Dr. Veli-Pekka Ronkainen for expert assistance in microscopy at Biocenter Oulu Tissue Imaging Center and Dr. Ulrich Bergmann for expert assistance in MALDI/TOF analysis at Biocenter Oulu Mass spectrometry Core Laboratory.

Footnotes

* This work was funded by Academy of Finland (251314, 135560, 263770, and 140974/AM).

This article contains supplemental material. We declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental material. We declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- BioID

- proximity-dependent biotin identification

- BirA

- biotin ligase

- Cas9

- CRISPR associated protein 9

- CKAP4

- cytoskeleton associated protein 4

- CRISPR

- clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DG

- dystroglycan

- ERC1

- ELKS/Rab6-interacting/CAST family member 1

- FA

- focal adhesion

- FKBP10

- FK506 binding protein 10

- HD

- hemidesmosome

- KANK2

- KN motif and ankyrin repeat domains 2

- KO

- knockout

- KTN1

- kinectin 1

- LAMA

- laminin α-chain

- LAMB

- laminin β-chain

- LN

- laminin

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- PPL

- periplakin

- PDIA5and6

- protein disulfide isomerase A5and6

- SC

- spectral count

- SRPR

- signal recognition particle receptor

- TIRF

- total internal reflection microscopy

- UTRN

- utrophin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hohenester E., and Yurchenco P. D. (2013) Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell. Adh. Migr. 7, 56–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matlin K. S., Myllymäki S. M., and Manninen A. (2017) Laminins in epithelial cell polarization: old questions in search of new answers. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a027920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Brien L. E., Jou T. S., Pollack A. L., Zhang Q., Hansen S. H., Yurchenco P., and Mostov K. E. (2001) Rac1 orientates epithelial apical polarity through effects on basolateral laminin assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 831–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Humphries J. D., Byron A., and Humphries M. J. (2006) Integrin ligands at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3901–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geiger T., and Zaidel-Bar R. (2012) Opening the floodgates: proteomics and the integrin adhesome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 562–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horton E. R., Byron A., Askari J. A., Ng D. H., Millon-Fremillon A., Robertson J., Koper E. J., Paul N. R., Warwood S., Knight D., Humphries J. D., and Humphries M. J. (2015) Definition of a consensus integrin adhesome and its dynamics during adhesion complex assembly and disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 1577–1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manninen A., and Varjosalo M. (2017) A proteomics view on integrin-mediated adhesions. Proteomics 17, 1600022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brakebusch C., and Fassler R. (2005) β1 integrin function in vivo: adhesion, migration and more. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 24, 403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rodriguez-Fraticelli A. E., and Martin-Belmonte F. (2014) Picking up the threads: extracellular matrix signals in epithelial morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 30, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu W., Datta A., Leroy P., O'Brien L., Mak E. G., Jou T. S., Matlin K. S., Mostov K. E., and Zegers M. M. (2005) β1-Integrin Orients Epithelial Polarity via Rac1 and Laminin. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 433–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walko G., Castanon M. J., and Wiche G. (2015) Molecular architecture and function of the hemidesmosome. Cell Tissue Res. 360, 529–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uematsu J., Nishizawa Y., Sonnenberg A., and Owaribe K. (1994) Demonstration of type II hemidesmosomes in a mammary gland epithelial cell line, BMGE-H. J. Biochem. 115, 469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Myllymäki S. M., Teräväinen T. P., and Manninen A. (2011) Two distinct integrin-mediated mechanisms contribute to apical lumen formation in epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 6, e19453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weaver V. M., Lelievre S., Lakins J. N., Chrenek M. A., Jones J. C., Giancotti F., Werb Z., and Bissell M. J. (2002) β4 integrin-dependent formation of polarized three-dimensional architecture confers resistance to apoptosis in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Cancer Cell. 2, 205–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamill K. J., Hopkinson S. B., DeBiase P., and Jones J. C. (2009) BPAG1e maintains keratinocyte polarity through β4 integrin-mediated modulation of Rac1 and cofilin activities. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2954–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roux K. J., Kim D. I., and Burke B. (2013) BioID: a screen for protein-protein interactions. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 74, 19.23.1–19.23.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teräväinen T. P., Myllymäki S. M., Friedrichs J., Strohmeyer N., Moyano J. V., Wu C., Matlin K. S., Muller D. J., and Manninen A. (2013) αV-integrins are required for mechanotransduction in MDCK epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 8, e71485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rizk A., Paul G., Incardona P., Bugarski M., Mansouri M., Niemann A., Ziegler U., Berger P., and Sbalzarini I. F. (2014) Segmentation and quantification of subcellular structures in fluorescence microscopy images using Squassh. Nat. Protoc. 9, 586–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schoenenberger C. A., Zuk A., Zinkl G. M., Kendall D., and Matlin K. S. (1994) Integrin expression and localization in normal MDCK cells and transformed MDCK cells lacking apical polarity. J. Cell Sci. 107, 527–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis T. L., Rabinovitz I., Futscher B. W., Schnolzer M., Burger F., Liu Y., Kulesz-Martin M., and Cress A. E. (2001) Identification of a novel structural variant of the α6 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26099–26106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyballa N., and Metzger S. (2009) Fast and sensitive colloidal coomassie G-250 staining for proteins in polyacrylamide gels. J. Vis. Exp. 30, 1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ulrich A., Andersen K. R., and Schwartz T. U. (2012) Exponential megapriming PCR (EMP) cloning-seamless DNA insertion into any target plasmid without sequence constraints. PLoS ONE 7, e53360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roux K. J., Kim D. I., Raida M., and Burke B. (2012) A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 196, 801–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dans M., Gagnoux-Palacios L., Blaikie P., Klein S., Mariotti A., and Giancotti F. G. (2001) Tyrosine phosphorylation of the β4 integrin cytoplasmic domain mediates Shc signaling to extracellular signal-regulated kinase and antagonizes formation of hemidesmosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1494–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yadav L., Tamene F., Goos H., van Drogen A., Katainen R., Aebersold R., Gstaiger M., and Varjosalo M. (2017) Systematic analysis of human protein phosphatase interactions and dynamics. Cell. Syst. 4, 430–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shalem O., Sanjana N. E., Hartenian E., Shi X., Scott D. A., Mikkelsen T. S., Heckl D., Ebert B. L., Root D. E., Doench J. G., and Zhang F. (2014) Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cattavarayane S., Palovuori R., Tanjore Ramanathan J., and Manninen A. (2015) α6β1- and αV-integrins are required for long-term self-renewal of murine embryonic stem cells in the absence of LIF. BMC Cell Biol. 16, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang K., Myllymäki S. M., Gao P., Devarajan R., Kytölä V., Nykter M., Wei G. H., and Manninen A. (2017) Oncogenic K-Ras upregulates ITGA6 expression via FOSL1 to induce anoikis resistance and synergizes with αV-Class integrins to promote EMT. Oncogene 36, 5681–5694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang da W, Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Supek F., Bosnjak M., Skunca N., and Smuc T. (2011) REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6, e21800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu J., Vallenius T., Ovaska K., Westermarck J., Makela T. P., and Hautaniemi S. (2009) Integrated network analysis platform for protein-protein interactions. Nat. Methods 6, 75–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cowley M. J., Pinese M., Kassahn K. S., Waddell N., Pearson J. V., Grimmond S. M., Biankin A. V., Hautaniemi S., and Wu J. (2012) PINA v2.0: mining interactome modules. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D862–D865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turner B., Razick S., Turinsky A. L., Vlasblom J., Crowdy E. K., Cho E., Morrison K., Donaldson I. M., and Wodak S. J. (2010) iRefWeb: interactive analysis of consolidated protein interaction data and their supporting evidence. Database 2010, baq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., and Ideker T. (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pavlidis P., and Noble W. S. (2003) Matrix2png: a utility for visualizing matrix data. Bioinformatics 19, 295–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mak G. Z., Kavanaugh G. M., Buschmann M. M., Stickley S. M., Koch M., Goss K. H., Waechter H., Zuk A., and Matlin K. S. (2006) Regulated synthesis and functions of laminin 5 in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3664–3677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Greciano P. G., Moyano J. V., Buschmann M. M., Tang J., Lu Y., Rudnicki J., Manninen A., and Matlin K. S. (2012) Laminin 511 partners with laminin 332 to mediate directional migration of Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 121–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mellacheruvu D., Wright Z., Couzens A. L., Lambert J. P., St-Denis N. A., Li T., Miteva Y. V., Hauri S., Sardiu M. E., Low T. Y., Halim V. A., Bagshaw R. D., Hubner N. C., Al-Hakim A., Bouchard A., Faubert D., Fermin D., Dunham W. H., Goudreault M., Lin Z. Y., Badillo B. G., Pawson T., Durocher D., Coulombe B., Aebersold R., Superti-Furga G., Colinge J., Heck A. J., Choi H., Gstaiger M., Mohammed S., Cristea I. M., Bennett K. L., Washburn M. P., Raught B., Ewing R. M., Gingras A. C., and Nesvizhskii A. I. (2013) The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Methods 10, 730–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fredriksson K., Van Itallie C. M., Aponte A., Gucek M., Tietgens A. J., and Anderson J. M. (2015) Proteomic analysis of proteins surrounding occludin and claudin-4 reveals their proximity to signaling and trafficking networks. PLoS ONE 10, e0117074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Itallie C. M., Aponte A., Tietgens A. J., Gucek M., Fredriksson K., and Anderson J. M. (2013) The N and C termini of ZO-1 are surrounded by distinct proteins and functional protein networks. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 13775–13788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Itallie C. M., Tietgens A. J., Aponte A., Fredriksson K., Fanning A. S., Gucek M., and Anderson J. M. (2014) Biotin ligase tagging identifies proteins proximal to E-cadherin, including lipoma preferred partner, a regulator of epithelial cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesion. J. Cell Sci. 127, 885–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winograd-Katz S. E., Fassler R., Geiger B., and Legate K. R. (2014) The integrin adhesome: from genes and proteins to human disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 273–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naba A., Clauser K. R., Ding H., Whittaker C. A., Carr S. A., and Hynes R. O. (2016) The extracellular matrix: Tools and insights for the “omics” era. Matrix Biol. 49, 10–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koster J., Geerts D., Favre B., Borradori L., and Sonnenberg A. (2003) Analysis of the interactions between BP180, BP230, plectin and the integrin α6β4 important for hemidesmosome assembly. J. Cell Sci. 116, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schaapveld R. Q., Borradori L., Geerts D., van Leusden M. R., Kuikman I., Nievers M. G., Niessen C. M., Steenbergen R. D., Snijders P. J., and Sonnenberg A. (1998) Hemidesmosome formation is initiated by the β4 integrin subunit, requires complex formation of β4 and HD1/plectin, and involves a direct interaction between β4 and the bullous pemphigoid antigen 180. J. Cell Biol. 142, 271–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sterk L. M., Geuijen C. A., Oomen L. C., Calafat J., Janssen H., and Sonnenberg A. (2000) The tetraspan molecule CD151, a novel constituent of hemidesmosomes, associates with the integrin α6β4 and may regulate the spatial organization of hemidesmosomes. J. Cell Biol. 149, 969–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yam A. Y., Xia Y., Lin H. T., Burlingame A., Gerstein M., and Frydman J. (2008) Defining the TRiC/CCT interactome links chaperonin function to stabilization of newly made proteins with complex topologies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1255–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Haenggi T., and Fritschy J. M. (2006) Role of dystrophin and utrophin for assembly and function of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex in non-muscle tissue. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1614–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sehgal B. U., DeBiase P. J., Matzno S., Chew T. L., Claiborne J. N., Hopkinson S. B., Russell A., Marinkovich M. P., and Jones J. C. (2006) Integrin β4 regulates migratory behavior of keratinocytes by determining laminin-332 organization. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35487–35498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weir M. L., Oppizzi M. L., Henry M. D., Onishi A., Campbell K. P., Bissell M. J., and Muschler J. L. (2006) Dystroglycan loss disrupts polarity and β-casein induction in mammary epithelial cells by perturbing laminin anchoring. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4047–4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bouchet B. P., Gough R. E., Ammon Y. C., van de Willige D., Post H., Jacquemet G., Altelaar A. M., Heck A. J., Goult B. T., and Akhmanova A. (2016) Talin-KANK1 interaction controls the recruitment of cortical microtubule stabilizing complexes to focal adhesions. Elife 5, e18124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sun Z., Tseng H. Y., Tan S., Senger F., Kurzawa L., Dedden D., Mizuno N., Wasik A. A., Thery M., Dunn A. R., and Fassler R. (2016) Kank2 activates talin, reduces force transduction across integrins and induces central adhesion formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ho M. K., and Springer T. A. (1983) Biosynthesis and assembly of the α and β subunits of Mac-1, a macrophage glycoprotein associated with complement receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 2766–2769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dong J. M., Tay F. P., Swa H. L., Gunaratne J., Leung T., Burke B., and Manser E. (2016) Proximity biotinylation provides insight into the molecular composition of focal adhesions at the nanometer scale. Sci. Signal. 9, rs4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCleverty C. J., Lin D. C., and Liddington R. C. (2007) Structure of the PTB domain of tensin1 and a model for its recruitment to fibrillar adhesions. Protein Sci. 16, 1223–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tadokoro S., Shattil S. J., Eto K., Tai V., Liddington R. C., de Pereda J. M., Ginsberg M. H., and Calderwood D. A. (2003) Talin binding to integrin β tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science 302, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Astro V., Tonoli D., Chiaretti S., Badanai S., Sala K., Zerial M., and de Curtis I. (2016) Liprin-α1 and ERC1 control cell edge dynamics by promoting focal adhesion turnover. Sci. Rep. 6, 33653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hotta A., Kawakatsu T., Nakatani T., Sato T., Matsui C., Sukezane T., Akagi T., Hamaji T., Grigoriev I., Akhmanova A., Takai Y., and Mimori-Kiyosue Y. (2010) Laminin-based cell adhesion anchors microtubule plus ends to the epithelial cell basal cortex through LL5α/β. J. Cell Biol. 189, 901–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]