Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia cepacia complex are poorly studied in Mexico. The genotypic analysis of 38 strains isolated from children with pneumonia were identified and showed that both Burkholderia groups were present in patients. From our results, it is plausible to suggest that new species are among the analyzed strains.

Keywords: Burkholderia cepacia complex, Burkholderia pseudomallei, emergent bacterial infections

Burkholderia is a genus comprising several species, including the Burkholderia pseudomallei (Bps) group, the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc), and a cluster of phytopathogen species [1]. The Bps group contains the well-known human pathogen Bps and the animal pathogen B. mallei, causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, respectively [2]. Melioidosis is an infectious disease acquired from water or soil that comes into contact with broken skin or is inhaled or ingested. The infection can be acute, latent, or chronic. Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor, and individuals suffering from this disease are at higher risk for developing melioidosis than the rest of the population [3]. Bps is primarily found in tropical areas, mainly in northern Australia and the south of Asia, but it is being found more frequently in other tropical countries as well [4]. In Mexico, there have been 15 documented cases of melioidosis, between 1958 and 2018 [4], with the most recent resulting in the fatality of 2 teenaged siblings (aged 12 and 16) [5]. These last 2 cases occurred in the northwest part of Mexico, in Sonora, a state where the climate is not tropical or subtropical, but is dry to semidry, with temperatures averaging 22°C and ranging from 5°C to 38°C. This suggests that Bps can adapt to a variety of climates [6]. In Mexico, species from the Bcc have been found in human infections and in the environment, such as in the rhizosphere of sugarcane and maize [1]. This raises the possibility that one could acquire an infection from the environment. Currently, the occurrence of Bps in the environment in several other states in Mexico is being investigated by our research group. Additionally, the Bcc encompasses an assembly of opportunistic pathogens that have been associated with infections in cystic fibrosis patients [7]. Bcc has several clinical manifestations that span from no symptoms to respiratory infections and septicemia. Currently, this group includes 24 species, many of which cause human infections. Among them, B. cenocepacia is considered the most frequent and problematic species, but B. multivorans and B. dolosa are also becoming common causes of infections [8].

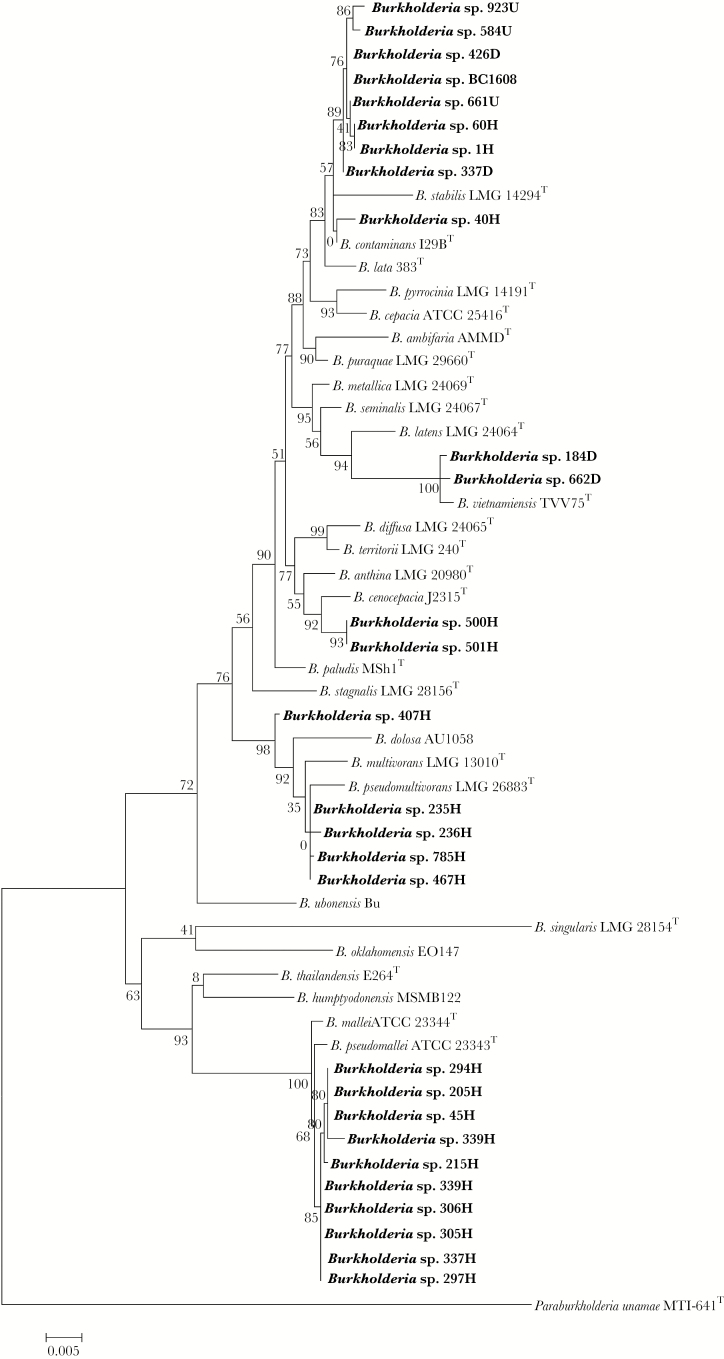

In the present study, a group of 38 strains previously identified as B. cepacia by the VITEK2 system were genotypically and phenotypically characterized. All strains were isolated from pediatric patients in the Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gomez (Mexico Children’s Hospital) in Mexico City. The samples were taken from pharyngeal exudates from children who arrived at the hospital with pneumonia in the period from 2012 to 2016. The 16S rRNA fragment and the atpD gene from each strain were amplified, sequenced, and analyzed according to Estrada de los Santos et al. [9]. The accession numbers of 16S rRNA and atpD are included in Supplementary Table 1. The 16S rRNA fragment was analyzed using the EzBiocloud database (www.ezbiocloud.net), and the results showed that 10 strains belonged to the Bps group, 20 were identified as part of the Bcc, 1 was classified as Acinetobacter lwoffii, 3 were Pseudomonas songenensis, 2 were Enterococcus faecalis, and 1 belonged to the genus Stenotrophomonas (Supplementary Table 2). These results confirmed that in addition to the VITEK2 system, additional tests are needed to correctly identify Burkholderia species. Other studies have validated the finding that it is not unusual to misidentify B. pseudomallei, even in endemic countries [10]. Because it is well known that the identification at the species level for the Bcc cannot be based only on the analysis of 16S rRNA due to its poor resolution in taxonomical analysis, it is necessary to complement identification with a phylogenetic study of other housekeeping genes [9]. We therefore concatenated the sequence of the atpD gene with the 16S rRNA gene using the program Mesquite 3.51 (http://www.mesquiteproject.org) and performed a phylogenetic analysis with the program PhyML, v. 3.0 [11], using the maximum likelihood method. These analyses showed that the strains identified as part of the Bcc are now recognized as different species, which included 2 strains classified as B. cenocepacia, 2 strains as B. vietnamiensis, 4 strains that were phylogenetically related to B. pseudomultivorans, and 1 strain related to B. contaminans (Figure 1). The misidentification of species from the Bcc is known in other countries; however, in Mexico, this cluster of species is poorly recognized and rarely studied. Moreover, several strains were not included in any of the Bcc species described so far (Figure 1). These strains may represent members of novel species, and polyphasic taxonomy analyses are being performed to confirm this observation.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood tree inferred from the concatenated alignment of atpD-16S rRNA genes of Burkholderia species. The bar represents the number of expected substitutions per site under the general time reversible + gamma distributed rate variation among sites.

The analysis also showed that 10 strains were closely related to Bps and B. mallei (Figure 1). To corroborate our findings, suspected strains were streaked in Ashdown medium. This has been proven to be a gold standard method for the identification of Bps isolates [12]. We observed typical Bps growth as wrinkled colonies in the Ashdown medium (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, B. mallei is unable to grow in this medium [13]. What is noteworthy is that this finding confirms the presence of Bps, a causative agent of melioidosis, in Mexican patients. Although the clinical implications have not been established, nor is there a protocol to identify the disease in the clinical setting, further studies will have significant implications for public health. Therefore, we are currently analyzing more strains from other hospitals in Mexico and evaluating soil and water from tropical and subtropical regions. Our preliminary results indicate that Bps has been misidentified in other hospitals, and it has been isolated from soil samples from the Sonora, Chiapas, and Tabasco states in Mexico (unpublished data).

In summary, here we confirm the presence of Bps in clinical isolates, which were not previously identified adequately and were classified as B. cepacia. These findings corroborate the presence of this and other species of the Bps and Bcc groups as potential causative agents for disease in Mexico. We also demonstrate that careful and more extensive microbiological analysis should be done in the clinical laboratory with more effective tools to accurately identify these species.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sherry Haller for editorial assistance.

Financial support. This work was partially supported by Instituto Politecnico Nacional projects SIP 2017-0492, SIP 2018-0647, and SIP 2018-0117. P.E.S. and J.A.I. are grateful for fellowships from Comisión de Operación y Fomento de Actividades Académicas (COFAA), Estímulo al Desempeño de los Investigadores (EDI), and Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Rojas-Rojas FU, Lopez-Sanchez D, Meza-Radilla G, et al. El controvertido complejo Burkholderia cepacia, un grupo de especies promotoras del crecimiento vegetal y patógenas de plantas, animales y humanos. Rev Argent Microbiol. doi:10.1016/j.ram.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wiersinga WJ, Virk HS, Torres AG, et al. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4:17107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Currie BJ. Melioidosis: evolving concepts in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36:111–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanchez-Villamil JI, Torres AG. Melioidosis in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Trop Med Infect Dis 2018; 3:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paredes O. El Imparcial.com 2018. https://elimparcial.com/EdicionEnLinea/Notas/Sonora/09092018/1371570-Detectan-bacteria-rara-en-2-hermanos-fallecidos.html Accessed 9 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yip TW, Hewagama S, Mayo M, et al. Endemic melioidosis in residents of desert region after atypically intense rainfall in central Australia, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 21:1038–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipuma JJ. The changing microbial epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010; 23:299–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sfeir MM. Burkholderia cepacia complex infections: more complex than the bacterium name suggest. J Infect 2018; 77:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Estrada-de los Santos P, Vinuesa P, Martinez-Aguilar L, Hirsch AM, Caballero-Mellado J. Phylogenetic analysis of Burkholderia species by multilocus sequence analysis. Curr Microbiol 2013; 67:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Greer RC, Wangrangsimakul T, Amornchai P, et al. Misidentification of Burkholderia pseudomallei as Acinetobacter species in northern Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2019; 113:48–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guindon S, Delsuc F, Dufayard JF, Gascuel O. Estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies with PhyML. Methods Mol Biol 2009; 537:113–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ashdown LR. An improved screening technique for isolation of Pseudomonas pseudomallei from clinical specimens. Pathology 1979; 11:293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glass MB, Beesley CA, Wilkins PP, Hoffmaster AR. Comparison of four selective media for the isolation of Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 80:1023–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.