Abstract

Recent genomic sequencing analyses have unveiled the spectrum of genomic alterations that occur in primary and advanced prostate cancer, raising the question of whether the corresponding genes are functionally relevant for prostate tumorigenesis, and whether such functions are associated with particular disease stages. In this review, we describe genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) of prostate cancer, focusing on those that model genomic alterations known to occur in human prostate cancer. We consider whether the phenotypes of GEMMs based on gain or loss of function of the relevant genes provide reliable counterparts to study the predicted consequences of the corresponding genomic alterations as occur in human prostate cancer, and we discuss exceptions in which the GEMMs do not fully emulate the expected phenotypes. Last, we highlight future directions for the generation of new GEMMs of prostate cancer and consider how we can use GEMMs most effectively to decipher the biological and molecular mechanisms of disease progression, as well as to tackle clinically relevant questions.

Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) can provide valuable resources for studying tumorigenesis in the context of the whole organism and in the native milieu in which tumors arise, which might otherwise be difficult to accomplish using other types of experimental models. In this regard, analyses of GEMMs can provide valuable insights regarding mechanisms of cancer initiation and progression, the functions of potential driver genes, and preclinical investigations, all of which benefit from being implemented in well-controlled experimental conditions and in the context of immunocompetent whole organisms. From a practical standpoint, advantages of GEMMs include their ease of genetic manipulation and relatively modest cost, compared with larger organisms, and relatively short life span and time course of tumor progression. However, the usefulness of any given GEMM depends on how accurately it informs on the biology, mechanisms, and treatment response of the human cancer it is intended to emulate, which is an essential consideration when attempting to extrapolate experimental findings from mice to humans.

Prostate cancer is particularly well-represented by numerous GEMMs that embody the various stages of disease progression and are based on genomic alterations known to be relevant for human prostate cancer. Like other adenocarcinomas, prostate cancer progresses from preinvasive lesions, called prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), to invasive adenocarcinoma, and, in more advanced cases, to metastasis (Fig. 1) (Abate-Shen and Shen 2000; Shen and Abate-Shen 2010). The majority of clinically localized tumors are relatively indolent and either curable with local therapy or managed by active surveillance because their risk of progression is so low. In contrast, advanced tumors are treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which initially leads to tumor regression, but eventually relapse as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), reflecting the essential role of androgen receptor (AR) signaling activity for all stages of prostate cancer. Indeed, CRPC is more aggressive than primary disease and often associated with lethal metastases, yet it continues to rely on AR signaling even in the absence of androgens (Watson et al. 2015).

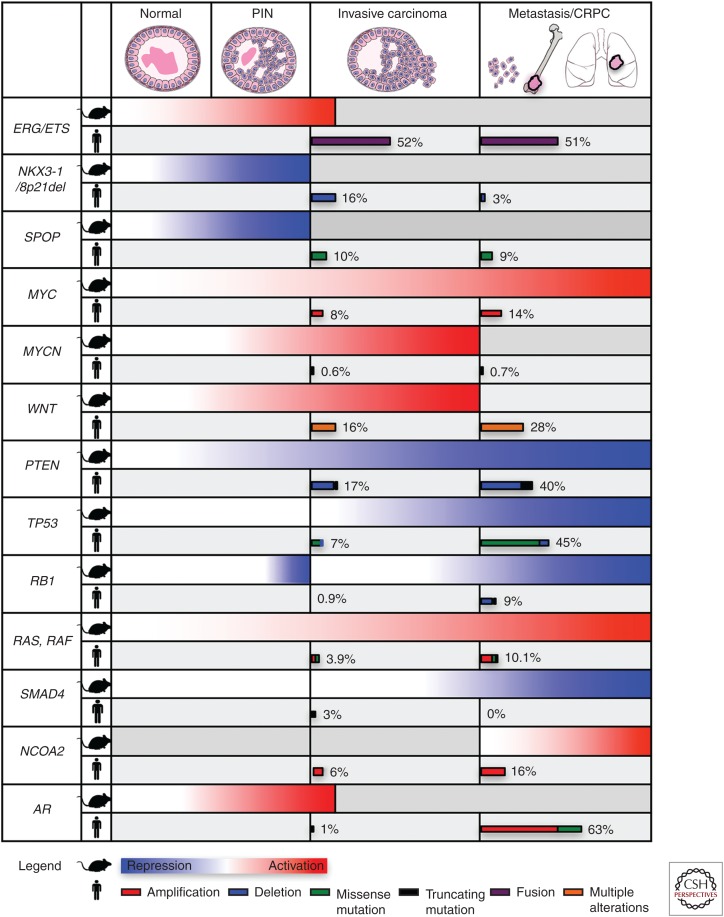

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the relationship of genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) phenotypes to stages of prostate cancer progression and the observed frequencies of genomic alterations on which they are based relative to stages of human prostate cancer. For mouse phenotypes (rows labeled with the mouse symbol), gradients of red are used to denote overexpression or functional activation, and blue is used to denote gene deletion or functional repression. Gray coloring is used to denote where GEMMS do not display phenotypes. Human genomic alterations (rows labeled with the man symbol) show the frequency of occurrence at the specific stages of cancer progression using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data set for primary prostate cancer (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015), and the SU2C data set (Robinson et al. 2015) for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and metastatic disease. Wnt pathway genes include APC, CTNNB1, RSPO2, RNF43, ZNFR3. Ras, Raf genes include KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, BRAF, RAF1. PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; AR, androgen receptor; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

Despite key differences in the anatomy and physiology of the mouse and human prostates (Box 1), GEMMs have proven to be remarkably predictive of human prostate cancer, and genomic alterations that occur at certain disease stages tend to model these stages in mice (Fig. 1). Furthermore, because the description of the TRAMP model (for transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate [Gingrich et al. 1996]), which was the first autochthonous mouse model of prostate cancer (autochthonous means “found in the part of the body in which it originates”), GEMMs have evolved from relatively simple, single-allelic transgenes that express viral oncogenes to highly complex multiallelic models that have become increasingly more sophisticated as the genetic tools for their generation have evolved (Box 2). These “next-generation” GEMMs are proving to be increasingly more robust in capturing essential features of prostate tumorigenesis, as exemplified by the use of lineage tracing to identify cell(s) of origin of cancer, study lineage plasticity, and visualize the genesis of tumors, metastasis, and disseminated cells in vivo (e.g., Aytes et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013b; Zou et al. 2017).

BOX 1.

COMPARISON OF MOUSE AND HUMAN PROSTATE

Located at the base of the bladder surrounding the urethra, the prostate develops late in gestation from the endodermally derived urogenital sinus (Cunha et al. 1987; Toivanen and Shen 2017). In humans, the prostate is a single gland composed of distinct histological zones—namely, the peripheral (PZ), transitional (TZ), and central (CZ) zones, whereas in rodents, the prostate is divided into four lobes—namely, the dorsal (DP), lateral (LP), anterior (AP), and ventral (VP) lobes, with the DP and LP usually considered together as the dorsolateral lobe (DLP) (McNeal 1981). The prostate epitheliums in humans and mice are composed of three cell types: luminal (which are the primary secretory cells), basal (which underlie the luminal cells), and neuroendocrine (which are rare in normal prostate but more prevalent in advanced disease). However, in humans, basal cells form a continuous layer, whereas in mice they are discontinuous. A stromal compartment surrounds the epithelium in both species, albeit with significant species differences (Roy-Burman et al. 2004; Cunha 2008). In humans, the fibromuscular stroma forms a capsule-like structure that surrounds the prostate and provides a boundary that can be used to assess local invasiveness. Although normally not present in mice, progression to invasive adenocarcinoma in GEMMs is often accompanied by remodeling and expansion of the stroma (desmoplasia), including the generation of new blood vessels and immune infiltration (Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013).

Considering that the large majority (>85%) of human prostate cancers arise in the peripheral zone, the relationship between the zones of human prostate and the lobes of the mouse prostate is an important issue. Notably, GEMMs of prostate cancer often display lobe-specific phenotypes because of various factors, such as the genetic alteration, mode of gene targeting, or mouse strain background. Based on anatomical considerations, it has been suggested that the location of mouse prostatic ducts relative to the urethra may indicate their similarity to human prostate cancer zones (Price 1963). Furthermore, based on histological analyses, the AP has been equated with the central zone and the DLP with the peripheral zone, whereas the mouse VP does not have an obvious human equivalent, nor does the human transitional zone have an obvious mouse equivalent. Expression profiling analyses of the human peripheral zone has shown that it is more similar to mouse DLP than to the AP or VP (Berquin et al. 2005); however, analogous profilings of the TZ or CZ were not analyzed. Therefore, the consensus report of the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee has suggested that it may be premature to assume any mouse lobe to be more relevant for human prostate cancer (Ittmann et al. 2013).

A key difference between mouse and human prostates is that the former rarely develops spontaneous benign or malignant lesions during its life span. In contrast, age is one of the major risk factors of prostate cancer in humans, with 60% of diagnoses occurring in men 65 years of age or older. Additionally, whereas human prostate cancer harbors between 10 and 100 nonsynonymous mutations and multiple chromosomal rearrangements and somatic copy number aberrations (Taylor et al. 2010; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015), most mouse prostate tumors rarely show karyotypic abnormalities and present very few somatic copy number alterations, with notable exceptions (Hubbard et al. 2016). Although these differences may be explained by the shorter life span (∼3 yr) of mice (which allows less time for genetic alterations to accumulate), telomeres in mice are five to 10 times longer than in humans, and therefore mice are less prone to telomere-induced aging and ensuing genetic alterations. Indeed, GEMMs that have more extensive genome instability, such as those based on telomerase dysfunction or having high-level expression of Myc (Ding et al. 2012; Bojovic and Crowe 2013; Wanjala et al. 2015; Hubbard et al. 2016), tend to acquire more complex rearrangements and alterations. A subset of these alterations is syntenic to those found in human cancers and may even lead to acquisition of new biological capabilities (i.e., bone metastasis) that more closely resemble human cancer (Ding et al. 2012; Hubbard et al. 2016).

Despite these species differences, cross-species transcriptomic analyses have shown that GEMMs of prostate cancer share molecular features in common with human prostate cancer. In particular, our group and others have used expression profiles to assemble genome-wide regulatory networks (termed interactomes) for human and mouse prostate cancer to enable cross-species interrogation of molecular pathways (Aytes et al. 2014; You et al. 2016). These studies have shown that the molecular pathways driving prostate cancer in mice and humans are highly conserved and informative for understanding molecular mechanisms associated with progression, predicting biomarkers of progressive disease, and predicting cancer prevention and intervention strategies (Floc’h et al. 2012; Aytes et al. 2013, 2014; Irshad et al. 2013; Zou et al. 2017).

BOX 2.

TARGETING GENE EXPRESSION IN THE PROSTATE

The generation of a plethora of GEMMs of prostate cancer has been fueled by the availability of several promoters that direct gene expression specifically to prostate, albeit with varying lobe or cell type, and androgen responsivity. Many of these promoters have been used to generate constitutive and inducible Cre alleles for conditional gene targeting. In particular, these express Cre recombinase, which catalyzes recombination between “floxed” loxP sites, resulting in deletion of intervening genomic DNA and consequential gene inactivation, when the loxP sites flank essential exons, or gene activation, when the loxP sites flank transcriptional termination sequences.

The most commonly used promoter is from the rat probasin (PB) gene, which is a secretory protein expressed in rodent prostate. These include the minimal PB promoter (426 base pair minimal region [Greenberg et al. 1994]), the large PB promoter (11,528 base pair [Yan et al. 1997]), and the composite PB (ARR2PB) promoter (the minimal region with the addition of AR binding sites [Zhang et al. 2000]). Notably, the minimal PB and large PB promoters were used to develop transgenic mice expressing viral oncogenes in prostate to generate the first GEMMs of prostate cancer, called the TRAMP and the LADY models, respectively (Gingrich et al. 1997; Kasper et al. 1998). The ARR2PB promoter, which has higher-level expression, has been used to generate the widely used Cre driver, the PB-Cre4 allele (Wu et al. 2001). These probasin promoter sequences are androgen-responsive and direct-expression, primarily in the VP and secondarily in the DLP, and are active before prostate maturation and continuing throughout adulthood; however, focal expression in the stroma of prostate and seminal vesicle, as well as expression in testes, can complicate analysis.

Prostate-specific gene recombination has also been achieved by expressing Cre under the control of the endogenous promoter of the Nkx3.1 homeobox gene to generate an Nkx3.1-Cre allele (Lin et al. 2007). Nkx3.1 is an androgen-regulated gene, which is primarily restricted to the prostatic luminal cells in adults but is expressed in other tissues during development (Bhatia-Gaur et al. 1999). Therefore, to overcome nonprostatic expression during development, an inducible Cre allele, Nkx3.1-CreERT2, has been used to achieve gene recombination in adults following tamoxifen induction; Cre activity occurs primarily in the AP and DLP with limited expression in the VP (Wang et al. 2009).

Prostate-specific inducible CreERT2 alleles have also been developed using the promoters of the Tmprss2 gene (Gao et al. 2016) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) promoter (Cleutjens et al. 1997a,b). The use of the androgen-regulated Tmprss2 promoter, which has been used to express Ets genes in the prostate, has the additional advantage of modeling the highly prevalent TMPRSS2-ERG or ETV1 fusions occurring in human cancer (Tomlins et al. 2005). For all CreERT2 alleles, a caveat is the use of tamoxifen, which may affect prostate phenotypes that are highly responsive to hormones.

An alternative inducible system that has not been as widely used in prostate is based on tetracycline regulation, in which gene expression is regulated by a tetracycline-dependent transcription factor that can either be transiently repressed (the tTA variant) or activated (the rtTA variant) when doxycycline is administered. This has been used to drive expression from the promoter of HoxB13, which is a homeobox gene that is largely restricted to the prostate in adults (McMullin et al. 2009) and has been associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in humans (Ewing et al. 2012). Another important difference with the promoters mentioned above is that HoxB13 is androgen-independent (McMullin et al. 2009). Although widely expressed in prostatic luminal as well as some basal cells, the HoxB13 promoter has the drawback of also being expressed in colonic and rectal epitheliums (Hubbard et al. 2016).

In this review, we describe current GEMMs of prostate cancer, focusing on those that model genomic alterations that occur in human prostate cancer, and considering their relationship to the intrinsic biology and progression of prostate cancer, as well as their potential to tackle pressing clinical needs. For additional discussion of prostate cancer GEMMs, we refer the reader to other recent reviews (Roy-Burman et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2011; Irshad and Abate-Shen 2013; Ittmann et al. 2013; Parisotto and Metzger 2013; Grabowska et al. 2014).

MODELING IN MICE THE GENOMIC ALTERATIONS THAT OCCUR IN HUMAN PROSTATE CANCER

The recent elucidation of genomic alterations that occur in human prostate cancer has fueled the generation of GEMMs designed to investigate the functional relevance of the corresponding genes for prostate tumorigenesis (Fig. 1). In particular, whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing combined with expression profiling have elucidated molecular alterations in primary tumors, CRPC, and metastases (Taylor et al. 2010; Barbieri et al. 2012; Grasso et al. 2012; Baca et al. 2013; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015; Beltran et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2016; Fraser et al. 2017). The presumption is that GEMMs based on molecular alterations that occur early in cancer progression should model premalignant or early-stage disease, whereas those based on molecular alterations prevalent at later stages should model advanced disease. This has been largely borne out in the phenotypes of the resulting GEMMs, with some notable exceptions (see below).

In particular, alterations that are prevalent in primary tumors include fusions of ETS genes, such as TMPRSS2-ERG, mutations in the E3 ubiquitin ligase SPOP, and allelic loss of chromosomal region 8p1, including the NKX3.1 homeobox gene (Barbieri et al. 2012; Grasso et al. 2012; Baca et al. 2013; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Fraser et al. 2017). The corresponding GEMMs primarily display PIN and/or early cancer phenotypes (Fig. 1). On the other hand, genomic alterations that are more prevalent in advanced prostate cancer, such as CRPC, small cell/neuroendocrine, and/or metastatic disease, include loss of function or mutation of tumor suppressors, such as PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), TP53, and retinoblastoma (RB), defects in DNA repair genes, such as ATM and BRCA2, and amplification of oncogenes, such as c-MYC and N-MYC (Taylor et al. 2010; Grasso et al. 2012; Baca et al. 2013; Robinson et al. 2015; Beltran et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2016). The corresponding GEMMs typically display more advanced prostate cancer phenotypes, often associated with CRPC, and sometimes metastasis (Fig. 1). Notably, the functional consequences for prostate tumorigenesis of dysregulation of several of these genes, such asTrp53, are not unmasked until combined with other genomic alterations (see below), consistent with their association with advanced disease.

MODELING AR SIGNALING IN MICE

Essential for prostate development and differentiation, the AR is arguably the most important driver of human prostate cancer as it plays a pivotal role at all stages of disease progression, even in contexts of androgen deprivation (Watson et al. 2015). Notably, amplification and/or mutation of AR is highly prevalent in metastatic tumors that arise following ADT (>60%; Robinson et al. 2015). Accordingly, loss of function of AR in mouse epithelium and/or stroma leads to defects in prostate differentiation and/or small prostate glands (Wu et al. 2007; Niu et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2017), whereas depletion of AR in prostate epithelium and/or stroma abrogates cancer progression in the context of Pten heterozygosity and in the TRAMP model (Niu et al. 2008; Lai et al. 2012).

However, GEMMs based on AR gain of function, in general, do not display the robust phenotypes expected based on the prevalence of AR alterations in advanced prostate cancer in humans. In particular, GEMMs based on overexpression of AR in the epithelium either have no apparent phenotype or display PIN phenotypes with incomplete penetrance and long latency (Stanbrough et al. 2001; Han et al. 2005), whereas GEMMs based on conditional overexpression of human AR using a Cre driver that is not restricted to prostate (Osr1-Cre for odd-skipped-related-Cre) develop PIN and low incidence of adenocarcinoma (Zhu et al. 2011). AR spliced variants have been shown to have clinical relevance (Watson et al. 2015), yet GEMMs expressing a human AR splice variant, AR-V7, associated with treatment response in human prostate cancer results in PIN that does not progress to adenocarcinoma (Sun et al. 2014), whereas GEMMs expressing another splice variant, AR-v567es, develop invasive phenotypes (Liu et al. 2013). Other GEMMs that express mutated forms of AR, including a mutation in the amino-terminal region, develop adenocarcinoma with distant metastases (Han et al. 2005), whereas one based on a mutation in the ligand-binding domain displays accelerates tumor progression in the TRAMP model (Takahashi et al. 2011).

Although inherent differences in AR signaling between mouse and human prostate may be a factor, it seems likely that the relatively modest phenotypes of current AR-based GEMMs may reflect suboptimal design. As discussed below, most GEMMs of advanced prostate cancer have two or more genetic alterations, whereas most AR-based GEMMs have been studied as single alleles. Thus, it is possible that GEMMs combining gain of function of AR with other genomic alterations, particularly those that occur in advanced disease, will result in more aggressive phenotypes that more closely mimic what is expected based on the known functions of AR in human prostate cancer. Indeed, in human prostate cancer, AR mutations rarely occur in early stage disease or the androgen-intact prostate; thus, whereas defects in AR signaling contribute to disease progression, they may not be sufficient for cancer initiation. In this regard, it is not surprising that GEMMs based on single alterations of AR in hormonally intact contexts do not effectively model the functions of AR in human prostate cancer. Clearly, the generation of more relevant GEMMs of AR gain of function is a key area in need of further development.

MODELING PREMALIGNANT AND EARLY-STAGE HUMAN PROSTATE CANCER

An important consideration in modeling cancer in mice is establishing whether the histopathology of the resulting tumor resembles that of their human counterpart. This is particularly important for prostate cancer considering the significant anatomical and histological differences in the prostates of mice and humans (Box 1). In this regard, comparative histopathology of mouse versus human prostate cancer has played a vital role in the validation of GEMMs and assessment of their relevance for particular disease stages (Park et al. 2002; Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013). Such comparative histopathology supports the idea that the mouse prostate can develop PIN phenotypes with the potential to progress to adenocarcinoma, given appropriate molecular contexts. Mouse PIN (mPIN) has been characterized on a scale from 1 to 4 based on increasing degrees of architectural and cytological abnormalities, although it is more frequently divided into low-grade PIN (mPIN1 and -2) and high-grade PIN (mPIN3 and -4) (Park et al. 2002; Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013). Notably, several GEMMs based on genes altered in primary tumors, including Erg, Nkx3.1, and SPOP, develop PIN (Fig. 1), and analyses of their phenotypes have informed on the functions of these genes for prostate cancer initiation, as well as their interactions with other relevant genomic alterations for cancer progression.

ETS Gene Fusions

ERG and other ETS family genes, such as ETV1, are overexpressed in a high percentage of primary prostate tumors (∼50%; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015), primarily as a consequence of their fusion to the promoter of TMPRSS2 (Tomlins et al. 2005). Accordingly, most transgenic models based on overexpression of Erg or Etv1 have been reported either to develop PIN (Tomlins et al. 2007, 2008; Klezovitch et al. 2008) or have relatively normal prostate histopathology (Carver et al. 2009; King et al. 2009; Baena et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2013), with the notable exception of a transgene expressing high levels of ERG that has been reported to develop invasive adenocarcinoma after long latency (Nguyen et al. 2015). Although most GEMMs based on overexpression of Erg or Etv1 do not develop overt adenocarcinoma, they collaborate with loss of function of Pten in cancer progression, in part, by affecting AR signaling (Carver et al. 2009; King et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2013).

8p21 and NKX3.1

Another common early event in primary prostate cancer is loss of chromosomal region 8p21 (∼60%; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015), leading to reduced expression of NKX3.1, a key regulator of prostate development, differentiation, and stem cell function (Shen and Abate-Shen 2010). Germline or conditional loss of function of Nkx3.1 in mice results in PIN, particularly in aged mice (Bhatia-Gaur et al. 1999; Abdulkadir et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2002a). Notably, Nkx3.1 heterozygotes display a similar, although less severe, phenotype as their null counterparts, consistent with the expected haploinsufficiency of NKX3.1 in human prostate cancer. Whereas Nkx3.1 mutant mice do not progress beyond PIN, they cooperate with loss of function of Pten in cancer progression (Kim et al. 2002b). Interestingly, loss of function of Nkx3.1 was found not to cooperate with Tmprss2-Erg (Linn et al. 2015), despite evidence that NKX3.1 loss facilitates the occurrence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusions in human prostate cancer (Bowen et al. 2015).

SPOP and Other Early Alterations

Among other genomic alterations that occur in early-stage disease, point mutations in the E3 ligase SPOP, most commonly F133V, occur in ∼10% of primary prostate tumors and are mutually exclusive with translocation of ETS genes (Barbieri et al. 2012; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015). Similar to other early drivers of prostate cancer, a GEMM based on expression of SPOPF133V has a modest phenotype on its own, but it develops high-grade PIN and invasive cancer in combination with loss-of-function of Pten (Blattner et al. 2017). Notably, SPOP mutations often co-occur with homozygous deletion of chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 1 (CHD1) (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015). Prostate-specific loss of function of Chd1 results in PIN that does not progress to adenocarcinoma and displays DNA damage repair (DDR) defects similar to those reported for SPOP mutation (Shenoy et al. 2017), suggesting that these genes may cooperate in cancer progression by affecting the DNA damage response. Another gene altered in early stage prostate cancer is FOXA1, a transcription factor that is required for normal prostate organogenesis and mutated in ∼4% of primary prostate tumors, being mutually exclusive with ETS- and SPOP-related alterations (Barbieri et al. 2012; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015). Conditional prostate-specific deletion of FoxA1 results in hyperplasia, which does not progress to more advanced phenotypes (DeGraff et al. 2014). It is plausible that FoxA1, like other early genomic alterations, requires interaction with additional mutational events for disease progression at least in mice.

MODELING ADENOCARCINOMA, CASTRATION RESISTANCE, AND NEUROENDOCRINE DIFFERENTIATION

Numerous GEMMs have been generated based on genomic alterations that occur in later stages of prostate cancer in humans. Many capture key features of the advanced disease, however, some have important differences. In particular, prostate adenocarcinoma in GEMMs is dependent on AR signaling, as is the case in human prostate cancer, whereas depletion of androgens results in the emergence of CRPC (Shen and Abate-Shen 2007). However, most of the promoters used to generate GEMMs of prostate cancer are themselves dependent on AR signaling, which complicates analyses of hormone dependence of their phenotypes (Box 2). Additionally, androgen depletion in GEMMs is usually achieved by surgical castration, whereas relatively few studies have used hormonal treatment for ADT (Lunardi et al. 2013), which is more commonly used in clinical settings. Among other notable differences, most GEMMs that have invasive phenotypes retain or even have expansion of basal epithelial cells (Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013), whereas a hallmark of human prostate cancer is the loss of basal cells (Box 2). Furthermore, many advanced tumors in GEMMs have sarcomatoid differentiation, which is much less common in human prostate cancer (Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013). Neuroendocrine differentiation is also a feature of some advanced GEMMs, which was once considered to undermine their relevance for human prostate cancer (Shappell et al. 2004). However, as neuroendocrine or small-cell phenotypes have become increasingly more prevalent in humans as a consequence of treatment failure (see below and Rickman et al. 2017), GEMMs representing these phenotypes are considered increasingly more relevant (Berman-Booty and Knudsen 2015).

Activation of MYC

The most commonly amplified region in human prostate cancer is in chromosome 8q, which often leads to deregulated expression of MYC (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015) (Fig. 1). Accordingly, several GEMMs have been generated that overexpress Myc in the prostate, resulting in phenotypes ranging from PIN to overt adenocarcinoma, depending on their level of Myc expression (Ellwood-Yen et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2012; Hubbard et al. 2016). For example, the “low-Myc” transgenic mice, based on expression of Myc from the minimal probasin promoter (Box 2), develop PIN after long latency, whereas the “high-Myc” mice, based on the composite ARR2PB probasin promoter (Box 2), develop adenocarcinoma by 6 months of age (Ellwood-Yen et al. 2003). The high-Myc mice also develop CRPC following androgen deprivation; however, an important caveat is that because the transgene is based on an androgen-responsive promoter, regression following androgen deprivation may reflect the loss of oncogene expression.

A common feature of Myc-based GEMMs is that they tend not to display sarcomatoid or neuroendocrine differentiation (Hubbard et al. 2016), which are common in other GEMMs (see below), and therefore the Myc-based models are considered to be more representative of human adenocarcinoma. However, a GEMM based on loss of function of Pten combined with overexpression of N-Myc, which is associated with neuroendocrine differentiation in humans (Beltran et al. 2011), displays invasive adenocarcinoma with focal neuroendocrine histopathology (Dardenne et al. 2016).

Although several studies have investigated collaboration of Myc with other relevant genomic alterations in prostate cancer progression by combining Myc-based GEMMs with other alleles (Table 1), these are relatively few compared with analogous ones using Pten-based GEMMs (see below; Table 2). Among these, GEMMs having gain of function of Myc (Z-Myc) and loss of function of Nkx3.1 display higher-grade PIN (Anderson et al. 2012), consistent with the observed loss of expression of Nkx3.1 in adenocarcinoma in Hi-Myc mice (Ellwood-Yen et al. 2003), Notably, Myc-based GEMMs cooperate with those having loss of function of p53 and/or Pten, leading to highly advanced metastatic phenotypes (Kim et al. 2009; Hubbard et al. 2016) (see below).

Table 1.

Mouse phenotypes of genetic alterations combined with Myc

| Myc allele | Gene | Alteration | Consequent progression to | Proposed mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hi-Myc (Myc transgene driven by the ARR2PB promoter) | |||||

| Hepsin | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Basement-membrane degradation | Nandana et al. 2010 | |

| mpAkt | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | PI3K pathway signaling activation | Clegg et al. 2011 | |

| IKBa | Hemizygous loss | Castration independence | NF-κB signaling activation | Jin et al. 2008 | |

| Z-Myc (Myc transgene driven by the CMV/β-actin promoter) | |||||

| Nkx3.1 | Conditional loss of expression | High-grade PIN with microinvasion | Enhanced Myc transcriptional activity | Anderson et al. 2012 | |

| Pten | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Senescence bypass | Kim et al. 2009 | |

| Pten and Trp53 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Kim et al. 2012 | ||

PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; PI3K, phoshoinositide 3-kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B.

Table 2.

Compound GEMMs based on loss of function of Pten

| Gene | Alteration | Consequent progression to | Proposed mechanism | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemizygous loss (germline heterozygous Pten allele) | ||||

| Sox9 | Gain of expression | Increased incidence of high-grade PIN | Increased proliferation | Thomsen et al. 2010 |

| Nkx3.1 | Hemizygous or homozygous loss | High-grade PIN with invasive adenocarcinoma | Increased pAkt | Kim et al. 2002; Abate-Shen et al. 2003 |

| p27/Kip1 | Hemizygous or homozygous loss | High-grade PIN with invasive adenocarcinoma | Increased proliferation, Cyclin D1 upregulation | Di Cristofano et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2004 |

| Bmi | Gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | DNA damage signaling, genomic instability | Nacerddine et al. 2012 |

| Tsc2 | Hemizygous loss | Invasive adenocarcinoma | mTOR pathway activation | Ma et al. 2005 |

| Phlpp1 | Hemizygous or homozygous loss | Invasive adenocarcinoma | p53-mediated senescence bypass | Chen et al. 2011 |

| Chk1 | Hemizygous loss | Invasive adenocarcinoma | DNA damage signaling and genomic instability | Lunardi et al. 2015 |

| Pkcε | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Non-canonical NF-κB activity | Garg et al. 2017 |

| Homozygous loss (conditional Pten allele) | ||||

| Nr2f2 | Conditional loss of expression | Arrested cancer progression | Induction of TGF-beta signaling and senescence | Qin et al. 2013 |

| Nr2f2 | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Inhibition of Smad4/TGF-beta signaling | Qin et al. 2013 |

| Ncoa2 | Conditional loss of expression | Delayed cancer progression | Inhibition of proliferation | Qin et al. 2014 |

| Ncoa2 | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | PI3K/MAPK pathway activation | Qin et al. 2014 |

| Gata3 | Conditional gain of expression | Delayed cancer progression | PI3K pathway inhibition | Nguyen et al. 2013 |

| GATA3 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | PI3K pathway activation | Nguyen et al. 2013 |

| Nsd2 | Conditional loss of expression | Delayed cancer progression | Inhibition of proliferation | Li et al. 2017 |

| NSD2 | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | PI3K pathway activation | Li et al. 2017 |

| Sag | Conditional loss of expression | Delayed cancer progression | Inhibition of proliferation | Tan et al. 2016 |

| Timp3 | Homozygous loss | High-grade PIN with micro-invasion | Increased inflammation and vascularity | Adissu et al. 2015 |

| Erg or Etv1 | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Increased AR signaling | Carver et al. 2009; Baena et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2013 |

| Mkk4/7 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Inhibition of Jun kinase signaling | Hubner et al. 2012 |

| Atf3 | Homozygous loss | High-grade PIN with invasive adenocarcinoma | PI3K pathway activation, increased proliferation | Wang et al. 2015 |

| Junb | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Increased Proliferation, decreased senescence | Thomsen et al. 2015 |

| SPOP F133V | Gain of expression of mutated gene | Invasive adenocarcinoma | PI3K pathway and AR signaling activation | Blattner et al. 2017 |

| PSGR | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Activation of NFκB signaling | Rodriguez et al. 2016 |

| Trp53 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma (with metastasis) | Senescence bypass, Myc activation, neuroendocrine differentiation | Chen et al. 2005; Cho et al. 2014; Zou et al. 2017 |

| Rb | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma, NEPC-like (with metastasis) | Senescence bypass, neuroendocrine differentiation | Ku et al. 2017 |

| Zbtb7a | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Senescence bypass, Sox9 expression | Wang et al. 2013 |

| MYCN | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with NEPC | AR repression, PRC2 induction | Dardenne et al. 2016 |

| Jnk1/2 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Increased proliferation, decreased senescence | Hubner et al. 2012 |

| Stat3 | Conditional loss of expression | Poorly differentiated cancer with metastasis | Senescence bypass | Pencik et al. 2015 |

| Il6 | Homozygous loss | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Diminished Stat3 signaling | Pencik et al. 2015 |

| NICD | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Notch Activation | Kwon et al. 2016 |

| Smad4 | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Cyclin D1 upregulation and senescence bypass | Ding et al. 2011 |

| Telomere dysfunction (Smad4/p53) | Conditional loss of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with extensive metastasis | Telomere reactivation | Ding et al. 2012 |

| HoxB13/Myc | Conditional gain of expression | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Genomic instability | Hubbard et al. 2016 |

| Braf V600E | Gain of expression of mutated gene | Invasive adenocarcinoma with metastasis | Senescence bypass and Myc activation | Wang et al. 2012 |

| Kras G12D | Gain of expression of mutated gene | Invasive adenocarcinoma/sarcomatoid differentiation with extensive metastasis | EMT, ETV4 overexpression | Mulholland et al. 2012; Aytes et al. 2013 |

GEMMs, genetically engineered mouse models; PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; NEPC, neuroendocrine prostate cancer; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; AR, androgen receptor; PRC2, Polycomb repressive complex 2; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition.

Loss of Function of PTEN or Activation of PI3K Signaling

Undoubtedly, the most prevalent prostate cancer GEMMs are based on germline or conditional loss of function of Pten (Table 2). Indeed, in human prostate cancer, deletion of chromosomal region 10q23 with corresponding loss of PTEN occurs in ∼17% of primary tumors and at significantly higher frequencies (∼40%) in CRPC and metastasis (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015), whereas PTEN protein expression is reduced with a much higher frequency. Pten-based GEMMs display dose-dependent phenotypes (Trotman et al. 2003). In particular, whereas germline homozygous Pten loss of function is embryonic lethal, Pten heterozygotes develop prostate adenocarcinoma, although such phenotypes arise with longer latency than other spontaneous tumors that occur in these mice (Di Cristofano et al. 1998; Podsypanina et al. 1999), which limits their utility for studying prostate cancer. Consequently, most Pten GEMMs have used conditional floxed alleles (e.g., Lesche et al. 2002), based on prostate-specific deletion using constitutively active Cre drivers, such as PBCre4, or inducible ones, such as PSA-CreERT2 and Nkx3.1CreERT2 (Box 2).

Although the various GEMMs based on loss of function of Pten differ in the severity of their reported phenotypes, most develop high-grade PIN that progresses to adenocarcinoma (Di Cristofano et al. 1998; Podsypanina et al. 1999; Trotman et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003; Backman et al. 2004; Ma et al. 2005b; Ratnacaram et al. 2008; Floc’h et al. 2012), in some cases with limited metastasis (Abate-Shen et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003). Reported differences in the severity of Pten-based GEMMs have been attributed to various factors, such as the timing of gene recombination relative to prostate differentiation, the specific cell type(s) targeted for recombination, the specificity and/or strength of the Cre-driver, the specific exons of Pten being deleted, mouse strain background, and differences in pathological interpretation of the phenotypes. For example, considering that an important feature of Pten-based GEMMs is their propensity to develop CRPC following androgen deprivation (Shen and Abate-Shen 2007), it is plausible that different androgen-levels in distinct mouse strain backgrounds may contribute to differences in their phenotypes. In fact, loss of function of Pten may be sufficient for acquisition of androgen independence in GEMMs (Gao et al. 2006; Shen and Abate-Shen 2007; Mulholland et al. 2011; Floc’h et al. 2012), which makes them particularly valuable for studying CRPC.

Despite their differences among specific models, in general, Pten-based GEMMs have robust prostate cancer phenotypes and consequently have been widely used for investigating the collaboration Pten loss of function with other genomic alterations (Table 2). Indeed, GEMMs based on numerous genes, many of which have modest phenotypes on their own, have been shown to collaborate with loss of function of Pten in prostate cancer progression (Table 2). For example, germline heterozygous loss of function of Pten has been shown to collaborate with loss of function of the Nkx3.1 homeobox gene and/or the p27kip1 cell cycle inhibitor (Di Cristofano et al. 2001; Gao et al. 2004; Majumder et al. 2008). Furthermore, the key observation that prostate-specific loss of function of Pten is associated with cellular senescence, which limits tumor progression (Chen et al. 2005), has led to the identification of several mechanisms that overcome the senescence phenotype and promote adenocarcinoma, including castration (Floc’h et al. 2012) and loss of function of Trp53 (Chen et al. 2005). In some contexts, Pten-based GEMMs have been shown to collaborate with other genetic alterations to drive metastatic phenotypes, as occurs with gain of function of Myc (Hubbard et al. 2016), activation of Ras signaling (Mulholland et al. 2012; Aytes et al. 2013), or perturbation of TGF-β signaling (Ding et al. 2011).

The significance of deregulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling is further underscored by its striking activation in advanced prostate cancer (∼90%) (Taylor et al. 2010), which exceeds the incidence of PTEN mutation in advanced prostate cancer (∼40%) (Robinson et al. 2015). Accordingly, alterations of other components of PI3K signaling have been evaluated in GEMMs, most of which have relatively modest phenotypes on their own, but collaborate with Pten loss of function in cancer progression (Table 2). These include loss of function of the protein phosphatase Phlpp1 or the Tuberous Sclerosis 2 (Tsc2) tumor suppressor and activation of the PI3K subunit, p110β (Pi3kcb) (Ma et al. 2005a; Lee et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2011). Conversely, deletion of genes that activate PI3K signaling, including p110β (Pi3kcb), mTOR, or Rictor (Jia et al. 2008; Guertin et al. 2009; Nardella et al. 2009), diminish or abrogate the consequences of Pten loss-of-function in GEMMs. Other genetic alterations that delay cancer progression of Pten-based GEMMs models include loss of function of the autophagy-related gene, Atg7, or a key component of microRNA biogenesis, Dgcr8 (Belair et al. 2015; Santanam et al. 2016), suggesting that these processes may contribute to PI3K pathway signaling in prostate cancer.

Deletion or Mutation of TP53

Although TP53 is one of the most frequently altered genes in human cancer, it is rarely mutated in primary prostate cancer (<2%) but is deleted or mutated in >50% of CRPC and metastases (Robinson et al. 2015). Accordingly, GEMMs based on germline or conditional loss of function of Trp53 have modest prostate cancer phenotypes on their own; however, they accelerate tumor progression when combined with loss-of-function of other tumor suppressors, such as Pten, Rb, and Brca2 (Chen et al. 2005; Zhou et al. 2006, 2017; Couto et al. 2009; Francis et al. 2010; Cho et al. 2014; Ku et al. 2017). Similarly, prostate-specific expression of a common p53 mutant, Trp53R270H (equivalent to the human hotspot mutant R273H) had a modest PIN phenotype that is accelerated when combined with heterozygous loss of function of Nkx3.1 (Vinall et al. 2012). In some contexts, GEMMs based on combined loss of function of Trp53 and Pten may display metastatic phenotypes, such as when tumor induction is achieved using a lentiviral Cre delivery method called the “rapid-cap” system (Cho et al. 2014). Furthermore, following ADT, combined loss of function of Trp53 and Pten with Nkx3.1 haploinsufficiency results in CRPC with focal or overt small-cell-like/neuroendocrine differentiation and rare metastasis; notably, these highly aggressive tumors are not only resistant to antiandrogen treatment, they have accelerated disease progression following such treatment (Zou et al. 2017). Additionally, in the context of telomerase deficiency, Trp53- and Pten-based GEMMs display genomic instability with development of metastases (Ding et al. 2012).

WNT Pathway

Despite the fact that WNT signaling is predicted to be activated in ∼15% of primary and ∼28% of CRPC and metastasis via mutation of APC or β-catenin (Grasso et al. 2012; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015), GEMMs based on altered Wnt signaling have been relatively understudied. In particular, GEMMs based on conditional loss of function of Apc in prostate develop high-grade PIN or adenocarcinoma, depending on the Cre driver, and collaborate with gain of expression of Hepsin in cancer progression (Bruxvoort et al. 2007; Valkenburg et al. 2014, 2015). Correspondingly, GEMMs based on conditional activation of β-catenin display PIN phenotypes, which have accelerated cancer progression in collaboration with loss of function of Pten, gain of expression of Myc, or activation of Kras, or in the context of the LADY transgenic model, which expresses the SV40 T-antigen under the control of the large Probasin promoter (Box 2) (Kasper et al. 1998; Pearson et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2009, 2011; Francis et al. 2013; Nopparat et al. 2015).

Epigenetic Regulators

Alterations affecting genes that regulate the epigenome, such as histone methylases and demethylases, have been shown to be mutated in advanced prostate cancer (Robinson et al. 2015), but have only recently been studied in GEMMs. In particular, prostate-specific overexpression of EZH2, a subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex 2, stimulates tumorigenesis (Koppens et al. 2017); however, a previous study had shown that prostate cancer in mice is largely independent of Ezh2 (Wassef et al. 2015). Additionally, both loss and gain of function GEMMs of NSD2, a histone methyltransferase that is downstream of Ezh2, have affirmed its importance for tumorigenesis in the context of Pten loss of function (Li et al. 2017).

MODELING METASTATIC PROSTATE CANCER

The most prevalent site of human prostate cancer metastasis is bone (Logothetis and Lin 2005), although metastasis to soft tissues is becoming increasingly more common following antiandrogen treatment failure (Berman-Booty and Knudsen 2015; Rickman et al. 2017). However, modeling de novo bone metastasis is among the major challenges of studying prostate cancer in GEMMs. Indeed, lung is the most common site of distant metastasis in GEMMs, whereas relatively few GEMMs have been reported to develop bone metastases, and if so these occur with low penetrance (e.g., Magnon et al. 2013; Hubbard et al. 2016; Ku et al. 2017). Additionally, not all studies distinguish true metastases from spontaneous tumors, which are common in inbred mice particularly in lung (Jackson Laboratory 1975), or from invasion of adjacent organs, or intravascular emboli, which are pathologically and biologically distinct from metastasis (Shappell et al. 2004; Ittmann et al. 2013).

RB

Similar to TP53, allelic loss of the RB tumor suppressor gene is rare in primary tumors but more prevalent in advanced disease, albeit with lower frequency than TP53 (∼10%; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015). Similar to Trp53-based GEMMs, conditional loss of function of Rb in prostate has a relatively modest phenotype on its own (Maddison et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2006), but it collaborates with other genomic alterations to accelerate cancer progression. In particular, GEMMs based on combined loss of function of Rb with Trp53 and/or Pten develop invasive adenocarcinoma, as well as CRPC following androgen deprivation, with accompanying metastases to lungs, liver, and rarely to bone (Zhou et al. 2006; Ku et al. 2017). Notably, CRPC in these GEMMs have reduced AR expression and display features of neuroendocrine differentiation (Zhou et al. 2006; Ku et al. 2017), which are analogous to tumor phenotypes arising in transgenic models based on viral oncogenes that cotarget Rb and p53 pathways such as the TRAMP and LADY models (Gingrich et al. 1996, 1997; Kasper et al. 1998).

Myc-Pten-p53 Cooperativity

GEMMs based on gain of expression of Myc together with loss of function of Trp53 and/or Pten tend to develop metastasis, the degree of which is related to the levels of Myc expression. In particular, GEMMs having relatively low levels of Myc (Z-Myc; Trp53flox/+; Ptenflox/flox) develop adenocarcinoma that expresses AR and luminal cytokeratins and metastasize to lymph nodes (Kim et al. 2012), whereas GEMMs having higher levels of Myc—namely, the BMPC model (for Hoxb13-MYC; Hoxb13-Cre; Ptenflox/flox)—develop invasive adenocarcinoma with prevalent distant metastases to lungs and liver, as well as to bone, albeit rarely (Hubbard et al. 2016). Tumors and metastases in BMPC mice express low levels of AR and Nkx3.1, but do not have sarcomatoid features that are common in other advanced prostate cancer GEMMs. Additionally, these BMPC mice have extensive copy number alterations, suggesting that higher levels of Myc promote genomic instability and thereby metastasis (Hubbard et al. 2016). Notably, the metastatic phenotype in the “rapid-cap” model based on combined loss of function of p53 and Pten also has activation of Myc (Cho et al. 2014), which is also the case for a GEMM based on Braf activation (see below and Wang et al. 2012).

TGF-β Signaling

SMAD4 is a downstream effector of the TGF-β signaling, which has been reported to be lost in some primary and advanced prostate cancers (∼3%; Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015). GEMMs based on combined conditional loss of function of Pten and Smad4 in prostate (PbCre4; Ptenflox/flox; Smad4flox/flox mice) develop aggressive adenocarcinoma with short latency, which express AR and luminal cytokeratins and develop distant metastases with relatively low penetrance (∼12%) (Ding et al. 2011), perhaps as a result of their early lethality. The further addition of conditional loss of function of p53 (PbCre4; Ptenflox/flox; Smad4flox/flox; Trp53flox/flox mice) together with telomerase deficiency was reported to result in bone metastasis (Ding et al. 2012), although further pathological inspection of the purported bone lesions suggested possible local invasion to bone rather than actual metastasis (Ittmann et al. 2013). Nonetheless, the relevance of TGF-β signaling for prostate tumorigenesis is supported by analyses of GEMMs based on both conditional gain and loss of expression of NR2F2 (COUP-TFII), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that inhibits Smad4-dependent transcription and promotes tumor progression and metastasis in Pten-based GEMMs (Qin et al. 2013).

Ras/Raf/MAPK Signaling Pathway

Although the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway is activated in ∼40% of primary prostate tumors and ∼90% of metastases (Taylor et al. 2010; Aytes et al. 2013), the relevant genomic alterations are unknown because KRAS and BRAF are rarely mutated either in prostate cancer (Cancer Genome Atlas Research 2015; Robinson et al. 2015), although they have been reported to be translocated in some cases (Palanisamy et al. 2010). Consequently, GEMMs based on activation of these pathways have been developed using mouse alleles that express conditionally activatable Kras or Braf in prostate (Jeong et al. 2008; Mulholland et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012; Aytes et al. 2013). Notably, these Kras- and Braf-based GEMMs have been reported to be inherently castration-resistant because their prostate tumors do not regress following ADT, which is consistent with earlier reports in human prostate cancer cells linking MAPK signaling to androgen independence (Voeller et al. 1991).

In particular, GEMMs expressing an activatable BrafV600E allele together with heterozygous germline loss of Nkx3.1 and conditional loss of function of Pten (Nkx3.1CreERT2/+; Pten flox/flox; BrafV600E/+; or NPB mice) develop invasive adenocarcinoma by 6 months of age, with moderate penetrance of metastasis primarily to lungs (Wang et al. 2012). Notably, a key feature of disease progression and metastasis in these NPB mice is activation of Myc, as well as Cyclin D1. Similarly, GEMMs expressing an activatable KrasG12D allele together with heterozygous germline loss of Nkx3.1 and conditional loss of function of Pten (Nkx3.1CreERT2/+; Pten flox/flox; KrasG12D/+; or NPK mice) develop invasive adenocarcinoma by 4 months of age with high penetrance of metastasis to lungs, liver, and other soft tissues (Aytes et al. 2013). Prostate tumors in the NPK mice retain luminal features but have heterogeneous AR expression and progress to a sarcomatoid-like differentiation. Additionally, GEMMs based on conditional gain of expression of nuclear receptor coactivator 2 (NCoA2), which is amplified in ∼16% of advanced prostate cancer (Robinson et al. 2015), in combination with loss of function of Pten develop invasive adenocarcinomas with distant metastasis, which is driven by hyperactivation of PI3K and MAPK pathways (Qin et al. 2014).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

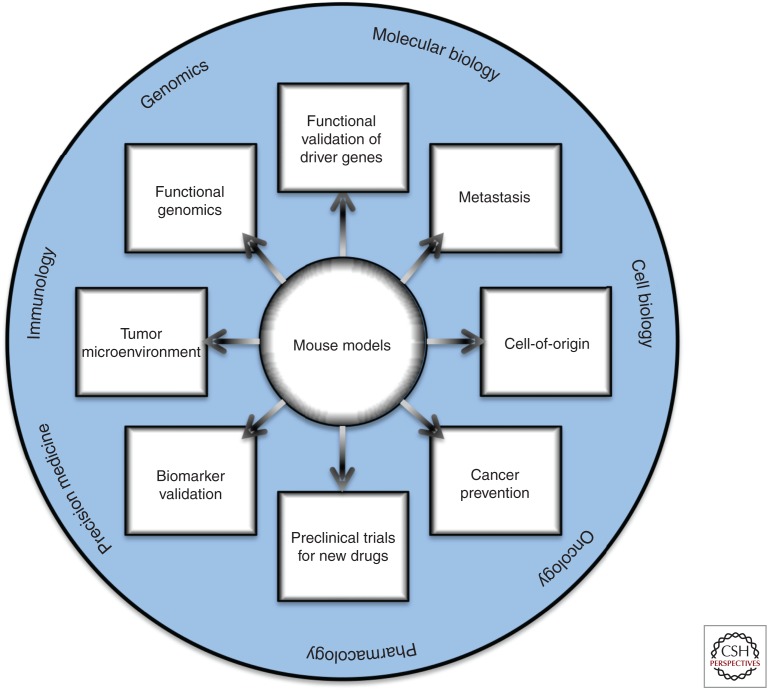

In summary, many of the GEMMs of prostate cancer that have been generated thus far nicely emulate the expected functional consequences of key genomic alterations associated with human prostate cancer progression and model important collaborations in disease progression. In certain cases, such as for Myc and Pten, the opportunity to study multiple independent GEMMs in combination with other relevant alleles has allowed for in-depth analyses of key biological features and molecular programs associated with prostate cancer progression (Fig. 2). For example, coclinical studies that test potential therapeutics in GEMMs and humans have advanced our understanding of the specificity of drug response (Lunardi et al. 2013) and the application to cancer prevention (Dutta et al. 2017). Additionally, technological advances have enabled the use of lineage tracing to precisely define the temporal and spatial development of cellular dissemination and metastasis (Aytes et al. 2013), as well as to elucidate cells of origin of cancer in their native microenvironment (Shibata and Shen 2015) and in response to treatment (Zou et al. 2017). Furthermore, the advent of robust technologies based on CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing have emerged as powerful tools to somatically edit the genome and epigenome, and will undoubtedly flourish in the next years to generate multiple complex alleles (Sanchez-Rivera and Jacks 2015).

Figure 2.

Uses of genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) to study prostate cancer. Potential areas of interest in which GEMMs can be used to study prostate cancer biology are highlighted inside rectangular boxes. The outer circle highlights the broad fields to which these studies can contribute relevant knowledge.

Studying these GEMMs has provided many valuable insights regarding the biology of the prostate and prostate cancer. For example, analyses of Nkx3.1 GEMM models of early stage prostate cancer have provided novel insights regarding the relationship of cellular specification and stem cell function in normal contexts for prostate cancer, have led to identification of novel biomarkers that distinguish indolent prostate cancer, and are useful for implementing secondary prevention (e.g., Wang et al. 2009; Irshad et al. 2013; Dutta et al. 2016, 2017). Similarly, analyses of Pten functions in prostate adenocarcinoma using GEMMs has provided novel insights into the relevance of cellular senescence, aging, and nutritional balance for cancer progression and has led to the elucidation of key signaling pathways and autophagy mechanisms associated with progression (e.g., Chen et al. 2005; Kalaany and Sabatini 2009; Lamming et al. 2012; Santanam et al. 2016). Furthermore, advanced bioinformatics approaches comparing GEMMs to human prostate cancer has informed on biomarkers of disease outcome, functional drivers of disease progression, and clinical features of treatment response and resistance (Irshad et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013b; Aytes et al. 2014; Mitrofanova et al. 2015; You et al. 2016).

However, there is still much to be done because important genomic alterations either have yet to be modeled or have not yet been optimally modeled. Clearly, the lack of GEMMs that recapitulate the critical role of AR in advanced prostate cancer and metastasis is a major area in need of future development. Another key area for future development are GEMMs based on DDR pathway components, which are altered in advanced prostate cancer and may have significant clinical implications, as evident from the preferential efficacy of PARP inhibitors on tumors with an altered DDR (Mateo et al. 2015). GEMMs that incorporate perturbation of stromal components and/or immune cells are likely to advance our understanding of their contribution to tumor progression or regression, as well as improve coclinical investigations, particularly for immunotherapy.

Last, there is a critical need for further development of models of advanced disease stages that can inform on human cancer treatment responses, including small-cell or neuroendocrine differentiation that emerges after treatment failure, as well as the biology of bone metastasis, which has been particularly elusive in current GEMMs. This is a key limitation that needs to be rectified for GEMMs to be wholly valuable to inform on clinically relevant disease. Thus, the future generation of GEMMs of prostate cancer awaits our further discovery of prostate cancer biology, mechanisms, and improved technologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.M.A. was supported by a Postdoctoral Training Award (W81XWH-15-1-0185) from the Department of Defense (DoD), Office of the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (CDMRP). C.A.S. acknowledges funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (R01 CA183929, R01 CA173481, and R01 CA196662), the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and the T.J. Martell Foundation for Leukemia, Cancer and AIDS Research. C.A.S. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor supported, in part, by a generous gift from the F.M. Kirby Foundation.

Footnotes

Editors: Michael M. Shen and Mark A. Rubin

Additional Perspectives on Prostate Cancer available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. 2000. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer. Genes Dev 14: 2410–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate-Shen C, Banach-Petrosky WA, Sun X, Economides KD, Desai N, Gregg JP, Borowsky AD, Cardiff RD, Shen MM. 2003. Nkx3.1; Pten mutant mice develop invasive prostate adenocarcinoma and lymph node metastases. Cancer Res 63: 3886–3890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulkadir SA, Magee JA, Peters TJ, Kaleem Z, Naughton CK, Humphrey PA, Milbrandt J. 2002. Conditional loss of Nkx3.1 in adult mice induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mol Cell Biol 22: 1495–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adissu HA, McKerlie C, Di Grappa M, Waterhouse P, Xu Q, Fang H, Khokha R, Wood GA. 2015. Timp3 loss accelerates tumour invasion and increases prostate inflammation in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Prostate 75: 1831–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PD, McKissic SA, Logan M, Roh M, Franco OE, Wang J, Doubinskaia I, van der Meer R, Hayward SW, Eischen CM, et al. 2012. Nkx3.1 and Myc crossregulate shared target genes in mouse and human prostate tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest 122: 1907–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytes A, Mitrofanova A, Kinkade CW, Lefebvre C, Lei M, Phelan V, LeKaye HC, Koutcher JA, Cardiff RD, Califano A, et al. 2013. ETV4 promotes metastasis in response to activation of PI3-kinase and Ras signaling in a mouse model of advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E3506–E3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytes A, Mitrofanova A, Lefebvre C, Alvarez MJ, Castillo-Martin M, Zheng T, Eastham JA, Gopalan A, Pienta KJ, Shen MM, et al. 2014. Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies a synergistic interaction between FOXM1 and CENPF that drives prostate cancer malignancy. Cancer Cell 25: 638–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, Park K, Kitabayashi N, MacDonald TY, Ghandi M, et al. 2013. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell 153: 666–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman SA, Ghazarian D, So K, Sanchez O, Wagner KU, Hennighausen L, Suzuki A, Tsao MS, Chapman WB, Stambolic V, et al. 2004. Early onset of neoplasia in the prostate and skin of mice with tissue-specific deletion of Pten. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 1725–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena E, Shao Z, Linn DE, Glass K, Hamblen MJ, Fujiwara Y, Kim J, Nguyen M, Zhang X, Godinho FJ, et al. 2013. ETV1 directs androgen metabolism and confers aggressive prostate cancer in targeted mice and patients. Genes Dev 27: 683–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri CE, Baca SC, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Blattner M, Theurillat JP, White TA, Stojanov P, Van Allen E, Stransky N, et al. 2012. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent SPOP, FOXA1 and MED12 mutations in prostate cancer. Nat Genet 44: 685–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belair CD, Paikari A, Moltzahn F, Shenoy A, Yau C, Dall’Era M, Simko J, Benz C, Blelloch R. 2015. DGCR8 is essential for tumor progression following PTEN loss in the prostate. EMBO Rep 16: 1219–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS, Sboner A, MacDonald TY, Wang Y, Sheikh KL, Terry S, Tagawa ST, et al. 2011. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov 1: 487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, Cyrta J, Marotz C, Giannopoulou E, Chakravarthi BV, Varambally S, et al. 2016. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med 22: 298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman-Booty LD, Knudsen KE. 2015. Models of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 22: R33–R49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berquin IM, Min Y, Wu R, Wu H, Chen YQ. 2005. Expression signature of the mouse prostate. J Biol Chem 280: 36442–36451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia-Gaur R, Donjacour AA, Sciavolino PJ, Kim M, Desai N, Young P, Norton CR, Gridley T, Cardiff RD, Cunha GR, et al. 1999. Roles for Nkx3.1 in prostate development and cancer. Genes Dev 13: 966–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner M, Liu D, Robinson BD, Huang D, Poliakov A, Gao D, Nataraj S, Deonarine LD, Augello MA, Sailer V, et al. 2017. SPOP mutation drives prostate tumorigenesis in vivo through coordinate regulation of PI3K/mTOR and AR signaling. Cancer Cell 31: 436–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojovic B, Crowe DL. 2013. Dysfunctional telomeres promote genomic instability and metastasis in the absence of telomerase activity in oncogene induced mammary cancer. Mol Carcinog 52: 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen C, Zheng T, Gelmann EP. 2015. NKX3.1 suppresses TMPRSS2-ERG gene rearrangement and mediates repair of androgen receptor-induced DNA damage. Cancer Res 75: 2686–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruxvoort KJ, Charbonneau HM, Giambernardi TA, Goolsby JC, Qian CN, Zylstra CR, Robinson DR, Roy-Burman P, Shaw AK, Buckner-Berghuis BD, et al. 2007. Inactivation of Apc in the mouse prostate causes prostate carcinoma. Cancer Res 67: 2490–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research. 2015. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell 163: 1011–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver BS, Tran J, Gopalan A, Chen Z, Shaikh S, Carracedo A, Alimonti A, Nardella C, Varmeh S, Scardino PT, et al. 2009. Aberrant ERG expression cooperates with loss of PTEN to promote cancer progression in the prostate. Nat Genet 41: 619–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, Koutcher JA, Scher HI, Ludwig T, Gerald W, et al. 2005. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 436: 725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Pratt CP, Zeeman ME, Schultz N, Taylor BS, O’Neill A, Castillo-Martin M, Nowak DG, Naguib A, Grace DM, et al. 2011. Identification of PHLPP1 as a tumor suppressor reveals the role of feedback activation in PTEN-mutant prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 20: 173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chi P, Rockowitz S, Iaquinta PJ, Shamu T, Shukla S, Gao D, Sirota I, Carver BS, Wongvipat J, et al. 2013. ETS factors reprogram the androgen receptor cistrome and prime prostate tumorigenesis in response to PTEN loss. Nat Med 19: 1023–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Herzka T, Zheng W, Qi J, Wilkinson JE, Bradner JE, Robinson BD, Castillo-Martin M, Cordon-Cardo C, Trotman LC. 2014. RapidCaP, a novel GEM model for metastatic prostate cancer analysis and therapy, reveals myc as a driver of Pten-mutant metastasis. Cancer Discov 4: 318–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg NJ, Couto SS, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Carver BS, Taylor BS, Ellwood-Yen K, Gerald WL, Sander C, Sawyers CL. 2011. MYC cooperates with AKT in prostate tumorigenesis and alters sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors. PLoS ONE 6: e17449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleutjens KB, van der Korput HA, Ehren-van Eekelen CC, Sikes RA, Fasciana C, Chung LW, Trapman J. 1997a. A 6-kb promoter fragment mimics in transgenic mice the prostate-specific and androgen-regulated expression of the endogenous prostate-specific antigen gene in humans. Mol Endocrinol 11: 1256–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleutjens KB, van der Korput HA, van Eekelen CC, van Rooij HC, Faber PW, Trapman J. 1997b. An androgen response element in a far upstream enhancer region is essential for high, androgen-regulated activity of the prostate-specific antigen promoter. Mol Endocrinol 11: 148–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto SS, Cao M, Duarte PC, Banach-Petrosky W, Wang S, Romanienko P, Wu H, Cardiff RD, Abate-Shen C, Cunha GR. 2009. Simultaneous haploinsufficiency of Pten and Trp53 tumor suppressor genes accelerates tumorigenesis in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Differentiation 77: 103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR. 2008. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions: Past, present, and future. Differentiation 76: 578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Donjacour AA, Cooke PS, Mee S, Bigsby RM, Higgins SJ, Sugimura Y. 1987. The endocrinology and developmental biology of the prostate. Endocr Rev 8: 338–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardenne E, Beltran H, Benelli M, Gayvert K, Berger A, Puca L, Cyrta J, Sboner A, Noorzad Z, MacDonald T, et al. 2016. N-Myc induces an EZH2-mediated transcriptional program driving neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 30: 563–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff DJ, Grabowska MM, Case TC, Yu X, Herrick MK, Hayward WJ, Strand DW, Cates JM, Hayward SW, Gao N, et al. 2014. FOXA1 deletion in luminal epithelium causes prostatic hyperplasia and alteration of differentiated phenotype. Lab Invest 94: 726–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. 1998. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet 19: 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, De Acetis M, Koff A, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. 2001. Pten and p27KIP1 cooperate in prostate cancer tumor suppression in the mouse. Nat Genet 27: 222–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Wu CJ, Chu GC, Xiao Y, Ho D, Zhang J, Perry SR, Labrot ES, Wu X, Lis R, et al. 2011. SMAD4-dependent barrier constrains prostate cancer growth and metastatic progression. Nature 470: 269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Wu CJ, Jaskelioff M, Ivanova E, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, Chu GC, Wang G, Lu X, Labrot ES, et al. 2012. Telomerase reactivation following telomere dysfunction yields murine prostate tumors with bone metastases. Cell 148: 896–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Le Magnen C, Mitrofanova A, Ouyang X, Califano A, Abate-Shen C. 2016. Identification of an NKX3.1-G9a-UTY transcriptional regulatory network that controls prostate differentiation. Science 352: 1576–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Panja S, Virk RK, Kim JY, Zott R, Cremers S, Golombos DM, Liu D, Mosquera JM, Mostaghel EA, et al. 2017. Co-clinical analysis of a genetically engineered mouse model and human prostate cancer reveals significance of NKX3.1 expression for response to 5α-reductase inhibition. Eur Urol 72: 499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood-Yen K, Graeber TG, Wongvipat J, Iruela-Arispe ML, Zhang J, Matusik R, Thomas GV, Sawyers CL. 2003. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell 4: 223–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing CM, Ray AM, Lange EM, Zuhlke KA, Robbins CM, Tembe WD, Wiley KE, Isaacs SD, Johng D, Wang Y, et al. 2012. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N Engl J Med 366: 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floc’h N, Kinkade CW, Kobayashi T, Aytes A, Lefebvre C, Mitrofanova A, Cardiff RD, Califano A, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. 2012. Dual targeting of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway inhibits castration-resistant prostate cancer in a genetically engineered mouse model. Cancer Res 72: 4483–4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis JC, McCarthy A, Thomsen MK, Ashworth A, Swain A. 2010. Brca2 and Trp53 deficiency cooperate in the progression of mouse prostate tumourigenesis. PLoS Genet 6: e1000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis JC, Thomsen MK, Taketo MM, Swain A. 2013. β-catenin is required for prostate development and cooperates with Pten loss to drive invasive carcinoma. PLoS Genet 9: e1003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser M, Sabelnykova VY, Yamaguchi TN, Heisler LE, Livingstone J, Huang V, Shiah YJ, Yousif F, Lin X, Masella AP, et al. 2017. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature 541: 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Ouyang X, Banach-Petrosky W, Borowsky AD, Lin Y, Kim M, Lee H, Shih WJ, Cardiff RD, Shen MM, et al. 2004. A critical role for p27kip1 gene dosage in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 17204–17209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Ouyang X, Banach-Petrosky WA, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. 2006. Emergence of androgen independence at early stages of prostate cancer progression in Nkx3.1; Pten mice. Cancer Res 66: 7929–7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Zhan Y, Di W, Moore AR, Sher JJ, Guan Y, Wang S, Zhang Z, Murphy DA, Sawyers CL, et al. 2016. A Tmprss2-CreERT2 knock-in mouse model for cancer genetic studies on prostate and colon. PLoS ONE 11: e0161084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Blando JM, Perez CJ, Abba MC, Benavides F, Kazanietz MG. 2017. Protein kinase C Epsilon cooperates with PTEN loss for prostate tumorigenesis through the CXCL13-CXCR5 pathway. Cell Rep 19: 375–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Morton RA, Boyce BF, DeMayo FJ, Finegold MJ, Angelopoulou R, Rosen JM, Greenberg NM. 1996. Metastatic prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Cancer Res 56: 4096–4102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Kattan MW, Nahm HS, Finegold MJ, Greenberg NM. 1997. Androgen-independent prostate cancer progression in the TRAMP model. Cancer Res 57: 4687–4691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska MM, DeGraff DJ, Yu X, Jin RJ, Chen Z, Borowsky AD, Matusik RJ. 2014. Mouse models of prostate cancer: Picking the best model for the question. Cancer Metastasis Rev 33: 377–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, Quist MJ, Jing X, Lonigro RJ, Brenner JC, et al. 2012. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 487: 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg NM, DeMayo FJ, Sheppard PC, Barrios R, Lebovitz R, Finegold M, Angelopoulou R, Dodd JG, Duckworth ML, Rosen JM, et al. 1994. The rat probasin gene promoter directs hormonally and developmentally regulated expression of a heterologous gene specifically to the prostate in transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol 8: 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Saitoh M, Kinkel S, Crosby K, Sheen JH, Mullholland DJ, Magnuson MA, Wu H, Sabatini DM. 2009. mTOR complex 2 is required for the development of prostate cancer induced by Pten loss in mice. Cancer Cell 15: 148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Buchanan G, Ittmann M, Harris JM, Yu X, Demayo FJ, Tilley W, Greenberg NM. 2005. Mutation of the androgen receptor causes oncogenic transformation of the prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard GK, Mutton LN, Khalili M, McMullin RP, Hicks JL, Bianchi-Frias D, Horn LA, Kulac I, Moubarek MS, Nelson PS, et al. 2016. Combined MYC activation and Pten loss are sufficient to create genomic instability and lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res 76: 283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner A, Mulholland DJ, Standen CL, Karasarides M, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Barrett T, Chi H, Greiner DL, Tournier C, Sawyers CL, et al. 2012. JNK and PTEN cooperatively control the development of invasive adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 12046–12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad S, Abate-Shen C. 2013. Modeling prostate cancer in mice: Something old, something new, something premalignant, something metastatic. Cancer Metastasis Rev 32: 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad S, Bansal M, Castillo-Martin M, Zheng T, Aytes A, Wenske S, Le Magnen C, Guarnieri P, Sumazin P, Benson MC, et al. 2013. A molecular signature predictive of indolent prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med 5: 202ra122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittmann M, Huang J, Radaelli E, Martin P, Signoretti S, Sullivan R, Simons BW, Ward JM, Robinson BD, Chu GC, et al. 2013. Animal models of human prostate cancer: The consensus report of the New York meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee. Cancer Res 73: 2718–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Laboratory. 1975. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. Dover, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JH, Wang Z, Guimaraes AS, Ouyang X, Figueiredo JL, Ding Z, Jiang S, Guney I, Kang GH, Shin E, et al. 2008. BRAF activation initiates but does not maintain invasive prostate adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 3: e3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, Zhang J, Signoretti S, Loda M, Roberts TM, et al. 2008. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110β in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature 454: 776–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin RJ, Lho Y, Connelly L, Wang Y, Yu X, Saint Jean L, Case TC, Ellwood-Yen K, Sawyers CL, Bhowmick NA, et al. 2008. The nuclear factor-κB pathway controls the progression of prostate cancer to androgen-independent growth. Cancer Res 68: 6762–6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaany NY, Sabatini DM. 2009. Tumours with PI3K activation are resistant to dietary restriction. Nature 458: 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Sheppard PC, Yan Y, Pettigrew N, Borowsky AD, Prins GS, Dodd JG, Duckworth ML, Matusik RJ. 1998. Development, progression, and androgen-dependence of prostate tumors in probasin-large T antigen transgenic mice: A model for prostate cancer. Lab Invest 78: 319–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Bhatia-Gaur R, Banach-Petrosky WA, Desai N, Wang Y, Hayward SW, Cunha GR, Cardiff RD, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. 2002a. Nkx3.1 mutant mice recapitulate early stages of prostate carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 62: 2999–3004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Cardiff RD, Desai N, Banach-Petrosky WA, Parsons R, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. 2002b. Cooperativity of Nkx3.1 and Pten loss of function in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 2884–2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Eltoum IE, Roh M, Wang J, Abdulkadir SA. 2009. Interactions between cells with distinct mutations in c-MYC and Pten in prostate cancer. PLoS Genet 5: e1000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Roh M, Doubinskaia I, Algarroba GN, Eltoum IE, Abdulkadir SA. 2012. A mouse model of heterogeneous, c-MYC-initiated prostate cancer with loss of Pten and p53 Oncogene 31: 322–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JC, Xu J, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Carver BS, Leung DH, Taylor BS, Sander C, Cardiff RD, Couto SS, et al. 2009. Cooperativity of TMPRSS2-ERG with PI3-kinase pathway activation in prostate oncogenesis. Nat Genet 41: 524–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klezovitch O, Risk M, Coleman I, Lucas JM, Null M, True LD, Nelson PS, Vasioukhin V. 2008. A causal role for ERG in neoplastic transformation of prostate epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 2105–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppens MA, Tanger E, Nacerddine K, Westerman B, Song JY, van Lohuizen M. 2017. A new transgenic mouse model for conditional overexpression of the Polycomb Group protein EZH2. Transgenic Res 26: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]