Abstract

Hypertension affects the vast majority of patients with CKD and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, ESKD, and death. Over the past decade, a number of hypertension guidelines have been published with varying recommendations for BP goals in patients with CKD. Most recently, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2017 hypertension guidelines set a BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg for patients with CKD and others at elevated cardiovascular risk. These guidelines were heavily influenced by the landmark Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), which documented that an intensive BP goal to a systolic BP <120 mm Hg decreased the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in nondiabetic adults at high cardiovascular risk, many of whom had CKD; the intensive BP goal did not retard CKD progression. It is noteworthy that SPRINT measured BP with automated devices (5-minute wait period, average of three readings) often without observers, a technique that potentially results in BP values that are lower than what is typically measured in the office. Still, results from SPRINT along with long-term follow-up data from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension suggest that a BP goal <130/80 mm Hg will reduce mortality in patients with CKD. Unfortunately, data are more limited in patients with diabetes or stage 4–5 CKD. Increased adverse events, including electrolyte abnormalities and decreased eGFR, necessitate careful laboratory monitoring. In conclusion, a BP goal of <130/80 is a reasonable, evidence-based BP goal in patients with CKD. Implementation of this intensive BP target will require increased attention to measuring BP accurately, assessing patient preferences and concurrent medical conditions, and monitoring for adverse effects of therapy.

Keywords: blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, clinical hypertension, clinical, nephrology, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Hypertension increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, and ESKD, and is a leading contributor to morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). According to 2010 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 84% of adults with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 had hypertension, yet only 32% had BP controlled <140/90 mm Hg (2). Over the past half century, many pivotal hypertension trials have been published. However, methods for BP measurement and evidence-based guideline development have changed over time, leading to ongoing debate on target BP goals in the general population and special populations such as patients with CKD (3–5). In 2015, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) found that targeting a systolic BP <120 mm Hg reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in patients at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease, 28% of whom had CKD (6). However, SPRINT measured BP with automated devices (5-minute wait period, average of three readings) often unattended by observers, a technique that differs from most routine office BP measurements (7). Here, we review the practice of BP measurement, results of trials that assessed higher versus lower BP goals in patients with CKD, and hypertension treatment guidelines.

Hypertension Guidelines

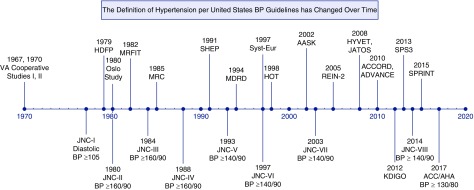

The definition of hypertension and the thresholds for treatment have been continually refined as new hypertension research accumulates (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1) (8). In 1977, the first Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP (JNC-I) report recommended antihypertensive medication treatment for patients with diastolic BP ≥105 mm Hg (9). Risk stratification by target organ damage was emphasized in JNC-V (1993) and JNC-VI (1997), with JNC-VI recommending a BP target of <130/85 for patients with nonproteinuric kidney disease and <125/75 mm Hg for proteinuric kidney disease (10,11). JNC-VII (2003) later revised the BP target to <130/80 mm Hg for all patients with CKD, defined as eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or albuminuria ≥300 mg/d (3). Guidelines from 2012 to 2014 interpreted evidence differently and published recommendations with disparate BP goals for patients with CKD. In 2012, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines recommended the <130/80 mm Hg target only for those with albuminuric (albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g) CKD (12), whereas the 2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology (ESH/ESC) and the report from the panel members appointed to JNC-8 recommended a BP target of <140/90 mm Hg for CKD, regardless of albuminuria (5,13).

Figure 1.

The Definition of Hypertension per United States BP Guidelines has Changed Over Time. Above timeline: major hypertension trials from 1960 to 2018 (6,34–37,39,55–66). Below timeline: guideline and definition of hypertension, from 1960 to 2018 (3–5,9–11,14,67–69). ADVANCE, The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Controlled Evaluation trial; ALLHAT, The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial; HDFP, The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HOT, The Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; HTN, Hypertension; HYVET, The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; JATOS, The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic BP in Elderly Hypertensive Patients; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; MRC, Medical Research Council; MRFIT, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial; SHEP, The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; SPS3, The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes trial; Syst-Eur, The Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; UKPDS, The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; VA, Veterans Affairs.

In September 2015, SPRINT was halted early because of interim analyses demonstrating that the group assigned to a systolic BP goal <120 mm Hg had a 25% lower risk of cardiovascular disease and 27% lower risk of all-cause mortality than the group assigned to a systolic BP <140 mm Hg (6). Subsequently, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2017 Hypertension guidelines redefined hypertension as BP ≥130/80 mm Hg and recommended antihypertensive treatment to a BP goal of <130/80 mm Hg in patients with CKD and others at increased cardiovascular risk (14). The rationale provided by the ACC/AHA guidelines committee in choosing a systolic BP target of <130 mm Hg rather than <120 mm Hg (the intensive goal in SPRINT), included concerns about applying SPRINT to a broader population and considerations related to unattended, automated BP measurements in SPRINT, which on average might be lower than routine clinic measurements. The recently published 2018 ESH/ESC guidelines recommend a target systolic BP of 130–139 mm Hg and diastolic BP of 70–79 mm Hg for patients with CKD (15).

BP Measurement Techniques

Given the controversy over BP targets, it is important to briefly discuss BP measurement techniques, a topic that has been recently reviewed by Thomas and Drawz (16). Methods of measuring BP were primarily developed and refined in the late 1800s and early 1900s, including a 1905 communication by Nicolai Korotkoff describing the auscultatory method (17). By 1925, BP measurements from manual observers using auscultatory devices demonstrated a direct association of systolic and diastolic BP with risk of death in analyses of data from life insurance companies (8). Although many practices continue to use manual auscultatory techniques to measure office BP, their limitations are well known, including digit preference, discrepancies of office BP with home or ambulatory BP (i.e., white-coat effect and masked hypertension), and the need for training and retraining of manual observers (18). A multitude of manufacturers have developed automated, oscillometric BP devices, which often include preprogrammed wait times and multiple readings to improve precision (16,19). Validation protocols for oscillometric devices have been developed by organizations such as the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation and the European Society of Hypertension; it is unclear if separate validation is required for patients with CKD or ESKD who may have increased arterial stiffness (20,21).

Comparisons of Different Techniques to Measure Office BP

Few studies have directly compared BP measurement approaches in routine clinical settings. In a cluster-randomized trial of 555 patients with hypertension in 67 clinics in Eastern Canada, clinics were randomized to continue using manual office BP (control) versus unattended automated office BP with the BpTRU device, which takes an initial “test” reading without a wait period, then averages the next five BP readings, taken at 2-minute intervals (19). Randomization to automated office BP clinics was associated with 5.4 mm Hg lower systolic BP compared with control (manual BP) clinics. Unfortunately, the BpTRU device is no longer available. No similar randomized trials testing the effect of implementation of automated office BP using Omron HEM-907 with manual office BP technique exist, although limited data suggests it would similarly reduce the white-coat effect (22). Because some differences in office BP have been observed when measured at the same visit by different automated devices, clinics should use only one type of automated device (23,24).

Comparisons of Office BP and Ambulatory BP

Besides eliminating the white-coat effect, another advantage of automated office BP over manual BP is that it appears to correlate better with ambulatory BP, which is particularly relevant for patients with CKD, who are at increased risk of elevated nocturnal BP and nondipping status (25,26). In the trial by Myers et al. (19) automated office BP measured by BpTRU only slightly overestimated daytime ambulatory BP (2.3/3.3 mm Hg), whereas manual office BP considerably overestimated daytime ambulatory BP (6.5/4.3 mm Hg). In a meta-analysis of 19 studies with automated office BP measured by BpTRU and ambulatory BP monitoring, mean automated office BP did not differ significantly from daytime ambulatory BP (systolic BP −1.52 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −3.29 to 0.25 mm Hg; diastolic BP 0.33 mm Hg, 95% CI, −0.97 to 1.64), although there was significant heterogeneity with study-level differences ranging from −9.7 to 9 mm Hg in mean systolic BP and −4 to 6 mm Hg in mean diastolic BP (27).

Similar data are available comparing automated office BP measured by the Omron HEM-907 XL device with ambulatory BP in a SPRINT ancillary study of 897 participants (28). In the standard arm, mean automated office BP (measured by the Omron HEM-907 XL) was 135.5/73.6 mm Hg compared with daytime ambulatory BP of 138.8/78.6 mm Hg. However, in the intensive arm, mean automated office BP was 119.7/65.9 mm Hg compared with daytime ambulatory BP of 126.5/72.0 mm Hg (28). Similarly, in a study of 275 male veterans with CKD and automated office BP (measured with the Omron HEM-907 XL) <140/90 mm Hg, mean automated office BP was 121.7/59.7 compared with daytime ambulatory BP of 129.6/71.5 mm Hg (22). Despite these apparent differences at the lower normotensive range, both automated office BP and ambulatory BP correlate more strongly with left ventricular hypertrophy than routinely measured office BP (22,29).

In summary, use of automated office BP reduces the white-coat effect and correlates better with cardiovascular and kidney risk relative to routinely measured clinic BP. Thus, if lower BP goals are targeted, it may be prudent to use automated office BP devices, although workflow redesign must be carefully considered (30). Increasing adoption of automated office BP devices is occurring in Canada. In a survey of Canadian primary care physicians, 43% reported using automated office BP to screen for hypertension, as recommended by Hypertension Canada guidelines (31,32).

What Is the Evidence for Lower BP Goals in CKD?

Three major BP trials specifically in participants with CKD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] study, African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension [AASK], and the Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy trial 2 [REIN-2]) have been conducted. Each focused on kidney outcomes as the primary outcome; none were powered to detect differences in cardiovascular outcomes. In a meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials of BP lowering in patients with stage 3–5 CKD, mean systolic BP dropped by 16–132 mm Hg in the more intensive arms and by 8–140 mm Hg in the less intensive arms (33). More intensive BP lowering reduced the risk of death by 14% (odds ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.97). However, conclusions on specific BP goals could not be made because of heterogeneity in study designs. Data from BP trials that have included a large number of patients with CKD are shown in Table 1 (6,33–41).

Table 1.

Kidney, cardiovascular, and mortality outcomes in randomized BP trials with at least 300 patients with CKD

| Study, Year, BP Method (Ref) | Intervention, Follow-Up Time | Study Population with CKD | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Baseline BP, mm Hg | Achieved Systolic BP Difference, mm Hg | Kidney Outcomes for CKD Subgroup, More versus Less Intensive BP Lowering | CVD or Death Outcomes for CKD Subgroup, More versus Less Intensive BP Lowering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trials with a subset of participants with CKD | |||||||

| SHEP, 1991, random zero sphygmomanometer (33,61) | Drug versus placebo, mean 4.5 yr | 1735/4736 (37%) with eGFR<60 | Age ≥60 yr with isolated systolic HTN (systolic BP 160–219, diastolic BP <90 mm Hg) | 170/77 | 142 versus 153 | Not reported | All-cause death OR, 0.90 (95% CI: 0.67–1.21) |

| Exclusion: major CVD, “established kidney dysfunction” | |||||||

| Syst-Eur, 1997, method not specified (33,39) | Drug(s) versus placebo, median 2.0 yr | 470/4695 (10%) with eGFR<60 | Age ≥60 yr with isolated systolic HTN and Cr≤2.0 mg/dl Exclusion: hypertensive retinopathy, CHF, recent stroke/MI, severe CVD or non-CVD |

174/86 | 151 versus 161 | Not reported | All-cause death OR, 0.83 (95% CI: 0.47–1.45) |

| HOT, 1998, oscillometric visomat OZ (33,62) | Diastolic BP ≤80 versus diastolic BP ≤85 or ≤90 mm Hg, mean 3.8 yr | 3619/18,790 (19%) with eGFR<60 | Age 50–80 yr with HTN (diastolic BP 100–115 mm Hg) and Cr<3 mg/dl | 170/105 | 139 versus 142 | Not reported | All-cause death OR, 0.99 (95% CI: 0.70–1.41) |

| Exclusion: Cr≥3.0 mg/dl | |||||||

| HYVET, 2008, mercury sphygmomanometer or validated automated devices (33,63) | Drug versus placebo, median 1.8 yr | 1604/3845 (42%) with eGFR<60 | Age 80+yr with systolic BP ≥160 mm Hg and Cr<1.7 mg/dl Exclusion: CHF, dementia |

173/91 | 143 versus 158 | Not reported | All-cause death OR, 0.68 (95% CI: 0.50–0.91) |

| JATOS, 2008, unspecified sphygmomanometer (64) | Systolic BP <140 versus 140–159, mean 2.0 yr | 2499/4418 (57%) with eGFR <60 | Age 65–85 yr with systolic BP ≥160 mm Hg and Cr<1.5 mg/dl Exclusion: diastolic BP ≥120 mm Hg, recent stroke, MI, CHF, arrhythmia, retinopathy, poorly controlled diabetes |

172/89 | 136 versus 146 | Doubling of creatinine or ESKD; HR, 0.64 (95% CI: 0.21–1.97) | Not reported |

| ADVANCE, 2010, automated device (Omron HEM-705CP) (70) | Drug versus placebo, mean 4.3 yr | 4515/11,140 (41%) with CKD (2482 stage 1–2, 2033 stage 3+) | Age ≥55+yr with T2DM and major CVD or ≥1 CVD risk factor Exclusion: definite indication for long-term insulin therapy |

Stage 1–2 CKD 148/82 | Stage 1–2 CKD: 138 versus 142 | Composite kidney outcome (incident macroalbuminuria, doubling of creatinine, ESKD, or kidney death) | Stage CKD 1–2: composite CVD HR, 0.87 (95% CI: 0.69–1.12); all-cause death HR, 0.87 (95% CI: 0.67–1.12) |

| Stage 3+ CKD 147/80 | Stage 3+ CKD: 137 versus 142 | Stage CKD 1–2 HR, 0.69 (95% CI: 0.51–0.93); CKD 3+ HR, 0.93 (95% CI: 0.66–1.31) | Stage CKD 3+: composite CVD HR, 0.87 (95% CI: 0.68–1.10); all-cause death HR, 0.87 (95% CI: 0.68–1.12) | ||||

| ACCORD, 2010, automated device (Omron HEM-907) (45) | Systolic BP <120 versus systolic BP <140, mean 4.7 yr | 1726/4733 (36%) with CKD (1325 stage 1–2, 401 stage 3) | Age ≥40 yr with T2DM and Cr≤1.5 mg/dl Exclusion: BMI≥45 kg/m2, other serious illness |

142/76 | 122 versus 134 | Not reported | Composite CVD HR, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.67–1.11); all-cause death HR, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.63–1.16) |

| SPS3, 2013, automated device (Colin 8800C) (33,66) | Systolic BP <130 versus systolic BP 130–149, median 3.0 yr | 411/2916 (14%) | Age ≥30 yr with recent lacunar stroke and eGFR≥40 | 143/78 | 137 versus 126 | Not reported | All-cause death HR, 0.85 (95% CI: 0.47–1.54) |

| Exclusion: cardio-embolic source, ipsilateral carotid stenosis ≥50%, evidence of previous cortical stroke, moderate to severe disability | |||||||

| SPRINT 2015, automated device (Omron HEM-907) (46) | systolic BP <120 versus systolic BP <140, median 3.3 yr | 2646/9361 (28%) with eGFR 20–59 | Age ≥50 yr at elevated CVD risk with systolic BP 130–180 Exclusion: diabetes, ADPKD, prior stroke, symptomatic CHF, LVEF <35% |

140/78 | 123 versus 135 | 50% eGFR decline or ESKD HR, 0.89 (95% CI: 0.42–1.87); | Composite CVD HR, 0.81 (95% CI: 0.63–1.05) |

| 40% eGFR decline HR, 1.51 (95% CI: 0.83–2.68); | All-cause death HR, 0.72 (95% CI: 0.53–0.99) | ||||||

| 30% eGFR decline HR, 2.03 (95% CI: 1.42–2.91) | |||||||

| CKD trials (trial phase only) | |||||||

| MDRD, 1994, random zero sphygmomanometer (35) | MAP<92 versus MAP<107, mean 2.2 yr | 840 with predominantly nondiabetic CKD (Cr 1.4–7 for men and Cr 1.2–7.0 mg/dl for women) | Age 18–70 yr Exclusion: diabetes requiring insulin, class III-IV CHF |

131/80 | 126 versus 134 | No difference in mean GFR slope overall, but suggested MAP<92 target beneficial for those with proteinuria >1 g/d | All-cause death OR, 1.37 (95% CI: 0.68–2.74) |

| AASK, 2002, random zero sphygmomanometer (34) | MAP <92 versus MAP 102–107 mm Hg, median 3.8 yr | 1094 (100%) black adults with CKD attributed to HTN and GFR 20–65 | Exclusion: diastolic BP <95 mm Hg, CKD etiology other than HTN, clinical CHF | 151/96 | 130 versus 141 | No difference in mean GFR slope or clinical composite kidney outcome (50% GFR decline, ESKD, or death) | All-cause death OR, 0.87 (95% CI: 0.55–1.38) |

| REIN-2, 2005, unspecified sphygmomanometer (37) | Diastolic BP <90 with felodipine versus BP <130/80, median 1.3 yr | 335 adults with proteinuric CKD not due to diabetes (proteinuria 1–3 g/d and eGFR <45 or proteinuria >3 g/d and eGFR <70) | Age 18–70 yr Exclusion: immunosuppression treatment, severe uncontrolled HTN, recent MI or CVA, renovascular disease |

137/84 | 130 versus 134 | ESKD HR, 1.00 (95% CI: 0.61–1.64) | All-cause death OR, 0.67 (95% CI: 0.11–4.04) |

| HALT-PKD, 2014, automated home BP device (Lifesource) (71) | BP 95/6–110/75 versus BP 120/70–130/80, mean 5.7 yr | 558 hypertensive (BP ≥130/80) adults 15–49 yr with ADPKD and eGFR >60 | Exclusion: kidney vascular disease, kidney disease other than ADPKD | Home BP 124/83 | Home systolic BP difference 13.4 | Annualized change in kidney volume (5.6% versus 6.6%; P=0.006), eGFR (−2.9 versus −3.0; P=0.6), albuminuria (−3.77% versus +2.43%; P<0.001) | Decreased left ventricular mass index (−1.17 versus −0.57 g/m2 per yr; P<0.001) |

| All-cause death: 2 in intensive arm, 0 in control arm | |||||||

| CKD trials (extended observational follow-up) | |||||||

| AASK, 2010, random zero sphygmomanometer (43) | MAP<92 versus MAP 102–107, range 8.8–12.2 yr from trial start | 1094 black, nondiabetic adults with HTN and GFR 20–65 | Exclusion: diastolic BP <95 mm Hg, CKD etiology other than HTN, clinical CHF | 151/96 | During trial: 130 versus 141 | CKD progression (doubling creatinine, ESKD, or death): overall HR, 0.91 (95% CI: 0.77–1.08) | Not reported |

| During cohort phase: 131 versus 134 | PCR≥0.22 g/g subgroup: HR, 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58–0.93) PCR<0.22 g/g subgroup: HR, 1.18 (95% CI: 0.93–1.50) | ||||||

| AASK, 2017, random zero sphygmomanometer (44) | MAP <92 versus MAP 102–107, median 14.4 yr from trial start | 1067 black, nondiabetic adults with HTN and GFR 20–65 | Exclusion: Diastolic BP <95 mm Hg, CKD etiology other than HTN, clinical CHF | 151/96 | During trial: 130 versus 141 | ESKD: unadjusted HR, 0.92 (95% CI: 0.75–1.12) | All-cause death: unadjusted HR, 0.92 (95% CI: 0.77–1.10); adjusted HR, 0.81 (95% CI: 0.68–0.98) |

| During cohort phase: 131 versus 134 | Adjusted HR, 0.95 (95% CI: 0.78–1.16) | ||||||

| MDRD, 2017, random zero sphygmomanometer (44) | MAP <92 versus MAP <107, median 19.3 yr from trial start | 840 adults 18–70 yr with predominantly nondiabetic CKD (Cr 1.4–7 for men and Cr 1.2–7.0 mg/dl for women) | Exclusion: diabetes requiring insulin, class III-IV CHF | Before trial 131/80 | During trial: 126 versus 134 | ESKD unadjusted HR, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.73–1.00) | All-cause death: unadjusted HR, 0.82 (95% CI: 0.68–0.98); |

| 9 months after trial completion: difference of 8 mm Hg | Adjusted HR, 0.80 (95% CI: 0.66–0.96) | ||||||

SHEP, The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; HTN, hypertension; CVD, cardiovascular disease; OR, odds ratio; Syst-Eur, The Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; Cr, creatinine; CHF, congestive heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; HOT, The Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; HYVET, The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; JATOS, The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic BP in Elderly Hypertensive Patients; HR, hazard ratio; ADVANCE, The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Controlled Evaluation trial; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; ACCORD, Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes; SPS3, The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes trial; BMI, body mass index; SPRINT, Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MAP, mean arterial pressure; AASK, African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension; REIN-2, Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy trial 2; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; HALT-PKD, Halt Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease; PCR, protein-creatinine ratio; Ref, reference.

The first large, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate a lower BP target in CKD was the MDRD study, which randomized 840 adults with nondiabetic CKD to a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of <92 mm Hg (approximately 125/75) or to a standard goal (102–107 mm Hg, approximately 135/85–140/90) (Table 1) (35). The primary outcome was rate of GFR decline. Overall, intensive BP lowering had no significant effect on CKD progression, although the rate of GFR decline varied by baseline proteinuria. Among participants with proteinuria >1 g/d, participants randomized to the intensive arm experienced slower GFR decline than those in the standard BP arm; no benefit with intensive BP lowering was seen in those with proteinuria <1 g/d (42). This interaction was significant in eGFR 25–55 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n=585) and eGFR 13–24 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n=255) subgroups. A limitation of the MDRD study is the potential for confounding of BP goal with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use (51% of intensive arm participants, 32% of standard arm participants). After the MDRD study, the AASK and REIN-2 trials were published in 2002 and 2005, respectively; the primary analyses of these trials found no evidence that intensive BP lowering to goals <130/80 decreased the risk of CKD progression (34,37) (Table 1). It is important to emphasize that all of these trials were very short in duration, with an average of just 1.3–3.8 years of active treatment.

In AASK, 1094 black participants with CKD (mean GFR 46 ml/min per 1.73 m2) attributed to hypertension were randomized to an intensive BP lowering goal (MAP<92 mm Hg) versus standard goal (MAP 102–107 mm Hg) (Table 1). After completion of the main trial, there was a cohort phase to examine long-term effects of intensive BP lowering (43). At the onset of the AASK cohort phase, all participants were switched to ramipril and a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg; the BP goal was later reduced to <130/80 mm Hg in 2004 because of the JNC-7 guidelines. Over long-term follow-up, participants randomized to intensive BP lowering did not have a decreased risk of the primary composite outcome (doubling of creatinine, ESKD, or death; hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI: 0.77–1.08). However, there was a significant interaction by baseline proteinuria. Among those with baseline protein-to-creatinine ratio ≥0.22 g/g, randomization to the intensive BP arm during the trial phase was associated with reduced risk of the primary outcome (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.93), whereas no benefit for intensive BP control was observed in patients with protein-to-creatinine ratio <0.22 g/g (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.50). A combined analysis of MDRD study and AASK long-term follow-up data documented that participants who were randomized to intensive BP lowering tended to be at decreased risk of ESKD (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.00) and death (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.99) (44).

Data on the effects of a lower BP goal on outcomes in patients with CKD attributed to diabetes are sparse. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes (ACCORD) trial examined the effect of more intensive versus usual BP goal (systolic BP <120 mm Hg versus <140 mm Hg) on the risk of cardiovascular disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death) in 4733 participants with type 2 diabetes; 1325 (28%) had stage 1–2 CKD and 401 (8%) had stage 3 CKD (36). Intensive BP lowering did not significantly reduce the risk of the primary cardiovascular outcome (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.06), but did reduce the risk of stroke, a secondary outcome, by 41%. However, the ACCORD trial was underpowered as the annualized cardiovascular event rate was far lower than expected (2.1% versus expected 4%). In the subgroup of 1726 adults with CKD, the HR for the primary cardiovascular outcome was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.67 to 1.11) (Table 1) (45).

In 2015, the results of SPRINT were published (6). Briefly, SPRINT randomized 9361 adults ≥50 years with systolic BP 130–180 mm Hg and elevated cardiovascular risk to goal systolic BP <120 versus <140 mm Hg. Patients with diabetes, stroke, heart failure, proteinuria >1 g/d, polycystic kidney disease, eGFR<20 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and ESKD were excluded. Intensive BP lowering reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease by 25% and all-cause mortality by 27%. Results were similar among those with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and the 2646 adults with eGFR 20–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (P value for interaction =0.36) (Table 1) (46). A post hoc analysis of SPRINT reported that the effect of intensive BP lowering on the primary cardiovascular outcome tended to be weaker at lower eGFR when analyzed as a continuous variable (47). Although this analysis should be considered hypothesis-generating (48), it highlights the paucity of data on benefits and risks of intensive BP lowering in patients with advanced CKD.

Concerns of Intensive BP Lowering

Although SPRINT suggests that intensive BP lowering may reduce risk of cardiovascular disease and death in nondiabetic adults with CKD, there are several caveats. SPRINT reported increased risks of adverse events ranging from AKI, eGFR decline ≥30%, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and hypotension (6). Intensive BP lowering did not increase the risk of orthostatic hypotension or injurious falls. Regarding kidney outcomes, intensive BP lowering resulted in significantly increased risk of incident CKD, defined as eGFR decline ≥30% to eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in SPRINT (absolute risk difference, 2.5%; 95% CI, 1.8% to 3.2%) and to a greater degree in the ACCORD trial (absolute risk difference, 5.9%; 95% CI, 4.3% to 7.5%) (49). In SPRINT, intensive BP lowering also increased risk of eGFR decline ≥30% in the CKD subgroup (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.42 to 2.91), but had no effect on eGFR decline ≥50% or ESKD (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.36 to 2.07), although the trial was underpowered for the latter outcome (Table 1) (46). The occurrence of benefits (i.e., reduced cardiovascular disease and improved survival) concurrent with some adverse outcomes highlights the importance of shared decision-making when clinicians propose an intensive BP goal to their patients.

The clinical significance of GFR decline associated with intensive BP lowering is unclear. In a pooled analysis of the AASK and MDRD trials, the association of acute eGFR decline and mortality differed by BP goal (50). In the intensive arm, a 5%–20% acute eGFR decline was associated with lower mortality and a ≥20% eGFR decline was not associated with risk of death. By comparison, in the standard arm, a 5%–20% acute eGFR decline was not associated with risk of death and a ≥20% eGFR decline was associated with an increased risk of death. Data from SPRINT also provides some reassurance, as the majority of AKI events appear to have been mild and reversible (51). In a random sample of SPRINT participants with baseline eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, tubule injury biomarkers were measured at baseline, year 1, and year 4 (52). None of the eight biomarkers of tubule injury were higher in the intensive BP arm despite decreased eGFR, and two markers (β2-microglobulin, α1-microglobulin) were actually lower in the intensive BP arm. These findings suggest that reductions in eGFR that occur during intensive BP lowering may largely reflect hemodynamic effects rather than kidney injury.

The other major concern with intensive BP lowering in clinical practice is the issue of generalizability of trial findings. In SPRINT, several types of patients were excluded: patients with standing BP <110 mm Hg, nursing home patients, poorly compliant patients, transplant patients, and those with known secondary causes of hypertension. Indeed, the average number of medications needed during follow-up in patients with CKD was only 2.9 in the intensive group and 2.0 in the standard group, suggesting potentially better medication adherence than is typically observed. In a nationally representative Irish study, participants meeting SPRINT inclusion criteria had rates of injurious falls and syncope five-fold higher than what was observed in SPRINT (53). Another criticism of SPRINT is that unlike prior randomized trials, automated office BP was measured unattended at some clinical sites. However, site-level observer attendance appeared to have little effect on BP measurement or outcomes in SPRINT (7). Probably the bigger concern is that proper BP technique used in research efficacy trials, regardless of modality, is not often achieved in clinical practice. Further, monitoring for electrolyte disturbances and AKI may be less frequent in clinical practice compared with clinical trials (19,54). Lastly, SPRINT included few participants with stage 4–5 CKD, and data in support for intensive BP lowering in patients with CKD attributed to diabetes is limited.

Conclusions

A BP goal of <130/80 is a reasonable, evidence-based BP goal in patients with CKD, and current evidence suggests that lowering BP to <130/80 mm Hg reduces future mortality risk. In contrast, intensive BP lowering on risk of ESKD is uncertain, in part because trials have been short in duration and because acute hemodynamic effects lead to a reduction in GFR. Still, in patients with proteinuric CKD, a lower BP goal appears to reduce CKD progression. Implementation of an intensive BP goal will require increased attention to measuring BP accurately, assessing patient preferences and comorbidities, shared decision-making, and monitoring for adverse effects of therapy.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.R.C. is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K23 DK106515-01.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07440618/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Table 1. Treatment thresholds for initiating BP medications.

References

- 1.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, Alexander L, Estep K, Hassen Abate K, Akinyemiju TF, Ali R, Alvis-Guzman N, Azzopardi P, Banerjee A, Bärnighausen T, Basu A, Bekele T, Bennett DA, Biadgilign S, Catalá-López F, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fischer F, Gebru AA, Gona P, Gupta R, Hankey GJ, Jonas JB, Judd SE, Khang YH, Khosravi A, Kim YJ, Kimokoti RW, Kokubo Y, Kolte D, Lopez A, Lotufo PA, Malekzadeh R, Melaku YA, Mensah GA, Misganaw A, Mokdad AH, Moran AE, Nawaz H, Neal B, Ngalesoni FN, Ohkubo T, Pourmalek F, Rafay A, Rai RK, Rojas-Rueda D, Sampson UK, Santos IS, Sawhney M, Schutte AE, Sepanlou SG, Shifa GT, Shiue I, Tedla BA, Thrift AG, Tonelli M, Truelsen T, Tsilimparis N, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vasankari T, Venketasubramanian N, Vlassov VV, Vos T, Westerman R, Yan LL, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Zaki ME, Murray CJ: Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA 317: 165–182, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz B, Miskulin D, Zager P: Epidemiology of hypertension in CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 22: 88–95, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr., Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr., Roccella EJ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee: The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289: 2560–2572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2: 337–414, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC Jr., Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT Jr., Narva AS, Ortiz E: 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 311: 507–520, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright JT Jr., Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC Jr., Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT; SPRINT Research Group: A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 373: 2103–2116, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson KC, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Evans GW, Snyder JK, Ambrosius WT, Beddhu S, Cheung AK, Fine LJ, Lewis CE, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Rocco MV, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr.; SPRINT Research Group: Blood pressure measurement in SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial). Hypertension 71: 848–857, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotchen TA: Historical trends and milestones in hypertension research: A model of the process of translational research. Hypertension 58: 522–538, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. A cooperative study. JAMA 237: 255–261, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med 153: 154–183, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 157: 2413–2446, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group: KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck-Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Rydén L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker-Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA: 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 34: 2159–2219, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr., Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr., Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr.: 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71: 1269–1324, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I; ESC Scientific Document Group: 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 39: 3021–3104, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas G, Drawz PE: BP measurement techniques: What they mean for patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1124–1131, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth J: A short history of blood pressure measurement. Proc R Soc Med 70: 793–799, 1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, Kiss A, Tobe SW, Kaczorowski J: Measurement of blood pressure in the office: Recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension 55: 195–200, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, Kiss A, Tobe SW, Grant FC, Kaczorowski J: Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: Randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ 342: d286, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stergiou GS, Alpert B, Mieke S, Asmar R, Atkins N, Eckert S, Frick G, Friedman B, Graßl T, Ichikawa T, Ioannidis JP, Lacy P, McManus R, Murray A, Myers M, Palatini P, Parati G, Quinn D, Sarkis J, Shennan A, Usuda T, Wang J, Wu CO, O’Brien E: A Universal standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation/European Society of Hypertension/International Organization for Standardization (AAMI/ESH/ISO) collaboration statement. Hypertension 71: 368–374, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JB, Wong TC, Alpert BS, Townsend RR: Assessing the accuracy of the OMRON HEM-907XL oscillometric blood pressure measurement device in patients with nondialytic chronic kidney disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 19: 296–302, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal R: Implications of blood pressure measurement technique for implementation of Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). J Am Heart Assoc 6: e004536, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A, Tobe SW: Comparison of two automated sphygmomanometers for use in the office setting. Blood Press Monit 14: 45–47, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rinfret F, Cloutier L, Wistaff R, Birnbaum LM, Ng Cheong N, Laskine M, Roederer G, Van Nguyen P, Bertrand M, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Dufour R, Lamarre-Cliche M: Comparison of different automated office blood pressure measurement devices: Evidence of nonequivalence and clinical implications. Can J Cardiol 33: 1639–1644, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pogue V, Rahman M, Lipkowitz M, Toto R, Miller E, Faulkner M, Rostand S, Hiremath L, Sika M, Kendrick C, Hu B, Greene T, Appel L, Phillips RA; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Collaborative Research Group: Disparate estimates of hypertension control from ambulatory and clinic blood pressure measurements in hypertensive kidney disease. Hypertension 53: 20–27, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ: Prognostic importance of ambulatory blood pressure recordings in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 69: 1175–1180, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jegatheswaran J, Ruzicka M, Hiremath S, Edwards C: Are automated blood pressure monitors comparable to ambulatory blood pressure monitors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 33: 644–652, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drawz PE, Pajewski NM, Bates JT, Bello NA, Cushman WC, Dwyer JP, Fine LJ, Goff DC Jr., Haley WE, Krousel-Wood M, McWilliams A, Rifkin DE, Slinin Y, Taylor A, Townsend R, Wall B, Wright JT, Rahman M: Effect of intensive versus standard clinic-based hypertension management on ambulatory blood pressure: Results from the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) ambulatory blood pressure study. Hypertension 69: 42–50, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers MG, Oh PI, Reeves RA, Joyner CD: Prevalence of white coat effect in treated hypertensive patients in the community. Am J Hypertens 8: 591–597, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boonyasai RT, Carson KA, Marsteller JA, Dietz KB, Noronha GJ, Hsu YJ, Flynn SJ, Charleston JM, Prokopowicz GP, Miller ER 3rd, Cooper LA: A bundled quality improvement program to standardize clinical blood pressure measurement in primary care. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 20: 324–333, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, Dasgupta K, Butalia S, McBrien K, Harris KC, Nakhla M, Cloutier L, Gelfer M, Lamarre-Cliche M, Milot A, Bolli P, Tremblay G, McLean D, Padwal RS, Tran KC, Grover S, Rabkin SW, Moe GW, Howlett JG, Lindsay P, Hill MD, Sharma M, Field T, Wein TH, Shoamanesh A, Dresser GK, Hamet P, Herman RJ, Burgess E, Gryn SE, Grégoire JC, Lewanczuk R, Poirier L, Campbell TS, Feldman RD, Lavoie KL, Tsuyuki RT, Honos G, Prebtani APH, Kline G, Schiffrin EL, Don-Wauchope A, Tobe SW, Gilbert RE, Leiter LA, Jones C, Woo V, Hegele RA, Selby P, Pipe A, McFarlane PA, Oh P, Gupta M, Bacon SL, Kaczorowski J, Trudeau L, Campbell NRC, Hiremath S, Roerecke M, Arcand J, Ruzicka M, Prasad GVR, Vallée M, Edwards C, Sivapalan P, Penner SB, Fournier A, Benoit G, Feber J, Dionne J, Magee LA, Logan AG, Côté AM, Rey E, Firoz T, Kuyper LM, Gabor JY, Townsend RR, Rabi DM, Daskalopoulou SS; Hypertension Canada: Hypertension Canada’s 2018 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol 34: 506–525, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaczorowski J, Myers MG, Gelfer M, Dawes M, Mang EJ, Berg A, Grande CD, Kljujic D: How do family physicians measure blood pressure in routine clinical practice? National survey of Canadian family physicians. Can Fam Physician 63: e193–e199, 2017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malhotra R, Nguyen HA, Benavente O, Mete M, Howard BV, Mant J, Odden MC, Peralta CA, Cheung AK, Nadkarni GN, Coleman RL, Holman RR, Zanchetti A, Peters R, Beckett N, Staessen JA, Ix JH: Association between more intensive vs less intensive blood pressure lowering and risk of mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 177: 1498–1505, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright JT Jr., Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group: Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: Results from the AASK trial. JAMA 288: 2421–2431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G; Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group: The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med 330: 877–884, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr., Grimm RH Jr., Cutler JA, Simons-Morton DG, Basile JN, Corson MA, Probstfield JL, Katz L, Peterson KA, Friedewald WT, Buse JB, Bigger JT, Gerstein HC, Ismail-Beigi F; ACCORD Study Group: Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 362: 1575–1585, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, Ganeva M, Ene-Iordache B, Turturro M, Lesti M, Perticucci E, Chakarski IN, Leonardis D, Garini G, Sessa A, Basile C, Alpa M, Scanziani R, Sorba G, Zoccali C, Remuzzi G; REIN-2 Study Group: Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): Multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365: 939–946, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrier RW, Abebe KZ, Perrone RD, Torres VE, Braun WE, Steinman TI, Winklhofer FT, Brosnahan G, Czarnecki PG, Hogan MC, Miskulin DC, Rahbari-Oskoui FF, Grantham JJ, Harris PC, Flessner MF, Bae KT, Moore CG, Chapman AB; HALT-PKD Trial Investigators: Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 371: 2255–2266, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhäger WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Leonetti G, Nachev C, O’Brien ET, Rosenfeld J, Rodicio JL, Tuomilehto J, Zanchetti A: Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial investigators. Lancet 350: 757–764, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearce LA, McClure LA, Anderson DC, Jacova C, Sharma M, Hart RG, Benavente OR; SPS3 Investigators: Effects of long-term blood pressure lowering and dual antiplatelet treatment on cognitive function in patients with recent lacunar stroke: A secondary analysis from the SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 13: 1177–1185, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayashi K, Saruta T, Goto Y, Ishii M; JATOS Study Group: Impact of renal function on cardiovascular events in elderly hypertensive patients treated with efonidipine. Hypertens Res 33: 1211–1220, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson JC, Adler S, Burkart JM, Greene T, Hebert LA, Hunsicker LG, King AJ, Klahr S, Massry SG, Seifter JL: Blood pressure control, proteinuria, and the progression of renal disease. The modification of diet in renal disease study. Ann Intern Med 123: 754–762, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appel LJ, Wright JT Jr, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Astor BC, Bakris GL, Cleveland WH, Charleston J, Contreras G, Faulkner ML, Gabbai FB, Gassman JJ, Hebert LA, Jamerson KA, Kopple JD, Kusek JW, Lash JP, Lea JP, Lewis JB, Lipkowitz MS, Massry SG, Miller ER, Norris K, Phillips RA, Pogue VA, Randall OS, Rostand SG, Smogorzewski MJ, Toto RD, Wang X; AASK Collaborative Research Group: Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 363: 918–929, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ku E, Gassman J, Appel LJ, Smogorzewski M, Sarnak MJ, Glidden DV, Bakris G, Gutiérrez OM, Hebert LA, Ix JH, Lea J, Lipkowitz MS, Norris K, Ploth D, Pogue VA, Rostand SG, Siew ED, Sika M, Tisher CC, Toto R, Wright JT Jr., Wyatt C, Hsu CY: BP control and long-term risk of ESRD and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 671–677, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papademetriou V, Zaheer M, Doumas M, Lovato L, Applegate WB, Tsioufis C, Mottle A, Punthakee Z, Cushman WC; ACCORD Study Group: Cardiovascular outcomes in action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes: Impact of blood pressure level and presence of kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 43: 271–280, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung AK, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Craven TE, Greene T, Kimmel PL, Cushman WC, Hawfield AT, Johnson KC, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Rocco MV, Sink KM, Whelton PK, Wright JT Jr., Basile J, Beddhu S, Bhatt U, Chang TI, Chertow GM, Chonchol M, Freedman BI, Haley W, Ix JH, Katz LA, Killeen AA, Papademetriou V, Ricardo AC, Servilla K, Wall B, Wolfgram D, Yee J; SPRINT Research Group: Effects of intensive BP control in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2812–2823, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Obi Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Shintani A, Kovesdy CP, Hamano T: Estimated glomerular filtration rate and the risk-benefit profile of intensive blood pressure control amongst nondiabetic patients: A post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. J Intern Med 283: 314–327, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung AK, Chertow GM, Greene T, Kimmel PL, Rahman M, Reboussin D, Rocco M; SPRINT Research Group: Benefits and risks of intensive blood-pressure lowering in advanced chronic kidney disease. J Intern Med 284: 106–107, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beddhu S, Greene T, Boucher R, Cushman WC, Wei G, Stoddard G, Ix JH, Chonchol M, Kramer H, Cheung AK, Kimmel PL, Whelton PK, Chertow GM: Intensive systolic blood pressure control and incident chronic kidney disease in people with and without diabetes mellitus: Secondary analyses of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6: 555–563, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku E, Ix JH, Jamerson K, Tangri N, Lin F, Gassman J, Smogorzewski M, Sarnak MJ: Acute declines in renal function during intensive BP lowering and long-term risk of death. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2401–2408, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rocco MV, Sink KM, Lovato LC, Wolfgram DF, Wiegmann TB, Wall BM, Umanath K, Rahbari-Oskoui F, Porter AC, Pisoni R, Lewis CE, Lewis JB, Lash JP, Katz LA, Hawfield AT, Haley WE, Freedman BI, Dwyer JP, Drawz PE, Dobre M, Cheung AK, Campbell RC, Bhatt U, Beddhu S, Kimmel PL, Reboussin DM, Chertow GM; SPRINT Research Group: Effects of intensive blood pressure treatment on acute kidney injury events in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). Am J Kidney Dis 71: 352–361, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malhotra R, Craven T, Ambrosius WT, Killeen AA, Haley WE, Cheung AK, Chonchol M, Sarnak M, Parikh CR, Shlipak MG, Ix JH; SPRINT Research Group: Effects of Intensive Blood Pressure Lowering on Kidney Tubule Injury in CKD: A Longitudinal Subgroup Analysis in SPRINT. Am J Kidney Dis pii: S0272-6386(18)30879-5, 2018, doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sexton DJ, Canney M, O’Connell MDL, Moore P, Little MA, O’Seaghdha CM, Kenny RA: Injurious falls and syncope in older community-dwelling adults meeting inclusion criteria for SPRINT. JAMA Intern Med 177: 1385–1387, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang AR, Sang Y, Leddy J, Yahya T, Kirchner HL, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Coresh J, Grams ME: Antihypertensive medications and the prevalence of hyperkalemia in a large health system. Hypertension 67: 1181–1188, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trial VA: Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA 202:1028—1034, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fries E: Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA 213: 1143—1052, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. JAMA 242: 2562—2571, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helgeland A: Treatment of mild hypertension: a five year controlled drug trial. The Oslo study. Am J Med 69: 725—732, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Multiple risk factor intervention trial. Risk factor changes and mortality results. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. JAMA 248: 1465—1477, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Medical Research Council Working Party. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 291: 97—104, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA 265: 3255—3264, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Ménard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet 351: 1755—1762, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, Belhani A, Forette F, Rajkumar C, Thijs L, Banya W, Bulpitt CJ; HYVET Study Group: Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 358: 1887—1898, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.JATOS Study Group: Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res 31: 2115—2127, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel A; ADVANCE Collaborative Group, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, Harrap S, Poulter N, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee DE, Hamet P, Heller S, Liu LS, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan CY, Rodgers A, Williams B: Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370: 829—840, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.SPS3 Study Group, Benavente OR, Coffey CS, Conwit R, Hart RG, McClure LA, Pearce LA, Pergola PE, Szychowski JM: Blood-pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: the SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet 382: 507—515, 2013, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60852-1. Published ahead of print May 29, 2013. Erratum in: Lancet 382: 506, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.The 1980 report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med 140: 1280—1285, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The 1984 Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med 144: 1045—1057, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.The 1988 report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med 148: 1023—1038, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heerspink HJ, Ninomiya T, Perkovic V, Woodward M, Zoungas S, Cass A, Cooper M, Grobbee DE, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Neal B, Chalmers J; ADVANCE Collaborative Group: Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Eur Heart J 31: 2888—2896, 2010, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq139. Published ahead of print May 25, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schrier RW, Abebe KZ, Perrone RD, Torres VE, Braun WE, Steinman TI, Winklhofer FT, Brosnahan G, Czarnecki PG, Hogan MC, Miskulin DC, Rahbari-Oskoui FF, Grantham JJ, Harris PC, Flessner MF, Bae KT, Moore CG, Chapman AB; HALT-PKD Trial Investigators: Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2014 371: 2255—2266, 2014, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402685. Published ahead of print November 15, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.