Abstract

Background

Calciphylaxis is a life-threatening complication of chronic kidney disease (CKD). To inform clinical practice, we performed a systematic review of case reports, case series, and cohort studies to synthesize the available treatment modalities and outcomes of calciphylaxis in patients with CKD.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched for studies that examined the uses of sodium thiosulfate, surgical parathyroidectomy, calcimimetics, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and bisphosphonates for calciphylaxis in patients with CKD, including end-stage renal disease. For cohort studies, the results were synthesized quantitatively by performing random-effects model meta-analyses.

Results

A total of 147 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. There were 90 case reports (90 patients), 20 case series (423 patients), and 37 cohort studies (343 patients). In the pooled cohorts, case series, and case reports, 50.3% of patients received sodium thiosulfate, 28.7% underwent surgical parathyroidectomy, 25.3% received cinacalcet, 15.3% underwent hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and 5.9% received bisphosphonates. For the subset of cohort studies, by meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio for mortality was not significantly different among patients who received sodium thiosulfate (pooled risk ratio [RR] 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.71–1.12), cinacalcet (pooled RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.75–1.42), hyperbaric oxygen therapy (pooled RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.71–1.12), and bisphosphonates (pooled RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.44–1.32), and those who underwent surgical parathyroidectomy (pooled RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.69–1.13).

Conclusion

This systematic review found no significant clinical benefit of the 5 most frequently used treatment modalities for calciphylaxis in patients with CKD. Randomized controlled trials are needed to test the efficacy of these therapies.

Keywords: calciphylaxis, chronic kidney disease, meta-analysis, systematic review

Calcific uremic arteriolopathy or calciphylaxis is a rare and serious disorder that presents with skin ischemia and necrosis and is characterized histologically by calcification of arterioles in dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissue.1 Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on dialysis, and confers a high mortality rate of 40% to 60%.2 The incidence of calciphylaxis in hemodialysis patients has been estimated at 35 cases per 10,000 patients in the United States3 and 4 cases per 10,000 patients in Europe.4 Major risk factors include poorly controlled secondary hyperparathyroidism, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and warfarin therapy.3, 5 Although the pathophysiology of calciphylaxis has primarily been linked to longstanding hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism,6 low parathyroid hormone levels confer an increased risk for calciphylaxis.4

To date, there are no evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of calciphylaxis, only expert opinions derived from the limited literature.4, 7 Treatment modalities are not standardized, but they all focus on wound care with or without surgical debridement. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is proposed to be the second line of wound care treatment8 to improve oxygen delivery to hypoxic soft tissues and promote wound healing. Calcium-based phosphate binders and vitamin D analogues should be avoided, and patients with poorly controlled hyperparathyroidism should be prescribed a calcimimetic agent or undergo surgical parathyroidectomy. Sodium thiosulfate is frequently used an adjunctive treatment, with several proposed mechanisms, including calcium chelation, vasodilatory effects, and ability to restore endothelial function.9 Although bisphosphonates have been used for the treatment of calciphylaxis, their mechanism of action is unknown, and includes inhibition of calcium crystallization and prevention of hydroxyapatite formation.10, 11 Other treatments described in case reports have included the use of apheresis12 and tissue plasminogen activator.13, 14 At present, there are no approved treatments for calciphylaxis, and all drug therapies that have been tested fall under the off-label use.

To inform clinical practice and shed more light on this orphan serious and fatal disorder, we performed a systematic review of case reports, case series, and cohort studies to synthesize the available treatment strategies and outcomes of patients presenting with calciphylaxis.

Methods

Data Source and Searches

The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.15 The literature search was conducted in MEDLINE (1966 to July 2018), Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials to identify eligible studies. For the search, the following Medical Subject Heading terms were used: “calciphylaxis” and “calcific uremic arteriolopathy.” We also manually reviewed the reference list in the retrieved articles. The search was limited to the English language and focused on adults (age ≥18 years) with all stages of CKD, including end-stage renal disease.

Study Selection

In the absence of randomized controlled trials for the treatment of calciphylaxis, we focused on retrospective and prospective cohort studies, case series, and case reports that reported on 1 or more of the following treatment modalities for calciphylaxis: sodium thiosulfate, surgical parathyroidectomy, calcimimetic agent (i.e., cinacalcet), hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and bisphosphonates. There were no restrictions on sample size or study duration.

We classified types of studies based on the presence or absence of a control group. Case reports or single cases consisted of reports of individual patients who received at least 1 of the previously mentioned treatment modalities. Case series consisted of multiple cases (>1 subject) in which patients received the same treatment modalities, and there was no control group.16 Cohort studies entailed patients receiving treatment and a control group not receiving treatment.17 For both case series and cohort studies that had multiple treatment modalities, we meta-analyzed each treatment modality separately according to the presence or absence of a control group.

The CAse REport (CARE) guidelines18 and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement19 were used to identify case reports and cohort studies, respectively. Only case reports with adequate information according to the CARE guidelines, and cohort studies with adequate methods according to the STROBE statement were included in the review. Two authors (SU and KK) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the electronic citations, and full-text articles were retrieved for comprehensive review, and were independently rescreened. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and arbitration by a third author (PS).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following study characteristics were extracted in duplicate: country of origin, year of publication, study design, number of patients, demographic data, dialysis modality, diabetes mellitus status, medication use (vitamin D analogues, calcium-based phosphate binders, and warfarin), laboratory test results (calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone level) at the time of diagnosis, and location of the calciphylaxis skin lesions (upper vs. lower extremities, proximal vs. distal).

The following outcomes of interest were extracted: characteristics of each treatment modality, impact on calciphylaxis skin lesions, all-cause mortality, and treatment-related adverse effects. The outcome of the calciphylaxis skin lesions were categorized into 3 groups: complete resolution of lesions, partial resolution or stable lesions, and worsening of lesions.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The results of the case reports and case series were tabulated and synthesized qualitatively. The results of the case series were synthesized quantitatively by performing random-effects model meta-analyses to compute pooled means and rates with corresponding 95% CIs to describe patient characteristics and clinical outcomes. For the subset of cohort studies with analyzable and comparable data, the results were synthesized quantitatively by performing random-effects model meta-analyses to compute weighted mean difference for continuous variables, and pooled risk ratios (RRs) for binary variables. All pooled estimates are displayed with a 95% CI. Existence of heterogeneity among study effect sizes was examined using the I2 index and the Q-test P value. An I2 index greater than 75% indicate medium to high heterogeneity.

Categorical variables were presented as percentage and continuous variables as mean ± SD or median (with interquartile range). Statistical significance was met when P value was less than 0.05. Publication bias was formally assessed using funnel plots and the Egger test. The analyses were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software version 2.0 (www.meta-analysis.com; Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

Results

Characteristics of the Studies

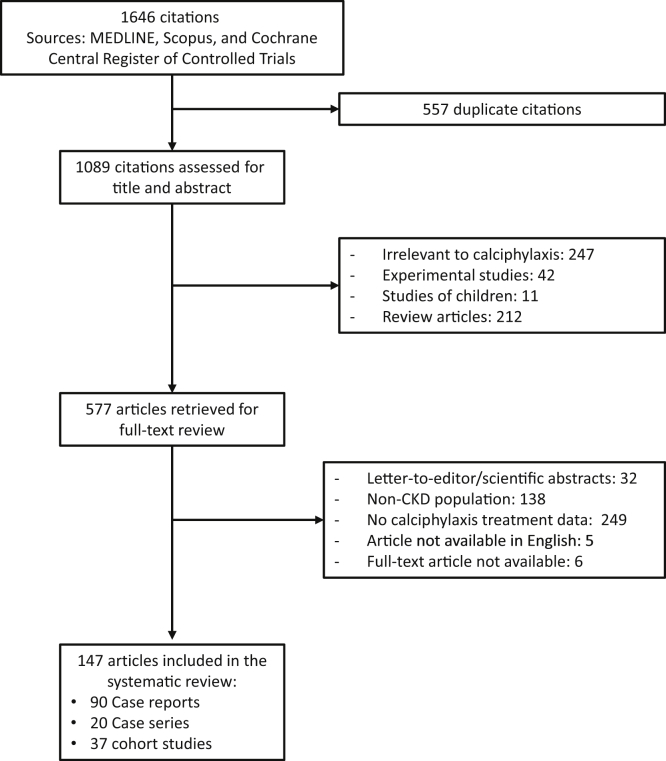

A total of 1646 potentially relevant citations were identified and screened; 577 articles were retrieved for detailed evaluation, of which 147 fulfilled eligibility criteria, including 37 cohort studies,10, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 20 case series,8, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 and 90 case reports75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164 (Figure 1). There were 856 patients, 90 originating from case reports, 423 originating from case series, and 343 originating from cohort studies. Details of the individual reports are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 to S3.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Characteristics of Patients With Calciphylaxis and Risk factors

Table 1 displays the characteristics of patients (derived from case reports, case series, and cohort studies) at the time of diagnosis of calciphylaxis and notable risk factors for the disorder. In brief, 70% were women, with a mean age of 56 ± 13 years, and a mean body mass index of 29.7 ± 8.8 kg/m2. Seventy-six percent of patients were on long-term hemodialysis for a mean of 4.3 ± 4.6 years. Diabetes mellitus was prevalent in 49% of patients. Forty-six percent of patients received calcium-containing phosphate binders, 54% received vitamin D analogues, and 41% received warfarin. Mean serum phosphorus was 6.1 ± 1.9 mg/dl. Distal lower extremities were the most common skin lesion sites (55.3%), followed by proximal lower extremities (39.3%), trunk (31.0%), distal upper extremities (7.2%), and proximal upper extremities (3.4%).

Table 1.

Summary measures of clinical characteristics, risk factors, treatment modalities, and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis (derived from case reports, case series and cohort studies)

| Variables | Total population (n = 856) | Number of reported patients |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||

| Age, yr | 56.3 ± 13.3 | 856 |

| Male gender, % | 29.7 | 829 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 8.8 | 239 |

| Hemodialysis, % | 75.9 | 801 |

| Peritoneal dialysis, % | 10.4 | 801 |

| Chronic kidney disease not on dialysis, % | 15.7 | 692 |

| Dialysis vintage,a yr | 4.3 ± 4.6i | 414 |

| Risk factors for calciphylaxis and laboratory data | ||

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 49.4 | 813 |

| Calcium-containing phosphate binders, % | 45.8 | 334 |

| Warfarin use, % | 40.8 | 472 |

| Vitamin D analogues, % | 53.7 | 334 |

| Serum calcium,b mg/dl | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 675 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 675 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 427 |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 584 ± 933i | 671 |

| Location of calciphylaxis skin lesions | ||

| Proximal upper extremities,c % | 3.4 | 442 |

| Distal upper extremities,d % | 7.2 | 442 |

| Proximal lower extremities,e % | 39.3 | 436 |

| Distal lower extremities,f % | 55.3 | 436 |

| Trunk,g % | 31.0 | 442 |

| Treatment modalities | ||

| Use of sodium thiosulfate,% | 50.3 | 856 |

| Cumulative dose, g | 1115 ± 1866i | 265 |

| Treatment duration, week | 19.8 ± 25.9i | 98 |

| Use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, % | 15.3 | 856 |

| Treatment dose, atmosphere | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 27 |

| Number of sessions | 40.8 ± 24.1 | 53 |

| Surgical parathyroidectomy,h % | 28.7 | 856 |

| Use of cinacalcet, % | 25.3 | 739 |

| Daily dose, mg/d | 51.6 ± 31.3 | 19 |

| Treatment duration, week | 27.4 ± 20.2i | 9 |

| Use of bisphosphonates, % | 5.9 | 623 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||

| Amputations, % | 10.2 | 432 |

| Complete resolution of lesions, % | 39.0 | 615 |

| Partial resolution or stable lesions, % | 31.1 | 615 |

| Worsening of lesions, % | 26.1 | 615 |

| Mortality, % | 46.9 | 853 |

Continuous data shown as mean ± SD.

Dialysis vintage was calculated for the dialysis population.

Serum calcium was corrected for the serum albumin.

Upper extremities, proximal type: lesion located from shoulder to elbow.

Upper extremities, distal type: lesion located from elbow to finger.

Lower extremities, proximal type: lesion located from hip to knee.

Lower extremities, distal type: lesion located from knee to toe.

Trunk: lesion located in chest, abdomen, or buttock.

Parathyroidectomy; total, subtotal, or near total parathyroidectomy.

Median (with interquartile range) value for selected parameters: dialysis vintage 4.7 years (2.0–7.6), parathyroid hormone level 646 pg/ml (230–922), cumulative dose of sodium thiosulfate 600 g (240–1350), sodium thiosulfate treatment duration 12 weeks (8–24), and cinacalcet treatment duration 28 weeks (12–52).

Treatment Modalities and Clinical Outcomes

Sodium thiosulfate was the most commonly prescribed treatment (50.3%) to patients with calciphylaxis (Table 1), with a mean treatment duration of 20 ± 26 weeks (median 12 weeks, interquartile range 8–24 weeks) and a cumulative dose of 1302 ± 2745 g (median 600 g, interquartile range 240–1350 g). Twenty-five percent of patients were treated with cinacalcet at a mean daily dose of 52 ± 31 mg for a mean duration of 27 ± 20 weeks (median 28 weeks, interquartile range 12–52 weeks). Twenty-nine percent underwent surgical parathyroidectomy. Fifteen percent of patients received hyperbaric oxygen therapy for a mean of 41 ± 24 sessions. Approximately one-third of patients had worsening of the skin lesions. The overall mortality rate was 46.9%.

The location of the calciphylaxis skin lesions dictated clinical outcomes (Supplementary Table S4). Lesions located in the proximal upper extremities (shoulder to elbow) were associated with the worst outcomes (50.0% had worsening skin lesions with a mortality rate of 70.0%), followed by truncal lesions (50.0% with worsening lesions and a mortality rate of 63.8%). Lesions located in the distal lower extremities (knee to foot) had the lowest likelihood of worsening calciphylaxis (33.5%), and lesions located in the distal upper extremities (elbow to hand) had the lowest observed mortality rate (46.9%).

Meta-analysis of Case Series

Table 2 displays the results of the meta-analysis of the case series. Patients who underwent surgical parathyroidectomy or received a calcimimetic had a high serum parathyroid hormone level with a weighted mean value of 640 pg/ml (95% CI 393–887) and 1000 pg/ml (95% CI 683–1316), respectively. Patients who received hyperbaric oxygen therapy had lower serum parathyroid hormone levels with a weighted mean of 202 pg/ml (95% CI 55–350) and had been on dialysis for a weighted mean of 8.4 years (95% CI 1.5–18.3). Patients prescribed sodium thiosulfate and bisphosphonates had a serum parathyroid hormone level that was within the clinical practice guideline goals with a weighted mean value of 431 pg/ml (95% CI 329–534) and 459 pg/ml (95% CI 98–1016), respectively.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis according to treatment modality (derived from case series)

| Variables | Sodium thiosulfate |

Surgical Parathyroidectomy |

Cinacalcet |

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy |

Bisphosphonates |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean (95% CI) | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean (95% CI) | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean (95% CI) | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean (95% CI) | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean (95% CI) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Age, yr | 14 | 321 | 58.5 (44.0–73.0) | 11 | 54 | 53.3 (48.1–58.4) | 3 | 12 | 53.3 (36.3–70.2) | 5 | 61 | 57.7 (54.0–61.4) | 1 | 3 | 58.5 (44.0–73.0) |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 8 | 228 | 2.9 (2.1–3.7) | 7 | 33 | 7.3 (5.1–9.4) | 2 | 10 | 3.5 (1.6–5.5) | 3 | 18 | 8.4 (1.5–18.3) | – | – | – |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 9 | 303 | 9.2 (8.8–9.7) | 10 | 51 | 9.5 (9.0,10.0) | 3 | 12 | 8.8 (6.5,11.1) | 5 | 61 | 9.4 (8.7–10.0) | 1 | 3 | 9.0 (7.9–10.3) |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 9 | 303 | 5.7 (5.4–6.1) | 10 | 51 | 5.7 (5.4–6.1) | 3 | 12 | 5.3 (4.7–5.9) | 5 | 61 | 6.6 (5.4–7.8) | 1 | 3 | 6.3 (3.9–8.7) |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 4 | 269 | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 2 | 12 | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 1 | 2 | 3.5 (3.5–3.5) | 2 | 14 | 2.8 (2.2–3.3) | 1 | 3 | 3.1 (2.2–4.0) |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 10 | 305 | 431.3 (329.0–533.5) | 8 | 38 | 640.1 (393.3–886.8) | 3 | 12 | 999.6 (683.4–1315.7) | 4 | 50 | 202.4 (55.1–349.8) | 1 | 3 | 459.0 (97.7–1015.7) |

| Clinical outcomes | |||||||||||||||

| Amputation, % | 12 | 85 | 11.9 (6.5–20.9) | 10 | 44 | 41.1(24.3–60.2) | 3 | 12 | 10.4 (2.1–38.8) | 4 | 52 | 9.3 (3.0–25.6) | – | – | – |

| Worsening of lesions, % | 14 | 321 | 30.4 (24.3–37.3) | 11 | 54 | 43.7 (24.4–65.1) | 3 | 12 | 30.4 (4.9–78.9) | 4 | 52 | 37.3 (25.3–51.2) | 1 | 3 | 66.7 (15.4–95.7) |

| Mortality, % | 14 | 321 | 44.4 (31.1–58.6) | 10 | 44 | 44.9 (29.2–61.7) | 3 | 12 | 62.8(8.2–97.0) | 4 | 52 | 43.8 (11.3–82.6) | – | – | – |

In terms of clinical outcomes, patients who underwent surgical parathyroidectomy had the highest amputation rate, with a weighted mean of 41.1% (95% CI 24.3–60.2). The mortality rate was lowest in patients undergoing hyperbaric oxygen therapy with a weighted mean of 43.8% (95% CI 11.3–82.6).

Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies

In the 7 cohort studies on the use of sodium thiosulfate (151 patients), the pooled risk ratio for mortality was not different between patients who received sodium thiosulfate relative to those who did not (pooled RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.71–1.12, P = 0.31; Table 3). In the 20 cohort studies that examined the use of surgical parathyroidectomy (171 patients), the pooled RR for mortality was not significantly lower between patients who underwent parathyroidectomy relative to those who did not (pooled RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.69–1.13; P = 0.31; Table 4). Patients undergoing surgical parathyroidectomy were younger compared to those who did not (mean age difference −5.44 years; 95% CI −10.55 to −0.34, P = 0.04; Table 4). Serum albumin and parathyroid hormone levels were higher in patients who underwent surgical parathyroidectomy (mean difference 0.36 g/dl, 95% CI 0.03–0.70, P = 0.04 for serum albumin, and mean difference 148.01 pg/ml, 95% CI 2.74–293.29, P = 0.05 for parathyroid hormone level; Table 4). Patients undergoing parathyroidectomy had a lower risk of wound deterioration (pooled RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.99, P = 0.05; Table 4), compared to those who did not. In the 9 cohort studies (73 patients) that examined the use of cinacalcet, the drug had no impact on mortality (pooled RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.75–1.42, P = 0.83; Table 5). In the 10 cohort studies that examined the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (170 patients), there was no impact on mortality (pooled RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.71–1.12, P = 0.32; Table 6). Finally, in the 6 cohort studies (56 patients) that examined the use of bisphosphonates, including pamidronate, ibandronate, etidronate, alendronate, and risedronate, their use did not lower mortality compared to untreated patients (pooled RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.44–1.32, P = 0.34; Table 7).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis treated with sodium thiosulfate relative to those who did not (derived from cohort studies)

| Sodium thiosulfate | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | P | I2 index, % | Q-test P value | Egger’s test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 4 | 129 | −0.16 (−5.43 to 5.11) | 0.95 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.77 |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 3 | 28 | −0.52 (−1.76 to 0.72) | 0.16 | 0 | 0.77 | 0.58 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 3 | 28 | −0.01 (−0.89 to 0.87) | 0.98 | 0 | 0.99 | 0.09 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 3 | 28 | 0.29 (−0.79 to 1.37) | 0.60 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3 | 28 | 0.27 (−0.29 to 0.83) | 0.35 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.22 |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 3 | 28 | −1.47 (−35.44 to 32.51) | 0.93 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.52 |

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||||||

| Amputation | 7 | 52 | 0.93 (0.29–2.97) | 0.90 | 0 | 0.85 | 0.97 |

| Worsening of lesions | 4 | 28 | 0.66 (0.23–1.93) | 0.45 | 39.9 | 0.17 | 0.69 |

| Mortality | 7 | 151 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.31 | 0 | 0.83 | 0.51 |

| Mortalitya | 7 | 151 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.31 | 0 | 0.83 | 0.51 |

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies published in 2006 and thereafter (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported).

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis who underwent surgical parathyroidectomy relative to those who did not (derived from cohort studies)

| Parathyroidectomy | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | P | I2 index, % | Q-test P value | Egger’s test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 15 | 137 | −5.44 (−10.55 to −0.34) | 0.04 | 64.0 | <0.001 | 0.87 |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 9 | 66 | 0.74 (−0.88 to 2.36) | 0.37 | 52.6 | 0.03 | 0.79 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 12 | 112 | −0.14 (−0.66 to 0.37) | 0.58 | 30.7 | 0.15 | 0.89 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 12 | 112 | 0.35 (−0.14 to 0.85) | 0.16 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.42 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 6 | 51 | 0.36 (0.03 to 0.70) | 0.04 | 0 | 0.57 | 0.04 |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 13 | 123 | 148.01 (2.74 to 293.29) | 0.05 | 75.5 | <0.001 | 0.95 |

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||||||

| Amputation | 7 | 49 | 1.35 (0.49–3.70) | 0.56 | 0 | 0.91 | 0.48 |

| Worsening of skin lesions | 17 | 143 | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) | 0.05 | 0 | 0.93 | 0.33 |

| Mortality | 20 | 171 | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | 0.31 | 3.0 | 0.42 | 0.82 |

| Mortalitya | 10 | 84 | 1.05 (0.72–1.54) | 0.80 | 14.1 | 0.31 | 0.47 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance.

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies published in 2006 and thereafter (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported).

Table 5.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis treated with cinacalcet relative to those who did not (derived from cohort studies)

| Cinacalcet | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | P | I2 index, % | Q-test P value | Egger’s test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 8 | 73 | −2.02 (−8.63 to 4.60) | 0.55 | 0 | 0.88 | 0.43 |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 6 | 53 | 0.33 (−0.53 to 1.19) | 0.46 | 2.1 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 7 | 67 | −0.001 (−0.41 to 0.40) | 0.99 | 0 | 0.99 | 0.31 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 7 | 67 | 0.47 (−0.52 to 1.46) | 0.35 | 39.5 | 0.13 | 0.94 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 5 | 46 | 0.02 (−0.64 to 0.68) | 0.96 | 63.34 | 0.03 | 0.64 |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 7 | 67 | 313.53 (−32.40 to 659.45) | 0.08 | 90.54 | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||||||

| Amputation | 3 | 21 | 1.18 (0.23–6.03) | 0.85 | 0 | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| Worsening of skin lesions | 5 | 44 | 0.86 (0.32–2.28) | 0.76 | 0 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| Mortality | 9 | 73 | 1.04 (0.75–1.42) | 0.83 | 0 | 0.51 | 0.96 |

| Mortalitya | 9 | 73 | 1.04 (0.75–1.42) | 0.83 | 0 | 0.51 | 0.96 |

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies published in 2006 and thereafter (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported).

Table 6.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis who received hyperbaric oxygen therapy relative to those who did not (derived from cohort studies)

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | P | I2 index, % | Q-test P value | Egger’s test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 7 | 163 | 1.69 (−3.17 to 6.56) | 0.50 | 0 | 0.97 | 0.24 |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 4 | 40 | 0.33 (−1.05 to 1.71) | 0.64 | 0 | 0.85 | 0.30 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 6 | 62 | 0.24 (−0.33 to 0.81) | 0.41 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.64 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 6 | 62 | 0.93 (0.52 to 1.34) | <0.001 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.02 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 5 | 48 | 0.29 (−0.19 to 0.76) | 0.24 | 15.6 | 0.32 | 0.06 |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 6 | 62 | 144.90 (−83.28 to 373.09) | 0.21 | 48.9 | 0.08 | 0.92 |

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||||||

| Amputation | 3 | 21 | 2.02 (0.40–10.31) | 0.40 | 0 | 0.71 | 0.06 |

| Worsening of skin lesions | 6 | 47 | 0.87 (0.48–1.60) | 0.66 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| Mortality | 10 | 170 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.32 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.67 |

| Mortalitya | 10 | 170 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.32 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.67 |

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies published in 2006 and thereafter (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported).

Table 7.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis who received bisphosphonates therapy relative to those who did not (derived from cohort studies)

| Bisphosphonates therapy | No. of studies | No. of patients | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | P | I2 index, % | Q-test P value | Egger’s test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 3 | 43 | −1.72 (−8.90 to 5.45) | 0.64 | 0 | 0.37 | 0.96 |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 2 | 37 | 0.25 (−0.30 to 0.79) | 0.38 | 0 | 0.37 | NA |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 2 | 37 | 0.17 (−1.12 to 1.46) | 0.79 | 0 | 0.92 | NA |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Serum intact parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 2 | 37 | −57.73 (−201.47 to 86.01) | 0.43 | 0 | 0.96 | NA |

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||||||

| Amputation | 1 | 23 | 0.06 (0.01–0.99) | 0.05 | 0 | 1.00 | NA |

| Worsening of skin lesions | 5 | 51 | 0.50 (0.13–1.86) | 0.30 | 26.6 | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| Mortality | 6 | 56 | 0.77 (0.44–1.32) | 0.34 | 0 | 0.54 | 0.67 |

| Mortalitya | 5 | 54 | 0.80 (0.46–1.39) | 0.43 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.73 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance. NA, not available.

Subgroup analysis of cohort studies published in 2006 and thereafter (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported).

Secondary analyses focusing on studies published in 2006 (the year that the use of cinacalcet for the treatment of calciphylaxis was first reported) and thereafter did not show a mortality benefit across all treatment modalities. Similarly, by meta-regression of the mortality rate against year of publication, there was no significant mortality rate change over time for any of the treatment modalities, including sodium thiosulfate (rate change = −0.11%; 95% CI −0.31 to 0.09, P = 0.28), surgical parathyroidectomy (rate change = 0.01%; 95% CI −0.01 to 0.04; P = 0.76), cinacalcet (rate change = −0.06%; 95% CI −0.22 to 0.10, P = 0.61), hyperbaric oxygen therapy (rate change −0.06%; 95%CI −0.17 to 0.06, P = 0.32), and bisphosphonates (rate change −0.07%; 95% CI −0.34 to 0.20, P = 0.61).

Analyses of Treatment-Related Adverse Effects

Sodium thiosulfate resulted in a high anion gap metabolic acidosis in 19 (32.3%) of the 59 patients with available data. Hypernatremia occurred in 3 (18.8%) of 16 reported patients. Fifty-seven (24.7%) of 231 patients experienced nausea and vomiting. Among the 2288 sessions of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, the incidence rate of barotrauma was 0.2%, anxiety 0.2%, myopia 0.1%, and nausea and vomiting 0.1%. There were no treatment-related adverse effects reported for cinacalcet, bisphosphonates, and surgical parathyroidectomy.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis explores the benefits of 5 treatment modalities for calcific uremic arteriolopathy or calciphylaxis in patients with CKD, including end-stage renal disease. We focused on 2 clinical outcomes: wound healing and mortality. At time of diagnosis, most patients were on maintenance hemodialysis, with a preponderance of women and a mean age of 56 years. The significant laboratory abnormalities were hyperphosphatemia with a mean intact parathyroid hormone level at the upper limit of the recommendation by clinical practice guidelines.165 Skin lesions located in the proximal upper extremity were associated with the highest mortality rate. Compared with cohort studies, wound healing and survival rates tended to be higher in uncontrolled studies (i.e., in case reports and case series) (Supplementary Table S5), reflecting in part publication bias. However, the mortality RR did not meet statistical significance in meta-analyses that included only studies with control groups (i.e., cohort studies).

Calciphylaxis was first described in 1961 by Selye and colleagues.166 At first, it was demonstrated in rats with kidney failure as a hypersensitivity reaction to sensitizing agents. With more cases and knowledge in pathogenesis, it is now defined as a systemic process of vascular calcification, particularly in small dermal and subcutaneous arteries and arterioles, leading to microthrombi and tissue ischemia.167 Patients commonly present with severe intractable pain in the involved skin areas. In more severe cases, tissue ischemia progresses to chronic ulcerated dry gangrene.29, 106, 168 These lesions are frequently infected and lead to septicemia and the patient’s death. In addition to skin involvement, calciphylaxis can involve internal organs, such as intestines, brain, and liver, leading to organ dysfunction.80, 169, 170, 171, 172 The pathogenic mechanisms of vascular calcification are not fully elucidated. The imbalance between promotors and inhibitors of vascular calcification is the most accepted hypothesis. Phosphate and calcium abnormal metabolism, uremic toxins, hypercoagulability, and endothelial dysfunction can trigger the transformation of smooth muscle cells into osteoblast-like cells6 and initiate the process of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. This theory, however, faces some scrutiny among patients with calciphylaxis in the absence of uremia or abnormal mineral metabolism.173 In the present study, we found that 46% and 54% of patients received calcium-containing phosphate binders and vitamin D analogues, respectively. These percentages are higher than in the general dialysis population where 34% to 38% of patients are taking a calcium-containing phosphate binder and 24% are taking a vitamin D analogue174, 175 and support the premise that calcium-phosphate-parathyroid hormone dysregulated metabolism has a role in the development of calciphylaxis.3 Approximately 41% of patients in our systematic review were taking warfarin at the time of diagnosis of the calciphylaxis. This high prevalence rate of vitamin K antagonist use supports its role as a promotor of vascular calcification, potentially through the inhibition of vitamin K-dependent Matrix Gla-protein, a potent inhibitor of arterial calcification.176 In addition, most of the patients in our review were overweight, were women, and had diabetes mellitus, which are also known risk factors for calciphylaxis.5

The rationale for using sodium thiosulfate for the treatment of calciphylaxis is based on the proposed pathogenesis of the disease.9, 177 Thiosulfate forms highly soluble complexes with calcium and decreases calcium-phosphate precipitation in the vascular wall. Other mechanisms include an antioxidant and vasodilatory effect, resulting in decreased tissue ischemia and pain relief. Sodium thiosulfate is typically prescribed i.v. at a dose of 25 g thrice weekly after hemodialysis. In our systematic review, the mean sodium thiosulfate treatment duration was 20 weeks with a cumulative dose of 1155 g, the equivalent of 45 doses. We estimated an average weekly dose of 56 g. In our analysis, there was no demonstrable benefit of sodium thiosulfate on wound healing and mortality, which is consistent with a recently published systematic review of case reports and case series.178 The common side effects reported in our data synthesis included nausea and vomiting, high anion gap metabolic acidosis, and hypernatremia, consistent with previous reports.177 Although sodium thiosulfate is a promising treatment for calciphylaxis, the optimal dose and treatment duration need to be formally examined in a randomized controlled trial.

By restoring the abnormal calcium-phosphate-parathyroid hormone metabolism, surgical parathyroidectomy is believed to improve calciphylaxis-related outcomes. This is based on previous cohorts and case reports.23, 32, 33, 63 However, more recent studies179, 180 suggest that surgical parathyroidectomy might not be suitable for every patient with calciphylaxis, especially those who are at risk for postoperative complications. Moreover, recurrent or de novo calciphylaxis has been described following surgical parathyroidectomy.65, 181, 182 Our results show that patients who underwent parathyroidectomy had higher serum parathyroid hormone levels and tended to be younger and healthier with higher serum albumin levels (Table 4). These differences in patient characteristics might have led to better wound healing. At present, surgical parathyroidectomy should be reserved for patients with poorly controlled hyperparathyroidism unresponsive to calcimimetics,183 and with careful preoperative evaluation.

Medical parathyroidectomy can be achieved through the use of cinacalcet, an oral calcimimetic.184 The results derived from our systematic review of case reports and case series show that patients treated with an oral calcimimetic had a lower rate of worsening skin lesions and lower mortality rate compared to those who were not. However, the results derived from our meta-analysis of cohort studies did not demonstrate a mortality benefit. Although cinacalcet has been shown to reduce the incidence of calciphylaxis in hemodialysis patients according to a post hoc analysis from the largest randomized controlled trial of cinacalcet,185 this was not observed in a large case-control study of hemodialysis patients.3

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is an adjunctive consideration for wound care in patients with calciphylaxis. It increases the amount of dissolved oxygen and its delivery to the local tissue. The exact mechanism of wound healing promoted by hyperbaric oxygen therapy is unclear, but the hypotheses include enhancing fibroblast function and angiogenesis, increasing neutrophil bactericidal activity, and direct toxicity of high oxygen tension to anaerobic microorganisms.6 Patients are required to breathe in the hyperbaric chamber with 100% oxygen, usually at 2.5 atmospheres absolute. In our synthesis of the data, patients received a mean of 35.8 sessions of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The most common adverse effect is middle ear barotrauma,186 which can be prevented by pretreatment maneuvers.187, 188 Claustrophobia is another psychological barrier to hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which can be solved by using a multiplace chamber. Our results did not demonstrate efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for treatment of calciphylaxis in the pooled cohort studies.

Bisphosphonates are the most frequently used medications for the treatment of osteoporosis.189 Similar to sodium thiosulfate and cinacalcet, the off-label use of bisphosphonates has been reported to effectively treat calciphylaxis.105, 115, 190 Proposed mechanisms of action include inhibition of hydroxyapatite crystallization, reduction of macrophage activity, and a decrease of proinflammatory cytokines.189 Overall, bisphosphonates might reduce the capacity of calcium to accumulate in the arterial wall, thus inhibit vascular calcification.10 In our systematic review, the use of bisphosphonates was reported in 37 patients. This number is too small to evaluate their true efficacy and potential harm, especially in the setting of decreased glomerular filtration rate, and their role requires careful study.

In clinical practice, treatment of calciphylaxis is multifaceted and multidisciplinary.5 Data from a large nationwide registry in Germany4 show that common therapeutic strategies for calciphylaxis include surgical wound management (29.2%), discontinuation of vitamin K antagonist (25.4%), discontinuation or reduction of calcium-containing phosphate binders (23.8%), administration of sodium thiosulfate (21.5%), administration of vitamin K (17.7%), intensifying dialysis treatment (16.9%), and reduction or discontinuation of vitamin D analogues (16.2%). However, these treatment patterns are largely based on expert opinions without sufficient high-level clinical evidence. Based on a recent survey conducted at the International Consensus Conference on Calciphylaxis, the opinions on diagnosis and management of calciphylaxis were very diverse.191 Some strategies, such as surgical wound management and intensifying dialysis treatment, had very high heterogeneity in details.

In our systematic review, we selected 5 frequently used interventions to help inform clinical practice. We found no randomized controlled trials, which limit the robustness of our findings. National registries on calciphylaxis are being established to help collect high-quality data and inform clinical practice in terms of natural history of disease and treatment trends and measures of efficacy.3, 4, 192, 193 Ongoing clinical trials identified at the ClinicalTrials.gov Web site (accessed on September 19, 2018), a database of funded clinical studies, for the treatment of calciphylaxis are summarized in Supplementary Table S6.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. We focused on the most frequently used treatment modalities and described their pattern of use, but found no clear clinical benefit of any specific therapy. In addition, variable patient characteristics likely resulted in patient selection bias regarding the pursuit of surgical versus medical treatment. Patients who received surgical interventions were more likely to be deemed fit to undergo surgery. However, due to the lack of randomized controlled trials, our analysis is descriptive and our results are inconclusive. Moreover, the reports frequently described multimodal treatment approaches and protocols, rendering the assessment of the efficacy of each modality impossible to ascertain.

In conclusion, in the present systematic review, although sodium thiosulfate, surgical parathyroidectomy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, cinacalcet, and bisphosphonates failed to demonstrate a mortality benefit in the pooled cohort studies, the results are inconclusive, as they are not derived from randomized controlled trials, and their potential benefit cannot be ruled out. Multicenter randomized controlled trials are urgently needed to demonstrate the true efficacy of these treatment modalities, individually or combined, for this vexing and life-shortening orphan disease.

Disclosure

This study was funded by a grant from the Thailand Research Fund (#RSA5880067) and the Metabolic Bone Disease in CKD Patients Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Medical Library, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. The librarians provided support in obtaining the original articles for the purpose of the systematic review.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

SU: first author, study design, review of citations and articles, analysis, manuscript preparation; KK: review of citations and articles; KP: study design; SE-O: manuscript review and edits; BLJ: manuscript review and edits; PS: corresponding author, review of citations and articles, analysis, manuscript review and edits.

Footnotes

Table S1. Cohort studies included in the systematic review.

Table S2. Case series included in the systematic review.

Table S3. Case reports included in the systematic review.

Table S4. Clinical outcomes according to location of calciphylaxis.

Table S5. Clinical outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis (derived from case reports, case series, and cohort studies) according to treatment modality ever received.

Table S6. Ongoing calciphylaxis clinical studies registered at clinicaltrials.gov (September 2018).

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.kireports.org/.

Supplementary Material

Cohort studies included in the systematic review.

Case series included in the systematic review.

Case reports included in the systematic review.

Clinical outcomes according to location of calciphylaxis.

Clinical outcomes of patients with calciphylaxis (derived from case reports, case series, and cohort studies) according to treatment modality ever received.

Ongoing calciphylaxis clinical studies registered at clinicaltrials.gov (September 2018).

References

- 1.Moe S.M., Chen N.X. Calciphylaxis and vascular calcification: a continuum of extra-skeletal osteogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:969–975. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazhar A.R., Johnson R.J., Gillen D. Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60:324–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigwekar S.U., Zhao S., Wenger J. A nationally representative study of calcific uremic arteriolopathy risk factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3421–3429. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandenburg V.M., Kramann R., Rothe H. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): data from a large nationwide registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:126–132. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigwekar S.U., Kroshinsky D., Nazarian R.M. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133–146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers N.M., Teubner D.J.O., Coates P.T.H. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: advances in pathogenesis and treatment. Semin Dial. 2007;20(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilmer W.A., Magro C.M. Calciphylaxis: Emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial. 2002;15:172–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An J., Devaney B., Ooi K.Y. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series and literature review. Nephrology. 2015;20:444–450. doi: 10.1111/nep.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden M.R., Goldsmith D.J.A. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torregrosa J.V., Sánchez-Escuredo A., Barros X. Clinical management of calcific uremic arteriolopathy before and after therapeutic inclusion of bisphosphonates. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83(4):231–234. doi: 10.5414/CN107923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torregrosa J.V., Duran C.E., Barros X. Successful treatment of calcific uraemic arteriolopathy with bisphosphonates. Nefrologia. 2012;32:329–334. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2012.Jan.11137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patecki M., Lehmann G., Brasen J.H. A case report of severe calciphylaxis—suggested approach for diagnosis and treatment. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:137. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sewell L.D., Weenig R.H., Davis M.D. Low-dose tissue plasminogen activator for calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1045–1048. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Azhary R.A., Arthur A.K., Davis M.D.P. Retrospective analysis of tissue plasminogen activator as an adjuvant treatment for calciphylaxis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:63–67. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dekkers O.M., Egger M., Altman D.G., Vandenbroucke J.P. Distinguishing case series from cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:37–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathes T., Pieper D. Clarifying the distinction between case series and cohort studies in systematic reviews of comparative studies: potential impact on body of evidence and workload. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:107. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0391-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18:800–804. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan Y.L., Mahony J.F., Turner J.J., Posen S. The vascular lesions associated with skin necrosis in renal disease. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb03996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockerell C.J., Dolan E.T. Widespread cutaneous and systemic calcification (calciphylaxis) in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and renal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:559–562. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine A., Fleming S., Leslie W. Calciphylaxis presenting with calf pain and plaques in four continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients and in one predialysis patient. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:498–502. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafner J., Keusch G., Wahl C. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): A complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954–962. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lue C., Boulware D.W., Sanders P.W. Calciphylaxis mimicking skin lesions of connective tissue diseases. South Med J. 1996;89:1099–1100. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittam L.R., McGibbon D.H., Macdonald D.M. Proximal cutaneous necrosis in association with chronic renal failure. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:778–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleyer A.J., Choi M., Igwemezie B. A case control study of proximal calciphylaxis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:376–383. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flanigan K.M., Bromberg M.B., Gregory M. Calciphylaxis mimicking dermatomyositis: ischemic myopathy complicating renal failure. Neurology. 1998;51:1634–1640. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jhaveri F.M., Woosley J.T., Fried F.A. Penile calciphylaxis: rare necrotic lesions in chronic renal failure patients. J Urol. 1998;160:764–767. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasirajan K., Obermeyer R.J., Lucarelli M.R. Calciphylaxis: calcific angiopathy resulting in acral gangrene: case reports. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 1998;32:447–453. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh D.H., Eulau D., Tokugawa D.A. Five cases of calciphylaxis and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:979–987. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alain J., Poulin Y.P., Cloutier R.A. Calciphylaxis: seven new cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:213–218. doi: 10.1177/120347540000400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Girotto J.A., Harmon J.W., Ratner L.E. Parathyroidectomy promotes wound healing and prolongs survival in patients with calciphylaxis from secondary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2001;130:645–651. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.117101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arch-Ferrer J.E., Beenken S.W., Rue L.W. Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis. Surgery. 2003;134:941–944. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.07.001. discussion 944–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Don B.R., Chin A.I. A strategy for the treatment of calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) employing a combination of therapies. Clin Nephrol. 2003;59:463–470. doi: 10.5414/cnp59463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naik B.J., Lynch D.J., Slavcheva E.G., Beissner R.S. Calciphylaxis: medical and surgical management of chronic extensive wounds in a renal dialysis population. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:304–312. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000095955.75346.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polizzotto M.N., Bryan T., Ashby M.A., Martin P. Symptomatic management of calciphylaxis: a case series and review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slough S., Servilla K.S., Harford A.M. Association between calciphylaxis and inflammation in two patients on chronic dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2006;22:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickels M.R., Junkins-Hopkins J.M., Metkus T.S., Iqbal N. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): case series and review of clinical features and terminology. Endocrinologist. 2007;17:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arenas M.D., Gil M.T., Gutiérrez M.D. Management of calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) with a combination of treatments, including hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Clin Nephrol. 2008;70:261–264. doi: 10.5414/cnp70261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kacso I., Rusu A., Racasan S. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy related to hyperparathyroidism secondary to chronic renal failure. A case-control study. Acta Endocrinologica. 2008;4:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sulkova S.D., Valek M. Skin wounds associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis. Nutrition. 2010;26:910–914. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldwin C., Farah M., Leung M. Multi-intervention management of calciphylaxis: a report of 7 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:988–991. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noureddine L., Landis M., Patel N., Moe S.M. Efficacy of sodium thiosulfate for the treatment for calciphylaxis. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75:485–490. doi: 10.5414/cnp75485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sood A.R., Wazny L.D., Raymond C.B. Sodium thiosulfate-based treatment in calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a consecutive case series. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malabu U.H., Manickam V., Kan G. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy on multimodal combination therapy: Still unmet goal. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/390768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen G.F., Vyas N.S. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of calciphylaxis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:41–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salmhofer H., Franzen M., Hitzl W. Multi-modal treatment of calciphylaxis with sodium-thiosulfate, cinacalcet and sevelamer including long-term data. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2013;37:346–359. doi: 10.1159/000350162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veitch D., Wijesuriya N., McGregor J.M. Clinicopathological features and treatment of uremic calciphylaxis: a case series. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:113–115. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee K.G., Lim A.E.L., Wong J., Choong L.H.L. Clinical features, therapy, and outcome of calciphylaxis in patients with end-stage renal disease on renal replacement therapy: case series. Hemodial Int. 2015;19:611–613. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCulloch N., Wojcik S.M., Heyboer M. Patient outcomes and factors associated with healing in calciphylaxis patients undergoing adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2015;7:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourgeois P., De Haes P. Sodium thiosulfate as a treatment for calciphylaxis: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:520–524. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2016.1163316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grant A., Lee S. A case series and clinical update on calciphylaxis. Hong Kong Journal of Dermatology and Venereology. 2016;24:184–190. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCarthy J.T., el-Azhary R.A., Patzelt M.T. Survival, risk factors, and effect of treatment in 101 patients with calciphylaxis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y., Corapi K.M., Luongo M. Calciphylaxis in peritoneal dialysis patients: a single center cohort study. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:235–241. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S115701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hlusicka J., Veisova E., Ullrych M. Serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations and the outcome of calciphylaxis treatment with sodium thiosulfate. Monatsh Chem. 2017;148:435–440. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gipstein R.M., Coburn J.W., Adams D.A. Calciphylaxis in man: a syndrome of tissue necrosis and vascular calcification in 11 patients with chronic renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:1273–1280. doi: 10.1001/archinte.136.11.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rubinger D., Friedlaender M.M., Silver J. Progressive vascular calcification with necrosis of extremities in hemodialysis patients: a possible role of iron overload. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;7:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(86)80132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ivker R.A., Woosley J., Briggaman R.A. Calciphylaxis in three patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kriskovich M.D., Holman J.M., Haller J.R. Calciphylaxis: is there a role for parathyroidectomy? Laryngoscope. 2000;110:603–607. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mureebe L., Moy M., Balfour E. Calciphylaxis: a poor prognostic indicator for limb salvage. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:1275–1279. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.115378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Podymow T., Wherrett C., Burns K.D. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of calciphylaxis: a case series. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2176–2180. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.11.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Basile C., Montanaro A., Masi M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy: a case series. J Nephrol. 2002;15:676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Milas M., Bush R.L., Lin P. Calciphylaxis and nonhealing wounds: the role of the vascular surgeon in a multidisciplinary treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:501–507. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bardsley S., Coutts R., Wilson C. Calciphylaxis and its surgical significance. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:356–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matstusoka S., Tominaga Y., Uno N. Calciphylaxis: a rare complication of patients who required parathyroidectomy for advanced renal hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg. 2005;29:632–635. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Araya C.E., Fennell R.S., Neiberger R.E., Dharnidharka V.R. Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1161–1166. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01520506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maeda H., Tokumoto M., Yotsueda H. Two cases of calciphylaxis treated by parathyroidectomy: importance of increased bone formation. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67:397–402. doi: 10.5414/cnp67397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Neil B., Southwick A.W. Three cases of penile calciphylaxis: diagnosis, treatment strategies, and the role of sodium thiosulfate. Urology. 2012;80:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia C.P., Roson E., Peon G. Calciphylaxis treated with sodium thiosulfate: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nigwekar S.U., Brunelli S.M., Meade D. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1162–1170. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09880912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zitt E., Konig M., Vychytil A. Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1232–1240. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Malbos S., Urena-Torres P., Bardin T., Ea H.K. Sodium thiosulfate is effective in calcific uremic arteriolopathy complicating chronic hemodialysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Russo D., Capuano A., Cozzolino M. Multimodal treatment of calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): a case series. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9:108–112. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santos P.W., He J., Tuffaha A., Wetmore J.B. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with mortality in calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:2247–2256. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fox R., Banowsky L.H., Cruz A.B., Jr. Post-renal transplant calciphylaxis: Successful treatment with parathyroidectomy. Journal of Urol. 1983;129:362–363. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vassa N., Twardowski Z.J., Campbell J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in calciphylaxis-induced skin necrosis in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:878–881. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rudwaleit M., Schwarz A., Trautmann C. Severe calciphylaxis in a renal patient on long-term oral anticoagulant therapy. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16:344–348. doi: 10.1159/000169021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boerma E.C., Hene R.J. A calcareous calamity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2453–2454. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.11.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dean S.M., Werman H. Calciphylaxis: a favorable outcome with hyperbaric oxygen. Vasc Med. 1998;3:115–120. doi: 10.1177/1358836X9800300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katsamakis G., Lukovits T.G., Gorelick P.B. Calcific cerebral embolism in systemic calciphylaxis. Neurology. 1998;51:295–297. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.James L.R., Lajoie G., Prajapati D. Calciphylaxis precipitated by ultraviolet light in a patient with end- stage renal disease secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:932–936. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edwards R.B., Jaffe W., Arrowsmith J., Henderson H.P. Calciphylaxis: a rare limb and life threatening cause of ischaemic skin necrosis and ulceration. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:253–255. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Patetsios P., Bernstein M., Kim S. Severe necrotizing mastopathy caused by calciphylaxis alleviated by total parathyroidectomy. Am Surg. 2000;66:1056–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kay P.A., Sanchez W., Rose J.F. Calciphylaxis causing necrotizing mastitis: a case report. Breast. 2001;10:540–543. doi: 10.1054/brst.2000.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dwyer K.M., Francis D.M.A., Hill P.A., Murphy B.F. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy: local treatment and hyperbaric oxygen therapy [5] Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1148–1149. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.6.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garrigue V., Lorho R., Canet S. Necrotic skin lesions in a dialysis patient: a multifactorial entity. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57:163–166. doi: 10.5414/cnp57163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nahm W.K., Badiavas E., Touma D.J. Calciphylaxis with peau d'orange induration and absence of classical features of purpura, livedo reticularis and ulcers. J Dermatol. 2002;29:209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bahar G., Mimouni D., Feinmesser M. Subtotal parathyroidectomy: a possible treatment for calciphylaxis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82:390–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Parker R.W., Mouton C.P., Young D.W., Espino D.V. Early recognition and treatment of Calciphylaxis. South Med J. 2003;96:53–55. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000047841.53171.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cicone J.S., Petronis J.B., Embert C.D., Spector D.A. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104–1108. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Monney P., Nguyen Q.V., Perroud H., Descombes E. Rapid improvement of calciphylaxis after intravenous pamidronate therapy in a patient with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2130–2132. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oikawa S., Osajima A., Tamura M. Development of proximal calciphylaxis with penile involvement after parathyroidectomy in a patient on hemodialysis. Intern Med. 2004;43:63–68. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brucculeri M., Cheigh J., Bauer G., Serur D. Long-term intravenous sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of a patient with calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2005;18:431–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guerra G., Shah R.C., Ross E.A. Rapid resolution of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate and continuous venovenous haemofiltration using low calcium replacement fluid: case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1260–1262. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maroulis J.C., Fourtounas C., Vlachojannis J.G. Calciphylaxis: a complication of end-stage renal disease improved by parathyroidectomy. Hormones (Athens) 2006;5:210–213. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meissner M., Bauer R., Beier C. Sodium thiosulphate as a promising therapeutic option to treat calciphylaxis. Dermatology. 2006;212:373–376. doi: 10.1159/000092290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Musso C.G., Enz P.A., Guelman R. Non-ulcerating calcific uremic arteriolopathy skin lesion treated successfully with intravenous ibandronate. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26:717–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma A., Burkitt-Wright E., Rustom R. Cinacalcet as an adjunct in the successful treatment of calciphylaxis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1295–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shiraishi N., Kitamura K., Miyoshi T. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:151–154. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thang O.H.D., Jaspars E.H., ter Wee P.M. Necrotizing mastitis caused by calciphylaxis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2020–2021. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tokashiki K., Ishida A., Kouchi M. Successful management of critical limb ischemia with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a chronic hemodialysis patient. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66:140–143. doi: 10.5414/cnp66140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Velasco N., MacGregor M.S., Innes A., MacKay I.G. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with cinacalcet—an alternative to parathyroidectomy? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1999–2004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ackermann F., Levy A., Daugas E. Sodium thiosulfate as first-line treatment for calciphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1336–1337. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.10.1336. author reply 1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bazari H., Jaff M.R., Mannstadt M., Yan S. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 7–2007. A 59-year-old woman with diabetic renal disease and nonhealing skin ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1049–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc069038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hanafusa T., Yamaguchi Y., Tani M. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lai M.Y., Lin Y.P., Yang W.C. Fever with fulminant skin necrosis and digital gangrene in a uraemic woman. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1473–1474. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Aabed G., Furayh O.A., Al-Lehbi A. Calciphylaxis-associated second renal graft failure and patient loss: a case report and review of the literature. Exp Clin Transplant. 2008;6:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Da Costa J.B., Da Costa A.G., Gomes M.M. Pamidronate as a treatment option in calciphylaxis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1128–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hitti W.A., Papadimitriou J.C., Bartlett S., Wali R.K. Spontaneous cutaneous ulcers in a patient with a moderate degree of chronic kidney disease: a different spectrum of calciphylaxis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:181–183. doi: 10.1080/00365590701570599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kyritsis I., Gombou A., Griveas I. Combination of sodium thiosulphate, cinacalcet, and paricalcitol in the treatment of calciphylaxis with hyperparathyroidism. Int J Artif Organs. 2008;31:742–744. doi: 10.1177/039139880803100809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mohammed I.A., Sekar V., Bubtana A.J. Proximal calciphylaxis treated with calcimimetic 'Cinacalcet.'. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:387–389. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Subramaniam K., Wallace H., Sinniah R., Saker B. Complete resolution of recurrent calciphylaxis with long-term intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:30–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.TAN Bhatty, Riaz K. Calciphylaxis mimicking penile gangrene: A case report. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:1355–1359. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kalisiak M., Courtney M., Lin A., Brassard A. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): Successful treatment with sodium thiosulfate in spite of elevated serum phosphate. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:S29–S34. doi: 10.2310/7750.2009.00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.León L.R. Treating distal calciphylaxis with therapy associated with sevelamer and bisphosphonates. Nefrologia. 2009;29:92–93. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.2009.29.1.92.2.en.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Musso C.G., Enz P., Vidal F. Use of sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20:1065–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nigliazzo A., Khoo S., Saxe A. Calciphylaxis. Am Surg. 2009;75:516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sánchez M.P., Pérez M.C., Lorman R.S., Borroy C.S. Proximal calciphylaxis in a liver and kidney transplant patient. Nefrologia. 2009;29:489–490. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.2009.29.5.5387.en.full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shaheen M., Hammoud D., Patel D. Non-healing skin ulcers secondary to calciphylaxis with Candida tropicalis fungemia in an end-stage renal disease patient. Hong Kong Journal of Nephrology. 2009;11:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yeh S.M., Hwang S.J., Chen H.C. Treatment of severe metastatic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2009;13:163–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Campanino P.P., Tota D., Bagnera S. Breast calciphylaxis following coronary artery bypass grafting completely resolved with total parathyroidectomy. Breast J. 2010;16:544–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dong X.E., Bishop J., Brown E. Surgical management of calciphylaxis associated with primary hyperparathyroidism: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/823210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Khalpey Z., Nehs M.A., Elbardissi A.W. The importance of prevention of calciphylaxis in patients who are at risk and the potential fallibility of calcimimetics in the treatment of calciphylaxis for patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. NDT Plus. 2010;3:68–70. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kirschberg O., Saers T., Krakamp B. Calciphylaxis—case report and review of the literature. Dialysis and Transplantation. 2010;39:401–403. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brucculeri M., Haydon A.H. Calciphylaxis presenting in early chronic kidney disease with mixed hyperparathyroidism. Int J NephrolRenovasc Dis. 2011;4:157–160. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S27607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cadavid J.C., DiVietro M.L., Torres E.A. Warfarin-induced pulmonary metastatic calcification and calciphylaxis in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2011;139:1503–1506. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Castro H., Cabeza-Rivera F., Green D. Combined therapy with sodium thiosulfate and parathyroidectomy in a patient with calciphylaxis. Dialysis and Transplantation. 2011;40:264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Conde Rivera O., Camba Caride M., Novoa Fernandez E. Multidisciplinary treatment. A therapeutic option to treat calciphylaxis. Nefrologia. 2011;31:614–616. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.Jun.10954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Khalpey Z., Tullius S.G. Refractory calciphylaxis. Am J Surg. 2011;202:e27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Miceli S., Milio G., Placa S.L. Sodium thiosulfate not always resolves calciphylaxis: an ambiguous response. Ren Fail. 2011;33:84–87. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.536288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Scola N., Gackler D., Stucker M., Kreuter A. Complete clearance of calciphylaxis following combined treatment with cinacalcet and sodium thiosulfate. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1030–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Shiell K.A., Andrews P.A. A painful skin rash in a patient with Stage V chronic kidney disease. NDT Plus. 2011;4:201–204. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li J.Y.Z., Yong T.Y., Choudhry M. Successful treatment of calcific uremic arteriolopathy with sodium thiosulfate in a renal transplant recipient. Ren Fail. 2012;34:645–648. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.656560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lo Monte A.I., Bellavia M., Damiano G. A complex case of fatal calciphylaxis in a female patient with hyperparathyroidism secondary to end stage renal disease of graft and coexistence of haemolytic uremic syndrome. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2012;156:262–265. doi: 10.5507/bp.2012.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Marshall B.J., Johnson R.E. Case report on calciphylaxis: an early diagnosis and treatment may improve outcome. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2012;4:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sandhu G., Gini M.B., Ranade A. Penile calciphylaxis: a life-threatening condition successfully treated with sodium thiosulfate. Am J Ther. 2012;19:e66–e68. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181e3b0f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.van Noten C., van Doorn K.J., Vermander E. Maximal conservative therapy of calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin Nephrol. 2012;78:61–63. doi: 10.5414/cn107016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Van Rijssen L.B., Brenninkmeijer E.E.A., Nieveen Van Dijkum E.J.M. Secondary hyperparathyroidism: uncommon cause of a leg ulcer. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Burnie R., Smail S., Javaid M.M. Calciphylaxis and sodium thiosulphate: a glimmer of hope in desperate situation. J Ren Care. 2013;39:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2013.12008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Checheriţã I.A., Smarandache D., Rãdulescu D. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy in hemodialyzed patients. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2013;108:736–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kumar V., Patel N. Images in vascular medicine. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy of the penis. Vasc Med. 2013;18:239. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13493826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Seferi S., Barbullushi M., Rroji M. An unusual site of calciphylaxis: a case report and review of the literature. BANTAO Journal. 2013;11:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Smith S., Inaba A., Murphy J. A case report: Radiological findings in an unusual case of calciphylaxis 16 years after renal transplantation. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:1623–1626. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Steele K.T., Sullivan B.J., Wanat K.A. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis in a patient with end-stage renal disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:829–832. doi: 10.1111/cup.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Vanparys J., Sprangers B., Sagaert X., Kuypers D.R. Chronic wounds in a kidney transplant recipient with moderate renal impairment. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:128–131. doi: 10.2143/ACB.3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Deng Y., Xie G., Li C. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy ameliorated by hyperbaric oxygen therapy in high-altitude area. Ren Fail. 2014;36:1139–1141. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2014.917672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gallimore G.G., Curtis B., Smith A., Benca M. Curious case of calciphylaxis leading to acute mitral regurgitation. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sprague S.M. Painful skin ulcers in a hemodialysis patient. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:166–173. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Stavros K., Motiwala R., Zhou L. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2014;15:108–111. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Tindni A., Gaurav K., Panda M. Non-healing painful ulcers in a patient with chronic kidney disease and role of sodium thiosulfate: a case report. Cases J. 2014;1:178. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yeh H.T., Huang I.J., Chen C.M., Hung Y.M. Regression of vascular calcification following an acute episode of calciphylaxis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Buscher K., Gabriëls G., Barth P., Pavenstädt H. Breast pain in a patient on dialysis: a rare manifestation of calcific uraemic arteriolopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Disbrow M.B., Qaqish I., Kransdorf M., Chakkera H.A. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Sarkis E. Penile and generalised calciphylaxis in peritoneal dialysis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-209153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Tamayo-Isla R.A., Cruz M.C. Calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease prior to dialytic treatment: a case report and literature review. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2015;8:13–18. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S78310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yu Z., Gu L., Pang H. Sodium thiosulfate: an emerging treatment for calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2015;5:77–82. doi: 10.1159/000380945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Aihara S., Yamada S., Uchida Y. The successful treatment of calciphylaxis with sodium thiosulfate and hyperbaric oxygen in a non-dialyzed patient with chronic kidney disease. Intern Med. 2016;55:1899–1905. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]