Abstract

Background

Several antibiotics have been evaluated in Crohn's disease (CD), however randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have produced conflicting results.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of antibiotics for induction and maintenance of remission in CD.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, the Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Register and Clinicaltrials.gov database from inception to 28 February 2018. We also searched reference lists and conference proceedings.

Selection criteria

RCTs comparing antibiotics to placebo or an active comparator in adult (> 15 years) CD patients were considered for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors screened search results and extracted data. Bias was evaluated using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. The primary outcomes were failure to achieve clinical remission and relapse. Secondary outcomes included clinical response, endoscopic response, endoscopic remission, endoscopic relapse, histologic response, histologic remission, adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, withdrawal due to AEs and quality of life. Remission is commonly defined as a Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) of < 150. Clinical response is commonly defined as a decrease in CDAI from baseline of 70 or 100 points. Relapse is defined as a CDAI > 150. For studies that enrolled participants with fistulizing CD, response was defined as a 50% reduction in draining fistulas. Remission was defined as complete closure of fistulas. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes. We calculated the mean difference (MD) and corresponding 95% CI for continuous outcomes. GRADE was used to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

Thirteen RCTs (N = 1303 participants) were eligible. Two trials were rated as high risk of bias (no blinding). Seven trials were rated as unclear risk of bias and four trials were rated as low risk of bias. Comparisons included ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) versus placebo, rifaximin (800 to 2400 mg daily) versus placebo, metronidazole (400 mg to 500 mg twice daily) versus placebo, clarithromycin (1 g/day) versus placebo, cotrimoxazole (960 mg twice daily) versus placebo, ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (250 mg four time daily) versus methylprednisolone (0.7 to 1 mg/kg daily), ciprofloxacin (500 mg daily), metronidazole (500 mg daily) and budesonide (9 mg daily) versus placebo with budesonide (9 mg daily), ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) versus mesalazine (2 g twice daily), ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) with adalimumab versus placebo with adalimumab, ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) with infliximab versus placebo with infliximab, clarithromycin (750 mg daily) and antimycobacterial versus placebo, and metronidazole (400 mg twice daily) and cotrimoxazole (960 mg twice daily) versus placebo. We pooled all antibiotics as a class versus placebo and antibiotics with anti‐tumour necrosis factor (anti‐TNF) versus placebo with anti‐TNF.

The effect of individual antibiotics on CD was generally uncertain due to imprecision. When we pooled antibiotics as a class, 55% (289/524) of antibiotic participants failed to achieve remission at 6 to 10 weeks compared with 64% (149/231) of placebo participants (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.98; 7 studies; high certainty evidence). At 10 to 14 weeks, 41% (174/428) of antibiotic participants failed to achieve a clinical response compared to 49% (93/189) of placebo participants (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.93; 5 studies; moderate certainty evidence). The effect of antibiotics on relapse in uncertain. Forty‐five per cent (37/83) of antibiotic participants relapsed at 52 weeks compared to 57% (41/72) of placebo participants (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.47; 2 studies; low certainty evidence). Relapse of endoscopic remission was not reported in the included studies. Antibiotics do not appear to increase the risk of AEs. Thirty‐eight per cent (214/568) of antibiotic participants had at least one adverse event compared to 45% (128/284) of placebo participants (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.02; 9 studies; high certainty evidence). The effect of antibiotics on serious AEs and withdrawal due to AEs was uncertain. Two per cent (6/377) of antibiotic participants had at least one adverse event compared to 0.7% (1/143) of placebo participants (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.29 to 10.01; 3 studies; low certainty evidence). Nine per cent (53/569) of antibiotic participants withdrew due to AEs compared to 12% (36/289) of placebo participants (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.29; 9 studies; low certainty evidence) is uncertain. Common adverse events in the studies included gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory tract infection, abscess formation and headache, change in taste and paraesthesia

When we pooled antibiotics used with anti‐TNF, 21% (10/48) of patients on combination therapy failed to achieve a clinical response(50% closure of fistulas) or remission (closure of fistulas) at week 12 compared with 36% (19/52) of placebo and anti‐TNF participants (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.10; 2 studies; low certainty evidence). These studies did not assess the effect of antibiotics and anti‐TNF on clinical or endoscopic relapse. Seventy‐seven per cent (37/48) of antibiotics and anti‐TNF participants had an AE compared to 83% (43/52) of anti‐TNF and placebo participants (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.12; 2 studies, moderate certainty evidence). The effect of antibiotics and anti‐TNF on withdrawal due to AEs is uncertain. Six per cent (3/48) of antibiotics and anti‐TNF participants withdrew due to an AE compared to 8% (4/52) of anti‐TNF and placebo participants (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.19 to 3.45; 2 studies, low certainty evidence). Common adverse events included nausea, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infections, change in taste, fatigue and headache

Authors' conclusions

Moderate to high quality evidence suggests that any benefit provided by antibiotics in active CD is likely to be modest and may not be clinically meaningful. High quality evidence suggests that there is no increased risk of adverse events with antibiotics compared to placebo. The effect of antibiotics on the risk of serious adverse events is uncertain. The effect of antibiotics on maintenance of remission in CD is uncertain. Thus, no firm conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of antibiotics for maintenance of remission in CD can be drawn. More research is needed to determine the efficacy and safety of antibiotics as therapy in CD

Plain language summary

Antibiotics for the treatment of Crohn's disease

What is Crohn's disease?

Crohn's disease (CD) is an inflammatory disorder that can affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Common symptoms of CD include fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain and weight loss. CD is characterized by periods of relapse when people experience symptoms and periods of remission when the symptoms stop.

What are antibiotics?

Antibiotics are medications used to treat bacterial infections. Antibiotics are designed to target specific bacterial populations and have different mechanisms of action to stop a bacterial population from growing or eradicate the bacteria.

What is the purpose this study?

Antibiotics are commonly used for managing patients with CD because the inflammatory process in the bowel was believed to be triggered by a specific bacterial pathogen. Elimination of this bacterial target would allow the inflammatory process to resolve. However, current clinical guidelines do not recommend use of antibiotic agents to induce or maintain clinical remission in patients with CD because there is no definitive evidence to suggest a benefit to using antibiotics in this way.

How was this study performed?

A systematic review of current literature was performed to determine whether antibiotic therapy is effective to induce or maintain remission in CD. An electronic search of several databases was performed and studies that met our inclusion criteria were selected for further evaluation. Statistical analyses were performed to determine which specific antibiotics had an overall benefit.

What were the results?

Several antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, clarithromycin, rifaximin and cotrimoxazole, have been studied in CD. Most of the included studies were small in size. When we pooled antibiotics as a class, these drugs provided a modest benefit over placebo (i.e. a fake drug such as a sugar pill) for induction of remission and improvement of CD symptoms. For example, remission rates were 45% (253/542) in participants who received antibiotics compared to 36% (82/231) in participants who received placebo. We rated the quality of evidence supporting this outcome as high. Few studies assessed the use of antibiotics for maintenance of remission in CD. The impact of antibiotics on preventing relapse in CD is uncertain. Antibiotics do not appear to increase the risk of side effects when compared to placebo. Common side effects reported in the studies included gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory tract infection, abscess formation, headache, change in taste and paraesthesia (pins and needles in the extremities). Serious side effects were not well reported in the studies and the impact of antibiotics on the risk of serious side effects is uncertain.

Conclusions

Moderate to high quality evidence suggests that any benefit provided by antibiotics in active CD is likely to be very modest. High quality evidence suggests that there is no increased risk of side effects with antibiotics compared to placebo. The effect of antibiotics on the risk of serious side effects is uncertain. The effect of antibiotics on preventing relapse in CD is uncertain. Thus, no firm conclusions regarding the benefits and harms of antibiotics for maintenance of remission in CD can be drawn. More research is needed to determine the harms and benefits of antibiotic therapy in CD.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Crohn's disease (CD) is an inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that most commonly affects the ileum and the colon. Characteristic histologic features of the disease include transmural inflammation and mucosal ulceration. The exact etiology of CD is unclear, however both genetic and environmental factors are important contributors (Elson 2005; Scribano 2013). In this regard, the human microbiome is considered to be a key environmental risk factor.

In animal models, interactions between the mucosal immune system and commensal bacteria contribute to the observed pathological changes seen in CD (Elson 1995; Elson 2005; Rath 1999). Subsequent human studies have demonstrated that patients with CD have higher concentrations of intestinal and colonic bacteria (Scribano 2013), and higher populations of specific bacteria (Gevers 2014), compared to healthy controls. Patients with CD may also have impaired barrier function that facilitates translocation of microbes into the mucosa (Marks 2006).

Pathogenic bacterial strains, including Escherichia coli (Mylonaki 2005), have been isolated in the mucosal and mesenteric lymph nodes of these patients (Ambrose 1984). Furthermore, there is a change in the microbial composition with fewer species overall and a relative overrepresentation of Enterobacteriaceae,Proteobacteria,Actinobacteria (Sartor 2008), and Bacteroides (Barnich 2007). These observations support the notion that the pathological response in CD is driven by an abnormal response to the host microbiome and that manipulation of the flora though antibiotic treatment might be a potential therapy (Sartor 2008).

Description of the intervention

Given the proposed link between increased intestinal bacterial concentrations and chronic inflammation, antibiotics have been considered for the treatment of CD (Swidsinski 2002). Studies have suggested Escherichia coli as specific bacterial targets, among others (Mylonaki 2005; Sartor 2008).

How the intervention might work

Several antibiotics have been evaluated for the treatment of CD. Reduction of the bacterial load in the intestinal mucosa might reduce the pathological immune response in the intestinal mucosa (Scribano 2013; Swidsinski 2002). Furthermore, antibiotics also act to limit bacterial translocation and reduce the concentration of adherent bacteria to the lumen and mucosa (Scribano 2013). In patients who have high levels of Escherichia in their microbiome, treatment with mesalamine showed a decrease in intestinal inflammation. This further suggests the crucial role the gut microbiome may have in IBD pathophysiology and the potential use for antimicrobial agents (Kostic 2014). Cumulatively, these data have raised the possibility that alteration of the mucosal flora may have a therapeutic role in CD by inhibiting the stimulus for pathogenic immune responses (Ott 2004; Swidsinski 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

Given the extensive animal and human data that support the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of CD, it is reasonable to postulate that antibiotic therapy might be effective for either induction or maintenance of remission in CD. However, several potential problems exist with this approach. First, use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics is a very blunt strategy that may aggravate the aforementioned dysbiosis. Second, the resident flora are determined by both genetic and dietary factors that may be difficult or impossible to modify on a chronic basis. Therefore, treatment, if effective, might have to be continued indefinitely. Finally broad‐spectrum antibiotic therapy is associated with important adverse effects, notably an increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection. For these reasons evidence from high quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is necessary before antibiotics are accepted as effective and safe for the treatment of CD.

No current recommendations exist regarding the antibiotic of choice, dose, or duration for treatment of CD. The most recent guidelines published by the World Gastroenterology Organisation support the use of antibiotics in perianal disease, fistulizing disease, and bacterial overgrowth secondary to stricturing disease, despite limited supporting evidence (Bernstein 2016). There is evidence regarding antibiotic use in post‐operative CD management (Bernstein 2016).

Objectives

To determine whether antibiotic therapy is safe and effective for induction or maintenance of remission in CD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs of adult patients (> 15 years of age) were considered for inclusion. Induction of remission studies needed to have a minimum duration of at least four weeks to be considered for inclusion. Maintenance of remission studies needed to have a minimum duration of at least six months to be considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Patients with active or quiescent CD (as defined by the original studies) were considered for inclusion.

Types of interventions

Trials that compare oral antibiotic therapy to a placebo or an active comparator were considered for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure for induction of remission studies was the proportion of patients who failed to achieve remission, as defined by the original studies. The primary outcome for maintenance of remission studies was the proportion of patients who relapsed, as defined by the included studies.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary efficacy outcomes, as defined by the original studies, were the proportion of patients:

1. Who failed to achieve clinical response (as defined by the original studies);

2. Who failed to achieve endoscopic response (as defined by the original studies);

3. Who failed to achieve endoscopic remission (as defined by the original studies);

4. Who failed to achieve histological response (as defined by the original studies);

5. Who failed to achieve histological remission (as defined by the original studies);

6. Who had an endoscopic relapse (as defined by the original studies);

7. Who failed to achieve both clinical and endoscopic response (as defined by the original studies);

8. Who failed to achieve both clinical and endoscopic remission (as defined by the original studies); and

9. Health‐related quality of life (as measured by a validated quality of life instrument). Safety outcomes were the proportion of patients:

10. With any adverse event (AE);

11. With serious adverse events (SAE); and

12. Who withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for relevant studies:

1. MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to present);

2. Embase (Ovid, 1984 to present);

3. CENTRAL; and

4. The Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Register.

5. Clinicaltrials.gov

The search strategies are listed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also searched the references listed in relevant studies and review articles for additional citations not identified in the search. Furthermore, conference proceedings from major meetings (Digestive Disease Week, the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation congress, and the United European Gastroenterology Week conference) from the last five years were searched for studies published in abstract form only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (CMT and CEP) screened the search results independently for eligible studies based on the inclusion criteria as listed. Disagreements were discussed until a consensus is reached. Any disagreements were brought to a third author (JKM) for resolution.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted from included studies by two independent authors (CMT and CEP). Any disagreements over extracted data were first discussed and then brought to a third author (JKM) for resolution if deemed necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of included studies was independently assessed by two authors (CMT and CEP) using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed several factors including sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias. Studies were judged to be at high, low or unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements regarding risk of bias were first discussed and then brought to a third author (JKM) for resolution.

We used the GRADE approach to determine the overall certainty of evidence supporting both primary and selected secondary outcomes (Guyatt 2008; Schünemann 2011). For the 'Summary of findings' tables, we included the following outcomes: failure to achieve clinical remission (at study endpoint), failure to maintain clinical remission (or relapse at study endpoint), failure to achieve clinical response (at study endpoint), failure to maintain endoscopic remission (or endoscopic relapse at study endpoint), adverse events, adverse events, serious adverse events and study withdrawal due to adverse events. Evidence from RCTs was considered high certainty. However, the certainty of the evidence could have been downgraded after considering the following factors:

1. Risk of bias;

2. Indirect evidence;

3. Inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity);

4. Imprecision; and

5. Publication bias.

Each outcome was reviewed to determine the overall certainty of evidence supporting the outcome. The outcome was classified as high certainty (the estimate of effect is very unlikely to be changed despite further research); moderate certainty (the estimate of effect is unlikely to be changed despite further research); low certainty (the estimate of effect may be changed despite further research) or very low certainty (the estimate of effect likely will be changed with further research).

Measures of treatment effect

Review Manager (RevMan 5.3.5) was used to analyse the data on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes and the mean difference (MD) and corresponding 95% CI for continuous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

To deal with repeated observations on participants, we determined appropriate fixed intervals for follow‐up for each outcome. Cross‐over trials were included if data was available for the first phase of the trial prior to cross‐over. To deal with events that may re‐occur (e.g. adverse events), we reported on the proportion of participants who experience at least one event. Separate comparisons were performed for studies that compared antibiotics to placebo and for studies that compared antibiotics to other active therapies. We also performed separate comparisons for each type of antibiotic. If we encountered multiple treatment groups (e.g. different dose groups of antibiotics), we divided the placebo group across the treatment groups or we combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison as appropriate.

Dealing with missing data

An intention‐to‐treat analysis was used for dichotomous outcomes whereby patients with missing treatment outcomes were assumed to be treatment failures. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of this assumption on the effect estimate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi² test (a P value of 0.10 was considered statistically significant) and the I² statistic. We considered an I² statistic> 75% to indicate high heterogeneity among study data, > 50% indicated moderate heterogeneity and > 25% will indicated low heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Sensitivity analysis were conducted to explore possible explanations for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We initially compared outcomes listed in the protocol to those reported in the published manuscript. If we did not have access to the protocol, we used the outcomes listed in the methods sections of the published manuscript compared to what was reported in the results section. If any pooled analyses included 10 or more studies, we investigated potential publication bias using funnel plots (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

Data for meta‐analysis from individual trials were combined when the interventions, patient groups and outcomes were similar, as deemed by author consensus. We calculated the pooled RR and corresponding 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes and the pooled MD and corresponding 95% CI for continuous outcomes. The standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI was calculated when different scales were used to measure the same outcome. A fixed‐effect model was used to pool data unless significant heterogeneity existed between the studies. A random‐effects model was used if heterogeneity existed (I² = 50 to 75%). We did not pool data for meta‐analysis if a high degree of heterogeneity (I² ≥ 75%) was found.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Planned subgroup analysis (data allowing) included:

a) Patient baseline characteristics (i.e. sex, age, weight, disease duration, disease severity, time since diagnosis, concomitant medication, objective markers of inflammation such as C‐reactive protein, and previous exposure to anti‐tumour necrosis factor‐alpha therapy); and

b) Different antibiotic doses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to use sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of random‐effects and fixed‐effect modelling, risk of bias, type of report (full manuscript, abstract or unpublished data) and loss to follow‐up on the pooled effect estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The literature search conducted on 28 February 2018 retrieved 2334 records for consideration. We removed all duplicate records, which left 1803 records for screening. Two authors (CMT and CEP) reviewed the titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate. Forty‐eight articles were selected for full text review (see Figure 1). Thirty reports of 25 studies were excluded with reasons (See Characteristics of excluded studies). Seventeen reports of 13 trials met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (See Characteristics of included studies). One ongoing study was identified (NCT02240108).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the 13 eligible RCTs identified (N = 1303), five different antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, clarithromycin, rifaximin and cotrimoxazole) were evaluated. Eleven of these trials were placebo‐controlled (Ambrose 1985; Arnold 2002; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009; West 2004), and two were active comparator trials (Colombel 1999; Prantera 1996). Two of the placebo‐controlled trials also included active comparator arms (Ambrose 1985; Thia 2009). Patients were adults with active CD at the time of randomisation. The majority of the included studies defined an adult as 18 years of age or older, however, Steinhart 2002, Ambrose 1985 and Thia 2009 included patients 14, 15 and 16 years of age or older, respectively.

Four placebo‐controlled RCTs (Arnold 2002; Dewint 2014; Thia 2009; West 2004) evaluated ciprofloxacin. One active comparator trial randomised patients to ciprofloxacin or oral mesalamine (Colombel 1999). In two studies, ciprofloxacin was administered in conjunction with an anti‐TNF agent (Dewint 2014; West 2004). In the Dewint 2014 study, all patients were treated with self‐administered adalimumab at an induction dose of 160 mg at day 0 and 80 mg at week 2, followed by maintenance of 40 mg every 4 weeks until week 24. In the West 2004 study, all participants received infliximab at a dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 6, 8 and 12. Rifaximin was evaluated in two placebo‐controlled RCTs (Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012). Metronidazole was studied in three induction trials (Ambrose 1985; Steinhart 2002; Thia 2009) and one maintenance trial (Sutherland 1991). Two studies evaluated metronidazole in combination with other therapeutic agents. In Prantera 1996, patients were assigned to metronidazole combined with ciprofloxacin or methylprednisolone, while patients enrolled in Steinhart 2002 received metronidazole combined with ciprofloxacin or placebo. All participants in the Steinhart 2002 study received budesonide (9 mg/day). One study compared a combination of cotrimoxazole and metronidazole with placebo (Ambrose 1985). Two trials compared clarithromycin to placebo (Lieper 2008; Selby 2007). In Lieper 2008 patients were randomised to placebo or clarithromycin and followed for three months. Selby 2007 assigned patients to clarithromycin, oral rifabutin, oral clofazimine or placebo, in addition to a tapering course of prednisolone.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐five studies were excluded with reasons after the full text review was performed. In ten studies, data on outcomes of interest were not available in the manuscript, (Allan 1997; Biancone 1998; Goodgame 2001; Gui 1997; Hartley‐Asp 1981; Jigaranu 2014; Laudage 1983; Lee 2018; Mitelman 1982; Turunen 1995) Two of these studies were cross‐over trials that did not report on outcomes pre‐crossover (Blichfeldt 1978; Ursing 1982). Nine trials were not RCTs (Bernstein 1992; Gilat 1982; Jaworski 2016; Koretz 1997; Leiper 2000; Melmed 2009; Ronge 2007; Steele 2009; To 1995). Three trials was terminated and data were not available (Koch 2007; Rogler 2014; Steinhart 2008). One study evaluated rectal therapy, which was beyond the scope of this review (Maeda 2010).

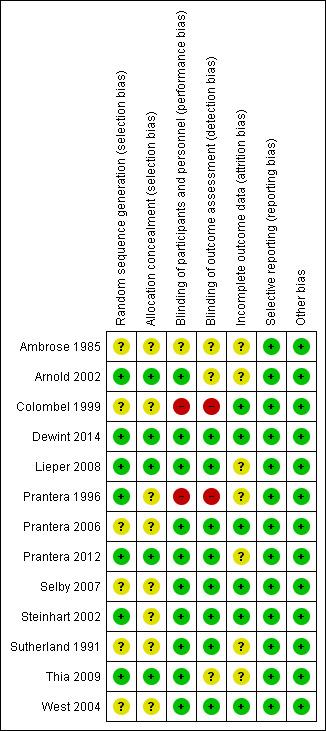

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for the included studies is summarized in Figure 2. Overall, most studies received low or unclear risk of bias ratings for the for seven domains.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Six of the included studies did not adequately describe the methods used to for random sequence generation and therefore received an unclear risk of bias assessment for this domain (Ambrose 1985; Colombel 1999; Prantera 2006; Selby 2007; Sutherland 1991; West 2004). The remaining seven studies were rated as low risk of bias for this item (Arnold 2002; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 1996; Prantera 2012; Steinhart 2002; Thia 2009).

Eight of the included studies did not adequately describe the methods used to conceal allocation and therefore received an unclear risk of bias rating for this domain (Ambrose 1985; Colombel 1999; Prantera 1996; Prantera 2006; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; West 2004) . The remaining five studies received a low risk of bias rating for this item (Arnold 2002; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 2012; Thia 2009) .

Blinding

One study did not adequately describe whether participants and personnel were blinded, and therefore received an unclear risk of bias rating for this domain (Ambrose 1985). A total of 10 studies were rated as low risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel (Arnold 2002; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009; West 2004). Two studies were rated as high risk of bias for this domain (Colombel 1999; Prantera 2006). In Colombel 1999, participants and investigators were not blinded. In Prantera 1996, patients were blinded but some investigators were unblinded.

It was unclear whether outcome assessors were blinded in three studies (Ambrose 1985; Arnold 2002; Thia 2009). Eight of the included studies were rated as low risk of bias for blinded of outcome assessment (Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; West 2004), while two studies did not employ blinded outcome assessment and received high risk of bias ratings (Colombel 1999; Prantera 1996).

Incomplete outcome data

Seven of the included studies were rated as unclear risk of bias with regard to incomplete outcome data (Ambrose 1985; Arnold 2002; Lieper 2008; Prantera 1996; Prantera 2012; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009). The remaining six studies were rated as low risk of bias (Colombel 1999; Dewint 2014; Prantera 2006; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; West 2004).

Selective reporting

All studies were rated as low risk of bias for selective reporting (Ambrose 1985; Arnold 2002; Colombel 1999; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 1996; Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009; West 2004).

Other potential sources of bias

All studies were rated as low risk of bias for other sources of bias (Ambrose 1985; Arnold 2002; Colombel 1999; Dewint 2014; Lieper 2008; Prantera 1996; Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012; Selby 2007; Steinhart 2002; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009; West 2004).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antibiotic compared to placebo for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Antibiotic compared to placebo for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Antibiotic Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Antibiotic | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up: 6‐10 weeks |

645 per 1,000 | 555 per 1,000 (490 to 632) | RR 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98) | 773 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 Antibiotics included Cotrimoxazole, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin, Clarithromycin, and Rifaximin |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 52 weeks |

569 per 1,000 | 495 per 1,000 (296 to 837) | RR 0.87 (0.52 to 1.47) | 155 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 Antibiotics included Cotrimoxazole and Clarithromycin |

| Failure to achieve clinical response Follow‐up: 10‐14 weeks |

492 per 1,000 | 379 per 1,000 (315 to 458) | RR 0.77 (0.64 to 0.93) | 617 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Clinical response was defined as a reduction in CDAI score of 100 points and/or a 50% or greater reduction in perianal fistulas Antibiotics included Ciprofloxacin and Rifaximin |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 6‐52 weeks |

451 per 1,000 | 392 per 1,000 (338 to 460) | RR 0.87 (0.75 to 1.02) | 852 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Adverse events included gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory tract infection, abscess formation, headache and paraesthesia Antibiotics included Cotrimoxazole, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin, Clarithromycin, and Rifaximin |

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 6‐52 weeks |

7 per 1,000 | 12 per 1,000 (2 to 70) | RR 1.70 (0.29 to 10.01) | 520 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4 | Serious adverse events were not well described in the studies. Reported serious adverse events included one scrotal edema and one death Antibiotics included Rifaximin, Ciprofloxacin and Metronidazole |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 6‐52 weeks |

125 per 1,000 | 107 per 1,000 (71 to 161) | RR 0.86 (0.57 to 1.29) | 858 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | Adverse events leading to withdrawal included worsening CD, gastrointestinal symptoms,headache, abscess, rash, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, arthropathy and infusion reaction Antibiotics included Cotrimoxazole, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin, Clarithromycin, and Rifaximin |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (78 events)

2 Downgraded one level due to heterogeneity (I2 = 63%)

3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (267 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (8 events)

5 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (89 events)

Summary of findings 2. Antibiotic with anti‐TNF compared to placebo with anti‐TNF for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Antibiotic with anti‐TNF compared to placebo with anti‐TNF for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Antibiotic with anti‐TNF Comparison: Placebo with anti‐TNF | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo with anti‐TNF | Risk with Antibiotic with anti‐TNF | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was reported in one study. We decided to pool this study with the other anti‐TNF study below (failure to achieve clinical response or remission Antibiotics included Ciprofloxacin |

||||

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to achieve clinical response or remission Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

365 per 1,000 | 208 per 1,000 (106 to 402) | RR 0.57 (0.29 to 1.10) | 100 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Clinical response was defined as a 50% reduction in perianal fistulas. Remission was defined as a closure of fistulas Antibiotics included Ciprofloxacin |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

827 per 1,000 | 769 per 1,000 (628 to 926) | RR 0.93 (0.76 to 1.12) | 100 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Adverse events included nausea, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infections, fatigue and headache Antibiotics included Ciprofloxacin |

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

77 per 1,000 | 63 per 1,000 (15 to 265) | RR 0.82 (0.19 to 3.45) | 100 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Adverse events leading to withdrawal included gastrointestinal symptoms, transfusion reaction and herpes simplex virus infection Antibiotics included Ciprofloxacin |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded one level due to sparse data (80 events)

2 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (29 events)

3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (7 events)

Ciprofloxacin versus placebo

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 10 or 12

Two placebo‐controlled trials involving a total of 65 patients reported on the proportion of patients who failed to enter clinical remission at week 10 or 12 (Arnold 2002; Thia 2009). Forty‐five per cent (17/38) of patients who received ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) failed to achieve clinical remission compared with 74% (20/27) of patients assigned to placebo (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.92). No heterogeneity was detected for this comparison (I² = 31%). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 3).

1. Ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Ciprofloxacin compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Ciprofloxacin Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Ciprofloxacin | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up:10‐12 weeks |

741 per 1,000 | 489 per 1,000 (311 to 770) | RR 0.66 (0.42 to 1.04) | 65 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

842 per 1,000 | 320 per 1,000 (185 to 573) |

RR 0.38 (0.22 to 0.68) |

47 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to have clinical response Follow‐up: 10 weeks |

875 per 1,000 | 403 per 1,000 (175 to 893) |

RR 0.46 (0.20 to 1.02) |

18 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Clinical response was defined as at least a 50% reduction in baseline draining fistulas |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 10‐24 weeks |

407 per 1,000 | 407 per 1,000 (232 to 717) | RR 1.00 (0.57 to 1.76) | 65 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 | Adverse events included upper respiratory tract infection, abscess, open fistula, arthralgias and unpleasant taste/sore mouth |

| Serious adverse events | 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) |

not estimable | 18 (1 RCT) | No serious adverse events were observed | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 10‐24 weeks |

148 per 1,000 | 50 per 1,000 (10 to 247) | RR 0.34 (0.07 to 1.67) | 65 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | Withdrawals were due to worsening Crohn's disease |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (37 events)

2 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (25 events)

3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (11 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (26 events)

5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (6 events)

Failure to maintain clinical remission at week 24

One study (Arnold 2002, N = 48) reported on failure to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks. Thirty‐two per cent (9/28) of patients receiving ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) relapsed at 24 weeks compared with 84% (16/19) of patients assigned to placebo (RR 0.38. 95% CI 0.22 to 0.68) (Arnold 2002). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 3).

Failure to have a clinical response at week 10

One study (Thia 2009) evaluated failure to achieve clinical response at week 10. Forty per cent (4/10) of patients assigned to ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) failed to have a clinical response at week 10 compared with 88% (7/8) of placebo patients (RR 0.46. 95% CI 0.20 to 1.02). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data ( See Table 3).

Adverse events

Two studies that enrolled a total of 38 patients provided data on the proportion of patients with AEs (Arnold 2002; Thia 2009). Thirty‐nine per cent (15/38) of patients receiving ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) experienced an AEcompared with 41% (11/27) of placebo patients (RR 1.0, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.76). No heterogeneity was detected for this comparison (I² = 0%). The GRADE analysis indicated that the certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Summary of findings table 1). AEs in the ciprofloxacin group included Clostridium difficile infection, upper respiratory tract infection and abscess or open fistula. AEs in the placebo group included arthralgias, unpleasant taste/sore mouth and upper respiratory tract infections.

Serious adverse events

No patients in Thia 2009 reported serious SAEs. Arnold 2002 did not report on SAEs.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Two studies (Arnold 2002; Thia 2009; N = 65) provided data on the proportion of patients who withdrew due to AEs. Seven per cent (2/38) of ciprofloxacin participants withdrew due to an AEcompared to 15% (4/27) placebo participants (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.67). The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was rated as low due very sparse data (SeeTable 3). Patients in both ciprofloxacin and placebo groups withdrew due to flare of disease.

Rifaximin versus placebo

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 12 or 14

Two placebo‐controlled trials enrolling a total of 489 patients reported on the proportion of patients who failed to enter clinical remission at week 12 or 14 (Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012). A total of 48% (174/360) of patients receiving rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily) failed to achieve remission compared with 60% (77/129) of those patients who received placebo (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.98). No heterogeneity was detected (I² = 0%). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (See Table 4).

2. Rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily) compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Rifaximin compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Rifaximin Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Rifaximin | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up 12‐14 weeks |

597 per 1,000 | 489 per 1,000 (412 to 585) |

RR 0.82 (0.69 to 0.98) |

489 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to have clinical response Follow‐up: 12‐14 weeks |

519 per 1,000 | 426 per 1,000 (348 to 525) | RR 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) | 489 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | Clinical response was defined as reduction of CDAI ≥ 70 points and reduction in CDAI score of 100 points |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12‐14 weeks |

473 per 1,000 | 392 per 1,000 (312 to 492) | RR 0.83 (0.66 to 1.04) | 489 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Adverse events included gastrointestinal disorders, infections, headache and ocular disorders |

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 12‐14 weeks |

8 per 1,000 | 9 per 1,000 (2 to 35) | RR 1.11 (0.27 to 4.54) | 489 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 | The types of serious adverse events were not described by study authors |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 12 ‐14 weeks |

62 per 1,000 | 78 per 1,000 (37 to 164) | RR 1.25 (0.59 to 2.64) | 489 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | The adverse events leading to withdrawal were not described by study authors |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (251 events)

2Downgraded one level due to sparse data (221 events)

3 Downgraded one level due to sparse data (201 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (7 events)

5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (37 events)

Planned subgroup analyses performed according to dose demonstrated 51% (67/131) of patients who received rifaximin 1600 mg once‐daily (OD) failed to enter clinical remission at week 12 or 14 compared with 62% (29/47) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.93). Forty per cent (51/126) of patients who received rifaximin 800 mg OD failed to enter clinical remission at week 12 or 14 compared with 60% (29/48) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.12) and 54% (56/103) of patients who received 2400 mg OD failed to enter clinical remission at week 12 or 14 compared with 56% (19/34)of placebo (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.38). For dose, the test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 2.40, df = 2, P = 0.30, I² = 16.7%).

Failure to have a clinical response at weeks 12 or 14

In these same studies (Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012), 43% (154/360) patients receiving rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily)failed to respond at weeks 12 or 14 compared with 52% (67/129) of patients receiving placebo (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.01). No heterogeneity was seen for this comparison (I² = 0%). The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (See Table 4).

Planned subgroup analyses performed according to dose demonstrated a difference between the rifaximin 1600 mg once‐daily (OD) and placebo. However, no difference between the rifaximin 800 mg OD or 2400 mg OD group and the placebo group was observed. In patients who received rifaximin 800 mg daily, 46% (60/131) of patients treated with rifaximin failed to achieve response at 12 or 14 weeks compared with 51% (24/47) of patients treated with placebo (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.28). No heterogeneity was seen for this comparison (I² = 0%). In patients who received 1600 mg of rifaximin daily, 32% (41/126) of patients on the study drug failed to respond, compared with 52% (25/48) of patients receiving placebo (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.91). No heterogeneity was seen in this comparison (I² = 0%). In patients who received 2400 mg of rifaximin daily, 51% (53/103) of patients failed to respond compared with 53% (18/34) in the placebo group (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.40). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 3.16, df = 2, P = 0.30, I² = 36.7%).

Adverse events

In total, 39% (140/360) patients who received rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily) reported an AE compared to 47% (61/129) of those who received placebo (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.04). No heterogeneity was seen for this comparison (I² = 0%). The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (See Table 4). AEs in the rifaximin group included gastrointestinal disorders, headache and skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders. AEs in the placebo group included gastrointestinal disorders, ocular disorders and headache.

Subgroup analysis by dose showed 34% (45/131) of patients taking rifaximin 800 mg had AEs compared with 49% (23/47) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.05). Forty per cent (50/126) of patients taking rifaximin 1600 mg had AEs compared with 48% (23/48) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.21). Forty four per cent (45/103) of patients taking rifaximin 2400 mg had AEs compared with 44% (15/34) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.53) (Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 1.20, df = 2, P = 0.55, I² = 0%).

Serious adverse events

Two per cent (6/360) of patients who received rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily) reported a SAE compared with 1% (1/129) of patients in the placebo group (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.27 to 4.54). No heterogeneity was seen in this comparison (I² = 0%). The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 4). The one SAE reported in Prantera 2006 included scrotal edema. SAEs were not well described in Prantera 2012. However, one death was reported in the rifaximin group. The investigators felt that this death was not related to treatment,

Subgroup analysis by dose showed 2% (2/131) of patients taking rifaximin 800 mg experienced SAEs compared with 0% (0/47) of patients who received placebo (RR 1.64, 95% CI 0.08 to 33.26). Two per cent (2/126) of patients taking rifaximin 1600 mg had a SAEs compared with 0% (0/48) of patients who received placebo (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.14 to 12.08). Two per cent (2/103) of patients taking rifaximin 2400 mg experienced SAEss compared with 3% (1/34) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.06 to 7.05) (Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.27, df = 2, P = 0.87, I² = 0%).

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Eight per cent (29/360) of patients receiving rifaximin (800 mg to 2400 mg daily) withdrew from studies due to AEs, compared to 6% (8/129) of patients receiving placebo (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.64). No heterogeneity was seen in this comparison (I² = 0%). The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 4). A summary AEs that led to withdrawal was not reported by study authors.

Subgroup analysis by dose showed 4% (5/131) of patients taking rifaximin 800 mg withdrew due to AEs compared with 6% (3/47) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.16). Six per cent (8/126) of patients taking rifaximin 1600 mg withdrew due to AEs compared with 6% (3/48) of patients who received placebo (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.30 to 3.83). Sixteen per cent (16/103) of patients taking rifaximin 2400 mg withdrew due to AEs compared with 6% (2/34) of patients who received placebo (RR 2.64, 95% CI 0.64 to 10.90)(Prantera 2006; Prantera 2012). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 2.42, df = 2, P = 0.30, I² = 17.5%).

Metronidazole versus placebo

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 6 or 10

Two placebo controlled trials (Ambrose 1985; Thia 2009), that comprised a total of 50 patients, reported on the number of patients who failed to enter clinical remission at weeks 6 or 10. One of these studies had failure of clinical remission as a primary end point (Ambrose 1985) and another had failure of clinical remission as a secondary end point (Thia 2009) at weeks 6 or 10. Two therapeutic doses of metronidazole (400 mg to 500 mg twice daily) were used in these studies. Sixty per cent (15/25) of patients who received metronidazole failed to enter clinical remission at week 6 or 10 compared with 68% (17/25) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.33). No heterogeneity was seen for this comparison (I² = 45%). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for the this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 5).

3. Metronidazole (400 mg to 500 mg twice daily) compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Metronidazole compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Metronidazole Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Metronidazole | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up: 6‐10 weeks |

680 per 1,000 | 619 per 1,000 (422 to 904) | RR 0.91 (0.62 to 1.33) | 50 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Clinical remission was defined as closure of all open actively draining fistulas at baseline |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to have clinical response Follow‐up: 10 weeks |

875 per 1,000 | 604 per 1,000 (341 to 1,000) |

RR 0.69 (0.39 to 1.21) |

18 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Clinical response was defined as at least a 50% reduction in baseline draining fistulas |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 6‐10 weeks |

274 per 1,000 | 233 per 1,000 (88 to 633) | RR 0.85 (0.32 to 2.31) | 149 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 | Adverse events include gastrointestinal upset, abscess formation and arthropathy.paraesthesias and sore mouth. |

| Serious adverse events | 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 15 (1 RCT) | No serious adverse events were observed | |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 6‐10 weeks |

148 per 1,000 | 114 per 1,000 (53 to 248) | RR 0.77 (0.36 to 1.68) | 149 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | Withdrawal due to adverse events was most often due to headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, abscess formation, rash and arthralgia |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (32 events)

2 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (13 events)

3Downgraded one level due to serious inconsistency (I2 = 71%)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (33 events)

5 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (19 events)

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 16

An additional study evaluated failure to achieve clinical remission at week 16 in 99 patients (Sutherland 1991). Remission in this case was defined by improvement in the patients Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score to less than 150. The pooled analysis showed no difference between metronidazole (400 mg to 500 mg twice daily) and placebo for induction of clinical remission. Sixty‐eight per cent (43/63) of patients receiving metronidazole failed to achieve remission at week 16 compared with 67% (24/36) of patients receiving placebo (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.36). No heterogeneity was seen for this comparison (I² = 0%).

Planned subgroup analysis according to dose showed no difference in clinical remission rates. Two different doses of metronidazole were used in this study. In the group that received 10 mg/kg of metronidazole, 64% (21/33) of patients failed to achieve remission at week 16, compared with 67% (12/18) in the group that received placebo (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.45). In group that received 20 mg/kg of metronidazole, 73% (22/30) of patients failed to achieve remission compared with 67% (12/18) of patients assigned to placebo (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.63). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.24, df = 1, P = 0.63, I² = 0%).

Failure to have clinical response at week 10

Thia 2009 evaluated failure to achieve clinical response at 10 weeks in 19 patients. Sixty per cent (6/10) of patients assigned to metronidazole failed to achieve clinical response at week 10 compared with 88% (7/8) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.21). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 5).

Adverse events

Eighteen per cent (16/87) of metronidazole patients reported AEs compared to 27% (17/62) of those assigned to placebo (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.33). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for AEs was very low due to very serious inconsistency and very sparse data (See Summary of findings table 3). AEs in the metronidazole group included gastrointestinal upset, abscess formation and arthropathy. AEs in the placebo group included gastrointestinal upset, paraesthesias and sore mouth.

Serious adverse events

Thia 2009 reported no SAEs.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Eleven per cent (10/88) of patients assigned to metronidazole withdrew from the study due to AEscompared with 15% (9/61) of patients on placebo (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.68) (Ambrose 1985; Sutherland 1991; Thia 2009). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for withdrawal due to AEs was low due to very sparse data (See Table 5). Withdrawal due to AEs in the metronidazole group was most often due to headache, gastrointestinal symptoms and abscess formation and in the placebo group was most commonly due to rash and arthralgia.

Clarithromycin versus placebo

Failure to enter clinical remission at 12 weeks

One study that evaluated a total of 41 patients used clarithromycin as an induction agent (Lieper 2008). The primary end point of this study was clinical remission at 12 weeks as defined by CDAI ≤ 150. Eighty‐four per cent (16/19) of patients who received clarithromycin (1 g daily) failed to enter clinical remission at 12 weeks compared to 81% (18/22) of patients assigned to receive placebo (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.36). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 6).

4. Clarithromycin (1 g/day) compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Clarithromycin compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Clarithromycin Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Clarithromycin | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up:12 weeks |

818 per 1,000 | 843 per 1,000 (638 to 1,000) | RR 1.03 (0.78 to 1.36) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to have clinical response Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

818 per 1,000 | 736 per 1,000 (532 to 1,000) |

RR 0.90 (0.65 to 1.26) |

41 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Clinical response was defined by CDAI reduction by ≥ 70 from baseline |

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

45 per 1,000 | 210 per 1,000 (26 to 1,000) | RR 4.63 (0.57 to 37.96) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Adverse events included gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

500 per 1,000 | 370 per 1,000 (180 to 760) | RR 0.74 (0.36 to 1.52) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 | Withdrawal due to adverse events was most often due to gastrointestinal symptoms |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (34 events)

2 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (32 events)

3Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (5 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (18 events)

Failure to have clinical response at 12 weeks

Seventy‐four per cent (14/19) of clarithromycin (1 g daily) patients failed to have a clinical response at week 12, compared with 82% (18/22) of patients assigned to placebo (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.26) (Lieper 2008).The certainty of evidence for this outcome was rated as low due to very sparse data (See Table 6).

Adverse events

Twenty‐one per cent (4/19) of patients who received clarithromycin (1 g daily) reported an AE compared with 5% (1/22) of patients in the placebo group (RR 4.63, 95% CI 0.57 to 37.96) (Lieper 2008). Most common AEs seen in both clarithromycin and placebo group were gastrointestinal symptoms..A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 6).

Serious adverse events

Lieper 2008 did not report on this outcome.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Thirty‐seven per cent (7/19) of patients who received 1 g daily clarithromycin withdrew due to AEs, compared to 50% (11/22) of those in the placebo group (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.52) (Lieper 2008). The most common reason for withdrawal due to AEs seen in both the clarithromycin and placebo groups was gastrointestinal symptoms. The overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 6).

Cotrimoxazole versus placebo

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 12

One study that evaluated 33 patients assessed the efficacy of cotrimoxazole (960 mg twice daily) induction therapy (Ambrose 1985). The primary end point of this study was an improvement in a clinical assessment score created by the Authors at week 12. This score was defined by the authors. Sixteen patients were randomised to the cotrimoxazole arm of this study and 17 received placebo. Sixty‐nine per cent (11/16) of patients who received cotrimoxazole failed to enter clinical remission at 12 weeks compared to 59% (10/17) of patients assigned to placebo (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.96). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 7).

5. Cotrimoxazole (960 mg twice daily) compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Cotrimoxazole compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Cotrimoxazole Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Cotrimoxazole | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up: week 12 |

588 per 1,000 | 688 per 1,000 (412 to 1,000) | RR 1.17 (0.70 to 1.96) | 33 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Clinical remission was defined as improvement in clinical assessment and laboratory indices |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to have a clinical response | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

176 per 1,000 | 125 per 1,000 (25 to 653) | RR 0.71 (0.14 to 3.70) | 33 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Adverse events included nausea, vomiting and arthropathy |

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

59 per 1,000 | 125 per 1,000 (12 to 1,000) | RR 2.13 (0.21 to 21.22) | 33 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Withdrawal due to adverse events was most often due to nausea, vomiting and arthropathy |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (21 events)

2 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (5 events)

3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (3 events)

Adverse events

One per cent (2/16) of patients in the cotrimoxazole (960 mg twice daily) group reported an AE compared with 18% (3/17) of patients who received placebo (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.14 to 3.70) (Ambrose 1985). AEs in cotrimoxazole group included nausea, vomiting and arthropathy. AEs in the placebo group were not mentioned by study authors. The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome is low due to very sparse data (See Table 7).

Serious adverse events

Ambrose 1985 did not report on this outcome.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Thirteen per cent (2/16) of patients receiving 960 mg twice daily cotrimoxazole withdrew due to AEs, compared to 6% (1/17) of patients in the placebo group (RR 2.13, 95% CI 0.21 to 21.22) (Ambrose 1985). AEs leading to withdrawal in the cotrimoxazole group included nausea, vomiting and arthropathy. AEs leading to study withdrawal in the placebo group were not described by the study authors.The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 7).

Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole versus methylprednisolone

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 12

Prantera 1996 (N=41) compared a combination of ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (250 mg four times daily) to methylprednisolone (0.7‐1 mg/kg daily) induction therapy. The primary end point of this study was clinical remission at 12 weeks as defined by CDAI ≤ 150. Fifty‐five per cent (12/22) of patients in the antibiotic group failed to enter clinical remission at week 12, compared with 37% (7/19) of patients receiving methylprednisolone (RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.99). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 8).

6. Ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (250 mg four times daily) compared to methylprednisolone (0.7‐1 mg/kg daily) for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole compared to methylprednisone for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole Comparison: Methylprednisone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with methylprednisone | Risk with Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

368 per 1,000 | 545 per 1,000 (269 to 1,000) | RR 1.48 (0.73 to 2.99) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1 2 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 52 weeks |

684 per 1,000 | 773 per 1,000 (527 to 1,000) | RR 1.13 (0.77 to 1.65) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 3 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to have clinical response | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to maintain endoscopic remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12‐52 weeks |

105 per 1,000 | 273 per 1,000 (62 to 1,000) | RR 2.59 (0.59 to 11.36) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Adverse events include nausea, metallic taste, reflux symptoms, Cushingoid facies and acne |

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 12‐52 weeks |

105 per 1,000 | 273 per 1,000 (62 to 1,000) | RR 2.59 (0.59 to 11.36) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 | Withdrawal due to adverse events was most often due to nausea, vomiting, reflux symptoms, hypertension, elevated amylase, acne and tremor |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (19 events)

2 Downgraded one level due to high risk bias (blinding)

3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (30 events)

4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (8 events)

Failure to maintain clinical remission at week 52

Seventy‐seven per cent (17/22) of patients assigned to antibiotics failed to maintain clinical remission at week 52 compared to 68% (13/19) of patients who received methylprednisolone (0.7‐1 mg/kg daily) (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.65) (Prantera 1996). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 8)

Adverse events

Twenty‐seven per cent (6/22) of patients who received combination antibiotic therapy reported an AE compared with 11%(2/19) of patients who received methylprednisolone (RR 2.59, 95% CI 0.59 to 11.36) (Prantera 1996). AEs in patients receiving the combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole included nausea, metallic taste and reflux symptoms. AEs in steroid group included Cushingoid facies, acne and reflux. The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 8).

Serious adverse events

Prantera 1996 did not report on SAES.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Twenty‐seven per cent (6/22) of patients receiving antibiotics withdrew from the study due to AEs, compared with 11% (2/19) of patients on steroid (RR 2.59, 95% CI 0.59 to 11.36) (Prantera 1996). AEs leading to withdrawal in patients receiving ciprofloxacin and metronidazole included nausea, vomiting and reflux symptoms. AEs in steroid group resulting in withdrawal included hypertension, elevated amylase, acne and tremor. The overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was low due to very sparse data (See Table 8).

Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole and budesonide versus placebo and budesonide

Failure to enter clinical remission at week 8

One study (N = 134) compared a combination of ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (500 mg twice daily) to placebo (Steinhart 2002). Both groups received oral budesonide (9 mg daily) induction therapy. The primary end point of this study was clinical remission at eight weeks as defined by CDAI < 150. Sixty‐eight per cent (45/66) of patients in the antibiotic group failed to achieve clinical remission at week 12, compared with 62% (43/69) of patients who received placebo (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.38). A GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (See Table 9).

7. Ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) and metronidazole (500 mg twice daily) and budesonide (9 mg/daily) compared to placebo with budesonide (9 mg/daily) for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole and budesonide compared to placebo with budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with active CD Setting: Outpatient Intervention: Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole | |||||

| Failure to enter clinical remission Follow‐up: 8 weeks |

632 per 1,000 | 683 per 1,000 (531 to 873) | RR 1.08 (0.84 to 1.38) | 134 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Clinical remission was defined as CDAI ≤150 |

| Failure to maintain clinical remission | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||

| Failure to have clinical response | Not reported | This outcome was not reported | ||||