Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the Cochrane Review previously published in 2017.

Absence seizures (AS) are brief epileptic seizures which present in childhood and adolescence. Depending on clinical features and electroencephalogram (EEG) findings they are divided into typical, atypical absences, and absences with special features. Typical absences are characterised by sudden loss of awareness and an EEG typically shows generalised spike wave discharges at three cycles per second. Ethosuximide, valproate and lamotrigine are currently used to treat absence seizures. This review aims to determine the best choice of antiepileptic drug for children and adolescents with AS.

Objectives

To review the evidence for the effects of ethosuximide, valproate and lamotrigine as treatments for children and adolescents with absence seizures (AS), when compared with placebo or each other.

Search methods

For the latest update we searched the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web, 29 May 2018), which includes the Cochrane Epilepsy Group's Specialized Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 29 May 2018), ClinicalTrials.gov (29 May 2018) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP, 29 May 2018). Previously we searched Embase (1988 to March 2005) and SCOPUS (1823 to 31 March 2014), but this is no longer necessary because randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs in Embase and SCOPUS are now included in CENTRAL. No language restrictions were imposed. In addition, we contacted Sanofi Winthrop, Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) and Parke Davis (now Pfizer), manufacturers of sodium valproate, lamotrigine and ethosuximide respectively.

Selection criteria

Randomised parallel group monotherapy or add‐on trials which include a comparison of any of the following in children or adolescents with AS: ethosuximide, sodium valproate, lamotrigine, or placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Outcome measures were: (1) proportion of individuals seizure free at one, three, six, 12 and 18 months post randomisation; (2) people with a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency; (3) normalisation of EEG and/or negative hyperventilation test; and (4) adverse effects. Data were independently extracted by two review authors. Results are presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). We used GRADE quality assessment criteria to evaluate the certainty of evidence derived from all included studies.

Main results

On the basis of our selection criteria, we included no new studies in the present review. Eight small trials (total number of participants: 691) were included from the earlier review. Six of them were of poor methodological quality (unclear or high risk of bias) and seven recruited less than 50 participants. There are no placebo‐controlled trials for ethosuximide or valproate, and hence, no evidence from RCTs to support a specific effect on AS for either of these two drugs. Due to the differing methodologies used in the trials comparing ethosuximide, lamotrigine and valproate, we thought it inappropriate to undertake a meta‐analysis. One large randomised, parallel double‐blind controlled trial comparing ethosuximide, lamotrigine and sodium valproate in 453 children with newly diagnosed childhood absence epilepsy found that at 12 months, the freedom‐from‐failure rates for ethosuximide and valproic acid were similar and were higher than the rate for lamotrigine. The frequency of treatment failures due to lack of seizure control (P < 0.001) and intolerable adverse events (P < 0.037) was significantly different among the treatment groups, with the largest proportion of lack of seizure control in the lamotrigine cohort, and the largest proportion of adverse events in the valproic acid group. Overall, this large study demonstrates the superior effectiveness of ethosuximide and valproic acid compared to lamotrigine as initial monotherapy aimed to control seizures without intolerable adverse effects in children with childhood absence epilepsy. The risk of bias for this study was low. We rated the overall certainty of the evidence available from the included studies to be moderate or high.

Authors' conclusions

Since the last version of this review was published, we have found no new studies. Hence, the conclusions remain the same as the previous update. With regards to both efficacy and tolerability, ethosuximide represents the optimal initial empirical monotherapy for children and adolescents with AS. However, if absence and generalised tonic‐clonic seizures coexist, valproate should be preferred, as ethosuximide is probably inefficacious on tonic‐clonic seizures.

Plain language summary

Ethosuximide, sodium valproate or lamotrigine for absence seizures in children and adolescents

Background

Epilepsy is a disorder where seizures are caused by abnormal electrical discharges from the brain. Absence epilepsy involves seizures that cause a sudden loss of awareness. It often starts in childhood or adolescence. Three antiepileptic drugs are often used for absence epilepsy: valproate, ethosuximide and lamotrigine.

This review aims to determine which of these three antiepileptic drugs is the best choice for the treatment of absence seizures in children and adolescents.

Results

The review found some evidence (based on eight small trials) that individuals taking lamotrigine are more likely to be seizure free than those using placebos. The review found robust evidence that patients taking ethosuximide or valproate are more likely to be seizure free than those using lamotrigine. However, because of the lower risk of adverse effects, the use of ethosuximide is preferred over valproate in patients with absence childhood epilepsy.

With regards to both efficacy and tolerability, ethosuximide represents the optimal initial empirical monotherapy for children and adolescents with absence seizures.

The evidence is current to May 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

This is an updated version of the Cochrane Review previously published in 2017, Issue 2 of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Brigo 2017).

Description of the condition

Absence seizures (AS) are brief epileptic seizures characterised by sudden loss of awareness. Depending on clinical features and electroencephalogram (EEG) findings, they are divided into typical AS, atypical AS, and AS with special features (Berg 2010; Tenney 2013). About 10% of seizures in children with epilepsy are typical AS. Typical AS are associated with an EEG showing regular generalised and symmetrical spike and slow wave complexes at a frequency of three cycles per second at the same time as the absence. Childhood seizure disorders are classified into syndromes, which take into account seizure types, age and EEG changes. Typical AS may be the only seizure type experienced by a child and this then constitutes either an epileptic syndrome called childhood absence epilepsy or juvenile absence epilepsy. However, AS may also be only one of multiple types of seizures, for example in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy where myoclonic and tonic‐clonic seizures occur as well as AS. Atypical AS are characterised by less abrupt onset and offset, longer duration, changes in muscular tone, and variable impairment of consciousness; they are associated with interictal 1.5‐2.5 Hz irregular, asymmetrical spike and wave complexes on the EEG, and with diffuse, irregular slow spike and wave as ictal pattern. The 2010 revised International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Report on Terminology and Classification has recently recognised two additional types of AS, which are associated with special features: myoclonic AS and eyelid myoclonia with absence (EMA) (Berg 2010). Seizures occurring in EMA are clinically associated with jerkings of the eyelids with upward eye‐deviation, which are usually triggered by eye closure; the ictal EEG shows 3‐6 Hz generalised polyspike and wave complexes, sometimes associated with occipital paroxysmal discharges.

Description of the intervention

Ethosuximide, valproic acid and lamotrigine are drugs commonly used for the treatment of children with AS. Ethosuximide was introduced into clinical practice in 1958, and is currently indicated only for the treatment of generalised As; gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhoea) occur in 4% to 29% of patients receiving ethosuximide (Shorvon 2010). Valproic acid is one of the most commonly prescribed antiepileptic drugs in the world and, thanks to its wide spectrum of activity, represents the drug of first choice for many types of epilepsy, including idiopathic generalised epilepsy; its risk of teratogenicity greatly limits its use in women of child‐bearing age (Shorvon 2010). Lamotrigine is a broad‐spectrum antiepileptic drug, which is used as add‐on or monotherapy of partial seizures and generalised seizures; it is generally effective and well tolerated, despite the risk of rash which can sometimes be severe, and complicated pharmacokinetics (Shorvon 2010).

How the intervention might work

The antiepileptic properties of ethosuximide and its efficacy against AS are due to its voltage ‐ dependent blockade of low‐threshold T‐ type calcium currents in the thalamus (Shorvon 2010). The mechanisms of action of valproate are various and not yet fully elucidated; it enhances inhibitory neurotransmission (mainly mediated by gamma‐Aminobutyric acid and glutamic acid), but it also reduces conductance at the voltage ‐ dependent sodium channel, as well as calcium (T) and potassium conductance (the latter mechanism may explain its efficacy against AS) (Shorvon 2010). Similar to carbamazepine or phenytoin, lamotrigine exerts its antiepileptic activity blocking voltage – dependent sodium channel conductance (Shorvon 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

Non‐systematic reviews have suggested that ethosuximide and sodium valproate are equally effective (Duncan 1995). Valproate is considered the drug of choice in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (Chadwick 1987; Christe 1989), although there is little in the way of evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to support this. Lamotrigine used to be considered a second‐line drug, reserved for intractable AS (Duncan 1995), but its use has increased with time. It is especially valued in situations where sodium valproate leads to weight gain and also for women of childbearing age. The latter is due to fears of a higher rate of fetal abnormalities in pregnancies exposed to valproate (Moore 2000). Preliminary studies suggested that lamotrigine may become the first‐line drug in AS (Buoni 1999). This review aims to determine the best choice of anticonvulsant for children and adolescents with AS by reviewing the information available from RCTs.

Objectives

To review the evidence for the effects of ethosuximide, valproate and lamotrigine as treatments for children and adolescents with typical absence seizures (AS), when compared with placebo or each other.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised parallel group monotherapy or add‐on trials which include a comparison of any of the following in children or adolescents with typical AS: ethosuximide; sodium valproate; lamotrigine and placebo.

The studies should have used either adequate or quasi‐randomised methods (e.g. allocation by day of week).

Blinded and unblinded studies.

Types of participants

Children or adolescents (up to 16 years of age) with typical AS.

Types of interventions

Sodium valproate, ethosuximide or lamotrigine as monotherapy or add‐on treatment. These drugs may be compared with placebo or with one another.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of participants seizure free at one, three, six, 12 and 18 months after randomisation.

Fifty per cent or greater reduction in the frequency of seizures.

Incidence of adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

Normalisation of electroencephalogram (EEG) and/or negative hyperventilation test.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Searches were run for the original review in March 2003 and subsequent searches were run in March 2005, July 2007, November 2009, August 2011, March 2014, December 2015, and September 2016.

For the latest update we searched:

the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web, 29 May 2018), which includes the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), using the search strategy shown in Appendix 1;

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 29 May 2018) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 2;

ClinicalTrials.gov (29 May 2018) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 3;

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform ICTRP (29 May 2018) using the search strategy shown in Appendix 4.

Previously, we searched Embase (1988 to March 2005). Subsequently, as we no longer had access to Embase, we searched SCOPUS (1823 to 31 March 2014) as a substitute using the search strategy shown in Appendix 5. These databases have not been searched again, because randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in Embase are now included in CENTRAL

There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We contacted Sanofi Winthrop, Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) and Parke Davis (now Pfizer), manufacturers of sodium valproate, lamotrigine and ethosuximide, respectively. We also reviewed any references of identified studies and retrieved any relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (FB, SI, SL) independently assessed trials for inclusion and disagreements were resolved by discussion. The same review authors independently extracted data from trial reports.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following data from the studies that met our inclusion criteria:

study design;

method of randomisation concealment;

method of blinding;

whether any participants had been excluded from reported analyses;

duration of treatment;

outcome measures;

participant data (total number of individuals allocated to each treatment group, age of participants, naive participants versus selected groups, individuals with other types of seizures co‐existing with typical absence seizures);

results (success rate and adverse effects).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FB and SL) independently assessed risk of bias for each included trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011), and considering sequence generation, concealment of allocation, methods of blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other types of bias. A third party resolved disagreements in the assessment of the level of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

The data for our chosen outcomes are dichotomous and our preferred outcome statistic was the risk ratio (RR).

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to deal with any unit of analysis issues according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Due to the small number of included studies no best‐case or worst‐case analysis was performed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by evaluating similarities and differences in the methodologies and outcomes measured in the included studies and by visually inspecting forest plots. We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity using the Chi² test and I² statistic (Higgins 2011) as follows: 0% to 40% might not be important, 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% indicating considerable heterogeneity. We used a fixed‐effect model if we did not find statistically significant heterogeneity between the included studies. Otherwise, we planned to use a random‐effects model. However, despite our primary intention, due to insufficient information on outcomes and too high clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we were unable to perform any meta‐analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We sought all protocols from study authors to identify any discrepancies between protocol and trial methodology.

Data synthesis

Provided we thought it clinically appropriate, and no important heterogeneity was found, we planned to summarise results in a meta‐analysis. However, because of the methodological problems outlined below it was not possible to perform meta‐analysis of the data from the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The large difference in the length of follow‐up and timing of analysis was a particular problem. Further research could allow results to be pooled, leading to a quantitative rather than a qualitative summary of results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not carry out any subgroup analysis or formal investigation of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

If we had found trial methodologies to be sufficiently distinct, we would have conducted sensitivity analyses to identify which factor(s) could have influenced the degree of heterogeneity.

'Summary of findings' tables and quality of the evidence (GRADE)

For the 2018 update, we presented the results concerning the outcomes of interest for which data were available from included studies in 'Summary of findings' tables, and we used GRADE (Guyatt 2008) quality assessment criteria to evaluate the certainty of evidence derived from the studies included in this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

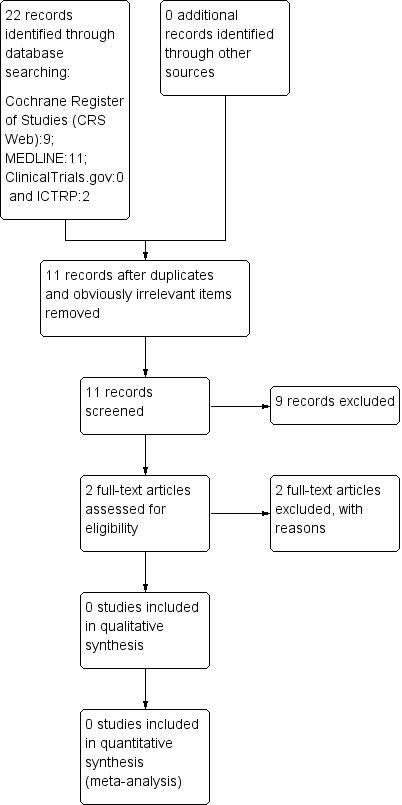

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram (results refer only to the updated version of the review). The previous versions of the review (Posner 2003; Posner 2005a; Posner 2005b; Brigo 2017) included eight studies.

The previous versions of the review (Posner 2003; Posner 2005a; Posner 2005b; Brigo 2017) included eight studies.

The updated search strategy described above yielded 22 results (nine Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web), 11 MEDLINE, zero ClinicalTrials.gov, and two ICTRP). After removing eight duplicates and three obviously irrelevant items, we assessed 11 articles for possible inclusion. Two studies were initially considered for possible inclusion (Glauser 2017; Shinnar 2017). However, both studies were eventually excluded, as they provided further data on a randomised controlled trial (RCT) which had been included in the previous versions of the review (Glauser 2013a); the additional data provided were irrelevant with regards to the aim of the present review. Since the last version of this review, we have found no new studies. Here below we provide details of the studies included in the previous versions of this review.

Included studies

Callaghan 1982 This was a randomised, parallel open study, which compared monotherapy with ethosuximide and sodium valproate. Ethosuximide was initially given at 250 mg/day and, whenever required, incremented by 250 mg to a maximum of 1500 mg/day. Valproate was started at 400 mg/day and, if deemed necessary, gradually incremented by 200 mg up to 2400 mg/day. Participants (total 28) had typical absence seizures (AS), were between four and 15 years, and were previously untreated. Follow‐up ranged from 18 months to four years. The report acknowledged support from Warner‐Lambert Pharmaceuticals, manufacturers of ethosuximide.

Sato 1982 This study used a complex response conditional design and recruited drug‐naive participants as well as participants already on treatment, with a total of 45 participants recruited. In the first phase of this trial; participants were randomised to receive either valproate (and placebo) or ethosuximide (and placebo) and followed up for six weeks. Participants responding to randomised treatment continued with the randomised drug for a further six weeks. Responders included previously untreated participants who became seizure free and participants who had been previously treated and had an 80% or greater reduction in AS frequency. Non‐responders and those with adverse effects were crossed over to the alternative treatment and followed up for a further six weeks. The age range of participants was three to 18 years. Apart from AS, some participants also had other types of seizures. The report does not specify if the AS were typical or atypical. Some of the participants were drug naive and some drug resistant. Participants of the study were selected from those who attended the epilepsy clinic at the Clinical Research Center, University of Virginia Hospital, USA. The work was supported by a contract from the Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS).

Martinovic 1983 This was a parallel, open‐design study comparing ethosuximide and sodium valproate. Participants were between five and eight years old with a recent (less than six weeks) onset of seizures. All participants (total 20) had 'simple absences' and were followed up for one to two years. Six individuals did not co‐operate and were therefore not included in the analysis. No information about sponsorship by a pharmaceutical company is given.

Frank 1999 This was a double‐blind study using a 'responder enriched' design. Participants (total 29) had newly diagnosed typical AS and were aged between three to 15 years. Prior to randomisation, all participants received treatment with lamotrigine. After four weeks or more of treatment, participants who were seizure free and had a negative 24‐hour EEG with hyperventilation, were randomised to either continue lamotrigine or to placebo and were followed up for four weeks. This study was sponsored by Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), makers of lamotrigine.

Coppola 2004 This was a randomised, parallel group unblinded study comparing lamotrigine and sodium valproate. All participants (n = 38) were drug naive, aged three to 13 years old with typical As. The follow‐up time was 12 months. The primary outcome measure was total seizure freedom, measured at one, three and 12 months. This study was not sponsored by any commercial organisation.

Basu 2005 Results of this study were published as an abstract. We contacted the main author of this study via email three times (30 October and 4 November 2015, and 7 January 2016) asking for further information; we did not receive a reply. This was a randomised, open‐label, parallel group design comparing sodium valproate with lamotrigine used in monotherapy for treatment of typical AS (diagnosed clinically and by EEG support). Thirty patients were included (males 16; females 14 – age between five and 14 years). Patients with other comorbidities were excluded. Fifteen patients were randomly allocated to receive valproate and 15 to receive lamotrigine. The follow‐up was 12 months. The primary outcome was seizure freedom and no EEG evidence of seizure. Drug dosages were not explicitly reported. The dosages were escalated according to the clinical response, starting from a low dose. Lamotrigine was titrated very slowly at two‐weekly intervals to avoid unwanted side effects (maximum 10 mg/kg/day). After one month of treatment nine patients (60%) receiving valproate and none (0%) receiving lamotrigine were seizure free. After three months, 11 patients (73.3%) in the sodium valproate and eight patients (53.3%) in the lamotrigine group receiving lamotrigine were seizure free. After 12 months, 12 patients (80%) receiving sodium valproate and 10 patients (66.6%) treated with lamotrigine were seizure free (P > 0.05). Minimal adverse events (not explicitly reported) were observed in 26.6% of patients treated with sodium valproate and in 20% of patients receiving lamotrigine. No drop outs were observed. No information on sponsorship by pharmaceutical company was available.

This study (Huang 2009), compared valproate with lamotrigine monotherapy in drug‐naive children (n = 48, six to 10 years) with newly diagnosed childhood AS (typical seizures). Included patients were 17 males and 31 females (no detailed descriptions in each group, respectively). The follow‐up time was 12 months. The outcome measure was total seizure freedom, measured at one, three, six and 12 months. Complete normalisation of EEG with seizure freedom and occurrence of adverse effects were also considered. In the valproate group, sustained release tablets or oral solution were administered twice daily (totally 15 mg/kg per day); in case of persisting seizures after one week, the dose was increased to 20 mg/kg per day, twice daily (maximum dose daily 30 mg/kg). In case of persisting seizures despite a maximum dose of 30 mg/kg within a month, combination with lamotrigine 0.15 mg/kg daily to 2 mg to 5 mg/kg was administrated. In the lamotrigine group, patients received a starting dose of lamotrigine of 0.5 mg/kg daily, administered twice, increased to 0.15 mg/kg per two weeks. The daily maintenance dose was 2 mg to 5 mg/kg, and the maximum daily dose 10 mg/kg. In case of persisting seizures despite a maximum dose within a month, combination with valproate 10 mg/kg daily to 20 mg/kg was administrated. No information on sponsorship by pharmaceutical company was available.

Glauser 2013a This was a randomised, parallel double‐blind controlled trial comparing ethosuximide, lamotrigine and sodium valproate in children with newly diagnosed childhood absence epilepsy. The study designed included also a partial cross‐over to open‐label (at treatment failure only) with subsequent follow‐up: participants reaching a treatment‐failure criterion in the double‐blind treatment phase were given the opportunity to enter into the open‐label phase, during which participants were randomised to one of the two other antiepileptic drugs. Participants (total 453 enrolled) had typical AS, were between seven months and 12 years 11 months, and were previously untreated. Among the 453 patients enrolled, seven were withdrawn, hence 446 participants were included in subsequent effectiveness analyses and 451 participants included in the safety analyses. Follow‐up was up to 12 months. Study drugs were titrated as tolerated in predetermined increments every one to two weeks over 16 weeks. Ethosuximide and valproic acid doses were incremented of 5 mg to 10 mg/kg/day at intervals of two weeks, whilst lamotrigine doses were incremented of 0.3 mg to 0.6 mg/kg/day at intervals of two weeks. The maximal target doses were ethosuximide 60 mg/kg/day or 2000 mg/day (whichever was lower), valproic acid 60 mg/kg/day or 3000 mg/day (whichever was lower), and lamotrigine 12 mg/kg/day or 600 mg/day (whichever was lower). The main effectiveness outcome was the freedom from treatment failure assessed 12 months after randomisation. Freedom from treatment failure was also assessed at 16 to 20 weeks. Treatment failure was defined as failure either due to lack of seizure control, or meeting safety exit criteria, or withdrawal from the study for any other reason.

Risk of bias in included studies

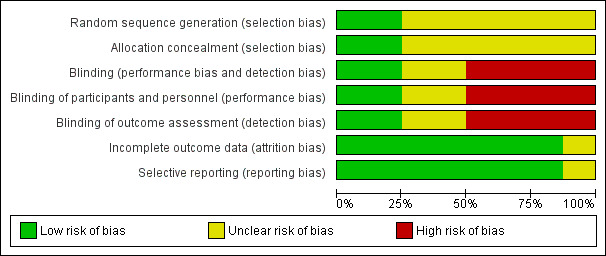

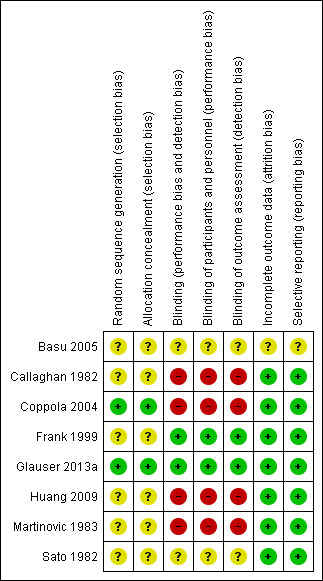

See Figure 2; Figure 3; Characteristics of included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Results of one study (Basu 2005) were published as an abstract. Despite several attempts to contact the research authors to obtain more information on methodological issues and risk of bias, we received no reply. Thus, for this study there is an unclear risk of bias.

Three of the included studies (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983) date back 30 years and there was an obvious difference in the quality of the reporting in comparison with the newer studies (Frank 1999; Coppola 2004; Huang 2009; Glauser 2013a).

Allocation

Only two of the studies described explicitly the methods of allocation concealment (Coppola 2004; Glauser 2013a).

Blinding

The studies reported by Sato (Sato 1982), Frank (Frank 1999), and Glauser (Glauser 2013a) were double‐blinded, whilst the studies reported by Martinovic (Martinovic 1983), Callaghan (Callaghan 1982), Coppola (Coppola 2004), and Huang (Huang 2009) were unblinded (high risk of bias). In two out of the three double‐blinded studies, placebo and active drugs were indistinguishable (Frank 1999; Glauser 2013a) and were considered to have a low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Five studies described losses to follow‐up or exclusions from analyses. Frank 1999 reports that one participant withdrew consent before treatment but after randomisation and that one participant did not comply but was included in the analysis. Martinovic 1983 reports that six of the initially recruited participants did not co‐operate and were not included in the analysis. Coppola 2004 reports loss of nine patients overall, all due to lack of efficacy, these patients exited the study at three months follow‐up; all randomised patients were included in the analysis. Huang 2009 reports that one patient in the valproate group was lost to follow‐up (no further specifications), whereas two patients in the lamotrigine group were withdrawn due to severe adverse effects (systemic anaphylaxis rash). Glauser 2013a reports that among the 453 patients enrolled, seven were withdrawn due to ineligibility at baseline, so that 446 participants were included in subsequent effectiveness analyses and 451 participants in safety analyses. Two reports (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982) did not make an explicit statement that participants were not lost to follow‐up or excluded from analyses.

Selective reporting

Seven of the studies were assessed at low risk of bias (Callaghan 1982; Coppola 2004; Frank 1999; Glauser 2013a; Huang 2009; Martinovic 1983; Sato 1982); the remaining study was assessed at unclear risk of bias (Basu 2005).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Ethosuximide compared to valproate for absence seizures in children and adolescents.

| Ethosuximide compared to valproate for absence seizures in children and adolescents | ||||||

| Patient or population: absence seizures in children and adolescents Setting: outpatients Intervention: ethosuximide Comparison: valproate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with valproate | Risk with Ethosuximide | |||||

| Seizure freedom at 12 months | Study population | ‐ | 365 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | None of the included trials found a difference for this outcome. Length of follow‐up in included studies: from 6 weeks to 4 years |

|

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency | Study population | RR 0.70 (0.19 to 2.59) | 29 (1 RCT)a | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 | No difference was found, but the confidence interval is wide and equivalence cannot be inferred. Length of follow‐up: 6 weeks. |

|

| 286 per 1,000 | 200 per 1,000 (54 to 740) | |||||

| 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency | Study population | ‐ | 49 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4 5 | No difference was found, but the confidence interval is wide and equivalence cannot be inferred. Length of follow‐up in included studies: from 1 to 4 years. |

|

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Normalization of the EEG ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse effects (Table 7; Table 8) Ethosuximide treatment was mostly associated with nausea, vomiting, and behavioural/psychiatric changes. The most common adverse effects of treatment with valproate were fatigue, nausea, vomiting, increased appetite with weight gain, behavioural/psychiatric changes (decreased concentration, personality change, hyperactivity, attention problems, hostility), and thrombocytopenia | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias; plausible bias is likely to seriously alter the results.

2 Information is from a study with unclear and high risk of bias; plausible bias is likely to seriously alter the results.

3 Small number of patients included in this study (29) (see also footnote below).

4 Information is from two small studies with unclear or high risk of bias; plausible bias is likely to seriously alter the results.

5 Information is from two studies with small number of patients included.

aIn this study, one patient in the ethosuximide group was subsequently treated with valproate, but failed to respond to either single drug and did not improve when both drugs were used in combination. The outcomes of this patient on combined treatment were therefore counted twice ("no remission"), since the patient received both drugs.

Summary of findings 2. Lamotrigine compared to valproate for absence seizures in children and adolescents.

| Lamotrigine compared to valproate for absence seizures in children and adolescents | ||||||

| Patient or population: absence seizures in children and adolescents Setting: outpatients Intervention: lamotrigine Comparison: valproate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with valproate | Risk with Lamotrigine | |||||

| Seizure freedom at 12 months | Study population | ‐ | 405 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Higher proportion seizure free at 1 month in patients receiving valproate compared to those receiving lamotrigine (2 studies). No difference between valproate and lamotrigine for seizure freedom at 3 and 6 months (3 and 4 studies, respectively). Length of follow‐up in included studies: 12 months |

|

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Normalization of the EEG | Study population | RR 2.39 (1.14 to 5.04) | 45 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2,3 | Length of follow‐up: 12 months | |

| 273 per 1,000 | 652 per 1,000 (311 to 1,000) | |||||

| Adverse effects (Table 7; Table 9) The most common adverse effects of treatment with lamotrigine were fatigue, and behavioural/psychiatric changes. The most common adverse effects of treatment with valproate were fatigue, nausea, vomiting, increased appetite with weight gain, behavioural/psychiatric changes (decreased concentration, personality change, hyperactivity, attention problems, hostility), and thrombocytopenia | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Most information comes from studies at low or unclear risk of bias; plausible bias is likely to seriously alter the results.

2 Information comes from a small study at unclear and high risk of bias.

3 Information comes from a single study conducted in a small number of patients.

Summary of findings 3. Ethosuximide compared to lamotrigine for absence seizures in children and adolescents.

| Ethosuximide compared to lamotrigine for absence seizures in children and adolescents | ||||||

| Patient or population: absence seizures in children and adolescents Setting: outpatients Intervention: ethosuximide Comparison: lamotrigine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with lamotrigine | Risk with Ethosuximide | |||||

| Seizure freedom at 12 months | Study population | RR 0.47 (0.33 to 0.67) | 300 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Length of follow‐up: 12 months | |

| 455 per 1,000 | 214 per 1,000 (150 to 305) | |||||

| 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Normalization of the EEG ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse effects (Table 8; Table 9) Ethosuximide treatment was mostly associated with nausea, vomiting, and behavioural/psychiatric changes. The most common adverse effects of treatment with lamotrigine were fatigue, and behavioural/psychiatric changes. | ||||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

Lamotrigine versus placebo

We found one study (Frank 1999) comparing lamotrigine with placebo which recruited 29 participants. As outlined in Description of studies above, this trial used a responder‐enriched design where participants responding to lamotrigine during a pre‐randomisation baseline phase were randomised to continue lamotrigine or have it withdrawn. This trial therefore compares the effect of continuing versus withdrawing lamotrigine. The results were as follows:

in the initial open‐label dose‐escalation phase, 71% of the participants became seizure free on lamotrigine using a 24‐hour EEG/video telemetry recording;

in the placebo‐controlled phase 64% of the participants on lamotrigine remained seizure free versus 21% receiving placebo (P < 0.03).

Valproate versus placebo

We found no trials comparing valproate versus placebo.

Ethosuximide versus placebo

We found no trials comparing ethosuximide versus placebo.

Ethosuximide versus valproate

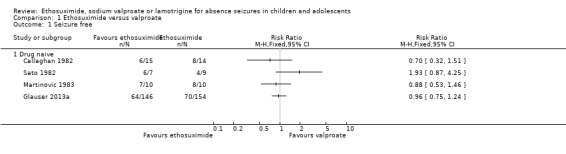

We found four studies comparing valproate with ethosuximide (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983; Glauser 2013a). Due to differences in study design, participants and length of follow‐up we did not think it appropriate to pool results in a meta‐analysis. For our chosen outcome 'seizure freedom', we were unable to extract data for this outcome at the time points we had specified (one, six and 18 months). Rather than not present any data for this outcome, we have summarised results for individual trials, where the proportion of participants seizure free during follow‐up was reported. Results for individual studies are presented below as well as in Analysis 1.1, Analysis 1.2 and Analysis 1.3

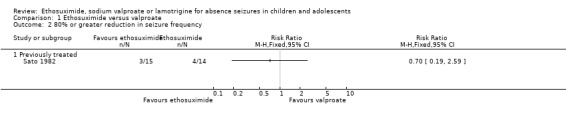

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ethosuximide versus valproate, Outcome 1 Seizure free.

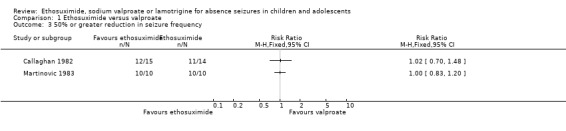

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ethosuximide versus valproate, Outcome 2 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ethosuximide versus valproate, Outcome 3 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

(1) Seizure freedom

The risk ratio (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for seizure freedom (RR < 1 favours ethosuximide) are (Analysis 1.1):

(a) Callaghan 1982: RR 0.70 (95% CI 0.32 to 1.51); seizure freedom was observed in six out of 15 patients receiving valproate and in eight out of 14 patients receiving ethosuximide. One patient in the ethosuximide group was subsequently treated with valproate, but failed to respond to either single drug and did not improve when both drugs were used in combination. The outcomes of this patient on combined treatment were therefore counted twice ("no remission"), since the patient received both drugs.

(b) Sato 1982: RR 1.93 (95% CI 0.87 to 4.25); the proportion of patients achieving seizure freedom in both groups is not explicitly reported.

(c) Martinovic 1983: RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.46); seizure freedom was observed in seven out of 10 patients receiving valproate and in eight out of 10 patients receiving ethosuximide.

(d) Glauser 2013a: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.24); seizure freedom was observed in 64 out of 146 patients receiving valproate and in 70 out of 154 patients receiving ethosuximide.

Hence, none of these trials found a difference for this outcome.

(2) 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

This outcome was only reported by Sato 1982, and the RR was 0.70 (95% CI 0.19 to 2.59, Analysis 1.2); the proportion of patients achieving 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency in both groups was not explicitly reported. Again, no difference was found, but the confidence interval is wide and equivalence cannot be inferred.

(3) 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency

This was reported for two trials (Analysis 1.3). In one trial (Martinovic 1983), all participants achieved this outcome (10/10 in the valproate and 10/10 in the ethosuximide group). For the other trial (Callaghan 1982) the RR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.48); 12 out of 15 patients receiving valproate and 11 out of 14 patients receiving ethosuximide experienced 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency. Again, no difference is found, but the confidence interval is wide and equivalence cannot be inferred. In this study, one patient in the ethosuximide group was subsequently treated with valproate, but failed to respond to either single drug and did not improve when both drugs were used in combination. The outcomes of this patient on combined treatment were therefore counted twice ("no remission").

Lamotrigine versus valproate

We found four studies comparing valproate with lamotrigine (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009; Glauser 2013a). Due to differences in study design, participants and length of follow‐up, we did not think it appropriate to pool results in a meta‐analysis. For our chosen outcome 'seizure freedom', we were unable to extract data for this outcome at the time points we had specified (one, six and 18 months). Rather than not present any data for this outcome, we have summarised results for individual trials, where the proportion of participants seizures free during follow‐up was reported. Results for individual studies are presented below as well as in Analysis 2.1 and Analysis 2.2.

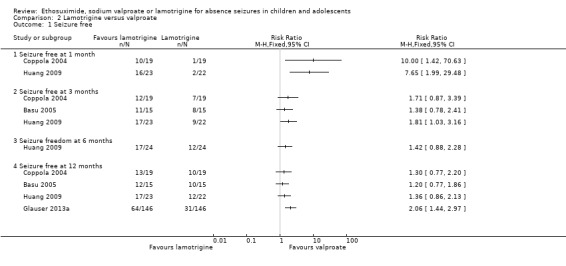

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lamotrigine versus valproate, Outcome 1 Seizure free.

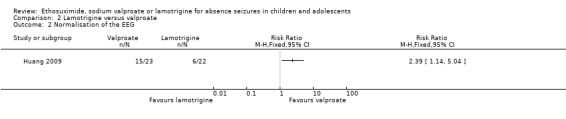

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Lamotrigine versus valproate, Outcome 2 Normalisation of the EEG.

(1) Seizure freedom at one month

This outcome was reported in two trials (Coppola 2004; Huang 2009;). One study (Coppola 2004) comparing valproate and lamotrigine head‐to‐head, recruited drug‐naive children with typical AS. The primary outcome measure was total seizure freedom and was assessed at one, three and 12 months. At one‐month follow‐up 52.6% of patients taking valproate (10 out of 19) were seizure free compared to only 5.3% of patients taking lamotrigine (one out of 19) (P = 0.004). The other study (Huang 2009) compared valproate with lamotrigine monotherapy in drug‐naive children with newly diagnosed childhood As (typical seizures). After one month of treatment 16/23 patients (74%) receiving valproate and 2/22 (41%) receiving lamotrigine were seizure free.

(2) Seizure freedom at three months

This outcome was reported in three trials (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009;). In the first study (Coppola 2004), at three months seizure freedom was observed in 12 out of 19 (63.1%) patients taking sodium valproate and in seven out of 19 (36.8%) patients taking lamotrigine (P = 0.19). In one study (Basu 2005) after three months, 11 patients out of 15 (73.3%) in the sodium valproate and eight patients out of 15 (53.3%) in the lamotrigine group receiving lamotrigine were seizure free. In the third study (Huang 2009), 17/23 patients (70%) receiving valproate and 9/22 (9%) receiving lamotrigine were seizure free at three months.

(3) Seizure freedom at six months

Only one study (Huang 2009) reported data on this outcome: 17/24 patients (71%) receiving valproate and 12/24 (50%) receiving lamotrigine were seizure free at six months.

(4) Seizure freedom at 12 months

This outcome was reported for four trials (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009; Glauser 2013a). The RR estimates with 95% CIs for seizure freedom (RR < 1 favours lamotrigine) at 12 months are (Analysis 2.1):

(a) Coppola 2004: 1.30 (95% CI 0.77 to 2.20);

(b) Basu 2005: 1.20 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.86);

(c) Huang 2009: 1.36 (95% CI 0.86 to 2.13);

(d) Glauser 2013a: 2.06 (95% CI 1.44 to 2.97).

Hence, none of these trials found a difference for this outcome. However, confidence intervals are all wide and the possibility of important differences has not been excluded and equivalence cannot be inferred.

(5) Normalisation of the EEG

Only one study (Huang 2009) explicitly reported data on this outcome. The proportion showing normal EEG at 12 months in the lamotrigine group (6/22, 27.3%) was significantly lower than that in the valproic acid group (15/23, 65.2%) (P < 0.05); RR = 2.39 (95% CI: 1.14 to 5.04; P = 0.0218).

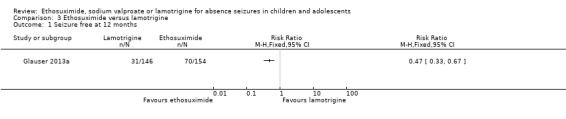

Ethosuximide versus lamotrigine

One study (Glauser 2013a), compared ethosuximide and lamotrigine in drug‐naive patients with childhood AS. The main effectiveness outcome was the freedom from treatment failure assessed 12 months after randomisation. Freedom from treatment failure was also assessed at 16 to 20 weeks, and in between 16 and 20 weeks and month 12. Treatment failure was defined as failure either due to lack of seizure control, or meeting safety exit criteria, or withdrawal from the study for any other reason. Seizure freedom at 12 months after randomisation was higher in patients taking ethosuximide (70/154, 45%) than in patients taking lamotrigine (31/146, 21%; P < 0.001). At 16 to 20 weeks, freedom from treatment failure was observed in 81/154 (53%) patients taking ethosuximide and 43/146 (29%) patients taking lamotrigine.

Adverse effects related to the use of ethosuximide, sodium valproate or lamotrigine

This section and the related tables apply to all studies and comparisons.

The most common adverse effects of treatment with valproate reported by the studies assessing this drug (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983; Huang 2009; Glauser 2013a) were fatigue, nausea, vomiting, increased appetite with weight gain, behavioural/psychiatric changes (decreased concentration, personality change, hyperactivity, attention problems, hostility), and thrombocytopenia (Table 7).

1. Adverse effects on valproate: number of participants experiencing each event.

| Event | Callaghan 1982 | Sato 1982 | Martinovic 1983 | Coppola 2004 | Huang 2009 | Glauser 2013 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | |||||

| Obesity/Weight gain | 1 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Drowsiness | 4 | |||||

| Nausea | 5 | 3 | 12* | |||

| Vomiting | 1 | 2 | 12* | |||

| Decreased platelet numbers | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Increased appetite | 15 | |||||

| Poor appetite | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Dizziness | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Hyperactivity | 23 | |||||

| Attention problems | 24 | |||||

| Hostility | 22 | |||||

| Concentration decreased | 18 | |||||

| Personality change | 17 | |||||

| Sleep problem | 17 | |||||

| Depression | 11 | |||||

| Slow process speed | 11 | |||||

| Memory problem | 10 | |||||

| Apathy | 9 | |||||

| Fatigue | 27 | |||||

| Headache | 1 | 18 | ||||

| Leukopenia | 2 | |||||

| Elevated liver function tests | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Elevated LDH | 1 | |||||

| Rash | 2 |

* Nausea, vomiting, or both LDH: lactate dehydrogenase

Numbers of individuals within each study undertaking valproate: 14 (Callaghan 1982), 22 (Sato 1982), 10 (Martinovic 1983), 19 (Coppola 2004), 23 (Huang 2009), 146 (Glauser 2013a).

Ethosuximide treatment was mostly associated with nausea, vomiting, and behavioural/psychiatric changes (Table 8).

2. Adverse effects on ethosuximide: number of participants experiencing each event.

| Event | Callaghan 1982 | Sato 1982 | Martinovic 1983 | Glauser 2013 |

| Drowsiness | 1 | 5 | ||

| Tiredness | 2 | |||

| Nausea | 3 | 2 | 29* | |

| Vomiting | 3 | 29* | ||

| Increased appetite | 6 | |||

| Poor appetite | 1 | 10 | ||

| Diarrhoea | 9 | |||

| Dizziness | 1 | 10 | ||

| Headache | 2 | 23 | ||

| Leukopenia | 3 | |||

| Hiccups | 1 | |||

| Moodiness | 1 | |||

| Hyperactivity | 13 | |||

| Attention problems | 8 | |||

| Hostility | 4 | |||

| Concentration decreased | 6 | |||

| Personality change | 6 | |||

| Sleep problem | 11 | |||

| Depression | 4 | |||

| Slow process speed | 3 | |||

| Memory problem | 0 | |||

| Apathy | 4 | |||

| Fatigue | 26 | |||

| Rash | 6 |

* Nausea, vomiting, or both

Numbers of individuals within each study undertaking ethosuximide: 14 (Callaghan 1982), 23 (Sato 1982), 10 (Martinovic 1983), 154 (Glauser 2013a).

The most common adverse effects of treatment with lamotrigine were fatigue, and behavioural/psychiatric changes (Table 9). In one lamotrigine study (Frank 1999), the most commonly reported adverse event was rash (reported on 11 occasions in 10 patients). However, only in one of the individuals was this thought to be related to lamotrigine. There were two serious adverse events during the treatment, but they were judged to be unrelated to treatment. In one study (Huang 2009), systemic anaphylaxis rash during lamotrigine treatment led to patients´ withdrawal from the study. In the Glauser 2013a study, no side effects (including rash, reported in two patients taking valproate, six patients taking ethosuximide, and six patients taking lamotrigine) occurred more frequently in the lamotrigine cohort compared to the other treatment groups (valproate and ethosuximide).

3. Adverse effects on lamotrigine: number of participants experiencing each event.

| Event | Frank 1999 | Coppola 2004 | Huang 2009 | Glauser 2013 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 | |||

| Headache | 2 | 2 | 14 | |

| Nausea | 3 | 2* | ||

| Vomiting | 2* | |||

| Poor appetite | 2 | 9 | ||

| Increased appetite | 1 | 10 | ||

| Diarrhoea | 2 | |||

| Dizziness | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Hyperkinesia | 2 | |||

| Hyperactivity | 12 | |||

| Attention problems | 11 | |||

| Hostility | 11 | |||

| Concentration decreased | 9 | |||

| Personality change | 10 | |||

| Sleep problem | 5 | |||

| Depression | 11 | |||

| Slow process speed | 7 | |||

| Memory problem | 8 | |||

| Apathy | 3 | |||

| Fatigue | 1 | 18 | ||

| Rash | 10 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Nervousness | 1 | |||

| Diplopia | 1 |

* Nausea, vomiting, or both

Numbers of individuals within each study undertaking lamotrigine: 15 (Frank 1999), 19 (Coppola 2004), 24 (Huang 2009), 146 (Glauser 2013a).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Since the last version of this review was published, we have found no new studies. Hence we have made no changes to the conclusions of this update as presented in the last updated version of this review (Brigo 2017).

Despite absence seizures (AS) being a relatively common seizure type in children, we found only eight randomised controlled trials, seven of them recruiting 20 to 48 participants. Only the study of Glauser 2013a included a much larger sample.

One trial compared lamotrigine with placebo (Frank 1999), three compared ethosuximide with valproate (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983), three compared lamotrigine with valproate (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009), and one compared ethosuximide, valproate, and lamotrigine (Glauser 2013a).

The trial comparing lamotrigine with placebo (Frank 1999), found that individuals becoming seizure free on lamotrigine, were more likely to remain seizure free if they were randomised to stay on lamotrigine rather than placebo. In essence, this trial assessed the effect of lamotrigine withdrawal. Although this trial finds evidence of an effect of lamotrigine on AS, it was of only four weeks duration, and the design is inadequate to inform clinical practice. Also, clinicians and people living with epilepsy are likely more concerned with how drugs compare with each other rather than with placebo.

Three studies (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009) directly compared lamotrigine with the long‐established treatment for typical AS, sodium valproate. All three studies found both valproate and lamotrigine to be efficacious in the treatment of typical AS in children. However, in these studies (Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009) the study sample size was small (38, 30 and 48 patients, respectively), and estimates are therefore imprecise.

Most robust results are provided by the much larger study including three groups: valproic acid, lamotrigine and ethosuximide (Glauser 2013a). This study found that at 12 months, the freedom‐from‐failure rates for ethosuximide and valproic acid were similar and were higher than the rate for lamotrigine. The frequency of treatment failures due to lack of seizure control (P < 0.001) and intolerable adverse events (P < 0.037) was significantly different among the treatment groups. Almost two thirds of the 125 participants with treatment failure due to lack of seizure control were in the lamotrigine cohort. The largest subgroup (42%) of the 115 participants discontinuing due to adverse events was in the valproic acid group. Overall, this study demonstrates the superior effectiveness of ethosuximide and valproic acid compared to lamotrigine as initial monotherapy aimed to control seizures without intolerable adverse events in children with childhood absence epilepsy. Because of the higher rate of adverse events leading to drug discontinuation and the significant negative effects on attentional measures seen in the valproate cohort, the authors concluded that ethosuximide represents the optimal initial empirical monotherapy for childhood absence epilepsy. Notably, this study was the very first randomised controlled trial (RCT) to meet the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) criteria for class I evidence for childhood absence epilepsy (or for any type of generalised seizure in adults or children) (Glauser 2006). Consequently, ethosuximide and valproate were designed/designated as treatments with level A evidence in children with childhood absence epilepsy in the recent ILAE treatment guidelines (Glauser 2013b). Data on tolerability of valproate reported in the included studies are consistent with the general adverse‐effects profile of this drug. Adverse effects often seen with valproate treatment are dyspepsia, weight gain, tremor, transient hair loss and haematological abnormalities (Panayiotopoulos 2001). The occurrence of rash in patients receiving lamotrigine is a well‐known adverse event of this drug and its risk may be reduced by slow titration (Wang 2015).

Quality of the evidence

The description of important methodology was sometimes poor, and only two studies (Coppola 2004; Glauser 2013a) gave a description of allocation concealment. Three of the trials were explicitly reported as double‐blind (Sato 1982; Frank 1999; Glauser 2013a). In three of the trials there was no mention of losses to follow‐up or exclusions from analyses. The trials used a variety of methodologies; six were parallel trials (Callaghan 1982; Martinovic 1983; Coppola 2004; Basu 2005; Huang 2009; Glauser 2013a) and two used response conditional designs (Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983). The length of follow‐up ranged from four weeks to four years.

Using GRADE, we assessed the certainty of the evidence to be very low to high for outcomes for which data were available. The reasons for these judgements are outlined in the Table 1; Table 2; Table 3. We assessed the study of Glauser 2013a as being at low risk of bias, and providing high quality of evidence for outcomes for which data were available. However, the quality of evidence provided by the other included studies was low, primarily due to risk of bias and imprecise results because of the small sample size. Hence, conclusions regarding the efficacy of ethosuximide, valproic acid and lamotrigine derive mostly from the large and high‐quality RCT by Glauser 2013a. Hence, we rated the overall quality of the evidence for most outcomes to be moderate or high, although we downgraded the evidence for outcomes for which data were obtained from small studies judged at unclear or high risk of bias to low or very low.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The good efficacy profile of ethosuximide for the treatment of absence seizures as shown in Glauser 2013a confirms results of three other smaller studies that compared ethosuximide with valproate (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983); all of these three smaller studies reported a superior efficacy profile for ethosuximide over valproate with regards to seizure freedom (Callaghan 1982; Sato 1982; Martinovic 1983), although with wide confidence intervals due to small sample size. However, it is noteworthy to consider that ethosuximide does not suppress tonic‐clonic seizures (Berkovic 1993), and it has even been suggested that it can transform absences into grand mal seizures (Glauser 2002), although with contrasting data (Schmitt 2007). Hence, ethosuximide should probably be avoided in patients with AS and co‐existing generalised tonic‐clonic seizures.

Significance

There are no placebo‐controlled trials for ethosuximide or valproate, and hence no evidence from RCTs to support a specific effect on AS for either of these two drugs. Due to the differing methodologies used in the trials comparing ethosuximide, lamotrigine and valproate, we thought it inappropriate to undertake a meta‐analysis. Hence, recommendations for practice from this review are based on a narrative comparison. Further trials with larger size than many of the studies currently included in this review are required. Further research could allow results to be pooled, leading to a quantitative rather than a qualitative summary of results. In summary, ethosuximide, lamotrigine and valproate are commonly used to treat children and adolescents with AS. We now have evidence from a recently conducted, high‐quality, large trial that ethosuximide and valproate have higher efficacy than lamotrigine as initial monotherapy in children and adolescents with AS. This study showed a higher rate of adverse events leading to drug discontinuation and significant negative effects on attentional measures in the valproate group. Consequently, with regards to both efficacy and tolerability, ethosuximide represents the optimal initial empirical monotherapy for children and adolescents with AS. However, the use of ethosuximide should be avoided in patients with As and generalised tonic‐clonic seizures, as this drug is probably inefficacious on tonic‐clonic seizures.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Since the last version of this review was published, we have found no new studies. Hence, we have made no changes to the conclusions of this update as presented in the initial review. With regards to both efficacy and tolerability, ethosuximide represents the optimal initial empirical monotherapy for children and adolescents with absence seizures (AS). However, if absence and generalised tonic‐clonic seizures co‐exist, valproate should be preferred over ethosuximide, as this drug is probably inefficacious on tonic‐clonic seizures. These implications for practice rely on results of trials that were heterogeneous. Larger trials could further clarify or change implications for practice in the future.

Implications for research.

We now have moderate to high evidence that ethosuximide and valproate have higher efficacy than lamotrigine as initial monotherapy in children and adolescents with AS, and that ethosuximide is better tolerated. Due to its good profile in terms of both efficacy and tolerability, ethosuximide should be considered as the standard treatment if only AS are present. However, if absence and generalised tonic‐clonic seizures co‐exist, valproate should be preferred. Placebo‐controlled trials in people with newly diagnosed epilepsy will provide evidence for an effect and aid in the interpretation of comparative studies should such studies find equivalence. However, clinical practice is best informed by trials that compare the effect of one drug with another. Such trials should be pragmatic in concept and given that AS are relatively common, they should also be feasible. If possible, future trials should be of a larger size than many of the studies currently included in this review. In addition, such trials will need to be of at least 12 months' duration and measure outcomes which include remission from seizures, EEG with a hyperventilation test, adverse effects, quality of life and psychosocial outcomes.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new studies identified; conclusions are unchanged. |

| 29 May 2018 | New search has been performed | Searches updated on 29 May 2018. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 September 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches updated on 1 September 2016. |

| 1 September 2016 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Three new studies have been included (Basu 2005; Glauser 2013a; Huang 2009); conclusions have changed. |

| 16 November 2009 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 16 November 2009. One study (Basu 2005) has been added to the studies awaiting assessment section ‐ one of the co‐review authors (Khalid Mohammed) will try to contact the authors for more information on this study. This information will be included in the next update of this review. One study still remains in the studies awaiting assessment section (Suzuki 1972). This paper is in Japanese. Once the paper has been translated the review authors will decide whether to include this study or not. This information will be included in the next update of this review. One study (Holmes 2008) has been added as an excluded study. |

| 26 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 15 August 2007 | New search has been performed | We re‐ran our searches on 27 July 2007; no new studies were identified. |

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the hard and valuable work that went in to the original version of the review by Ewa Posner, Khalid Mohamed and Tony Marson.

This review update was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Epilepsy Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web) search strategy

1. (Avugane OR Baceca OR Convulex OR Delepsine OR Depacon OR Depakene OR Depakine OR Depakote OR Deproic OR Epiject OR Epilex OR Epilim OR Episenta OR Epival OR Ergenyl OR Mylproin OR Orfiril OR Orlept OR Selenica OR Sprinkle OR Stavzor OR Valcote OR Valparin OR Valpro OR Valproate OR Valproic OR VPA):AB,KW,MC,MH,TI

2. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Valproic Acid Explode All

3. (Aethosuximide OR Emeside OR Ethosucci* OR Ethosuxide OR Ethosuximide OR Etosuximida OR Zarontin):AB,KW,MC,MH,TI

4. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Ethosuximide Explode All

5. (Epilepax OR Lamictal OR Lamotrigin* OR Lamotrine OR Lamitrin OR Lamictin OR Lamogine OR Lamitor):AB,KW,MC,MH,TI

6. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5

7. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Epilepsy, Absence Explode All

8. absence adj1 (epilep* or seizure*)

9. "petit mal"

10. #7 OR #8 OR #9

11. #6 AND #10

12. >01/09/2016:CRSINCENTRAL

13. #11 AND #12

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

This search strategy is based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials (Lefebvre 2011).

1. (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial or pragmatic clinical trial).pt. or (randomi?ed or placebo or randomly).ab.

2. clinical trials as topic.sh.

3. trial.ti.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

6. 4 not 5

7. (Avugane or Baceca or Convulex or Delepsine or Depacon or Depakene or Depakine or Depakote or Deproic or Epiject or Epilex or Epilim or Episenta or Epival or Ergenyl or Mylproin or Orfiril or Orlept or Selenica or Sprinkle or Stavzor or Valcote or Valparin or Valpro or Valproate or Valproic or VPA).tw.

8. *Valproic Acid/

9. (Aethosuximide or Emeside or Ethosucci* or Ethosuxide or Ethosuximide or Etosuximida or Zarontin).tw.

10. *Ethosuximide/

11. (Epilepax or Lamictal or Lamotrigin* or Lamotrine or Lamitrin or Lamictin or Lamogine or Lamitor).tw.

12. 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

13. exp Epilepsy, Absence/

14. (absence adj1 (epilep$ or seizure$)).tw.

15. petit mal.tw.

16. 13 or 14 or 15

17. 6 and 12 and 16

18. limit 17 to ed=20160901‐20180529

19. 17 not (1$ or 2$).ed.

20. 19 and (2016$ or 2017$ or 2018$).dt.

Appendix 3. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

Condition: absence seizures OR absence epilepsy

Intervention: Ethosuximide OR sodium valproate OR lamotrigine

First received from 09/01/2016 to 05/29/2018

Appendix 4. WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search strategy

Condition: absence seizures OR absence epilepsy

Intervention: Ethosuximide OR sodium valproate OR lamotrigine

Date of registration between 01/09/2016 and 29/05/2018

Appendix 5. SCOPUS search strategy

(((TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(valproic or valproate or Epilim)) OR (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(ethosuximide or Zarontin)) OR (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(lamotrigine or Lamictal))) AND ((TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(absence W/1 (epilep* or seizure*))) OR (TITLE‐ABS‐KEY("petit mal"))) AND (TITLE((randomiz* OR randomis* OR controlled OR placebo OR blind* OR unblind* OR "parallel group" OR crossover OR "cross over" OR cluster OR "head to head") PRE/2 (trial OR method OR procedure OR study)) OR ABS((randomiz* OR randomis* OR controlled OR placebo OR blind* OR unblind* OR "parallel group" OR crossover OR "cross over" OR cluster OR "head to head") PRE/2 (trial OR method OR procedure OR study)))) AND (PUBYEAR > 2003)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Ethosuximide versus valproate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Seizure free | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Drug naive | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 80% or greater reduction in seizure frequency | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Previously treated | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Lamotrigine versus valproate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Seizure free | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Seizure free at 1 month | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Seizure free at 3 months | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Seizure freedom at 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Seizure free at 12 months | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Normalisation of the EEG | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Ethosuximide versus lamotrigine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Seizure free at 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ethosuximide versus lamotrigine, Outcome 1 Seizure free at 12 months.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by year of study]

Callaghan 1982.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel open study designed to compare ESM with VPS treatment. Followed up for 18 months to 4 years, mean 3 years. | |

| Participants | 28 drug‐naive participants (13 male, 15 female), aged between 4 to 15 years. All participants with typical AS. | |

| Interventions | Monotherapy with ESM or VPS. | |

| Outcomes | Complete or partial (50% to 90%) remission of seizures confirmed by 6 hours telemetry and observation by parents and teachers. | |

| Notes | The report acknowledged support from Warner‐Lambert Pharmaceuticals, manufacturers of ethosuximide. One patient in the ethosuximide group was subsequently treated with valproate, but failed to respond to either single drug and did not improve when both drugs were used in combination. The outcomes of this patient on combined treatment were therefore counted twice ("no remission"). |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

Sato 1982.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind response ‐ conditional cross‐over study. VPS with PCB for 6 weeks followed by ESM with PCB for 6 weeks for one group. The other group followed the same regimen in a reverse order. Follow‐up 3 months. | |

| Participants | 45 drug‐naive and drug‐resistant participants aged 3 to 18 years with AS (not specified if typical or atypical); 18 male. | |

| Interventions | Drug‐naive participants were on monotherapy (ESM or VPS) while refractory to previous treatment participants were on polytherapy. | |

| Outcomes | Reduction in seizure frequency as judged by 12‐hour EEG telemetry, 100% for drug‐naive participants and 80% for drug‐resistant participants. | |

| Notes | The work was supported by a contract from the Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported how patients were randomly assigned to treatments. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study was described as quote: "double‐blinded" without further details. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study was described as quote: "double‐blinded" without further details. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study was described as quote: "double‐blinded" without further details. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

Martinovic 1983.

| Methods | Participants randomly assigned to either ESM or VPS treatment. Parallel open design. All were followed up for 1 to 2 years. 6 participants did not co‐operate; they were not included in the analysis. | |

| Participants | 20 participants with recent (less than 6 weeks) onset of 'simple absences' only, other types of seizures observed in 4 out of 5 participants whose seizures were not completely controlled. Age: 5 to 8 years old, 5 were male. | |

| Interventions | Monotherapy with ESM or VPS. | |

| Outcomes | Number of seizures per day as observed by parents. EEG . Number of children who achieved partial (50% to 75% decrease in seizure frequency) or full remission. Time to achieve complete seizure control. | |

| Notes | No information about sponsorship by a pharmaceutical company is given. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

Frank 1999.

| Methods | Randomised using 1:1 ratio, double‐blind, parallel design. This study was a second phase of a trial designed as 'responder‐enriched'. It followed an open‐label dose escalation trial. The LTG therapy was tapered over 2 weeks in the PCB group. The length of follow‐up for the randomised double‐blind study was 4 weeks. | |

| Participants | The individuals who became seizure free on LTG during a pre‐randomisation baseline randomised to continue LTG or to PCB. All participants who entered the preceding study were newly diagnosed children with typical AS. 29 participants were randomised, 15 into LTG group and 14 into PCB. 1 person in the LTG group withdrew consent. In the PCB group the age was 8.8+/‐3.1 years, 36% boys. In the LTG group the age was 6.9+/‐2.3 years, 36% were boys. | |

| Interventions | Monotherapy with LTG or PCB. | |

| Outcomes | Proportion of participants that remained seizure free, as measured by hyperventilation EEG. | |

| Notes | This study was sponsored by Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), makers of lamotrigine. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Lamotrigine was and placebo were identically matched. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Lamotrigine was and placebo were identically matched. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Lamotrigine was and placebo were identically matched. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

Coppola 2004.

| Methods | Randomised, parallel group unblinded study. Follow‐up for 12 months. | |

| Participants | 38 drug‐naive participants, all with typical AS, age 3 to 13 years. | |

| Interventions | Monotherapy with VPS or LTG. | |