Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are able to self-renew and have multi-lineage differentiation potential. However, studies on ovine umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) are limited. Our study aimed to isolate and characterize ovine UC-MSCs. We successfully isolated ovine UC-MSCs and defined their surface marker profile using immunofluorescence analysis. Ovine UC-MSCs were found to be positive for cell surface markers CD13, CD29, CD44, CD90, and CD106, and negative for cell surface marker CD45. Assessment of the proliferation potential of ovine UC-MSCs showed that from day 3 of cultivation a plateau phase was reached. And compare to passage 10, 15, 20 cells, passage 5 cells proliferating the fastest. Differentiation of ovine UC-MSCs into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes was also demonstrated by staining for tissue-specific markers and using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for specific marker gene expression. This study demonstrates the existence of a MSC population within the ovine umbilical cord, which maintained a normal karyotype up to passage 20.

Keywords: Isolation, Characterization, Mesenchymal stem cells, Ovine, Umbilical cord

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) undergo self-renew and permit multi-lineage differentiation into various tissues, including bone, cartilage, fat, tendon, muscle, and marrow stroma (Pittenger et al. 1999). MSCs express a number of defined surface markers and are negative for hematopoietic and macrophage markers (Liu and Han 2008). Experimental and clinical data demonstrate that MSCs possess low immunogenicity and have immunomodulatory capacity (Le Blanc and Ringdén 2006). Currently, MSCs are considered as a good candidate source for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering (Farini et al. 2014).

MSCs have been isolated from different tissues, including bone marrow (Rentsch et al. 2010), synovial membrane (Ando et al. 2012), adipose (Gruber et al. 2011), umbilical cord blood (Barker and Wagner 2003), and placenta (In't Anker et al. 2004; Miao et al. 2006). Compared to bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs), umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) share more common genes with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and have a faster self-renewal capacity (Hsieh et al. 2010). Compared to ESCs, UC-MSCs do not form teratomas when injected into NOD/SCID mice (Fong et al. 2007). UC-MSCs are reported to be a compatible stem cell source for allogeneic transplantation therapy, as they do not elicit immune rejection (Fong et al. 2011). Furthermore, the acquisition process of UC-MSCs is easy and non-invasive to donors.

Owing to different sensitive and behavior of MSCs to biological elements and skeletal components, MSC applications in regeneration of bone tissue were varied in species (Caplan and Bruder 2001). Compared to other large animals, ovine is ideal animal model because of ease of handling, housing, cost, and greater ethical acceptance. To date, the majority of research into ovine MSCs has been focused on bone marrow (McCarty et al. 2009), peripheral blood (Lyahyai et al. 2012), liver, adipose tissue (Heidari et al. 2013), and amniotic fluid (Fei et al. 2013). However, research into MSCs derived from ovine umbilical cord is minimal. Our study shows that ovine UC-MSCs can be successfully isolated and characterized, demonstrating a tri-lineage differentiation capacity. Here, we report on a novel source of ovine MSCs, which provides a basis for further investigation into ovine UC-MSCs.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of ovine UC-MSCs

Umbilical cords were obtained from sheep at 4–8 weeks of pregnancy, and were prepared using the enzymatic digestion method. Briefly, ovine umbilical cords were chopped into 1-mm3 tissue fragments, followed by addition of 0.1% collagenase type II (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) with digestion for 1 h at 37 °C. Tissue fragments were then incubated in 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 30 min. The resultant mixture was filtered through a 200-μm mesh screen to remove non-digested tissue prior to being washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were resuspended in growth medium (GM) and plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2 in 10-mm cell culture dishes (Corning, NY, USA) with incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2. GM comprised Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (F-12, HyClone; Thermo Scientific, Beijing, China), 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA),10 mM Glutamax (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 2 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; PeproTech inc., Rocky hill, nJ, USA), 10 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA), 0.1 μM dexamethasome (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA), and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). GM was replaced every 3 days and on reaching approximately 80% confluence, cells were dissociated using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reseeded under identical conditions at a split ratio of 1:3. All procedures were carried out under aseptic conditions.

Immunofluorescence analysis of ovine UC-MSC surface markers

Passage 5 ovine UC-MSCs (80% confluence) were harvested with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA and seeded into 6 well-plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells/cm2. After 24 h, ovine UC-MSCs were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min, then incubated with rabbit anti-mouse CD29, CD13, CD44, CD45, CD90 and CD106 primary antibodies (all purchased from Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China). All antibodies were at a 1:100 dilution with overnight exposure at 4 °C. Cells were then treated with sheep anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China) at a working dilution of 1:100 for 2 h at room temperature. Finally stained with stained cell nucleus with 4-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 15–30 min. Stained ovine UC-MSCs were then analyzed with Lecia Application Suite V4 software.

Cell proliferation of ovine UC-MSCs

To confirm the cell proliferation potential of ovine UC-MSCs, cells at passage 5, 10, 15, and 20 were seeded into 96-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/mL and cultured in GM for 7 days. On days 1–7, 10 μL of fluorescent solution which prepared by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Nantong, Jiangsu, China) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The absorbance at 450/650 nm was measured using a Varioskan Flash instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA). GraphPad Prism 5 was then used to determine the mean values and create the growth curve.

In-vitro adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation

Ovine UC-MSCs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in GM for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with either adipogenic, osteogenic, or chondrogenic induction medium (described below) for 21 days prior to differentiation analysis. For control samples, equal cell numbers were cultured in GM.

Adipogenic induction medium comprised Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, Hyclone), 10% FBS, 10 mM Glutamax (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1 μM dexamethasone (Solarbio, Beijing, China), 0.5 mM isobutyl methyl xanthine, 5 μg/mL insulin, and 60 μM indomethacin. Control and induced ovine UC-MSCs were stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich) to observe lipid droplet formation.

Osteogenic induction medium comprised IMDM,10% FBS, 0.05 mM ascorbic acid, 10 mM Glutamax (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 nM dexamethasone (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA). Control and induced ovine UC-MSCs were stained with AgNO3 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA) then counter-stained in hematoxylin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA).

Chondrogenic induction medium comprised IMDM, 10% FBS, 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM Glutamax, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, and 10 ng/mL human transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1). Control and induced ovine UC-MSCs were stained with Alcian blue (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA) to identify acid mucopolysaccharide synthesis. All samples were assessed in duplicate.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) of ovine UC-MSCs

To determine the ovine UC-MSC differentiation potential, differentiation genes were assessed by RT-qPCR. Total mRNA was extracted from control and induced cells by TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, Mount Waverley, Victoria, Australia). Differentiation gene primers were designed by Takara (Table 1, Takara, Dalian, China). cDNA synthesis was performed using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara). Amplification experiments were performed in triplicate using Fast SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara) and the StepOne™ Real Time System (Takara). Levels of gene expression were determined using the comparative − 2∆∆Ct method. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to normalize the expression levels for each gene. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic markers analysed by RT-qPCR

| Gene | Primer sequences | Accession numbers | Product Length (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | |||

| GAPDH | ACCACTGTCCACGCCATCAC | GCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTT | U94889.1 | 269 |

| BGLAPa | GCAGCGAGGTGGTGAAGA | CCTGGAAGCCGATGTGGT | DQ418490 | 99 |

| SCD | GCTGGCACATCAACTTTACCAC | TTTCCTCTCCAGTTCTTTTCATCC | AJ001048.1 | 123 |

| LUM | AGAATTAACGAAAGCAGGGTCAAG | GCCAAGAGGAGAGGAAACACA | NM_173934.1 | 84 |

| BGN | GAACGGGAGCCTGAGTTTTCT | ACTTTGGTGATGTTGTTGGTGTG | NM-001009201.1 | 138 |

Primer designed through GenBank accession numbers of the sequences. Length of primers sequences (F: forward and R: reverse) and product length in base pairs (bp). Primers synthesized by Takara

aPrimers described in Lyahyai et al. (2012)

Karyotype analysis of ovine UC-MSCs

Passage 20 ovine UC-MSCs were plated into 10-mm cell culture dishes at a density of 3 × 104/cm2. During growth up to 50% confluence, cells were incubated with 1 μg/mL colchicines (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA) for 2.5 h at 37 °C. The cell suspension was then harvested and treated with hypotonic solution for 45 min. Finally, the cells were stained with Giemsa at a dilution of 1:100 and examined under a light microscope (Nikon, E100).

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for statistically significant differences). Data analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 5. Pearson correction tests are widely used in statistics to degree of the relationship between linear related variables, the P value tested by SPSS19.0 software.

Results

Isolation and expansion of ovine UC-MSCs

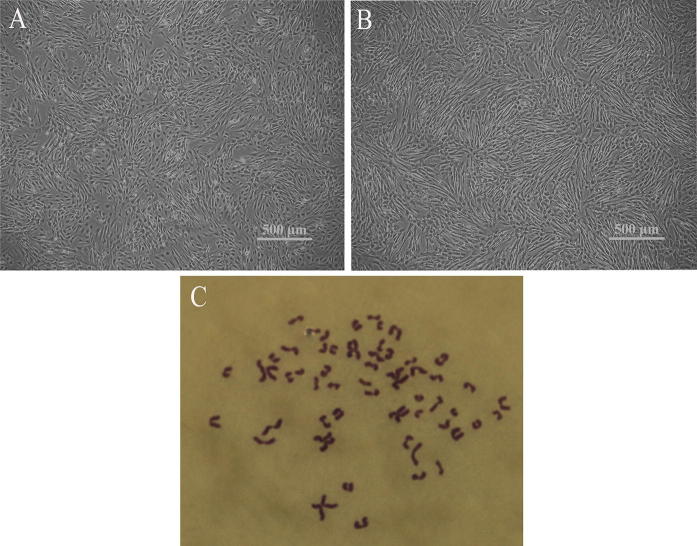

Ovine UC-MSCs were successfully isolated and culture expanded following plastic surface adherence up to passage 20. Morphology observation showed that ovine UC-MSCs were typical fibroblast-like cells, with no differences in morphology between passage 5 and 20 (Fig. 1a, b). Karyotype analysis determined that passage 20 ovine UC-MSCs were diploid cells with normal chromosome numbers (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Morphological phenotype and karyotype of ovine umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. a Passage 5 an b passage 20 ovine UC-MSCs displayed classic fibroblastic-like morphology, with no differences in morphological phenotype detected between passage 5 and 20. c A diploid ovine UC-MSC expanded to passage 20 maintaining 54 pairs of chromosomes

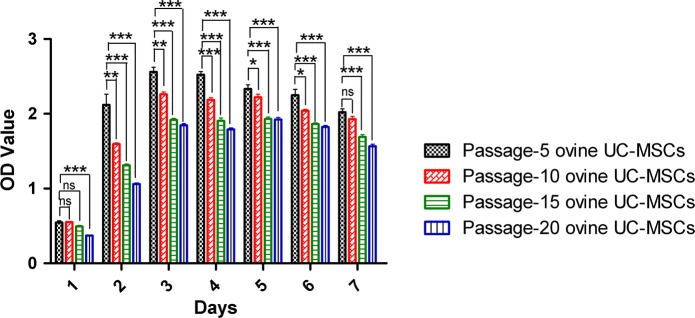

Proliferation ability of ovine UC-MSCs in vitro

Ovine UC-MSCs at passage 5, 10, 15 and 20 were seeded into 96-well plates at same densities and assessed for proliferation ability over 7 days. The results showed that on 3rd day ovine UC-MSCs had strongest proliferation ability at passage 5, 10, 15 and 20. It is demonstrated that the doubling times of ovine UC-MSCs were every 3rd day at passage 5 through to passage 20, with the most rapid proliferation occurring in passage 5 cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proliferation ability of ovine UC-MSCs. Histograms reflect the proliferation of different passage numbers of ovine UC-MSCs over 7 days. OD values represent cell vitality. Different phase colors represent different passages of ovine UC-MSCs (ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0001)

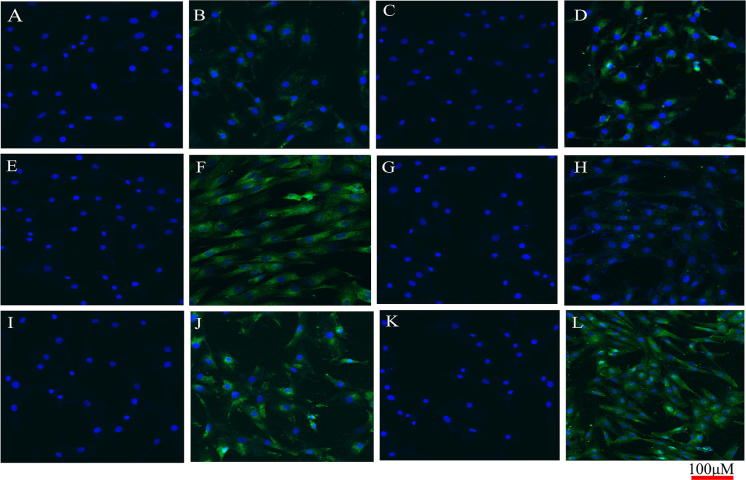

Immunophenotype of ovine UC-MSCs

To characterize ovine UC-MSCs, expression of mesenchymal and hematopoietic lineage markers were detected by immunofluorescence analysis. The results showed that compare to control group (a, c, e, g, h) (Fig. 3), ovine UC-MSCs were positive for CD29 (b), CD13 (d), CD44 (f), CD90 (j), CD106 (l), and negative for leukocyte common antigen CD45 (h) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of ovine UC-MSCs surface markers. a, c, e, g, i, k Control group which only cultured in GM and not stained with antibodies. Counterstaining of nuclei was carried out by DAPI (blue), b stained with CD29 antibody, d stained with CD13 antibody, f stained with CD44 antibody, h stained with CD45 antibody, j stained with CD90 antibody, l stained with CD106. Counterstaining of nuclei was carried out by DAPI (blue). All representative samples are shown at × 100 magnification

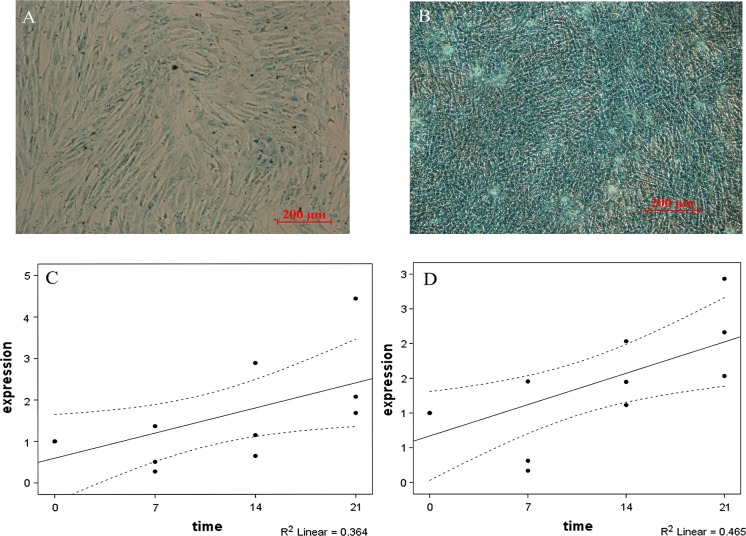

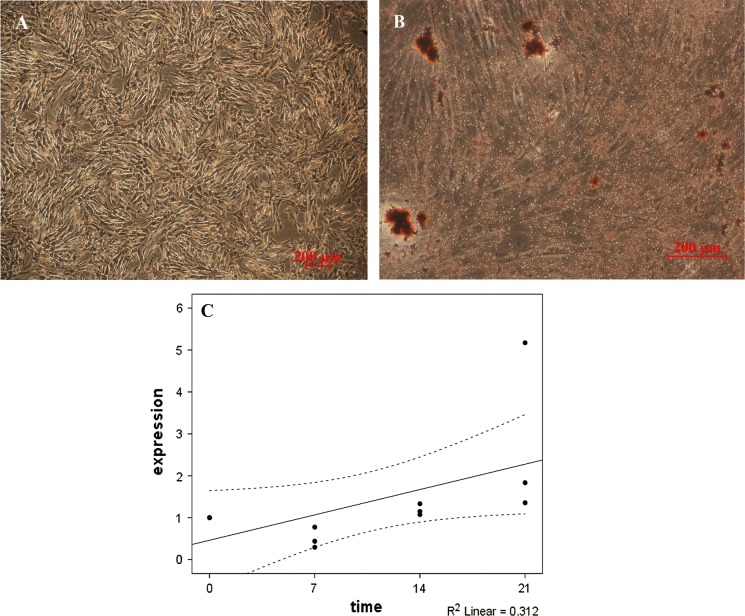

Chondrogenic differentiation

After cultured in chondrogenic differentiation medium for 21 days, ovine UC-MSCs showed a multilayer matrix-rich morphology and formed chondrogenic pellets (Fig. 4a, b). We discovered that differentiated cells were positive for acid mucopolysaccharides, which can be found through staining Alcian blue in differentiated cells. Both biglycan (BGN) and lumican (LUM) chondrogenic differentiation markers were highly expressed at days 7, 14, and 21 compared with the control cells. Expression levels of BGN and LUM genes were up-regulated in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Chondrogenic differentiation of ovine UC-MSCs. a Ovine UC-MSCs were maintained in GM. b After cultured in chondrogenic differentiation medium for 21 days, Ovine UC-MSCs were stained with Alcian blue to detect osteogenic differentiation. c During chondrogenic differentiation, an increased level of BGN gene expression was observed at 7, 14, and 21 days (0 days considered as control) as assessed by RT-qPCR. d Over time (7, 14, and 21 days), up-regulation of LUM gene expression was detected. Statistically significant differences between differentiated and control cells were determined by Pearson correlation test (BGN; r = 0.603**, LUm; r = 0.681*, *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01). (Color figure online)

Osteogenic differentiation

Culture of UC-MSCs in osteogenic induction medium stimulated the spindle-shaped cells to flatten and broaden. After staining with silver nitrate (AgNO3), characteristic calcium phosphated eposits were visible after 21 days (Fig. 5a, b).This change in morphology was not observed in the control cells. Determination of osteogenic differentiation genes revealed that the level of bone gamma-carboxyglutamate (gla) protein, or osteocalcin (BGLAP), was significantly up-regulated in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Osteogenic differentiation of ovine UC-MSCs. Ovine UC-MSCs cultured in the a absence and b presence of osteo-inductive media for 3 weeks, showing positive AgNO3 staining. c BGLAP gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR at 7, 14, 21 days of differentiation. Statistically significant differences between differentiated and control cells were determined by Pearson correlation test (BGLAP; r = 0.713**)

Adipogenic differentiation

Ovine UC-MSC adipogenic differentiation was perceived by significant changes in morphology and spontaneous small lipid droplets formation, identified by oil red O staining (Fig. 6a, b). Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), the gene specifically expressed in adipocytes, was found expressed in differentiation period (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Adipogenic differentiation of ovine UC-MSCs. Ovine UC-MSCs cultured in the a absence and b presence of chondrogenic media for 3 weeks, showing Oil Red O staining. c SCD gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR at 7, 14, and 21 days. SCD gene expression increased in a time-dependent manner, peaking at day 21. Statically significant differences between differentiated and control cells were determined by Pearson correlation test (SCD; r = 0.558)

Discussion

Ovine MSCs have been isolated from several sources, including bone marrow, peripheral blood, liver, adipose tissue, and amniotic fluid (McCarty et al. 2009; Lyahyai et al. 2012; Heidari et al. 2013; Fei et al. 2013). Here in, we describe for the first time the isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential of MSCs obtained from ovine umbilical cord tissue.

Plastic adherence is one of the most obvious characteristics of MSCs. Our study showed that ovine UC-MSCs adhered to plastic and displayed a fibroblastic-like morphology, similar to those reported from other species, including goat (Silva Filho et al. 2014), equine (Vidal et al. 2012), bovine (Cortes et al. 2013), and human (Lu et al. 2006). Rentsch et al. (2010) reported that ovine BM-MSC proliferated after Day 10 no more. However, our study demonstrated that after Day 5, the cell number of ovine UC-MSC didn’t increase in culture. The discrimination of growth characteristic between ovine BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs might result from the different sources.

Surface markers are another standard method to identify MSCs. Our study demonstrated that ovine UC-MSCs were positive for CD29, CD44, CD90, CD13, CD106, and negative for the hematopoietic cell marker CD45, which corresponds to the MSC surface markers specified by the Tissue Stem Cell Committee from the International Society for Cellular Therapy (Dominici et al. 2006). Among these surface antigens, CD29 and CD44 were reported to be uniformly expressed on ovine MSCs from different tissue sources (Godoy et al. 2014). Compared to human UC-MSCs, which display surface markers CD13, CD29 (integrin β1), and CD90 (Thy-1), but not CD45, our report showed that there was no significant difference between human and ovine UC-MSCs.

During osteogenic differentiation, calcium phosphate deposition and osteogenic-specific gene expression were tested. BGLAP is a bone-specific gene required for matrix mineralization (Hauschka et al. 1989; Ryoo et al. 1997; Hoffmann et al. 1994). Alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin are known to be upregulated during human BM-MSC osteogenic differentiation (Açil et al. 2014). In ovine UB-MSCs, BGLAP was found to be up-regulatedand maximally expressed at day 21. Analogously, during the process of mouse adipose tissue-derived MSC osteogenic differentiation, BGLAP was detected only in differentiated cells (Teotia et al. 2013). Consisted with our research, other studies on ovine MSCs also report expression of osteocalcin (Niemeyer et al. 2010; Boos et al. 2011).

During the process of ovine UC-MSC adipogenic differentiation, lipid droplet formation and adipocyte-related markers were detected. SCD is uniquely expressed in adipocytes and plays a key role in cellular metabolism by catalyzing rate-limiting enzymes in the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (Kim and Ntambi 1996). During the process of adipogenesis, expression of SCD was found to be up-regulated in ovine UC-MSCs. It has previously been demonstrated that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) might play a key role in adipogenesis by binding to the enhancer of adipocyte-specific genes, such as lipoprotein lipase(LPL), leptin, fatty acid binding protein, and the adipocyte P2 gene (aP2) (Rosen and Spiegelman 2001; Tontonoz et al. 1994).

Chondrogenic differentiation was confirmed positive by staining Alcian blue and it also showed that BGN and LUM genes were highly expressed. BGN, a member of the small leucine repeat proteoglycan family (SLRP), was localized on the X chromosome (Wadhwa et al. 2004). Bianco et al. (1990) found that BGN was highly expressed in cartilaginous and bony components of developing bones. LUM also is member of the SLRP family, with high expression levels reported in adult articular chondrocytes (Kao et al. 2006; Judy et al. 1995).

Recently, more ovine MSC tissue sources have been reported. However, there has been no report on ovine UC-MSCs. Our research has demonstrated the existence of umbilical cord-derived MSCs in sheep, which have been characterized based on cell morphology, proliferation potential, specific surface marker expression, and tri-lineage differentiation capacity. Our study shows that the main characteristics of ovine UC-MSCs are consisted with ovine MSCs derived from other tissues (Rentsch et al. 2010; Ando et al. 2012; Gruber et al. 2011; Barker and Wagner 2003; In't Anker et al. 2004).We believe that umbilical cord tissue is a valuable source of ovine MSCs.

Conclusions

In this study, we have described the isolation of abundant MSCs from ovine umbilical cord. Ovine UC-MSCs proliferated rapidly, expressed characteristic MSC surface markers, and retained the ability of differentiation into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31101698) and the Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars Development (No. 2011JQ03). We are grateful to all who contributed to this work at the Department of Biology of Inner Mongolia University.

Author’s contributions

The experiment was designed by PL and DL, performed and analyzed by SZ, LT, YT, and DT. The manuscript was written by SZ and PL.

Complain with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sirguleng Zhao and Li Tao have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Pengxia Liu, Email: liupengxia@imu.edu.cn.

Dongjun Liu, Email: nmliudongjun@sina.com.

References

- Açil Y, Ghoniem AA, Wiltfang J, Gierloff M. Optimizing the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells by the synergistic action of growth factors. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando W, Heard BJ, Chung M, Nakamura N, Frank CB, Hart DA. Ovine synovial membrane-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells retain the phenotype of the original tissue that was exposed to in vivo inflammation: evidence for a suppressed chondrogenic differentiation potential of the cells. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:599–608. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JN, Wagner JE. Umbilical-cord blood transplantation for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:526–532. doi: 10.1038/nrc1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P, Fisher LW, Young MF, Termine JD, Robey PG. Expression and localization of the two small proteoglycans biglycan and decorin in developing human skeletal and non-skeletal tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1549–1563. doi: 10.1177/38.11.2212616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos AM, Loew JS, Deschler G, Arkudas A, Bleiziffer O, Gulle H, Dragu A, Kneser U, Horch RE, Beier JP. Directly auto-transplanted mesenchymal stem cells induce bone formation in a ceramic bone substitute in an ectopic sheep model. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1364–1378. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Mesenchymal stem cells: building blocks for molecular medicine in the 21st century. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:259–263. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes Y, Ojeda M, Araya D, Dueñas F, Fernández MS, Peralta OA. Isolation and multilineage differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from abattoir-derived bovine fetuses. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9:133. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Dj Prockop, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farini A, Sitzia C, Erratico S, Meregalli M, Torrente Y. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells in chronic diseases. Stem Cells Int. 2014;2014:306573. doi: 10.1155/2014/306573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei X, Jiang S, Zhang S, Li Y, Ge J, He B, Goldstein S, Ruiz G. Isolation, culture, and identification of amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;67:689–694. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong CY, Richards M, Manasi N, Biswas A, Bongso A. Comparative growth behaviour and characterization of stem cells from human Wharton’s jelly. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15:708–718. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong CY, Chak LL, Biswas A, Tan JH, Gauthaman K, Chan WK, Bongso A. Human Wharton’s Jelly stem cells have unique transcriptome profiles compared to human embryonic stem cells and other mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Mar. 2011;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy RF, Alves AL, Gibson AJ, Lima EM, Goodship AE. Do progenitor cells from different tissue have the same phenotype. Res Vet Sci. 2014;96:454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber HE, Somayaji S, Riley F, Hoelscher GL, Norton HJ, Ingram J, Hanley EN., Jr Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: serial passaging, doubling time and cell senescence. Biotech Histochem. 2011;87:303–311. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2011.649785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschka PV, Lian JB, Cole DE, Gundberg CM. Osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein: vitamin K-dependent proteins in bone. Physiol Rev. 1989;69(3):990–1047. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari B, Shirazi A, Akhondi MM, Hassanpour H, Behzadi B, Naderi MM, Sarvari A, Borjian S. Comparison of proliferative and multilineage differentiation potential of sheep mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, liver, and adipose tissue. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2013;5:104–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann HM, Catron KM, van Wijnen AJ, McCabe LR, Lian JB, Stein GS, Stein JL. Transcriptional control of the tissue-specific, developmentally regulated osteocalcin gene requires a binding motif for the Msx family of homeodomain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12887–12891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JY, Fu YS, Chang SJ, Tsuang YH, Wang HW. Functional module analysis reveals differential osteogenic and stemness potentials in human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and Wharton’s jelly of umbilical cord. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1895–1910. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In't Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, de Groot-Swings GMJS, Claas FHJ, Fibbe WE, Kanhai HHH. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1338–1345. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy G, Chen XN, Julie RK, Peter JR. The human lumican gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21942–21949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WW, Funderburgh JL, Xia Y, Liu CY, Conrad GW. Focus on molecules: lumican. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Ntambi JM. Regulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase genes: role in cellular metabolism and preadipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;266:1–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Ringdén O. Mesenchymal stem cells: properties and role in clinical bone marrow transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Han ZC. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology and clinical potential in type 1 diabetes therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:1155–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LL, Liu YJ, Yang SG, Zhao QJ, Wang X, Gong W, Han ZB, Xu ZS, Lu YX, Liu D, Chen ZZ, Han ZC. Isolation and characterization of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells with hematopoiesis-supportive function and other potentials. Haematologica. 2006;91:1017–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyahyai J, Mediano DR, Ranera B, Sanz A, Remacha AR, Bolea R, Zaragoza P, Rodellar C, Martín-Burriel I. Isolation and characterization of ovine mesenchymal stem cells derived from peripheral blood. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8:169. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty RC, Gronthos S, Zannettino AC, Foster BK, Xian CJ. Characterisation and developmental potential of ovine bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:324–333. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Z, Jin J, Chen L, Zhu J, Huang W, Zhao J, Qian H, Zhang X. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from human placenta: comparison with human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer P, Fechner K, Milz S, Richter W, Suedkamp NP, Mehlhorn AT, et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue for bone regeneration in a critical size defect of the sheep tibia and the influence of platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3572–3579. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch C, Hess R, Rentsch B, Hofmann A, Manthey S, Scharnweber D, Biewener A, Zwipp H. Ovine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and characterization of the cells and their osteogenic differentiation potential on embroidered and surface-modified polycaprolactone-co-lactide scaffold in vitro cell. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2010;46:624–634. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. PPARγ: a nuclear regulator of metabolism, differentiation, and cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37731–37734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HM, Hoffmann HM, Beumer T, Frenkel B, Towler DA, Stein GS, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB. Stage-specific expression of Dlx-5 during osteoblast differentiation: involvement in regulation of osteocalcin gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1681–1694. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Filho OF, Argôlo Neto NM, Carvalho MA, Carvalho YK, Diniz Ad, Moura Lda S, Ambrósio CE, Monteiro JM, Almeida HM, Miglino MA, Alves Jde J, Macedo KV, Rocha AR, Feitosa ML, Alves FR. Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal progenitors derived from the bone marrow of goats native from northeastern Brazil. Acta Cir Bras. 2014;29:478–484. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502014000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teotia PK, Hussein KE, Park KM, Hong SH, Park SM, Park IC, Yang SR, Woo HM. Mouse adipose tissue-derived adult stem cells expressed osteogenic specific transcripts of osteocalcin and parathyroid hormone receptor during osteogenesis. Transp Proc. 2013;45:3102–3107. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. PPARγ2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–1234. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal MA, Walker NJ, Napoli E, Borjesson DL. Evaluation of senescence in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from equine bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:273–283. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa S, Embree MC, Bi Y, Young MF. Regulation, regulatory activities, and function of biglycan. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2004;14:301–315. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.v14.i4.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]