Abstract

Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) can be produced by microorganisms from renewable resources and is regarded as a promising bioplastic to replace petroleum-based plastics. Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 is a medium-chain-length PHA (mcl-PHA)-producing strain and its whole-genome sequence is currently available. The yield of mcl-PHA in P. mendocina NK-01 is expected to be improved by applying a promoter engineering strategy. However, a limited number of well-characterized promoters has greatly restricted the application of promoter engineering for increasing the yield of mcl-PHA in P. mendocina NK-01. In this work, 10 endogenous promoters from P. mendocina NK-01 were identified based on RNA-seq and promoter prediction results. Subsequently, 10 putative promoters were characterized for their strength through the expression of a reporter gene gfp. As a result, five strong promoters designated as P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 were identified based on transcriptional level and GFP fluorescence intensity measurements. To evaluate whether the screened promoters can be used to enhance transcription of PHA synthase gene (phaC), the three promoters P4, P6 and P16 were separately integrated into upstream of the phaC operon in the genome of P. mendocina NK-01, resulting in the recombinant strains NKU-4C1, NKU-6C1 and NKU-16C1. As expected, the transcriptional levels of phaC1 and phaC2 in the recombinant strains were increased as shown by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. The phaZ gene encoding PHA depolymerase was further deleted to construct the recombinant strains NKU-∆phaZ-4C1, NKU-∆phaZ-6C1 and NKU-∆phaZ-16C1. The results from shake-flask fermentation indicated that the mcl-PHA titer of recombinant strain NKU-∆phaZ-16C1 was increased from 17 to 23 wt% compared with strain NKU-∆phaZ. This work provides a feasible method to discover strong promoters in P. mendocina NK-01 and highlights the potential of the screened endogenous strong promoters for metabolic engineering of P. mendocina NK-01 to increase the yield of mcl-PHA.

Introduction

Currently, promoter engineering can serve as a powerful tool for rational tuning of the activity of the synthetic pathway enzymes for overproduction of many important bio-based chemicals1–5. Although various promoters may be obtained by construction and screening of promoter libraries6–8, library construction is a labor- and time-consuming task and screening of different promoters from libraries is inefficient. Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) has provided an alternative strategy for the discovery of different types of endogenous promoters.

Microbial genomes are regarded as huge reservoirs for a variety of candidate endogenous promoters for metabolic pathway engineering. So far, a number of candidate endogenous promoters predicted by combination of RNA-seq and reporter gene assay have been applied for metabolic pathway optimization to improve the yield of target products. For example, 166 putative endogenous constitutive promoters from Streptomyces coelicolor M145 were predicted by RNA-seq, eight of which were further characterized by a reporter gene gfp, and four characterized promoters with different strengths were applied for the activation of cryptic biosynthetic clusters and resulted in different levels of the production of jadomycin B in S. venezuelae ISP52309. In another study, 32 candidate endogenous promoters from S. albus J1074 were predicted by RNA-seq analysis, among which 10 strong promoters and four constitutive promoters were identified using a streptomycete reporter gene, xylE, and used for successful activation of a cryptic gene cluster from S. griseus in three widely used Streptomyces strains10. Song et al.11 identified a panel of stress-activated endogenous promoters by measuring the strengths of 84 predicted promoter sequences with a reporter gene gfp under specific stress conditions, and selected promoters elevated the final production of both cytoplasmic β-galactosidase and secreted protein α-amylase. In addition, six endogenous promoters from Rhodotorula toruloides were identified by luciferase reporter assay, among which three strong promoters were applied for overexpression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase for enhancing lipid accumulation in R. toruloides12. Yang et al.13 identified four classes of phase-dependent promoters with different strengths from 114 Bacillus subtilis endogenous promoters based on the database DBTBS and GFP reporter assay and the characterized phase-dependent promoters were applied for secretory expression of enzymes. In 2017, 104 native promoter-5′-UTR complexes (PUTR) which were screened from Escherichia coli based on a series of RNA-seq data were characterized by a reporter gene gfp and four engineered PUTRs showed stronger activities than the PBAD promoter14.

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) are a family of biopolyesters synthesized by bacteria and archaea that accumulate as intracellular storage reserves of carbon and energy under the unbalanced growth conditions15. PHAs have attracted considerable attention as potential candidates to replace some oil-based plastics because of their biodegradability, biocompatibility, thermal and mechanical properties similar to plastics, and capability of being produced from renewable resources16. PHAs are traditionally classified into two major types, i.e., short-chain-length PHAs (scl-PHA) consisting of monomer repeat units of 3 to 5 carbon atoms and medium-chain-length PHAs (mcl-PHA) consisting of monomer repeat units of 6 to 14 carbon atoms.

Many members from the genus Pseudomonas have an ability to synthesize mcl-PHA via either fatty acid de novo biosynthesis pathway from unrelated carbon sources (e.g., glucose and glycerol) or β-oxidation pathway from related carbon sources (e.g., fatty acids)17–20. Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01, which was isolated by our lab from farmland soil, can synthesize mcl-PHA and alginate oligosaccharides (AO) simultaneously from glucose and the PHA synthase operon in this strain comprises two class II synthase genes phaC1 and phaC2 linked by a PHA depolymerase gene phaZ21,22. The mcl-PHA synthesized by P. mendocina NK-01 possesses superior physical properties and special monomer compositions23.

To date, whole-genome sequencing of P. mendocina NK-01 has been completed24 and a genome editing system has been developed for P. mendocina NK-0125, which have paved the way for metabolic pathway engineering of P. mendocina NK-01. In this work, five endogenous promoters from P. mendocina NK-01 were identified based on RNA-seq analysis, promoter prediction and GFP reporter assay, three of which were used to enhance transcription of phaC by integrating each promoter into the genome of P. mendocina NK-01. When combined with deletion of phaZ, the recombinant strain NKU-∆phaZ-16C1 had a 6% increase in mcl-PHA titer compared with NKU-∆phaZ.

Results and Discussion

Screening of endogenous strong promoters from P. mendocina NK-01 via RNA-seq analysis and promoter prediction

For RNA-seq analysis, transcriptional level of a gene is positively correlated with RPKM value26. Through RNA-seq analysis of P. mendocina NK-01, transcriptional levels of all genes were ranked from high to low based on their RPKM values. The first 30 genes ranked by RPKM values were assumed to be highly active at the transcriptional level (Table S1). Thus, the upstream regions of the 30 genes with high RPKM values were selected as the detection targets for promoter prediction. Through further screening using an online promoter prediction software, 10 out of 30 candidate sequences were identified as the putative promoter sequences (Fig. S1) and selected for subsequent cloning and characterization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selection of the 10 highly expressed genes in RNA-seq for promoter cloning.

| Gene ID | Productions | Promoters | Length of promoters (bp) | RPKM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS_2118 | hypothetical protein | P4 | 423 | 24593.43 |

| MDS_0756 | hypothetical protein | P6 | 261 | 24066.04 |

| MDS_3450 | hypothetical protein | P9 | 177 | 16182.31 |

| MDS_2531 | alcohol dehydrogenase | P16 | 199 | 8949.33 |

| MDS_0957 | ribosome-associated translation inhibitor RaiA | P17 | 85 | 8412.46 |

| MDS_0563 | poly(hydroxyalkanoate) granule-associated protein | P18 | 183 | 8222.26 |

| MDS_1497 | 17 kDa surface antigen/outer membrane lipoprotein | P20 | 102 | 7267.13 |

| MDS_1161 | arginine/ornithine antiporter | P23 | 394 | 6935.83 |

| MDS_4257 | outer membrane protein W | P25 | 178 | 6637.68 |

| MDS_3908 | transport-associated protein | P29 | 419 | 5888.12 |

Cloning of strong promoters from P. mendocina NK-01

The promoter regions of the 10 highly expressed genes were PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of P. mendocina NK-01. To obtain the intact promoter sequence of each of the 10 highly expressed genes, in this work, the entire intergenic region between the highly expressed gene and its upstream gene was selected as the target region to be cloned by PCR, except for the native ribosomal binding site (RBS). The results from DNA sequencing showed that the cloned DNA fragments coincided with the selected intergenic regions at the nucleotide level (data not shown).

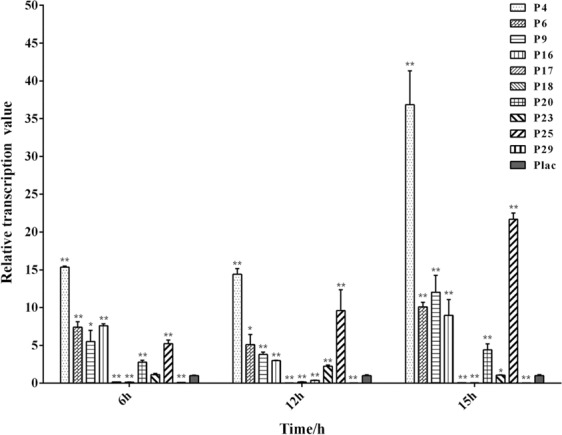

Characterization of the cloned promoters via qPCR

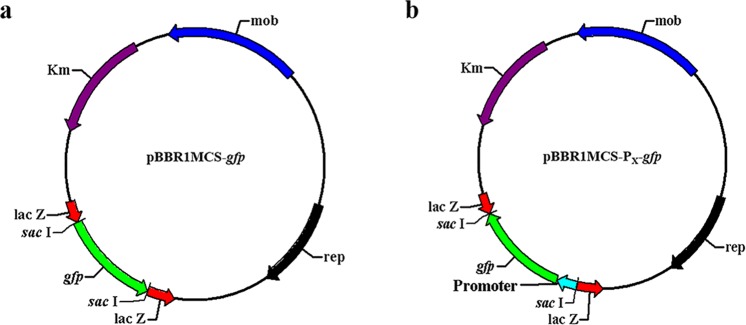

To assess the strengths of the cloned promoters, the promoters sequences were fused to the 5′-end of the amplified gfp gene and then inserted into a broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS-2 able to replicate in various gram-negative bacteria27 using homologous recombination (Fig. 1). qPCR was employed for the analysis of transcriptional levels of gfp under different promoters at different growth phases, i.e., early log-phase (6 h), post log-phase (12 h) and stationary phase (15 h) (Fig. S2). Among the 10 tested promoters, the transcriptional levels of the five promoters P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 were much higher than that of lac promoter at different growth phases. Compared with lac promoter, the strongest promoter P4 showed a 36-fold increase in the transcriptional activity at the stationary phase (Fig. 2). When detecting with most of the cloned promoters, the transcriptional levels of reporter gene gfp varied significantly at different growth phases. The five strong promoters P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 had higher transcriptional levels in post log-phase than stationary phase or early log-phase (Fig. S3). In contrast, relatively minor differences in transcriptional levels were detected with the five strong promoters between stationary phase and early log-phase (Fig. S3). The promoter P16 had a relatively stable transcriptional activity throughout the growth period (Fig. S3). In previous studies, different types of promoters including strong promoters, growth phase-dependent promoters and constitutive promoters have been well characterized10,13. Because of good system compatibility with the host cell, the selection of endogenous promoters may be more practical and purposeful for their applications in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering of the host itself.

Figure 1.

Recombinant plasmids for promoter characterization with gfp as a reporter gene. (a) Recombinant plasmid with a lac promoter as a control. (b) Recombinant plasmids for characterizing the strengths of 10 selected endogenous promoters.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the chosen promoters and lac promoter via qPCR analysis. Transcription of gfp gene under different promoters in P. mendocina NKU was quantified at different growth phases. 16S rDNA gene was used as internal reference. The relative transcription value of gfp gene under lac promoter was set as 1. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments. A Student’s t-test was performed between lac promoter and chosen promoters. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

The promoters P17, P18, and P29 had high RPKM values in the RNA-seq analysis, but the promoters placed on plasmid exhibited lower transcriptional levels than lac promoter at any growth phase (Fig. 2). The chosen endogenous promoters function well in the genome, which might be attributed to the assistance of the nearby regulatory sequences. Once the promoters were cloned separately, they did not work well.

Since the screened endogenous promoters were expected to be used for improving PHA production, the RNA-seq data were obtained with P. mendocina grown in PHA fermentation medium. For characterization of the cloned promoters by a reporter gene assay, the commonly used LB medium for the various reporter gene assays was also selected for this study11,13. The well-characterized promoters in LB medium may also have the potential to be applied for the synthesis of other products in P. mendocina. However, the transcriptional levels of the 10 candidate promoters obtained by RNA-seq analysis may not always be consistent with the transcriptional levels measured by qPCR due to the different culture conditions. For example, the promoters P17, P18 and P29 had high RPKM values in the RNA-seq analysis, but they exhibited lower transcriptional levels in the reporter gene assay than lac promoter at any growth phase. In the future, more RNA-seq data based on different culture conditions should be overall considered to select the candidate promoters. Then, through characterization of the putative promoters by a reporter gene assay in LB medium, the screened strong endogenous promoters may have a wide-range application for various products in P. mendocina.

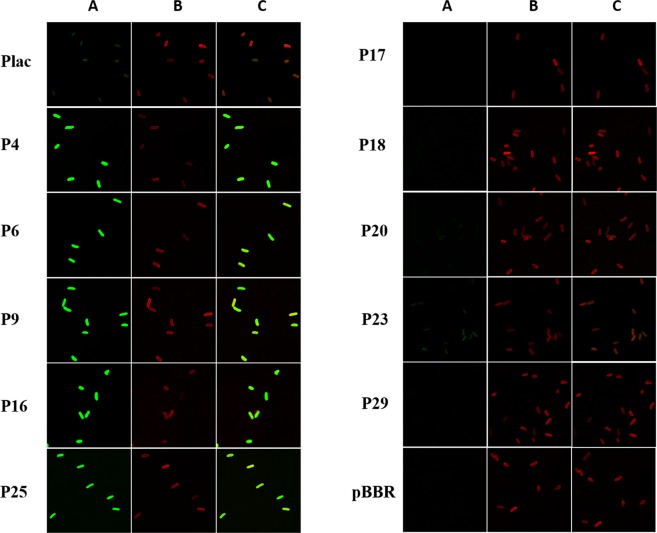

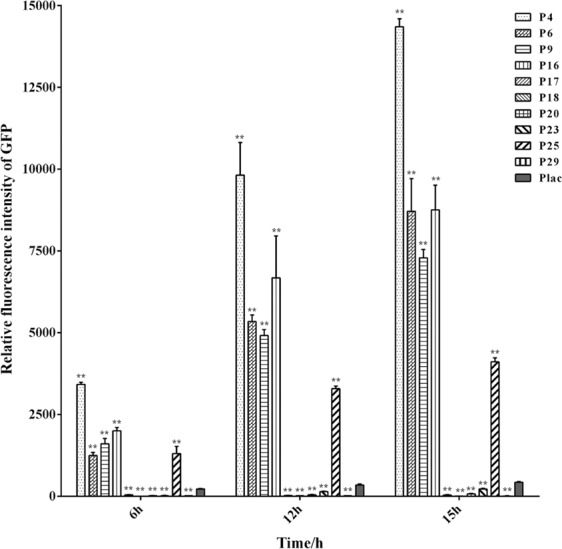

Characterization of the cloned promoters via GFP fluorescence measurement

To further determine the expression levels of the selected endogenous promoters, relative fluorescence intensities were measured at three different growth phases. As shown in Fig. 3, the five strong promoters P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 characterized by qPCR had also higher relative fluorescence intensities than lac promoter at any growth phase. P4 had the strongest relative fluorescence intensity among the 10 selected promoters, which showed a nearly 32-fold enhancement compared with lac promoter at the stationary phase. For each of the above five strong promoters, significant difference in the intensity of GFP fluorescence was observed at different growth stages, which was in agreement with the previous results on the unstable transcriptional levels of gfp measured by qPCR (Fig. S3). All of the results suggest that the expression levels of the five strong promoters might not be constant over the entire growth cycle (Fig. 3), The orders of promoter strength reflected by the real-time qPCR and GFP reporter were identical to the result obtained by RNA-seq (RPKM value), which demonstrated that the results of transcriptome sequencing analysis and functional validation experiments were highly consistent.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the chosen promoters and lac promoter via GFP fluorescence intensity measurements. Expression of gfp gene under different promoters in P. mendocina NKU was quantified at different growth phases. The background expression was subtracted, and the relative fluorescence intensity was calculated by normalization against per OD600 of whole cells. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments. A Student’s t-test was performed between lac promoter and chosen promoters. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Interestingly, the relative transcriptional level of P25 was higher than that of P6, P9 and P16 (Fig. 2), but the relative fluorescence intensity of P25 was lower than that of P6, P9 and P16 (Fig. 3). The relative fluorescence intensities of the remaining promoters P17, P18, P20, P23 and P29 were lower than that of lac promoter at any growth phase, although P20 and P23 showed higher transcriptional levels than lac promoter. The observations suggest that the high transcriptional level of a gene might not necessarily lead to the high-level synthesis of this protein encoded by the gene. To maintain the consistency of translation initiation efficiency, in this study, the same RBS was introduced into upstream of reporter gene gfp. Among the reporter gene vectors, the distance between the predicted promoter sequences and RBS was different from each other, which may affect the efficiency of mRNA translation, possibly leading to the discrepancy between the transcriptional level and fluorescence intensity. For example, the distance between the predicted promoter sequences and RBS for P25 were longer than that for P6, P9 and P16. This may be the reason why P25 had higher transcriptional level, but lower fluorescence intensity than those of P6, P9 and P16. In addition, the differences in the spacer sequences between promoter and RBS may be the second reason for the different trends between the transcriptional level and fluorescence intensity.

When observed by confocal microscopy, cells expressing gfp under the control of P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 produced more bright green fluorescence than the control cells with gfp expression under the control of lac. Cells produced weak green fluorescence when gfp expression was driven by P23 and P20. However, green fluorescence was not observed on the cells when expression of gfp was under the control of P17, P18 and P29 (Fig. 4). The results from confocal microscope matched well with that from GFP fluorescence intensity measurement.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the chosen promoters and lac promoter via confocal microscope. (A) Green fluorescence within the cell. (B) Outline of cell membrane by stain with FM4-64/L. (C) A and B merged together. All the images were taken at the same exposure condition.

In a previous study, a set of synthetic promoters, which is capable of stable and constitutive expression of downstream genes, was applied for calibrated heterologous gene expression in P. putida KT2440 using a mini-Tn7 delivery transposon vector that inserts the promoters into the genome of P. putida28. In another study, different inducible promoters were characterized by the construction of ProUSER-reporter vectors for use in P. putida KT2440, and the production of p-coumaric acid in P. putida KT2440 was enhanced by the use of selected inducible promoters for the optimization of pathway expression29. In this work, the five endogenous strong promoters P4, P6, P9, P16 and P25 were identified from P. mendocina NK-01 using a pipeline consisting of RNA-seq analysis and transcriptional level and fluorescence intensity measurements of a reporter gene gfp. So far, very little is known about the screening of strong promoters from the genus Pseudomonas using a RNA-seq-based strategy.

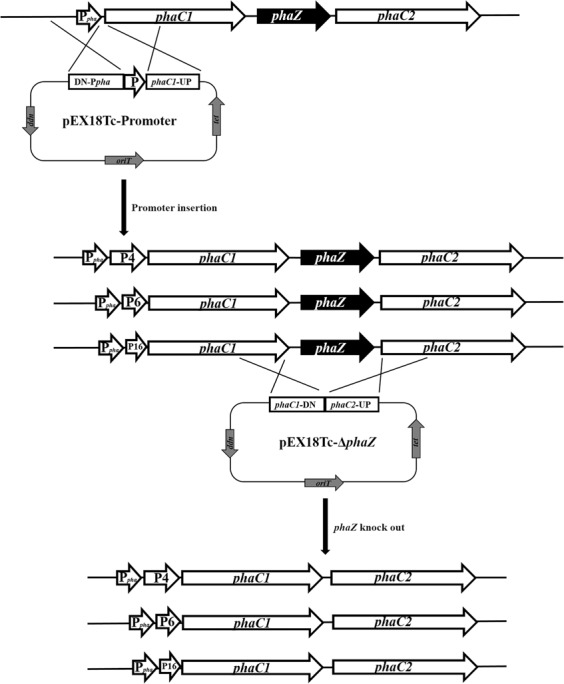

Enhanced production of PHA by overexpressing phaC using the strong promoters in P. mendocina NKU

The mcl-PHA synthetic operon of P. mendocina NK-01 had been expounded in the earlier research. Our study has shown that PhaC1 is the main contributor to mcl-PHA synthesis in P. mendocina NK-0123. Consequently, overexpressing PHA synthase genes, especially the phaC1 gene, may have a positive influence on mcl-PHA accumulation. The Standard European Vector Architecture Database (SEVA) has developed a series of plasmid vectors for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology in Pseudomonas and other gram-negative bacteria30,31. However, plasmid expression systems tend to be a burden on the bacteria, especially when multiple genes are needed to be co-expressed in a bacterium. In this work, the 3 endogenous strong promoters P4, P6 and P16 were selected for overexpressing PHA synthase genes by unmarked insertion of promoters upstream of the phaC1 gene in the genome of P. mendocina NKU. This process did not leave any redundant sequences in the genome except the inserted promoter sequences (Fig. 5). This scarless genome editing strategy may confer some advantages over plasmid-borne overexpression of phaC genes.

Figure 5.

The construction schematic diagram for inserting the promoters into upstream of phaC1 gene and for knockout of phaZ in the genome of P. mendocina NKU.

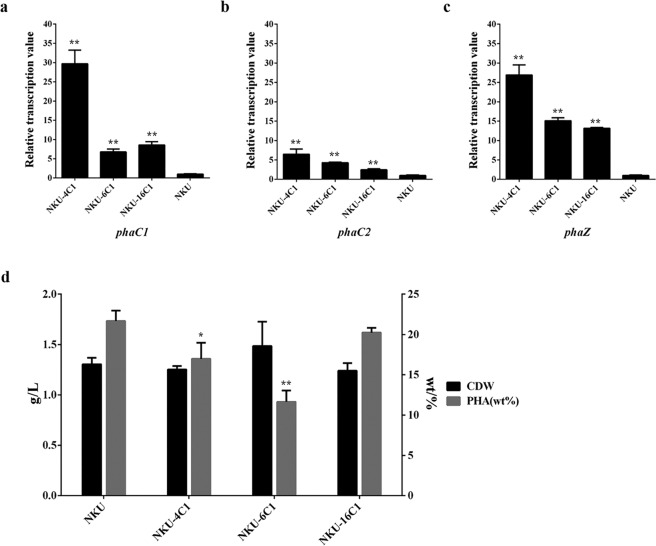

Through chromosomal insertion of the 3 endogenous strong promoters P4, P6 and P16, the transcriptional levels of phaC1 and phaC2 in the recombinant strains NKU-4C1, NKU-6C1 and NKU-16C1 were all improved compared with strain NKU. In particular, phaC1 showed a more obvious improvement than phaC2 (Fig. 6). This may be due to the fact that phaC1 is closer to the inserted promoters than phaC2.

Figure 6.

qPCR analysis and PHA fermentation results for the strains NKU-4C1, NKU-6C1, NKU-16C1 and NKU. Transcriptional levels of phaC1 (a), phaC2 (b) and phaZ (c) for the different strains. (d) Cell dry weight (CDW) and PHA production for the strains. Samples for qPCR were taken at 36 h of PHA fermentation. The transcriptional level for strain NKU was set as 1. wt% was defined as the ratio of PHA to CDW. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments. A Student’s t-test was performed between NKU and the mutants. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Moreover, the phaZ located between phaC1 and phaC2 had high transcriptional levels in the recombinant strains. Especially for NKU-6C1 and NKU-16C1, the transcriptional levels of phaZ were improved even more than phaC1, even though phaZ was far from the promoter in the gene cluster when compared to phaC1. This could because of that tight regulatory coupling between PHA polymerase activity and depolymerase activity may exist in this strain. It had been reported that single overexpression of PhaC may lead to an increase in the expression of PhaZ32. So phaZ showed a higher transcriptional level than phaC1, when PhaC and PhaZ were overexpressed simultaneously in a gene cluster. The PHA fermentation results showed that the PHA titers of NKU-4C1, NKU-6C1 and NKU-16C1 were all reduced, especially in NKU-6C1 (Fig. 6). These observations suggest that the overexpression of phaZ may lead to excessive synthesis of PHA depolymerase, and that the intracellularly accumulated PHA may be degraded by the depolymerase. The regulatory roles of PHA depolymerase in the synthesis of PHA were investigated previously by other researchers. For example, overexpression of PhaC2 alone in P. putida strain U was unable to accumulate higher amounts of PHA than in the wild-type strain, as a result of elevated PHA depolymerization in the late stage of PHA synthesis. A phaZ-inactive mutant of P. putida strain U, however, accumulated higher levels of PHA than the parental strain32. The mcl-PHA content of a phaZ knockout mutant of P. putida KT2442 (86 wt%, the ratio of PHA to CDW) was higher than that of wild-type strain (66 wt%) when using sodium octanoate as the carbon source33. However, the elimination of PHA depolymerase activity in P. putida KT2440 had little impact on the overall yield of PHA34. Both a phaZ-deficient mutant of P. oleovorans GPo135 and two transposon-disrupted phaZ mutants of P. resinovorans36 did not show any substantial increase in PHA titer under various PHA synthesis conditions.

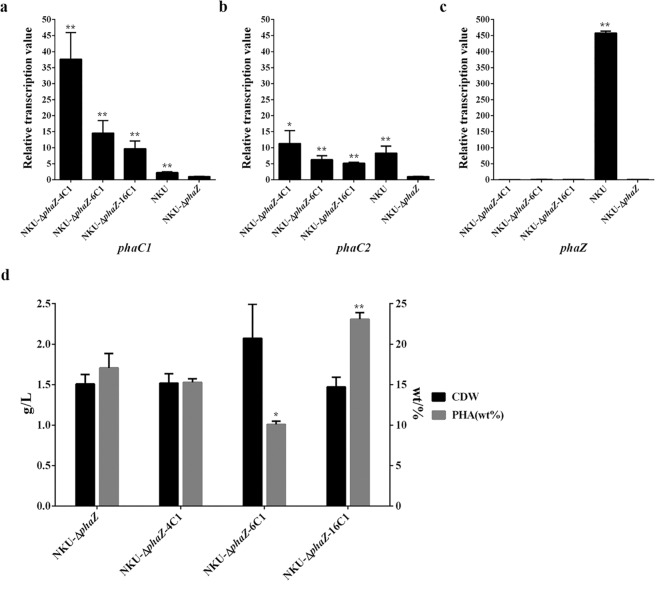

In this work, we attempt to improve the yield of PHA by the construction of phaZ knockout mutants. However, the PHA titer of strain NKU-phaZ was decreased by 4 wt% compared with strain NKU from 21 to 17 wt% (Fig. 7), indicating that knockout of phaZ cannot improve the yield and molecular weight of mcl-PHA in P. mendocina NK-01. Surprisingly, PHA synthesized by all phaZ knockout mutants had lower molecular weights than PHA synthesized by the parent strain NKU, with an exception of NKU-phaZ-6C1 (Table S2). mcl-PHAs synthesized by P. mendocina NKU and its mutant strains were mainly composed of three different monomers, i.e., 3-hydroxyoctanoate, 3-hydroxydecanoate and 3-hydroxydodecanoate, as shown by GC-MS analysis (Figs S4, S5). The monomer composition ratios of the mcl-PHAs had not obvious changes for the mutants compared with NKU (Table S3).

Figure 7.

qPCR analysis and PHA fermentation results for the strains NKU-∆phaZ-4C1, NKU-∆phaZ-6C1, NKU-∆phaZ-16C1 and NKU-∆phaZ. Transcriptional levels of phaC1 (a), phaC2 (b) and phaZ (c) for the different strains. (d) CDW and PHA production for the strains. Samples for qPCR were taken at 36 h of PHA fermentation. The transcriptional level for strain NKU-∆phaZ was set as 1. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements from three independent experiments. A Student’s t-test was performed between NKU-∆phaZ and other mutants. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

The relative transcriptional values of phaC1 and phaC2 in strain NKU-phaZ-4C1, NKU-phaZ-6C1 and NKU-phaZ-16C1 were all improved compared with NKU-phaZ, (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the relative transcriptional values of phaC1 and phaC2 in strain NKU-phaZ-16C1 were the lowest among the above three strains, while the PHA titer of strain NKU-phaZ-16C1 was the highest among the above three strains. The PHA titer of strain NKU-phaZ-4C1 was similar to that of strain NKU-phaZ. Compared with strain NKU-phaZ, the PHA titer of strain NKU-phaZ-6C1 was reduced by 7%, and the PHA titer for strain NKU-phaZ-16C1 were improved by 6% to 23 wt% (Fig. 7). These results indicated that the expression level of phaC was not positively related to the PHA titer in strain NK-01. In future studies, the optimal expression of phaC may be required for obtaining the highest PHA yield in strain NK-01. It should be noted that the native RBS sequence of the phaC gene was unchanged when the strong endogenous promoters were inserted into upstream of the phaC operon in the genome of P. mendocina. In P. mendocina, the native RBS sequence may be optimal for the translational initiation of the phaC operon. RBS can serve as an important regulatory element for translational initiation and thus obviously affect the gene expression level37,38. Only using strong promoters may not obtain the optimal expression levels. For this study, the optimization of the RBS sequence coupled with the screening of endogenous strong promoters may be required for the optimal PHA synthase gene expression.

The relative transcriptional values of phaC1 and phaC2 for the different mutant strains at 12 h and 24 h of mcl-PHA fermentation were also measured, respectivly. As expected, the strains NKU-phaZ-4C1, NKU-phaZ-6C1 and NKU-phaZ-16C1 showed higher transcriptional levels for phaC1 and phaC2 than NKU-phaZ at 12 h, however, no significant differences were observed among the above three strains (Fig. S6). At 24 h, the relative transcriptional values of phaC1 for the above three strains were also improved compared with NKU-phaZ, and NKU-phaZ-4C1 had the highest transcriptional level among the three strains (Fig. S6). Surprisingly, the transcriptional levels for phaC2 at 24 h had not obvious increase for NKU-phaZ-4C1, NKU-phaZ-6C1 and NKU-phaZ-16C1 compared with NKU-phaZ (Fig. S6). The strain NKU-phaZ-16C1 showed the lowest transcriptional levels for phaC1 and phaC2 in any timepoints (Fig. 7 and Fig. S6). These results indicated that the transcriptional levels of phaC1 and phaC2 for the mutant strains were not constant during the PHA fermentation. The changes in the transcriptional levels of the PHA synthase genes over the PHA fermentation period may contribute to lower increase in the PHA yield.

Since a complex metabolic pathway is involved in the synthesis of PHA from glucose, there are many important factors to influence the efficiency of PHA synthesis, including the Entner-Doudoroff pathway, the flux of acetyl-CoA, the fatty acid de novo synthesis pathway, and the availability of the PHA synthesis39–41. Modification of a few factors may not have an obvious influence for the improvement of PHA synthesis.

In this work, all phaZ knockout mutants showed a decrease in the relative transcriptional levels of phaC1 and phaC2 compared with their corresponding strains without deletion of phaZ. Compared with strain NKU-phaZ, the reduction in the PHA titer was observed with strain NKU-phaZ-4C1 and NKU-phaZ-6C1, while the PHA titer was improved for strain NKU-phaZ-16C1 (Fig. 7). These results suggest that PhaZ is not only involved in PHA degradation but also acts as an important role in PHA synthesis in P. mendocina NK-01. A previous study has shown that PhaZ may play a crucial role in the turnover of mcl-PHA under starvation conditions in P. putida KT244242. Rational tuning of the transcriptional activity of PHA synthase and depolymerase would be a feasible approach for the optimization of PHA production in strain NK-01. Therefore, we believe that the screened endogenous strong promoters have the potential to be applied for overexpression of PHA synthesis pathway genes to improve the production of PHA in P. mendocina NK-01.

Promoter engineering such as the screening of strong promoters has been widely applied for metabolic pathway engineering to improve the yield of many industrial products. However, in many cases, the exogenous promoters may not be compatible with the native gene expression systems in P. mendocina NK-01. A previous study in our lab showed that the PHA yield had an obvious decrease after the overexpression of PHA synthase genes using an exogenous strong promoter J23119 in P. putida KT2440 (unpublished data). This also shown it’s not that the more of PhaC expression was, the higher of mcl-PHA yield could get. In this study, we didn’t select a very strong exogenous promoter as the reference and the commonly used lac promoter43,44 has been used as the control in the transcriptional activity assays to screen appropriate endogenous strong promoters. Compared with the lac promoter, the screened endogenous promoters P4, P6 and P16 showed higher transcriptional activity and fluorescence intensity. Therefore, we tested the ability of the screened endogenous promoters to improve the production of mcl-PHA by overexpressing PHA synthase in P. mendocina NK-01. Future work is needed to screen more suitable promoters and optimize the PHA biosynthetic pathway to further improve the mcl-PHA production, not only via overexpression of PHA synthase genes. And the screened endogenous promoters can also be applied to enhance the biosynthesis of AO which is another product synthesized by NK-01 from glucose. The use of endogenous promoters may be a feasible method for the optimization of the expression of the synthetic pathway genes, and this strategy could be potentially utilized for enhanced production of other valuable bio-based products.

Conclusions

In this study, we used the screened endogenous promoters to improve the production of mcl-PHA by overexpressing PHA synthase in P. mendocina NK-01. The use of endogenous promoters may be a feasible method for the optimization of the expression of the synthetic pathway genes, and this strategy could be potentially utilized for enhanced production of other valuable bio-based products.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

E. coli DH5α was used for plasmid construction. E. coli S17-1 was used for conjugal transfer. P. mendocina NK-01 is a chloramphenicol resistant, mcl-PHA-producing strain and is deposited in the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, accession no. CCTCC M 208005). P. mendocina NKU, an upp-deficient strain of P. mendocina NK-0125, was used as the target strain. An E. coli-Pseudomonas shuttle vector pBBR1MCS-2 was used to verify the strengths of 10 endogenous promoters from P. mendocina NK-01 using a reporter gene gfp. A suicide plasmid pEX18Tc-upp was used for promoter integration or phaZ knockout. All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains and plasmids | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Pseudomonas mendocina NKU | PHAMCL producing strain; CmR; preserved in our laboratory; carrying an in-frame deletion in the upp gene; starting strain for engineering | This laboratory |

| P. mendocina NKU pBBR | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-2; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-Plac | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P4 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P4-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P6 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P6-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P9 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P9-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P16 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P16-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P17 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P17-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P18 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P18-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P20 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P20-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P23 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P23-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P25 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P25-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-P29 | NKU derivative containing pBBR1MCS-P29-gfp; CmR; KmR | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-4C1 | NKU derivative carrying an P4 promoter insertion into the upstream of phaC1 gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-6C1 | NKU derivative carrying an P6 promoter insertion into the upstream of phaC1 gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-16C1 | NKU derivative carrying an P16 promoter insertion into the upstream of phaC1 gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-∆phaZ-4C1 | NKU-4C1 derivative carrying an in-frame deletion in the phaZ gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-∆phaZ-6C1 | NKU-6C1 derivative carrying an in-frame deletion in the phaZ gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-∆phaZ-16C1 | NKU-16C1 derivative carrying an in-frame deletion in the phaZ gene | This work |

| P. mendocina NKU-∆phaZ | NKU derivative carrying an in-frame deletion in the phaZ gene | This work |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | F−, φ80dlacZΔM1, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17(rk−, mk+), phoA, supE44, λ−thi-1, gyrA96, relA1 | This laboratory |

| E. coli S17-1 | recA; harbors the tra genes of plasmid RP4 in the chromosome; proA thi-1 | This laboratory |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Broad host range; expression plasmid; Kanr; Plac, mob | 27 |

| pBBR1MCS-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P4-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P4 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P6-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P6 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P9-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P9 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P16-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P16 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P17-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P17 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P18-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P18 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P20-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P20 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P23-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P23 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P25-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P25 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-P29-gfp | pBBR1MCS-2 derivative containing P29 promoter and gfp gene | This work |

| pEX18Tc-upp | pEX18Tc derivative, carrying a copy of upp gene of P. mendocina NKU | This laboratory |

| pEX18Tc-ΔphaZ | pEX18Tc-upp derivative, carrying the up- and downstream regions of phaZ gene, used for deletion of the phaZ gene | This work |

| pEX18Tc-P4 | pEX18Tc-upp derivative, used for insertion of P4 promoter in front of phaC1 | This work |

| pEX18Tc-P6 | pEX18Tc-upp derivative, used for insertion of P6 promoter in front of phaC1 | This work |

| pEX18Tc-P16 | pEX18Tc-upp derivative, used for insertion of P16 promoter in front of phaC1 | This work |

Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl and 2 g/L agar) was used to activate bacteria that stored at −80 °C. E. coli strains were cultivated in LB medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract and 5 g/L NaCl)45 at 37 °C and 180 rpm on a rotary shaker. P. mendocina strains were cultivated in LB medium, nutrient-rich (NR) medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L beef extract power and 5 g/L (NH4)2SO4) or PHA fermentation medium (20 g/L glucose, 9.58 g/L Na2HPO4·12H2O, 2.65 g/L KH2PO4, 0.20 g/L MgSO4 and 1 mL trace element solution) at 30 °C22. For characterization of the endogenous promoters, P. mendocina strains were cultured in 100 mL LB medium in a 500 mL un-baffled flask and cultivated at 30 °C and 180 rpm on a rotary shaker. When necessary, media were supplemented with kanamycin (Kan, 50 μg/mL), tetracycline (Tc, 25 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (Cm, 170 μg/mL) or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 20 μg/mL).

RNA-seq and promoter prediction

The cultures of P. mendocina NK-01 in PHA fermentation medium were sampled every 6 h. Then, the samples were mixed equally for total RNA extraction using an RNApure bacteria kit (Cwbio, Beijing, China). Qualified samples with RIN larger than 8 were submitted to BGI (Shenzhen, China) for RNA-seq analysis.

The expression levels of predicted genes were quantified in terms of RPKM as previously defined26,46. Firstly, the RPKM values were used to rank the gene transcription levels. The upstream regions of highly active genes with high RPKM values were preliminarily selected for promoter prediction. Next, a web-based platform for promoter prediction (Neural Network Promoter Prediction, http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) was used to identify whether the selected upstream regions contain consensus sequence of a promoter. Finally, 10 candidate sequences that can be precisely forecasted to a promoter sequence were chosen for further studies.

Construction of reporter gene vectors

Reporter gene vectors were constructed for the measurement of the strengths of 10 promoters. Each promoter sequence and gfp gene were amplified by PCR, respectively, from genomic DNA of P. mendocina NK-01 and pWH1520-gfp. Then, a fusion fragment including a promoter sequence and gfp gene was obtained by overlapping PCR and inserted into pBBR1MCS-2 in an opposite direction relative to lac promoter on the plasmid using homologous recombination. The same RBS sequence (AGGAGG) was incorporated into upstream of gfp gene by PCR during the construction of all reporter gene vectors. A control vector expressing gfp gene with the above RBS sequence under the control of lac promoter was also constructed with pBBR1MCS-2.

Real-time quantitative PCR for P. mendocina containing various reporter gene vectors

Cells from 1 mL of LB culture were collected at 6, 12, and 15 h. Total RNA was extracted using a commercial RNA pure Bacteria Kit (Cwbio, Beijing, China). After the removal of DNA contamination, cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using a HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Real-time PCR was performed with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a StepOnePlusTM real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions were as follows: pre-incubation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 20 s. Triplicates were used for all analysis. Relative gene expression levels were calculated against the 16S rDNA gene as the internal reference using the 2−ΔΔCt method11,47. The relative promoter activity (RPA) was calculated by normalization against that of lac promoter.

Fluorescence measurement and confocal microscopy for P. mendocina containing various reporter gene vectors

The quantitative measurement of GFP was performed via a microplate reader. Cells from 200 μL of LB culture were collected at 6, 12 and 15 h, washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 7.4), and resuspended (OD600 = 0.5) in 200 μL of PBS buffer. The relative fluorescence intensity was measured with an Enspire Reader System (Perkinelmer, Waltham, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 395 nm and an emission wavelength of 509 nm. The cell optical density at 600 nm was determined using a UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Relative fluorescence intensity was calculated by normalization against per OD600 of whole cells. The fluorescence signal of P. mendocina NKU harboring pBBR1MCS-2 was set as background and was subtracted from the overall fluorescence.

Qualitative observation for the expression of GFP was carried out through the confocal microscopy in a visual form under the same imaging parameters. Cells were harvested after incubation for 12 h in LB medium, washed thrice with PBS buffer (pH 7.4), and resuspended in 400 μL of PBS buffer. Next, cells were stained with 10 μM FM4-64/L for 15 min in the dark and then fixed with 2% glycerol on a slide. The fluorescence image was acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope LSM710 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) fitted with a Zeiss 100 × 10 numerical aperture objective lens using the argon laser at 395 nm for GFP excitation. The master gain was 800 and the laser intensity was 2.0% for GFP imaging.

Construction of P. mendocina mutant strains

The P. mendocina mutants with promoter insertion and phaZ deleted were constructed based on a scarless genome editing strategy25 using the suicide plasmid in combination with upp as a counter-selectable marker. The upp knockout mutant strain P. mendocina NKU was constructed as described previously25. Different promoter sequences were fused independently with the upstream and downstream homologous arms of phaC1 by overlapping PCR, and the fusion fragments were incorporated independently into the suicide plasmid pEX18Tc-upp to generate the gene targeting vectors. The constructed vectors were transformed independently into P. mendocina NKU via conjugal transfer with E. coli S17-1 as the vector donor strain25.

Since the introduced plasmids cannot be replicated autonomously in P. mendocina, they have to integrate via homologous recombination into the chromosome. The single-crossover recombinants were screened by incubating at 30 °C for 24 h on LB agar plates supplemented with 25 μg/mL Tc and 170 μg/mL Cm. Then the selected recombinants were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h in LB medium. To further screen the double-crossover recombinants, the culture broths that had been diluted to 10−2 were spread on LB agar plates supplemented with 20 μg/mL 5-FU. The selected recombinants showing 5-FUr and Tcs were further checked by PCR. All the constructed mutants were validated by DNA sequencing. Furthermore, the phaZ gene of the constructed mutants was deleted from the genome using the above genome editing strategy. All primers used for vector construction and mutant validation are listed in Table S4. The transcriptional level of the phaC operon in the mutant strains was detected by real-time PCR as described above.

Shake-flask fermentation for mcl-PHA production by P. mendocina

PHA production by P. mendocina was achieved with a two-step fermentation process, including the stages of cell proliferation and PHA synthesis. Overnight culture (1%, v/v) was inoculated into 100 mL of NR medium22 in a 500 mL un-baffled flask and then incubated at 30 °C and 180 rpm on a rotary shaker for 24 h. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2,500 × g and 4 °C and resuspended in 1 mL PBS buffer. Next, the seed culture was inoculated into 100 mL of fermentation medium, pH 7.022 in a 500 mL un-baffled flask and cultivated at 30 °C and 180 rpm on a rotary shaker for 36 h. After fermentation, the culture broth was centrifuged at 4 °C and 13,000 × g for 20 min to collect bacterial cells. Cells were lyophilized for 24 h and weighed. Finally, PHA was extracted from lysed cells with chloroform at a rate of 100 mL chloroform g−1 cells at room temperature for 2 days21,22. The extract containing PHA was filtered to remove cellular debris by the Whatman filter paper and then concentrated by a vacuum rotary evaporator. A 40-fold volume of pre-cooled methanol was added to precipitate PHA overnight. PHA was weighed after being dried at room temperature to remove all residual solvent21,22.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry (GC/MS)

The molecular weight of PHA was estimated by GPC (Alltech, USA) with a K-804 gel column (Shodex, Japan) and a SFD differential refractive index detector (Schambeck, Germany) according to the previously established procedure23.

The monomer composition of PHA was determined by GC/MS analysis using an Agilent Technologies 7890A-5975C (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Firstly, 5 mg of PHA sample was dissolved in 2 mL CHCl3 and subjected to methanolysis in the presence of 0.3 mL H2SO4 and 1.7 mL CH3OH at 100 °C for 140 min in order to obtain the corresponding 3-hydroxyalkanoic methyl esters. The produced monomers were further identified by comparing their GC and MS spectra with that of the authentic standards in GC/MS analysis. The detailed procedures for GC/MS analysis are described in Guo et al.21.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Funding of China (Grant Nos. 31470213, 31570035 and 31670093), the Tianjin Natural Science Funding (Grant Nos. 17JCZDJC32100 and 18JCYBJC24500) and the Postdoctoral Science Funding of China (Grant No. 2018M631729).

Author Contributions

C.Y. designed the research. F.J.Z., X.S.L., W.X.G. and Y.X.Z. performed the research. F.J.Z., A.N.K., X.F., T.M., S.F.W. and C.Y. analyzed the data. F.J.Z., S.F.W. and C.Y. wrote the paper. All the authors read and accepted the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository with the BioProject accession number PRJNA514902, BioSample accession number SAMN10736309 and SRA accession number SRR8437825.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Weixia Gao, Email: watersave@126.com.

Shufang Wang, Email: wangshufang@nankai.edu.cn.

Chao Yang, Email: yangc20119@nankai.edu.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-39321-z.

References

- 1.Wu J, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for (2S)-pinocembrin production from glucose by a modular metabolic strategy. Metab Eng. 2013;16:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao YF, Wang CS, Qiao J, Zhao GR. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for production of salvianic acid A via an artificial biosynthetic pathway. Metab Eng. 2013;19:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu P, et al. Modular optimization of multigene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheppard MJ, Kunjapur AM, Prather KLJ. Modular and selective biosynthesis of gasoline-range alkanes. Metab Eng. 2016;33:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Zhu P, Liu M. Modularoptimization of multi-gene pathways for fumarate production. Metab Eng. 2016;33:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markley AL, Begemann MB, Clarke RE, Gordon GC, Pfleger BF. Synthetic biology toolbox for controlling gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC 7002. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:595–603. doi: 10.1021/sb500260k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JA, et al. ePathOptimize: A Combinatorial Approach for Transcriptional Balancing of Metabolic Pathways. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11301. doi: 10.1038/srep11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alper H, Fischer C, Nevoigt E, Stephanopoulos G. Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12678–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504604102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, et al. Genome-wide identification and evaluation of constitutive promoters in streptomycetes. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:172. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0351-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo Y, Zhang L, Barton KW, Zhao H. Systematic identification of a panel of strong constitutive promoters from Streptomyces albus. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:1001–10. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Y, et al. Promoter screening from Bacillus subtilis in various conditions hunting for synthetic biology and industrial applications. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0158447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Yap SA, Koh CM, Ji L. Developing a set of strong intronic promoters for robust metabolic engineering in oleaginous Rhodotorula (Rhodosporidium) yeast species. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:200. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0600-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S, Du G, Chen J, Kang Z. Characterization and application of endogenous phase-dependent promoters in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:4151–61. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou S, et al. Obtaining a panel of cascade promoter-5′-UTR complexes in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:1065–75. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy CS, Ghai R, Rashmi., Kalia VC. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: An overview. Bioresour Technol. 2003;87:137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen GQ, Wu Q. The application of polyhydroxyalkanoates as tissue engineering materials. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6565–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Tappel RC, Zhu C, Nomura CT. Development of a new strategy for production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by recombinant Escherichia coli via inexpensive non-fatty acid feedstocks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:519–27. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07020-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Q, Zhuang Q, Liang Q, Qi Q. Polyhydroxyalkanoic acids from structurally-unrelated carbon sources in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3301–7. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4809-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Luo G, Zhou XR, Chen GQ. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxydecanoate) and 3-hydroxydodecanoate dominating polyhydroxyalkanoates by beta-oxidation pathway inhibited Pseudomonas putida. Metab Eng. 2011;13:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T, Elhadi D, Chen GQ. Co-production of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates with other chemicals. Metab Eng. 2017;43:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo W, et al. Simultaneous production and characterization of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates and alginate oligosaccharides by Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Zhao F, Fan X, Wang S, Song C. Enhancement of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis from glucose by metabolic engineering in Pseudomonas mendocina. Biotechnol Lett. 2016;38:313–20. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1980-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo W, et al. Comparison of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates synthases from Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 with the same substrate specificity. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo W, et al. Complete genome of Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01, which synthesizes medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates and alginate oligosaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3413–4. doi: 10.1128/JB.05068-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, et al. An upp-based markerless gene replacement method for genome reduction and metabolic pathway engineering in Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 and Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;113:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovach ME, et al. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zobel S, et al. Tn7-based device for calibrated heterologous gene expression in Pseudomonas putida. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:1341–51. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calero P, Jensen SI, Nielsen AT. Broad-Host-Range ProUSER vectors enable fast characterization of inducible promoters and optimization of p-coumaric acid production in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:741–53. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva-Rocha R, et al. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D666–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-García E, Aparicio T, Goñi-Moreno A, Fraile S, de Lorenzo V. SEVA 2.0: an update of the Standard European Vector Architecture for de-/re-construction of bacterial functionalities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D1183–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arias S, Bassas-Galia M, Molinari G, Timmis KN. Tight coupling of polymerization and depolymerization of polyhydroxyalkanoates ensures efficient management of carbon resources in Pseudomonas putida. Microb Biotechnol. 2013;6:551–63. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai L, Yuan MQ, Liu F, Jian J, Chen GQ. Enhanced production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) by PHA depolymerase knockout mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:2265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vo MT, Ko K, Ramsay B. Carbon-limited fed-batch production of medium-chain-lengthpolyhydroxyalkanoates by a phaZ-knockout strain of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:637–46. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huisman GW, Wonink E, de Koning G, Preusting H, Witholt B. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by mutant and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;38:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00169409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solaiman DK, Ashby RD, Foglia TA. Effect of inactivation of poly(hydroxyalkanoates) depolymerase gene on the properties of poly(hydroxyalkanoates) Pseudomonas resinovorans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;62:536–43. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiao S, Yu H, Shen Z. Core element characterization of Rhodococcus promoters and development of a promoter-RBS mini-pool with different activity levels for efficient gene expression. N Biotechnol. 2018;44:41–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:946–50. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poblete-Castro I, et al. In-silico-driven metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for enhanced production of poly-hydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng. 2013;15:113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prieto A, et al. A holistic view of polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2015;18:341–57. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikel PI, Chavarría M, Fuhrer T, Sauer U, de Lorenzo V. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 strain metabolizes glucosethrough a cycle formed by enzymes of the Entner-Doudoroff, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas, and Pentose Phosphate Pathways. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:25920–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.687749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Eugenio LI, et al. The turnover of mediumchain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 and the fundamental role of PhaZ depolymerase for the metabolic balance. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:207–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang JP, et al. Metabolic engineering for ethylene production by inserting the ethylene-forming enzyme gene (efe) at the 16S rDNA sites of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:6404–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Shi ZY, Wu Q, Chen GQ. Microbial production of 4-hydroxybutyrate, poly-4-hydroxybutyrate, and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) by recombinant microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84:909–16. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green, M. R. & Sambrook, J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA (2012).

- 46.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository with the BioProject accession number PRJNA514902, BioSample accession number SAMN10736309 and SRA accession number SRR8437825.