Summary

Recent advances in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) differentiation protocols have generated insulin-producing cells resembling pancreatic β cells. While these stem cell-derived β (SC-β) cells are capable of undergoing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), insulin secretion per cell remains low compared with islets and cells lack dynamic insulin release. Herein, we report a differentiation strategy focused on modulating transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling, controlling cellular cluster size, and using an enriched serum-free media to generate SC-β cells that express β cell markers and undergo GSIS with first- and second-phase dynamic insulin secretion. Transplantation of these cells into mice greatly improves glucose tolerance. These results reveal that specific time frames for inhibiting and permitting TGF-β signaling are required during SC-β cell differentiation to achieve dynamic function. The capacity of these cells to undergo GSIS with dynamic insulin release makes them a promising cell source for diabetes cellular therapy.

Keywords: human embryonic stem cells, human induced pluripotent stem cells, diabetes, differentiation, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, transplantation, cell therapy, β cells, pancreas, islets

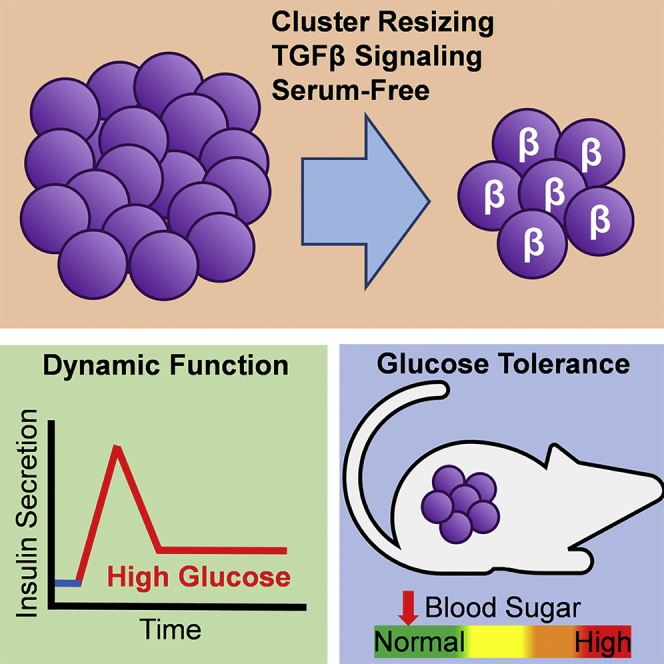

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Development of differentiation protocol to β-like cells with enhanced function

-

•

TGF-β signaling promotes acquisition of dynamic function in maturing β-like cells

-

•

Transplanted cells rapidly restore glucose tolerance in mice

In this study, Millman and colleagues report a differentiation strategy to generate β-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells with islet-like dynamic insulin release that rapidly reverses diabetes in mice. The authors elucidate that stage-specific control of TGF-β signaling during endocrine induction and maturation to be critical for robust function.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a global health problem affecting over 400 million people worldwide and is increasing in prevalence (Mathers and Loncar, 2006, Stokes and Preston, 2017). Diabetes is principally caused by the death or dysfunction of insulin-producing β cells found within the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, resulting in improper insulin secretion and failure of patients to maintain normal glycemia, which in severe cases can cause ketoacidosis and death. Patients are often reliant on insulin injections but can still suffer from long-term complications, including retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease (Nathan, 1993). An alternative treatment is replacement of the endogenous β cells by transplantation of pancreatic islets (Bellin et al., 2012, Hering et al., 2016, Lacy and Kostianovsky, 1967, Scharp et al., 1990, Shapiro et al., 2000). While this therapy has had clinical success, limited availability of cadaveric donor islets largely hampers its widespread application (Bonner-Weir and Weir, 2005).

Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into stem cell-derived β cells (SC-β cells) is a promising alternative cell source for diabetes cell replacement therapy as well as other applications, such as modeling disease and studying pancreatic development (Millman and Pagliuca, 2017). Through modulation of pathways identified from embryonic development, studies with hPSCs have detailed protocols for generating cells that resemble early endoderm and pancreatic progenitors (D'Amour et al., 2006, D'Amour et al., 2005, Kroon et al., 2008, Nostro et al., 2015, Rezania et al., 2012), the latter of which can be transplanted into rodents and spontaneously differentiated into β-like cells after several months (Bruin et al., 2015, Kroon et al., 2008, Millman et al., 2016, Rezania et al., 2012).

We (Pagliuca et al., 2014) and others (Rezania et al., 2014) published similar approaches for generating SC-β cells in vitro that in part use the compound Alk5 inhibitor type II (Alk5i) to inhibit transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling during the last stages of differentiation. These approaches produced SC-β cells capable of undergoing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in static incubations, expressing β cell markers, and controling blood sugar in diabetic mice after several weeks. However, even with this significant breakthrough, these cells had inferior function compared with human islets, including lower insulin secretion and little to no first- and second-phase insulin release in response to a high glucose challenge, demonstrating that these SC-β cells were less mature than β cells from islets. Several follow-up studies have been performed introducing additional differentiation factors or optimizing the process but have failed to bring SC-β cell function equivalent to human islets (Ghazizadeh et al., 2017, Millman et al., 2016, Russ et al., 2015, Zhu et al., 2016).

Here we report a six-stage differentiation strategy that generates almost pure populations of endocrine cells containing β-like cells that secrete high levels of insulin and express β cell markers. This is achieved by modulating Alk5i exposure to inhibit and permit TGF-β signaling during key stages in combination with cellular cluster resizing and enriched serum-free media (ESFM) culture. These cells are glucose responsive, exhibiting first- and second-phase insulin release, and respond to multiple secretagogues. Transplanted cells greatly improve glucose tolerance in mice. We identify that inhibiting TGF-β signaling during stage 6 greatly reduces the function of these differentiated cells while treatment with Alk5i during stage 5 is necessary for a robust β-like cell phenotype.

Results

Differentiation to Glucose-Responsive SC-β Cells In Vitro

We set out to develop an improved differentiation protocol starting from the approach we described in Pagliuca et al. (2014) using the HUES8 cell line. We included Y27632 during stages 3 to 4 and activin A during stage 4 as we reported previously (Millman et al., 2016) to help maintain cluster integrity and shortened stage 3 from 2 days to only 1 day to enhance progenitors (Nostro et al., 2015). We also developed an ESFM for stage 6 to replace the serum-containing media used previously to have a serum-free protocol. During our protocol pilot studies, we observed that both resizing clusters and removal of Alk5i and T3 increased insulin secretion while maintaining the C-peptide+ population (Figures S1A and S1B).

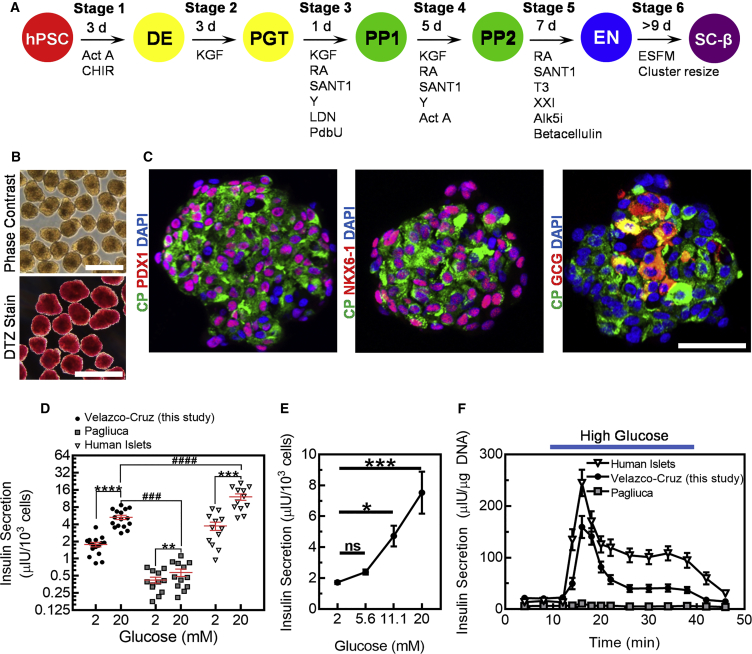

Combining these modifications resulted in our six-stage differentiation protocol outlined in Figure 1A. Stage 6 cells are grown as clusters in suspension culture (Figure 1B) that averaged 172 ± 34 μm (mean ± SD; n = 353 individual clusters) in diameter, less than half the diameter of the clusters before resizing, which was 364 ± 55 μm (n = 155 individual clusters). Stage 6 clusters stained red for the zinc-chelating dye dithizone, which stains β cells. Immunostaining of sectioned clusters revealed most cells to be C-peptide+, a protein also produced by the INS gene, in addition to PDX1+ and NKX6-1+, β cell markers (Figure 1C). A subset of cells stained positive for GCG or were polyhormonal, staining positive for both C-peptide and GCG. These polyhormonal cells are known to not to resemble adult β cells and are not functional (D'Amour et al., 2006, Hrvatin et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

SC-β Cell Clusters undergo GSIS

(A) Overview of our differentiation procedure.

(B) Images of unstained whole stage 6 clusters under phase contrast (top) or stained with dithizone (DTZ) (bottom) imaged under bright field. Scale bars, 400 μm.

(C) Immunostaining of sectioned stage 6 clusters stained for glucagon (GCG), NKX6-1, PDX1, C-peptide (CP), or with the nuclei marker DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) Human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells generated with the protocol from this study (n = 16), stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol (n = 12), and cadaveric human islets (n = 12) in a static GSIS assay. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.001 by one-sided paired t test. ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA Dunnett multiple comparison test compared with this study.

(E) Static GSIS assay of stage 6 cells from this study subjected to either 2, 5.6, 11.1, or 20 mM glucose (n = 4). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n.s., not significant by one-way ANOVA Dunnett multiple comparison test compared with 2 mM glucose.

(F) Dynamic human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells generated with the protocol from this study (n = 12), stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol (n = 4), and cadaveric human islets (n = 12) in a perfusion GSIS assay. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high glucose (20 mM) is indicated. Act A, activin A; CHIR, CHIR9901; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; RA, retinoic acid; Y, Y27632; LDN, LDN193189; PdbU, phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate; T3, triiodothyronine; Alk5i, Alk5 inhibitor type II; ESFM, enriched serum-free medium. All stage 6 data shown are with HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

We tested function of stage 6 cells generated with our differentiation protocol using both static (Figures 1D, 1E, and S1C) and dynamic GSIS assays (Figures 1F and S1D) and found that not only do the cells secrete insulin but also increase insulin release when moved from low to high glucose. With static GSIS, while there was some variability, stage 6 cells increased insulin secretion on average by a factor of 3.0 ± 0.1 when moved from 2 to 20 mM glucose. This is an improvement compared with cells generated with the protocol described in Pagliuca et al. (2014) (1.4 ± 0.1), referred to here as the Pagliuca protocol, but less than human islets (3.2 ± 0.1) on average (Figure 1D). Stage 6 cells from this study did not increase insulin secretion in response to 5.6 mM glucose but did increase secretion in response to higher concentrations (11.1 and 20 mM), indicating that the cells are only stimulated at higher glucose threshold (Figure 1E). In terms of insulin secretion per cell, stage 6 cells secreted on average 5.3 ± 0.5 μIU/103 cells at 20 mM glucose, 9.2 ± 1.1 times more than cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol and 2.3 ± 0.3 times less than human islets, on average (Figure 1D). It is important to note that our insulin values with the Pagliuca protocol are within range of the 2014 report but were lower on average, with differentiated HUES8 reported to secrete 0.2–2.6 μIU/103 cells (average 1.4) and increase secretion by 0.4–4.1 (average 1.7) to high glucose.

With dynamic GSIS, stage 6 cells displayed a rapid first-phase insulin release within 3–5 min of high glucose exposure, increasing insulin secretion by a factor of 7.6 ± 1.3 to 159 ± 21 μIU/μg DNA, higher than stage 6 cells generated from the Pagliuca protocol (1.7 ± 0.2× increase to 11 ± 1 μIU/μg DNA) but lower than human islets (15.0 ± 2.4× increase to 245 ± 26 μIU/μg DNA) (Figure 1F). Second-phase insulin secretion was observed with continued high glucose exposure, with cells maintaining 2.1 ± 0.3 higher insulin secretion than the initial low glucose, a higher increase than with the Pagliuca protocol (0.9 ± 0.1) but lower than human islets (6.7 ± 0.8) (Figure 1F). When the cells were returned to low glucose, insulin secretion from stage 6 cells returned to a reduced rate. Elevating insulin secretion and displaying first- and second-phase insulin release to a high glucose challenge are key features of β cell behavior. Overall, stage 6 cells generated with this differentiation strategy produces cells with clear first- and second-phase insulin secretion, which was not demonstrated by Pagliuca et al. (2014) and Rezania et al. (2014) and not seen with stage 6 cells produced with the Pagliuca protocol. However, when compared with human islets containing β cells, these stage 6 cells still have lower insulin secretion per cell at high glucose, lower glucose stimulation on average, and slightly slower first-phase insulin release.

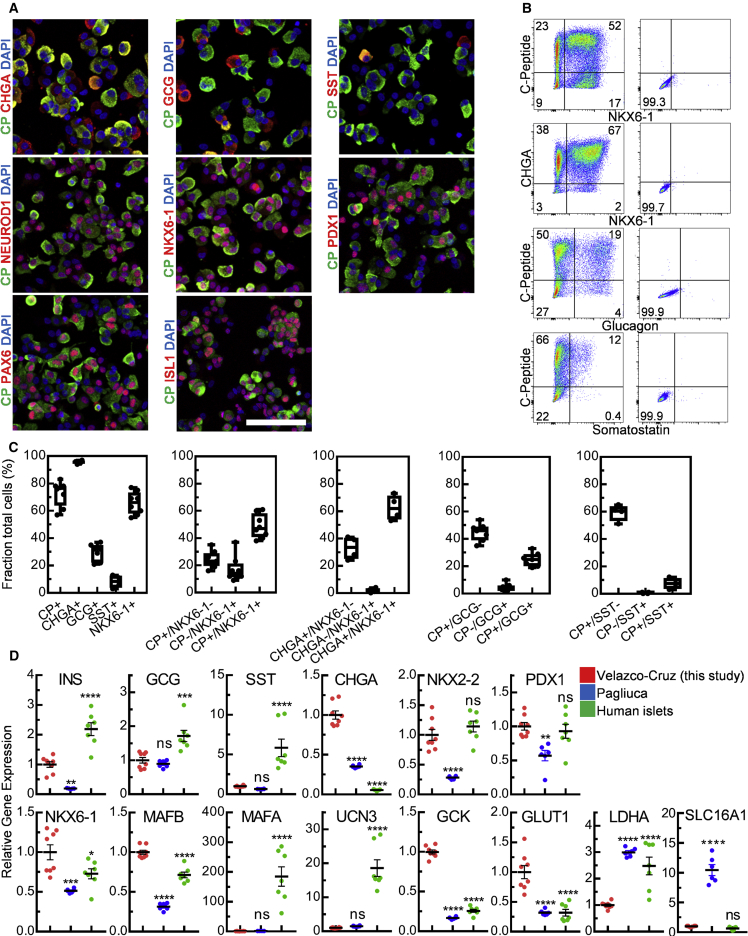

To further characterize stage 6 cells generated with our differentiation protocol, we immunostained cells with a panel of pancreatic islet markers (Figures 2A–2C and S2). The vast majority of cells expressed CHGA (96% ± 1%), a pan-endocrine marker, and most cells expressed C-peptide (73% ± 3%) (Figure 2). These fractions are higher than in stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol (Figure S2) and reported in Pagliuca et al. (2014). Many C-peptide+ cells from both protocols expressed other markers found in β cells and expression of the other pancreatic hormones was observed (Figures 2 and S2). The majority of C-peptide+ cells expressed NKX6-1 (Figure 2) and were monohormonal, which we presumed to be the SC-β cell population as done previously (Pagliuca et al., 2014). The fraction of C-peptide+ cells not expressing another hormone was increased compared with stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol and reported in Pagliuca et al. (2014), while the fraction of these cells expressing another hormone was comparable (Figures 2 and S2). These data show that stage 6 cells generated with our differentiation strategy are predominantly pancreatic endocrine with the majority expressing C-peptide.

Figure 2.

SC-β Cells Express β Cell and Islet Markers

(A) Immunostaining of dispersed stage 6 clusters plated overnight and stained for chromogranin A (CHGA), GCG, somatostatin (SST), NEUROD1, NKX6-1, PDX1, PAX6, C-peptide (CP), or with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) Representative flow cytometric dot plots of dispersed stage 6 clusters immunostained for the indicated markers.

(C) Box-and-whiskers plots quantifying fraction of cells expressing the indicated markers. Each point is an independent experiment.

(D) Real-time PCR analysis of stage 6 cells generated with the protocol from this study (n = 8), stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol (n = 5), and cadaveric human islets (n = 7). n.s., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA Dunnett multiple comparison test compared with this study. All stage 6 data shown are with HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

We measured expression of several genes compared with stage 6 cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol and human islets (Figures 2D and S3). Many islet and β cell genes were increased compared with the Pagliuca protocol, including INS, CHGA, NKX2-2, PDX1, NKX6-1, MAFB, GCK, and GLUT1. Interestingly, LDHA and SLC16A1, disallowed β cell genes, had reduced expression in our stage 6 cells compared with both the Pagliuca protocol and human islets (LDHA) and the Pagliuca protocol (SLC16A1). Our stage 6 cells had increased expression of CHGA, NKX6-1, MAFB, GCK, and GLUT1 compared with human islets. However, INS, GCG, SST, and particularly MAFA and UCN3 had reduced expression compared with stage 6 cells. However, several recent reports have provided evidence that question the utility of MAFA and UCN3 in evaluating human SC-β cell maturation. MAFA expression is low in juvenile human β cells (Arda et al., 2016). MAFB is expressed in human but not mouse β cells (Arda et al., 2016, Tritschler et al., 2017, Xin et al., 2016). UCN3 expression is much higher in mouse than human β cells (Xin et al., 2016) and is also expressed by human α cells (Baron et al., 2016, Tritschler et al., 2017). These data show that our stage 6 cells have improved gene expression for many markers compared with the Pagliuca protocol and, while the expression of several β cell markers are equal to or great than human islets, other markers remain low.

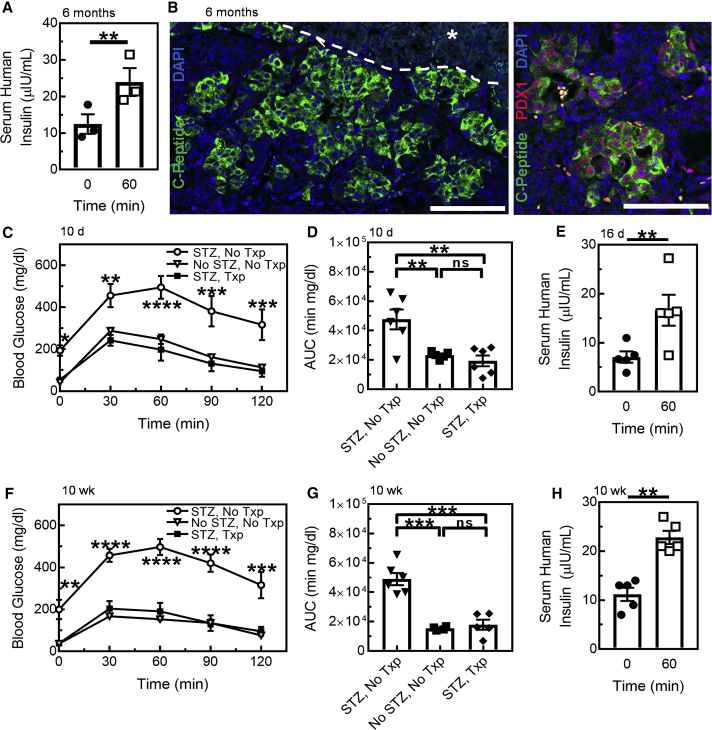

Transplantation of SC-β Cells into Glucose-Intolerant Mice

To evaluate the functional potential of stage 6 cells in vivo, we first transplanted cells under the renal capsule of non-diabetic mice and evaluated the ability of the graft to respond to a glucose challenge (Figure 3A). We observed that, even after extended time post-transplantation (6 months), the grafts responded to a glucose injection by increasing human insulin by a factor of 1.9 ± 0.5. Excision and immunostaining of the transplanted kidneys revealed C-peptide+ cells that tended to be clustered together in addition to other pancreatic endocrine and exocrine markers (Figures 3B and S4A). To more rigorously evaluate stage 6 cells in vivo, we transplanted a separate mouse cohort that had been chemically induced to be diabetic with streptozotocin (STZ) and evaluated function at early (10 and 16 day) and late (10 week) time points. After only 10 days post-transplantation, STZ-treated mice receiving stage 6 cells had greatly improved glucose tolerance compared with STZ-treated sham mice and had similar glucose clearance as the non-STZ-treated mice (Figures 3C and 3D). Measurements of human insulin 16 days after transplantation revealed high insulin concentrations that increased by a factor of 2.3 ± 0.6 with a glucose injection to 16.6 ± 3.1 μIU/mL (Figure 3E). These values are greater than what was reported in Pagliuca et al. (2014) under similar conditions, which had an insulin increase of 1.4 ± 0.3 and concentration of 3.8 ± 0.8 μIU/mL. Observing our cohort 10 weeks after transplantation revealed similar results as the 10- and 16-day data, with transplanted mice having greatly improved glucose tolerance (Figures 3F and 3G) and glucose-responsive insulin secretion (Figure 3H). Mice not receiving STZ had similar glucose tolerance as mice receiving a therapeutic dose of human islets (Pagliuca et al., 2014). Mice that did not receive stage 6 cells had undetectable human insulin and mice that received STZ had drastically reduced mouse C-peptide compared with non-STZ-treated mice (Figures S4B and S4C). Grafts from these STZ-treated mice contained cells that expressed β cell markers in addition to other endocrine and exocrine markers (Figure S4D). Overall these data demonstrate that stage 6 cells generated with our protocol are functional both at early and late time points in vivo, greatly improving glucose tolerance to equal that of non-STZ-treated mice.

Figure 3.

SC-β Cells Greatly Improve Glucose Tolerance and Have Persistent Function for Months after Transplantation

(A) Serum human insulin of a non-STZ-treated mouse cohort (n = 3) 6 months after transplantation fasted overnight 0 and 60 min after an injection of 2 g/kg glucose. ∗∗p < 0.01 by one-sided paired t test.

(B) Immunostaining of sectioned explanted kidneys of non-STZ-treated mice 6 months after transplantation for C-peptide, PDX1, or with DAPI. The white dashed line is manually drawn to show the border between kidney and graft (∗). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(C) Glucose tolerance test (GTT) 10days after surgery for STZ-treated mice cohort without a transplant (STZ, No Txp; n = 6), untreated mice without a transplant (No STZ, No Txp; n = 5), and STZ-treated mice with a transplant (STZ, Txp; n = 6). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA Tukey multiple comparison.

(D) Area under the curve (AUC) calculations for data shown in (C). ∗∗p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA Tukey multiple comparison test.

(E) Serum human insulin of STZ, Txp mice (n = 5) fasted overnight 0 and 60 min after an injection of 2 g/kg glucose. ∗∗p < 0.01 by one-sided paired t test.

(F) GTT 10 weeks after surgery for STZ, No Txp mice (n = 6), No STZ, No Txp mice (n = 4), and STZ, Txp mice (n = 5). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA Tukey multiple comparison test.

(G) AUC calculations for data shown in (D). ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA Tukey multiple comparison test.

(H) Serum human insulin of STZ, Txp mice (n = 5) fasted overnight 0 and 60 min after an injection of 2 g/kg glucose. ∗∗p < 0.01 by one-sided paired t test. All data shown are with HUES8. (A and B) are severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)/Beige and (C–H) are non-obese diabetic/SCID mice.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

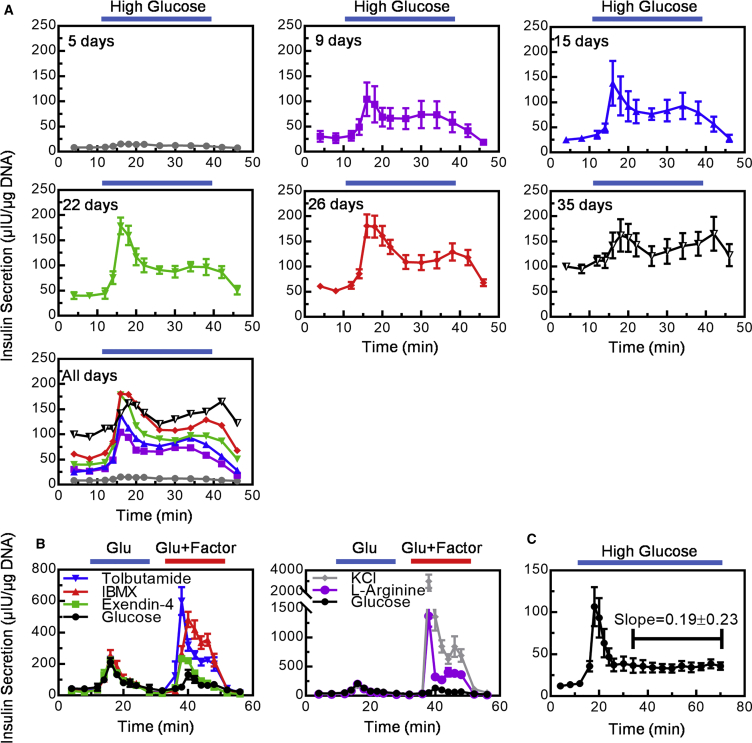

Characterization of SC-β Cell Dynamic Function

Since the differentiation protocol produces cells that are capable of dynamic insulin secretion, we studied this phenotype in more detail. We performed dynamic GSIS on cells as they progressed through stage 6 (Figure 4A). We observed that robust dynamic function was transient, with cells at 5 days secreting low amounts of insulin and exhibiting weak first- and second-phase response, with later time points (9–26 days) secreting higher amounts of insulin with a clear first- and second-phase response. During this time, the fraction of C-peptide+ cells decreased slightly (Figure S5A). By 35 days, insulin secretion at low glucose had risen such that first and second phases were difficult to clearly identify. These data show that SC-β cells require 9 days in stage 6 to acquire dynamic function, this function persists for weeks, but after extended in vitro culture glucose responsiveness is lost. Similarly, cadaveric human islets are known to have a limited functional lifetime in vitro, but the cause of this is not clear. These data further suggest an optimal time frame for these cells to be used in transplantation and drug-screening studies.

Figure 4.

SC-β Cells have Transient Dynamic Function In Vitro, Respond to Multiple Stimuli, and Sustain Second-Phase Insulin Secretion at High Glucose

(A) Dynamic human insulin secretion cells in stage 6 for 5, 9, 15, 22, 26, and 35 days in a perfusion GSIS assay. Data for each individual time point is shown as mean ± SEM and the final graph shows only the means of each graph. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high glucose (20 mM) is indicated (n = 3 for each stage 6 time point).

(B) Dynamic human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells in a perfusion GSIS assay treated with multiple secretagogues. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high (20 mM) glucose is indicated (Glu), then perfused with a second challenge of high glucose alone or with additional compounds (tolbutamide, IBMX, and Extendin-4 on the left; KCL and L-arginine on the right) where indicated (Glu + Factor). Note that the high glucose-only challenge is shown in both left and right graphs and the scale change (n = 3 except glucose, which is n = 2).

(C) Dynamic human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells in a perfusion GSIS assay with an extended high glucose treatment. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high glucose (20 mM) is indicated (n = 3). All data shown are with HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

To further characterize dynamic insulin secretion, we performed perifusion experiments to assay whether SC-β cells could respond to sequential challenges with several known secretagogues (Figure 4B). After an initial high glucose challenge, SC-β cells were able to respond to a second high glucose-only challenge, albeit less strongly than the first challenge, and extending the first glucose challenge to 1 hr in a separate experiment did not reduce insulin secretion (Figure 4C). Addition of other secretagogues during the second challenge further increased insulin secretion (Figure 4B). Membrane depolarizers KCl and L-arginine had the largest increases. Tolbutamide (blocks potassium channel), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) (raises cytosolic cAMP), and exendin-4 (agonist of GLP-1 receptor) also increased insulin secretion over high glucose alone. Not only was insulin secretion increased but it rose faster than with high glucose alone. However, we noted that the response of stage 6 cells to KCl challenge was stronger than in human islets (Figure S5B), an observation made by others comparing β-like cells to human islets (Rezania et al., 2014), possibly indicative of continued immature or juvenile β cell phenotype. Taken together, these data show that SC-β cells can respond to several secretagogues that have diverse modes of action and have potential application in drug screening.

Role of TGF-β Signaling in SC-β Cell Differentiation and Maturation

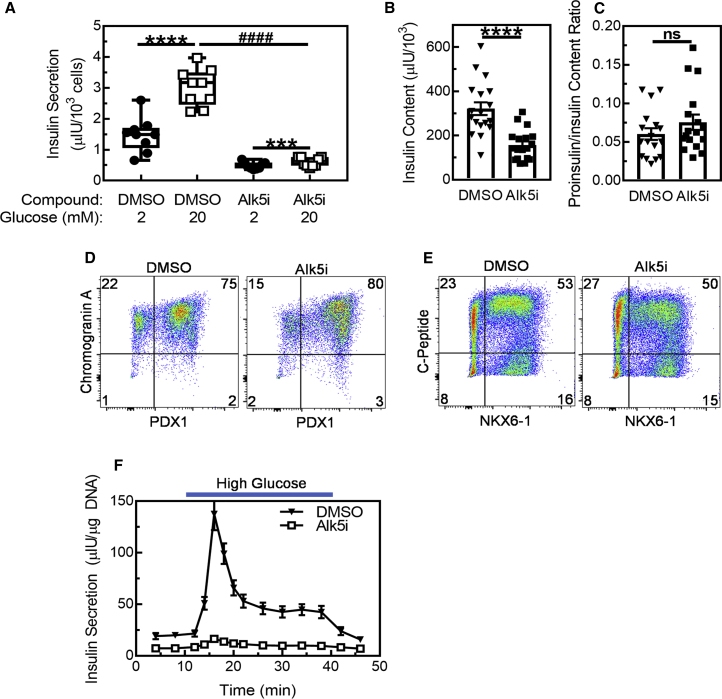

After having evaluated SC-β cells generated with our protocol, we investigated the protocol changes that were made to gain insights into SC-β cell differentiation and maturation. We found that, while inclusion of Alk5i during stage 6 resulted in relatively weak but statistically significant GSIS in a static assay, similar to data from the Pagliuca protocol (Figure 1D), omission of Alk5i drastically increased insulin secretion and glucose stimulation (Figures 5A and S6A). Insulin content also increased with removal of Alk5i during stage 6 (Figure 5B), but the proinsulin/insulin ratio remained similar (Figure 5C), suggesting that the increased insulin content is not due to hormone processing. Furthermore, the fraction of cells expressing pancreatic endocrine markers, including C-peptide, remained similar between DMSO- and Alk5i-treated cells (Figures 5D, 5E, and S6B). Gene expression was similar overall with and without Alk5i treatment, with cluster resizing typically having a larger effect (Figure S6C). Cells treated with Alk5i during stage 6 also had dramatically reduced insulin secretion with the dynamic GSIS assay, displaying weak to no first- and second-phase response (Figure 5F), similar to cells generated with the Pagliuca protocol (Figure 1F). These data show that Alk5i treatment during stage 6 inhibits functional maturation of SC-β cells.

Figure 5.

Alk5i Reduces SC-β Cell GSIS

(A) Box-and-whiskers plot of human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells in static GSIS assay treated with DMSO or Alk5i (n = 9). ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by two-way paired t test; ####p < 0.0001 by two-way unpaired t test.

(B) Cellular insulin content of stage 6 cells treated with DMSO or Alk5i (n = 18). ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by two-way unpaired t test.

(C) Cellular proinsulin/insulin content ratio of stage 6 cells treated with DMSO or Alk5i (n = 17). n.s., not significant by two-way unpaired t test.

(D and E) Representative flow cytometric dot plots of dispersed stage 6 clusters immunostained for CHGA and PDX1 (D) or C-peptide and NKX6-1 (E).

(F) Dynamic human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells treated with DMSO or Alk5i in a perfusion GSIS assay. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high glucose (20 mM) is indicated (n = 12). All data shown are with HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

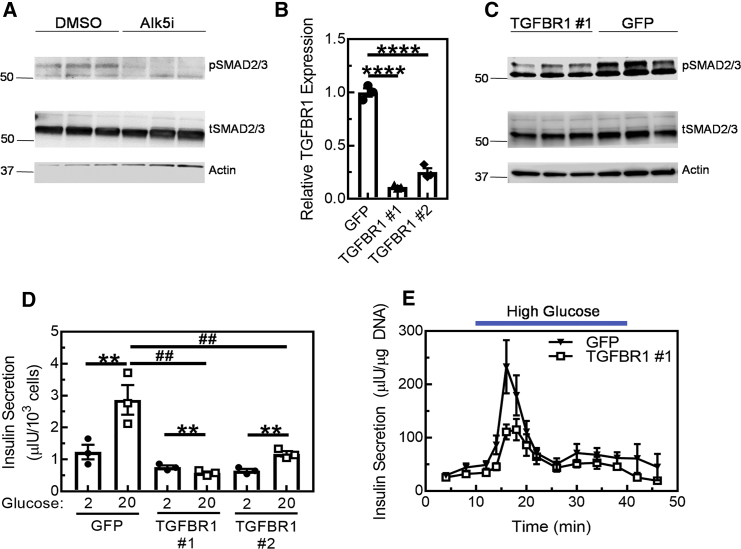

Our studies with Alk5i during stage 6 suggested that permitting TGF-β signaling was necessary for robust functional maturation of SC-β cells, as inhibition of TGFBR1 is the canonical function of Alk5i. To test this hypothesis, we first used western blot analysis to validate that TGF-β signaling was occurring in our stage 6 cells via SMAD phosphorylation (Figure 6A). Alk5i treatment diminished phosphorylated SMAD, confirming that TGF-β signaling was indeed occurring and inhibited by Alk5i. SMAD phosphorylation was observed in stage 6 clusters regardless of whether they were resized, consistent with observations that Alk5i treatment reduced GSIS regardless of resizing (Figure S7). Next, we generated two lentiviruses carrying short hairpin RNA (shRNA) designed to knock down TGFBR1 (TGFBR1 no. 1 and no. 2). These viruses were capable of reducing TGFBR1 transcript compared with control virus targeting GFP in stage 6 cells (Figure 6B) and reduced SMAD phosphorylation (Figures 6C and S7C), albeit to much lesser extent than Alk5i treatment (Figure 6A). Similar to Alk5i treatment (Figures 5A and 5F), stage 6 cells transduced with shRNA against TGFBR1 had reduced insulin secretion and reduced positive glucose responsiveness in the static GSIS assay (Figure 6C) and blunted glucose response in the dynamic GSIS assay (Figure 6D). These data show that permitting TGF-β signaling during stage 6 is important for SC-β cell functional maturation, which is inhibited by treatment with Alk5i.

Figure 6.

Blocking TGF-β Signaling during Stage 6 Hampers GSIS

(A) Western blot of stage 6 cells cultured with DMSO or Alk5i stained for phosphorylated SMAD 2/3 (pSMAD2/3), total SMAD 2/3 (tSMAD2/3), and actin. Data shown are from HUES8.

(B) Real-time PCR of stage 6 cells transduced with lentiviruses containing GFP (control) or one of two sequences against TGFBR1 (TGFBR1 no. 1 and no. 2) (n = 3) shRNA. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA Dunnett multiple comparison test compared with GFP.

(C) Western blot of stage 6 cells transduced with lentiviruses containing GFP or TGFBR1 no. 1 shRNA. Data shown are from 1013-4FA.

(D) Human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells in static GSIS assay transduced with lentiviruses containing GFP, TGFBR1 no. 1 or no. 2 shRNA (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01 by paired two-way t test. ##p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA Dunnett multiple comparison test compared with GFP. Data shown are from HUES8.

(E) Dynamic human insulin secretion of stage 6 cells transduced with lentiviruses containing GFP or TGFBR1 no. 1 shRNA in a perfusion GSIS assay. Cells are perfused with low glucose (2 mM) except where high glucose (20 mM) is indicated (n = 4). Data shown are from HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

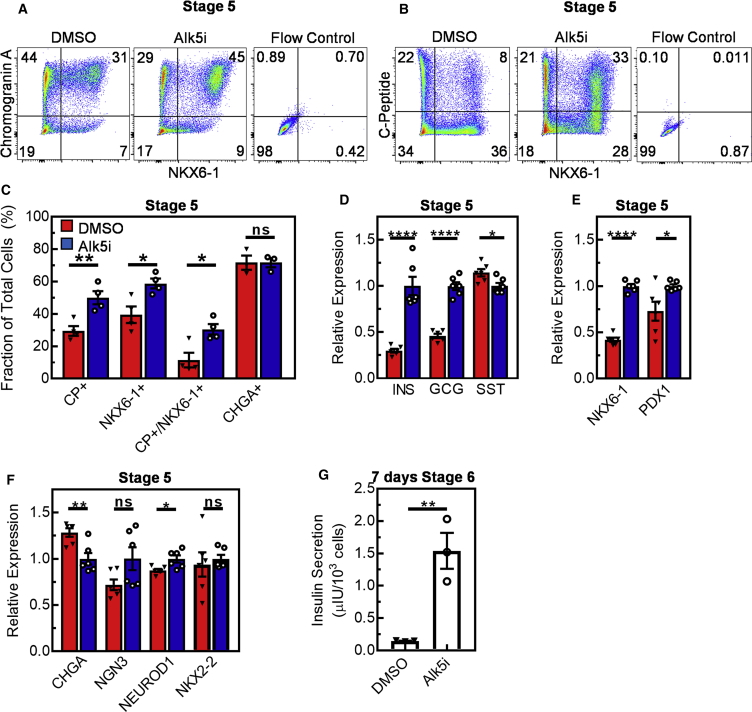

Finally, we studied the role of Alk5i during stage 5 of differentiation to evaluate its effects on differentiation toward pancreatic endocrine cells, as it had been used previously for endocrine induction (Millman et al., 2016, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Rezania et al., 2014, Russ et al., 2015, Zhu et al., 2016). These experiments were performed as outlined in Figure 1A in the presence or absence of Alk5i. We observed that the fraction of cells differentiated to endocrine cells (CHGA+) was unchanged but the fraction of cells differentiated to a C-peptide+ phenotype was decreased by omitting Alk5i (Figures 7A–7C). Similarly, the fraction of cells co-expressing C-peptide and NKX6-1, an important transcription factor for specifying β cells (Rezania et al., 2013, Rieck et al., 2012), was decreased by omitting Alk5i. INS and GCG gene expression decreased with Alk5i omission, but surprisingly SST expression was slightly increased (Figure 7D). Expression of NKX6-1 and PDX1 were reduced without Alk5i (Figure 7E), while expression of several pancreatic endocrine markers were either unchanged or only slightly changed (Figure 7F). To further test the importance of Alk5i during stage 5, cells treated with or without Alk5i during stage 5 were further cultured for 7 days in stage 6 without Alk5i nor cluster resizing, and insulin secretion was substantially higher in cells treated with Alk5i during stage 5 (Figure 7G). Taken together, these data show that Alk5i treatment during stage 5 positively influences specification to β-like cell fate, not necessary to specify endocrine cells, and is necessary for high insulin secretion of resulting SC-β cells. In addition, these observations illustrate the importance of stage-specific treatment of the TGF-β signaling-inhibitor Alk5i to both generate and functionally mature SC-β cells.

Figure 7.

Alk5i Treatment during Stage 5 Is Important for Generation of Insulin-Producing Cells

(A and B) Representative flow cytometric dot plots of dispersed stage 5 clusters immunostained for CHGA and NKX6-1 (A) or C-peptide and NKX6-1 (B).

(C) Fraction of cells expressing the indicated markers (n = 4 except CHGA, which was n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 or n.s., not significant by unpaired two-way t test.

(D–F) Real-time PCR measuring relative gene expression of stage 5 cells cultured with DMSO or Alk5i for pancreatic hormones (D), β cell markers (E), or endocrine markers (F) (n = 6). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, or n.s., not significant by unpaired two-way t test.

(G) Human insulin secretion at 20 mM glucose of cells cultured in stage 5 in either DMSO or Alk5i plus an additional 7days in stage 6 without Alk5i and without cluster resizing (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01 by unpaired two-way t test. All data shown are from HUES8.

Data are shown as means ± SEM.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that enhanced functional maturation of SC-β cells is achieved with our six-stage differentiation strategy. These cells secrete a large amount of insulin and are glucose responsive, displaying both first- and second-phase insulin release. This differentiation procedure generates almost pure endocrine cell populations without selection or sorting, and most cells express C-peptide and other β cell markers. Upon transplantation into STZ-treated mice, glucose tolerance is rapidly restored and function persists for months. These SC-β cells respond to multiple secretagogues in a perifusion assay. We found modulating TGF-β signaling to be crucial for success, with inhibition during stage 5 increasing SC-β cell differentiation but inhibition during stage 6 reducing function and insulin content. Permitting TGF-β signaling during stage 6 was necessary for robust dynamic function.

Even though the protocols reported previously by us (Pagliuca et al., 2014) and others (Rezania et al., 2014) both generated β-like cells with much greater function and better marker expression than prior reports (Hrvatin et al., 2014), robust first- and second-phase insulin release in response to glucose stimulation was not observed. Both protocols inhibited TGF-β signaling during the final stage of differentiation, and many subsequent reports also include inhibitors of TGF-β signaling without demonstrating proper dynamic function (Ghazizadeh et al., 2017, Millman et al., 2016, Song and Millman, 2016, Sui et al., 2018, Vegas et al., 2016, Zeng et al., 2016, Zhu et al., 2016). However, a major observation of the current study is that correct modulation of TGF-β signaling during key cell transition and maturation steps is critical for successful differentiation to functional SC-β cells, with permitting TGF-β signaling being required for improved functional maturation during stage 6.

SC-β cells in this report were able to control glucose in STZ-treated mice rapidly within 10 days. Prior reports with in-vitro-differentiated β-like cells without demonstrated robust dynamic function have successfully controlled blood sugar with a glucose tolerance test or demonstrated glucose-responsive serum human insulin/C-peptide in mice after several weeks or months (Millman et al., 2016, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Rezania et al., 2014, Vegas et al., 2016, Zhu et al., 2016), but our SC-β cells had higher measured human insulin levels compared with Pagliuca et al. (2014) with equal cell numbers transplanted. Vegas et al. (2016) did demonstrate reduced blood glucose within a week but did not test glucose tolerance or measure human insulin until much later. Currently, a key limitation in diabetes cell replacement therapy is the need for sustainable source of functional β cells (Weir et al., 2011), and improving the quality of SC-β cells to be transplanted helps overcome this challenge (Tomei et al., 2015). Transplantation of immature pancreatic progenitor cells are an alternative cell type that has shown promise in rodents, where some cells undergo in vivo maturation to β-like cells after several months (Bruin et al., 2015, Kroon et al., 2008, Millman et al., 2016, Rezania et al., 2012). However, the mechanism is unknown, and how successful the process would be in humans is not clear, especially since the efficiency between rats and mice is very different (Bruin et al., 2015). Our process for making SC-β cells is scalable, with the cells grown and differentiated as clusters in suspension culture. The use of clusters in suspension culture allows flexibility for many applications, such as large animal transplantation studies or therapy (order 109 cells) (McCall and Shapiro, 2012, Shapiro et al., 2006) or studying patient cells and disease pathology (<108 cells) (Kudva et al., 2012, Maehr et al., 2009, Millman et al., 2016, Shang et al., 2014, Simsek et al., 2016, Teo et al., 2013).

Our strategy enhances the utility of in-vitro-differentiated SC-β cells for drug screening due to their improved kinetics. Proper dynamic insulin release is an important feature of β cell metabolism that is commonly lost in diabetes (Caumo and Luzi, 2004, Del Prato and Tiengo, 2001, Seino et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2001). We have established a renewable resource of SC-β cells with dynamic insulin release that can be used to better study the mechanism of β cell failure in diabetes and demonstrated their response to several secretagogues.

The culmination of numerous modifications to the protocol produced SC-β cells exhibiting dynamic glucose response. In addition to modulating TGF-β signaling, other notable changes included the removal of serum, reducing cluster size, and the lack of several additional factors (T3, N-acetyl cysteine, Trolox, H1152, and R428) used in other reports during the last stage. We hope that these insights provide the basis for further innovations for differentiating SC-β cells and improving function, especially as a recent report indicates there may be multiple pathways to β cells (Petersen et al., 2017). While we demonstrate reproducibility of the protocol across multiple cell lines, marker expression and function were greatest in the HUES8 cell line. As this protocol was initially developed for this line, we suspect additional optimization to be beneficial when applying this protocol to additional lines.

Even with these functional improvements over previously published SC-β cells, islets averaged higher insulin secretion and glucose stimulation, particularly second-phase release. These differences are more pronounced when comparing the best human islets in this dataset, which secreted 21 μIU/103 cells and had stimulated insulin increase of 11, to the best stage 6 cells, which secreted 9 μIU/103 cells and had a stimulated increase of 5, in static assays. Our stage 6 cells had reduced average insulin secretion at low glucose in static assays, but elevated insulin secretion at low glucose in perifusion assays compared with islets on average, perhaps due to paracrine differences. Comparisons with islets were complicated due to donor-to-donor variation, which has been observed previously (Kayton et al., 2015, Lyon et al., 2016, Pagliuca et al., 2014). We do note that islets in our study were typically more functional than in other studies (Ghazizadeh et al., 2017, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Rezania et al., 2014, Russ et al., 2015, Sui et al., 2018), which we believe is important to rigorously benchmark SC-β cells. In addition, some islet genes remain underexpressed in our cells. Furthermore, while the data we generated with the Pagliuca protocol were within the range of data presented in the 2014 report, we acknowledge that the static GSIS values were lower on average, likely due in part to technical differences in how the assays were performed. Another potential contributor is batch-to-batch variability, as stated in the 2014 report, which could be caused by the use of different lots of serum during stage 6 and was eliminated in our protocol. Even with these difficulties and insights, we acknowledge that even further maturation of SC-β cells is possible, building on this report and the original 2014 breakthroughs.

This study provides insights into the role of TGF-β signaling in functional maturation. Prior reports are unclear on this topic, with some showing TGF-β inhibition to benefit (Lin et al., 2009) and others to harm (Totsuka et al., 1989) secretion. Inhibition has been shown to promote replication (Dhawan et al., 2016), protect against stress-induced loss of phenotype (Blum et al., 2014, Millman et al., 2016), and reduce apoptosis in a GLIS3 knockout model (Amin et al., 2018). Interestingly, we also observed that removal of Alk5i during stage 5 does not affect the overall percentage of cells expressing CHGA, but influences the expression of INS, GCG, and SST, suggesting a role in TGF-β signaling in endocrine subtype specification. It is important to note that we did not identify the downstream effectors of TGF-β signaling responsible for the reported phenotypes, and further study is warranted.

Experimental Procedures

Culture of Undifferentiated Cells

Undifferentiated hPSC lines were cultured using mTeSR1 in 30-mL spinner flasks on a rotator stir plate spinning at 60 rpm in a humidified 5% CO2 37°C incubator. Cells were passaged every 3–4 days by single-cell dispersion.

Cell Line Differentiation

To initiate differentiation, undifferentiated cells were single-cell dispersed and seeded at 6 × 105 cells/mL in a 30-mL spinner flask. Cells were cultured for 72 hr in mTeSR1 and then cultured in the differentiation media for 6 stages outlined in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures, except where otherwise noted. Cells were resized the first day of stage 6 by incubating in Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent and passing through a cell strainer. Assessment assays were performed between 10 and 16 days of stage 6 unless otherwise stated.

Static GSIS

Clusters were incubated at 2 mM glucose for a 1 hr equilibration in a transwell. The transwell was then drained and transferred into a new 2 mM glucose well, incubated 1 hr (first challenge), then transferred into a solution of 2, 5.6, 11.1, or 20 mM glucose (second challenge), incubated 1 hr, and then normalized by cell count and insulin quantified with ELISA.

Dynamic GSIS

A perifusion system was assembled as reported previously (Bentsi-Barnes et al., 2011). Stage 6 clusters and islets were assayed with effluent collected at a 100-μL/min flow rate every 2–4 min, exposed to the indicated secretagogues, including glucose, Extendin-4, IBMX, tolbutamide, L-arginine, and KCl. After sample collection, DNA and insulin were quantified.

Transplantation Studies

All animal work was performed in accordance to Washington University International Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. Mice were injected with ∼5 × 106 stage 6 cells under the kidney capsule (Pagliuca et al., 2014) and monitored up to 6 months by performing glucose tolerance tests and in vivo GSIS.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using GraphPad Prism using the indicated statistical test. Slope and error in slope was calculated with the LINEST function in Excel. Data shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted or box-and-whiskers showing minimum to maximum point range, as indicated. n indicates the total number of independent experiments.

Author Contributions

L.V.C., J.S., and J.R.M. conceived of the experimental design. All authors contributed to the in vitro experiments. L.V.C., K.G.M., and J.R.M. performed all in vivo experiments. L.V.C. and J.R.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (5R01DK114233), JDRF Career Development Award (5-CDA-2017-391-A-N), Washington University Diabetes Research Center Pilot & Feasibility Award and Imaging Scholarship (5P30DK020579), Washington University Center of Regenerative Medicine, and startup funds from Washington University School of Medicine Department of Medicine. L.V.C. was supported by the NIH (2R25GM103757). K.G.M. was supported by the NIH (5T32DK108742). N.J.H. was supported by the NIH (5T32DK007120). We thank John Dean, Lisa Gutgesell, and Eli Silvert for providing technical assistance and the Amgen Scholars program for supporting Lisa and Eli. Confocal microscopy was performed through the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging (WUCCI). The viral work was supported by the Hope Center Viral Vectors Core at Washington University School of Medicine. L.V.C., J.S., and J.R.M. are inventors on related patent applications.

Published: January 17, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures and seven figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.12.012.

Supplemental Information

References

- Amin S., Cook B., Zhou T., Ghazizadeh Z., Lis R., Zhang T., Khalaj M., Crespo M., Perera M., Xiang J.Z. Discovery of a drug candidate for GLIS3-associated diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2681. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04918-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arda H.E., Li L., Tsai J., Torre E.A., Rosli Y., Peiris H., Spitale R.C., Dai C., Gu X., Qu K. Age-dependent pancreatic gene regulation reveals mechanisms governing human beta cell function. Cell Metab. 2016;23:909–920. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron M., Veres A., Wolock S.L., Faust A.L., Gaujoux R., Vetere A., Ryu J.H., Wagner B.K., Shen-Orr S.S., Klein A.M. A single-cell transcriptomic map of the human and mouse pancreas reveals inter- and intra-cell population structure. Cell Syst. 2016;3:346–360.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin M.D., Barton F.B., Heitman A., Harmon J.V., Kandaswamy R., Balamurugan A.N., Sutherland D.E., Alejandro R., Hering B.J. Potent induction immunotherapy promotes long-term insulin independence after islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:1576–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsi-Barnes K., Doyle M.E., Abad D., Kandeel F., Al-Abdullah I. Detailed protocol for evaluation of dynamic perifusion of human islets to assess beta-cell function. Islets. 2011;3:284–290. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.5.15938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum B., Roose A.N., Barrandon O., Maehr R., Arvanites A.C., Davidow L.S., Davis J.C., Peterson Q.P., Rubin L.L., Melton D.A. Reversal of beta cell de-differentiation by a small molecule inhibitor of the TGFbeta pathway. Elife. 2014;3:e02809. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S., Weir G.C. New sources of pancreatic beta-cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:857–861. doi: 10.1038/nbt1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruin J.E., Asadi A., Fox J.K., Erener S., Rezania A., Kieffer T.J. Accelerated maturation of human stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitor cells into insulin-secreting cells in immunodeficient rats relative to mice. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:1081–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caumo A., Luzi L. First-phase insulin secretion: does it exist in real life? Considerations on shape and function. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;287:E371–E385. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00139.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour K., Bang A., Eliazer S., Kelly O., Agulnick A., Smart N., Moorman M., Kroon E., Carpenter M., Baetge E. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1793. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour K.A., Agulnick A.D., Eliazer S., Kelly O.G., Kroon E., Baetge E.E. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prato S., Tiengo A. The importance of first-phase insulin secretion: implications for the therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2001;17:164–174. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S., Dirice E., Kulkarni R.N., Bhushan A. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling promotes human pancreatic beta-cell replication. Diabetes. 2016;65:1208–1218. doi: 10.2337/db15-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazizadeh Z., Kao D.I., Amin S., Cook B., Rao S., Zhou T., Zhang T., Xiang Z., Kenyon R., Kaymakcalan O. ROCKII inhibition promotes the maturation of human pancreatic beta-like cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:298. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering B.J., Clarke W.R., Bridges N.D., Eggerman T.L., Alejandro R., Bellin M.D., Chaloner K., Czarniecki C.W., Goldstein J.S., Hunsicker L.G. Phase 3 trial of transplantation of human islets in type 1 diabetes complicated by severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1230–1240. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrvatin S., O'Donnell C.W., Deng F., Millman J.R., Pagliuca F.W., DiIorio P., Rezania A., Gifford D.K., Melton D.A. Differentiated human stem cells resemble fetal, not adult, beta cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:3038–3043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400709111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayton N.S., Poffenberger G., Henske J., Dai C., Thompson C., Aramandla R., Shostak A., Nicholson W., Brissova M., Bush W.S. Human islet preparations distributed for research exhibit a variety of insulin-secretory profiles. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;308:E592–E602. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00437.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E., Martinson L., Kadoya K., Bang A., Kelly O., Eliazer S., Young H., Richardson M., Smart N., Cunningham J. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:443–495. doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudva Y.C., Ohmine S., Greder L.V., Dutton J.R., Armstrong A., De Lamo J.G., Khan Y.K., Thatava T., Hasegawa M., Fusaki N. Transgene-free disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Stem Cell Transl. Med. 2012;1:451–461. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy P.E., Kostianovsky M. Method for the isolation of intact islets of Langerhans from the rat pancreas. Diabetes. 1967;16:35–39. doi: 10.2337/diab.16.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.M., Lee J.H., Yadav H., Kamaraju A.K., Liu E., Zhigang D., Vieira A., Kim S.J., Collins H., Matschinsky F. Transforming growth factor-beta/Smad3 signaling regulates insulin gene transcription and pancreatic islet beta-cell function. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12246–12257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805379200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon J., Manning Fox J.E., Spigelman A.F., Kim R., Smith N., O'Gorman D., Kin T., Shapiro A.M., Rajotte R.V., MacDonald P.E. Research-focused isolation of human islets from donors with and without diabetes at the Alberta Diabetes Institute isletcore. Endocrinology. 2016;157:560–569. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehr R., Chen S., Snitow M., Ludwig T., Yagasaki L., Goland R., Leibel R.L., Melton D.A. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:15768–15773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906894106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C.D., Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall M., Shapiro A.M. Update on islet transplantation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a007823. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman J.R., Pagliuca F.W. Autologous pluripotent stem cell-derived beta-like cells for diabetes cellular therapy. Diabetes. 2017;66:1111–1120. doi: 10.2337/db16-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman J.R., Xie C., Van Dervort A., Gurtler M., Pagliuca F.W., Melton D.A. Generation of stem cell-derived beta-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11463. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan D.M. Long-term complications of diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:1676–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306103282306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nostro M.C., Sarangi F., Yang C., Holland A., Elefanty A.G., Stanley E.G., Greiner D.L., Keller G. Efficient generation of NKX6-1(+) pancreatic progenitors from multiple human pluripotent stem cell lines. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuca F.W., Millman J.R., Gurtler M., Segel M., Van Dervort A., Ryu J.H., Peterson Q.P., Greiner D., Melton D.A. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M.B.K., Azad A., Ingvorsen C., Hess K., Hansson M., Grapin-Botton A., Honore C. Single-cell gene expression analysis of a human ESC model of pancreatic endocrine development reveals different paths to beta-cell differentiation. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:1246–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A., Bruin J.E., Arora P., Rubin A., Batushansky I., Asadi A., O'Dwyer S., Quiskamp N., Mojibian M., Albrecht T. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:1121–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A., Bruin J.E., Riedel M.J., Mojibian M., Asadi A., Xu J., Gauvin R., Narayan K., Karanu F., O'Neil J.J. Maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitors into functional islets capable of treating pre-existing diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:2016–2029. doi: 10.2337/db11-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A., Bruin J.E., Xu J., Narayan K., Fox J.K., O'Neil J.J., Kieffer T.J. Enrichment of human embryonic stem cell-derived NKX6.1-expressing pancreatic progenitor cells accelerates the maturation of insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2432–2442. doi: 10.1002/stem.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieck S., Bankaitis E.D., Wright C.V. Lineage determinants in early endocrine development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;23:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ H.A., Parent A.V., Ringler J.J., Hennings T.G., Nair G.G., Shveygert M., Guo T., Puri S., Haataja L., Cirulli V. Controlled induction of human pancreatic progenitors produces functional beta-like cells in vitro. EMBO J. 2015;34:1759–1772. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharp D.W., Lacy P.E., Santiago J.V., McCullough C.S., Weide L.G., Falqui L., Marchetti P., Gingerich R.L., Jaffe A.S., Cryer P.E. Insulin independence after islet transplantation into type I diabetic patient. Diabetes. 1990;39:515–518. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S., Shibasaki T., Minami K. Dynamics of insulin secretion and the clinical implications for obesity and diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2118–2125. doi: 10.1172/JCI45680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L., Hua H., Foo K., Martinez H., Watanabe K., Zimmer M., Kahler D.J., Freeby M., Chung W., LeDuc C. β-Cell dysfunction due to increased ER stress in a stem cell model of Wolfram syndrome. Diabetes. 2014;63:923–933. doi: 10.2337/db13-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro A.M., Lakey J.R., Ryan E.A., Korbutt G.S., Toth E., Warnock G.L., Kneteman N.M., Rajotte R.V. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro A.M., Ricordi C., Hering B.J., Auchincloss H., Lindblad R., Robertson R.P., Secchi A., Brendel M.D., Berney T., Brennan D.C. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsek S., Zhou T., Robinson C.L., Tsai S.Y., Crespo M., Amin S., Lin X., Hon J., Evans T., Chen S. Modeling cystic fibrosis using pluripotent stem cell-derived human pancreatic ductal epithelial cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016;5:572–579. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Millman J.R. Economic 3D-printing approach for transplantation of human stem cell-derived beta-like cells. Biofabrication. 2016;9:015002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/9/1/015002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes A., Preston S.H. Deaths attributable to diabetes in the United States: comparison of data sources and estimation approaches. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui L., Danzl N., Campbell S.R., Viola R., Williams D., Xing Y., Wang Y., Phillips N., Poffenberger G., Johannesson B. -Cell replacement in mice using human type 1 diabetes nuclear transfer embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2018;67:26–35. doi: 10.2337/db17-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo A.K., Windmueller R., Johansson B.B., Dirice E., Njolstad P.R., Tjora E., Raeder H., Kulkarni R.N. Derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with maturity onset diabetes of the young. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:5353–5356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.428979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomei A.A., Villa C., Ricordi C. Development of an encapsulated stem cell-based therapy for diabetes. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015;15:1321–1336. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1055242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsuka Y., Tabuchi M., Kojima I., Eto Y., Shibai H., Ogata E. Stimulation of insulin secretion by transforming growth factor-beta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;158:1060–1065. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritschler S., Theis F.J., Lickert H., Bottcher A. Systematic single-cell analysis provides new insights into heterogeneity and plasticity of the pancreas. Mol. Metab. 2017;6:974–990. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegas A.J., Veiseh O., Gurtler M., Millman J.R., Pagliuca F.W., Bader A.R., Doloff J.C., Li J., Chen M., Olejnik K. Long-term glycemic control using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell-derived beta cells in immune-competent mice. Nat. Med. 2016;22:306–311. doi: 10.1038/nm.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir G.C., Cavelti-Weder C., Bonner-Weir S. Stem cell approaches for diabetes: towards beta cell replacement. Genome Med. 2011;3:61. doi: 10.1186/gm277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y., Kim J., Okamoto H., Ni M., Wei Y., Adler C., Murphy A.J., Yancopoulos G.D., Lin C., Gromada J. RNA sequencing of single human islet cells reveals type 2 diabetes genes. Cell Metab. 2016;24:608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H., Guo M., Zhou T., Tan L., Chong C.N., Zhang T., Dong X., Xiang J.Z., Yu A.S., Yue L. An isogenic human ESC platform for functional evaluation of genome-wide-association-study-identified diabetes genes and drug discovery. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:326–340. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.Y., Baffy G., Perret P., Krauss S., Peroni O., Grujic D., Hagen T., Vidal-Puig A.J., Boss O., Kim Y.B. Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2001;105:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Russ H.A., Wang X., Zhang M., Ma T., Xu T., Tang S., Hebrok M., Ding S. Human pancreatic beta-like cells converted from fibroblasts. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10080. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.