Abstract

The p53 tumor suppressor has been studied for decades, and still there are many questions left unanswered. In this review, we first describe the current understanding of the wild-type p53 functions that determine cell survival or death, and regulation of the protein, with a particular focus on the negative regulators, the murine double minute family of proteins. We also summarize tissue-, stress-, and age-specific p53 activities and the potential underlying mechanisms. Among all p53 gene alterations identified in human cancers, p53 missense mutations predominate, suggesting an inherent biological advantage. Numerous gain-of-function activities of mutant p53 in different model systems and contexts have been identified. The emerging theme is that mutant p53, which retains a potent transcriptional activation domain, also retains the ability to modify gene transcription, albeit indirectly. Lastly, because mutant p53 stability is necessary for its gain of function, we summarize the mechanisms through which mutant p53 is specifically stabilized. A deeper understanding of the multiple pathways that impinge upon wild-type and mutant p53 activities and how these, in turn, regulate cell behavior will help identify vulnerabilities and therapeutic opportunities.

Keywords: missense mutation, gain of function, tissue specificity, stress specificity, age specificity, p53 stabilization

INTRODUCTION

The complexity of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway is astounding. Although p53 is under the radar most of the time, in response to DNA damage or cellular stress, such as metabolic, oxidative, or ribosomal stress, p53 functionally activates cellular processes that include cell cycle arrest, senescence, and cell death. In this scenario, p53 is responsible for maintaining homeostasis by repairing or eliminating cells with a damaged genome (Aylon & Oren 2016). Thus, it is the gene most often mutated in human cancers. However, in contrast to other tumor suppressors that are often deleted in cancers, the most common p53 mutations are missense mutations that result not only in loss of transcriptional activity but also in gain-of-function (GOF) activities that lead to aggressive tumor cell behaviors. Additionally, p53 has a crucial function in cell survival by promoting autophagy and metabolic restructuring in the face of starvation. The signaling pathways through which p53 functions are cell type– and context-specific, although the processes by which this occurs are still murky. This review focuses on current concepts that have evolved from in vivo studies of the p53 pathway.

p53: A STRESS RESPONSE PROTEIN

The major activity of p53 is as a transcriptional activator of a large repertoire of genes through its recognition and binding to a specific DNA sequence (Vousden & Prives 2009). p53 is present at barely detectable levels in normal cells, but in response to stimuli such as DNA damage, ribosomal stress, metabolic stress, and other abnormalities, p53 is posttranslationally modified, leading to rapid stabilization and subsequent transactivation of hundreds of genes with multiple cellular functions (Vousden & Prives 2009).

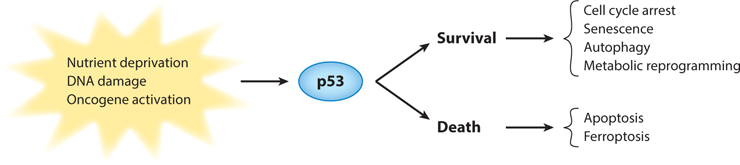

p53 transcriptionally activates multiple genes that ultimately determine whether a cell lives or dies (Figure 1) (Kenzelmann Broz et al. 2013). The first identified target of p53 was the cell cycle inhibitor CDKN1A, commonly referred to as p21, with important roles in cell cycle arrest and senescence (Brown et al. 1997, Brugarolas et al. 1995, Bunz et al. 1998, Chang et al. 1999, Deng et al. 1995, El-Deiry et al. 1993, Harper et al. 1993, Waldman et al. 1995). p21 remains one of the p53 targets most robustly activated in response to stress and, thus, serves as a great reporter. However, some p21-null mice develop tumors at a late stage (Martin-Caballero et al. 2001), and p21 is infrequently deleted in human cancers (Shiohara et al. 1994), indicating that it is not a potent tumor suppressor on its own. Perhaps the activation of p21 occurs to slow down the cell cycle enough so that cell fate can be determined. A mouse model recently developed with luciferase knocked into the p21 promoter will be useful for monitoring the p53 response in vivo (Tinkum et al. 2011). Senescence has also been examined in mouse tumor models. Restoration of p53 activity in hepatocellular carcinomas and in some soft tissue sarcomas that develop in mice in the absence of p53 resulted in tumor clearance via senescent mechanisms (Ventura et al. 2007, Xue et al. 2007). In addition, senescence occurs in response to doxorubicin treatment in a mouse model of breast cancer that retains wild-type p53 ( Jackson et al. 2012). Breast tumors with mutant p53 treated with doxorubicin did not senesce, which allowed tumor cells to traverse the cell cycle with double-strand breaks, leading to a mitotic catastrophe and improved outcomes. Senescence remains a poorly understudied p53 response that has important implications for the management of human cancers.

Figure 1.

p53 is activated in response to various stresses. In different contexts, the activation of p53 can either keep the cells alive (the survival pathway) or kill the cells (the death pathway).

In addition to cell cycle arrest and senescence, p53 can initiate other prosurvival mechanisms under certain conditions, such as autophagy in cells with limited nutrient availability, which destroys unnecessary or dysfunctional intracellular components (White 2016). Autophagy, in turn, downmodulates p53 functions to prevent cell damage and tissue degeneration (White 2016). In response to catastrophic changes in metabolism, p53 also remodels metabolic pathways for survival (Berkers et al. 2013). For example, p53 activates genes such as AMPKβ, TSC2, and PTEN, which inhibit mTOR (a sensor of nutrient supply) signaling, and TIGAR, among others, which temper aerobic glycolysis and promote oxidative phosphorylation. Finally, the ability of p53 to signal its own destruction via the activation of a potent inhibitor, Mdm2 (murine double minute 2), referred to as a feedback loop, restores normality. This ability to regulate pathways that sense and manage nutrient availability for cell survival is an important p53 response that ensures homeostasis.

p53 is also a potent inducer of different forms of cell death. In response to DNA-damaging ionizing radiation, p53 induces apoptosis in the thymus and developing central nervous system in vivo, a phenotype absent in p53-null mice (Lee et al. 2001, Lowe et al. 1993). Unrestrained p53 activity in the developing embryo through Mdm2 deletion induces apoptosis, resulting in embryonic lethality (Chavez-Reyes et al. 2003, Jones et al. 1995, Montes de Oca Luna et al. 1995). Another p53-induced cell death mechanism recently discovered, ferroptosis (an iron-mediated nonapoptotic cell death), has been implicated in tumor suppression ( Jiang et al. 2015). In addition, cells expressing a p53 polymorphism (P47S) are partially impaired for transcriptional activation and are resistant to ferroptosis ( Jennis et al. 2016). Thus, p53 functions in a cell similar to a manager of an assembly plant whose primary role is to stay vigilant, monitor the workflow, and slow down various processes to maintain a functioning facility (or cell). Importantly though, p53 as the manager has the ability to shut down everything. Further studies of the molecular factors that determine which p53-dependent response is activated and when are warranted.

Mouse models have probed the importance of cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis as mechanisms of tumor suppression. A p53 missense mutant, p53R175P (R172P in the mouse), observed in a few human cancers that eliminates the apoptotic function of p53 but retains a partial cell cycle arrest phenotype showed delayed tumor development, implicating cell cycle arrest as a tumor suppressive mechanism (Liu et al. 2004). A p53 transactivation domain mutant, p5325,26, was compromised for both G1 arrest and apoptosis, but induced senescence and delayed tumor development in an HrasV12 lung model (Brady et al. 2011), implicating senescence as a tumor-suppressive mechanism. Moreover, other mouse mutants indicated that depletion of all these phenotypes also delayed tumor development. Mice with deletion of p21 (a cell cycle arrest and senescent target of p53) and Puma and Noxa (apoptotic targets of p53) showed the absence of a tumor phenotype at a time point where all p53-null mice have died, implicating other unknown mechanisms in tumor suppression (Valente et al. 2013). 3KR mice defective in lysine acetylation of three amino acids also lacked p53-dependent senescence and apoptosis and showed delayed tumor phenotypes (Li et al. 2012). These mice retained the ability to transcriptionally activate some p53-dependent metabolic genes, implicating the regulation of metabolism as a tumor-suppressive mechanism.

The activities mentioned above make p53 a potent tumor suppressor, and p53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancers (Kandoth et al. 2013). With all of these tumor-suppressive properties, the discovery that p53-null mice were viable was remarkable (Donehower et al. 1992, Jacks et al. 1994). This observation suggests that development has built-in redundancies, so p53 loss results in normal embryos for the most part (some p53-null fetuses succumb to exencephaly, which is a rare malformation of the neural tube with massive protruding brain tissue). Thus, perhaps the normal developing embryo is somehow protected by other players such that the damage that most cells receive is not a lethal event. Or, perhaps during embryogenesis, there are more cells than required so that damaged cells can be eliminated. The developing embryo also has a readily available nutrient supply, but neonates are extremely dependent on autophagy through p53 (White 2016).

REGULATION OF WILD-TYPE p53

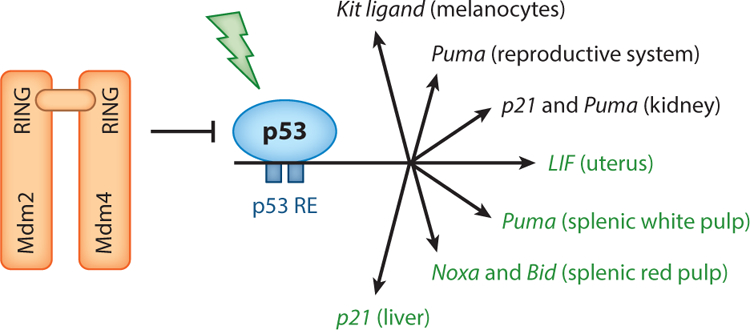

p53 is regulated at different levels by numerous players. Among all of the regulators, the Mdm family of proteins has key roles and is the most well studied in terms of p53 regulation. Mdm2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates and targets the p53 protein for proteasomal degradation (Pant & Lozano 2014). Mdm2 also inhibits p53 activity by directly binding to the p53 transcriptional activation domain 1 (TAD1) (Kussie et al. 1996) and domain 2 (TAD2) as indicated by a recent study (Shan et al. 2012). The importance of this relationship is clear because Mdm2 loss in mice leads to embryonic lethality due to induction of apoptosis at preimplantation, a phenotype that is rescued by the concomitant deletion of p53 (Chavez-Reyes et al. 2003, Jones et al. 1995, Montes de Oca Luna et al. 1995). Mdm4 (christened MdmX) is closely related to Mdm2 and binds to and inhibits the activity of the p53 transactivation domain (Shvarts et al. 1997). However, unlike Mdm2, Mdm4 does not have an enzymatically active RING domain for ubiquitination. Instead, the RING domain of Mdm4 binds Mdm2 and enhances the E3 ligase activity of Mdm2 (Sharp et al. 1999, Tanimura et al. 1999). Similar to Mdm2 loss in mice, Mdm4-null mice exhibit p53-dependent embryonic lethal phenotypes (Finch et al. 2002, Migliorini et al. 2002, Parant et al. 2001). In addition, mice with the deletion of, or a point mutation in, the RING domain of Mdm4, which disrupts interactions with Mdm2, also have embryonic lethality due to increased p53 activity, demonstrating the importance of the Mdm2–Mdm4 interaction during development (Huang et al. 2011, Pant et al. 2011). Lastly, a mouse in which only the E3 ligase activity of Mdm2 is disrupted but the interaction with Mdm4 (Mdm2Y487A/Y487A) is retained is viable, suggesting that the ability of Mdm2 and Mdm4 to mask the TAD of p53 is sufficient to keep p53 levels low (Tollini et al. 2014). However, DNA damage caused mortality of the Mdm2Y487A/Y487A mouse, which is p53 dependent. These models, among others, show that slight decreases in Mdm2 and Mdm4 activity maintain homeostasis and are compatible with life, but this activity is insufficient to prevent lethality upon DNA damage (Eischen & Lozano 2014, Gannon & Jones 2012). These in vivo studies emphasize important roles for the Mdm proteins in inhibiting p53 during development and in responding to DNA damage.

Mouse tumor models also indicate that Mdm2 and Mdm4 are drivers of tumorigenesis. A transgenic mouse model that exhibits a two- to fourfold increase in levels of Mdm2 is tumor prone, and tumor incidence increases upon haploinsufficiency of p53 ( Jones et al. 1998). Similar to the case with Mdm2, the pathological consequences of Mdm4 overexpression have been modeled using transgenic mice. Two independent Mdm4 transgenic lines developed spontaneous tumors, with sarcomas being the most frequent tumor type (Xiong et al. 2010).

As indicated above, numerous tumors either delete or mutate the p53 gene, driving tumor initiation and progression. As MDM2 and MDM4 are potent p53 inhibitors, they are frequently overexpressed or amplified in a myriad of tumors. In fact, alterations of p53 and increased levels of MDM2 or MDM4 are mutually exclusive events in many cancers, underscoring the importance of the p53 pathway in tumor suppression (Wasylishen & Lozano 2016). However, there is some tissue specificity in terms of alterations to the p53 pathway in human cancers. Alterations of the p53 gene occur in nearly 100% of ovarian serous cystadenocarcinomas and in 90% of small-cell lung cancers, but p53 mutations are absent or rare in liposarcomas and retinoblastomas. Instead, MDM2 is amplified in 80% of liposarcomas and MDM4 is amplified or overexpressed in 65% of retinoblastomas (Wasylishen & Lozano 2016). The reasons for the differences in how the p53 pathway is inactivated in tumor development are not well understood, but may reflect altered accessibility to genes resulting from chromatin modifications. Nonetheless, the p53 pathway is nonfunctional in the development of most human cancers. Differences in p53 pathway inactivation also mean that treatment options will vary. For example, tumor cells with increased MDM2 or MDM4 levels retain wild-type p53, and MDM2 inhibitors that release p53 from its shackles, such as Nutlin, have been developed and are being tested. Some antitumor activity has been observed. However, identifying the optimal dose schedule for the inhibitors is needed to achieve robust p53 activation and, at the same time, to minimize toxicity (Cheok & Lane 2016, Wang et al. 2016).

TISSUE- AND STRESS-SPECIFIC p53 ACTIVITY

Numerous p53 target genes have been identified, many of which are cell type– and tissue-specific. A p53-mediated, tissue-specific response correlates with the differential induction of p53 target genes. For example, in a study in which p53 was stabilized through global somatic deletion of Mdm2, p21 was elevated almost 200-fold in the kidney compared with 7- and 12-fold in liver and spleen, respectively (Zhang et al. 2014). And Puma, another p53 transcriptional target, was elevated 18-fold in the kidney, but was not elevated in the liver. In another study, upon γ-radiation, four apoptotic targets of p53, DR5, Bid, Puma, and Noxa, were induced in the jejunum and ileum, the two tissues most sensitive to radiation (Fei et al. 2002). In addition, differences in p53 target gene activation between the transverse and descending colon have been observed. Strikingly, even within the same tissue, different compartments exhibit distinct regulation of p53 activity. In response to γ-radiation, Puma was induced in the splenic white pulp, whereas Noxa and Bid were induced in the red pulp (Fei et al. 2002). The induction of these genes depended on p53 and correlated with the activation of caspase 3 in both compartments. Finally, in the liver, where radiation did not lead to caspase 3 activation, p21 appears to be the major p53-dependent target gene activated (Fei et al. 2002). These data indicate that cell- and tissue-specific differences exist with regard to the activation of p53 targets (Figure 2), which may determine the specific fate of different cells or tissues in response to stress.

Figure 2.

Mdm2 and Mdm4 are potent inhibitors of the p53 tumor suppressor. Loss of either or disruption of the interaction between the two results in embryo lethal phenotypes (red). Mutation of the RING domain of Mdm2 alone is viable. In response to Mdm2 loss or radiation in the adult mouse, p53 activates numerous genes (see the section titled Tissue- and Stress-Specific p53 Activity). Major genes with important tissue-specific roles are listed (labeled in green when activated by radiation), as identified in studies discussed in this review.

In addition, p53 transcriptionally activates the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) gene, which encodes a cytokine critical for embryo implantation (Hu et al. 2007). p53-null females exhibit implantation defects that are alleviated by administration of exogenous LIF. Although other tissues express LIF upon γ-radiation in a p53-dependent manner, the only defect observed in LIF-null females is failure to implant blastocysts (Hu et al. 2007, Stewart et al. 1992). These studies highlighted the importance of a single p53 target for a specific tissue: the uterus. Hypomorphic Mdm2 mice (that retain Neo in intron 1 in feedback loop–defective mice) with decreased Mdm2 levels also exhibit unique p53-dependent pathologies, such as increased skin pigmentation of the epidermis, reduction in seminiferous tubules, decreased spermatocytes in the testes, and a decreased number of ovarian follicles (Pant et al. 2016). None of the defects are rescued by deletion of p21, but the reproductive phenotypes are rescued by Puma loss, again highlighting that there are dose- and tissue-specific differences in the p53 response. Importantly, the deletion of a single, downstream target of p53, Puma, reverted a p53-dependent reproductive phenotype, whereas the skin phenotype appears to be driven by Kit ligand signaling. The Kit ligand is another p53 target expressed in melanocytes, and it is linked to their migration and accumulation (Zeron-Medina et al. 2013). These studies showed, for the first time, that the depletion of distinct p53 targets has specific outcomes in vivo. Combined, the data suggest a cell context–dependent differential induction of p53 targets, which may not be limited to the genes being examined. In fact, in another study, human HCT116 colorectal cancer cells and diploid lung fibroblast IMR90 cells showed distinct p53 genome-wide binding profiles (Botcheva & McCorkle 2014). A deeper knowledge of the p53 response in vivo may identify downstream effectors that could be used therapeutically to treat specific cancers.

Tissue- or cell-specific cofactors, which regulate p53 activity through protein–protein interactions, may also contribute to the tissue- or cell-specificity of p53 activity. A recent study showed that the carboxy terminus (C terminus) of p53 regulates gene expression in a target- and tissue-specific manner. Hamard et al. (2013) generated a murine p53 allele lacking the C-terminal 24 amino acids (p53ΔCTD). In bone marrow and thymus, p53ΔCTD is hyperactive. It increases senescence and p21 transcription in bone marrow, and it induces apoptosis and the transcription of Puma and Noxa in the thymus, suggesting that the C terminus dampens p53 activity in those tissues. In liver, however, p53ΔCTD exhibits impaired activity. In the spleen, the p53ΔCTD protein is overexpressed, suggesting that the C terminus has a role in controlling p53 protein levels in this tissue. Surprisingly, the overexpressed p53ΔCTD protein does not lead to any senescence or apoptosis phenotypes in the spleen. One explanation for the above intriguing results is that the p53 C terminus binds to cell- or tissue-specific cofactors, endowing specific p53 activity and leading to tissue-specific phenotypes. Alternatively, the p53 C terminus, which is essential for maintaining the protein structure of p53, might indirectly regulate the interaction between non-C-terminal domains of p53 and cell-specific binding partners. New in silico experiments have provided structural information about p53 in its tetrameric form and in interaction with a consensus DNA-binding site, indicating that the C terminus molds the DNA-binding domain and allows a better fit between p53 and DNA (D’Abramo et al. 2016). It will be interesting to examine whether this induced-fit mechanism is context dependent and how it is regulated, which may help understand why the p53ΔCTD protein induces the above tissue-specific phenotypes.

In addition, different DNA damage signals seem to deploy distinct mechanisms to induce functionally active p53. Early studies showed that UV, but not γ-radiation, was able to induce phosphorylation at the C-terminal serine 392 of human p53 (serine 389 in mouse p53), which significantly increased its DNA-binding activity (Kapoor & Lozano 1998, Lu et al. 1998). Phosphorylation of p53 has been implicated in regulating protein–protein interactions. As UV and γ-radiation cause different kinds of DNA lesions (bulky adducts versus strand breaks, respectively) and trigger different repair machinery (nucleotide excision repair versus base excision repair, respectively), it is possible that different site-specific modifications of p53 allow differential interaction with proteins involved in a specific DNA repair pathway. In addition, although both UV and γ-radiation stabilize p53, ubiquitin–p53 conjugates are detected only in γ-irradiated RKO and U2OS cells (Maki & Howley 1997), suggesting that the UV, but not γ-radiation–induced stabilization of p53 results from a loss of p53 ubiquitination.

p53 ACTIVITY AS A FUNCTION OF AGE

The role of p53 in aging remains controversial. Mice carrying an additional copy of the whole p53 genomic region were remarkably resistant to tumor development but aged normally (Garcia-Cao et al. 2002). In contrast, mice possessing increased constitutive activity of p53, through the expression of an artificial (p53m) or naturally occurring (p44) amino-terminal truncated form of p53 in the presence of wild-type p53, display early aging-associated phenotypes and have a shortened life span (Maier et al. 2004, Tyner et al. 2002). In contrast, mice carrying C-terminal truncated p53, p53ΔCTD (Hamard et al. 2013) or p53Δ31 (Simeonova et al. 2013), do not have an aging phenotype, even though they exhibit increased p53 activity in a lot of tissues. Similarly, mice with mutated p53 response elements in the Mdm2 promoter display an elevated p53 DNA damage response compared with normal mice, but age normally (Pant et al. 2013). These discrepancies indicate there are special roles in aging for the short forms of p53 that lack the amino terminus. Indeed, Maier et al. (2004) showed that activation by p44—a p53 protein that lacks the amino terminus owing to initiation at an internal methionine (codon 41)—altered p53-dependent gene expression, including increasing IGF-1 signaling. Persistent IGF-1 signaling caused sustained ERK activity, resulting in senescence. In addition, in mice, p44 promoted the phosphorylation of tau, the microtubule-binding protein (Pehar et al. 2010, 2014). Noteworthy, the hyperphosphorylation of tau plays critical parts in the development of neurodegenerative disease (Wang & Mandelkow 2016). Because the p53 amino terminus provides interacting sites for regulatory proteins, such as Mdm2 and Mdm4 (Chillemi et al. 2016), it is possible that disrupting these interactions plays an important part in aging.

On the other hand, emerging evidence suggests there is an age-dependent decrease in p53 activity. Mice treated with γ-radiation exhibited an age-associated decline in p53 functionality (Feng et al. 2007). In the same study, the function of the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase was found to decline significantly with age as well, which may explain the decline of the p53 response to radiation because ATM phosphorylates and activates p53 (Feng et al. 2007). Thus, it has been suggested that the age-associated decline in ATM and p53 signaling functions in mice provides a potential mechanism for age-associated increases in cancer rates. In another study, in which Mdm2 was deleted globally in adult mice, the loss of Mdm2 caused less severe symptoms in old adult mice compared with those in young mice (Zhang et al. 2014). These pathologies resulting from Mdm2 loss were p53-dependent. At a molecular level, the transcripts of Bbc3 (Puma), Cdkn1a ( p21), and all of the senescence markers examined were much less efficiently activated in old mice. Interestingly, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays showed that in old mice p53 had poorer access to its binding sites on target promoters, which could, at least partially, account for the decreased sensitivity of p53 (Zhang et al. 2014). Epigenetic changes in nucleosomes occurring as a function of age are a potential reason for the decreased accessibility of p53 to its target promoters in old mice. In fact, various studies have demonstrated that the deregulation of DNA methylation is a common feature of aging. During the adult life span, methylation tends to decrease in repetitive elements (Bollati et al. 2009, Talens et al. 2012), but increase in the CpG islands of many key developmental genes (Bell et al. 2012, Maegawa et al. 2010, Rakyan et al. 2010, Teschendorff et al. 2010). The changes in p53 regulators occurring with age offer other potential reasons for the age-dependent decline of p53 activity.

GAIN-OF-FUNCTION ACTIVITIES OF MUTANT p53

Missense mutations account for approximately 75% of all p53 mutations in human cancers (Olivier et al. 2010, Soussi & Lozano 2005). A single base change can alter an amino acid, thus eliminating or severely compromising wild-type p53 transcriptional activity. Modification of any of five arginine residues that are hot spots for p53 mutations in human cancers disables p53 sequence-specific DNA binding (Cho et al. 1994). Moreover, signature mutations in the DNA-binding domain (some of which occur at these same hot spots) can arise through exposure to common insults, such as UV light, smoking, and exposure to aflatoxin or other chemical carcinogens (Olivier et al. 2010, Vogelstein & Kinzler 1992).

The fact that most p53 alterations in tumors are missense mutations suggests that cells expressing mutant p53 have an advantage over cells lacking p53 (Brosh & Rotter 2009). Numerous experiments have tested this hypothesis. Early experiments indicated that immortalized cells lacking p53 gained additional transforming properties upon overexpression of mutant p53 proteins (Dittmer et al. 1993). Cells expressing the most common p53 mutants, in contrast to cells lacking p53, also showed increased metastatic potential and invasiveness (Crook & Vousden 1992, Hsiao et al. 1994). In Li–Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), individuals with p53 missense mutations show a higher cancer incidence and an earlier age of tumor onset (9–15 years earlier, depending on the study) than individuals with other kinds of mutations (Birch et al. 1998, Bougeard et al. 2008, Zerdoumi et al. 2013).

The generation of p53 knockin alleles in mice provided direct in vivo evidence for the GOF activities of mutant p53. Knockin mouse models heterozygous for p53R172H and p53R270H mutations, which mimic hot spot alterations in human cancers that correspond to, respectively, amino acids 175 and 273, developed highly metastatic and invasive tumors that are not seen in p53+/− mice (Lang et al. 2004, Liu et al. 2000, Olive et al. 2004). These studies produced two other interesting observations. First, even though p53R172H heterozygous mice developed highly metastatic tumors, the survival curves were identical to those of p53+/− mice. Second, analyses of tumors from p53R172H heterozygous and homozygous mice showed that mutant p53 protein was not necessarily stable, implying that tumor-specific alterations stabilized mutant p53. In fact, analyses of normal tissue from p53R172H homozygous mice indicated that mutant p53 was not stable in normal cells (Terzian et al. 2008). To understand the implications of these data, the first question asked was whether Mdm2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets wild-type p53 for proteasomal degradation, could also regulate mutant p53. In p53R172H/R172H; Mdm2−/− mice, the loss of Mdm2 stabilized mutant p53R172H. This led to decreased tumor latency and increased metastases as compared with p53/Mdm2 double null mice (Terzian et al. 2008). Thus, in this example, the stabilization of mutant p53 led to more aggressive phenotypes than those found in mice lacking p53. Furthermore, mutant p53R172H mice treated with ionizing radiation or crossed with mice containing an activated K-Ras oncogene also showed more aggressive tumor phenotypes as compared with mice with p53-null alleles (Suh et al. 2011). Together, these studies suggest that stable mutant p53 proteins have additional activities that fuel tumor cell proliferation and invasiveness and support the GOF phenotype of mutant p53 in tumorigenesis.

MECHANISMS OF MUTANT p53 GAIN OF FUNCTION

Several mechanisms have been identified that contribute to mutant p53 GOF activities. The first mechanism discovered showed that mutant p53 proteins suppressed the tumor-suppressive activities of p53 family members p63 and p73 (Gaiddon et al. 2001, Lang et al. 2004, Olive et al. 2004). In addition, TGF-β and EGFR/integrin signaling pathways stabilized mutant p53 (p53R175H and p53R273H introduced into p53-null H1299 cells) and inhibited the function of p63, properties that were essential for the invasive nature of these cells (Adorno et al. 2009, Muller et al. 2009). These studies strengthened the evidence that mutant p53 proteins bind and disrupt p63 activities. However, p63 expression is limited to epithelial cells, and therefore, inhibition of p63 cannot explain mutant p53 GOF in tumors of mesenchymal origin. Moreover, mutant p53 was found to regulate gene expression independently of p63 and p73 in some tumors (Scian et al. 2004, Weisz et al. 2004, Xiong et al. 2014, Zalcenstein et al. 2003).

ChIP-on-chip experiments and expression arrays using SKBR3 breast cancer cells with the p53R175H mutation identified mutant p53 complexes with the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which augmented expression of survival genes and dampened expression of proapoptotic genes (Stambolsky et al. 2010). Importantly, in these experiments, an intact TAD1 was required. Using expression arrays of MDA-MB-468 (p53R273H) breast cancer cells, Freed-Pastor et al. (2012) identified increased expression of genes encoding several enzymes of the mevalonate pathway. Mutant p53-bound SREBP proteins disrupted the acinar architecture of breast epithelial cells when grown as spheroids. In these experiments, both TAD1 and 2 were required, emphasizing the impact of mutant p53 on transcriptional programs. Transcription profiling in murine pancreatic cancer cell lines with K-Ras and p53R172H mutations identified PDGFRb as an important contributor to invasion and migration properties in culture (Weissmueller et al. 2014). Mechanistically, mutant p53 inhibited the p73–NF-Y complex, which represses PDGFRb expression. In other studies, comparisons of primary osteosarcomas that had metastasized from p53R172H/+ mice to p53+/− tumors that lacked metastases identified a unique set of transcriptional changes (Xiong et al. 2014). In this system, mutant p53 bound the transcription factor Ets2 and enhanced the expression of a phospholipase, Pla2g16, the protein product of which induced migration and invasion in culture (Xiong et al. 2014). Similarly, diverse p53 mutants, not the wild type, mediated through Ets2, were found to transcriptionally upregulate nucleotide metabolism genes, leading to the proliferation and invasion of various cancer cell lines (Kollareddy et al. 2015). The suppression of one of the mutant p53 target genes, GMPS, which catalyzes the final step of de novo synthesis of GMP, abrogated the metastatic activity of a breast cancer cell line (Kollareddy et al. 2015). Lastly, ChIP sequencing experiments using LFS fibroblasts with the p53R248W mutation identified numerous promoters enriched with mutant p53 (Do et al. 2012).

Emerging evidence implicates the contribution of chromatin remodeling to the GOF phenotype of mutant p53. The SWI–SNF chromatin remodeling complex (CRC) interacts with mutant p53 proteins. The SWI–SNF CRC–mutant p53 interaction is required for mutant p53–mediated VEGFR2 gene promoter remodeling and subsequent optimal VEGFR2 expression (Pfister et al. 2015). Another chromatin-remodeling protein, Pontin, was found to preferentially bind to mutant p53 compared with wild-type p53, as determined by co-immunoprecipitation assays (Zhao et al. 2015). The interaction of Pontin with mutant p53 is crucial for the transcriptional regulation of a group of mutant p53 target genes that are associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis. However, mutant p53 can also modify chromatin by inducing the expression of chromatin regulatory genes. Zhu et al. (2015) showed that p53 mutants, not wild-type p53, bind to and upregulate chromatin regulatory genes, including the genes encoding the methyltransferases MLL1 and MLL2 and the MOZ acetyltransferase, leading to genome-wide increases of histone methylation and acetylation. Genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of MLL1 significantly slowed cell proliferation. Furthermore, upregulation of MLL1, MLL2, and MOZ was found in human tumors with p53 mutants, but not in wild-type p53 or p53-null tumors.

In summary, these data suggest that multiple pathways contribute to the GOF phenotypes of cells with mutant p53. The emerging themes by which mutant p53 exhibits its GOF are (a) through forming mutant p53 complexes with other proteins that modify their activities (p63 and p73, for example), (b) by mutant p53 interacting with other transcription factors (VDR, SREBP, and Ets2, for example) that bring a potent transcriptional activation domain to promoters not normally regulated by wild-type p53, and (c) by remodeling chromatin through interactions with chromatin remodeling proteins (SWI–SNF CRC and Pontin, for example) and inducing chromatin regulatory gene expression (MLL1, MLL2, and MOZ, for example). These mechanisms are not necessarily mutually exclusive in the genesis of different cancers and may be context dependent ( Jackson et al. 2011, Oren & Rotter 2010).

In the experiments described above, different systems were used to identify the various mechanisms of mutant p53 GOF. A breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-468, that expresses p53R273H implicated the mevalonate pathway (Freed-Pastor et al. 2012). A pancreatic tumor cell line from a mouse tumor that expresses p53R172H and K-RasG12D identified PDGFR-β as an important contributor to metastasis (Weissmueller et al. 2014). Two studies, one in an LFS fibroblast cell line that contains the p53R248W mutation and one in an osteosarcoma cell line with the p53R172H mutation (equivalent to p53R175H in humans), implicated Ets2 as a driver of invasion and metastases (Do et al. 2012, Xiong et al. 2014). The SWI–SNF CRC interactions with mutant p53 proteins were identified in multiple breast cancer cell lines with different p53 mutations. Interactions of mutant p53 with Pontin were observed in lung cancer cell lines with ectopic expression of different p53 hot spot mutations and in one breast cancer cell line with the p53R175H mutation. The MLL1, MLL2, and MOZ interactions with mutant p53 were also observed in breast cancer cell lines containing different p53 mutants. Understanding is lacking as to whether these mechanisms are specific to the type of tumor cell being studied or the kind of p53 mutation examined. Other important questions that need to be addressed are which mechanisms drive the development of invasive tumors in vivo, and at what step of the invasion–metastasis cascade does the p53 mutant effect its activities?

In addition to the observations that mutant p53 proteins exhibit GOF activities, a growing body of evidence suggests that cells may be addicted to mutant p53 expression. Experiments using small interfering RNA knockdown of mutant p53 in cancer cell lines showed there was a higher apoptotic response to drug treatment (Maddocks et al. 2013, Oren & Rotter 2010). Mutant p53 depletion experiments showed decreases in cell growth rate, viability, replication, and clonogenicity. The constitutive inhibition of mutant p53 reduced tumor growth in nude mice and reduced stromal invasion and angiogenesis (Berkers et al. 2013). Recently, Prives and colleagues (Freed-Pastor et al. 2012) showed that mutant p53 depletion in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 cells with p53R280K and MDA-MB-468 with p53R273H) in three-dimensional culture led to phenotypic reversion to more normal, differentiated structures with hollow lumens. An in vivo knockin model expressing a conditional, humanized p53R248Q mutation developed tumors, many of which regressed upon Cre-mediated removal of mutant p53 (Allen et al. 2014). In summary, these data suggest that cells with mutant p53 may be addicted to the GOF activities of mutant p53. As mutant p53 proteins have, thus far, proved undruggable (Alana et al. 2014, Basu & Murphy 2016), identifying the mechanisms driving mutant p53 GOF activities is likely to provide options for new, targeted therapies to undermine mutant p53 activities. A deeper understanding of how different p53 mutations contribute to GOF activities is important for developing new therapeutic targets and personalized treatment for cancer patients.

STABILIZATION OF MUTANT p53

Despite having different roles, wild-type and mutant p53 share the majority of regulatory factors (Terzian & Lozano 2012, Vijayakumaran et al. 2015). In this section, we focus on regulation mediated through the chaperone machinery, which in many different studies appears to be specific for mutant p53. Protein stability is the major level at which p53 is regulated. In fact, the stabilization of mutant p53 is a prerequisite for its oncogenic GOF phenotype (Suh et al. 2011, Terzian et al. 2008). The hyperstability of mutant p53 in cancer cells had been previously explained by the lack of a negative feedback loop between mutant p53 and Mdm2. However, mice engineered to express mutant p53 proteins, either with or without the wild-type allele, show high levels of mutant p53 protein expression only in tumor tissue and not in normal tissues (Lang et al. 2004, Olive et al. 2004, Terzian et al. 2008). In addition, in mice with mutated p53 response elements in the Mdm2 P2 promoter, p53 was still degraded, suggesting that the Mdm2–p53 negative feedback loop is dispensable for p53 stability (Pant et al. 2013). Therefore, in malignant cells, there must be an additional mechanism (or mechanisms) to stabilize mutant p53.

Studies have highlighted the roles of chaperone heat-shock proteins (HSPs) in stabilizing mutant p53 in cancer cells. The molecular chaperone machinery, including HSP70 and HSP90, has long been known to interact with mutant p53 (Finlay et al. 1988, Whitesell et al. 1998). Two early studies (Nagata et al. 1999, Peng et al. 2001) demonstrated that HSP90 was involved in the stabilization of mutant p53. More recently, Li et al. (2011b) showed that in contrast to wildtype p53, the mutant p53R172H proteins are engaged in complexes with the HSP90 chaperone machinery in human cancer cells, which blocks endogenous MDM2 and CHIP (C terminus of Hsp70–interacting protein) E3 ligase activities. Importantly, mutant p53 exists in a positive forward loop with HSP90; it facilitates the recruitment of HSF1, the transcriptional activator of HSP90, to its specific DNA-binding elements and stimulates transcription of HSPs, including HSP90, which further stabilize mutant p53 (Li et al. 2014). Indeed, interfering with HSP90 by downmodulating HSF1 disrupts the HSP90 chaperone machinery–mutant p53 complex and liberates mutant p53, allowing endogenous MDM2 and CHIP to degrade mutant p53 (Li et al. 2011b). In another study, HSP70 was found to partially inhibit Mdm2-mediated degradation of mutant p53 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Wiech et al. 2012).

Recently, Bcl2-associated athanogene family member 2 (BAG2) was also identified as a binding partner of the p53R172H mutant (Yue et al. 2015). BAG2 contains the BAG domain that interacts with another molecular chaperone, the heat-shock cognate protein 70 (Hsc70), and, therefore, can be considered to be a cochaperone. BAG2–mutant p53 interaction inhibited mutant p53 degradation mediated by Mdm2, and thereby led to mutant p53 accumulation in cancer cells. In addition, knockdown of BAG2 greatly abolished metastatic activity and the proliferation of cancer cells harboring various p53 mutants. Notably, BAG2 expression was found to be elevated in many types of human tumors, including colorectal cancers, lung cancers, breast cancers, and sarcomas (Yue et al. 2015). High levels of BAG2 are associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients and mutant p53 protein accumulation in human tumors.

The identification of mechanisms that protect mutant p53, as shown by the chaperone HSPs, has therapeutic significance as it implicates novel approaches to exposing mutant p53 to its negative regulators and driving its destruction. Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of HSP90 activity with 17AAG (17-allylamino-17-demethoxy-geldanamycin) induces a stronger cell death phenotype in mutant p53 compared with wild-type p53 cancer cells (Li et al. 2011b). In addition, SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid)-mediated inhibition of HDAC6, which is an essential positive regulator of HSP90, exhibits preferential cytotoxicity in mutant p53 human cancer cells rather than wild-type and null (Li et al. 2011a). Strikingly, long-term HSP90 inhibition with 17DMAG (17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) plus SAHA or the potent HSP90 inhibitor ganetespib significantly extends the survival of mice with mutant p53 but not p53-null mice (Alexandrova et al. 2015). Further identification of the mechanisms stabilizing mutant p53 in tumors will provide more opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

The p53 tumor suppressor is a multifaceted protein whose primary function is to ensure cell homeostasis. It is a potent transcriptional activator that has the ability to either keep cells alive— through cell cycle arrest, senescence, autophagy, or metabolic reprogramming—or kill cells— through apoptosis and ferroptosis (Figure 1). Often, p53 activates transcription in a tissue-specific fashion, and this activity is dampened with age. Tissue specificity needs to be explored further to determine whether any of the downstream targets are linchpins in manifesting p53 activities. However, untethered p53 activity is lethal. How can we harness this activity for tumor destruction in those tumors with a wild-type p53 gene without triggering the lethal side effects that affect normal cells? Mutant p53–expressing cells may be addicted to mutant activities, and the elimination of mutant p53 may also be beneficial for tumor destruction. In this case too, mutant p53 has numerous GOF activities and their physiological significance needs to be explored. Ultimately, targeting some of these activities may have therapeutic potential. It is time to think outside the box and expand beyond p53 to identify other critical components of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Studies were supported by NIH grants (CA47296 and CA 82577) to G.L. and the Theodore N. Law Endowment for Scientific Achievement to Y.Z.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adorno M, Cordenonsi M, Montagner M, Dupont S, Wong C, et al. 2009. A mutant-p53/Smad complex opposes p63 to empower TGFβ-induced metastasis. Cell 137:87–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alana L, Sese M, Canovas V, Punyal Y, Fernandez Y, et al. 2014. Prostate tumor OVerexpressed-1 (PTOV1) down-regulates HES1 and HEY1 notch targets genes and promotes prostate cancer progression. Mol. Cancer 13:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrova EM, Yallowitz AR, Li D, Xu S, Schulz R, et al. 2015. Improving survival by exploiting tumour dependence on stabilized mutant p53 for treatment. Nature 523:352–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MA, Andrysik Z, Dengler VL, Mellert HS, Guarnieri A, et al. 2014. Global analysis of p53-regulated transcription identifies its direct targets and unexpected regulatory mechanisms. eLife 3:e02200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylon Y, Oren M. 2016. The paradox of p53: what, how, and why? See Lozano & Levine 2016, pp. 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Basu S, Murphy ME. 2016. p53 family members regulate cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle 15:1403–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JT, Tsai PC, Yang TP, Pidsley R, Nisbet J, et al. 2012. Epigenome-wide scans identify differentially methylated regions for age and age-related phenotypes in a healthy ageing population. PLOS Genet 8:e1002629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkers CR, Maddocks OD, Cheung EC, Mor I, Vousden KH. 2013. Metabolic regulation by p53 family members. Cell Metab 18:617–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch JM, Blair V, Kelsey AM, Evans DG, Harris M, et al. 1998. Cancer phenotype correlates with constitutional TP53 genotype in families with the Li–Fraumeni syndrome. Oncogene 17:1061–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollati V, Schwartz J, Wright R, Litonjua A, Tarantini L, et al. 2009. Decline in genomic DNA methylation through aging in a cohort of elderly subjects. Mech. Ageing Dev 130:234–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botcheva K, McCorkle SR. 2014. Cell context dependent p53 genome-wide binding patterns and enrichment at repeats. PLOS ONE 9:e113492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougeard G, Sesboue R, Baert-Desurmont S, Vasseur S, Martin C, et al. 2008. Molecular basis of the Li– Fraumeni syndrome: an update from the French LFS families. J. Med. Genet 45:535–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CA, Jiang D, Mello SS, Johnson TM, Jarvis LA, et al. 2011. Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell 145:571–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh R, Rotter V. 2009. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:701–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JP, Wei W, Sedivy JM. 1997. Bypass of senescence after disruption of p21CIP1/WAF1 gene in normal diploid human fibroblasts. Science 277:831–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas J, Chandrasekaran C, Gordon JI, Beach D, Jacks T, Hannon GJ. 1995. Radiation-induced cell cycle arrest compromised by p21 deficiency. Nature 377:552–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, et al. 1998. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 282:1497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BD, Xuan Y, Broude EV, Zhu H, Schott B, et al. 1999. Role of p53 and p21waf1/cip1 in senescence-like terminal proliferation arrest induced in human tumor cells by chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene 18:4808–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Reyes A, Parant JM, Amelse LL, de Oca Luna RM, Korsmeyer SJ, Lozano G. 2003. Switching mechanisms of cell death in mdm2- and mdm4-null mice by deletion of p53 downstream targets. Cancer Res 63:8664–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheok CF, Lane DP. 2016. Exploiting the p53 pathway for therapy. See Lozano & Levine 2016, pp. 483–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chillemi G, Kehrloesser S, Bernassola F, Desideri A, Dotsch V, et al. 2016. Structural evolution and dynamics of the p53 proteins. See Lozano & Levine 2016, pp. 15–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. 1994. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science 265:346–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook T, Vousden KH. 1992. Properties of p53 mutations detected in primary and secondary cervical cancers suggest mechanisms of metastasis and involvement of environmental carcinogens. EMBO J 11:3935–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Abramo M, Besker N, Desideri A, Levine AJ, Melino G, Chillemi G. 2016. The p53 tetramer shows an induced-fit interaction of the C-terminal domain with the DNA-binding domain. Oncogene 35:3272–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. 1995. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell 82:675–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer D, Pati S, Zambetti G, Chu S, Teresky AK, et al. 1993. Gain of function mutations in p53. Nat. Genet 4:42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do PM, Varanasi L, Fan S, Li C, Kubacka I, et al. 2012. Mutant p53 cooperates with ETS2 to promote etoposide resistance. Genes Dev 26:830–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA Jr., et al. 1992. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature 356:215–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eischen CM, Lozano G. 2014. The Mdm network and its regulation of p53 activities: a rheostat of cancer risk. Hum. Mutat 35:728–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, et al. 1993. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75:817–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei P, Bernhard EJ, El-Deiry WS. 2002. Tissue-specific induction of p53 targets in vivo. Cancer Res 62:7316–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Hu W, Teresky AK, Hernando E, Cordon-Cardo C, Levine AJ. 2007. Declining p53 function in the aging process: a possible mechanism for the increased tumor incidence in older populations. PNAS 104:16633–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch RA, Donoviel DB, Potter D, Shi M, Fan A, et al. 2002. Mdmx is a negative regulator of p53 activity in vivo. Cancer Res 62:3221–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Tan TH, Eliyahu D, Oren M, Levine AJ. 1988. Activating mutations for transformation by p53 produce a gene product that forms an hsc70–p53 complex with an altered half-life. Mol. Cell. Biol 8:531–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed-Pastor WA, Mizuno H, Zhao X, Langerod A, Moon SH, et al. 2012. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell 148:244–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiddon C, Lokshin M, Ahn J, Zhang T, Prives C. 2001. A subset of tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 down-regulate p63 and p73 through a direct interaction with the p53 core domain. Mol. Cell. Biol 21:1874–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon HS, Jones SN. 2012. Using mouse models to explore MDM–p53 signaling in development, cell growth, and tumorigenesis. Genes Cancer 3:209–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cao I, Garcia-Cao M, Martin-Caballero J, Criado LM, Klatt P, et al. 2002. “Super p53” mice exhibit enhanced DNA damage response, are tumor resistant and age normally. EMBO J 21:6225–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamard PJ, Barthelery N, Hogstad B, Mungamuri SK, Tonnessen CA, et al. 2013. The C terminus of p53 regulates gene expression by multiple mechanisms in a target- and tissue-specific manner in vivo. Genes Dev 27:1868–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. 1993. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75:805–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao M, Low J, Dorn E, Ku D, Pattengale P, et al. 1994. Gain-of-function mutations of the p53 gene induce lymphohematopoietic metastatic potential and tissue invasiveness. Am. J. Pathol 145:702–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Feng Z, Teresky AK, Levine AJ. 2007. p53 regulates maternal reproduction through LIF. Nature 450:721–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yan Z, Liao X, Li Y, Yang J, et al. 2011. The p53 inhibitors MDM2/MDMX complex is required for control of p53 activity in vivo. PNAS 108:12001–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, et al. 1994. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr. Biol 4:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JG, Pant V, Li Q, Chang LL, Quintas-Cardama A, et al. 2012. p53-mediated senescence impairs the apoptotic response to chemotherapy and clinical outcome in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 21:793–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JG, Post SM, Lozano G. 2011. Regulation of tissue- and stimulus-specific cell fate decisions by p53 in vivo. J. Pathol 223:127–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennis M, Kung CP, Basu S, Budina-Kolomets A, Leu JI, et al. 2016. An African-specific polymorphism in the TP53 gene impairs p53 tumor suppressor function in a mouse model. Genes Dev 30:918–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, et al. 2015. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 520:57–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SN, Hancock AR, Vogel H, Donehower LA, Bradley A. 1998. Overexpression of Mdm2 in mice reveals a p53-independent role for Mdm2 in tumorigenesis. PNAS 95:15608–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. 1995. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature 378:206–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, et al. 2013. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 502:333–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Lozano G. 1998. Functional activation of p53 via phosphorylation following DNA damage by UV but not γ radiation. PNAS 95:2834–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenzelmann Broz D, Spano Mello S, Bieging KT, Jiang D, Dusek RL, et al. 2013. Global genomic profiling reveals an extensive p53-regulated autophagy program contributing to key p53 responses. Genes Dev 27:1016–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollareddy M, Dimitrova E, Vallabhaneni KC, Chan A, Le T, et al. 2015. Regulation of nucleotide metabolism by mutant p53 contributes to its gain-of-function activities. Nat. Commun 6:7389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Moreau J, et al. 1996. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science 274: 948–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, et al. 2004. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li–Fraumeni syndrome. Cell 119:861–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Chong MJ, McKinnon PJ. 2001. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated–dependent apoptosis after genotoxic stress in the developing nervous system is determined by cellular differentiation status. J. Neurosci 21:6687–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. 2011a. SAHA shows preferential cytotoxicity in mutant p53 cancer cells by destabilizing mutant p53 through inhibition of the HDAC6–Hsp90 chaperone axis. Cell Death Differ 18:1904–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Marchenko ND, Schulz R, Fischer V, Velasco-Hernandez T, et al. 2011b. Functional inactivation of endogenous MDM2 and CHIP by HSP90 causes aberrant stabilization of mutant p53 in human cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res 9:577–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Yallowitz A, Ozog L, Marchenko N. 2014. A gain-of-function mutant p53–HSF1 feed forward circuit governs adaptation of cancer cells to proteotoxic stress. Cell Death Dis 5:e1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Kon N, Jiang L, Tan M, Ludwig T, et al. 2012. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell 149:1269–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, McDonnell TJ, Montes de Oca Luna R, Kapoor M, Mims B, et al. 2000. High metastatic potential in mice inheriting a targeted p53 missense mutation. PNAS 97:4174–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Parant JM, Lang G, Chau P, Chavez-Reyes A, et al. 2004. Chromosome stability, in the absence of apoptosis, is critical for suppression of tumorigenesis in Trp53 mutant mice. Nat. Genet 36:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SW, Schmitt EM, Smith SW, Osborne BA, Jacks T. 1993. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature 362:847–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G, Levine AJ, eds. 2016. The p53 Protein: From Cell Regulation to Cancer Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harb. Lab. Press [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Taya Y, Ikeda M, Levine AJ. 1998. Ultraviolet radiation, but not γradiation or etoposide-induced DNA damage, results in the phosphorylation of the murine p53 protein at serine-389. PNAS 95:6399–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks OD, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, et al. 2013. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 493:542–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maegawa S, Hinkal G, Kim HS, Shen L, Zhang L, et al. 2010. Widespread and tissue specific age-related DNA methylation changes in mice. Genome Res 20:332–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, Turner T, Mohammad K, et al. 2004. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev 18:306–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki CG, Howley PM. 1997. Ubiquitination of p53 and p21 is differentially affected by ionizing and UV radiation. Mol. Cell. Biol 17:355–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Garcia-Palencia P, Serrano M. 2001. Tumor susceptibility of p21(Waf1/Cip1)- deficient mice. Cancer Res 61:6234–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini D, Lazzerini Denchi E, Danovi D, Jochemsen A, Capillo M, et al. 2002. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embryonic mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol 22:5527–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. 1995. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature 378:203–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller PA, Caswell PT, Doyle B, Iwanicki MP, Tan EH, et al. 2009. Mutant p53 drives invasion by promoting integrin recycling. Cell 139:1327–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata Y, Anan T, Yoshida T, Mizukami T, Taya Y, et al. 1999. The stabilization mechanism of mutant-type p53 by impaired ubiquitination: the loss of wild-type p53 function and the hsp90 association. Oncogene 18:6037–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, et al. 2004. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li–Fraumeni syndrome. Cell 119:847–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. 2010. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2:a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M, Rotter V. 2010. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2:a001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant V, Lozano G. 2014. Limiting the power of p53 through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. Genes Dev 28:1739–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant V, Xiong S, Chau G, Tsai K, Shetty G, Lozano G. 2016. Distinct downstream targets manifest p53- dependent pathologies in mice. Oncogene In press. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant V, Xiong S, Iwakuma T, Quintas-Cardama A, Lozano G. 2011. Heterodimerization of Mdm2 and Mdm4 is critical for regulating p53 activity during embryogenesis but dispensable for p53 and Mdm2 stability. PNAS 108:11995–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant V, Xiong S, Jackson JG, Post SM, Abbas HA, et al. 2013. The p53–Mdm2 feedback loop protects against DNA damage by inhibiting p53 activity but is dispensable for p53 stability, development, and longevity. Genes Dev 27:1857–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parant J, Chavez-Reyes A, Little NA, Yan W, Reinke V, et al. 2001. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4- null mice by loss of Trp53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate p53. Nat. Genet 29:92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehar M, Ko MH, Li M, Scrable H, Puglielli L. 2014. P44, the ‘longevity-assurance’ isoform of P53, regulates tau phosphorylation and is activated in an age-dependent fashion. Aging Cell 13:449–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehar M, O’Riordan KJ, Burns-Cusato M, Andrzejewski ME, del Alcazar CG, et al. 2010. Altered longevity-assurance activity of p53:p44 in the mouse causes memory loss, neurodegeneration and premature death. Aging Cell 9:174–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J. 2001. Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization. J. Biol. Chem 276:40583–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister NT, Fomin V, Regunath K, Zhou JY, Zhou W, et al. 2015. Mutant p53 cooperates with the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to regulate VEGFR2 in breast cancer cells. Genes Dev 29:1298–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakyan VK, Down TA, Maslau S, Andrew T, Yang TP, et al. 2010. Human aging-associated DNA hypermethylation occurs preferentially at bivalent chromatin domains. Genome Res 20:434–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scian MJ, Stagliano KE, Ellis MA, Hassan S, Bowman M, et al. 2004. Modulation of gene expression by tumor-derived p53 mutants. Cancer Res 64:7447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Li DW, Bruschweiler-Li L, Bruschweiler R. 2012. Competitive binding between dynamic p53 transactivation subdomains to human MDM2 protein: implications for regulating the p53 · MDM2/MDMX interaction. J. Biol. Chem 287:30376–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DA, Kratowicz SA, Sank MJ, George DL. 1999. Stabilization of the MDM2 oncoprotein by interaction with the structurally related MDMX protein. J. Biol. Chem 274:38189–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara M, El-Deiry WS, Wada M, Nakamaki T, Takeuchi S, et al. 1994. Absence of WAF1 mutations in a variety of human malignancies. Blood 84:3781–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvarts A, Bazuine M, Dekker P, Ramos YF, Steegenga WT, et al. 1997. Isolation and identification of the human homolog of a new p53-binding protein, Mdmx. Genomics 43:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonova I, Jaber S, Draskovic I, Bardot B, Fang M, et al. 2013. Mutant mice lacking the p53 C-terminal domain model telomere syndromes. Cell Rep 3:2046–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi T, Lozano G. 2005. p53 mutation heterogeneity in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 331:834–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolsky P, Tabach Y, Fontemaggi G, Weisz L, Maor-Aloni R, et al. 2010. Modulation of the vitamin D3 response by cancer-associated mutant p53. Cancer Cell 17:273–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, et al. 1992. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359:76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh YA, Post SM, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Maccio DR, Jackson JG, et al. 2011. Multiple stress signals activate mutant p53 in vivo. Cancer Res 71:7168–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talens RP, Christensen K, Putter H, Willemsen G, Christiansen L, et al. 2012. Epigenetic variation during the adult lifespan: cross-sectional and longitudinal data on monozygotic twin pairs. Aging Cell 11:694–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura S, Ohtsuka S, Mitsui K, Shirouzu K, Yoshimura A, Ohtsubo M. 1999. MDM2 interacts with MDMX through their RING finger domains. FEBS Lett 447:5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzian T, Lozano G. 2012. Mutant p53 driven mutagenesis. In p53 in the Clinics, ed. Hainaut P, Olivier M, Wiman KG, pp. 77–93. New York: Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- Terzian T, Suh YA, Iwakuma T, Post SM, Neumann M, et al. 2008. The inherent instability of mutant p53 is alleviated by Mdm2 or p16INK4a loss. Genes Dev 22:1337–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teschendorff AE, Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ramus SJ, Weisenberger DJ, et al. 2010. Age-dependent DNA methylation of genes that are suppressed in stem cells is a hallmark of cancer. Genome Res 20:440–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkum KL, Marpegan L, White LS, Sun J, Herzog ED, et al. 2011. Bioluminescence imaging captures the expression and dynamics of endogenous p21 promoter activity in living mice and intact cells. Mol. Cell. Biol 31:3759–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollini LA, Jin A, Park J, Zhang Y. 2014. Regulation of p53 by Mdm2 E3 ligase function is dispensable in embryogenesis and development, but essential in response to DNA damage. Cancer Cell 26:235–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, et al. 2002. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature 415:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente LJ, Gray DH, Michalak EM, Pinon-Hofbauer J, Egle A, et al. 2013. p53 efficiently suppresses tumor development in the complete absence of its cell-cycle inhibitory and proapoptotic effectors p21, Puma, and Noxa. Cell Rep 3:1339–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, et al. 2007. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 445:661–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumaran R, Tan KH, Miranda PJ, Haupt S, Haupt Y. 2015. Regulation of mutant p53 protein expression. Front. Oncol 5:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. 1992. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell 70:523–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Prives C. 2009. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell 137:413–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman T, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 1995. p21 is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res 55:5187–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhao Y, Aguilar A, Bernard D, Yang C-Y. 2016. Targeting the MDM2–p53 protein–protein interaction for new cancer therapy: progress and challenges. See Lozano & Levine 2016, pp. 395–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Mandelkow E. 2016. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 17:5–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasylishen A, Lozano G. 2016. Attenuating the p53 pathway in human cancers: many means to the same end. See Lozano & Levine 2016, pp. 331–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weissmueller S, Manchado E, Saborowski M, Morris JPT, Wagenblast E, et al. 2014. Mutant p53 drives pancreatic cancer metastasis through cell-autonomous PDGF receptor β signaling. Cell 157:382–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz L, Zalcenstein A, Stambolsky P, Cohen Y, Goldfinger N, et al. 2004. Transactivation of the EGR1 gene contributes to mutant p53 gain of function. Cancer Res 64:8318–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E 2016. Autophagy and p53. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 6:a026120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell L, Sutphin PD, Pulcini EJ, Martinez JD, Cook PH. 1998. The physical association of multiple molecular chaperone proteins with mutant p53 is altered by geldanamycin, an hsp90-binding agent. Mol. Cell. Biol 18:1517–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiech M, Olszewski MB, Tracz-Gaszewska Z, Wawrzynow B, Zylicz M, Zylicz A. 2012. Molecular mechanism of mutant p53 stabilization: the role of HSP70 and MDM2. PLOS ONE 7:e51426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong S, Pant V, Suh YA, Van Pelt CS, Wang Y, et al. 2010. Spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice overexpressing the p53-negative regulator Mdm4. Cancer Res 70:7148–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong S, Tu H, Kollareddy M, Pant V, Li Q, et al. 2014. Pla2g16 phospholipase mediates gain-of-function activities of mutant p53. PNAS 111:11145–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, et al. 2007. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 445:656–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue X, Zhao Y, Liu J, Zhang C, Yu H, et al. 2015. BAG2 promotes tumorigenesis through enhancing mutant p53 protein levels and function. eLife 4:e08401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalcenstein A, Stambolsky P, Weisz L, Muller M, Wallach D, et al. 2003. Mutant p53 gain of function: repression of CD95 (Fas/APO-1) gene expression by tumor-associated p53 mutants. Oncogene 22:5667–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerdoumi Y, Aury-Landas J, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Derambure C, Sesboue R, et al. 2013. Drastic effect of germline TP53 missense mutations in Li–Fraumeni patients. Hum. Mutat 34:453–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeron-Medina J, Wang X, Repapi E, Campbell MR, Su D, et al. 2013. A polymorphic p53 response element in KIT ligand influences cancer risk and has undergone natural selection. Cell 155:410–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xiong S, Li Q, Hu S, Tashakori M, et al. 2014. Tissue-specific and age-dependent effects of global Mdm2 loss. J. Pathol 233:380–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zhang C, Yue X, Li X, Liu J, et al. 2015. Pontin, a new mutant p53-binding protein, promotes gain-of-function of mutant p53. Cell Death Differ 22:1824–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Sammons MA, Donahue G, Dou Z, Vedadi M, et al. 2015. Gain-of-function p53 mutants co-opt chromatin pathways to drive cancer growth. Nature 525:206–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]