Abstract

Childhood abuse is a major public health problem that has been linked to depression in adulthood. Although different types of childhood abuse often co-occur, few studies have examined their unique impact on negative mental health outcomes. Most studies have focused solely on the consequences of childhood physical or sexual abuse; however, it has been suggested that childhood emotional abuse is more strongly related to depression. It remains unclear which underlying psychological processes mediate the effect of childhood emotional abuse on depressive symptoms. In a cross-sectional study in 276 female college students, multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine whether childhood emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse were independently associated with depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. Subsequently, OLS regression analyses were used to determine whether emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems mediate the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms. Of all types of abuse, only emotional abuse was independently associated with depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. The effect of childhood emotional abuse on depressive symptoms was mediated by emotion dysregulation and the following domains of interpersonal problems: cold/distant and domineering/controlling. The results of the current study indicate that detection and prevention of childhood emotional abuse deserves attention from Child Protective Services. Finally, interventions that target emotion regulation skills and interpersonal skills may be beneficial in prevention of depression.

Introduction

Childhood abuse is widely acknowledged as a major public health problem with detrimental effects on adult mental health (i.e., [1, 2]). Numerous studies have associated childhood abuse with a variety of adverse effects, such as mood and anxiety disorders [1–4] and suicidal behaviors [5–7]. In particular, childhood abuse has consistently been linked to depressive disorders in adulthood in both retrospective studies [3, 8] and prospective studies (e.g., [9, 10]).

The vast majority of studies on childhood abuse have focused on the impact of either childhood sexual abuse (CSA) or childhood physical abuse (CPA) [11], linking both types of abuse to adult depression [12–15]. However, studies that examined the impact of multiple types of abuse have demonstrated childhood emotional abuse (CEA) to be even more strongly related to depression than CSA and CPA [16–19]. CEA refers to an aggressive attitude towards a child, which is not physical in nature, and may include verbal assaults on one’s sense of worth or wellbeing, or any humiliating or demeaning behavior [20]. CEA is far more prevalent than CSA and CPA: recent meta-analyses demonstrated global self-reported prevalence of 127 per 1,000 for CSA [21], 226 per 1,000 for CPA [22], and as high as 363 per 1,000 children for CEA [23].

An important limitation of previous studies on different types of childhood abuse lies in the fact that most did not address the unique impact of each type of childhood abuse, while controlling for the other types. There is substantial overlap and intercorrelation among different types of childhood abuse in community-based samples [2, 24, 25], and this co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment results in a greater likelihood of negative mental health outcomes [24, 25]. Therefore, the unique impact of each type of childhood abuse may be overestimated or distorted by the impact of other types. Hence, it is necessary to examine both the unique and collective impact of all three types of childhood abuse on negative outcomes, while adjusting for the other types. With regard to CEA, only one study examined its impact with adjustment for CSA and CPA, and found that CEA was significantly associated with depressive symptomatology in women [26].

Given the high prevalence of childhood abuse in general, and CEA in particular, it is of utmost importance to examine how they lead to an increased risk of adult depression. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to identify underlying psychological processes that may act as a mediator in this relationship, and may be useful targets for prevention of depression. Several psychological processes have been associated with both general childhood abuse (including CSA, CPA, and CEA) and depression, among which are emotion dysregulation [27] and interpersonal problems [28].

Emotion dysregulation

Recent evidence suggests that emotion dysregulation plays an important role in the relation between childhood abuse and depression [27]. Emotion regulation refers to “the processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one’s goals” ([29], pp. 27–28). In individuals with current or lifetime major depressive disorder, emotion dysregulation was found to cross-sectionally mediate the relationship between severity of general childhood abuse and depression severity [27, 30]. With regard to CEA, emotion dysregulation cross-sectionally mediated the association between CEA and depressive symptoms in studies among female college students [31], depressed inpatients [32], and low-income African-Americans [33]. The study among college students did not include CSA and CPA, whereas the latter two studies did. For CPA, no evidence was found for a relationship with depression mediated by emotion dysregulation [32, 33]. Regarding CSA, emotion dysregulation mediated the relationship with depression only in the African-American sample [33]. The adverse effect of childhood abuse on emotion dysregulation was found to be specific for CEA: CEA significantly predicted emotion dysregulation above and beyond the effects of CSA and CPA in female college students [34]. Similarly, in another college sample, CEA exclusively predicted difficulties with responding to and dealing with emotions, but not with recognizing and understanding emotions [35]. Hence, the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship with depression may be largely specific to CEA.

Although it should be noted that cross-sectional mediation provides an indication for, but not proof of the presence of an underlying mechanism, these previous findings suggest that emotion dysregulation contributes to the link between CEA and adult depression [31–33]. However, assessment of emotion dysregulation was limited in these earlier studies. Schulz et al. (2017) used a specific measure of emotion acceptance (i.e., Emotion Acceptance Questionnaire; [36]), rather than overall emotion dysregulation. Crow et al. (2014) used a relatively novel measure of emotion dysregulation with only modest evidence on psychometric properties (i.e., the 12-item version of the Emotion Dysregulation Scale; [37]). Lastly, although Coates and Messman-Moore (2008) used the widely-used Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; [38]) to measure emotion regulation, they used a latent factor comprised of only two subscales (i.e., Emotional Clarity and Access to Strategies)–thereby omitting other domains of emotion dysregulation captured by the DERS (e.g., lack of emotional awareness and non-acceptance of emotional responses). Therefore, the current study aims to confirm the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between CEA and adult depressive symptoms, utilizing a widely-used measure of overall emotion dysregulation (i.e., DERS) with good psychometric properties.

Interpersonal problems

Although research is still scarce, interpersonal problems have been suggested to be an underlying factor of the link between childhood abuse and depression [39]. Childhood abuse appears to negatively influence social relationships and interpersonal functioning, which was found for CPA [6], CSA [40, 41], and CEA [41]. However, one study in college students found no direct relationship with problems with social relationships for CEA and CPA, whereas CSA was associated with decreased social problems [35]. Individuals with a history of childhood abuse in general reported lower levels of social support in adulthood [42], more dysfunctional relationships, and an increased risk for divorce compared to others [43]. People with a history of childhood abuse have not only reported more difficulties in marital and social relationships than others, but also more interpersonal problems as measured with the widely-used Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) [44]. The IIP measures persistent difficulties that individuals experience in social relationships, and distinguishes different domains of interpersonal problems (e.g., being domineering/controlling, nonassertive, or self-sacrificing) [44, 45]. Victims of CSA reported more interpersonal difficulties than non-victims on all domains of the IIP [40]. Similarly, in a Korean sample of patients with depression and anxiety disorders, both CEA and CSA, but not CPA, were associated with interpersonal problems as measured with the IIP total score [41]. However, an important limitation of these studies lies in the fact that they did not address the unique impact of each type of childhood abuse, controlled for the other types. Therefore, the unique and collective impact of all three types of childhood abuse on interpersonal functioning remains unknown.

Interpersonal problems have not only been linked to childhood abuse, but also to depression. Recurring frustrated interpersonal dynamics may make an individual more vulnerable to depression [45]. For example, social isolation, avoidance, and submissiveness have been associated with depression [46, 47]. However, it remains unknown whether interpersonal problems mediate the link between CEA and depression, and which specific interpersonal styles as measured with the IIP play a role in this relationship. In the aforementioned study of Whiffen, Thompson and Aube [40], difficulties with being too controlling, being intimate, and being submissive cross-sectionally and partly mediated the relation between CSA and depression in women. Hence, their results suggest that these interpersonal styles partly account for the risk of depression in women with a history of CSA. Interestingly, different interpersonal styles (i.e., being unassertive and taking too much responsibility) partially mediated this relation in men [40].

Previous research has reported a gender difference regarding the associations among childhood abuse, interpersonal relationships, and depression as well. A history of childhood abuse negatively influenced women’s perceived quality of their romantic relationships, whereas this did not hold for men [43]. Furthermore, emotionally supportive social relationships were shown to be substantially more protective against a depressive disorder for women than for men [48]. Lastly, the effect of CEA on internalizing symptoms (i.e., peer problems and emotional symptoms) and mental well-being was larger for girls than for boys in a Swedish population sample [49]. Hence, although the majority of research found no gender differences regarding the prevalence of CEA [1, 23], previous findings suggest that its effect on interpersonal functioning, emotion regulation, and depression may be stronger for women compared to men. Therefore, also given women’s substantially increased risk to develop a major depressive disorder compared to men [50], this study is conducted in a female sample.

Aims

In the current study, our aims were threefold. First, we examined the collective and unique impact of childhood emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse on depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in a European sample of female college students. Based on current literature [26, 34], we hypothesized that only emotional abuse would be independently associated with depressive symptoms and emotion dysregulation, if the three types of childhood abuse were controlled for each other. Furthermore, we hypothesized that all three types of childhood abuse would be independently associated with interpersonal problems. Second, if evidence for a relationship between CEA and depression indeed existed, as hypothesized, we aimed to examine whether this relationship would be cross-sectionally mediated by emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. We hypothesized that both emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems would mediate the relationship between CEA and depressive symptoms. Finally, we aimed to explore whether specific domains of interpersonal problems could be identified as particularly important in explaining the relationship between CEA and depressive symptoms.

Materials and methods

Design and procedures

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the VU University in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in collaboration with the research department of Arkin. The data collection took place in April and May 2017. College students were recruited by research assistants through flyers posted on campus, Facebook, and online research recruitment platforms. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participants completed a set of self-report questionnaires with forced responses administered in Net-Q: an online secured survey platform. Each assessment was supervised by one of two research assistants (MSc or BSc) and took approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with €10 or 50 minutes course credit.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were: being female, being currently studying in the Netherlands, and having sufficient understanding of the Dutch language to administer self-report questionnaires. The study sample consisted of 276 female college students with a mean age of 21.7 years (SD = 2.38). As shown in Table 1, participants were predominantly born in the Netherlands (91.7%), single (66.3%), living with their parents (42.0%) or with roommates (35.1%), and studying psychology (50.4%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the total study sample (N = 276).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | ||

| Netherlands | 253 | 91.7 |

| Other European country | 12 | 4.3 |

| Non-European country | 11 | 4.0 |

| Country of birth of parents | ||

| Both Netherlands | 192 | 69.6 |

| Both Europe | 21 | 7.6 |

| One Netherlands, one non-European | 19 | 6.9 |

| Both non-European | 44 | 15.9 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 183 | 66.3 |

| In a relationship | 93 | 33.7 |

| Living situation | ||

| With parent(s)/caregiver(s) | 116 | 42.0 |

| With roommates | 97 | 35.1 |

| Alone | 36 | 13.0 |

| With partner | 26 | 9.4 |

| Other | 1 | 0.3 |

| Field of study | ||

| Psychology | 139 | 50.4 |

| Pedagogical and other social sciences | 41 | 14.9 |

| Medicine/health sciences | 24 | 8.7 |

| Management/business/economics | 23 | 8.3 |

| Communication science | 15 | 5.4 |

| Law | 12 | 4.3 |

| Natural/formal sciences | 11 | 4.0 |

| Other | 11 | 4.0 |

Measures

Demographics

The demographic characteristics age, country of birth, country of birth of parents, relationship status, living situation, and field of study were collected during the self-report assessment.

Childhood abuse

The short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF) [51, 52] was used to assess severity of CEA (i.e., verbal assaults on one’s sense of worth or wellbeing, or any humiliating or demeaning behavior), CPA (i.e., bodily assaults that posed a risk of or resulted in injury), and CSA (i.e., unwanted sexual contact or conduct). Each scale consists of 5 items, rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale with response options ranging from “Never true” to “Very often true”, with the exception of the CSA scale. Previous psychometric analyses of the Dutch version indicated that one item of the CSA scale (“During my youth, I was molested by someone”) had to be removed [52]. A total score was calculated for each scale by summing all items. The sum score of the CSA scale was multiplied by 5/4 to enable comparisons with other studies using the CTQ-SF. The sum scores of the scales were used as continuous variables to address the main research questions. The CTQ-SF manual provides cut-off scores to describe presence/absence of abuse and levels of abuse severity (none, mild, moderate, severe) for each type of childhood abuse [51]; in the current study, these cut-offs were used for descriptive purposes only. Validity and reliability of the Dutch version of the CTQ-SF are good [52, 53]. In the current study, internal consistency was good for the CEA scale (α = .80), acceptable for the CPA scale (α = .76), and excellent for the CSA scale (α = .91).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS-SR-16), a 16-item self-rated depression severity scale [54]. The questionnaire rates the severity of the DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorder [55] in the preceding seven days. Total scores range from 0 to 27. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the QIDS-SR-16 reported that the internal consistency was acceptable (α = .69 to .89), and concurrent validity with other depression scales was moderate to high [56]. In the current study, the internal consistency of the QIDS-SR-16 was acceptable (α = .76).

Emotion dysregulation

Emotion dysregulation was measured with the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [38, 57]. The DERS is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates emotion regulation difficulties across multiple domains: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Total scores range from 36 to 180. The DERS showed high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability in a student sample [38]. In the current study, the internal consistency of the DERS was excellent (α = .93).

Interpersonal problems

Interpersonal difficulties were measured with the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32): a self-report questionnaire with good internal consistency and test-retest reliability [44]. The IIP-32 consists of 32 items and comprises eight subscales related to different domains of interpersonal problems, which showed acceptable to good internal consistency in the current study: domineering/controlling (α = .68), vindictive/self-centered (α = .78), cold/distant (α = .76), socially inhibited (α = .80), nonassertive (α = .77), overly accommodating (α = .71), self-sacrificing (α = .72), and intrusive/needy (α = .74).

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (VCWE-2017-009R1). Participation in the study was voluntary, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 24.0. There were no missing values. First, univariate linear regression analyses were performed to examine associations between the continuous variables CEA, CPA, and CSA, and the outcome variables depressive symptoms (QIDS-SR-16), emotion dysregulation (DERS total score), and interpersonal problems (IIP-32 total score). Subsequently, three multiple linear regression analyses were performed in order to determine which types of childhood abuse were independently associated with these outcome variables. Assumptions for regression analyses (linearity, homoscedasticity, normality of the residuals, absence of multicollinearity) were met.

If there was evidence for an association between CEA and depressive symptoms, we proceeded with conducting mediation analyses. To test the potential mediation effects of emotion dysregulation (DERS total score) and interpersonal problems (IIP-32 total score), we performed two simple mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro [58] for SPSS, which is based on OLS regression analysis. Rijnhart, Twisk, Chinapaw, de Boer and Heymans [59] demonstrated that when analyzing simple mediation models with a continuous mediator and continuous outcome variable, OLS regression yields the same results as SEM and the potential outcomes framework. Finally, to explore whether specific domains of interpersonal problems could be identified as particularly important in explaining the relationship between CEA and depressive symptoms, we performed a multiple mediation analysis including all eight IIP-32 subscales as mediator variables. The presence and magnitude of mediation was determined by estimating the indirect effects. To test the statistical significance of the indirect effects, we used bias-corrected 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (based on 5000 bootstrap samples) as calculated by PROCESS [58]. If zero was not contained in the confidence interval, we concluded that the indirect effect was significant. To measure the mediation effect size, we used PM: the proportion of each indirect effect relative to the total effect. An alpha level of 0.05 and confidence interval of 95% were used in all analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The severity levels for each type of childhood abuse are shown in Table 2. Using the lowest CTQ-SF cut-off scores, we found that 31.5% of the participants reported CEA, 8.0% reported CPA, and 11.6% reported CSA. Descriptive statistics of the self-report measures of severity of childhood abuse, depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems are presented in Table 3. The CTQ-SF subscales showed considerable correlations. The highest correlation was found between CEA and CPA (Pearson r = .49), whereas lower correlations were found between CEA and CSA (Pearson r = .37), and CPA and CSA (Pearson r = .27). Using the QIDS-SR scoring guidelines, 59.8% of the participants reported no depressive symptoms (score 0–5), 30.1% reported mild depressive symptoms (score 6–10), 8.0% reported moderate depressive symptoms (score 11–15), and 2.1% reported (very) severe depressive symptoms (score 16+) [54]. The highest IIP-32 subscale scores were found for the domains overly accommodating, self-sacrificing, and nonassertive, whereas the lowest subscale scores were found for vindictive/self-centered, cold/distant, and domineering/controlling. This is in accordance with the female norm group described in the IIP manual [44].

Table 2. Severity levels of three types of childhood abuse in female college students (N = 276).

| Severity level (CTQ-score) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| CEA | ||

| None (5–8) | 189 | 68.5 |

| Mild (9–12) | 57 | 20.7 |

| Moderate (13–15) | 19 | 6.9 |

| Severe (16+) | 11 | 4.0 |

| CPA | ||

| None (5–7) | 254 | 92.0 |

| Mild (8–9) | 9 | 3.3 |

| Moderate (10–12) | 9 | 3.3 |

| Severe (13+) | 4 | 1.4 |

| CSA | ||

| None (5) | 244 | 88.4 |

| Mild (6–7) | 13 | 4.7 |

| Moderate (8–12) | 10 | 3.6 |

| Severe (13+) | 9 | 3.3 |

Note. CEA = childhood emotional abuse; CPA = childhood physical abuse; CSA = childhood sexual abuse.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the self-report measures of severity of childhood abuse, depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in female college students (N = 276).

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood emotional abuse (CTQ-CEA) | 7.8 | 3.4 | 5–22 |

| Childhood physical abuse (CTQ-CPA) | 5.7 | 1.8 | 5–18 |

| Childhood sexual abuse (CTQ-CSA) | 5.7 | 2.6 | 5–21 |

| Depressive symptoms (QIDS-SR) | 5.4 | 4.0 | 0–22 |

| Emotion dysregulation (DERS) | 84.9 | 19.9 | 44–139 |

| Interpersonal problems (IIP-32 total) | 34.6 | 13.9 | 3–78 |

| Vindictive/self-centered (IIP-32 subscale) | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0–15 |

| Cold/distant (IIP-32 subscale) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0–11 |

| Socially inhibited (IIP-32 subscale) | 3.6 | 3.1 | 0–14 |

| Nonassertive (IIP-32 subscale) | 5.5 | 3.3 | 0–16 |

| Overly accommodating (IIP-32 subscale) | 6.6 | 3.4 | 0–16 |

| Self-sacrificing (IIP-32 subscale) | 6.6 | 3.2 | 0–15 |

| Intrusive/needy (IIP-32 subscale) | 4.3 | 3.1 | 0–15 |

| Domineering/controlling (IIP-32 subscale) | 3.0 | 2.6 | 0–13 |

Note. CEA = childhood emotional abuse; CPA = childhood physical abuse; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; QIDS-SR = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; IIP-32 = Inventory of Interpersonal problems.

Univariate linear regression analyses

Table 4 provides the results of the univariate linear regression analyses for examining the association between three types of childhood abuse and depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. CEA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (b = 0.38, t = 5.72, p < .001, R2 = .11), emotion dysregulation (b = 1.14, t = 3.33, p = .001, R2 = .04), and interpersonal problems (b = 1.13, t = 4.81, p < .001, R2 = .08). CPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (b = 0.33, t = 2.45, p = .015, R2 = .02) and interpersonal problems (b = 1.23, t = 2.66, p = .008, R2 = .03). No other significant associations between types of childhood abuse and outcome variables existed.

Table 4. Results of univariate linear regression analyses for predicting depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in female college students (N = 276).

| QIDS-SR | DERS | IIP-32 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | |

| CEA | 0.38 (0.07) | < .001 | 1.14 (0.34) | .001 | 1.13 (0.24) | < .001 |

| CPA | 0.33 (0.13) | .015 | 0.80 (0.67) | .235 | 1.23 (0.46) | .008 |

| CSA | 0.09 (0.09) | .338 | 0.21 (0.46) | .640 | 0.49 (0.32) | .128 |

Note. CEA = childhood emotional abuse; CPA = childhood physical abuse; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; QIDS-SR = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; IIP-32 = Inventory of Interpersonal problems.

P-values indicating significance at the .05 level are shown in bold.

Multivariate linear regression analyses

The multiple linear regression analyses revealed significant overall models for depressive symptoms (F(3,272) = 11.34, p < .001, R2 = .11), emotion dysregulation (F(3,272) = 3.96, p = .009, R2 = .04), and interpersonal problems (F(3,272) = 7.73, p < .001, R2 = .08). All variance inflation factors (VIFs) were less than 1.5, indicating that multicollinearity was not present. As shown in Table 5, emotional abuse was the only form of childhood abuse that was independently associated with depressive symptoms, with emotion dysregulation, and with interpersonal problems.

Table 5. Results of multiple linear regression analyses for predicting depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in female college students (N = 276).

| QIDS-SR | DERS | IIP-32 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B [99% CI] | p | B [99% CI] | p | B [99% CI] | p | |

| CEA | 0.42 [0.26, 0.57] | < .001 | 1.33 [0.52–2.14] | .001 | 1.09 [0.54–1.65] | < .001 |

| CPA | -0.03 [-0.32, 0.27] | .866 | -0.32 [-1.82–1.19] | .681 | 0.23 [-0.80–1.26] | .662 |

| CSA | -0.11 [-0.29, 0.08] | .254 | -0.37 [1.32–0.59] | .452 | -0.08 [-0.74–0.58] | .809 |

Note. CEA = childhood emotional abuse; CPA = childhood physical abuse; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; QIDS-SR = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; IIP-32 = Inventory of Interpersonal problems.

P-values indicating significance at the .05 level are shown in bold.

Mediation analyses

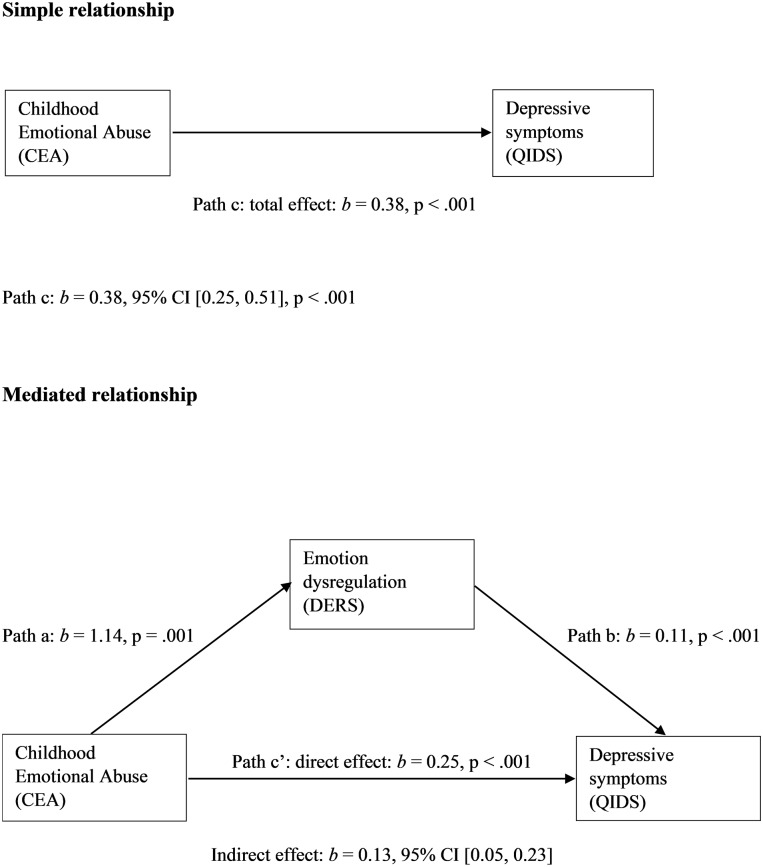

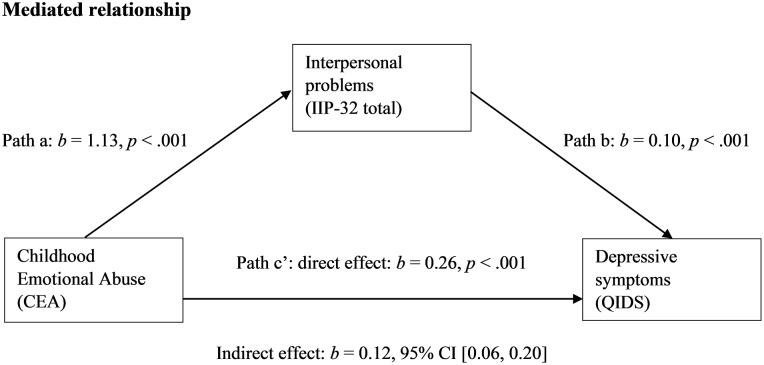

Emotion dysregulation significantly mediated the effect of CEA on depressive symptoms in a simple mediation model, as displayed in Fig 1. The indirect effect (b = 0.13) explained 34% of the total effect (b = 0.38). Additionally, interpersonal problems significantly mediated the effect of CEA on depressive symptoms in a separate simple mediation model, as displayed in Fig 2. The indirect effect (b = 0.12) explained 31% of the total effect (b = 0.38).

Fig 1. Model of childhood emotional abuse as predictor of depressive symptoms, mediated by emotion dysregulation.

Fig 2. Model of childhood emotional abuse as predictor of depressive symptoms, mediated by interpersonal problems.

Table 6 provides the results of the multiple mediation analysis for the eight domains of interpersonal problems. The effect of CEA on depressive symptoms was significantly mediated by the following domains of interpersonal problems: cold/distant (proportion mediated: 9%) and domineering/controlling (proportion mediated: 14%). Although the domain self-sacrificing was significantly associated with depressive symptoms, it was not significantly associated with CEA.

Table 6. Results of multiple mediation analysis for testing all eight domains of interpersonal problems as mediators of the effect of childhood emotional abuse on depressive symptoms in female college students (N = 276).

| Mediators (M) | b of CEA → M (path a) | b of M → QIDS (path b) | b of indirect effect (a x b) [95% CI] | PM: proportion of indirect effect of total effect [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vindictive/self-centered | 0.12** | -0.05 | -0.01 [-0.04, 0.02] | -0.02 [-0.12, 0.05] |

| Cold/distant | 0.15** | 0.23* | 0.03a [0.01, 0.08] | 0.09 [0.01, 0.23] |

| Socially inhibited | 0.19*** | 0.10 | 0.02 [-0.02–0.08] | 0.05 [-0.05, 0.21] |

| Nonassertive | 0.12* | 0.12 | 0.01 [-0.01, 0.07] | 0.04 [-0.02, 0.17] |

| Overly accommodating | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.01 [-0.02, 0.05] | 0.02 [-0.05, 0.14] |

| Self-sacrificing | 0.11 | 0.19* | 0.02 [-0.00, 0.07] | 0.05 [-0.00, 0.18] |

| Intrusive/needy | 0.15** | -0.09 | -0.01 [-0.05, 0.01] | -0.04 [-0.15, 0.02] |

| Domineering/controlling | 0.18*** | 0.28** | 0.05a [0.01, 0.12] | 0.14 [0.03, 0.33] |

a = significant at the .05 level: 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval did not contain zero.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to examine whether CEA, CPA, and CSA are independently associated with depressive symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and interpersonal problems in female college students. As hypothesized, CEA was independently associated with depressive symptoms and emotion dysregulation, whereas CPA and CSA were not. These results are consistent with previous studies that found CEA to be more strongly related to depression than CSA and CPA [10, 16–19, 26]. In addition, these findings are in line with research demonstrating that CEA significantly predicted emotion dysregulation above and beyond the effects of CSA and CPA in female college students [34] and inpatients with substance use disorders [60]. An explanation for this consistently reported result may be found in children’s development of emotion regulation skills, which is highly influenced by the family emotional climate and interactions with primary caregivers [61, 62]. A child’s emotion regulation capabilities can be undermined by parents’ denigrating or dismissive behaviors and frequent negative emotions directed at the child [61, 63]. These patterns appear to be most exemplary for CEA, as opposed to CPA and CSA. Moreover, children are assumed to imitate their parents’ modes of emotion regulation. Poor emotion regulation modeling by primary caregivers in the form of CEA may lead to emotion regulation deficits in children [64].

Contrary to our expectations, only CEA was independently associated with interpersonal problems—although CPA was significantly associated with interpersonal problems at the univariate level. These findings are inconsistent with previous studies that demonstrated CSA to be associated with interpersonal problems [40, 41]. However, no previous study has examined multiple types of childhood abuse in one model, thereby examining the unique impact of each type, while adjusting for the other types. Our results suggest that only CEA contributes to interpersonal problems above and beyond the impact of CSA and CPA. CEA involves humiliating, demeaning behavior and verbal assaults on one’s sense of worth or well-being [51], which, together with the often more chronic character of CEA compared to CPA and CSA, are likely to influence one’s attitudes and behavior towards others.

Additionally, we aimed to examine whether the relationship between CEA and depressive symptoms is mediated by emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. As hypothesized, we found that both emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems mediated this relationship. With regard to emotion dysregulation, this finding is consistent with previous research in samples of female college students [31], low-income African-Americans [33], and depressed inpatients [32]. The current study adds to the literature by confirming the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the association between CEA and depressive symptoms in a European sample of female college students, and by using a widely-used measure of overall emotion dysregulation with good psychometric properties.

With regard to interpersonal problems, our study is the first to identify interpersonal problems as a mediator of the association between CEA and depressive symptoms. This study extends previous research that associated CEA with interpersonal problems [41]. Possibly, individuals who report a higher level of interpersonal problems experience less social support. It has consistently been shown that social support and larger, diverse social networks are protective against depression in the general population [46, 65], especially in women [48]. Importantly, perceived social support, rather than received social support plays an important protective role against depression in the general population (see [46], for a review). Correspondingly, in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders, perceived social disability, rather than loneliness or a low level of social activities, predicted persistence of these disorders at 2-year follow-up [66].

Our final aim was to explore whether specific domains of interpersonal problems could be identified as particularly important in explaining the relationship between CEA and depressive symptoms. We found that this relationship was mediated by cold/distant and domineering/controlling interpersonal styles. Cold/distant individuals do not feel close to or loving toward others, and find it hard to make and maintain long-term commitments to other people [44]. Children suffering from emotional abuse by attachment figures may develop negative internal working models of the self and others that interfere with social functioning as the child matures, and can lead to interpersonal avoidance and a lack of trust in others [67, 68]–possibly reflecting a cold/distant interpersonal style. Avoidance of social situations and being cold/distant can in turn lead to depression [47, 69].

Domineering/controlling individuals describe themselves as too controlling or manipulative, and attempt to influence others by arguing excessively and sometimes showing hostile or aggressive behavior [44]. Our findings are in line with Huh, Kim, Yu and Chae [41], who reported that CEA is associated with being more domineering/controlling in a sample of adult outpatients with depression and anxiety disorders. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study reported an association between domineering/controlling behavior as measured with the IIP [44] and depressive symptoms. However, Barrett and Barber [47] compared interpersonal profiles of adults with major depressive disorder with the IIP-normative sample, and found no significant differences between these groups on the subscale domineering/controlling. Future prospective studies are needed to examine whether domineering/controlling behavior stems from CEA, and to what extent this type of interpersonal problems may cause a higher risk of depression.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has several strengths. This study is the first to explore the mediating role of interpersonal problems in the association between CEA and depressive symptoms. In addition, this study is the first to confirm previous research indicating emotion dysregulation to be a mediator in the association between CEA and depressive symptoms in a European sample of college students, using well-validated measures. Furthermore, we determined the unique and collective impact of three types of childhood abuse in multiple regression models, whereas the majority of previous studies only addressed a single type of childhood abuse.

This study also has some limitations. First, since this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot draw firm conclusions on causality − therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. Longitudinal research is needed to confirm that emotion dysregulation and interpersonal functioning prospectively mediate the effect of CEA on depression and do indeed represent causal mechanisms. Second, the study relied exclusively on self-report measures; however, all measures have good psychometric properties and are widely-used. The DERS is based on a clinical-contextual model of emotion regulation [38], which has been embraced within applied clinical research, but differs from the more narrow conceptualization of emotion regulation in studies in the field of affective science (e.g., [70]), which focus on the process of regulating emotions without including broader trait-like abilities such as clarity and self-control. With regard to the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, both the full scale and subscales were demonstrated to remain stable after 6 months of treatment despite significantly reduced psychopathology [71]. Third, the prevalence of CPA (N = 22, 8.0%) and CSA (N = 34, 13.0%) was relatively low, which may limit the statistical power to detect possible weak associations between these types of abuse and the outcome variables. Fourth, the generalizability of our results may be limited, since our sample consisted of well-educated, young adult women. However, the association between childhood maltreatment and adult depression did not differ between men and women in a large sample of patients [72]. Lastly, as the majority of our non-clinical sample reported none to mild depressive symptoms, results are not generalizable to depressed patients. However, well-educated, young adult women are an important high-risk group for developing a depression [50, 73]. A recent survey of the WHO World Mental Health International College Student project among 8 countries demonstrated depressive disorder to be the most common mental disorder in first-year college students, with a 12-month prevalence of 18.5% [74]. Importantly, female college students were at increased risk for both lifetime and 12-month mental disorders compared to male students [74].

Recommendations

Our findings indicate that both emotion dysregulation and specific types of interpersonal problems play an important role in the relationship between CEA and depression in female college students. Future studies should examine the collective and unique impact of different types of childhood abuse on specific types of interpersonal problems in diverse samples, such as lower educated samples, different age groups, males, and clinical samples of patients with mental disorders. Furthermore, our findings should be replicated in prospective studies that are able to examine whether emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems temporally precede the emergence of depressive symptoms. In addition, future studies should further examine the relation between interpersonal problems and depression, and the potential role of social support in this relationship.

The current study indicates that detecting and preventing CEA deserves as much attention from Child Protective Services as CPA and CSA. If emotion dysregulation and specific types of interpersonal problems are replicated in future studies as crucial links between CEA and depressive symptoms, prevention programs that target these specific, underdeveloped skills in children and adults with a history of CEA may be beneficial in primary prevention of depression. Furthermore, clinicians should recognize and acknowledge the harmful impact of CEA in treatment of depressed individuals. Incorporating treatment techniques aimed at strengthening emotion regulation and interpersonal skills (e.g., [75, 76]) may enhance treatment outcome and reduce the risk of relapse in depressed patients with a history of CEA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all students for their participation in this study, and Willemijn van Ginneken for her contribution to the data collection. We also thank the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences for the opportunity to collaborate with Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, U.S.A.

Data Availability

Data are deposited publicly in Figshare and are accessible via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7636511.v3.

Funding Statement

MMdW and CC received a Van der Gaag Grant of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW, https://www.knaw.nl/en) for this study. This research was also funded by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, https://www.nwo.nl/en), within the program “Violence Against Psychiatric Patients” (grant number: 432-12-804, awarded to JJMD, and grant number: 432-13-811, awarded to ATFB). TLMM received funding from the O’Toole Family Professor endownment (http://www.otoolefoundation.org/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009; 373(9657):68–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010; 197(5):378–85. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, et al. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010; 122(1):66–74. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 1997; 27(5):1101–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001; 286(24):3089–96. 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: a community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996; 20(1):7–21. 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molnar BE, Berkman LF, Buka SL. Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychol Med. 2001; 31(6):965–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braithwaite EC, O'Connor RM, Degli-Esposti M, Luke N, Bowes L. Modifiable predictors of depression following childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2017; 7(7):e1162 10.1038/tp.2017.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999; 38(12):1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007; 64(1):49–56. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egeland B. Taking stock: childhood emotional maltreatment and developmental psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2009; 33(1):22–6. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002; 156(8):824–30. 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2007; 31(5):517–30. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein DN, Glenn CR, Kosty DB, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM. Predictors of first lifetime onset of major depressive disorder in young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013; 122(1):1–6. 10.1037/a0029567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: a systematic review of reviews. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009; 29(7):647–57. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martins CMS, Baes CVW, de Carvalho Tofoli SM, Juruena MF. Emotional abuse in childhood is a differential factor for the development of depression in adults. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2014; 202(11):774–82. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibb BE, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatients. Depress Anxiety. 2007; 24(4):256–63. 10.1002/da.20238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, Ehring T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017; 210(2):96–104. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012; 9(11):e1001349 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual: Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011; 16(2):79–101. 10.1177/1077559511403920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, IJzendoorn MH, Alink LR. Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology. 2013; 48(2):81–94. 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LR, van IJzendoorn MH. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: a meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2012; 21(8):870–90. 10.1080/10926771.2012.708014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu GR, Lutfey KE, Litman HJ, Link CL, Hall SA, McKinlay JB. Prevalence and overlap of childhood and adult physical, sexual, and emotional abuse: a descriptive analysis of results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Violence Vict. 2013; 28(3):381–402. 10.1891/0886-6708.11-043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Dev Psychopathol. 2007; 19(1):149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2003; 27(11):1247–58. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopfinger L, Berking M, Bockting CL, Ebert DD. Emotion regulation mediates the effect of childhood trauma on depression. J Affect Disord. 2016; 198:189–97. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005; 1:409–38. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994; 59(2–3):25–52. 10.2307/1166137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schierholz A, Krüger A, Barenbrügge J, Ehring T. What mediates the link between childhood maltreatment and depression? The role of emotion dysregulation, attachment, and attributional style. European journal of psychotraumatology. 2016; 7(1):32652 10.3402/ejpt.v7.32652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coates AA, Messman-Moore TL. A structural model of mechanisms predicting depressive symptoms in women following childhood psychological maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2014; 38(1):103–13. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz P, Beblo T, Ribbert H, Kater L, Spannhorst S, Driessen M, et al. How is childhood emotional abuse related to major depression in adulthood? The role of personality and emotion acceptance. Child Abuse Negl. 2017; 72:98–109. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crow T, Cross D, Powers A, Bradley B. Emotion dysregulation as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse and current depression in a low-income African-American sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2014; 38(10):1590–8. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns EE, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Child maltreatment, emotion regulation, and posttraumatic stress: The impact of emotional abuse. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2010; 19(8):801–19. 10.1080/10926771.2010.522947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berzenski SR. Distinct emotion regulation skills explain psychopathology and problems in social relationships following childhood emotional abuse and neglect. Dev Psychopathol. 2018:1–14. 10.1017/S0954579418000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beblo T, Scheulen C, Fernando SC, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, Rodewald K, et al. Psychometrische Analyse eines neuen Fragebogens zur Erfassung der Akzeptanz von unangenehmen und angenehmen Gefühlen (FrAGe). Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2011:133–44. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powers A, Stevens J, Fani N, Bradley B. Construct validity of a short, self report instrument assessing emotional dysregulation. Psychiatry Res. 2015; 225(1–2):85–92. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004; 26(1). 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu RT. Childhood Adversities and Depression in Adulthood: Current Findings and Future Directions. Clin Psychol (New York). 2017; 24(2):140–53. 10.1111/cpsp.12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiffen VE, Thompson JM, Aube JA. Mediators of the link between childhood sexual abuse and adult depressive symptoms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000; 15(10):1100–20. 10.1177/088626000015010006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huh HJ, Kim SY, Yu JJ, Chae JH. Childhood trauma and adult interpersonal relationship problems in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2014; 13(1):26 10.1186/s12991-014-0026-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sperry DM, Widom CS. Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. 2013; 37(6):415–25. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colman RA, Widom CS. Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: a prospective study. Child Abuse Negl. 2004; 28(11):1133–51. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horowitz LM, Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Inventory of interpersonal problems. London: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horowitz LM. Interpersonal foundations of psychopathology: Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Mason C, Haro JM. The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015; 175:53–65. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrett MS, Barber JP. Interpersonal profiles in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2007; 63(3):247–66. 10.1002/jclp.20346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: a longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162(2):250–6. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagborg JM, Tidefors I, Fahlke C. Gender differences in the association between emotional maltreatment with mental, emotional, and behavioral problems in Swedish adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017; 67:249–59. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Graaf R, ten Have M, van Gool C, van Dorsselaer S. Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47(2):203–13. 10.1007/s00127-010-0334-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003; 27(2):169–90. 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thombs BD, Bernstein DP, Lobbestael J, Arntz A. A validation study of the Dutch Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: factor structure, reliability, and known-groups validity. Child Abuse Negl. 2009; 33(8):518–23. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Hickendorff M, van Hemert AM, Bernstein DP, Elzinga BM. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychol Assess. 2014; 26(3):717–29. 10.1037/pas0000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003; 54(5):573–83. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reilly TJ, MacGillivray SA, Reid IC, Cameron IM. Psychometric properties of the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015; 60:132–40. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neumann A, van Lier PA, Gratz KL, Koot HM. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Assessment. 2010; 17(1):138–49. 10.1177/1073191109349579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rijnhart JJM, Twisk JWR, Chinapaw MJM, de Boer MR, Heymans MW. Comparison of methods for the analysis of relatively simple mediation models. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017; 7:130–5. 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banducci AN, Hoffman EM, Lejuez CW, Koenen KC. The impact of childhood abuse on inpatient substance users: specific links with risky sex, aggression, and emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014; 38(5):928–38. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson RA. Socialization of Emotion and Emotion Regulation in the Family In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2014. p. 173–86. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Soc Dev. 2007; 16(2):361–88. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eisenberg N, Morris AS. Children's emotion-related regulation. Adv Child Dev Behav. 2002; 30:189–229. 10.1016/S0065-2407(02)80042-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bariola E, Gullone E, Hughes EK. Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011; 14(2):198 10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gariepy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallee A. Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016; 209(4):284–93. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saris I, Aghajani M, van der Werff S, van der Wee N, Penninx B. Social functioning in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017; 136(4):352–61. 10.1111/acps.12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2 New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Riggs SA. Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: What theory and research tell us. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2010; 19(1):5–51. 10.1080/10926770903475968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manes S, Nodop S, Altmann U, Gawlytta R, Dinger U, Dymel W, et al. Social anxiety as a potential mediator of the association between attachment and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016; 205:264–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gross JJ. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998; 2(3):271–99. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paivio SC. Stability of retrospective self-reports of child abuse and neglect before and after therapy for child abuse issues. Child Abuse Negl. 2001; 25(8):1053–68. 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00256-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arnow BA, Blasey CM, Hunkeler EM, Lee J, Hayward C. Does gender moderate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and adult depression? Child maltreatment. 2011; 16(3):175–83. 10.1177/1077559511412067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, Tuithof M, ten Have M. Sociodemographic and psychiatric predictors of attrition in a prospective psychiatric epidemiological study among the general population. Result of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Compr Psychiatry. 2013; 54(8):1131–9. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018; 127(7):623–38. 10.1037/abn0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berking M. Training emotionaler Kompetenzen: TEK-Schritt für Schritt.: Springer-Verlag; 2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christ C, de Waal MM, van Schaik DJF, Kikkert MJ, Blankers M, Bockting CLH, et al. Prevention of violent revictimization in depressed patients with an add-on internet-based emotion regulation training (iERT): study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2018; 18(1):29 10.1186/s12888-018-1612-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are deposited publicly in Figshare and are accessible via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7636511.v3.