Abstract

Aim

Excessive use of online games can have negative influences on mental health and daily functioning. Although the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have been investigated for the treatment of addiction, it has not been evaluated for excessive online game use. This study aimed to investigate the feasibility and tolerability of tDCS over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in online gamers.

Methods

A total of 15 online gamers received 12 active tDCS sessions over the DLPFC (anodal left/cathodal right, 2 mA for 30 min, 3 times per week for 4 weeks). Before and after tDCS sessions, all participants underwent 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans and completed the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), Brief Self Control Scale (BSCS), and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

Results

After tDCS sessions, weekly hours spent on games (p = .02) and scores of IAT (p < .001) and BDI-II (p = .01) were decreased, whereas BSCS score was increased (p = .01). Increases in self-control were associated with decreases in both addiction severity (p = .002) and time spent on games (p = .02). Moreover, abnormal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of regional cerebral glucose metabolism in the DLPFC was partially alleviated (p = .04).

Conclusions

Our preliminary results suggest that tDCS may be useful for reducing online game use by improving interhemispheric balance of glucose metabolism in the DLPFC and enhancing self-control. Larger sham-controlled studies with longer follow-up period are warranted to validate the efficacy of tDCS in gamers.

Keywords: online game, transcranial direct current stimulation, positron emission tomography, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose, self-control

Introduction

Increasing attention has been paid to the excessive use of online games since accumulating evidence has suggested that it can have negative influences on mental health and daily functioning and may lead to Internet gaming disorder (IGD; Chen & Peng, 2008; Ho et al., 2014; Pawlikowski & Brand, 2011).

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique in which a low-intensity direct current is applied on scalp resulting in modulation of neuronal resting membrane potentials. In general, anodal tDCS enhances cortical excitability and cathodal tDCS reduces it (Nitsche & Paulus, 2000). Compared to other non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), tDCS devices are simpler and cheaper. Moreover, tDCS is associated with only mild and transient adverse effects such as itching and tingling under the electrodes (Poreisz, Boros, Antal, & Paulus, 2007).

Several studies have reported that tDCS on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) can be effective for treating behavioral and substance addiction (Boggio et al., 2008, 2010; Fregni et al., 2008; Goldman et al., 2011; Sauvaget et al., 2015). However, it has not been tested in online game use.

The current pilot study is a prospective single-arm study evaluating the feasibility and tolerability of tDCS over the DLPFC in reducing online game use. First, changes in symptoms of online game addiction, time spent on games, self-control, and depressive symptoms were examined after tDCS sessions. Second, we used 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) to evaluate changes in regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (rCMRglu) in the DLPFC. We focused on the asymmetry of rCMRglu in the DLPFC, since asymmetry of brain function may be involved in the pathophysiology of IGD (Gordon, 2016) and tDCS changes cortical excitability in a polarity-dependent manner (Nitsche & Paulus, 2000).

Methods

Participants

Young adults who play online games were recruited as the gamer group, whereas those who do not play games were included as the non-gamer group. The inclusion criteria for the gamer group were those who have two or more IGD symptoms as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or play games at least 1 hr per day on average. Exclusion criteria for both groups were (a) current major medical conditions including psychiatric or neurological disorders; (b) taking psychotropic medications; (c) history of traumatic brain injury; (d) history of seizure, epilepsy, or brain surgery; and (e) history of alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence. All tDCS sessions and clinical and neuroimaging evaluations were conducted at Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital (Incheon, South Korea).

Transcranial direct current stimulation

After the baseline visit, the gamers received 12 active sessions (three times per week for 4 weeks) using the tDCS device (Ybrain, Seongnam, South Korea). The current was given at 2 mA for 30 min. The anodal electrode was placed over the left DLPFC (F3; 10–20 EEG system) and the cathode electrode over the right DLPFC (F4). The participants were asked to report any adverse effects after each session.

Clinical assessment

The severity of online game addiction was evaluated using the modified version of the Young’s Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998), in which the word “Internet” has been replaced with “online games.” The Brief Self Control Scale (BSCS) was used to assess levels of self-control (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). Depressive symptoms were examined using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The gamer group also reported weekly hours spent playing games. The baseline and follow-up assessments were performed within 1 week before the first tDCS session and after the last session, respectively.

Brain image acquisition and processing

Brain FDG-PET scans were conducted using a Discovery PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) at baseline and follow-up visits. All participants were intravenously injected with 185–222 MBq of FDG. Forty-seven transaxial emission images were acquired after 45 min of uptake period (pixel size = 1.95 × 1.95 mm, slice thickness = 3.27 mm). Sixteen slices of CT images were also obtained for attenuation correction. Standard filtering and reconstructing techniques were applied for the PET images.

Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK) was used for image processing. All PET images were spatially normalized to the SPM PET template (Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada) and resliced with a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. Voxel intensities were normalized to global mean intensity by proportional scaling. Normalized rCMRglu values were extracted from the bilateral DLPFC and primary motor cortex. Asymmetry index (AI) of rCMRglu was defined as (right − left)/[(right + left)/2] × 100. Positive AI indicates right-greater-than-left glucose metabolism.

Statistical analysis

Baseline differences in age, sex, and AI between two groups were examined using independent t-test or χ2 test. Changes in weekly hours spent playing games, scores of the IAT, BSCS, and BDI-II, and AI were assessed using linear mixed model in the gamer group. For significant changes of AI, we further assessed the changes of rCMRglu of the left and right regions-of-interest using linear mixed model.

Two separate multiple linear analyses were conducted with changes in IAT score or changes in time spent on games as a dependent variable and changes in scores of BSCS and BDI-II as independent variables.

A two-tailed p < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were conducted with Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the institutional review board of Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital (Incheon, South Korea). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Fifteen young adults were included in the gamer group and 10 young adults in the non-gamer group. The mean ages of the gamer and non-gamer groups were 21.3 ± 1.4 and 28.8 ± 7.5 years, respectively (t = −3.81, p < .001). There were eight men in the gamer group and six men in the non-gamer group (χ2 = 0.11, p = .74). In the gamer group, seven participants were diagnosed with IGD.

After the tDCS sessions, IAT score (z = −4.29, p < .001), weekly hours spent playing games (z = −2.41, p = .02), and BDI-II score (z = −2.75, p = .01) were decreased (Table 1). The score of BSCS was significantly increased (z = 2.80, p = .01). No participants reported any adverse effects of tDCS.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of gamers

| Characteristics | Pre-tDCS (mean ± SD or n) | Post-tDCS (mean ± SD) | Test statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.3 ± 1.4 | ||

| Sex (male/female) | 8/7 | ||

| Internet gaming disorder | 7 | ||

| Internet Addiction Test | 37.5 ± 15.7 | 24.9 ± 16.7 | z = −4.29, p < .001 |

| Weekly hours spent playing games | 16.8 ± 11.7 | 10.3 ± 9.9 | z = −2.41, p = .02 |

| Brief Self Control Scale | 35.1 ± 6.4 | 37.9 ± 4.7 | z = 2.80, p = .01 |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 13.7 ± 9.6 | 9.7 ± 8.1 | z = −2.75, p = .01 |

Note. SD: standard deviation; tDCS: transcranial direct current stimulation.

The decrease in IAT score was associated with the improvement in BSCS score (β = −0.81, p = .002), but not with the BDI-II score (β = −0.10, p = .66). In addition, the decrease in time spent on games was correlated with the increase in BSCS score (β = −0.70, p = .02), but not with the BDI-II score (β = −0.40, p = .15).

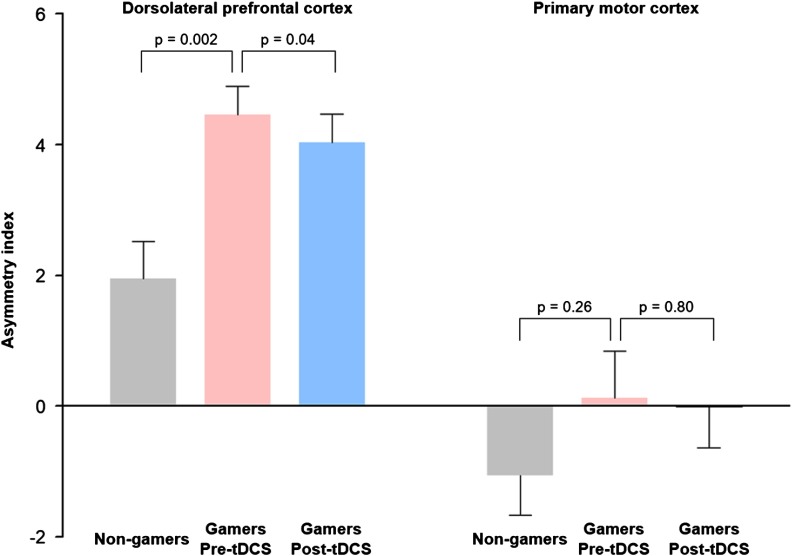

Before the tDCS sessions, AI of the DLPFC was 4.5 ± 1.7 in the gamer group and 1.9 ± 1.8 in the non-gamer group, indicating a significant difference (t = 3.53, p = .002; Figure 1). However, AI of the primary motor cortex in the gamer group (0.1 ± 2.8) was comparable to that in the non-gamer group (−1.1 ± 1.9, t = 1.16, p = .26). After the tDCS sessions, AI of the DLPFC was significantly decreased in the gamer group (4.0 ± 1.7, z = −2.11, p = .04), whereas AI of the primary motor cortex did not change (−0.01 ± 2.4, z = −0.25, p = .80). rCMRglu of the left DLPFC did not significantly change (z = −1.58, p = .11), whereas that of the right DLPFC was decreased at a marginal significance level (z = −1.89, p = .06).

Figure 1.

Asymmetry index (AI) of regional cerebral glucose metabolism in gamers before and after prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and non-gamers at baseline. AI was defined as [(right − left)/(right + left)/2 × 100]. Error bars denote standard errors

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the feasibility and tolerability of tDCS in online gamers. Following 12 active tDCS sessions over the DLPFC, symptoms of online game addiction, average time spent on games, and subclinical depressive symptoms were significantly decreased, whereas self-control was increased without any adverse events. Moreover, increases in self-control were linearly associated with decreases in both addiction symptoms and time spent on games. In PET analysis, abnormal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of rCMRglu in the DLPFC was partially alleviated after the tDCS sessions in the gamer group.

Improvements in subclinical depressive symptoms and self-control after tDCS of the DLPFC are in line with previous studies. Anodal tDCS of the left DLPFC ameliorated depressive symptoms in patients with major depression (Fregni et al., 2006) and enhanced performance on the Stroop task in healthy adults (Loftus, Yalcin, Baughman, Vanman, & Hagger, 2015). However, decreases in both addiction symptoms and time spent on games were correlated only with the increase in self-control, not with the reduction in depressive symptoms. Although these results suggest that the improvement in self-control may be more closely related to the control of online game use, further studies are needed to elucidate detailed mechanism of prefrontal tDCS in gamers.

Several studies investigating the neural correlates of IGD have reported structural and functional impairments in the prefrontal regions including the DLPFC (Park, Han, & Roh, 2017). The DLPFC has been suggested to be closely involved in the pathophysiology of both substance and behavioral addiction: craving (Kober et al., 2010), impulse control (Li, Luo, Yan, Bergquist, & Sinha, 2009), and decision-making (Fecteau, Fregni, Boggio, Camprodon, & Pascual-Leone, 2010). A previous study using functional magnetic resonance imaging found altered cue-induced activity in the DLPFC of individuals with IGD (Ko et al., 2009). Reduced gray matter density of the DLPFC was also shown in IGD subjects (Choi et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2011). However, laterality of brain activity remains unclear in online game addiction, although a previous meta-analysis suggested that cue-induced craving for online gaming may be related to right prefrontal activations (Gordon, 2016). In this study, the right-lateralized rCMRglu of the DLPFC in the gamer group at baseline suggests that abnormal brain glucose metabolism may exist at resting state. Furthermore, tDCS partially alleviated this asymmetry in the gamers by decreasing rCMRglu of the right DLPFC.

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, a lack of a sham-control group does not allow one to distinguish actual physiological effects from placebo effects. However, significant changes in brain glucose metabolism may indicate actual effects of tDCS and uncontrolled design has been used in several preliminary studies using TMS or tDCS among patients with addiction or other psychiatric disorders (Kekic, Boysen, Campbell, & Schmidt, 2016; Politi, Fauci, Santoro, & Smeraldi, 2008). Future studies may apply tDCS to both gamers and non-gamers and compare the effects between the two groups. Another strategy would be splitting gamers into active or sham tDCS group. The most robust design would be the combination of both approaches in order to prove the specificity and causal effects of tDCS. Second, the sample size was small, and for this reason we did not conduct additional analysis comparing efficacy of tDCS between IGD patients and normal gamers within the gamer group. Further research is required to determine whether tDCS is more effective on normal gamers or patients with IGD. Third, the non-gamer group showed significantly higher age than the gamer group. However, since all participants were young adults, aging effect may not be influential on brain glucose metabolism. Fourth, weekly hours spent on games were self-reported rather than measured values. Fifth, long-term follow-up assessments are required for future clinical applications.

Notwithstanding aforementioned limitations, this study demonstrated the possibility that tDCS of the DLPFC may reduce symptoms of online game addiction, time spent on games, and increase self-control. As a potential mechanism underlying these effects, tDCS may have partially restored interhemispheric balance of glucose metabolism in the DLPFC. Prefrontal tDCS may be a useful treatment option for online game overuse or IGD. Larger sham-controlled studies with longer follow-up period are warranted to validate the efficacy of tDCS in gamers.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This study was supported by the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2015M3C7A1064832).

Authors’ contribution

HJ, I-US, and Y-AC designed the study. SHL, HJ, JJI, JKO, EKC, I-US, and Y-AC conducted the study. HJ and JJI analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Brown G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory: Second edition manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Boggio P. S., Sultani N., Fecteau S., Merabet L., Mecca T., Pascual-Leone A., Basaglia A., Fregni F. (2008). Prefrontal cortex modulation using transcranial DC stimulation reduces alcohol craving: A double-blind, sham-controlled study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1–3), 55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggio P. S., Zaghi S., Villani A. B., Fecteau S., Pascual-Leone A., Fregni F. (2010). Modulation of risk-taking in marijuana users by transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 112(3), 220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. F., Peng S. S. (2008). University students’ Internet use and its relationships with academic performance, interpersonal relationships, psychosocial adjustment, and self-evaluation. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(4), 467–469. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Cho H., Kim J. Y., Jung D. J., Ahn K. J., Kang H. B., Choi J.-S., Chun J.-W., Kim D. J. (2017). Structural alterations in the prefrontal cortex mediate the relationship between Internet gaming disorder and depressed mood. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1245. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01275-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S., Fregni F., Boggio P. S., Camprodon J. A., Pascual-Leone A. (2010). Neuromodulation of decision-making in the addictive brain. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(11), 1766–1786. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F., Boggio P. S., Nitsche M. A., Marcolin M. A., Rigonatti S. P., Pascual-Leone A. (2006). Treatment of major depression with transcranial direct current stimulation. Bipolar Disorders, 8(2), 203–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00291.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F., Liguori P., Fecteau S., Nitsche M. A., Pascual-Leone A., Boggio P. S. (2008). Cortical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex with transcranial direct current stimulation reduces cue-provoked smoking craving: A randomized, sham-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(1), 32–40. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R. L., Borckardt J. J., Frohman H. A., O’Neil P. M., Madan A., Campbell L. K., Budak A., George M. S. (2011). Prefrontal cortex transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) temporarily reduces food cravings and increases the self-reported ability to resist food in adults with frequent food craving. Appetite, 56(3), 741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon H. W. (2016). Laterality of brain activation for risk factors of addiction. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 9(1), 1–18. doi: 10.2174/1874473709666151217121309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R. C., Zhang M. W., Tsang T. Y., Toh A. H., Pan F., Lu Y., Cheng C., Yip P. S., Lam L. T., Lai C. M., Watanabe H., Mak K. K. (2014). The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekic M., Boysen E., Campbell I. C., Schmidt U. (2016). A systematic review of the clinical efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 74, 70–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko C. H., Liu G. C., Hsiao S., Yen J. Y., Yang M. J., Lin W. C., Yen C. F., Chen C. S. (2009). Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(7), 739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kober H., Mende-Siedlecki P., Kross E. F., Weber J., Mischel W., Hart C. L., Ochsner K. N. (2010). Prefrontal-striatal pathway underlies cognitive regulation of craving. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(33), 14811–14816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007779107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. S., Luo X., Yan P., Bergquist K., Sinha R. (2009). Altered impulse control in alcohol dependence: Neural measures of stop signal performance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(4), 740–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00891.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus A. M., Yalcin O., Baughman F. D., Vanman E. J., Hagger M. S. (2015). The impact of transcranial direct current stimulation on inhibitory control in young adults. Brain and Behavior, 5(5), e00332. doi: 10.1002/brb3.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche M. A., Paulus W. (2000). Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. Journal of Physiology, 527(33), 633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B., Han D. H., Roh S. (2017). Neurobiological findings related to Internet use disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(7), 467–478. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowski M., Brand M. (2011). Excessive Internet gaming and decision making: Do excessive World of Warcraft players have problems in decision making under risky conditions? Psychiatry Research, 188(3), 428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi E., Fauci E., Santoro A., Smeraldi E. (2008). Daily sessions of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the left prefrontal cortex gradually reduce cocaine craving. American Journal on Addictions, 17(4), 345–346. doi: 10.1080/10550490802139283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreisz C., Boros K., Antal A., Paulus W. (2007). Safety aspects of transcranial direct current stimulation concerning healthy subjects and patients. Brain Research Bulletin, 72(4–6), 208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvaget A., Trojak B., Bulteau S., Jimenez-Murcia S., Fernandez-Aranda F., Wolz I., Menchón J. M., Achab S., Vanelle J. M., Grall-Bronnec M. (2015). Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in behavioral and food addiction: A systematic review of efficacy, technical, and methodological issues. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 9, 349. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J. P., Baumeister R. F., Boone A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237–244. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K., Qin W., Wang G., Zeng F., Zhao L., Yang X., Liu P., Liu J., Sun J., von Deneen K. M., Gong Q., Liu Y., Tian J. (2011). Microstructure abnormalities in adolescents with Internet addiction disorder. PLoS One, 6(6), e20708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]