Abstract

Background:

An engorgement and prolapse of the anal cushion lead to haemorrhoidal disease. There are different anatomical sites and presentation of this common pathology which affects the quality of life.

Aims:

To study the predilection sites, presentation and treatment of haemorrhoidal disease.

Patients and Method:

A cohort study of patients diagnosed with haemorrhoids at an Endoscopy centre in Port Harcourt, Rivers State Nigeria from February 2014- July 2017.The patients were divided into 2 groups: A - asymptomatic and B- symptomatic. Variables studied included: demographics, anatomic variations, grade of haemorrhoids, clinical presentation and treatment. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. Armonk, NY.

Results:

One hundred and twenty- one cases were included in study. There were 76 males and 45 males with age range from 15 -80 years (mean 51.9±13.1yrs). Bleeding per rectum was the most common presentation. The position frequency of haemorrhoids in decreasing order were: right posterior (34.1%); right anterior (28.2%); left lateral (17.1%); left posterior (7.6%). Multiple quadrants were affected in 58(72.5%) cases of external haemorrhoids. Grade I, II and III haemorrhoids were seen in 38 (31%), 31(26%) and 21(17%) cases respectively.

Conclusion:

The most common anatomical site of external haemorrhoids is the right posterior quadrant position; frequently, multiple sites are simultaneously affected. Goligher classification Grade 1 hemorrhoids are effectively treated by injection sclerotherapy using 50% dextrose solution; a cheap and physiologic sclerotherapy agent.

Keywords: Hemorrhoids, presentation pattern, quadrant, Hémorroïdes, présentation, traitement

Résumé

Contexte:

Un engorgement et un prolapsus du coussin anal entraînent une maladie hémorroïdaire. Il existe différents sites anatomiques et présentation de cette pathologie commune qui affecte la qualité de la vie.

Objectifs:

Étudier les sites de prédilection, la présentation et le traitement de la maladie hémorroïdaire.

Patients et méthode:

Étude de cohorte de patients chez lesquels des hémorroïdes ont été diagnostiquées dans un centre d'endoscopie à Port Harcourt, dans l'État de Rivers, au Nigéria, de février 2014 à juillet 2017. Les patients ont été divisés en 2 groupes: A - asymptomatique et B - symptomatique. Les variables étudiées comprenaient: la démographie, les variations anatomiques, le grade des hémorroïdes, la présentation clinique et le traitement. L'analyse statistique a été réalisée à l'aide de IBM SPSS Statistics pour Windows, version 20.0. Armonk, NY.

Résultats:

Cent vingt et un cas ont été inclus dans l'étude. Il y avait 76 hommes et 45 hommes âgés de 15 à 80 ans (moyenne de 51,9 ± 13,1 ans). Les saignements per rectum étaient la présentation la plus courante. La fréquence de positionnement des hémorroïdes par ordre décroissant était la suivante: droite postérieure (34,1%); antérieur droit (28,2%); latéral gauche (17,1%); postérieur gauche (7,6%). Des quadrants multiples ont été touchés dans 58 (72,5%) cas d'hémorroïdes externes. Des hémorroïdes de grade I, II et III ont été observées dans 38 (31%), 31 (26%) et 21 (17%) cas, respectivement.

Conclusion:

Le site anatomique le plus commun des hémorroïdes externes est la position du quadrant postérieur droit; fréquemment, plusieurs sites sont affectés simultanément. Classification de Goligher Les hémorroïdes de grade 1 sont efficacement traitées par sclérothérapie par injection en utilisant une solution de dextrose à 50%; un agent de sclérothérapie bon marché et physiologique.

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoids are a leading cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding with a high impact on quality of life.[1,2] The pathophysiology is multifactorial including: sliding anal cushion; hyperperfusion of hemorrhoid plexus; vascular abnormality; tissue inflammation; and internal rectal prolapse (rectal redundancy).[3,4,5] The predisposing conditions to increased incidence of symptomatic hemorrhoids include state of elevated intra-abdominal pressure such as pregnancy and straining. Others known to contribute are weakening of the supporting connective tissue, smooth muscle, and vasculature from advancing age and activities such as strenuous lifting, straining with defecation, and prolonged sitting.[6,7]

Hemorrhoids are classified as internal or external based on the location from the dentate line. External hemorrhoids are located below, develop from ectoderm embryonically and are supplied by somatic nerves thus producing pain. In contrast, internal hemorrhoids lie above the dentate line, develop from endoderm and innervated by visceral nerve fibers so do not cause pain. The Goligher system classifies hemorrhoids into four grades or degrees of prolapse; Grade 1 hemorrhoids do not prolapse outside the anal canal. In Grade 2, there is prolapse upon bearing down at defecation, but this retracts spontaneously; Grade 3 hemorrhoids prolapse on bearing down at defecation but require manual reduction. Finally, in Grade 4, there is a persistent non-reducible prolapsed hemorrhoid.[8]

A thorough history and physical examination are required to help identify any possible alternative diagnosis as a cause of rectal bleeding. A sigmoidoscopy is needed to rule out a rectal mass; full colonoscopy will exclude other colonic causes of rectal bleeding. The best treatment option for the various grades of this disease is debatable; however, a guiding principle is to do less invasive options first. Conservative measures include dietary modifications with increasing fiber intake, hydration and avoidance of straining. Symptomatic control using hot Sitz bath and topical treatments containing various local anesthetics, corticosteroids, or anti-inflammatory drugs are useful.

Surgical treatment options for hemorrhoids are grouped into nonexcision and excision methods. The nonexcision methods include rubber band ligation, injection sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, cryotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and laser therapy. The surgical excision operations are the Milligan-Morgan (open) or Ferguson (closed) technique. A variety of instruments, including ultrasonic scalpels, lasers, bipolar electrothermal devices, and circular staplers are currently used when performing excision surgeries. The newer nonexcision technique of Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL) with mucopexy was introduced to reduce the morbidity of surgery.[9]

This study aims to study the anatomy, pattern of presentation, and treatment outcome of hemorrhoidal disease from one surgeon's surgical gastroenterology service in a developing country.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a cohort study of consecutive patients with hemorrhoids diagnosed in an endoscopy center with surgical gastroenterology services in Port Harcourt Rivers State Nigeria. The center serves as an Endoscopy referral health facility in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. The study was conducted from February 2014 to September 2017. All patients presenting with bleeding per rectum and other symptoms of anal and colonic disease were evaluated. Inclusion criteria for the study were cases seen to have hemorrhoids following clinical evaluation or following sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Patients younger than 18 and referrals for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy with no internal or external hemorrhoids seen after the procedure were excluded. The data collated were demographics, anatomic variations, grade of hemorrhoids, clinical presentation, and treatment outcome.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA. Age was shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), mode and median; number and percentage of cases were used for nominal and ordinal data. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's Chi-square or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 171 cases were included in the study. There were 45 females and 76 males with age range from 15 to 80 years SD 51.9 ± 13.1 years. The median and modal age was 51 years. The patient distribution according to age groups and sex is as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of study population

| Age group (years) | Male (%) | Female (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| 21-30 | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 5 (4.0) |

| 31-40 | 12 (10.0) | 7 (6.0) | 19 (16.0) |

| 41-50 | 21 (17.0) | 11 (9.0) | 32 (26.0) |

| 51-60 | 24 (20.0) | 12 (10.0) | 36 (30.0) |

| 61-70 | 9 (7.0) | 5 (4.0) | 14 (11.0) |

| >70 | 8 (7.0) | 6 (5.0) | 14 (12.0) |

| Total | 76 (63.0) | 45 (37.0) | 121 (100) |

Bleeding per rectum was the most common presentation 86 (71%); however, one-fifth of the study population had no symptoms at presentation 25 (20.7%) and were diagnosed at endoscopy [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pattern of clinical presentation of hemorrhoid cases

| Symptoms | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Group A | |

| No symptom | 25 (20.7) |

| Group B | |

| Bleeding per rectum + anal protrusion | 86 (71.0) |

| Anal protrusion ± pain | 10 (8.3) |

| Total | 121 (100) |

Internal hemorrhoids were seen in 39 (31%) and external type in 82 (69%). There was no statistical difference in the mean age and sex distribution between the two groups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of internal versus external hemorrhoids in study

| Variable | Internal hemorrhoids (n=39) | External hemorrhoids (n=82) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 52.76±13.34 | 51.56±13.24 | 0.996 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 27 | 49 | 0.211 |

| Female | 12 | 33 |

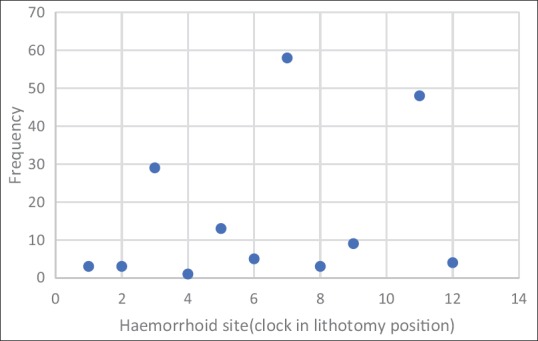

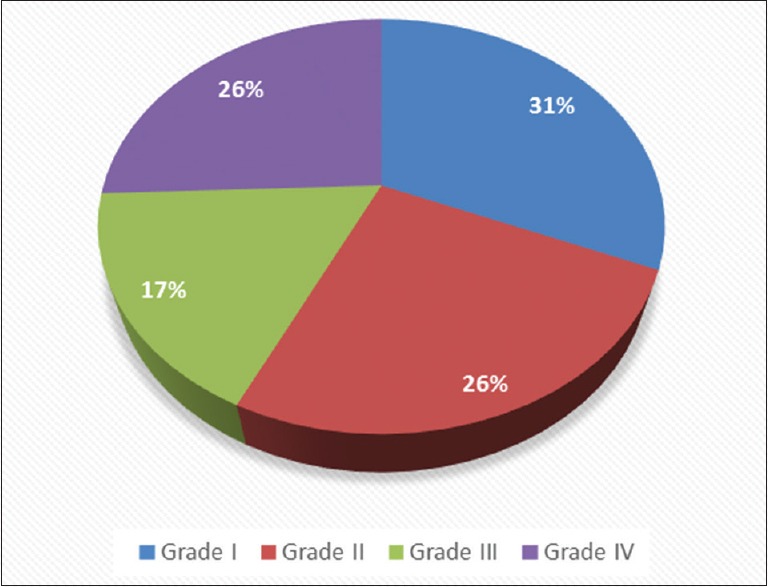

The distribution of external hemorrhoids using the clock dial positions is as shown in Figure 1. In a quadrantic distribution, hemorrhoids were as follows: one quadrant 24 (29.0%) cases; two quadrants 28 (34.0%) cases; three quadrants 26 (32.0%) cases; and four quadrants (circumferential) 4 (5%) cases. The position frequency of hemorrhoids in decreasing order was as follows: right posterior (34.1%); right anterior (28.2%); left lateral (17.1%); and left posterior (7.6%). Goligher classification Grades I, II, and III hemorrhoids were seen in 38 (38%), 31 (26%), and 21 (17%) cases, respectively [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Site distribution of hemorrhoids in study population

Figure 2.

Grades of hemorrhoids in study population

An offer of the treatment was acceded in 50 patients. Forty-six cases of Grade I-III hemorrhoids received injection sclerotherapy with 50% dextrose solution as sclerosant; band ligation in one Grade III hemorrhoid and 3 cases of excision surgeries for Grade IV hemorrhoid (3 Milligan Morgan/open and I Ferguson/closed hemorrhoidectomy). The symptoms were resolved in cases with excision surgery and the sole case of band ligation. There was no recurrence of symptoms following sclerotherapy in all the cases of Grade I hemorrhoid-16 (35.5%); however, there was rebleed in 8 (17%) cases following sclerotherapy with 50% dextrose solution requiring repeat sclerotherapy. Sclerotherapy was well tolerated with no case of local infection.

DISCUSSION

Hemorrhoids affect all age populations as seen in this study. Over half of the population affected was above the age of 50 years with male sex predominance. A literature search showed paucity of literature on epidemiology of hemorrhoids in Africa, but interventional studies from Nigeria reported a peak incidence in the late and early third and fourth decades respectively with a male predominance.[10,11] A national study in a Caucasian population recorded hemorrhoids most commonly between the ages of 45–65 years affecting 5% of the population with no sex dominance.[12] In general, it is estimated that 50% of the people older than 50 years have hemorrhoids symptoms at least for a period.[13] This lends credence to the weakening of supporting connective tissue associated with aging as a predisposing factor. This age group mostly affected is the same for anorectal cancer with similar clinical presentation but a worse outcome. There is the need for a thorough evaluation for alternative diagnosis in cases of bleeding per rectum.

The most common presentation of hemorrhoids seen was painless rectal bleeding during defecation with or without prolapsing anal tissue in 71% of cases [Table 3]. The blood is typically bright red because of direct arteriovenous communication in the hemorrhoid plexus. This may present as a coat on the stool at the end of defecation, stains on the toilet paper or in an alarming state spraying across the toilet bowl. One-fifth of the study population had no symptom at presentation for colonoscopy with the indications including screening, change in bowel habit and abdominal pains. It is our belief that this is an under representation, as patients are often embarrassed and reluctant to complain of anal symptoms in the clinic. Asymptomatic hemorrhoids have been reported to be seen in 40% of cases.[14] Less frequently, hemorrhoids are complicated as we recorded five cases (4%) of thrombosed external hemorrhoids associated with the painful protrusion at the anal verge.

Anatomically, hemorrhoidal cushions are clusters of vascular tissues, smooth muscles, and connective tissues that lie along the anal canal in three columns, namely left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior positions. These correspond to 3, 7, and 11 o’clock positions with the patient in lithotomy position. These are the area of anastomoses between the superior rectal artery and the superior, middle, and inferior rectal veins. Hemorrhoidal cushions play a significant physiologic role in augmenting closure of the anal canal in response to increased abdominal pressure by engorging with increased inferior vena cava pressure contributing 15%–20% of resting anal canal pressure.[15] From this study, more than one quadrant was affected in 58 (72.5%) cases of external hemorrhoids. The 7 o’ clock position was the most frequent site [Figure 1]. The anus forms an acute posteriorly directed angle with the axis of the rectum, approximately 90°at rest; with voluntary squeeze, it becomes more acute, around 70°, and during defecation, it becomes more obtuse, at 110°–130°.[16] The predilection for the 7 o’ clock position (right lower quadrant) is possibly due to more shearing action during defecation. Hydration and high fiber diet remained useful advice to patients with resulting regular soft stool and reduced straining at defecation.[17]

Over half of the population of patients had Grade 1 and 2 hemorrhoids [Figure 2] that were diagnosed with the aid of endoscopy. Although no underlying rectal lesion was documented at sigmoidoscopy, however, there were multiple pathologies seen in cases that had colonoscopy. This underscores the need for endoscopic evaluation of all cases of rectal bleeding. In this population, injection sclerotherapy with 50% dextrose water as sclerosant was effectively used. The efficacy of this readily available and physiologic sclerosant has been documented in areas where the preferred phenol in almond oil is not readily available.[11] Rubber band ligation was introduced into our service for Grades II and III hemorrhoids with the acquisition of a Karl Storz (Germany) hemorrhoid band ligator during the latter part of the study period with on-going data acquisition. This office-based procedure is a simple, safe, and effective method for treating symptomatic second- and third-degree hemorrhoids with significant improvement in quality of life.[10,18]

Hemorrhoidectomy is accepted as the gold standard for comparison of other surgical treatment of hemorrhoids.[19] This involves excision of hemorrhoidal pedicle to the apex region without damaging the internal sphincter. The post excision wound is either left open (Milligan Morgan) or closed (Ferguson). The Ferguson closed hemorrhoidectomy with electrosurgery device was used for a patient on life-long anticoagulant medication. The wound healed faster when seen at outpatient follow-up visit, more than in cases done by Milligan-Morgan open technique as documented in literature.[20] A balance is usually struck at operation between removing too much tissue with the risk of stenosis or removing too little and risking recurrence. This is especially true with circumferential Grade IV hemorrhoids [Figure 3]. A low recurrence rate is known to have a higher incidence of stenosis.[21] In acute thrombosed hemorrhoidal disease, evacuation of blood clot under local anesthesia with preferably a circumferential (deroofing) incision over the swelling to prevent the development of skin tag from a radial incision.[22]

Figure 3.

Four quadrant Grade IV hemorrhoid

The newer techniques of surgery include stapled hemorrhoidectomy which has a slightly higher recurrence rate but is performed as an outpatient procedure with quick return to normal activity.[23] An alternative treatment is HAL, performed preferably using a Doppler equipped proctoscopy to pinpoint branches of the hemorrhoidal artery that supply blood to hemorrhoids. These feeding vessels are sutured to inhibit further bleeding, while a second stitch firmly fixes the pile within the anal canal to prevent prolapse (mucopexy). There is conservation of the anatomy of the anal canal with no real wound after the procedure, risk of stenosis nor incontinence but quicker return to normal activity compared to open surgery. HAL requires an anesthetic, yet evidence suggests a recovery like rubber band ligation with more post procedure pain but an effectiveness that approaches the more intensive surgical option.[24] There is the need for further studies to compare this novel treatment approach to other treatment modalities in varying grades of hemorrhoids.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of hemorrhoids is highest in the middle-aged population mostly males. The most common anatomical site of external hemorrhoids is the right posterior quadrant position; frequently multiple sites are simultaneously affected. Bleeding per rectum is the leading presenting complaint. Goligher classification Grade 1 hemorrhoids are effectively treated by injection sclerotherapy using 50% dextrose solution; a cheap and physiologic sclerotherapy agent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Self-sponsored.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: From basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2009–17. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray-Offor E, Elenwo SN. Endoscopic evaluation of upper and lower gastro-intestinal bleeding. Niger J Surg. 2015;21:106–10. doi: 10.4103/1117-6806.162575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgado PJ, Suárez JA, Gómez LG, Morgado PJ., Jr Histoclinical basis for a new classification of hemorrhoidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:474–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02552621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung YC, Hou YC, Pan AC. Endoglin (CD105) expression in the development of haemorrhoids. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:107–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aigner F, Gruber H, Conrad F, Eder J, Wedel T, Zelger B, et al. Revised morphology and hemodynamics of the anorectal vascular plexus: Impact on the course of hemorrhoidal disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:105–13. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, Kim HE, Kang JH, Shin JY, Song YM. Factors associated with hemorrhoids in Korean adults: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J Fam Med. 2014;35:227–36. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2014.35.5.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loder PB, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK. Haemorrhoids: Pathology, pathophysiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1994;81:946–54. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goligher J, Duthie H, Nixon H. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. 5th ed. London: Balliere Tindall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morinaga K, Hasuda K, Ikeda T. A novel therapy for internal hemorrhoids: Ligation of the hemorrhoidal artery with a newly devised instrument (Moricorn) in conjunction with a Doppler flowmeter. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:610–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misauno MA, Usman BD, Nnadozie UU, Obiano SK. Experience with rubber band ligation of hemorrhoids in Northern Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2013;54:258–60. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.119654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akindiose C, Alatise OI, Arowolo OA, Agbakwuru AE. Evaluation of two injection sclerosants in the treatment of symptomatic haemorrhoids in Nigerians. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2016;23:110–5. doi: 10.4103/1117-1936.190347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dziki L, Mik M, Trzcinski R, Buczynski J, Kreisel A, Skoneczny M, et al. Surgical treatment of haemorrhoidal disease – The current situation in Poland. Prz Gastroenterol. 2016;11:111–4. doi: 10.5114/pg.2016.57616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poon GP, Chu KW, Lau WY, Lee JM, Yeung C, Fan ST, et al. Conventional vs. triple rubber band ligation for hemorrhoids. A prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:836–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02555358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, et al. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:215–20. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cintron J, Abacarian H. Benign anorectal: Hemorrhoids. In: Wolff B, Fleshman JW, editors. The ASCRS of Colon and Rectal Surgery. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 156–77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SS. Advances in diagnostic assessment of fecal incontinence and dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:910–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy CL, Chan CR, Cohen A. The surgical management of haemorrhoids – A review. Dig Surg. 2005;22:26–33. doi: 10.1159/000085343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aram FO. Rubber band ligation for hemorrhoids: An office experience. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:271–4. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulus H, Tas A, Coskun A, Kucukazman M. Evaluation of two hemorrhoidectomy techniques: Harmonic scalpel and Ferguson's with electrocautery. Asian J Surg. 2014;37:20–3. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaikh AR, Dalwani AG, Soomro N. An evaluation of milligan-morgan and Ferguson procedures for haemorrhoidectomy at Liaquat University hospital Jamshoro, Hyderabad, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:122–7. doi: 10.12669/pjms.291.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceulemans R, Creve U, Van Hee R, Martens C, Wuyts FL. Benefit of emergency haemorrhoidectomy: A comparison with results after elective operations. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:808–12. doi: 10.1080/110241500447452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy A, Cohen CR. The acute management of haemorrhoids. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:508–11. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184900967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayaraman S, Colquhoun PH, Malthaner RA. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD005393. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005393.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiernan J, Hind D, Watson A, Wailoo AJ, Bradburn M, Shephard N, et al. The HubBLe trial: Haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL) versus rubber band ligation (RBL) for haemorrhoids. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]