Abstract

Sundberg and Michael (2011) reviewed the contributions of Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior to the treatment of language delays in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and discussed several aspects of interventions, including mand training, intraverbal repertoire development, and the importance of using Skinner’s taxonomy of verbal behavior in the clinical context. In this article, we provide an update of Sundberg and Michael’s review and expand on some discussion topics. We conducted a systematic review of studies that focused on Skinner’s verbal operants in interventions for children with ASD that were published from 2001 to 2017 and discussed the findings in terms of journal source, frequency, and type of verbal operant studied.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Language intervention, Skinner, Systematic review, Verbal behavior, Verbal operants

Skinner developed and described a taxonomy of verbal operants in his book Verbal Behavior (1957). He defined verbal behavior as any response reinforced by the mediating behavior of another person. Skinner analyzed verbal behavior through the same optic used with nonverbal behavior: the functional relation between a response and its environmental variables. Skinner (1957) stated the need for “a unit of behavior composed of a response of identifiable form functionally related to one or more independent variables” (p. 20). In order to isolate the units of verbal behavior, Skinner described elementary verbal operants (e.g., mand, echoic, tact, intraverbal) and defined them by their functional components, including the stimuli that occasioned or evoked the response and the consequences that strengthened the response.

Even though Skinner considered Verbal Behavior (1957) to be his most important work (Sundberg, 1991), behavior analysts published a relatively small number of empirical studies on the subject in the decades immediately following its publication in comparison with empirical studies on nonverbal behavior (e.g., treatment of problem behavior). For example, a narrative review conducted by Oah and Dickinson (1989) reported a “limited number of studies” (p. 63) involving verbal operants. Furthermore, of the studies reported, the majority focused on mands and tacts. Oah and Dickinson suggested that one possible explanation for the limited number of research studies focused on verbal behavior might be the lack of appropriate and effective methods for data collection and variable manipulation. Similarly, Sundberg noted the lack of empirical research involving verbal behavior and suggested an agenda of experimental studies composed of 301 research topics raised from Verbal Behavior. The list was divided into 30 research areas, each containing 10 suggestions for specific empirical studies, plus an additional single area, education, presented as a research challenge for behavior analysts.

To update the state of literature since Oah and Dickinson (1989), Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) conducted a systematic review of empirical studies with humans that focused on Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. In their review, Sautter and LeBlanc reported publication trends in terms of the frequency, source of publication, and verbal operant of interest. The results demonstrated that the volume of empirical support for Skinner’s account of verbal behavior had almost tripled since Oah and Dickinson’s review. Although the results demonstrated the scientific community’s increasing interest in questions involving verbal behavior, Sautter and LeBlanc called for studies focusing on verbal operants other than mands and tacts as well as stronger empirical support for procedures related to interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Sundberg and Michael (2001) provided a review of the applications and benefits of Skinner’s account of verbal behavior, specifically in terms of interventions for children with ASD. The authors supported the effectiveness of the behavioral approach for language development over other interventions such as sensory integration, holding therapy, and psychoanalysis. Additionally, they discussed the contributions of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior as it pertains to language assessment, mand training during the early stages of intervention, the importance of motivating operations for mand acquisition, the relevance of intraverbal training for complex language development, and the role of automatic reinforcement during language training. Although the topics discussed by Sundberg and Michael reflect areas of importance during early stages of behavioral intervention programs, their review did not include a discussion of echoics or tacts. A review of the literature involving echoic and tact repertoires would be beneficial given that these two verbal operants often serve as prerequisites for advanced language skills (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011), and they are often used as controlling prompts when teaching more complex verbal operants (e.g., Finkel & Williams, 2001; Goldsmith, LeBlanc, & Sautter, 2007). Another important topic not addressed in Sundberg and Michael’s review pertains to the operant mechanisms and variables involved in generative language. Generative verbal behavior, as used herein, involves the emission of novel verbal behavior that exerts effective stimulus control over a listener’s behavior and responding effectively as a listener to another speaker’s verbal behavior (adapted from the definition of generative strategies provided by Alessi, 1987).

Sundberg and Michael (2001) discussed the need for intervention programs to address not only basic language repertoires but also complex language such as abstract concepts, yes–no questions, and subject–verb–object combination. Complex language is composed of verbal operants emitted under different forms of stimulus control (Michael, Palmer, & Sundberg, 2011); its acquisition fosters the development of cognitive, academic, and social skills in children with and without disabilities. However, it is unrealistic to assume that one could directly teach all components of language and advanced communication skills. As such, it is crucial that interventions for children with ASD identify the conditions that promote the emergence of novel, untrained responses (Alessi, 1987). A discussion involving generative language and emergent responses could contribute to the understanding of complex language development and guide practitioners during the design of behavioral intervention programs.

Although Sundberg and Michael (2001) recognized the increase in reports of the application of behavior–analytic procedures for improving interventions for children with ASD, particularly ones that addressed language and communication deficits, they also pointed out that most current programs failed to use the technical terms and principles described in Skinner’s Verbal Behavior (1957). In other words, many programs tended to use terms such as requests as opposed to mands and labels as opposed to tacts. Likewise, Michael (1984) raised a similar concern and stated that “the terms for elementary verbal relations – mand, tact, echoic, etc. – are used occasionally, but not to any important purpose; the research could have been conceived without the benefit of the distinctions Skinner makes” (p. 369). Sundberg and Michael suggested that by using these more traditional terms (e.g., requesting and labeling), one may underestimate the intricacies of verbal behavior relations and fail to perform an accurate analysis of child errors and response patterns.

In light of the assertions of Sundberg and Michael (2001), as well as those of Michael (1984), an updated review to assess the usage of Skinner’s (1957) verbal operants in the field of intervention for children with ASD seems warranted. More than 15 years have passed since Sundberg and Michael’s review. Our field has made considerable progress since then in researching and disseminating the benefits of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior to treatment for children with ASD. This progress is at least partially due to researchers employing Skinner’s taxonomy of verbal behavior more consistently in their research activities.

The purpose of the current article was twofold. First, we aimed to expand on the review by Sundberg and Michael (2001) in two ways: (a) by updating the literature on the topics discussed in their review and (b) by adding a discussion of interventions addressing echoics, tacts, and the emergence of verbal behavior. Second, we aimed to conduct a review of the literature from 2001 to 2017 of empirical studies in the area of verbal behavior in children with ASD by reporting on publication trends in terms of journal source, frequency, and type of verbal operant addressed.

Method

We used a two-step process to identify studies for inclusion in this research review. First, we completed electronic searches of the Academic Search Premiere, ERIC, and PsycINFO databases to locate studies in peer-reviewed journals between January 2001 and March 2017. We included studies beginning in 2001 because Sundberg and Michael published their seminal review in 2001. We used autism* as the key search term in combination with key dependent variable terms and roots (mand*, tact*, intraverbal*, echoic*, emergence*, generative, derived, and verbal behavior) to capture relevant studies. Because we restricted the search to participants diagnosed with ASD, the search always included a combination of the participant variable and the dependent variable. Second, we completed a manual search of the journals Behavioral Interventions (BI), Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA), Research in Developmental Disabilities (RDD), and The Analysis of Verbal Behavior (TAVB) for all volumes between 2001 and 2017. We manually searched these journals because they published the previous reviews on verbal behavior or because they represent the prominent journals in which behavior analysts publish research on the application of Skinner’s (1957) taxonomy of verbal behavior with children with ASD.

We reviewed studies that included children between birth and the age of 12 with a diagnosis of ASD. As long as one of the participants in a study met this criterion, we included the study. We only included studies that (a) used single-subject research designs in which the experimenters systematically manipulated one or more independent variables, (b) included one of the verbal operants from Skinner’s (1957) taxonomy as a dependent variable, and (c) involved the teaching of one or more new verbal responses (e.g., teaching new tacts to a child with ASD).

We coded studies for the following targeted areas: (a) the verbal operant(s) that served as the dependent variable(s)—we also coded for listener responding, although this was not part of the inclusion criteria, (b) emergence of other verbal operants, (c) generalization of the targeted verbal operant, and (d) the study’s purpose. We coded the studies using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet containing a coding checklist. We analyzed interrater reliability (IRR) on Areas a, b, and c for exactly 33% of the studies. For Areas a and c, we recorded an agreement if both coders marked an X or if both coders did not mark an X for the same item (e.g., both coders marked an X for mand or both coders did not mark an X for mand). For Area b, we recorded an agreement if both coders listed the same operant(s) under “training of” and “emergence of” or if both coders did not list any operant (e.g., both coders listed tact under “training of” and mand under “emergence of”). For each study, coders either agreed or disagreed on eight coding variables. Two of the authors and a research assistant independently coded the study, and one of the authors then compared the code sheets to identify discrepancies. We calculated the IRR by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and converting the resulting quotient to a percentage, which produced an agreement coefficient of 96%.

Findings

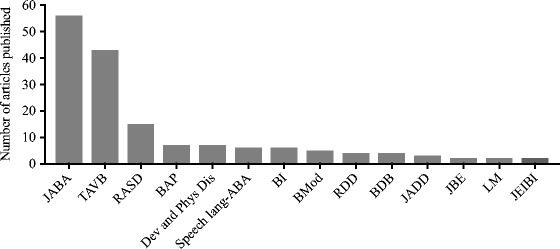

We identified a total of 172 studies published in 22 different journals between January 2001 and March 2017 that met our inclusion criteria. Across the studies, 493 participants met our inclusion criteria (i.e., 12 years old or younger with a diagnosis of ASD). The number of journals identified represents an increase from the list in the Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) review, which included studies published in 11 different journals. Figure 1 lists the 14 journals with more than one publication included in our review to show the distribution of articles across journals. For eight additional journals, only one publication per journal was included in our review. The majority of the studies were published in JABA (32%) and TAVB (25%). Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) noted a similar finding in their review and called for behavior analysts to publish empirical data on verbal behavior in journals beyond JABA and TAVB. Although these journals represent two of the most prominent applied research outlets in our field, continuing to publish almost exclusively in these journals may limit the dissemination and potential impact of our research. Therefore, we also would like to challenge future researchers to better disseminate research on verbal behavior to professionals outside of behavior analysis. It is important to continue publishing high-quality, tightly controlled experiments in JABA and TAVB, but it is also important to publish clinically relevant studies that would be beneficial for practitioners in journals they are more likely to come across.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of studies published between 2001 and 2017 in JABA, TAVB, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders (RASD), Behavior Analysis in Practice (BAP), Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities (Dev and Phys Dis), The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis (Speech lang-ABA), Behavioral Interventions (BI), Behavior Modification (BMod), Research in Developmental Disabilities (RDD), Behavioral Development Bulletin (BDB), Journal of Behavioral Education (JBE), Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (JADD), Journal of Behavioral Education (JBE), Learning and Motivation (LM), and Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention (JEIBI)

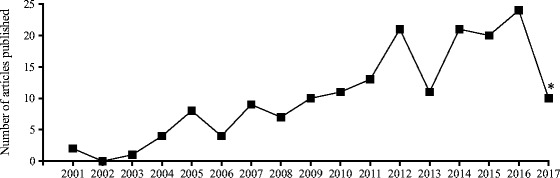

Figure 2 displays the number of publications we identified for each year of the 15-year review. The number of studies published per year has increased over time, with the most studies published in 2016 (24) and the fewest published in 2002 (0). We anticipate that this increasing trend will continue for 2017, as we identified 10 studies for the first 3 months of the year.

Fig. 2.

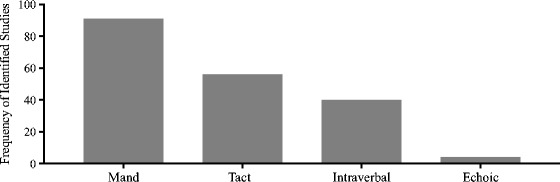

Frequency of studies for each verbal operant, including studies that tested for the emergence of untrained responses

Figure 3 displays the distribution of studies across verbal operants. Consistent with the results of previous reviews, the majority of the studies targeted the increase of mands (91 out of 172; 52.9%). Echoics served as the target response in the fewest studies (4 out of 172; 2.3%). In addition, among the 172 studies, 47 examined the emergence of untrained responses after the acquisition of a functionally different response. Several studies included more than one verbal operant as their dependent variable (e.g., Ross & Greer, 2003), particularly studies involving the emergence of verbal operants, so the total number of studies displayed in Fig. 2 is higher than the total of 172 studies included in this review. We summarize the literature according to Skinner’s primary verbal operants—mand, echoic, tact, and intraverbal—in the following sections.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of studies published between 2001 and 2017. The asterisk (*) denotes that the year 2017 only included the first 3 months of the year

Mands

The mand is a verbal response under the control of the relevant establishing operation (EO) and results in access to the corresponding reinforcer (i.e., the requested stimulus; Skinner, 1957). An example of a mand would be if a child, in a state of deprivation from water, says “drink” and receives access to a drink of water. As mentioned previously, 91 studies specifically targeted mands.

Researchers have used many different teaching procedures to facilitate the acquisition of mands. A variety of these procedures were evaluated by studies included in our review, such as manual sign training (e.g., Carbone, Sweeney-Kerwin, Attanasio, & Kasper, 2010), the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS; Jurgens, Anderson, & Moore, 2009), motor and vocal imitation training (e.g., Ross & Greer, 2003), discrete trial instruction (Jennett, Harris, & Delmolino, 2008), video modeling (e.g., Plavnick & Ferreri, 2011; Plavnick & Vitale, 2016), and differential reinforcement for vocal approximations (e.g., Thomas, Lafasakis, & Sturmey, 2010). Sundberg and Michael (2001) highlighted the importance of EOs for the acquisition of mands. Thus, researchers should ensure that EOs are the main controlling variables that evoke the mand response while examining different procedures during mand training.

Previous reviews have highlighted the importance of manipulating EOs to evoke “pure” mands. Many of the studies in this review also focused on this topic. We reviewed studies that evaluated the effects of contriving motivation on the acquisition of mands (e.g., Hartman & Klatt, 2005), generalization of mands (e.g., Fragale et al., 2012; Groskreutz, Groskreutz, Bloom, & Slocum, 2014), and maintenance of mands (e.g., O’Reilly et al., 2012). Other studies implemented procedures specifically to ensure that EOs controlled the targeted mands (e.g., Sweeney-Kerwin, Carbone, O’Brien, Zecchin, & Janecky, 2007) and tested for discriminated manding (Gutierrez et al., 2007). Overall, the majority of studies reviewed taught mands for access to positive reinforcement (e.g., Betz, Higbee, Kelley, Sellers, & Pollard, 2011); however, a few studies targeted mands for removal of aversive stimuli (e.g., Chezan, Drasgow, Martin, & Halle, 2016; Drasgow, Martin, Chezan, Wolfe, & Halle, 2016; Shillingsburg, Powell, & Bowen, 2013; Yi, Christian, Vittimberga, & Lowenkron, 2006). By manipulating EOs, researchers can evaluate the effect of low versus high levels of motivation on the acquisition of novel mands and the maintenance of acquired mands. Future research should try to identify how different levels of motivation as well as different levels of integrity might affect mand training using different teaching procedures.

Clinicians and researchers often include the question “What do you want?” when conducting early mand training. Bowen, Shillingsburg, and Carr (2012) evaluated the effects of mand training with and without the inclusion of this question on the acquisition and maintenance of mands. Results showed equivalent rates of mand acquisition with and without the question, and independent mands were maintained at comparable levels when the researchers discontinued use of the question. In a related study, Bourret, Vollmer, and Rapp (2004) developed a vocal mand assessment designed to assess (a) whether the child has the target mand in his or her repertoire, (b) how closely the emitted mand matches the targeted mand topographically, and (c) the degree to which emission of the mand depends on therapist-delivered prompts. They developed individualized treatments for mand acquisition based on the results of the assessment and found that the assessment-guided intervention increased independent mands for all three participants. These results are important because it is likely that caregivers may prompt their child by asking “What do you want?” during meals or snack times. However, therapists also should ensure that children request preferred items by spontaneously asking for them at times when no one has asked “What do you want?”

In addition to research on mand training procedures implemented by trained professionals, researchers have evaluated mand acquisition in children with ASD following training of caregivers (e.g., Chaabane, Alber-Morgan, & DeBar, 2009; Loughrey et al., 2014) or interventionists (e.g., Madzharova, Sturmey, & Jones, 2012; Neely, Rispoli, Gerow, & Hong, 2016; Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010) to implement the mand training procedures. Relatedly, Pence and St. Peter (2015) evaluated the acquisition of mands when experimenters implemented the treatment with varying, predetermined levels of integrity. Results indicated that it is important to train caregivers and other interventionists to implement mand training treatments with high levels of fidelity. Other studies compared different modalities of mands and assessed child and stakeholder preference for the different modalities. These comparisons included selection-based systems (e.g., card exchange) versus topography-based systems (e.g., sign language; Barlow, Tiger, Slocum, & Miller, 2013) and the PECS versus an iPad speech-generating device (Lorah, 2016; Lorah et al., 2013; Tincani, 2004). Barlow et al. found that all three participants acquired the selection-based mands more readily than the signs. Lorah et al. (2013) found that participants acquired mands via the PECS and an iPad with similar speed and accuracy but that they generally preferred the iPad-based modality over the PECS modality. The involvement of caregivers and other professionals is very important for the success of clinical goals. Future research should continue to investigate procedures to train other professionals and caregivers to implement mand training and should continue to investigate the effect of different levels of integrity on the acquisition and maintenance of mands in children with ASD.

Researchers also have trained children to accurately navigate more complex fields on speech-generating devices (Lorah, Crouser, Gilroy, Tincani, & Hantula, 2014a) and have examined how different displays on communication devices influence the acquisition of mands (Gevarter et al., 2014). For example, Lorah et al. (2014a) used a five-phase training protocol to teach discriminated mands; the protocol started with shaping the topography of the selection response and then gradually increased the complexity and difficulty of the discriminated mands (e.g., discriminated responding between a picture and blank boxes on the screen, discriminated responding between pictures of higher and lesser preferred items on the screen, and so on). All participants learned to select between four high-preference items such that the iPad-based mands corresponded to choices made during a brief multiple stimulus, without replacement stimulus preference assessment (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996).

Fourteen of the studies on mands specifically evaluated the effects of mand training on children’s engagement in destructive behavior (i.e., aggression, self-injury, and disruption; e.g., Greer, Fisher, Saini, Owen, & Jones, 2016). The majority of these studies implemented functional communication training (FCT) and trained children to engage in functional communication responses (FCRs) to access the functional reinforcer (e.g., Lang et al., 2013). These studies evaluated the effects of different FCR topographies on levels of destructive behavior (Danov, Hartman, McComas, & Symons, 2010; Derosa, Fisher, & Steege, 2015), preference for different FCR topographies (Torelli et al., 2016), and variability of FCR topographies (Adami, Falcomata, Muething, & Hoffman, 2017; Grow, Kelley, Roane, & Shillingsburg, 2008). Other topics in this section of the literature included generalization of FCRs across functional contexts (Falcomata, White, Muething, & Fragale, 2012), negatively reinforced FCRs (Yi et al., 2006), effects of response effort on response rates for mands and destructive behavior (Buckley & Newchok, 2005), and differences in obtained reinforcement and programmed reinforcement during FCT (Johnson, McComas, Thompson, & Symons, 2004). Three of these studies looked at fading the schedule of reinforcement for the FCR to be more practical (Falcomata, Muething, Gainey, Hoffman, & Fragale, 2013a; Falcomata, Wacker, Ringdahl, Vinquist, & Dutt, 2013b; Schlichenmeyer, Dube, & Vargas-Irwin, 2015). Although these studies represent a special case of mand training for which the ultimate goal was the reduction of destructive behavior, they still met the inclusion criteria for this review. Researchers engaged in this line of investigation should consider using the Skinner (1957) taxonomy of verbal behavior when referring to the FCR.

The studies reviewed up to this point have specifically targeted increasing basic mands, herein defined as one or a few words (e.g., noun–noun, verb–noun) emitted to gain access to preferred items. We will now turn our attention to studies that targeted more complex mands, herein defined as those involving multiple-word utterances (e.g., adjective–noun, preposition–noun) emitted to gain access to preferred items or to gain information.

Several studies focused on increasing not only the frequency of mand production but also the variability of mand emission. Increasing the frequency and variability of mand emission was accomplished by manipulating the schedule of reinforcement in one of the following ways: (a) differentially increasing ratio schedules for high-rate mands, (b) introducing lag schedules, or (c) introducing extinction for high-rate mands. For example, in one study, the researchers placed mands emitted via sign language on extinction and observed an increase in vocal mands (Valentino, Shillingsburg, Call, Burton, & Bowen, 2011). Similarly, Bernstein and Sturmey (2008) examined the effects of increasing the ratio requirement for one high-rate mand on the rate of other mands. They observed an increase in other mands as the response requirement for the target mand increased. Interestingly, the children still engaged in the target mand; therefore, the researchers induced variability without completely extinguishing the target mand. Researchers in three studies taught mand frames (e.g., “I want ___,” “Can I have ___”) for snack items using script fading and then altered the schedule of reinforcement to increase the variability of mand frames (Betz et al., 2011; Brodhead, Higbee, Gerencser, & Akers, 2016; Sellers, Kelley, Higbee, & Wolfe, 2016). Two of these studies evaluated extinction-induced variability before and after introducing script fading (Betz et al., 2011; Sellers et al., 2016). These researchers found that the introduction of extinction produced increases in varied responding following the teaching of additional responses via script fading. In an interesting extension, Brodhead et al. brought mand variability under stimulus control in which one stimulus signaled that varied responding produced reinforcement and the other stimulus signaled that repetitive responding produced reinforcement.

Teaching children to mand represents an important early skill; however, it is also important that children learn to emit mands to siblings and peers. Pellecchia and Hineline (2007) specifically assessed the generalization of mands from adults to peers. After training children to mand with instructors, they observed generalization to parents, but not to siblings and peers. The participants directed their mands to siblings and peers only after receiving direct training to do so, suggesting that specifically teaching peer-directed mands may be a necessary component of mand training. Researchers in two studies implemented differential reinforcement procedures (i.e., adult-directed mands placed on extinction) and prompting procedures to increase peer-directed mands for children using the PECS (Kodak, Paden, & Dickes, 2012b; Paden, Kodak, Fisher, Gawley-Bullington, & Bouxsein, 2012). Kodak et al. (2012b) also evaluated generalization to novel peers and naturalistic settings, which they observed without additional training for one participant, whereas the second participant required direct training of peer-directed mands. In addition to training children to mand to peers using the PECS, researchers have also evaluated peer-directed manding using a speech-generating device (Strasberger & Ferreri, 2014).

The aforementioned studies included some form of direct teaching on peer manding (e.g., prompting plus reinforcement) and although it may be reasonable to assume that the EO for mand emission was generally present during mand training across studies, the investigators did not directly manipulate and evaluate the effects of the EO in these studies. By contrast, Taylor et al. (2005) compared levels of peer-directed mands when they presented the presumed EO (i.e., restricted food access) and removed the presumed EO (i.e., made food access freely available). They found that participants accurately emitted peer-directed mands primarily in the presence of the presumed EO. These findings are promising; nevertheless, additional research is clearly needed to delineate the procedures that are necessary and sufficient for promoting the generalization of mand training from adults to peers.

Researchers in 17 studies evaluated procedures for increasing mands for information in children with ASD (e.g., “Where is the iPad?”). These investigations typically used one or more of the three primary components to increase mands for information: (a) increasing the value of the information through manipulation of the EO (e.g., evoking a “where” question by hiding a preferred toy); (b) prompting the target response in the presence of the EO if the child does not emit it independently (e.g., “Say ‘Where is the toy?’”); and (c) providing differential reinforcement for the target response (e.g., saying “The toy is under the box” following a correct mand).

Across these studies, experimenters taught children to mand for locations of preferred or missing items (i.e., “where”; Betz, Higbee, & Pollard, 2010; Endicott & Higbee, 2007; Howlett, Sidener, Progar, & Sidener, 2011; Lechago, Carr, Grow, Love, & Almason, 2010; Marion, Martin, Yu, Buhler, & Kerr, 2012a; Somers, Sidener, DeBar, & Sidener, 2014; Sundberg, Loeb, Hale, & Eigenheer, 2001); the identity of the individual in possession of a preferred or missing item (i.e., “who”; Endicott & Higbee, 2007; Shillingsburg, Bowen, Valentino, & Pierce, 2014b; Shillingsburg, Gayman, & Walton, 2016b; Sundberg et al., 2001); the information necessary to complete a task (i.e., “how”; Lechago, Howell, Caccavale, & Peterson, 2013; Shillingsburg, Bowen, & Valentino, 2014a; Shillingsburg & Valentino, 2011); the identity of the container holding the preferred item (i.e., “which”; Marion et al., 2012b; Shillingsburg et al., 2014b); and the name of an unknown object (i.e., “what”; Marion, Martin, Yu, & Buhler, 2011; Roy-Wsiaki, Marion, Martin, & Yu, 2010).

Researchers in two other studies taught children to ask for the answer to unknown questions by saying “I don’t know, please tell me” (Carnett & Ingvarsson, 2016; Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2010). The final study taught participants to request general social information (e.g., “What do you like to eat?”; Shillingsburg, Frampton, Wymer, & Bartlett, 2016a). Asking questions is widely observed during reciprocal conversation in typical social interactions. Teaching children with ASD to ask reciprocal questions of others might be a challenging task when the consequence of these responses (i.e., asking questions) is not a tangible reinforcer but a conditioned reinforcer (i.e., the answer of the conversation partner). Future research should investigate the effects of teaching children with ASD to ask questions to gain access to preferred items on the levels of reciprocal questions emitted by these children during conversation with peers and adults.

Researchers have attempted to incorporate strategies on emergent responding and mand training as a means to facilitate the emergence of mands. An emergent mand refers to a mand that has never been directly prompted or reinforced and that emerged after the training of another response (Murphy, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2005). In one such example, researchers taught participants to mand for two different types of tokens (each necessary to fill a token board; Murphy et al., 2005). The mands that the investigators directly taught involved exchanging a stimulus card (either A1 or A2) that corresponded to a token (either X1 or X2). After receiving direct training to exchange the appropriate stimulus card to request the corresponding token (e.g., Stimulus A1 produces Token X1), the experimenters exposed participants to conditional discrimination training in which they trained relations of equivalence between Stimulus A and Stimulus B and between Stimulus B and Stimulus C. After training these relations, the participants emitted the correct Stimulus C mands to produce the corresponding tokens (e.g., Stimulus C1 to obtain Token X1). In a similar experiment, experimenters taught participants to mand for additional or fewer tokens in order to fill a token board (Murphy & Barnes-Holmes, 2009). After receiving training across stimulus relations, participants demonstrated the emergence of mand responses for the more–less relation. In a more applied intervention involving equivalence training, researchers taught participants to mand for missing items using pictures on a tablet. They then trained equivalence relations among pictures, text, and spoken words and tested for the emergence of mands using text (Still, May, Rehfeldt, Whelan, & Dymond, 2015). Ten out of the 11 participants demonstrated the emergence of mands. Taken together, these studies suggest that teaching situations can be contrived to facilitate the emission of novel, untrained mand responses when proper EOs are present.

The majority of studies involving emergent relations of mand responses focused on the effects of mand and tact training on the emergence of novel tacts and mands (e.g., Kelley, Shillingsburg, Jicel Castro, Addison, & LaRue, 2007; Luke, Greer, Singer-Dudek, & Keohane, 2011), the effect of tact training on the emergence of mands (e.g., Egan & Barnes-Holmes, 2010; Still et al., 2015), and the effect of mand training on the emergence of tacts (Albert, Carbone, Murray, Hagerty, & Sweeney-Kerwin, 2012; Egan & Barnes-Holmes, 2009). Gilliam, Weil, and Miltenberger (2013) used a multiple-baseline design across three children with ASD to test for the emergence of mands after tact training of high-preference and low-preference items. The results demonstrated that although all children required about the same number of sessions to acquire the tacts of both high-preference and low-preference items, they emitted relatively more mands of high-preference items than of low-preference items during impure mand probes. This study illustrates how one can arrange conditions to promote the emergence of untrained verbal operants and illustrates the role of EOs in the emission of a mand repertoire, as suggested by Sundberg and Michael (2001).

Overall, the mand remains the most researched verbal operant, and the research base on mands continues to grow. In addition, researchers have increasingly conducted investigations designed to promote the acquisition and emission of more complex mands and investigations of training procedures that promote the emergence of novel, untrained mands. We believe that future research on mands should continue to address the conditions that facilitate the emergence of untrained mands and the development of more complex forms of mands. Specifically, future research could focus on mand frames using adjectives, prepositions, pronouns, and adverbs as descriptors of desired items.

Tacts

The tact is a verbal response under the control of a nonverbal stimulus and produces generalized conditioned reinforcement (e.g., “You’re right”; Skinner, 1957). An example of a tact is when a car passes by (i.e., the nonverbal stimulus), a child with ASD says “car” (i.e., the tact), and this produces praise from the therapist (i.e., the generalized conditioned reinforcer). Fifty-six of the 172 studies in this review specifically targeted an increase in tacts. Several of these studies compared different teaching procedures for tact acquisition. Procedural comparisons included an evaluation of continuous versus discontinuous data collection methods (Giunta-Fede, Reeve, DeBar, Vladescu, & Reeve, 2016); various trial formats (e.g., massed vs. distributed; Majdalany, Wilder, Greif, Mathisen, & Saini, 2014); different prompting strategies (e.g., echoic vs. multiple-alternative prompts; Carbone et al., 2006; Leaf et al., 2016; Pérez-González, Pastor, & Carnerero, 2014); error correction (e.g., tutor- vs. machine-modeled error correction; Ferris & Fabrizio, 2009; Turan, Moroz, & Croteau, 2012); group and individual instructional feedback (Grow, Kodak, & Clements, 2017; Leaf et al., 2017); and different arrangements of reinforcement (e.g., smaller vs. larger reinforcers; Boudreau, Vladescu, Kodak, Argott, & Kisamore, 2015; Majdalany, Wilder, Smeltz, & Lipschultz, 2016).

Two studies compared the effects of tact trials with and without vocal instructions (e.g., “What is it?”) on acquisition (Marchese, Carr, LeBlanc, Rosati, & Conroy, 2012) and generalization of tacts (Williams, Carnerero, & Pérez-González, 2006). These researchers found that some children acquired the tacts more efficiently with the instruction and some without the instruction, but at least one target needed to be taught without the verbal instruction for generalization to occur.

The aforementioned studies implemented tact training with the primary goal of increasing verbal behavior. In contrast, Guzinski, Cihon, and Eshleman (2012) evaluated how the acquisition of tacts affected children’s engagement in vocal stereotypy. This study represents an interesting extension of the literature, as the researchers demonstrated that the acquisition of tacts led to a decrease in stereotypy. This study aligns well with the previous discussion of FCT, and future research should continue to examine how teaching functional (i.e., meaningful) verbal behavior, beyond mands, may produce a concomitant decrease in stereotypy or problem behavior.

Studies on more advanced forms of tact training have also been conducted. Fluency is the combination of accurate responding with a targeted response rate (i.e., the fluency aim) and is important for the maintenance and transfer of skills (Binder, 1996), including tacting common objects. Kelly and Holloway (2015) assessed the effectiveness of introducing behavioral momentum (i.e., a sequence of high-probability tacts followed by the target low-probability tact) on the fluency (i.e., correct responses per minute) of low-probability tacts. This intervention increased the fluency of low-probability tacts for all three participants. Other studies have focused on increasing the use of tacts within sentences. One study examined the use of an iPad to teach children how to tact “I have ___” and “I see ____” (Lorah, Parnell, & Speight, 2014c); another study used matrix training to increase tacts with subject–verb–object sentence structures (Kohler & Malott, 2014). These studies represent an important shift in the literature moving toward more advanced tact repertoires.

In addition to investigating how to increase the length of tact statements, researchers have examined interventions to target more complex tacts, including tacting private events, inferring the emotions of others, and metonymical tacts. McKeel, Rowsey, Belisle, Dixon, and Szekely (2015) used a curriculum called the Promoting Emergence of Advanced Knowledge Relational Training System: Direct Training Module (PEAK-DT; Dixon, 2014) to teach autoclitics, tacting planets, metonymical tacts, and guessing, which proved to be effective for the three participants.

Conallen and Reed (2016) taught children to tact the emotions of others in an intraverbal format (e.g., “His friends came to play; how does he feel?”). They then tested for generalization to untrained situations and assessed whether participants could tact their own emotions. The participants accurately tacted the emotions of others in untrained situations as well as their own emotions. Conallen and Reed (2017) also taught children to tact emotions about ongoing activities using the PECS (e.g., a child used the PECS to tact emotions after completing a coloring task by expressing “like coloring”). They found that children with ASD learned to tact private events, such as “boring,” “fun,” and “like,” and also learned to tact these private events within more complex sentence structures.

Currently, the majority of studies on tact training have focused on the direct teaching of tacts. However, recently the number of studies targeting the emergence of novel tacts without direct training has increased. In fact, the majority of studies in this review that targeted the emergence of novel verbal responses involved tacts as one of the dependent variables. In addition to the studies cited in the Mands section that tested for the emergence of tacts following mand training, we identified 14 studies that examined the emergence of novel tact responses following listener training (e.g., Frampton, Robinson, Conine, & Delfs, 2017; Olaff, Ona, & Holth, 2017; Sprinkle & Miguel, 2012) and three studies that examined the emergence of novel tact recombination after tact training (Frampton, Wymer, Hansen, & Shillingsburg, 2016; Kohler & Malott, 2014; Leaf et al., 2017).

In a study by Kobari-Wright and Miguel (2014), four children with ASD learned to select pictures when presented with the auditory category names (e.g., “Give me the hound dog”), and the investigators probed for the emergence of listener categorization responses (e.g., matching pictures belonging to the same category) and tact responses (e.g., saying “hound dog” when presented with the picture of a hound dog and asking “What is it?”). Three participants demonstrated the emergence of listener categorization and tacts following listener training, whereas one participant required direct tact training before showing correct categorization responses. The authors suggested that it is important for children to demonstrate the bidirectionality of tact and listener repertoire, also known as naming (Horne & Lowe, 1997), before addressing categorization responses.

We recommend that future researchers continue to move toward evaluating more complex tacting repertoires, including identifying effective procedures for promoting the emergence of novel tacts. Other areas that may be rich for research are the emergence of complex tact repertoires involving adjectives (e.g., big, small), pronouns (e.g., my, yours), and prepositions (e.g., under, over).

Echoics

The echoic is a verbal response under the control of a verbal stimulus with point-to-point correspondence between the stimulus and the response (i.e., the antecedent verbal stimulus and the verbal response match each other) and produces generalized conditioned reinforcement (Skinner, 1957). An example of an echoic might involve a therapist saying “dog” (i.e., the verbal stimulus), followed by the child with ASD saying “dog” (i.e., the echoic) and then the therapist saying “Great job!” (i.e., the generalized conditioned reinforcer). Several studies in this review included echoics as a controlling prompt or as part of the procedure for examining the emergence of other verbal operants (e.g., intraverbals; Shillingsburg, Frampton, Cleveland, & Cariveau, 2017). However, we only identified four studies published since 2001 that targeted echoics as the primary dependent measure. Two of the four studies used a stimulus–stimulus pairing procedure to increase vocalizations and then evaluated procedures to bring these vocalizations under echoic control (Carroll & Klatt, 2008; Esch, Carr, & Michael, 2005). One study found this procedure effective (Carroll & Klatt, 2008), whereas the other did not (Esch et al., 2005). A third study used a chaining procedure to increase the echoic repertoire (Tarbox, Madrid, Aguilar, Jacobo, & Schiff, 2009). The chaining procedure consisted of breaking the targeted echoic (e.g., “ball”) into smaller units (e.g., “b” and “all”) and then chaining the echoing of each unit until the participant echoed the full target response. This procedure effectively increased echoics for both participants. Future research should compare the effects of backward versus forward chaining procedures in the acquisition of echoic responses involving one- to three-syllable words.

We identified only one study that targeted the emergence of echoic responses. Speckman-Collins, Lee Park, and Greer (2007) reported on the emergence of echoic responses while testing for the emergence of mands and tacts after training auditory match-to-sample repertoires to young children diagnosed with ASD. Results showed that both children demonstrated the emergence of untrained responses, echoics, mands, and tacts after training on the auditory match-to-sample repertoire. Like the study by Speckman-Collins et al., studies involving verbal operants should periodically probe and report additional data that evaluate the effects of listener and speaker training on the emergence of novel echoic responses.

Although only 4 studies out of 172 specifically targeted echoics, this does not undermine the importance of echoics as a verbal operant. Echoics are important because bringing vocalizations under echoic control facilitates their use as controlling prompts to teach other verbal operants. In addition, it is possible that echoics may play a role in more complex topographies of verbal behavior such as problem solving and self-prompts (e.g., Kisamore, Carr, & LeBlanc, 2011). It is likely that more research studies have been conducted on increasing echoic behavior; however, we may not have captured all of them using our search criteria because the authors of those studies did not use the terminology according to Skinner’s (1957) taxonomy of verbal behavior (e.g., calling such responses vocal imitation rather than echoic responses; cf. Ross & Greer, 2003). Because this review specifically analyzed studies targeting the verbal operants from Skinner’s taxonomy of verbal behavior, we may have excluded some such studies. We encourage future researchers to use the terminology proposed by Skinner (1957) and to continue examining the most effective teaching procedures for promoting echoic responding. Specifically, future research should evaluate procedures to establish an initial echoic repertoire (e.g., vowels and consonants) in minimally vocal children as well as procedures to advance the complexity of echoic responses (e.g., sentences) in children with ASD.

During our literature review, we identified some studies that focused on increasing vocalizations that we did not include in this review because they did not meet our inclusion criteria (i.e., the main dependent variable is one of Skinner’s verbal operants: mand, tact, echoic, or intraverbal). For example, several researchers have evaluated the use of stimulus–stimulus pairings as a procedure for increasing children’s vocalizations. Stimulus–stimulus pairing represents a potentially viable procedure for increasing vocalizations prior to initiating echoic training (Shillingsburg, Hollander, Yosick, Bowen, & Muskat, 2015). Generally, during this procedure a therapist presents a simple target sound (e.g., “em,” “goo”) one to five times and either concurrently or immediately thereafter presents a high-preference stimulus (Carroll & Klatt, 2008; Lepper, Petursdottir, & Esch, 2013). It is possible that by pairing the sound with a highly preferred stimulus, the sound will become a conditioned reinforcer and, when emitted by the child in the future, might be maintained by automatic reinforcement. As a consequence, with the increase of automatically maintained sounds (e.g., babbling), a therapist can establish the child’s echoic repertoire by delivering social positive reinforcement contingent on appropriate echoic responses (Skinner, 1957). Sundberg and Michael (2001) argued that automatic reinforcement plays an important role in the development of early vocalizations as well as in complex language such as grammatical speech. However, this hypothesis remains largely untested, and it should be specifically evaluated in future research.

Shillingsburg et al. (2015) conducted a review of the literature on the stimulus–stimulus pairing procedure with children with language delays. Results indicated that the procedure produced moderate increases in vocalizations overall, but the effects varied considerably across participants, with younger children (less than 5 years old) responding somewhat better than older children. The authors concluded that additional data are required before clear recommendations can be given regarding when to use the stimulus–stimulus pairing procedure and with whom. Future research should be aimed at determining whether exposure to the stimulus–stimulus pairing procedure facilitates the acquisition of echoic responses in children with ASD.

Intraverbals

The intraverbal is a verbal response under the control of (a) a topographically dissimilar antecedent verbal stimulus and (b) generalized conditioned reinforcement (Skinner, 1957). For example, after a therapist says, “What is a vehicle that flies?” (i.e., the antecedent verbal stimulus), a child with ASD says “airplane” (i.e., the intraverbal response, which does not match the antecedent stimulus), and then the therapist says, “That’s right!” (i.e., the generalized conditioned reinforcer). Intraverbal responses can range from simple to advanced and can be of infinite number (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). We identified 40 studies involving intraverbal responses as one of the primary dependent variables. Seven studies focused on evaluating the effectiveness of various prompt strategies, including textual prompts (e.g., Emmick, Cihon, & Eshleman, 2010; Finkel & Williams, 2001; Vedora, Meunier, & Mackay, 2009), echoic prompts (e.g., Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011; Ingvarsson & Le, 2011), and tact prompts (e.g., Goldsmith et al., 2007; Kodak, Fuchtman, & Paden, 2012a) during intraverbal training.

Training procedures for establishing initial intraverbal responses have generally used transfer-of-stimulus-control methods in which the antecedent verbal stimulus is presented (e.g., “What is your name?”) and then the correct response is prompted via an existing verbal operant (e.g., an echoic) followed by the delivery of a highly preferred stimulus as reinforcement. Over time, the prompt is faded to transfer stimulus control to the antecedent verbal stimulus. For example, Ingvarsson and Hollobaugh (2011) compared the efficacy of two prompting strategies—tacts and echoic prompts—to teach three children with ASD intraverbal responses in the form of answering questions (e.g., “What do you use to tell time?”). During the tact prompt condition, the experimenter presented a picture card that reliably occasioned a tact (i.e., a picture of a clock for the question “What do you use to tell time?”) contingent on incorrect responses or no responses for one set of questions. During the echoic prompt condition, the experimenter presented an echoic prompt (i.e., said “Say scissors” for the question “What do you use to cut paper?”) contingent on incorrect responses or no responses for another set of questions. Both prompting strategies proved to be effective in teaching the intraverbal responses; however, the tact prompt produced criterion-level performance in fewer trials.

Finkel and Williams (2001) and Vedora et al. (2009) also found tact prompts to be superior to echoic prompts in teaching intraverbal responses when the tact prompt consisted of the correct response presented textually (e.g., the written word read presented as the prompt following the question “What do you do with a book?”). Vedora et al. suggested that echoic prompts can be harder to fade than tact prompts for many children with ASD. However, Kodak et al. (2012a) compared cue–pause–point procedures (McMorrow, Foxx, Faw, & Bittle, 1987) with echoic and tact prompts (each combined with error correction) and found that only echoic prompts combined with error correction resulted in consistent acquisition of intraverbal responses across participants. These results suggest that error correction may facilitate the fading of echoic prompts when teaching intraverbal responses to children with ASD. As such, future researchers should compare the effectiveness of echoic and tact prompts with and without error correction during initial intraverbal training.

Twelve studies evaluated the effects of antecedent (e.g., repeating vs. not repeating the discriminative stimulus at each prompting step; Humphreys, Polick, Howk, Thaxton, & Ivancic, 2013) or consequence (e.g., token reinforcement vs. natural contingencies; Mason, Davis, & Andrews, 2015) manipulations during intraverbal training, as well as the outcomes of different instructional formats in the acquisition of intraverbal responses (e.g., blocked trials; Haggar, Ingvarsson, & Braun, 2017). Haq et al. (2015) compared intraverbal acquisition of massed and distributed trials in three children with ASD. During massed trials, the experimenter conducted all training opportunities 1 day during each week; during distributed trials, the experimenter conducted all training opportunities across several days during the week. The distributed trials format resulted in more efficient acquisition of intraverbal responses (relative to the massed trials format) for all participants. Studies comparing the effectiveness and efficiency of teaching procedures commonly used in clinical settings are important because they offer guidance to clinicians for best-practice intervention. Researchers should continue to evaluate and compare the effects of different teaching procedures on the acquisition of verbal repertoires in children with ASD.

Five studies focused on response variability (Carroll & Kodak, 2015; Contreras & Betz, 2016) and the training of advanced intraverbal repertoires (e.g., storytelling; Valentino, Conine, Delfs, & Furlow, 2015). For example, Kisamore, Karsten, and Mann (2016) compared the effects of trial-and-error training, differential observing response (DOR), and DOR plus trial-blocking procedures to teach intraverbal responses under multiple control to five children between the ages of 4 and 12 who had been diagnosed with ASD. During the trial-and-error training, the therapist provided praise and a tangible item following a correct response, re-presented the trial, and prompted the target response on a 0-s delay. During the DOR procedure, the experimenter presented the antecedent stimulus (e.g., “What’s an animal that’s red?”), prompted the child to emit the DOR (e.g., “Say animal red”), waited for the participant to emit the DOR, and re-presented the antecedent stimulus. The investigators implemented the DOR plus trial-blocking procedure for participants who did not reach mastery levels with the trial-and-error or DOR procedures. For the trial-blocking component, the investigators presented 20 consecutive trials for each target and then systematically faded to irregular block sizes. The results indicated that although some participants acquired at least one set of targets with the trial-and-error procedure, most participants required additional procedures (e.g., DOR, DOR plus trial blocking) in order to acquire intraverbals under multiple control.

Studies involving intraverbal responding and advanced repertoires have addressed some of the issues raised by Sundberg and Michael (2001) for teaching children with ASD to respond to questions about personal information (e.g., “What’s your name?”; Finkel & Williams, 2001), provide multiple answers for categories (e.g., “What are some animals?”; Carroll & Kodak, 2015), respond to yes–no questions (e.g., Shillingsburg, Kelley, Roane, Kisamore, & Brown, 2009), and tell stories (Valentino et al., 2015). These studies provide a small demonstration of the variety of topographies and levels of complexity of intraverbal response. However, when taken together, these topographies provide foundations for conversation skills (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011) that are important for social skill development. Future research should investigate the role of intraverbals in the development of conversation skills in children with ASD.

Intraverbal responses are also often required in the academic environment, where children are expected to answer questions, tell stories, engage in problem-solving behavior, describe events, and interact socially with peers. Hence, a poor intraverbal repertoire may compromise academic achievement and social skill development. In the context of intervention for children with ASD, one of the challenges involving the acquisition of advanced intraverbals is the fact that intraverbals are controlled by multiple verbal antecedent stimuli (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). Therefore, the demonstration of conditions under which complex intraverbals are emitted is paramount for the understanding of a child’s language development and for the implementation of interventions that can effectively address language delays.

Palmer (2016) argued that behavior analysts have often classified a wide variety of verbal responses occasioned by a verbal stimulus as intraverbal behavior, regardless of whether the verbal stimulus exerted singular stimulus control over the response (e.g., answering “blue” to the question “What color is the sky?”) or whether the verbal stimulus along with other stimuli controlled the response (e.g., answering the question “What is the capital of Delaware?” only after completing a Google search). Both of these questions exert some degree of intraverbal control over the answers, but Palmer suggested that we reserve the term intraverbal for verbal responses evoked by the verbal stimulus without the need for additional antecedent or mediating variables because this narrower definition retains the explanatory implications of the term intraverbal. That is, applying the label intraverbal to the answer “blue” in response to the question “What color is the sky?” strongly implies that the individual acquired this response through a history of generalized reinforcement for emitting that response under similar stimulus conditions in the past. By contrast, Palmer (2016) argues that we should not refer to the answer to the question “What is the capital of Delaware?” as an intraverbal response because to do so would “give the illusion of explaining the response when we have not done so” (p. 99). This latter response is under intraverbal control but is also controlled by other variables, and its establishment cannot be attributed solely to a history of generalized reinforcement under similar stimulus conditions in the past. Researchers investigating intraverbal behavior and complex verbal behavior should consider the important distinction Palmer makes between intraverbal responses (those responses specifically evoked by the intraverbal stimulus) and intraverbal control, which may interact with other antecedent variables to occasion a wide variety of multiply controlled verbal responses. See Palmer (2016) for an extended discussion of intraverbal control and its role in complex verbal responses.

Sundberg and Michael (2001) suggested that an intraverbal repertoire can facilitate the acquisition of other verbal and nonverbal responses, as well as advanced conversation skills and the ability to respond to novel verbal stimuli. However, many children with ASD tend to demonstrate limited intraverbal repertoires even though they might emit hundreds of tact and mand responses (Sundberg & Michael, 2001).

Although the notion of functional independence of verbal operants has been empirically demonstrated (e.g., Lamarre & Holland, 1985), several studies have shown that conditions can be created to facilitate the emergence of intraverbal responses following the training of other verbal operants (e.g., tact training). Sixteen studies focused on the emergence of intraverbal responses following tact and listener training (Grannan & Rehfeldt, 2012; Shillingsburg et al., 2017); tact training only (Cihon et al., 2017); listener training (e.g., Dixon et al., 2017; Kodak & Paden, 2015; Vallinger-Brown & Rosales, 2014); and different intraverbal responses (Allan, Vladescu, Kisamore, Reeve, & Sidener, 2015; Dickes & Kodak, 2015; Greer, Yaun, & Gautreaux, 2005).

For example, Smith et al. (2016) demonstrated the emergence of intraverbal responses in the form of answering questions (e.g., “What’s an animal that flies?”) after listener training involving the same set of questions. During training, the experimenter presented the picture cards in front of the participant and delivered the discriminative stimulus (e.g., “What’s a food that’s green?”). A correct response consisted of the participant touching the target picture (e.g., apple). The experimenter conducted intraverbal probes once per week. Four participants demonstrated the emergence of intraverbal responses after mastering listener responding. One participant required an extra training procedure that involved the tacting of the picture card during the selection of the target response. These studies demonstrated the emergence of intraverbals following training of tact and listener responding. According to Sundberg and Sundberg (2011), tact and listener responding is the foundation for an advanced intraverbal repertoire. In other words, generalized tact and listener responding should be established in a child’s repertoire first before one attempts to teach advanced intraverbals, which are often emitted under multiple control (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). Additional research is needed to demonstrate the role of tacts and listener repertoires in the acquisition and emergence of advanced intraverbals.

Research involving intraverbal responses has substantially increased since the study conducted by Sundberg and Michael (2001); Aguirre, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016), but future investigation into the variables controlling intraverbal behavior is clearly needed. Future research should continue investigating procedures to teach advanced intraverbal responses such as telling stories, which may often be under multiple control. In addition, future research should investigate the prerequisites for the emergence of novel, advanced intraverbals without direct training.

Summary and conclusions

The number of empirical studies focusing on Skinner’s (1957) verbal operants has increased since Sundberg and Michael’s (2001) review, and these studies have become substantially more prevalent in most behavior–analytic journals (Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006). In particular, research focusing on the acquisition of verbal behavior in children with ASD has demonstrated an increasing trend across 15 years (Fig. 3), possibly as a result of the scientific community’s interest in empirically corroborating Skinner’s assertion involving verbal behavior and verbal operants combined with the strong validation of applied behavior analysis as an evidence-based treatment for children with ASD (Roane, Fisher, & Carr, 2016).

Some of the discussion topics raised by Sundberg and Michael (2001) in their review (i.e., mand training and intraverbal development) have received increased attention in the past 15 years. Studies involving the development of mands, either for skill acquisition or for replacement of problem behavior (i.e., FCT), have been prominent in behavior–analytic journals. These studies evaluated a large range of topics, from the acquisition of simple mands (e.g., Jennett et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2010), which are necessary for early learners and children with poor verbal repertoires, to more advanced mands such as mands for information (e.g., Somers et al., 2014), mands with qualifying autoclitics (e.g., Luke et al., 2011), and mand variability (e.g., Brodhead et al., 2016), which are important for the development of complex conversational and social skills. Many studies have also investigated the role of EOs in the acquisition of mands (e.g., Lechago et al., 2010) and have demonstrated how EOs can influence the emergence of mands without direct training (e.g., Gilliam et al., 2013).

Another line of research that has received increased attention from the scientific community is that of FCT. Teaching mands to replace maladaptive behavior is a priority in early intervention programs because it not only enables children to effectively recruit reinforcement but also leads to dramatic life improvements by reducing behaviors that can be harmful for the individual or others (Tiger, Hanley, & Bruzek, 2008). Recent research efforts in this area have focused on increasing the effectiveness and practicality of FCT in natural environments using multiple and chain schedules so that children request the functional reinforcer via a mand at appropriate times (e.g., Greer et al., 2016; see Saini, Miller, & Fisher, 2016, for a review). Other studies have focused on preventing treatment relapse when a mand fails to produce the functional reinforcer for an extended period of time (e.g., Fuhrman, Fisher, & Greer, 2016; Volkert, Lerman, Call, & Trosclair-Lasserre, 2009; Wacker et al., 2013). Future research in the area of FCT should focus on expanding the stimulus control of mands so that as the child’s mand repertoire grows, those mands are brought under conditional stimulus control so that each mand is emitted only at appropriate times (e.g., manding to play on the swings only during recess, manding for food only at meal or snack times; cf. Akers et al., 2017).

The intraverbal repertoire of a typical child is almost infinite, ranging from completing songs (e.g., after the parent says “The wheels on the bus go. .. ,” the child says “round and round”), providing sounds that animals make (e.g., “The kitty says. ..” “meow”), and responding to simple personal questions (e.g., “What’s your name?”) to answering multiply controlled “Wh—” questions, describing past events, and engaging in back-and-forth conversation (Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011). Importantly, as children reach school age, they are increasingly asked to emit novel intraverbal responses that they have never before said and for which they have never before received direct instruction (e.g., solving the riddle “What has to be broken before you can use it?”). Because of the extensive nature of typical intraverbal repertoires, it is important for researchers to develop and evaluate behavioral procedures that promote the emergence of novel and complex intraverbal behavior.

DeSouza, Fisher, and Rodriguez (2017) demonstrated the emergence of advanced intraverbals under multiple control in four children with ASD who had not previously displayed such skills (e.g., “A tool used for cutting is a. ..” “scissors” vs. “A tool used for scooping is a. ..” “shovel” vs. “A utensil used for cutting is a. ..” “knife” vs. “A utensil used for scooping is a. ..” “spoon”). For all four children, the targeted intraverbal responses emerged without direct training after the experimenters provided direct training for four skills suggested by Sundberg and Sundberg (2011) to serve as prerequisites for the emergence of advanced intraverbals (i.e., multiple-tact training, listener responding training, intraverbal categorization training, and listener compound discrimination training). DeSouza et al. demonstrated that direct training in these prerequisite skills resulted in the emergence of complex intraverbal responses at mastery levels, but the design did not allow the investigators to determine whether all of the prerequisite skills were necessary for the emergent effects or whether it was necessary to train the skills in a specific order. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study that demonstrated the emergence of novel, complex intraverbals under multiple control in children with ASD who had not previously displayed such behavior. Future researchers should conduct a component analysis of this intervention (i.e., analyze the role of each prerequisite skill) to determine the necessary and sufficient treatment elements required to promote the emergence of multiply controlled intraverbal behavior in young children with ASD.

Skinner (1957) asserted that (a) each verbal operant is maintained by different antecedents and consequences and (b) the establishment of one type of verbal response will not automatically occasion the acquisition of another type of verbal response involving the same spoken topography. For example, a child who learns to ask for a “cookie” as a mand will not necessarily say “cookie” as a tact upon seeing a picture of a cookie. Both responses may need to be independently established in the child’s repertoire. Skinner’s assertion influenced a number of studies that have evaluated the notion of functional independence of verbal operants and also helped to elucidate the conditions necessary for promoting the emergence of untrained responses (Grow & Kodak, 2010).

In the current review, we identified several studies that focused on the emergence of verbal operants as a means to expand the verbal repertoires of children with ASD. In addition to the studies that investigated the emergence of mands, tacts, echoics, and intraverbal responses, we also identified a few studies that examined the emergence of listener responding after mand training (e.g., Murphy et al., 2005), tact training (e.g., Miguel & Kobari-Wright, 2013), and intraverbal training (e.g., Ingvarsson, Cammilleri, & Macias, 2012). Although listener responding is not technically a component of Skinner’s (1957) taxonomy of verbal behavior of the speaker, it is important to note that several of the research studies that evaluated emergent stimulus relations involved some type of listener training. Of the studies that evaluated emergence identified in the current review of the literature, 28 involved listener training or the emergence of listener responses. Skinner (1957) recognized the importance of the behavior of the listener and suggested that a complete account of verbal behavior should encompass both speaker and listener behavior. Future research should continue to evaluate the role of listener behavior in the emergence of speaker repertoire (i.e., mand, echoic, tact, intraverbal).

Similar to the results of Sautter and LeBlanc (2006), the results of the current review show that mands and tacts have received most of the attention from behavior–analytic researchers, followed by intraverbals and then echoics. We encourage researchers to increase their efforts in investigating the acquisition of intraverbals, specifically that of complex intraverbal and conversation skills. As for echoics, we suggest that future research should investigate procedures to promote the acquisition of generalized echoic repertoires in children with ASD, especially those with highly limited vocal repertoires. In summary, the literature on verbal behavior interventions for children with ASD has increased substantially in the past 15 years. In response to Sundberg and Michael’s (2001) as well as Michael’s (1984) concerns, the current results suggest that researchers have increasingly used Skinner’s (1957) taxonomy, as opposed to more traditional linguistic terminology, when conducting behavior–analytic research on verbal behavior with children with ASD. Many studies have investigated procedures for directly teaching verbal operants, whereas others have examined procedures designed to promote novel verbal operants that emerge without direct training. However, to our knowledge, few studies have addressed the acquisition of complex skills such as storytelling and problem solving. Thus, although our field has made substantial progress in addressing the concerns raised by Sundberg and Michael, their review remains timely and relevant, as considerably more research is needed on the procedures and mechanisms critical to the establishment of functional verbal repertoires in children with ASD and particularly those procedures that promote the acquisition and fluent expression of complex verbal behavior.

Conflicts of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal studies

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Adami S, Falcomata TS, Muething CS, Hoffman K. An evaluation of lag schedules of reinforcement during functional communication training: Effects on varied mand responding and challenging behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10:209–213. doi: 10.1007/s40617-017-0179-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre AA, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Empirical investigations of the intraverbal: 2005–2015. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers, J., Fisher, W. W., Kaminskin, J., Greer, B. D., DeSouza, A., & Retzlaff, B. (2017). An evaluation of conditional manding using a four component multiple schedule. In V. Saini (Chair), Recent Advances in Methods to Improve Functional Communication Training. Symposium conducted at the 43rd Annual Convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Denver, CO.

- Albert KM, Carbone VJ, Murray DD, Hagerty M, Sweeney-Kerwin EJ. Increasing the mand repertoire of children with autism through use of an interrupted chain procedure. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5:65–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03391825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi G. Generative strategies and teaching for generalization. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1987;5:15–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03392816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan AC, Vladescu JC, Kisamore AN, Reeve SA, Sidener TM. Evaluating the emergence of reverse intraverbals in children with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2015;31:59–75. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera ML, Kubina RJ. Using transfer procedures to teach tacts to a child with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:155–161. doi: 10.1007/BF03393017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow KE, Tiger JH, Slocum SK, Miller SJ. Comparing acquisition of exchange-based and signed mands with children with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2013;29:59–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03393124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein H, Sturmey P. Effects of fixed-ratio schedule values on concurrent mands in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2008;2:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betz AM, Higbee TS, Pollard JS. Promoting generalization of mands for information used by young children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;4:501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betz AM, Higbee TS, Kelley KN, Sellers TP, Pollard JS. Increasing response variability of mand frames with script training and extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:357–362. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder C. Behavioral fluency: Evolution of a new paradigm. The Behavior Analyst. 1996;19:163–197. doi: 10.1007/BF03393163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloh C. Assessing transfer of stimulus control procedures across learners with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2008;24:87–101. doi: 10.1007/BF03393059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau BA, Vladescu JC, Kodak TM, Argott PJ, Kisamore AN. A comparison of differential reinforcement procedures with children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48:918–923. doi: 10.1002/jaba.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourret J, Vollmer TR, Rapp JT. Evaluation of a vocal mand assessment and vocal mand training procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:129–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CN, Shillingsburg MA, Carr JE. The effects of the question “what do you want?” on mand training outcomes of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:833–838. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Higbee TS, Gerencser KR, Akers JS. The use of a discrimination-training procedure to teach mand variability to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:34–48. doi: 10.1002/jaba.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley SD, Newchok DK. Differential impact of response effort within a response chain on use of mands in a student with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BL, Rehfeldt RA, Aguirre AA. Evaluating the effectiveness of the stimulus pairing observation procedure and multiple exemplar instruction on tact and listener responses in children with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone VJ, Lewis L, Sweeney-Kerwin EJ, Dixon J, Louden R, Quinn S. A comparison of two approaches for teaching VB functions: Total communication vs. vocal-alone. The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;1(3):181–192. doi: 10.1037/h0100199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone VJ, Sweeney-Kerwin EJ, Attanasio V, Kasper T. Increasing the vocal responses of children with autism and developmental disabilities using manual sign mand training and prompt delay. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:705–709. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariveau T, Kodak T, Campbell V. The effects of intertrial interval and instructional format on skill acquisition and maintenance for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:809–825. doi: 10.1002/jaba.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnerero JJ, Pérez-González LA. Induction of naming after observing visual stimuli and their names in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35:2514–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnett A, Ingvarsson ET. Teaching a child with autism to mand for answers to questions using a speech-generating device. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:233–241. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RA, Klatt KP. Using stimulus-stimulus pairing and direct reinforcement to teach vocal verbal behavior to young children with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2008;24:135–146. doi: 10.1007/BF03393062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]