Abstract

Background

The anaemia seen in chronic kidney disease (CKD) may be exacerbated by iron deficiency. Iron can be provided through different routes, with advantages and drawbacks of each route. It remains unclear whether the potential harms and additional costs of intravenous (IV) compared with oral iron are justified. This is an update of a review first published in 2012.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of IV iron supplementation compared with oral iron for anaemia in adults and children with CKD, including participants on dialysis, with kidney transplants and CKD not requiring dialysis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 7 December 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs in which IV and oral routes of iron administration were compared in adults and children with CKD.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study eligibility, risk of bias, and extracted data. Results were reported as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes the mean difference (MD) was used or standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. Statistical analyses were performed using the random‐effects model. Subgroup analysis and univariate meta‐regression were performed to investigate between study differences. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using GRADE.

Main results

We included 39 studies (3852 participants), 11 of which were added in this update. A low risk of bias was attributed to 20 (51%) studies for sequence generation, 14 (36%) studies for allocation concealment, 22 (56%) studies for attrition bias and 20 (51%) for selective outcome reporting. All studies were at a high risk of performance bias. However, all studies were considered at low risk of detection bias because the primary outcome in all studies was laboratory‐based and unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

There is insufficient evidence to suggest that IV iron compared with oral iron makes any difference to death (all causes) (11 studies, 1952 participants: RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.64, 1.94) (absolute effect: 33 participants per 1000 with IV iron versus 31 per 1000 with oral iron), the number of participants needing to start dialysis (4 studies, 743 participants: RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.41, 1.61) or the number needing blood transfusions (5 studies, 774 participants: RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.55, 1.34) (absolute effect: 87 per 1,000 with IV iron versus 101 per 1,000 with oral iron). These analyses were assessed as having low certainty evidence. It is uncertain whether IV iron compared with oral iron reduces cardiovascular death because the certainty of this evidence was very low (3 studies, 206 participants: RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.41 to 7.18). Quality of life was reported in five studies with four reporting no difference between treatment groups and one reporting improvement in participants treated with IV iron.

IV iron compared with oral iron may increase the numbers of participants, who experience allergic reactions or hypotension (15 studies, 2607 participants: RR 3.56, 95% CI 1.88 to 6.74) (absolute harm: 24 per 1000 with IV iron versus 7 per 1000) but may reduce the number of participants with all gastrointestinal adverse effects (14 studies, 1986 participants: RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.66) (absolute benefit: 150 per 1000 with IV iron versus 319 per 1000). These analyses were assessed as having low certainty evidence.

IV iron compared with oral iron may increase the number of participants who achieve target haemoglobin (13 studies, 2206 participants: RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.04) (absolute benefit: 542 participants per 1,000 with IV iron versus 317 per 1000 with oral iron), increased haemoglobin (31 studies, 3373 participants: MD 0.72 g/dL, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.05); ferritin (33 studies, 3389 participants: MD 224.84 µg/L, 95% CI 165.85 to 283.83) and transferrin saturation (27 studies, 3089 participants: MD 7.69%, 95% CI 5.10 to 10.28), and may reduce the dose required of erythropoietin‐stimulating agents (ESAs) (11 studies, 522 participants: SMD ‐0.72, 95% CI ‐1.12 to ‐0.31) while making little or no difference to glomerular filtration rate (8 studies, 1052 participants: 0.83 mL/min, 95% CI ‐0.79 to 2.44). All analyses were assessed as having low certainty evidence. There were moderate to high degrees of heterogeneity in these analyses but in meta‐regression, definite reasons for this could not be determined.

Authors' conclusions

The included studies provide low certainty evidence that IV iron compared with oral iron increases haemoglobin, ferritin and transferrin levels in CKD participants, increases the number of participants who achieve target haemoglobin and reduces ESA requirements. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether IV iron compared with oral iron influences death (all causes), cardiovascular death and quality of life though most studies reported only short periods of follow‐up. Adverse effects were reported in only 50% of included studies. We therefore suggest that further studies that focus on patient‐centred outcomes with longer follow‐up periods are needed to determine if the use of IV iron is justified on the basis of reductions in ESA dose and cost, improvements in patient quality of life, and with few serious adverse effects.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Humans; Administration, Oral; ; /blood; /therapy; Blood Transfusion; Blood Transfusion/statistics & numerical data; Cause of Death; Ferritins; Ferritins/blood; Hemoglobin A; Hemoglobin A/metabolism; Injections, Intravenous; Iron Compounds; Iron Compounds/administration & dosage; Iron Compounds/adverse effects; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Kidney Failure, Chronic/blood; Kidney Failure, Chronic/complications; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Transferrin; Transferrin/metabolism

Plain language summary

Iron treatment for adults and children with reduced kidney function

What is the issue?

Anaemia (reduction in the number of circulating red blood cells) often occurs in people who have kidney damage, especially those who need dialysis treatment. Anaemia can cause tiredness, reduce exercise tolerance and increase heart size. A common cause of anaemia is reduced production of a hormone, erythropoietin. Iron deficiency can make anaemia worse, and reduce the response to medications that stimulate erythropoietin production. Iron can be taken orally (by mouth) or injected intravenously (via a vein). Intravenous (IV) iron is given under supervision in hospitals. There is uncertainty about whether IV iron should be used rather than oral iron.

What did we do?

We reviewed 39 studies (3852 participants) which compared IV iron supplements with oral iron in participants with chronic kidney disease.

What did we find?

We found that IV iron may increase blood levels of haemoglobin and iron compared with oral iron. However, IV iron may increase the number of allergic reactions though it may reduce side effects such as constipation, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting seen with oral iron. We did not find sufficient evidence to determine whether IV iron compared with oral iron improved quality of life, altered overall death rate or death due to heart disease.

Conclusions

Although the results suggest that IV iron compared with oral iron may be more effective in raising iron and haemoglobin levels, we found insufficient data to determine if the benefits of IV iron are justified by improved quality of life or mortality despite the small risk of potentially serious allergic effects in some patients given IV iron.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Patient‐centred outcomes for oral versus IV iron in adults and children with chronic kidney disease.

| Patient‐centred outcomes for oral versus IV iron in adults and children with CKD | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children with CKD Setting: Nephrology departments Intervention: IV iron Comparison: oral iron | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with oral iron | Risk with IV iron | |||||

| Death (all causes) | 30 per 1,000 | 33 per 1,000 (19 to 58) | RR 1.12 (0.64 to 1.94) | 1952 (11) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Only 11/38 studies represented with only about 1/3 of patients. |

| Cardiovascular death | 20 per 1,000 | 34 per 1,000 (8 to 142) | RR 1.71 (0.41 to 7.18) | 206 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 4 | ‐ |

| Type of adverse event: allergic reactions/hypotension | 7 per 1,000 | 24 per 1,000 (13 to 46) | RR 3.56 (1.88 to 6.74) | 2607 (15) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ‐ |

| Type of adverse event: all gastrointestinal adverse effects | 319 per 1,000 | 150 per 1,000 (105 to 211) | RR 0.47 (0.33 to 0.66) | 1986 (14) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | ‐ |

| Type of adverse event: infection | 80 per 1,000 | 106 per 1,000 (72 to 157) | RR 1.32 (0.90 to 1.95) | 954 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ‐ |

| Numbers of non‐dialysis patients needing to commence dialysis | 46 per 1,000 | 38 per 1,000 (19 to 75) | RR 0.81 (0.41 to 1.61) | 743 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ‐ |

| Number requiring transfusion | 101 per 1,000 | 87 per 1,000 (56 to 136) | RR 0.86 (0.55 to 1.34) | 774 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; IV: intravenous; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for imprecision

2 Downgraded one level for likely publication bias

3 Downgraded one level for high heterogeneity

4 Downgraded one level for publication bias

Summary of findings 2. Laboratory and pharmaceutical outcomes for adults and children with chronic kidney disease.

| Laboratory and pharmaceutical outcomes for adults and children with CKD | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children with CKD Setting: Nephrology departments Intervention: IV iron Comparison: oral iron | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with oral iron | Risk with IV iron | |||||

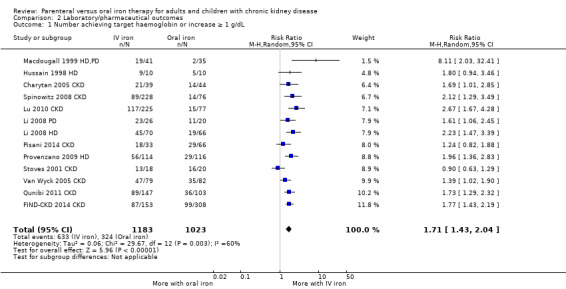

| Number achieving target Hb or increase ≥1 g/dL | 317 per 1,000 | 542 per 1,000 (453 to 646) | RR 1.71 (1.43 to 2.04) | 2206 (13) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Risk of bias (ROB) downgraded as little info on random sequence generation (RSG) and allocation concealment. Heterogeneity 60% |

| Hb: final or change (g/dL) | The mean Hb level was 0.72 g/dL higher with IV iron compared to oral iron (0.39 to 1.05 higher) | ‐ | 3373 (31) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | 21/31 are at ROB for RSG &/or allocation concealment. Heterogeneity 94% | |

| Ferritin: final or change (µg/L) | The mean ferritin level was 224.84 µg/L higher with IV iron compared to oral iron (165.85 to 283.83 higher) | ‐ | 3389 (33) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | 8/13 are at ROB for RSG or allocation concealment. Heterogeneity 60%. | |

| TSAT: final or change (%) | The mean TSAT was 7.69% higher with IV iron compared to oral iron (5.1 to 10.28 higher) | ‐ | 3089 (27) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | 11/27 only are at low risk of bias and heterogeneity is 97%. | |

| HCT (%) | The mean HCT was 1.18% higher with IV iron compared to oral iron (2.17 lower to 4.52 higher) | ‐ | 152 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 4 | Only 4 studies in this analysis, all with unknown risk of selection bias. Heterogeneity 96%. | |

| ESA dose: final or change | The SMD for ESA dose was 0.72 lower with IV iron compared to oral iron (0.31 to 1.12 lower) | ‐ | 522 (11) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ROB downgraded as little information on RSG and Allocation concealment. Heterogeneity 77% | |

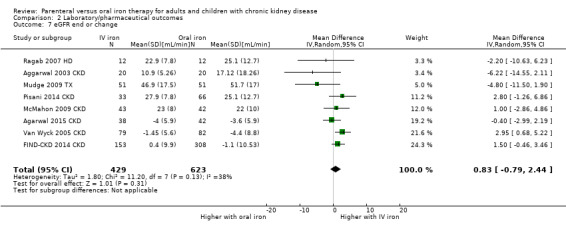

| eGFR: final or change (mL/min) | the mean eGFR was 0.83 mL/min higher with IV iron compared to oral iron (0.79 lower to 2.44 higher) | ‐ | 1052 (8) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | Half of the studies are at ROB for RSG & allocation concealment. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESA: erythrocyte‐stimulating agent; Hb: haemoglobin; HCT: haematocrit; IV: intravenous; RR: Risk ratio; TSAT: transferrin saturation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for risk of bias

2 Downgraded one level for inconsistency

3 Downgraded one level for imprecision

4 Downgraded one level for likely publication bias

Background

Description of the condition

A reduction in the number of circulating red blood cells is termed anaemia. The prevalence of anaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is twice that in the general population. As kidney function deteriorates, the prevalence of anaemia increases from 8.4% at CKD stage 1 to 53.4% at CKD stage 5 (Stauffer 2014). The cause of anaemia in CKD is multifactorial though largely driven by decreased kidney production of erythropoietin. Iron deficiency can exacerbate the degree of anaemia and reduce the response to erythropoietin‐stimulating agents (ESAs). Anaemia has been found to contribute to a number of pathological processes. Observational studies have shown anaemia to be associated with increased mortality (at an haemoglobin level (Hb) < 11.0 g/dL) (Kovesdy 2006; Levin 2006), increased hospital stay (Li 2004), increased cardiovascular events (Li 2004; Vlagopoulos 2005; Weiner 2005) and decreased quality of life (Fukuhara 2007). Limited data have also shown that an increase in Hb can improve a number of these indices (Levin 2006; Moreno 2000). However, a systematic review of studies assessing the effects of targeting higher Hb concentrations in patients with CKD by using higher doses of ESA showed a significantly higher risk of death (all causes) (risk ratio (RR) 1.17) and arteriovenous access thrombosis (RR 1.34) in the higher Hb target group compared with the lower Hb group (Phrommintikul 2007). National (CARI 2008; Moist 2008; NICE 2015) and international guidelines (KDIGO 2008; Locatelli 2010) recommend target Hb levels of between 10 g/dL to 12 g/dL for patients with CKD. The most recent guidelines (KDIGO 2012) suggest that the Hb in adult CKD patients should not exceed 11.5 g/dL.

Iron is an essential mineral to maintain health. It is required in many intracellular processes including DNA synthesis, mitochondrial energy generation and enzymatic reactions. It is used in the production of myoglobin in muscles and Hb, the oxygen carrying component of the red blood cells. Determining iron deficiency in CKD can be challenging as it is often a functional deficiency caused by insufficient iron availability despite adequate body iron stores. The aetiology of iron deficiency in CKD is complex but includes reduced dietary intake and blood loss, particularly from the gastrointestinal tract, due to uraemia induced platelet dysfunction (Hedges 2007). These losses are compounded in patients on haemodialysis (HD) by the use of heparin, losses from clotted dialysis lines and blood sampling, which can lead to losses of 2 litres to 5 litres of blood per year (Sargent 2004). Lastly, chronic inflammation and uraemia result in an upregulation and reduced clearance of hepcidin, inhibiting the release of iron from macrophages and decreasing gastrointestinal iron absorption (Lopez 2015).

Description of the intervention

Therapeutic iron can be given orally. Four iron preparations are commonly used: ferrous sulphate, ferrous sulphate exsiccated, ferrous gluconate, and ferrous fumarate. It can be given intramuscularly in the form of iron dextran or it can be given intravenously. Six main forms of intravenous (IV) iron are currently available: iron sucrose, ferric gluconate, ferric carboxymaltose, iron isomaltoside‐1000, ferumoxytol, and iron dextran (low‐molecular‐weight forms) (Lopez 2015).

Oral iron frequently causes gastrointestinal side effects including heartburn, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and constipation (Lopez 2015). These events affect patient compliance and can limit total intake. Although serious adverse events related to IV forms of iron are rare, the effects can be life threatening and include pulmonary embolism, anaphylactic reaction, loss of consciousness, circulatory collapse, hypotension, dyspnoea, pruritus, hypersensitivity and urticaria (Bailie 2012; Lopez 2015). The cumulative rate for all adverse events, for all IV iron preparations, is 14.1 adverse events per million units sold though it appears to be higher in products such as ferumoxytol compared with iron sucrose (Bailie 2012). IV iron preparations require administration under supervision and this need increases the cost of administration and is inconvenient for patients who are not receiving in‐centre HD. IV iron has also been linked to an increased risk of infection and cardiovascular disease; iron can act as a growth factor for some bacteria and free iron has been shown to impair neutrophil and T cell function as well as increase reactive oxygen species (Fishbane 2014; Ishida 2014). The majority of the literature to date supports these associations although the most recent cohort study of nearly 23,000 HD patients suggested no difference in length of stay, death or readmission for infection in those who received IV iron during admission and those who did not (Ishida 2015). Furthermore there is increasing evidence that free iron plays a role in direct injury to kidney tissue, which could result in more rapid deterioration in kidney function (Shah 2011).

Controversies remain about the most effective and safe way to provide iron supplementation in patients with CKD (Fishbane 2007; Macdougall 2016). Current parameters used to monitor iron status include serum ferritin levels, serum iron, transferrin saturation (TSAT), per cent of hypochromic red blood cells, and reticulocyte Hb content. There is debate about the most valuable measures to assess iron status, and the setting of optimum levels of these measures in patients with CKD to increase Hb and optimise ESA response. Novel markers being developed but not yet in routine use include hepcidin, soluble transferrin receptor one and non‐transferrin bound iron (Gaweda 2015).

How the intervention might work

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anaemia in CKD and of hypo‐responsiveness to ESAs (Kwack 2006). ESAs accelerate erythropoiesis by increasing iron utilisation and depleting iron stores. Optimal efficacy of ESAs depends on the availability of iron to achieve and maintain target Hb levels. Patients with CKD stage 5D require higher targets for ferritin and TSAT levels to achieve increased Hb levels compared with patients whose kidney function is normal. Two studies targeting ferritin levels of 400 ng/mL or 30% to 50% TSAT resulted in significant reductions in the ESA dose required to maintain Hb levels compared with targeting a ferritin level of 200 ng/mL or TSAT levels of 20% to 30% (Besarab 2000; DeVita 2003). However, such high ferritin and TSAT levels increase the risk of iron overload and its associated complications. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines (KDOQI 2007), the Canadian (Madore 2008) and the European guidelines (Locatelli 2009) recommend serum ferritin of > 200 ng/mL and TSAT > 20% in patients receiving HD. KDIGO 2012 recommend that iron can be given until TSAT > 30% or serum ferritin > 500 ng/mL. In patients with less severe degrees of CKD, serum ferritin levels > 100 ng/mL and TSAT > 20% are recommended.

Why it is important to do this review

The original study published in 2012 found strong evidence for increased ferritin and TSAT levels and a small increase in Hb with IV iron compared with oral iron. There was limited evidence that this came with a reduction in ESA use. Only half of the studies reported on adverse events. There have been several studies done over the last six years which have looked at the adverse event rate of the many preparations of IV iron and also included hard end points including all cause and cardiovascular death. At present the majority of HD patients receive IV iron and the use of IV iron in the peritoneal dialysis (PD) and CKD populations is increasing. We felt it was important to update this review to ensure that patient focused adverse events were analysed as well as providing up to date evidence on the efficacy and safety of IV iron. In this review, we aimed to explore all possible causes of heterogeneity of study results in detail by subgroup analysis and to further investigate the effects of IV iron in patients with CKD who were not on dialysis.

Objectives

Our objective was to determine the benefits and harms of IV iron supplementation compared with oral iron for anaemia in patients with CKD, treated with HD, PD, not receiving dialysis and post transplant. The review aimed to examine the effects of these interventions on patient centred outcomes including death, requirements for transfusion, hospitalisation, cardiac function, quality of life and change in eGFR as well as iron parameters, achieving target levels of Hb, reducing doses of ESA required, and to determine adverse effects of the therapies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (studies in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) in which oral and IV routes of administration of iron were compared in patients with CKD.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included adult and paediatric patients with CKD (stages 3 to 5D; glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Studies in patients receiving HD, PD, or those not requiring dialysis, were included. Studies of kidney transplant patients were also included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies of iron administration in patients comparing different IV or oral iron preparations and different doses of the same IV or oral preparation were excluded. Studies in patients with acute kidney injury were excluded.

Types of interventions

We examined different IV iron supplements (including iron sucrose, dextran, ferric gluconate, ferric carboxymaltose, ferumoxytol) and oral iron preparations (including oral iron preparations which contain folic acid, vitamin C or both).

We included studies using different doses and durations of IV iron compared with oral iron preparations provided that the control group received oral iron supplements only.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death (all causes)

Cardiovascular death

Quality of life

Secondary outcomes

-

Hb

Number achieving target Hb level

Time to achieve target Hb

Final or change in Hb at end of study

Increase in Hb > 10 g/L or other target during study

-

Iron

Number achieving target levels of iron (ferritin, TSAT, per cent of hypochromic red blood cells)

Final or change in ferritin levels at the end of study

Final or change in TSAT at end of study

Per cent of hypochromic red blood cells

-

Erythrocyte stimulating agents (ESAs)

Reduction in required dose of ESA

Number needing to increase ESA dose

Number needing to decrease ESA dose or cease ESA

Infection

Change in GFR in non‐dialysis patients

Number needing transfusions

-

Any adverse events of treatment

Adverse effects of oral iron

Adverse effects of IV iron supplements including hypersensitivity reactions

Number of patients needing to cease oral or IV supplements because of adverse effects

Other outcomes

Haematocrit (HCT)

Reticulocyte Hb concentration

Numbers of non‐dialysis patients needing to commence dialysis

Hospitalisation (other than for iron infusions and dialysis)

Exercise tolerance

Left ventricular function

Sexual function

Nutritional status

Adherence to therapy

Numbers and costs of hospitalisations/professional supervision required for IV iron supplements

Iron overload (as defined by the triallists)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 7 December 2018 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that were potentially relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. However, studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and where necessary the full text, of these studies to determine which satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias were performed independently by the same authors using standardised data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, the publication with the most complete data was reviewed initially. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted. Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (number reaching target Hb, death) results were expressed as RR with 95% confidence intervals (CI). RR with 95% CI were calculated for adverse effects. Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (Hb level, iron parameters) the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used (end of study ESA dose). Either final levels or change in levels were included in meta‐analyses of continuous scales of measurement. When both measures are provided in a study, final levels were included.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over studies were thought likely to be inappropriate means of examining IV and oral iron because of carry over effects related to achieved Hb levels and iron parameters. Therefore, only data from the first period of cross‐over studies were included where these were reported separately, and included all or most patients who completed the first period, rather than only those who completed both treatment periods.

Dealing with missing data

Where necessary, we contacted triallists to request missing patient data due to loss to follow‐up and exclusion from study analyses in an effort to conduct intention‐to‐treat analyses. Eight authors responded to our requests. Where missing dichotomous or continuous data were few, and unlikely to affect the overall results, we analysed available data. Where possible we imputed missing standard deviations and standard errors if data was presented alternatively, using methods stated in the Cochrane handbook (Higgins 2011a).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Register includes studies obtained from searching major databases, conference proceedings and prospective trial registers without language restriction in an attempt to reduce publication bias related to failure of authors to publish negative results or their inability to publish negative results in journals indexed in major databases. When sufficient studies were available, we created funnel plots and calculated Eggers' test to assess publication bias. Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were included from the most recent publication, and preferably, the definitive publication. However, all publications were reviewed to identify outcomes not reported in the index publication in an attempt to reduce outcome reporting bias.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model for dichotomous and continuous data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

To explore clinical differences among studies that could influence the magnitude of the treatment effect for the outcomes of differences in ferritin, TSAT and Hb, subgroup analyses and univariate meta‐regression were performed using STATA software (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA) using restricted maximum‐likelihood to estimate between study variance. The potential sources of variability were defined a priori and were related to study rationale (CKD stage, whether aiming to increase or maintain Hb, concurrent use of erythropoietin co‐intervention, timing of initiation of erythropoietin co‐intervention), dose delivered and duration of IV and oral iron therapy, and study sponsorship. Where subgroup analysis findings suggested that more than one factor could influence the magnitude of observed differences, we planned to conduct multivariate meta‐regression.

Underlying cause of end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD), baseline iron status, and previous iron therapy were not examined in subgroup analyses because most studies did not provide this information. All studies, except two paediatric studies, included adults of similar ages so different age groups could not be examined in subgroup analyses. Only one study (Li 2008 PD) included solely PD patients so it was not possible to examine different types of renal replacement therapy in subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test decisions where inclusion of a study, with a much higher MD in Hb, might have altered meta‐analysis results.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

-

Death (all causes)

Cardiovascular death

Allergic reactions/hypotension

All gastrointestinal adverse effects

Infection

Numbers of non‐dialysis patients needing to commence dialysis

Number requiring transfusion

-

Number achieving target Hb or increase ≥1 g/dL

Hb: final or change

Ferritin: final or change

TSAT: final or change

HCT

End of treatment or change in ESA dose

eGFR end or change

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The initial study resulted in a total of 522 study reports from the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to March 2010, CENTRAL (in The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2010), MEDLINE (to October week 5, 2008) and EMBASE (to week 45, 2008). From these 522 reports, 28 studies (46 reports) were included in the systematic review while 28 studies were excluded; there were three ongoing studies.

For the 2019 update of this review, a search of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register identified 49 new reports. From these we identified 11 new included studies (31 reports) (Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Mudge 2009 TX; Nagaraju 2013 CKD; NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD; Ragab 2007 HD; Tsuchida 2010 HD; Winney 1977 HD), three new excluded studies (4 reports) and 14 additional reports of previously included studies.. The additional reports included the full publication of Qunibi 2011 CKD. Of the 11 new included studies, four were publications of trials identified as ongoing trials in the 2010 review (Agarwal 2015 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Mudge 2009 TX; NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD). The paediatric study (NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD) was terminated because of challenges with enrolment with minimal data reported. Search results are shown in Figure 1. One new report contained further information on two already included studies (Li 2008 HD; Li 2008 PD). Spinowitz 2008 CKD included all nine reports, which included data for one new included study (Lu 2010 CKD). This 2019 update contains 44 studies (101 reports).

1.

Flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review

Included studies

The 11 new included studies (31 reports) provided an additional 1754 participants bringing the total to 3852 participants. Of the new studies, seven included 1653 participants with CKD, three included 75 participants on HD and one included 102 transplant patients. One study included both dialysis and non‐dialysis patients but did not specify how many patients were in each group.

Of the 39 included studies, 38 (3832 participants) were parallel group studies, and one (20 patients) was a cross‐over study (Strickland 1977 HD). Only three studies involved paediatric patients (NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD; Ragab 2007 HD; Warady 2002 HD). Nineteen studies included only HD patients. Li 2008 PD included only patients on PD while Macdougall 1999 HD,PD included both HD and PD patients. Two studies (Ahsan 1997 TX; Mudge 2009 TX) evaluated patients who were in the early phase of post‐kidney transplantation. Results from these studies were pooled with studies of dialysis patients. Thirteen studies included non‐dialysis patients (CKD stages 3 to 5) while two studies (Macdougall 1996 HD,PD,CKD; NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD) included both dialysis and non‐dialysis patients. Twelve studies were available only as abstracts or from ClinicalTrials.Gov (Ahsan 1997 TX; Broumand 1998 HD; Erten 1998 HD; Leehey 2005 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Lye 2000 HD; Macdougall 1999 HD,PD; Michael 2007 HD; NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD; Souza 1997 HD; Wang 2003 HD; Winney 1977 HD). Thirty‐two studies were designed to increase Hb levels and four studies were designed to maintain Hb stability in iron replete patients and decrease ESA dose (Fishbane 1995 HD; Kotaki 1997 HD; Michael 2007 HD; Warady 2002 HD). One study was designed to examine changes in GFR during (Agarwal 2015 CKD) while one study was designed to determine the time to the start of additional anaemia management other than iron (FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD).

The duration of follow‐up ranged from 35 days to 26 months.

Studies compared different oral and IV iron preparations. The oral iron agents investigated were ferrous sulphate (25 studies), ferrous fumarate (7), ferrous succinate (2), iron gluconate (1), liposomal iron (1), heme iron polypeptide (1) and unnamed agents in two studies. The IV iron agents investigated were iron sucrose (15 studies), iron dextran (7), ferumoxytol (4), sodium ferric gluconate complex (5), ferric carboxymaltose (2), iron isomaltoside (1), ferric citrate (1), and ferric hydroxide polymaltose (3). The IV iron agent was not reported in Kotaki 1997 HD. The calculated total dose of elemental iron ranged from 2520 mg to 63,000 mg in the oral iron groups and from 500 to 10,920 mg in the IV iron groups. Three studies (Erten 1998 HD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD) included two IV iron treatment groups. For these studies, data from patients who received the higher total dose of IV iron were included in the meta‐analyses.

In twenty‐two studies all participants were treated with an ESA. ESA therapy was started at study commencement in six studies (Aggarwal 2003 CKD; Charytan 2005 CKD; Hussain 1998 HD; Lye 2000 HD; Macdougall 1996 HD,PD,CKD; Stoves 2001 CKD) and before study commencement in 15 studies (Broumand 1998 HD; Erten 1998 HD; Fishbane 1995 HD; Kotaki 1997 HD; Leehey 2005 CKD; Li 2008 HD; Li 2008 PD; Macdougall 1999 HD,PD; Michael 2007 HD; Mudge 2009 TX; Provenzano 2009 HD; Ragab 2007 HD; Svara 1996 HD; Tsuchida 2010 HD; Warady 2002 HD). It was unclear when ESA treatment was commenced in Wang 2003 HD. Seven studies reported that no included patients received ESA treatment (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Ahsan 1997 TX; Fudin 1998 HD; Kalra 2016 CKD; McMahon 2009 CKD; Strickland 1977 HD; Winney 1977 HD), but nine studies indicated that varying proportions of patients received an ESA (Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Nagaraju 2013 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD; Qunibi 2011 CKD; Spinowitz 2008 CKD; Souza 1997 HD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD).

The outcomes reported in 38 studies are presented in Figure 1. One study was terminated and did not provide any outcomes (NCT01155375 HD,PD,CKD). Final and/or change in Hb, serum ferritin and TSAT levels were reported in 31, 33 and 27 studies respectively. Four studies reported final HCT levels but not Hb levels (Ahsan 1997 TX; Fishbane 1995 HD; Kotaki 1997 HD; Svara 1996 HD). Only 11 studies reported death (all causes) (Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Fishbane 1995 HD; Fudin 1998 HD; Kalra 2016 CKD; McMahon 2009 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Provenzano 2009 HD; Qunibi 2011 CKD; Stoves 2001 CKD; Tsuchida 2010 HD) while three studies reported on cardiovascular events including death (Agarwal 2015 CKD; Fudin 1998 HD; Stoves 2001 CKD). Five studies reported on quality of life assessment (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD). Eighteen studies reported on adverse events (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Agarwal 2015 CKD; Charytan 2005 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Fishbane 1995 HD; Hussain 1998 HD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Li 2008 HD; Li 2008 PD; Nagaraju 2013 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD; Provenzano 2009 HD; Qunibi 2011 CKD; Spinowitz 2008 CKD; Strickland 1977 HD; Tsuchida 2010 HD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD).

Excluded studies

From the 2012 review, twenty‐three reports were excluded based on titles and abstracts; one study was not an RCT and the remainder involved ineligible interventions. Five more studies (eight reports) were excluded after full text review because participants were not randomised or compared intramuscular with oral iron.

Three studies (four reports) identified in the search for the 2019 update were excluded. One study (Charytan 2013) involved an ineligible comparator (standard medical care which could be oral or IV iron), one study (HEMATOCRIT 2012) compared two oral iron preparations and one study (Adhikary 2011) included non‐randomised patients.

Risk of bias in included studies

The assessment of risk of bias is shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Figure 2 shows relative proportional rankings of studies for each risk of bias indicator. Figure 3 shows the risk of bias items for individual studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation was at low risk of bias in 20 studies (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Fudin 1998 HD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Leehey 2005 CKD; Li 2008 HD; Li 2008 PD; Macdougall 1996 HD,PD,CKD; McMahon 2009 CKD; Mudge 2009 TX; Nagaraju 2013 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD; Qunibi 2011 CKD; Spinowitz 2008 CKD; Stoves 2001 CKD; Strickland 1977 HD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD; Warady 2002 HD). Random sequence generation was not reported in 18 studies.

Allocation concealment was at low risk of bias in 14 studies (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Leehey 2005 CKD; Macdougall 1996 HD,PD,CKD; Mudge 2009 TX; Nagaraju 2013 CKD; Lu 2010 CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD; Provenzano 2009 HD; Qunibi 2011 CKD; Spinowitz 2008 CKD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD); at high risk of bias in two studies (Fudin 1998 HD; Lye 2000 HD), and for the remaining 23 studies allocation concealment was unclear.

Blinding

No studies blinded either participants or personnel so were considered to be at high risk of bias. As all studies used laboratory data as primary outcomes, all studies were judged as having a low risk of bias for outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcomes data reporting was considered to be complete with a low risk of bias in 22 studies. Five studies (Charytan 2005 CKD; Fishbane 1995 HD; Fudin 1998 HD; Stoves 2001 CKD; Strickland 1977 HD) reported that from 7% to 36% of patients were excluded from the analyses, so were considered to be at high risk of bias. The risk of bias was unclear in 12 studies because there was insufficient information provided to determine if data from all patients who entered the study were included in the analysis.

Selective reporting

We identified 20 studies that were considered to have reported all outcomes based on the detailed protocols described in the trial methods. Eight studies (Agarwal 2015 CKD; Aggarwal 2003 CKD; Broumand 1998 HD; Charytan 2005 CKD; Leehey 2005 CKD; Ragab 2007 HD; Stoves 2001 CKD; Strickland 1977 HD) reported outcomes incompletely so that either outcomes could not be included in meta‐analyses or included only with imputed standard deviations or as incidence rates. It was unclear if outcomes were selectively reported in 11 studies.

Other potential sources of bias

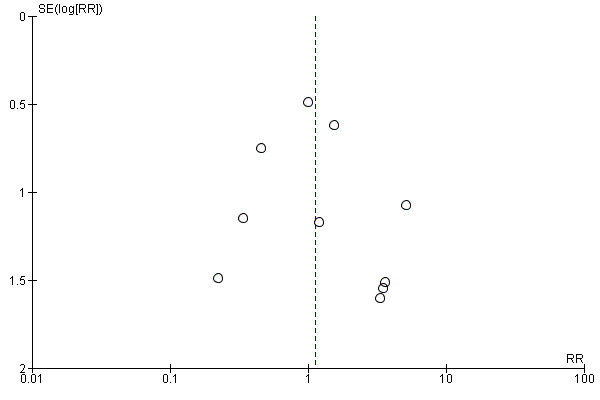

Sixteen studies reported receiving monetary support from pharmaceutical companies; three studies reported funding from non‐pharmaceutical company sources and the remainder did not report on how their study was funded. In funnel plots, patient centred outcomes showed funnel plot symmetry (example provided in Figure 4), suggesting a low likelihood of publication and other biases. However, for biochemical outcomes, there was some funnel plot asymmetry (example provided in Figure 5) which suggests that the meta‐analyses of these outcomes may be affected by some bias.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Patient‐centred outcomes.Outcome: 1.1 Death (all causes)

Eggers test P = 0.25

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, outcome: 2.4 Transferrin saturation: Final or change [%].

Eggers test P = 0.00

Effects of interventions

Effects of IV iron compared with oral iron on patient‐centred outcomes

Death (all causes) was only reported in 11 studies. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether IV iron compared with oral iron may makes any difference to death (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1 (11 studies, 1952 participants): RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.94; I2 = 0%). The absolute risk was 33 per 1000 with IV iron compared with 30 per 1000 with oral iron.

Cardiovascular death was reported in only three studies. It is uncertain whether IV iron compared with oral iron reduces cardiovascular death because the certainty of this evidence was very low (Analysis 1.2 (3 studies, 206 participants): RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.41 to 7.18; I2 = 0%).

Quality of life was only reported in five studies (Agarwal 2006 CKD; Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD). Agarwal 2006 CKD reported that the SF12 physical composite score improved by 4.8% in patients treated with IV iron, but there was no change in patients treated with oral iron. Kidney disease quality of life score (KDQOL) items ‐ improvement in the ability to do moderate activities and undertake work; and satisfaction with sex life ‐ were reported to be improved among patients treated with IV iron. Scores for a number of factors, including feelings of imposing a burden on family, were lower in patients who received IV iron. In contrast, Van Wyck 2005 CKD found no differences between treatment groups when health concept categories in the SF36 instrument were applied. Agarwal 2015 CKD reported no difference between groups or over time using the KDQOL. FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD reported no difference between groups using the SF‐36 tool. Using the Linear Analogue Scale Assessment score, Kalra 2016 CKD identified an improvement in quality of life from baseline to eight weeks in both treatment groups with no difference between groups (Analysis 1.3 (1 study, 312 participants): MD 1.45, 95% CI ‐5.89 to 8.79).

IV iron compared with oral iron may make little or no difference to the number of participants needing to start dialysis (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.4 (4 studies, 743 participants): RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.61; I2 = 0%). The absolute risk for starting dialysis was 38 per 1000 with IV iron and 46 per 1000 with oral iron.

IV iron compared with oral iron may make little or no difference to the need for transfusion (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.5 (5 studies, 774 participants): RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.34; I2 = 0%). The absolute risk for needing transfusion was 87 per 1000 with IV iron and 101 with oral iron.

Although nine studies reported that patient adherence to oral iron was assessed, only three provided numerical data (Charytan 2005 CKD; Van Wyck 2005 CKD; Pisani 2014 CKD). Mean adherence rates for IV iron therapy were 95%, 97% and 96% respectively, and adherence to oral iron therapy was 85% and 88% and 95.8%.

The certainty of the evidence was downgraded because of imprecision, heterogeneity between studies and publication bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 1 Death (all causes).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 2 Cardiovascular death.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 3 Quality of life.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 4 Number of non‐dialysis patients needing to commence dialysis.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 5 Number requiring transfusion.

See Table 1.

Effect of IV iron compared with oral iron on laboratory outcomes

The numbers of patients reaching target Hb or increasing Hb by at least 1 g/dL were reported in 13 studies. Target Hb or an increase in Hb by 1 g/dL may be achieved by more participants receiving IV iron compared with oral iron (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.1 (13 studies, 2206 participants): RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.04; I2 = 60%) in all patients (Table 2) and in the subgroups of dialysis participants and CKD participants (Table 3). There was low to moderate heterogeneity. The absolute benefit for reaching the target Hb was 542 per 1000 for IV iron and 317 per 1000 for oral iron.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 1 Number achieving target haemoglobin or increase ≥ 1 g/dL.

1. Laboratory outcomes in dialysis and chronic kidney disease participants.

| Outcome | Population | Studies | Participants | MD | RR | 95% CI |

| Hb (g/dL) | All studies | 31 | 3373 | 0.72 | ‐ | 0.39 to 1.05 |

| Dialysis | 17 | 917 | 1.01 | ‐ | 0.26 to 1.77 | |

| CKD | 14 | 2456 | 0.41 | ‐ | 0.28 to 0.55 | |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | All studies | 33 | 3389 | 224.8 | ‐ | 165.8 to 283.8 |

| Dialysis | 19 | 1027 | 233.7 | ‐ | 163.4 to 303.9 | |

| CKD | 14 | 2362 | 213.1 | ‐ | 123.7 to 302.6 | |

| TSAT (%) | All studies | 27 | 3089 | 7.69 | ‐ | 5.10 to 10.28 |

| Dialysis | 14 | 781 | 10.55 | ‐ | 3.89 to 17.22 | |

| CKD | 13 | 2308 | 5.32 | ‐ | 2.67 to 7.97 | |

| Achieving target Hb | All studies | 13 | 2206 | ‐ | 1.71 | 1.43 to 2.04 |

| Dialysis | 5 | 508 | ‐ | 2.01 | 1.52 to 2.66 | |

| CKD | 8 | 1698 | ‐ | 1.59 | 1.27 to 1.97 |

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; Hb ‐ haemoglobin; TSAT ‐ transferrin saturation

End of study or change (g/dL) in Hb were reported in 31 studies. IV iron compared with oral iron may increase Hb (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.2 (31 studies, 3373 participants): MD 0.72 g/dL, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.05); I2 = 94%) in all participants and in subgroups of dialysis and CKD participants (Table 3). There was a high levels of heterogeneity, which persisted when a fixed‐effect model was used for analyses. Excluding a study of 26 months treatment and MD 4.92 g/dL (Fudin 1998 HD) did not significantly reduce heterogeneity. Further analyses of heterogeneity are addressed in later sections.

End of study or change (μg/L) in serum ferritin levels were reported in 33 studies. IV iron compared with oral iron may increase ferritin levels (low certainty evidence) in all participants (Analysis 2.3 (33 studies, 3389 participants): MD 224.84 µg/L, 95% CI 165.85 to 283.83, I2 = 99%) and in subgroups of dialysis and CKD participants (Table 3). There was a high level of heterogeneity in these analyses.

End of study or change (%) in TSAT levels were reported in 27 studies. IV iron compared with oral iron may increase TSAT levels (low certainty evidence) in all participants (Analysis 2.4 (27 studies, 3089 participants): MD 7.69 %, 95% CI 5.10 to 10.28, I2 = 97%) and in subgroups of dialysis and CKD participants (Table 3). There was a high level of heterogeneity in these analyses.

Five studies reported results for HCT rather than Hb. It is uncertain whether IV iron improves HCT because the certainty of this evidence was very low (Analysis 2.5.1 (5 studies, 180 participants): MD 1.09%, 95% CI ‐2.19 to 4.37, I2 = 96%). There was a high level of heterogeneity in this analysis.

Eleven studies reported end of study or change in ESA dose. IV iron probably leads to a reduction in ESA dose compared with oral iron (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.6 (11 studies, 522 participants): SMD ‐0.72, 95% CI ‐1.12 to ‐0.31) with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 77%).

IV iron compared with oral iron may make little or no difference to eGFR at the end of study (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.7 (8 studies,1052 participants): MD 0.83 mL/min, 95% CI ‐0.79 to 2.44). There was low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 38%).

The certainty of the evidence was downgraded because of high risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision and possible publication bias.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 2 Haemoglobin: final or change (all patients).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 3 Ferritin: final or change (all patients).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 4 Transferrin saturation: final or change.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 5 Haematocrit.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 6 End of treatment or change in ESA dose.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Laboratory/pharmaceutical outcomes, Outcome 7 eGFR end or change.

See Table 2.

Adverse effects

18 studies provided some information on adverse effects of therapy.

IV iron compared with oral iron may increase the numbers of participants, who experience allergic reactions or hypotension (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.6.1 (15 studies, 2607 participants): RR 3.56, 95% CI 1.88 to 6.74; I2 = 0%). The absolute risk for allergic reactions/hypotension was 24 per 1000 with IV iron and 7 per 1000 with oral iron.

Only four studies reported data on infection. The most commonly reported infections were respiratory and urinary tract infections. IV iron compared with oral iron may make little or no difference to the risk of infection (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.6.2 (4 studies, 954 participants): RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.95; I2 = 2%).

IV iron compared with oral iron may be associated with fewer participants with all gastrointestinal adverse effects (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.6.3 (14 studies, 1986 participants): RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.66; I2 = 63%), fewer participants with constipation (Analysis 1.6.4 (10 studies, 1618 participants): RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.57; I2 = 19%) and possibly with diarrhoea (Analysis 1.6.5 (10 studies, 1625 participants): RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.05; I2 = 0%). The absolute risk of all gastrointestinal adverse effects was 150 per 1000 with IV iron and 319 per 1000 with oral iron.

Only three studies reported data on iron overload. Each of these studies defined iron overload as ferritin levels > 800 ng/mL. IV iron compared with oral iron may make little or no difference to the risk of iron overload (low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.6.8 (3 studies, 158 participants): RR 6.58, 95% CI 0.81 to 53.51; I2 = 0%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Patient centred outcomes, Outcome 6 Type of adverse event.

See Table 1.

Exploration of heterogeneity using subgroup analyses: effect of different doses of IV or oral iron on haemoglobin, ferritin and TSAT

Subgroup analysis using testing for interaction was applied to investigate the effects of different total doses of IV iron (≤ 1000 mg, 1000 to 2000 mg, > 2000 mg), different doses/month of IV iron (≤ 400 mg/month, > 400 to 700 mg/month, > 700 mg/month), different total doses of oral iron (< 12,000 mg, 12,000 to 30,000 mg, > 30,000 mg), and different doses/month of oral iron (< 4000 mg/month, 4000 to <6000 mg/month, ≥ 6000 mg/month) on levels of Hb, ferritin and TSAT. These values were chosen based on tertiles of doses investigated in the included studies. Results for the outcomes of Hb, ferritin and TSAT are shown as SMD in Table 4; Table 5 and Table 6 respectively.

2. Subgroup analysis and meta‐regression to examine heterogeneity in haemoglobin meta‐analyses.

| Total studies (N) | Studies | SMD (95% CI) | P | |

| Dose IV iron/study month | ||||

| ≥ 400 mg/month | 12 | 8 | 0.17 (‐0.18 to 0.52) | 0.12 |

| > 400 to 700 mg/month | 7 | 6 | 0.76 (0.29 to 1.24) | ‐ |

| > 700 mg/month | 9 | 8 | 0.74 (0.41 to 1.06) | ‐ |

| Dose IV iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≤ 1000 mg | 11 | 8 | 0.46 (0.25 to 0.66) | 0.21 |

| 1000 to 1999 mg | 12 | 10 | 0.48 (0.11 to 0.84) | ‐ |

| > 2000 mg | 5 | 4 | 0.89 (0.04 to 1.73) | ‐ |

| Oral dose iron/study month | ||||

| < 4000 mg/month | 12 | 10 | 0.87 (0.37 to 1.38) | 0.15 |

| ≥ 4000 and < 6000 mg/month | 12 | 11 | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.64) | ‐ |

| ≥ 6000 mg/month | 7 | 5 | 0.37 (0.16 to 0.59) | ‐ |

| Dose oral iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≥ 12,000 mg | 13 | 12 | 0.60 (0.38 to 0.82) | 0.86 |

| 1200 to 30,000 mg | 10 | 8 | 0.66 (0.29 to 1.03) | ‐ |

| > 30,000 mg | 18 | 11 | 0.45 (‐0.05 to 0.94) | ‐ |

| Any ESA use | ||||

| No EPO | 8 | 6 | 0.57 (0.05 to 1.08) | 0.34 |

| EPO | 27 | 22 | 0.55 (0.32 to 0.78) | ‐ |

| ESA timing of use | ||||

| Start of study | 8 | 7 | 0.40 (0.08 to 0.72) | 0.90 |

| Before study | 19 | 15 | 0.57 (0.28 to 0.85) | ‐ |

| CKD stage | ||||

| 1 to 5 | 15 | 14 | 0.37 (0.26 to 0.50) | 0.10 |

| Dialysis (5D) | 22 | 16 | 0.80 (0.37 to 1.24) | ‐ |

| Study duration | ||||

| ≥ 2 months | 14 | 12 | 0.55 (0.35 to 0.75) | 0.81 |

| > 2 to ≤ 4 months | 9 | 7 | 0.74 (0.28 to 1.19) | ‐ |

| > 4 months | 14 | 11 | 0.46 (0.002 to 0.91) | ‐ |

| Intervention aim | ||||

| Increase Hb | 24 | 20 | 1.00 (0.51 to 1.50) | 0.18 |

| Maintain Hb | 4 | 2 | ‐0.09 (‐0.53 to 0.36) | ‐ |

| Pharmaceutical company sponsorship | ||||

| Unclear | 23 | 18 | 0.81 (0.40 to 1.23) | 0.08 |

| Sponsored | 15 | 13 | 0.38 (0.28 to 0.48) | ‐ |

| Imputed SD | ||||

| Not imputed | ‐ | 5 | 0.42 (0.02 to 0.81) | 0.52 |

| Imputed | ‐ | 26 | 0.55 (0.35 to 0.76) | ‐ |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; EPO ‐ erythropoietin; ESA: erythropoiesis‐stimulating agent; Hb: haemoglobin; SD: standard deviation

3. Subgroup analysis and meta‐regression to examine heterogeneity in ferritin meta‐analyses .

| Total studies (N) | Studies | SMD (95% CI) | P | |

| Dose IV iron/study month | ||||

| ≥ 400 mg/month | 12 | 8 | 1.59 (0.73 to 2.44) | 0.02 |

| > 400 to 700 mg/month | 7 | 6 | 1.62 (1.41 to 1.83) | ‐ |

| >700 mg/month | 9 | 9 | 1.32 (0.85 to 1.78) | ‐ |

| Dose IV iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≥ 1000 mg | 11 | 9 | 1.67 (1.03 to 2.30) | 0.08 |

| 1000 to 1999 mg | 12 | 10 | 1.12 (0.83 to 1.42) | ‐ |

| > 2000 mg | 5 | 4 | 2.27 (0.55 to 3.99) | ‐ |

| Oral dose iron/study month | ||||

| <4000 mg/month | 12 | 10 | 1.44 (0.77 to 2.11) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 4000 to < 6000 mg/month | 12 | 11 | 1.43 (1.16 to 1.69) | ‐ |

| ≥ 6000 mg/month | 7 | 7 | 2.16 (1.18 to 3.14) | ‐ |

| Dose oral iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≥ 12,000 mg | 13 | 13 | 1.44 (1.05 to 1.83) | 0.40 |

| 12000 to 30,000 mg | 10 | 8 | 1.69 (1.05 to 2.34) | ‐ |

| > 30,000 mg | 18 | 12 | 1.79 (1.15 to 2.43) | ‐ |

| Any ESA use | ||||

| No EPO | 8 | 5 | 1.27 (0.46 to 2.08) | 0.91 |

| EPO | 27 | 25 | 1.62 (1.28 to 1.96) | ‐ |

| ESA timing of use | ||||

| Start of study | 8 | 6 | 1.75 (0.88 to 2.62) | 0.70 |

| Before study | 19 | 18 | 1.64 (1.22 to 2.06) | ‐ |

| CKD stage | ||||

| 1 to 5 | 15 | 14 | 1.70 (1.29 to 2.11) | 0.66 |

| Dialysis (5D) | 22 | 18 | 1.50 (1.07 to 1.92) | ‐ |

| Study duration | ||||

| ≥ 2 months | 10 | 13 | 1.18 (0.86 to 1.49) | 0.54 |

| > 2 to ≤ 4 months | 7 | 8 | 2.64 (1.45 to 3.82) | ‐ |

| > 4 months | 9 | 11 | 1.54 (1.05 to 2.04) | ‐ |

| Intervention aim | ||||

| Increase Hb | 24 | 20 | 336 (84 to 588) | 0.12 |

| Maintain Hb | 4 | 4 | 282 (177 to 261) | ‐ |

| Pharmaceutical company sponsorship | ||||

| Unclear | 23 | 20 | 1.84 (1.31 to 2.37) | 0.63 |

| Sponsored | 15 | 13 | 1.36 (1.02 to 1.71) | ‐ |

| Imputed SD | ||||

| Not imputed | ‐ | 5 | 1.18 (0.51 to 1.86) | 0.62 |

| Imputed | ‐ | 26 | 1.63 (1.31 to 1.94) | ‐ |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; EPO ‐ erythropoietin; ESA: erythropoiesis‐stimulating agent; Hb: haemoglobin; SD: standard deviation

4. Subgroup analysis and meta‐regression to examine heterogeneity in transferrin saturation meta‐analyses.

| Total studies (N) | Studies | SMD (95% CI) | P | |

| Dose IV iron/study month | ||||

| ≥ 400 mg/month | 12 | 7 | 0.69 (0.39 to 1.00) | 0.20 |

| > 400 to 700 mg/month | 7 | 5 | 0.46 (0.14 to 0.78) | ‐ |

| > 700 mg/month | 9 | 7 | 2.00 (0.55 to 3.45) | ‐ |

| Dose IV iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≥ 1000 mg | 11 | 8 | 0.62 (0.34 to 0.90) | 0.06 |

| 1000 to 1999 mg | 12 | 9 | 0.41 (0.07 to 0.74) | ‐ |

| > 2000 mg | 5 | 2 | 3.5 (‐1.46 to 8.39) | ‐ |

| Oral dose iron/study month | ||||

| < 4000 mg/month | 12 | 9 | 0.56 (0.25 to 0.86) | 0.21 |

| ≥ 4000 to < 6000 mg/month | 12 | 9 | 0.54 (0.20 to 0.87) | ‐ |

| ≥ 6000 mg/month | 7 | 6 | 1.64 (0.69 to 2.59) | ‐ |

| Dose oral iron (mg total dose) | ||||

| ≥ 12,000 mg | 13 | 11 | 0.56 (0.41 to 0.72) | 0.15 |

| 1200 to 30,000 mg | 10 | 8 | 0.56 (0.00 to 1.13) | ‐ |

| > 30,000 mg | 18 | 8 | 1.59 (0.55 to 2.63) | ‐ |

| Any ESA use | ||||

| No EPO | 8 | 6 | 0.83 (0.36 to 1.31) | 0.83 |

| EPO | 27 | 19 | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.03) | ‐ |

| ESA timing of use | ||||

| Start of study | 8 | 5 | 0.29 (‐0.42 to 1.00) | 0.57 |

| Before study | 19 | 14 | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.20) | ‐ |

| CKD stage | ||||

| 1 to 5 | 15 | 13 | 0.55 (0.35, 0.74) | 0.08 |

| Dialysis (5D) | 22 | 13 | 1.27 (0.75 to 1.80) | ‐ |

| Study duration | ||||

| ≥ 2 months | 14 | 11 | 0.56 (0.41, 0.72) | 0.93 |

| > 2 to ≤ 4 months | 9 | 9 | 1.34 (0.32 to 2.35) | ‐ |

| > 4 months | 14 | 7 | 0.67 (0.16 to 1.18) | ‐ |

| Intervention aim | ||||

| Increase Hb | 24 | 14 | 7.59 (4.07 to 17.11) | 0.18 |

| Maintain Hb | 4 | 4 | 18.28 (‐3.73 to 40.30) | ‐ |

| Pharmaceutical company sponsorship | ||||

| Unclear | 23 | 15 | 1.07 (0.52 to 1.62) | 0.26 |

| Sponsored | 15 | 12 | 0.52 (0.34 to 0.71) | ‐ |

| Imputed SD | ||||

| Not imputed | ‐ | 3 | 0.26 (‐0.24 to 0.77) | 0.45 |

| Imputed | ‐ | 21 | 0.72 (0.47 to 0.97) | ‐ |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; EPO ‐ erythropoietin; ESA: erythropoiesis‐stimulating agent; Hb: haemoglobin; SD: standard deviation

There were no significant differences in total dose administered of IV iron or of IV iron/month between subgroups for Hb or TSAT. There was a significant difference found in the SMD for ferritin in the doses of IV iron per month, though the relationship did not appear to be linear (P = 0.02); there was no difference in ferritin levels with increasing total IV iron dose.

There were no significant differences in total oral iron dose or oral iron/month dose for Hb between subgroups for Hb or TSAT. There was a significant difference found in the SMD for ferritin in the dose of oral iron per month but not with total oral iron dose.

In subgroup analyses no significant differences in results were detected on testing for interaction among studies in which SDs were imputed and other studies (Table 4; Table 5; Table 6).

Exploration of heterogeneity using subgroup analyses: effects of erythrocyte‐stimulating agents (ESAs) on the response to iron therapy

Subgroup analysis was used to investigate the differential response of Hb, ferritin and TSAT levels in patients who did or did not receive an ESA during iron therapy, and in patients who began ESA therapy at study commencement compared with those already on ESA. No significant differences were found among subgroups (Table 4; Table 5; Table 6).

Other subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses of study duration (≤ 2 months, ≥ 2 to 4 months, ≥ 4 months) showed no significant difference on testing for interaction (Table 4; Table 5; Table 6) for final levels or changes in levels in Hb, ferritin or TSAT. There was significant heterogeneity.

Pharmaceutical company sponsorship previously showed some association with a lower mean reported Hb. With additional data in this updated review, no significant association could be demonstrated (Table 4). There were no significant differences for ferritin or TSAT levels (Table 5; Table 6).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review included 39 studies which compared IV iron with oral iron therapy in patients with CKD. Eleven studies were added to the original review; one paediatric study was terminated and provided no outcome data. There was considerable variability among studies in the total dose and duration of IV and oral iron therapies prescribed. Durations of studies ranged from 35 days to 26 months with only 14 studies having durations greater than four months. The doses/month of iron ranged from 200 mg to 1000 mg for IV iron and 840 mg to 10,500 mg for oral iron. Use of ESAs also varied. Eight studies reported that ESAs were not administered. Of the studies that reported ESA use, some maintained ESA doses unchanged and others altered the dose to maintain Hb within a target range.

Patient‐centred outcomes such as death (all causes) (11 studies), cardiovascular death (three studies), and quality of life (five studies) were rarely reported with studies concentrating on surrogate laboratory outcomes. While no differences overall in these outcomes were detected between treatment groups, the data available were limited and of low quality (GRADE) so we have low certainty evidence that IV iron compared with oral iron makes little or no difference to these outcomes.

Compared with oral iron, IV iron increased levels of Hb (31 studies), serum ferritin (33 studies) and TSAT (27 studies). The final weighted mean increase with IV iron compared with oral iron was 0.72 g/dL in Hb, 225 µg/L in ferritin and 8% in TSAT. The proportion of patients who reached the targeted Hb or increased their Hb by 1 g/dL was 71% higher among those treated with IV iron compared with oral iron. Increases in these outcomes were seen in dialysis and non‐dialysis participants (Table 3). The required ESA dose was reduced in patients treated with IV iron compared with oral iron, but was reported in only 11 studies involving 522 participants. eGFR did not decline more rapidly with IV iron compared with oral iron. However, the quality of the evidence (GRADE) was considered low for all outcomes indicating that we have low certainty evidence to support the findings above.

Adverse effects were reported in 18 studies. Gastrointestinal adverse effects were more common with oral iron while allergic reactions and/or hypotension were more common with IV iron. However, the quality of the evidence (GRADE) was considered low indicating that we have low certainty evidence to support these findings.

There was considerable heterogeneity between studies so that subgroup analyses using meta‐regression was carried out to investigate possible reasons for this heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses investigated the effect of different monthly and total doses of oral or IV iron, different uses of ESA, CKD stage, and different durations of treatment on Hb, ferritin and transferrin levels. Other than an increase in ferritin levels with increasing IV and oral iron per month, no differences were found in these analyses. Comparing the results of these subgroup analyses with those in the initial version of this systematic review, no increase in Hb SMD with increased oral iron dose/month could now be demonstrated. There was no longer a significant increase in ferritin levels with total IV or oral iron dose. The additional data from newly identified studies showed that studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies were no longer associated with a significantly lower increase in MD in Hb compared with studies that did not report sponsorship. Heterogeneity among studies therefore remains largely unexplained, but was likely to be related to the significant variation in the relative doses of IV and oral iron used in each study.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most included studies reported on laboratory assessments of response to IV and oral iron treatment in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5 including those receiving dialysis. Our meta‐analyses identified that there are probably small increases in laboratory parameters of Hb, ferritin and transferrin in both dialysis and non‐dialysis patients though the certainty of the evidence was low. However, key patient‐centred outcomes were reported in only a few studies so we were unable to make definitive conclusions about the influence of IV iron compared with oral iron therapy on death (all causes), cardiovascular death, morbidity, or on quality of life. This review confirmed that gastrointestinal disorders are found to be more common in patients taking oral iron while hypotension and allergic reactions are more common in patients receiving IV iron. Although ESA dose was probably lower in patients treated with IV iron, only 11 studies (522 participants) reported on ESA dosage at the end of the study and all studies providing these data were in dialysis patients.

The observed Hb increase of 1.01 g/dL in dialysis patients, together with a significant reduction in ESA dose, provides some support for the practice of administering IV iron to these patients, particularly among those unable to tolerate oral iron. However, studies have identified that high Hb levels achieved with IV iron and ESA are associated with increased cardiovascular death and morbidity (Phrommintikul 2007).

The Hb increase in non‐dialysis patients was modest (0.41 g/dL), but this was not significantly different from the response in dialysis patients. None of the included studies assessed if the patient‐centred benefits of achieving higher Hb levels outweighed financial costs or disruption to patients not on dialysis as a result of additional or prolonged hospital visits. While three further large studies (Agarwal 2015 CKD; FIND‐CKD 2014 CKD; Kalra 2016 CKD) in CKD patients assessed quality of life, none identified improved quality of life with the higher Hb associated with IV iron therapy so that only one of five studies, which assessed quality of life, identified some improvement in quality of life in non‐dialysis patients receiving IV iron (Agarwal 2006 CKD). A systematic review of RCTs identified no significant benefit on quality of life of higher Hb levels achieved with ESAs and iron supplements in CKD patients (Collister 2016).There were no data relating to non‐dialysis patients to determine if ESA requirements were reduced. We were therefore unable to derive a definitive conclusion on the relative benefits and harms of IV iron for non‐dialysis patients.

The applicability of the conclusions in children, PD patients and kidney transplant patients may be limited since few studies were identified for each of these patient groups. However, the magnitude and direction of results in these studies did not differ from the overall results.

Quality of the evidence

Our review included 39 studies, which involved 3852 participants. Twenty‐one studies enrolled dialysis patients, two involved transplant patients, two enrolled dialysis and non‐dialysis patients and the remainder enrolled CKD patients. There was considerable variation among studies in dose and duration of IV and oral iron administration.

Of the 39 included studies, 12 were available only as abstracts. Twenty studies reported adequate random sequence generation while only 14 studies demonstrated adequate allocation concealment. Studies that lack adequate allocation concealment are considered to be at increased risk of bias (Moyer 1998; Schultz 1995). Blinding of participants and personnel was not reported in any study. No study reported blinding of outcome assessment, but because primary outcomes were laboratory measurements and unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding, all studies were considered to be at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment. Twenty‐two studies reported complete outcome data while 20 studies were at low risk of selective reporting. The authors of 15 included studies indicated receiving some form of sponsorship from pharmaceutical companies.

Although administration of IV iron consistently resulted in an increase in Hb or HCT, ferritin and TSAT, there was considerable heterogeneity among studies in the results of these laboratory outcomes. This effect could not be explained after examining for interactions related to participants, interventions and risk of bias items as reported.

The certainty of the evidence for patient centred outcomes was considered low or very low because of small patient numbers included in these analyses and high risk or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment in many studies (Table 1). Similarly the certainty of the evidence for laboratory and pharmaceutical outcomes was considered to be low or very low because of considerable heterogeneity in study results and the high or unclear risk for allocation concealment in many studies (Table 2).

Potential biases in the review process

The literature search has been run several times (up to December 2018) since the publication of the original review in 2012 to reduce the likelihood that additional studies eligible for inclusion were missed. Although the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register also includes references of reports of studies identified by handsearching resources including conference proceedings, it is a possibility that relevant studies may have been missed.

The relatively high proportion of included studies that were available only as abstracts (12/39; 31%) is a potential source of bias as abstracts may not contain complete results or provide detailed information on risk of bias attributes. To address reporting gaps in studies, we contacted authors to seek additional information. Responses from nine study authors were received but information received related principally to risk of bias attributes. In this update, we only identified the full publication of one study (Qunibi 2011 CKD) previously included as an abstract. A large completed RCT (Lu 2010 CKD) comparing IV ferumoxytol with oral iron enrolled 519 participants but has only been published in abstract form in combination with other similar studies.

Some outcomes were reported in only a few studies which increased the risk of selection bias. In particular, the final or change in ESA dose was reported in only 11 studies (522 patients) so that the observed significant decrease in ESA dose with IV iron therapy compared with oral iron may not be generalisable to the dialysis population. Similarly, adverse effects were reported in only 18 (46%) of the included studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews