Abstract

Synthetic oligonucleotides (ODN) expressing CpG motifs mimic the ability of bacterial DNA to trigger the innate immune system via TLR9. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) make a critical contribution to the ensuing immune response. This work examines the induction of antiviral (IFN-β) and pro-inflammatory (IL-6) cytokines by CpG-stimulated human pDCs and the human CAL-1 pDC cell line. Results show that interferon regulatory factor-5 (IRF-5) and NF-κB p50 are key co-regulators of IFN-β and IL-6 expression following TLR9-mediated activation of human pDCs. The nuclear accumulation of IRF-1 was also observed, but this was a late event that was dependant on type 1 IFN and unrelated to the initiation of gene expression. IRF-8 was identified as a novel negative regulator of gene activation in CpG-stimulated pDCs. As variants of IRF-5 and IRF-8 were recently found to correlate with susceptibility to certain autoimmune diseases, these findings are relevant to our understanding of the pharmacologic effects of “K” ODN and the role of TLR9 ligation under physiologic, pathologic, and therapeutic conditions.

Keywords: CpG oligonucleotide, Dendritic cell, IRF-5, NF-κB, TLR9

Introduction

Cells of the immune system utilize TLR to sense ligands uniquely expressed by pathogenic microorganisms. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) use TLR9 to detect the unmethylated CpG motifs present at high frequency in bacterial DNA [1–3]. Synthetic oligonucleotides (ODN) encoding unmethylated CpG motifs mimic the effect of bacterial DNA and trigger pDC activation. Several structurally distinct classes of CpG ODN have been described. Those of the “K” class (also referred to as “B” class) are characterized by their ability to stimulate human pDCs to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. Clinical trials of “K” ODN show promise for the treatment of cancer, allergy, and infectious disease [4, 5]. Identifying the signaling pathways triggered when human pDCs are stimulated by “K” ODN is, thus, of clinical relevance.

pDCs are a major source of type I IFNs and various proinflammatory cytokines [6, 7]. We recently showed that “K” ODN induced a rapid but short-lived pulse of IFN-β. This led to the upregulation of IFN-stimulated genes known to enhance host resistance to virus infection [8–12]. “K” ODN also upregulate the expression of IL-6, which contributes to the activation of multiple pro-inflammatory genes and the subsequent shift from innate to adaptive immunity [8–12]. The current study was designed to identify the key signaling pathway(s) responsible for the upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6, as these would provide important insights into the pattern of “K” ODN mediated activation of human pDCs.

Previous efforts to examine the signaling cascade(s) triggered by the interaction of TLR9 with CpG DNA focused primarily on murine myeloid DCs (mDCs), monocytes, and macrophages [13]. Studies examining the regulation of IL-6 by “K” ODN in mice documented a role for interferon regulatory factor-5 (IRF-5) and the binding of the NF-κB transcription factors p50/p65/c-Rel to the IL-6 promoter [14, 15], while IRF-1 was identified as a key mediator of IFN-β induction by “K” ODN [16]. Yet, there is reason to question whether those findings are applicable to human pDC, as there are fundamental differences in the signaling cascades utilized by mDCs versus pDCs and mice versus humans [2,13,17–20].

The rarity of pDCs in human peripheral blood (they constitute only 0.2–0.5% of the PBMC pool) and ease with which they become activated during the purification process complicates their use [6, 7]. Thus, studies of human pDCs were supplemented by analyses of the human CAL-1 pDC-like cell line to provide novel insights into the regulation of TLR9-mediated activation of human pDCs. CAL-1 cells express TLR9 and mirror the response of primary human pDCs to CpG ODN, as reflected by similar patterns of cytokine induction [12,21,22]. siRNA knockdown studies identified the transcription factors IRF-5 and NF-κB p50 as key early regulators of both IL-6 and IFN-β gene expression in CAL-1 cells. Proximity ligation assays (PLAs) demonstrated that IRF-5 and NF-κB p50 but not p65 significantly co-localized within the nucleus of these cells within 30 min of stimulation, consistent with these factors cooperatively mediating gene expression. In contrast to data derived from murine studies, IRF-8 was identified as a negative regulator of IFN-β and IL-6 expression, indicating that IRF-5 and IRF-8 compete to control gene expression following “K” ODN stimulation in human pDCs. This work also demonstrates that endogenous IRF-5 and IRF-7 are associated with MyD88 in resting CAL-1 cells but stimulation with “K” ODN leads to the activation only of IRF-5. As IRF-5 and IRF-8 variants are associated with autoimmune diseases such as lupus [23–28], these findings are relevant to our understanding of the pharmacologic effects of “K” ODN and the role of TLR9 ligation under physiologic, pathologic, and therapeutic conditions.

Results

CAL-1 cells recapitulate the response of primary human pDCs to “K” ODN stimulation

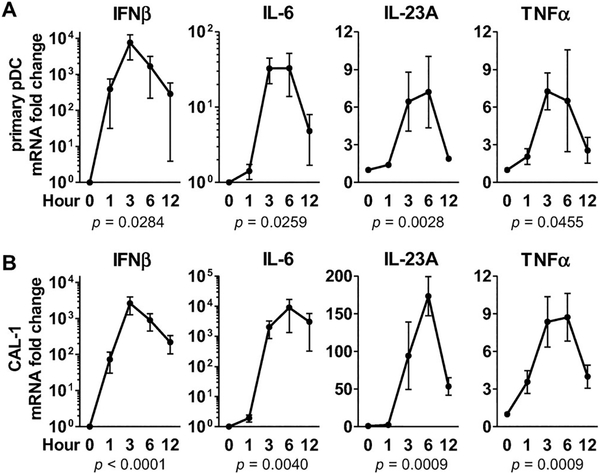

CAL-1 cells share many phenotypic and functional properties of human pDCs [12, 21, 22]. This includes their expression of TLR9 and the specific cytokines produced following CpG stimulation. To confirm these similarities, the effect of “K” ODN on the upregulation of mRNA encoding IFN-β, IL-6, IL-23A, and TNF-α by both cell types was compared.

As seen in Figure 1, the response of CAL-1 cells to CpG ODN followed the same kinetics as primary human pDCs. Although the absolute magnitude of these responses differed, their pattern of cytokine production (including IL-23, a cytokine made abundantly by pDCs) were quite similar, reinforcing the conclusion that CAL-1 cells mimic the response of human pDCs to “K” ODN stimulation. Subsequent studies focused on identifying the signals are involved in the regulation of IFN-β and IL-6 by CAL-1 cells, as those genes are representative of the dominant antiviral and pro-inflammatory responses induced when human pDCs are stimulated with “K” ODN.

Figure 1.

Cytokine production by primary human pDCs and CAL-1 cells stimulated with “K” ODN. CAL-1 cells and freshly isolated human pDCs were stimulated with 1 μM of “K” ODN for the indicated times. mRNA levels for IFN-β, IL-6, IL-23A and TNF-α were assessed by RT-PCR using GAPDH as an endogenous control. Data represent the mean ± SEM from — three to four independent experiments. Overall statistical significance between means was determined using a repeated measures ANOVA.

“K” ODN triggers the rapid nuclear translocation of IRF-5 and NF-κB

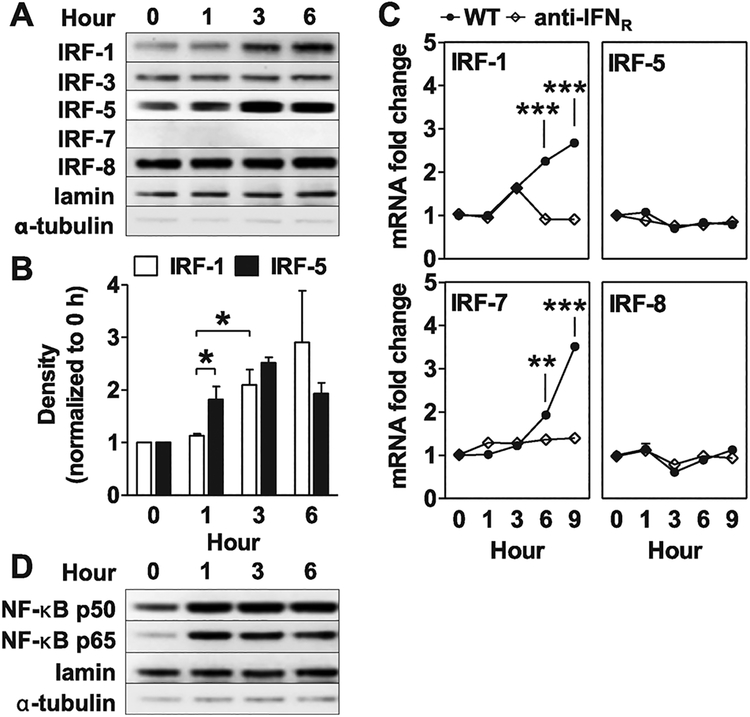

Most IRFs are stored in latent form in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus when activated and phosphorylated [29]. To evaluate the effect of CpG ODN on the behavior of IRFs, CAL-1 cells were incubated with “K” ODN and cytoplasmic and nuclear lysates were examined by immunoblot (Fig. 2A and B and Supporting Information Fig. 1A). The first change observed was a significant rise in intranuclear IRF-5 levels within 1 h of stimulation. This was followed by a significant rise in nuclear IRF-1 at 3 h. In contrast, no translocation of IRFs 3, 7, or 8 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus was observed (Fig. 2A and B and Supporting Information Fig. 1A).

Figure 2.

Nuclear translocation of IRF and NF-κB transcription factors and induction of IRF expression following “K” ODN stimulation. CAL-1 cells were incubated with 1 μM of “K” ODN for the indicated times. Nuclear lysates were extracted and analyzed by immunoblotting for changes in the concentration of (A) various IRFs and (D) NF-κB p50 and p65. (B) The fold increase in nuclear levels of IRF-1 and IRF-5 relative to untreated controls was determined by densitometric analysis. Lamin and α-tubulin were used as quality controls to assess nuclear extract purity and loading levels. (C) The effect of adding anti-type 1 IFN receptor antibody (anti-IFNR) to “K” ODN stimulated cultures was examined. Data represent the mean + SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

CAL-1 cells were stimulated for 1–9 h with “K” ODN to examine whether the accumulation of IRF-1 and IRF-5 protein in the nucleus was associated with corresponding changes in the level of mRNA expression. As seen in Figure 2C, IRF-1 and IRF-7 (a known IFN-stimulated gene) were upregulated at 6 and 9 h (Fig. 2C). When antibody against the type 1 IFN receptor (anti-IFNR) was added, this upregulation was inhibited, suggesting that the effect was dependent upon feedback by type 1 IFN. By comparison, mRNA encoding IRF-5 and IRF-8 did not vary over time. Together, these results suggest that “K” ODN stimulation triggers the translocation of IRF-5 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus while subsequently increasing the expression of mRNA encoding several IRFs.

Members of the NF-κB transcription factor family are actively sequestered in the cytoplasm by IκB proteins. IκB proteins are phosphorylated and degraded upon TLR stimulation, resulting in the translocation of NF-κB complexes to the nucleus [30].

Although NF-κB activation has been studied in mice, data on NF-κB behavior in CpG-stimulated human cells is limited. Analysis of nuclear lysates from “K” ODN treated CAL-1 cells showed that both p50 and p65 translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus within 1 h (Fig. 2D). The cytoplasmic levels of these proteins did not change (Supporting Information Fig. 1B). Overall, these findings indicate that translocation of IRF-5, p50, and p65 to the nucleus are very early events associated with the stimulation of human pDCs by “K” ODN.

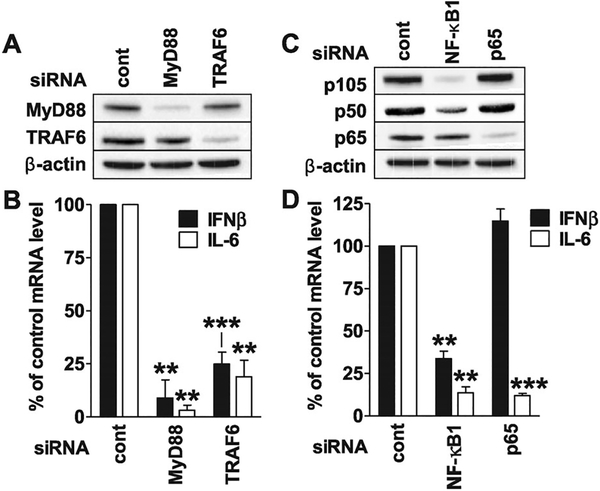

Role of NF-κB1 and p65 in “K” ODN mediated gene activation

Murine studies indicate that the CpG-induced translocation of IRF-5 and NF-κB proceeds via the TLR9/MyD88/TRAF6 signaling pathway [15,31]. To confirm the relevance of this pathway to the upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 mRNA in human pDC, siRNA knockdown studies were performed. As seen in Figure 3A, effective knockdown of MyD88 and TRAF6 protein expression resulted from the transfection of the corresponding siRNA. Neither of these siRNAs caused off-target inhibition (e.g. MyD88 mRNA expression was unaltered when incubated with TRAF6 siRNA and vice versa, Supporting Information Fig. 2A). Consistent with studies of other cell types [15, 31, 32], “K” ODN mediated upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 by CAL-1 cells was MyD88 dependent, as the expression of both genes was reduced by >90% following MyD88 knockdown (p < 0.01; Fig. 3B). The induction of these genes was also dependent on TRAF6, as their expression by CpG-stimulated cells decreased by 60–90% after transfection with TRAF6 siRNA (p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

MyD88/TRAF6 and NF-κB1 and NF-κB p65 influence “K” ODN mediated gene activation. CAL-1 cells were transfected with siRNA to knockdown gene expression. Whole cells lysates were analyzed by immunoblot to evaluate the efficiency of (A) MyD88 and TRAF6 or (C) NF-κB1 (p105/p50) and NF-κB p65 protein knockdown. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B and D) siRNA-transfected CAL-1 cells were stimulated with 1 μM of “K” ODN for 3 h. The percent reduction in IL-6 and IFN-β mRNA levels were assessed by RT-PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. Changes in mRNA levels were evaluated by comparison to identically stimulated cells transfected with control siRNA in each experiment. Data represent the mean + SEM from three independent experiments. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

The contribution of NF-κB1 and p65 to the upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 was then examined. As NF-κB1/p50 is generated by the proteolysis of a p105 precursor, siRNA targeting p105 was used in these experiments [33]. As above, effective and specific knockdown of the targeted gene was achieved, in that NF-κB1 siRNA reduced p105/p50 protein expression while having limited effect on NF-κB p65, and vice versa (Fig. 3C and Supporting Information Fig. 2B). siRNA knockdown studies of “K” ODN stimulated CAL-1 cells showed that both NF-κB1 and p65 contributed significantly to the upregulation of IL-6 expression (86–88% reduction, p < 0.01; Fig. 3D). By comparison, NF-κB1 but not p65 played a role in the upregulation of IFN-β (66% versus 0% reduction, p < 0.01).

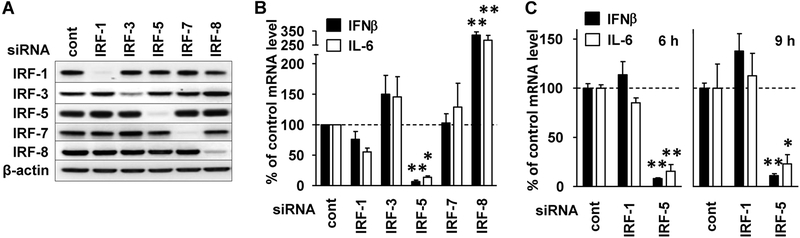

Contribution of IRFs to “K” ODN mediated gene activation

Knockdown studies were conducted to evaluate the contribution of all IRFs that could potentially regulate the expression of either IFN-β or IL-6 in CpG-stimulated pDCs. A total of 70–85% mRNA knockdown efficiencies with high specificity were achieved using siRNAs targeting IRFs 1, 3, 5, 7, and 8 (Supporting Information Fig. 2C). Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates confirmed that each of the target proteins was effectively depleted following knockdown (Fig. 4A). No off-target effects of siRNA transfection on heterologous IRFs were observed at either the mRNA or protein level. The possibility that siRNA itself might upregulate cytokine production, as reported by Hornung et al. [34], was also examined. Cells transfected with siRNA but not treated with CpG showed no increase in mRNA encoding IFN-β or IL-6 compared to untransfected cells (Supporting Information Fig. 2D and E).

Figure 4.

Influence of IRFs on “K” ODN mediated gene activation. CAL-1 cells were transfected with various IRF siRNAs to knockdown gene expression. (A) Whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot to evaluate the efficiency of protein knockdown. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) siRNA-transfected CAL-1 cells were stimulated with 1 μM of “K” ODN for 3 h. (C) The effect of IRF-1 and IRF-5 knockdown was further evaluated at 6 and 9 h. The fold change in IFN-β and IL-6 mRNA levels was assessed by RT-PCR with GAPDH as an endogenous control. Changes in mRNA level were evaluated by comparison to unstimulated cells transfected with control siRNA in each experiment. Data represent the mean + SEM from three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA).

The effect of each IRF knockdown on IL-6 and IFN-β was analyzed at 3 h poststimulation. Knockdown of IRF-5 led to a 93% decrease in IFN-β (p < 0.01) and an 89% decrease in IL-6 mRNA levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The loss of IRFs 1, 3, and 7 had no significant effect on cytokine mRNA levels, whereas knockdown of IRF-8 resulted in a 221% increase in IFN-β (p < 0.01) and 154% increase in IL-6 mRNA levels (p < 0.01). The latter finding is inconsistent with murine studies, which reported that expression of these cytokines was dependent on the presence of IRF-8 [35–37]. This distinction cannot be attributed to any abnormality in the IRF-8 gene present in CAL-1 cells, as multiple sequencing experiments verified that the WT form of this gene was being expressed (sequences compared to the NCBI reference NM 002163.2, data not shown). As nuclear IRF-1 and IRF-5 protein levels continued to rise through 6 h after “K” ODN stimulation (Fig. 2A), their effect on the continued production of IFN-β and IL-6 was examined. siRNA-mediated knockdown of IRF-5 led to a significant decrease of IFN-β and IL-6 mRNA levels through 9 h, whereas the knockdown of IRF-1 still had no effect on cytokine mRNA levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 4C). Overall, these data indicate that IRF-5 (but not IRF-1) contributes to “K” ODN upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 in human pDC, and that IRF-8 negatively regulates the expression of these genes.

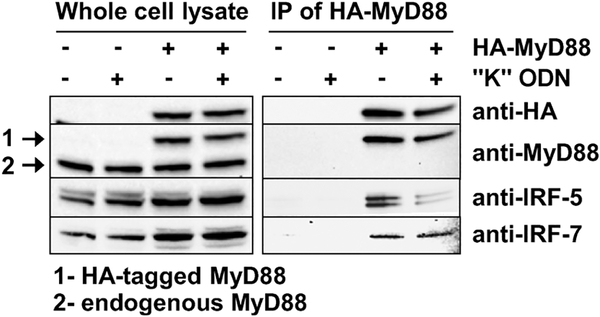

Association of IRF-5 with MyD88

Previous studies examining other cell types found that IRF-5 and/or IRF-7 could form complexes with MyD88 [15, 17, 38]. To examine this issue in human pDCs, CAL-1 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-tagged MyD88 [39]. Analysis of the lysate generated from unstimulated cells showed that HA-tagged MyD88 co-precipitated with both IRF-5 and IRF-7 (Fig. 5). When stimulated with “K” ODN, the amount of IRF-5 associating with HA-MyD88 decreased while IRF-7 association remained unchanged (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that human IRF-5 and IRF-7 both complex with MyD88 in resting CAL-1 cells. Upon CpG triggering, the association of IRF-5 with MyD88 decreases, presumably reflecting the activation/translocation of IRF-5 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

Figure 5.

Association of IRF-5 with MyD88. CAL-1 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-tagged MyD88 and then stimulated for 30 min with 1 μM of “K” ODN. A whole cell lysate (left panel) was prepared and analyzed by immunoblot for the presence of MyD88 (endogenous or HAtagged), IRF-5, and IRF-7. The right panel shows proteins that co-precipitated with the HA-tagged MyD88. Data are representative of results obtained in two independent experiments.

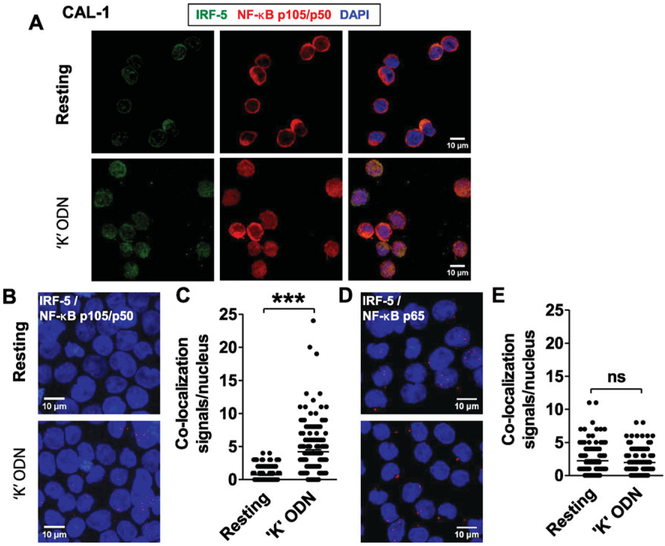

Nuclear co-localization of IRF-5 and NF-κB p50 following “K” ODN stimulation

IRF-5 and NF-κB p50 both translocated to the nucleus of CAL-1 cells within 1 h of CpG stimulation (Fig. 2) and both contributed to the upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 (Fig. 3 and 4). These findings raised the possibility that IRF-5 might directly interact with p50. An immunofluorescence-based assay was used to examine the nuclear localization of each transcription factor. Consistent with the results in Figure 2, exposure of CAL-1 cells to “K” ODN led to the accumulation of both IRF-5 and p50 in the nucleus (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Co-localization of IRF-5 with NF-κB p50 in CpG-stimulated CAL-1 cells. (A) CAL-1 cells were stimulated for 60 min with 1 μM of “K” ODN. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained to detect IRF-5 (green) and NF-κB p105/p50 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B–E) CAL-1 cells were stimulated for 30 min with 1 μM of “K” ODN. The co-localization (red dots) of (B) IRF-5 with NF-κB p105/p50 and (D) IRF-5 with p65 was determined by proximity ligation assay. The frequency of IRF-5/NF-κB p50 (C) and IRF-5/p65 (D) co-localization events per CAL-1 nucleus is shown (N > 150 cells per treatment from two independent experiments). Scale bars: 10 μM. ***p < 0.0001, Student’s t-test.

To determine whether these transcription factors were associating in the nucleus, a PLA was employed. PLA generates a signal only when the proteins of interest are in close physical proximity (<40 nm distant, [40]). Thirty minutes after treating CAL-1 cells with “K” ODN, significant nuclear co-localization of IRF-5 with NF-κB p50 was detected (p < 10−4 when compared to unstimulated cells, Fig. 6B and C). This nuclear co-localization was specific since PLA analysis found no increase in the frequency with which NF-κB p50 co-localized with p65 in identically treated cells (Fig. 6D and E).

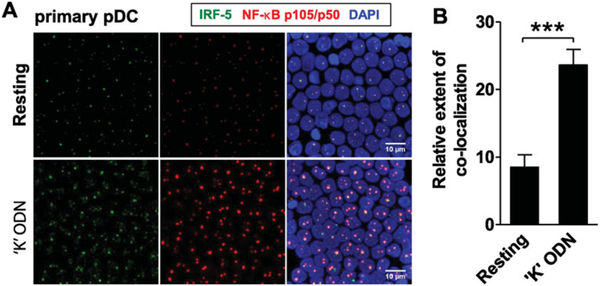

Similar results were obtained in immunofluorescence studies of freshly isolated human pDCs. Consistent with results from CAL-1 cells, the nuclear localization of both proteins increased significantly after stimulation with “K” ODN (Fig. 7A and B). Limited IRF-5 and p50 co-localization was observed in freshly isolated pDCs, presumably reflecting cell activation in vivo or during the purification process. The level of co-localization increased nearly threefold after CpG stimulation (average 8.5 ± 0.9 versus 23.6 ± 1.2 μm2, p < 0.0001, Fig. 7A and B). These findings support the conclusion that “K”-driven pDC stimulation involves the nuclear co-localization of IRF-5 with p50.

Figure 7.

Co-localization of IRF-5 with NF-κB p105/p50 in CpG-stimulated primary pDCs. (A) Primary pDCs were stimulated for 60 min with 1 μM of “K” ODN. Cells were fixed onto slides, permeabilized, and stained to detect IRF-5 (green), NF-κB p105/p50 (red), and nuclei (blue) as described in Figure 5. (B) Four areas per slide were analyzed using Image J software to detect and quantify IRF-5/NF-κB p50 nuclear co-localization signals. Results represent the relative number of co-localization events per treatment. Data are shown as mean +SD and are representative of one of three independent experiments performed with similar results. Scale bars: 10 μM. ***p < 0.0001, Student’s t-test.

Discussion

pDCs make a critical contribution to both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune response. Activated pDCs excel in antigen presentation and produce IFNs and other pro-inflammatory cytokines required for host defense [13, 41]. Human pDCs utilize TLR9 to sense the unmethylated CpG motifs present in microbial DNA. “K” ODN have been evaluated in phase I–III clinical trials as immunotherapeutics for the treatment of cancer, allergy, and infectious diseases [4, 42–44]. Understanding the signaling cascades and patterns of gene expression triggered by the recognition of “K” ODN by human pDCs is thus of both fundamental and therapeutic relevance.

We and others recently established that “K” ODN induced human pDCs to upregulate the expression of two functionally defined groups of genes: those involved in antiviral responses (exemplified by IFN-β) and those involved in pro-inflammatory responses (exemplified by IL-6) [8,12]. Current studies clarify the regulatory pathways underlying the activation of those genes by studying CAL-1 cells. Efforts to resolve this issue solely by studying resting human pDCs were impeded by the rarity of such cells (they typically constitute less than 0.5% of PBMCs) and their propensity to activate during the purification process [6, 7]. The use of CAL-1 cells also facilitated analysis of the behavior of intracellular proteins. Unlike previous studies that relied upon protein overexpression models [15, 38, 45], both the level of expression and interaction between cellular proteins could be studied under physiologic conditions in CAL-1 cells.

The effect of CpG ODN on murine DCs has been examined extensively. However, human and murine TLR9 molecules differ by 24% at the amino acid level [46] and the hexameric CpG motifs that optimally stimulate human pDCs differ from those most active in mice (and vice versa) [46]. Similarly, the regulatory regions and splice patterns of genes involved in CpG signaling have diverged between mouse and human [47]. Thus, the relevance of results from earlier studies examining mixed populations of murine mDCs and pDCs (both of which respond to CpG stimulation) to human pDCs is unclear.

CAL-1 cells mirror the response of primary human pDCs to multiple forms of stimulation, including that delivered by “K” ODN (Fig. 1; [12,21,22]). The role of IRFs in regulating IFN-β and IL-6 expression following CpG stimulation of CAL-1 cells was examined by nuclear translocation assays and transient knockdown experiments (Fig. 2 and 4). Previous reports showed that IRFs 3 and 7 were the main inducers of type I IFN following virus infection of human pDCs [1,17,41,48]. Yet, neither of those IRFs was involved in the gene activation induced by “K” ODN (Fig. 4). Rather, “K” ODN induced the rapid translocation of IRF-5 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, followed several hours later by the translocation of IRF-1 (Fig. 2A and B). siRNA-mediated knockdown studies confirmed that IRF-5 but not IRF-1 played a central role in regulating “K” ODN mediated IFN-β and IL-6 mRNA expression (Fig. 4).

Experiments involving IRF-5 KO mice showed that the induction of IL-6 but not type I IFN was impaired in CpG-stimulated pDCs [15]. Yet, Paun et al. [45] reported that IFN-β mRNA declined when DCs from IRF-5 KO mice were stimulated with “K” ODN. Due to differences in the splice patterns of murine versus human IRF-5, it was unclear whether the murine results would be applicable to human pDCs [47]. Current findings clarify that IRF-5 plays a critical role in the upregulation of IFN-β and IL-6 in CpG-stimulated human pDCs.

Evidence that MyD88 associates with IRF-5 in the cytoplasm was previously provided by studies involving murine HEK293T cells that overexpressed both proteins [15]. The current work examined this issue by transfecting CAL-1 cells with HA-tagged MyD88. Immunoprecipitation using anti-HA Ab provided the first evidence that endogenous IRF-5 as well as IRF-7 physically interacted with MyD88 under physiologic conditions in human pDC-like cells. Importantly, “K” ODN stimulation led to a significant decline in the amount of IRF-5 that co-precipitated with MyD88 (Fig. 5). This observation is consistent with the data showing that IRF-5 (but not IRF-7) translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus of “K” ODN activated CAL-1 cells (Fig. 2A and B).

Controversy exists regarding the role of IRF-1 in CpG-mediated gene activation [16,49]. Schmitz et al. [16] observed that cytokine production was impaired in CpG-treated DCs from IRF-1 KO mice and concluded that IRF-1 contributed to the subsequent upregulation of IFN-β. In contrast, Liu et al. [49] reported that “K” ODN actively inhibited the binding of IRF-1 to the IFN-β promoter of murine DCs, thereby preventing the upregulation of type I IFN. Current findings indicate that IRF-1 accumulates in the nucleus of CpG-stimulated CAL-1 cells, but that this is a relatively late event (Fig. 2A and B) mediated by an increase in mRNA influenced by type 1 IFN feedback (Fig. 2C). In this context, the knockdown of IRF-1 had no impact on early or late IFN-β and IL-6 expression (Fig. 4B and C). Thus, current findings lead to a reinterpretation of the results of Schmitz et al. and Liu et al.

IRF-8 (also known as interferon consensus sequence-binding protein) can either inhibit or promote gene activation [50]. IRF-8 was originally identified as a repressor of IFN-stimulated response elements and through its ability to inhibit the transcriptional activation of other IRFs [50, 51]. Yet, studies of human monocytes and murine cDCs found that IRF-8 promoted type I IFN production [35, 52]. Current findings show that IRF-8 is a strong negative regulator of CpG-driven IFN-β and IL-6 production by human pDCs (Fig. 4B). This is an important observation, as pDCs constitutively express high levels of IRF-8 [13] and IRF-8 KO mice fail to generate pDCs [36]. Taken together, current findings demonstrate that IRF-8 expression plays a role in negatively regulating pro-inflammatory and IFN responses following TLR9 stimulation of pDCs. We are in the process of examining whether the elevated levels of IRF-8 in the nucleus of unstimulated pDCs (Fig. 2) reflect a constitutive role for IRF-8 in the regulation of gene activation and whether IRF-8 interacts with IRF-5.

Several findings support the technical reliability of results from the knockdown experiments upon which these conclusions are largely based. First, no off-target (i.e. nonspecific) activity was detected with any of the siRNAs tested (Fig. 3A and C and 4A, and Supporting Information Fig. 2A–C). Second, cells transfected with siRNA were not stimulated unless CpG ODN was added (in contrast to the report by Hornung et al. [34]) (Supporting Information Fig. 2D and E). Third, siRNA administration significantly reduced the level of expression of both mRNA and protein of the targeted gene (Fig. 3A and C and 4A, Supporting Information Fig. 2A–C). Finally, siRNA knockdown of MyD88 and TRAF6 blocked the induction of IFN-β and IL-6 mRNA by CpG-stimulated pDCs, consistent with earlier reports (Fig. 3B; [15,31,32]).

“K” ODN triggered the rapid translocation of NF-κB p50 and p65 (RelA) from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in CAL-1 cells and human pDCs (Fig. 2D, 6, and 7). Interestingly, the knockdown of p105/p50 but not p65 significantly reduced IFN-β production (Fig. 3D), whereas both p105/p50 and p65 contributed to the induction of IL-6. Accumulating evidence indicates that IκBξ (also known as MAIL, a nuclear ankyrin repeat protein) is required for TLR-dependent upregulation of IL-6 [53, 54]. As IκBξ associates with both p50 and p65 [55], current findings suggest that eliminating either impairs IκBξ-dependent induction of IL-6.

“K” ODN induced the rapid nuclear translocation of both IRF-5 and NF-κB p50 (Fig. 2, 6, and 7). PLA, a technique used to identify protein–protein interactions under physiologic conditions, was employed to examine whether these transcriptional factors associated upon stimulation [40]. Only proteins in close proximity (<40 nM) are visualized by PLA, yielding results comparable to resonance energy transfer techniques (such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis). Moreover, PLA has the advantage of detecting interactions between endogenous proteins at physiologic levels (e.g. protein overexpression is not required). Results showed that co-localization of IRF-5 with p50 but not p65 increased in the nucleus shortly after “K” ODN stimulation (Fig. 6 and 7). While this finding does not exclude the possibility that IRF-5 interacts with p50 in the cytoplasm, it is consistent with IRF-5 and p50 cooperatively regulating the expression of IFN-β and IL-6 when binding in close proximity to the promoter region of those genes.

In the broader context of human disease, recent genome-wide association studies implicate IRF-5 and IRF-8 variants in susceptibility to autoimmune diseases such as lupus and multiple sclerosis [23–27,56]. IFN-β levels impact the severity of both diseases, and CpG-driven activation of pDCs has been implicated in the overproduction of IFN-β [57–59]. While previous studies focused on the association between IRF-5 and type I IFN in the context of TLR7 signaling [60], current results demonstrate that IRF-5 is a critical regulator of IFN-β downstream of TLR9 in human pDCs. These insights concerning the contribution of IRF-5 and IRF-8 to the regulation of CpG-induced IFN-β advances our understanding the pathophysiology of autoimmune diseases and helps identify targets for pharmaceutical intervention.

This work is the first to establish that IRF-5 plays a critical role in the MyD88/TRAF6-dependent induction of IFN-β (a marker of antiviral activity) and IL-6 (a marker of pro-inflammatory activity) following TLR9-mediated stimulation of human pDCs. It shows that the activity of IRF-5 includes an association with NF-κB p50, and identifies IRF-8 as a negative regulator of gene expression in CpG-stimulated human pDCs. These results suggest that the major route through which “K” ODN stimulate human pDCs is via IRF-5 and p50, resulting in the upregulation of both antiviral and pro-inflammatory genes critical to the induction of an adaptive immune response (Supporting Information Fig. 3). Ongoing studies are directed toward determining whether other genes containing binding sites for both transcription factors are similarly regulated.

Materials and methods

Oligonucleotides

Endotoxin-free ODN were synthesized at the CBER core facility (CBER/FDA, Bethesda, MD, USA). “K” ODN contained an equimolar mixture of three phosphorothioate sequences: K3 (5′-ATCGACTCTCGAGCGTTCTC-3′), K23 (5′-TCGAGCGTTCTC-3′), and K123 (5′-TCGTTCGTTCTC-3′).

Cell culture, preparation, and stimulation

The CAL-1 human pDC cell line was grown in complete RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 1× MEM NEAA (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) to which 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Lonza) was added. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a CO2 in air incubator. Prior to stimulation, the CAL-1 cells were maintained at a concentration of less than 0.5 × 106 cells/mL under serum-starved conditions for 16 h (in complete RPMI supplemented with 0.1% fetal bovine serum) and then treated with 1 μM “K” ODN for the indicated times. In some experiments, 5 μg/mL of anti-type 1 IFN receptor antibody (mouse anti-human IFNa/βR chain 2, PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ, USA) was added 30 min prior to stimulation. Cell concentrations were kept below 106 cells/mL by passage every 2 days and individual cultures were maintained for less than 3 weeks.

Mononuclear cell enriched human buffy coats were obtained by leukopheresis (DTM, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) using an IRB-approved protocol. Following Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Percoll gradient (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) centrifugation of the buffy coat, pDCs were MACS sorted using a BDCA-2 purification kit as per manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA, USA). The pDCs isolated by this procedure were 93–95% pure and their viability was >95%. A total of 5 × 105 freshly isolated pDC per well were cultured in 48-well plates in complete media and then stimulated with 1 μM “K” ODN for the times indicated.

Protein extraction and immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed on whole CAL-1 cell lysates. Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Scientific, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). A total of 10 μg of nuclear and 30 μg of cytoplasmic lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were then probed for IRF-3 (D83B9), IRF-7 (#4920), NF-κB p105/p50 (#3035), NF-κB p65 (C22B4), α-tubulin (11H10), β-actin (13E5) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA), IRF-1 (B-1), IRF-8 (C-19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), or IRF-5 (10T1) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Additional antibodies used to validate siRNA knockdown efficiencies and in immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation preparations included MyD88 (E-11), TRAF6 (D-10), and HA-probe (Y-11) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Densitometric analysis was performed using Syngene GeneTools v4.0. The specificity of these antibodies was established in siRNA knockdown studies (Fig. 3A and C and 4A, and Supporting Information Fig. 2).

Cell transfection

CAL-1 cells were transfected at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/well with 1 nM of siRNA or 500 ng of human HA-MyD88 plasmid (gift from Dr. Bruce Beutler, Addgene plasmid 12287) using an optimized Amaxa 96-well shuttle nucleofector system (DN100, cell line SF, Lonza). siRNA to MyD88, TRAF6, NF-κB1 (p105/p50), RelA (p65), IRF-1, IRF-5 (Silencer Select, Ambion), IRF-3, IRF-7, or IRF-8 (Invitrogen stealth RNAi) was used. Silencer Select Negative Control #1 siRNA (Ambion) was used as a negative control. Cells transfected with siRNA were recovered in complete media supplemented with 10% FBS for 4 h and then serum starved for 16 h in 0.1% FBS complete RPMI media prior to knockdown efficiency analysis or stimulation. Cells transfected with the HAMyD88 plasmid were rested for 16 h in 50% cell-conditioned media with 50% fresh RPMI media containing 10% FBS. Following recovery, the cells were serum starved for 8 h in 0.1% FBS media prior to stimulation.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

CAL-1 cells transfected with the HA-MyD88 plasmid were stimulated with “K” ODN for 30 min, washed with PBS, and lysed in buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 for 20 min on ice. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13 000 × g for 20 min and quantified by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce). A total of 30 μg of this protein lysate was used as the whole cell lysate control. A total of 500 μg of the protein lysate was incubated overnight with rotation at 4°C in 1 mL of lysis buffer with 100 μL of anti-HA affinity matrix beads (Roche ref. 11815016001). Following incubation, the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and prepared for Western blot analysis.

Proximity ligation and immunofluorescence assays

CAL-1 cells and primary pDCs were stimulated with “K” ODN for 30–60 min. Cells were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with methanol. CultureWell Chambered coverslips (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) were treated with 0.05 μg/μL of Cell-Tak (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were seeded onto the cover slips, blocked and stained with mouse anti-IRF-5 (10T1) (Abcam) and rabbit anti-NF-κB p105/p50 (#3035) or anti-NF-κB p65 (D14E12) (Cell Signaling) Ab.

For immunofluorescence studies, washed cells were incubated with complementary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 and AlexaFluor 546, respectively. Nuclear co-localization was evaluated using the ImageJ plugin “Colocalization Highlighter”. For PLA studies, washed cells were incubated with anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary PLA probes (Olink Bioscience, Uppsalla, Sweden) and then with ligation and Red Amplification solutions as per manufacturer’s instructions. Washed cells were sealed onto the slide using Duolink II Mounting Medium with DAPI. Image stacks were captured using an inverted Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope and evaluated using the analyze particles feature of ImageJ.

RT-PCR expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from CAL-1 cells or primary pDCs as per manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (QuantiTect RT Kit; Qiagen) and quantified by TaqMan-based real-time PCR (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The following TaqMan probes were used: IFNB1 (Hs02621180 s1), IL-6 (Hs00174131 m1), IL23A (Hs00372324 m1), TNF (Hs00174128 m1), NF-κB1 (Hs00765730 m1), RELA (Hs01042010 m1), MyD88 (Hs00182082 m1), TRAF6 (Hs00371508 m1), IRF-1 (Hs009 71960 m1), IRF-3 (Hs015 47283 m1), IRF-5 (Hs001 58114 m1), IRF-7 (Hs010 14809 g1), IRF-8 (Hs0 0175 238 m1), and GAPDH (Hs0275 8991 g1). GAPDH levels did not change upon stimulation or during siRNA gene silencing. Data were analyzed by StepOne Software v2.1. using GAPDH as an endogenous control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Debra Tross-Currie for technical assistance; Bruce Beutler for providing the HA-MyD88 plasmid; and Hide Shirota, Stefan Sauer, Lyudmila A. Lyakh, and Dan McVicar for discussions and advice. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, and partly funded with Contract No. HHSN261200800001E and by the Department of Immunology, University of Washington. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- IRF

interferon regulatory factor

- mDC

myeloid dendritic cell

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- PLA

proximity ligation assay

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site

See accompanying Commentary by Latz

Conflict of interest:

Dr. Dennis Klinman and members of his lab are co-inventors on a number of patents concerning CpG ODN and their use. All rights to these patents have been assigned to the Federal government.

References

- 1.Kawai T and Akira S, The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol 2010. 11: 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrossay D, Napolitani G, Colonna M, Sallusto F and Lanzavecchia A, Specialization and complementarity in microbial molecule recognition by human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol 2001. 31: 3388–3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadowaki N, Ho S, Antonenko S, Malefyt RW, Kastelein RA, Bazan F and Liu YJ, Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different Toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. J. Exp. Med 2001. 194: 863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haining WN, Davies J, Kanzler H, Drury L, Brenn T, Evans J, Angelosanto J et al. , CpG oligodeoxynucleotides alter lymphocyte and dendritic cell trafficking in humans. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008. 14: 5626–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhagen F, Kinjo T, Bode C and Klinman DM, TLR-based immune adjuvants. Vaccine 2011. 29: 3341–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegal FP, Kadowaki N, Shodell M, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly PA, Shah K, Ho S Antonenko S, et al. , The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science 1999. 284: 1835–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallucci S, Lolkema M and Matzinger P, Natural adjuvants: endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nat. Med 1999. 11: 1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato A, Homma T, Batchelor J, Hashimoto N, Imai S, Wakiguchi H Saito H, et al. , Interferon-alpha/beta receptor-mediated selective induction of a gene cluster by CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 2006. BMC Immunol. 2003 4: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerkmann M, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Towarowski A, Wagner M, Sarris A, Giese T et al. , Activation with CpG-A and CpG-B oligonucleotides reveals two distinct regulatory pathways of type I IFN synthesis in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol 2003. 170: 4465–4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray RC, Kuchtey J and Harding CV, CpG-B ODNs potently induce low levels of IFN-alphabeta and induce IFN-alphabeta-dependent MHC-I cross-presentation in DCs as effectively as CpG-A and CpG-C ODNs. J. Leukoc. Biol 2007. 81: 1075–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones SA, Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J. Immunol 2005. 175: 3463–3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinhagen F, Meyer C, Tross D, Gursel M, Maeda T, Klaschik S and Klinman DM, Activation of type I interferon dependent genes characterizes the ‘core response’ induced by CpG DNA. J. Leukoc. Biol 2012. 92:775–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Dai J and Singh S, Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I IFN: 50 years of convergent history. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008. 19: 3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeshita F, Ishii KJ, Ueda A, Ishigatsubo Y and Klinman DM, Positive and negative regulatory elements contribute to CpG oligonucleotide-mediated regulation of human IL-6 gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol 2000. 30: 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takaoka A, Yanai H, Kondo S, Duncan G, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Kano S et al. , Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by Toll-like receptors. Nature 2005. 434: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz F, Heit A, Guggemoos S, Krug A, Mages J, Schiemann M, Adler H et al. , Interferon-regulatory-factor 1 controls Toll-like receptor 9-mediated IFN-beta production in myeloid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol 2007. 37: 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda K, Ohba Y, Yanai H, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Takaoka A, Taya C et al. , Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88-IRF-7 signalling for robust type-I interferon induction. Nature 2005. 434: 1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasai M, Linehan MM and Iwasaki A, Bifurcation of Toll-like receptor 9 signaling by adaptor protein 3. Science 2010. 329: 1530–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser F, Cook D, Papoutsopoulou S, Rajsbaum R, Wu X, Yang HT, Grant S et al. , TPL-2 negatively regulates interferon-beta production in macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med 2009. 206: 1863–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder K, Spille M, Pilz A, Lattin J, Bode KA, Irvine KM, Burrows AD et al. , Differential effects of CpG DNA on IFN-beta induction and STAT1 activation in murine macrophages versus dendritic cells: alternatively activated STAT1 negatively regulates TLR signaling in macrophages. J. Immunol 2007. 179: 3495–3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cisse B, Caton ML, Lehner M, Maeda T, Scheu S, Locksley R, Holmberg D et al. , Transcription factor E2–2 is an essential and specific regulator of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. Cell 2008. 135: 37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda T, Murata K, Fukushima T, Sugahara K, Tsuruda K, Anami M, Onimaru Y et al. , A novel plasmacytoid dendritic cell line, CAL-1, established from a patient with blastic natural killer cell lymphoma. Int. J. Hematol 2005. 81: 148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flesher DL, Sun X, Behrens TW, Graham RR and Criswell LA, Recent advances in the genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol 2010. 6: 461–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Y and Tsao BP, Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 2010. 6: 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, Ortmann W et al. , A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet 2009. 41: 1228–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salloum R and Niewold TB, Interferon regulatory factors in human lupus pathogenesis. Transl. Res 2011. 157: 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Goring HH, Lindroos K, Wiman AC, Sturfelt G, Jonsen A et al. , Polymorphisms in the tyrosine kinase 2 and interferon regulatory factor 5 genes are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2005. 76: 528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Jager PL, Jia X, Wang J, de Bakker PI, Ottoboni L, Aggarwal NT, Piccio L et al. , Meta-analysis of genome scans and replication identify CD6, IRF-8 and TNFRSF1A as new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet 2009. 41: 776–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D and Taniguchi T, The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol 2008. 26: 535–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh S and Hayden MS, New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2008. 8: 837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hacker H, Vabulas RM, Takeuchi Hoshino K, Akira S and Wagner H, Immune cell activation by bacterial CpG-DNA through myeroid differentiation marker 88 and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)6. J. Exp. Med 2000. 192: 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenemeyer A, Barnes BJ, Mancl ME, Latz E, Goutagny N, Pitha PM, Fitzgerald KA et al. , The interferon regulatory factor, IRF-5, is a central mediator of Toll-like receptor 7 signaling. J. Biol. Chem 2005. 280: 17005–17012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vallabhapurapu S and Karin M, Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol 2009. 27: 693–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornung V, Guenthner-Biller M, Bourquin C, Ablasser A, Schlee M, Uematsu S, Noronha A et al. , Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-alpha by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat. Med 2005. 11: 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tailor P, Tamura T, Kong HJ, Kubota T, Kubota M, Borghi P, Gabriele L et al. , The feedback phase of type I interferon induction in dendritic cells requires interferon regulatory factor 8. Immunity 2007. 27: 228–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, Kong HJ, Tsujimura H, O’Shea JJ, Singh H et al. , IFN regulatory factor-4 and −8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J. Immunol 2005. 174: 2573–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsujimura H, Tamura T, Kong HJ, Nishiyama A, Ishii KJ, Klinman DM and Ozato K, Toll-like receptor 9 signaling activates NF-kappaB through IFN regulatory factor-8/IFN consensus sequence binding protein in dendritic cells. J. Immunol 2004. 172: 6820–6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honda K, Yanai H, Mizutani T, Negishi H, Shimada N, Suzuki N, Ohba Y et al. , Role of a transductional-transcriptional processor complex involving MyD88 and IRF-7 in Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004. 101: 15416–15421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Z, Georgel P, Li C, Choe J, Crozat K, Rutschmann S, Du X et al. , Details of Toll-like receptor: adapter interaction revealed by germ-line mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006. 103: 10961–10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soderberg O, Gullberg M, Jarvius M, Ridderstrale K, Leuchowius KJ, Jarvius J, Wester K et al. , Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat. Met 2006. 3: 995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilliet M, Cao W and Liu YJ, Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: sensing nucleic acids in viral infection and autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2008. 8: 594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klinman DM, Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2004. 4: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halperin SA, Dobson S, McNeil S, Langley JM, Smith B, Call-Sani R, Levitt D et al. , Comparison of the safety and immunogenicity of hepatitis B virus surface antigen co-administered with an immunostimulatory phosphorothioate oligonucleotide and a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in healthy young adults. Vaccine 2006. 24: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rynkiewicz D, Rathkopf M, Sim I, Waytes AT, Hopkins RJ, Giri L, DeMuria D et al. , Marked enhancement of the immune response to BioThraxR (Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed) by the TLR9 agonist CPG 7909 in healthy volunteers. Vaccine 2011. 29: 6313–6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paun A, Reinert JT, Jiang Z, Medin C, Balkhi MY, Fitzgerald KA and Pitha PM, Functional characterization of murine interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF-5) and its role in the innate antiviral response. J. Biol. Chem 2008. 283: 14295–14308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K et al. , A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 2000. 408: 740–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mancl ME, Hu G, Sangster-Guity N, Olshalsky SL, Hoops K, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Pitha PM et al. , Two discrete promoters regulate the alternatively spliced human interferon regulatory factor-5 isoforms. Multiple isoforms with distinct cell type-specific expression, localization, regulation, and function. J. Biol. Chem 2005. 280: 21078–21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK and Chen ZJ, Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF-3. Cell 2005. 122: 669–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu YC, Gray RC, Hardy GA, Kuchtey J, Abbott DW, Emancipator SN and Harding CV, CpG-B oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit TLR-dependent and -independent induction of type I IFN in dendritic cells. J. Immunol 2010. 184: 3367–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levi BZ, Hashmueli S, Gleit-Kielmanowicz M, Azriel A and Meraro D, ICSBP/IRF-8 transactivation: a tale of protein-protein interaction. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002. 22: 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharf R, Azriel A, Lejbkowicz F, Winograd SS, Ehrlich R and Levi BZ, Functional domain analysis of interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP) and its association with interferon regulatory factors. J. Biol. Chem 1995. 270: 13063–13069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li P, Wong JJ, Sum C, Sin WX, Ng KQ, Koh MB and Chin KC, IRF-8 and IRF-3 cooperatively regulate rapid interferon-beta induction in human blood monocytes. Blood 2011. 117: 2847–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seshadri S, Kannan Y, Mitra S, Parker-Barnes J and Wewers MD, MAIL regulates human monocyte IL-6 production. J. Immunol 2009. 183: 5358–5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto M, Yamazaki S, Uematsu S, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T et al. , Regulation of Toll/IL-1-receptor-mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IkappaBzeta. Nature 2004. 430: 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Totzke G, Essmann F, Pohlmann S, Lindenblatt C, Janicke RU and Schulze-Osthoff K, A novel member of the IkappaB family, human IkappaB-zeta, inhibits transactivation of p65 and its DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem 2006. 281: 12645–12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jarvinen TM, Hellquist A, Zucchelli M, Koskenmies S, Panelius J, Hasan T, Julkunen H et al. , Replication of genome-wide association study identified systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility genes affirms B-cell receptor pathway signalling and strengthens the role of IRF-5 in disease susceptibility in a Northern European population. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011. 51: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eloranta ML, Franck-Larsson K, Lovgren T, Kalamajski S, Ronnblom A, Rubin K, Alm GV et al. , Type I interferon system activation and association with disease manifestations in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis 2010. 69: 1396–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yasuda K, Richez C, Uccellini MB, Richards RJ, Bone-gio RG, Akira S, Monestier M et al. , Requirement for DNA CpG content in TLR9-dependent dendritic cell activation induced by DNA-containing immune complexes. J. Immunol 2009. 183: 3109–3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Viglianti GA, Lau CM, Hanley TM, Miko BA, Shlomchik MJ and Marshak-Rothstein A, Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA. Immunity 2003. 19: 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yasuda K, Richez C, Maciaszek JW, Agrawal N, Akira S, Marshak-Rothstein A and Rifkin IR, Murine dendritic cell type I IFN production induced by human IgG-RNA immune complexes is IFN regulatory factor (IRF-5 and IRF-7 dependent and is required for IL-6 production. J. Immunol 2007. 178: 6876–6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.