Abstract

Difficulty integrating inputs from different sensory sources is commonly reported in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Accumulating evidence consistently points to altered patterns of behavioral reactions and neural activity when individuals with ASD observe or act upon information arriving through multiple sensory systems. For example, impairments in the integration of seen and heard speech appear to be particularly acute, with obvious implications for interpersonal communication. Here, we explore the literature on multisensory processing in autism with a focus on developmental trajectories. While much remains to be understood, some consistent observations emerge. Broadly, sensory integration deficits are found in children with an ASD whereas these appear to be much ameliorated, or even fully recovered, in older teenagers and adults on the spectrum. This protracted delay in the development of multisensory processing raises the possibility of applying early intervention strategies focused on multisensory integration, to accelerate resolution of these functions. We also consider how dysfunctional cross-sensory oscillatory neural communication may be one key pathway to impaired multisensory processing in ASD.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Typical Development, multisensory integration, sensory processing, amelioration, normalization, time window of integration, recovery, oscillation, phase alignment, phase reset

1. Introduction

Humans and animals have evolved an exquisitely sensitive and highly diverse repertoire of sensory receptors to sample the multiple sources of energy available in our environment. In turn, neural plasticity during development allows the neural architecture of the infant brain to learn to combine and integrate these sources of information in ways that enhance performance and improve survival (Wallace, Carriere, Perrault, Vaughan, & Stein, 2006). Thus, measures of task performance under multisensory conditions show that multiple species can take advantage of the often complementary or redundant sensory information available to them in their environment (Bahrick & Lickliter, 2000; Foxe & Simpson, 2002; Gibson, 1969; Hammond-Kenny, Bajo, King, & Nodal, 2016; Stein, London, Wilkinson, & Price, 1996), allowing them to evolve and adapt to novel ecological niches (Karageorgi et al., 2017). In the case of humans, watching lip and facial movements, hand gestures, head nods, facial configurational (Jaekl, Pesquita, Alsius, Munhall, & Soto-Faraco, 2015) and even feeling the breath of a speaker on your skin (Gick & Derrick, 2009) can all provide additional information to an observer trying to understand what a speaker is saying to them (Ma, Zhou, Ross, Foxe, & Parra, 2009; Ross et al., 2011; Ross, Saint-Amour, Leavitt, Javitt, & Foxe, 2007; Sumby & Pollack, 1954). Even for more basic non-speech stimulus configurations, hearing a sound produced by a visual object is likely to enhance its detectability (Fiebelkorn et al., 2011; Molholm et al., 2002; Van der Burg, Olivers, Bronkhorst, & Theeuwes, 2008). Simply put, through binding of multiple sensory inputs in the nervous system, multisensory integration (MSI) allows one to form higher fidelity representations of the environment, which in turn promote adaptive behavior (Molholm & Foxe, 2010; Stein, 1998).

Congruent multisensory inputs tend to enhance task-relevant performance when compared to circumstances under which solely unisensory input is made available (Giard & Peronnet, 2006; Molholm et al., 2002; Talsma & Woldorff, 2005; Teder-Sälejärvi, McDonald, Di Russo, & Hillyard, 2002) with performance often exceeding linear predictions based on unisensory processing. When these integrative behavioral patterns are observed, they are also generally reflected in nonlinear neural responses, i.e. multisensory integration (MSI) (Beauchamp, Nath, & Pasalar, 2010; Butler, Molholm, Andrade, & Foxe, 2016; Foxe et al., 2000; Foxe & Schroeder, 2005; Meredith & Stein, 1983; Molholm et al., 2002). There are multiple parallel and hierarchically organized processing stages in the brain at which multisensory information may interact to affect sensory-perceptual and motor processes (Driver & Noesselt, 2008; Rohe & Noppeney, 2016), such as stimulus detection, localization, identification, and action planning (Fiebelkorn, Foxe, McCourt, Dumas, & Molholm, 2013; Lucan, Foxe, Gomez-Ramirez, Sathian, & Molholm, 2010; Mercier et al., 2015; Nath & Beauchamp, 2012). An important consideration pertains to the variable timing of neural transmission through the early hierarchical stages of the initially segregated sensory processing streams. Inputs arriving at the separate sensory epithelia (e.g. the skin, the hair cells in the cochlea, the retina) must be “tagged” by the central nervous system as belonging together in the face of varying transmission times from sensory receptors to subcortical regions and on into cortex. In turn, information that is represented in anatomically segregated brain regions must be communicated across significant cortical distances, perhaps involving multisynaptic cascades that propagate across several intervening functional regions, but possibly also via mono-synaptic long-range inter-regional connections (Falchier et al., 2010; Foxe & Schroeder, 2005; Keniston, Henderson, & Meredith, 2010; Rockland & Ojima, 2003). Given the multiple processes that MSI must be built upon, which require long-range network integrity and functionality, it is a reasonable proposition that MSI may be particularly vulnerable to insult. Indeed, MSI has been shown to be impaired in a number of complex neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as dyslexia (Francisco, Jesse, Groen, & McQueen, 2017; Hahn, Foxe, & Molholm, 2014), schizophrenia (Ross, Saint-Amour, Leavitt, Molholm, et al., 2007) and rare lysosomal storage disorders (Andrade et al., 2014), to mention just a few. As we will elaborate below, however, it is ASD in particular that has been most extensively investigated and associated with dysfunction in MSI processing.

Cardinal symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) include deficits in social interaction, and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors (APA, 2013). These are often accompanied by hypo- or hyper- sensitivity to sound, light, and touch (Kanner, 1943; Kern et al., 2006). It has long been proposed, based on clinical evaluations and parental observations, that dysfunction in multisensory integration may be a significant component of the sensory atypicalities and social communication deficits seen in ASD (Ayres & Tickle, 1980; Iarocci & McDonald, 2006; Martineau et al., 1992; Molholm & Foxe, 2010). In what follows, we assess the current state of knowledge regarding MSI in autism, focusing specifically on the impact of development on these processes, and on audiovisual paradigms for which there is a substantial literature. It should be pointed out that these studies all involve individuals with largely normal range IQs (this is often necessary for task performance, and also allows for comparison with a typically developing control group), and thus generalization should be limited to high functioning individuals on the autism spectrum. In turn, we consider how naturally occurring training may serve to improve MSI function in ASD, and how this can be leveraged to shift improvements in function to earlier stages of development. Finally, we forward a possible mechanistic account of altered MSI in ASD. For easy reference, Table 1 presents a list of studies that we cite here on multisensory processing in ASD, along with a brief summary of the study paradigms and major findings.

Table 1:

Paradigms and findings from MSI studies on ASD population. Numbers in Age column represent age range (mean ± std), when available.

| Research | # subjects |

Age (range, mean ± std) |

Stimulus type | Paradigm | Task | MSI effect in ASD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bebko et al. (2006)* | 16-ASD 16-TD |

4.6–6.1 (5.5±0.5) 1.7–4.2 (2.36±0.7) |

Animated AV objects | Preferential looking | No group differences |

| Mongillo et al. (2008)* | 15 ASD 21 TD |

8–19 (13.7±3.9) 11–19 (13.4±2.8) |

Social and nonsocial AV stimuli | Classification; Match-mismatch | Social stimuli: impaired MSI Nonsocial stimuli: No group differences |

| Foss-Feig et al. (2010) | 29 ASD 17 TD |

8–17 (12.6±2.6) 8–17 (12.1±2.2) |

Flashes and beeps | SiFi | Wider TWIN for ASD |

| Russo et al. (2010) | 17 ASD 17 TD |

6–16 (10.4±2.7) 6–16 (10.5±2.9) |

Vibrations and tones | No task | EEG: impaired MSI |

| Kwayke et al. (2011) | 35 ASD 27 TD |

8–17 (12.2±2.7) 8–17 (11.7±2.4) |

Discs and clicks | TOJ | Wider TWIN for ASD |

| Brandwein et al. (2013) | 46 ASD 72 TD |

7–10 (9.2±1.3; 9±1.2) 11–16 (13±1.6; 13.8±1.6) |

Discs and beeps | SD | Both age groups: Behavior: impaired MSI EEG: Reduced neural integration |

| Irwin and Branzcazio (2014)* | 10 ASD 10 TD |

5.6–15.9 (10.2±3.1) 7–12.6 (9.6±2.4) |

Beeps and shapes | Gaze patterns for AV videos | No group differences |

| Brandwein et al. (2014) | 52 (ASD only) | 6–17 (11.2±2.9) | Discs and beeps | SD | Behavior: impaired MSI; EEG: correlation between AV modulation and ADOS scores |

| Stevenson et al. (2014a) | 31 ASD 31 TD |

6–18 (12.1±3.1) 6–18 (11.9±2.9) |

Flashes and beeps | SiFi | Greater susceptibility to the SiFi |

| Stevenson et al. (2014b)* | 32 ASD 32 TD |

6–18 (11.8±3.2) 6–18 (12.3±2.3) |

Flashes and beeps Tools | SJ | No difference in TWIN for non-speech stimuli |

| Noel et al. (2016)* | 26 ASD 26 TD |

7–17 (12.3±3.1) 8–17 (11.6±3.8) |

Flashes and beeps Tools | SJ | Wider TWIN; Impaired recalibration |

| Van der Smagt et al. (2007) | 15 ASD 15 TD |

20.5±3.2 20.7±2.6 |

Flashes and beeps | SiFi | No group differences |

| Keane et al. (2010)* | 6 ASD 6 TD |

19–47 (30±9) 18–49 (30±8) |

Flashes and beeps | Cross-modal dynamic capture; SiFi | No group differences |

| De Boer-Schellekens et al., (2013) | 35 ASD 40 TD |

15–24 (18.8±2.1) 15–24 (18.8±1.3) |

Clicks and flashes | Pip and Pop Digital clock reading task |

No group differences |

| Collignon et al. (2013) | 19 ASD 20 TD |

14–31 (24.5±5) 14–27 (21±4) |

Lines and tones | Pip and Pop | No group differences |

| Poole et al. (2016) | 18 ASD 18 TD |

31±8.4 31±8.7 |

Vibrations, beeps, flashes | TOJ | No group differences for size of JND and PSS in any modality pairing |

| Turi et al. (2016) | 16 ASD 16 TD |

17–34 (29.2±5.2) 18–31 (27±2.8) |

Flashes and beeps | SD | No group differences for TWIN No recalibration |

| Bao et al. (2017) | 20 ASD 20 TD |

13–29 (18.7±4.7) 13–28 (18±9.5) |

Flashes and beeps | SiFi | No group effect on fission illusion Larger susceptibility to the fusion illusion |

| Speech Stimuli | |||||

| de Gelder et al. (1991) | 17 ASD 17 TD |

6.5–16.3 (10.9±2.3) 6.8–11.1 (8.5±1.3) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived. | Reduced MSI |

| Williams et al. (2004) | 15 ASD 15 TD |

5–13 (8.8±1.4) 5–13 (9.5±1) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | No difference when corrected for visual only |

| Bebko et al. (2006)* | 16 ASD 16 TD |

4.6–6.1(5.5±0.5) 1.7–4.2(2.36±0.7) |

AV speech | Preferential looking | Impaired MSI: altered gaze patterns |

| Smith and Bennetto (2007) | 18 ASD 19 TD |

12.4–19.5 (15.8±2.2) 12–19.2 (16±2) |

AV Speech in noise | Speech in noise | Impaired MSI |

| Mongillo et al. (2008)*. | 15 ASD 21 TD |

8–19 (13.7±3.9) 11–19 (13.4±2.8) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived. | Impaired MSI |

| Silverman et al. (2010) | 19 ASD 20 TD |

12–18 (15.3±0.5) 12–18 (15.2±0.4) |

AV Speech and gestures | Speech-and-Gesture | Reduced multisensory benefit for gestures |

| Taylor et al. (2010) | 24 ASD 30 TD |

7.9–16.4 (12.6±2.4) 8.3–16.4 (11.8±2.5) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | Impaired MSI of speech at young age; Amelioration over age for ASD group |

| Irwin et al. (2011) | 13 ASD 13 ASD |

5–15 (9.1) 7–12 (9.2) |

AV consonant-vowel syllables | Lip-reading; Speech in noise; McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | Lip-reading: impaired performance for ASD Speech in Noise: No group differences McGurk: Impaired MSI in ASD |

| Woynarosky et al. (2013) | 18 ASD 18 TD |

8–17 (12.3±2.6) 8–17 (11.5±1.9) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | No group effect on McGurk; Wider TWIN (marginal effect) |

| Irwin and Branzcazio (2014)* | 10 ASD 10 TD |

5.6–15.9 (10.2±3.1) 7–12.6 (9.6±2.4) |

AV consonant-vowel syllables | Speech in Noise; gaze patterns | Altered gaze patterns for ASD in multisensory conditions |

| Bebko et al. (2014) | 15 ASD 19 TD |

6.6–14.6 (10.5±2.5) 6–15.6 (10.2±2.7) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | Impaired MSI |

| Stevenson et al. (2014b)* | 32 ASD 32 TD |

6–18 (11.8±3.2) 6–18 (12.3±2.3) |

McGurk | SD | Wider TWIN for ASD |

| Foxe et al. (2015) | 84 ASD 142 TD |

5–6 (6; 5.6) 7–9 (8±0.9; 8±0.6) 10–12 (11.4±0.7; 10.9± 0.8) 13–15 (14.1±0.8; 13.4 ±0.7) 16–17 (16.7±0.5; 16.8 ±0.5). |

AV Speech in noise | Speech in noise; repeat the perceived words | Impaired MSI in the 7–9 group Full resolution in the 13–15 group |

| Noel et al. (2016)* | 26 ASD 26 TD |

7– 17 (12.3±3.1) 8– 17 (11.6±3.8) |

AVconsonant-vowel syllables | SD | No group differences |

| Keane et al. (2010)* | 10 ASD 9 TD |

19–47 (30±9) 18–49 (30±8) |

McGurk | McGurk illusion: report which syllable was perceived | No group differences |

| Children and adolescents (<18) |

| Adults (>18) |

| Mixed age group |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; TD, typically developed; MS multisensory; SiFi, Sound Induced Flash Illusion; TWIN, time window of integration; JND, Just Noticeable Difference; PSS, Point of Subjective Simultaneity; SOA, Stimulus Onset Interval; SD, Speeded Detection; A, auditory; V, visual; AV, audiovisual; TOJ, temporal order judgment; SJ, Simultaneity judgment; JND, just noticeable difference; EEG, encephalogram;

Studies that use both Speech and Non-speech stimuli, and appear in both sections in the table

1.1. Multisensory integration in autism: A developmental perspective

The development of multisensory processing and integration has been meticulously investigated in animal models, primarily through electrophysiological recordings in the superior colliculus (SC; see (Meredith & Stein, 1983). This midbrain structure is involved in rapid orienting responses, and contains both bisensory and trisensory neurons that receive combinations of auditory, visual, and somatosensory inputs (Meredith & Stein, 1986). From these studies, we have learned that the organism’s specific experiences with the multisensory environment significantly influence the development of MSI. For example, while there are neurons present in the SC at birth that respond to more than one channel of sensory input, these cells do not initially show integrative, non-linear, responses. Rather, MSI properties develop only after experience with multisensory cues has been gained (Wallace, Perrault, Hairston, & Stein, 2004; Wallace & Stein, 1997, 2001; Wallace & Stein, 2007). Wallace and Stein (2007) provided a particularly powerful example of environmental influences on the development of MSI, showing how the natural spatial overlap of multisensory SC receptive fields for the different sensory modalities can be dramatically influenced through manipulations of the post-natal environment. Animals were raised in a sensory environment where the only auditory and visual stimuli they were exposed to, while temporally coupled, were spatially displaced from each other in a consistently mapped fashion. This led to massively altered functionality of the SC audiovisual neurons since they developed mismatched auditory and visual spatial fields such that only stimulation of the spatially disparate visual and auditory mappings generated integrative responses (Wallace & Stein, 2007).

Based on abundant evidence for early plasticity of the multisensory system in animal models, it is not surprising that developmental studies in humans also show that extensive experience is necessary before the nervous system can fully benefit from multisensory cues. Sensitivity to temporal coincidence of rhythmic audiovisual stimuli, and to the congruency of native audiovisual speech stimuli, appear to emerge already within the first year of an infant’s life (Lewkowicz, 1996; Lewkowicz, 2003; Pons, Lewkowicz, Soto-Faraco, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2009). Yet, multisensory influences on perception and performance are nevertheless greatly reduced in young children when compared to adolescents and young adults (Brandwein et al., 2011; Burr & Gori, 2012; Ernst, 2008; Gori, Sandini, & Burr, 2012; Ross, Del Bene, Molholm, Frey, & Foxe, 2015; Ross et al., 2011) (Cowie, Makin, & Bremner, 2013; Cowie, Sterling, & Bremner, 2016) (Greenfield, Ropar, Themelis, Ratcliffe, & Newport, 2017). Several psychophysics studies found that children younger than eight years of age do not optimally integrate haptic and visual cues, but instead that prior to that point, one sense dominates the other, depending on the specific task demands (Gori, 2015; Gori, Del Viva, Sandini, & Burr, 2008; Gori et al., 2012). This protracted plasticity of multisensory processing may enable the flexible use of multisensory information. For example, the child can learn to integrate multisensory speech cues that are specific to their native language (Lewkowicz, 2014), and individuals readily adapt to changes in body schema to effectively interact with objects in their environment (Cardinali, Brozzoli, & Farne, 2009).

Given the prolonged trajectory of the development of multisensory processing and the extensive influence of the environment on MSI operations, MSI deficits in ASD may be best understood in a developmental context. Here we focus on audiovisual MSI in ASD, where the bulk of the relevant studies are found. We note that it is likely that the developmental course of multisensory processing, and how it is impacted in ASD, will differ somewhat as a function of the sensory modalities and the specific processes under consideration.

1.1.1. Multisensory integration of audiovisual speech

Deficits in language and socio-emotional processing are canonical symptoms of autism (APA, 2013). Audiovisual speech is a particularly rich and natural occurring multisensory signal that conveys both linguistic and extra-linguistic (including social and emotional) information, and thus it is not surprising that many studies of MSI in ASD have focused specifically on the integrity of audiovisual speech perception (Bebko, Weiss, Demark, & Gomez, 2006; Irwin & Brancazio, 2014; Kujala, Lepisto, Nieminen-von Wendt, Naatanen, & Naatanen, 2005; Paul, Augustyn, Klin, & Volkmar, 2005; Silverman, Bennetto, Campana, & Tanenhaus, 2010; Smith & Bennetto, 2007). In general, these studies have demonstrated multisensory speech deficits in children with autism. For example, in a cross-sectional study performed by our group (Foxe et al., 2015), we assessed the development of multisensory speech perception in individuals with and without ASD, from 7 to 19 years of age. Spoken monosyllabic words were presented in varying degrees of background noise, making them difficult to identify, and the benefit of an accompanying video of the speaker saying the word was then assessed. In this audiovisual speech-in-noise paradigm, younger children with ASD (7–12 year olds) showed severe deficits in multisensory speech perception when compared to controls (see also (Irwin, Tornatore, Brancazio, & Whalen, 2011; Stevenson et al., 2017)). Crucially, although identification of the auditory-alone words was essentially equivalent between the ASD and TD groups (i.e. unisensory processing appeared to be largely intact), individuals with ASD simply did not benefit from the addition of the video to the same extent as controls. However, these multisensory deficits were not observed in the older age group (13–15 year olds), suggesting a relative amelioration of audiovisual speech integration by the teenage years. In typical development there is a progressive increase in the integration of audiovisual information to enhance speech perception (Ross et al., 2011). The findings of Foxe and colleagues suggest a similar, albeit significantly delayed, developmental increase in the ability to benefit from multisensory inputs in children with autism. Interestingly, while Stevenson and colleagues (2017) also found MSI deficits in ASD at the whole word level for a group of 6 to 18 year olds, when they instead considered the number of phonemes correctly identified, MSI gain did not significantly differ between ASD and control groups. The absence of group differences in multisensory gain at the phonemic level of analysis might suggest that such multisensory deficits are only seen for higher levels of speech processing, where lexical information is relevant. This explanation, however, is not consistent with data from the so-called McGurk speech illusion, described below, in which reduced MSI in children with autism is found for phonemic-level inputs.

In the McGurk illusion, mismatched auditory (phonemes) and visual (visemes) speech components are presented and an illusory speech sound is perceived (McGurk & Macdonald, 1976; Saint-Amour, De Sanctis, Molholm, Ritter, & Foxe, 2007). By manipulating the congruency between the visual and the auditory stimuli, the resultant percept is often a fusion of the two stimuli (for example, hearing the syllable /ba/ while watching the visual lip movements of /ga/, usually results in the person perceiving the phoneme /da/). In typical development, the strength of this illusion increases with age (Hockley & Polka, 1994; Tremblay et al., 2007), presumably due to increased multisensory influences on speech perception. In children with ASD, the McGurk effect has been found, in the majority of cases, to be significantly reduced compared to age matched TD controls (Bebko, Schroeder, & Weiss, 2014; De Gelder, Vroomen, & Van der Heide, 1991; Iarocci, Rombough, Yager, Weeks, & Chua, 2010; Irwin et al., 2011; Mongillo et al., 2008; Williams, Massaro, Peel, Bosseler, & Suddendorf, 2004; Woynaroski et al., 2013). Taylor and colleagues examined patterns of responses to McGurk stimuli (Taylor, Isaac, & Milne, 2010) in children and adolescents with and without a diagnosis of autism. They found that McGurk illusions were reduced in younger children with ASD (7–14 year olds) but that adolescents with ASD performed similarly to the control group (15–16 year olds). Similarly, Stevenson et al. 2014 examined the McGurk illusion in a group of children and adolescents, and found reduced McGurk illusions in their ASD sample. However, when the data were separated into two age groups, the pattern of findings contrasted somewhat with those of Taylor and colleagues, with significantly fewer McGurk Illusions observed in the older ASD vs. TD group (13–18 year olds), and no statistically reliable group difference in their younger group (6–12 year olds). It is not clear what accounts for this difference in developmental findings across studies. However, consistent with Taylor and colleagues (2010) finding, McGurk illusions did not differ significantly between the ASD and control groups in adults (Keane, Rosenthal, Chun, & Shams, 2010).

Overall, findings from both the audiovisual speech-in-noise and the McGurk studies argue for substantially reduced multisensory influences on speech perception in children with ASD, with amelioration of deficits by adolescence/early adulthood. Of major interest is what drives this change. One possibility is that exposure to multisensory speech, which can be reasonably assumed to occur daily, serves to train the MSI function over time, eventually leading to recovery of function in ASD. A critical point here is whether the same trend is observed using non-speech stimuli, such as objects and simple beeps and flashes. If a similar resolution of MSI function occurs for other types of stimuli where similar levels of exposure cannot be assumed, then a non-specific mechanism may lead to the developmental recovery of multisensory processing in ASD. For instance, the strengthening of connectivity between frontal and sensory cortices that occurs throughout adolescence (Simmonds, Hallquist, Asato, & Luna, 2014), or the extensive therapies that individuals with autism frequently receive (Pickles et al., 2016), could play a role in how multisensory information is processed.

1.1.2. Multisensory integration of audiovisual non-speech stimuli

Speech and communication are specifically impaired in autism and thus might have a unique status in the developmental delay of MSI. However, studies using non-speech stimuli to test MSI in ASD have also, for the most part, found deficits in MSI in children. Multisensory integration in this domain can be assessed by testing whether an interactive or independent processing model better explains response time facilitation to redundant multisensory cues. In the non-interactive model (Miller, 1982; Raab, 1962), each stimulus of the auditory and visual pair is assumed to independently compete for response initiation, with the faster of the two mediating the response. In the interactive model (Miller, 1982; Molholm et al., 2002; Raab, 1962), an interaction between the inputs leads to enhancement of the reaction to the multisensory stimuli. If simple probability summation of the fastest responses from each of the unisensory conditions (i.e., the non-interactive model) cannot account for the response speeding, it is assumed that the inputs interacted to enhance the response to the multisensory stimulus. Using this approach, we examined the development of multisensory processing in ASD. Tone and flash stimuli were presented in unpredictable order either alone or in combination, resulting in audio alone, visual alone, and audiovisual stimuli. Participants performed a simple detection task in which they were instructed to respond with a speeded button press whenever any of the three stimulus types (auditory/visual/audiovisual) occured. In typically developing children, behavioral multisensory effects increased as a function of age. In contrast, these multisensory effects were not present in either the younger or older group of children with ASD. Congruently, neural indices of MSI were reduced in both the younger (7–10 year olds) and the older (11–16 year olds) children with ASD, and this was correlated with autism severity (Brandwein et al., 2015; Brandwein et al., 2013). Thus, impaired MSI in ASD is not exclusive to socially relevant speech stimuli. Preliminary analysis of behavioral data from a larger cohort of ASD and TD, using the same paradigm, replicates the finding that MSI effects are delayed in children with ASD, and further suggests that adults with autism show largely typical MSI effects (Crosse, Foxe, & Molholm, 2017).

Experiments using a paradigm known as the sound-induced flash illusion (SiFi) have also shown impaired MSI in children and adolescents with ASD for non-speech stimuli. In this illusion, a single flash is accompanied by two successive tones, and observers tend to report seeing two visual flashes, rather than the physical one (Mishra, Martinez, Sejnowski, & Hillyard, 2007; Shams, Kamitani, & Shimojo, 2000, 2002). This illusion is considered a consequence of how the sensory systems communicate to enhance information processing, with cross-sensory inputs decreasing the threshold for an evoked response (Mishra et al., 2007). Children with ASD show reduced susceptibility to this illusion relative to TD controls, with fewer reports of illusory flashes (Stevenson, Siemann, et al., 2014). Adults with autism, however, appear to be equally susceptible to the illusion when compared to controls (Bao, Doobay, Mottron, Collignon, & Bertone, 2017; Keane et al., 2010; Van der Smagt, Van Engeland, & Kemner, 2007) implying once again that multisensory processing is operating in a largely typical manner in adults with autism.

The findings described above are consistent with MSI resolution over age representing a general phenomenon in ASD, rather than one that is specific to audiovisual speech. There are exceptions, however, where impaired MSI is reported in adults with ASD. One example comes from the “pip-and-pop” paradigm (Van der Burg et al., 2008). Here, presentation of a temporally relevant sound (a pip) facilitates performance on a visual search task, such that the visual target pops out of a cluttered visual display. The two studies that have used this paradigm in adults with ASD report contradictory results, however. While (Collignon et al., 2013) found significant group differences due to a lack of auditory-based facilitation in their adult ASD group, De Boer-Schellekens and colleagues (De Boer-Schellekens, Keetels, Eussen, & Vroomen, 2013) found equivalent facilitatory effects across adult ASD and control groups. In Collignon et al. (2013), the ASD group performed at superior levels on the visual alone condition of the task, such that performance resembled that of the control group under the multisensory condition. Individuals with ASD sometimes exhibit superior performance on visual search tasks (Shah & Frith, 1983; Shirama, Kato, & Kashino, 2016), and it is possible that this superior performance here is what accounts for the lack of an auditory facilitatory effect in Collignon et al. (2013); that is, that there was a ceiling effect of sorts. Further investigation is necessary to understand the possible role of methodological differences between the studies in accounting for the presence or absence of multisensory effects in the pip-and-pop paradigm.

Another, perhaps more compelling, example is found in studies measuring the so-called multisensory temporal window of integration (TWIN). Normally, the brain tolerates subtle time lags between the onsets of auditory and visual stimuli, perceiving stimuli that arrive asynchronously as synchronous. This tolerance may be necessary due in part to the different propagation speeds of light and sound vibrations (Mégevand et al., 2013), arriving at the retina (Berry, Brivanlou, Jordan, & Meister, 1999; Mauncell & Gibson, 1992) and hair cells (Corey & Hudspeth, 1979), respectively. Further, the different neural response latencies (Bushara, Grafman, & Hallett, 2001) and number of processing stages (Foxe & Schroeder, 2005) are also likely to contribute to timing variability in the convergence of multisensory inputs to a given region (Molholm et al., 2006). The TWIN is most often measured using temporal order judgment (TOJ) tasks in which participants are presented with two sources of sensory stimulation, such as tones and flashes, separated by a range of stimulus onset asynchronies, and are then asked to judge their simultaneity, or, alternatively, their temporal order (i.e., “Which came first, the auditory or the visual stimulus?”). Of relevance here, these judgments are influenced by the degree and direction of asynchrony between the stimuli on the previous trials (Fujisaki, Shimojo, Kashino, & Nishida, 2004; Vroomen, Keetels, de Gelder, & Bertelson, 2004). On average, a few minutes of exposure to an audiovisual pair with a fixed time lag (on the order of ~200ms) leads to a shift in simultaneity judgments such that larger lags are tolerated, relative to exposure to simultaneous stimuli (Fujisaki et al., 2004). This “lag adaptation” is also shown on a trial-to-trail basis such that exposure to asynchrony on one trial leads to greater tolerance of the same order asynchrony on the next trial (Van der Burg, Alais, & Cass, 2013).

Two studies have recently shown that individuals with ASD lack this rapid multisensory temporal recalibration, and do not adjust simultaneity judgments as a function of the temporal order of the stimuli on the previous trial. This failure to recalibrate the multisensory temporal window of integration on a trial-by-trial basis has been shown for both children and adolescents with ASD (Noel, De Niear, Stevenson, Alais, & Wallace, 2017), as well as for adults (Turi, Karaminis, Pellicano, & Burr, 2016), using simple, non-speech, stimuli. Notably, this same lack of adaptation has been shown in the ASD population with tasks involving complex stimuli like numbers (Pellicano, Jeffery, Burr, & Rhodes, 2007; Turi et al., 2015) and faces (Pellicano et al., 2007), as well as more simple scenarios such as loudness changes (Lawson, Aylward, White, & Rees, 2015). As such, we believe it likely that these findings reflect impaired rapid online adaptation/recalibration, rather than impaired MSI, in ASD. This adaptive impairment may operationalize a prominent feature in the clinical picture of ASD: reduced adaptation to new environments and situations, leading to distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, and rigid thinking patterns (APA, 2013), although this clearly remains to be specifically tested experimentally.

Thus far we see that multisensory processing is impaired in children with ASD for both speech and non-speech stimuli. The weight of the evidence points to substantively intact multisensory abilities in adults with ASD for speech, whereas exceptions were found in paradigms using non-speech stimuli. One possibility is that MSI normalization in the speech domain is more robust than in non-speech areas, due to daily exposure to speech. Alternatively, these exceptions may reflect altered functioning in other information processing domains, such as temporal recalibration or visual search.

1.1.3. A potential role for adaptation/recalibration in MSI development

It has been proposed that a lack of MSI in young children may be a result of a continual sensory calibration process in the developing brain (Gori, 2015). According to this idea, during the sensory calibration period in childhood, the less accurate senses are calibrated by the more accurate sense for a given type of information (e.g., size estimates), and the redundancy in multisensory information is only translated to enhancement once this process is completed. The instantaneous calibration processes referred to above may share similar elements with this hypothesized developmental calibration, such as modification of a decision criterion after feedback. Impaired MSI in ASD might reflect one aspect of impaired inter-sensory calibration in this population. Given this scenario, appropriate training focused on adjustment to changes in multisensory surroundings could be useful to improving adaptation to new environments in autism, and might have positive consequences for other daily functions.

1.1.4. Multisensory stimuli and the temporal window of integration

Studies on the multisensory TWIN (described above), while not directly testing MSI, nevertheless pertain to the operations underlying MSI. The size of the temporal window within which multisensory stimuli are judged to occur simultaneously is often taken as the interval within which stimuli are integrated. Many studies have used the TWIN to examine the development of multisensory processing, and to consider the integrity of MSI in clinical populations. The multisensory TWIN has been measured in ASD in several studies now, using both speech and non-speech stimuli. When differences are found, individuals with ASD tend to exhibit a wider multisensory TWIN (De Boer-Schellekens et al., 2013; Foss-Feig et al., 2010; Kwakye, Foss-Feig, Cascio, Stone, & Wallace, 2010; Noel, De Niear, Stevenson, Alais, & Wallace, 2016; Noel et al., 2017). Such differences are typically taken to indicate reduced multisensory temporal acuity that in turn leads to less reliable binding. Indirect support for this thesis comes from Stevenson and colleagues (Stevenson, Siemann, et al., 2014), where the percent of illusory McGurk responses negatively correlated with the width of the temporal window for binding simple audiovisual stimuli among children and adolescents with autism. However, the literature is inconclusive as to whether the multisensory TWIN in children and adolescents with ASD differs from typically developing controls. For non-speech stimuli, sometimes group differences are found (De Boer-Schellekens et al., 2013; Foss-Feig et al., 2010; Kwakye et al., 2010; Stevenson, Siemann, Schneider, et al., 2014), whereas other times they are not (Noel et al., 2017; Smith, Zhang, & Bennetto, 2017; Stevenson et al., 2017). Interestingly, two of the four studies that failed to show group differences in TWIN for non-speech stimuli, showed group differences for conditions in which speech stimuli were instead presented (Noel et al., 2017; Stevenson, Siemann, et al., 2014).

In the only multisensory TWIN studies that have been conducted in adults with ASD, both of which used non-speech stimuli, judgments of temporal order for multisensory inputs were comparable between ASD and TD participants (Poole, Gowen, Warren, & Poliakoff, 2016; Turi et al., 2016). However, in the absence of clear TWIN differences in children and adolescents, this cannot be taken to support a developmental shift in MSI function in ASD (Poole et al., 2016; Turi et al., 2016). In all, while intriguing, we find the data on the multisensory TWIN in ASD to be somewhat inconclusive at this point.

1.2. Can we accelerate the recovery of MSI function in ASD?

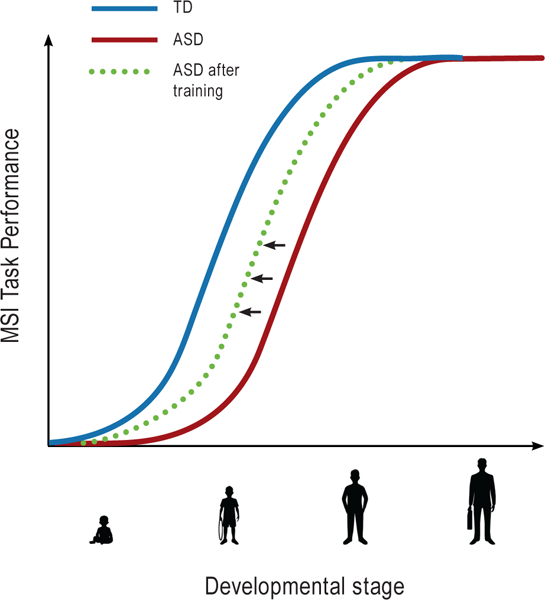

The apparent amelioration of MSI deficits over the course of development in the ASD population raises the promise that controlled manipulations and educational strategies could be deployed to shift MSI recovery to earlier stages of development. Importantly, if MSI is intact at developmentally critical stages, it could positively impact the emergence of a range of functions in ASD that have been shown to be impaired, such as verbal communication. One approach to improving MSI function might be through engagement with multisensory perceptual learning tasks starting at a young age. We already know that the temporal discrimination of multisensory stimuli, which is correlated with MSI performance in ASD (Stevenson, Siemann, Schneider, et al., 2014) can be enhanced with training, and that such training effects can last for at least one week (Powers, Hillock, & Wallace, 2009). Additional support for the efficacy of audiovisual training comes from studies in which the outcome measures is improvement in unisensory perception. For example, after training on an audiovisual matching task using shape and sound sequences, 7-year-old children with dyslexia showed improvement in reading tasks, accompanied by enhanced brain reactions as measured by EEG (Kujala et al., 2001). Multisensory training was also found to ameliorate haemianopia, i.e blindness in half the visual field, in animals with visual cortex ablation (Jiang, Stein, & McHaffie, 2015). Following lesion-induced contralateral haemianopia, the animals repeatedly performed a task in which they oriented to and approached a salient auditory cue presented to the anopic hemifield. Critically, the auditory cue was always accompanied by a task-irrelevant spatially and temporally coincident visual stimulus. Within several weeks, this caused the animal to orient to the visual cue when it was presented alone. This recovery of visuomotor function was linked to training-induced alterations to inputs from lesion-spared regions of visual association cortex to audiovisual SC orienting neurons (Jiang et al., 2015). Applied in human patients with haemianopia, similar principles of MSI training have been shown to lead to improvements in responses to stimuli in the haemianopic field (Dundon, Làdavas, Maier, & Bertini, 2015). Recent work suggests that such training effects may be specific to spatially coordinated multisensory training stimuli, and that some neural systems may be more easily trained with AV stimuli than others (Grasso, Benassi, Làdavas, & Bertini, 2016). Based on the sum of these compelling findings, MSI-oriented training in children with ASD seems to offer real promise for accelerating the improvement in MSI function that occurs naturally over the course of typical development. For a schematic of audiovisual MSI development in TD and ASD and the effects of training on this trajectory in ASD, see Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Developmental delay in Multisensory Integration (MSI) tasks in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Psychometric developmental curve for MSI performance is altered for individuals with ASD (red curve), compared to individuals with Typical Development (TD; blue curve). While MSI in TD approaches mature levels around adolescence (Brandwein et al., 2011; Gori et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2011), MSI is delayed in individuals with ASD, who usually do not perform comparably to TD before adulthood (Foxe et al., 2015; Irwin et al., 2011; Foss-Feig et al., 2010; Taylor et al, 2010). Behavioral training starting at a young age can potentially shift the amelioration of MSI performance earlier (dashed green curve).

A different approach to remediating MSI function is through closed-loop neurofeedback and/or neurostimulation. Given that atypical neural activity necessarily underlies reduced multisensory processing among individuals with ASD, there is the possibility that this activity can be normalized through appropriate tools. In closed-loop neurofeedback, on-line adaptive changes of an experimental task are made in real time on the basis of neural activity (Sitaram et al., 2017). Indeed, studies indicate that through neurofeedback, an individual can modulate their ongoing neuronal activity, and in turn, the corresponding functions, including attention (deBettencourt, Cohen, Lee, Norman, & Turk-Browne, 2015), perceptual learning (Shibata, Watanabe, Sasaki, & Kawato, 2011), and other forms of learning (for review see Sitaram et al. 2016). A recent study used neurofeedback training in high functioning adolescents with ASD (Datko, Pineda, & Muller, 2017) to try to selectively increase the motor cortex generated mu rhythm (9–13 Hz). This led to greater activation of sensorimotor areas, as shown in fMRI data collected before and after training. Non-invasive neurostimulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), are also gaining traction for their potential to enhance behavioral and motor training effects and possibly generalize to the processes (e.g., working memory or selective attention) underlying the task being trained (Buch et al., 2017; Looi et al., 2016). The optimal conditions for neuromodulatory stimulation have yet to be established, and there is much ongoing debate regarding the efficacy of the approach (Horvath, Carter, & Forte, 2016; Horvath, Forte, & Carter, 2015; Horvath, Vogrin, Carter, Cook, & Forte, 2015). Nevertheless, successful implementations in clinical (Brunelin et al., 2012; Brunoni et al., 2013) and healthy (Snowball et al., 2013) populations are reported, and there are well-controlled experiments showing lasting effects that generalize beyond the task explicitly trained on (Looi et al., 2016). To effectively apply biofeedback or neurostimulation to boost MSI in individuals with ASD, recognizing specific rhythmic electrophysiological properties in MSI processes will be critical (Giordano et al., 2017; Goschl, Friese, Daume, Konig, & Engel, 2015; Mercier et al., 2013; Mercier et al., 2015; Senkowski et al., 2007).

1.3. Neuro-oscillatory mechanisms and their potential role in MSI impairment

In recent years, significant steps have been made toward understanding the role of neuronal rhythms in perceptual and cognitive processes (Buzsáki, Anastassiou, & Koch, 2012; Foxe, Simpson, & Ahlfors, 1998; Foxe & Snyder, 2011; Schroeder, Wilson, Radman, Scharfman, & Lakatos, 2010; Singer & Gray, 1995; Thut, Miniussi, & Gross, 2012; Varela, Lachaux, Rodriguez, & Martinerie, 2001). External stimuli can reset the phase of ongoing neuronal oscillations, with phase reset optimizing neural excitability so that sensory areas of the cortex are more receptive when relevant stimuli are expected (Gomez-Ramirez et al., 2011; Lakatos, Karmos, Mehta, Ulbert, & Schroeder, 2008). Furthermore, synchronization between different sensory areas in the cortex is considered to facilitate information transmission (Kaiser et al., 2016; Lakatos et al., 2009; Senkowski et al., 2007), promoting multisensory communication (Mercier et al., 2013) and impacting behavioral outcomes (Fiebelkorn et al., 2011; Mercier et al., 2015). Sensory inputs have been shown to phase-reset on-going neuronal oscillations in low-level cross-sensory areas (Lakatos, Chen, O’Connell, Mills, & Schroeder, 2007; Mercier et al., 2015; Schroeder & Foxe, 2005). For example, auditory stimuli can reset the phase of oscillations in the visual cortex (Fiebelkorn et al., 2011; Lakatos et al., 2009; Mercier et al., 2013; Romei, Gross, & Thut, 2012). More generally, cross-sensory inputs reset ongoing cortical activity such that the local response to a region’s primary input is enhanced (Foxe & Schroeder, 2005; Lakatos et al., 2007; Lakatos et al., 2005) and may also serve to trigger inter-regional coherence (Mercier et al., 2015; Sehatpour et al., 2008).

Several groups have suggested that impaired neuro-oscillatory functions may play a significant role in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism (Brock, Brown, Boucher, & Rippon, 2002; Brown, Gruber, Boucher, Rippon, & Brock, 2005; David et al., 2016; Murphy, Foxe, Peters, & Molholm, 2014; Simon & Wallace, 2016; Uhlhaas & Singer, 2012). Arguably, even small perturbations in the synchronization of oscillations across cortical areas would lead to deficits in MSI, such as those observed in children with ASD. While there is a dearth of studies examining oscillations in the context of multisensory processing in ASD, evidence of altered oscillatory activity in this population can be found in the unisensory literature. Neural oscillations are usually parsed into the delta (~1.5–4 Hz), theta (~4–8 Hz), alpha (~8–14 Hz), beta (~14–30 Hz), and gamma (~30–200 Hz) frequency bands. In the context of sensory processing, gamma band perturbations in autism have been, perhaps, most commonly observed. Gamma activity is often associated with the perceptual binding of information (Desmedt & Tomberg, 1994; Gray & Singer, 1989; Tallon-Baudry, Kreiter, & Bertrand, 1999). Visually-dependent gamma activity was altered in children and adults with ASD in studies using simple visual stimuli (Milne, Scope, Pascalis, Buckley, & Makeig, 2009; Snijders, Milivojevic, & Kemner, 2013), but even more so using complex stimuli such as faces (Grice et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2012), pictures (Buard, Rogers, Hepburn, Kronberg, & Rojas, 2013), and visual illusions (Stroganova et al., 2012). Reduced gamma synchronization was also found for auditory-evoked activity, again using simple stimuli such as pure tones (Edgar et al., 2015; Gandal et al., 2010; Rojas, Maharajh, Teale, & Rogers, 2008). Gamma band atypicalities are sometimes interpreted as reflecting an excitatory/inhibitory imbalance among inhibitory interneurons, due to disturbance of GABAergic function (Bozzi, Provenzano, & Casarosa, 2017; Brown et al., 2005; Port et al., 2017; Rubenstein & Merzenich, 2003.) Alterations in the generation of alpha-band (8–14 Hz) oscillatory activity have also been observed in ASD and have been associated with altered sensory and attentional functioning. Alpha band activity is often associated with visual processing and attentional processes (Adrian & Matthews, 1934; Foxe & Snyder, 2011; Klimesch, Doppelmayr, Russegger, Pachinger, & Schwaiger, 1998), and with the inhibition of task irrelevant sensory information (Foxe et al., 1998; Foxe & Snyder, 2011; Kelly, Gomez-Ramirez, & Foxe, 2009; Worden, Foxe, Wang, & Simpson, 2000). Some examples of atypical alpha activity in ASD include the observation of altered phase locking in alpha band to photic stimulation (Lazarev, Pontes, & De Azevedo, 2009), higher alpha power in ASD to high-spatial frequency stimuli (Milne et al., 2009), and reduced alpha-band attentional suppression mechanisms in the context of visuospatial (Keehn, Westerfield, Müller, & Townsend, 2017) and intersensory (Murphy et al., 2014) attention tasks. In addition, the sensory-motor mu rhythm (9–13Hz in humans), which is desynchronized during both the execution and the observation of motor behaviors (Pfurtscheller, Brunner, Schlögl, & Lopes da Silva, 2006), does not always modulate in ASD during observed motor action ((Bernier, Dawson, Webb, & Murias, 2007; Dumas, Soussignan, Hugueville, Martinerie, & Nadel, 2014) but see (Hobson & Bishop, 2017) review for significant methodological concerns regarding the use of this paradigm).

Based on these indications of impaired oscillatory activity in individuals with ASD, a central question is whether impairments in MSI in autism, and specifically integration from distant sensory areas, stem from compromised cross-sensory phase reset or, possibly, from other impaired oscillatory functions in the ASD brain. If the phase of neuronal oscillations indeed plays a critical role in sensory integration, then even a subtle disturbance to the coordination of inter-regional phase relationships might lead to malfunctions in information processing. Figure 2 conveys this mechanistic model, in which inter regional connections are weaker in the ASD brain, which results in non-synchronous intersensory activity. Advanced stages of processing such as multisensory integration might be more impacted than basic processing of sensory features. These potential cascading effects would likely have implications for the development of many of the cognitive abilities typically impaired in individuals with ASD. This would of course include communication, which requires coordinated activity across a vast network of cortical regions.

Figure 2:

Proposed model for MSI deficits in ASD. Typical reaction to multisensory stimuli, such as speech, is enhanced due to inter-regional phase alignment of neuro-oscillations (Mercier et al, 2015). Reduced MSI effects in children with ASD is possibly related to reduced interregional communication (Di Martino, 2014; Weng et al., 2010; Long et al., 2016) and, in turn, impaired phase alignment of neuro-oscillations.

An open question is whether impaired oscillatory processes could be repaired through intervention in ASD. Typically, inter-regional functional connectivity strengthens over development through the maturation of white matter connections and through experience, which parallels gains in cognitive ability (Simmonds et al., 2014). As a result, functional networks become less localized and more distributed, and consequently, connectivity becomes stronger among distant anatomical regions (Fair et al., 2009). In individuals with autism, however, widespread disruptions of white matter microarchitecture have been found in long-range fibers (Koolschijn, Caan, Teeuw, Olabarriaga, & Geurts, 2017), which is in line with under-connectivity of long range circuits suggested by functional measures (Assaf et al., 2010; Di Martino et al., 2014; Long, Duan, Mantini, & Chen, 2016; Weng et al., 2010). Reduced connectivity in autism, in turn, could lead to a perturbation in long range signaling, resulting in altered synchronization between the relevant areas. Suboptimal integration would be one result. Based on such a model, resolution of MSI in ASD could be the outcome of increased network connectivity due to naturally occurring developmental changes in connectivity, and/or following interventions such as those described above, and subsequent strengthening of the longer-range pathways.

Summary and Discussion

Multisensory information that arrives simultaneously to the various sensory organs typically leads to enhancement in processing and behavior. This enhancement is usually promoted by inter-regional communication: synchronized oscillations of cortical activity between different brain regions. While the typical brain develops in a way that facilitates reaction to stimuli through network-level inter-regional communication, this facilitation may well be altered in children and young adolescents with ASD, as seen in a corpus of studies involving stimuli with different degrees of complexity.

Based on several studies that specifically looked at MSI in ASD as a function of development, and based on studies using similar paradigms across different age groups, we see a pattern of amelioration of MSI over age. Children with ASD are usually impaired, showing less effective integration compared to TD. For most tasks, this impairment normalizes by adulthood, with adolescence being the pivotal point. An exception was seen in a study that involved instantaneous adaptation/calibration, a process that may not be impacted by these developmental gains, and may be related to classic symptoms of autism such as resistance to change and rigidity.

Given the sustained development of MSI seen in ASD, training that is focused on MSI functions, using either behavioral or closed-loop neuromodulatory approaches, holds promise for the early amelioration of MSI in ASD. Critically, this could shift the MSI developmental curve earlier (see Figure 1) so that MSI is available to impact the emergence of functional skills during critical periods in ASD. The reduced long-range connectivity found in ASD by anatomical and functional imaging studies suggest that one possible mechanism underling deficits in MSI among individuals with ASD is perturbed cross-sensory oscillatory synchrony. To address this possibility, future studies should directly investigate the degree of synchronization across the neural network under multisensory stimulation conditions. Broader knowledge of how these processes are affected will allow the development of more precise models of the neural mechanisms underlying impaired MSI in autism (Cuppini et al., 2017), and with the appropriate tools, this knowledge may be applied to enhance performance of individuals with autism.

Highlights.

ASD is associated with impaired integration of multisensory information

Multisensory functions that are impaired in childhood tend to ameliorate with age

This resolution appears for paradigms that use speech and non-speech stimuli

Early training is suggested as a means to improve MSI function in ASD

Changes in cross sensory communication potentially underlie this trajectory

Acknowledgements

Work by the authors on autism was supported by grants from the Daniel R. Tishman Charitable Foundation, the NICHD (HD082814) and NIMH (R01MH085322). Our work on developmental disabilities is supported in part through the Rose F. Kennedy Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC), which is funded through a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD U54 HD090260; previously P30 HD071593). The authors additionally thank Sophia Zhou, Elise Taverna, and Zohar Nir-Amitin for their technical assistance, and Rachel Hester for her critical administrative support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adrian ED, & Matthews BHC (1934). The interpretation of potential waves in the cortex. Journal of Physiology, 81(4), 440–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade GN, Molholm S, Butler JS, Brandwein AB, Walkley SU, & Foxe JJ (2014). Atypical multisensory integration in Niemann-Pick type C disease - towards potential biomarkers. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 9, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf M, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Miller L, Stevens MC, Sahl R, et al. (2010). Abnormal functional connectivity of default mode sub-networks in autism spectrum disorder patients. NeuroImage, 53(1), 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres AJ, & Tickle LS (1980). Hyper-responsivity to touch and vestibular stimuli as a predictor of positive response to sensory integration procedures by autistic children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34, 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrick LE, & Lickliter R (2000). Intersensory redundancy guides attentional selectivity and perceptual learning in infancy. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 190–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao VA, Doobay V, Mottron L, Collignon O, & Bertone A (2017). Multisensory integration of low- level information in autism spectrum disorder: Measuring susceptibility to the flash-beep illusion. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2535–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp MS, Nath A, & Pasalar S (2010). fMRI-guided TMS reveals that the STS is a Cortical Locus of the McGurk Effect. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(7), 2414–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebko JM, Schroeder JH, & Weiss JA (2014). The McGurk effect in children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism Research, 7(1), 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebko JM, Weiss JA, Demark JL, & Gomez P (2006). Discrimination of temporal synchrony in intermodal events by children with autism and children with developmental disabilities without autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier R, Dawson G, Webb S, & Murias M (2007). EEG mu rhythm and imitation impairments in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Brain and Cognition, 64(3), 228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzi Y, Provenzano G, & Casarosa S (2017). Neurobiological bases of autism-epilepsy comorbidity: A focus on excitation/inhibition imbalance. European Journal of Neuroscience, 38, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandwein AB, Foxe JJ, Butler JS, Frey HP, Bates JC, Shulman LH, et al. (2015). Neurophysiological indices of atypical auditory processing and multisensory integration are associated with symptom severity in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(1), 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandwein AB, Foxe JJ, Butler JS, Russo NN, Altschuler TS, Gomes H, et al. (2013). The development of multisensory integration in high-functioning autism: High-density electrical mapping and psychophysical measures reveal impairments in the processing of audiovisual inputs. Cerebral Cortex, 23(6), 1329–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandwein AB, Foxe JJ, Russo NN, Altschuler TS, Gomes H, & Molholm S (2011). The development of audiovisual multisensory integration across childhood and early adolescence: A high-density electrical mapping study. Cerebral Cortex, 21(5), 1042–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock J, Brown CC, Boucher J, & Rippon G (2002). The temporal binding deficit hypothesis of autism. Development and Psychopathology, 14(2), 209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Gruber T, Boucher J, Rippon G, & Brock J (2005). Gamma abnormalities during perception of illusory figures in autism. Cortex, 41(3), 364–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelin J, Mondino M, Gassab L, Haesebaert F, Gaha L, Suaud-Chagny MF, et al. (2012). Examining transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) as a treatment for hallucinations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry, 169(7), 719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni AR, Valiengo L, Baccaro A, Zanao TA, de Oliveira JF, Goulart A, et al. (2013). The sertraline vs. electrical current therapy for treating depression clinical study: results from a factorial, randomized, controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buard I, Rogers SJ, Hepburn S, Kronberg E, & Rojas DC (2013). Altered oscillation patterns and connectivity during picture naming in autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch ER, Santarnecchi E, Antal A, Born J, Celnik PA, Classen J, et al. (2017). Effects of tDCS on motor learning and memory formation: A consensus and critical position paper. Clinical Neurophysiology, 128(4), 589–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D, & Gori M (2012). Chapter 18 - Multisensory Integration Develops Late in Humans. The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes, 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JS, Molholm S, Andrade GN, & Foxe JJ (2016). An Examination of the Neural Unreliability Thesis of Autism. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, & Koch C (2012). The origin of extracellular fields and currents — EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, 407–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinali L, Brozzoli C, & Farnè A (2009). Peripersonal space and body schema: Two labels for the same concept? Brain Topography, 21(3–4), 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon O, Charbonneau G, Peters F, Nassim M, Lassonde M, Lepore F, et al. (2013). Reduced multisensory facilitation in persons with autism. Cortex, 49(6), 1704–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie D, Makin TR, & Bremner AJ (2013). Children’s responses to the rubber-hand illusion reveal dissociable pathways in body representation. PsycholSci, 24(5), 762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie D, Sterling S, & Bremner AJ (2016). The development of multisensory body representation and awareness continues to 10 years of age: Evidence from the rubber hand illusion. J Exp Child Psychol, 142, 230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosse MJ, Foxe JJ, & Molholm S (2017). Impaired development of audiovisual integration in autism and the effects of modality switching. Paper presented at the International Multisensory Research Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppini C, Ursino M, Magosso E, Ross LA, Foxe JJ, & Molholm S (2017). A Computational Analysis of Neural Mechanisms Underlying the Maturation of Multisensory Speech Integration in Neurotypical Children and Those on the Autism Spectrum. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11(518). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datko M, Pineda JA, & Muller RA (2017). Positive effects of neurofeedback on autism symptoms correlate with brain activation during imitation and observation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David N, Schneider TR, Peiker I, Al-Jawahiri R, Engel AK, & Milne E (2016). Variability of cortical oscillation patterns: A possible endophenotype in autism spectrum disorders? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer-Schellekens L, Keetels M, Eussen M, & Vroomen J (2013). No evidence for impaired multisensory integration of low-level audiovisual stimuli in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia, 51(14), 3004–3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gelder B, Vroomen J, & Van der Heide L (1991). Face recognition and lip-reading in autism. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 3(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- deBettencourt MT, Cohen JD, Lee RF, Norman KA, & Turk-Browne NB (2015). Closed-loop training of attention with real-time brain imaging. Nature Neuroscience, 18, 470–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmedt JE, & Tomberg C (1994). Transient phase-locking of 40 Hz electrical oscillations in prefrontal and parietal human cortex reflects the process of conscious somatic perception. Neuroscience Letters, 168(1–2), 126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Yan CG, Li Q, Denio E, Castellanos FX, Alaerts K, et al. (2014). The autism brain imaging data exchange: towards a large-scale evaluation of the intrinsic brain architecture in autism. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(6), 659–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, & Noesselt T (2008). Multisensory interplay reveals crossmodal influences on ‘sensory-specific’ brain regions, neural responses, and judgments. Neuron, 57(1), 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas G, Soussignan R, Hugueville L, Martinerie J, & Nadel J (2014). Revisiting mu suppression in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Research, 1585, 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundon NM, Làdavas E, Maier ME, & Bertini C (2015). Multisensory stimulation in hemianopic patients boosts orienting responses to the hemianopic field and reduces attentional resources to the intact field. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 33(4), 405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Khan SY, Blaskey L, Chow VY, Rey M, Gaetz W, et al. (2015). Neuromagnetic oscillations predict evoked-response latency delays and core language deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(2), 395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MO (2008). Multisensory integration: A late bloomer. Current Biology, 18(12), R519–R521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Cohen AL, Power JD, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Miezin FM, et al. (2009). Functional brain networks develop from a “local to distributed” organization. PLoS Computational Biology, 5(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falchier A, Schroeder CE, Hackett TA, Lakatos P, Nascimento-Silva S, Ulbert I, et al. (2010). Projection from visual areas V2 and prostriata to caudal auditory cortex in the monkey. Cerebral Cortex, 20(7), 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebelkorn IC, Foxe JJ, Butler JS, Mercier MR, Snyder AC, & Molholm S (2011). Ready, set, reset: Stimulus-locked periodicity in behavioral performance demonstrates the consequences of cross-sensory phase reset. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(27), 9971–9981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebelkorn IC, Foxe JJ, McCourt ME, Dumas KN, & Molholm S (2013). Atypical category processing and hemispheric asymmetries in high-functioning children with autism: Revealed through high-density EEG mapping. Cortex, 49(5), 1259–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss-Feig JH, Kwakye LD, Cascio CJ, Burnette CP, Kadivar H, Stone WL, et al. (2010). An extended multisensory temporal binding window in autism spectrum disorders. Experimental Brain Research, 203(2), 381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, Molholm S, Del Bene VA, Frey HP, Russo NN, Blanco D, et al. (2015). Severe multisensory speech integration deficits in high-functioning school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their resolution during early adolescence. Cerebral Cortex, 25(2), 298–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, Morocz IA, Murray MM, Higgins BA, Javitt DC, & Schroeder CE (2000). Multisensory auditory-somatosensory interactions in early cortical processing revealed by high-density electrical mapping. Cognitive Brain Research, 10(1–2), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, & Schroeder CE (2005). The case for feedforward multisensory convergence during early cortical processing. NeuroReport, 16(5), 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, & Simpson GV (2002). Flow of activation from V1 to frontal cortex in humans: A framework for defining “early” visual processing. Experimental Brain Research, 142(1), 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, Simpson GV, & Ahlfors SP (1998). Parieto-occipital ~10 Hz activity reflects anticipatory state of visual attention mechanisms. NeuroReport, 9(17), 3929–3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxe JJ, & Snyder AC (2011). The role of alpha-band brain oscillations as a sensory suppression mechanism during selective attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(154), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco AA, Jesse A, Groen MA, & McQueen JA (2017). A general audiovisual temporal processing deficit in adult readers with dyslexia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60, 144–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki W, Shimojo S, Kashino M, & Nishida S. y. (2004). Recalibration of audiovisual simultaneity. Nature Neuroscience, 7(7), 773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Edgar JC, Ehrlichman RS, Mehta M, Roberts TP, & Siegel SJ (2010). Validating y oscillations and delayed auditory responses as translational biomarkers of autism. Biological Psychiatry, 68(12), 1100–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giard MH, & Peronnet F (2006). Auditory-visual integration during multimodal object recognition in humans: A behavioral and electrophysiological study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 11(5), 473–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ (1969). Principles of perceptual learning and development. Principles of perceptual learning and development, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Gick B, & Derrick D (2009). Aero-tactile integration in speech perception. Nature, 462, 502–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano BL, Ince RAA, Gross J, Schyns PG, Panzeri S, & Kayser C (2017). Contributions of local speech encoding and functional connectivity to audio-visual speech perception. Elife, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ramirez M, Kelly SP, Molholm S, Sehatpour P, Schwartz TH, & Foxe JJ (2011). Oscillatory sensory selection mechanisms during intersensory attention to rhythmic auditory and visual inputs: A human electrocorticographic investigation. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(50), 18556–18567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori M (2015). Multisensory integration and calibration in children and adults with and without sensory and motor disabilities. Multisensory Research, 28(1–2), 71–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori M, Del Viva M, Sandini G, & Burr DC (2008). Young children do not integrate visual and haptic form information. Current Biology, 18(9), 694–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori M, Sandini G, & Burr D (2012). Development of visuo-auditory integration in space and time. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goschl F, Friese U, Daume J, Konig P, & Engel AK (2015). Oscillatory signatures of crossmodal congruence effects: An EEG investigation employing a visuotactile pattern matching paradigm. Neuroimage, 116, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso PA, Benassi M, Ladavas E, & Bertini C (2016). Audio-visual multisensory training enhances visual processing of motion stimuli in healthy participants: An electrophysiological study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 44(10), 2748–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, & Singer W (1989). Stimulus-specific neuronal oscillations in orientation columns of cat visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 86(5), 1698–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield K, Ropar D, Themelis K, Ratcliffe N, & Newport R (2017). Developmental Changes in Sensitivity to Spatial and Temporal Properties of Sensory Integration Underlying Body Representation. Multisensory Research, 30(6), 467–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice SJ, Spratling MW, Karmiloff-Smith A, Halit H, Csibra G, De Haan M, et al. (2001). Disordered visual processing and oscillatory brain activity in autism and Williams syndrome. NeuroReport, 12(12), 2697–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn N, Foxe JJ, & Molholm S (2014). Impairments of multisensory integration and cross-sensory learning as pathways to dyslexia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kenny A, Bajo VM, King AJ, & Nodal FR (2016). Behavioural benefits of multisensory processing in ferrets. European Journal of Neuroscience, 45(2), 278–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson HM, & Bishop DVM (2017). The interpretation of mu suppression as an index of mirror neuron activity: past, present and future. Royal Society Open Science, 4(3), 160662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockley NS, & Polka L (1994). A developmental study of audiovisual speech perception using the McGurk paradigm. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96, 3309. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath JC, Carter O, & Forte JD (2016). No significant effect of transcranial direct current Stimulation (tDCS) found on simple motor reaction time comparing 15 different simulation protocols. Neuropsychologia, 91, 544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath JC, Forte JD, & Carter O (2015). Evidence that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) generates little-to-no reliable neurophysiologic effect beyond MEP amplitude modulation in healthy human subjects: A systematic review. Neuropsychologia, 66, 213–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath JC, Vogrin SJ, Carter O, Cook MJ, & Forte JD (2015). Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on motor evoked potential amplitude are neither reliable nor significant within individuals over 9 separate testing sessions. Brain Stimulation, 8(2), 318. [Google Scholar]

- larocci G, & McDonald J (2006). Sensory integration and the perceptual experience of persons with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- larocci G, Rombough A, Yager J, Weeks DJ, & Chua R (2010). Visual influences on speech perception in children with autism. Autism, 14(4), 305–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin JR, & Brancazio L (2014). Seeing to hear? Patterns of gaze to speaking faces in children with autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin JR, Tornatore LA, Brancazio L, & Whalen DH (2011). Can children with autism spectrum disorders “hear” a speaking face? Child Development, 82(5), 1397–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaekl P, Pesquita A, Alsius A, Munhall K, & Soto-Faraco S (2015). The contribution of dynamic visual cues to audiovisual speech perception. Neuropsychologia, 75, 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Stein BE, & McHaffie JG (2015). Multisensory training reverses midbrain lesion-induced changes and ameliorates haemianopia. Nature Communications, 6, 7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser MD, Yang DYJ, Voos AC, Bennett RH, Gordon I, Pretzsch C, et al. (2016). Brain mechanisms for processing affective (and nonaffective) touch are atypical in autism. Cerebral Cortex, 26(6), 2705–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. The Nervous Child, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgi M, Bräcker LB, Lebreton S, Minervino C, Cavey M, Siju KP, et al. (2017). Evolution of multiple sensory systems drives novel egg-laying behavior in the fruit pest drosophila suzukii. Current Biology, 27(6), 847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane BP, Rosenthal O, Chun NH, & Shams L (2010). Audiovisual integration in high functioning adults with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Keehn B, Westerfield M, Müller R-A, & Townsend J (2017). Autism, attention, and alpha oscillations: An electrophysiological study of attentional capture. Biological Psychiatry , In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SP, Gomez-Ramirez M, & Foxe JJ (2009). The strength of anticipatory spatial biasing predicts target discrimination at attended locations: A high-density EEG study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 30(11), 2224–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniston LP, Henderson SC, & Meredith MA (2010). Neuroanatomical identification of crossmodal auditory inputs to interneurons in somatosensory cortex. Experimental Brain Research, 202(3), 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JK, Trivedi MH, Garver CR, Grannemann BD, Andrews AA, Savla JS, et al. (2006). The pattern of sensory processing abnormalities in autism. Autism, 10(5), 480–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W, Doppelmayr M, Russegger H, Pachinger T, & Schwaiger J (1998). Induced alpha band power changes in the human EEG and attention. Neuroscience Letters, 244(2), 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolschijn PC, Caan MW, Teeuw J, Olabarriaga SD, & Geurts HM (2017). Age-related differences in autism: The case of white matter microstructure. Human Brain Mapping, 38(1), 82–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala T, Karma K, Ceponiene R, Belitz S, Turkkila P, Tervaniemi M, et al. (2001). Plastic neural changes and reading improvement caused by audiovisual training in reading-impaired children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98(18), 10509–10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala T, Lepistö T, Nieminen-von Wendt T, Näätänen P, & Näätänen R (2005). Neurophysiological evidence for cortical discrimination impairment of prosody in Asperger syndrome. Neuroscience Letters, 383(3), 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwakye LD, Foss-Feig JH, Cascio CJ, Stone WL, & Wallace MT (2010). Altered auditory and multisensory temporal processing in autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 4, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos P, Chen CM, O’Connell MNO, Mills A, & Schroeder CE (2007). Neuronal oscillations and multisensory interaction in primary auditory cortex. Neuron, 53(2), 279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]