Abstract

Purpose:

In postmenopausal women, high body mass index (BMI) is an established breast cancer risk factor and is associated with worse breast cancer prognosis. We assessed the associations between BMI and gene expression of both breast tumor and adjacent tissue in estrogen receptor positive (ER+) and negative (ER-) diseases to help elucidate the mechanisms linking obesity with breast cancer biology in 519 postmenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII.

Methods:

Differential gene expression was analyzed separately in ER+ and ER- disease both comparing overweight (BMI ≥25 to <30) or obese (BMI ≥30) women to women with normal BMI (BMI <25), and per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI. Analyses controlled for age and year of diagnosis, physical activity, alcohol consumption and hormone therapy use. Gene set enrichment analyses were performed and validated among a subset of postmenopausal cases in The Cancer Genome Atlas (for tumor) and Polish Breast Cancer Study (for tumor-adjacent).

Results:

No gene was differentially expressed by BMI (FDR<0.05). BMI was significantly associated with increased cellular proliferation pathways, particularly in ER+ tumors, and increased inflammation pathways in ER- tumor and ER- tumor-adjacent tissues (FDR<0.05). High BMI was associated with upregulation of genes involved in epithelial mesenchymal transition in ER+ tumor-adjacent tissues.

Conclusions:

This study provides insights into molecular mechanisms of BMI influencing postmenopausal breast cancer biology. Tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues provide independent information about potential mechanisms.

Keywords: breast cancer, obesity, gene expression, the cancer genome atlas, nurses’ health study, polish breast cancer study

Introduction

High body mass index (BMI) after menopause is an established breast cancer risk factor [1, 2]. Obese post-menopausal women (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) have about a 70% increased risk of estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer compared to lean women, while there is less evidence suggesting BMI is associated with ER- disease [3–6]. Additionally, being overweight (BMI 25 to 29.9 kg/m2) or obese is also associated with worse prognosis in ER+ disease, but not in ER- [7–10].

Multiple biological mechanisms may underlie the link between high BMI with ER+ breast cancer risk. One well supported mechanism is the increased estradiol concentrations produced by adipose tissue in overweight or obese postmenopausal women [11]. Exposure of estrogen-sensitive breast tissues to high estrogen levels leads to increased cellular proliferation and initiates mutation and development of breast cancer [12, 13]. Other obesity-related effects such as insulin resistance [14], impaired adipokine production by adipocytes [15, 16], and low grade local inflammation [17] also may contribute to the proliferation of mammary cells and breast tumorigenesis [18–20]. On the other hand, recent investigations have identified the effect of insulin on AKT/mTOR signaling and glycolysis; obesity-mediated tissue inflammatory cytokines (e.g. leptin); and obese tissue microenvironment as plausible mechanistic links between obesity and triple negative breast cancer (i.e., an ER- disease) [21]. Given potential cross talk between these pathways, it is important to understand the complex biology that underlies how BMI influences breast tumor growth. Previous studies have investigated tumor molecular pathways associated with obesity in breast cancer patients [16, 22–25], but did not stratify their study population by menopausal status [16] or tumor ER status [24] due to small sample sizes.

With rising obesity rates [26], it is important to gain insights into the molecular mechanisms of BMI driving breast cancer etiology to aid screening and prevention recommendations, and identify therapeutic targets for obese patients. The overarching aim of our work was to elucidate mechanisms linking obesity with breast cancer biology in post-menopausal women. Specifically, we assessed the associations between BMI and tissue gene expression in ER+ and ER- post-menopausal breast tumors, and tumor-adjacent tissues, from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII. Lastly, we validated our findings by using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for tumors [27–29] and the Polish Breast Cancer Study (PBCS) for tumor-adjacent tissues [30, 31].

Materials and Methods

Study population

The Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA approved this study (Protocol Number: 2010P001641). The NHS and NHSII are ongoing prospective studies. The NHS was established in 1976 with 121,701 female registered nurses, aged 30–55 years, and the NHSII was established in 1989 with 116,429 female registered nurses, aged 25–42 years. The cohorts have been followed biennially by questionnaires to query exposures and ascertain newly diagnosed diseases. Participants provide information on a range of breast cancer risk factors, including dietary, lifestyle and reproductive factors, anthropometric measures, medication use and health outcomes.

Breast cancer diagnoses were reported on biennial questionnaires or identified through death records. Written permission was obtained from participants diagnosed with breast cancer, or their next of kin, to review medical records to confirm diagnosis and extract relevant cancer information. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue blocks were requested from treating hospitals [32]. Post-menopausal women with confirmed invasive breast cancer from NHS and NHSII and tissue blocks were selected for this study (n=577).

Body mass index and other covariates

Weight and height were reported on study questionnaires; self-reported weight and height were previously validated in the NHSII [33]. Height was obtained at enrollment while weight was updated every two years, starting from 1976 (NHS) or 1991 (NHSII). BMI was calculated using self-reported weight from the participant’s last available questionnaire before breast cancer diagnosis (i.e. within 2–4 years of diagnosis). Other covariates such as race, BMI at age 18, age at first birth, parity, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, menopausal status, recent postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT), smoking, cumulative average physical activity (metabolic equivalent hours/week) [34] and cumulative average alcohol consumption (grams/day) [28, 35] were retrieved from baseline, subsequent or most recent NHS/NHSII questionnaires. Tumor characteristics were extracted from medical pathology reports. Immunohistochemical statuses of ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2 were obtained from central review of breast tissue microarrays [32]. Differences in demographic, clinical and other covariates across BMI categories were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis, Fisher’s exact or Chi-squared test (R, version 3.2.1). Statistical significance was considered as p<0.05.

RNA extraction and microarray

Multiple tissue cores of 1 or 1.5 mm were obtained from tumor and/or histologically normal tumor-adjacent tissue. Tumor-adjacent tissue was obtained greater than one centimeter from the invasive carcinoma whenever possible; a minimum of 2 mm between tumor and tumor-adjacent was permitted. Total RNA was extracted from 577 FFPE blocks for 1154 tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues. RNA samples with at least 50 ng (n=1027) were sent for microarray using the Glue Grant Human Transcriptome Array 3.0 pre-release version (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) [36]; 127 samples comprising of 10 tumors and 117 tumor-adjacent samples were excluded due to insufficient RNA. Gene expression was normalized, summarized into Log2 values using Robust Multi-array Average (Affymetrix Power Tools (APT) v1.18.0) and annotated [36, 37]. Data quality was first evaluated using APT probeset summarization based metrics; samples should ideally have a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve of >0.8 [38]. Due to the nature of FFPE samples, we retained 888 samples with ROC AUC of >0.55 and performed a second round of quality control using arrayQualityMetrics v3.24.0 [39]. There were 850 final microarray files comprising of 478 tumor and 372 tumor-adjacent tissues from 519 women.

Gene expression data were further processed by: removing 195 probes associated with the Y chromosome, removing unannotated probes, selecting the most variable probe for genes that were represented by multiple probes, correcting for batch effects using a surrogate variable analysis (SVA) R package, ComBat [40], and excluding low expressing genes (<25th percentile). The final dataset consisted of 15,369 annotated probesets of coding and non-coding RNAs. All microarray and annotation data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number: GSE115577).

Differential gene expression

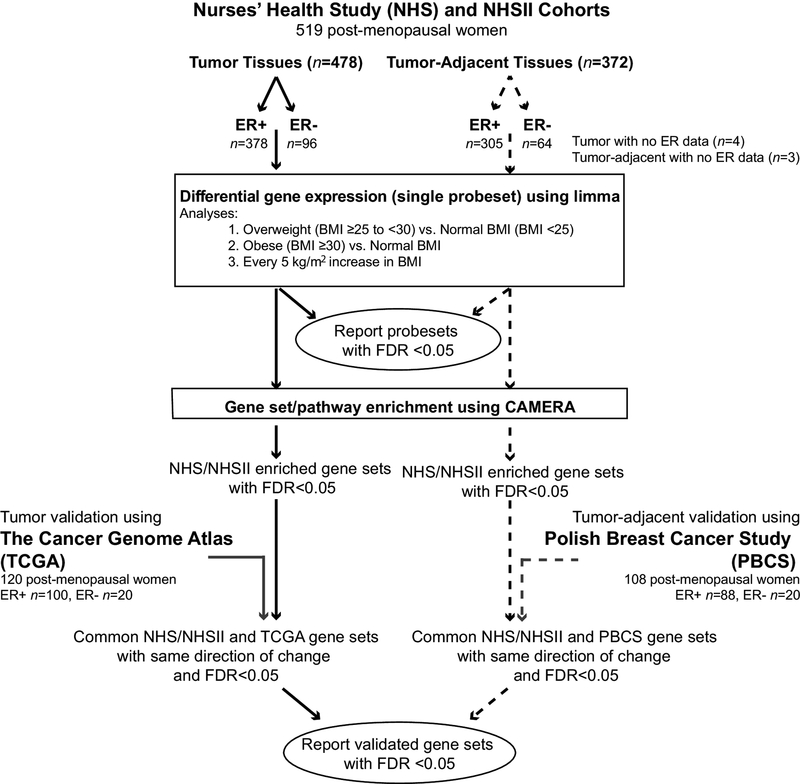

Figure 1 summarizes our analysis and results workflow and presentation. Differential gene expression was analyzed using multivariable linear regression (limma R package), controlling for age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, physical activity, alcohol consumption and HT use. Since only 44 (9.6%) women were current or recent smokers and this percentage was similar across BMI categories (10.9% in normal, 8.1% in overweight and 7.3% in obese groups), we did not control for smoking in our differential gene expression analyses. Inferences were stabilized for correlated gene structures using an empirical Bayes method and corrected for multiple hypothesis testing [41]. We performed differential gene expression in ER+ or ER- disease between overweight (BMI ≥25 to <30) or obese (BMI ≥30) women versus women with normal BMI (BMI <25), as well as differential gene expression per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI. Tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues were analyzed separately. Statistical significance for differential gene expression was achieved when false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05. There were four underweight women (BMI <18.5) and their exclusion did not affect our results, and thus they were retained in the normal BMI group (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Schematic workflow of data analyses using the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Polish Breast Cancer Study (PBCS).

Gene set enrichment

Gene set enrichment was conducted using 50 Hallmark gene sets (version 6.1; Broad Institute, Molecular Signature Database) [42] with Camera, a competitive gene set testing method which accounts for inter-gene correlation [43]. Statistical significance for gene set enrichment was achieved when FDR<0.05.

Validation of gene expression and gene set enrichment

We validated our results with a subset of TCGA post-menopausal women with invasive breast cancer cases (n=120; Supplementary File 1) for tumor tissues [28] and a subset of post-menopausal participants in the PBCS (n=108) for tumor-adjacent tissues [30, 44, 45]. Gene expression was considered validated if the gene was differentially expressed in the same direction with FDR<0.05 in the TCGA or PBCS cohorts. Gene sets were considered validated when they were significantly enriched in the same direction (i.e., up- or down-regulated; FDR<0.05). Our gene set enrichment results focused on validated gene sets associated with every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI for maximum power.

Identification of driver genes in enriched gene sets

To identify important genes contributing to the enrichment of several gene sets, we first identified common genes within biologically related gene sets (e.g. genes in both IFN gamma response and IFN alpha response). Next, we looked at the standard gene wise differential expression of these common genes (i.e., the limma analyses). An arbitrary cut-off of p<0.10 was applied to identify genes that were most likely contributing to the enrichment of gene sets.

Please refer to Supplementary Methods for additional methodology details.

Results

Demographic, epidemiologic and tumor characteristics of participants

The NHS/NHSII participants were mostly white with average BMI of 26.4. Of the participants with tumor samples (n=478), paired tumor-adjacent tissues were available on 331 (69%). The characteristics of women with tumor-adjacent samples were similar to those with tumor specimens (Table 1). ER data were missing for four tumor and three tumor-adjacent tissues. Most of our post-menopausal cases had ER+ breast cancer (80%) and were classified as Luminal A tumors (46%), while tumor-adjacent samples were predominantly classified as Normal-Like (56%; p=0.03; Table 1). Obese participants had higher BMI at age 18, lower levels of physical activity, drank less alcohol and were least likely to use HT compared to normal and overweight participants (p<0.05; Table 1). Women across BMI groups had comparable tumor size, clinical grade and lymph node status. ER- tumors were predominately clinical grades II and III, and were PR- (99%; Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, lifestyle and tumor characteristics of post-menopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS)/NHSII.

| Tumor | Tumor-Adjacent | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.4 (1.6) | 27.2 (1.5) | 33.9 (3.7) | 22.4 (1.6) | 27.2 (1.4) | 34.3 (4.0) | ||||

| Women Demographics | ||||||||||

| n | 220 | 148 | 110 | 176 | 117 | 79 | ||||

| Nurses’ Health Study Cohort, n (%) | 0.77 | 0.42 | ||||||||

| NHS | 196 (89.1) | 130 (87.8) | 95 (86.4) | 154 (87.5) | 97 (82.9) | 65 (82.3) | ||||

| NHSII | 24 (10.9) | 18 (12.2) | 15 (13.6) | 22 (12.5) | 20 (17.1) | 14 (17.7) | ||||

| Race, n (%) | 0.16 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| White | 215 (97.7) | 140 (94.6) | 108 (98.2) | 172 (97.7) | 108 (92.3) | 78 (98.7) | ||||

| Others | 5 (2.3) | 8 (5.4) | 2 (1.8) | 4(2.3) | 9 (7.7) | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, mean (sd) | 63.5 (7.6) | 63.6 (7.2) | 64.1 (8.0) | 0.65 | 63.0 (7.6) | 64.0 (7.7) | 63.9 (8.4) | 0.49 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.59 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| 1989–1993 | 57 (25.9) | 31 (20.9) | 21 (19.1) | 44 (25.0) | 19 (16.2) | 14 (17.7) | ||||

| 1994–1998 | 80 (36.4) | 52 (35.1) | 41 (37.3) | 57 (32.4) | 36 (30.8) | 29 (36.7) | ||||

| 1999–2003 | 65 (29.5) | 50 (33.8) | 33 (30.0) | 58 (33.0) | 47 (40.2) | 24 (30.4) | ||||

| 2004–2008 | 18 (8.2) | 15 (10.1) | 15 (13.6) | 17 (9.7) | 15 (12.8) | 12 (15.2) | ||||

| Age at first child birth, mean (sd) | 25.8 (3.4) | 25.7 (3.7) | 25.9 (4.3) | 0.73 | 25.7 (3.6) | 25.9 (3.6) | 26.1 (4.6) | 0.90 | ||

| Number of children, mean (sd) | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.9) | 0.42 | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.8 (1.9) | 2.8 (2.0) | 0.45 | ||

| Lifestyle Factors | ||||||||||

| BMI at 18 years of age, mean (sd) | 20.4 (2.4) | 21.0 (2.3) | 22.5 (3.1) | <0.01 | 20.3 (2.3) | 21.0 (2.3) | 22.5 (3.2) | <0.01 | ||

| Physical activity, mean mets-h/week (sd) | 19.9 (17.8) | 16.1 (14.6) | 14.4 (12.8) | 0.01 | 20.7 (18.2) | 16.2 (13.4) | 14.7 (13.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Alcohol intake, mean g/day (sd) | 8.3 (11.1) | 6.5 (9.2) | 4.6 (8.9) | <0.01 | 8.2 (11.1) | 6.7 (9.3) | 4.5 (8.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Recent hormone therapy use, n (%) | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Yes | 141 (64.1) | 78 (52.7) | 47 (42.7) | 116 (65.9) | 61 (52.1) | 34 (43.0) | ||||

| No | 77 (35.0) | 67 (45.3) | 57 (51.8) | 58 (33.0) | 53 (45.3) | 42 (53.2) | ||||

| Unknown | 2 (0.9) | 3 (2.0) | 6 (5.5) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) | ||||

| Tumor Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Tumor Size, n (%) | ||||||||||

| ≤2cm | 161 (75.2) | 112 (78.3) | 76 (71.0) | 0.24 | - | - | - | |||

| >2 to ≤4 cm | 36 (16.8) | 27 (18.9) | 24 (22.4) | - | - | - | ||||

| >4cm | 17 (7.9) | 4 (2.8) | 7 (6.5) | - | - | - | ||||

| Tumor Grade, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 69 (32.7) | 32 (23.0) | 22 (20.4) | 0.10 | - | - | - | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 107 (50.7) | 78 (56.1) | 60 (55.6) | - | - | - | ||||

| Poorly differentiated | 35 (16.6) | 29 (20.9) | 26 (24.1) | - | - | - | ||||

| Lymph Node Status, n (%) | ||||||||||

| No nodes involved | 154 (75.1) | 101 (73.2) | 72 (70.6) | 0.78 | - | - | - | |||

| 1–3 nodes | 35 (17.1) | 25 (18.1) | 20 (19.6) | - | - | - | ||||

| 4–9 nodes | 12 (5.9) | 7 (5.1) | 6 (5.9) | - | - | - | ||||

| 10+ nodes | 2 (1.0) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (2.9) | - | - | - | ||||

| Metastasis at diagnosis | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | - | - | - | ||||

| Stage | 0.52 | |||||||||

| I | 141 (64.1) | 96 (64.9) | 61 (55.5) | - | - | - | ||||

| II | 61 (27.7) | 37 (25.0) | 37 (33.6) | - | - | - | ||||

| III | 16 (7.3) | 15 (10.1) | 11 (10.0) | - | - | - | ||||

| IV | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | - | - | - | ||||

| Estrogen Receptor*, n (%) | 0.15 | |||||||||

| Positive | 170 (78.0) | 125 (85.0) | 83 (76.1) | - | - | - | ||||

| Negative | 48 (22.0) | 22 (15.0) | 26 (23.9) | - | - | - | ||||

| Progesterone | 0.26 | |||||||||

| Receptor*, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Positive | 166 (76.1) | 121 (82.9) | 83 (76.1) | - | - | - | ||||

| Negative | 52 (23.9) | 25 (17.1) | 26 (23.9) | - | - | - | ||||

| HER2*, n (%) | 0.22 | |||||||||

| Positive | 60 (30.9) | 54 (40.0) | 37 (37.0) | - | - | - | ||||

| Negative | 134 (69.1) | 81 (60.0) | 63 (63.0) | - | - | - | ||||

Immunohistochemistry for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 were centrally reviewed using tissue microarrays. If missing, data were extracted from medical records.

Comparison of NHS/NHSII participants to validation cohorts

Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 show characteristics of the previously published postmenopausal participants from TCGA [28] and PBCS. Most participants were also white females. Compared to NHS/NHSII, TCGA participants were more recently diagnosed, had higher BMI when obese (TCGA obese group BMI mean 36.0 versus 33.9 in NHS/NHSII), and had more advanced disease (stages II/III: TCGA 71% and NHS/NHSII 37%; stage I: TCGA 29% and NHS/NHSII 62%). TCGA participants were also less likely to use HT and tumors were less likely to be HER2 positive. PBCS post-menopausal women were younger, were diagnosed between 1999 and 2003, drank less alcohol, were less likely to use HT, were less likely to be HER2 positive and had more advanced disease (36% of PBCS were stage I, 64% were stages II/III) compared to NHS/NHSII.

Differential gene expression in NHS/NHSII cohorts

In both ER+ and ER- tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues, there was no significant differentially expressed gene associated with overweight or obese women compared to normal weight women (FDR>0.05; Supplementary File 2). When BMI was analyzed as a continuous variable, there was no differentially expressed gene in ER+ and ER- tumors, and ER+ tumor-adjacent tissues (FDR>0.05; Supplementary File 2). Cytokine receptor like factor 3 (CRLF3) expression was 20% higher per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI in the tumor-adjacent tissues of ER- women (FDR<0.05), but this result was not replicated in PBCS (Supplementary File 2).

Gene set enrichment

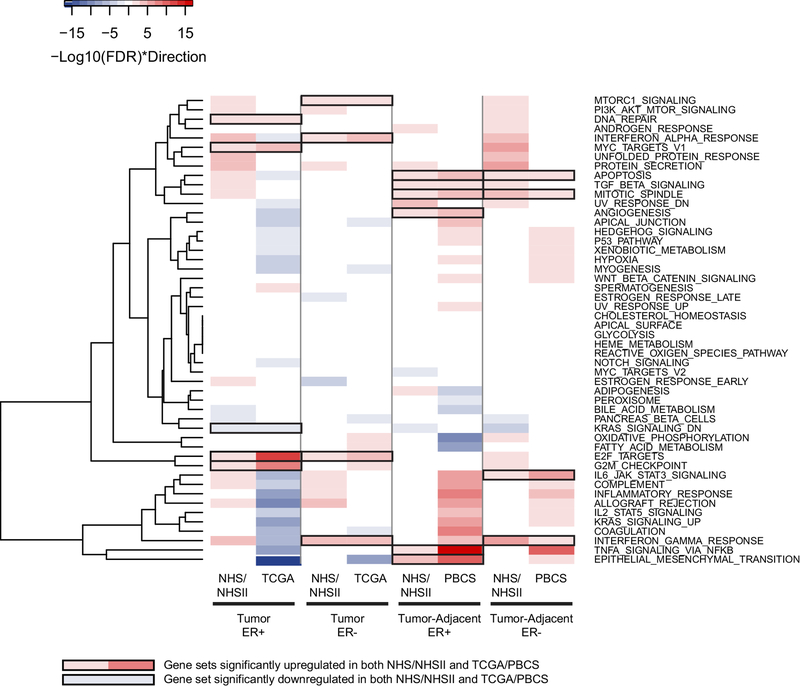

In general, enriched gene sets, including multiple obesity-related pathways regulating insulin receptor signaling and inflammation, were observed in NHS/NHSII, but only a subset was validated in TCGA or PBCS (Figure 2). For example, as BMI increased, the early estrogen response pathway was significantly upregulated in NHS/NHSII ER+ tumors and downregulated in NHS/NHSII ER- tumors, but these observations were not replicated.

Figure 2.

Heatmap displaying the enrichment of 50 Hallmark gene sets (FDR<0.05) with every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI in estrogen receptor positive (ER+) or negative (ER-) post-menopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the validation cohorts (The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for tumors and Polish Breast Cancer Study (PBCS) for tumor-adjacent). Upregulated gene sets are in red; downregulated gene sets are in blue; validated gene sets are highlighted using black outlines.

Focusing on validated gene sets associated with increasing BMI that were common to both ER+ and ER- tumors, the E2F TARGETS pathway was significantly upregulated (FDR<0.05; Figure 2). No driver gene was common to both diseases. In ER+ tumors, higher BMI was associated with upregulation of two additional proliferation pathways (G2M CHECKPOINT and MYC TARGETS V1) and genes involved in DNA repair; a set of genes was significantly downregulated by KRAS activation (Figure 2). Two common driver genes, HNRNPD and SYNCRIP, contributed to the three proliferation pathways in ER+ tumors (p<0.10; Supplementary Figure 1A). In addition to E2F TARGETS, higher BMI was associated with increased expression of genes associated with IFN alpha and gamma response and activated mTORC1 complex (i.e., increased protein translation; Figure 2) among ER- tumors. Three common driver genes, CASP8, RTP4 and IFIT3, contributed to the IFN pathways in ER- tumors (Supplementary Figure 1B).

Among tumor-adjacent tissues, BMI was associated with increased expression of genes linked to cell death and the assembly of mitotic spindles in women with ER+ and ER- diseases (Figure 2), but no common driver genes were identified. There were four other validated gene sets in ER+ tumor-adjacent tissues associated with higher BMI: epithelial mesenchymal transition, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha signaling via NFKB, angiogenesis and transforming growth factor (TGF) beta signaling (Figure 2). GADD45B and SAT1 contributed to the enrichment of epithelial mesenchymal transition, TNF alpha signaling via NFKB and apoptosis while LUM was the driver gene for both apoptosis and angiogenesis pathways (Supplementary Figure 1C). Tumor-adjacent tissues in ER- disease displayed activated inflammation pathways including interleukin (IL) 6 and IFN gamma with increasing BMI (Figure 2). STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, PTPN1, PTPN2, MYD88, IRF1 and CXCL9 were the common driver genes for these two pathways (Supplementary Figure 1D).

ER- women with higher BMI expressed elevated interferon (IFN) gamma response with eight common driver genes in both tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues (HLA-DQA1, NCOA3, CXCL9, LCP2, GZMA, SPPL2A, STAT1 and CASP4). Secondary analyses were conducted in NHS/NHSII among ER+ stage I versus stage II/III tumors; by HT use (ever/never) among ER+ women; by excluding women with BMI ≥38; and by accounting for HER2 status (assessed by immunohistochemistry) in the analysis. Overall results were similar (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large study of post-menopausal women, we characterized the gene expression profiles of both breast tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues associated with higher pre-diagnosis BMI, and used two independent cohorts to validate our results in silico. No individual gene was differentially expressed by level of BMI in either the NHS/NHSII or the replication data sets. However, women with higher BMI, particularly those with ER+ tumors, had upregulation of proliferation-related gene sets. Gene sets associated with high cellular turn over were associated with higher BMI in tumor-adjacent tissues. Breast tissues of ER- women displayed elevated inflammation with increasing BMI. Our work provides further insight into the link between adiposity and breast cancer biology.

Overall, higher BMI was associated with increased cellular proliferation in breast cancer. Proliferation was particularly prominent in ER+ tumors. While there was no common driver gene identified in E2F TARGETS for ER+ and ER- tumors, synaptotagmin binding cytoplasmic RNA interacting protein (SYNCRIP) was one of the driver genes identified in ER+ tumors. SYNCRIP is a heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein involved in endocrine resistant and breast tumorigenesis [46]. Specifically in ER+ tumors, genes associated with KRAS activation were downregulated among women with higher BMI, providing indirect evidence that KRAS signaling is activated. The five validated gene sets in ER+ tumors collectively suggest that higher BMI in ER+ disease can lead to greater genomic instability as indicated by elevated proliferation and KRAS signaling, and in response, genes involved in DNA repair may be up-regulated. ER- tumors were characterized by other obesity hallmarks such as inflammation [17] and mTORC1 activation [47, 48]. In sum, our data reinforce that ER+ and ER- tumors are separate diseases with distinct biology, support previous studies that excess adiposity enhances cellular proliferation of breast tumors [16, 49, 50], and point to several potential mechanisms whereby being overweight or obese could be associated with worse prognosis in ER+ disease [7–10].

There was little overlap in gene sets between ER+ tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues. This may be attributed to differences in cellular composition between adjacent normal and tumor tissues, as well as changes induced by the carcinogenic process. Previous studies reported that tumor and normal breast tissues differ in their association with risk factor exposures [44]. In our study, the epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene set was enriched specifically in ER+ tumor-adjacent tissues, but not in ER+ tumor tissue as reported by Fuentes-Mattei et al [16]. Since TNF alpha signaling can influence the breast epithelial-mesenchymal transition [51], one source of TNF may be obesity-related local inflammation [52]. Our work provides some insights into the “etiologic field effect” of BMI on ER+ tumor-adjacent tissues [53].

Tumor characteristics are reflected in tumor-adjacent tissue, in particular, inflammation is present in both tumor and tumor-adjacent normal surrounding basal-like cancers [54]. We found that genes involved in inflammation were upregulated in both tumor and tumor-adjacent tissues of ER- women, with eight common genes driving the IFN gamma response pathway in both tissue types. This suggests that inflammation associated with BMI was more evident and robust in tissue among women with ER- disease. Collectively, obesity related inflammation in both ER+ and ER- tumor-adjacent tissues/microenvironment may promote breast cancer aggressiveness via elevated aromatase, metabolic dysfunction and extracellular matrix substances secreted by adipose tissues (e.g. matrix metalloproteases, chemokines, and pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL6) [55–58].

Since estrogen levels in blood and breast tissues are positively correlated with BMI [11, 59], we expected to observe a BMI/estrogen-related pathway association in ER+ tumors. Although the estrogen pathway was significantly upregulated in the NHS/NHSII cohort, this observation was not replicated. An obesity gene signature developed by Creighton et al also did not contain ER, PR or other estrogen-regulated genes [24]. We did, however, observe increases in a number of proliferation-related pathways (for both ER+ and ER- tumors) and in DNA repair (ER+ tumors), which can be caused by ER signaling and estrogen metabolites [60, 61]. Clearly, the relationship between tissue estrogen signaling pathways and adiposity requires further investigation.

Fuentes-Mattei and colleagues [16] also reported that obesity accelerates ER+ breast cancer progression via adipogenesis and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [16]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in tumors was upregulated in both NHS/NHSII and TCGA but was only statistically significant in NHS/NHSII. The smaller sample sizes and differences in ER and/or HER2 status (less ER- and/or HER2 positive cases) of the validation cohorts compared to NHS/NHSII; different tissue types (fresh frozen versus FFPE); and gene expression platforms may contribute to our inability to validate certain pathways. Our findings were generally robust in sub-analyses that made the NHS/NHSII and validation cohorts more comparable (e.g., among stage I tumors only). Overall, these differences also highlight the challenges in obtaining large, comparable, independent datasets for gene expression and pathway validation.

The strengths of our study include leveraging the large well-characterized NHS/NHSII cohorts which collected detailed epidemiologic data prior to diagnosis and we were able to control for well-known risk factors. Further, all breast cancer cases were pathologically confirmed and ER status was centrally reviewed. Given that the validation data sets had distinct population characteristics and used different technical platforms, replication represents gene sets that are likely to be robust across a range of populations and across methods.

Limitations of our study include the use of FFPE samples for microarray in NHS/NHSII, and small sample sizes for ER- cases, particularly in the validation datasets. Our FFPE samples were processed by various institutions and some FFPE blocks were over 20 years old. This resulted in lower quality RNA yield and microarray CEL files. We addressed this by performing two quality control steps and demonstrated high correlations between ESR1, PGR, and ERBB2 expression with ER, PR and HER2 immunohistochemistry staining [28]. We were underpowered to stratify our samples by ER and HER2 simultaneously to better understand the biological effect of BMI on tumors by HER2 status. We attempted to address the imbalance in HER2 status between NHS/NHSII and the validation cohorts by accounting for HER2 in our secondary analyses. Future studies with more cases of ER- tumors and HER2 status are warranted to investigate the biological effects of ER and HER2 with BMI. Another limitation was the unknown germline BRCA1/2 status of our cases. We were unable to assess if BRCA1/2 mutation influences the association between BMI and DNA repair pathways. Our study consisted of mostly white females. Hence, replication in other ethnically-diverse cohorts is warranted. Lastly, we were unable to evaluate prognostic genes associated with BMI due to limited breast cancer specific survival events in this study population.

In summary, this study presents the largest postmenopausal breast tumor and tumor-adjacent dataset and analyses to date, and our data were independently replicated. Higher BMI was associated with higher expression of cellular proliferation pathways in breast cancer. In ER- disease, higher BMI was associated with interferon gamma pathway. Future work can include mechanistic studies to investigate how BMI-associated pathways influence postmenopausal breast etiology and identifying prognostic breast cancer genes or gene sets associated with high BMI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods. Detailed description of methodologies.

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of Nurses’ Health Study (NHS)/NHSII post-menopausal participants, stratified by estrogen receptor positive or negative disease.

Supplementary Table 2. Post-menopausal participants from The Cancer Genome Atlas with invasive breast cancer.

Supplementary Table 3. Post-menopausal participants from the Polish Breast Cancer Study with invasive breast cancer.

Supplementary Figure 1. Heatmaps displaying driver genes (p<0.10, limma analyses) that are contributing to the enrichment of the validated gene sets in A. estrogen receptor positive tumors, B. estrogen receptor negative tumors, C. estrogen receptor positive tumor-adjacent tissues and D. estrogen receptor negative tumor-adjacent tissues. Increasing color intensity of the cells indicates a smaller p value.

Supplementary File 1. Questionnaire provided to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) participants to collect lifestyle variables.

Supplementary File 2. Detailed differential gene expression analyses using limma.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of the NHS and the NHSII for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. We are grateful to the participants of TCGA and PBCS.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by National Institutes of Health grants U19 CA148065, UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, UM1 CA176726, and R01 CA166666; National Institute of Health Epidemiology Education Training Great (T32 CA09001 to NCD); the National Library of Medicine Career Development Award (K22LM011931; AHB); Susan G. Komen (SAC110014 to SEH; CCR 14302670 to AHB); the Klarman Family Foundation (YJH and AHB); and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Dean’s Faculty Advancement Award (FM). Funds from the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program supported the Polish Breast Cancer Study and work by MGC and TA.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA reviewed and approved this study.

Availability of data and material

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The NHS/NHSII microarray data is publicly available at GSE115577. TCGA RNASeq data is available at https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. PBCS data are available from GSE49175 and GSE50939.

Competing interests

AHB is an equity stock holder and Board of Director Member of PathAI. All other authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, et al. (1997) Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA 278:1407–1411. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550170037029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eliassen AH, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. (2006) Adult weight change and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. JAMA 296:193–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard ME, Boeke CE, Tamimi RM (2015) Established breast cancer risk factors and risk of intrinsic tumor subtypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1856:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang XR, Chang-Claude J, Goode EL, et al. (2011) Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: A pooled analysis from the breast cancer association consortium studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:250–263. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hazra A, et al. (2012) Traditional breast cancer risk factors in relation to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131:159–167. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1702-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki R, Orsini N, Saji S, et al. (2009) Body weight and incidence of breast cancer defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status-A meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124:698–712. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH (2010) Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 123:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewertz M, Jensen M-BB, Gunnarsdóttir KÁ, et al. (2011) Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:25–31. doi: 10.1200/JC0.2010.29.7614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon YW, Kang SH, Park MH, et al. (2015) Relationship between body mass index and the expression of hormone receptors or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 with respect to breast cancer survival. BMC Cancer 15:865. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1879-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparano JA, Wang M, Zhao F, et al. (2012) Obesity at diagnosis is associated with inferior outcomes in hormone receptor-positive operable breast cancer. Cancer 118:5937–5946. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Hankinson SE (2013) Postmenopausal plasma sex hormone levels and breast cancer risk over 20 years of follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137:883–892. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2391-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yager JD, Davidson NE (2006) Estrogen Carcinogenesis in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yue W, Yager JD, Wang JP, et al. (2013) Estrogen receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms of breast cancer carcinogenesis. Steroids 78:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn BB, Flier JS (2000) Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 106:473–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI10842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balaban S, Shearer RF, Lee LS, et al. (2017) Adipocyte lipolysis links obesity to breast cancer growth: adipocyte-derived fatty acids drive breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Metab 5:1. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0163-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentes-Mattei E, Velazquez-Torres G, Phan L, et al. (2014) Effects of obesity on transcriptomic changes and cancer hallmarks in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju158. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR (2011) Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 121:2111–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI57132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapeire L, Denys H, Cocquyt V, De Wever O (2015) When fat becomes an ally of the enemy: Adipose tissue as collaborator in human breast cancer. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 23:21–38. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2015-0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denkert C, Loibl S, Noske A, et al. (2010) Tumor-associated lymphocytes as an independent predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:105–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinicrope FA, Dannenberg AJ (2011) Obesity and breast cancer prognosis: weight of the evidence. J Clin Oncol 29:4–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietze EC, Chavez TA, Seewaldt VL (2018) Obesity and triple-negative breast cancer disparities, controversies, and biology. Am J Pathol 188:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao MH, Marian C, Nie J, et al. (2011) Body mass and DNA promoter methylation in breast tumors in the western New York exposures and breast cancer study. Am J Clin Nutr 94:831–838. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.009365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mccullough LE, Chen J, White AJ, et al. (2015) Gene-specific promoter methylation status in hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer associates with postmenopausal body size and recreational physical activity. Int J Cancer Clin Res 2:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creighton CJ, Sada YH, Zhang Y, et al. (2012) A gene transcription signature of obesity in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132:993–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1595-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toro AL, Costantino NS, Shriver CD, et al. (2016) Effect of obesity on molecular characteristics of invasive breast tumors: gene expression analysis in a large cohort of female patients. BMC Obes 3:22. doi: 10.1186/s40608-016-0103-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM (2015) Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Cancer Genome Atlas (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Heng YJ, Eliassen AH, et al. (2017) Alcohol consumption and breast tumor gene expression. Breast Cancer Res 19:108. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0901-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heng YJ, Lester SC, Tse GM, et al. (2017) The molecular basis of breast cancer pathological phenotypes. J Pathol 241:375–391. doi: 10.1002/path.4847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun X, Gierach GL, Sandhu R, et al. (2013) Relationship of mammographic density and gene expression: analysis of normal breast tissue surrounding breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19:4972–4982. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Closas M, Brinton LA, Lissowska J, et al. (2006) Established breast cancer risk factors by clinically important tumour characteristics. Br J Cancer 95:123–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, Marotti J, et al. (2008) Comparison of molecular phenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 10:R67. doi: 10.1186/bcr2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, et al. (1995) The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 19:570–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. (1994) Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 23:991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, et al. (2011) Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA 306:1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W, Seok J, Mindrinos MN, et al. (2011) Human transcriptome array for high-throughput clinical studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:3707–3712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019753108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glue Grant Human Transcriptome Array Affymetrix. http://gluegrant1.stanford.edu/~DIC/GGHarray/.

- 38.Affymetrix (2007) Quality Assessment of Exon and Gene Arrays

- 39.Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W (2009) arrayQualityMetrics - A bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics 25:415–416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, et al. (2012) The SVA package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28:882–883. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. (2015) limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, et al. (2015) The molecular signatures database hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D, Smyth GK (2012) Camera: A competitive gene set test accounting for inter-gene correlation. Nucleic Acids Res 40:e133. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotunno M, Sun X, Figueroa J, et al. (2014) Parity-related molecular signatures and breast cancer subtypes by estrogen receptor status. Breast Cancer Res 16:R74. doi: 10.1186/bcr3689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casbas-Hernandez P, Sun X, Roman-Perez E, et al. (2015) Tumor intrinsic subtype is reflected in cancer-adjacent tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24:406–414. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luqmani YA, Al Azmi A, Al Bader M, et al. (2009) Modification of gene expression induced by siRNA targeting of estrogen receptor α in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol 34:231–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiang GG, Abraham RT (2007) Targeting the mTOR signaling network in cancer. Trends Mol Med 13:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, et al. (2009) A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab 9:311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borgquist S, Wirfält E, Jirström K, et al. (2007) Diet and body constitution in relation to subgroups of breast cancer defined by tumour grade, proliferation and key cell cycle regulators. Breast Cancer Res 9:R11. doi: 10.1186/bcr1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanai A, Miyagawa Y, Murase K, et al. (2013) Influence of body mass index on clinicopathological factors including estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and Ki67 expression levels in breast cancers. Int. J. Clin. Oncol 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0585-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asiedu MK, Ingle JN, Behrens MD, et al. (2011) TGFbeta/TNFalpha-mediated epithelialmesenchymal transition generates breast cancer stem cells with a claudin-low phenotype. Cancer Res 71:4707–4719. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fantuzzi G (2005) Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 115:911–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, et al. (2015) Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Mod Pathol 28:14–29. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roman-Perez E, Casbas-Hernandez P, Pirone JR, et al. (2012) Gene expression in extratumoral microenvironment predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 14:R51. doi: 10.1186/bcr3152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaysse C, L0mo J, Garred 0, et al. (2017) Inflammation of mammary adipose tissue occurs in overweight and obese patients exhibiting early-stage breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 3:19. doi: 10.1038/s41523-017-0015-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iyengar NM, Brown KA, Zhou XK, et al. (2017) Metabolic obesity, adipose inflammation and elevated breast aromatase in women with normal body mass index. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 10:235–243. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rose DP, Gracheck PJ, Vona-Davis L (2015) The interactions of obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 7:2147–2168. doi: 10.3390/cancers7040883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simpson ER, Brown KA (2013) Obesity and breast cancer: Role of inflammation and aromatase. J Mol Endocrinol 51:T51–T59. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Brien S, Anandjiwala J, Price T (1997) Differences in the estrogen content of breast adipose tissue in women by menopausal status and hormone use. Obstet Gynecol 90:244–248. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00212-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santen RJ, Yue W, Wang JP (2015) Estrogen metabolites and breast cancer. Steroids 61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santa-Maria CA, Yan J, Xie XJ, Euhus DM (2015) Aggressive estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer arising in patients with elevated body mass index. Int J Clin Oncol 20:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0712-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods. Detailed description of methodologies.

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of Nurses’ Health Study (NHS)/NHSII post-menopausal participants, stratified by estrogen receptor positive or negative disease.

Supplementary Table 2. Post-menopausal participants from The Cancer Genome Atlas with invasive breast cancer.

Supplementary Table 3. Post-menopausal participants from the Polish Breast Cancer Study with invasive breast cancer.

Supplementary Figure 1. Heatmaps displaying driver genes (p<0.10, limma analyses) that are contributing to the enrichment of the validated gene sets in A. estrogen receptor positive tumors, B. estrogen receptor negative tumors, C. estrogen receptor positive tumor-adjacent tissues and D. estrogen receptor negative tumor-adjacent tissues. Increasing color intensity of the cells indicates a smaller p value.

Supplementary File 1. Questionnaire provided to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) participants to collect lifestyle variables.

Supplementary File 2. Detailed differential gene expression analyses using limma.