Abstract

Peripheral leukocytes aggravate brain damage by releasing cytotoxic mediators that compromise blood-brain barrier function. One of the oxidants released by activated leukocytes is hypochlorous acid (HOCl) that is formed via the myeloperoxidase-H2O2-chloride system. The reaction of HOCl with the endogenous plasmalogen pool of brain endothelial cells results in the generation of 2-chlorohexadecanal (2-ClHDA), a toxic, lipid-derived electrophile that induces blood-brain barrier dysfunction in vivo. Here, we synthesized an alkynyl-analogue of 2-ClHDA, 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-al (2-ClHDyA) to identify potential protein targets in the human brain endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3. Similar to 2-ClHDA, 2-ClHDyA administration reduced cell viability/metabolic activity, induced processing of procaspase-3 and PARP, and induced endothelial barrier dysfunction at low micromolar concentrations. Protein-2-ClHDyA adducts were fluorescently labeled with tetramethylrhodamine azide (N3-TAMRA) by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition in situ, which unveiled a preferential accumulation of 2-ClHDyA adducts in mitochondria, the Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum, and endosomes. Thirtythree proteins that are subject to 2-ClHDyA-modification in hCMEC/D3 cells were identified by mass spectrometry. Identified proteins include cytoskeletal components that are central to tight junction patterning, metabolic enzymes, induction of the oxidative stress response, and electrophile damage to the caveolar/endosomal Rab machinery. A subset of the targets was validated by a combination of N3-TAMRA click chemistry and specific antibodies by fluorescence microscopy. This novel alkyne analogue is a valuable chemical tool to identify cellular organelles and protein targets of 2-ClHDA-mediated damage in settings where myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants may play a disease-propagating role.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier dysfunction, hypochlorite, myeloperoxidase, click chemistry

Introduction

The neurovascular unit separates most regions of the brain from the peripheral circulation to maintain the specialized micromilieu of the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. In capillaries brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) constitute the morphological basis of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by the formation of tight junction (TJ) and adherens junction complexes [2]. These junctional complexes prevent paracellular leakage of molecules and maintain CNS homeostasis via polarized expression of specialized transporter systems [3, 4].

Under inflammatory conditions the brain is under attack of reactive chemical species that compromise BBB function [5, 6]. Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease are chronic diseases with a significant inflammatory component [7]. These diseases manifest late in life and present a complex pathological situation wherein persistent inflammation and oxidative stress contribute to protein modification and subsequent dysfunction [7]. Accordingly, myeloperoxidase (MPO) is abundantly expressed in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseased but not in normal human brain [8, 9]. MPO is also expressed in white and grey matter plaques of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients where MPO levels were associated with early-onset MS [10]. In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a murine preclinical MS model, an MPO-activatable paramagnetic sensor [11] has been used to demonstrate MPO activity in the brain [12]. MPO was identified as a potential therapeutic target in stroke [13]; the involvement of MPO in BBB dysfunction was also suggested in bacterial meningitis [14, 15].

Under physiological conditions MPO is considered a front-line defender against phagocytosed microorganisms [16]. The MPO-H2O2-chloride system generates the potent oxidant hypochlorous acid (HOCl) that is primarily responsible for the microbicidal action of neutrophils. However, there is now compelling evidence that under chronic inflammatory conditions MPO-derived HOCl attacks amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrate components, as well as lipids [17]. Among the lipid targets that are subject to HOCl modification are the highly abundant plasmalogens, which are ether phospholipids containing a vinylether bond in sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone. The rate constants for HOCl-mediated plasmalogen modification are approx. 10-fold higher as compared to their non-vinylether containing glycerophospholipid counterparts [18]. Plasmalogen breakdown generates α-chloro fatty aldehydes (α-ClFALDs) and a remnant lysophospholipid; the prototypic fatty aldehyde is 2-chlorohexadecanal (2-ClHDA; for review see [19]). 2-ClHDA accumulates in activated neutrophils [20] and is elevated in atherosclerotic plaque material and upon myocardial infarction [21, 22]. 2-ClHDA induces neutrophil chemotaxis [20], endothelial dysfunction [23], inhibits eNOS activity [24], and activates cyclooxygenase-2 via NF-κB-mediated pathways [25]. In an earlier study we demonstrated that a single, peripheral LPS injection in mice resulted in significantly elevated cerebral MPO protein levels [26]. This treatment induced the formation of 2-ClHDA, which led to a significant decrease of brain plasmalogen content [26].

It is conceivable that oxidative modification of brain endothelial plasmalogens induces BBB dysfunction [27]. The electrophile 2-ClHDA impacts protein function by their covalent modification, thereby triggering cytotoxic and adaptive responses that are typically associated with oxidative stress. The specific molecular targets of 2-ClHDA, however, are unclear. To address this pathophysiologically important issue on the proteome level we have synthesized the clickable alkynyl analogue, 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-al (2-ClHDyA). We characterized 2-ClHDyA with respect to its effects on cellular homeostasis, its subcellular distribution, and used proteomic approaches to identify potential protein targets in human hCMEC/D3 brain endothelial cells. This analysis unveiled a specific set of both cytosolic and membrane-bound proteins, and unveiled fibronectin as a prime target of 2-ClHDA modification highlighting the susceptibility of cytoskeletal proteins towards protein alkylation damage.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Cell culture supplies were from Gibco (Life Technologies, Vienna, Austria), PAA Laboratories (Pasching, Austria), Bartelt (Graz, Austria), Costar (Vienna), or VWR (Vienna). Hexadec-7-yn-1-ol, undec-10-yn-1-ol, and sodium hydride were from Alfa Aesar (Karlsruhe, Germany). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 1,3-diaminopropane, dichloromethane, trimethylamine, oxalyl chloride, N-chlorosuccinimide, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), pentafluorobenzyl (PFB) hydroxylamine, PFB bromide, pentafluorobenzoyl (PFBoyl), sodium cyanoborohydride, dithiothreitol (DTT), and DL-proline, were from Sigma-Aldrich (Vienna). Electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) electrode arrays (8W10E+) were from Ibidi (Martinsried, Germany). 5-Tetramethylrhodamin azide (N3-TAMRA) was from Lumiprobe (Hannover, Germany). Coomassie Brilliant Blue was from Bio-Rad (Vienna). Urea, thiourea, iodoacetamide, immobilized pH gradient strips (IPG strips, pH 3–10), and Pharmalyte (pH 3–10) were from GE Healthcare (Amersham Biosciences, Vienna). Sequencing grade Trypsin was from Promega (Mannheim, Germany). Polyclonal rabbit anti-caspase-3 and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Polyclonal rabbit anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and monoclonal rabbit anti-calnexin, anti-COX IV, anti-DJ-1, anti-β-tubulin, anti-Rab-5, and anti-annexin A2 antibodies were from Cell Signaling (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany). Mouse monoclonal anti-annexin A1, anti-early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), and anti-Golgi matrix protein 130 (GM130) antibodies were from BD Biosciences (Schwechat, Austria). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG was from Sigma. Cyanine (Cy)-2 (goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG)-labeled antibodies were from Jackson Dianova (Hamburg, Germany). Immobilon Western HRP Substrate was from Merck Millipore (Merck Chemicals and Life Science, Vienna). BCA protein assay kit and Ultra V blocking reagent were from Life Technologies. Antibody diluent was from Dako (Vienna). Moviol was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Vienna), Roth (Vienna), and Merck Millipore (Vienna).

Methods

Synthesis of 2-Chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-al (2-ClHDyA)

1,3-Diaminopropane (DAP; 10 ml) was added drop-wise to NaH (60% in mineral oil; 480 mg, 12 mmol; washed three times with 5 ml hexane under argon) by gentle stirring under argon. After 1 h at 70 °C in an oil bath the reaction mixture turned brown and was allowed to cool to room temperature (RT). A solution of hexadec-7-yn-1-ol (380 mg, 1.6 mmol) dissolved in 3 ml DAP was added and stirred for 16 h at 55 °C under argon. Finally, the resulting black solution was cooled down to RT and carefully hydrolyzed with ice-cold water (5 ml). After acidification with aqueous HCl (10%, v/v) hexadec-15-yn-1-ol was extracted four times with hexane (70 ml each). The combined organic layers were washed twice with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under vacuum.

The resulting crude yellow-brown product (291.7 mg, 1.22 mmol) was oxidized to hexadec-15-yn-1-al (HDyA) via Swern oxidation using oxalyl chloride-activated DMSO. Oxalyl chloride (465.91 mg, 3.67 mmol) was added to 2 ml CH2Cl2, which was pre-cooled on dry ice. DMSO (573.56 mg, 7.34 mmol) was added drop-wise under gentle stirring and the reaction mixture was kept on dry ice for 15 min. The solution was then added to hexadec-15-yn-1-ol (in 4 ml ice-cold CH2Cl2) and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 h at -70 °C during gentle agitation under an argon atmosphere. The reaction was quenched by the addition of ice-cold trimethylamine (1.49 g, 14.68 mmol), stirred for additional 10 min at -70 °C, and allowed to warm at RT. After addition of CHCl3 (40 ml) the organic solution was washed twice with brine, and the organic layer was dried (Na2SO4) and evaporated under vacuum. The resulting crude brown reaction product was further purified using a Silica 60 column and hexane/diethyl ether (90:10, v/v) as eluent. HDyA-containing fractions were pooled and dried in a desiccator. The resulting yellow product (106.6 mg, 0.45 mmol) was chlorinated at the sn-2 position via organocatalytic α-chlorination as described previously [28] to yield 2-ClHDyA and further purified on a Silica 60 column and hexane/diethyl ether (90:10, v/v) as eluent (final yield = 93.69 mg, 0.35 mmol corresponding to 22%).

NMR Analyses

For the complete assignment of proton and carbon signals, 1D (1H and real-time J-upscaled 1H; Ref. [29]) as well as 2D (HSQC and HMBC) spectra were acquired. All spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer at 300 K, equipped with a 5 mm room temperature TXI probe with z-axis gradients, using CDCl3 as the solvent. The spectra were processed and analyzed using TopSpin 3.1 and MestReNova 8.0. Chemical shifts were referenced relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) and showed good agreement with calculated values [30].

Cell Culture

Human brain endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) [31] were cultured in collagen-coated 75 cm2 flasks in Earl’s salts-containing ‘Medium 199’ supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% (v/v) chemically defined lipid concentrate, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 1.4 μM hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 ng/ml bovine fibroblast growth factor at 37 °C (5% CO2). The split ratio of cells was 1:3 - 1:5 and only passages below 40 were used for experiments.

After preincubation over night and during cell culture experiments hCMEC/D3 cells were incubated in serum-free Earl’s salts-containing ‘Medium 199’ supplemented with 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2. 2-ClHDA and 2-ClHDyA were prepared as 250-fold stock solutions in DMSO and were applied to hCMEC/D3 cells at indicated concentrations and for the indicated time periods in serum-free culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO in the medium was 0.4% (v/v).

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-Thiazolyl)-2,5-Diphenyl-2H-Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Test

The metabolic activity of hCMEC/D3 cells treated with 2-ClHDyA, 2-ClHDA, or structural analogues was assessed using the MTT assay. Cells plated in collagen-coated 24 or 96 well plates were grown to confluence and then treated with the respective compounds up to 5 h as indicated. MTT (1.2 mM; in serum-free medium) was added to cells and incubated for 1.5 h. Cells were washed with PBS and cell lysis was performed with isopropanol/1 M HCl (25:1; v/v) on a rotary shaker at 1200 rpm for 15 min. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm on a Victor 1420 multilabel counter (Wallac) and corrected for background absorption (650 nm).

Western Blot Analysis of Caspase-3 Activation and PARP Cleavage

hCMEC/D3 cells plated in collagen-coated 6 well plates were grown to confluence and then treated with 2-ClHDyA at indicated concentrations for the indicated time periods. After washing with ice-cold PBS cells were scraped in 25 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 10 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg/ml each aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin). After sonication (2×2 min on ice) the cell debris was removed by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min) and the protein content was determined using the BCA assay. Fifty μg protein was separated by linear PAGE (150 V, reducing conditions) and electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (150 mA). Membranes were probed at 4 °C over night with primary polyclonal rabbit antibodies raised against caspase-3, PARP, or GAPDH (all diluted 1:1000 in 5% (w/v) BSA in TBS-T). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000 in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk powder in TBS-T; 2 h incubation) and subsequent Immobilon Western HRP Substrate development.

Electrical Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing

To determine the effects of 2-ClHDyA and 2-ClHDA on endothelial barrier function, impedance measurements were performed using an ECIS Z System (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY, USA). Cells were plated on collagen-coated gold electrodes of 8W10E+ arrays, grown to confluence, and set serum-free for 6 h before treatment. Impedance was recorded in real time at 1-min intervals at 4 kHz.

Uptake and Metabolism of 2-ClHDyA by hCMEC/D3 Cells

Analysis of the uptake and metabolism of 2-ClHDyA by hCMEC/D3 cells was performed as described [23] with some modifications. Cells plated in collagen-coated 6 well plates were grown to confluence and treated with 10 μM (20 nmol in 2 ml culture medium) 2-ClHDyA for the indicated time periods at 37 °C. Subsequently, lipids from 1 ml culture medium were extracted twice in 2 ml hexane/methanol (5:1; v/v) in the presence of 2-Cl[13C8]HDA, 2-chlorohexadecanoic acid (2-ClHA), and 2-chlorohexadecanol (2-ClHOH; 100 ng each), which were used as internal standards. Cellular lipids were extracted twice in the presence of the respective internal standards, 100 ng each, with 1 ml hexane/isopropanol (3:2; v/v) on a rotary shaker at 1000 rpm. After preparation of PFB-oxime- and PFB-ester derivatives, 2-ClHDyA, 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-oic acid (2-ClHyA), 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-ol (2-ClHyOH) were quantitated by negative-ion chemical ionization gas chromatography mass spectroscopy (NICI-GC-MS). A one-phase exponential decay model (Ct = C0 × e-kt) was used to fit experimental data using the GraphPad Prism package. Derivatization and NICI-GC-MS analysis were performed as described previously [23].

Detection of 2-ClHDyA-Protein Adducts using Click Chemistry

Click chemistry of protein lysates of 2-ClHDyA-treated hCMEC/D3 cells was performed using the Click-iT® Protein Reaction Buffer Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Following the click reaction proteins were precipitated and stored at -20°C until use. N3-TAMRA was used as fluorophore for protein detection via fluorescence imaging using a Typhoon 9400 scanner (Amersham Biosciences; excitation 532 nm, emission 580 nm).

Identification of Protein Targets of 2-ClHDyA

A). Separation of 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins by 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-D GE)

hCMEC/D3 cells plated in collagen-coated 10 cm culture dishes were grown to confluence and incubated in the presence of 50 μM (final concentration) 2-ClHDyA for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS and formed Schiff bases were reduced to stable amines by incubation in reduction solution (50 mM HEPES, 25 mM NaCNBH3, pH 7.4) for 90 min at 37 °C. After washing with ice-cold PBS cells were scraped off in 300 μl ‘clicking buffer’ (50 mM Tris/HCl, 1% SDS, pH 8.0); homogenates from three culture dishes were pooled, and an aliquot of 10 μl was taken for determination of protein content by the BCA assay. Cell homogenates were stored at -20 °C and 500 μg total protein was used for click chemistry, which was performed within one week after protein isolation. N3-TAMRA-clicked protein precipitates were dissolved in 200 μl sample buffer containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 1% (w/v) DTT, and 2% (v/v) Pharmalyte (pH 3-10), vortexed vigorously, and incubated at RT for 30 min. To prevent adverse isoelectric focusing (IEF) of proteins, 300 μl of reswelling solution (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% (w/v) CHAPS, 0.4% (w/v) DTT, 0.5% (v/v) Pharmalyte (pH 3-10), and 0.002% (v/v) Bromophenol blue) was added to the protein lysates. To remove insoluble material samples were centrifuged (11,000 x g, 2 min, RT) and subsequently applied to IPG strips (24 cm, linear pH range of 3-10) for rehydration which was performed for 15 h at 20 °C (30 V, maximum current set at 50 μA/strip) in ceramic strip holders using an Ettan IPGphor unit (Amersham Biosciences). IEF was carried out at 20 °C (3 h at 150 V, 3 h at 300 V, 3 h at 600 V, remaining time at 8000 V to reach a total of 50,000 Vh) and maximum current set at 50 μA/strip. Subsequently, strips were equilibrated in SDS equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 2% (w/v) SDS, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM (v/v) Tris/HCl, pH 8.8) either supplemented with 1% (w/v) DTT (first equilibration step, 15 min) or with 4.5% (w/v) iodoacetamide (IAA; second equilibration step, 15 min), each under gentle shaking. IPG strips were directly applied to self-cast 26 × 20 cm SDS gels (12%). Linear PAGE was carried out at 18 °C under reducing conditions (15 mA/gel) in an Ettan Daltsix electrophoresis unit (Amersham Biosciences). Fluorescence imaging was performed on a Typhoon 9400 scanner. Fluorescent protein spots were manually picked and tryptically digested [32].

B). Separation of 2-ClHDyA-tagged membrane proteins by 1-dimensional gel electrophoresis (1-D GE)

Confluent hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers in collagen-coated 10 cm dishes were treated with 50 μM (final concentration) 2-ClHDyA as described above and, following reduction of Schiff bases to stable amines, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and were harvested by scraping in 3 ml PBS. Cell suspensions pooled from three culture dishes were centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cellular supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, 0.25 M sucrose, 0.8 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml each aprotinin and leupeptin, pH 7.4). Following centrifugation at 450 × g for 5 min at 4 °C the cells were swelled in homogenization buffer (1.5-fold pellet volume) for 10 min on ice. Subsequently, cells were homogenized using a pre-cooled glass-glass homogenizer (50 strokes), and the post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) was collected by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. After another centrifugation step at 600 × g for 5 min the PNS was diluted with homogenization buffer to reach a final volume of 800 μl, and samples were transferred into 11 × 34 mm centrifuge tubes (Beckmann) for centrifugation at 142,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C. The supernatant representing the cytosolic fraction was discarded and the membrane pellet washed in 800 μl homogenization buffer. After centrifugation at 142,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C the resulting membrane pellet was resuspended in 60 μl ‘clicking buffer’; 10 μl were taken for determination of protein content using the BCA assay, and 100 μg protein were used for click chemistry. N3-TAMRA-clicked protein precipitates were dissolved in 50 μl of SDS-containing sample buffer, vortexed vigorously, heated for 10 min at 70 °C, and incubated at RT for another 30 min. Subsequently, proteins were separated on 20 cm PA-SDS gels (12%) at 18 °C using the Ettan Daltsix system; fluorescence imaging, picking of 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins, and tryptic digestion were performed as described above.

C). Pull-down of 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins on azide agarose beads

Confluent hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers in collagen-coated 10 cm dishes were treated with 50 μM (final concentration) 2-ClHDyA for 30 min at 37 °C followed by reduction of Schiff bases to stable amines, as described above. Cells were washed two times with ice-cold PBS and were scraped in 850 μl lysis buffer (200 mM Tris/HCl, 4% CHAPS, 1 M NaCl, 8 M urea, pH 8). Five mg protein were used for selective enrichment of 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins via covalent binding to an N3-agarose resin (50% slurry) using the Click Chemistry Capture Kit (Click Chemistry Tools, Scottsdale, AZ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Following the click reaction agarose-bound proteins were tryptically digested for 16 h and the resulting supernatant was desalted on a C-18 cartridge (Waters, Vienna). After elution using 50% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (v/v) the peptide extracts were dried using an Eppendorf concentrator and stored at -20 °C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

D). LC-MS/MS analysis of tryptic digests

Peptide extracts were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid and separated by nano-HPLC. The sample was ionized in a Finnigan nano-ESI ion source (Finnigan MAT, San Jose, CA) equipped with NanoSpray tips (PicoTipTM Emitter, New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA) and analyzed in a Thermo-Finnigan LCQ Deca XPplus ion trap mass spectrometer. The MS/MS data were analyzed by searching the NCBI public database with SpectrumMill version 2.7 (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). Detailed LC-MS/MS conditions and search parameters are given in the Supplement.

E). Detection of 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins in hCMEC/D3 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells plated in collagen-coated 4 well plastic chamber slides were grown to confluence and incubated in the presence of 2-ClHDyA at 37 °C. Schiff bases were reduced to stable amines as described above. After washing with PBS cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 10 min at RT. Subsequently, cells were washed with 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS and 2-ClHDyA-containing proteins were labeled with N3-TAMRA (via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition using the Click-iT® Cell Reaction Buffer Kit; Life Technologies), followed by confocal LSM as described below.

To validate data from the proteome screens and to identify 2-ClHDyA-accumulating compartments, colocalization studies were performed. Following the click reaction cells were washed two times with PBS and nonspecific absorption was blocked with Ultra V blocking reagent. Cells were incubated at 4 °C over night with antibodies against COX IV, GM130, calnexin, EEA1, annexin A1, annexin A2, Rab-5, DJ-1, or β-tubulin (1:100 in antibody diluent). Cy2-labeled goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG (each 1:250 in antibody diluent) were used as secondary antibodies. Cells were mounted in Moviol prior to confocal LSM.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

Images were acquired on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope with spectral detection (Leica Microsystems Inc., Mannheim, Germany), using a 63x 1.4 NA oil immersion objective. Cy2 fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and detected between 500-550 nm. TAMRA fluorescence was excited at 561 nm and detected between 570-650 nm. Cy2 and TAMRA fluorescence signal was acquired simultaneously.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins identified by 2-D GE, 1-D GE of enriched membrane protein fractions, or by N3-azide agarose pull-down were analyzed using a free trial version of the IPA software to identify potential proteomic interactions. IPA (www.ingenuity.com; https://analysis.ingenuity.com) uses a knowledge database derived from the literature to relate gene products based on their interaction and function. This software is designed to identify biological networks, global canonical pathways, and global functions. The identified proteins and their accession numbers were uploaded as .txt files into the Ingenuity software package, which uses these data to navigate the Ingenuity Pathways knowledge base and extract overlapping networks between the candidate proteins. A score of better than 2 is usually attributed to a valid network (the score represents the log probability that the network is found by random chance).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-al (2-ClHDyA)

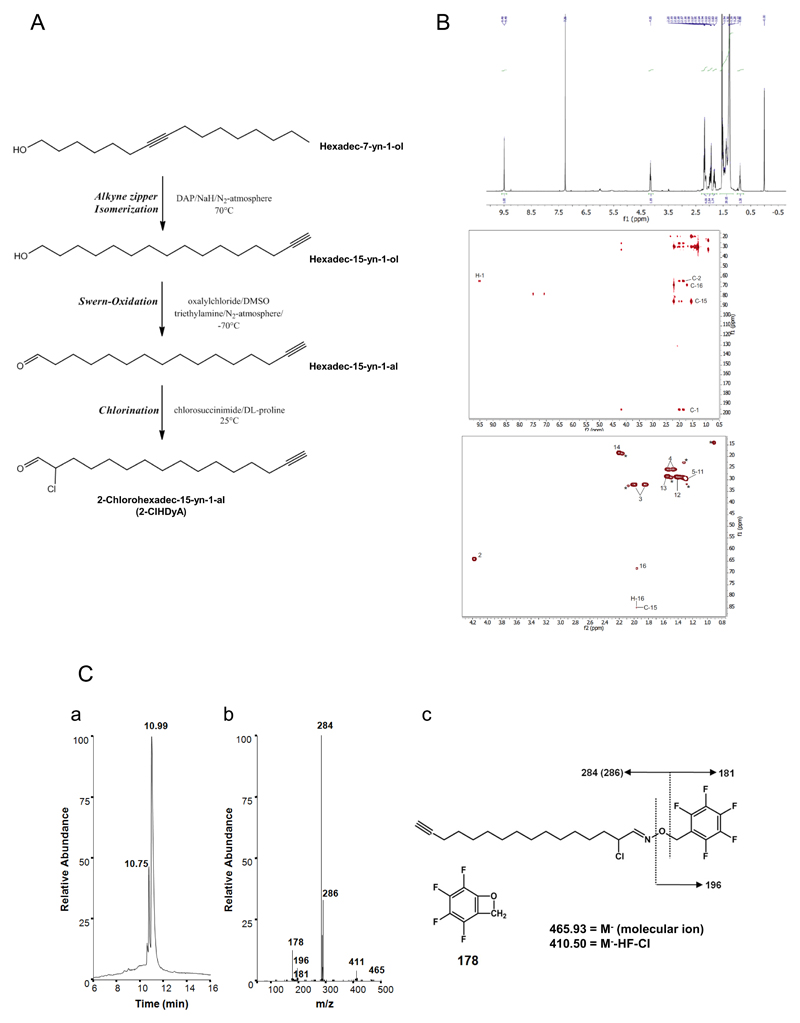

The reaction conditions for 2-ClHDyA synthesis starting from hexadec-7-yn-1-ol are shown in Fig. 1A. The terminal alkyne moiety was introduced at the ω-position via an alkyne ‘zipper’ isomerization reaction. Hexadec-15-yn-1-ol was then oxidized to HDyA followed by α-chlorination to yield 2-ClHDyA. The overall yield for 2-ClHDyA was 22%. 2-ClHDyA could be completely assigned using a combination of 1D (1H,) and 2D (HSQC and HMBC) spectra (Fig. 1B). As typically found for terminal alkyne groups, two peaks are seen in the HSQC for the proton on C-16: one to C-16 and another weaker one to C-15. For H-16 also a relative large 4-bond coupling constant was found (4J = 2.62 Hz). Scalar coupling constants were obtained using a real-time J-upscaled 1D 1H spectrum, recorded with seven-fold J-upscaling. The complete assignment of the 1H and 13C spectra for 2-ClHDyA is presented in Table 1. Further characterization of the purified product was performed by NICI-GC-MS analysis. A representative total ion chromatogram, fragment ions, and fragmentation of the corresponding 2-ClHDyA PFB-oxime derivative eluting at 10.99 is shown in Fig. 1Ca. The intensity ratio of the fragment ions at m/z 284/286 of approx. 3:1 is indicative for the presence of 35Cl/37Cl in the analyte (Fig. 1Cb). The molecular ion at m/z 465.93 (M-) as well as the fragment ions at m/z 411, 196, 181, and 178 (Fig. 1Cc) were detected only at low intensity.

Fig. 1. Synthesis strategy and analytical characterization of 2-chlorohexadec-15-yn-1-al (2-ClHDyA).

(A) Strategy of 2-ClHDyA synthesis and structures of intermediate products.

(B) 2-ClHDyA was dissolved in CDCl3 and was completely assigned using a combination of 1D (1H; upper panel) and 2D (HSQC and HMBC; middle and lower panel) spectra. The complete assignment is presented in Table 1.

(C) 2-ClHDyA was converted to the corresponding PFB-oxime derivative and subjected to NICI-GC-MS analysis in the full scan mode. The elution profile (a) and the respective ion intensity ratios (b) and proposed fragmentation pattern (c) of 2-ClHDyA are shown.

Table 1. NMR data of 2-ClHDyA acquired in DMSO-d6.

| Position: | δ(1H) [ppm] | multiplicity | J values [Hz] | δ(13C) [ppm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.49 | d | 3J=2.44 | 195.3 |

| 2 | 4.15 | ddd | 3J=2.44 / 5.49 / 8.21 | 63.8 |

| 3 | 1.83 / 1.97 | m | 32.1 | |

| 4 | 1.43 / 1.51 | m | 25.4 | |

| 5-11 | 1.28 | m | 29.4 | |

| 12 | 1.37 | m | 28.7 | |

| 13 | 1.52 | m | 28.5 | |

| 14 | 2.19 | dt | 3J=7.14, 4J=2.62 | 18.4 |

| 15 | ------ | - | 84.8 | |

| 16 | 1.94 | t | 4J=2.62 | 68.0 |

2-ClHDyA impacts on the metabolic activity of hCMEC/D3 cells

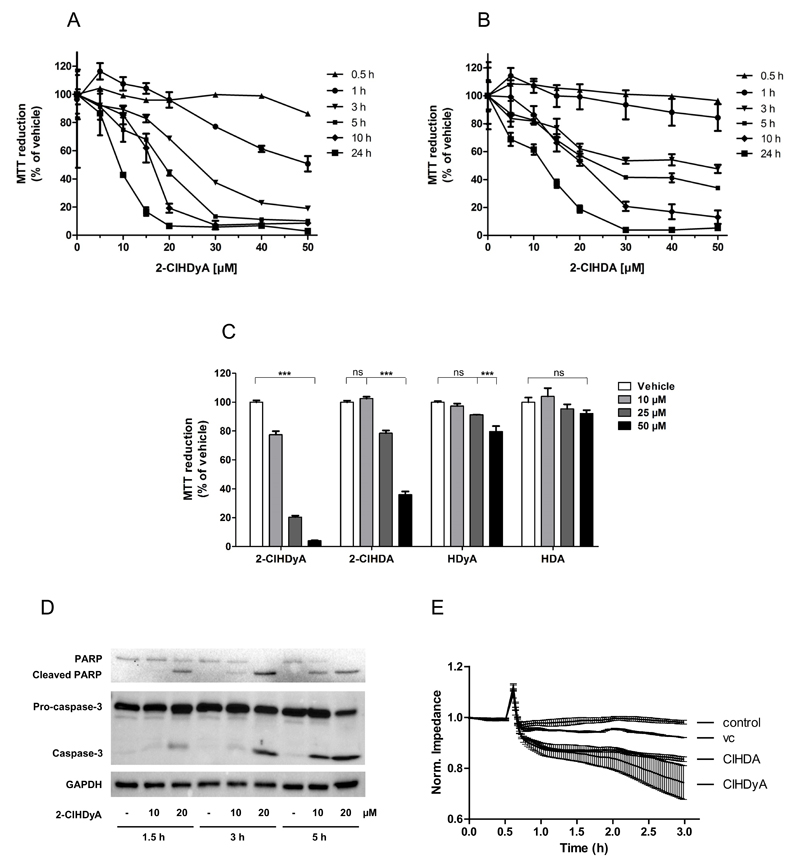

2-ClHDyA was synthesized as a functional orthologue for 2-ClHDA, thus the effects on cellular homeostasis of both compounds were studied. Using the MTT assay we found that 2-ClHDyA severely decreased metabolic activity with IC50 values of 26, 19, 16, and 9 μM at 3, 5, 10, and 24 h of cell growth, respectively (Fig. 2A). These data are very similar to the damaging effect of 2-ClHDA with IC50 values of 50, 25, 21, and 13 μM, respectively (Fig. 2B). Next we compared the toxicity of structural analogues. After 5h 2-ClHDyA reduced metabolic activity by 80% at 25 μM and 95% at 50 μM; 2-ClHDA was less effective in that respect and impaired metabolic function by 20 and 64%, respectively, at the indicated concentrations (Fig. 2C). The non-chlorinated analogues, HDyA and hexadecanal (HDA), only slightly impacted hCMEC/D3 metabolic activity, with 20 and 10% reduction at the highest concentration applied. At the cellular level, 2-ClHDyA induced cleavage of pro-caspase-3 and PARP in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2D) and compromised hCMEC/D3 cell barrier function (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Effects of 2-ClHDyA and 2-ClHDA on metabolic activity of hCMEC/D3 cells.

Metabolic activity was assessed with the MTT assay. MTT reduction is expressed as % of vehicle (0.4% DMSO, final concentration). Cells were treated with (A) 2-ClHDyA or (B) 2-ClHDA as indicated. (C) Metabolic activity of cells incubated in the presence of chlorinated (2-ClHCyA, 2-ClHDA) or non-chlorinated (HDyA, HDA) fatty aldehydes.

(D) Cells were incubated with 10 or 20 μM 2-ClHDyA for the indicated times. Cells were lysed and aliquots of protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes for subsequent detection with rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3, anti-PARP, or anti-GAPDH.

(E) Cells were plated on gold microelectrodes and cultured to confluence. Impedance of monolayers (7.5 × 104 cells) was continuously monitored at 4 kHz. After 30 min, cells were challenged with 15 μM 2-ClHDyA, 2-ClHDA, or DMSO (vehicle, ‘vc’) as indicated. Impedance values were normalized to treatment start.

Data are displayed as mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. (ns = not significant; ***p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA).

Uptake and metabolism of 2-ClHDyA in hCMEC/D3 cells

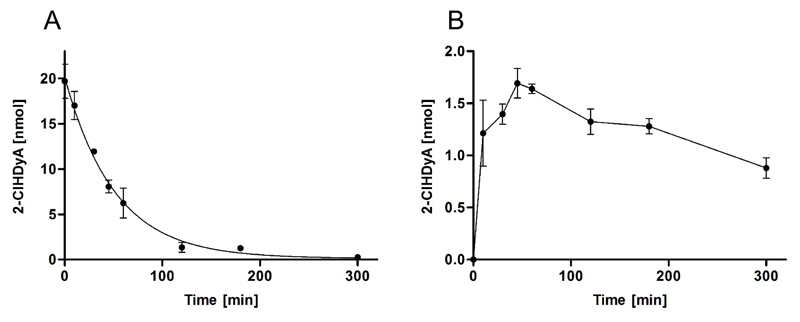

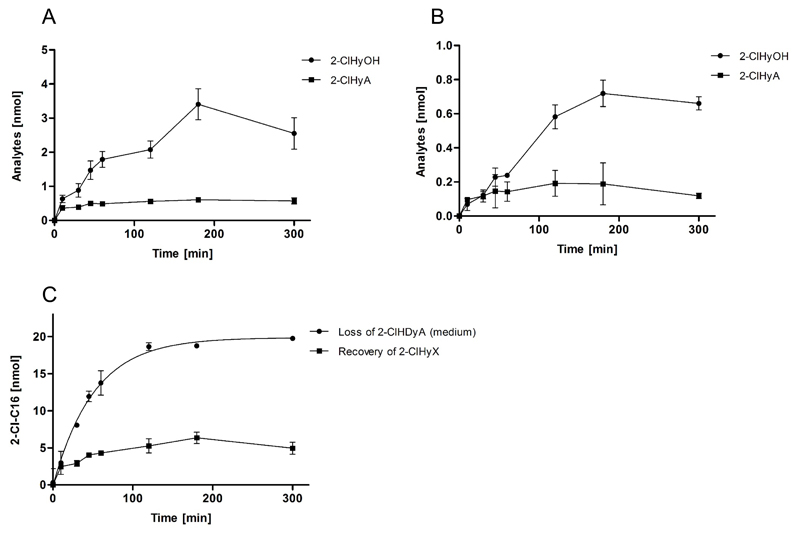

2-ClHDA undergoes redox metabolism in the fatty acid-fatty alcohol cycle giving rise to the formation of 2-chlorohexadecanoic acid (2-ClHA) and 2-chlorohexadecanol (2-ClHOH) [33]. Non-linear regression analysis (exponential decay) of 2-ClHDyA concentrations revealed a half-life in the cellular supernatant of approx. 40 min (Fig. 3A). This decrease was accompanied by intracellular accumulation with a maximum concentration of 1.7 nmol after 45 min (Fig. 3B), corresponding to a recovery of 8.5% of 2-ClHDyA initially supplied to the culture medium. This is comparable to what was observed for 2-ClHDA in porcine brain endothelial cells [23]. To unveil whether 2-ClHDyA is subject to redox metabolism via the fatty acid-fatty alcohol cycle the concentrations of 2-ClHDyOH and 2-ClHyA were determined by GC-MS. Formation of 2-ClHDyOH was more than 5-fold higher as compared to 2-ClHyA (3.4 vs 0.6 nmol; Fig. 4A). Concentrations of 2-ClHDyOH and 2-ClHyA in the supernatant were 20 and 30% (0.7 and 0.2 nmol, respectively; Fig. 4B) of those found intracellularly.

Fig. 3. Uptake of exogenous 2-ClHDyA by hCME/D3 cells.

Cells were incubated in 2 ml culture medium with 10 μM 2-ClHDyA for 5 h. At the indicated time points medium and cells were extracted in the presence of 100 ng 2-Cl[13C8]HDA as internal standard. After conversion to the corresponding PFB-oxime derivatives 2-ClHDyA concentrations of (A) the cellular supernatant and (B) hCMEC/D3 cells were quantitated by NICI-GC-MS analysis. Results are displayed as mean ± SD of triplicate determinations. Data in (A) were fitted by nonlinear regression analysis (exponential decay; R2 = 0.98).

Fig. 4. Metabolism of 2-ClHDyA by hCMEC/D3 cells.

Cells were incubated in 2 ml culture medium with 10 μM 2-ClHDyA for 5 h. At indicated time points, medium and cells were extracted in the presence of the internal standards 2-ClHA and 2-ClHOH (100 ng each). After conversion to the corresponding PFB-ester derivatives the content of 2-ClHyA and 2-ClHyOH of (A) cells and (B) the cellular supernatant was quantitated by NICI-GC-MS analysis. Results are displayed as mean values ± SD of triplicate determinations.

Data in (C) represent loss of 2-ClHDyA from the medium (Fig. 3A) versus recovery of 2-ClHyX (sum of 2-ClHDyA, 2-ClHyA, and 2-ClHDyOH) in cells and the cellular supernatant (from Figs. 3B, 4A and B).

Data from Figs. 3 and 4A and B were combined and used to establish a mass balance for analyte recovery. These calculations revealed that although 2-ClHDyA was quantitatively consumed from the medium after 5 h, the recovery of chlorinated compounds (2-ClHyX = sum of 2-ClHDyA, 2-ClHDyOH, and 2-ClHyA from cells and cellular supernatant) accounted for 25% of initially added 2-ClHDyA (Fig. 4C). These observations indicate that a significant fraction of 2-ClHDyA underwent covalent adduct formation.

2-ClHDyA induces protein alkylation in hCMEC/D3 cells

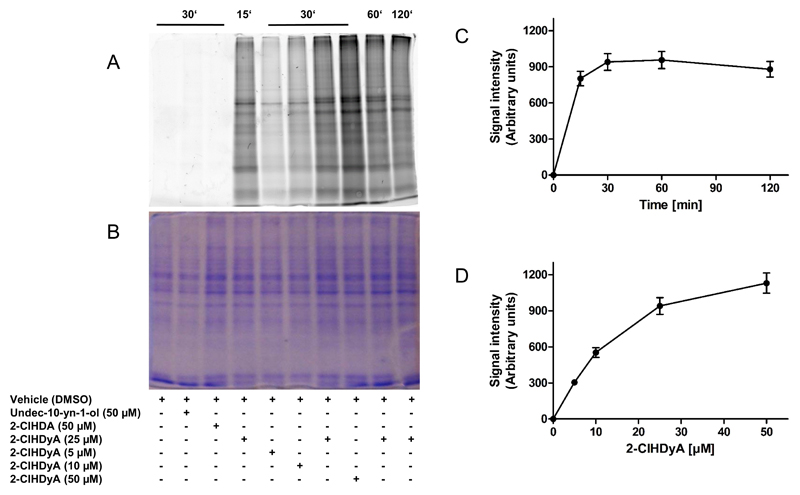

To provide experimental evidence for covalent adduct formation between 2-ClHDyA and proteins, hCMEC/D3 cells were incubated with 5-50 μM 2-ClHDyA up to 2 h. Unstable imin complexes were stabilized with NaCNBH3 and cell lysates were subjected to 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition using N3-TAMRA as the reporter fluorophore. Fluorescence imaging of the corresponding SDS gels revealed time- and concentration-dependent labeling of cellular proteins (Fig. 5A and B). Protein lysates of hCMEC/D3 incubated in the presence of the clickable terminal alkyne containing alcohol, undec-10-yn-1-ol and 2-ClHDA served as negative controls and did not show any detectable signal after fluorescence imaging (Fig. 5A). Protein alkylation by 2-ClHDyA is a rapid (maximum fluorescence observed after 30 min; Fig. 5C) and concentration-dependent process (Fig. 5D). Labeling of a distinct set of protein bands that differed in intensities from the Coomassie stained gel suggests that 2-ClHDyA-mediated protein modification is a selective rather than a random process.

Fig. 5. 2-ClHDyA forms covalent adducts with hCMEC/D3 proteins.

Cells grown on 10 cm dishes were incubated in the absence (vehicle, 0.4% DMSO, final concentration) or presence of undec-10-yn-1-ol, 2-ClHDA, or 2-ClHDyA, followed by treatment with NaCNBH3 to reduce formed Schiff bases.

(A) Cells on 10 cm dishes were lysed in 50 mM Tris/HCl, 1% SDS, pH 8.0 and aliquots were subjected to click chemistry. After precipitation proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE (forty μg cell protein/lane) and imaged on a Typhoon 9400 scanner.

(B) Loading control showing Coomassie Brilliant Blue stained protein lanes to verify equal loading.

(C) Time- and (D) concentration-dependent increase in fluorescence intensities of protein lanes from the image shown in (A).

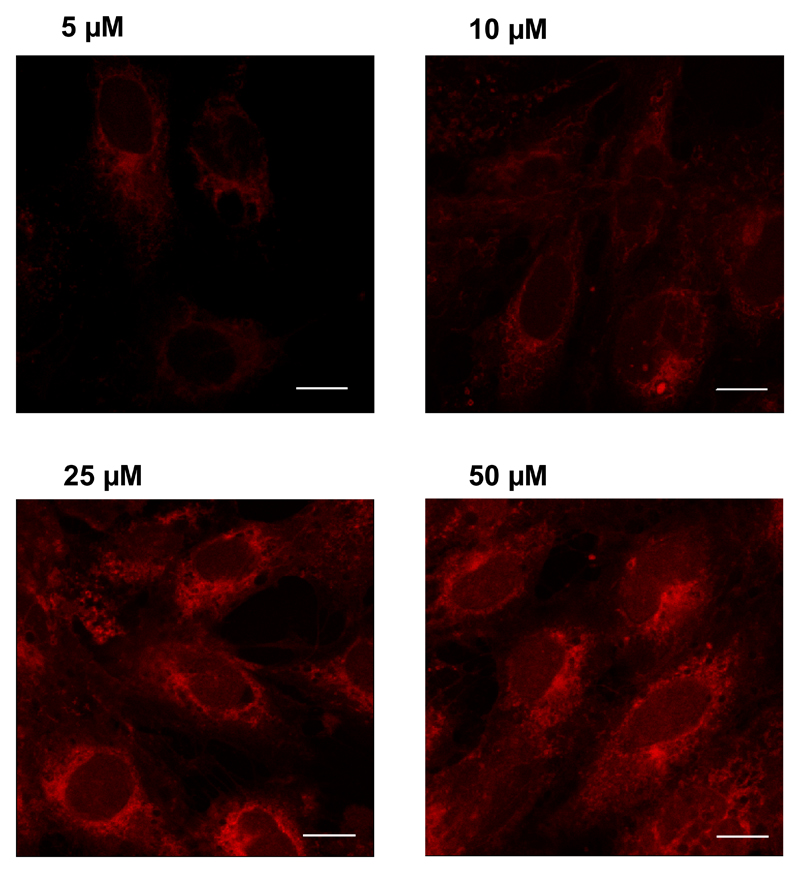

Selective intracellular accumulation was also suggested by fluorescence microscopy: living cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of 2-ClHDyA, permeabilized, clicked with N3-TAMRA, and visualized by confocal LSM. After 30 min incubation intracellular accumulation of 2-ClHDyA-protein adducts was detected in a concentration-dependent manner, with highest fluorescence intensity observed at perinuclear regions (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Visualization of protein-2-ClHDyA-TAMRA adducts by confocal laser scanning microscopy in hCMEC/D3 cells.

Cells grown on 4 well plastic chamber slides were incubated in the presence of the indicated 2-ClHDyA concentrations for 30 min, fixed in methanol, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and subjected to click chemistry with N3-TAMRA. Cells were mounted in Moviol and analyzed by confocal LSM. All images were acquired using the same microscope settings. Bars = 10 μm.

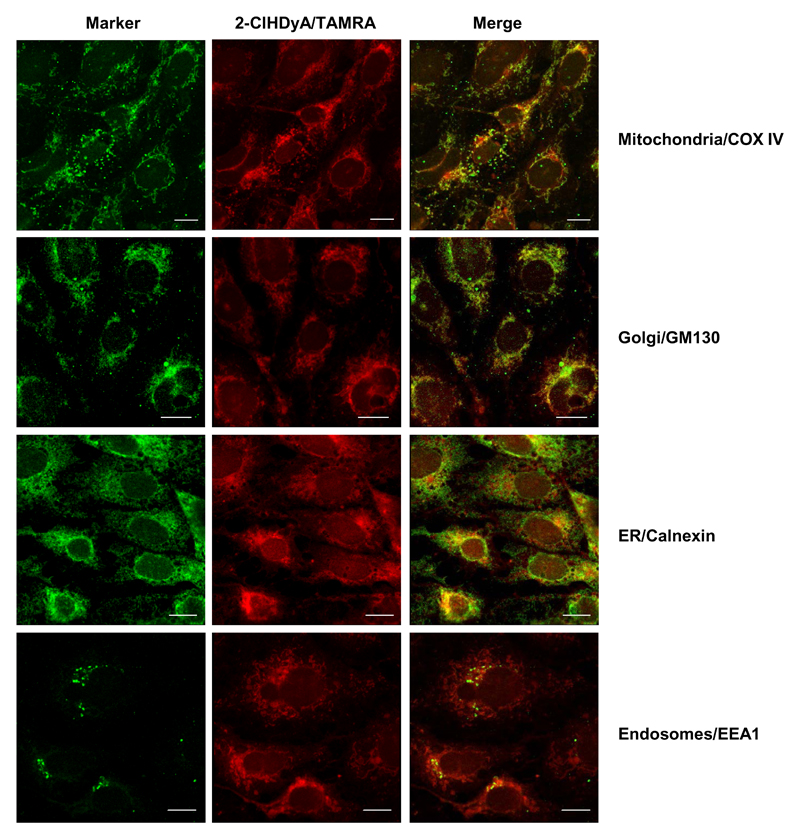

Subcellular accumulation of 2-ClHDyA

To further identify intracellular compartments where 2-ClHDyA-protein adducts accumulate we used organelle-specific marker antibodies. These immunofluorescence studies revealed that 2-ClHDyA targets mitochondria, the Golgi, the ER, and, to a lesser extent, endosomal compartments (Fig. 7). Only faint fluorescence was observed at the plasma membrane (an overexposed micrograph is shown in Fig. S1). These data suggest that intracellular membrane proteins may be the preferred targets for 2-ClHDyA attack.

Fig. 7. Subcellular localization of 2-ClHDyA-TAMRA adducts in hCMEC/D3 cells.

Cells grown on 4 well plastic chamber slides were incubated in the presence of 25 μM 2-ClHDyA for 30 min followed by treatment with NaCNBH3 to reduce Schiff bases. After treatment cells were fixed and permeabilized prior to click chemistry with N3-TAMRA. Subsequently, cells were incubated with primary antibodies against cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 (COX IV; mitochondria), Golgin subfamily A member 2 (GM130; Golgi), Calnexin (ER), and early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1; endosomes). Following incubation with Cy2-labeled secondary antibodies cells were mounted in Moviol and analyzed by confocal LSM. Bars = 10 μm.

Identification of potential protein targets for covalent 2-ClHDyA-modification

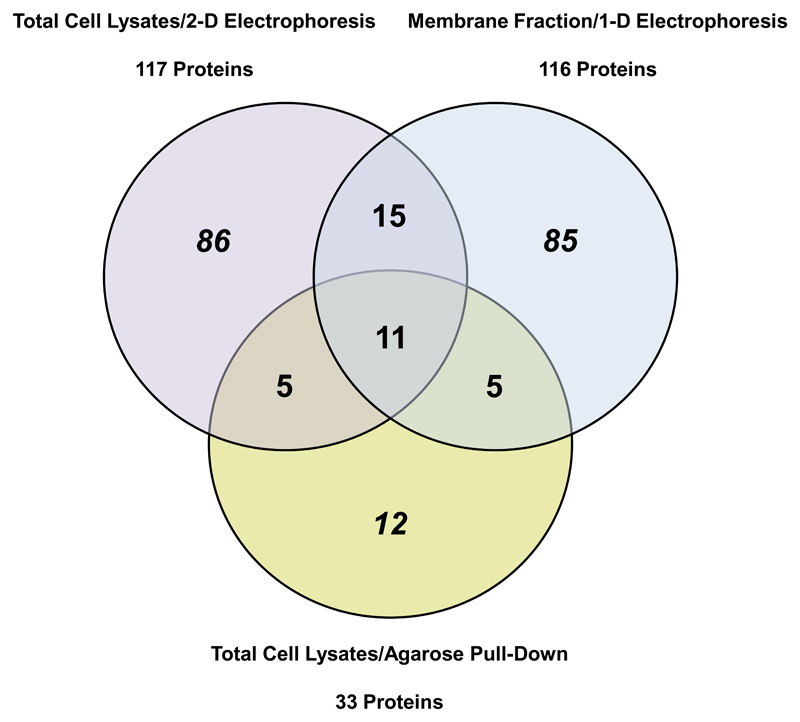

To further identify specific protein targets, three different proteomic approaches were taken: i) Cells were incubated with 2-ClHDyA, cellular lysates were clicked with N3-TAMRA, separated by 2-D GE, and proteins in fluorescent spots were identified. ii) After 2-ClHDyA incubation of cells, membrane fractions were isolated by differential centrifugation, clicked with N3-TAMRA and separated by 1-D GE; proteins in fluorescent bands were identified. iii) 2-ClHDyA-containing proteins were directly bound to N3-agarose, subjected to on-bead tryptic digestion and identified. Each of these approaches has distinct advantages but also limitations; nevertheless, significant overlap of proteins identified by these approaches supports the validity of the approach.

Representative 2-D- and 1-D-gel grey scale images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2A and B. Supplementary Table S1 lists the proteins identified by 2-D GE, Table S2 the proteins identified in total membrane fractions, and Table S3 the results from the N3-agarose pull-down. The tables also provide information on spot/band number, number of acquired spectra, peptide coverage, MS/MS search score, amino acid coverage, theoretical and experimental molecular mass, and, in case of 2-D GE, theoretical and experimental pI. Moreover, Table S3 contains information regarding subcellular localization of proteins identified via N3-agarose pull-down.

By 2-D GE (total cellular lysates) 117 distinct proteins and by 1-D GE (membrane protein fraction) 116 distinct proteins were identified in 2-ClHDyA-treated cells. Using protein enrichment on N3-agarose we detected a total number of 33 proteins out of which 5 proteins were also identified in total cell lysates or enriched membrane fractions. Eleven proteins were common to all three experimental approaches (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Overlaps between the different proteomic approaches.

Venn diagram showing overlap of targets of 2-ClHDyA adduct formation that were identified in total cell lysates by 2-D GE (purple), the enriched membrane protein fraction after 1-D SDS-PAGE (blue), and total cell lysates by N3-agarose pull-down (yellow). The numbers represent total proteins identified in triplicate analysis of each experimental approach. Overlaps between different methods are represented by the numbers in the corresponding segments. A total of 11 identified proteins were common to all approaches.

To generate biologically meaningful networks from the identified proteins IPA was performed. Only proteins that were identified in two out of three independent experiments with a minimal MS/MS search score of 20 were included in the analysis. Interestingly, fibronectin, which was identified in all three proteomic approaches, represents a central hub in all IPA networks which yielded the highest score for 2-ClHDyA target proteins identified via 2-D GE (total cellular lysates), 1-D GE (membrane protein fraction), and after the N3-agarose pull-down. Fibronectin binds cellular surfaces and compounds including collagen, DNA, and actin. Moreover, fibronectin is involved in cytoskeleton signaling, cell migration, adhesion, junctional assembly, maintenance of cell shape, opsonization, and integrin binding.

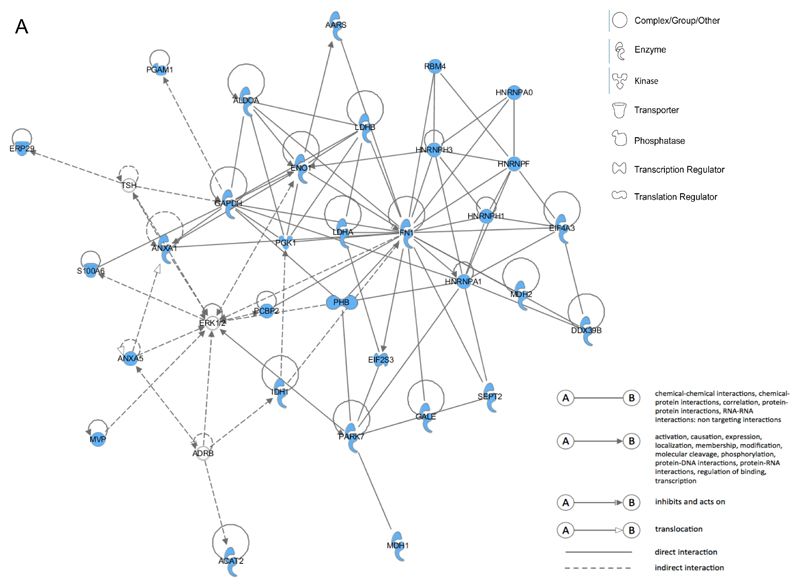

For 2-D GE data IPA analysis retrieved the network RNA Post-Translational Modification, Carbohydrate Metabolism, and Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Interaction (score = 76; Fig. 9A). This network consists of 11 identified focus proteins that are involved in metabolic processes such as glycolysis, citric acid cycle, galactose and fatty acid metabolism, synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, and amino acid catabolism. Thus, protein alkylation damage of these enzymes is likely to severely impact on the energy status of 2-ClHDyA-treated hCMEC/D3 cells. Moreover, focus proteins in this network that were identified in this study belong to the family of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein family, which are involved in transcription and post-translational protein modification.

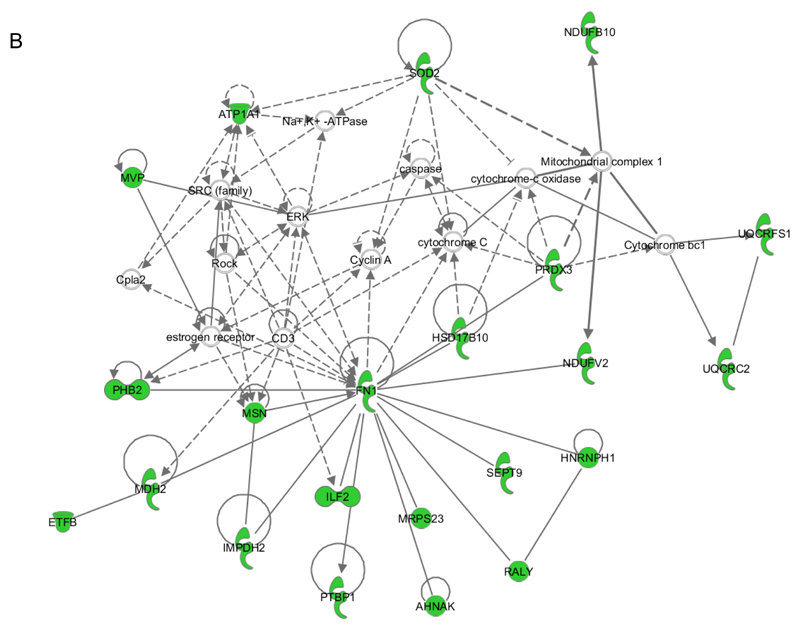

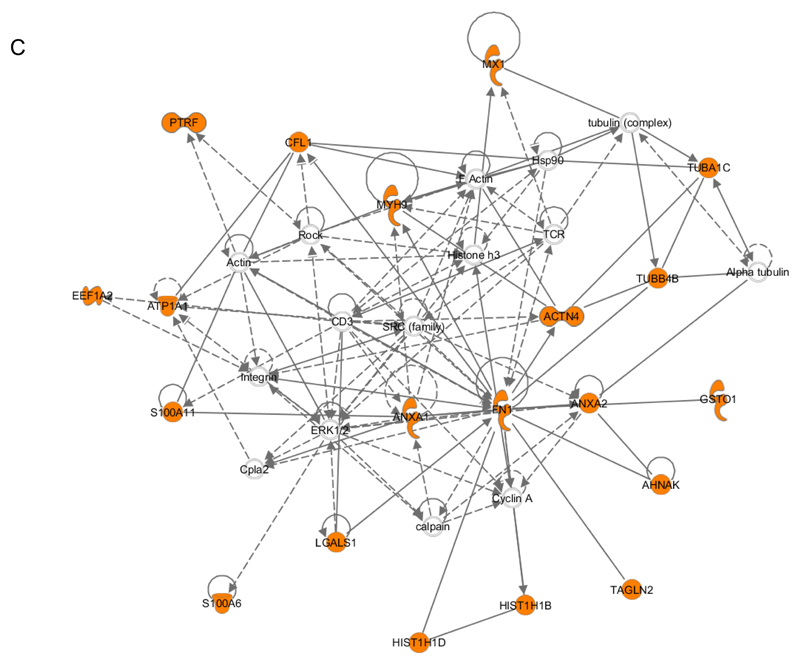

Fig. 9. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA).

Networks of proteins were generated through IPA. Proteins (displayed as abbreviated gene names) identified in (A) total cell lysates by 2-D GE, (B) enriched membrane fractions separated by 1-D SDS-PAGE, and after (C) N3-agarose pull-down were connected via the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base. Solid lines represent direct interaction and dashed lines indirect interaction.

A. Network A contains 32 identified proteins (out of 35 components) involved in RNA Post-Translational Modification, Carbohydrate Metabolism, and Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Interaction (score = 76).

AARS, alanyl-tRNA synthetase; PGAM1, phosphoglycerate mutase 1; ALDOA, aldolase A, fructose-bisphosphate; RBM4, RNA binding motif protein 4; ERP29, endoplasmic reticulum protein 29; LDHB, lactate dehydrogenase B; HNRNPA0, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A0; ENO1, enolase 1 (alpha); HNRNPH3, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3; HNRNPF, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; S100A6, S100 calcium binding protein A6; ANXA1, annexin A1; PGK1, phosphoglycerate kinase 1; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; FN1, fibronectin 1; HNRNPH1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1; EIF4A3, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 A3; PCBP2, poly(rC) binding protein 2; PHB, prohibitin; HNRNPA1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase 2, NAD (mitochondrial); DDX39B, DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 39B; EIF2S3, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2, subunit 3 gamma; MVP, major vault protein; ADRB, beta adrenergic receptor; IDH1, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+), soluble; PARK7, Parkinson protein 7; GALE, UDP-galactose-4-epimerase; SEPT2, septin 2; ACAT2, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2; MDH1, malate dehydrogenase 1, NAD (soluble).

B. Network B contains 22 identified proteins (out of 35 components) involved in Post-Tranlational Modification, Protein Synthesis, and Cellular Movement (score = 46).

NDUFB10, NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 10; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial; ATPA1, ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 1 polypeptide; MVP, major vault protein; Capla2, calcium-dependent phospholipase A2; PRDX3, peroxiredoxin 3; UQCRFS1, ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, Rieske iron-sulfur polypeptide 1; HSD17B10, hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase; PHB2, prohibitin 2; FN1, fibronectin 1; NDUFV2, NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein; UQCRC2, ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein II; ETFB, electron-transfer-flavoprotein, beta polypeptide; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase 2, NAD (mitochondrial); MSN, moesin; IMPDH2, IMP (inosine 5'-monophosphate) dehydrogenase 2; ILF2, interleukin enhancer binding factor 2; MRPS23, mitochondrial ribosomal protein S23; SEPT9, septin 9; HNRNPH1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1; PTBP1, polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1; AHNAK, AHNAK nucleoprotein; RALY, RALY heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein.

C. Network C contains 20 identified proteins (out of 35 components) involved in Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Inflammatory Disease, and Inflammatory Response (score = 53).

MX1, MX dynamin-like GTPase 1; PTRF, polymerase I and transcript release factor; CFL, cofilin; TUBA1C, tubulin, alpha 1c; MYH9, myosin, heavy chain 9, non-muscle; TCR, T-cell receptor; TUBB4B, tubulin, beta 4B; EEF1A2, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 2; ATP1A1, ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 1 polypeptide; ACTN4, actinin, alpha 4; S100A11, S100 calcium binding protein A11; ANXA1, annexin A1; FN1, fibronectin 1; ANXA2, annexin A2; GSTO1, glutathione S-transferase omega 1; Cpla2, calcium-dependent phospholipase A2; LGALS1, lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 1; AHNAK, AHNAK nucleoprotein; S100A6, S100 calcium binding protein A6; HIST1H1D, histone cluster 1, H1d; HIST1H1B, histone cluster 1, H1b; TAGLN2, transgelin 2.

For the enriched membrane fraction the highest score in IPA analysis was obtained for Post-Translational Modification, Protein Synthesis, and Cellular Movement (score = 46; Fig. 9B). In this network many proteins that directly (i. e. septin-9 or moesin) or indirectly (i. e. AHNAK nucleoprotein, polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1) interact with fibronectin regulate the formation of the cytoskeleton which explains, at least in part, the significant loss of endothelial barrier function in response to 2-ClHDyA treatment (Fig. 2). Interestingly, other 2-ClHDyA-tagged proteins identified in this experimental approach are enzymes of the mitochondrial respiratory chain such as NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein, NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein II, ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, or electron-transfer-flavoprotein, beta polypeptide which parallels results obtained after 2-D GE and suggests energy deprivation in response to 2-ClHDyA treatment. This assumption is further supported by the significant 2-ClHDyA-TAMRA staining of mitochondria (Fig. 7). To address unspecific protein binding in the pull-down approach, cellular lysates were incubated with N3-agarose, which was then processed as described for the click procedure. During these experiments we have identified serum albumin as the only unspecifically pulled-down protein (Table S4).

Protein targets identified by N3-agarose pull-down yielded the highest IPA score (53) for Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Inflammatory Disease, and Inflammatory Response (Fig. 9C). In this network, fibronectin once again serves the central hub interacting with cytoskeletal proteins such as α- or β-tubulin or proteins responsible for cytoskeletal arrangement. Mapping of 2-ClHDyA-tagged focus proteins (20 out of 33 identified via N3-agarose pull-down) into this network further highlights the susceptibility of cytoskeletal proteins towards protein alkylation damage.

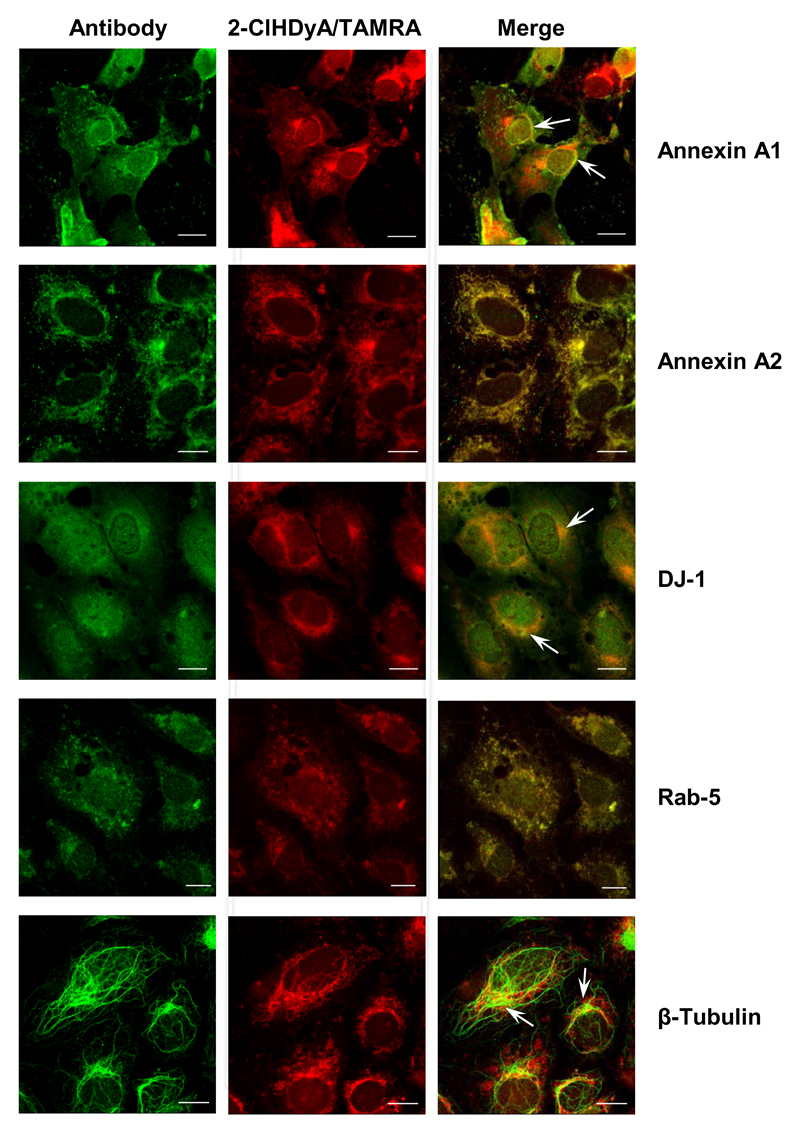

Colocalization studies

To further support data from the proteome screens by immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were treated with 2-ClHDyA, permeabilized, clicked with N3-TAMRA, and incubated with the indicated antibodies. For the selected proteins (annexin A1, annexin A2, DJ-1, Rab-5, and β-tubulin) colocalization with protein-2-ClHDyA-TAMRA adducts could be confirmed (Fig. 10). These findings support and backup the validity of proteome results obtained after pull-down with N3-agarose.

Fig. 10. Colocalization studies of selected protein-2-ClHDA-TAMRA adducts.

hCMEC/D3 cells grown on 4 well plastic chamber slides were incubated in the presence of 25 μM 2-ClHDyA for 30 min followed by treatment with NaCNBH3 to reduce Schiff bases. Cells were fixed and permeabilized prior to click chemistry and incubated with primary antibodies against annexin A1, annexin A2, DJ-1 (PARK-7), Rab-5, and β-tubulin. All of these proteins (except Rab-5) were identified in the N3-agarose pull-down experiments; Table S3). Following incubation with Cy2-labeled secondary antibodies cells were analyzed by confocal LSM. Bars = 10 μm.

Discussion

Characterization of 2-ClHDA-modified proteins is a challenging task since only a small fraction of the cellular proteome is modified and the adduct may be lost during protein preparation. Therefore we have synthesized an alkyne-containing 2-ClHDA analogue that allows i) covalent attachment of N3-TAMRA as reporter fluorophore, ii) identification of subcellular organelles where protein adducts accumulate, iii) enrichment of protein adducts via pull-down strategies, and iv) colocalization studies of 2-ClHDyA-TAMRA containing proteins with antibodies directed against proteins identified in the proteome screen. The strategy for 2-ClHDyA synthesis shown in Fig. 1A was straightforward, yielded the expected product in reasonable yields, and the alkyne group apparently induced only minimal perturbation of the parent compound, differing by only four terminal hydrogen atoms.

2-ClHDyA treatment severely impacted hCMEC/D3 cell homeostasis: MTT reduction was severely reduced and toxicity was highest for compounds containing both, a chlorine atom and an aldehyde group, while the non-chlorinated analogues HDA and HDyA showed less toxic properties, comparable to earlier observations [23]. 2-ClHDyA decreased endothelial barrier function, and induced apoptosis via caspase-3 and PARP activation (Fig. 2). In addition 2-ClHDyA was converted to the corresponding redox metabolites, 2-ClHyA and 2-ClHyOH (Figs. 3 and 4). These findings indicate that 2-ClHDyA mimics metabolic properties as observed for 2-ClHDA that is formed in vivo under inflammatory conditions, thus serving as an excellent and biochemically tractable substitute.

Incomplete recovery of chlorinated metabolites (only 25% of initially added 2-ClHDyA; Fig. 4) indicates that covalent adduct formation must occur. In addition to GSH [34] and phosphatidylethanolamine [35] also proteins [36] are targeted by MPO-derived oxidants. As described for other alkyne-modified lipid electrophiles 2-ClHDyA-mediated protein modification is a selective, fast, and saturable event as revealed by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of N3-TAMRA and subsequent fluorescence imaging of SDS gels (Fig. 5). This is reminiscent of what was reported for oxidized phospholipids in macrophages [37] and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)-protein adduct formation in colon carcinoma cells [38]. Fluorescence microscopy revealed selective rather than random accumulation of the 2-ClHDyA-TAMRA containing protein adducts at perinuclear regions. Subcellular distribution analysis demonstrated colocalization of TAMRA-clicked 2-ClHDyA adducts and the respective organelle-specific marker antibodies in mitochondria, the Golgi, ER, and endosomes (Fig. 7). This subcellular distribution of 2-ClHDyA is compatible with other reports demonstrating mitochondrial accumulation of HNE (a reactive aldehyde) and HNE-modified proteins [39, 40]. HNE induces the ER stress response in different cell types [41, 42] and similar findings were made for 2-ClHA-treated monocytes [43]. On the other hand, the more complex lipid peroxidation product 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleroyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine accumulates at the plasma membrane and in lysosomes, while no localization in the ER or mitochondria was observed [44].

To identify 2-ClHDyA protein targets we have pursued three different analytical strategies, all with their own inherent caveats. First, 2-D GE poorly represents low abundance proteins and multiple proteins can co-migrate in one single spot [45]. Therefore 2-D GE results most likely represent an overestimation of 2-ClHDyA targets. A 1-D GE approach, which may also suffer from co-migration of multiple proteins in one band, was applied for enriched membrane-associated proteins. Finally, we used an affinity pull-down approach with N3-agarose beads representing a very specific method to identify targets of biologically active compounds [46]. Non-specific protein binding to agarose beads [47] was negligible, as only serum albumin was identified in the pull-down from untreated cell extracts (Table S4).

Overlap between all three proteome approaches

Eleven proteins were identified by all of the above-mentioned proteomic approaches (Table 2; Fig. 8). Of these at least five proteins are directly involved in TJ formation and/or maintenance. α-actinin-4 recruits junctional Rab-13 binding protein (JRAB) to cell-cell junctions where it supports the formation of functional TJ [48]. Of the annexin family, annexin A1, -A2, and -A3 play important roles during TJ establishment [49, 50]. The same holds true for tubulins: Integral barrier proteins (claudins, occludin, or JAM-A) are linked to peripheral scaffolding proteins, which are in turn linked to microtubules thereby generating functional TJs [51]. Fibronectin plays an important role in regulating cell-matrix adhesion and promotes brain capillary endothelial cell survival and proliferation in an integrin-dependent manner [52] while myosin-9, a motor protein, is involved in angiogenesis [53]. PARK7 (DJ-1), a multifunctional protein involved in oxidative stress response [54], cell death decisions [55], and synucleopathies [56] was among the identified candidates. Of note, HNE-adducted DJ-1 levels are higher in blood of Parkinson’s disease patients as compared to healthy controls [57]. All of these proteins play important roles in endothelial cell biology and electrophile attack by 2-ClHDyA is likely to compromise endothelial barrier function as observed in this study.

Table 2. Proteins identified in all three proteomic approaches.

| Protein name | Accession number | Molecular Mass (Da) | pI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-actinin-4 | O43707.2 | 104854.6 | 5.27 |

| Annexin A1 | P04083.2 | 38714.5 | 6.57 |

| Annexin A2 | P07355.2 | 38604.2 | 7.58 |

| Annexin A3 | P12429.3 | 36375.5 | 5.63 |

| Fibronectin | P02751.4 | 262625.9 | 5.46 |

| Interferon-induced GTP binding protein Mx1 | P20591.4 | 75520.7 | 5.60 |

| Myosin-9 | P35579.4 | 226533.4 | 5.50 |

| POTE ankyrin domain family member F | A5A3E0.2 | 121445.3 | 5.83 |

| Protein DJ-1 | Q99497.2 | 19891.2 | 6.33 |

| Tubulin alpha-1C chain | Q9BQE3.1 | 49895.6 | 4.96 |

| Tubulin beta-4B chain | P68371.1 | 49831.3 | 4.79 |

Overlap of proteins identified by 2-D GE and in the membrane fraction

A closer comparison of proteins present in TAMRA-clicked spots after 2-D GE and 1-D GE revealed 26 common proteins (Fig. 8) that were identified by either method. In addition to the proteins mentioned above four metabolic enzymes, three from glycolysis (GAPDH, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A, and lactate dehydrogenase) and one from the TCA cycle (malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial) were identified in both experimental settings (Table 3). Data from the MTT test are consistent with an electrophile damage of these enzymes, leading to metabolically compromised phenotypes. The remaining proteins in this group take functions in stress response, immune function, ribosomal function, signal transduction, nucleic acid metabolism, and apoptosis.

Table 3. Overlapping proteins identified by 2-D GE and 1-D SDS-PAGE.

| Protein name | Accession number | Molecular Mass (Da) | pI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | P05388.1 | 34273.7 | 5.72 |

| Calpain small subunit 1 | P04632.1 | 28315.9 | 5.05 |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | P04075.2 | 39420.2 | 8.30 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | P04406.3 | 36053.4 | 8.57 |

| Heat shock protein beta-1 | P04792.2 | 22782.6 | 5.98 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | P31943.4 | 49229.7 | 5.89 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | P22626.2 | 37429.9 | 8.97 |

| HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, A-11 alpha chain | P13746.1 | 40937.0 | 5.77 |

| Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 2 | Q12905.2 | 43062.4 | 5.19 |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | P00338.2 | 36688.9 | 8.44 |

| Major vault protein | Q14764.4 | 99327.3 | 5.34 |

| Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | P40926.3 | 35503.5 | 8.92 |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | Q15366.1 | 38580.3 | 6.33 |

| Thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase, mitochondrial | P30048.3 | 27692.8 | 7.67 |

| Vimentin | P08670.4 | 53651.9 | 5.06 |

Overlap of proteins identified by 2-D GE and N3-agarose pull-down

In addition to the 11 proteins identified in all three proteomic approaches, five were identified in both the 2-D GE and the agarose pull-down experiments (Table 4): Of these galectin-1 plays a role in angiogenesis by facilitating interaction between endothelial cells and other cell types and/or the extracellular matrix [58]. Glutathione S-transferase Ω-1 and lactoylglutathione lyase contribute to intracellular redox homeostasis and prevent endothelial dysfunction [59]. In addition to the proteins that contribute to the maintenance of the actin/tubulin cytoskeleton which were identified by all three proteomic approaches, the Ca2+-binding protein S100-A6 participates in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts [60] and regulates cell-cycle progression in endothelial cells [61]. 2-ClHDyA-mediated alkylation damage of acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase may impact on several metabolic pathways, e.g. fatty acid metabolism, synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies, and amino acid metabolism and is thus likely to have pleiotropic phenotypic consequences.

Table 4. Overlapping proteins identified by 2-D GE and N3-agarose pull-down.

Overlap of proteins in the membrane fraction and N3-agarose pull-down

Targets identified in this group (Table 5) include the plasma membrane proteins BASP1, AHNAK, ATP1A1, caveolae (PTRF), or intracellular vesicles (TAGL-2). Among these proteins ATP1A1 is expressed in embryonic porcine brain [62] and in capillaries of the ear where ATP1A1 interacts with PKCeta and occludin, a member of the blood-labyrinth barrier [63]. In terms of 2-ClHDyA internalization, PTRF (cavin-1) might be a potentially important candidate: Cavin-1 is an essential scaffold component of caveolae [64], which are cellular membrane structures representing small omega-shaped invaginations of the plasma membrane. Caveolae are highly abundant in endothelial cells and play an important role in cellular lipid metabolism [65]. Modification of cavin-1 may therefore generate 2-ClHDyA-loaded caveolae that enter the endosomal pathway, thus facilitating internalization and intracellular distribution of 2-ClHDyA. BASP1 was shown to be present in caveolae and raft enriched membrane fraction of human endothelial cells [66] and regulates the formation of cell-cell contacts in HUVECs [67], further providing strong support that protein alkylation by 2-ClHDyA impacts on endocytosis and barrier integrity. Colocalization studies for a selected set of proteins by confocal LSM further supported results of the proteome screens.

Table 5. Overlapping proteins identified by 1-D SDS-PAGE and N3-agarose pull-down.

| Protein name | Accession number | Molecular Mass (Da) | pI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain acid soluble protein 1 | P80723.2 | 22693.5 | 4.64 |

| Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK | Q09666.2 | 629104.8 | 5.80 |

| Polymerase I and transcript release factor | Q6NZI2.1 | 43476.3 | 5.51 |

| Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-1 | P05023.1 | 112896.8 | 5.33 |

| Transgelin-2 | P37802.3 | 22391.6 | 8.41 |

In summary, subcellular localization and proteome data obtained in this study suggest that the detrimental effects of 2-ClHDyA-induced electrophile damage on human brain endothelial cells involves multifactorial pathways. These include modification of cytoskeletal components that are central to TJ patterning, modification of metabolic enzymes, induction of the oxidative stress response, electrophile damage to the caveolar/endosomal Rab machinery; ultimately, cell damage may evoke induction of apoptosis. These findings indicate that inhibition of MPO in neurodegenerative diseases involving BBB dysfunction represents a valuable therapeutic option to impede 2-ClHDA-mediated electrophile damage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Financial support was provided by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; SFB LIPOTOX F3007, and DK MOLIN-W1241), the Medical University of Graz (N.K. within DK-W1241), and BioTechMed Graz.

References

- [1].Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57:178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:173–185. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:723–738. doi: 10.1038/nrn3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Coisne C, Engelhardt B. Tight junctions in brain barriers during central nervous system inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1285–1303. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97:1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Freeman LR, Keller JN. Oxidative stress and cerebral endothelial cells: Regulation of the blood-brain-barrier and antioxidant based interventions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maki RA, Tyurin VA, Lyon RC, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST, Kagan VE, Reynolds WF. Aberrant expression of myeloperoxidase in astrocytes promotes phospholipid oxidation and memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3158–3169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Choi DK, Pennathur S, Perier C, Tieu K, Teismann P, Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Vonsattel JP, Heinecke JW, Przedborski S. Ablation of the inflammatory enzyme myeloperoxidase mitigates features of Parkinson's disease in mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6594–6600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0970-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gray E, Thomas TL, Betmouni S, Scolding N, Love S. Elevated activity and microglial expression of myeloperoxidase in demyelinated cerebral cortex in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen JW, Breckwoldt MO, Aikawa E, Chiang G, Weissleder R. Myeloperoxidase-targeted imaging of active inflammatory lesions in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain. 2008;131:1123–1133. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Forghani R, Wojtkiewicz GR, Zhang Y, Seeburg D, Bautz BR, Pulli B, Milewski AR, Atkinson WL, Iwamoto Y, Zhang ER, Etzrodt M, et al. Demyelinating diseases: myeloperoxidase as an imaging biomarker and therapeutic target. Radiology. 2012;263:451–460. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Forghani R, Kim HJ, Wojtkiewicz GR, Bure L, Wu Y, Hayase M, Wei Y, Zheng Y, Moskowitz MA, Chen JW. Myeloperoxidase propagates damage and is a potential therapeutic target for subacute stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:485–493. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miric D, Katanic R, Kisic B, Zoric L, Miric B, Mitic R, Dragojevic I. Oxidative stress and myeloperoxidase activity during bacterial meningitis: effects of febrile episodes and the BBB permeability. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Christen S, Schaper M, Lykkesfeldt J, Siegenthaler C, Bifrare YD, Banic S, Leib SL, Tauber MG. Oxidative stress in brain during experimental bacterial meningitis: differential effects of alpha-phenyl-tert-butyl nitrone and N-acetylcysteine treatment. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:754–762. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Klebanoff SJ, Kettle AJ, Rosen H, Winterbourn CC, Nauseef WM. Myeloperoxidase: a front-line defender against phagocytosed microorganisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:185–198. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0712349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Davies MJ, Hawkins CL, Pattison DI, Rees MD. Mammalian heme peroxidases: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1199–1234. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Skaff O, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. The vinyl ether linkages of plasmalogens are favored targets for myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants: a kinetic study. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8237–8245. doi: 10.1021/bi800786q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ford DA. Lipid oxidation by hypochlorous acid: chlorinated lipids in atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia. Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:835–852. doi: 10.2217/clp.10.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thukkani AK, Hsu FF, Crowley JR, Wysolmerski RB, Albert CJ, Ford DA. Reactive chlorinating species produced during neutrophil activation target tissue plasmalogens: production of the chemoattractant, 2-chlorohexadecanal. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3842–3849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thukkani AK, McHowat J, Hsu FF, Brennan ML, Hazen SL, Ford DA. Identification of alpha-chloro fatty aldehydes and unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholine molecular species in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 2003;108:3128–3133. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104564.01539.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thukkani AK, Martinson BD, Albert CJ, Vogler GA, Ford DA. Neutrophil-mediated accumulation of 2-ClHDA during myocardial infarction: 2-ClHDA-mediated myocardial injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2955–2964. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00834.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ullen A, Fauler G, Bernhart E, Nusshold C, Reicher H, Leis HJ, Malle E, Sattler W. Phloretin ameliorates 2-chlorohexadecanal-mediated brain microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1770–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marsche G, Heller R, Fauler G, Kovacevic A, Nuszkowski A, Graier W, Sattler W, Malle E. 2-chlorohexadecanal derived from hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein-associated plasmalogen is a natural inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide biosynthesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2302–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000148703.43429.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Messner MC, Albert CJ, Ford DA. 2-Chlorohexadecanal and 2-chlorohexadecanoic acid induce COX-2 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Lipids. 2008;43:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3189-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ullen A, Fauler G, Kofeler H, Waltl S, Nusshold C, Bernhart E, Reicher H, Leis HJ, Wintersperger A, Malle E, Sattler W. Mouse brain plasmalogens are targets for hypochlorous acid-mediated modification in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1655–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ullen A, Singewald E, Konya V, Fauler G, Reicher H, Nusshold C, Hammer A, Kratky D, Heinemann A, Holzer P, Malle E, et al. Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants induce blood-brain barrier dysfunction in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ullen A, Nusshold C, Glasnov T, Saf R, Cantillo D, Eibinger G, Reicher H, Fauler G, Bernhart E, Hallstrom S, Kogelnik N, et al. Covalent adduct formation between the plasmalogen-derived modification product 2-chlorohexadecanal and phloretin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Glanzer S, Zangger K. Visualizing unresolved scalar couplings by real-time j-upscaled NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5163–5169. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Castillo AM, Patiny L, Wist J. Fast and accurate algorithm for the simulation of NMR spectra of large spin systems. J Magn Reson. 2011;209:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Weksler BB, Subileau EA, Perriere N, Charneau P, Holloway K, Leveque M, Tricoire-Leignel H, Nicotra A, Bourdoulous S, Turowski P, Male DK, et al. Blood-brain barrier-specific properties of a human adult brain endothelial cell line. FASEB J. 2005;19:1872–1874. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3458fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nusshold C, Kollroser M, Kofeler H, Rechberger G, Reicher H, Ullen A, Bernhart E, Waltl S, Kratzer I, Hermetter A, Hackl H, et al. Hypochlorite modification of sphingomyelin generates chlorinated lipid species that induce apoptosis and proteome alterations in dopaminergic PC12 neurons in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1588–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wildsmith KR, Albert CJ, Anbukumar DS, Ford DA. Metabolism of myeloperoxidase-derived 2-chlorohexadecanal. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16849–16860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Duerr MA, Aurora R, Ford DA. Identification of glutathione adducts of alpha-chlorofatty aldehydes produced in activated neutrophils. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1014–1024. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M058636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wildsmith KR, Albert CJ, Hsu FF, Kao JL, Ford DA. Myeloperoxidase-derived 2-chlorohexadecanal forms Schiff bases with primary amines of ethanolamine glycerophospholipids and lysine. Chem Phys Lipids. 2006;139:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wilkie-Grantham RP, Magon NJ, Harwood DT, Kettle AJ, Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB. Myeloperoxidase-dependent lipid peroxidation promotes the oxidative modification of cytosolic proteins in phagocytic neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9896–9905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.613422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stemmer U, Ramprecht C, Zenzmaier E, Stojcic B, Rechberger G, Kollroser M, Hermetter A. Uptake and protein targeting of fluorescent oxidized phospholipids in cultured RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:706–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Codreanu SG, Zhang B, Sobecki SM, Billheimer DD, Liebler DC. Global analysis of protein damage by the lipid electrophile 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:670–680. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800070-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Andringa KK, Udoh US, Landar A, Bailey SM. Proteomic analysis of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) modified proteins in liver mitochondria from chronic ethanol-fed rats. Redox Biol. 2014;2C:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ullrich O, Grune T, Henke W, Esterbauer H, Siems WG. Identification of metabolic pathways of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal by mitochondria isolated from rat kidney cortex. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:84–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lin MH, Yen JH, Weng CY, Wang L, Ha CL, Wu MJ. Lipid peroxidation end product 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal triggers unfolded protein response and heme oxygenase-1 expression in PC12 cells: Roles of ROS and MAPK pathways. Toxicology. 2014;315:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Muller C, Bandemer J, Vindis C, Camare C, Mucher E, Gueraud F, Larroque-Cardoso P, Bernis C, Auge N, Salvayre R, Negre-Salvayre A. Protein disulfide isomerase modification and inhibition contribute to ER stress and apoptosis induced by oxidized low density lipoproteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:731–742. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wang WY, Albert CJ, Ford DA. Alpha-chlorofatty Acid accumulates in activated monocytes and causes apoptosis through reactive oxygen species production and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:526–532. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Moumtzi A, Trenker M, Flicker K, Zenzmaier E, Saf R, Hermetter A. Import and fate of fluorescent analogs of oxidized phospholipids in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:565–582. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600394-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gygi SP, Corthals GL, Zhang Y, Rochon Y, Aebersold R. Evaluation of two-dimensional gel electrophoresis-based proteome analysis technology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9390–9395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160270797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ziegler S, Pries V, Hedberg C, Waldmann H. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: finding the needle in the haystack. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:2744–2792. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Boulon S, Lam YW, Urcia R, Boisvert FM, Vandermoere F, Morrice NA, Swift S, Rothbauer U, Leonhardt H, Lamond A. Identifying specific protein interaction partners using quantitative mass spectrometry and bead proteomes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:223–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nakatsuji H, Nishimura N, Yamamura R, Kanayama HO, Sasaki T. Involvement of actinin-4 in the recruitment of JRAB/MICAL-L2 to cell-cell junctions and the formation of functional tight junctions. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3324–3335. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cristante E, McArthur S, Mauro C, Maggioli E, Romero IA, Wylezinska-Arridge M, Couraud PO, Lopez-Tremoleda J, Christian HC, Weksler BB, Malaspina A, et al. Identification of an essential endogenous regulator of blood-brain barrier integrity, and its pathological and therapeutic implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:832–841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209362110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee DB, Jamgotchian N, Allen SG, Kan FW, Hale IL. Annexin A2 heterotetramer: role in tight junction assembly. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F481–491. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00175.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Architecture of tight junctions and principles of molecular composition. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;36:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wang J, Milner R. Fibronectin promotes brain capillary endothelial cell survival and proliferation through alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 integrins via MAP kinase signalling. J Neurochem. 2006;96:148–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Huang Y, Shi H, Zhou H, Song X, Yuan S, Luo Y. The angiogenic function of nucleolin is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor and nonmuscle myosin. Blood. 2006;107:3564–3571. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Richarme G, Mihoub M, Dairou J, Bui LC, Leger T, Lamouri A. Parkinsonism-associated protein DJ-1/Park7 is a major protein deglycase that repairs methylglyoxal- and glyoxal-glycated cysteine, arginine, and lysine residues. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:1885–1897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cao J, Ying M, Xie N, Lin G, Dong R, Zhang J, Yan H, Yang X, He Q, Yang B. The oxidation states of DJ-1 dictate the cell fate in response to oxidative stress triggered by 4-hpr: autophagy or apoptosis? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:1443–1459. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Parnetti L, Castrioto A, Chiasserini D, Persichetti E, Tambasco N, El-Agnaf O, Calabresi P. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:131–140. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lin X, Cook TJ, Zabetian CP, Leverenz JB, Peskind ER, Hu SC, Cain KC, Pan C, Edgar JS, Goodlett DR, Racette BA, et al. DJ-1 isoforms in whole blood as potential biomarkers of Parkinson disease. Sci Rep. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/srep00954. 954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Thijssen VL, Griffioen AW. Galectin-1 and -9 in angiogenesis: a sweet couple. Glycobiology. 2014;24:915–920. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Brouwers O, Niessen PM, Miyata T, Ostergaard JA, Flyvbjerg A, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Sieber J, Mundel PH, Brownlee M, Janssen BJ, De Mey JG, et al. Glyoxalase-1 overexpression reduces endothelial dysfunction and attenuates early renal impairment in a rat model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2014;57:224–235. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Slomnicki LP, Lesniak W. S100A6 (calcyclin) deficiency induces senescence-like changes in cell cycle, morphology and functional characteristics of mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:576–584. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bao L, Odell AF, Stephen SL, Wheatcroft SB, Walker JH, Ponnambalam S. The S100A6 calcium-binding protein regulates endothelial cell-cycle progression and senescence. FEBS J. 2012;279:4576–4588. doi: 10.1111/febs.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Henriksen C, Kjaer-Sorensen K, Einholm AP, Madsen LB, Momeni J, Bendixen C, Oxvig C, Vilsen B, Larsen K. Molecular cloning and characterization of porcine Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase isoforms alpha1, alpha2, alpha3 and the ATP1A3 promoter. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]