Abstract

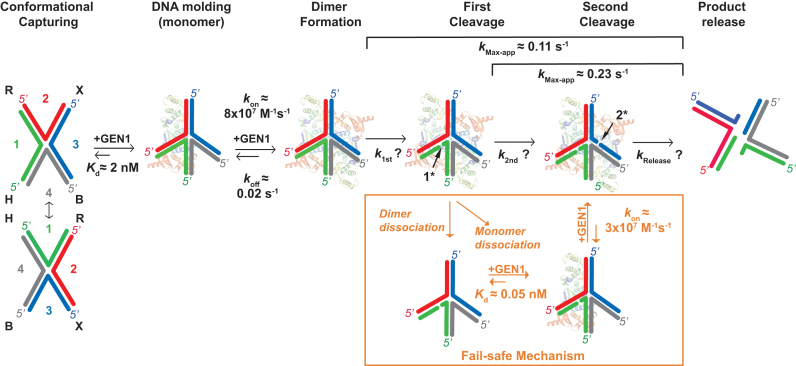

Human GEN1 is a cytosolic homologous recombination protein that resolves persisting four-way Holliday junctions (HJ) after the dissolution of the nuclear membrane. GEN1 dimerization has been suggested to play key role in the resolution of the HJ, but the kinetic details of its reaction remained elusive. Here, single-molecule FRET shows how human GEN1 binds the HJ and always ensures its resolution within the lifetime of the GEN1-HJ complex. GEN1 monomer generally follows the isomer bias of the HJ in its initial binding and subsequently distorts it for catalysis. GEN1 monomer remains tightly bound with no apparent dissociation until GEN1 dimer is formed and the HJ is fully resolved. Fast on- and slow off-rates of GEN1 dimer and its increased affinity to the singly-cleaved HJ enforce the forward reaction. Furthermore, GEN1 monomer binds singly-cleaved HJ tighter than intact HJ providing a fail-safe mechanism if GEN1 dimer or one of its monomers dissociates after the first cleavage. The tight binding of GEN1 monomer to intact- and singly-cleaved HJ empowers it as the last resort to process HJs that escape the primary mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

The Holliday junction (HJ) is a four-way branch point structure adjoining two DNA duplexes (1). These junctions are central intermediates in homologous recombination that repairs DNA double strand breaks arising from DNA damaging agents or stalled replication forks (2–4). Recombination occurs between two identical chromatids by strand invasion into a double helix, where one chromatid provides a template for the error-free repair of the broken DNA (5,6). This strand invasion generates a single HJ and when it captures the second complementary DNA end, it forms a double HJ (7,8). A variety of pathways resolve the HJs to allow the achievement of proper chromosomal segregation.

The HJ is a highly dynamic structure connecting four helices by strand exchange. In the presence of metal ions, the junction folds by pairwise coaxial stacking of the helices to form an X-structure (9,10). In this X-structure, two DNA strands run continuously while the other two exchange between the helical pairs (Figure 1A). Isomerization then takes place through the role-exchange between the continuous and the crossing strands (Figure 1A) (11,12). Genetic recombination is affected by the stacking conformer preference since it sets the orientation of the HJ resolution leading to either crossover or noncrossover products (13).

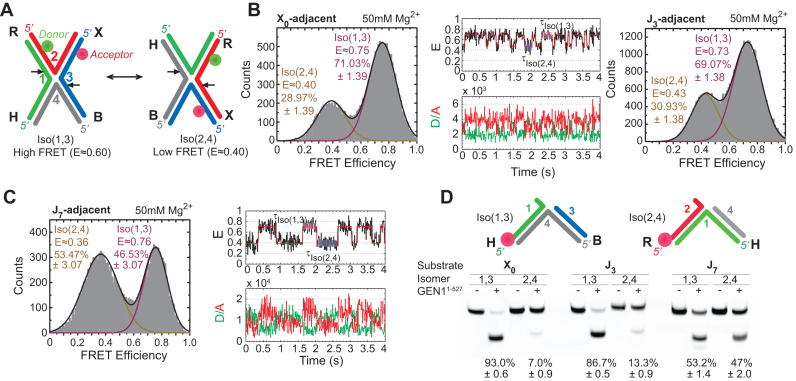

Figure 1.

Conformation capturing of the HJ by GEN1. (A) Schematic of isomerizing adjacent-label X-stacked HJ conformers. The strands are numbered while the arms are denoted by letters. The conformers are named after the two continuous strands and their incision sites are shown by arrows. The location of the donor (green) and acceptor (red) and change in FRET upon isomerization are indicated. (B) Left panel: FRET histogram of X0 at 50 mM Mg2+. Middle panel: FRET time trace (black) and idealized FRET trace (red) of X0 at 50 mM Mg2+. The fluorescence intensities of the donor (green) and the acceptor (red) are shown below. Right panel: FRET histogram of J3 at 50 mM Mg2+. (C) FRET histogram and time traces of J7 at 50 mM Mg2+. (D) Bulk cleavage of X0, J3 and J7 junctions. The uncertainties in panels B and C represent the standard deviations from two or more experiments. The error bars in the bulk cleavage assay (panel D) represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) from two experiments.

The primary pathway for HJ processing in human cells involves the BLM helicase-Topoisomerase IIIα-RMI1-RMI2 (BTR) complex (14–16). BTR is active throughout the cell cycle and dissolves double HJs by promoting their convergent migration to form hemicatenanes that can be cleaved by the topoisomerase (17–19). BTR favors the formation of noncrossover nick-duplex DNA products and is therefore essential for avoiding sister chromatid exchange, which may in turn lead to the loss of heterozygosity (17,20). The second pathway acts by resolving both double HJs and single HJs, which are incompatible substrates for BTR, by structure-selective endonucleases such as the MUS81-EME1-SLX1-SLX4-XPF-ERCC1 (SMX) (21–25) and GEN1 (26,27). These resolvases introduce coordinated nicks at the junction and produce both crossover and noncrossover nick-duplex DNA products. To avoid the formation of crossover products while ensuring the resolution of persisting single- and double-HJs, the resolvases are activated only at later stages in the cell cycle. MUS81-EME1 and SLX1-SLX4-XPF-ERCC1 form a complex at the prometaphase (24,25), while GEN1 is a cytosolic protein that gains access to DNA upon the breakdown of the nuclear envelope (28). MUS81- and GEN1-depleted cells enter mitosis with their sister chromatid bridges intact leading to a high level of chromosomal aberration and cell death (29–31). Resolvases therefore do not simply act as a backup mechanism for BTR, but rather play a critical role in chromosomal segregation (32). The crossover cleavage by resolvases may also play a role in the exchange of genetic material during meiosis.

GEN1 symmetrically incises the continuous strands and appears to follow the conformer bias of the stacked-X structure via a coordinated nick and counter-nick mechanism (Figure 1A) (33). Several lines of evidence indicate that GEN1 is a monomeric protein in solution and requires dimerization to cleave the HJ. Using supercoiled plasmids, it was suggested that monomeric GEN1 is unlikely to be functionally active on the HJ. The incision requires the coordination of two active sites contrary to a mechanism where a single nick takes place, followed by protein dissociation, reassociation, then counter nicking (33). The inactivity of GEN1 monomer on HJ is supported by the observation that GEN1 monomer binds HJs more tightly than its dimer and that excess HJ decreases the cleavage rate by sequestering the monomer from solution (34). Further evidence suggests that even with the decoupling of the two incisions, either by using an active subunit of the dimer associated with a catalytically inactive partner or a non-cleavable phosphorothioate cleavage site, the first incision still seems to require GEN1 dimerization (33).

GEN1 has been shown in vitro to cleave the DNA replication and repair 5′ flaps intermediary structures, forks and three-way junctions. Moreover, the rate of cleavage of the 5′ flap substrate is faster than that of the HJ (27,35). The basis for this indiscrimination and its biological relevance are largely unknown. Unlike the HJ case, for the 5′ flap substrate, the cleavage is not inhibited by increasing the substrate-to-enzyme ratio demonstrating that it only requires a single incision by GEN1 monomer (27). Therefore, it is likely that GEN1 monomer lacks selectivity and it only becomes highly selective upon dimerization at HJs.

The crystal structure of GEN1 from thermophilic fungus C. thermophilum (termed CtGEN1) (36) bound to a nicked duplex DNA product after the cleavage of the HJ provides a potential model as to how GEN1 dimer may act on the HJs. Although the functional unit corresponds to one monomer, protein-protein interactions in the crystal lattice generate a structure that appears to be related to a dimeric GEN1 bound to a HJ. The strands in the product DNA can be rejoined to generate an intact HJ without altering the position of the arms. Nevertheless, this would require the opening of the helical structure at the center of the junction. In this model, the X-stacked structure is remodeled upon GEN1 binding where the uncleaved strands become coaxially aligned, while the cleaved strands rotate towards each other on the major groove side to be both mutually perpendicular and with respect to the axis of the uncleaved strands. Additionally, the existence of GEN1 as a monomer in solution was attributed to the relatively small dimer interface that is composed of three helices and their associated loops. This dimer interface may coordinate the two incisions since it is in close proximity to a superfamily conserved helical arch structure. An unstructured region in this helical arch contains basic residues that are likely to play a role in catalysis. Similarly, in the human GEN1 structure, the helical arch is also largely unstructured (35). These results propose a protein ordering step that is influenced by DNA binding and dimer formation and may provide a mechanism that coordinates the two incisions in GEN1 dimer, reminiscent of that observed in other 5′-nucleases family members (FEN1 (37–41) and Exo1 (42,43)).

Previous biochemical characterizations highlighted the importance of dimer formation in coordinating the two incisions at the HJ (27,33,34). However, it remains unclear how GEN1 binds the HJ, coordinates the two incisions, and ensures its full resolution. Using smFRET, we simultaneously monitored human GEN1 binding and cleavage of the HJ, thus accessing the rates of the underlying processes leading to the resolution of the HJ. We showed that GEN1 monomer initially binds the HJ by following its isomerization preference (conformational capturing) and then actively distorts it into a different structure (induced fit). This is followed by dimer formation and incisions. GEN1 consistently succeeds in resolving the HJ within the lifetime of the GEN1-HJ complex, demonstrating a mechanism that always ensures forward steps after DNA binding. This is achieved through the tight binding of GEN1 monomer to the HJ, fast on- and slow off-rates for GEN1 dimer, and the increased affinity of the assembled GEN1 dimer at the first incision product. Furthermore, GEN1 monomer binds the singly-cleaved HJ 40-fold stronger. This in turn may provide a fail-safe mechanism in the unlikely event that GEN1 dimer, or one of its monomers, dissociates upon the first incision. These findings unravel how GEN1 can effectively act as the last resort to resolve any intact or singly-cleaved HJs that escape the primary pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

The active truncated form of carboxy-terminal His-tagged human GEN11–527 was purified after overexpression in E. coli (26). The constructed plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL strain (Novagen) for expression. The cells were incubated in LB media until they reached OD600 of 0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl‐β‐d‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 48 h at 16°C. The cells were then harvested by spinning down at 4°C and the cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 300 mM NaCl and 2 mM PMSF). The cells were lysed by a cell disruptor at 30 kPsi and spun down by ultracentrifugation. The supernatant was filtered and passed through a Ni-NTA column (HisTrap FF, GE Healthcare) using Buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 300 mM NaCl) and eluted with linear gradient of Buffer A and 500 mM Imidazole at around 100 mM Imidazole. After reducing the salt concentration to 100 mM by dilution, the collected protein fractions were passed through a HiTrap Heparin column (GE Healthcare) using Buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl) where the protein was eluted with a gradient of Buffer B and 1 M NaCl at around 360 mM NaCl. The collected fractions were diluted to lower salt concentration and loaded onto a MonoS (4.6/100) (GE Healthcare) ion exchange column using Buffer B and eluted by a gradient of Buffer B and 1 M NaCl at 300 mM NaCl. The collected fractions were dialyzed against storage buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol), flash frozen, and then stored at −80°C.

DNA substrate preparation

The DNA oligonucleotides used in this study were purchased from either Integrated DNA technologies (IDT) or Sigma-Aldrich (Supplementary Materials Table SI). The fluorescently labeled oligos were HPLC purified, while oligos of 60 bp length or higher were PAGE purified when possible. The HJs were annealed by equimolar ratio except for nicked-HJ where the shorter strands were added in 6-fold excess. The specific oligo strands were annealed in buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) by heating at 95°C for 5 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature. The substrates were then purified by non-denaturing PAGE and eluted using the crush and soak method in the annealing buffer, by overnight extraction at 4°C, followed by ethanol precipitation and were then aliquoted and stored at −20°C. The purified substrates were run on a native gel to verify that all four arms are annealed properly in the HJ.

Single molecule FRET experiments

smFRET experiments were performed in a microfluidic flow cell. The coverslip surface was passivated and functionalized with biotin-PEG and PEG (1:100), then incubated with 0.03 mg/ml solution of filtered NeutrAvidin (NA) dissolved in PBS buffer. Excess NA was washed followed by immobilization of biotinylated substrate. The fluorophores stability was improved using protocatechuic acid/protocatechuate-3,4-dioxygenase oxygen scavenging system and Trolox. The imaging buffer in smFRET cleavage experiments is composed of 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% BSA and 5% (v/v) glycerol. The buffer used for smFRET binding experiments had the same composition except for substituting MgCl2 with 2 mM CaCl2. Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 647 were excited with 532 and 640 nm lasers, respectively, in objective-based TIRF mode as described in detail elsewhere (44). The emissions of the donor and the acceptor were split inside a Dualview. The images of the surface-immobilized DNA were recorded using single-color green (532 nm) excitation and alternating green (532 nm) and red (640 nm) excitations. The image acquisition was synchronized to the laser excitation through triggering the acousto-optic tunable filter by an EMCCD camera to prevent photobleaching of the sample when images were not being acquired. The acquired movies of the immobilized molecules were constituted of 400 frames, each of an average duration of 80 ms and contain 200–300 linked molecules in both the donor and acceptor channels. The histogram was constructed by binning the distribution of the states in each molecule against FRET efficiency using 100 bins (45). An experiment refers to an independent replica performed with a new set of reagents. Time-lapse single-color smFRET cleavage was used to extend the acquisition time. This was accomplished by using 125 excitation cycles over the period of 78 seconds using 60 milliseconds exposure and 624-ms cycle duration. The identification of FRET states and inference of idealized trajectories from smFRET time traces were performed using the vbFRET package implemented in Matlab (46).

Bulk cleavage assays

Isomer preference of GEN1

2 nM Cy5-labeled substrate (X0, J3 or J7) (Supplementary Materials Table SII) along with 10 nM GEN11–527 was incubated in reaction buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 5% (v/v) glycerol) for 15 min at 37°C in a final volume of 15 μl. The reaction was halted by adding 15 μl of STOP buffer (25 mM EDTA in deionized Formamide). The fluorescently labeled products were then denatured to single strands at 95°C for 5 min and further resolved by loading onto 20% 7 M urea acrylamide–bisacrylamide 19:1 gels. The gels were imaged by a laser scanner (Typhoon Trio, GE Healthcare) at 635 nm and the bands were quantified by GelQuantNET (BiochemLab Solutions).

Kinetic parameters determination

Equal volumes of 2 nM Cy5-labeled X0 or nk-X0 (Supplementary Materials Table SII) and the respective amount of GEN11–527 were mixed under reaction buffer conditions (40 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 5% (v/v) glycerol) at 22°C in a final volume of 200 μl. Aliquots were taken and immediately quenched in quenching buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM EDTA, 2.5% SDS and 10 mg/ml proteinase K) after 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45 seconds as well as after 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 min of incubation. Subsequent incubation at 37°C for 45 min was performed to ensure complete deproteination. The aliquots were resolved under native PAGE conditions (10% TBE gel, Invitrogen). The gels were imaged by a laser scanner (Typhoon Trio, GE Healthcare) at 635 nm and the bands were quantified by GelQuantNET (BiochemLab Solutions). The percentage of cleaved substrate was calculated as a fraction of the total fluorescence in the respective lane. The relative cleavage versus time curves were fit to a single exponential function to obtain the pseudo-first-order reaction constant (kapp-bulk). Further, to obtain kinetic parameters, the kapp-bulk (s−1) versus GEN1 (nM) rate curves were plotted and fit to the sigmoidal form:

Y = kSTO · [GEN1]n/((k1/2-dimer-bulk)n + [GEN1]n), where kSTO is the maximum observed reaction rate; [GEN1] is the concentration of GEN1; n is the Hill coefficient, k1/2-dimer-bulk is the concentration of GEN1 at which half-maximum catalytic rate is achieved, analogous to the KM (Michaelis–Menten constant) of first-order enzyme systems.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) of GEN1-HJ complexes were carried out at different GEN1 concentrations in the pico and nano-molar ranges. In a total volume of 50 μl, GEN1 was incubated with Cy5-labeled DNA (50 pM or 2 nM) at room temperature for 30 minutes in binding buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 5% (v/v) glycerol), and 5 ng/μl poly-dI-dC. Complexes were separated via 6% native PAGE (Invitrogen) in 1× TBE buffer at room temperature and imaged using the Typhoon Trio Imager (GE Healthcare) at 635 nm. The bands were quantified by GelQuantNET (BiochemLab Solutions). The bound substrate percentage was calculated from its contribution to the total fluorescence of the respective lane. The apparent binding constants Kd-monomer-app-EMSA and Kd-dimer-app-EMSA were calculated using the equation of the form Y = Max · [GEN1]n/(Kd-app-EMSAn + [GEN1]n), where Max is the concentration at which the respective species reached its maximum (monomer or dimer), n is the Hill coefficient and Kd-app-EMSA is the apparent binding constant of the respective species, denoting the concentration of GEN1 at which half-maximum of monomer or dimer is present.

RESULTS

Conformational capturing followed by active distortion of the HJ by GEN1

The stacking conformer preference of the HJ influences the outcome of genetic recombination by setting the orientation of the resolution by the HJ resolvases (13). We started therefore by investigating the DNA conformational requirement for the binding of GEN1 to the HJ.

HJs have been extensively investigated by FRET using ensemble and single-molecule methods (10,12,47,48), and as confirmed by X-ray crystallography, they exist in an anti-parallel, noncrossing X-stacked configuration (49). Isomerization occurs through role-exchange between the continuous and the crossing strands (Figure 1A). The preference of the arms to a particular configuration depends on the core sequence at the strand-exchange point and probably to a lesser extent on the second row of the neighboring nucleotides around the junction core (50). In addition, the ionic environment influences the isomerization rate without altering the isomer equilibrium; i.e., divalent ions as Mg2+ slow down the isomerization by masking the repulsion between the phosphate groups on the DNA backbone, while monovalent ions as Na+ increase the isomerization rates (12,47). As depicted in the schematic in Figure 1A, the HJ is formed of four arms (R, X, B, and H) comprised of strands: 1, 2, 3 and 4 color-coded in green, red, blue and gray, respectively. We primarily used adjacent-labeling, where the donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Alexa Fluor 647) are positioned at the two adjacent arms, R (strand 2) and X (strand 3), respectively (Figure 1A). We will refer to each of the stacked-X isomers by the two continuous strands; i.e., Iso(1,3) or Iso(2,4). In the high FRET Iso(1,3), strands 1 and 3 are continuous, while strands 2 and 4 are crossing and vice versa in the low FRET Iso(2,4) (Figure 1A). We studied the HJ resolution by GEN1 with three static junctions X0, J3 and J7, which have fixed strand-exchange points and discrete isomer preferences. We determined the conformational preference of these junctions under significantly reduced isomerization rate conditions using 50 mM MgCl2 (47). The FRET histograms of X0 and J3 show two peaks which correspond to the interchanging more abundant Iso(1,3) (E ≈ 0.75) and less abundant Iso(2,4) (E ≈ 0.40) (Figure 1B). A representative FRET time trace of a single X0 junction shows the transitions between high and low FRET isomers (Figure 1B). The isomerization rates  and

and  (Supplementary Figure S1A) are consistent with those reported previously (12). The X-stacking in J7, on the other hand, shows no preference to either isomer with nearly equal populations of Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) as shown in the FRET histogram and the FRET time trace (Figure 1C).

(Supplementary Figure S1A) are consistent with those reported previously (12). The X-stacking in J7, on the other hand, shows no preference to either isomer with nearly equal populations of Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) as shown in the FRET histogram and the FRET time trace (Figure 1C).

To study the conformer bias of GEN1 to Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) in bulk, we constructed fluorescently-labeled junctions in either strand 1 or strand 2, respectively. The total cleavage yield by GEN1 was similar between 0.5 and 2 mM Mg2+ but decreased by 2-fold at 10 mM Mg2+. However, this trend was not observed for the 5′ flap substrate (Supplementary Figure S1B), which forms a stable structure (39) and is cleaved by GEN1 monomer (27). The bulk cleavage of X0 and J3 under steady state showed major bands for the cleavage of Iso(1,3), while J7 displayed nearly equal product bands of the two isomers (Figure 1D). Moreover, we investigated whether changing the isomerization rate of the HJ by varying Mg2+ concentration would influence the conformer bias of GEN1. Kim et al. demonstrated that the isomerization rates of the HJ decrease by 30-fold upon increasing Mg2+ concentration from 0.5 to 8 mM (51). The percentages of isomer cleavage of X0, J3 and J7 were nearly unchanged at the tested 0.5, 2 and 10 mM Mg2+ concentrations (Supplementary Figure S1C). GEN1 generally follows the conformational bias of the HJ but since the percentages of isomer resolution in bulk slightly differ from the isomer bias of the HJ in smFRET, we conclude that there are other factors that may influence the initial binding such as preference towards particular core sequences as shown previously (52). The sequence of the incision sites are not equivalent in both X0 and J3, thus the preference towards incising arms 1 and 3 in these two junctions beyond the isomer distribution of the free junction may be attributed to GEN1 tendency to incise particular sequences. On the other hand, in J7 where the incision sites are identical in the four arms, the isomer resolution coincides with the isomer bias of the free junction determined by smFRET. Collectively, these findings suggest that the initial binding of GEN1 to the HJ (27) is generally mediated by conformational capturing, where the stacking conformer preference and to a lesser extent sequence dependence set the orientation of the HJ resolution by GEN1.

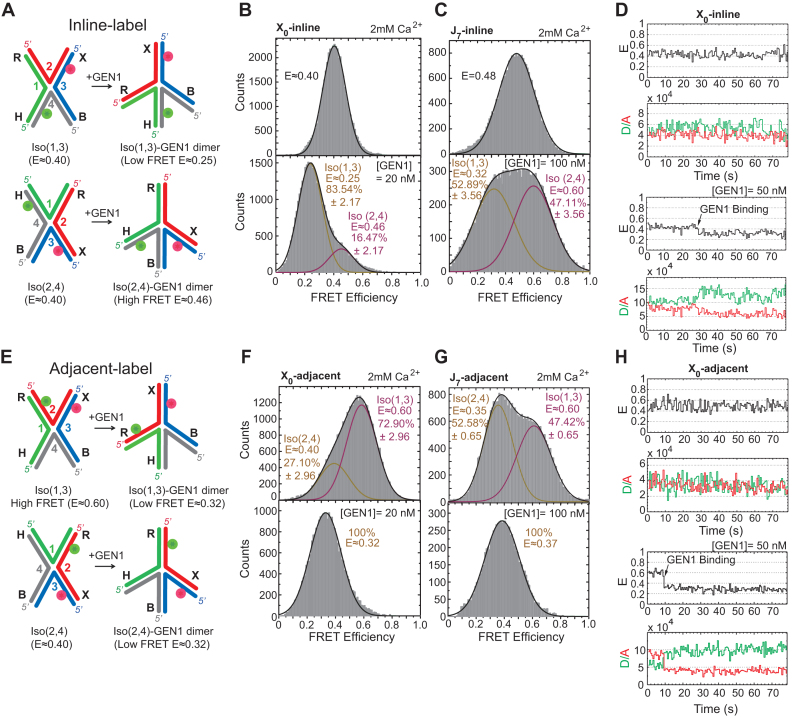

We next show that GEN1 actively distorts the captured conformer in agreement with the recent crystal model (36). According to the model, the binding of GEN1 to Iso(1,3) causes the uncleaved arms X (strand 2) and H (strand 4) to become coaxial, while the cleaved arms R (strand 1) and B (strand 3) rotate towards each other to be both mutually perpendicular and with respect to the axis of the uncleaved arms as illustrated in Figure 2A. Similarly, the binding of GEN1 to Iso(2,4) results in the uncleaved arms R (strand 1) and B (strand 3) to assume a coaxial orientation, while the cleaved arms X (strand 2) and H (strand 4) become perpendicular to each other and to the axis of the uncleaved arms (Figure 2A). We tested this prediction for the GEN1-HJ model using an inline-label scheme of the HJ by positioning the donor on arm H (strand 4) and the acceptor on arm X (strand 3) (Figure 2A). The FRET in this scheme is insensitive to the isomerization of the HJ, since the distance between the donor and the acceptor in both isomers remains the same (Figure 2A) (53). Therefore, any change in FRET corresponds to the GEN1-induced DNA structural distortion. The smFRET binding assay was performed in the presence of the catalytically inactive Ca2+ using 2 mM concentration to prevent the cleavage of the HJ. If the crystal structure model is correct, then the formation of GEN1-Iso(1,3) complex will increase the distance between the fluorophores to form a structure with a lower FRET than Iso(1,3) (Figure 2A). In contrast, in GEN1-Iso(2,4) complex, the distance between the two fluorophores will decrease to result in a structure with higher FRET than either isomer (Figure 2A). The FRET histogram of the inline-label X0 junction is composed of a single peak centered at (E ≈ 0.40) (Figure 2B). The histogram at saturating concentration of GEN1 is formed of a major peak centered at low FRET (E ≈ 0.25) and a minor high FRET peak (E ≈ 0.46) corresponding to the GEN1-Iso(1,3) and -Iso(2,4) complexes, respectively (Figure 2B). The FRET histogram of the inline-label J7 junction also shows a single peak (E ≈ 0.48) (Figure 2C). At saturating GEN1 concentration, the FRET histogram becomes divided into two nearly equally abundant low FRET (E ≈ 0.32) and high FRET (E ≈ 0.60) peaks corresponding to GEN1 complexes with Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4), respectively (Figure 2C). Since the distributions of the respective GEN1-bound isomers in the FRET histograms of the inline-label X0 and J7 are in good agreement with the cleavage ratios observed in bulk (cf. Figure 1D), we concluded that these bound complexes are those poised for cleavage. The FRET time trace of the inline-label X0 junction shows a single low FRET state upon GEN1 distortion of the HJ that persists for the entire acquisition duration of the experiment demonstrating a highly stable GEN1-HJ complex (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Active distortion of the HJ by GEN1 (A) Inline-label schematic of the HJ structural distortion by GEN1 based on the proposed model (36). (B) FRET histogram of inline-label X0 showing a single peak (E ≈ 0.40). At saturating GEN1 concentration, the major low FRET peak (E ≈ 0.25) is attributed to GEN1-Iso(1,3) while the minor high FRET peak (E ≈ 0.46) results from GEN1-Iso(2,4). (C) FRET histogram of J7 showing a single peak (E ≈ 0.48). GEN1 binding to Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) yields two nearly equal populations of low and high FRET isomers, respectively. (D) Upper panel: FRET time trace of inline-label X0. Lower panel: GEN1 is flown in Ca2+ buffer to detect the onset of binding. A stable complex persists throughout the acquisition time. (E) GEN1 binding to adjacent-label Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) forms a low FRET structure (E ≈ 0.32). (F) FRET histogram of X0 exhibits a major high FRET peak (E ≈ 0.60) corresponding to Iso(1,3) and a lower FRET peak (E ≈ 0.40) for Iso(2,4). At saturating GEN1 concentration, the whole histogram is transformed into a single low FRET peak. (G) FRET histogram of J7 exhibits two nearly equal populations at high and low FRET corresponding to Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4), respectively. Binding of GEN1 forms a low FRET structure corresponding to a single peak (E ≈ 0.37). (H) Upper panel: FRET time trace of adjacent-label X0. Lower panel: GEN1 binding forms a stable low FRET state (E ≈ 0.32). The uncertainties in panels B, C, F, G represent the standard deviations from two or more experiments.

The GEN1-HJ model can also be tested using the adjacent-label scheme. The model predicts that upon GEN1 binding, the distance between the donor and the acceptor would be similar in both Iso(1,3) and Iso(2,4) (Figure 2E). Within our temporal resolution, the merging of the two isomers in X0 and J7 FRET histograms (Figure 2F, G; respectively) is caused by the averaging due to the higher transition rates at low divalent ion concentration. At saturating GEN1 concentration, only a single low FRET peak corresponding to GEN1 binding to either isomer is seen in the FRET histograms of X0 and J7 (Figure 2F and G), respectively. The FRET time trace (Figure 2H) shows low amplitude transitions between the two isomers in the presence of Ca2+ reflected in the reduced separation between the peaks of the two isomers in the FRET histogram (cf. Figure 1B). Upon GEN1 binding to the HJ, a stable low FRET complex is formed that persists for the entire acquisition duration of the experiment (Figure 2H), similar to that observed with the inline-label.

In conclusion, the combination of smFRET binding assay and bulk cleavage assays suggest that GEN1 generally follows the isomer bias of the HJ in its initial binding (conformational selection) with slight deviation that may be caused by other factors such as sequence preference of GEN152. Subsequently, GEN1 actively molds the HJ to a structure poised for catalysis (induced fit) in accordance with the model proposed by Liu et al. (36), and forms a stable complex with no apparent dissociation.

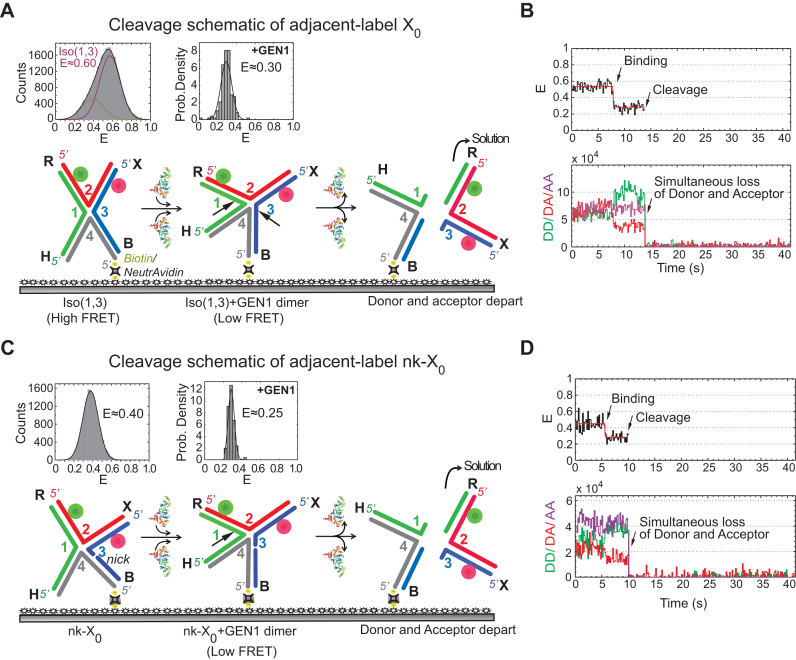

Real-time observation of HJ resolution by GEN1

We next replaced Ca2+ with Mg2+ to simultaneously monitor the HJ distortion and the HJ resolution by GEN1 at the single-molecule level. Since in smFRET, we can only detect the product release that follows the second cleavage event thus the term ‘cleavage’ in this context refers to the resolution of the HJ. The schematic in Figure 3A depicts the resolution of the highly abundant adjacent-label Iso(1,3) of X0 immobilized on the glass surface via biotin/NeutrAvidin linkage. Upon the introduction of the enzyme into the flow-cell, GEN1 binds and distorts X0 followed by incision of strands 1 and 3. The outcome is one unlabeled nicked duplex anchored to the surface and a second nicked duplex carrying both fluorophores which goes into solution resulting in the disappearance of both donor and acceptor signals. The FRET histogram of X0 at 2 mM Mg2+ is shown above the schematic of Iso(1,3). The probability distribution of the FRET efficiency of the dwell-time before cleavage ( ) is centered at E ≈ 0.30 (Figure 3A), similar to that in the binding assay (cf. Figure 2F). The resolution of the HJ was recorded by ALternating EXcitation (ALEX) of the donor and the acceptor to independently monitor both fluorophores. The incision of strands 1 and 3 results in the simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor following the low FRET state (E ≈ 0.30) that defines the GEN1 distortion of the HJ (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S2A). The direct excitation of the acceptor in the ALEX scheme also confirms the loss of the acceptor signal as a result of resolution (Figure 3B). To demonstrate that the simultaneous disappearance of the donor and the acceptor signals resulted from the resolution of the HJ by GEN1, we categorized the events according to the order of disappearance of the fluorophores in the binding (Ca2+) and the cleavage (Mg2+) experiments within a fixed time window that coincided with the entry of GEN1 and few tens of seconds onwards (Supplementary Figure S2C). The simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor after a stable low FRET state was exclusively observed in the cleavage experiment. Furthermore, under the same GEN1 concentration, the average

) is centered at E ≈ 0.30 (Figure 3A), similar to that in the binding assay (cf. Figure 2F). The resolution of the HJ was recorded by ALternating EXcitation (ALEX) of the donor and the acceptor to independently monitor both fluorophores. The incision of strands 1 and 3 results in the simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor following the low FRET state (E ≈ 0.30) that defines the GEN1 distortion of the HJ (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S2A). The direct excitation of the acceptor in the ALEX scheme also confirms the loss of the acceptor signal as a result of resolution (Figure 3B). To demonstrate that the simultaneous disappearance of the donor and the acceptor signals resulted from the resolution of the HJ by GEN1, we categorized the events according to the order of disappearance of the fluorophores in the binding (Ca2+) and the cleavage (Mg2+) experiments within a fixed time window that coincided with the entry of GEN1 and few tens of seconds onwards (Supplementary Figure S2C). The simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor after a stable low FRET state was exclusively observed in the cleavage experiment. Furthermore, under the same GEN1 concentration, the average  measurements at different flow rates were very similar indicating that the cleavage was not influenced by our choice of the flow rate (Supplementary Figure S2D).

measurements at different flow rates were very similar indicating that the cleavage was not influenced by our choice of the flow rate (Supplementary Figure S2D).

Figure 3.

Real-time resolution of the HJ resolution by GEN1 (A) Schematic of the adjacent-label X0 Iso(1,3) attached to the functionalized glass surface by the 5′ end of strand 4 via biotin/NeutrAvidin linkage. The FRET histogram of X0 at 2 mM Mg2+ is shown above the schematic. The probability density histogram of the FRET state from which cleavage occurs has the same FRET (E ≈ 0.30) as that observed in the binding experiment (Figure 2F). The dissociation of GEN1 after the two incisions results in two DNA duplex products: one harboring both the donor and acceptor that goes into solution and another unlabeled duplex that remains attached to the surface. (B) FRet alEX time trace (black) at 2 mM Mg2+ of the cleavage of Iso(1,3). The onset of GEN1 binding forms a stable low FRET state until the FRET signal is abruptly lost due to cleavage. Correspondingly, the increase in the donor and the decrease of acceptor fluorescence intensities upon GEN1 binding is followed by the simultaneous disappearance of the fluorescence from both dyes upon cleavage. The direct excitation of the acceptor (purple) confirms its loss. (C) Schematic of the adjacent-label nicked junction (nk-X0). The FRET histogram exhibits a single peak for a relaxed non-isomerizing structure. The binding of GEN1 prior to cleavage distorts the junction, as shown by the probability density histogram centered at E ≈ 0.25. The resolution occurs by cleaving strand 1 as indicated by the arrow, thus releasing the DNA duplex holding both fluorophores into solution. (D) FRet alEX time trace shows a stable low FRET state upon GEN1 binding which is concluded by the abrupt loss of the FRET signal. The donor and the acceptor signals from both FRET and direct excitation are lost upon resolution.

We next decoupled the two incision events using a nicked-X0 junction (nk-X0) at one cleavage site. The nick relieves the topological constraints resulting in a relaxed non-isomerizing structure, where the two stacked helices lie at a mutual angle of ≈ 90° and the electrostatic repulsion is reduced (Figure 3C) (54). The FRET histogram of the adjacent-label nk-X0 junction shows a single peak centered at E ≈ 0.40 in contrast to the isomerizing X0 junction (Figure 3Ccf. Figure 3A). Upon binding and distortion by GEN1, nk-X0 assumes a structure similar to that of the GEN1-Iso(1,3) complex, as indicated by the similarity in FRET efficiencies of the states before resolution (E ≈ 0.25 for nk-X0 and 0.30 for X0) (Figure 3Ccf. Figure 3A). The resolution of nk-X0 results in the DNA duplex harboring both the donor and the acceptor going into solution (Figure 3C). Thus, the FRET time trace displays a low FRET state (E ≈ 0.25) upon binding of GEN1 followed by the resolution of the junction demonstrated by the simultaneous loss of the donor and the acceptor (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S2B). The analysis of the photobleaching events in the binding and the cleavage experiments of nk-X0 confirms that the simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor after a stable low FRET state was exclusively observed in the cleavage experiment (Supplementary Figure S2E). These results do not support a scenario where GEN1 monomer binds the HJ, nicks it then dissociates, followed by a second monomer binding then performing the second cleavage. If this scenario were to hold, then a nicked HJ with a different FRET (E ≈ 0.40) would be created. However, since the FRET efficiencies of the bound intact junction and the bound nicked junction are similar, we cannot exclude the possibility that a monomer binds, nicks, and remains bound awaiting dimer formation. The change in FRET due to the binding of GEN1 to the HJ followed by the simultaneous departure of the donor and the acceptor represents a cleavage event within the lifetime of the GEN1-HJ complex. This demonstrates a remarkable ability of GEN1 to always resolve the HJ without a missed opportunity.

GEN1 monomer binds tightly to the junction followed by dimer formation

A previous study demonstrated that GEN1 initially binds the HJ as a monomer (34). Since we always observed the resolution within the lifetime of the GEN1-HJ complex, we propose that GEN1 monomer distorts the HJ and remains firmly bound until a dimer is formed and full resolution of the HJ takes place. Here, we provide evidence to support this hypothesis by showing that  distribution is dependent on GEN1 concentration. Hence, we carried out the smFRET cleavage at different GEN1 concentrations using time-lapse single-color excitation to minimize photobleaching over the acquisition time of ≈ 1.3 min. A representative FRET time trace of the uncleaved X0 junction acquired by this method is shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2F. These uncleaved particles with stable low FRET state resulting from the binding and the distortion of GEN1 monomer to the HJ were observed in a significant number of traces at low GEN1 concentrations and their number decreased upon increasing GEN1 concentration. On the other hand, the cleaved particles, where dimer was eventually formed, exhibited low FRET state (E ≈ 0.30) for a several-second long dwell time

distribution is dependent on GEN1 concentration. Hence, we carried out the smFRET cleavage at different GEN1 concentrations using time-lapse single-color excitation to minimize photobleaching over the acquisition time of ≈ 1.3 min. A representative FRET time trace of the uncleaved X0 junction acquired by this method is shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2F. These uncleaved particles with stable low FRET state resulting from the binding and the distortion of GEN1 monomer to the HJ were observed in a significant number of traces at low GEN1 concentrations and their number decreased upon increasing GEN1 concentration. On the other hand, the cleaved particles, where dimer was eventually formed, exhibited low FRET state (E ≈ 0.30) for a several-second long dwell time ) prior to the signal loss (Figure S4B). Upon resolution, both the donor and the acceptor fluorescence intensities disappear as well as the signal from the direct excitation of the acceptor (Figure 4B). The FRET efficiency of the state before cleavage was similar between the bound-uncleaved (Supplementary Figure S2G) and cleaved particles (Figure 3A) indicating that binding of GEN1 monomer is sufficient to distort the HJ. The strong binding of GEN1 monomer observed at all concentrations always ensures that the forward reaction to form a dimer is more favorable than the dissociation of GEN1 monomer from the HJ. The apparent dissociation constant of GEN1 monomer (Kd-monomer-app) for X0 determined from the binding isotherm in the presence of Ca2+ was 1.92 ± 0.31 nM (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S3A).

) prior to the signal loss (Figure S4B). Upon resolution, both the donor and the acceptor fluorescence intensities disappear as well as the signal from the direct excitation of the acceptor (Figure 4B). The FRET efficiency of the state before cleavage was similar between the bound-uncleaved (Supplementary Figure S2G) and cleaved particles (Figure 3A) indicating that binding of GEN1 monomer is sufficient to distort the HJ. The strong binding of GEN1 monomer observed at all concentrations always ensures that the forward reaction to form a dimer is more favorable than the dissociation of GEN1 monomer from the HJ. The apparent dissociation constant of GEN1 monomer (Kd-monomer-app) for X0 determined from the binding isotherm in the presence of Ca2+ was 1.92 ± 0.31 nM (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S3A).

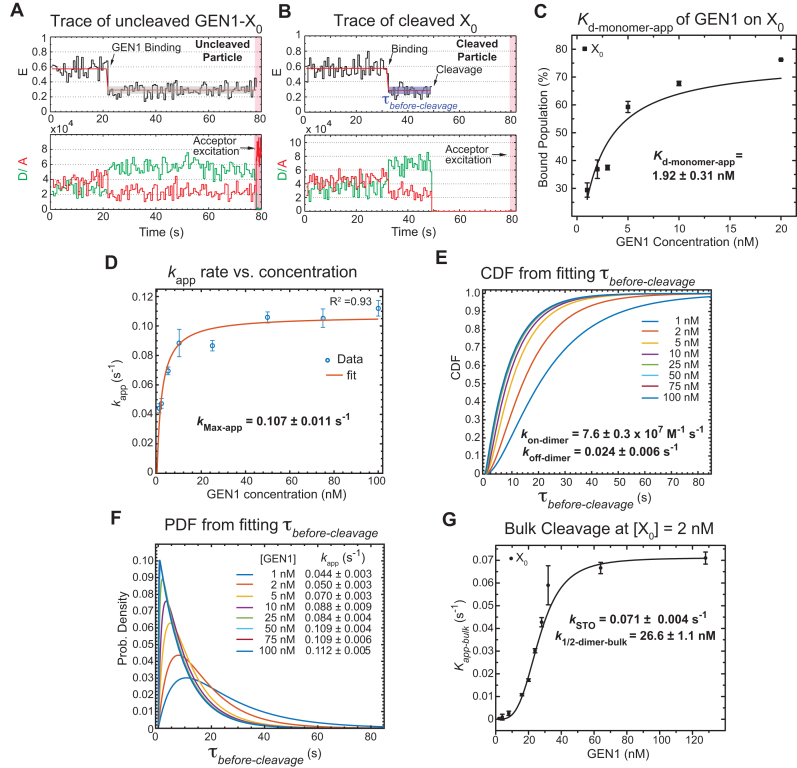

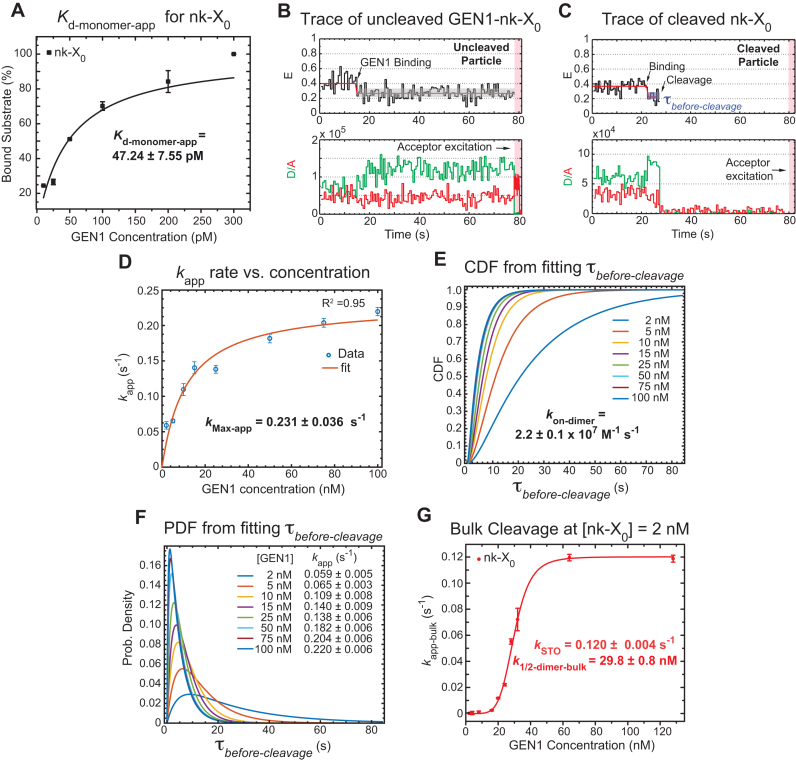

Figure 4.

GEN1 monomer binds tightly to the HJ followed by dimer formation (A) FRET time trace of bound but uncleaved adjacent-label X0 in Mg2+. Donor excitation for ≈ 1.3 min was performed, followed by direct acceptor excitation for 4 s (shaded red region). (B) FRET time trace of bound and cleaved X0. Subsequent acceptor excitation (shaded red region) shows the absence of the acceptor. Dwell times of the low FRET state ( ) at the respective GEN1 concentration were obtained from two or more experiments and used to obtain average rates (kapp). (C) The binding isotherm is constructed by titrating GEN1 under Ca2+ and determining the percentage of bound HJ from the FRET histograms (Supplementary Figure S3A). The error bars are as described in Figure 1 and 2. The dissociation constant (Kd-monomer-app) is determined from a hyperbolic fit of the plot. (D) kapp versus GEN1 concentration plot is fitted to a hyperbolic function to determine the apparent catalytic rate (kMax-app). (E) The Cumulative Density Function (CDF) plot is obtained by fitting the

) at the respective GEN1 concentration were obtained from two or more experiments and used to obtain average rates (kapp). (C) The binding isotherm is constructed by titrating GEN1 under Ca2+ and determining the percentage of bound HJ from the FRET histograms (Supplementary Figure S3A). The error bars are as described in Figure 1 and 2. The dissociation constant (Kd-monomer-app) is determined from a hyperbolic fit of the plot. (D) kapp versus GEN1 concentration plot is fitted to a hyperbolic function to determine the apparent catalytic rate (kMax-app). (E) The Cumulative Density Function (CDF) plot is obtained by fitting the  distribution at the respective GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential model (Supplementary Material, Figure S3B). The association (kon-dimer) and dissociation (koff-dimer) rates for dimer formation are determined from the deconvolution. (F) The Probability Density Function (PDF) plot of the

distribution at the respective GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential model (Supplementary Material, Figure S3B). The association (kon-dimer) and dissociation (koff-dimer) rates for dimer formation are determined from the deconvolution. (F) The Probability Density Function (PDF) plot of the  distribution illustrates its dependence on GEN1 concentration. The listed kapp rates are determined from the inverse of the mean

distribution illustrates its dependence on GEN1 concentration. The listed kapp rates are determined from the inverse of the mean  at the respective GEN1 concentration. The errors represent SEM of kapp. (G) The X0 apparent rate (kapp-bulk) versus GEN1 concentration plot from bulk cleavage is fit to a sigmoidal function yielding values of half-maximum activity (k1/2-dimer-bulk) and single turnover (kSTO). Error bars represent the SEM from two experiments. The concentration for half-maximum activity indifferent of substrate inhibition (k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA) was determined by the first-order total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) (Supplementary Figure S5E).

at the respective GEN1 concentration. The errors represent SEM of kapp. (G) The X0 apparent rate (kapp-bulk) versus GEN1 concentration plot from bulk cleavage is fit to a sigmoidal function yielding values of half-maximum activity (k1/2-dimer-bulk) and single turnover (kSTO). Error bars represent the SEM from two experiments. The concentration for half-maximum activity indifferent of substrate inhibition (k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA) was determined by the first-order total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) (Supplementary Figure S5E).

The processes involved under  start from the distortion of the HJ by GEN1 monomer and extend to include the sequential steps of dimer formation, followed by active-site formation/rearrangement in the transition state complex, the first incision then occurs within the lifetime of the dimer producing the nicked complex, and conclude by the second incision and product release. Since we cannot rule out the possibility that GEN1 remained bound to the nicked-DNA duplex product after completing the two incisions, we termed the rate measured from the single-molecule cleavage assays as an apparent rate of the HJ resolution (kapp), which is the inverse of the mean of

start from the distortion of the HJ by GEN1 monomer and extend to include the sequential steps of dimer formation, followed by active-site formation/rearrangement in the transition state complex, the first incision then occurs within the lifetime of the dimer producing the nicked complex, and conclude by the second incision and product release. Since we cannot rule out the possibility that GEN1 remained bound to the nicked-DNA duplex product after completing the two incisions, we termed the rate measured from the single-molecule cleavage assays as an apparent rate of the HJ resolution (kapp), which is the inverse of the mean of  at the respective GEN1 concentration. The plot of kapp versus GEN1 concentration was fitted to a hyperbolic function to determine the apparent catalysis rate constant kMax-app (0.107 ± 0.011 s−1) (Figure 4D). The concentration at which the half-maximum cleavage rate is achieved (k1/2-dimer) that is analogous to KM from classical enzyme kinetics, cannot be derived from this fit, since the single-molecule cleavage assay only accounts for the cleaved particles.

at the respective GEN1 concentration. The plot of kapp versus GEN1 concentration was fitted to a hyperbolic function to determine the apparent catalysis rate constant kMax-app (0.107 ± 0.011 s−1) (Figure 4D). The concentration at which the half-maximum cleavage rate is achieved (k1/2-dimer) that is analogous to KM from classical enzyme kinetics, cannot be derived from this fit, since the single-molecule cleavage assay only accounts for the cleaved particles.

To deconvolute the rates of the underlying processes, we fitted the cumulative density function (CDF) of the  distribution at each GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential function (Supplementary Material) using kMax-app determined from the hyperbolic fit (Figure 4E, Supplementary Figure S3B). The deconvolution yields the association and dissociation rates for the dimer, kon-dimer and koff-dimer, respectively. The

distribution at each GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential function (Supplementary Material) using kMax-app determined from the hyperbolic fit (Figure 4E, Supplementary Figure S3B). The deconvolution yields the association and dissociation rates for the dimer, kon-dimer and koff-dimer, respectively. The  distribution of X0 gave the parameters kon-dimer = 7.6 ± 0.3 × 107 M−1 s−1 and koff-dimer = 0.024 ± 0.006 s−1. The relatively fast kon-dimer ensures rapid formation of GEN1 dimer, whereas the relatively slow koff-dimer supports the forward reaction to proceed to catalysis once the dimer is formed. The Probability Density Functions (PDF) of the

distribution of X0 gave the parameters kon-dimer = 7.6 ± 0.3 × 107 M−1 s−1 and koff-dimer = 0.024 ± 0.006 s−1. The relatively fast kon-dimer ensures rapid formation of GEN1 dimer, whereas the relatively slow koff-dimer supports the forward reaction to proceed to catalysis once the dimer is formed. The Probability Density Functions (PDF) of the  distributions (Figure 4F) were constructed from the derivative of the CDF. The distributions are broad at low GEN1 concentrations due to the longer duration for dimer formation, then become narrow at higher GEN1 concentrations as the dimer is readily formed. To demonstrate that binding proceeds by the association of one GEN1 monomer at a time to the HJ, we performed Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) at the lowest possible X0 concentration within our detection limit (50 pM). The equilibrium dissociation constant of GEN1 monomer (Kd-monomer-EMSA) is consistent with that observed from smFRET Kd-monomer-app (Supplementary Figures S4A, C; respectively). On the other hand, the equilibrium dissociation constant of GEN1 dimer (Kd-dimer-EMSA) was determined from the association of a second GEN1 monomer to the first complex thus forming a dimer (Supplementary Figure S4A). Besides, we observed higher order oligomers as previously reported (27,33), which seemed not to interfere with catalysis even at 5-fold higher concentrations than those used in EMSA (Supplementary Figures S4A, G).

distributions (Figure 4F) were constructed from the derivative of the CDF. The distributions are broad at low GEN1 concentrations due to the longer duration for dimer formation, then become narrow at higher GEN1 concentrations as the dimer is readily formed. To demonstrate that binding proceeds by the association of one GEN1 monomer at a time to the HJ, we performed Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) at the lowest possible X0 concentration within our detection limit (50 pM). The equilibrium dissociation constant of GEN1 monomer (Kd-monomer-EMSA) is consistent with that observed from smFRET Kd-monomer-app (Supplementary Figures S4A, C; respectively). On the other hand, the equilibrium dissociation constant of GEN1 dimer (Kd-dimer-EMSA) was determined from the association of a second GEN1 monomer to the first complex thus forming a dimer (Supplementary Figure S4A). Besides, we observed higher order oligomers as previously reported (27,33), which seemed not to interfere with catalysis even at 5-fold higher concentrations than those used in EMSA (Supplementary Figures S4A, G).

We next compared our smFRET cleavage kinetics with those from bulk assays at the same temperature (22°C). The time-course cleavage reactions were performed using 2 nM X0 and different GEN1 concentrations. The pseudo-first-order reaction rates (kapp-bulk) at different GEN1 concentrations followed a sigmoidal curve (Figure 4G, Supplementary Figure S5C). The resulting single turnover rate (kSTO) at 0.071 ± 0.004 s−1 was not far from kMax-app of 0.107 ± 0.011 s−1 obtained via smFRET. The individual rates are listed in Supplementary Materials Table SIII. This slight difference in rates between bulk- and single-molecule cleavages is likely due to the lower temporal resolution in our bulk assays. Nonetheless, the prominent similarity between kSTO and kMax-app indicates that the majority of the reaction time in smFRET is used for catalysis by GEN1 dimer. The cleavage activity of CtGEN1 varied with different monovalent ions showing 2-fold increase in K+ compared to Na+ in the presence of Mg2+ (55). Performing the cleavage reaction using human GEN11–527 in Tris buffer pH 7.5 and either K+ or Na+ at the standard 22°C, the rates were comparable but just slightly higher in Na+ than in K+ (Supplementary Figure S5D).

The resolution reaction by GEN1 is proposed to be susceptible to substrate inhibition (27,34,35). Therefore, we expect k1/2-dimer to be substrate-concentration dependent. We estimated the effect of substrate inhibition by factoring in kon-dimer from the deconvolution (Figure 4E), kSTO from bulk cleavage (Figure 4G) and Kd-dimer-EMSA into the following equation (56).

|

(1) |

By substitution in Equation (1) and using results of EMSA at 2 nM X0, we estimated k1/2-dimer to be 23.40 nM + 0.93 nM = 24.33 nM, which is similar to the k1/2-dimer-bulk determined from the sigmoidal fit of the bulk cleavage (Figure 4G). Next, we computationally determined k1/2-dimer under limited substrate concentration using the first-order ‘total quasi-steady-state approximation’ (tQSSA) (Supplementary Figure S5E). This approximation holds under the criteria of high enzyme excess compared to substrate, and thereby evaluates the half-maximum catalytic activity regardless of substrate inhibition. The tQSSA yielded a much reduced k1/2-dimer of 6.92 ± 0.35 nM under limited substrate concentration. However, this estimation agrees well with the k1/2-dimer when substituting for Kd-dimer-EMSA at 50 pM X0 in Equation (1), i.e. 6.23 nM + 0.93 nM = 7.26 nM, demonstrating that k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA provides a good approximation for the catalytic activity of GEN1 under limited substrate concentration.

A fail-safe mechanism to ensure the symmetrical cleavage of the HJ

For the following set of experiments, we used a pre-nicked junction to decouple first- and second-cleavages and as a prototype for the partially unresolved HJ in the unlikely event that GEN1 dimer, or one of its monomers, dissociates after the first cleavage. We show that GEN1 monomer binds extremely tightly to safe-guard this substrate eventually ensuring full resolution through dimer formation. The FRET histogram of the adjacent-label phosphorylated nk-X0 in the presence of Ca2+ shows a single peak centered at E ≈ 0.45 (Supplementary Figure S6A). Upon binding and distortion by GEN1 monomer at concentrations as low as 25 pM, nk-X0 displays low FRET (E ≈ 0.25) similar to that of GEN1-X0 (Supplementary Figure S6A). Interestingly, nk-X0 has a very low Kd-monomer-app (47.24 ± 7.55 pM) (Figure 5A, Supplementary Figure S6A). This Kd-monomer-app is 40-fold lower than that of X0 (cf. Figure 4C) as determined by smFRET and is consistent with that observed from EMSA at 50 pM (cf. Supplementary Figures S4A, B). The difference in Kd-monomer-app between the nicked and the intact junctions is most likely caused by a difference in the on-rate of GEN1 monomer since we do not observe monomer dissociation for both junctions (Figures 4A and 5B). In a control experiment, we decoupled the first and second cleavages by substituting one of the scissile phosphate bonds by a phosphorothioated group (33) in an intact substrate. We found using smFRET that GEN1 cleaves this HJ generating a similar structure to the synthetically made nk-X0 junction and binds it equally tightly (Supplementary Figure S7). In contrast to the higher affinity of GEN1 monomer to nk-X0, the Kd-dimer-EMSA (10.60 ± 0.50 nM) of this substrate is only 2-fold higher than the respective value of X0 at a substrate concentration of 50 pM (cf. Supplementary Figure S4A).

Figure 5.

Fail-safe mechanism to ensure the symmetrical cleavage of the HJ (A) The binding isotherm of nk-X0 is constructed from the percentage of bound substrate as a function of GEN1 concentration (Supplementary Figure S6A). The Kd-monomer-app is determined from the hyperbolic fit to the binding isotherm. (B) FRET time trace of uncleaved nk-X0 is acquired by direct donor excitation as described in Figure 4A. These traces were observed from Kd-monomer-app until a few nanomolar GEN1 concentration. (C) Upper panel: FRET time trace of a cleaved nk-X0 junction demonstrates the low FRET state before cleavage followed by the disappearance of the FRET signal. Lower panel: The fluorescence of the donor and the acceptor from FRET and direct excitation are lost after cleavage. (D) The plot of kapp of nk-X0 versus GEN1 concentration is fitted to a hyperbolic function. (E) The CDF plot is derived from fitting the  distribution at the respective GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential model (Supplementary Figure S6B). (F) The PDF plot of the

distribution at the respective GEN1 concentration to a bi-exponential model (Supplementary Figure S6B). (F) The PDF plot of the  distributions and the respective kapp rates. (G) Plot of kapp-bulk of nk-X0 as a function of GEN1 concentration. k1/2-dimer-bulk was determined from the sigmoidal fit. k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA was determined by tQSSA (Supplementary Figure S5F).

distributions and the respective kapp rates. (G) Plot of kapp-bulk of nk-X0 as a function of GEN1 concentration. k1/2-dimer-bulk was determined from the sigmoidal fit. k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA was determined by tQSSA (Supplementary Figure S5F).

The FRET time traces of the uncleaved nk-X0 in Mg2+ were observed from around Kd-monomer-app until GEN1 concentrations of few nanomolar indicating predominant monomer binding (Figure 5B). The FRET time trace of the cleaved particle in Figure 5C shows the low FRET state upon distortion by GEN1 monomer followed by cleavage and loss of FRET subsequent to dimer formation. The kMax-app of 0.231 ± 0.036 s-1 was obtained from fitting kapp as a function of GEN1 concentration to a hyperbolic equation (Figure 5D). The deconvolution of the rates from the CDF of the  distributions via a bi-exponential function (Figure 5E, Supplementary Figure S6B) yielded kon-dimer of 2.2 ± 0.1 × 107 M−1 s−1 and no koff-dimer indicating tighter binding of the dimer, once formed, to nk-X0 than to X0. The PDF of the

distributions via a bi-exponential function (Figure 5E, Supplementary Figure S6B) yielded kon-dimer of 2.2 ± 0.1 × 107 M−1 s−1 and no koff-dimer indicating tighter binding of the dimer, once formed, to nk-X0 than to X0. The PDF of the  distribution of nk-X0 at each respective GEN1 concentration is shown in Figure 5F. Similar to X0, the PDFs at low GEN1 concentrations are skewed towards longer durations and converge to shorter times when the dimer is readily formed at high GEN1 concentrations.

distribution of nk-X0 at each respective GEN1 concentration is shown in Figure 5F. Similar to X0, the PDFs at low GEN1 concentrations are skewed towards longer durations and converge to shorter times when the dimer is readily formed at high GEN1 concentrations.

The kSTO from bulk cleavage of nk-X0 (Figure 5G) is nearly 2-fold faster than that of X0 (cf. Figure 4G; Supplementary Figure S5C). As a result of the 2-fold kMax-app (kSTO) and 0.3-fold kon-dimer of the nicked compared to the intact junction, the plots of kapp (kapp-bulk) for X0 and nk-X0 junctions intersect at a particular GEN1 concentration above which kapp (kapp-bulk) of nk-X0 prevails in both smFRET (Supplementary Figure S6C) and bulk cleavage (Supplementary Figure S5C), respectively. Similar to X0, we estimated k1/2-dimer based on EMSA performed at 50 pM and 2 nM nk-X0 substrate (Supplementary Figure S4B and D), respectively. Using Equation (1) at 50 pM nk-X0, we estimated k1/2-dimer to be 10.6 nM + 4.8 nM = 15.4 nM and the result from tQSSA was 19.09 ± 0.95 nM (Supplementary Figure S5F). Using EMSA at 2 nM nk-X0, we estimated k1/2-dimer to be 28.80 nM + 4.8 nM = 33.6 nM, which is very close to the k1/2-dimer-bulk obtained from the sigmoidal fit (Figure 5G). The k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA constants of X0 and nk-X0 under limited substrate concentrations are 6.92 ± 0.35 nM and 19.09 ± 0.95 nM, respectively (Supplementary Figure S5E and F). The k1/2-dimer-bulk constants of 26.6 ± 1.1 nM and 29.8 ± 0.8 nM for X0 and nk-X0, respectively, obtained from the sigmoidal fit of bulk cleavage are caused by substrate inhibition as demonstrated by the higher Kd-dimer-EMSA from EMSA at 2 nM. Therefore, the choice of substrate concentration is an important factor. Our smFRET cleavage assay circumvents this limitation since substrate concentration is always limited. A recent study suggested that the half-maximum catalytic activity of GEN1 (D. Melanogaster) is attained at concentrations between 0.1 and 1.1 μM. However, their binding and cleavage studies were performed at vastly different substrate concentrations yielding a high value for half-maximum catalytic activity most probably due to substrate inhibition (34).

In summary (Figure 6), the dependence of  distributions on GEN1 concentration provides strong evidence that cleavage of both nk-X0 and X0 proceeds via dimer formation. The strong binding of GEN1 monomer to the nk-X0 junction can be considered as a fail-safe mechanism against any scenario that may abort the second cleavage. This mechanism ensures full resolution of the HJ within the lifetime of GEN1 dimer. This includes the unlikely event of GEN1 dimer or one of its monomers dissociating after the first incision. Additionally, it allows GEN1 to effectively bind and then resolve to completion any nicked HJs left behind by other primary pathways, thereby safe-guarding genomic stability.

distributions on GEN1 concentration provides strong evidence that cleavage of both nk-X0 and X0 proceeds via dimer formation. The strong binding of GEN1 monomer to the nk-X0 junction can be considered as a fail-safe mechanism against any scenario that may abort the second cleavage. This mechanism ensures full resolution of the HJ within the lifetime of GEN1 dimer. This includes the unlikely event of GEN1 dimer or one of its monomers dissociating after the first incision. Additionally, it allows GEN1 to effectively bind and then resolve to completion any nicked HJs left behind by other primary pathways, thereby safe-guarding genomic stability.

Figure 6.

Timeline representation of GEN1 interaction with the HJ. The steps involved in the resolution of GEN1 of the HJ include: DNA conformational capturing (one isomer is selected for simplicity), DNA molding by GEN1 monomer, dimer formation, first cleavage, second cleavage and product release. The diagram sketches a fail-safe mechanism in case GEN1 dimer or one of its monomers dissociates after the first cleavage of the complex. The asterisk indicates that the order of cleavage can be interchangeable.

DISCUSSION

GEN1 mainly processes four-way junctions, where the outcome of genetic recombination is influenced by the stacking conformer bias, which in turn sets the orientation of the HJ resolution. In this study, we applied smFRET to gain real-time structural and mechanistic insights into the events involved in the binding and resolution of the HJ by GEN1.

Using static HJs with different isomer preferences, we demonstrated that GEN1 monomer captures the dynamically interchanging isomers following their abundance (conformational capturing) and actively molds the HJ (induced fit) in agreement with the predictions of the crystal model (36). We further established that GEN1 monomer alone is capable of distorting the HJ. This distorted structure projects the HJ for the second GEN1 monomer to bind before licensing catalysis. DNA-induced fit binding has also been illustrated in FEN1 and Exo1, two members of the 5′ nuclease superfamily to which GEN1 belongs (39,57). Increasing structural evidence also suggests that the proteins undergo conformational changes upon DNA binding, which control active-site assembly in GEN1 (35,36), FEN1 (37,41) and Exo1 (42,43). However, it is unclear if the protein uses induced-fit or conformational selection to verify the substrate. In the case of FEN1, the protein uses an induced-fit mechanism where it actively pulls out a nucleotide at the 3′ end of the nick junction to drive protein ordering (39,40). This step locks the protein and the DNA interactions to verify their ability to promote the transition state (39,57,58).

Performing cleavage using smFRet along with supporting bulk cleavage and binding assays, we showed that the stable binding of GEN1 monomer always ensures the progress of the forward reaction towards dimer formation. GEN1 monomer binding is supported by the following lines of evidence. First, several traces at GEN1 concentrations below Kd-monomer-app are distorted without being cleaved in presence of Mg2+. Second, FRET efficiency of that state before cleavage remains the same. If GEN1 were to dissociate prior to full resolution, an intermediary FRET state of a free nicked junction would be observed, which is not the case. However, the similarity in FRET between both GEN1 bound nicked and bound intact junctions prevents ruling out the possibility that GEN1 monomer nicks the HJ and remains bound until the dimer is formed to perform the second cleavage. Third, GEN1 concentration-dependence of  provides direct evidence for the initial monomer binding followed by dimer formation. Fourth, the binding of GEN1 monomer is greatly enhanced for the nicked junction, where Kd-monomer-app is in the picomolar range, yet the HJ resolution still requires dimer formation as shown by the concentration-dependence of

provides direct evidence for the initial monomer binding followed by dimer formation. Fourth, the binding of GEN1 monomer is greatly enhanced for the nicked junction, where Kd-monomer-app is in the picomolar range, yet the HJ resolution still requires dimer formation as shown by the concentration-dependence of  . This is also supported by Kd-dimer-EMSAand k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA of nk-X0 being in the nanomolar range similar to the intact junction. Therefore, monomer to dimer transition is at the heart of the resolution mechanism and is the essential step before GEN1-HJ complex is poised for catalysis. Moreover, based on the crystal model, it was proposed that the activity of GEN1 monomer is suppressed by a partially-disordered active-site region adjacent to the dimer interface (36). This suggests that this region of the active-site becomes structured only when a dimer is bound to the HJ (36).

. This is also supported by Kd-dimer-EMSAand k1/2-dimer-bulk-tQSSA of nk-X0 being in the nanomolar range similar to the intact junction. Therefore, monomer to dimer transition is at the heart of the resolution mechanism and is the essential step before GEN1-HJ complex is poised for catalysis. Moreover, based on the crystal model, it was proposed that the activity of GEN1 monomer is suppressed by a partially-disordered active-site region adjacent to the dimer interface (36). This suggests that this region of the active-site becomes structured only when a dimer is bound to the HJ (36).

The deconvolution of  distributions of the intact and nicked HJs using a bi-exponential model characterized the rates of dimer formation, dissociation and substrate affinity. These kinetic parameters showed clearly how GEN1 dimer ensures the forward reactions to perform both incisions. The relatively fast kon-dimer and slow koff-dimer support fast formation of GEN1 dimer and the subsequent two cleavages. The koff-dimer of the nicked HJ is even slower than that of the intact HJ suggesting that GEN1 dimer also strengthens its binding to the HJ after it performs the first incision.

distributions of the intact and nicked HJs using a bi-exponential model characterized the rates of dimer formation, dissociation and substrate affinity. These kinetic parameters showed clearly how GEN1 dimer ensures the forward reactions to perform both incisions. The relatively fast kon-dimer and slow koff-dimer support fast formation of GEN1 dimer and the subsequent two cleavages. The koff-dimer of the nicked HJ is even slower than that of the intact HJ suggesting that GEN1 dimer also strengthens its binding to the HJ after it performs the first incision.

The interplay between monomer binding, dimer formation and catalytic rate of resolution can be demonstrated by kapp of GEN1 on the intact and nicked junctions at different regimes of enzyme concentration. The topological constraints in the intact junction seem to favor dimerization more than in the relaxed nicked junction. This difference in kon-dimer resulted in higher kapp in smFRET and kapp-bulk in bulk for the intact junction at low GEN1 concentrations. At high GEN1 concentrations, where dimer is readily formed for both junctions, the kMax-app and kSTO of nk-X0 are twice that of X0 in both smFRET and bulk, respectively. This may be because only one incision is needed to resolve the nicked junction.

The resolution of HJs by resolvases takes place by two consecutive, but uncoupled, strand cleavages (59). RuvC, which exists as a homodimer in clear distinction to GEN1, has been considered as the counterpart resolvase to GEN1 due to the similarities in several functional aspects. It was reported that the second incision in RuvC is 150-fold faster than the first incision based on the acceleration of the cleavage of a transient nicked junction (60). This mechanism is proposed to ensure that the second cleavage takes place within the lifetime of the resolvase-HJ complex. The acceleration of the second cleavage was reported in quantitative kinetic studies based on the supercoiled cruciform substrate which showed 11-fold (61) and 17-fold acceleration of the second strand cleavage of the junction in presence of Mg2+ and K+ ions (55). We cannot assign the rates of the first and the second incisions nevertheless we can measure the dimer lifetime on the nicked and intact HJs. The acceleration of the second cleavage can be beneficial for achieving the HJ resolution within the lifetime of the complex. However, whether this acceleration is absolutely required for full resolution of the HJ may be questioned by some observations. First, the dimer lifetime is much longer than the time required for cleavage providing sufficient time to cleave as a complex even without acceleration of the second cut. Second, even if the second subunit of GEN1 falls off before complete resolution, producing a nicked-HJ, the remaining GEN1 monomer has very high affinity to the nicked product and will drive as many dimer formation cycles as necessary for complete resolution regardless of second strand cleavage acceleration. Third, the dimer once formed on the nicked junction has even longer lifetime than on the intact junction.

The production of partially-resolved junctions either through the unlikely event of the dissociation of GEN1 dimer or as a byproduct from other primary pathways can be detrimental to the cells. The high affinity of GEN1 monomer to the nicked junction and the stability of the dimer on the same substrate ensure a fail-safe mechanism for the resolution of partially processed HJs. In addition, other members of the XPF family of endonucleases have strong affinity for binding and cleaving nicked HJs such as Mus81 which acts in conjunction with a partner protein EME1 (62). The tight binding of GEN1 monomer to the nicked HJ additionally provides a fail-safe mechanism if one of GEN1 monomers dissociates prior to performing the second cleavage. The stringent requirement to cleave the nicked HJs also by a dimer may be critical to generate a ligatable nicked-DNA product, since the two cleavages are usually marked by the alignment of the dimer active-sites in resolvases in general (31,63).

It is unclear why GEN1 deviates from other resolvases in the fact that it exists as a monomer in solution rather than as a dimer. GEN1 acts on its own by engaging in a distinctive monomer to dimer transition with which it alternates between a tight binding mode and a catalytic mode. The tight binding mode of GEN1 monomer to intact and nicked HJs might be instrumental for its action as a last-line guardian of genomic stability. It is possible that monomeric GEN1 is more suitable for screening the DNA for HJs. GEN1 monomer may also have other functionalities in vivo. For instance, it has been shown that GEN1 monomer cleaves the 5′ flap substrate more effectively than the HJ (27,34) but the biological role of this cleavage remains largely unknown. It might be possible that GEN1 monomer plays a role in handling aberrant flap structures during long patch base excision repair or flaps containing mismatches and G-quadruplex structures after the dissolution of the nuclear membrane. The tight binding of GEN1 monomer to four-way junctions may also have other biological relevance in stabilizing fork reversal intermediates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Prof. Yuji Iwata for his help in the initial stage of cloning GEN1. We thank Yujing Ouyang for the preparation of the functionalized cover slips. We thank Dr Susan Tsutakawa, Prof. John Tainer and Dr Maged Serag for thoughtful discussions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology through core funding and Competitive Research Award [CRG3 to S.M.H.]. Funding for open access charge: King Abdullah University of Science and Technology through CRG3.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holliday R. Mechanism for gene conversion in fungi. Genet. Res. 1964; 5:282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. West S.C. Formation, translocationand resolution of Holliday junctions during homologous genetic recombination. Philos. Trans.R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 1995; 347:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cox M.M., Goodman M.F., Kreuzer K.N., Sherratt D.J., Sandler S.J., Marians K.J.. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature. 2000; 404:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. West S.C. Molecular views of recombination proteins and their control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003; 4:435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Potter H., Dressler D.. On the mechanism of genetic recombination: electron microscopic observation of recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1976; 73:3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bell L., Byers B.. Occurrence of crossed strand-exchange forms in yeast DNA during meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979; 76:3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwacha A., Kleckner N.. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell. 1995; 83:783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bzymek M., Thayer N.H., Oh S.D., Kleckner N., Hunter N.. Double Holliday junctions are intermediates of DNA break repair. Nature. 2010; 464:937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duckett D.R., Murchie A.I., Diekmann S., von Kitzing E., Kemper B., Lilley D.M.. The structure of the Holliday junction, and its resolution. Cell. 1988; 55:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clegg R.M., Murchie A.I., Zechel A., Carlberg C., Diekmann S., Lilley D.M.. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis of the structure of the four-way DNA junction. Biochemistry. 1992; 31:4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grainger R.J., Murchie A.I., Lilley D.M.. Exchange between stacking conformers in a four-Way DNA junction. Biochemistry. 1998; 37:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKinney S.A., Declais A.C., Lilley D.M., Ha T.. Structural dynamics of individual Holliday junctions. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003; 10:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Gool A.J., Hajibagheri N.M.A., Stasiak A., West S.C.. Assembly of the Escherichia coli RuVABC resolvasome directs the orientation of Holliday junction resolution. Gene Dev. 1999; 13:1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raynard S., Bussen W., Sung P.A.. double Holliday junction dissolvasome comprising BLM, topoisomerase III alpha, and BLAP75. J. Biol. Chem. 2006; 281:13861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu L., Bachrati C.Z., Ou J.W., Xu C., Yin J.H., Chang M., Wang W.D., Li L., Brown G.W., Hickson I.D.. BLAP75/RMI1 promotes the BLM-dependent dissolution of homologous recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bussen W., Raynard S., Busygina V., Singh A.K., Sung P.. Holliday junction processing activity of the BLM-topo III alpha-BLAP75 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007; 282:31484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu L., Hickson I.D.. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003; 426:870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plank J.L., Wu J.H., Hsieh T.S.. Topoisomerase III alpha and Bloom's helicase can resolve a mobile double Holliday junction substrate through convergent branch migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:11118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raynard S., Zhao W.X., Bussen W., Lu L., Ding Y.Y., Busygina V., Meetei A.R., Sung P.. Functional role of BLAP75 in BLM-topoisomerase III alpha-dependent Holliday junction processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2008; 283:15701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yin J.H., Sobeck A., Xu C., Meetei A.R., Hoatlin M., Li L., Wang W.D.. BLAP75, an essential component of Bloom's syndrome protein complexes that maintain genome integrity. EMBO J. 2005; 24:1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen X.B., Melchionna R., Denis C.M., Gaillard P.H.L., Blasina A., Van de Weyer I., Boddy M.N., Russell P., Vialard J., McGowan C.H.. Human Mus81-associated endonuclease cleaves holliday junctions in vitro. Mol. Cell. 2001; 8:1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ciccia A., Constantinou A., West S.C.. Identification and characterization of the human Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003; 278:25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fekairi S., Scaglione S., Chahwan C., Taylor E.R., Tissier A., Coulon S., Dong M.Q., Ruse C., Yates J.R., Russell P. et al. Human SLX4 is a Holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell. 2009; 138:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wyatt H.D., Sarbajna S., Matos J., West S.C.. Coordinated actions of SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 for Holliday junction resolution in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2013; 52:234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wyatt H.D., Laister R.C., Martin S.R., Arrowsmith C.H., West S.C.. The SMX DNA repair Tri-nuclease. Mol. Cell. 2017; 65:848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ip S.C., Rass U., Blanco M.G., Flynn H.R., Skehel J.M., West S.C.. Identification of Holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature. 2008; 456:357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rass U., Compton S.A., Matos J., Singleton M.R., Ip S.C., Blanco M.G., Griffith J.D., West S.C.. Mechanism of Holliday junction resolution by the human GEN1 protein. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan Y.W., West S.C.. Spatial control of the GEN1 Holliday junction resolvase ensures genome stability. Nat. Commun. 2014; 5:4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Interthal H., Heyer W.D.. MUS81 encodes a novel helix-hairpin-helix protein involved in the response to UV- and methylation-induced DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mo.l Gen. Genet. 2000; 263:812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wechsler T., Newman S., West S.C.. Aberrant chromosome morphology in human cells defective for Holliday junction resolution. Nature. 2011; 471:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West S.C., Chan Y.W.. Genome instability as a consequence of defects in the resolution of recombination intermediates. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2018; 82:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]