Abstract

Bradyrhizobium is one of the most cosmopolitan and diverse bacterial group nodulating a variety of host legumes in Africa, however, the diversity and distribution of bradyrhizobial symbionts nodulating indigenous African legumes are not well understood, though needed for increased food legume production. In this review, we have shown that many African food legumes are nodulated by bradyrhizobia, with greater diversity in Southern Africa compared to other parts of Africa. From a few studies done in Africa, the known bradyrhizobia (i.e., Bradyrhizobium elkanii, B. yuanmingense) along with many novel Bradyrhizobium species are the most dominant in African soils. This could be attributed to the unique edapho-climatic conditions of the contrasting environments in the continent. More studies are needed to identify the many novel bradyrhizobia resident in African soils in order to better understand the biogeography of bradyrhizobia and their potential for inoculant production.

Keywords: biogeography, cowpea, groundnut, Bambara groundnut, wild legumes, soil factors, novel species

Introduction

Globally, farmers depend on N fertilizers for increased crop yields (Crews and Peoples, 2004). Even then, sub-Saharan Africa currently uses the least chemical fertilizers compared to other regions (Ruben et al., 2007), due largely to high cost of these inputs for resource-poor farmers, their inaccessibility and potential to pollute the environment, as well as poor infrastructure (Dakora and Keya, 1997; Chianu et al., 2011). These factors together have limited the use of N fertilizers in African agriculture, even though there is a growing demand for increased crop production to feed the growing population (Dakora and Keya, 1997; Aticho et al., 2011; Chianu et al., 2011; Lal and Stewart, 2013). To feed the expected 2.5 billion people by 2050, Africa will need to roughly double its agricultural production. Food production is, however, associated with environmental pollution from anthropogenic activity. For example, the current level of industrialization has been achieved with 70% of the water used by people, 80% of deforestation worldwide, 70% loss of biodiversity and nearly one-quarter of the total greenhouse gas emissions (Tilman et al., 2011; Kessy et al., 2016). The world therefore urgently needs to increase agricultural productivity in a sustainable and environmentally-friendly manner. The large increase in population observed today would require at least 20% increase in crop yields in order to meet global food/nutritional security (Evans and von Caemmerer, 2011). This in turn may require the expansion of agricultural activity into marginal and/or non-arable land in order to feed the growing human population (Hungria and Vargas, 2000).

Africa is one of the major centers of legume diversity in the world, and is therefore home to a large number of indigenous legume species (Sprent, 2009; Beukes et al., 2013). In Africa, grain legumes remain the key source of dietary protein and starch (Bezner Kerr et al., 2007). Legumes also serve as high protein feed for livestock production, and biofertilizer for maintaining soil productivity. Therefore, legume inclusion in cropping systems has the potential to increase crop yields, which are currently very low at farm level in Africa when compared to the rest of the world (Akibode, 2011). Furthermore, N2 fixation in legumes can provide economic, environmental and agronomic benefits to farmers in Africa where socio-economic conditions are poor (Chianu et al., 2011; Siddique et al., 2011). It is thus not surprising that BNF is the most important biological process on earth after photosynthesis (Unkovich et al., 2008) as it not only reduces fossil energy use globally, but also sustainably promotes increased agricultural yields without environmental damage. BNF is, however, influenced by many factors, which include geographic location, soil type, host–plant genotypes, and the rhizobial symbionts (Jaiswal et al., 2017).

Of the proteobacteria, Bradyrhizobium is an ancestral symbionts and highly cosmopolitan in terms of its distribution as a free-living bacterium in different habitats and in symbiosis with diverse leguminous hosts (Sprent et al., 2017). Like other N2-fixing microsymbionts, Bradyrhizobium exhibits a bipartite life cycle which alternates between the free-living state in soils and as a symbiotic partner inside root nodules of legumes. Its chromosome is also bipartite in nature, with the main chromosomal genes being largely expressed under free-living conditions, and symbiosis genes expressed in planta. The plasmids or genomic island of root-nodule bacteria harbor all the symbiotic genes, which are usually transmitted vertically, or horizontally between different chromosomal backgrounds.

The interaction of legumes with root-nodule bacteria has become a model for dissecting the molecular conversation between rhizobial strains and their host plants, and is the best understood mutualistic relationship, especially when compared to other systems such as the mycorrhizal symbiosis with land plants and the Frankia symbiosis with actinorhizal plants.

While we currently have a clearer understanding of the molecular signals involved in the early stages of nodule formation, these insights get masked by the diversity of legumes and their rhizobia, as well as the ecological niches that interact to produce root nodules. As a result, we do not know how natural selection shapes each partner, as well as the extent to which the interaction can vary depending on intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

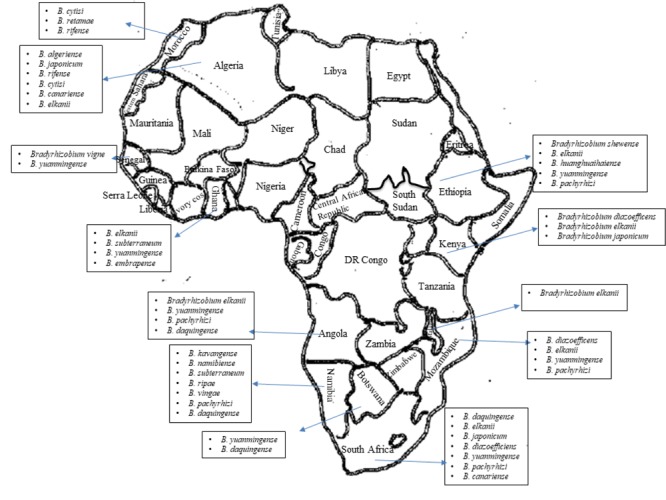

Also, we still do not understand the community structure and composition of bradyrhizobia found in African soils, even though we know that only certain types of bradyrhizobia are known to nodulate the diverse range of legumes grown in Africa (see Figure 1). Studies based on a few African countries seem to suggest that the number, species and strains of bradyrhizobial populations found in African soils are individually and collectively much greater than that shown in Figure 1. Only future studies will unravel the scale of novel bradyrhizobia resident in African soils that are waiting to be discovered and identified using modern molecular technologies. This review summarizes the status of legume root nodulation by bradyrhizobia in Africa.

FIGURE 1.

Presence of diverse bradyrhizobial population in African soils.

Legumes Nodulated by Bradyrhizobium Species in African Soils

Reports on legume nodulation by Bradyrhizobium in Africa are rather scanty in terms of (i) the diversity of legumes studied (ii) the types and numbers of bradyrhizobial microsymbionts found to nodulate legumes in Africa, and (iii) the huge number of unknown bradyrhizobial isolates waiting to be delineated and identified. In our laboratory alone, we have studied and reported on the nodulation of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp), Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean L. Verdc), Kersting’s bean (Macrotyloma geocarpum Harns), groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.), common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and soybean (Glycine max L. Merr) in different agro-ecologies of selected African countries, which include Ghana, South Africa, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Zambia, Swaziland, and Mali. This review is a summary of our work together with those of others reported from across Africa. In this study, we intend to summarize data on Bradyrhizobium nodulation of cowpea, groundnut, soybean and Bambara groundnut together with data on nodulation of other wild African legumes by bradyrhizobia.

Diversity of Microsymbionts Nodulating Indigenous Vigna Species in Africa

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) is a major food crop in Africa, its organs such as leaves, green pods and grain are eaten as a source of protein (Pule-Meulenberg et al., 2010). It is a promiscuous legume that is often used to trap microsymbionts in soil during diversity studies (Guimarães et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2013; Jaramillo et al., 2013; Grönemeyer et al., 2015a, 2016; Chidebe et al., 2018). This legume can establish effective symbioses with diverse bacterial species belonging to the genera Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium (Wade et al., 2014; Chidebe et al., 2018). As a result, cowpea has the ability to grow in diverse environments where other legumes may fail to survive. The cowpea symbiosis can meet up to 96% of the plant’s N requirement, and contribute substantially to the N needs of subsequent cereal crops, especially where the soils are nutrient-poor (Peoples et al., 2009; Belane and Dakora, 2010). Some studies have shown that cowpea can derive as much as 66% or more of its N nutrition from symbiotic fixation in Botswana (Pule-Meulenberg and Dakora, 2009), up to 99% in Ghana (Naab et al., 2009), and 15–56% in Zimbabwe (Ncube et al., 2007). These differences in N obtained from symbiosis can be attributed to the functional diversity among the Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating cowpea in Africa (Pule-Meulenberg et al., 2010; Grönemeyer et al., 2014; Chidebe et al., 2018).

Earlier studies have identified Bradyrhizobium as the dominant microsymbiont nodulating cowpea in Botswana, Ghana, South Africa (Steenkamp et al., 2008; Pule-Meulenberg et al., 2010); Senegal (Wade et al., 2014), Mozambique (Chidebe et al., 2018), Ethiopia (Degefu et al., 2017), and Angola, as well as Namibia (Grönemeyer et al., 2014). Cowpea microsymbionts have a broad host nodulation range (Mpepereki et al., 1996). However, Africa is vast and agro-ecologically divergent, therefore many more studies are needed on the diversity and phylogeny of cowpea-nodulating microsymbionts in the continent, the center of its origin and diversification. The characterization of native rhizobia from the different geographic regions of Africa is likely to increase our understanding of their contribution to ecosystem functioning and thus help to unravel the factors shaping microsymbiont diversity and distribution in African soils.

Perhaps because Africa is the origin of cowpea, there is a vast diversity of cowpea rhizobia present in African soils (Steenkamp et al., 2008; Pule-Meulenberg et al., 2010; Wade et al., 2014; Degefu et al., 2017; Chidebe et al., 2018). This would be consistent with the view that the sites of origin of legumes tend to coincide with the centers of diversity of their associated microsymbionts needed for nodule formation and N2 fixation (Puozaa et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been argued that because Brazil and the Southern African region share similar climatic conditions (Chibeba et al., 2017) is probably the reason why only Southern Africa and Brazil have added more novel Bradyrhizobium species to that genus nodulating cowpea. The first cowpea-nodulating Bradyrhizobium was identified in the Amazon soils of Brazil, and classified as Bradyrhizobium manausense (Silva et al., 2014). Later, two Bradyrhizobium species [i.e., Bradyrhizobium kavangense (Grönemeyer et al., 2015b) and B. vignae (Grönemeyer et al., 2016)] were isolated from cowpea root nodules in Southern Africa (Namibia and Angola, respectively). More recently, B. brasilense (da Costa et al., 2017) was also identified in Brazilian soils (Table 1).

Table 1.

Morph-physiological and general characteristics of Bradyrhizobium type strains.

| Species name | Legume host | Origin | Tolerance to NaCl | Temperature range for growth (°C) | pH | Growth rate (h) and colony size (mm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. americanum | Centrosema macrocarpum | Venezuela | <1% | 15–35 | 6–8 | –(<1) | Ramírez-Bahena et al., 2016 |

| B. arachidis | Arachis hypogaea | China | < 1% | 20–30 | 6–8 | 8.8(-) | Wang R. et al., 2013 |

| B. algerians | Retama sphaerocarpa | Algeria | 1% | 28–30 | 4–8 | 14–23(-) | Ahnia et al., 2018 |

| B. betae | Beta vulgaris | Spain | 28–30 | 7.5 | Rivas et al., 2004 | ||

| B. brasilense | Vigna unguiculata | Brazil | 4–10 | da Costa et al., 2017 | |||

| B. cajani | Cajanus cajan | Dominican Republic | 18–37 | 5–9 | Araújo et al., 2017 | ||

| B. canariense | Chamaecytisus proliferus | Spain | 28–30 | 4–7 | Vinuesa et al., 2005 | ||

| B. centrolobii | Centrolobium paraense | Brazil | <1% | 20–36 | 5–11 | –(3–4) | Michel et al., 2017 |

| B. centrosemae | Centrosema molle | Venezuela | 1% | 10–37 | 4.5–7.5 | –(<1) | Ramírez-Bahena et al., 2016 |

| B. cytisi | Cytisus villosus | Morocco | <0.25 | 14–30 | 6–8 | Chahboune et al., 2011 | |

| B. daqingense | Glycine max | China | 1% | 28–37 | 6–9 | 10 (1) | Wang J.Y. et al., 2013 |

| B. denitrificans | - | Germany | 28–41 | Van Berkum et al., 2006 | |||

| B. diazoefficiens | Glycine max | Japan | <1% | 28 | 4.8–6.8 | –(1.2–1.5) | Delamuta et al., 2013 |

| B. elkanii | Glycine max | United States | Kuykendall et al., 1992 | ||||

| B. embrapense | Desmodium heterocarpon | Brazil | <1% | 28–37 | 4.5–8.0 | 7.49(-) | Delamuta et al., 2015 |

| B. erythrophlei | Erythrophleum fordii | China | 1% | 4–60 | 5–8 | 14.6 (<1) | Yao et al., 2015 |

| B. ferriligni | Erythrophleum fordii | China | 1% | 4–45 | 5-8 | 13.1 (1) | Yao et al., 2015 |

| B. forestalis | Amazon legume tree | Brazil | <1% | 15–37 | 4–10 | –(>1) | da Costa et al., 2018 |

| B. ganzhouense | Acacia melanoxylon | China | 3% | 4–37 | 5–12 | –(1–2) | Lu et al., 2014 |

| B. guangdongense | Arachis hypogaea | China | 1% | 15–28 | 5–7 | 16.94 (1–2-) | Li et al., 2015 |

| B. guangxiense | Arachis hypogaea | China | 1% | 15–28 | 5–7 | 13.49(1–2) | Li et al., 2015 |

| B. huanghuaihaiense | Glycine max | China | <1% | 10–37 | 6–9 | 7–9 (1) | Zhang et al., 2012 |

| B. icense | Phaseolus lunatus | Peru | 1% | 28 | 5.5–10 | 11–12(1) | Durán et al., 2014a |

| B. ingae | Inga laurina | Brazil, Roraima | <0.5% | 15–32 | 4–8 | 9.5(1) | da Silva et al., 2014 |

| B. iriomotense | Entada koshunensis | Japan, Okinawa | <1% | 15–32 | 4.5–9.0 | Islam et al., 2008 | |

| B. japonicum | Glycine max | Japan | <2% | 25–30 | 3.5–9.0 | –(<1) | Jordan, 1982 |

| B. jicamae | Pachyrhizus erosus | Honduras | 1% | 5–32 | 6–8 | – | Ramírez-Bahena et al., 2009 |

| B. kavangense | Vigna unguiculata | Namibia, Kavango | <1% | 28–38 | 5–9 | 7.5 (0.2–0.8) | Grönemeyer et al., 2015b |

| B. lablabi | Lablab purpureus | China | <1% | 10–37 | 5–10 | 10–12(<1) | Chang et al., 2011 |

| B. liaoningense | Glycine max | China | <1% | 25–30 | 7.45–8.08 | –(0.2–1) | Xu et al., 1995 |

| B. lupini | Lupinus angustifolius | United States | <1% | 28 | 7 | Peix et al., 2015 | |

| B. manausense | Vigna unguiculata | Brazil | <0.05 | 15–32 | 4–8 | 7.8 (1) | Silva et al., 2014 |

| B. macuxiense | Centrolobium paraense | Brazil | <1% | 20–36 | 5–11 | –(3–4) | Michel et al., 2017 |

| B. mercantei | Deguelia costata | Brazil | <1% | 28–30 | 4.5–8 | –(<1) | Helene et al., 2017 |

| B. namibiense | Lablab purpureus | Namibia | – | Grönemeyer et al., 2017 | |||

| B. neotropicale | Centrolobium paraense | Brazil, Roraima | <1.5% | 15–37 | 4–10 | 10.8 (1) | Zilli et al., 2014 |

| B. oligotrophicum | Rice | – | <0.5 | 28–37 | – | – | Ramírez-Bahena et al., 2013 |

| B. ottawaense | Glycine max | Canada | <1% | 20 | 5–10 | 12–13(<1) | Yu et al., 2014 |

| B. pachyrhizi | Pachyrhizus erosus | Honduras | <1% | 5–37 | 4.5–8 | – | Ramírez-Bahena et al., 2009 |

| B. paxllaeri | Phaseolus lunatus | Peru | 1% | 28–37 | 5.5–10 | 11–12(1) | Durán et al., 2014a |

| B. retamae | Retama sphaerocarpa | Morocco | <1% | 14–30 | 6–8 | –(<1) | Guerrouj et al., 2013 |

| B. rifense | Cytisus villosus | Morocco | <1% | 14–30 | 4.5–8.0 | (<1) | Chahboune et al., 2012 |

| B. ripae | Indigofera rautanenii | Namibia | Bünger et al., 2018 | ||||

| B. sacchari | Sugar cane | Brazil | <0.5 | 20–37 | 5–12 | –(1.5–2) | de Matos et al., 2017 |

| B. shewense | Erythrina brucei | Ethiopia | 0.5% | 15–30 | 5–10 | –(1–2) | Aserse et al., 2017 |

| B. stylosanthis | Stylosanthes guianensis | Brazil | <1% | 28 | 4.5–8.0 | (1–1.34) | Delamuta et al., 2016 |

| B. subterraneum | Vigna subterranea | Namibia, Kavango | <1% | 28–37 | 5–9 | 8 (0.2-1) | Grönemeyer et al., 2015a |

| B. tropiciagri | Neonotonia wightii | Brazil | <1% | 28 | 4.5–8.0 | 7.42(-) | Delamuta et al., 2015 |

| B. valentinum | Lupinus mariae-josephae | Spain | <1% | 14–30 | 4–10 | –(<2) | Durán et al., 2014b |

| B. vignae | Vigna unguiculata | Namibia | <1% | 28–40 | 5–9 | 8 (0.2–1) | Grönemeyer et al., 2016 |

| B. viridifuturi | Centrosema pubescens | Brazil | <1% | 28 | 4.5–7.0 | (0.5–1.5) | Helene et al., 2015 |

| B. yuanmingene | Lespedeza cuneata | China | <1% | 25–30 | 6.5–7.5 | 9.5–16(<1) | Yao et al., 2002 |

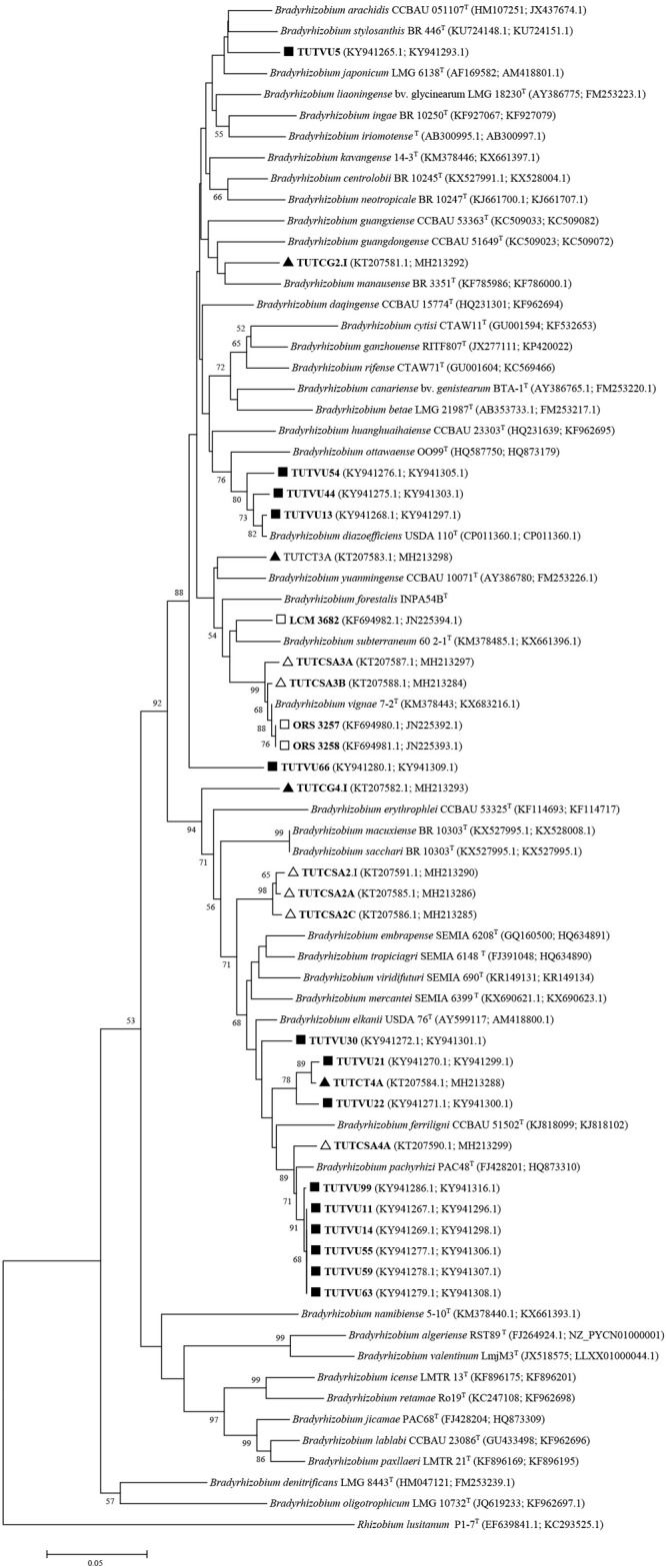

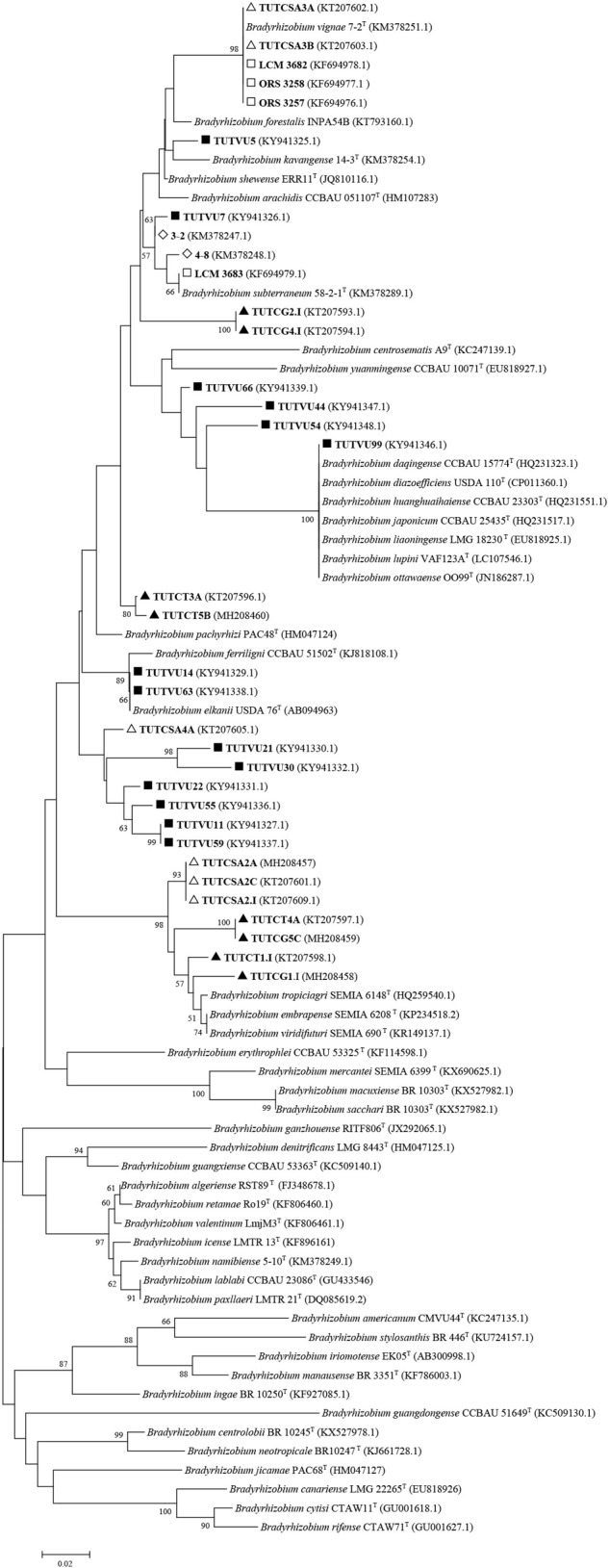

In a similar study, the soils of Botswana exhibited considerable diversity in the Bradyrhizobium species, (namely, B. yuanmingense, B. daquingense and a novel Bradyrhizobium sp.) that nodulated cowpea (Steenkamp et al., 2008). Studies in Senegal (West Africa) also revealed novel Bradyrhizobium species as the bacterial symbionts of cowpea, and these were closely related to B. yuanmingense (based on six loci sequence analysis) but symbiotically grouped with B. arachidis based on nodC and nifH gene analysis (Wade et al., 2014). A taxonomic revision of these novel Bradyrhizobium species showed that they belonged to B. vignae, which was originally isolated from cowpea nodules collected from Namibia (Figure 2, 3).

FIGURE 2.

Neighbor-joining molecular phylogenetic analysis of cowpea nodulating rhizobia from ▲Ghana, □ Senegal, ■ Mozambique, and △ South Africa based on concatenated glnII + gyrB (495 bp) sequences with type strains of Bradyrhizobium species. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Neighbor-joining method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

FIGURE 3.

Neighbor-joining molecular phylogenetic analysis of cowpea nodulating rhizobia from ▲Ghana, □ Senegal, ■ Mozambique,◇ Namibia△ and South Africa based on nifH (401 bp) sequences with type strains of Bradyrhizobium species. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Neighbor-joining method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

In studies of cowpea in the Okavango of Namibia, B. pachyrhizi was found to dominate in the acidic soils, while cowpea nodulation in the semi-humid region of Angola and Namibia was by diverse bradyrhizobial strains, most of them relating to B. yuanmingense and B. daqingense, as well as by some novel Bradyrhizobium species (Grönemeyer et al., 2014), which were later identified as B. kavangense, and B. vignae (Grönemeyer et al., 2015b, 2016).

Chidebe et al. (2018) recently found high molecular diversity among 122 microsymbionts isolated from Mozambican soils and characterized using BOX-PCR analysis, a finding confirmed by multilocus sequence analysis which showed that cowpea is nodulated by different Bradyrhizobium species (B. elkanii, B. yuanmingense, B. diazoefficiens, B. pachyrhizi, and novel Bradyrhizobium species), as well as by diverse Rhizobium species (Neorhizobium galegae, Rhizobium pusense, and Rhizobium tropici).

The Guinea savanna and Sudano-Sahelian regions of Ghana, as well as the low veld of South Africa were also explored for the biogeographic distribution of root-nodule bacteria nodulating cowpea in the two countries. In that study, sequence analysis of core genes (atpD, glnII, gyrB, and rpoB) and symbiotic genes (nifH and nodC) revealed the presence of highly diverse Bradyrhizobium species nodulating cowpea that were closely related to B. daqingense, B. subterraneum, B. yuanmingense, B. embrapense, B. pachyrhizi, and B. elkanii, as well as a number of unidentified novel Bradyrhizobium isolates (Mohammed et al., 2018). Multivariate analysis also showed that the distribution of these Bradyrhizobium species was strongly influenced by the concentration of mineral nutrients in the soils (Mohammed et al., 2018).

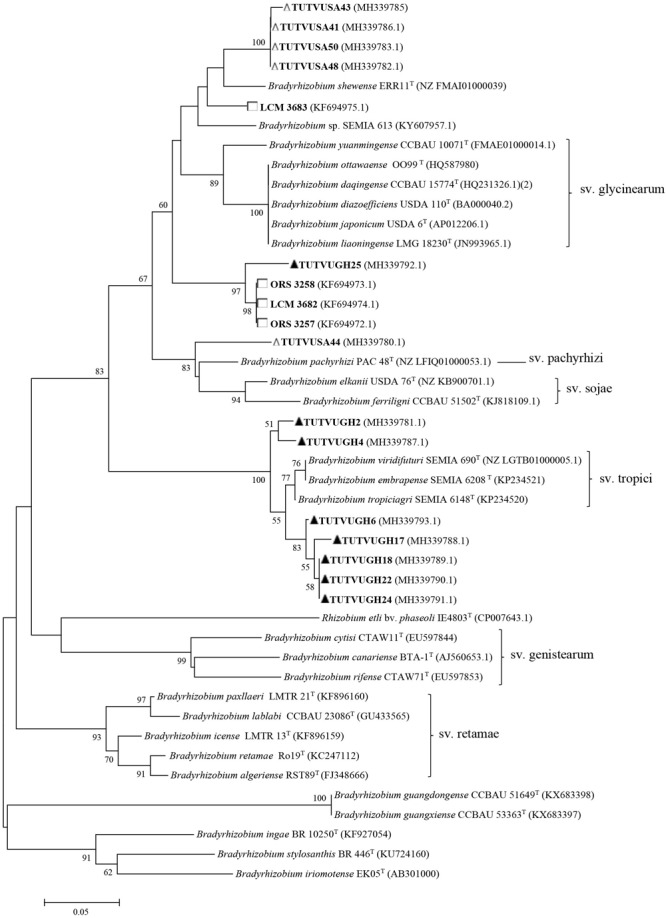

Some of the previously reported novel Bradyrhizobium sp. from Ghana, Senegal, Angola, Namibia, South Africa, and Mozambique, as well as those from our study were reanalyzed phylogenetically using previously and newly listed Bradyrhizobium type strains in the GenBank. The results showed that only the Senegalese isolates initially considered to be novel, were actually strains of B. vignae, while all the others remained novel Bradyrhizobium sp. with no alignment to any reference type strains in the GenBank (see Figure 2–4).

FIGURE 4.

Neighbor-joining molecular phylogenetic analysis of cowpea nodulating rhizobia from ▲Ghana, □ Senegal, and △ South Africa based on nodC sequences with type strains of Bradyrhizobium species. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Neighbor-joining method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6.

After cowpea, Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc.) is the second most important indigenous non-commercial food legume in Africa both in consumption and land area under cultivation. It is cultivated across the entire African continent, from Mauritania and Senegal in the West to Uganda and Tanzania in the East, and from Mali and Sudan in the North to South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Swaziland in the South. Bambara groundnut is cultivated as a sole or mixed culture (Doku, 1995), and is drought-tolerant, as well as performs well in very nutrient-poor soils due to its ability to form effective symbiosis with soil rhizobia that reduce atmospheric N2 to ammonia (Puozaa et al., 2017). Nitrogen contribution by Bambara groundnut under field and glasshouse conditions can vary significantly, with values ranging from 4 to 200 kg N ha-1 (Gueye and Bordeleau, 1988; Kumaga et al., 1994; Kishinevsky et al., 1996; Nyemba and Dakora, 2010; Mohale et al., 2013).

Analysis of nodules from Angola and Namibia have suggested that Bambara groundnut is nodulated by a diverse group of Bradyrhizobium species (Grönemeyer et al., 2014). Using RFLP analysis of root-nodule bacteria collected from South Africa, as well as the Guinea and sahelian Savanna of Ghana, Puozaa et al. (2017) found that diverse bradyrhizobia nodulate Bambara groundnut in those regions. These indigenous bradyrhizobia were closely related to B. vignae (Puozaa et al., 2017), which nodulates Vigna subterranea, Vigna unguiculata, Arachis hypogaea, and Lablab purpureus (Grönemeyer et al., 2014). However, some novel monophyletic groups were also identified which suggested the presence of novel Bradyrhizobium in the soils studied. Caballero-Mellado and Martinez-Romero (1996) have argued that the origins of legumes tend to coincide with the centers of diversity of their specific symbiotic bacteria. This supports the large diversity of Bradyrhizobium species found to nodulate Bambara groundnut in Africa (Grönemeyer et al., 2014; Puozaa et al., 2017), the center of origin of this legume. Taken together, the reports of various studies appear to suggest that Vigna species in Africa are largely nodulated by Bradyrhizobium bacteria. The huge functional diversity among microsymbionts nodulating Vigna indicate the potential for exploiting these diverse rhizobial populations for use as inoculants to increase cowpea and Bambara groundnut production in Africa.

Soybean Nodulation by Bradyrhizobium Species

Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) belongs to the tribe Phaseoleae, sub-tribe Glycininae, and genus Glycine. It originated from north-eastern China and is presently cultivated worldwide under various climatic conditions (Appunu et al., 2008; Risal et al., 2010; Singh, 2010). Soybean was probably introduced into Africa by Chinese traders traveling along the east coast of Africa in the 1800s (Shurtleff and Aoyagi, 2009). The average soybean yield in Africa is 1.0 ton per hectare compared with the world average of 2.35 ton per hectare (Abate et al., 2012). Africa is one of the largest importers of soybean in the world due to low local production, (Mutegi and Zingore, 2014).

As a legume, soybean obtains about 50–60% of its N nutrition from the atmosphere (Hardarson and Atkins, 2003; Salvagiotti et al., 2008). In Africa, N contribution by soybean is about 63 kg N ha-1 in Malawi (van Vugt et al., 2018), and up to 290 kg N ha-1 in South Africa (Mapope and Dakora, 2016).

Historically, soybean was believed to be nodulated by strains of only B. japonicum, which are not endemic to African soils. As a result, new soybean genotypes [Tropical Glycine cross (TGx)], were bred that would nodulate freely with Bradyrhizobium populations indigenous to African soils (Pulver et al., 1985; Abaidoo et al., 2000). These so-called promiscuous TGx soybean genotypes can fix more N2 than the strict nodulating varieties from North America due to their ability to form more effective symbiosis with indigenous Bradyrhizobium strains in African soils (Mpepereki et al., 2000). The TGx soybean varieties also seem to have the ability to attract diverse indigenous bradyrhizobia in African soils as shown by B. japonicum, B. diazoefficiens, and B. elkanii which were recently identified as the dominant strains nodulating soybean in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Mozambique (Jaiswal et al., 2016; Naamala et al., 2016; Chibeba et al., 2017; Gyogluu et al., 2018). B. elkanii is also reported to be the major microsymbiont nodulating soybean in Malawian and Kenyan soils (Herrmann et al., 2014; Parr, 2014). Jaiswal et al. (2016), Naamala et al. (2016), and Gyogluu et al. (2018) have similarly found B. elkanii and some native Bradyrhizobium species to be the dominant symbionts species nodulating soybean in South Africa, Mozambique and Ethiopia. Geographically speaking, an earlier study by Abaidoo et al. (2000) also indicated that B. elkanii and B. japonicum were the most dominant bacterial symbionts isolated from root nodules of soybean in Benin, Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Togo, and Uganda. Taken together, these findings from the various studies confirm the nodulation of soybean by a diverse group of bradyrhizobia, but with B. elkanii and B. japonicum being very dominant.

Poor yield of soybean when it was first introduced into new areas outside Southeast Asia, (its center of origin and domestication) was attributed to the lack of co-evolved rhizobial strains in those soils (Pulver et al., 1985; Maingi et al., 2006; Abaidoo et al., 2007; Li et al., 2010; Chianu et al., 2011; Parr, 2014; Jaiswal et al., 2016). As a result, inoculation of soybean with exotic rhizobia has been the practice when soybean is introduced into new regions. Even with the TGx soybean genotypes which can nodulate freely with indigenous rhizobia, there are instances where native strains are either ineffective or low in numbers, suggesting soybean must still be inoculated with effective strains, whether indigenous or exotic (Sanginga et al., 2000; Giller, 2001; Okogun and Sanginga, 2003; Osunde et al., 2003; Abaidoo et al., 2007; Klogo et al., 2015). Inoculation is recommended in virgin soils when there are less than 10 cells of indigenous rhizobia per gram of soil (Thies et al., 1991, 1992; Sanginga et al., 1996; Sessitsch et al., 2002; Okogun and Sanginga, 2003). A number of studies have indicated the presence of highly effective native rhizobia in African soils that can be used as inoculants for increased soybean production (Abaidoo et al., 2000, 2007; Sanginga et al., 2000; Musiyiwa et al., 2005; Tefera, 2011; Youseif et al., 2014; Klogo et al., 2015; Gyogluu et al., 2016; Chibeba et al., 2017).

Groundnut Nodulation by Diverse Rhizobial Populations in Africa

Though native to South America, groundnut is an important grain legume in Africa (Hammons, 1982), brought by Spanish and Portuguese explorers on their voyages to Africa. Due to its ability to fix N2, groundnut has become a significant component of traditional cropping systems. The amount of N-fixed by groundnut can vary hugely depending on the genotype (Mokgehle et al., 2014) and the efficacy of the rhizobial strains involved in the symbiosis (Paffetti et al., 1998). In general, however, groundnut is known to have high N2-fixing capacity as it can obtain about 88–93% of its N nutrition from BNF and contribute up to 206 kg N ha-1 in cropping systems (Boddey et al., 1990; Peoples et al., 1991; Toomsan et al., 1995; Hoa et al., 2002; Osei et al., 2018). Estimates of N contribution by groundnut was up to 188 kg N ha-1 in South Africa (Mokgehle et al., 2014), 58–101 kg N ha-1 in Ghana (Konlan et al., 2013), and 19–79 kg N ha-1 in Zambia (Nyemba and Dakora, 2010). Despite the agronomic importance of groundnut, studies of its microsymbionts are relatively few, and cover only four African countries, namely Cameroon (Ngo Nkot et al., 2008), Morocco (El-Akhal et al., 2008), Ghana (Osei et al., 2018), and South Africa (Law et al., 2007; Steenkamp et al., 2008; Jaiswal et al., 2017).

Whether because nodule formation in groundnut is by crack entry and infection thread invasion (Tajima et al., 2008), groundnut-nodulating symbionts tend to reveal high levels of diversity and heterogeneity when obtained from different regions of Africa. This heterogeneity could be due to the high level of promiscuity reported for groundnut nodulation (Nievas et al., 2012; Jaiswal et al., 2017; Osei et al., 2018) as it can form effective symbiosis with both slow- and fast-growing bacteria belonging to the genera Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium in African soils (Taurian et al., 2006; El-Akhal et al., 2008; de Freitas and Silva, 2013; Jaiswal et al., 2017; Osei et al., 2018). The fast-growing rhizobia that are reported to effectively nodulate groundnut in African soils, include R. giardinii and R. tropici (Taurian et al., 2006; Jaiswal et al., 2017; Osei et al., 2018).

Based on ribosomal and symbiotic gene sequence analyses, B. yuanmingense and R. tropici were identified as the microsymbionts nodulating groundnut in Ghanaian soils (Osei et al., 2018). In South Africa, however, Jaiswal et al. (2017) also reported the presence of a huge diversity of bacteria nodulating groundnut, based on ITS-RFLP, core and symbiotic gene sequence analyses, with Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium as the major dominants of groundnut nodulation. Of the latter, B. pachyrhizi and novel Bradyrhizobium species close to B. guangdongense and B. diazoefficiens were responsible for groundnut nodulation, while of the Rhizobium group, R. tropici and other novel Rhizobium species also contributed to groundnut nodulation. Clearly, the taxonomic position of rhizobia nodulating groundnut is still not well defined. These results, however, do suggest that chromosomal and symbiotic genes could have the same evolutionary history.

Nodulation of Wild Legumes by Diverse Bradyrhizobia in Africa

Besides the nodulation of economically important grain legumes, Bradyrhizobium species are also associated with the nodulation of wild legumes in African soils. For example, diverse photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic bradyrhizobia with distinct host-ranges have been reported in the nodulation of Aeschynomene species in Senegal (Nzoué et al., 2009; Molouba et al., 1999). In Senegal, effective diverse Bradyrhizobium sp. found in deep soil could nodulate Acacia albida (Dupuy and Dreyfus, 1992; Dupuy et al., 1994). The soils of the sudanean and Sahelian regions of Senegal harbor B. elkanii and B. japonicum as the nodulating species of the wild legumes Pterocarpus erinaceus and Pterocarpus lucens (Sylla et al., 2002). Based on amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), 16S–23S rRNA, SDS-PAGE and 16S rRNA-RFLP, diverse Bradyrhizobium sp. nodulating various wild legume genera (Abrus, Alysicarpus, Bryaspis, Chamaecrista, Cassia, Crotalaria, Desmodium, Eriosema, Indigofera, Moghania, Rhynchosia, Sesbania, Tephrosia, and Zornia) have been identified in the arid regions of Senegal (West Africa) (Doignon-Bourcier et al., 1999, 2000). Furthermore, microsymbionts isolated from Zornia glochidiata in the degraded semi-arid soils of the Sahelian ecosystem were identified as B. liaoningense, B. yuanmingense and B. japonicum based on 16S–23S rRNA and recA gene sequence analysis (Gueye et al., 2009).

The Cape Floristic region is largely semi-arid with nutrient-poor, acidic soils (Witkowski and Mitchell, 1987; Manning and Goldblatt, 2012) that is home to many endemic papilionoid tribes such as Crotalarieae, Podalyrieae, Psoraleeae, and Indigofereae (Goldblatt and Manning, 2002; Linder, 2003; Manning and Goldblatt, 2012), which play an important ecological role in providing symbiotic N to the ecosystem (Sprent, 2009; Sprent et al., 2010, 2013). Interestingly, the nodulation of some fynbos legumes is by Bradyrhizobium species. Recently, Lemaire et al. (2015) identified diverse populations of Bradyrhizobium as the microsymbionts of Cape legumes. B. canariense, which is highly acid-tolerant (Vinuesa et al., 2005), was isolated from Indigofera gracilis, and B. elkanii from Indigofera frutescens and Tephrosia capensis in the Cape fynbos of South Africa.

Bradyrhizobium nodulation has been reported for Argyrolobium rupestre and Argyrolobium sericeum from the Genisteae tribe, Leobordea pulchra, L. divaricate, L. lanceolate, and Pearsonia obovate from the Crotalarieae tribe, as well as Chamaecrista from the Cassieae tribe (Beukes et al., 2016), which have their centers of divergence in Southern Africa (Polhill and VanWyk, 2005). However, this diverse group of Bradyrhizobium were closely related to six novel species without alignment to known reference strains. This suggests the widespread nodulation of legumes in Africa by Bradyrhizobium species.

Furthermore, a phylogenetically diverse group of Bradyrhizobium genospecies were also found to be the microsymbionts nodulating Crotalaria, Indigofera, and Erythrina brucei in Ethiopia (Aserse et al., 2012). In another study, diverse Bradyrhizobium species were the natural microsymbionts of the tree legumes Acacia saligna, Faidherbia albida, Erythrina brucei, Millettia ferruginea, and Albizia gummifera sampled from dry, hot, semi-arid to moist cold contrasting environments in Ethiopia (Wolde-meskel et al., 2004). In an earlier report, Faidherbia albida was the most frequently used host for trapping Bradyrhizobium in Africa (Odee et al., 2002). Multilocus sequence analysis later confirmed that B. huanghuaihaiense, B. yuanmingense, B. pachyrhizi and some novel Bradyrhizobium species were the natural bacterial symbionts of Faidherbia albida, Acacia saligna, Erythrina brucei, Albizia gummifera, and Millettia ferruginea in Ethiopian soils (Degefu et al., 2017). Analysis of chromosomal (glnII, recA, gyrB, and dnaK) and symbiotic (nodA, nodC, nifD, and nifH) genes of Bradyrhizobium obtained from wild African legumes suggested their separate evolutionary history, and that the symbiotic genes were likely to be of African origin (Beukes et al., 2016; Degefu et al., 2017).

A diverse group of Bradyrhizobium species close to B. canariense, B. cytisi, B. rifense, B. japonicum, and B. elkanii were found to nodulate Lupinus micranthus in Africa, however, multilocus sequence analysis and nodC phylogeny defined them as symbiovar genistearum (Bourebaba et al., 2016). In Algeria, B. algeriense could also nodulate Retama raetam, Lupinus micranthus, Lupinus albus, and Genista numidica, but not Lupinus angustifolius or Glycine max (Ahnia et al., 2018). In an earlier report, B. canariense isolated in Spain showed the ability to nodulate serradella and Lupinus cosentinii in South Africa (Stȩpkowski et al., 2005).

Factors Influencing Bradyrhizobium Distribution in African Soils

Many factors are known to influence bacterial distribution in soils, which include the presence of legume host, and environmental conditions such as soil factors (Keyser and Li, 1992; Wani et al., 1995; Dakora and Keya, 1997; Paffetti et al., 1998; Zahran, 1999; Peoples et al., 2009; Abi-Ghanem et al., 2013; Vitousek et al., 2013; Puozaa et al., 2017). These factors can affect all aspects of legume nodulation and N2 fixation which include a decrease in rhizobial survival and diversity in soils as well as their direct effect on nitrogenase activity (Serraj, 2004). Native rhizobia and bradyrhizobia easily develop adaptive mechanisms for surviving stress (Dakora, 2012), with the latter generally exhibiting better resistance than the former. So far, 52 Bradyrhizobium symbionts have been identified globally for their ability to nodulate the legume plants (Table 1). Of these, only ten (B. algerianse, B. cytisi, B. kavangense, B. namibiense, B. subterraneum, B. retamae, B. rifense, B. ripae, B. vignae, and B. shewense) have an African origin with an ability to tolerate acidic to alkaline conditions (pH 4–9) (Chahboune et al., 2011; Chahboune et al., 2012; Guerrouj et al., 2013; Grönemeyer et al., 2015a,b, 2016, 2017; Ahnia et al., 2018; Bünger et al., 2018) (see Table 1). It therefore appears that the physico-chemical properties of soils play an important role in influencing the diversity of bradyrhizobial community in a niche (Jaiswal et al., 2016; Ojha et al., 2017; Puozaa et al., 2017; Rathi et al., 2018).

Rhizobial strains often perform poorly when introduced into new habitats, thus implying that their symbiotic effectiveness is often adapted to environmental factors of their local niche such as soil temperature (Roughley, 1970; Zhang et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2014), soil pH (Botha et al., 2004; Temprano-Vera et al., 2018), soil texture (Law et al., 2007), and host-plant type (Pule-Meulenberg et al., 2010; Jaiswal et al., 2016;Puozaa et al., 2017).

Low soil pH is for example an abiotic stress that can affect growth of the legume host, the microsymbiont, and their interaction due to high concentrations of protons that have direct or indirect effects such as forming toxic trivalent ions with aluminum, and/or reducing the availability of nutritionally and symbiotically important minerals such as Ca, Mg, P, and Mo (Indrasumunar et al., 2011; Dakora, 2012; Jaiswal et al., 2018). A recent study has shown that the occurrence and abundance of diverse cowpea rhizobial populations in Kenya was influenced by soil pH (Ndungu et al., 2018), which typically affects the availability of endogenous mineral nutrients in soils.

It is believed that the host plays a dominant role in shaping the choice of bacterial symbionts for the symbiosis (Hollowell et al., 2016). Consistent with this argument, Puozaa et al. (2017) found that when seeds with different seed coat pigmentations were planted in the same hole, they attracted different bradyrhizobial genotypes. This clearly supports the view that each host plant selects specific effective bacterial symbionts over those that are less effective for its nodulation. If so, it remains to be assessed why highly effective introduced strains fail to outcompete less effective native rhizobia.

Furthermore, the results of Puozaa et al. (2017) showed that Bambara groundnut nodulation was associated with much highly diverse bradyrhizobial populations in the drier Morwe region of South Africa (where rainfall was very low) when compared to the moist Ghanaian soils. These results are consistent with the finding that more diverse bradyrhizobial populations were found in soils from the drier or less-humid environments of Africa relative to wetter regions (Law et al., 2007; Krasova-Wade et al., 2003; Grönemeyer et al., 2014).

Besides soil moisture, Mohammed et al. (2018) also reported recently that soil mineral nutrients can influence the distribution of bradyrhizobia nodulating cowpea in the soils of South Africa and Ghana. Here, the South African bacterial symbionts were highly influenced by the endogenous soil concentrations of N, P, and Na, in contrast to Ghana, where B, Mn, and Fe had a major influence in the distribution of soil bradyrhizobia.

Current Challenges and Future Directions of Legume Root Nodulation in African Soils

The data collected here have strongly contributed to the growing body of knowledge on the size and efficacy of Bradyrhizobium populations in African soils, as well as our understanding of the evolution of this important group of microsymbionts. Africa could be a hotspot of bradyrhizobial biodiversity, a view that compels us to search for more novel bradyrhizobia in African soils in order to learn more about their biogeography. The presence of B. yuanmingense and B. elkanii in almost all the African soils studied probably suggest that strains of these species may be the most widely distributed in African soils.

Whether bradyrhizobial distribution in Africa suggests sympatric or allopatric speciation, remains to be assessed. However, it is interesting that many highly specialized endemic novel Bradyrhizobium species have been identified, while others present in the same niche, microclimate, and edaphic conditions, and suspected to be novel species remain to be delineated through systematic studies. That the rhizosphere environment and the host plant play a major role in the selection of the bacterial symbiont probably explains why only highly adapted indigenous bradyrhizobia often overcome introduced inoculant strains for root nodulation in legumes. So far, very few countries have been explored for the biogeography of Bradyrhizobium in African soils. Studies of different regions for new rhizobia and legume germplasm could lead to the discovery of novel microsymbionts that would support agricultural productivity in the continent.

Author Contributions

SJ collected the references and wrote this manuscript. FD critically reviewed and revised the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the South African Research Chair in Agrochemurgy and Plant Symbioses, the National Research Foundation, and the Tshwane University of Technology for financial support.

References

- Abaidoo R. C., Keyser H. H., Singleton P. W., Borthakur D. (2000). Bradyrhizobium spp.(TGx) isolates nodulating the new soybean cultivars in Africa are diverse and distinct from bradyrhizobia that nodulate North American soybeans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 225–234. 10.1099/00207713-50-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abaidoo R. C., Keyser H. H., Singleton P. W., Dashiell K. E., Sanginga N. (2007). Population size, distribution, and symbiotic characteristics of indigenous Bradyrhizobium spp. that nodulate TGx soybean genotypes in Africa. Appl. Soil Ecol. 35 57–67. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2006.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abate T., Alene A. D., Bergvinson D., Shiferaw B., Silim S., Orr A., et al. (2012). Tropical Grain Legumes in Africa and South Asia: knowledge and Opportunities. Patancheru: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Ghanem R., Bodah E., Wood M., Braunwart K. (2013). Potential breeding for high nitrogen fixation in Pisum sativum L: germplasm phenotypic characterization and genetic investigation. Am. J. Plant Sci. 4:1597 10.4236/ajps.2013.48193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnia H., Bourebaba Y., Durán D., Boulila F., Palacios J. M., Rey L., et al. (2018). Bradyrhizobium algeriense sp. nov., a novel species isolated from effective nodules of Retama sphaerocarpa from Northeastern Algeria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 41 333–339. 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akibode C. S. (2011). Trends in the Production, Trade, and Consumption of Food Legume Crops in Sub-Saharan Africa. M. Sc. thesis, Michigan State University; East Lansing, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Appunu C., Angele N., Laguerre G. (2008). Genetic diversity of native bradyrhizobia isolated from soybeans (Glycine max L.) in different agricultural-ecological-climatic regions of India. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 5991–5996. 10.1128/AEM.01320-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo J., Flores-Félix J. D., Igual J. M., Peix A., González-Andrés F., Díaz-Alcántara C. A., et al. (2017). Bradyrhizobium cajani sp. nov. isolated from nodules of Cajanus cajan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 2236–2241. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aserse A. A., Rasanen L. A., Aseffa F., Hailemariam A., Lindstrom K. (2012). Phylogenetically diverse groups of Bradyrhizobium isolated from nodules of Crotalaria spp., Indigofera spp., Erythrina brucei and Glycine max growing in Ethiopia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 65 595–609. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aserse A. A., Woyke T., Kyrpides N. C., Whitman W. B., Lindström K. (2017). Draft genome sequences of Bradyrhizobium shewense sp. nov. ERR11T and Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T. Stand. Genomic Sci. 12:74. 10.1186/s40793-017-0283-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aticho A., Elias E., Diels J. (2011). Comparative analysis of soil nutrient balance at farm level: a case study in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Soil Sci. 6 259–266. 10.3923/ijss.2011.259.266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belane A. K., Dakora F. D. (2010). Symbiotic N2 fixation in 30 field-grown cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) genotypes in the Upper West Region of Ghana measured using 15N natural abundance. Biol. Fertil. Soils 46 191–198. 10.1007/s00374-009-0415-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes C. W., Stepkowski T., Venter S. N., Cłapa T., Phalane F. L., le Roux M. M., et al. (2016). Crotalarieae and Genisteae of the South African Great Escarpment are nodulated by novel Bradyrhizobium species with unique and diverse symbiotic loci. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 100 206–218. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes C. W., Venter S. N., Law I. J., Phalane F. L., Steenkamp E. T. (2013). South African papilionoid legumes are nodulated by diverse Burkholderia with unique nodulation and nitrogen-fixation loci. PLoS One 8:e68406. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr R., Snapp S., Chirwa M., Shumba L., Msachi R. (2007). Participatory research on legume diversification with Malawian smallholder farmers for improved human nutrition and soil fertility. Exp. Agric. 43 437–453. 10.1017/S0014479707005339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boddey R. M., Urquiaga S., Neves M. C. P., Peres J. (1990). Quantification of the contribution of N2 fixation to field-grown grain legumes—a strategy for the practical application of the 15N isotope dilution technique. Soil Biol. Biochem. 22 649–655. 10.1016/0038-0717(90)90011-N [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botha W. J., Jaftha J. B., Bloem J. F., Habig J. H., Law I. J. (2004). Effect of soil bradyrhizobia on the success of soybean inoculant strain CB 1809. Microbiol. Res. 159 219–231. 10.1016/j.micres.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourebaba Y., Durán D., Boulila F., Ahnia H., Boulila A., Temprano F., et al. (2016). Diversity of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating Lupinus micranthus on both sides of the Western Mediterranean: Algeria and Spain. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 39 266–274. 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünger W., Grönemeyer J. L., Sarkar A., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2018). Bradyrhizobium ripae sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing symbiont isolated from nodules of wild legumes in Namibia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68 3688–3695. 10.1099/ijsem.0.002955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-Mellado J., Martinez-Romero E. (1996). Rhizobium phylogenies and bacterial genetic diversity. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 15 113–140. 10.1080/07352689.1996.10393183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chahboune R., Carro L., Peix A., Barrijal S., Velázquez E., Bedmar E. J. (2011). Bradyrhizobium cytisi sp. nov. isolated from effective nodules of Cytisus villosusin Morocco. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61 2922–2927. 10.1099/ijs.0.027649-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahboune R., Carro L., Peix A., Ramírez-Bahena M. H., Barrijal S. (2012). Bradyrhizobium rifense sp. nov. isolated from effective nodules of Cytisus villosus grown in the Moroccan Rif. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 35 302–305. 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. L., Wang J. Y., Wang E. T., Liu H. C., Sui X. H., Chen W. X. (2011). Bradyrhizobium lablabi sp. nov., isolated from effective nodules of Lablab purpureus and Arachis hypogaea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61 2496–2502. 10.1099/ijs.0.027110-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chianu J. N., Nkonya E. M., Mairura F. S., Chianu J. N., Akinnifesi F. K. (2011). Biological nitrogen fixation and socioeconomic factors for legume production in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Agron. Sustain. Develop. 31 139–154. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibeba A. M., Kyei-Boahen S., de Fátima Guimarães M., Nogueira M. A., Hungria M. (2017). Isolation, characterization and selection of indigenous Bradyrhizobium strains with outstanding symbiotic performance to increase soybean yields in Mozambique. Agri. Ecosyst. Environ. 246 291–305. 10.1016/j.agee.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidebe I. N., Jaiswal S. K., Dakora F. D. (2018). Distribution and phylogeny of microsymbionts associated with cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) nodulation in three agroecological regions of Mozambique. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84 1–25. 10.1128/AEM.01712-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E. M., Nóbrega R. S. A., Carvalho F., Trochmann A., Ferreira L. V. M., Moreira F. M. S. (2013). Plant growth promotion and genetic diversity of bacteria isolated from cowpea nodules. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 48 1275–1284. 10.1590/S0100-204X2013000900012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crews T. E., Peoples M. B. (2004). Legume versus fertilizer sources of nitrogen: ecological trade-offs and human needs. Agri. Ecosyst. Environ. 102 279–297. 10.1016/j.agee.2003.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa E. M., Guimarães A. A., de Carvalho T. S., Rodrigues T. L., de Almeida Ribeiro P. R., Lebbe L., et al. (2018). Bradyrhizobium forestalis sp. nov., an efficient nitrogen-fixing bacterium isolated from nodules of forest legume species in the Amazon. Arch. Microbiol. 200 743–752. 10.1007/s00203-018-1486-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa E. M., Guimarães A. A., Vicentin R. P., de Almeida Ribeiro P. R., Leão A. C. R., Balsanelli E., et al. (2017). Bradyrhizobium brasilense sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium isolated from Brazilian tropical soils. Arch. Microbiol. 199 1211–1221. 10.1007/s00203-017-1390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva K., De Meyer S. E., Rouws L. F., Farias E. N., dos Santos M. A., O’Hara G., et al. (2014). Bradyrhizobium ingae sp. nov., isolated from effective nodules of Inga laurina grown in Cerrado soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64 3395–3401. 10.1099/ijs.0.063727-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakora F. D. (2012). Root-nodule bacteria isolated from native Amphithalea ericifolia and four indigenous Aspalathus species from the acidic soils of the South African fynbos are tolerant to very low pH. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11 3766–3772. [Google Scholar]

- Dakora F. D., Keya S. O. (1997). Contribution of legume nitrogen fixation to sustainable agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29 809–817. 10.1016/S0038-0717(96)00225-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas A. D. S., Silva T. A. (2013). Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of rhizobia isolated from nodules of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) grown in Brazilian Spodosols. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 12:2147 10.5897/AJB11.1574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Matos G. F., Zilli J. E., de Araújo J. L. S., Parma M. M., Melo I. S., Radl V., et al. (2017). Bradyrhizobium sacchari sp. nov., a legume nodulating bacterium isolated from sugarcane roots. Arch. Microbiol. 199 1251–1258. 10.1007/s00203-017-1398-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degefu T., Wolde-meskel E., Woliy K., Frostegård Å. (2017). Phylogenetically diverse groups of Bradyrhizobium isolated from nodules of tree and annual legume species growing in Ethiopia. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 40 205–214. 10.1016/j.syapm.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamuta J. R. M., Ribeiro R. A., Araújo J. L. S., Rouws L. F. M., Zilli J. É, Parma M. M.et al. (2016). Bradyrhizobium stylosanthis sp. nov., comprising nitrogen-fixing symbionts isolated from nodules of the tropical forage legume Stylosanthes spp. IJSEM 66 3078–3087. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamuta J. R. M., Ribeiro R. A., Ormeno-Orrillo E., Melo I. S., Martínez-Romero E., Hungria M. (2013). Polyphasic evidence supporting the reclassification of Bradyrhizobium japonicum group Ia strains as Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63 3342–3351. 10.1099/ijs.0.049130-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamuta J. R. M., Ribeiro R. A., Ormeño-Orrillo E., Parma M. M., Melo I. S., Martínez-Romero E., et al. (2015). Bradyrhizobium tropiciagri sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium embrapense sp. nov., nitrogen-fixing symbionts of tropical forage legumes. IJSEM 65 4424–4433. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doignon-Bourcier F., Sy A., Willems A., Torck U., Dreyfus B., Gillis M., et al. (1999). Diversity of bradyrhizobia from 27 tropical Leguminosae species native of Senegal. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22 647–661. 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80018-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doignon-Bourcier F., Willems A., Coopman R., Laguerre G., Gillis M., de Lajudie P. (2000). Genotypic characterization of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating small Senegalese legumes by 16S-23S rRNA intergenic gene spacers and amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprint analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 3987–3997. 10.1128/AEM.66.9.3987-3997.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doku E. V. (1995). “Country report on Ghana,” in Conservation and Improvement of Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc eds Heller B., Mushonga J. (Harare: Department of Research & Specialist Services; ). [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy N., Willems A., Pot B., Dewettinck D., Vandenbruaene I., Maestrojuan G., et al. (1994). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bradyrhizobia nodulating the leguminous tree Acacia albida. IJSEM 44 461–473. 10.1099/00207713-44-3-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy N. C., Dreyfus B. L. (1992). Bradyrhizobium populations occur in deep soil under the leguminous tree Acacia albida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58 2415–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán D., Rey L., Mayo J., Zúñiga-Dávila D., Imperial J., Ruiz-Argüeso T., et al. (2014a). Bradyrhizobium paxllaeri sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium icense sp. nov., nitrogen-fixing rhizobial symbionts of Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) in Peru. IJSEM 64 2072–2078. 10.1099/ijs.0.060426-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durán D., Rey L., Navarro A., Busquets A., Imperial J., Ruiz-Argüeso T. (2014b). Bradyrhizobium valentinum sp. nov., isolated from effective nodules of Lupinus mariae-josephae, a lupine endemic of basic-lime soils in Eastern Spain. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 37 336–341. 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Akhal M. R., Rincón A., Arenal F., Lucas M. M., El Mourabit N., Barrijal S., et al. (2008). Genetic diversity and symbiotic efficiency of rhizobial isolates obtained from nodules of Arachis hypogaea in north western Morocco. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40 2911–2914. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. R., von Caemmerer S. (2011). Enhancing photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 155:19. 10.1104/pp.110.900402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giller K. E. (2001). Nitrogen Fixation in Tropical Cropping Systems. Wallingford, CT: CABI Publishing; 10.1079/9780851994178.0000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt P., Manning J. C. (2002). Plant diversity of the Cape region of southern Africa. Ann. Mol. Bot. Gard. 89 281–302. 10.2307/3298566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer J. L., Bünger W., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2017). Bradyrhizobium namibiense sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium from root nodules of Lablab purpureus, hyacinth bean, in Namibia. IJSEM 67 4884–4891. 10.1099/ijsem.0.002039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer J. L., Chimwamurombe P., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2015a). Bradyrhizobium subterraneum sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium from root nodules of groundnuts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 3241–3247. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer J. L., Hurek T., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2015b). Bradyrhizobium kavangense sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium from root nodules of traditional Namibian pulses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 4886–4894. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer J. L., Hurek T., Bünger W., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2016). Bradyrhizobium vignae sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing symbiont isolated from effective nodules of Vigna and Arachis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 62–69. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer J. L., Kulkarni A., Berkelmann D., Hurek T., Reinhold-Hurek B. (2014). Rhizobia indigenous to the Okavango region in Sub-Saharan Africa: diversity, adaptations, and host specificity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 7244–7257. 10.1128/AEM.02417-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrouj K., Ruíz-Díez B., Chahboune R., Ramírez-Bahena M. H., Abdel-moumen H., Quiñones M. A., et al. (2013). Definition of a novel symbiovar (sv. retamae) within Bradyrhizobium retamae sp. nov., nodulating Retama sphaerocarpa and Retama monosperma. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 36 218–223. 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueye F., Moulin L., Sylla S., Ndoye I., Béna G. (2009). Genetic diversity and distribution of Bradyrhizobium and Azorhizobium strains associated with the herb legume Zornia glochidiata sampled from across Senegal. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32 387–399. 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueye M., Bordeleau L. M. (1988). Nitrogen fixation in Bambara groundnut, Voandzeia subterranea (L.) Thouars. Mircen. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4 365–375. 10.1007/BF01096142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães A. A., Jaramillo P. M. D., Nóbrega R. S. A., Florentino L. A., Silva K. B., Moreira F. M. S. (2012). Genetic and symbiotic diversity of nitrogen-fixing bacteria isolated from agricultural soils in the western Amazon by using cowpea as the trap plant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 6726–6733. 10.1128/AEM.01303-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyogluu C., Boahen S. K., Dakora F. D. (2016). Response of promiscuous-nodulating soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) genotypes to Bradyrhizobium inoculation at three field sites in Mozambique. Symbiosis 69 81–88. 10.1007/s13199-015-0376-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gyogluu C., Mohammed M., Jaiswal S. K., Kyei-Boahen S., Dakora F. D. (2018). Assessing host range, symbiotic effectiveness, and photosynthetic rates induced by native soybean rhizobia isolated from Mozambican and South African soils. Symbiosis 75 257–266. 10.1007/s13199-017-0520-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammons R. O. (1982). “Origin and early history of peanut,” in Peanut Science and Technology eds Pattee H. E., Young C. T. (Yoakum, TX: American Peanut Research and Education Society; ) 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hardarson G., Atkins C. (2003). Optimising biological N2 fixation by legumes in farming systems. Plant soil 252 41–54. 10.1023/A:1024103818971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helene L. C. F., Delamuta J. R. M., Ribeiro R. A., Hungria M. (2017). Bradyrhizobium mercantei sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing symbiont isolated from nodules of Deguelia costata (syn. Lonchocarpus costatus). IJSEM 67 1827–1834. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helene L. C. F., Delamuta J. R. M., Ribeiro R. A., Ormeño-Orrillo E., Rogel M. A., Martínez-Romero E., et al. (2015). Bradyrhizobium viridifuturi sp. nov., encompassing nitrogen-fixing symbionts of legumes used for green manure and environmental services. IJSEM 65 4441–4448. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann L., Chotte J. L., Thuita M., Lesueur D. (2014). Effects of cropping systems, maize residues application and N fertilization on promiscuous soybean yields and diversity of native rhizobia in Central Kenya. Pedobiology 57 75–85. 10.1016/j.pedobi.2013.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoa N. T. L., Thao T. Y., Lieu P., Herridge D. F. (2002). “N2 fixation of groundnut in the eastern region of south Vietnam,” in Inoculants and Nitrogen Fixation of Legumes in Vietnam ed. Herridge D. F. (Canberra: ACIAR; ) 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hollowell A. C., Regus J. U., Turissini D., Gano-Cohen K. A., Bantay R., Bernardo A., et al. (2016). Metapopulation dominance and genomic-island acquisition of Bradyrhizobium with superior catabolic capabilities. Proc. R. Soc. B 283:20160496. 10.1098/rspb.2016.0496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungria M., Vargas M. A. (2000). Environmental factors affecting N2 fixation in grain legumes in the tropics, with an emphasis on Brazil. Field Crops Res. 65 151–164. 10.1016/S0378-4290(99)00084-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Indrasumunar A., Dart P. J., Menzies N. W. (2011). Symbiotic effectiveness of Bradyrhizobium japonicum in acid soils can be predicted from their sensitivity to acid soil stress factors in acidic agar media. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43 2046–2052. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.05.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. S., Kawasaki H., Muramatsu Y., Nakagawa Y., Seki T. (2008). Bradyrhizobium iriomotense sp. nov., isolated from a tumor-like root of the legume Entada koshunensis from Iriomote Island in Japan. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 72 1416–1429. 10.1271/bbb.70739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S. K., Beyan S. M., Dakora F. D. (2016). Distribution, diversity and population composition of soybean-nodulating bradyrhizobia from different agro-climatic regions in Ethiopia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 52 725–738. 10.1007/s00374-016-1108-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S. K., Msimbira L. A., Dakora F. D. (2017). Phylogenetically diverse group of native bacterial symbionts isolated from root nodules of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in South Africa. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 40 215–226. 10.1016/j.syapm.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S. K., Naamala J., Dakora F. D. (2018). Nature and mechanisms of aluminium toxicity, tolerance and amelioration in symbiotic legumes and rhizobia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 54 309–318. 10.1007/s00374-018-1262-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo P. M. D., Guimarães A. A., Florentino L. A., Silva K. B., Nóbrega R. S. A., Moreira F. M. S. (2013). Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterial populations trapped from soils under agroforestry systems. Sci. Agric. 70 397–404. 10.1590/S0103-90162013000600004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan D. C. (1982). Transfer of Rhizobium japonicum Buchanan 1980 to Bradyrhizobium gen. nov., a genus of slow-growing, root nodule bacteria from leguminous plants. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 32 136–139. 10.1099/00207713-32-1-136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessy J. F., Nsokko E., Kaswamila A., Kimaro F. (2016). Analysis of drivers and agents of deforestation and forest degradation in Masito forests, Kigoma, Tanzania. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 6 93–107. 10.18488/journal.1/2016.6.2/1.2.93.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyser H. H., Li F. (1992). “Potential for increasing biological nitrogen fixation in soybean,” in Biological Nitrogen Fixation for Sustainable Agriculture eds Ladha J. K., George T., Bohlool C. (Berlin: Springer; ) 119–135. 10.1007/978-94-017-0910-1_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishinevsky B. D., Zur M., Friedman Y., Meromi G., Ben-Moshe E., Nemas C. (1996). Variation in nitrogen fixation and yield in landraces of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L.). Field Crops Res. 48 57–64. 10.1016/0378-4290(96)00037-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klogo P., Ofori J. K., Amaglo H. (2015). Soybean (Glycine max (L) Merill) promiscuity reaction to indigenous bradyrhizobia inoculation in some Ghanaian soils. Int. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 4 306–313. [Google Scholar]

- Konlan S., Sarkodies-Addo J., Asare E., Kombiok J. M. (2013). Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) varietal response to spacing in the Guinea Savanna agro-ecological zone of Ghana: nodulation and nitrogen fixation. Agric. Biol. J. North Am. 4 324–335. 10.5251/abjna.2013.4.3.324.335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krasova-Wade T., Ndoye I., Braconnier S., Sarr B., De Lajudie P., Neyra M. (2003). Diversity of indigeneous bradyrhizobia associated with three cowpea cultivars (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) grown under limited and favorable water conditions in Senegal (West Africa). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2 13–22. 10.5897/AJB2003.000-1003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaga F., Danso S. K., Zapata F. (1994). Time-course of nitrogen fixation in two Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc.) cultivars. Biol. Fertil. Soils 18 231–236. 10.1007/BF00647672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuykendall L. M., Saxena B., Devine T. E., Udell S. E. (1992). Genetic diversityin Bradyrhizobium japonicum Jordan, 1982 and aproposal for Bradyrhizobium elkanii sp. nov. Can. J. Microbiol. 38 501–505. 10.1139/m92-082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lal R., Stewart B. A. (2013). Principles of Sustainable Soil Management in Agroecosystems. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 10.1201/b14972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Law I. J., Botha W. J., Majaule U. C., Phalane F. L. (2007). Symbiotic and genomic diversity of ‘cowpea’ bradyrhizobia from soils in Botswana and South Africa. Biol. Fertil. Soils 43 653–663. 10.1007/s00374-006-0145-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire B., Van Cauwenberghe J., Chimphango S., Stirton C., Honnay O., Smets E., et al. (2015). Recombination and horizontal transfer of nodulation and ACC deaminase (acdS) genes within Alpha- and Beta-proteobacteria nodulating legumes of the Cape Fynbos biome. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91:fiv118. 10.1093/femsec/fiv118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Li W., Zhang C., Yang L., Chang R. Z., Gaut B. S., et al. (2010). Genetic diversity in domesticated soybean (Glycine max) and its wild progenitor (Glycine soja) for simple sequence repeat and single nucleotide polymorphism loci. New Phytol. 188 242–253. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Wang R., Zhang X. X., Young J. P. W., Wang E. T., Sui X. H., et al. (2015). Bradyrhizobium guangdongense sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium guangxiense sp. nov., isolated from effective nodules of peanut. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 4655–4661. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder H. P. (2003). The radiation of the Cape flora, southern Africa. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 78 597–638. 10.1017/S1464793103006171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. K., Dou Y. J., Zhu Y. J., Wang S. K., Sui X. H., Kang L. H. (2014). Bradyrhizobium ganzhouense sp. nov., an effective symbiotic bacterium isolated from Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. nodules. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64 1900–1905. 10.1099/ijs.0.056564-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingi J. M., Gitonga N. M., Shisanya C. A., Hornetz B., Muluvi G. M. (2006). Population levels of indigenous bradyrhizobia nodulating promiscuous soybean in two Kenyan soils of the semi-arid and semi-humid agroecological zones. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 107 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Manning J., Goldblatt P. (2012). Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mapope N., Dakora F. D. (2016). N2 fixation, carbon accumulation, and plant water relations in soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) varieties sampled from farmers’ fields in South Africa, measured using 15N and 13C natural abundance. Agri. Ecosys. Environ. 221 174–186. 10.1016/j.agee.2016.01.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michel D. C., Passos S. R., Simões-Araujo J. L., Baraúna A. C., da Silva K., Parma M. M., et al. (2017). Bradyrhizobium centrolobii and Bradyrhizobium macuxiense sp. nov. isolated from Centrolobium paraense grown in soil of Amazonia, Brazil. Arch. Microbiol. 199 657–664. 10.1007/s00203-017-1340-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohale K. C., Belane A. K., Dakora F. D. (2013). Symbiotic N nutrition, C assimilation, and plant water use efficiency in Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) grown in farmers’ fields in South Africa, measured using 15N and 13C natural abundance. Biol. Fertil. Soils 50 307–319. 10.1007/s00374-013-0841-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed M., Jaiswal S. K., Dakora F. D. (2018). Distribution and correlation between phylogeny and functional traits of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.)-nodulating microsymbionts from Ghana and South Africa. Sci. Rep. 8:18006. 10.1038/s41598-018-36324-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokgehle S. N., Dakora F. D., Mathews C. (2014). Variation in N2 fixation and N contribution by 25 groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) varieties grown in different agro-ecologies, measured using 15N natural abundance. Agri. Ecosyst. Environ. 195 161–172. 10.1016/j.agee.2014.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molouba F., Lorquin J., Willems A., Hoste B., Giraud E., Dreyfus B., et al. (1999). Photosynthetic bradyrhizobia from Aeschynomene spp. are specific to stem-nodulated species and form a separate 16S ribosomal DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 3084–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpepereki S., Javaheri F., Davis P., Giller K. E. (2000). Soyabeans and sustainable agriculture: promiscuous soyabeans in southern Africa. Field Crops Res. 65 137–149. 10.1016/S0378-4290(99)00083-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mpepereki S., Wollum A. G., Makonese F. (1996). Diversity in symbiotic specificity of cowpea rhizobia indigenous to Zimbabwean soils. Plant Soil 186 167–171. 10.1007/BF00035071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musiyiwa K., Mpepereki S., Giller K. E. (2005). Symbiotic effectiveness and host ranges of indigenous rhizobia nodulating promiscuous soyabean varieties in Zimbabwean soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37 1169–1176. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutegi J., Zingore S. I. (2014). Boosting Soybean Production for Improved Food Security and Incomes in Africa. Nairobi: The International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI). [Google Scholar]

- Naab J. B., Chimphango S. M., Dakora F. D. (2009). N2 fixation in cowpea plants grown in farmers’ fields in the Upper West Region of Ghana, measured using 15N natural abundance. Symbiosis 48 37–46. 10.1007/BF03179983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naamala J., Jaiswal S. K., Dakora F. D. (2016). Microsymbiont diversity and phylogeny of native bradyrhizobia associated with soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) nodulation in South African soils. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 39 336–344. 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ncube B., Twomlow S. J., van Wijk M. T., Dimes J. P., Giller K. E. (2007). Productivity and residual benefits of grain legumes to sorghum under semi-arid conditions in south western Zimbabwe. Plant Soil 299 1–15. 10.1007/s11104-007-9330-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ndungu S. M., Messmer M. M., Ziegler D., Gamper H. A., Mészáros É, Thuita M.et al. (2018). Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp) hosts several widespread bradyrhizobial root nodule symbionts across contrasting agro-ecological production areas in Kenya. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 261 161–171. 10.1016/j.agee.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo Nkot L., Krasova-Wade T., Etoa F. X., Sylla S. N., Nwaga D. (2008). Genetic diversity of rhizobia nodulating Arachis hypogaea L. in diverse land use systems of humid forest zone in Cameroon. Appl. Soil Ecol. 40 411–416. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nievas F., Bogino P., Nocelli N., Giordano W. (2012). Genotypic analysis of isolated peanut-nodulating rhizobial strains reveals differences among populations obtained from soils with different cropping histories. Appl. Soil Ecol. 53 74–82. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.11.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyemba R. C., Dakora F. D. (2010). Evaluating N2 fixation by food grain legumes in farmers’ fields in three agroecological zones of Zambia, using 15N natural abundance. Biol. Fertil. Soils 46 461–470. 10.1007/s00374-010-0451-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nzoué A., Miché L., Klonowska A., Laguerre G., de Lajudie P., Moulin L. (2009). Multilocus sequence analysis of bradyrhizobia isolated from Aeschynomene species in Senegal. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32 400–412. 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odee D. W., Haukka K., McInroy S. G., Sprent J. I., Sutherland J. M., Young J. P. W. (2002). Genetic and symbiotic characterization of rhizobia isolated from tree and herbaceous legumes grown in soils from ecologically diverse sites in Kenya. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34 801–811. 10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00009-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha A., Tak N., Rathi S., Chouhan B., Rao S. R., Barik S. K., et al. (2017). Molecular characterization of novel Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating Eriosema chinense and Flemingia vestita, Important unexplored native legumes of the Sub-Himalayan region (Meghalaya) of India. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 40 334–344. 10.1016/j.syapm.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okogun J., Sanginga N. (2003). Can introduced and indigenous rhizobial strains compete for nodule formation by promiscuous soybean in the moist savanna agroecological zone of Nigeria? Biol. Fertil. Soils 38 26–31. 10.1007/s00374-003-0611-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osei O., Abaidoo R. C., Ahiabor B. D., Boddey R. M., Rouws L. F. (2018). Bacteria related to Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense from Ghana are effective groundnut micro-symbionts. Appl. Soil Ecol. 127 41–50. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osunde A., Gwam S., Bala A., Sanginga N., Okogun J. (2003). Responses to rhizobial inoculation by two promiscuous soybean cultivars in soils of the Southern Guinea savanna zone of Nigeria. Biol. Fertil. Soils 37 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Paffetti D., Daguin F., Fancelli S., Gnocchi S., Lippi F., Scotti C., et al. (1998). Influence of plant genotype on the selection of nodulating Sinorhizobium meliloti strains by Medicago sativa. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 73 3–8. 10.1023/A:1000591719287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr M. (2014). Promiscuous Soybean: Impacts on Rhizobia Diversity and Smallholder Malawian Agriculture. Ph.D. thesis, North Carolina State University; Raleigh, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Peix A., Ramírez-Bahena M. H., Flores-Félix J. D., de la Vega P. A., Rivas R., Mateos P. F., et al. (2015). Revision of the taxonomic status of the species Rhizobium lupini and reclassification as Bradyrhizobium lupini comb. IJSEM 65 1213–1219. 10.1099/ijs.0.000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples M. B., Bergersen F. J., Turner G. L., Sampet C., Rerkasem B., Bhromsiri A., et al. (1991). “Use of the natural enrichment of 15N in plant available soil N for the measurement of symbiotic N2 fixation,” in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Stable Isotopes in Plant Nutrition, Soil Fertility and Environmental Studies (Vienna: FAO; ) 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Peoples M. B., Brockwell J., Herridge D. F., Rochester I. J., Alves B. J. R., Urquiaga S., et al. (2009). The contributions of nitrogen-fixing crop legumes to the productivity of agricultural systems. Symbiosis 48 1–17. 10.1007/BF03179980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polhill R. M., VanWyk B. E. (2005). “Genisteae,” in Legumes of the World eds Lewis G., Schrire B., Mackinder B., Lock M. (Richmond, VA: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; ) 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pule-Meulenberg F., Belane A. K., Krasova-Wade T., Dakora F. D. (2010). Symbiotic functioning and bradyrhizobial biodiversity of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) in Africa. BMC Microbiol. 10:89. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pule-Meulenberg F., Dakora F. D. (2009). Assessing the symbiotic dependency of grain and tree legumes on N2 fixation for their N nutrition in five agro-ecological zones of Botswana. Symbiosis 48 68–77. 10.1007/BF03179986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pulver E. L., Kueneman E. A., Ranga-Rao V. (1985). Identification of promiscuous nodulating soybean efficient in N2 fixation. Crop Sci. 25 660–663. 10.2135/cropsci1985.0011183X002500040019x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puozaa D. K., Jaiswal S. K., Dakora F. D. (2017). African origin of Bradyrhizobium populations nodulating Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) in Ghanaian and South African soils. PLoS One 12:e0184943. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Bahena M. H., Chahboune R., Peix A., Velázquez E. (2013). Reclassification of Agromonas oligotrophica into the genus Bradyrhizobium as Bradyrhizobium oligotrophicum comb. nov. IJSEM 63 1013–1016. 10.1099/ijs.0.041897-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Bahena M. H., Flores-Félix J. D., Chahboune R., Toro M., Velázquez E., Peix A. (2016). Bradyrhizobium centrosemae (symbiovar centrosemae) sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium americanum (symbiovar phaseolarum) sp. nov. and a new symbiovar (tropici) of Bradyrhizobium viridifuturi establish symbiosis with Centrosema species native to America. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 39 378–383. 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]