Abstract

Prolonged hypokalemia induces a decrease of urinary concentrating ability via down-regulation of aquaporin 2 (AQP2); however, the precise mechanisms remain unknown. To investigate the role of autophagy in the degradation of AQP2, we generated the principal cell-specific Atg7 deletion (Atg7Δpc) mice. In hypokalemic Atg7-floxed (Atg7f/f) mice, huge irregular shaped LC3-positive autophagic vacuoles accumulated mainly in inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells. Total- and pS261-AQP2 were redistributed from apical and subapical domains into these vacuoles, which were not co-localized with RAB9. However, in the IMCD cells of hypokalemic Atg7Δpc mice, these canonical autophagic vacuoles were markedly reduced, whereas numerous small regular shaped LC3-negative/RAB9-positive non-canonical autophagic vacuoles were observed along with diffusely distributed total- and pS261-AQP2 in the cytoplasm. The immunoreactivity of pS256-AQP2 in the apical membrane of IMCD cells was markedly decreased, and no redistribution was observed in both hypokalemic Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice. These findings suggest that AQP2 down regulation in hypokalemia was induced by reduced phosphorylation of AQP2, resulting in a reduction of apical plasma labeling of pS256-AQP2 and degradation of total- and pS261-AQP2 via an LC3/ATG7-dependent canonical autophagy pathway.

Introduction

Prolonged hypokalemia induces a vasopressin-resistant decrease of urinary concentration and polyuria, which is caused by down-regulation of the expression of aquaporin 2 (AQP2)1–4. AQP2 abundance is determined by the balance between its production by translation and its removal by degradation or exosomal excretion5,6. Although AQP2 degradation occurs via lysosomes or proteasomes, the precise mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain unknown. Recently, it has been suggested that arginine vasopressin-mediated phosphorylation can regulate AQP2 abundance7. Furthermore, the complexity of AQP2 regulation was revealed by the discovery that AQP2 can be phosphorylated at several sites. To date, 5 potential phosphorylation sites on the AQP2 C-terminus have been determined: Thr244, Ser256, Ser261, Ser264, and Ser2698–11. Phosphorylation of AQP2 at Ser256 (pS256-AQP2) and Ser261 (pS261-AQP2) may inversely regulate the endocytosis and exocytosis of AQP28,12–15. In particular, pS256-AQP2 is necessary for the regulated membrane accumulation of AQP2, which leads to increased water reabsorption and urinary concentration12,16–19. In contrast, pS261-AQP2 is proposed to stabilize AQP2 ubiquitination and intracellular localization and counterbalances pS256-AQP28,12,19.

Prolonged hypokalemia is a consequence of a common imbalance in potassium (K+) levels that can cause defects in urinary concentration ability, i.e., nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) in humans and experimental animals, including mice2,3,20–22. The collecting duct (CD) is the main nephron site where morphological alterations occur during K+ deficiency. Among the various morphological changes observed, the most remarkable is the accumulation of cytoplasmic droplets in collecting duct cells21,23,24 that are believed to represent lysosomal structures20,25 and are labeled by AQP22. However, even though these droplets are formed in a classical rodent model of hypokalemia induced by ingestion of K+ free diet for a period of 2 weeks, it is not certain whether they comprise autophagic vacuoles or are involved in AQP2 degradation.

Autophagy is a self-digesting process that is essential for the survival of eukaryotic cells, whereby unnecessary materials and dysfunctional organelles are sequestered and delivered into lysosomes for degradation26–28. Notably, this process represents a catabolic pathway utilized to maintain a balance among the synthesis, degradation, and recycling of cellular components, thereby playing a role in homeostasis27,29. However, until recently, the role of autophagy in kidney physiology has remained a largely understudied topic. The discovery of autophagy-related genes (ATGs) has greatly enhanced our understanding of the mechanisms of the autophagic pathway30–32. Formation of the autophagosome requires two unique ubiquitin-like protein conjugation systems: the ATG5-ATG12 pathway, and the LC3 pathway33. ATG7 acts as a catalyst in both conjugation systems and is therefore essential for autophagy34,35. This ATG7/ATG5/LC3-II-dependent pathway is called canonical (conventional) autophagy. In addition, an ATG7/ATG5/LC3-II-independent pathway termed noncanonical (alternative) autophagy has also recently been described36–41.

In this study, we examine the role of canonical or non-canonical autophagy in the degradation of AQP2, with particular focus on pS256- and pS261-AQP2 in induced prolonged hypokalemia. To this end, we generated conditional knockout mice in which ATG7 was genetically ablated specifically in AQP2-positive principal cells of the collecting duct. We restricted our observations to the IMCD cells that are main site of hypokalemia-associated morphological changes including the accumulation of cytoplasmic droplets.

Results

Principal cell-specific Atg7 deficiency mice exhibit enhanced polyuria and urinary concentration defects during hypokalemia

To address the role of autophagy in renal AQP2 homeostasis, we generated principal cell-specific Atg7-knockout (Atg7Δpc) mice by breeding Atg7-floxed mice (Atg7f/f) (kindly provided from Dr. Komatsu, Japan) with AQP2-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratories).

To study hypokalemia, mice were fed either normal diet or K+-free diet for 2 weeks. While on a normal diet, the serum K+ concentration was not significantly altered between Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice. Following 2 weeks of dietary K+ depletion, serum K+ and urinary K+excretion decreased on the K+-deficient diet in both Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice compared with control groups. Thus, 2 weeks of K+-free diet induced hypokalemia in both Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice.

After 2 weeks on reduced K+ diet, a significant increase in urine volume and a significant reduction in urine osmolality were observed in both hypokalemic Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice and these changes in the Atg7Δpc mice subsequently became pronounced compared with Atg7f/f mice. Even in the basal condition a significant increase in urine volume and a significant reduction in urine osmolality were observed in the Atg7Δpc mice compared to the Atg7f/f mice. These findings indicate that polyuria and enhanced urinary concentration are induced in K+ depleted Atg7f/f mice and that these changes in Atg7Δpc mice became pronounced.

Renal hypertrophy together with a urinary concentrating defect is normally considered hallmark of potassium depletion induced by restricting potassium intake1, therefore we analyzed kidney weights normalized for body weight for evidence of renal hypertrophy. Setting the Atg7f/f control group as 100%, a significant increase in kidney weight normalized for body weight was observed in Atg7Δpc mice maintained on a low K+ diet compared with knockout mice on a normal K+ diet, revealing a marked hypertrophy. Serum BUN levels were significantly decreased in Atg7Δpc mice maintained on a low K+ diet compared with those on a normal K+ diet, whereas no significant changes were not observed between low K+ diet group and normal K+ diet group in the Atg7f/f control mice. It may presumed that the markedly increased urine volume in Atg7Δpc mice maintained on a low K+ diet cause dehydration and subsequently contributed prerenal acute kidney injury. These chemical data were summarized at Supplementary Table S1.

Hypokalemia induces autophagy in the IMCD cells of Atg7f/f mice

To determine whether the cytoplasmic droplets in the CD induced by K+ depletion represent autophagic vacuoles, we monitored the kidney after 2 weeks of K+-free diet using immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry for LC3, as well as by ultrastructural analysis.

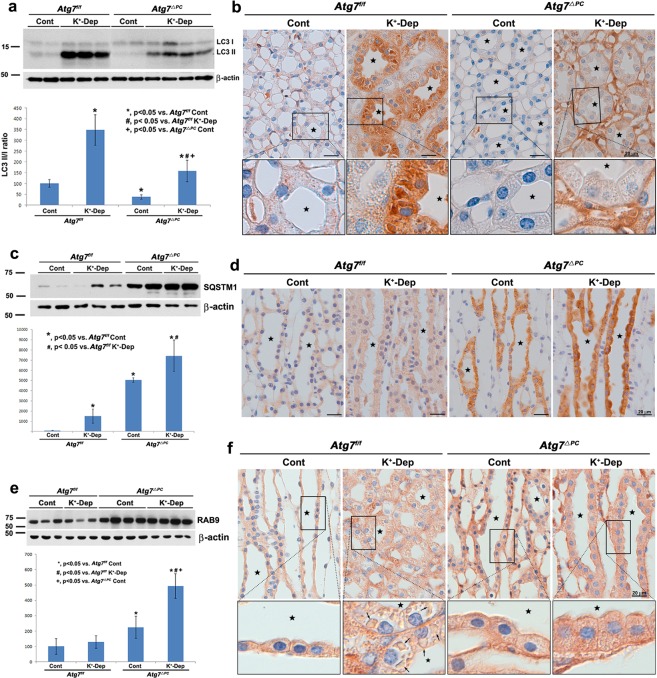

Immunoblotting of whole of renal inner medulla proteins showed that the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II was markedly increased in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 1a), whereas LC3 immunohistochemistry revealed small numbers of tiny LC3-positive droplets scattered throughout the cytoplasm in Atg7f/f mice fed a normal K+ diet (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S1a1′). Following 2 weeks of dietary K+ depletion in Atg7f/f mice, the most pronounced LC3-positive droplet accumulation occurred in AQP4-positive IMCD cells, wherein the LC3-positive droplets were large in size, irregular in shape, and often acquired gigantic proportions (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S1a2′). In contrast, although numerous cytoplasmic inclusions could be seen in the thin limb cells of Henle’s loop, the interstitial cells, and the endothelial cells of the papillary region, immunoreactivity for LC3 was only faintly observed in the majority of these inclusions (Supplementary Fig. S1a2′). In the cortex and the outer medulla, however, the LC3 II/I ratio was not significantly changed in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice and the LC3-positive droplet accumulation was relatively sparse in all structures including the cortical and outer medullary CDs. We confirmed same findings using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice (Supplementary Fig. S2). These findings indicate that hypokalemia induced autophagy restrictively in the renal papilla including in IMCD cells in Atg7f/f mice.

Figure 1.

Light micrographs of the inner medulla of control (Cont) and K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mouse kidneys illustrating immunoblotting (a,c,e) and immunolabeling (b,d,f) of LC3 (a,b), SQSTM1 (c,d) and RAB9 (e,f). (a) The degree of increase in the LC3 II/I ratio is significantly decreased in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc compare to K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice. (b) In the images, even in the control groups, immunoreactivity for LC3 in the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD, stars) cells are decreased in Atg7Δpc mice compare to Atg7f/f mice. After K+ depletion, immunoreactivity for LC3 in dramatically increased in the IMCD cells of Atg7f/f mice. However, immunoreactivity for LC3 is restrictively decreased in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice. Note that immunoreactivity for LC3 in other structures including interstitial cells and thin limb cells of Henle’s loop of renal papilla in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice is stronger in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice, but relatively weaker than that of IMCD cells in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice. (c) The protein level of SQSTM1 is significantly increased in Atg7Δpc compare to Atg7f/f mice. (d) In the images, strong immunoreactivity for SQSTM1 is observed restrictively in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice, which change is pronounced after K+ depletion. (e) Note the prominent increase of RAB9 in K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice. (f) Immunoreactivity for RAB9 is not observed in the autophagic vacuoles (arrows) of K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice. However, it is expressed in small autophagic vacuoles of K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice. Boxes in (b,f) are higher magnification of the areas indicated by the rectangles in upper panels. Values represent the means ± SD.

Non-canonical autophagy is activated in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice

In K+-depleted Atg7Δpc, western blot analyses revealed that the degree of LC3 II/I ratio increase was less than that of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 1a). Even in the normal diet groups, the LC3 II/I ratio and the immunoreactivity for LC3 in Atg7Δpc mice was decreased compare with those of Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 1a,b). Notably, in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, LC3-positive droplets in the IMCD cells were markedly decreased compare with those in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 1b). However, numerous LC3-negative cytoplasmic small round droplets of regular size were observed in these IMCD cells (Fig. 1b). In addition, in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, although immunoreactivity for LC3-II increased in the interstitial cells, endothelial cells, and thin limb cells of Henle’s loop, a marked decrease of immunoreactivity for LC3-II was observed restrictively in the IMCD cells (Fig. 1b).

Furthermore, p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) was significantly increased only in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice especially with K+-depletion for 2 weeks (Fig. 1c,d), suggesting that, in the renal papilla, autophagy was selectively inhibited in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice. These findings suggest that the increased autophagic vacuoles in Atg7Δpc mice after K+-depletion represent the autophagy generated in an Atg7-independent manner (ATG5/ATG7-independent non-canonical autophagy)36,37. To confirm these findings, we performed western blot analyses and immunohistochemistry for the RAB9, which is essential for membrane expansion and fusion in non-canonical autophagy36. The protein abundance of RAB9 was significantly increased in both control and K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice compared with Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 1e,f). These findings indicated that ATG7-independent non-canonical autophagy was induced restrictively in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice. Therefore, we restricted our subsequent ultrastructural observations to the IMCD cells, in which there was a marked alteration of LC3-positive autophagic vacuoles between Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice.

Ultrastructural characteristics of autophagic vacuoles induced by prolonged hypokalemia

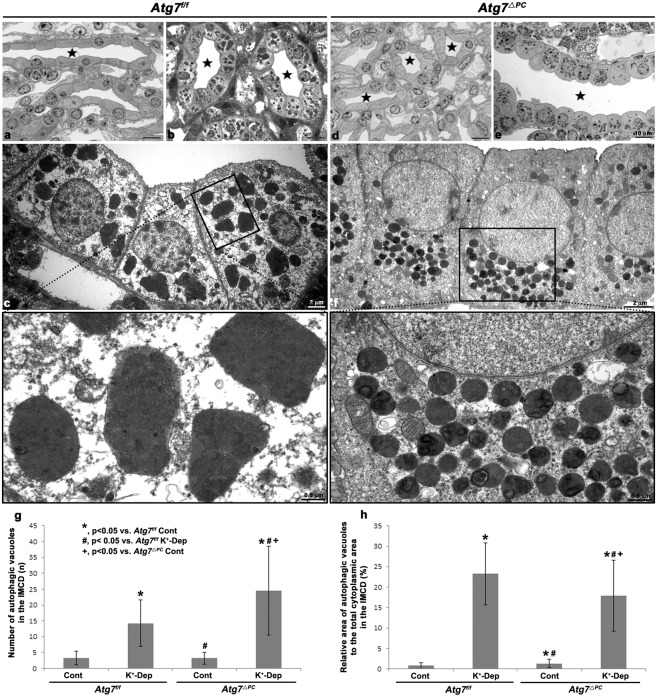

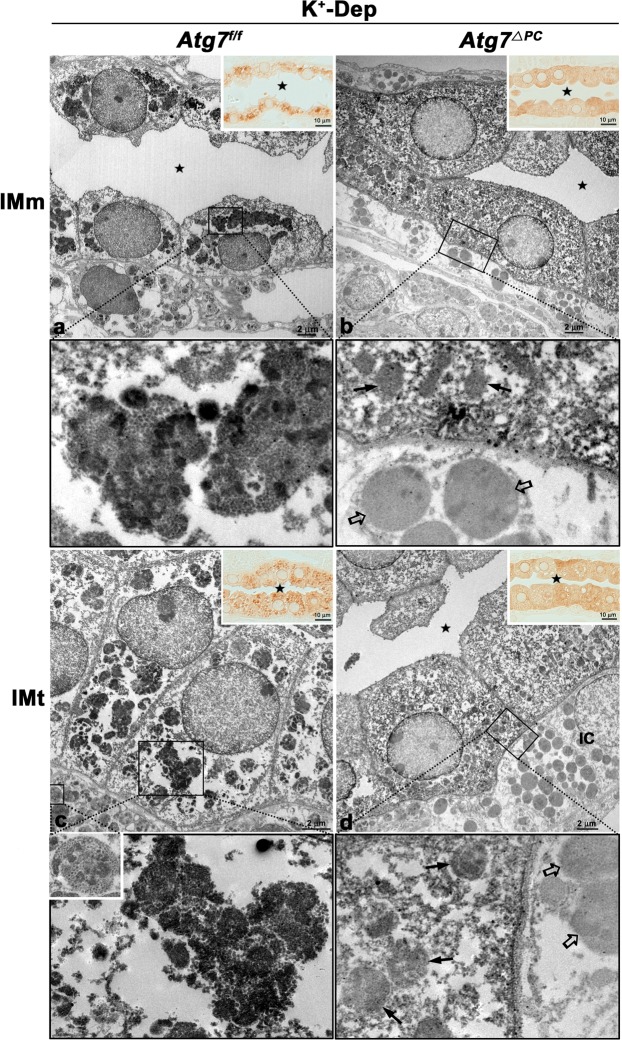

Electron microscopy revealed that the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice contained large irregular shaped autophagic vacuoles containing multilamellar bodies, small vesicles and granular inclusions (Fig. 2a–c). Notably, although no LC3-positive puncta were observed in the descending and ascending thin limb cells, the interstitial cells, and the endothelial cells of the papillary region of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice via light microscopic immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1b), we could observe many autophagic vacuoles in these structures (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Light (a,b,d,e) and transmission electron (c,f) micrographs of the inner medulla of control (a,d) (Cont) and K+-depleted (b,c,e,f) (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f (a–c) and Atg7Δpc (d–f) mouse kidneys. Stars indicate the lumen of the inner medullary collecting duct (a,b,d,e). The non-canonical autolysosomes in K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice are much greater in number (g) and smaller in size than those of canonical autophagic vacuoles in K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice. However, the relative area of autophagic vacuoles to the total cytoplasmic area is significantly decreased in K+-Dep Atg7Δpc compared to Atg7f/f mice (h).

Despite the disappearance of LC3-positive droplets in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice under light microscopic immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1b), ultrastructural analysis revealed numerous small, uniformed autophagic vacuoles with electron-dense materials (Fig. 2d–f). Furthermore, whereas the number of autophagic vacuoles was increased, the fractional area of the autophagic vacuoles was significantly decreased in Atg7Δpc mice compared with Atg7f/f mice after K+-depletion (Fig. 2g,h). These autophagic vacuoles in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice might comprise LC3-negative non-canonical autophagic vacuoles. In addition, in the cytoplasm of both control and K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice, cell organelles including Golgi complex and vesicles were sparse but polysomes were relatively well developed (Supplementary Fig. S4a–c). In contrast, in both control and K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, well developed Golgi complexes and small vesicles were observed in the IMCD cells (Supplementary Fig. S4d–f). Taken together, these data suggest that, in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice, LC3-positive canonical autophagy was induced. In contrast, LC3-negative non-canonical autophagy was induced in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice.

Alteration of distribution and amount of total-, pS261-, and pS256-AQP2

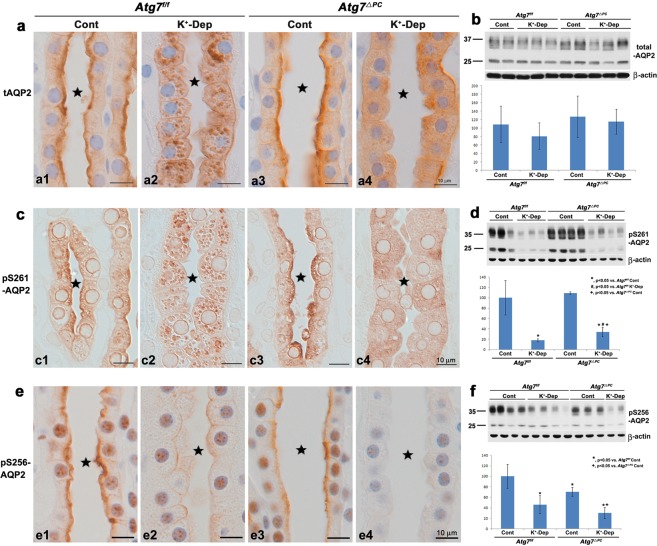

To investigate the effect of hypokalemia on the expression and distribution of AQP2, we performed western blot analyses and immunohistochemical staining for total-AQP2, pS256-AQP2, and pS261-AQP2 after K+-depletion for 2 weeks. Under basal conditions, immunohistochemical labeling revealed that total AQP2 was strongly labeled in the apical and partially in the subapical domains of the IMCD cells in both Atg7f/f (Fig. 3a1) and Atg7Δpc (Fig. 3a3) mice. After K+-depletion, the total-AQP2 redistributed mainly into the intracellular vesicles in Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 3a2) but redistributed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm in Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 3a4). On a normal diet, pS261-AQP2 was mainly labeled in the apical and partially in the subapical domains of the IMCD cells in both Atg7f/f (Fig. 3c1) and Atg7Δpc (Fig. 3c3) mice. After K+-depletion, pS261-AQP2 was located restrictively in the intracellular vesicles in Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 3c2) but diffusely throughout the cytoplasm in Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 3c4). On a normal diet, pS256-AQP2 was strongly labeled on the apical membrane of the IMCD cells in both Atg7f/f (Fig. 3e1) and Atg7Δpc (Fig. 3e3) mice. After K+-depletion, on the other hand, the immunoreactivity of pS256-AQP2 in the apical membrane was markedly decreased in both Atg7f/f (Fig. 3e2) and Atg7Δpc (Fig. 3e4) mice. Western blot analyses for lysates of the renal inner medulla revealed that the protein expression of pS261- and pS256-AQP2 was significantly decreased after K+-depletion compared with controls in both Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 3d,f). Densitometric quantitation revealed a decrease in expression of pS261- and pS256-AQP2 in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice to 17.63 ± 2.99% and 46.03 ± 17.24% of control levels, respectively. Furthermore, in Atg7Δpc mice fed normal diet, the protein expression of total- and pS261-AQP2 was slightly increased to 111.07 ± 50.74% and 109.30 ± 2.38% of control Atg7f/f mice, respectively. However, pS256-AQP2 was decreased to 70.45 ± 8.62% of control Atg7f/f mice. In K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, the rates of protein level decrease of total- and pS261-AQP2 were reduced compared to those of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice. In comparison, the decreased rate of pS256-AQP2 in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice was significantly pronounced compared to that of K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice. Taken together, these findings indicated that the down-regulation of AQP2 in hypokalemia was induced by a reduction of protein level, by redistribution of pS261-AQP2 into the intracellular vesicles, and by a reduction of apical plasma labeling of pS256-AQP2. In K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, internalization of pS261-AQP2 was blocked and a pronounced reduction in the rate of apical plasma labeling of pS256-AQP2 in the IMCD cells was observed.

Figure 3.

Light micrographs of the inner medulla of control (Cont) and K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mouse kidneys illustrating immunolabeling (a,c,e) and immunoblotting (b,d,f) of total AQP2 (tAQP2) (a,b), pS261-AQP2 (c,d) and pS256-AQP2 (e,f). (a) tAQP2 are immunolabeled in the apical and subapical domains of the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD, stars) cells in both control Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice. After K+ depletion, however, tAQP2 can be observed in intracellular vesicles and throughout the cytoplasm in K+-Dep Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice, respectively. (c) Note those, after K+ depletion, changes of intracellular pattern of immunoreactivity of pS261-AQP2 are similar to those of tAQP2 as shown in (a). (e) It can be observed that apical pS256-AQP2 immunolabeling is markedly reduced in K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice, and this change is pronounced in K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice. (b,d,f) The protein amount of pS261-AQP2 and pS256-AQP2 are significantly decreased after both K+-depletion compared with controls in both Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice.

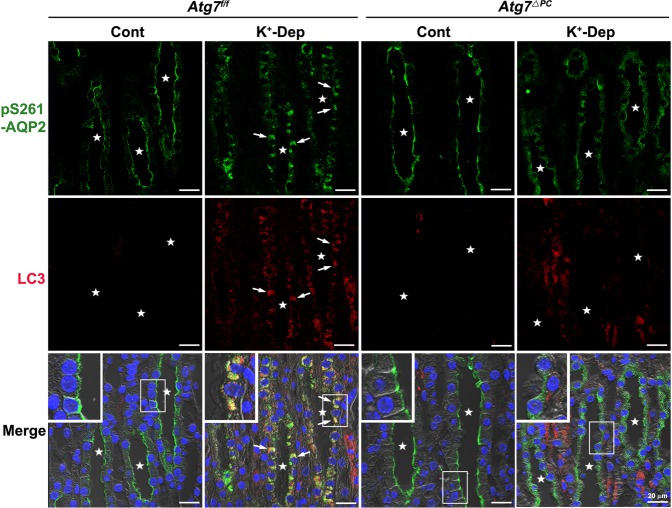

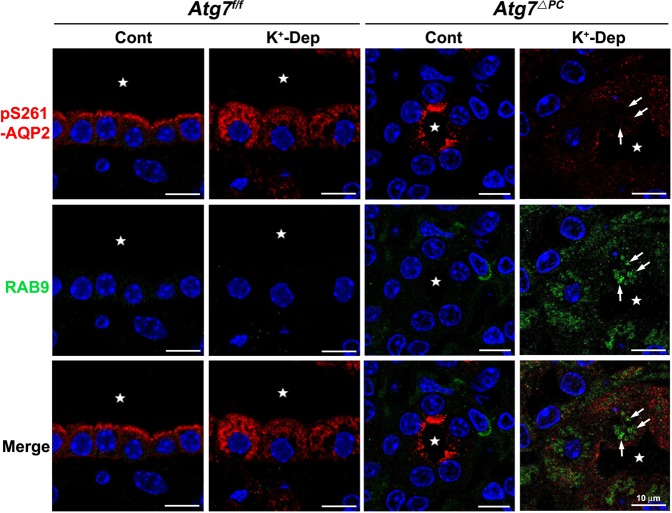

pS261-AQP2 colocalizes with canonical autophagic vacuoles but not with non-canonical autophagic vacuoles

Our previous findings demonstrated that hypokalemia induced autophagy and the redistribution of pS261-AQP2 from the apical or subapical domains to intracellular vesicles. Considering that cytoplasmic component and organelles are degraded by an autophagy pathway, we hypothesized that autophagy regulates water homeostasis through the degradation of pS261-AQP2. To examine this hypothesis, we performed double or multiple immunofluorescence staining using antibodies for pS261-AQP2, LC3, and RAB9, and ultrastructural immunocytochemistry for pS261-AQP2 or pS256-AQP2. Double immunofluorescence staining for pS261-AQP2 and LC3 revealed that pS261-AQP2 was colocalized with LC3-positive puncta in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice (Fig. 4). To confirm these findings at the ultrastructural level, immunocytochemical electron microscopy was used to show that the large irregular shaped autophagic vacuoles in the IMCD cells from K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice were labeled with pS261-AQP2 (Fig. 5a–c). As mentioned above and reported elsewhere36,37, non-canonical autophagy was induced by Atg7 knockout especially under conditions of K+-depletion. However, in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, no immunolabeling for pS261-AQP2 was detected in the small round autophagic vacuoles (Fig. 5b–d). As expected based on the light microscopic immunohistochemical results (Fig. 3e), we confirmed that no immunoreactivity for pS256-AQP2 was observed in the autophagic vacuoles of the IMCD not only in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice but also in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice (Supplementary Fig. S5). Subsequently, to confirm whether the degradation of pS261-AQP2 in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice occurred also through the non-canonical autophagic pathway, we performed double immunolabeling for pS261-AQP2 and RAB9, which is essential for membrane expansion and fusion in alternative autophagy. We found that pS261-AQP2 was not colocalized with RAB9-positive puncta in the IMCD cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 6). Rather, pS261-AQP2 demonstrates a similar redistribution pattern as total AQP2, suggesting that pS261-AQP2 is subject to the same degradation pathway as total AQP2 as a consequence of hypokalemia. These findings indicate that the degradation of pS261-AQP2 after K+ depletion is mediated by LC3-positive/RAB9-negative canonical autophagy, but not by LC3-negative/RAB9-positive non-canonical autophagy.

Figure 4.

Confocal micrographs of the inner medulla of control (Cont) and K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mouse kidneys illustrating double labeling for pS261-AQP2 (green) and LC3 (red). Insets are higher magnification of the areas indicated by the rectangles. In K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice, pS261-AQP2-positive intracellular vesicles are colocalized with LC3 (arrows). In contrast, in K+-Dep of Atg7Δpc, pS261-AQP2 is diffusely expressed in the cytoplasm of inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells and is not colocalized with LC3. Stars indicate the lumen of inner medullary collecting ducts.

Figure 5.

Immunoelectron micrographs of the middle (IMm) (a,b) and terminal (IMt) (c,d) parts of the inner medulla of K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f (a,c) and Atg7Δpc (b,d) mice illustrating immunostaining for pS261-AQP2. Inserts are light micrographs of 1 μm-thick semi-thin sections of the same group. Lower panels are higher magnification of the areas indicated by the rectangles in upper panels. pS261-AQP2 is intensely labeled in the large and irregular shaped canonical autophagosomes in K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice (a,c), but not labeled in the small and regular shaped non-canonical autolysosomes (arrows) in K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice (b,d). Note that pS261-AQP2 is diffusely expressed throughout the cytoplasm in the inner medullary collecting duct cells (b,d). Open arrows indicate the pS261-AQP2-negative autophagic vacuoles in the interstitial cells (IC). Stars indicate the lumen of inner medullary collecting ducts (a–d).

Figure 6.

Confocal micrographs of the inner medulla of control (Cont) and K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mouse kidneys illustrating double labeling with pS261-AQP2 (red) and RAB9 (green). RAB9-positive puncta (green) is increased in both control and K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice; subsequently these changes in the K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice pronounced compared with Atg7f/f mice. Note that pS261-AQP2 is not colocalized with RAB9-positive puncta (arrows) in the inner medullary collecting duct cells of K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice. Stars indicate the lumen of inner medullary collecting ducts.

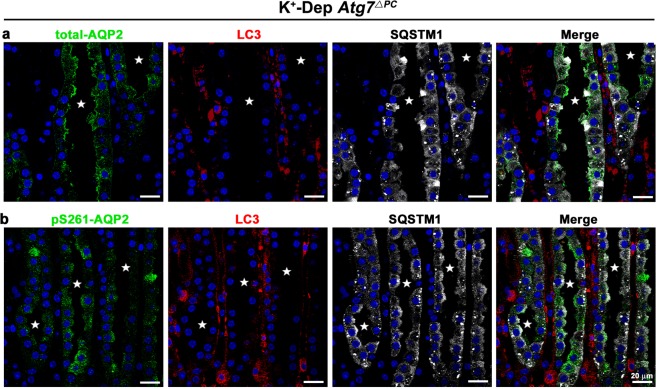

pS261-AQP2 does not colocalize with SQSTM1

As shown in Fig. 1c and d, SQSTM1 was significantly increased in the IMCD cells after Atg7 deletion. Substantial evidence has been reported that both ubiquitinated and non-ubiquitinated proteins are aggregated by SQSTM1, which recruits a phagophore through direct interaction with the LC3 autophagic adaptor, and are continuously regulated by autophagic clearance42,43. To identify whether SQSTM1 is involved in degradation of AQP2, we performed multiple immunostaining for SQSTM1, LC3, and total AQP2 or pS261-AQP2. SQSTM1 did not colocalize either with total-AQP2, pS261-AQP2, or with LC3 in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 7). These findings indicate that SQSTM1 is not involved in the degradation of total- and pS261-AQP2.

Figure 7.

Confocal micrographs of inner medulla of K+-depleted (K+-Dep) Atg7Δpc mice illustrating triple labeling with total-AQP2 (green, a) or pS261-AQP2 (green, b), LC3 (red), and SQSTM1 (white). In K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice, total-AQP2 or pS261-AQP2 do not colocalized not only with LC3, but also with SQSTM1. Stars indicate the lumen of inner medullary collecting ducts.

AQP2 is increased in urine after Atg7 deletion

As the amount of total- and pS261-AQP2 was decreased in K+-depleted Atg7f/f and, to a greater degree, in Atg7Δpc mice, we postulated that AQP2 might be excreted into the urinary space by exosome secretion in hypokalemia. To test this hypothesis, we examine the urinary exosome secretion of total-AQP2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S6, the total urinary- AQP2 excretion was significantly increased in K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice and these changes were markedly pronounced in Atg7Δpc mice after K+-depletion. Similar data were obtained for CD63, which is a general marker of exosomes (Supplementary Fig. S6). These findings suggest that total-AQP2 containing vesicles are excreted into the urinary space in hypokalemia.

Discussion

Although several studies have shown that a substantial decrease in AQP2 expression is one of the causes of NDI induced by prolonged hypokalemia2,3, the mechanism of down-regulation is not fully understood. Marples et al.2 reported that inclusion bodies in the collecting duct cells, which represent one of the morphologic characteristics of prolonged hypokalemia, are presumably involved in the degradation of AQP2 using an 11-day K+ deprivation rat model. Subsequently, Khositseth et al.44 demonstrated that an early reduction in AQP2 protein was possibly related with the activation of autophagy in hypokalemia induced by restricting dietary K+ for a period of 1–3 days.

In the current study, we generated a prolonged K+ deprivation mouse model by severely restricting dietary K+ for a period of 2 weeks. Our findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating polyuria with alterations in renal concentrating ability and morphology occurring in prolonged K+ deprivation models1,2,21,22,45. We observed that cytoplasmic droplets accumulated not only in the IMCD cells but also in other cells in the renal papilla in the K+-restricted mice kidney, as previously reported in several studies24,45. In addition, the present report is the first to confirm that these cytoplasmic droplets represent LC3-positive autophagic vacuoles using light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. In response to hypokalemia from a K+-restricted diet for 2 weeks, total-AQP2 and pS261-AQP2 were redistributed from the apical or subapical domains to intracellular LC3-positive autophagic vacuoles. Furthermore, these proteins were not co-localized with RAB9, indicating that AQP2-containing vacuoles comprise canonical autophagic vacuoles.

Notably, downregulation of AQP2 by canonical autophagic degradation in hypokalemia is not the results of an unspecific downregulation of proteins. Jung et al.45 previously demonstrated that the cytoplasmic droplets induced by prolonged hypokalemia were not labeled for urea transporter-A1 using the immunogold method. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated that the mRNA expression and protein abundance of colonic H+-K+-ATPase are rather increased in K+-deprived rats46. These results suggest that the canonical autophagic degradation of AQP2 and the suppression of AQP2 in the collecting duct is a specific response to K+ deprivation. Overall, these findings indicate that canonical autophagy mediates water homeostasis by regulating the degradation of total- and pS261-AQP2, underscoring the clinical importance of autophagy in maintaining water balance.

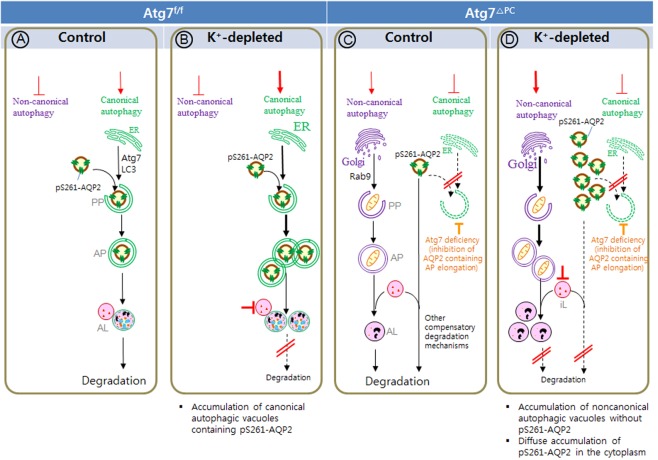

Generally, it has been believed that Atg5 and Atg7 are essential for mammalian autophagy47,48. As we expected that, in the K+-depleted principal cell-specific Atg7-knockout mice, a marked decrease of immunoreactivity for LC3-II was observed restrictively in the IMCD cells, whereas immunoreactivity for LC3-II remained in the other structures including interstitial cells and thin limb cells of Henle’s loop. Furthermore, SQSTM1 was significantly increased only in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice especially with K+-depletion for 2 weeks, suggesting that, in the renal papilla, Atg7-dependent canonical autophagy was selectively inhibited in the IMCD cells of Atg7Δpc mice. These immunohistochemical results explained that the reason why even in the renal papilla of Atg7Δpc mice had signals for LC3-II in the applied lysates, in contrast to the results of Komatsu et al.48 who generated the conditional knockout mice of Atg7 mouse observed no LC3-II in ATG7-deficient tissues. Recently, in addition to canonical autophagy, Nishida et al.36 demonstrated the existence of an LC3-ATG7-independent autophagy or non-canonical autophagy49, which has been considered to be regulated by RAB936,37,50. This is consistent our findings showing that autophagic vacuoles were observed in Atg7-deficient mice after K+ depletion, which suggested the existence of an ATG7-independent macroautophagy pathway. Notably, RAB9, which was not activated in Atg7f/f mice in response to hypokalemia, was markedly activated in Atg7 deficient mice. These findings let us to postulate that the non-canonical autophagy pathway might serve as a compensatory mechanism in the canonical autophagy-deficient state to maintain cellular homeostasis. However, RAB9-positive autophagic vacuoles in Atg7 deficient mice were only faintly labeled with total-AQP2 or pS261-AQP2. Furthermore, activation of the non-canonical autophagy was not able to rescue canonical autophagy deficient mice from the urinary concentration defects in hypokalemia. Our transmission electron microscopy data indicated that Atg7-deleted IMCD cells contained well developed Golgi complexes, which are essential for the formation of the autophagosomes of non-canonical autophagy36,51, reinforcing the concept that a non-canonical autophagy is operant in Atg7-deficient IMCD cells of Atg7f/f mice to compensate for the functional loss of canonical autophagy. The reason of that no non-canonical autophagic vacuoles are observed under basal conditions in Atg7-deficient mice might be a result of normal autophagic flux by active lysosomes (Fig. 8c). In contrast, in Atg7-deficient mice after K+ depletion, LC3-negative, non-canonical autophagic vacuoles are accumulated as a result of the blockade of autophagic flux by the inactivation of lysosomes (Fig. 8d). These findings suggest that non-canonical autophagy is activated in canonical autophagy deficient mice but that this activated non-canonical autophagy has only a limited role in AQP2 degradation. Because the ATG7-dependent autophagy-impaired IMCD cells displayed minimal functional defect and did not lose their autophagy response, it might be surmised that the IMCD cells have compensated in some way to resume obligatory ATG7-dependent canonical autophagy. In Atg7-deficient mice after K+ depletion, total- and pS261-AQP2 redistribute throughout the cytoplasm from apical plasma membrane (Fig. 8d).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram summarizing the regulation of canonical autophagy and non-canonical autophagy in pS261-AQP2 degradation, and the cellular accumulation of different autophagic structures in inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells of control (a,c) and K+-depleted (b,d) Atg7f/f (a,b), and Atg7Δpc (c,d) mice. Depicted are the relative amounts of phagophores (PP), autophagosomes (AP), and autolysosomes (AL). (a) Under normal condition of Atg7f/f mice, pS261-AQP2 degradation is regulated by canonical autophagy. There is no accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, because of normal autophagic flux. (b) In K+-Dep Atg7f/f mice, canonical autophagosomes containing pS261-AQP2 are accumulated in IMCD cells as a result of the blockade of autophagic flux by the inactivation of lysosome. Non canonical autophagy is not activated in both control (a) and K+-Dep (b) Atg7f/f mice. (c) When canonical autophagy is suppressed by Atg7 deletion, which is accompanied by enhanced activity of other lysosomal degradation mechanisms. These compensating mechanisms for canonical autophagy deficiency, resulting in no significant accumulation of AQP2 in the IMCD cells of control Atg7Δpc mice. (d) In K+-Dep Atg7Δpc mice, pS261-AQP2 is accumulated throughout the cytoplasm as a result of impairment of compensatory other lysosomal degradation mechanisms by inactivated lysosome. Non-canonical autophagic vacuoles without AQP2 are also accumulated as a result of impairment of non-canonical autophagy flux by inactivated lysosome.

The impairment of the autophagic lysosomal degradation of total-AQP2 and pS261-AQP2 in hypokalemia caused a severe urinary concentration defect. Whereas the precise mechanism underlying this effect is unclear, three plausible explanations exist. The first possibility arises from the decrease of IMCD cell apical labeling by pS256-AQP2 in both Atg7f/f and Atg7Δpc mice in response to hypokalemia, which is pronounced in the Atg7Δpc mice (Fig. 8b,d). The importance of pS256-AQP2 in AQP2 trafficking from the intracellular vesicles to the surface membrane has previously been suggested. Vasopressin acts on the V2 receptor, causing phosphorylation at Ser 256 and trafficking of the modified AQP2 to the surface membrane52–54. Eto et al. revealed that phosphorylation at Ser256 increased water permeability55. Furthermore, even under basal conditions, with free access to water, the reason why K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice had an increase in urine volume and a decrease in urine osmolarity is also because the reduction of protein level and apical labeling of pS256-AQP2. Therefore, impairment of the apical labeling by pS256-AQP2 in autophagy-deficient mice likely caused the urinary concentration defect.

The second possible mechanism underlying this defect is exosomal secretion of AQP2. Secretion of intact AQP2 into the urine was first identified by Kanno et al.56 Subsequently, the mechanism of AQP2 delivery into the urine was identified to occur via exosome secretion57–59. Under a steady-state condition, an increase in urinary AQP2 excretion might reflect either an increase in synthesis or a decrease in degradation. As shown in Sup Fig S6, Atg7 deficiency resulted in a failure in the generation of canonical autophagosomes and thereby, a large fraction of AQP2-containing vesicles were delivered from the intracellular compartment to the lumen by exosome secretion. Increased exosome secretion of AQP2 is accompanied by a decrease in renal medullary AQP2 protein as has been previously reported by Higashijima et al.60, which might therefore cause the observed urinary concentration defect.

The third potential mechanism underlying the urinary concentration defect is SQSTM1 mediated degradation of AQP2. Substantial evidence supports that the autophagic adaptor SQSTM1 acts as a cargo receptor for the degradation of ubiquitinated substrates61. For example, ubiquitinated proteins are aggregated by SQSTM1, which recruits a phagophore through direct interaction with LC3. The cellular contents in SQSTM1 are continuously regulated by autophagic clearance42,62,63. It has recently been demonstrated that SQSTM1 also has the ability to target non-ubiquitinated proteins for degradation43. In this study, we confirmed that the accumulation of SQSTM1 in the cytoplasm of IMCD cells occurred after Atg7 deletion, as previously reported64,65. However, we further observed that SQSTM1 colocalized neither with total-AQP2 nor with pS261-AQP2 in K+-depleted Atg7Δpc mice, suggesting that SQSTM1 was not involved in the degradation of total- and pS261-AQP2.

In summary, our results demonstrated that urinary concentrating defect in hypokalemia is induced by reduced AQP2 phosphorylation, resulting in a reduction of apical labeling of pS256-AQP2. Our data demonstrated, also, that autophagy, occurring primarily through a LC3/Atg7-dependent canonical autophagy pathway, is involved in the degradation of total- and pS261-AQP2 in IMCD cells. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of AQP2 degradation and water homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of principal cell-specific Atg7 knockout mice and K+ depletion model

To generate mice with an Atg7 deletion specifically in the principal cells of the collecting duct (Atg7Δpc), we crossed Atg7flox/flox mice (Atg7f/f) (kindly provided by Dr. Komatsu, School of Medicine, Niigata University) with aquaporin 2-cre mice (Stock No. 006881, The Jackson Laboratory). The genotypes of offspring were determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using genomic DNA obtained from tails of mice and transgene-specific primers. All mouse lines were bred onto a C57BL/6 background. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital in accordance with the institutional guidelines and regulations on the use of laboratory animals.

In this study, we used only adult male mice (20–25 g, 8 weeks old). The mice were divided into four groups (n = 8–10/group): Atg7f/f control and K+-depletion, Atg7Δpc control and K+-depletion. The control group was fed normal diet (K+; 25 gm, Research Diet Inc.) and distilled water and the K+-depletion group was fed K+-free diet (K+; 0 gm, Research Diet Inc.) and distilled water for 2 weeks.

To monitor autophagy in control and K+-depleted Atg7f/f mice, we introduced GFP-LC3 as a marker for autophagy used green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 transgenic mice (Stock No. RBRC00806, Riken BioResource Center, Japan).

Two weeks later, mice were treated in metabolic cage for collecting 24 hours urine and then anesthetized and blood was collected from abdominal aorta. Blood analysis was performed by i-STAT system with CHEM8+ cartridge (Abott Inc.) Urine analysis was carried out by Samgwang Medical Foundation (Hitachi 7600-110, Urisys 2400, etc.).

Antibodies

The antibodies used included those against LC3B for western blotting (Cat. No. L7543, Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) and for immunohistochemistry (Cat. No. 0231-100/LC3-5F10, Nanotools), SQSTM1 (Cat. No. GP62-C, Progen), RAB9 (Cat. No. ab2810, Abcam), pS261-AQP2 (Cat. No. ab72383, Abcam), pS256-AQP2 (Cat. No. ab109926, Abcam & kindly provided by Prof. Tae-Hwan Kwon, Kyungpook National University, Korea), and total AQP2 (Cat No. AQP-002, Alomone).

Western blotting

After experimental treatment, the mice were anesthetized and perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The inner medulla of the kidney was isolated and homogenized with boiling lysis buffer (1.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1.0 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH7.4) as previously described66 and protein concentration was determined using the BCA kit (Cat. No. 23225, Pierce Biotechnology Inc.). Equal amounts of the protein were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skim milk and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight. The next day, the membranes were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies and the signals were detected using a western blotting luminol reagent kit (Cat. No. sc 2048, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and quantified by densitometry with a Multi Gauge instrument (v 3.0, Fusifilm). Quantification the immunoblot signals of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. The signals were scanned, and the amounts of target proteins were quantified in arbitrary unit ± SE. The precise methods were described in a previous report67.

Immunohistochemistry for light microscopy

After experimental treatment, the mice were anesthetized, perfused with PBS, and then fixed with a 2% paraformaldehyde-lysine-periodate solution for 10 min. The kidneys were removed and cut into 1–2 mm thick slices, which were postfixed by immersion in the same fixative overnight at 4 °C. The kidneys were then embedded in poly (ethylene glycol) (400) distearate (Cat. No. 01048, Polysciences Inc.) and cut transversely at a thickness of 4 μm using a microtome. Tissue sections were hydrated with graded ethanol and rinsed in tap water. The sections were then treated with a retrieval solution (pH 6.0), methanol containing 5% H2O2, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, normal donkey serum, and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day, after washing in PBS, the tissue sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies and the signals were visualized using a 0.05% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 mixture. Then sections were next washed with distilled water, dehydrated with graded ethanol and xylene, mounted in Canada balsam, and examined by light microscopy using Olympus BX51. The precise methods were described in a previous report68.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Tissue sections were hydrated with graded ethanol and rinsed in tap water. The sections were then treated with a retrieval solution (pH 6.0), 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, normal donkey serum, and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day, after washing in PBS, the tissue sections were incubated with the fluorescence-labeled appropriate secondary antibodies and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 700 Confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Transmission electron microscopy

The mice were anesthetized, perfused with PBS, and then fixed with a 2% paraformaldehyde-2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 10 min. The inner medulla of the kidneys were removed and cut into 0.5–1 mm pieces and postfixed by immersion in the same fixative overnight at 4 °C. The tissues were then dehydrated with graded ethanol and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 resin (Polyscience). Ultrathin sections were cut and photographed using a JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope.

Immunocytochemistry for electron microscopy

After fixation, the kidney sections were cut transversely using a vibratome to a thickness of 50 μm and processed for immunocytochemistry. Sections were washed with PBS and treated with 50 mM NH4Cl. Prior to incubation with the primary antibodies, the sections were pretreated with a graded series of ethanol and then incubated for 4 h in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.05% saponin, and 0.2% gelatin. The tissue sections were next incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After several washes in PBS containing 0.1% BSA, 0.05% saponin, and 0.2% gelatin, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies, washed, and colorized with a 0.1% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 mixture for 10 min. The tissue sections were treated with 1% glutaraldehyde and 1% OsO4, dehydrated with graded ethanol, and embedded with Poly/Bed 812 between polyethylene vinyl sheets. Sections from the inner medulla were excised and glued onto empty blocks of Poly/Bed 812. Ultrathin sections were cut and photographed using a JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope. The precise method was as described in a previous report69.

Quantification of the autophagic area

The autophagic area was measured using the Multi Gauge system. IMCD cells were chosen and the autophagic area (autophagic area (%) = total autophagic vacuoles area/cytoplasm area (whole cell area–nucleus area) was measured. In this study, over 20 images per group were measured.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Fifty microliter of urine samples or standard AQP2 synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acis 257 to 271 of human AQP2 were added to coat a Maxisorp 96-well microplate (NUNC, Rochester, NY, USA). After incubation overnight at 4 °C, the plate was washed, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then the blocking solution was removed, and the diluted rabbit polyclonal antibody AQP2 was added to each well. After incubation at 37 °C for two hours, the plate was washed, and diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) was added to each well. After incubation at 37 °C for one hour, the plate was washed, and 150 of the substrate solution [2, 2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added. After incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark, the reaction was stopped by adding 150 of 1% SDS, and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as the means ± SD. Differences between groups were evaluated using the Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2012R1A2A2A01045884, NRF-2016R1D1A1B03932970, NRF-2018R1A2B6003440 and NRF-2016R1A6A3A11931412) and MRC for Cancer Evolution Research Center (NRF-2012R1A5A2047939).

Author Contributions

W.K. designed the study, performed statistical analyses, and wrote the text. S.N., A.C., and Y.K. carried out the experiment. S.P. and H.K. participated in technical assistants. H.K., K.H., and C.Y. helped to guide the manuscript. M.L. helped the generation of transgenic mice. Y.K. and J.K. designed this study, wrote the manuscript and acquired the funding for this project.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yong Kyun Kim, Email: drkimyk@catholic.ac.kr.

Jin Kim, Email: jinkim@catholic.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-39702-4.

References

- 1.Trepiccione, F., Zacchia, M. & Capasso, G. In Seldin and Giebisch’s The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology (eds Alpern, R. J., Caplan, M. J. & Moe, O. W.) 1717–1739 (Academic Press, 2013).

- 2.Marples D, Frokiaer J, Dorup J, Knepper MA, Nielsen S. Hypokalemia-induced downregulation of aquaporin-2 water channel expression in rat kidney medulla and cortex. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1960–1968. doi: 10.1172/jci118628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amlal H, Krane CM, Chen Q, Soleimani M. Early polyuria and urinary concentrating defect in potassium deprivation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F655–663. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.4.F655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim K, Lee JH, Kim SC, Cha DR, Kang YS. A case of primary aldosteronism combined with acquired nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2014;33:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radin MJ, et al. Aquaporin-2 regulation in health and disease. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012;41:455–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165x.2012.00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda M, Matsuzaki T. Regulation of aquaporins by vasopressin in the kidney. Vitam. Horm. 2015;98:307–337. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenton RA, Pedersen CN, Moeller HB. New insights into regulated aquaporin-2 function. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2013;22:551–558. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328364000d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Wang G, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of vasopressin-sensitive renal cells: regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at two sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7159–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600895103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. Phosphoproteomics of vasopressin signaling in the kidney. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8:157–163. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kortenoeven ML, Fenton RA. Renal aquaporins and water balance disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:1533–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arthur J, et al. Characterization of the putative phosphorylation sites of the AQP2 C terminus and their role in AQP2 trafficking in LLC-PK1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F673–679. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00152.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffert JD, et al. Dynamics of aquaporin-2 serine-261 phosphorylation in response to short-term vasopressin treatment in collecting duct. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F691–700. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamma G, Robben JH, Trimpert C, Boone M, Deen PM. Regulation of AQP2 localization by S256 and S261 phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C636–646. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00433.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice WL, et al. Differential, phosphorylation dependent trafficking of AQP2 in LLC-PK1 cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice WL, et al. Polarized Trafficking of AQP2 Revealed in Three Dimensional Epithelial Culture. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsura T, Gustafson CE, Ausiello DA, Brown D. Protein kinase A phosphorylation is involved in regulated exocytosis of aquaporin-2 in transfected LLC-PK1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:F817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Balkom BW, et al. The role of putative phosphorylation sites in the targeting and shuttling of the aquaporin-2 water channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41473–41479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffert JD, et al. Vasopressin-stimulated increase in phosphorylation at Ser269 potentiates plasma membrane retention of aquaporin-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:24617–24627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stodkilde L, et al. Bilateral ureteral obstruction induces early downregulation and redistribution of AQP2 and phosphorylated AQP2. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F226–235. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00664.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mujais SK, Chen Y, Nora NA. Vasopressin resistance in potassium depletion: role of Na-K pump. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:F705–710. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.4.F705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheval L, et al. Plasticity of mouse renal collecting duct in response to potassium depletion. Physiol. Genomics. 2004;19:61–73. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00055.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris RG, Hoorn EJ, Knepper MA. Hypokalemia in a mouse model of Gitelman’s syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1416–1420. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00421.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar K, Levine DZ. A correlated study of kidney function and ultrastructure in potassium-depleted rats. Nephron. 1975;14:347–360. doi: 10.1159/000180465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar K, Levine DZ. Ultrastructural changes in the renal papillary cells of rats during maintenance and repair of profound potassium depletion. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1979;60:120–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aithal HN, Toback FG, Dube S, Getz GS, Spargo BH. Formation of renal medullary lysosomes during potassium depletion nephropathy. Lab. Invest. 1977;36:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindqvist, L. M., Simon, A. K. & Baehrecke, E. H. Current questions and possible controversies in autophagy. Cell Death Discov1, 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.36 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Fougeray S. & Pallet, N. Mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy in diseased and ageing kidneys. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:34–45. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Jiang M, Schoenlein P, Dong Z. Autophagy: molecular machinery, regulation, and implications for renal pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F244–256. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00033.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber TB, et al. Emerging role of autophagy in kidney function, diseases and aging. Autophagy. 2012;8:1009–1031. doi: 10.4161/auto.19821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maejima Y, et al. Recent progress in research on molecular mechanisms of autophagy in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;308:H259–268. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00711.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:859–864. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanida I, et al. Apg7p/Cvt2p: A novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:1367–1379. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanida I, Tanida-Miyake E, Ueno T, Kominami E. The human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Apg7p is a Protein-activating enzyme for multiple substrates including human Apg12p, GATE-16, GABARAP, and MAP-LC3. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1701–1706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishida Y, et al. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature. 2009;461:654–658. doi: 10.1038/nature08455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu S, Arakawa S, Nishida Y. Autophagy takes an alternative pathway. Autophagy. 2010;6:290–291. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu S, Honda S, Arakawa S, Yamaguchi H. Alternative macroautophagy and mitophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;50:64–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klionsky DJ, Lane JD. Alternative macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:201. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juenemann K, Reits EA. Alternative macroautophagic pathways. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012;2012:189794. doi: 10.1155/2012/189794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bankaitis VA. Unsaturated fatty acid-induced non-canonical autophagy: unusual? Or unappreciated? EMBO J. 2015;34:978–980. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirkin V, Lamark T, Johansen T, Dikic I. NBR1 cooperates with p62 in selective autophagy of ubiquitinated targets. Autophagy. 2009;5:732–733. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe Y, Tanaka M. p62/SQSTM1 in autophagic clearance of a non-ubiquitylated substrate. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:2692–2701. doi: 10.1242/jcs.081232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khositseth S, et al. Autophagic degradation of aquaporin-2 is an early event in hypokalemia-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18311. doi: 10.1038/srep18311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung JY, et al. Expression of urea transporters in potassium-depleted mouse kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F1210–1224. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00111.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silver RB, Soleimani M. H+-K+-ATPases: regulation and role in pathophysiological states. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:F799–811. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.6.F799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuma A, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niso-Santano M, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids induce non-canonical autophagy. EMBO J. 2015;34:1025–1041. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirota, Y., Fujimoto, K. & Tanaka, Y. In Autophagy-a Double-edged Sword-cell Survival Or Death? (ed. Bailly, Y.) 47–63 (InTech, 2013).

- 51.Cao Y, et al. Hierarchal autophagic divergence of hematopoietic system. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:29240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A115.650028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fushimi K, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Phosphorylation of serine 256 is required for cAMP-dependent regulatory exocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14800–14804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christensen BM, Zelenina M, Aperia A, Nielsen S. Localization and regulation of PKA-phosphorylated AQP2 in response to V(2)-receptor agonist/antagonist treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2000;278:F29–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Promeneur D, Kwon TH, Frokiaer J, Knepper MA, Nielsen S. Vasopressin V(2)-receptor-dependent regulation of AQP2 expression in Brattleboro rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F370–382. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eto K, Noda Y, Horikawa S, Uchida S, Sasaki S. Phosphorylation of aquaporin-2 regulates its water permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:40777–40784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanno K, et al. Urinary excretion of aquaporin-2 in patients with diabetes insipidus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/nejm199506083322303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pisitkun T, et al. High-throughput identification of IMCD proteins using LC-MS/MS. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;25:263–276. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00214.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson JL, Miranda CA, Knepper MA. Vasopressin and the regulation of aquaporin-2. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2013;17:751–764. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0789-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Higashijima Y, et al. Excretion of urinary exosomal AQP2 in rats is regulated by vasopressin and urinary pH. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2013;305:F1412–1421. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00249.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kirkin V, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bjorkoy G, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Komatsu M, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ichimura Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Komatsu M. Selective turnover of p62/A170/SQSTM1 by autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:1063–1066. doi: 10.4161/auto.6826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim JA, et al. Modulation of TonEBP activity by SUMO modification in response to hypertonicity. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:200. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park EY, et al. Proposed mechanism in the change of cellular composition in the outer medullary collecting duct during potassium homeostasis. Histol. Histopathol. 2012;27:1559–1577. doi: 10.14670/hh-27.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nam SA, et al. Altered response of pendrin-positive intercalated cells in the kidney of Hoxb7-Cre;Mib1f/f mice. Histol. Histopathol. 2015;30:751–762. doi: 10.14670/hh-30.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim WY, et al. Descending thin limb of the intermediate loop expresses both aquaporin 1 and urea transporter A2 in the mouse kidney. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2016;146:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00418-016-1434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.