Abstract

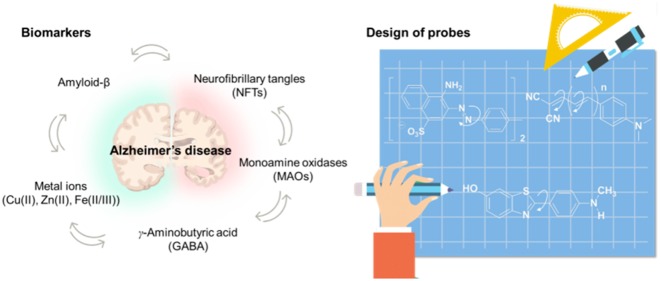

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. The pathogenesis of the disease is associated with aggregated amyloid-β, hyperphosphorylated tau, a high level of metal ions, abnormal enzyme activities, and reactive astrocytes. This outlook gives an overview of fluorescent small molecules targeting AD biomarkers for ex vivo and in vivo imaging. These chemical imaging probes are categorized based on the potential biomarkers, and their pros and cons are discussed. Guidelines for designing new sensing strategies as well as the desirable properties to be pursued for AD fluorescence imaging are also provided.

Short abstract

The molecular design strategies for small-molecule fluorescent probes detecting the potential biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease along with their merits and limitations provide guidelines for their future developments.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), known as the most common type of dementia, is a global concern today.1−3 It is characterized by various pathological markers, including amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), which are two of the main AD hallmarks.4 Fluorescence imaging probes are commonly used in clinical investigations and diagnosis of AD.5,6 Specifically, Aβ plaques and tau tangles can be readily stained by fluorescent chemicals such as thioflavins for microscopic imaging of brain tissues.7 Fluorescent chemicals that penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and target these misfolded proteins were radiolabeled, which became the most innovative chemical contribution to the diagnosis of AD.8−10 Before the discovery of Pittsburgh compound B (PiB), a benzothiazole analogue derived from thioflavin T, autopsy was required to confirm the presence of the misfolded proteins in the brain tissue for a definitive diagnosis of AD.11 Accumulation of Aβ plaques and tau tangles precedes brain atrophy at least for a decade.12 Although the correlation of Aβ plaque levels with cognitive deficits is weak and tau tangles are not AD specific, the two species still remain as gold standards for the early diagnosis of AD. New biomarkers have also been suggested, and diverse small-molecular fluorescent probes are being investigated. In this Outlook, we review the representative AD biomarkers and sensing strategies of fluorescent probes to visualize each of the biomarkers using one-photon or two-photon microscopy, hoping that scientific endeavors in this field could lead to new diagnosis methods at clinical research sites, in addition to providing powerful tools for basic research on this detrimental disease.

2. Misfolded Amyloid-β Species

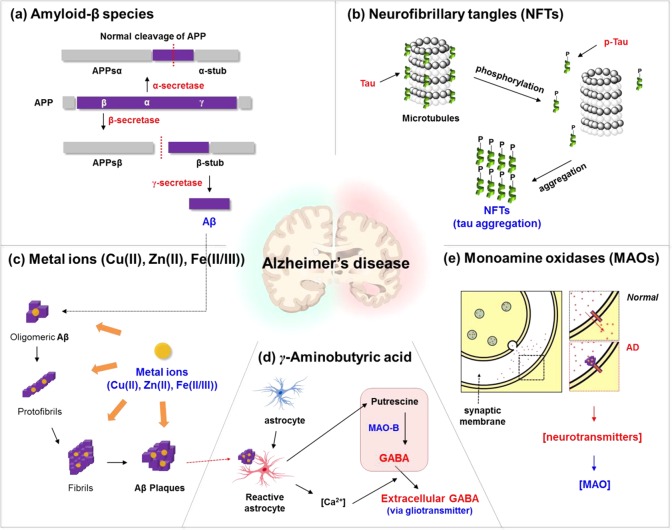

Aggregated Aβ species are considered to be the key pathological marker of AD. Efficient detection of these species is of keen interest for elucidating fundamental aspects of AD.13,14 In the amyloidogenic pathway, cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase produces the N-terminal ectodomain fragment APPsβ and the transmembrane fragment β-stub that is subsequently cleaved by γ-secretase to produce monomeric Aβ peptides, while α-secretase produces APPsα and α-stub in the non-amyloidogenic pathway (Figure 1a).15,16 Twenty missense mutations in APP such as KM670/671NL (Swedish) lead to Aβ peptides of different lengths.17 Monomeric Aβ peptides aggregate into different higher order species of oligomers, fibrils, and plaques (Figure 1c).18 The oligomeric intermediates have attracted particular attention due to their higher neurotoxicity than the plaques.19 Oligomers bind to various synaptic receptors (e.g., NMDAR, PRPc, and AMPAR) modulating several signaling pathways20 and also activate the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immunity system that triggers an inflammatory response21 (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and its relevance in the pathogenesis of the disease. (a) Amyloid-β proteins, (b) neurofibrillary tangles, (c) metal ions (Cu(II), Zn(II), Fe(II/III)), (d) γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and (e) monoamine oxidases.

Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for Misfolded Amyloid-β Species

The generally targeted Aβ species are in a cluster form of amyloids which have compact and homogeneous cross-β sheet structures, providing a hydrophobic environment in contrast to a hydrophilic outside.22 For this reason, a typical sensing strategy is to discriminate the contrasting environments by using environmentally sensitive dyes having intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) excited states. In hydrophilic media, these dyes show poor fluorescence due to the formation of twisted ICT (TICT) states which are generally nonemissive. However, these are strongly fluorescent in hydrophobic media since the TICT is less stabilized, and, instead, a planarized ICT (PICT) state which is strongly emissive is preferred.23 Thus, dipolar dyes emit weakly outside Aβ clusters but strongly inside Aβ clusters, allowing us to detect Aβ plaques (Figure 2a). In addition, the intercalation-induced conformational restriction of dyes inside the plaques can cause additional fluorescence enhancement in general. Most of the known fluorescent probes for Aβ plaques are sterically not bulky and have a linear shape to interact with “aligned” hydrophobic amino acid substituents in the β-sheet structures of Aβ plaques. It is also known that hydrogen bonding can provide additional binding affinity.

Figure 2.

Sensing strategies of AD biomarkers. Development of probes for (a) amyloid-β plaques, (b) neurofibrillary tangles, (c) metal ions (Cu(II), Zn(II), and Fe(II/III)), (d) monoamine oxidases, and (e) astrocytes.

The molecular probes for Aβ species have been developed in three stages (Figure 2a): (i) Charged structures, (ii) neutral donor–acceptor (D–A) dipolar structures with rigid backbone, and (iii) flexible π-conjugated backbone structures. In the 19th century, Congo Red (CR) was introduced as an Aβ plaque probe.24,25 The structural feature of CR is the acidic functional groups (−SO3H). The hydrophilic functional group enhanced water solubility and binding affinity toward Aβ plaques, but significantly reduced their BBB uptake. Although CR’s poor BBB permeability was enhanced through the modification of the backbone structure and substitution moieties (ThT,26 Methoxy-04,27 and AOI-98728), these cationic probes still showed moderate binding affinity toward Aβ plaques and slow clearance from the brain. A neutral version of probes such as PiB which was introduced later alleviated the limitations mentioned above.29,30 The neutral probes showed improved binding affinity, BBB penetration ability, and faster clearance kinetics compared to the charged probes. Lastly, introducing flexible vinylene units, -(CH=CH)n-, into a π-conjugation backbone provided an advantageous feature of minimizing the background signal.31 Rotational motions at the π-conjugation backbone induced nonradiative decay, and restricted rotational motion in a congested environment of Aβ plaques led to enhanced fluorescence. Therefore, a probe with a flexible π-conjugated backbone offers strong fluorescence enhancement with a minimized background signal when it binds with Aβ plaques. The dicyanovinyl group, which is a well-known electron-acceptor and acts as a molecular rotor, can be found in DDNP and related D–A type dipolar dyes. An additional advantage of this approach is the bathochromic shift to the near-infrared (NIR) region by extending the vinyl units. In spite of the great efforts made in this field, however, still it is challenging to detect amyloid oligomers, in addition to detecting Aβ plaques with complete suppression of background signals as well as the very low level of Aβ plaques in blood samples.

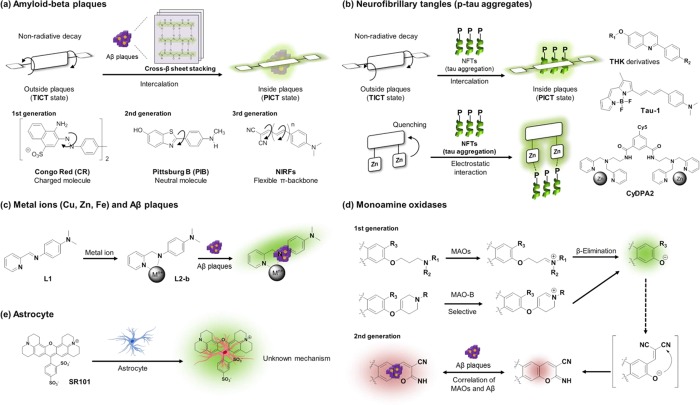

Design Strategies of Two-Photon Absorbing Fluorescent Probes for Misfolded Amyloid-β Species

For imaging biological systems with fluorescent probes, use of the longer wavelengths, preferably in the far-red or NIR region, is beneficial to obtain minimal autofluorescence from innate biological species, reduced light scattering, deep tissue penetration, and less photobleaching.32 In the same vein, two-photon and multiphoton microscopies (MPM) have received increasing interest in recent years (Figure 3a).33 Generally, Aβ plaques in AD mouse models first appear in the deeper layer of the cortex (>500 μm depth) and then gradually spread out to the entire cortex (Figure 3b).34 Therefore, the deep-tissue imaging capability for the AD biomarker is crucial for in vivo studying of AD in the animal model at an early stage. Accordingly, fluorescent probes having efficient two-photon absorbing properties, which are expressed by two-photon absorption cross section (TPACS, σ) in the unit of GM (Göppert-Mayer), are highly desired along with far-red and NIR emission. A general design strategy for such probes is to extend the π-conjugated backbone of dipolar dyes that have electron-donor and -acceptor groups at the opposite ends. Unfortunately, however, extension of the π-conjugated backbone structure also increases the molecular size of probes, which in turn reduces their photo- and chemical stability, water solubility, BBB permeability, and degree of ICT, all of which are undesirable features. Thus, it is challenging to compromise these conflicting issues in order to develop TP probes with large TPACS values and longer absorption/emission wavelengths.35

Figure 3.

Two-photon probes for detecting AD biomarkers. (a) Illustration of two-photon absorption, pulsed laser and focal point excitation. (b) Illustration of the distribution of amyloid-β plaques in the brain. (c–h) Two-photon amyloid-β probes: (c) 2E10, STB-8, PiB, (d) benzothizole 4, (e) NIRFs, Aβ probe 5, (f) SAD-1, (g) CRANADs, and (h) QAD-1. (i) A two-photon dual probe for MAOs and amyloid-β plaques.

Chang and co-workers found the 2E10 dye through screening of a fluorescent styryl dye library, but it had poor BBB penetration capability.36 In order to overcome this drawback, the structure was modified into neutral analogues, and eventually STB-8 was developed for in vivo two-photon imaging (Figure 3c).37 In 2013, Kim and co-workers reported a TP probe for Aβ plaques, SAD-1, by combining PiB and acedan that is a well-known TP dye.38 SAD-1 had a nanomolar level of dissociation constant (Kd = 17 nM) for the Aβ plaques and was used to construct in vivo two-photon 3D images (Figure 3f). The benzothiazole compound 4, a hybrid structure between PiB and STB-8, was developed as a PET tracer.39 A vinyl spacer between the two aryl groups was introduced to increase the molecular flexibility (Figure 3d). Muruhan and co-workers found that the elongation of the spacer in near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) probes results in bathochromic shifts with larger TPACS values.31 Later, Ahn and co-workers reported a modified version, Aβ probe 5, which has a more rigid backbone structure and thus shows higher photochemical stability and also emits stronger fluorescence than the acyclic analogue.40 The Aβ probe 5 readily penetrated BBB and visualized Aβ plaques down to >300 μm depth using two-photon microscopy (Figure 3e). Moore, Ran, and co-workers reported curcumin derivatives as two-photon probes for Aβ plaques.41 Since curcumin has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and lipophilic action, which improve the cognitive functions of AD patients, it has been also used for the treatment of AD.42 However, bioimaging application of the curcumin derivatives was limited due to their low fluorescence quantum yields. To overcome this limitation, curcumin derivatives, CRANAD compounds, were prepared by converting the enolate moiety into the corresponding boron complex and replacing the aryl groups of curcumin with different aromatic substrates. The first boron complex CRANAD-2 displayed a significantly increased fluorescence in the NIR region; however, CRANAD-2 was not able to detect soluble Aβ species such as monomeric Aβ peptide and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). The second-generation boron-complexes, CRANAD-3 and CRANAD-28, displayed excellent fluorescent responses toward Aβ species including soluble Aβ monomers, dimers, and oligomers with high binding affinity (Figure 3g). Similarly, a quadrupolar type dye, QAD1, reported by Kim and co-workers showed high two-photon absorbing property (σmax = 420 GM) and dramatic fluorescence enhancement upon the binding with Aβ plaques (Figure 3h).43

3. Hyperphosphorylated and Aggregated Tau Proteins

In healthy neurons, the microtubules are assembled and stabilized by tau proteins. During neurodegeneration, tau proteins are often found detached from the microtubules and modified by multiple post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, proteolysis, and glycosylation in the intracellular region.44 In the case of AD, intra- and extracellular hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins and subsequent formation of NFTs are the key biomarkers for clinical diagnosis. Formation of hyperphosphorylated form of tau (p-tau) is favored in the AD brain due to the imbalance of kinases and phosphatases. p-Tau loses its binding affinity to microtubule assembly and disintegrates to form tau aggregates and eventually NFTs.45 The abnormal NFTs destroy a vital cell transport system, eventually leading to neuronal cell death.46 There is approximately a 4–8-fold higher level of p-tau proteins in the AD brain compared to that of age-matched healthy brain.47 Similar to amyloid plaques, NFTs exhibit a characteristic distribution pattern of growth from entorhinal cortex to hippocampus to neocortex.

Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for Tau Protein

To date, a few molecular probes for p-tau aggregates have been reported, and they were developed mainly based on two detection strategies: intercalation of probes into p-tau aggregates and electrostatic binding of probes containing zinc ion with the phosphate groups in p-tau aggregates (Figure 2b). The sensing strategy for NFTs is not as apparent as it is for Aβ aggregates, plausibly due to the less defined binding modes in the case of p-tau aggregates. The most challenging part in the approach using the intercalation with p-tau aggregate is to secure selective binding affinity toward p-tau aggregates over Aβ plaques. Most of the known probes for p-tau and Aβ plaques are structurally somewhat similar (Figure 2b). Therefore, the way to find hit compounds showing selective binding affinity for p-tau has been to rely on a random screening method. Recently, it was proposed that a distance of 13–19 Å between the donor and acceptor in the probes benefits NFTs selectivity, while a shorter distance favors Aβ plaques and that, among similar compounds, fused ring containing probes show higher selectivity for tau over Aβ fibrils.48 Okamura and co-workers evaluated over 2000 molecular probe candidates in search of those with higher binding affinity for NFTs over Aβ species, and eventually they found a series of aryl-quinoline derivatives, the THK derivatives.49 Among them, THK-523 allowed noninvasive quantification of p-tau aggregates, K18Δ280K, over Aβ plaques for the first time, along with high in vitro binding affinity (Kd = 1.67 nM) and fast BBB penetration (20 min, Log P = 2.91).50 After that, much efforts have been made to develop new p-tau probes, leading to a few more p-tau probes such as the probes based on phenyldiazenyl-benzothiazole (PDB) and styryl-benzimidazole (SBIM) scaffolds by Saji and co-workers,51 thiohydantoin based p-tau probe (TH2) by Ono and co-workers,52 and 18F-T807 by Kolb.53 Recently, Kim and co-workers disclosed a systematic design of a probe Tau-1 that selectively senses p-tau aggregates over Aβ plaques.48 They conducted molecular docking studies with a crystal structure of the PHF6 fragment (306VQIVYK311), the R3 binding region of p-tau protein. Tau-1 showed efficient BBB penetration, low cytotoxicity, as well as in vivo imaging capability in a transgenic mouse model. Since NFTs consist of phosphate groups in p-tau structure, unlike Aβ aggregates, a few probes have been developed by utilizing its binding affinity toward metal ions such as zinc.54 In 2009, Hamachi and co-workers reported BODIPY-1 containing binuclear Zn(II)-2,2′-dipicolylamine (DPA) moieties, which selectively detects p-tau with fluorescent signal enhancement through electrostatic interaction (Figure 2b).55 By using the same approach, Bai and co-workers developed CyDPA2 by replacing the dye part of BODIPY-1 with a NIR emitting cyanine dye.56 Since this approach utilizes selective and strong electrostatic interaction between phosphates group and zinc ion, the probes discriminated p-tau protein (EC50 = 9 nM) over nonphosphorylated tau protein (EC50 = 80 nM) and Aβ plaques (EC50 = 650 nM) in in vitro assays.

4. High Levels of Metal Ions

Copper, zinc, and iron are essential metal ions for brain functions. Normal signaling involves a high level of Zn(II) (∼0.3 mM), flooding over synapses, which activates Cu(II) to be released into the synapses (0.015–0.03 mM).18 Homeostasis breakdown of these metal ions is often observed during the neurodegeneration process in many brain disorders such as AD.57 Epigenetic alterations by environmental exposure and inadequate diet are reported to cause such dysregulation of metal ions.58 In the senile plaques of AD patients, higher concentrations of transition metal ions, particularly Cu(II) (>0.4 mM), Zn(II) (>1.0 mM), and Fe(III) (>0.9 mM), are found.59,60 Increased concentration of transition metal ions affects not only the complexation and stabilization of Aβ plaques but also aggravation of cellular oxidative stress by converting hydrogen peroxide to hydroxyl radical through the Fenton-like reaction: (i) Aβ-Cu(II) + H2O2 → Aβ-Cu(I) + •OOH + H+; (ii) Aβ-Cu(I) + H2O2 → Aβ-Cu(II) + •OH + –OH.18

Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for Metal Ions

To study the relationship between those metal cations and Aβ plaques, Lim and co-workers reported iminopyridyl chelates, L1 and L2-a/b, which bind with both Cu(II) and Zn(II) ions.61,62 These chelates are designed to interact with Aβ plaques after forming the complexes with the metal ions (Figure 2c). L2-b which has high stability in aqueous media detects metal-induced Aβ aggregates in vitro as well as in human neuroblastoma cells. Furthermore, they showed that the dual probes based on this approach could be used to probe Aβ aggregation control, metal chelation, and ROS regulation by mass, NMR, and biochemical analyses. However, L1 and L2-a/-b seem to be not suitable for further fluorescence studies due to its poor fluorescent properties.

5. Upregulated Monoamine Oxidases

Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) are found in the outer mitochondrial membrane of neuronal, glial, and other mammalian cells. MAOs catalyze the oxidative deamination of amine neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, playing an important role in the metabolism of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system.63 MAOs oxidize the amine functionality of neurotransmitters, for example, dopamine, to the corresponding iminium ion, which undergoes hydrolysis to produce the corresponding aldehyde, which in turn is converted into homovanillic acid with the production of hydrogen peroxide and ammonia through other enzymatic processes. MAOs assist in maintaining the homeostasis of neurotransmitters in the brain, thereby supporting appropriate neurological and behavioral outcomes.64 Upregulated activity of MAOs causes excessive production of neurotoxic byproducts such as hydrogen peroxide which promote neuronal dysfunctions of both psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (Figure 1e).65−67 Dysfunction of MAOs is closely associated with AD, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease.68−72 A high level of MAOs, particularly MAO-B, was observed in the AD brain.73 In 2012, Ahn and co-workers used a two-photon MAO probe, which, upon enzymatic reaction, produces a fluorescent dye that can also sense Aβ plaques, to monitor a close correlation between the MAO-B activity and accumulation of Aβ plaques upon aging. A further study is necessary to understand the close correlation and also to know whether the enzyme activity is associated with the progress of AD.70

Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for MAOs

A conventional strategy to develop MAO probes is to utilize the enzymes’ oxidizing reactivity to amine neurotransmitters, which can induce subsequent chemical transformations with fluorescent changes (Figure 2d). In the development of MAO probes, two kinds of amine substrates for MAOs have been introduced to the electron-donor of ICT based dipolar dyes, which undergo enzymatic cleavage accompanied by fluorescence changes. In 2006, Wood and co-workers introduced (3-amino-propyloxy)arenes as the reactive substrates of MAOs.74 MAOs transform the propylamine moiety into the corresponding iminium ion, leading to the cleavage of the amine moiety. A different amine substrate, 4-aryloxy-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, was introduced by Castagnoli and Zhu groups.75 MAO-B oxidizes the tetrahydropyridine moiety into the corresponding dihydro-pyridinium intermediate, which subsequently undergoes a hydrolytic ether cleavage. In both cases, probes exhibited a turn-on type response due to the PET quenching effect of the amine moiety. By following similar approaches, several fluorescent probes for MAOs have been developed. But still those with practical utility are in strong demand. As mentioned above, Ahn and co-workers recently disclosed that the MAO-B activity is highly correlated with the accumulation of Aβ plaques.70 The MAO probe, upon enzymatic reaction, produced a two-photon absorbing dye, IBC 2, that is capable of visualizing Aβ plaques down to >600 μm depth in in vivo imaging. The deep imaging capability of IBC 2 is notable, considering that the reported TP probes imaged Aβ plaques only down to ∼300 μm. Moreover, IBC 2 allowed imaging of small amyloid depositions such as CAA surrounding of the blood vessels (Figure 3i).

6. Reactive Astrocytes

Recently, astrocyte-related neuropathology has gained high research interest for studying homeostasis in the AD brain, memory impair process, and AD diagnosis. Astrocytes perform many functions in the brain, including the support of the endothelial cells in forming the BBB, the provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, the maintenance of ion balance, and the repair process in the brain.76 In the AD brain, astrocytes undergo prominent changes in morphology and gene expression, leading to the disruption of synaptic connectivity and imbalance of neurotransmitter homeostasis.77,78 Moreover, in the AD brain, astrocytes near Aβ plaques become reactive (Figure 1d). Reactive astrocytes produce more putrescine, a type of polyamine degraded from toxic molecules, which is degraded into γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by MAO-B.79 Also reactive astrocytes elevate the resting Ca(II) level and enhance the intercellular Ca(II) waves, all of which may potentially lead to enhanced release of various gliotransmitters containing GABA into the extracellular space.79 GABA released into the extracellular space inhibits neuronal activity and impairs memory abilities. As a result, monitoring of unusual behavior of astrocytes along with the inflammation factor is one of the key subjects for AD-related mechanism study as well as AD diagnosis.

Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for Astrocytes

Astrocytes can be selectively stained by using fluorescent antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),80,81 a calcium-binding protein S100 beta,82 excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT1/2),83 and aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 family (ALDH1L1).84 Sulforhodamine 101 (SR101), a small molecular dye, was known to stain astrocyte selectively, but the detecting mechanism remains to be elucidated (Figure 2e).85 Staining astrocyte with SR101 is fast and gives bright fluorescence in the red region, but application to in vivo staining is limited for its high dose injection requirement and poor BBB permeability, which is plausibly due to the negatively charged character. Since then, no specific strategy to detect astrocytes has been reported, demanding further efforts in this subject.

7. Summary and Outlook

In this Outlook, we have reviewed the detection strategies of fluorescent probes for AD biomarkers, along with a summary of AD biomarkers. Even though the fluorescence imaging techniques with molecular probes are still a ways from clinical application, the in vivo study for the disease in animal models with finely designed probes contributes to our understanding of the biology of AD. We summarized demands and perspectives of fluorescent molecular probes for AD biomarkers. For in vivo imaging application of AD biomarkers, small molecular probes should meet several criteria listed below.

-

(i)

High selectivity toward the biomarker

-

(ii)

Biocompatibility (sufficient aqueous solubility, cell permeability, and low toxicity)

-

(iii)

Sufficient photostability

-

(iv)

Notable photophysical property change after binding or reaction with biomarkers

-

(v)

Excitation as well as emission wavelengths in the biological optical window

-

(vi)

BBB penetration

-

(vii)

Fast circulation in and clearance from the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (NRF-2018M3A9H3021707) and Basic Science Research Program through Korea NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03025124, NRF-2018R1D1A1B07043383). K.H.A. acknowledges the financial support from the Global Research Program (NRF-2014K1A1A2064569) through the Korea NRF funded by Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning. D.K. thanks Dr. Jonathan M. Zuidema (UC San Diego) and Ms. Jinyoung Kang (UC San Diego) for helpful discussion. Y.K. thanks DaWon Kim (Yonsei Univ.) for the kind support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-beta peptide

- APP

amyloid peptide precursor

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- NIR

near-infrared

- OPM

one-photon microscopy

- TPM

two-photon microscopy

- MMP

multiphoton microscopy

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- p-tau

hyper-phosphorylated tau peptide aggregate

- SPION

Super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

- USPION

ultra-small super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle

- Gd

gadolinium

- i.v.

intravenous

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- TPACS

two-photon absorption cross-section

- MAOs

monoamine oxidase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Methoxy-X04

1,4-bis(4′-hydroxystyryl)-2-methyoxybenzene

- FDDNP

2-(1-{6-[(2-fluoroethyl-(methyl)amino)2-naphthyl}ethylidene)-malononitrile

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- GM

Göppert-Mayer

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-poperazine-ethane-sulfonic acid)

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- HSA

human serum albumin

- RVG

rabies virus glycoprotein.

Author Contributions

# Y.W.J. and S.W.C. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Scheltens P.; Blennow K.; Breteler M. M. B.; de Strooper B.; Frisoni G. B.; Salloway S.; Van der Flier W. M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2016, 388, 505–517. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters C. L.; Bateman R.; Blennow K.; Rowe C. C.; Sperling R. A.; Cummings J. L. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15056. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A. Towards early diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 69–70. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M.; Spillantini M. G. A century of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 2006, 314, 777–781. 10.1126/science.1132814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.; Hu Y.; Yoon J. Fluorescent probes and bioimaging: alkali metals, alkaline earth metals and pH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4619–4644. 10.1039/C4CS00275J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens E. A.; Henary M.; El Fakhri G.; Choi H. S. Tissue-Specific Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1731–1740. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine H. Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 309, 274–284. 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ametamey S. M.; Honer M.; Schubiger P. A. Molecular Imaging with PET. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1501–1516. 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni G. B.; Fox N. C.; Jack C. R. Jr; Scheltens P.; Thompson P. M. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 67–77. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese T.; Sheelakumari R.; James J. S.; Mathuranath P. S. A review of neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Asia 2013, 18, 239–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W. E.; Engler H.; Nordberg A.; Wang Y.; Blomqvist G.; Holt D. P.; Bergström M.; Savitcheva I.; Huang G.-F.; Estrada S.; Ausén B.; Debnath M. L.; Barletta J.; Price J. C.; Sandell J.; Lopresti B. J.; Wall A.; Koivisto P.; Antoni G.; Mathis C. A.; Långström B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 306–319. 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A.; Frosch M. P.; Masliah E.; Hyman B. T. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a006189. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller P.; Hureau C.; Berthoumieu O. Role of Metal Ions in the self-assembly of the Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12193–12206. 10.1021/ic4003059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald J.; Riek R. Biology of amyloid: structure, function, and regulation. Structure 2010, 18, 1244–1260. 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh Y.-H.; Checler F. Amyloid precursor protein, presenilins, and α-synuclein: molecular pathogenesis and pharmacological applications in Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2002, 54, 469–525. 10.1124/pr.54.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U. C.; Deller T.; Korte M. Not just amyloid: physiological functions of the amyloid precursor protein family. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 281–298. 10.1038/nrn.2017.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggen S.; Beher D. Molecular consequences of amyloid precursor protein and presenilin mutations causing autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2012, 4, 9. 10.1186/alzrt107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepp K. P. Bioinorganic chemistry of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5193–5239. 10.1021/cr300009x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich M. Oligomeric intermediates in amyloid formation: structure determination and mechanisms of toxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 421, 427–440. 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas L.; Cerpa W.; Muñoz F.; Zanlungo S.; Alvarez A. Amyloid-β oligomers synaptotoxicity: the emerging role of EphA4/c-Abl signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1148–1159. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A.; Ojala J.; Kauppinen A.; Kaarniranta K.; Suuronen T. Inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: amyloid-β oligomers trigger innate immunity defence via pattern recognition receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 87, 181–194. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasica-Labouze J.; Nguyen P. H.; Sterpone F.; Berthoumieu O.; Buchete N.-V.; Coté S.; De Simone A.; Doig A. J.; Faller P.; Garcia A.; Laio A.; Li M. S.; Melchionna S.; Mousseau N.; Mu Y.; Paravastu A.; Pasquali S.; Rosenman D. J.; Strodel B.; Tarus B.; Viles J. H.; Zhang T.; Wang C.; Derreumaux P. Amyloid β protein and Alzheimer’s disease: when computer simulations complement experimental studies. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3518–3563. 10.1021/cr500638n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singha S.; Kim D.; Roy B.; Sambasivan S.; Moon H.; Rao A. S.; Kim J. Y.; Joo T.; Park J. W.; Rhee Y. M.; Wang T.; Kim K. H.; Shin Y. H.; Jung J.; Ahn K. H. A structural remedy toward bright dipolar fluorophores in aqueous media. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4335–4342. 10.1039/C5SC01076D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo A.; Yankner B. A. Beta-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by congo red. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 12243–12247. 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W. E.; Debnath M. L.; Pettegrew J. W. Chrysamine-G binding to Alzheimer and control brain: autopsy study of a new amyloid probe. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 541–548. 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00058-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki H.; Higuchi K.; Hosokawa M.; Takeda T. Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavine T. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 177, 244–249. 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W. E.; Bacskai B. J.; Mathis C. A.; Kajdasz S. T.; McLellan M. E.; Frosch M. P.; Debnath M. L.; Holt D. P.; Wang Y.; Hyman B. T. Imaging Aβ plaques in living transgenic mice with multiphoton microscopy and methoxy-X04, a systemically administered congo red derivative. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 61, 797–805. 10.1093/jnen/61.9.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintersteiner M.; Enz A.; Frey P.; Jaton A.-L.; Kinzy W.; Kneuer R.; Neumann U.; Rudin M.; Staufenbiel M.; Stoeckli M.; Wiederhold K.-H.; Gremlich H.-U. In vivo detection of amyloid-β deposits by near-infrared imaging using an oxazine-derivative probe. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 577–583. 10.1038/nbt1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassenko A. G.; Benzinger T. L. S.; Morris J. C. PET amyloid-beta imaging in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 370–379. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis C. A.; Mason N. S.; Lopresti B. J.; Klunk W. E. Development of positron emission tomography β-amyloid plaque imaging agents. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2012, 42, 423–432. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan N. A.; Zalesny R.; Kongsted J.; Nordberg A.; Agren H. Promising two-photon probes for in vivo detection of β amyloid deposits. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11694–11697. 10.1039/C4CC03897E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque A.; Faizi M. S. H.; Rather J. A.; Khan M. S. Next generation NIR fluorophores for tumor imaging and fluorescence-guided surgery: a review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 2017–2034. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel W. R.; Williams R. M.; Webb W. W. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1369–1377. 10.1038/nbt899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H.; Cole S. L.; Logan S.; Maus E.; Shao P.; Craft J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts A.; Ohno M.; Disterhoft J.; Van Eldik L.; Berry R.; Vassar R. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. M.; Cho B. R. Small-molecule two-photon probes for bioimaging applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5014–5055. 10.1021/cr5004425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Lee J. S.; Ha C.; Park C. B.; Yang G.; Gan W. B.; Chang Y. T. Solid-phase synthesis of styryl dyes and their application as amyloid sensors. Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 6491–6495. 10.1002/ange.200461600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Min J.; Ahn Y. H.; Namm J.; Kim E. M.; Lui R.; Kim H. Y.; Ji Y.; Wu H.; Wisniewski T.; Chang Y. T. Styryl-based compounds as potential in vivo imaging agents for β-amyloid plaques. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 1679–1687. 10.1002/cbic.200700154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo C. H.; Kim K. H.; Kim H. J.; Baik S. H.; Song H.; Kim Y. S.; Lee J.; Mook-jung I.; Kim H. M. A two-photon fluorescent probe for amyloid-β plaques in living mice. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1303–1305. 10.1039/c2cc38570h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram G. S. M.; Garai K.; Rath N. P.; Yan P.; Cirrito J. R.; Cairns N. J.; Lee J.-M.; Sharma V. Characterization of a brain permeant fluorescent molecule and visualization of Aβ parenchymal plaques, using real-time multiphoton imaging in transgenic mice. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3640–3643. 10.1021/ol501264q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Moon H.; Baik S. H.; Singha S.; Jun Y. W.; Wang T.; Kim K. H.; Park B. S.; Jung J.; Mook-Jung I.; Ahn K. H. Two-photon absorbing dyes with minimal autofluorescence in tissue imaging: application to in vivo imaging of amyloid-β plaques with a negligible background signal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6781–6789. 10.1021/jacs.5b03548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Tian Y.; Yuan P.; Li Y.; Yaseen M. A.; Grutzendler J.; Moore A.; Ran C. A bifunctional curcumin analogue for two-photon imaging and inhibiting crosslinking of amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11550–11553. 10.1039/C4CC03731F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalatsa A.; Barbu E. Carbohydrate nanoparticles for brain delivery. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2016, 130, 115–153. 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo C. H.; Sarkar A. R.; Baik S. H.; Jung T. S.; Kim J. J.; Kang H.; Mook-Jung I.; Kim H. M. A quadrupolar two-photon fluorescent probe for in vivo imaging of amyloid-β plaques. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 4600–4606. 10.1039/C6SC00355A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow E.-M.; Mandelkow E. Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006247. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla K. V.; Wegmann S.; Kopeikina K. J.; Hawkes J.; Rudinskiy N.; Andermann M. L.; Spires-Jones T. L.; Bacskai B. J.; Hyman B. T. Neurofibrillary tangle-bearing neurons are functionally integrated in cortical circuits in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 510–514. 10.1073/pnas.1318807111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippens G.; Sillen A.; Landrieu I.; Amniai L.; Sibille N.; Barbier P.; Leroy A.; Hanoulle X.; Wieruszeski J.-M. Tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Prion 2007, 1, 21–25. 10.4161/pri.1.1.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon S.; Grundke-Iqbal I.; Iqbal K. Brain levels of microtubule-associated protein tau are elevated in Alzheimer’s disease: a radioimmuno-slot-blot assay for nanograms of the protein. J. Neurochem. 1992, 59, 750–753. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwilst P.; Kim H.-R.; Seo J.; Sohn N.-W.; Cha S.-Y.; Kim Y.; Maeng S.; Shin J.-W.; Kwak J. H.; Kang C.; Kim J. S. Rational design of in vivo tau tangle-selective near-infrared fluorophores: expanding the bodipy universe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13393–13403. 10.1021/jacs.7b05878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Harada R.; Tago T.; Yoshikawa T.; Fodero-Tavoletti M.; Mulligan R. S.; Villemagne V. L.; Akatsu H.; Yamamoto T.; Arai H.; Iwata R.; Yanai K.; Kudo Y. Novel 18F-labeled arylquinoline derivatives for noninvasive imaging of tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 1420–1427. 10.2967/jnumed.112.117341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti M. T.; Furumoto S.; Taylor L.; McLean C. A.; Mulligan R. S.; Birchall I.; Harada R.; Masters C. L.; Yanai K.; Kudo Y.; Rowe C. C.; Okamura N.; Villemagne V. L. Assessing THK523 selectivity for tau deposits in Alzheimer’s disease and non–Alzheimer’s disease tauopathies. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 11–21. 10.1186/alzrt240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K.; Ono M.; Hayashi S.; Kimura H.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Mori H.; Saji H. Phenyldiazenyl benzothiazole derivatives as probes for in vivo imaging of neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease brains. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 596–600. 10.1039/c1md00034a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Hayashi S.; Matsumura K.; Kimura H.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Mori H.; Saji H. Rhodanine and thiohydantoin derivatives for detecting tau pathology in Alzheimer’s brains. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2011, 2, 269–275. 10.1021/cn200002t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C.-F.; Arteaga J.; Chen G.; Gangadharmath U.; Gomez L. F.; Kasi D.; Lam C.; Liang Q.; Liu C.; Mocharla V. P.; Mu F.; Sinha A.; Su H.; Szardenings A. K.; Walsh J. C.; Wang E.; Yu C.; Zhang W.; Zhao T.; Kolb H. C. [18F]T807, a novel tau positron emission tomography imaging agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dementia 2013, 9, 666–676. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock T. J. A.; Tuszynski J. A.; Chopra D.; Casey N.; Goldstein L. E.; Hameroff S. R.; Tanzi R. E. The zinc dyshomeostasis hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2012, 7, e33552 10.1371/journal.pone.0033552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojida A.; Sakamoto T.; Inoue M.-a.; Fujishima S.-h.; Lippens G.; Hamachi I. Fluorescent bodipy-based Zn(II) complex as a molecular probe for selective detection of neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6543–6548. 10.1021/ja9008369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-Y.; Sengupta U.; Shao P.; Guerrero-Muñoz M. J.; Kayed R.; Bai M. Alzheimer’s disease imaging with a novel tau targeted near infrared ratiometric probe. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2013, 3, 102–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Huang W.; Moir R. D.; Vanderburg C. R.; Lai B.; Peng Z.; Tanzi R. E.; Rogers J. T.; Huang X. Metal exposure and Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. J. Struct. Biol. 2006, 155, 45–51. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatta P.; Drago D.; Bolognin S.; Sensi S. L. Alzheimer’s disease, metal ions and metal homeostatic therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 346–355. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski H.; Luczkowski M.; Remelli M.; Valensin D. Copper, zinc and iron in neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and prion diseases). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2129–2141. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinello A.; Bonsignore R.; Barone G.; Keppler B. K.; Terenzi A. Metal ions and metal complexes in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 3996–4010. 10.2174/1381612822666160520115248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.-S.; Braymer J. J.; Nanga R. P. R.; Ramamoorthy A.; Lim M. H. Design of small molecules that target metal-Aβ species and regulate metal-induced Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 21990–21995. 10.1073/pnas.1006091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelieff M. G.; DeToma A. S.; Derrick J. S.; Lim M. H. The ongoing search for small molecules to study metal-associated amyloid-β species in Alzheimer’s disease. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2475–2482. 10.1021/ar500152x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D. E.; Binda C.; Wang J.; Upadhyay A. K.; Mattevi A. Molecular and mechanistic properties of the membrane-bound mitochondrial monoamine oxidases. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 4220–4230. 10.1021/bi900413g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalenheim E. G.; vonKnorring L.; Oreland L. Platelet monoamine oxidase activity as a biological marker in a Swedish forensic psychiatric population. Psychiatry Res. 1997, 69, 79–87. 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)03056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher P.; Davis J. B. The role of monoamine metabolism in oxidative glutamate toxicity. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 6394–6401. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06394.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias V.; Junn E.; Mouradian M. M. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2013, 3, 461–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S.; Abramov A. Y. Mechanism of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2012, 2012, 428010. 10.1155/2012/428010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youdim M. B.; Bakhle Y. S. Monoamine oxidase: isoforms and inhibitors in Parkinson’s disease and depressive illness. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S287–S296. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo K. C.; Ho S.-L. Monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors: implications for disease-modification in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2013, 2, 19. 10.1186/2047-9158-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Baik S. H.; Kang S.; Cho S. W.; Bae J.; Cha M.-Y.; Sailor M. J.; Mook-Jung I.; Ahn K. H. Close correlation of monoamine oxidase activity with progress of Alzheimer’s disease in mice, observed by in vivo two-photon imaging. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 967–975. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Zhang C.-W.; Chen G. Y. J.; Zhu B.; Chai C.; Xu Q.-H.; Tan E.-K.; Zhu Q.; Lim K.-L.; Yao S. Q. A sensitive two-photon probe to selectively detect monoamine oxidase B activity in Parkinson’s disease models. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3276. 10.1038/ncomms4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards G.; Messer J.; Waldvogel H. J.; Gibbons H. M.; Dragunow M.; Faull R. L. M.; Saura J. Up-regulation of the isoenzymes MAO-A and MAO-B in the human basal ganglia and pons in Huntington’s disease revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography. Brain Res. 2011, 1370, 204–214. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Beck S.; Jung J. Monitoring of monoamine oxidases as biomarkers of disease and disorder. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2018, 39, 277–278. 10.1002/bkcs.11397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Valley M. P.; Shultz J.; Hawkins E. M.; Bernad L.; Good T.; Good D.; Riss T. L.; Klaubert D. H.; Wood K. V. New bioluminogenic substrates for monoamine oxidase assays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3122–3123. 10.1021/ja058519o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.; Chen L.; Xiang Y.; Song M.; Zheng Y.; Zhu Q. An activity-based fluorogenic probe for sensitive and selective monoamine oxidase-B detection. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7164–7166. 10.1039/c2cc33089j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues H. S.; Portugal C. C.; Socodato R.; Relvas J. B. Oligodendrocyte, astrocyte, and microglia crosstalk in myelin development, damage, and repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 71. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner B.; Romanelli E.; Liberski P.; Ingold-Heppner B.; Sobottka-Brillout B.; Hartwig T.; Chandrasekar V.; Johannssen H.; Zeilhofer H. U.; Aguzzi A.; Heppner F.; Kerschensteiner M.; Becher B. Astrocyte depletion impairs redox homeostasis and triggers neuronal loss in the adult CNS. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1377–1384. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A.; Olabarria M.; Noristani H. N.; Yeh C.-Y.; Rodriguez J. J. Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 399–412. 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.; Yarishkin O.; Hwang Y. J.; Chun Y. E.; Park M.; Woo D. H.; Bae J. Y.; Kim T.; Lee J.; Chun H.; Park H. J.; Lee D. Y.; Hong J.; Kim H. Y.; Oh S.-J.; Park S. J.; Lee H.; Yoon B.-E.; Kim Y.; Jeong Y.; Shim I.; Bae Y. C.; Cho J.; Kowall N. W.; Ryu H.; Hwang E.; Kim D.; Lee C. J. GABA from reactive astrocytes impairs memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 886–896. 10.1038/nm.3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hol E. M.; Pekny M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 32, 121–130. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Zou J.; Rensing N.; Wong M. In vivo two-photon imaging of astrocytes in GFAP-GFP transgenic mice. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170005 10.1371/journal.pone.0170005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrak R. E.; Sheng J. G.; Griffin W. S. T. Correlation of astrocytic S100β expression with dystrophic neurites in amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996, 55, 273–279. 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki P.; Kim C.; Smith K.; Son D.-S.; Aschner M.; Lee E. Transcriptional regulation of the astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (EAAT1) via NF-κB and yin yang 1 (YY1). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 23725–23737. 10.1074/jbc.M115.649327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Vidensky S.; Jin L.; Jie C.; Lorenzini I.; Frankl M.; Rothstein J. D. Molecular comparison of GLT1+ and ALDH1L1+ astrocytes in vivo in astroglial reporter mice. Glia 2011, 59, 200–207. 10.1002/glia.21089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A.; Kirchhoff F.; Kerr J. N. D.; Helmchen F. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nat. Methods 2004, 1, 31–37. 10.1038/nmeth706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]