Abstract

Originally identified in studies of cellular resistance to viral infection, interferon (IFN)-γ is now known to represent a distinct member of the IFN family and plays critical roles not only in orchestrating both innate and adaptive immune responses against viruses, bacteria, and tumors, but also in promoting pathologic inflammatory processes. IFN-γ production is largely restricted to T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells and can ultimately lead to the generation of a polarized immune response composed of T helper (Th)1 CD4+ T cells and CD8+ cytolytic T cells. In contrast, the temporally distinct elaboration of IFN-γ in progressively growing tumors also promotes a state of adaptive resistance caused by the up-regulation of inhibitory molecules, such as programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor cell targets, and additional host cells within the tumor microenvironment. This review focuses on the diverse positive and negative roles of IFN-γ in immune cell activation and differentiation leading to protective immune responses, as well as the paradoxical effects of IFN-γ within the tumor microenvironment that determine the ultimate fate of that tumor in a cancer-bearing individual.

THE STRUCTURE AND BIOSYNTHESIS OF INTERFERON γ (IFN-γ)

The IFN-γ Gene

The mouse and human IFN-γ proteins are encoded by single 6-kb genes comprised of four exons and three introns located on chromosomes 10 and 12, respectively (Trent et al. 1982; Naylor et al. 1983, 1984). The 2.3 kb of DNA upstream, 1 kb of DNA downstream, and portions within of the human IFN-γ gene have all been characterized as having regulatory elements that control expression of IFN-γ (Young et al. 1989). When expressed in transgenic mice, the 5′ promoter elements were shown to have cell-type-specific regulatory capabilities in driving expression of an IFN-γ reporter construct in CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells. Binding sites for many transcription factors have been located in these regulatory elements, including Fos, Jun, GATA3, NFAT, nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and T-bet (Penix et al. 1993, 1996; Sica et al. 1997; Szabo et al. 2000). Despite the structural similarities of the mouse and human IFN-γ genes, they share only 60% homology at the genetic sequence level.

The IFN-γ Protein

The IFN-γ polypeptides from both mice and humans are approximately 160 amino acids long, but share only 40% sequence homology, a result that explains the strict species specificity displayed by the mouse and human proteins for their respective target cells (Gray and Goeddel 1982, 1983; Farrar and Schreiber 1993). Biologically active IFN-γ is a noncovalently linked homodimer consisting of two identical 17 kDa polypeptides. The individual polypeptides associate in a helical, antiparallel fashion to form a compact and globular molecule displaying a twofold axis of symmetry (Ealick et al. 1991; Farrar and Schreiber 1993). The mature molecule is glycosylated such that each mature subunit displays a molecular weight of 25 kDa yielding a 50 kDa homodimer (Ealick et al. 1991). IFN-γ glycosylation does not directly contribute to the functional activity of the mature protein but plays a role in protecting it from proteolytic degradation. The finding that the IFN-γ homodimer does not contain any covalent attachments helped explain the experimental findings that IFN-γ is particularly sensitive to extremes of both temperature and pH. Both the amino and carboxyl termini of the IFN-γ polypeptide are required for binding to the IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) and induction of biological responses. Proteolytic cleavage studies of IFN-γ revealed that amino acid residues 1–10 on the mature amino terminus are critically important for biologic activity of the molecule (Zavodny et al. 1988; Hogrefe et al. 1989). Likewise, enzymatic removal of the carboxyl-terminal 14 amino acids (residues 129–143) results in significant activity reduction (Arakawa et al. 1986; Leinikki et al. 1987). The results of these truncation experiments were further bolstered by results from experiments using blocking antibodies directed against the amino and carboxyl termini of the IFN-γ polypeptide; antibody-mediated blocking of either the amino or carboxyl termini resulted in inhibition of IFN-γ binding to IFNGR-expressing cells and IFN-γ signaling (Johnson et al. 1982; Russell et al. 1986; Jarpe and Johnson 1990). The observations that IFN-γ is a homodimer and that both the amino and carboxyl termini of the molecule are required for biological activity led to the proposal that each IFN-γ molecule interacts with two IFNGRs, which was not fully validated until the structure of the IFNGR was elucidated.

Cellular Production of IFN-γ

IFN-γ has been shown to have profound effects on both innate and adaptive immunity that facilitate host protection. However, aberrant production of IFN-γ has been associated with disease pathology, including chronic autoimmune diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes. Therefore, the initiation, timing, and amount of IFN-γ produced must be closely regulated (Schoenborn and Wilson 2007).

Natural killer (NK) cells and natural killer T (NKT) cells are the major IFN-γ-producing cells of the innate response. Mature NK cells contain epigenetic marks that open the IFNG locus leading to their constitutive expression of IFN-γ transcripts, which allows for rapid production and secretion of IFN-γ during infection or cancer (Stetson et al. 2003; Mah and Cooper 2016). NK cells can be stimulated to secrete IFN-γ through both receptor-mediated pathways and cytokine-mediated pathways. Receptor-mediated NK cell activation is the result of stronger signaling through the NK cell–activating receptors than through the NK cell inhibitory receptors (Wang and Yokoyama 1998; Smith et al. 2001). NK cell–activating receptor signaling is mediated through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs (ITAMs), which phosphorylate members of the Src family of protein tyrosine kinases. Src activation eventually leads to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38, which are critical for receptor-mediated IFN-γ release and, in turn, activate transcription factors like Fos and Jun (Schoenborn and Wilson 2007).

Cytokine-mediated NK cell activation is regulated by interleukin (IL)-12, which was first shown in experiments using Listeria monocytogenes–infected severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (Tripp et al. 1993). During early infection, macrophages secrete IL-12 that, after interacting with its receptor on NK cells, results in activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)4, and eventual activation of NF-κB. NK cell–derived IFN-γ promotes activation of macrophages leading to their increased secretion of IL-12 and thereby establishes a positive feedback loop that results in a cytokine milieu within the tissue or tumor microenvironment that favors T helper (Th)1-type immune responses (Hoshino et al. 1999; Afkarian et al. 2002; Tassi and Colonna 2005; Tassi et al. 2005). Conversely, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-10 can inhibit the production of IFN-γ by NK cells via SMAD3/4 phosphorylation, leading to inhibition of transcription from the Ifng promoter (Li et al. 2006). Indeed, when SCID splenocytes were infected with L. monocytogenes in the presence of blocking antibodies to IL-10 IFN-γ secretion was enhanced, although antibodies that neutralized IL-12 led to a complete ablation of IFN-γ production (Tripp et al. 1993).

NKT cells are activated via their T-cell receptor (TCR), which recognizes CD1d-presented lipid antigens. NKT cells are uniquely capable of producing both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines, although the mechanism by which they do this is still unknown. Although it is thought that IL-12 and IL-18 can enhance IFN-γ production by NKT cells, IL-4 receptor- and IL-12 receptor-deficient mice have fully functional NKT cells (Matsuda et al. 2006; Nagarajan and Kronenberg 2007).

Subsets of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are the producers of IFN-γ in the adaptive immune response. Although all CD8+ T cells are programmed to produce IFN-γ on activation, only Th1-differentiated CD4+ T cells produce IFN-γ efficiently. Therefore, the cytokine milieu present at the time of initial infection can determine the fate of CD4+ T cells and controls the amount of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells. Th1 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells begin to rapidly produce and secrete IFN-γ after activation, proliferation, and differentiation. IFN-γ secretion by T cells is transient, reaching its peak at approximately 24 h after cell stimulation and then returning to baseline levels (Farrar and Schreiber 1993).

IFN-γ secretion from both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can be mediated by both receptor- and cytokine-dependent mechanisms, and the cellular pathways that mediate these two mechanisms are similar to the pathways already described for NK cell activation. Following the interaction between the TCR and its cognate antigen, a variety of Src family tyrosine kinases are activated that eventually result in activation of MAPKs such as p38 and ERK, which in turn leads to the activation of transcription factors Jun and Fos that transcriptionally up-regulate IFN-γ (Kane et al. 2000). IFN-γ production by previously differentiated Th1 CD4+ and cytolytic CD8+ T cells can also occur via cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-18 (Okamura et al. 1995; Yang et al. 1999). Interestingly, the treatment of Th1-differentiated CD4+ T cells in vitro with the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 was capable of eliciting IFN-γ secretion even in the absence of TCR activation by antigen or antibodies against CD3, establishing that cytokine-mediated activation of T cells can occur in a TCR-independent manner (Yang et al. 1999). Th1 CD4+ T cells not only produce IFN-γ but are made to do so in part by IFN-γ itself. The positive feedback loop established by IFN-γ signaling during differentiation and activation of CD4+ T cells is discussed elsewhere (Negishi et al. 2017; Wallach 2017).

THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE IFN-γ RECEPTOR

The IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR) is a member of the class II cytokine receptor family and is expressed at moderate levels on nearly every cell type, except mature erythrocytes. The receptor is composed of two subunits termed IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, which show high degrees of species specificity in their capacity to interact with one another as well as their cognate ligand. Experiments using mouse–human cell fusions indicated that mouse cell reactivity against human IFN-γ was not achieved until the genes for both receptor subunits were present in the mouse cell at the same time (Jung et al. 1987; Hibino et al. 1991; Bach et al. 1997). The ∼25 kb and ∼17 kb genes for IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, respectively, are both composed of seven exons. Although the gene encoding IFNGR1 is constitutively expressed, IFNGR2 expression can be regulated in certain cell populations based on their state of differentiation (Pfizenmaier et al. 1988; Bach et al. 1995, 1997; Pernis et al. 1995).

The IFNGR1 protein is approximately 90 kDa, is responsible for the majority of ligand binding, and also plays critical roles in signal transduction (Fountoulakis et al. 1991; Farrar and Schreiber 1993). In the human IFNGR1 protein, amino acids 1–17 comprise the signal sequence, 18–245 comprise the extracellular domain, 246–266 comprise the transmembrane domain, and 267–489 create the intracellular domain. The IFNGR2 protein is approximately 62 kDa, enhances the affinity of ligand binding to receptor-expressing cells, and is also required for signal transduction (Marsters et al. 1995). The mature human IFNGR2 protein is composed of an extracellular domain consisting of amino acids 28–247, a transmembrane domain made up of amino acids 248–268 and an intracellular domain produced from amino acids 269–337. Both subunits of the IFNGR are translated in the endoplasmic reticulum and are extensively glycosylated before expression on the plasma membrane (Hershey and Schreiber 1989). Immunoprecipitation experiments of untreated or IFN-γ-treated cells indicate that IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 are not tightly associated before ligand binding, but gain signaling competency on interaction with IFN-γ (Bach et al. 1996).

Neither IFNGR subunit possesses intrinsic tyrosine phosphorylation activity, yet IFN-γ signaling occurs as a consequence of tyrosine kinase activation. Detailed deletion mutagenesis experiments aimed at elucidating the functionally important regions of IFNGR1 revealed that the vast majority of the IFNGR1 extracellular domain is required for appropriate IFN-γ binding (Fountoulakis et al. 1991). Alanine-scanning and deletion mutagenesis analyses performed on the IFNGR1 intracellular domain revealed that it contains two functionally important sequences. The first is comprised of the membrane proximal amino acids 266LPKS269, with the proline at position 267 playing the most important role in receptor function (Farrar et al. 1991; Kaplan et al. 1996). This sequence represents the constitutive point of attachment on IFNGR1 for Janus kinase (JAK)1 (Igarashi et al. 1994; Kaplan et al. 1996). The second functionally critical IFNGR1 domain is a 440YDKPH444 motif that resides in a membrane distal position closer to the carboxyl terminus of the IFNGR1 polypeptide. Within this sequence, Y440, D441, and H444 are the functionally important amino acids (Farrar et al. 1991, 1992). The tyrosine at position 440 is phosphorylated on ligation of the intact receptor and thereby nucleates the induced site of attachment on IFNGR1 for the SH2 domain on the latent, cytosolic transcription factor STAT1 (Greenlund et al. 1995). The IFNGR2 intracellular domain contains two closely spaced sequences located in the membrane-proximal portion of the polypeptide that are required for IFN-γ-induced biologic responses. Experiments involving both alanine-scanning mutagenesis and truncation of the IFNGR2 intracellular domain defined these two regions as 263PPSIP267 and 270IEEYL274 (Kotenko et al. 1995; Bach et al. 1996). These sequences form the constitutive site of attachment of the JAK2 Janus kinase on IFNGR2 (Sakatsume et al. 1995). As opposed to the functional domains within the IFNGR1 intracellular domain, no single amino acid in either of the IFNGR2 intracellular regions was observed as having a dominant functional role.

The observation that IFN-γ is a homodimeric molecule suggested that it would be able to bind to two IFNGRs. This hypothesis was supported by stoichiometry experiments showing that the IFNGR–IFN-γ complex was formed at a 2:1 ratio, indicating that two receptors are bound to every one IFN-γ homodimeric molecule (Fountoulakis et al. 1992; Greenlund et al. 1993). Additionally, expression of dominant-negative signaling mutants of IFNGR1 completely inhibits IFN-γ signaling (Dighe et al. 1993). These results suggest that functional IFN-γ signaling requires multiple heterodimeric IFNGRs working together. In 1995, the structure of IFNGR1 bound to IFN-γ was solved by X-ray crystallography. Researchers observed that, just as had been hypothesized by the previously described experiments, two IFNGR1 molecules were bound to each homodimeric molecule of IFN-γ (Walter et al. 1995). Therefore, the structure of the complete, biologically active IFNGR–IFN-γ complex consists of two IFNGR1 molecules and two IFNGR2 molecules, with one of each receptor subunit bound to each end of the IFN-γ homodimer (Fig. 1). The importance of IFNGR dimerization on ligand binding and the functionally critical regions of both the IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 intracellular domains became apparent on the elucidation of the signaling pathway activated by IFN-γ.

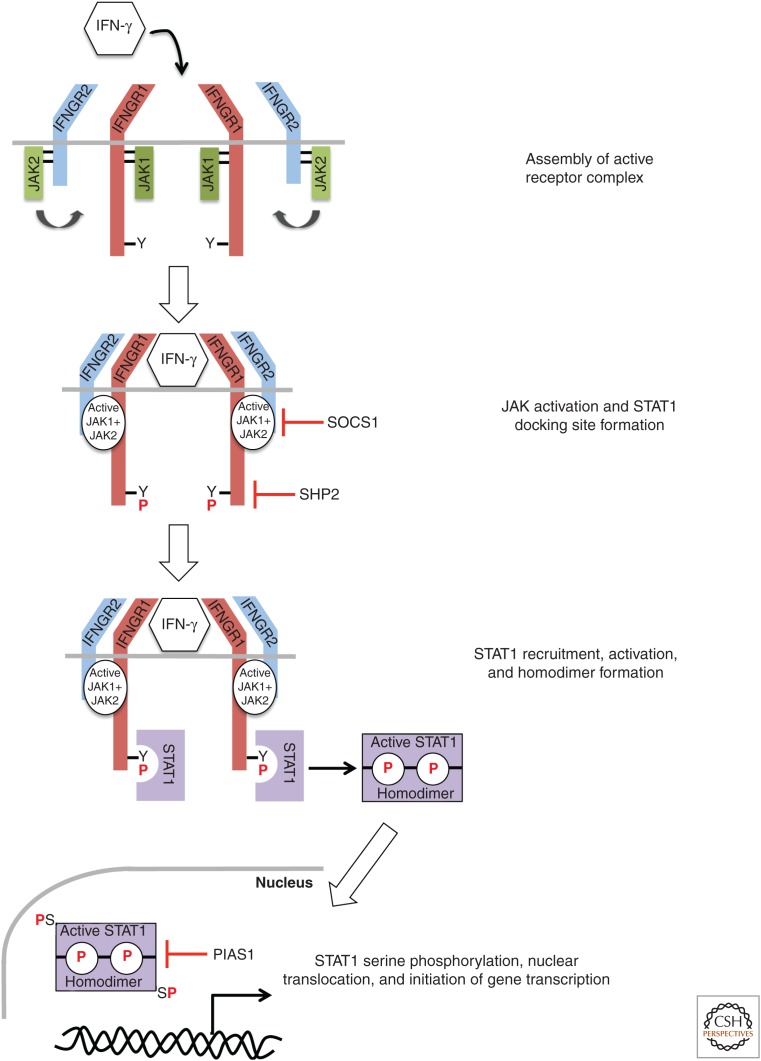

Figure 1.

Assembly of the interferon (IFN)-γ receptor (IFNGR) and activation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signaling. Binding of IFN-γ to the IFNGR complex results in tight association of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 and a reorientation of the intracellular domains of these subunits, thereby bringing their associated JAK1 and JAK2 proteins into close proximity to facilitate auto- and transphosphorylation and enzymatic activation. The activated JAK proteins then phosphorylate the intracellular domain of IFNGR1 on tyrosine 440 to create a binding site for STAT1. On JAK-mediated phosphorylation, STAT1 dissociates from its IFNGR1 tether, forms a homodimer via reciprocal interactions between the SH2 domain of one STAT1 molecule and the phosphorylated tyrosine-701 of the other, and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to γ-activated site (GAS) elements and promotes gene transcription. The multiple levels of JAK-STAT pathway negative regulation are indicated. SOCS, Suppressors of cytokine signaling; PIAS, protein inhibitor of activated STATs. (From Bach et al. 1997; adapted, with permission, from the authors.)

THE IFN-γ SIGNALING PATHWAY

The signaling pathways activated downstream from the IFNGR rely almost entirely on two families of proteins: protein tyrosine kinases that are members of the JAK family and one member of the STAT family of transcription factors (Darnell et al. 1994). This signaling pathway, known as the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, was largely elucidated by studying signaling through the distinct receptors for IFN-γ and type I IFNs. Additionally, amino acid sequence comparison of the IFNGR intracellular domain and the intracellular domain of the IL-6 receptor revealed similar motifs known to be necessary for JAK binding (Murakami et al. 1991; Tanner et al. 1995). Researchers used coimmunoprecipitation experiments to identify that JAK1 binds IFNGR1, and alanine-scanning mutagenesis identified its binding site as the functionally important 266LPKS269 motif previously described (Igarashi et al. 1994; Kaplan et al. 1996). Similar experiments were performed that showed that JAK2 binds the IFNGR2 intracellular domain at 263PPSIPLQIEEYL274, a region encompassing the functionally important motifs of IFNGR2 (Kotenko et al. 1995; Sakatsume et al. 1995; Bach et al. 1996).

Before encountering IFN-γ, JAK1 and JAK2 are constitutively bound to IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, respectively, but are not enzymatically active. On ligation, the IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 subunits form strongly associated receptor molecules (Bach et al. 1996). This reorientation of IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 bring their associated JAK proteins into close enough proximity to one another, allowing for their auto- and transphosphorylation, leading to the activation of both JAK1 and JAK2 (Bach et al. 1997). The functional role of the activated JAKs was revealed in part by the observation that mutagenesis of a single tyrosine, Y440, in the intracellular domain of IFNGR1 completely inhibited IFN-γ signaling. Furthermore, mutagenesis of Y440 also resulted in loss of IFN-γ-mediated STAT1 activation (Greenlund et al. 1994; Sakatsume et al. 1995). Finally, STAT1 could be immunoprecipitated with short peptide sequences mimicking the region around phosphorylated Y440 (Greenlund et al. 1994, 1995) but not with nonphosphorylated versions of the peptide. Together, these observations provided the experimental evidence supporting the concept that ligand-dependent JAK1 and JAK2 activation following IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 reorientation leads to phosphorylation of Y440, thereby providing a docking site for STAT1 on the IFNGR (Fig. 1).

STAT1 binds to the IFNGR through its SH2 domain. Indeed, antibodies that bind to the SH2 domain of STAT1 prevent the transcription factor from interacting with phosphopeptides that mimic phosphorylated IFNGR1 (Greenlund et al. 1995). On binding to IFNGR1, STAT1 is phosphorylated by JAK1 and JAK2 on tyrosine 701 (Bach et al. 1997). Further phosphorylation of STAT1 occurs on serine 727 by serine kinases, and is required for complete activation of STAT1 (Wen et al. 1995; Nguyen et al. 2001). Because of the dimeric nature of the ligand-activated IFNGR, two STAT1 molecules are activated for each molecule of IFN-γ bound (Fig. 1). The two STAT1 molecules form a homodimer through reciprocal interactions between the SH2 domain of one STAT1 protein and the phosphorylated tyrosine at position 701 of the second STAT1 and thereby dissociate from their receptor-binding site (Ramana et al. 2002). Oligomerized STAT1 translocates to the nucleus where it binds to specific DNA sequences called “γ-activated sites” (GASs) and performs its role as a transcriptional activator. GAS elements have the consensus sequence TTNCNNNAA, which was identified after sequence analysis of promoter regions from genes activated rapidly on treatment of cells with IFN-γ (Darnell et al. 1994; Schindler and Darnell 1995). STAT1 can associate with several other proteins to enhance its transcriptional activity, including the histone acetyl transferase CBP/p300 and breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) (Zhang et al. 1996; Ouchi et al. 2000). The genes that are targeted by the IFN-γ signaling pathway vary based on the cell type being targeted.

There are several molecular mechanisms that control signaling through the JAK-STAT pathway (Fig. 1). The most straightforward inhibitory pathway was first identified after the observation that phosphorylation of the IFNGR, JAK, and STAT are transient. A family of SH2-domain containing phosphatases called SHP proteins are constitutively associated with the IFNGR complex and induce removal of the many activating phosphorylated tyrosine residues responsible for mediating IFN-γ signaling (You et al. 1999). Indeed, treatment of SHP2−/− cells with IFN-γ results in heightened activation of JAK1 and STAT1 and ultimately results in cell death. In addition to the SHP phosphatases, there are several JAK-STAT pathway inhibitors that are up-regulated and function to negatively regulate IFN-γ signaling. The suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family of proteins is not expressed in resting cells but is rapidly up-regulated transcriptionally after exposure to IFN-γ (Endo et al. 1997; Naka et al. 1997; Starr et al. 1997). SOCS proteins mediate not only the inhibition of JAK proteins but also their ubiquitination and destruction, and SOCS1−/− mice have elevated serum levels of IFN-γ and die shortly after birth. The lethality of SOCS1 absence can be ameliorated by treatment with IFN-γ-neutralizing antibodies (Alexander et al. 1999; Marine et al. 1999; Naka et al. 2001). Finally, the protein inhibitor of activated STATs (PIAS) family of proteins is involved in directly interfering with STAT-mediated gene transcription. PIAS1 inhibits transcription downstream from STAT1 by binding to and preventing STAT1 from interacting with DNA (Liu et al. 1998).

Although the vast majority of IFN-γ signaling is mediated through the JAK-STAT pathway, other signaling pathways are activated downstream from the IFNGR. Examples of such pathways include the MAPK Pyk2 and ERK1/2 (Ramana et al. 2002). Microarray analysis has also identified genes that are up-regulated independently of STAT1 activation. For example, the CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein C/EBPβ is transcriptionally up-regulated on IFN-γ treatment in both wild-type and STAT1-null cells (Roy et al. 2000; Ramana et al. 2002). Likewise, macrophage inflammatory proteins MIP-1α and MIP-1β are up-regulated by IFN-γ regardless of STAT1 expression (Gil et al. 2001; Ramana et al. 2002).

THE ROLE OF IFN-γ IN IMMUNE CELL ACTIVATION

Macrophages

Macrophages serve a crucial role in both responding to pathogens and orchestrating the adaptive immune response through antigen processing and presentation. They also are major targets of IFN-γ’s actions. IFN-γ was the first identified macrophage-activating factor (MAF), responsible for rendering these cells capable of increased proinflammatory cytokine synthesis, enhanced phagocytosis, enhanced antigen-presenting capacity, and enhanced nonspecific cytocidal activity toward microbial pathogens and tumors (Schreiber et al. 1985). The importance of IFN-γ’s role in activating macrophages in vivo was first shown by experiments using IFN-γ-neutralizing antibodies. Mice treated with IFN-γ-neutralizing antibodies are unable to resist infection with sublethal doses of a variety of bacterial pathogens, showing the critical role that IFN-γ plays in inducing microbicidal activity in macrophages (Buchmeier and Schreiber 1985; Nacy et al. 1985; Suzuki et al. 1988).

The classically activated M1 macrophage relies on IFN-γ to activate expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which catalyzes the production of nitric oxide from l-arginine. Nitric oxide produced by macrophages downstream from IFN-γ signaling, in combination with NF-κB signaling, directly confers resistance against the growth of intracellular pathogens (Liew et al. 1990a,b). Additionally, macrophages polarized to the M1 phenotype after exposure to IFN-γ produce increased levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-12, IL-18, and IL-23, and up-regulate key proteins involved in Th1-antigen-specific responses and proimmune responses, including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, CD68, and the costimulatory proteins CD80 and CD86 (Sica and Bronte 2007; Sica and Mantovani 2012). These M1 macrophages show proinflammatory functions, enhanced antigen presentation functions, induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity in CD8+ T cells, and direct tumoricidal activities, all of which facilitate the immune elimination of tumors.

Antigen-Presenting Cells

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), like dendritic cells and macrophages, are necessary for efficient antigen presentation and activation of the adaptive immune response, in particular, CTL responses against extracellular pathogens and tumors. IFN-γ signaling influences the entire process of antigen processing and presentation, starting with the generation of the peptides that become targets for the immune system. Under homeostatic conditions, the proteasome is responsible for cleaving proteins into the shorter peptides that are loaded onto the MHC class I complex. During immune responses, the composition of the proteasome changes, creating a specialized protein degradation complex called the immunoproteasome. IFN-γ signaling in APCs results in up-regulation of the components of the immunoproteasome, including LMP1, LMP7, and MECL1 (Gaczynska et al. 1994; York and Rock 1996; Pamer and Cresswell 1998). Incorporation of these IFN-γ-inducible subunits results in alteration to the proteasome cleavage pattern and changes the repertoire of peptides available for presentation by MHC class I molecules (Gaczynska et al. 1994).

Multiple other proteins involved in antigen presentation are also up-regulated downstream from IFN-γ signaling. The transporters associated with antigen processing TAP-1 and TAP-2 are responsible for moving peptides from the cytosol where they are generated into the endoplasmic reticulum and loaded onto MHC class I molecules. Both of the TAP proteins are up-regulated after encounters with IFN-γ (Pamer and Cresswell 1998). Furthermore, expression of both MHC class I and class II proteins are increased by IFN-γ. STAT1, activated by the IFNGR, in turn activates the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1, which transcriptionally up-regulates expression of the MHC class I locus (Chang et al. 1992; Reis et al. 1992). The ability to up-regulate MHC class II is unique to IFN-γ, which does so through the up-regulation of the MHC class II transactivator CIITA and the invariant chain (Ii) (Cresswell 1994; Wolf and Ploegh 1995).

Finally, IFN-γ signaling in APCs results in the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and cytokines involved in the production of effective T-cell responses. Indeed, lack of IFN-γ signaling on mature IFNGR−/− dendritic cells leads to the reduced expression of ICAM-1, CD86, IL-1β, and IL-12p70 (Pan et al. 2004).

B Cells

B-cell proliferation and antibody class switching are both regulated by IFN-γ. The relationship between IFN-γ signaling and B-cell proliferation is complex, and the effects that IFN-γ has on B-cell division are dictated by the activation state of the B cell when it encounters IFN-γ (Jurado et al. 1989; Abed et al. 1994). Before exposure to antigen, B-cell proliferation is inhibited by IFN-γ. In contrast, IFN-γ signaling can promote B-cell division during the early proliferative response after primary antigen exposure. During later stages of proliferation and during B-cell maturation, IFN-γ again works to inhibit B-cell division.

The class of antibody produced by B cells is heavily influenced by the microenvironment that the B cell occupies during maturation. For example, Th2-polarized CD4+ T cells are involved in the generation of allergy, and the cytokines they produce (IL-4 and IL-5) promote B-cell class switching to immunoglobulin (Ig)E. The presence of Th1-polarized CD4+ T cells and the IFN-γ they produce inhibits class switching to IgE and instead promotes class switching to IgG2a (Snapper and Paul 1987; Snapper et al. 1988, 1991), the class of antibody that is particularly important for mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, which is a mechanism that can confer resistance to tumor outgrowth. In this way, IFN-γ signaling connects the type of CD4+ T-cell response present to the class of antibodies that B cells produce, and thereby facilitates the generation of a cohesive immune response.

Helper CD4+ T Cells

IFN-γ plays a critical role in the generation of Th1 CD4+ helper T cells. Although IL-12 is the canonical cytokine required to drive Th1 CD4+ T-cell activation, IFN-γ signaling is required to achieve maximum production of IFN-γ and also stabilizes the Th1 phenotype (Bradley et al. 1996). Indeed, Th1 CD4+ T cells generated in IFN-γ−/− mice continue to express the Th2 cytokine IL-4, indicating that Th1 polarization is not complete without IFN-γ signaling (Zhang et al. 2001; Agnello et al. 2003). IFN-γ signaling in CD4+ T cells results in the activation of STAT1 and its downstream transcriptional target T-bet. The T-bet transcription factor is a master regulator of the Th1 phenotype and transcriptionally up-regulates the expression of both the IL-12 receptor and IFN-γ (Lighvani et al. 2001; Afkarian et al. 2002; Agnello et al. 2003). In this way, IFN-γ establishes a positive feedback loop for its own production by Th1 CD4+ T cells and promotes the establishment of the Th1 phenotype by increasing signaling via IL-12 and the IL-12 receptor. IFN-γ signaling is also involved in actively inhibiting CD4+ T-cell differentiation into other subclasses, including Th2 and Th17. In mice, Th1 CD4+ T cells down-regulate the expression of certain IFNGR subunits and thus become IFN-γ-insensitive (Bach et al. 1995; Pernis et al. 1995). In contrast, Th2 and Th17 CD4+ T cells maintain expression of functional IFNGRs, and IFN-γ signaling in these CD4+ T-cell subsets results in an inhibition of their proliferation, leading to a net skewing of the CD4+ T-cell population toward the Th1 phenotype (Oriss et al. 1997; Harrington et al. 2006).

Regulatory CD4+ T Cells

The effects that IFN-γ has on regulatory CD4+ T-cell (Treg) function are only now beginning to be identified. It was shown recently that Treg cell suppression of effector T-cell activation was inhibited in IFN-γ-rich environments, and that this inhibition required the expression of the IFNGR on the Treg cells. Furthermore, adoptive cell transfer of IFNGR1−/− Treg cells into mice bearing B16.F10 melanoma tumors resulted in enhanced tumor incidence and decreased overall survival compared with mice that received IFN-γ-sensitive Treg cells, indicating that IFN-γ signaling is capable of inhibiting the protumorigenic effects of Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment (Overacre-Delgoffe et al. 2017). The mechanisms by which IFN-γ inhibits Treg cell function remain to be elucidated.

CD8+ T Cells

IFN-γ signaling directly regulates several aspects of CD8+ T-cell biology. Most importantly for the biological function of CD8+ T cells is the requirement for IFN-γ in the generation of cytolytic capabilities. Indeed, early experiments using recombinant protein showed that full cytolytic capability was not achieved until CD8+ T cells were exposed to IFN-γ (Siegel 1988; Maraskovsky et al. 1989). IFN-γ signaling in CD8+ T cells results in the up-regulation of the IL-2 receptor, the transcription factor T-bet, and granzyme. IL-2 responsiveness is critical for the generation of cytolytic CD8+ T cells and granzyme is responsible for mediating cytolysis of CD8+ T-cell targets. IFN-γ also regulates CD8+ T-cell proliferation in either a positive or negative manner following antigen exposure (Siegel 1988; Maraskovsky et al. 1989; Haring et al. 2005).

CANCER IMMUNOEDITING: AN IFN-γ-DRIVEN PROCESS LEADING TO HOST PROTECTION AND SCULPTING OF TUMOR IMMUNOGENICITY

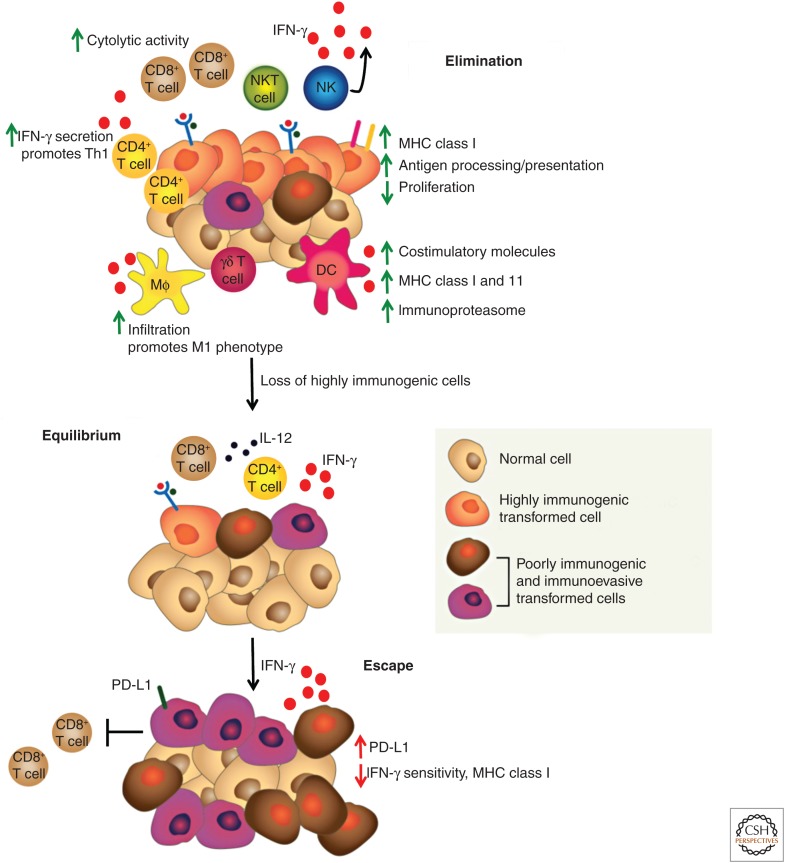

The process known as cancer immunoediting best exemplifies the actions of IFN-γ in the antitumor response (Fig. 2). “Cancer immunoediting” represents an evolution of the older and more controversial concept of cancer immunosurveillance in which the adaptive immune system was thought to play a purely protective role in controlling tumor outgrowth. “Cancer immunoediting” acknowledges this protective function of adaptive immunity but now emphasizes that immune control of tumor outgrowth is a result of the collaborative actions of cells of both innate and adaptive immunity and that cancer outgrowth can be controlled either by immune-mediated destruction of cancer cells (elimination phase) or by maintaining residual cancer cells in a state of immune-mediated dormancy (equilibrium phase). Tumor cells that transit through these two stages are subjected to severe immune-mediated selection pressures that lead to the removal of highly immunogenic tumor cell clones expressing strong tumor antigens and the outgrowth of tumor cells that are less immunogenic, and therefore are more fit to survive in an immunocompetent host (escape phase). Thus, the cancer immunoediting concept stresses both the host-protective and tumor-sculpting actions of immunity and explains, at least in part, how cancer can form in an immunocompetent individual.

Figure 2.

Interferon (IFN)-γ influences all stages of tumor immunoediting. Tumor immunoediting involves three stages: (1) elimination, in which the immune system recognizes and destroys tumor cells expressing strong neoantigens; (2) equilibrium, in which the immune system controls the outgrowth of remaining immunogenic tumor cells by manifesting in them a state of immune-mediated dormancy; and (3) escape, in which the immune system can no longer control the outgrowth of edited tumor cells resulting in the progressive outgrowth of clinically apparent tumors and the establishment of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. The roles played by IFN-γ are highlighted, with green arrows indicating its immune-stimulatory roles and red arrows indicating its immune-suppressive roles. NKT, Natural killer T cells; NK, natural killer; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; DC, dendritic cell; PD-L1, programmed-death ligand 1. (From Vesely et al. 2011; adapted, with permission, from the authors.)

Elimination

The elimination phase of cancer immunoediting is critically dependent on the activity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that are reactive against tumor antigens. Early observations showed that tumors generated in immunodeficient Rag2−/− mice were more readily rejected, and thus more immunogenic, when retransplanted into naïve syngeneic immunocompetent mice than tumors generated in wild-type mice. Additionally, Rag2−/− mice developed more tumors at a faster rate than their wild-type counterparts (Shankaran et al. 2001). These results not only reconfirmed the hypothesis that the immune system was capable of restraining tumor growth, but also indicated that the immune system was responsible for shaping tumor immunogenicity and suggested that T cells played a critical role in this process.

Subsequent use of next-generation sequencing technologies to identify the expressed mutations in tumors derived from Rag2−/− mice established that T cells do in fact generate antigen-specific responses against tumor-specific mutant neoantigens. Specifically, a foundational study in 2012 conducted on the d42m1 methylcholanthrene-A (MCA) sarcoma line showed that CD8+ T-cell responses where generated against a tumor-specific MHC class I–restricted mutation in the spectrin β2 protein (Matsushita et al. 2012). Subsequent experiments in wild-type mice found that d42m1 tumor cell variants that escaped immune elimination lacked expression of this strong neoantigen. Mixing differentially labeled mutant spectrin β2-expressing tumor cells and cells lacking mutant spectrin β2 resulted in CD8+ T-cell-dependent outgrowth only of cells lacking the neoantigen, indicating that CD8+ T cells are responsible for eliminating tumor cells expressing strong neoantigens (Matsushita et al. 2012). Similar studies were also performed using oncogene-driven tumor models expressing the model antigens OVA and SIY, and further showed that outgrown tumors in wild-type mice lacked expression of T-cell-targetable antigens (DuPage et al. 2012). Although the elimination phase of cancer immunoediting is most well documented in mouse models, recent reports from human patients have detailed the elimination of neoantigen-expressing cells. Indeed, recurrent metastatic lesions from patients with melanoma and cervical cancer who were treated with adoptive cell transfer showed loss of neoantigen expression compared with the neoantigen repertoire observed in the primary lesions (Verdegaal et al. 2016; Stevanović et al. 2017). Together, the results from experiments in mouse models and recent observations in humans establish that immune-mediated tumor elimination is the process by which the adaptive immune system recognizes and eliminates tumor cells based on their expression of strong tumor antigens.

The first indication that endogenous IFN-γ was necessary in the elimination phase was observed from a series of experiments performed on Meth A fibrosarcomas induced after treatment with MCA, and predates the suggestion of the tumor immunoediting hypothesis (Dighe et al. 1994). Subcutaneous transplantation of Meth A tumors into naïve syngeneic, immunocompetent mice led to tumor progression and outgrowth. However, these progressively growing tumors could be completely eliminated via immune-dependent mechanisms following treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Although it was known that LPS-induced rejection of Meth A occurred via TNF-α-dependent mechanisms, a striking observation made in 1994 showed that rejection was also blocked in the presence of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies specific for IFN-γ (Dighe et al. 1994). This was an important indication that host IFN-γ plays an important role in generating antitumor immune responses that can lead to complete tumor elimination in mouse models.

Although the above experiment showed that host-derived IFN-γ is necessary in promoting antitumor immune responses against transplantable Meth A sarcomas, it was important to determine whether host IFN-γ signaling was also necessary in driving elimination of primary tumors developing in the host. To address this question, tumor formation was compared between MCA-treated, IFN-γ-insensitive mice lacking either IFNGR1 (IFNGR1−/−) or Stat1 (Stat1−/−) and sex-, age-, and strain-matched wild-type mice (Kaplan et al. 1998). Importantly, a higher percentage of IFNGR1−/− and Stat1−/− mice developed tumors than wild-type mice following treatment, and the tumors from the IFN-γ-insensitive mice developed more rapidly. These experiments showed the role of IFN-γ signaling in host cells in preventing primary tumor development within mice (Kaplan et al. 1998).

Because of the demonstration that IFN-γ signaling within the host was important during tumor elimination, the requirement for IFN-γ signaling in the tumor cells was then examined. Using the transplantable Meth A tumors described above, IFN-γ sensitivity of the tumor cells was ablated by enforced expression of a truncated dominant-negative mutant form of the IFNGR1 protein (Dighe et al. 1994). Although both IFN-γ-sensitive and -insensitive tumors grew progressively in immunodeficient hosts, wild-type mice showed more rapid growth of IFN-γ-insensitive Meth A tumors compared with control IFN-γ-sensitive tumors. Even more importantly, IFN-γ-insensitive Meth A tumors no longer regressed after LPS treatment (Dighe et al. 1994). Together, this work established that the immune system could detect and respond to tumor cells and indicated that IFN-γ signaling in both the host and the tumor cells is required for the control of tumor growth (Dighe et al. 1994; Kaplan et al. 1998).

The effects of IFN-γ in the tumor environment during the elimination phase of immunoediting are predominantly antitumorigenic (Fig. 2). Innate lymphocytes (e.g., NK and NKT cells and γδ T cells) are the earliest sources of IFN-γ to enter the tumor microenvironment. In the C57BL/6 background, NK and NKT cells are necessary in generating effective antitumor immune responses, as shown in MCA experiments in mice lacking NK or NKT cells. NK-cell-deficient mice develop tumors more frequently and rapidly compared with wild-type mice (O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Guillerey and Smyth 2016). Therefore, these innate cell subsets are important in establishing the cytokine milieu that promotes effective antitumor T-cells responses.

The presence of IFN-γ in the tumor milieu during elimination is an important factor in establishing a nonpermissive microenvironment. Indeed, the extent to which tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are exposed to IFN-γ is partially responsible for polarizing TAMs to either the protumorigenic M2 or myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) phenotypes versus the antitumorigenic M1 phenotype (Sica and Bronte 2007; Sica and Mantovani 2012). Although it is now appreciated that macrophage polarization in vivo occurs more along a gradient than stark M1 versus M2 phenotypes, it is generally accepted that IFN-γ-exposed macrophages are more capable of controlling tumor cell outgrowth either directly or via promoting the development of helper CD4+ and CTL CD8+ T-cell responses through the secretion of cytokines and efficient antigen presentation via MHC class II (Lewis and Pollard 2006; Caux et al. 2016). As tumors progress, however, the alternatively activated M2 macrophage and MDSC becomes more predominant, resulting in immune suppression. Indeed, reprogramming M2 macrophages or MDSCs toward an IFN-γ-experienced M1 phenotype has been suggested as a potential tumor immunotherapeutic approach (Noy and Pollard 2014).

In addition to creating a proinflammatory microenvironment, IFN-γ signaling plays major roles in enhancing tumor immunogenicity. As discussed previously, IFN-γ has been shown to alter components of the antigen processing and presentation pathway leading to an altered epitope repertoire and up-regulation of MHC class I and class II and on the surface of APCs (Chang et al. 1992; Reis et al. 1992; Gaczynska et al. 1994). IFN-γ-mediated enhancement of MHC class I expression also occurs on tumor cells (Shankaran et al. 2001; Ikeda et al. 2002). The net result of these changes is a tumor environment containing APCs fully capable of activating the adaptive immune response and tumor cells that are targetable through MHC class I–dependent presentation of antigens (Fig. 2).

The IFN-γ-dependent establishment of a proinflammatory tumor environment and the enhanced presentation of antigens promotes the development of the adaptive antitumor response. Recent results have indicated that IFN-γ in the tumor microenvironment inhibits the activities of CD4+ Treg cells (Overacre-Delgoffe et al. 2017). At the same time, the presence of IL-12 secreted by cells like M1 macrophages and the up-regulation of MHC class II promotes the development of a Th1-polarized CD4+ T-cell response. In turn, IL-2 and IFN-γ secreted by Th1 CD4+ T cells promote the development of completely functional cytolytic CD8+ T cells that are capable of directly lysing MHC class I–expressing tumor cells. Together, these IFN-γ-mediated alterations produce a tumor microenvironment composed of cell subsets from both the innate and adaptive immune system that is decidedly antitumorigenic (Fig. 2).

Equilibrium

After elimination of highly immunogenic tumor cell clones, the immune system is capable of maintaining residual, less immunogenic tumor cell clones in a state of growth dormancy. This is the hallmark of the equilibrium phase of cancer immunoediting. The molecular mechanisms that drive immune-mediated tumor dormancy have been difficult to elucidate given the challenges of modeling the equilibrium phase in mouse models. However, several successful studies have highlighted the importance of adaptive immunity and the requirement for IFN-γ in this process.

The equilibrium phase was experimentally documented using a modification to the primary MCA-mediated tumorigenesis protocol described above, except that large groups of wild-type mice were treated with a low dose of MCA, resulting in only 20% of the treated animals developing tumors (Koebel et al. 2007). Mice that were free of clinically apparent tumors at the 200-day time point were divided into two groups. One group received control monoclonal antibody, whereas the second group was rendered immunodeficient by treatment with a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies that either depleted critical immune cell populations such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and/or blocked critical cytokines such as IFN-γ. Tumor outgrowth in the two groups was then observed for an additional 100-day period. Although tumor outgrowth was extremely rare in mice treated with control mAb, 40%–50% of the mice in groups treated with mAb that ablated or depleted adaptive immunity (e.g., mAb that neutralized IL-12 or IFN-γ or depleted CD4+ or CD8+ T cells) showed the rapid appearance of tumors at the original site of MCA injection (Koebel et al. 2007; Teng et al. 2012). Interestingly, mAbs that blocked innate immunity were not effective. Additional experiments showed that tumor antigen-specific T cells were capable of establishing tumor cell dormancy in the inducible RIP1-Tag2 model of pancreatic cancer. Treatment of mice with neutralizing antibodies against IFN-γ prevented the induction of tumor dormancy (Müller-Hermelink et al. 2008). Together, these results showed that maintenance of equilibrium was a sole function of adaptive immunity, and that IFN-γ signaling is required for the maintenance of tumor dormancy.

Case studies in human renal transplant patients have also revealed that immunosuppressed individuals receiving organ transplants can develop tumors that are of donor origin. In one particularly illuminating study, two transplant recipients each received a kidney isolated from the same cadaver donor (MacKie et al. 2003). Both recipients later returned to the clinic with fulminant secondary malignant melanoma. Neither recipient was found to have a primary lesion. When the clinical history of the donor was inspected, it was found that she was diagnosed with melanoma 16 years before her death and, after treatment, had been considered cured. However, the findings imply that the transplanted kidneys from the cadaver donor may have contained donor-derived tumor cells held in equilibrium by the donor’s adaptive immune system (MacKie et al. 2003). On transfer into a “naïve” recipient who is immunosuppressed, the immune pressure keeping the donor tumor cells in equilibrium is removed thereby permitting the donor tumor cells to grow progressively in the recipient patient.

Escape

A tumor that is progressively growing has circumvented both the elimination and equilibrium phases of tumor immunoediting and has now reached the escape phase. Thus, the tumor sculpting actions of immunity that can occur in the elimination and equilibrium phases explain, in part, the reduced immunogenicity of tumors entering the escape phase. Researchers have characterized two general mechanisms through which these tumors now escape immune detection: adaptive immune resistance and acquired immune resistance (Pardoll 2012). Both mechanisms of escape incorporate IFN-γ signaling or its downstream targets, and the effects of IFN-γ during immune escape are generally protumorigenic (Fig. 2).

Adaptive immune resistance is based on the ability of IFN-γ signaling to up-regulate the expression of membrane-bound immune inhibitory molecules, namely, programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1), on the surface of tumor cells (Pardoll 2012). In addition to observing that treatment of human tumor cell lines with IFN-γ in vitro results in the up-regulation of PD-L1, similar observations have now been made for tumor cells and myeloid cells in close proximity to infiltrating immune cells producing IFN-γ in vivo (Taube et al. 2012; Noguchi et al. 2017). PD-L1 expressed on tumor cells can bind to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) expressed on activated CD8+ T cells and stimulate apoptotic T-cell death in vivo and in vitro (Dong et al. 2002). Therefore, IFN-γ-mediated up-regulation of PD-L1 on tumor cells results in the inhibition of antitumor CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity and enhanced tumor cell survival (Fig. 2). Indeed, blocking PD1–PD-L1 interactions with monoclonal antibodies inhibits this adaptive immune resistance and results in enhanced antitumor immunity and tumor rejection (Dong et al. 2002). These observations led the way to the development of immune checkpoint blockade therapies based on the mAb targeting of either PD1 or PD-L1. Importantly, the up-regulation of PD-L1 in response to IFN-γ occurs on both tumor cells and normal cells and does not require cellular transformation to occur (Taube et al. 2012).

In addition to the IFN-γ-mediated up-regulation of PD-L1, increased expression of several other inhibitory surface molecules in microenvironments with an activated immune response have been observed. Indeed, prolonged signaling through the TCR leads to up-regulation of CTLA-4 on T cells, which formed the basis for all current immune checkpoint blockade therapies (Leach et al. 1996). Additionally, a recent publication highlighted the compensatory action of TIM-3 up-regulation in the tumor microenvironment in mediating immune escape following the use of PD-1 blockade in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma (Koyama et al. 2016). Likewise, up-regulation of the recently characterized inhibitory molecule VISTA was observed in prostate cancer patients treated with ipilimumab (Gao et al. 2017). Although the up-regulation of these other immune inhibitory molecules is not directly mediated by IFN-γ signaling, their presence in the tumor microenvironment is an important mechanism of adaptive immune resistance.

As previously discussed, IFN-γ signaling in tumor cells is of critical importance to expression of tumor immunogenicity. Additionally, the IFN-γ signaling pathway up-regulates proteins involved in arresting the cell cycle (like p21 and p27), and caspase-1, a major component of the apoptotic pathway, the net result of which is decreased tumor cell viability (Chin et al. 1997; Mandal et al. 1998; Ikeda et al. 2002). Given these effects, it is not surprising that tumor cells expressing the dominant negative IFNGR1 protein grew more aggressively than tumors with intact IFNGR signaling. Furthermore, human melanoma and lung tumor cell lines also display significant reductions in or complete loss of sensitivity to IFN-γ based on a failure to up-regulate MHC class I after stimulation (Kaplan et al. 1998). These early observations generated the hypothesis that tumor cells that inactivate the IFN-γ signaling pathway will be less prone to detection by the immune system.

As opposed to adaptive immune resistance, acquired immune resistance involves the generation of additional mutations to knock out the IFN-γ signaling pathway or its downstream targets in a tumor-cell-intrinsic manner. This functional state is sometimes observed on tumor relapse or recurrence following treatment with immune therapies (Pardoll 2012; Sharma et al. 2017). The experimental evidence for acquired adaptive resistance was reported as early as 1998, when it was observed that certain IFN-γ-insensitive human lung adenocarcinoma lines contained defects in IFNGR1, JAK1, or JAK2 (Kaplan et al. 1998). Recent clinical trials using immune checkpoint blockade therapies in human patients with melanoma have highlighted additional mechanisms for acquired resistance. One group of researchers was studying the molecular mechanisms of relapse after treatment with αPD1 (Zaretsky et al. 2016). Whole-exome sequencing was used to compare the patients’ relapsed tumors to their tumors before treatment. Like the 1998 study, two of the patients’ tumors acquired loss-of-function mutations in JAK1 or JAK2. Another patient displayed a truncating mutation in β2 microglobulin (B2M), an accessory protein in the antigen presentation pathway that is required for surface expression of MHC class I (Zaretsky et al. 2016). In another report, longitudinal examination of multiple recurrent melanoma metastases also revealed acquisition of mutations in B2M that resulted in loss of MHC class I expression on the surface of tumor cells (Zhao et al. 2016). These observations from clinical trials indicate that for tumors to escape an enhanced immune response generated by immune checkpoint blockade therapy they must acquire mutations that make them resistant to the biological impacts of IFN-γ signaling (Fig. 2).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Work over the last 30 years has revealed the critical functions of immunity in preventing and shaping cancer and the critical roles that IFN-γ plays in this process. The impacts of IFN-γ on tumor–immune system interaction were originally viewed as exclusively antitumor, because this pleotropic cytokine can have antiproliferative effects on tumor cells, promote myeloid cell activation and antigen presentation, induce directed cellular migration indirectly through production of a variety of chemokines, and facilitate CD4+ T-cell polarization to Th1 and maturation of CD8+ T cells into cytolytic T cells. However, it is now appreciated that IFN-γ also induces paradoxical responses in tumor cells and host cells that facilitate tumor outgrowth. IFN-γ drives the up-regulation of PD-L1 on tumor cells and host myeloid cells and promotes expression of the immunosuppressive metabolite IDO in these cells, thereby helping to establish a state of adaptive resistance that leads to suppression of tumor-specific T cells and formation of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. It is important to realize that these antitumor and protumor effects of IFN-γ are separated temporally and therefore we still have a lot to learn about the timing and quantitative relationships that differentially drive IFN-γ’s antitumor versus protumor effects. Thus, even though we now have a much better picture of IFN-γ’s importance in natural and therapeutic immune responses to cancer, we still have much work to do to learn how to modulate these effects to improve cancer immunotherapy efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.D.S receives research support from the National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA043059, RO1 CA190700, U01CA141541), the Cancer Research Institute, the WWWW Foundation, the Siteman Cancer Center/Barnes-Jewish Hospital (Cancer Frontier Fund), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Stand Up to Cancer. E.A. and D.M.L. are supported by a postdoctoral training grant (T32 CA00954729) from the National Cancer Institute. D.M.L. is supported by a postdoctoral training grant (Irvington Postdoctoral Fellowship) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Editors: Warren J. Leonard and Robert D. Schreiber

Additional Perspectives on Cytokines available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Abed NS, Chace JH, Fleming AL, Cowdery JS. 1994. Interferon-γ regulation of B lymphocyte differentiation: Activation of B cells is a prerequisite for IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of B cell differentiation. Cell Immunol 153: 356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afkarian M, Sedy JR, Yang J, Jacobson NG, Cereb N, Yang SY, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. 2002. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naïve CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol 3: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnello D, Lankford CSR, Bream J, Morinobu A, Gadina M, O’Shea JJ, Frucht DM. 2003. Cytokines and transcription factors that regulate T helper cell differentiation: New players and new insights. J Clin Immunol 23: 147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander WS, Starr R, Fenner JE, Scott CL, Handman E, Sprigg NS, Corbin JE, Cornish AL, Darwiche R, Owczarek CM, et al. 1999. SOCS1 is a critical inhibitor of interferon γ signaling and prevents the potentially fatal neonatal actions of this cytokine. Cell 98: 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa T, Hsu YR, Parker CG, Lai PH. 1986. Role of polycationic C-terminal portion in the structure and activity of recombinant human interferon-γ. J Biol Chem 261: 8534–8539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Ashkenazi A, Aguet M, Murphy KM, Schreiber RD. 1995. Ligand-induced autoregulation of IFN-γ receptor β chain expression in T helper cell subsets. Science 270: 1215–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Tanner JW, Marsters S, Ashkenazi A, Aguet M, Shaw AS, Schreiber RD. 1996. Ligand-induced assembly and activation of the γ interferon receptor in intact cells. Mol Cell Biol 16: 3214–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Aguet M, Schreiber RD. 1997. The IFN γ receptor: A paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol 15: 563–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley LM, Dalton DK, Croft M. 1996. A direct role for IFN-γ in regulation of Th1 cell development. J Immunol 157: 1350–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier NA, Schreiber RD. 1985. Requirement of endogenous interferon-γ production for resolution of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 82: 7404–7408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux C, Ramos RN, Prendergast GC, Bendriss-Vermare N, Ménétrier-Caux C. 2016. A milestone review on how macrophages affect tumor growth. Cancer Res 76: 6439–6442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Hammer J, Loh JE, Fodor WL, Flavell RA. 1992. The activation of major histocompatibility complex class I genes by interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1). Immunogenetics 35: 378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin YE, Kitagawa M, Kuida K, Flavell RA, Fu XY. 1997. Activation of the STAT signaling pathway can cause expression of caspase 1 and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 17: 5328–5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell P. 1994. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu Rev Immunol 12: 259–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JE, Kerr IM, Stark GR. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264: 1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighe AS, Farrar MA, Schreiber RD. 1993. Inhibition of cellular responsiveness to interferon-γ (IFNγ) induced by overexpression of inactive forms of the IFNγ receptor. J Biol Chem 268: 10645–10653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighe AS, Richards E, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. 1994. Enhanced in vivo growth and resistance to rejection of tumor cells expressing dominant negative IFN γ receptors. Immunity 1: 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, et al. 2002. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med 8: 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPage M, Mazumdar C, Schmidt LM, Cheung AF, Jacks T. 2012. Expression of tumour-specific antigens underlies cancer immunoediting. Nature 482: 405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealick SE, Cook WJ, Vijay-Kumar S, Carson M, Nagabhushan TL, Trotta PP, Bugg CE. 1991. Three-dimensional structure of recombinant human interferon-γ. Science 252: 698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo TA, Masuhara M, Yokouchi M, Suzuki R, Sakamoto H, Mitsui K, Matsumoto A, Tanimura S, Ohtsubo M, Misawa H, et al. 1997. A new protein containing an SH2 domain that inhibits JAK kinases. Nature 387: 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MA, Schreiber RD. 1993. The molecular cell biology of interferon-γ and its receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 11: 571–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MA, Fernandez-Luna J, Schreiber RD. 1991. Identification of two regions within the cytoplasmic domain of the human interferon-γ receptor required for function. J Biol Chem 266: 19626–19635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar MA, Campbell JD, Schreiber RD. 1992. Identification of a functionally important sequence in the C terminus of the interferon-γ receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 11706–11710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis M, Lahm HW, Maris A, Friedlein A, Manneberg M, Stueber D, Garotta G. 1991. A 25-kDa stretch of the extracellular domain of the human interferon γ receptor is required for full ligand binding capacity. J Biol Chem 266: 14970–14977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis M, Zulauf M, Lustig A, Garotta G. 1992. Stoichiometry of interaction between interferon γ and its receptor. Eur J Biochem 208: 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaczynska M, Rock KL, Spies T, Goldberg AL. 1994. Peptidase activities of proteasomes are differentially regulated by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded genes for LMP2 and LMP7. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 9213–9217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Ward JF, Pettaway CA, Shi LZ, Subudhi SK, Vence LM, Zhao H, Chen J, Chen H, Efstathiou E, et al. 2017. VISTA is an inhibitory immune checkpoint that is increased after ipilimumab therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Nat Med 23: 551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MP, Bohn E, O’Guin AK, Ramana CV, Levine B, Stark GR, Virgin HW, Schreiber RD. 2001. Biologic consequences of Stat1-independent IFN signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 6680–6685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PW, Goeddel DV. 1982. Structure of the human immune interferon gene. Nature 298: 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PW, Goeddel DV. 1983. Cloning and expression of murine immune interferon cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 80: 5842–5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlund AC, Schreiber RD, Goeddel DV, Pennica D. 1993. Interferon-γ induces receptor dimerization in solution and on cells. J Biol Chem 268: 18103–18110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlund AC, Farrar MA, Viviano BL, Schreiber RD. 1994. Ligand-induced IFN γ receptor tyrosine phosphorylation couples the receptor to its signal transduction system (p91). EMBO J 13: 1591–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlund AC, Morales MO, Viviano BL, Yan H, Krolewski J, Schreiber RD. 1995. Stat recruitment by tyrosine-phosphorylated cytokine receptors: An ordered reversible affinity-driven process. Immunity 2: 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillerey C, Smyth MJ. 2016. NK cells and cancer immunoediting. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 395: 115–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring JS, Corbin GA, Harty JT. 2005. Dynamic regulation of IFN-γ signaling in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells responding to infection. J Immunol 174: 6791–6802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Weaver CT. 2006. Expanding the effector CD4 T-cell repertoire: The Th17 lineage. Curr Opin Immunol 18: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey GK, Schreiber RD. 1989. Biosynthetic analysis of the human interferon-γ receptor. Identification of N-linked glycosylation intermediates. J Biol Chem 264: 11981–11988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino Y, Mariano TM, Kumar CS, Kozak CA, Pestka S. 1991. Expression and reconstitution of a biologically active mouse interferon γ receptor in hamster cells. Chromosomal location of an accessory factor. J Biol Chem 266: 6948–6951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogrefe HH, McPhie P, Bekisz JB, Enterline JC, Dyer D, Webb DS, Gerrard TL, Zoon KC. 1989. Amino terminus is essential to the structural integrity of recombinant human interferon-γ. J Biol Chem 264: 12179–12186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Tsutsui H, Kawai T, Takeda K, Nakanishi K, Takeda Y, Akira S. 1999. Cutting edge: Generation of IL-18 receptor-deficient mice: Evidence for IL-1 receptor-related protein as an essential IL-18 binding receptor. J Immunol 162: 5041–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Garotta G, Ozmen L, Ziemiecki A, Wilks AF, Harpur AG, Larner AC, Finbloom DS. 1994. Interferon-γ induces tyrosine phosphorylation of interferon-γ receptor and regulated association of protein tyrosine kinases, Jak1 and Jak2, with its receptor. J Biol Chem 269: 14333–14336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. 2002. The roles of IFNγ in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13: 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarpe MA, Johnson HM. 1990. Topology of receptor binding domains of mouse IFN-γ. J Immunol 145: 3304–3309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HM, Langford MP, Lakhchaura B, Chan TS, Stanton GJ. 1982. Neutralization of native human γ interferon (HuIFNγ) by antibodies to a synthetic peptide encoded by the 5′ end of HuIFNγ cDNA. J Immunol 129: 2357–2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung V, Rashidbaigi A, Jones C, Tischfield JA, Shows TB, Pestka S. 1987. Human chromosomes 6 and 21 are required for sensitivity to human interferon γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 4151–4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado A, Carballido J, Griffel H, Hochkeppel HK, Wetzel GD. 1989. The immunomodulatory effects of interferon-γ on mature B-lymphocyte responses. Experientia 45: 521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane LP, Lin J, Weiss A. 2000. Signal transduction by the TCR for antigen. Curr Opin Immunol 12: 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH, Greenlund AC, Tanner JW, Shaw AS, Schreiber RD. 1996. Identification of an interferon-γ receptor α chain sequence required for JAK-1 binding. J Biol Chem 271: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH, Shankaran V, Dighe AS, Stockert E, Aguet M, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. 1998. Demonstration of an interferon γ-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 7556–7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebel CM, Vermi W, Swann JB, Zerafa N, Rodig SJ, Old LJ, Smyth MJ, Schreiber RD. 2007. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature 450: 903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotenko SV, Izotova LS, Pollack BP, Mariano TM, Donnelly RJ, Muthukumaran G, Cook JR, Garotta G, Silvennoinen O, Ihle JN. 1995. Interaction between the components of the interferon γ receptor complex. J Biol Chem 270: 20915–20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, Herter-Sprie GS, Buczkowski KA, Richards WG, Gandhi L, Redig AJ, Rodig SJ, Asahina H, et al. 2016. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat Commun 7: 10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. 1996. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 271: 1734–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinikki PO, Calderon J, Luquette MH, Schreiber RD. 1987. Reduced receptor binding by a human interferon-γ fragment lacking 11 carboxyl-terminal amino acids. J Immunol 139: 3360–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CE, Pollard JW. 2006. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res 66: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AKL, Flavell RA. 2006. Transforming growth factor-β regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 24: 99–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew FY, Li Y, Millott S. 1990a. Tumor necrosis factor-α synergizes with IFN-γ in mediating killing of Leishmania major through the induction of nitric oxide. J Immunol 145: 4306–4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew FY, Millott S, Parkinson C, Palmer RM, Moncada S. 1990b. Macrophage killing of Leishmania parasite in vivo is mediated by nitric oxide from l-arginine. J Immunol 144: 4794–4797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighvani AA, Frucht DM, Jankovic D, Yamane H, Aliberti J, Hissong BD, Nguyen BV, Gadina M, Sher A, Paul WE, et al. 2001. T-bet is rapidly induced by interferon-γ in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 15137–15142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Liao J, Rao X, Kushner SA, Chung CD, Chang DD, Shuai K. 1998. Inhibition of Stat1-mediated gene activation by PIAS1. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 10626–10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKie RM, Reid R, Junor B. 2003. Fatal melanoma transferred in a donated kidney 16 years after melanoma surgery. N Engl J Med 348: 567–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah AY, Cooper MA. 2016. Metabolic regulation of natural killer cell IFN-γ production. Crit Rev Immunol 36: 131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Bandyopadhyay D, Goepfert TM, Kumar R. 1998. Interferon-induces expression of cyclin-dependent kinase-inhibitors p21WAF1 and p27Kip1 that prevent activation of cyclin-dependent kinase by CDK-activating kinase (CAK). Oncogene 16: 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraskovsky E, Chen WF, Shortman K. 1989. IL-2 and IFN-γ are two necessary lymphokines in the development of cytolytic T cells. J Immunol 143: 1210–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marine JC, Topham DJ, McKay C, Wang D, Parganas E, Stravopodis D, Yoshimura A, Ihle JN. 1999. SOCS1 deficiency causes a lymphocyte-dependent perinatal lethality. Cell 98: 609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsters SA, Pennica D, Bach E, Schreiber RD, Ashkenazi A. 1995. Interferon γ signals via a high-affinity multisubunit receptor complex that contains two types of polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92: 5401–5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda JL, Zhang Q, Ndonye R, Richardson SK, Howell AR, Gapin L. 2006. T-bet concomitantly controls migration, survival, and effector functions during the development of Vα14i NKT cells. Blood 107: 2797–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita H, Vesely MD, Koboldt DC, Rickert CG, Uppaluri R, Magrini VJ, Arthur CD, White JM, Chen YS, Shea LK, et al. 2012. Cancer exome analysis reveals a T-cell-dependent mechanism of cancer immunoediting. Nature 482: 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Hermelink N, Braumüller H, Pichler B, Wieder T, Mailhammer R, Schaak K, Ghoreschi K, Yazdi A, Haubner R, Sander CA, et al. 2008. TNFR1 signaling and IFN-γ signaling determine whether T cells induce tumor dormancy or promote multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell 13: 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Narazaki M, Hibi M, Yawata H, Yasukawa K, Hamaguchi M, Taga T, Kishimoto T. 1991. Critical cytoplasmic region of the interleukin 6 signal transducer gp130 is conserved in the cytokine receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci 88: 11349–11353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacy CA, Fortier AH, Meltzer MS, Buchmeier NA, Schreiber RD. 1985. Macrophage activation to kill Leishmania major: Activation of macrophages for intracellular destruction of amastigotes can be induced by both recombinant interferon-γ and non-interferon lymphokines. J Immunol 135: 3505–3511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan NA, Kronenberg M. 2007. Invariant NKT cells amplify the innate immune response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 178: 2706–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka T, Narazaki M, Hirata M, Matsumoto T, Minamoto S, Aono A, Nishimoto N, Kajita T, Taga T, Yoshizaki K, et al. 1997. Structure and function of a new STAT-induced STAT inhibitor. Nature 387: 924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka T, Tsutsui H, Fujimoto M, Kawazoe Y, Kohzaki H, Morita Y, Nakagawa R, Narazaki M, Adachi K, Yoshimoto T, et al. 2001. SOCS-1/SSI-1-deficient NKT cells participate in severe hepatitis through dysregulated cross-talk inhibition of IFN-γ and IL-4 signaling in vivo. Immunity 14: 535–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor SL, Sakaguchi AY, Shows TB, Law ML, Goeddel DV, Gray PW. 1983. Human immune interferon gene is located on chromosome 12. J Exp Med 157: 1020–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor SL, Gray PW, Lalley PA. 1984. Mouse immune interferon (IFN-γ) gene is on chromosome 10. Somat Cell Mol Genet 10: 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Negishi H, Taniguchi T, Yanai H. 2017. The interferon (IFN) class of cytokines and the IFN regulatory factor (IRF) transcription factor family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a028423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Ramana CV, Bayes J, Stark GR. 2001. Roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in interferon-γ-dependent phosphorylation of STAT1 on serine 727 and activation of gene expression. J Biol Chem 276: 33361–33368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Ward JP, Gubin MM, Arthur CD, Lee SH, Hundal J, Selby MJ, Graziano RF, Mardis ER, Korman AJ, et al. 2017. Temporally distinct PD-L1 expression by tumor and host cells contributes to immune escape. Cancer Immunol Res 5: 106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy R, Pollard JW. 2014. Tumor-associated macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 41: 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K. 1995. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-γ production by T cells. Nature 378: 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriss TB, McCarthy SA, Morel BF, Campana MA, Morel PA. 1997. Crossregulation between T helper cell (Th)1 and Th2: Inhibition of Th2 proliferation by IFN-γ involves interference with IL-1. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 158: 3666–3672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan T, Saddawi-Konefka R, Vermi W, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM, Uppaluri R, Andrews DM, Ngiow SF, Teng MWL, et al. 2012. Cancer immunoediting by the innate immune system in the absence of adaptive immunity. J Exp Med 209: 1869–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi T, Lee SW, Ouchi M, Aaronson SA, Horvath CM. 2000. Collaboration of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and BRCA1 in differential regulation of IFN-γ target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97: 5208–5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overacre-Delgoffe AE, Chikina M, Dadey RE, Yano H, Brunazzi EA, Shayan G, Horne W, Moskovitz JM, Kolls JK, Sander C, et al. 2017. Interferon-γ drives Treg fragility to promote anti-tumor immunity. Cell 169: 1130–1141.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamer E, Cresswell P. 1998. Mechanisms of MHC class I–restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol 16: 323–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Zhang M, Wang J, Wang Q, Xia D, Sun W, Zhang L, Yu H, Liu Y, Cao X. 2004. Interferon-γ is an autocrine mediator for dendritic cell maturation. Immunol Lett 94: 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoll DM. 2012. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penix L, Weaver WM, Pang Y, Young HA, Wilson CB. 1993. Two essential regulatory elements in the human interferon γ promoter confer activation specific expression in T cells. J Exp Med 178: 1483–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penix LA, Sweetser MT, Weaver WM, Hoeffler JP, Kerppola TK, Wilson CB. 1996. The proximal regulatory element of the interferon-γ promoter mediates selective expression in T cells. J Biol Chem 271: 31964–31972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernis A, Gupta S, Gollob KJ, Garfein E, Coffman RL, Schindler C, Rothman P. 1995. Lack of interferon γ receptor β chain and the prevention of interferon γ signaling in TH1 cells. Science 269: 245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizenmaier K, Wiegmann K, Scheurich P, Krönke M, Merlin G, Aguet M, Knowles BB, Ucer U. 1988. High affinity human IFN-γ-binding capacity is encoded by a single receptor gene located in proximity to c-ros on human chromosome region 6q16 to 6q22. J Immunol 141: 856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana CV, Gil MP, Schreiber RD, Stark GR. 2002. Stat1-dependent and -independent pathways in IFN-γ-dependent signaling. Trends Immunol 23: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis LF, Harada H, Wolchok JD, Taniguchi T, Vilcek J. 1992. Critical role of a common transcription factor, IRF-1, in the regulation of IFN-β and IFN-inducible genes. EMBO J 11: 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SK, Wachira SJ, Weihua X, Hu J, Kalvakolanu DV. 2000. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β regulates interferon-induced transcription through a novel element. J Biol Chem 275: 12626–12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JK, Hayes MP, Carter JM, Torres BA, Dunn BM, Russell SW, Johnson HM. 1986. Epitope and functional specificity of monoclonal antibodies to mouse interferon-γ: The synthetic peptide approach. J Immunol 136: 3324–3328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakatsume M, Igarashi K, Winestock KD, Garotta G, Larner AC, Finbloom DS. 1995. The Jak kinases differentially associate with the α and β (accessory factor) chains of the interferon γ receptor to form a functional receptor unit capable of activating STAT transcription factors. J Biol Chem 270: 17528–17534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C, Darnell JE. 1995. Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: The JAK-STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 64: 621–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. 2007. Regulation of interferon-γ during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol 96: 41–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber RD, Hicks LJ, Celada A, Buchmeier NA, Gray PW. 1985. Monoclonal antibodies to murine γ-interferon which differentially modulate macrophage activation and antiviral activity. J Immunol 134: 1609–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]