Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increases risk of dementia, a relationship that may be mediated by amyloid-beta (Aβ) and downstream Alzheimer’s Disease pathology. We previously showed OSA may impair Aβ clearance and affect the relationship between slow wave activity (SWA) and Aβ. In this study, SWA and CSF Aβ were measured in participants with OSA before and 1–4 months after treatment. OSA treatment increased SWA, and SWA was significantly correlated with lower Aβ after treatment. Greater improvement in OSA was associated with greater decreases in Aβ. We propose a model whereby OSA treatment may affect both Aβ release and clearance.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a highly-prevalent sleep disorder in which airway blockage during sleep causes hypoxemia, frequent arousals, and other downstream effects. OSA increases risk of dementia and cognitive decline,1–3 suggesting that OSA may promote Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) pathogenesis. The effect of sleep on soluble amyloid-β (Aβ) may mechanistically link sleep disorders with AD. Sleep deprivation increases Aβ levels, primarily through increased release of Aβ by neurons into the interstitial fluid (ISF).4–5 Preliminary studies suggest slow wave activity (SWA) may modulate soluble Aβ: selective SWA deprivation increases Aβ,6 while partial sleep deprivation with preserved SWA does not affect Aβ.7 Cross-sectionally, in the normal population, increased SWA is associated with lower Aβ levels.8–9 While insoluble amyloid plaques in AD exert a “sink” effect causing abnormally low soluble Aβ42 levels,10,11 prior to any plaques, higher soluble Aβ levels increase risk of amyloid plaque formation.12 Herein we focus on Aβ levels during mid-life prior to AD pathology, when theoretically lower Aβ indicates lower risk of developing AD pathology.

We previously found SWA is decreased in moderate-to-severe OSA, yet Aβ is decreased compared to people without OSA, and there is no association between Aβ and SWA.8 Other groups have shown reduced SWA and abnormal dissipation of SWA overnight in mild OSA.13 We found that other CNS-derived proteins were decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), suggesting there was reduced clearance from the ISF to the CSF.8 The glymphatic system facilitates clearance from the ISF to CSF,14 and is affected by pulsations related to respiration,15 and we hypothesized that the pressure fluctuations during apneas and secondary effects on venous drainage impede normal glymphatic clearance in OSA. Subsequently, another group has also found decreased Aβ levels in OSA.16 Decreased clearance of Aβ would to lead to increased ISF Aβ which, over time, hypothetically increases risk of amyloid plaques and subsequent AD pathology.12

In this study, we examined the effect of treatment of OSA on Aβ and SWA.

Methods

Participants from the Saint Louis, Missouri community were included if they were age 35–65 years, had body (BMI) 18–40 kg/m2, had no subjective cognitive decline, reported sleeping “about the same” or “slightly worse” in unfamiliar situations, and reported sleep periods from 8PM-midnight to 4AM-8AM. Exclusion criteria were other sleep disorders, prior OSA treatment, co-morbidities except hypertension, neuro-active medications, alcohol >14 drinks/week, and Mini-Mental Status Exam <27. Participants provided informed, written consent.

OSA:

Participants underwent a polysomnogram using standard criteria.17 Hypopneas were defined as decrease in airflow with ≥4% desaturation. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) determined whether a participant had mild OSA (AHI 5–15) or moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI ≥15). Participants with ≥15 (hour−1) periodic limb movements were excluded.

Participants were provided auto-titrating PAP machines (REMstar Auto, Philips-Respironics) set at 4–20 cmH2O. Following usage for ≥2 weeks, settings were changed to continuous PAP at the 90th percentile delivered pressure. For participants (N=3) with difficulty tolerating continuous PAP, the mode was reverted to auto-titrating, with the range set from the median to the 90th percentile pressures from the initial auto-titrating period. One participant sought clinical care and underwent polysomnogram for PAP titration, and continued in this study using the identified optimal PAP pressure. Participants had up to 4 months to demonstrate adherence to PAP, defined as usage ≥4 hours on ≥70% of 30 preceding nights recorded by PAP machine. Interval between polysomnograms was 1–4 months.

CSF was obtained by lumbar puncture at 9:30–10AM following polysomnograms, and Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau and total protein levels were assessed as previously described.8 Individuals (N=4) with abnormally low Aβ42 levels (<608 pg/mL) indicating amyloid plaques were excluded from analyses of Aβ40 or Aβ42.10

SWA was quantified by electroencephalographic spectral power in the delta (0.5–4 Hz) frequencies, averaged during non-REM sleep.6,8

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 24 (IBM). Continuous variables were compared with Student’s T-tests if normally-distributed, and Mann-Whitney-U tests or Wilcoxon-Signed rank tests if not. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-squared tests. Correlations were assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

Of 35 participants with OSA, 18 were adherent to PAP and completed the study. OSA severity was mild in 7, and moderate-to-severe in 11. Participants were 56.9 ±8.3 years old on average, 67% (12) were male, and 72% (13) were Caucasian. BMI was 30.4 ±4.6 kg/m2, and 28% (5) reported having hypertension. Final PAP settings were 9.2 ±2.0 to 9.7 ± 2.2 cm H2O. Participants used PAP for >4 hours on 88% ±12% of nights during the 30 days preceding the second polysomnogram, for 6:18 ±0:57 hours per night. PAP treatment was effective, as shown by normalized AHI and decreased time in hypoxemia. While total sleep time and sleep efficiency did not change, SWA increased after treatment, there was shift of sleep time from light N1 sleep to deeper N3 sleep, and the frequency of arousals decreased. (Table 1)

Table 1 –

Effect of PAP treatment

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep characteristics | |||

| Total sleep time (minutes) | 377 ±69 | 377 ±82 | 0.988 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 78 ±13 | 78.7 ±15 | 0.956 |

| Latency (minutes)a | 6.5 ±17.5 | 12.5 ±19.3 | 0.306 |

| Rapid eye movement sleep latency (minutes) a | 76.5 ±82.3 | 74.5 ±63.3 | 0.144 |

| Wake time after sleep onset (minutes) | 81 ±46 | 75 ±48 | 0.507 |

| Rapid eye movement sleep (minutes) [% of total sleep time] a | 62 ±40 [16% ±7%] | 79 ±25 [21% ±6%] | 0.170 |

| Non-rapid eye movement sleep (minutes) a | 302 ±107.5 | 312 ±64 | 0.267 |

| N1 (minutes) [% of total sleep time] a | 48 ± 35 [12% ±12%] | 22 ± 16 [6% ±5%] | 0.004 |

| N2 (minutes) [% of total sleep time] | 240 ± 65 [62% ±11%] | 233 ±71 [63% ±12%] | 0.741 |

| N3 (minutes) [% of total sleep time] a | 1 ± 21 [0% ±6%] | 21 ± 60 [5% ±16%] | 0.005 |

| Awakenings | 7 ±4 | 6 ±4 | 0.222 |

| OSA-related variables | |||

| AHIa (hour−1) | 18 ±30 | 1.1 ±4 | <0.001 |

| SaO2 nadira | 82.5% ± 8% | 91% ±6% | 0.001 |

| Time with SaO2 below 90% (minutes) a | 5.1 ±11.3 | 0.1 ±1.4 | 0.007 |

| Arousals (hour−1) | 35 ±23 | 10.9 ±5.0 | <0.001 |

| Spectral power | |||

| Deltaa | 143 ±127 | 152 ±158 | 0.004 |

| Thetaa | 11.6 ±5.5 | 14.5 ±9.3 | 0.004 |

| Alphaa | 6.8 ±3.1 | 7.2 ±5.1 | 0.177 |

| Betaa | 2.9 ±2.5 | 3.5 ±2.7 | 0.407 |

| 18–50 Hza | 2.6 ±1.3 | 6.6 ±1.8 | 0.093 |

| CSF | |||

| Aβ40 (pg/mL) | 12033 ±3972 | 12059 ±3560 | 0.944 |

| Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 987 ±329 | 977 ±319 | 0.733 |

| Tau (pg/mL) | 184 ±96 | 182 ±102 | 0.602 |

| Protein (mg/mL) | 0.857 ±0.279 | 0.912 ±0.235 | 0.197 |

Mean ±standard deviation shown with p value for paired t-test between pre- and post-treatment conditions.

Not normally distributed variables. Median and interquartile range shown, and p value is for Wilcoxon Signed Rank test between pre- and post-treatment conditions.

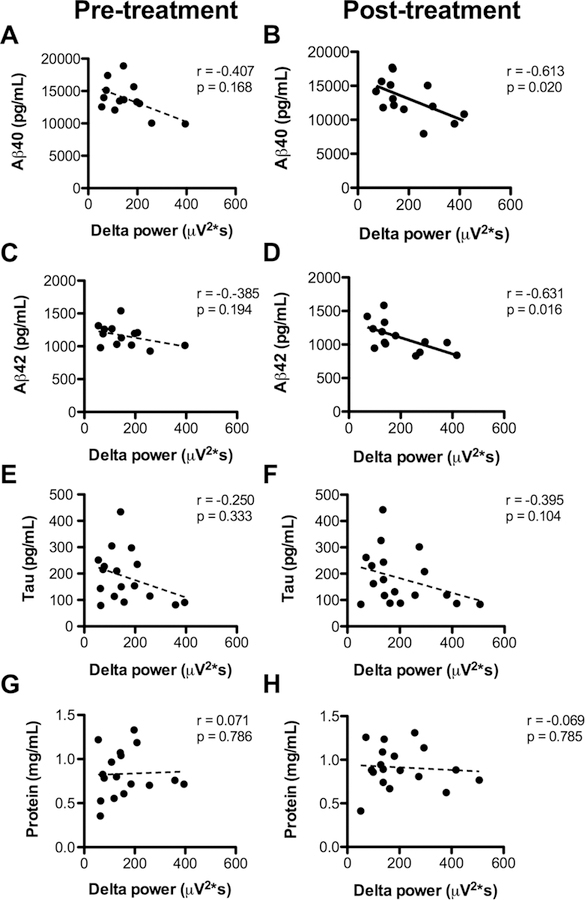

Prior to PAP, there was no statistically significant correlation between SWA and Aβ that is seen in normal individuals (Figure 1A, 1C). After PAP treatment, we found a significant negative correlation between SWA and Aβ, whereby higher SWA is significantly correlated with lower Aβ (Figure 1B, 1D). Tau and total protein were not associated with SWA before or after PAP.

Figure 1 – Association of slow wave activity and amyloid-β.

Before treatment (left column), there is no significant correlation between slow wave activity as measured by delta power, and (A) Aβ40, (C) Aβ42, (E) tau, or (G) total protein in CSF. After treatment (right column), there is a significant negative correlation between SWA and (B) Aβ40 and (D) Aβ42; there is no correlation with (F) Tau or (H) total protein. Linear regression lines are shown for illustrative purposes; since the data were not normally distributed, correlations were assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r=rho) and associated p values.

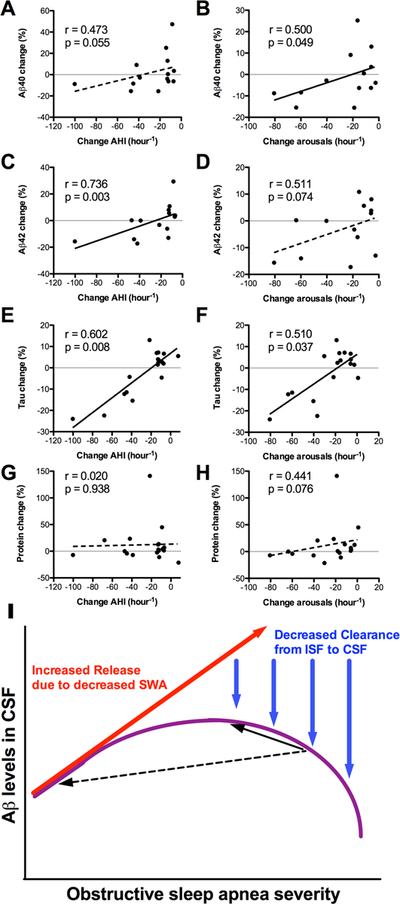

As a group, there was no significant change in Aβ with PAP treatment (Table 1). We performed correlational analyses between the degree of OSA improvement and the degree of change in Aβ and other proteins. We found that greater improvement in OSA was associated with greater decrease in Aβ40 and Aβ42 (Figure 2A-D). Additionally, we found that change in tau negatively correlated with OSA improvement, but no such relationship with total protein (Figure 2E-H). Notably, we observed that participants who had a small improvement in OSA had increases in Aβ40, Aβ42, and tau.

Figure 2 – Change in amyloid-βis associated with change in OSA severity.

Improvement of OSA is shown on the X-axes, with more leftward values indicating greater improvement. The graphs in the left column show change in AHI, while the graphs in the right column show change in arousals per hour. Greater improvement in OSA was associated with decreased (A,B) Aβ40, (C,D) Aβ42, and (E,F) Tau, but not (G,H) total protein. Linear regression lines are shown for illustrative purposes; since the data were not normally distributed, correlations were assessed with Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r=rho) and associated p values. (I) A schematic illustrates two interacting effects of OSA on CSF Aβ levels. With increasing arousals and sleep disruption related to OSA, SWA decreases; this leads to increased Aβ release into the interstitial space (red arrow). However, with worsening OSA severity, there is reduced glymphatic clearance from the ISF to CSF, due to abnormal pressure fluctuations during obstructive respiratory events (blue arrows). The combination of these two effects is hypothesized to result in an inverse U-shape of Aβ in the CSF with increasing OSA severity (purple curve). The black arrows illustrate the direction of change in CSF Aβ following treatment of OSA. If OSA is improved a small degree (solid black arrow), CSF Aβ levels may increase, whereas if OSA is improved a large degree (dashed black arrow), CSF Aβ may decrease.

Discussion

We found that treatment of OSA was associated with increased SWA, and that after PAP treatment, there was a negative association between SWA and Aβ as described in normal individuals. We previously described a lack of association between SWA and Aβ in moderate-severe OSA,8 and here we found the same after including participants with mild OSA. Since our participants had objectively-confirmed high adherence to treatment for 1–4 months, we believe the elevation in SWA is sustained and not due to “first night” treatment rebound effects.18 Greater improvement in OSA was associated with more decrease in Aβ and tau, however participants with minimal improvement in OSA had increased Aβ and Tau. In combination with our prior finding that CNS-derived proteins are decreased in moderate-severe OSA,8 we propose a two-factor model for the relationship between OSA and Aβ (Figure 2I). Due to decreased SWA, there would be relatively increased release of Aβ into the ISF. However, as OSA severity worsens, pressure effects of obstructive respiratory events impede the clearance of Aβ and tau out of the interstitial space, resulting in lower levels in the CSF, and an inverse U-shaped curve. In this model, a small improvement in OSA may result in an increase in Aβ or tau, whereas a larger improvement in OSA—that ameliorates both SWA and clearance mechanisms—will result in a decrease in Aβ and tau. The inverse U-shaped curve is expected in the lumbar CSF, while it is hypothesized that Aβ would be increased in the ISF for all severities of OSA.

Strengths of our study include carefully selected participants, outstanding PAP adherence at effective settings, and intra-individual analyses to maximize power. Our study is the first to examine the effect of OSA treatment on SWA and Aβ levels in individuals without AD. A single case report described the reversal of AD biomarkers with OSA treatment.19 We tested individuals without any AD pathology as assessed by CSF Aβ42, a highly-sensitive biomarker of amyloid plaques.11 This means our study findings can be extrapolated to the large population of people with OSA, many of whom are middle-aged or younger, and have many years to accrue benefit from AD risk reduction.

Due to the study design, untreated participants were excluded, therefore the trajectory of Aβ and tau in untreated OSA is unknown, nor can we determine if our findings are attributable to the “first night” effect during the first polysomnogram. Therefore we are unable to draw causal inference from our findings. Hypoxia may separately affect Aβ release and clearance. However, since changes in arousals, hypoxemia, and AHI were highly correlated, we could not separate any individual effects of changing these variables, particularly due to the small data set.

In summary, we found that PAP treatment for OSA was associated with increased SWA, higher SWA was correlated with lower Aβ, and greater improvement in OSA was associated with greater decreases in Aβ and tau levels. The effect of OSA on SWA and Aβ—and possibly tau—is a probable proximal step in a cascade whereby OSA increases the risk of AD. Furthermore, once amyloid plaques are present, OSA is associated with accelerated increase in plaque burden longitudinally.20 Given the high prevalence of OSA, if the effects on Aβ could be mitigated with treatment, improving OSA diagnosis and treatment could potentially reduce AD risk on a broad scale.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Philips-Respironics (no number) and National Institutes of Health awards K23NS089922, UL1RR024992 Sub-Award KL2TR000450, and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential Conflicts of Interest YSJ received an investigator-initiated grant from Philips-Respironics to support the research reported in this grant. Specifically, this grant solely provided PAP equipment used during the study, which was returned to Philips-Respironics at the conclusion of the study. Philips-Respironics had no input or role on the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. DMH, MAZ, MBF, AMF have nothing to report.

References

- 1.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA 2011;306(6):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang WP, Liu ME, Chang WC, et al. Sleep apnea and the risk of dementia: a population-based 5-year follow-up study in Taiwan. PLoS One 2013;8(10):e78655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osorio RS, Gumb T, Pirraglia E, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology 2015;84(19):1964–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ooms S, Overeem S, Besse K, et al. Effect of 1 night of total sleep deprivation on cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in healthy middle-aged men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2014;71(8):971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucey BP, Hicks TJ, McLeland JS, et al. Effect of sleep on overnight cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β kinetics. Ann Neurol 2018;83(1):197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju YS, Ooms SJ, Sutphen C, et al. Slow wave sleep disruption increases cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β levels. Brain 2017;140(8):2104–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson M, Ärlig J, Hedner J, et al. Sleep deprivation and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep 2018;doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ju YS, Finn MB, Sutphen CL, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea decreases central nervous system-derived proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol 2016;80(1):154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varga AW, Wohlleber ME, Giménez S, et al. Reduced slow-wave sleep is associated with high cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 levels in cognitively normal elderly. Sleep 2016;39(11):2041–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schindler SE, Sutphen CL, Teunissen C, et al. Upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid β 42 assay values for more than 10 years. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(1):62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, et al. Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system. Arch Neurol 2012;69(1): 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju YS, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology--a bidirectional relationship. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10(2):115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ondze B, Espa F, Dauvilliers Y, et al. Sleep architecture, slow wave activity and sleep spindles in mild sleep disordered breathing. Clin Neurophysiol 2003. May;114(5):867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013;342(6156): 373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiviniemi V, Wang X, Korhonen V, et al. Ultra-fast magnetic resonance encephalography of physiological brain activity – Glymphatic pulsation mechanisms? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36(6):1033–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liguori C, Mercuri NB, Izzi F, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with early but possibly modifiable Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers changes. Sleep 2017;doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iber C and American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications Darien IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brillante R, Cossa G, Liu PY, Laks L. Rapid eye movement and slow-wave sleep rebound after one night of continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirology 2012. April;17(3):547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liguori C, Chiaravalloti A, Izzi F, et al. Sleep apnoeas may represent a reversible risk factor for amyloid-β pathology. Brain 2017;140(12):e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma RA, Varga AW, Bubu OM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea severity affects amyloid burden in cognitively normal elderly. A longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197(7):933–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]