Abstract

Pediatric oncology psychosocial professionals collaborated with an interdisciplinary group of experts and stakeholders and developed evidence-based standards for pediatric psychosocial care. Given the breadth of research evidence and traditions of clinical care, 15 standards were derived. Each standard is based on a systematic review of relevant literature and used the AGREE II process to evaluate the quality of the evidence. This article describes the methods used to develop the standards and introduces the 15 articles included in this special issue. Established standards help ensure that all children with cancer and their families receive essential psychosocial care. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:S419–S424.

Keywords: cancer, child, family, pediatric, psychosocial, standards

INTRODUCTION

A large body of research documents the psychosocial risks for children and their families during and after cancer treatment and approaches to reduce distress and support patients and families. [1–3] Yet, there is a significant variability in psychosocial services offered to patients in different pediatric oncology settings. Furthermore, there are no published, comprehensive, evidence-based standards for pediatric psycho-oncology care.[4] To address this critical gap, the Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer (PSCPCC), a group of pediatric oncology psychosocial professionals, collaborated with a larger interdisciplinary group of experts and stakeholders to develop evidence- and consensus-based standards for pediatric psychosocial care. This special issue of Pediatric Blood and Cancer is a comprehensive set of short articles that describe the standards that have been identified as essential for psychosocial care and summarizes the relevant supporting evidence. This introductory article provides the background for the initiative and describes the methodology used to develop the standards.

METHODS

The formation of the PSCPCC and development of psychosocial standards of care for pediatric cancer have been dependent upon the collaboration and support from The Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation (www.mattiemiracle.com). Mattie Miracle was started by Vicki and Peter Brown in memory of their son Mattie who died of multi-focal osteosarcoma at the age of 7 years. The foundation is dedicated to “addressing the psychosocial needs of children and families living with childhood cancer as well as educating healthcare providers on the impact of such a diagnosis on children and their families.” On March 20,2012, Mattie Miracle sponsored a congressional symposium and briefing on Capitol Hill stressing the importance of universal services to address the psychosocial needs of children with cancer and their families. The Browns identified five leaders in psychosocial aspects of pediatric cancer; each presented research data at the briefing related to standards for psychosocial care (Anne E. Kazak, PhD, ABPP [Chair]; Robert B. Noll, PhD, Andrea Farkas Patenaude, PhD, Kenneth Tercyak, PhD, Lori Wiener, PhD). A panel of parents and survivors further emphasized the need for psychosocial care for children with cancer and their families. It became clear in conversations with members of Congress and their staffs that any legal or government support for such universal psychosocial care would require clear, widely accepted, well-supported standards for the psychosocial support of children with cancer and their families. Development of these standards based on existing research and existing consensus became a priority of Mattie Miracle and the group leaders.

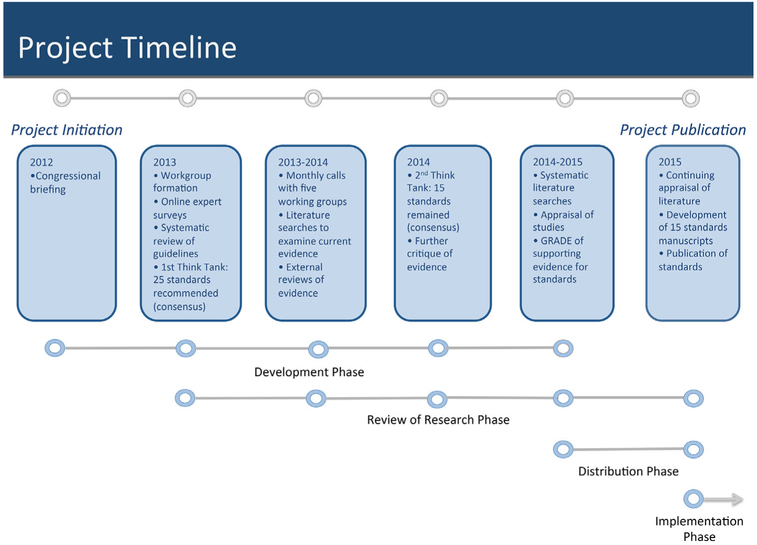

The existing literature on guideline development informed our development of standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer.[5,6] (Fig. 1). The group leaders completed a systematic review of current pediatric psychosocial published guidelines, recommendations, standards, and consensus reports.[3] The review not only highlighted the notable past efforts to define and characterize standards of psychosocial care for children with cancer and their family members, but also showed the lack of a widely accepted, up-to-date, evidence and consensus-based, comprehensive standard.

Fig. 1.

Phases in the development of standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and associated tasks.

To ensure coverage of all critical areas of psychosocial care, we next constructed and administered an online survey to 20 additional psycho-oncology experts across a range of clinical and geographic settings, asking the following questions: (1) What are the five most important issues that we should know about families in order to provide optimal psychosocial care?; (2) What are the most essential services/interventions that should be provided to families throughout the cancer treatment trajectory?; (3) In your setting, what do administrators need to know about psychosocial services that should (and could) be provided to all families and are not currently available or need improvement?; (4) Please list up to five challenges to developing and implementing psychosocial standards/guidelines; and (5) What are some of the most innovative and/or effective ways you or others have discussed or utilized to implement psychosocial care? Three independent psychosocial clinicians reviewed the survey data. Consensus was obtained to define five distinct critical areas wherein standards are needed for satisfactory provision of psychosocial care for children with cancer. These are as follows: (1) Assessment of Child and Family Well-Being and Emotional Functioning; (2) Neurocognitive Status; (3) Psychotherapeutic Interventions; (4) School Functioning; and (5) Communication, Documentation, and Training of Psychosocial Services.

The PSCPCC held two in-person meetings (“think tanks”), each at an annual meeting of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS) with the sponsorship of Mattie Miracle (travel and logistics) and APOS (meeting space). Between these meetings, PSCPCC held monthly teleconferences focused on organizing reviews of literature in these five areas.

The first think tank meeting occurred on February 14, 2013. In attendance were 20 experts in the field of adult and pediatric psycho-oncology from the majority of relevant professional groups (oncology, psychiatry, psychology, social work, and nursing) and four parent stakeholders. The purpose of the meeting was to determine the scope of the standards and to reach agreement about elements of essential, high-quality psychosocial care that can be implemented in all pediatric oncology settings. Using Livestrong’s criteria for an Essential Element of care,[7] it was decided that each proposed standard would be evaluated for its “positive impact on quality of life for all cancer patients and their family members,” and potential for utilization in a wide variety of settings. Further, each element required documented support from an existing behavioral science evidence base. Recognizing that a strong evidence base did not exist for some elements of psychosocial care, alternative sources of data that clearly described services widely utilized and are valued by a consensus of the provider community and which could be evaluated in future research were also viewed as providing an acceptable basis for inclusion of a standard of care.

During the think tank, each of the five groups reviewed qualitative data from our online survey and contributed their clinical knowledge and understanding of the supporting literature to make recommendations for elements considered “essential” for psychosocial care in their domain. This was followed by a consensus session wherein all meeting participants reviewed recommendations from the individual working groups. At the conclusion of the meeting, 25 Essential Elements for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families were identified.

In the year between the two think tank meetings, working groups were charged with investigating and critiquing the related professional literature to determine whether there was sufficient and compelling evidence or consensus to support each of the essential recommendations generated during the think tank. Leaders from the working groups invited additional interdisciplinary experts and stakeholders to join their groups, as needed. During the first 6 months, the working groups held monthly conference calls wherein they reviewed inclusion and exclusion criteria for their individual literature reviews; conducted systematic literature searches; and identified and defined additional clinical issues not previously noted. The working groups also documented and critiqued available evidence. Each group decided whether they had agreement about whether an explicit link existed between each recommendation and the related evidence, including the potential barriers to implementation of the standard. During the next 6 months, tables of evidence were created and the quality of the literature was rated. To avoid the risk of bias, experts in the field reviewed each other’s content and informed a second review and/or revision of the standard. This process continued until no new revisions were recommended.

The Appraisal Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II)[5] were used by each group to rate the evidence for their standard. We specifically addressed the following areas: Identification of Target Population; Essential Element, Rationale, Key Evidence, Literature Search Strategy, Organizational Barriers, Response to Barriers, and Literature Cited. Using a rating form, each working group sent their findings to non-member experts who had agreed to review the interim guidelines to determine whether the evidence supported the recommended standard (Table I). Data from the five working groups were combined into a single document that formed the basis for discussion at the second think tank meeting.

TABLE I.

Items From the AGREE II Rating Forms Used to Rate Evidence for Each Standard

| 1. The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described. |

| 2. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. |

| 3. The potential organizational and logistic barriers that could prevent successful implementation of this element at every pediatric cancer center have been addressed. |

| 4. The recommendation provides advice and/or tools on how it can be put into practice. |

| 5. The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. |

| 6. The literature search strategy is adequate. |

| 7. There is enough evidence to support this Recommendation as a Standard of Care at every center where a child with cancer is treated. |

| 8. Rate the overall quality of this recommendation. |

Throughout the year, there was a conscious effort to include representation from multiple relevant disciplines within the working groups. Consequently, the working groups consisted of 22 psychologists, three psychiatrists, five social workers, one advanced practice nurse, and two oncologists from the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands and five parent advocates. The working groups also represented members from numerous professional groups: American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), International Psychosocial Oncology Society (IPOS), International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP), Children’s Oncology Group (COG), Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers (APOSW), Society of Pediatric Psychology (SPP, Division 54 of the American Psychological Association [APA]), Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses (APHON), American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), Association for Psychological Science (APS), and the Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Education Specialists (APHOES).

The second PSCPCC think tank was held on February 13, 2014, in Tampa, Florida. In attendance were 15 of the participants from the initial meeting and four additional experts with specific clinical and research expertise in areas not previously represented. Each of the 25 recommendations was further evaluated in connection to the related evidence. During this meeting, each standard was reviewed and rated by a different working group than the one that had created the standard. Working groups each included a pediatric oncologist, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, and a parent or survivor stakeholder. Working group members reviewed each individual standard, the corresponding evidence table, external reviews, and barriers to implementation. Standards without sufficient evidence were eliminated and those with apparent overlap were combined. A shortened list of 15 standards was developed via a consensus process with the full group during the meeting. The wording of each standard was further refined via conference calls.

For each of these final 15 standards, individual members were charged with re-reviewing the literature to assure all relevant and/or new evidence was included. PRISMA guidelines were used to conduct the systematic reviews.[8] For consistency, all authors were instructed to include studies published from March 1995 to March 2015. Search terms and inclusion criteria were specified in advance. Group members used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme[9] checklists to assess individual study rigor, through examination of study design, analysis, and results. In standards for which there was limited evidence, expert opinion or consensus reports were included and described.

As guidelines can be inconsistent in how they rate the quality of evidence and grade the strength of their recommendations,[10] several journals now require authors submitting clinical guidelines to use a formal system known as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). In summarizing the evidence for each standard, the authors were required to independently appraise their body of evidence as a whole using the GRADE system.[10] Specifically, the GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence in one of four levels—high, moderate, low, and very low. Evidence based on randomized controlled trials begins as high-quality evidence, but confidence in the evidence may be decreased for reasons, including inconsistency of results and reporting bias. Ratings reflect specific methodological considerations. For example, a case-control study may be rated as having a higher level of evidence if the treatment effect is large. The GRADE system also classifies recommendations as strong or weak. The strength of the recommendation reflects confidence that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh the undesirable effects. For example, desirable effects of an intervention include improvement in the quality of life, reduction in the burden of treatment, reduced resource expenditures, whereas undesirable consequences include adverse effects that have a deleterious impact on quality of life, morbidity, mortality, or increase use of resources. [11] The individual papers in this special issue summarize the evidence base for the full set of consensus standards.

RESULTS

The 15 standards for psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families (Table II) represent the results of what is, to our knowledge, the largest, comprehensive review of this large psychosocial literature. The systematic reviews conducted across the standards involved 66 authors and a total of 1,217 studies. The evidence included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and consensus reports and recommendations from relevant professional organizations provided additional evidence.

TABLE II.

Pediatric Psychosocial Standards With Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations

| Standard | Studies Reviewed |

GRADE* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Quality of Evidence |

Recommendations | |||

| 1. | Youth with cancer and their family members should routinely receive systematic assessments of their psychosocial health care needs. | 149 | High | Strong |

| 2. | Patients with brain tumors and others at high risk for neuropsychological deficits as a result of cancer treatment should be monitored for neuropsychological deficits during and after treatment. | 129 | High | Strong |

| 3. | Long-term survivors of child and adolescent cancers should receive yearly psychosocial screening for: a) adverse educational and/or vocational progress, social and relationship difficulties; b) distress, anxiety, and depression and post traumatic stress disorder(PTSD); c) risky health behaviors. d) pain and fatigue. | 101 | Moderate to High | Strong |

| Adolescent and young adult survivors should receive yearly screening for factors related to survivorship self-management and readiness to transition to adult care, such as self-efficacy, knowledge of health risk and late effects, and motivation for continued engagement. | Low to moderate | Strong | ||

| Adolescent and young adult survivors and their parents should receive anticipatory guidance on the need for life-long follow-up care by the time treatment ends.** | ||||

| 4. | Youth with cancer and their family members should have access to psychosocial support and interventions throughout the cancer trajectory and access to psychiatry as needed. | 173 | High | Strong |

| 5. | Pediatric oncology families are at high risk for financial burden during cancer treatment with associated negative implications for quality of life and parental emotional health. | 24 | Moderate | Strong |

| Assessment of risk for financial hardship should be incorporated at time of diagnosis for all pediatric oncology families. Domains of assessment should include risk factors for financial hardship during therapy including: pre-existing low-income or financial hardship, single parent status, distance from treating center, anticipated long/intense treatment protocol, and parental employment status. | ||||

| Targeted referral for financial counseling and supportive resources (including both governmental and charitable supports) should be offered based on results of family assessment. | ||||

| Longitudinal reassessment and intervention should occur throughout the cancer treatment trajectory and into survivorship or bereavement. | ||||

| 6. | Parents and caregivers of children with cancer should have early and ongoing assessment of their mental health needs. Access to appropriate interventions for parents and caregivers should be facilitated to optimize parent, child and family well-being. | 159 | Moderate | Strong |

| 7. | Youth with cancer and their family members should be provided with psychoeducation, information, and anticipatory guidance related to disease, treatment, acute and long-term effects, hospitalization, procedures, and psychosocial adaptation. | 23 | Moderate | Strong |

| Guidance should be tailored to the specific needs and preferences of individual patients and families and be provided throughout the trajectory of cancer care. | ||||

| 8. | Youth with cancer should receive developmentally appropriate preparatory information about invasive medical procedures. All youth should receive psychological intervention for invasive medical procedures. | 65 | Low

(education) High (interventions) |

Strong Strong |

| 9. | Children and adolescents with cancer should be provided opportunities for social interaction during cancer therapy and into survivorship following careful consideration of the patients’ unique characteristics, including developmental level, preferences for social interaction, and health status. | 59 | Moderate | Strong |

| The patient, parent(s) and a psychosocial team member (e.g., designee from child life, psychology, social work, or nursing) should participate in this evaluation at time of diagnosis, throughout treatment and when the patient enters survivorship; it may be helpful to include school personnel or additional providers. | ||||

| 10. | Siblings of children with cancer are a psychosocially at-risk group and should be provided with appropriate supportive services. Parents and professionals should be advised about ways to anticipate and meet siblings’ needs, even when they are at a distance. | 117 | Moderate | Strong |

| 11. | In collaboration with parents, school-age youth diagnosed with cancer should receive school reentry support that focuses on providing information to school personnel about the patient’s diagnosis, treatment, and implications for the school environment and provides recommendations to support the child’s school experience. | 17 | Low | Strong |

| Pediatric oncology programs should identify a team member with the requisite knowledge and skills who will coordinate communication between the patient/family, school, and the health care team. | ||||

| 12. | Adherence should be assessed routinely and monitored throughout treatment. | 14 | Moderate | Strong |

| 13. | Youth with cancer and their families should be introduced to palliative care concepts to reduce suffering throughout the disease process regardless of disease status. When necessary youth and families should receive developmentally appropriate end of life care [which includes bereavement care after the child’s death]. | 73 | Moderate | Strong |

| 14. | A member of the health care team should contact the family after a child’s death to assess family needs, to identify those for negative psychosocial sequelae, to continue care, and to provide resources for bereavement support. | 95 | Moderate | Strong |

| 15. | Open, respectful communication and collaboration among medical and psychosocial providers, patients and families is essential to effective patient- and family-centered care. Psychosocial professionals should be integrated into pediatric oncology care settings as integral team members and be participants in-patient care rounds/meetings. | 35 | Moderate | Strong |

| Pediatric psychosocial providers should have access to medical records and relevant reports should be shared among care team professionals, with psychological report interpretation provided by psychosocial providers to staff and patients/families for patient care planning. Psychosocial providers should follow documentation policies of the health system where they practice in accordance with ethical requirements of their profession and state/federal laws. | Low | Strong | ||

| Pediatric psychosocial providers must have specialized training and education and be credentialed in their discipline to provide developmentally-appropriate assessment and treatment for children with cancer and their families. Experience working with children with serious, chronic illness is crucial as well as ongoing relevant supervision/peer support. | Low | low | ||

Table II also summarizes the systematic assessment of the quality of the evidence and strength of each of the recommendations. The strongest evidence (e.g., high quality) was found for four standards: Psychosocial assessment during cancer treatment[12] and in survivorship;[13] neurocognitive monitoring for children at risk;[14] psychosocial support;[15] and interventions for painful procedures.[16] Although based on a less rigorous literature, moderate evidence was found for assessment of financial issues; [17] addressing behavioral health issues of parents;[18] psycho-education;[19] social interaction;[20] supportive services for siblings;[21] assessment and monitoring of adherence;[22] early integration of palliative care;[23] and bereavement.[24] Mixed moderate and high quality of evidence was found for survivorship. [13] and moderate-to-low quality of evidence was found for communication, documentation, and training.[25] Low-quality evidence was found for school re-entry[26] and information about invasive medical procedures.[16]

As noted earlier, the GRADE system also classifies recommendations as strong or weak, with the strength of the recommendation reflecting confidence that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh the undesirable effects.[10,11] Even in the absence of strong research evidence, recommendations can be strong if there are multiple expert groups coming to highly consensual conclusions. Although there is variability in the quality of evidence across standards, based on the risk-benefit ratios, practice-based evidence, and consensus, strong recommendations were made for the implementation of each of the 15 standards.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this process was to provide evidence- and consensus-based standards for services considered essential for all children diagnosed with cancer and their families regardless of treatment setting. Through this rigorous process, standards of care for children with cancer and their families were developed. The standards provide a starting point for cancer centers to identify essential elements of comprehensive psychosocial care.

Although it is recommended that these standards be followed at all sites where children with cancer are treated, full implementation will occur at variable rates in different centers, with some already easily concurring and others needing changes to come up to this minimally acceptable level. Pediatric cancer programs can utilize these standards to identify their program strengths and areas where improvements and/or resources are most needed. Having the evidence underpinning each standard available in the Supplementary Evidence Tables will provide support and compelling evidence for implementation of the standards. The articles that follow discuss potential challenges with implementation and provide suggestions for reducing organizational barriers. Each article also clearly addresses areas where additional evidence-based data are needed to strengthen recommendations for a specific psychosocial intervention(s) for children with cancer and their family members.

There are limitations worth noting. First, addressing the needs of young adults with cancer was beyond the scope of this project and special issue. We recommend that similar methods be used to develop psychosocial standards of care for young adults living with cancer.

Second, implementation is likely to occur first in developed countries with established pediatric oncology programs. In lowresourced nations, psychosocial services may differ and develop in concert with the development of high-level medical care for children with cancer in these countries.

Third, the standards do not elucidate optimal care for children with cancer, only essential psychosocial care. There are valued, evidence-based treatments or interventions of known value, which go beyond a minimum standard of universal care. In some centers, it is reasonable to expect provision of services that exceed the essential standards. Fourth, the think tanks did not include child life specialists, educators, or hospital administrators, although we did engage these professionals in the working groups and as reviewers.

Next steps in this project involve the development of recommendations to improve guideline implementation and utilization. With support from Mattie Miracle and APOS, the PSCPCC group leaders have devised a strategic plan to meet yearly at the APOS annual meetings to evaluate implementation of these standards and encourage broader dissemination. New research will also be reviewed annually and the guidelines updated as needed.

CONCLUSION

A lack of standardized psychosocial standards in childhood cancer results in inconsistent access to behavioral healthcare for pediatric cancer patients and their families. The evidence-based standards presented in this special issue include strong recommendations for basic elements of psychosocial care for all children with cancer. These include both well-researched interventions proven effective in clinical trials and other consensus-based widely used interventions with less research support. These broadly implementable standards are sufficiently general to be tailored to the resources of individual sites that treat childhood cancer and to the needs of individual children and families. With evidence that such care contributes to positive quality of life outcomes of children with cancer and their family members, it is hoped that universal access to psychosocial support and intervention for patients and family members can be guaranteed for all 21st century families who face childhood cancer and its sequelae.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the PSCPCC group for their tireless energy and commitment to this project. This work was supported, in part, by the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation and the generous sponsorship of Vicki and Peter Brown. We would also like to thank Dr. Paul Jacobsen for his guidance on the development of standards of care within clinical oncology, Dr. Katherine Kelly for her guidance to the leadership group on AGREE II and GRADE, and Dr. Meaghann Weaver for her design of Figure 1. We are especially indebted to the reviewers of earlier and later drafts of the standards, who are acknowledged in Supplemental Table SI. This work was also funded (in part) by the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute and the Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress.

Grant sponsor: Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute; Grant sponsor: Center for Pediatric Traumatic Stress; Grant number: 5U79SM061255-03

Abbreviations:

- AGREE

The Appraisal Guidelines for Research and Evaluation

- APOS

American Psychosocial Oncology Society

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PSCPCC

Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Mary Jo Kupst has served as a consultant to the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation for the Standards Project. Mattie Miracle has also provided some travel and conference support for the think tanks.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mavrides N, Pao M. Updates in paediatric psycho-oncology. Int Rev Psychiatry 2014;26:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AskinsMA Moore BD 3rd. Psychosocial support of the pediatric cancer patient: Lessons learned over the past 50 years. Curr Oncol Rep 2008;10:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiener LS, Pao M, Kazak AE, Kupst MJ, Patenaude AF, Arceci R. Pediatric psycho-oncology A quick reference on the psychosocial dimensions of cancer symptom management. New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiener L, Viola A, Koretski J, Perper ED, Patenaude AF. Pediatric psycho-oncology care standards, guidelines, and consensus reports. Psychooncology 2015;24:204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Cluzeau F, feder G, Fervers B, Hanna S, Makarski J, on behalf of the AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:E839–E842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner T, Misso M, Harris C, Green S. Development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPG’s): Comparing approaches. Implement Sci 2008;3:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The LIVESTRONG essential elements of survivorship care: Definitions and recommendations, http://images.livestrong.org/downloads/flatfiles/what-we-do/our-approach/reports/ee/Essential-Elements-Definitions_Recommendations.pdf?_ga=1.124932938.1313442476.1415304722. Published 2011. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff I, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) 2014. CASP Checklists. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!checklists/cb36.Oxford.CASP.

- 10.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, Schünemann HJ. GRADE: Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:1049–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336: 924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazak AE, Abrams AN, Banks J, Christofferson J, DiDonato S, Grootenhuis MA, Kabour M, Madan-Swain A, Patel SK, Zadeh S, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):426–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lown EA, Phillips F, Schwartz LA, Rosenberg AR, Jones B. Psychosocial follow-up in survivorship as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):514–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Annett R, Patel SK Phipps S. Monitoring and assessment of neuropsychological outcomes as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):460–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steele AC, Mullins LL, Mullins AJ, Muriel AC. Psychosocial interventions and therapeutic support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):585–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flowers SR, Birnie KA. Procedural preparation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):694–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearney JA, Salley CG, Muriel AC. Psychosocial support for parents of children with cancer as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):632–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson AL, Young-Saleme T. Anticipatory guidance and psychoeducation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):805–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christiansen HL, Bingen K, Hoag JA, Karst JS, Velázquez-Martin B, Barakat LP. Providing children and adolescents opportunities for social interaction as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):724–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerhardt CA, Lehmann V, Long KA, Alderfer MA. Supporting siblings as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):750–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pai ALH, McGrady ME. Assessing treatment adherence as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):818–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver MS, Heinze KE, Kelly KP, Wiener L, Casey RL, Bell CJ, Wolfe J, Garee AM, Watson A, Hinds PS. Palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5): 829–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney C, Roberts K, Corner G, Donovan L, Prigerson HG, Wiener L. Bereavement follow-up after the death of a child as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):834–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patenaude AF, Pelletier W, Bingen K. Staff training, communication and documentation standards for psycho-oncology professionals providing care to children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62(Suppl 5):870–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson AL, Kelly KP, Christiansen HL, Elam M, Hoag J, Irwin MK, Pao M, Voll M, Noll RB. Academic continuity and school reentry support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62(Suppl 5):805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.