Abstract

Organ-on-a-chip platforms serve as cost-efficient testbeds for screening pharmaceutical agents, mimicking natural physiology, and studying disease. In the field of diabetes, the development of an islet-on-a-chip platform would have broad implications in understanding disease pathology and discovering potential therapies. Islet microphysiological systems are limited, however, by their poor cell survival and function in culture. A key factor that has been implicated in this decline is the disruption of islet-matrix interactions following isolation. Herein, we sought to recapitulate the in vivo peri-islet niche using decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogels. Sourcing from porcine bladder, lung, and pancreas tissues, 3-D ECM hydrogels were generated, characterized, and validated using both rodent and human pancreatic islets. Optimized decellularization protocols resulted in hydrogels with distinctive viscoelastic properties that correlated to their matrix composition. The in situ 3-D encapsulation of human or rat islets within ECM hydrogels resulted in improved functional stability over standard culture conditions. Islet composition and morphology were also altered, with enhanced retention of islet-resident endothelial cells and the formation of cord-like structures or sprouts emerging from the islet spheroid. These supportive 3-D physiomimetic ECM hydrogels can be leveraged within microfluidic platforms for the long-term culture of islets.

Keywords: decellularized tissues, 3-D hydrogels, islet niche

1. Introduction

Engineering human microphysiological systems (MPS) capable of intimately characterizing the influence of various parameters on organ function and viability, as well as its impact on “downstream” organs, would not only advance scientific knowledge, but also minimize animal research and improve the safety and efficacy of potential new drugs. Multiple MPS platforms mimicking the heart, lung, liver, and vasculature have been developed [1–4]. Unique islet-on-a-chip systems have been designed to permit ease in short-term islet assessments and characterization [5–9] (for recent review see [10]). Leveraging MPS for the long-term culture of primary pancreatic islets, however, has been limited by their poor stability ex vivo.

In the pancreas, islets of Langerhans are surrounded by a layer of extracellular matrix (ECM) defined as the peri-insular basement membrane (BM), comprised predominately of collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin [11, 12]. Interactions between the multicellular islet and its peripheral ECM serve a critical role in the maintenance of cell viability, the preservation of β cell insulin production and glucose responsiveness, and the coordination of intercellular signaling [13, 14]. During the enzymatic isolation procedure, islets are stripped of this native BM. The subsequent reduction of cell adhesion signaling triggers β cell apoptosis via anoikis, as well as declines in insulin secretion [11, 15, 16]. The islet isolation procedure also disrupts other islet-resident nonhormonal cells, such as endothelial and mesenchymal cells, which serve to support endocrine cell function [17–19].

Previous in vitro studies have shown that the replenishment of individual ECM components found in the pancreatic basement membrane, such as collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin, improves islet viability and restores glucose responsive insulin secretion [20–22]. Moreover, 3-D co-culture of islets within hydrogels co-mixed with ECM components (e.g. collagen type IV and laminin) aids in the preservation of islet viability [11, 23, 24]. While these approaches are promising, supplementation with selected ECM proteins will not fully recapitulate the multiple islet adhesion motifs of the native peri-islet niche.

The use of decellularized tissues enables a diverse spectrum of biochemical and biophysical cues, adapted from nature, to be presented to the encapsulated cells. The composition of the ECM can be tailored via selection of the tissue source and the decellularization approach [25–27]. While whole organ decellularization provides retention of both ECM composition and the organ’s 3-D architecture, loading islet or even β cells into a cell-free organ is complex, requiring multi-step infusions, and incomplete, with only partial cell repopulation into the non-conduit tissue spaces [28, 29]. Alternatively, a decellularized ECM hydrogel permits in situ gelation to uniformly encapsulate cell grafts in physiological 3-D microenvironment. ECM hydrogels can be prepared via a lyophilizing, milling, and enzymatic digestion process [30]. This approach provides an easily adaptable system that is amendable to in vivo injection, 3-D printing, and loading within porous biomaterial platforms (e.g. polypropylene mesh) [30–33].

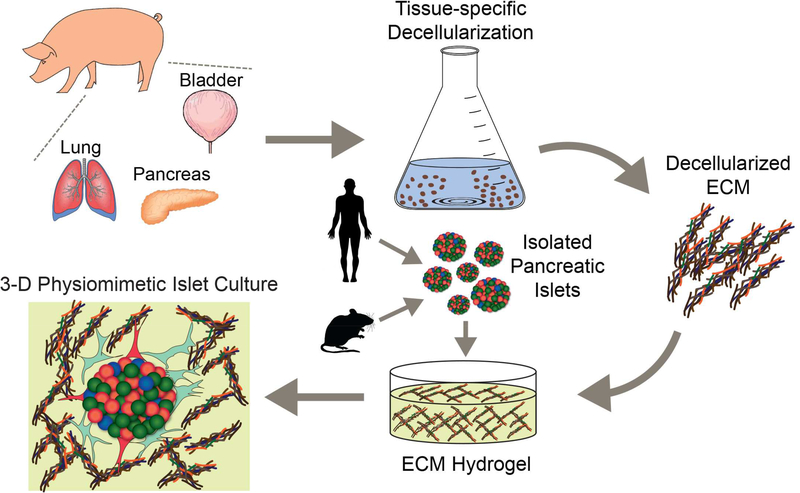

In this study, we sought to explore the potential of decellularized porcine ECM hydrogels for supporting islet culture (Figure 1). Tissues selected for study were pancreas, BM-rich lung and bladder. Tissue-specific decellularization protocols were optimized and resulting materials were characterized for acellularity, protein composition, endotoxin content, and mechanical properties. Resulting hydrogels were subsequently used to encapsulate rat and human pancreatic islets. Islet viability, functionality, cytokine/hormone production, and morphology were evaluated.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of tissue processing and islet encapsulation within 3-D ECM hydrogels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Porcine Tissue Decellularization and ECM Solubilization

Porcine pancreas, lung, and bladder were harvested from the UF Department of Animal Studies under IACUC protocols approved by the University of Florida. The decellularization protocol was modified from published methods to maximize host cell removal and retention of ECM proteins [34–36]. Specifically, freshly procured tissues were rinsed under water, trimmed of peripheral connective tissue, and sectioned into small pieces (5 mm × 5 mm) to increase surface area for processing. Next, tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. After subsequent thawing to room temperature, tissues were incubated in alternating hypertonic (1.1% NaCl) and hypotonic (0.7% NaCl) for 1 h each for 2 cycles. Following a PBS wash, the lung and bladder tissues were transferred to a solution of 8 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 25 mM HEPES buffer in PBS, and incubated for 10 d with solution exchange every other day at room temperature, while the pancreas tissue was treated with 70% isopropanol for 24 h. At this stage, all tissues were visually clear. Tissues were further processed in 0.1% ammonium hydroxide and 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS for another 10 d at 4ºC, with solution exchange every 48 h. During washing, any aggregated tissue was separated using sterile scissors and forceps. After detergent cleaning, the tissue was treated with 70 U/mL Benzonase (Santa Cruz; 50 kU) in PBS for 24 h to degrade nucleic acids. The tissue was then washed with 20% FBS for 3 d with daily solution exchange to remove remnant enzyme. The tissue was rinsed in PBS with solution exchange every other day until no visible foam was observed (at least 3 rinses). All tissues were then disinfected with 70% isopropanol (Decon) for 1 h and rinsed with sterile DI water for 2 d, with daily exchange using aseptic techniques. After processing, tissues were frozen and lyophilized. Of note, all washing solutions were supplemented with antibiotics (200 U/mL Penicillin, 0.2 mg/mL Streptomycin and 2μg/mL amphotericin B; Corning) prior to the final isopropanol disinfection. All incubation steps were carried out under agitation (200 rpm) on an orbital shaker (Thermo Fisher).

For ECM solubilization, decellularized tissues were ground via cyromill (Retsch). Briefly, lyophilized tissues were cut into fine pieces, pre-cooled, and ground (25 Hz) for 5 min for 3 cycles under perfused liquid nitrogen. The ground tissues were defrosted through lyophilization. The resulting powder (100 mg) was then solubilized in 10 mL of a 0.22 μm filtered 0.01 M hydrochloric acid solution (Sigma Aldrich) with 10 mg/mL pepsin (Sigma Aldrich) for 2 d with agitation, as previously described [30]. The solubilized ECM pre-gel solution was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

2.2. Characterization of Porcine Decellularized Tissues

To examine cellular clearance, the decellularized tissue was cryo-embedded in OCT freezing medium and sectioned at 10 μm thickness. The sectioned tissue was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and imaged under a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope with Zeiss Icc5 camera. To measure the degree of decellularization, DNA was extracted (DNeasy kit; Qiagen) and quantified (Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit; Thermo Scientific). To characterize protein composition, decellularized tissue samples were analyzed using Dionex Ultimate 3000 Nano LC system coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive mass spectrometer (NanoLC-MS; Creative Proteomics; Thermo Scientific). For MS data analysis, at least 3 replicates from each decellularized tissue source were analyzed and searched against a porcine protein database using Proteome Discoverer 2.0 (Thermo Scientific). Peptides identified with high confidence were chosen for downstream protein identification analysis. The abundance of these detected proteins, relative to the total protein content, was evaluated based on the mean ion signal peak area of three most intense peptide ion signals (Top3 PQI) [37, 38].

To fabricate ECM hydrogels, the pH of the pepsin digested pre-gel solution was adjusted to 7.4 using 0.01 N NaOH on ice with PBS or CMRL 1066 media. The neutralized pre-gel solution was then placed in an incubator for gel matrix assembly at 37°C for 30 min. Of note, stock ECM hydrogels were prepared at 10 mg/mL while working ECM hydrogels were diluted to 1 mg/mL for in vitro islet studies.

Endotoxin levels within ECM hydrogels were measured via Chromo-LAL endotoxin quantification kit (Cape Cod). Briefly, 100 μL of 1 mg/mL ECM hydrogels (lung, bladder and pancreas) and 100 μL standards (0.005 – 50 EU/mL) were prepared in a clear 96-well microplate. Following pre-incubation at 37°C for 10 min, 100 μL of reconstituted Chromo-LAL reagent was added to each well as rapidly as possible. Kinetic readings were recorded at 405 nm every 30 s for 100 min using M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) and analyzed by SoftMax software (Molecular Devices). The onset time of a sample to reach a defined absorbance was calculated. The resulting standard curve and log-log plot of the onset times versus the standard concentrations were used to determine the endotoxin concentration of each sample.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on the ECM hydrogels for structure analyses. All the gels were fixed in Trump’s Fixative (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and processed with the aid of the Pelco BioWave laboratory microwave (Ted Pella). Samples were then washed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer solution (pH 7.24), fixed with 2% buffered osmium tetroxide, washed in water, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and critical point dried (Bal-Tec CPD030, Leica Microsystems). Dried samples were sputter coated with Au/Pd (Desk V, Denton Vacuum) and imaged on a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SU5000, Hitachi High Technologies America).

For viscoelastic characterization of ECM hydrogels, a customized cantilever-based indentation system (Simmons Laboratory, UF) was used to measure the strain rate-independent modulus [39]. Briefly, a 4 mm-diameter rigid hemispherical tip on a soft titanium cantilever indented 70 μL hydrogels (10 or 1 mg/mL) in 96-well plates. The submerged samples (~2 mm thick) were indented to ≤ 10% of sample thickness at 10 μm/s. Three replicate hydrogels of lung, bladder, and pancreas ECM were indented n ≥ 3 for a total of 9–10 indentation values per tissue type. The transient modulus, converted from force-displacement data, is presented as a function of time using Hertz contact model, shown as follows:

where Etransient = time-dependent effective modulus, F = force as calculated by tip displacement multiplied by calibrated stiffness, ϑ = Poisson’s ratio (estimated ϑ = 0.45), R = radius of spherical indenter tip, and δ = indentation depth calculated as stage movement minus deflection of tip. Following initial indentation, the indentation depth was held constant for 20 s to allow relaxation, and the transient elastic modulus E(t) was calculated at each time point during the stress relaxation. Standard Linear Solid (SLS), a common viscoelastic model, was used to fit the transient modulus as follows [40]:

where Etransient time-dependent effective modulus, ESS = steady-state modulus following complete relaxation, = strain-rate dependent modulus, and τ =η⁄Ea = characteristic time decay constant with η = viscosity.

2.3. In Vitro Encapsulation of Islets with ECM Hydrogels

All animal procedures were performed under protocols approved by the University of Florida IACUC and in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Donor pancreatic islets were isolated in 3 separate isolations from heathy male Lewis rats (Harlan Lab, USA), as described previously [41]. Human pancreatic islets (3 separate donors) were obtained through the NIH Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP). Islets were cultured at 37ºC in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in humidified air in CMRL media. Islet isolations underwent quality control assessments 24 h post-isolation or post-shipment, with additional human isolation assessment performed by IIDP. Rat islet isolations used for these studies had a purity of 95–99% and high viability (per live/dead imaging). Human islets were received within 2–3 d post-isolation at a purity of 80–95% and a reported viability of 90–97%.

To prepare porcine decellularized ECM hydrogel, the pepsinized decellularized porcine bladder and pancreas were thawed and adjusted to pH 7.4. The ECM solution was kept on ice after pepsin inactivation. Cold CMRL media was used to dilute the ECM solution to the desired working concentration of 1 mg/mL. For rat islet culture studies, 150 IEQ rat islets were gently mixed with 200 μL decellularized ECM pre-gel solution at final 1.0 mg/mL concentration 24 h post-isolation, and then loaded into individual wells of 24 well non-tissue treated plate. For human islet culture studies, 100 IEQ human islets were gently mixed with 200 μL decellularized ECM pre-gel solution at a final concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, 24 h after arriving to the laboratory, and then loaded into individual wells of 24 well non-tissue treated plate and incubated at 37°C. After the formation of the hydrogel, additional CMRL media (100 μL) was added to each well. The 100 μL media was renewed every other day.

2.4. Islet Morphological Evaluation within ECM Hydrogels

Following selected duration of co-culture, islet morphology was examined via a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope with Zeiss Icc5 camera. The general localization of viable or dead islets was performed using LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity kit (Thermo Fisher). LIVE/DEAD and immunofluorescent images were acquired using Zeiss LSM 710 and Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. The apoptotic islets were stained with CellEvent Cas-3/7 Green ReadyProbes reagent (Life Technologies) and Hoechst reagent (Thermo Scientific) for 30 min and then imaged under a confocal microscope.

For immunofluorescent characterization of islet morphology and angioarchitecture, islets within ECM gels were cultured on sterile coverslips on the bottom of a 6-well plate. At selected endpoints, free isles or islet within hydrogels were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100/1x PBS for 20 min, and blocked via 10% normal goat serum (Thermo Fisher) for 1 h. Fixed rat islet samples were incubated with primary antibodies including mouse anti-rat CD31(1:100; Novus Biologicals) and rabbit anti-rat insulin (1:400; Abcam) overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200; Thermo Fisher) and DAPI (1:1000) for 90 min at room temperature. Alexa Fluor 680 phalloidin (1:50; Thermo Fisher) was used to stain F-actin for 1 h at room temperature. For the characterization of human islet sprouting cells, samples were incubated with mouse anti-human CD31 antibody [JC/70A] (1:100; Thermo Fisher), rabbit anti-human CD90 antibody [EPR31330 (1:100; Abcam), rat anti-human CD44 antibody (1:100; Thermo Fisher), rabbit anti-human CD105 (1:100; Thermo Fisher), and rabbit anti-human insulin (1:400; Abcam) overnight following fixation and permeabilization as described above. For labeling islets with CD31 and CD44, goat antimouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200; Thermo Fisher) and goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647 (1:200; Thermo Fisher) were used, respectively. To label CD90, CD105, and insulin, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200; Thermo Fisher) was used. Alexa Fluor 680 phalloidin (1:50; Thermo Fisher) and DAPI (1:1000) were then added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 90 min. The immunofluorescent imaging was performed using confocal microscopes.

2.5. Evaluation of the Effect of ECM Hydrogels on Islet Function

The glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) of cultured rat and human islets was evaluated using a dynamic perifusion system (Biorep Technologies) at designed endpoints. Briefly, free islets or hydrogel-encapsulated islets were loaded into perifusion chambers, and the flow rate was set at 100 μL/min. A KRBB buffer (115 mM NaCl2, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 0.2% BSA and 25 mM HEPES) was used to stimulate islets during perifusion tests. The low and high glucose solutions were prepared with 3 mM and 11 mM D-glucose, respectively. To measure total intracellular insulin production, islets were depolarized using a high KCl solution (25 mM KCl in low glucose KRBB buffer). For dynamic GSIR, islets were perifused in the consecutive steps as follows: 60 min pre-elution at low glucose, 10 min at low glucose, 20 min at high glucose, 20 min at low glucose, 5 min at KCl solution and 15 min at low glucose. Elution samples were collected every minute and stored at −80°C for later analysis. Insulin production was quantified via the rat or human insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia), as described previously [42].

During islet culture in vitro, cell supernatants were collected on selected days. The cytokine and metabolic hormones from islet supernatants were analyzed using the multiplexed Luminex MAGPIX system. IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, VEGF, IFN-γ, MIP-1α, MCP-1 and TNF-α were included in rat and human Milliplex cytokine/chemokine panels. Insulin, c-peptide, glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), amylin, and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) were included rat and human Milliplex metabolic hormone panels. The endotoxin levels of the islet culture supernatants were quantified using LAL chromogenic endotoxin quantitation kit (Thermo Fisher).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between groups were made using the same islet preparation (human or rat) with n > 3 independent assessments conducted for each assay from each isolation. In addition, rat islet culture experiments were repeated using n =3 distinct rat islet isolations, while human islet experiments were repeated using islets from n = 3 distinct donors to validate trends. Unless specifically indicated otherwise, values were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical tests included Mann-Whitney for mechanical tests and one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons for islet assessment data. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05 with designations of ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; and *p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Acellurity and ECM Composition in Decellularized Porcine Tissue

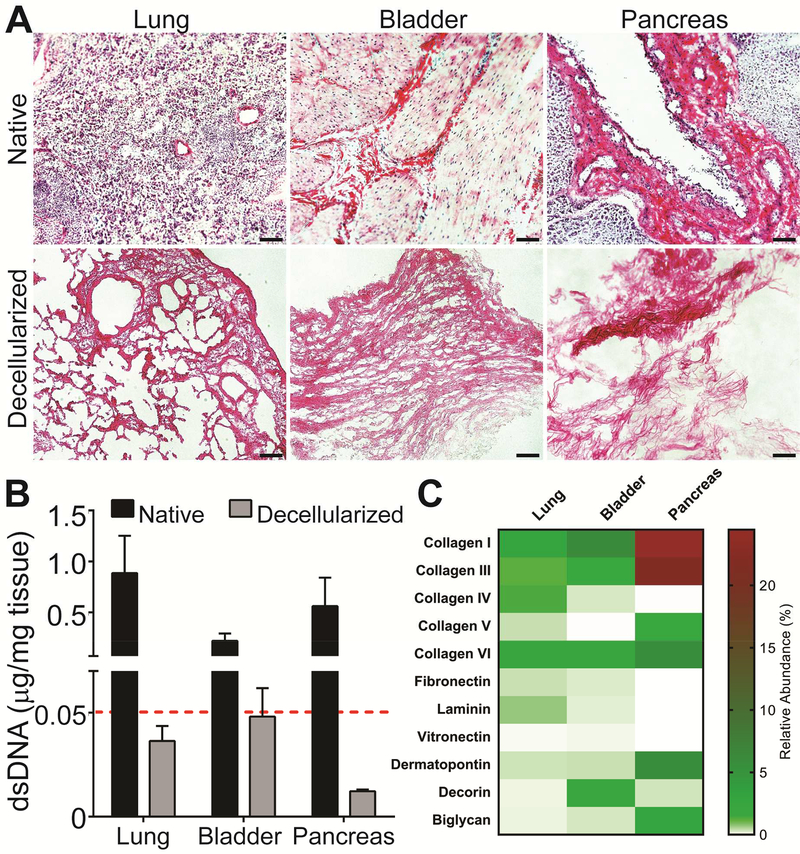

To obtain high-quality decellularized tissues used for cell culture, the decellularization process must be carefully optimized. While removal of donor cellular components is needed to mitigate immunogenicity, the integrity and bioactivity of the ECM are subject to degradative loss if a harsh decellularization process is used [43–45]. To optimize this balance for this study, a combination of published decellularization approaches, including osmotic burst, freeze and thaw cycles, mechanical disruption, and moderate enzymatic treatment, were strategically employed [26, 34–36]. Following the decellularization process, all tissues exhibited tissue-specific fibrous structures but were cell-free, with dsDNA contamination below recommended guidelines (e.g. < 0.05 μg DNA / mg tissue) (Figure 2A-B) [26]. NanoLC-MS analysis characterized the ECM composition of dominant proteins with results expressed as relative abundance of identified proteins, as classified by the mean ion signal peak area of top three intense peptide ion signals in the downstream protein analysis. A variable composition of the major ECM components was observed for the three decellularized tissues, with gradients in the percentage of BM-related proteins and proteoglycans (Figure 2C & Table S1). The pancreas was comprised primarily of collagen I (24.45 ± 3.10%), followed by collagen III, dermatopontin, collagen IV, and biglycan. Compared to the pancreas ECM relative composition, bladder tissue exhibited less collagen I and collagen III (at 6.10 ± 0.51%, and 1.69 ± 0.15 respectively); however, the relative contribution from collagen IV was higher (0.18 ± 0.02% for bladder versus 0.01 ± 0.001% for the pancreas). The bladder also contained increased levels of decorin (1.86 ± 0.13%). In contrast, the lung had the lowest overall percentage of primary collagen proteins, at 6.89% compared to 10.44% and 50.51% for bladder and pancreas, respectively.

Figure 2.

Biochemical characterization of native and decellularized porcine tissues. A) H&E staining of native (top row) and decellularized (bottom row) tissues. Scale bar = 100 μm B) DNA quantitation comparing native to decellularized tissues presented as DNA (μg) normalized to dry weight tissue (mg). Red line = recommended threshold for decellularized tissues (0.05 μg/mg tissue). C) Major ECM components of decellularized lung, bladder and pancreas, identified and relatively quantified using nanoLC-MS, are presented as relative abundance (%) of detected proteins, as shown on heatmap. Color gradient bar = % of total proteins (see Table S1 for values).

3.2. Biomechanical Characterization of Decellularized ECM Hydrogels

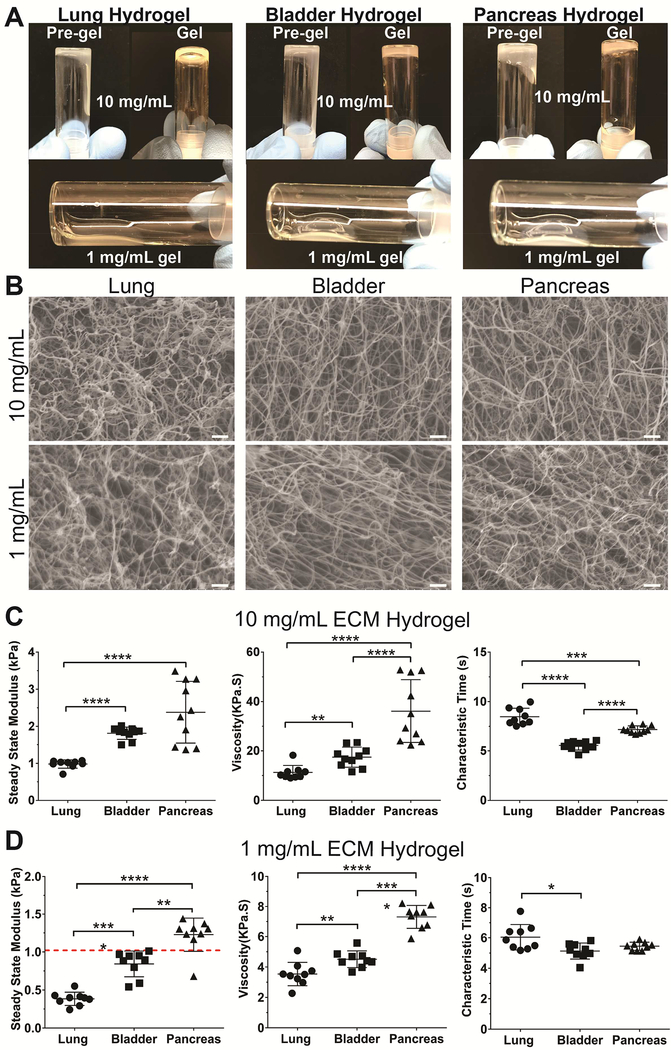

Decellularized ECM solutions (10 and 1 mg/mL) formed nanofibrous hydrogels following the adjustment of pH and temperature to 7.4 and 37°C, respectively (Figure 3A-B). Resulting gels were easily handled and visually stable for over 90 days, when incubated in a buffered solution at 37°C. The viscoelastic properties of the resulting ECM hydrogels were evaluated using a cantilever-based indenter [39]. Distinct mechanical properties were observed for ECM hydrogels formed from the three different tissue sources (Figure 3C-D). Both the steady-state modulus, which describes solid-like properties, and the viscosity, which characterizes relaxation behavior, were higher for pancreas-sourced ECM hydrogels, followed by the bladder and then lung. The characteristic time, which defines the efficiency of gel relaxation toward its steady-state modulus, was similar across the various hydrogels. Of note, the modulus of the 1 mg/mL porcine pancreatic ECM hydrogel (1.227 ± 0.09 kPa) was statistically identical to that reported for normal human pancreas tissues (1.06 ± 0.25 kPa) (Figure 3D) [39].

Figure 3.

Mechanical characterization of viscoelastic properties of ECM-based hydrogels fabricated from decellularized porcine tissues. A) Visual transition from solution to hydrogel observed for lung, bladder and pancreas ECM sources at 10 mg/mL, with diluted hydrogels formed at 1 mg/mL. B) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of 10 mg/mL and 1 mg/mL ECM hydrogels showing nanofibrous structures. Scale bar =1 μm. The steady-state moduli, viscosities and characteristic time of 10 (B) and 1 mg/mL (C) hydrogel, as measured via Hertz contact and SLS model. Dashed red line = reported steady state modulus of normal human pancreatic tissue [39]. P-values were calculated using Mann-Whitney tests. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P< 0.005; **** P< 0.001.

3.3. Evaluation of Endotoxin Levels in ECM Hydrogels

Endotoxins can incite detrimental impacts on encapsulated cells, such as the activation of intra-islet cytokine production and apoptosis; therefore, in situ endotoxin quantification was conducted for all three tissue sources. Endotoxin levels for the bladder and pancreas were at 0.934 ± 0.017 EU/mL and 0.215 ± 0.125 EU/mL, respectively. Lung ECM endotoxin levels, however, were substantially higher at 3.601 ± 1.208 EU/mL. While this amount is similar in scale as that for the islet isolation enzyme Liberase (3.1 EU/mL; Roche) [46, 47], lung ECM was excluded from the cellular encapsulation studies.

3.4. Impact of ECM Hydrogel Encapsulation on Rodent Islet Viability and Function

To examine the impact of ECM hydrogels on islet culture, pancreatic rat islets were encapsulated within 1 mg/mL pancreas or bladder ECM hydrogels two days post-isolation. As rat islets typically decline in function when cultured under standard conditions after ~ 4 d, assessments were conducted 5 d post-isolation. As a control, islets from the same isolation were cultured via standard methods (freely suspended in non-adherent dishes) for the same time period (termed “free islets”). By employing this time point and directly comparing free islets to those encapsulated within hydrogels, the capacity of ECM to preserve islet function could be distinctly characterized.

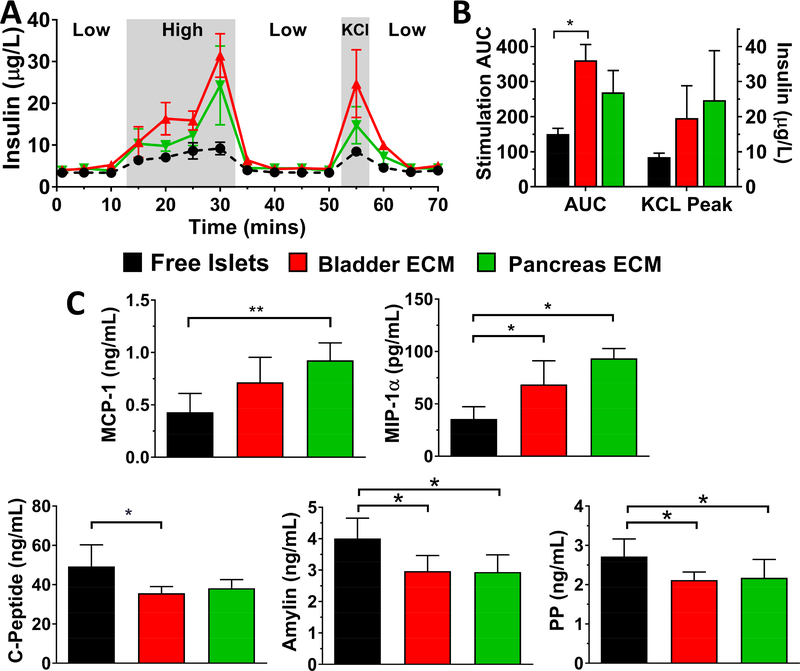

Overall islet viability, as visually characterized via viability staining and confocal microscopy, was high for all culture conditions; however, control islets cultured in nonadherent petri dishes exhibited elevated islet clumping and increased caspase-3/7 positive apoptotic cores over time (see Figure S1). To capture the impact of the ECM hydrogel encapsulation on the responsiveness of the islets to a glucose challenge after extended culture, dynamic glucose stimulation was conducted. In this manner, free and ECM encapsulated islets were exposed to temporal changes in glucose concentrations (i.e. low (3 mM), high (11 mM), and then low (3 mM)) and the perifused media was collected every minute. This method provides more information regarding the dynamics of glucose stimulation and insulin secretion, when compared to the standard static assay [48]. To characterize the amount of insulin within the islet following glucose stimulation, islets were then treated with KCl, which results in a burst release of insulin due to membrane depolarization. As shown on Figure 4A, rat islets cultured via standard culture methods (free islets) exhibited only a modest response to the glucose challenge, with an area under the curve (AUC) during the high glucose phase of 150.1 ± 16.3 and a modest insulin release following KCl-induced membrane depolarization (peak insulin 8.44 ± 1.15 μg/L) (Figure 4B). In contrast, rat islets encapsulated in bladder and pancreas hydrogels displayed elevated insulin secretion during high glucose stimulation (AUC = 361 ± 45 and 270 ± 62, respectively) and KCl depolarization (peak insulin 19.6 ± 9.2 and 24.74 ± 14.1 μg/L, respectively). Of note, the low response from free islet controls was not due to poor islet quality, as these islets exhibited a robust insulin response to glucose 24 h post-isolation (stimulation index of 2.89 ± 0.32).

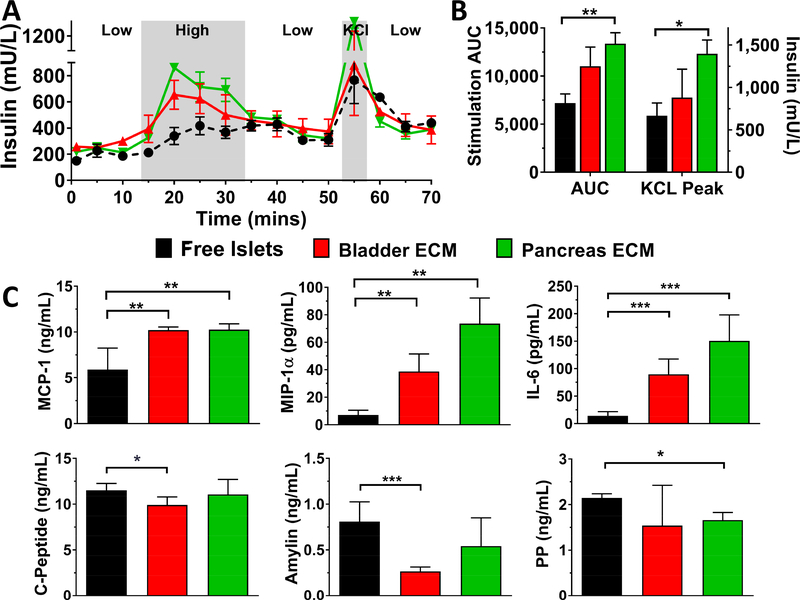

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the effect of porcine ECM hydrogels on rat islet glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) and cytokine and hormone secretion. The data shown is representative of three independent rat islet preparations. Islet function (A) after 5 d culture was evaluated using dynamic perfusion-based GSIR, with low glucose, high glucose, low glucose, KCl, and low glucose solution. Insulin levels are presented as mean ± SEM. B) Average stimulation area under curve (AUC) during high glucose solution and peak insulin levels during KCl stimulation. C) Significantly altered cytokine and hormone secretion following 3 d culture freely or within ECM hydrogels. Statistical significance was determined as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01

In addition to acute stimulation, the basal secretion of rat cytokine and metabolic hormones during culture was also characterized via multiplexed immunoassays. While secreted levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-4, IL-1β, and TNF-α were significantly reduced when islets were encapsulated with bladder and pancreas ECM hydrogels for one isolation study, this trend was not consistent across all three preparations. Chemotactic MIP-1α and MCP-1, however, were significantly and consistently increased (Figure 4C). For metabolic hormone activity, a consistent reduction of c-peptide, amylin, and PP was observed in ECM co-cultured rat islets in comparison to free islets.

3.5. Alterations in Cellular Composition and Morphology for ECM Encapsulated Rat Islets

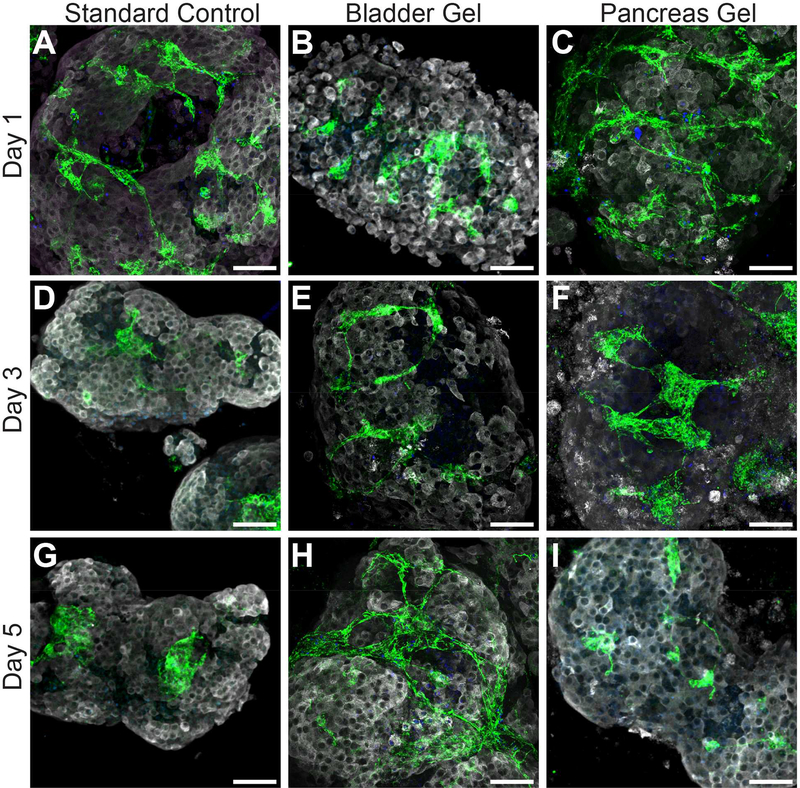

To characterize the impact of the ECM hydrogel on rat islet cellular composition and morphology, whole-mount immunofluorescent images were collected. As shown in Figure 5, peripheral islet-resident endothelial cells (iEC) were strongly detected for all culture conditions 1 d post-isolation, as indicated via CD31+ staining. During the extended culture of free islets under standard culture conditions, however, the quantity and morphology of these resident iEC appear modified, with a decrease in presence and a clustering of residual cells. In contrast, the interconnected morphology and level of iEC for islets within bladder and pancreas ECM hydrogels appears retained over the 5 d culture period (Figure 5H and I). In addition, sprouting structures were observed emerging from islets cultured within ECM hydrogels during the culture period; a phenomenon that was not seen in the free islet control group (Figure S1). These protrusions appear to support the proliferation and expansion of intra-islet resident supportive cells. These cells were further characterized in human islet cultures.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the effect of porcine ECM hydrogels on cellular phenotypic distribution of islet-resident CD31+ endothelial cells (iEC) within pancreatic rat islets following 1, 3 and 5 d culture under standard culture conditions or encapsulated within bladder or pancreas ECM. (Insulin: white; CD31: green). Scale bar = 50 μm.

3.6. Impact of ECM Hydrogel Encapsulation on Human Islet Viability and Function

To investigate the translatability of these observations to human-sourced cells, human islets were procured and screened within porcine bladder and pancreas ECM hydrogels. For each isolation, human islets were encapsulated within hydrogels after overnight culture following delivery; however, the delivery times varied from 2 to 3 d post-isolation.

Free human islets exhibited variable spheroidal aggregation over the in vitro culture, but this did not translate to significant changes in cell death or apoptotic markers (Figure S2). To examine gel stability over time when encapsulating cells, human islets were encapsulated and visual inspection of gels for extended culture times (over 80 days) was conducted. ECM gels retained stability over culture with full 3-D support of the embedded islets and retention of islet viability (Figure S3). Over this extended culture time, however, ECM hydrogels containing human islets exhibited moderate gel volume consolidation.

As with rat islets, islet function was characterized via perifusion GSIR. As human islets retain their glucose responsiveness longer in culture than rodent islets [49], culture times were extended to 1 week post-encapsulation. As shown in Figure 6, human islets cultured via standard methods exhibited only a modest response to the glucose challenge, with an area under the curve (AUC) during the high glucose phase of 7,192 ± 1,899, and a moderate insulin release following KCl-induced membrane depolarization (peak insulin 766.2 ± 445.7 mU/L). In contrast, human islets encapsulated in bladder and pancreas hydrogels displayed elevated insulin secretion during high glucose stimulation (AUC = 11,031 ± 3,981 and 13,373 ± 2,277, respectively) and KCl depolarization (peak insulin 881 ± 667 and 1,396 ± 327 mU/L, respectively). Overall, human islets encapsulated within 1 mg/mL pancreatic ECM hydrogels exhibited a statistically significant elevation in glucose response to insulin (P = 0.006), as well as to KCl depolarization (P = 0.017). Of note, this disparity in islet function for free islets was only measured for later culture periods, as earlier culture times (e.g. 4 post-encapsulation) illustrated no differences in GSIR between groups (see Figure S4). Trends were consistent across all three islet isolations.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the effect of porcine ECM hydrogels on human islets glucose stimulated insulin release (GSIR) and cytokine and hormone secretion. The data shown is representative of three independent experiments from three human islet donors. Islet function (A) after 7 d of culture was evaluated using dynamic perfusion-based GSIR of low glucose, high glucose, low glucose, KCl, and low glucose solution. Insulin levels are presented as mean ± SEM. B) Average stimulation area under curve (AUC) during high glucose solution and peak insulin levels during KCl stimulation. C) Significantly altered cytokine and hormone secretion following 3 d culture freely or within ECM hydrogels. Statistical significance was determined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005

The impact of ECM hydrogels on the basal secretion of cytokine and metabolic hormones during culture was also characterized from the three human donor islet preparations. For all preparations, a significant increase of detectable MCP-1 and MIP-1 was observed for human islets encapsulated within bladder and pancreas ECM hydrogels (Figure 6C), when compared to the free islet controls. Of interest, IL-6 secretion was also elevated for ECM encapsulated islets. Further, a modest, but significant, reduction of c-peptide (P = 0.014) and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) was measured for bladder and pancreas hydrogels, respectively, when compared to free human islets after 7 d culture, while the reduction in amylin was more pronounced for islets within bladder hydrogels (P < 0.001). Other proteins from multiplexed assays were not significantly and/or consistently altered across all three human islet donors.

3.7. Alterations in Cellular Composition and Morphology for ECM Encapsulated Human Islets

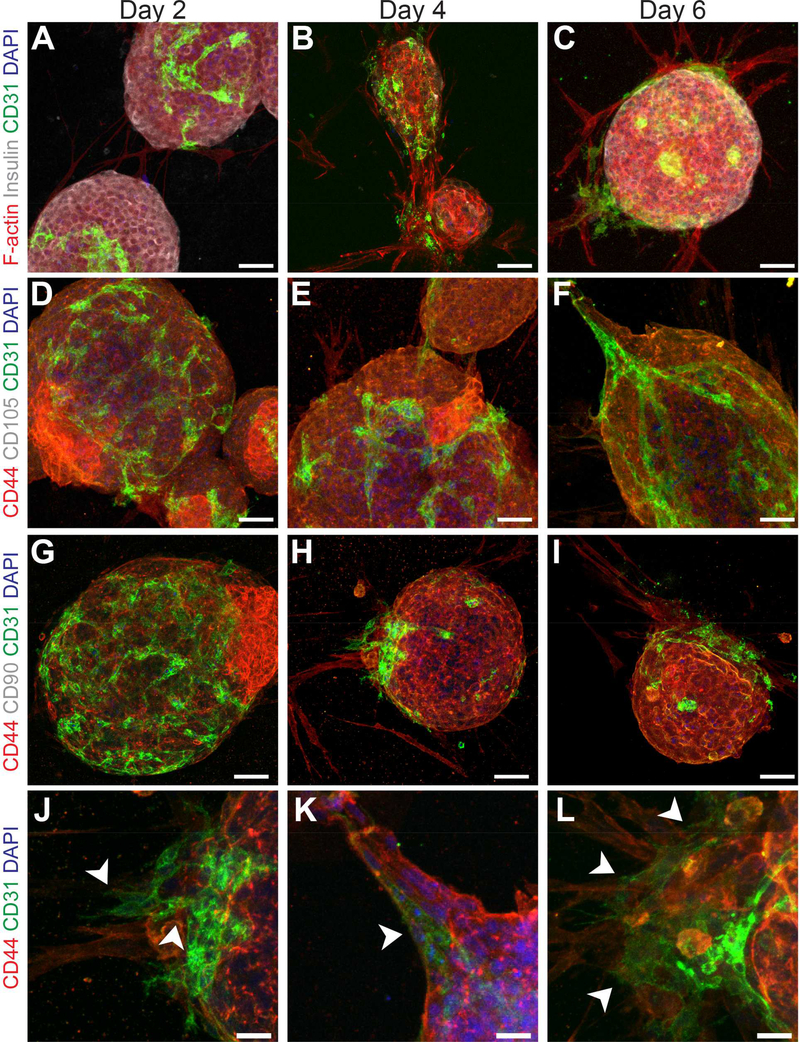

The cellular phenotype and morphology of human islets, freely cultured or encapsulated within ECM hydrogels, were tracked over the course of 1 week and visualized via whole-mount immunohistological characterization. Extensive time-course imaging focused on islets within pancreas ECM, given their favorable insulin secretion profiles. Similar to rodent islets, human islets cultured in pancreas ECM hydrogels exhibited a higher expression of interconnected CD31+ iEC, when compared to freely cultured islets (Figure 7A-C). Sprout-like protrusions at the periphery of the spheroidal cluster were also observed within hydrogels. These branching structures extended from the islet after only 16 hrs post-encapsulation and continued for the duration of the culture period (Figure S5 & Supporting Documents Video). Characterization of the cellular composition of these sprouts indicated these insulin-negative cells were primarily CD44+/CD31−/CD105−/CD90− and F-actin+ (Figure 7 A-I), although some CD44−/CD31+/CD105−/CD90− cells appeared to co-extend on the outer sheath of the primary cellular sprout after 4 d in culture (Figure 7, J-L). These structures were not observed when islets were freely cultured in standard non-adherent dishes (Figure S2).

Figure 7.

Characterization of islet-resident CD31+ endothelial cells (iEC) and the cellular composition of sprout-like protrusions from human islets following 2, 4 and 6 d culture within pancreas ECM hydrogels. Clusters were co-stained for A-C) F-actin (red), insulin (white), and CD31 (green); D-F) CD44 (red), CD105 (white), and CD31 (green); G-I) CD44 (red), CD90 (white), and CD31 (green). Scale bar = 50 μm. J-L) Higher magnification images of CD31+ and CD44+ cells extending from the islet spheroid after 4 d of culture. Scale bar = 20 μm.

4. Discussion

In this study, 3-D physiomimetic porcine ECM hydrogels were developed to recapitulate critical islet adhesion junctions in an effort to preserve islet stability in culture. Given the anatomical and physiochemical complexities of the different tissues tested, distinct decellularization strategies were employed to remove highly immunogenic cells with minimal protein loss [26, 50]. Low remnant DNA found in decellularized tissues demonstrated effective cellular removal, thereby reducing potential immunogenicity [51]. Characterization of protein composition via proteomic analysis found tissue-specific variances in ECM protein composition for the various tissue sources, where the decellularized pancreas contained mostly structural ECMs (e.g. collagen I, III and dermatopontin) and the lung exhibited higher BM-associated ECM (e.g. collagen IV, fibronectin and laminin). The flexibility in ECM composition may be advantageous in customizing hydrogels to optimize islet outcomes, as it is known that islets exhibit distinct peri-islet ECM compositions and ECM-binding integrins depending on their species of origin [12, 52, 53].

While mechanical properties have a profound influence on cell behavior [54], matricrine signaling from ECM binding sites and tethered matricellular proteins also influence cell phenotype and function. The mechanical properties of the resulting gels were evaluated using a custom indentation system that enables direct comparison of hydrogels to resected tissues [39]. A higher steady-state modulus and viscosity were measured for pancreas ECM hydrogels when compared to the other tissues, which likely reflects its observed higher concentration of collagens I and III [55]. Furthermore, stable ECM hydrogels that visually retained their structure up to 3 months post-gelation could be formed at variable concentrations (10 to 1 mg/mL), serving to modulate interior porosities and mechanics without the need for cytotoxic cross-linkers or acids [56, 57]. The 1 mg/mL pancreas hydrogel also exhibited mechanical characteristics similar to a healthy human pancreas. Although the impact of hydrogel mechanical properties on pancreatic islets has not been fully characterized to date, the capacity of these reconstituted ECM hydrogels to mimic native mechanical properties is encouraging, as they may also preserve aspects of in vivo matricrine signaling.

Another critical aspect in evaluating the suitability of decellularized tissues for cellular encapsulation is the quantification of endotoxin contamination, as this can lead to elevated islet inflammatory cytokine production [47, 58]. FDA guidance documents set the limit of endotoxin contamination for medical devices or parental drugs at extraction concentrations of 0.5 EU/mL; however, extraction and elution screens do not fully capture the degree of contamination due to endotoxin’s propensity to adhere to material surfaces [46]. Herein, an in situ LAL chromogenic kinetic assay was used, resulting in a more stringent characterization [59]. Of concern, lung ECM gels exhibited high levels of contamination, over 7-fold higher than FDA extract recommendations and up to 16-fold higher than that detected in the other tissue sources. While additional cleansing via terminal sterilization (e.g. gamma-irradiation and ethylene oxide) could decrease this contamination, resulting gels would likely exhibit compromised mechanical and biochemical integrity, as well as diminished cellular adhesion [60, 61]. Overall, this tissue source variability, despite the use of aseptic techniques and supplemental antibiotics throughout the decellularization process, highlights the importance of this characterization for all ECM studies.

Results following the encapsulation of human and rat islets within bladder and pancreas ECM hydrogels indicate these hydrogels provide a 3-D supportive microenvironment for in vitro culture. ECM-containing constructs aided in the maintenance of the spatial dispersion and physical integrity of cultured islets, avoiding islet clumping and the instigation of anoikis-induced apoptosis stress [62, 63]. While beneficial in static culture, these features are also desirable within microfluidic platforms, where flow patterns may further disrupt islet distribution and lead to islet agglomeration.

When examining the impact of ECM hydrogel encapsulation on retaining islet function, differences in islet species and culture time emerged. Both bladder and pancreas ECM sources resulted in elevated retention of rat islet function 5 d post-isolation. Human islets, with longer retention of GSIR in vitro, were tested 7 d post-encapsulation or up to 10 d post-isolation [64]. As islets in culture gradually decline in functionality over time, the assessment time points selected for each species in this study correlated with times that islets would typically exhibit poor functionality [49, 65]. While ECM hydrogels did not enhance the initial function of the isolated islets, results found islet encapsulation within ECM hydrogels preserve their function for extended culture periods. Retention of these features is essential for translation into islet-on-achip devices for continuous culture and characterization [66–69].

The paracrine response of islets to ECM hydrogels was evaluated via multiplexed cytokine and metabolic hormone analyses. The production of most inflammatory cytokines was not consistently affected by ECM hydrogels, except for MIP-1α and MCP-1 for rat and human islets and IL-6 from human islets. The variability in the baseline inflammatory cytokine response from different isolations may be due to variations in islet isolation reagents and exposure, which can vary in endotoxin contamination and the duration of the enzymatic procedure, as well as organ quality and shipment stress (for human islets) [47, 58, 70]. The increased cytokine production of selected factors within ECM hydrogels may suggest an augmented inflammatory response to the decellularized material, which may be due to residual porcine dsDNA or other factors [44]; however, the selected upregulation of only these three cytokines does not indicate typical islet inflammatory activation [71, 72]. Of interest, MCP-1 (CCL-2) secretion from isolated human islets has been associated with enhanced glucose responsiveness and restoration of the peri-islet ECM capsule post-isolation, indicating this profile may represent a beneficial effect [73, 74]. Further, increased secretion of these cytokines within ECM hydrogel cultures may be attributed to the increased presence of islet-resident pro-angiogenic CD31+ endothelial cells and fibroblast-like cells [75–78].

The metabolic hormone profile of both rodent and human islets within ECM hydrogels exhibited similar trends, with decreased basal c-peptide, pancreatic polypeptide, and amylin secretion, when compared to free islet controls. The modest decline in the secretion levels of c-peptide, the by-product of insulin processing, and pancreatic polypeptide, a hormone released by pancreatic polypeptide cells, under basal glucose culture conditions indicates decreased secretory responses to basal glucose levels [79–81]. This decreased sensitivity may contribute to the observed increased responsiveness of these islets to a glucose challenge, as well as the detected elevated overall insulin content. While amylin and insulin typically exhibit parallel secretion profiles, basal amylin hyposecretion has been reported during extended islet culture and in pathophysiological conditions of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, such as early Type 2 diabetes [82, 83]. Further, amylin accumulation within the islet, either due to elevated production and secretion and/or defective trafficking/processing, has been associated with increased beta cell dysfunction and death [84, 85]. Thus, the measured decline in amylin secretion may correlate with preservation of islet function and survival in culture.

While the trends observed for cytokines and hormone secretion during culture for rat and human islets within ECM hydrogels exhibits a unique signature, measurements may be impacted by the presence of the hydrogel. As many secretory factors exhibit binding sites for ECM motifs, it cannot be discounted that the ECM may impair release of these factors into the surrounding media. This, coupled with the known cellular binding sites of these agents, prevents definitive interpretations of these results.

When encapsulating multicellular organs within ECM hydrogels, variations in cellular morphology, adhesion, migration, and proliferation can occur [86]. In this pancreatic islet study, alterations in the cellular composition and morphology of resident non-endocrine cells were observed. Specifically, CD31+ iECs exhibited increased presence and interconnectivity when contained within hydrogels. Furthermore, the proliferation of CD44+/CD31−/CD105−/CD90−/F-actin+ cells was noted, with the formation of sprout-like structures emerging from the islet spheroid. The extension of these fibroblast-like cells appears to serve as conduits for subsequent EC migration, which is in line with published reports [87–89]. Fibroblast-like cells also secrete factors that modulate the growth and stability of these capillary sprouts within natural hydrogels [87–89].

It has been reported that retention of iECs, as well as other cell types such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and resident fibroblasts, assist in the preservation of islet function in culture, as well as efficacy in animal models [17, 18, 90–94]. Furthermore, inter-islet sprouts can serve as channels for additional paracrine stimulation [95]. To this end, groups have sought to retain these cells and promote capillary-like sprouting by supplementation with growth factors (e.g. FGF-2, VEGF, TNF-α) or cells (e.g. MSC or EC) or by culturing islets under stressful conditions such as hyperglycemia and hypoxia [94–96]. Herein, ECM hydrogels support the generation and maintenance of these sprout structures without the use of external agents or undesirable culture conditions.

While the developed ECM hydrogel-islet system is promising, islet agglomeration and contraction of the gels was observed during extended culture (> 10 d), likely due to anisotropic forces generated from adhesion and extension of fibroblast-like cells on the ECM [97]. Modifications in ECM properties that support consistent structural and mechanical properties should be considered in further optimization of this ECM-based biomaterial platform [98, 99]. The biochemical and mechanical properties of these hydrogels could be improved via integration with other materials, such as PEG, or integration within inert scaffoldings. Further, combinations of ECM tissue sources (e.g. pancreas with lung) could generate an optimal ECM composition that more closely resembles native islet BM.

Ultimately, this ECM hydrogel and islet co-culture system can be incorporated with a microfluidic platform to further mimic the physiological microenvironment of native islet niche. Combining microfluidic flow with 3-D ECM support could synergistically support both islet health and retention of beneficial resident non-endocrine cells, as perfusion has been shown to enhance promote these effects [100]. Therefore, we envision that the versatile 3-D physiomimetic ECM hydrogels can be engineered to support islet function in multiple in vitro platforms.

5. Conclusion

ECM hydrogels, sourced from decellularized bladder or pancreas tissues, supported long-term human and rat islet culture, with preservation of glucose stimulated insulin release. These multi-cellular mini-organs further exhibited dynamic interactions with the 3-D ECM hydrogel, forming protrusions during culture, comprised of fibroblast-like sprouts that served as conduits for endothelial cell extensions. Decellularized ECM hydrogels provide a unique supportive 3-D microenvironment that can be easily incorporated within islet-on-a-chip devices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the NIDDK-supported Human Islet Research Network (HIRN, RRID:SCR_014393; https://hirnetwork.org; UC4 DK104208) and JDRF (SRA-2017-347-M-B). Human pancreatic islets were provided by the NIDDK-funded Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) at City of Hope (2UC4DK098085). We thank Irayme Labrada for her excellent technical assistance during rat islet procurement. We thank Dr. John Driver from the UF Department of Animal Science for assistance in procurement of porcine tissues. We thank Kimberly Backer-Kelley and Karen Kelley from Electron Microscopy Core of Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research at University of Florida for developing the SEM protocol and imaging assistance. We also thank Shachi Patel, Ying Li, Xiongjian Chen and Yangjunyi Li from UF Department of Biomedical Engineering for their experimental assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- [1].Kurokawa YK, George SC, Tissue engineering the cardiac microenvironment: Multicellular microphysiological systems for drug screening, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 96 (2016) 225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, Ingber DE, Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip, Science 328(5986) (2010) 1662–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wagner I, Materne E-M, Brincker S, Süßbier U, Frädrich C, Busek M, Sonntag F, Sakharov DA, Trushkin EV, Tonevitsky AG, A dynamic multi-organ-chip for long-term cultivation and substance testing proven by 3D human liver and skin tissue co-culture, Lab Chip 13(18) (2013) 3538–3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang B, Montgomery M, Chamberlain MD, Ogawa S, Korolj A, Pahnke A, Wells LA, Massé S, Kim J, Reis L, Biodegradable scaffold with built-in vasculature for organ-on-a-chip engineering and direct surgical anastomosis, Nat Mat 15(6) (2016) 669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Silva PN, Green BJ, Altamentova SM, Rocheleau JV, A microfluidic device designed to induce media flow throughout pancreatic islets while limiting shear-induced damage, Lab Chip 13(22) (2013) 4374–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee SH, Hong S, Song J, Cho B, Han EJ, Kondapavulur S, Kim D, Lee LP, Microphysiological Analysis Platform of Pancreatic Islet β‐Cell Spheroids, Adv Healthc Mater 7(2) (2018) 1701111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yi L, Wang X, Dhumpa R, Schrell AM, Mukhitov N, Roper MG, Integrated perfusion and separation systems for entrainment of insulin secretion from islets of Langerhans, Lab Chip 15(3) (2015) 823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lenguito G, Chaimov D, Weitz JR, Rodriguez-Diaz R, Rawal SA, TamayoGarcia A, Caicedo A, Stabler CL, Buchwald P, Agarwal A, Resealable, optically accessible, PDMS-free fluidic platform for ex vivo interrogation of pancreatic islets, Lab Chip 17(5) (2017) 772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xing Y, Nourmohammadzadeh M, Elias JE, Chan M, Chen Z, McGarrigle JJ, Oberholzer J, Wang Y, A pumpless microfluidic device driven by surface tension for pancreatic islet analysis, Biomed Microdevices 18(5) (2016) 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Becker MW, Simonovich JA, Phelps EA, Engineered microenvironments and microdevices for modeling the pathophysiology of type 1 diabetes, Biomaterials in press (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Daoud J, Petropavlovskaia M, Rosenberg L, Tabrizian M, The effect of extracellular matrix components on the preservation of human islet function in vitro, Biomaterials 31(7) (2010) 1676–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Phelps EA, Cianciaruso C, Santo-Domingo J, Pasquier M, Galliverti G, Piemonti L, Berishvili E, Burri O, Wiederkehr A, Hubbell JA, Baekkeskov S, Advances in pancreatic islet monolayer culture on glass surfaces enable super-resolution microscopy and insights into beta cell ciliogenesis and proliferation, Sci Rep 7 (2017) 45961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cheng JY, Raghunath M, Whitelock J, Poole-Warren L, Matrix components and scaffolds for sustained islet function, Tissue Eng Part A 17(4) (2011) 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stendahl JC, Kaufman DB, Stupp SI, Extracellular matrix in pancreatic islets: relevance to scaffold design and transplantation, Cell Transplant 18(1) (2009) 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosenberg L, Wang R, Paraskevas S, Maysinger D, Structural and functional changes resulting from islet isolation lead to islet cell death, Surgery 126(2) (1999) 393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Paraskevas S, Maysinger D, Wang R, Duguid WP, Rosenberg L, Cell loss in isolated human islets occurs by apoptosis, Pancreas 20(3) (2000) 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brissova M, Fowler M, Wiebe P, Shostak A, Shiota M, Radhika A, Lin PC, Gannon M, Powers AC, Intraislet endothelial cells contribute to revascularization of transplanted pancreatic islets, Diabetes 53(5) (2004) 1318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johansson M, Mattsson G.r., Andersson A, Jansson L, Carlsson P-O, Islet endothelial cells and pancreatic β-cell proliferation: studies in vitro and during pregnancy in adult rats, Endocrinology 147(5) (2006) 2315–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gittes GK, Galante PE, Hanahan D, Rutter WJ, Debase H, Lineage-specific morphogenesis in the developing pancreas: role of mesenchymal factors, Development 122(2) (1996) 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nagata N, Iwanaga A, Inoue K, Tabata Y, Co-culture of extracellular matrix suppresses the cell death of rat pancreatic islets, J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 13(5) (2002) 579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pinkse GG, Bouwman WP, Jiawan-Lalai R, Terpstra O, Bruijn JA, de Heer E, Integrin signaling via RGD peptides and anti-β1 antibodies confers resistance to apoptosis in islets of Langerhans, Diabetes 55(2) (2006) 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nikolova G, Jabs N, Konstantinova I, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Sorokin L, Fässler R, Gu G, Gerber H-P, Ferrara N, The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and β cell proliferation, Dev Cell 10(3) (2006) 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weber LM, Anseth KS, Hydrogel encapsulation environments functionalized with extracellular matrix interactions increase islet insulin secretion, Matrix Bio 27(8) (2008) 667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Daoud J, Rosenberg L, Tabrizian M, Pancreatic islet culture and preservation strategies: advances, challenges, and future outlook, Cell Transplant 19(12) (2010) 1523–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Badylak SF, Xenogeneic extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction, Transpl Immunol 12(3) (2004) 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF, An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes, Biomaterials 32(12) (2011) 3233–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Badylak SF, The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction, Semin Cell Dev Biol, Elsevier, 2002, pp. 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Goh S-K, Bertera S, Olsen P, Candiello JE, Halfter W, Uechi G, Balasubramani M, Johnson SA, Sicari BM, Kollar E, Perfusion-decellularized pancreas as a natural 3D scaffold for pancreatic tissue and whole organ engineering, Biomaterials 34(28) (2013) 6760–6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mirmalek-Sani S-H, Orlando G, McQuilling JP, Pareta R, Mack DL, Salvatori M, Farney AC, Stratta RJ, Atala A, Opara EC, Porcine pancreas extracellular matrix as a platform for endocrine pancreas bioengineering, Biomaterials 34(22) (2013) 5488–5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Singelyn JM, DeQuach JA, Seif-Naraghi SB, Littlefield RB, SchupMagoffin PJ, Christman KL, Naturally derived myocardial matrix as an injectable scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering, Biomaterials 30(29) (2009) 5409–5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Singelyn JM, Sundaramurthy P, Johnson TD, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Hu DP, Faulk DM, Wang J, Mayle KM, Bartels K, Salvatore M, Catheter-deliverable hydrogel derived from decellularized ventricular extracellular matrix increases endogenous cardiomyocytes and preserves cardiac function post-myocardial infarction, J Am Coll Cardiol 59(8) (2012) 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Faulk DM, Londono R, Wolf MT, Ranallo CA, Carruthers CA, Wildemann JD, Dearth CL, Badylak SF, ECM hydrogel coating mitigates the chronic inflammatory response to polypropylene mesh, Biomaterials 35(30) (2014) 8585–8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wolf MT, Carruthers CA, Dearth CL, Crapo PM, Huber A, Burnsed OA, Londono R, Johnson SA, Daly KA, Stahl EC, Polypropylene surgical mesh coated with extracellular matrix mitigates the host foreign body response, J Biomed Mater Res A 102(1) (2014) 234–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh S-K, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA, Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart, Nat Med 14(2) (2008) 213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Petersen TH, Calle EA, Zhao L, Lee EJ, Gui L, Raredon MB, Gavrilov K, Yi T, Zhuang ZW, Breuer C, Tissue-engineered lungs for in vivo implantation, Science 329(5991) (2010) 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brown BN, Valentin JE, Stewart-Akers AM, McCabe GP, Badylak SF, Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component, Biomaterials 30(8) (2009) 1482–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Al Shweiki MR, Mönchgesang S, Majovsky P, Thieme D, Trutschel D, Hoehenwarter W, Assessment of Label-Free Quantification in Discovery Proteomics and Impact of Technological Factors and Natural Variability of Protein Abundance, J Proteome Res 16(4) (2017) 1410–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Drabik A, Silberring J, Quantitative Measurements in Proteomics: Mass Spectrometry, Proteomic Profiling and Analytical Chemistry (Second Edition), Elsevier; 2016, pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rubiano A, Delitto D, Han S, Gerber M, Galitz C, Trevino J, Thomas RM, Hughes SJ, Simmons CS, Viscoelastic properties of human pancreatic tumors and in vitro constructs to mimic mechanical properties, Acta Biomater 67 (2018) 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moore SW, Keller RE, Koehl M, The dorsal involuting marginal zone stiffens anisotropically during its convergent extension in the gastrula of Xenopus laevis, Development 121(10) (1995) 3131–3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brady A-C, Martino MM, Pedraza E, Sukert S, Pileggi A, Ricordi C, Hubbell JA, Stabler CL, Proangiogenic hydrogels within macroporous scaffolds enhance islet engraftment in an extrahepatic site, Tissue Eng Part A 19(23–24) (2013) 2544–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pedraza E, Brady AC, Fraker CA, Molano RD, Sukert S, Berman DM, Kenyon NS, Pileggi A, Ricordi C, Stabler CL, Macroporous three-dimensional PDMS scaffolds for extrahepatic islet transplantation, Cell Transplant 22(7) (2013) 1123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wong ML, Griffiths LG, Immunogenicity in xenogeneic scaffold generation: antigen removal vs. decellularization, Acta Biomater 10(5) (2014) 1806–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Badylak SF, Decellularized allogeneic and xenogeneic tissue as a bioscaffold for regenerative medicine: factors that influence the host response, Ann Biomed Eng 42(7) (2014) 1517–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chaimov D, Baruch L, Krishtul S, Meivar-Levy I, Ferber S, Machluf M, Innovative encapsulation platform based on pancreatic extracellular matrix achieve substantial insulin delivery, J Control Release (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gorbet MB, Sefton MV, Endotoxin: the uninvited guest, Biomaterials 26(34) (2005) 6811–6817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Berney T, Molano RD, Cattan P, Pileggi A, Vizzardelli C, Oliver R, Ricordi C, Inverardi L, Endotoxin-Mediated Delayed Islet Graft Function Is Associated With Increased Intra-Islet Cytokine Production and Islet Cell Apoptosis, Transplantation 71(1) (2001) 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tomei AA, Manzoli V, Fraker CA, Giraldo J, Velluto D, Najjar M, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Ricordi C, Stabler CL, Device design and materials optimization of conformal coating for islets of Langerhans, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(29) (2014) 10514–10519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Daoud JT, Petropavlovskaia MS, Patapas JM, Degrandpre CE, DiRaddo RW, Rosenberg L, Tabrizian M, Long-term in vitro human pancreatic islet culture using three-dimensional microfabricated scaffolds, Biomaterials 32(6) (2011) 1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Takeshita F, Tanaka T, Matsuda T, Tozuka M, Kobiyama K, Saha S, Matsui K, Ishii KJ, Coban C, Akira S, Toll-like receptor adaptor molecules enhance DNA-raised adaptive immune responses against influenza and tumors through activation of innate immunity, J Virol 80(13) (2006) 6218–6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Li Q, Uygun BE, Geerts S, Ozer S, Scalf M, Gilpin SE, Ott HC, Yarmush ML, Smith LM, Welham NV, Proteomic analysis of naturally-sourced biological scaffolds, Biomaterials 75 (2016) 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wang RN, Paraskevas S, Rosenberg L, Characterization of integrin expression in islets isolated from hamster, canine, porcine, and human pancreas, J Histochem Cytochem 47(4) (1999) 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Deijnen J, Suylichem P, Wolters G, Schilfgaarde R, Distribution of collagens type I, type III and type V in the pancreas of rat, dog, pig and man, Cell Tissue Res 277(1) (1994) 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sarig U, Sarig H, Gora A, Krishnamoorthi MK, Au-Yeung GCT, deBerardinis E, Chaw SY, Mhaisalkar P, Bogireddi H, Ramakrishna S, Boey FYC, Venkatraman SS, Machluf M, Biological and mechanical interplay at the Macro- and Microscales Modulates the Cell-Niche Fate, Sci Rep 8(1) (2018) 3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Fratzl P, Collagen: structure and mechanics, Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Williams CG, Malik AN, Kim TK, Manson PN, Elisseeff JH, Variable cytocompatibility of six cell lines with photoinitiators used for polymerizing hydrogels and cell encapsulation, Biomaterials 26(11) (2005) 1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Nöth U, Rackwitz L, Heymer A, Weber M, Baumann B, Steinert A, Schütze N, Jakob F, Eulert J, Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in collagen type I hydrogels, J Biomed Mater Res A 83(3) (2007) 626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vargas F, Vives-Pi M, Somoza N, Armengol P, Alcalde L, Marti M, Costa M, Serradell L, Dominguez O, Fernandez-Llamazares J, Julian JF, Sanmarti A, PujolBorrell R, Endotoxin contamination may be responsible for the unexplained failure of human pancreatic islet transplantation, Transplantation 65(5) (1998) 722–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Keane TJ, Swinehart IT, Badylak SF, Methods of tissue decellularization used for preparation of biologic scaffolds and in vivo relevance, Methods 84 (2015) 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Matuska AM, McFetridge PS, The effect of terminal sterilization on structural and biophysical properties of a decellularized collagen‐based scaffold; implications for stem cell adhesion, J Biomed Mater Res B 103(2) (2015) 397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Freytes DO, Stoner RM, Badylak SF, Uniaxial and biaxial properties of terminally sterilized porcine urinary bladder matrix scaffolds, J Biomed Mater Res B 84(2) (2008) 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gaber AO, Fraga DW, Callicutt CS, Gerling IC, Sabek OM, Kotb MY, Improved in vivo pancreatic islet function after prolonged in vitro islet culture, Transplantation 72(11) (2001) 1730–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ihm SH, Matsumoto I, Zhang HJ, Ansite JD, Hering BJ, Effect of short‐term culture on functional and stress‐related parameters in isolated human islets, Transpl Int 22(2) (2009) 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bonner-Weir S, Taneja M, Weir GC, Tatarkiewicz K, Song K-H, Sharma A, O’Neil JJ, In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(14) (2000) 7999–8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Farilla L, Bulotta A, Hirshberg B, Li Calzi S, Khoury N, Noushmehr H, Bertolotto C, Di Mario U, Harlan DM, Perfetti R, Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibits cell apoptosis and improves glucose responsiveness of freshly isolated human islets, Endocrinology 144(12) (2003) 5149–5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mohammed JS, Wang Y, Harvat TA, Oberholzer J, Eddington DT, Microfluidic device for multimodal characterization of pancreatic islets, Lab Chip 9(1) (2009) 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Johansson U, Olsson A, Gabrielsson S, Nilsson B, Korsgren O, Inflammatory mediators expressed in human islets of Langerhans: implications for islet transplantation, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308(3) (2003) 474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Westwell-Roper C, Dai DL, Soukhatcheva G, Potter KJ, van Rooijen N, Ehses JA, Verchere CB, IL-1 Blockade Attenuates Islet Amyloid Polypeptide-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Release and Pancreatic Islet Graft Dysfunction, J Immunol 187(5) (2011) 2755–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Eizirik DL, Sammeth M, Bouckenooghe T, Bottu G, Sisino G, Igoillo-Esteve M, Ortis F, Santin I, Colli ML, Barthson J, Bouwens L, Hughes L, Gregory L, Lunter G, Marselli L, Marchetti P, McCarthy MI, Cnop M, The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: expression of candidate genes for type 1 diabetes and the impact of proinflammatory cytokines, PLoS Genet 8(3) (2012) e1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Piemonti L, Leone BE, Nano R, Saccani A, Monti P, Maffi P, Bianchi G, Sica A, Peri G, Melzi R, Human pancreatic islets produce and secrete MCP-1/CCL2: relevance in human islet transplantation, Diabetes 51(1) (2002) 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Pfleger C, Schloot NC, Brendel MD, Burkart V, Hogenkamp V, Bretzel RG, Jaeger C, Eckhard M, Circulating cytokines are associated with human islet graft function in type 1 diabetes, Clin Immunol 138(2) (2011) 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Didion SP, Cellular and Oxidative Mechanisms Associated with Interleukin-6 Signaling in the Vasculature, Int J Mol Sci 18(12) (2017) 2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Rackham CL, Chagastelles PC, Nardi NB, Hauge-Evans AC, Jones PM, King AJF, Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells maintains islet organisation and morphology in mice, Diabetologia 54(5) (2011) 1127–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Kwon HM, Hur S-M, Park K-Y, Kim C-K, Kim Y-M, Kim H-S, Shin H-C, Won MH, Ha K-S, Kwon Y-G, Lee DH, Kim Y-M, Multiple paracrine factors secreted by mesenchymal stem cells contribute to angiogenesis, Vasc Pharmacol	 63(1) (2014) 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Gray DW, The role of exocrine tissue in pancreatic islet transplantation, Transpl Int 2(1) (1989) 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Khan D, Vasu S, Moffett RC, Irwin N, Flatt PR, Influence of neuropeptide Y and pancreatic polypeptide on islet function and beta-cell survival, Biochim Biophys Acta 1861(4) (2017) 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Aragón F, Karaca M, Novials A, Maldonado R, Maechler P, Rubí B, Pancreatic polypeptide regulates glucagon release through PPYR1 receptors expressed in mouse and human alpha-cells, Biochim Biophys Acta 1850(2) (2015) 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Whiting L, Stewart KW, Hay DL, Harris PW, Choong YS, Phillips ARJ, Brimble MA, Cooper GJS, Glicentin‐related pancreatic polypeptide inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from the isolated pancreas of adult male rats, Physiol Rep 3(12) (2015) e12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Novials A, Sarri Y, Casamitjana R, Rivera F, Gomis R, Regulation of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide in Human Pancreatic Islets, Diabetes 42(10) (1993) 1514–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Gasa R, Gomis R, Casamitjana R, Rivera F, Novials A, Glucose regulation of islet amyloid polypeptide gene expression in rat pancreatic islets, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 272(4) (1997) E543–E549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Sanke T, Hanabusa T, Nakano Y, Oki C, Okai K, Nishimura S, Kondo M, Nanjo K, Plasma islet amyloid polypeptide (Amylin) levels and their responses to oral glucose in Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients, Diabetologia 34(2) (1991) 129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Marzban L, Tomas A, Becker TC, Rosenberg L, Oberholzer J, Fraser PE, Halban PA, Verchere CB, Small Interfering RNA–Mediated Suppression of Proislet Amyloid Polypeptide Expression Inhibits Islet Amyloid Formation and Enhances Survival of Human Islets in Culture, Diabetes 57(11) (2008) 3045–3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Rao N, Agmon G, Tierney MT, Ungerleider JL, Braden RL, Sacco A, Christman KL, Engineering an Injectable Muscle-Specific Microenvironment for Improved Cell Delivery Using a Nanofibrous Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel, ACS nano (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tille JC, Pepper MS, Mesenchymal cells potentiate vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vitro, Exp Cell Res 280(2) (2002) 179–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Montesano R, Pepper MS, Orci L, Paracrine induction of angiogenesis in vitro by Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts, J Cell Sci 105 ( Pt 4) (1993) 1013–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Villaschi S, Nicosia RF, Paracrine interactions between fibroblasts and endothelial cells in a serum-free coculture model. Modulation of angiogenesis and collagen gel contraction, Lab Invest 71(2) (1994) 291–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Johansson Å, Lau J, Sandberg M, Borg L, Magnusson P, Carlsson P-O, Endothelial cell signalling supports pancreatic beta cell function in the rat, Diabetologia 52(11) (2009) 2385–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Rabinovitch A, Russell T, Mintz DH, Factors from fibroblasts promote pancreatic islet B cell survival in tissue culture, Diabetes 28(12) (1979) 1108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Miki A, Narushima M, Okitsu T, Takeno Y, Soto-Gutierrez A, Rivas-Carrillo JD, Navarro-Alvarez N, Chen Y, Tanaka K, Noguchi H, Matsumoto S, Kohara M, Lakey JR, Kobayashi E, Tanaka N, Kobayashi N, Maintenance of mouse, rat, and pig pancreatic islet functions by coculture with human islet-derived fibroblasts, Cell Transplant 15(4) (2006) 325–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Liu H, Chen B, Lilly B, Fibroblasts potentiate blood vessel formation partially through secreted factor TIMP-1, Angiogenesis 11(3) (2008) 223–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kidszun A, Schneider D, Erb D, Hertl G, Schmidt V, Eckhard M, Preissner KT, Breier G, Bretzel RG, Linn T, Isolated pancreatic islets in three-dimensional matrices are responsive to stimulators and inhibitors of angiogenesis, Cell Transplant 15(6) (2006) 489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Johansson U, Rasmusson I, Niclou SP, Forslund N, Gustavsson L, Nilsson B, Korsgren O, Magnusson PU, Formation of composite endothelial cell-mesenchymal stem cell islets: a novel approach to promote islet revascularization, Diabetes 57(9) (2008) 2393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Linn T, Schneider K, Hammes HP, Preissner KT, Brandhorst H, Morgenstern E, Kiefer F, Bretzel RG, Angiogenic capacity of endothelial cells in islets of Langerhans, FASEB J 17(8) (2003) 881–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ray A, Lee O, Win Z, Edwards RM, Alford PW, Kim D-H, Provenzano PP, Anisotropic forces from spatially constrained focal adhesions mediate contact guidance directed cell migration, Nat Commun 8 (2017) 14923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Hoffman AS, Hydrogels for biomedical applications, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64 (2012) 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Annabi N, Nichol JW, Zhong X, Ji C, Koshy S, Khademhosseini A, Dehghani F, Controlling the porosity and microarchitecture of hydrogels for tissue engineering, Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16(4) (2010) 371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sankar KS, Green BJ, Crocker AR, Verity JE, Altamentova SM, Rocheleau JV, Culturing Pancreatic Islets in Microfluidic Flow Enhances Morphology of the Associated Endothelial Cells, PLOS ONE 6(9) (2011) e24904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.