Summary

Objective

To investigate the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of add‐on treatment of the triglycerides of heptanoate (triheptanoin) vs the triglycerides of octanoate and decanoate (medium chain triglycerides [MCTs]) in adults with treatment‐refractory epilepsy.

Methods

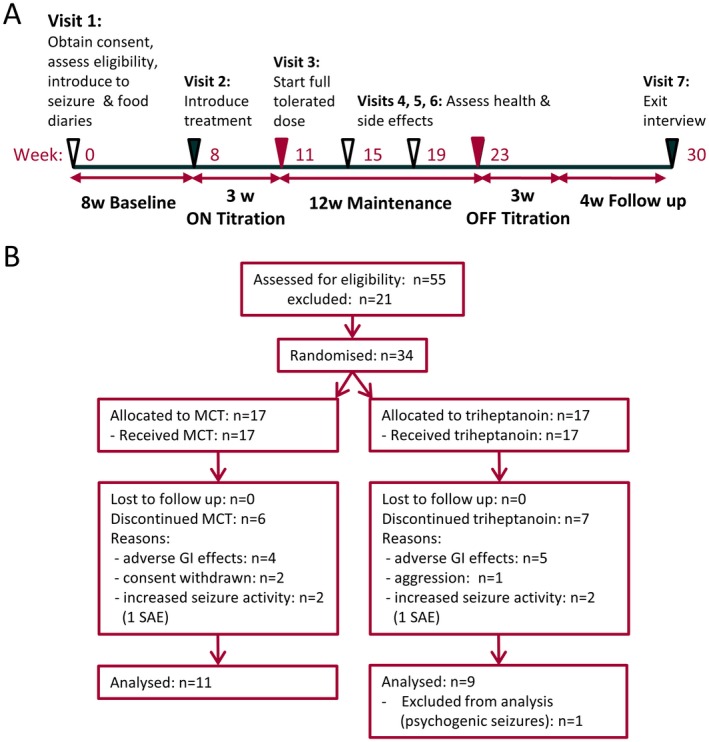

After an 8‐week prospective baseline period, people with drug‐resistant epilepsy were randomized in a double‐blind fashion to receive triheptanoin or MCTs. Treatment was titrated over 3 weeks to a maximum of 100 mL/d to be distributed over 3 meals and mixed into food, followed by 12‐week maintenance before tapering. The primary aims were to assess the following: (a) safety by comparing the number of intervention‐related adverse events with triheptanoin vs MCT treatment and (b) adherence, measured as a percentage of the prescribed treatment doses taken.

Results

Thirty‐four people were randomized (17 to MCT and 17 to triheptanoin). There were no differences regarding (a) the number of participants completing the study (11 vs 9 participants), (b) the time until withdrawal, (c) the total number of adverse events or those potentially related to treatment, (d) median doses of oils taken (59 vs 55 mL/d, P = 0.59), or (e) change in seizure frequency (54% vs 102%, P = 0.13). Please note that people with focal unaware seizures were underrepresented in the triheptanoin treatment arm (P = 0.04). The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal disturbances (47% and 62.5% of participants). Five people taking on average 0.73 mL/kg body weight MCTs (0.64 mL/kg median) and one person taking 0.59 mL/kg triheptanoin showed >50% reduction in seizure frequency, specifically focal unaware seizures.

Significance

Add‐on treatment with MCTs or triheptanoin was feasible, safe, and tolerated for 12 weeks in two‐thirds of people with treatment‐resistant epilepsy. Our results indicate a protective effect of MCTs on focal unaware seizures. This warrants further study.

Keywords: anaplerosis, focal unaware seizure, medium chain triglyceride, TCA cycle

1.

Key Points.

MCTs and triheptanoin add‐on treatment (45‐75 mL/d, interquartile range [IQR]) was tolerated in about two‐thirds of adults with refractory epilepsy

Adverse effects consisted mostly of nonserious gastrointestinal problems, but not neurocognitive effects, except for headaches

Five people taking MCTs (mean daily intake 0.73 mL/kg body weight), all with focal unaware seizures, had >50% reduction in seizure frequency

Further trials are suggested to focus on long‐term safety, tolerability, and body weight control and improved treatment formulations

2. INTRODUCTION

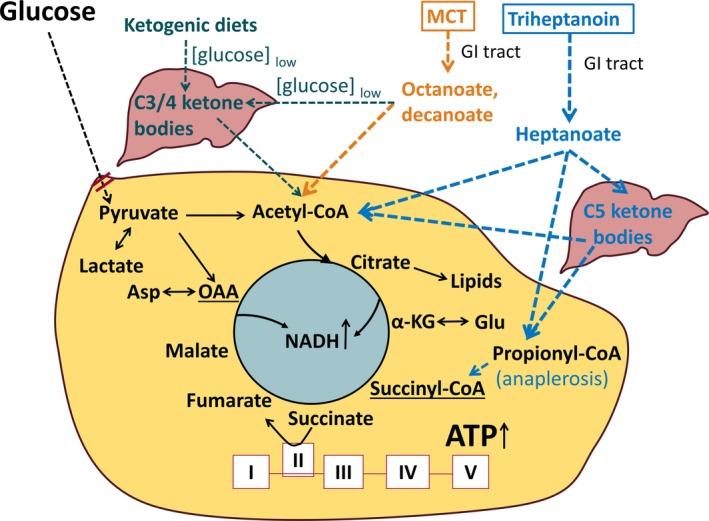

Epilepsy is characterized by heightened excitability of the brain. In addition, glucose metabolism has been shown to be reduced in epileptogenic areas in people with epilepsy and in animal models.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 This may result in local shortages of carbon and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which likely contributes to seizure generation. Glucose‐derived carbons are metabolized to amino acids, lipids, and energy, which are all vital for regulated neuronal signaling. Therefore, alternative sources of carbons for the brain, such as medium chain fatty acids or ketone bodies, are needed to address reduced glucose metabolism (reviewed by Ref. 6, 7; Figure 1). Moreover, decreases in brain levels of glutamate, glutamine, and malate have been found in people with epilepsy and in rodent chronic epilepsy models, indicating that the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is deficient of intermediates containing 4 or 5 carbons.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 This decreases the capacity for TCA cycle flux and subsequent ATP, amino acid, and lipid production. Thus, refilling of the pools of C5 and C4 TCA cycle metabolites (anaplerosis) is also needed.6, 12

Figure 1.

Schematic of the proposed biochemical effects of medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) and triheptanoin in epilepsy. Glucose is typically the main fuel for brain cells and is oxidized by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle producing most of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during aerobic metabolism, and lipids and amino acids, such as aspartate and glutamate. The red double lines indicate that in many epilepsy types there is evidence for impaired glucose metabolism, which is likely to result in local shortages of ATP as well as carbons to produce lipids and amino acids. This may contribute dysregulation of neuronal signaling and subsequent seizure generation. Alternative sources of carbons for the brain can be provided by C3/4 ketone bodies, which are produced when carbohydrates and calories are restricted. Another carbon source are medium chain fatty acids, such as octanoate and decanoate as well as heptanoate. Octanoate and decanoate can be provided via MCTs and heptanoate from triheptanoin, and all can directly produce acetyl‐CoA (coenzyme A). In addition, heptanoate can be metabolized by the liver to C5 ketones. Both heptanoate and C5 ketones are also metabolized to propionyl‐CoA which after carboxylation refills the C4 intermediate pool of the TCA cycle as succinyl‐CoA (anaplerosis). This is important to compensate for the loss of carbons from the TCA cycle for production of lipids and amino acids and to continue efficient TCA cycling

Few approaches can address these impairments in energy metabolism. Ketone bodies are able to supply the majority of fuel to the human brain during low‐carbohydrate, high‐fat ketogenic diets.13 These diets can be very effective, specifically for certain childhood epilepsies14, 15 and also for some adults with refractory epilepsy (reviewed in Ref. 16 but see Ref. 17). In addition, the diets and ketones have a variety of additional beneficial mechanisms, including antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities.7, 18 Ketogenic diets are not straightforward, especially not for adults, with the main problems being compliance and body weight loss, which cannot be sustained long term.16, 19

Here, we investigated for the first time the safety and tolerability of medium chain triglycerides (MCTs, which contain triglycerides with octanoate and decanoate) and triheptanoin (triglyceride of heptanoate) as add‐on treatments, because they target the metabolic deficiencies in epilepsy described. MCTs and triheptanoin are metabolized to their respective medium chain fatty acids in the gastrointestinal tract; these are able to diffuse into tissues, and eventually mitochondria, mostly without the help of identified transport proteins20 (Figure 1). In addition, the liver can produce ketone bodies, such as β‐hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and acetone, specifically when blood glucose levels are low, and the C5 ketone bodies β‐ketopentanoate and β‐hydroxypentanoate from heptanoate. All medium chain fatty acids eventually provide acetyl–coenzyme A (CoA), providing energy and carbon. In addition, triheptanoin, heptanoate, and C5 ketone bodies provide anaplerotic propionyl‐CoA, which can further improve amino acid and energy production in vivo and in vitro.6, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Thirty‐five percent of energy intake triheptanoin and MCTs have shown anticonvulsant, beneficial metabolic and antioxidant effects in several epilepsy models.10, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Triheptanoin has been used in various metabolic disorders at the same or similar doses31, 32 in glucose transporter 1 deficiency33, 34, 35 and in children with epilepsy.36 MCTs have been used for a long time to treat long‐chain fatty acid oxidation disorders and in the context of ketogenic diets.30, 37 When glucose is low, MCTs are highly ketogenic and can help to provide seizure control.37, 38, 39 Without restrictions in carbohydrates, ketone levels remain low.25 Both octanoate and decanoate are fuels for cultured brain‐derived cells,25, 40 whereas octanoate has been shown to enter the brain and to be used as a fuel in the brain, largely by astrocytes.41, 42

Here we tested to see if adding triheptanoin or MCTs to a regular diet is feasible, safe, and tolerated in adults with medically refractory epilepsy. Patients were advised to mix the treatments with food and to reduce energy intake of regular foods (but no specific types of macronutrients) to avoid gastrointestinal problems and excess energy intake.

3. METHODS

3.1. Classification of evidence

We sought to investigate whether MCTs or triheptanoin are safe and tolerated as an add‐on therapies in people with drug‐resistant epilepsy. The evidence generated from this trial is classified as class II, because of the relatively small subject numbers.

3.2. Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research and Ethics Committees of Melbourne Health and the University of Queensland. Written informed consent was provided by all participants or their legal guardians, prior to any study procedures being undertaken. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (registry no: ACTRN12612000226808). The trial protocol can be found in the supplementary files.

3.3. Organization of study

The study was a single‐center, double‐blind, comparative randomized controlled trial. The study was conducted from 2014 to 2016 at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and was monitored for safety, data collection, and integrity by an independent clinical research organization (CRO), Neuroscience Trials Australia Inc. The CRO used computer‐generated random numbers to randomize the 2 treatments (labeled with participant numbers and recording glass container numbers), which were then given to the hospital's pharmacy to supply the investigational treatments to the participants. Everyone else involved in the trial was blinded until after the statistical analysis.

3.4. Participants

Male or female subjects (≥12‐years‐old) with epilepsy who experienced at least 2 seizures of an eligible type per 28 days over 2 months before enrollment despite treatment with at least one antiseizure drug at clinically appropriate doses were eligible. Eligible seizure types included focal unaware, focal to bilateral tonic seizures, focal aware motor, generalized tonic, tonic, and atonic seizures.43 Exclusion criteria were eating and psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, currently on ketogenic diet, nonepileptic seizures, changes of antiseizure medication 1 month before trial, pregnancy, and breastfeeding.

After enrollment by a nurse, participants underwent an 8‐week baseline period during which they completed a prospective seizure diary. People who had experienced an average of 2 seizures per month (excluding seizures without motor features) during the 8‐week baseline period and were screened negative for disorders affecting medium and short chain fatty acid oxidation were randomized to treatment.

3.5. Study intervention

Participants were randomized 1:1 by the CRO using computer‐generated random numbers to receive either add‐on MCTs containing the triglycerides of octanoate (55%) and decanoate (45%, Stepan Lipid Nutrition, IL) or triheptanoin (>98.9%, Stepan Lipid Nutrition), both in oil form. The treatments were indistinguishable, as they were both clear and tasteless. After dietitian counseling, patients were given a titration scheme to increase their treatment dose over a period of 3 weeks to 35% of energy intake (based on 4‐day food diaries) or maximum 100 mL, or in the case of gastrointestinal disturbances, to their maximal tolerated daily dose. Participants reported all treatment doses taken in their treatment diaries and brought remaining treatments and empty containers back to the clinic for checking by the trial research coordinators, as is standard practice for clinical trials. The treatment period consisted of the on‐titration phase and 12‐week maintenance phase. Then, participants titrated off their treatments for 3 weeks and remained off the treatment for 4 weeks, until the last visit.

3.6. Outcome measures

The study's primary prespecified endpoints were the following: (a) safety, measured as the number of and proportion of patients with adverse events that are possibly, probably, or definitely causally related to study intervention over the 18‐week treatment period; and (b) adherence, measured as percentage of the prescribed treatment dose reported to be taken over the 12‐week maintenance phase.

Secondary prespecified endpoints for the study included (a) seizure frequency over the 12‐week full‐dose treatment period as compared to the baseline period, and (b) responder rate measured as the proportion of patients who show ≥50% improvement in seizure frequency over the 12‐week full‐dose treatment period as compared to during the baseline period.

3.7. Study procedures

After signing the informed consent, participants had a baseline medical history taken, a physical examination, and an evaluation of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Blood and urine samples were obtained. Blood was analyzed for serum chemistry, cell counts, lipid profiles, and when applicable, the levels of valproate, carbamazepine, and phenytoin were monitored by the hospital's central laboratory. These evaluations were repeated at all hospital visits before and after treatment and every 4 weeks during treatment (Figure 2A). To exclude metabolic abnormalities, blood spots and urine were analyzed by mass spectroscopy at the first visit and throughout the study for blood acylcarnitines and urine organic acids. Participants were instructed on the keeping of daily seizure diaries and 4‐day food diaries and were not allowed to change their antiseizure medications during the study period. At all visits, a dietitian counseled patients individually on healthy eating. Based on food diaries from the participants at visits 2, 3, and 6, the dietitian provided treatment plans with the doses of treatment to be taken during 3 daily meals. She advised participants to mix the treatments with foods, suggested suitable food options, and assisted participants in finding their maximal tolerated doses. In addition, she provided advice on how to optimize the remaining diet for adequate nutrition and minimization of gastrointestinal side effects or body weight changes. Energy intake was calculated from food diaries provided using Foodworks 7 (Xyris Software, Queensland, Australia). Before the treatment and after the maintenance phase, on visits 2 and 6, participants filled out questionnaires, including the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory‐89 (QOLIE‐89)44, 45 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),45 as well as the Liverpool Adverse Events Profile (LAEP).46 Adverse events were noted throughout the study and assessed regarding causality to treatment. All severe adverse events (SAEs) were reviewed by the study CRO. Both the site investigator and the sponsor of the study (University of Queensland) assessed the potential relationship between SAEs and study drug but remained blinded to treatment assignment.

Figure 2.

Diagrams specifying the trial design (A) and flow diagram indicating the number of people with refractory epilepsy from screening to study completion (B). A, Clinic visits are indicated as triangles on the weekly time line. After an 8‐week baseline period, the on‐titration period for MCTs or triheptanoin add‐on treatment was 3 weeks until maximal tolerated dose was reached and was maintained for the 12‐week maintenance phase. Thereafter, add‐on treatment was titrated off for 3 weeks and followed by a 4‐week period without add‐on treatment. B, The diagram shows the number of participants analyzed for primary and secondary outcomes and reasons for withdrawal from the study. MCT, medium chain triglyceride

3.8. Sample size and statistical analysis

The original study design planned to enroll and randomize 60 people with treatment‐resistant epilepsy (≥12‐years‐old) to MCTs vs triheptanoin, 30 in each treatment arm from 4 Melbourne hospitals (based on assuming Poisson distribution for adverse events and using Monte Carlo simulation by a commercial statistician). Due to funding shortage, patients were only recruited at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and the study ended early with 34 randomized participants (Figure 2B). Safety was assessed among all randomized participants. Adherence and secondary endpoints were assessed in the participants with epilepsy who completed the full treatment period (Figure 2B). To compare for differences in proportions regarding the number of patients completing the trial or showing changes in seizure frequency we used Fisher exact tests. To compare time until dropout we used a log rank test. All other statistical comparisons were performed using Mann‐Whitney tests. We used GraphPad Prism, version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, CA) and IBM SPSS Statistics (Java Console, version 25, Armonk, NY) for analysis, with P < 0.05 regarded as significant.

3.9. Data availability policy

The lead author has access to all data, which will be made available on request. The study protocol can be found in the supplementary files.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Patient cohort, maximal tolerated dose, and compliance

Figure 2B shows the participant flow. Seventeen people with epilepsy were randomized to each of the 2 treatments. One individual in the triheptanoin group was later diagnosed to have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and was excluded from analysis. The characteristics of the participant population included, randomized, and analyzed are shown in Table 1. The groups were similar in most characteristics, except that there were fewer people with focal unaware seizures in the triheptanoin than in the MCT treatment arm (P = 0.04).

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics

| MCT (n = 17) | Triheptanoin (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 38.7 (13.5) | 39.1 (10.4) |

| Gender | ||

| Female, n (%) | 8 (47%) | 8 (50%) |

| Male, n (%) | 9 (53%) | 8 (50%) |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 78.7 (15.3) | 82.9 (24.5) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 27.6 (5.3) | 28.7 (6.6) |

| Baseline energy intake (kcal), mean (SD) | 1908 (698) | 1695 (528) |

| Epilepsy etiology, n (%) | ||

| Temporal | 11 (65%) | 7 (44%) |

| Extra temporal or unknown | 7 (41%) | 9 (56%) |

| Seizure types, n (%) | ||

| Focal unaware | 16 (94%) | 10 (62.5%)* |

| Focal to bilateral tonic clonic | 10 (59%) | 4 (25%) |

| Focal aware motor | 4 (23.5%) | 7 (44%) |

| Generalized tonic‐clonic | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (6%) |

| Prior neurologic surgery, n (%) | ||

| None | 11 (64.7%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| 1 | 4 (23.5%) | 3 (18.8%) |

| 2 | 1 (5.9%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| 6 | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Number of concomitant AEDs, n (%) | ||

| 2 | 3 (17.7%) | 3 (18.8%) |

| 3 | 7 (41.2%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| 4 | 7 (41.2%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| 6 | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Seizures per 28 d, median (IQR) | 12.4 (3.92, 44.4) | 5 (3.6, 17.6) |

MCT, medium chain triglycerides; SD, standard deviation; AED, antiepileptic drug; IQR, interquartile range.

The characteristics of the 2 groups were compared using Fisher exact tests regarding seizure types and using a Mann‐Whitney test regarding seizure frequency.

P = 0.039.

There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in the proportion of participants completing the study (65% and 56%, respectively, P = 0.73, Table 2) and the time until drop out (P = 0.70, Figure S1A). The reasons for withdrawal were nonserious adverse events: gastrointestinal effects in 4 vs 5 participants in the MCT vs triheptanoin treatment group, increases in seizure activities in 2 people in each group, withdrawn consent by 2 participants in the MCT group, and increased aggression in one person in the triheptanoin group. Adherence to treatment was measured by the doses taken as reported by participants in treatment diaries relative to the dose prescribed and was similar for both treatment groups (P = 0.33), as was the volume of treatment (P = 0.59) and dose relative to body weight (P = 0.13, Table 2). The maximum tolerated dose varied largely between participants from 30‐88 mL of MCTs per day (median 59 mL, 0.83 mL MCT/kg body weight) and 20‐85 mL triheptanoin (median 55 mL, 0.59 mL/kg, Table 2).

Table 2.

General treatment effects

| MCT | Triheptanoin | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients completing trial | 11/17 (64.7%) | 9/16 (56.3%) | 0.73 |

| Proportion of patients with adverse events | 11/17 (64.7%) | 14/16 (87.5%) | 0.22 |

| Total number of adverse events* (number of subjects) | 37 (n = 17) | 38 (n = 16) | |

| Patients who completed trial | n = 11 | n = 9 | |

| Treatment doses taken during treatment period (v3‐v6; median, IQR) | |||

| % of prescribed dose | 99.4 (96, 100) | 97.6 (76, 99.8) | 0.33 |

| Volume of treatment/day (mL) | 59 (50, 74) | 55 (39, 69) | 0.4 |

| Treatment dose/body weight (mL/kg) | 0.83 (0.62, 0.99) | 0.59 (0.46, 0.78) | 0.09 |

| Changes in body weight from v2 to v6 (kg) | 2.25 (0.38, 3.55) | 2.00 (−0.08, 3.8) | 0.83 |

| LAEP scores before treatment on v2 | 45 (38, 52) | 47 (38.5, 55.5) | |

| LAEP score after treatment on v6 | 45 (36, 78) | 55 (43, 60) | |

| P‐value (change in LAEP score) | 0.57 | 0.08 | |

| Percentage (median, IQR) of baseline seizures during treatment period (95% CIs) |

54 (40, 102) (36, 109) |

102 (75, 165) (71, 157) |

0.13 |

| Number of people with >50% seizure reduction | 5 (45%) | 1 (11%) | 0.16 |

MCT, medium chain triglyceride; LAEP, Liverpool Adverse Events Profile; IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval.

A Fisher exact was used to compare proportions, all other comparisons between the 2 treatments were evaluated using Mann‐Whitney tests. *Please see Table 3 for adverse events.

4.2. Adverse events and body weight changes during treatment

All blood tests, including lipid profiles, showed no clinically significant changes. The proportion of people with adverse events was similar among the 2 treatment groups (P = 0.22, Table 2). This includes 2 people in each group with SAEs, namely, increases in seizure activity that resulted in hospitalization. In addition, the total number of adverse events in all participants who were being treated was similar with MCTs and triheptanoin (37 and 38 events, respectively, Table 2). The adverse effects that were determined possibly, probably, or definitely to be causally related are listed in Table 3 together with the number of patients affected. The types of adverse events were similar with both treatments and most common effects were diarrhea, stomach cramps, or abdominal pain, which resolved. The intensity of the side effects was largely mild and was similar among treatments.

Table 3.

Number of patients with adverse events considered related to treatment

| MCT (n = 17 patients) | Triheptanoin (n = 16 patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | 5 (29%) | 8 (50%) |

| Stomach cramps, abdominal pain | 4 (24%) | 1 (6%) |

| Constipation | 2 (12%) | 1 (6%) |

| Bloating, flatulence | 0 | 2 (13%) |

| Headache | 2 (12%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Oily forehead & acne on waist/legs | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Disturbed sleep pattern | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| Lethargy | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| Overheated/pale/tired | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| Increased aggression | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Sum | 17 | 18 |

MCT, medium chain triglyceride.

Adverse events considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment are included. The intensity of the side effects was similar among treatments and was largely mild.

Adverse events deemed not causally related to MCT treatment were gastritis, shingles, sinus infection, calf hardness, bladder infection and viral illness (fatigue), a fall with head strike, and increased seizure activity. With triheptanoin, participants showed joint pain with viral illness, lateral epicondylitis, impacted wisdom teeth, fractured right clavicle with scraped right knee and knuckles, back pain, increased seizure activity, and in one participant flu, renal cyst, and left upper quadrant pain.

Seven and 6 people were overweight or obese at baseline and were then randomized to MCTs and triheptanoin treatments groups, respectively. No differences were observed between the 2 treatments regarding the changes in body weights (Table 2, P = 0.83; Figure S1B). A median weight gain of 2‐2.25 kg during the treatment phase of 12 weeks was observed in both groups (Figure S1B). In 2 people taking MCTs and one person taking triheptanoin, body weight increased by >5%, but body mass index (BMI) remained normal. At visit 7, 4 weeks after off titration, only one person treated with triheptanoin showed >5% increase in body weight relative to baseline while keeping a normal BMI. Changes in body weight gain did not correlate with the treatment dose taken during the treatment Phase (P = 0.72 and P = 0.59), and they did not match with reported changes in energy intake or age.

Liverpool Adverse Events Profile (LAEP) scores before and at the end of treatment remained largely similar (P = 0.57 and P = 0.08, Table 2). With MCT treatment, several people reported within the LAEP on visit 4 decreased tiredness (5 participants), less hair loss (5), better concentration (4), and increased weight gain (6). With triheptanoin treatment, participants noted in the LAEP that they felt more tired (4 patients), had more hair loss (4), skin rash (5), worsened vision (4), diarrhea (4), weight gain (4), and gum problems (3). Only one of the persons reporting gum problems was taking phenytoin.

4.3. Seizures

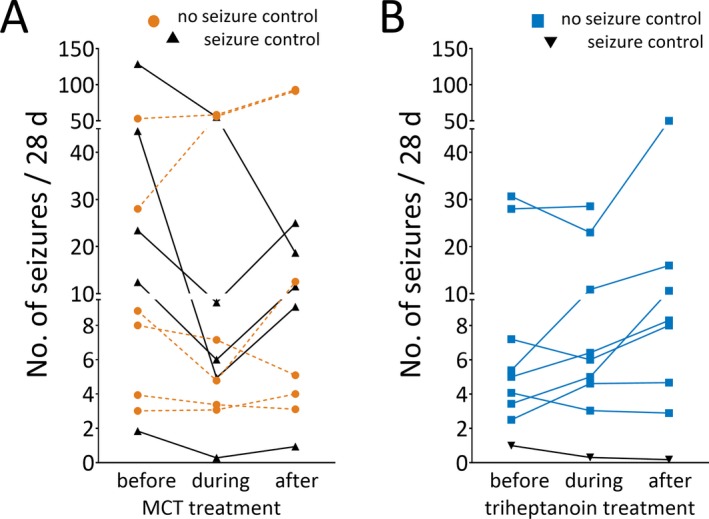

The study was terminated early and therefore not designed to find differences between antiseizure effects of the 2 treatments, hence only descriptive analysis was performed.

There were no differences regarding the changes in seizure frequency between the 2 treatment arms (Table 2, P = 0.13). The group taking MCTs had a median of 54% baseline seizure frequency (40%, 102% interquartile range [IQR]), whereas the triheptanoin‐treated group showed no change with a median of 102% of baseline seizure frequency (75%, 165% IQR, Table 2). Two participants experienced doubling of their seizures, namely, a participant with epilepsy following viral encephalitis taking MCTs and a person with ventricular heterotopia in the triheptanoin treatment arm (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A, B Seizure frequencies (number of seizures/28 d) during baseline, full‐dose treatment, and posttreatment phases are shown for people taking MCTs (A) vs triheptanoin (B). The black triangles indicate seizure frequencies from participants with treatment efficacy, as defined by >50% of reduction in seizure frequencies during the treatment phase. MCT, medium chain triglyceride

With MCT treatment, 5 of 11 treated participants (45%) while taking on average 0.73 mL/kg (0.64 mL/kg median) showed >50% reduction in seizure frequency, specifically focal unaware seizures. During treatment with 0.63 mL/kg MCT another person showed 46% reduction in seizure frequency (Figure 3A). Of 6 persons with >40% decrease in seizure numbers during MCT treatment, 5 showed increases in seizures after the treatments were tapered off (Figure 3A). In the triheptanoin group, only 1 of 9 participants showed >50% fewer seizures while being treated with 0.59 mL/kg (Figure 3B).

Specifically, the numbers of focal unaware seizures were reduced in people treated with MCTs or triheptanoin.

4.4. Dose vs antiseizure effects

In the people with seizure control, the effective triheptanoin dose was 55 mL (0.59 mL/kg) and the MCT dose varied between 47 and 65 mL per day over the treatment phase (0.56‐0.99 mL/kg range, 0.51‐0.95 mL/kg CI, average 27% of energy intake, Figure S1C,D). There were no correlations of seizure control with the dose taken (Figure S1C) or relative energy intake of treatment (data not shown).

The changes in the QOLIE‐89 scores after treatment relative to those at baseline visit were similar between treatments (P = 0.6, Mann‐Whitney test, n = 9‐10). Too few participants completed the HADS.

4.5. Changes in macronutrient intake

Macronutrient distributions are shown in Figure S1D. During baseline, people claimed to consume on average 34% of daily calories as fat, 45% carbohydrates, and 21% protein (n = 21). The people who showed seizure reductions reported on average 27% energy intake from MCT treatment (n = 5 total, between 19% and 42% MCT). The other macronutrients consisted of 25% fat, 31% carbohydrates, and 17% protein (n = 5).

5. DISCUSSION

The present study represents one of the few randomized controlled trials of metabolic treatments in adults with medically refractory epilepsy. The main findings of this study were the following. (a) A total of 56%‐65% adults were able to tolerate an addition of MCTs (median 59 mL) or triheptanoin (median 55 mL) to their food throughout the day for the 3‐month duration of the treatment period. There were rare central nervous system (CNS) side effects and no SAEs that were thought to be causally related to the treatment. The main side effects were diarrhea and abdominal pain. Body weight changes were not of clinical significance. (b) Although the study was not powered to determine efficacy, 5 of 11 participants (45%) showed >50% reductions in seizure frequency during MCT treatment. Only 1 participant of 10 showed fewer seizures while treated with triheptanoin. All of these participants showing reduction in seizure frequency had focal unaware seizures. In each treatment arm one person showed doubling of seizures.

5.1. Feasibility

The study showed that adults with epilepsy tolerate add‐on MCTs or triheptanoin with relatively minor gastrointestinal effects and that these metabolic treatments can be followed. This is very important, as it opens up new possible treatment options for this population. So far, ketogenic diets as well as modified Atkins diets and the Low Glycemic Index diet have been the only accepted metabolic treatment options for epilepsy. These treatments have been shown to be effective in children and there are very few studies in adults.16 In general, adults have difficulties adhering to the very strict versions of the diet and it can be unsustainable long term.16 The current diets used for epilepsy treatment are restrictive regarding the amounts of carbohydrates or the nature of the carbohydrates and can have higher costs. In contrast, add‐on MCT or triheptanoin treatment allows the patient to choose more freely what to eat, which is more similar to a drug than a dietary treatment.

5.2. Adverse events, side effects, and management thereof

The adverse events reported were largely as expected from other trials of triheptanoin or knowledge about the physiologic effects of pure triglycerides of medium chain fats.31, 47 The gastrointestinal effects could be limited by slowly introducing patients to the treatments and emulsifying the pure treatments with foods. Reducing portion sizes during meals and long chain fats may also improve tolerance of the treatment.

Unfortunately, 2 of the participants showed doubling in seizure frequencies and 2 others were hospitalized because of severe seizures. These events were carefully investigated and it was decided that causality is not possible to determine. Although it is possible that this could represent seizure aggravation, the study population was a group of patients with severe drug‐resistant epilepsy with frequent seizures. It can be expected that some of these patients may have an increase in their seizure frequency through the natural fluctuations that occur—including some that would require hospital admissions. It is very important to further collect data on such events in future potential trials and the community. Doctors need to get informed regarding use of MCTs and “ketogenic” diets, which are becoming very popular. MCTs in various forms are increasingly available in pure forms from health food stores and are hidden in many food products marketed for sports, weight loss, and well‐being.

We were aware that body weight gain would most likely be an issue, which we tried to avoid with mandatory dietitian counseling. The fact that the majority of patients, who were already overweight or obese, had gained >2 kg weight during 12 weeks is of concern. Strategies to avoid weight gain need to be developed if these treatments are to have widespread use in clinical practice. On the other hand, weight gain in newly treated patients is a side effect of several commonly used drugs, such as valproate.

5.3. Limitations, generalizability, interpretation of anti‐seizure effects, and future directions

The data regarding effects on seizures of the dietary supplements are preliminary and we did not target a specific type of seizure or epilepsy. The seizure frequency reductions in 5 of 11 participants treated with MCTs was encouraging, and, if confirmed, is comparable to other types of diets. Several studies with ketogenic diet or modified Atkin's diets have found similar antiseizure effects in children14, 15 and often adults16 (although not consistently17).

Our study indicates that specifically focal unaware seizures were responsive to MCT treatment.

Please note that in the triheptanoin treatment arm there were significantly fewer participants with focal unaware seizures (P = 0.039), which may be a potential reason for lack of efficacy in this study. An earlier open‐label study using pharmaceutical grade triheptanoin showed effects against various seizure types in 5 of 8 children who tolerated the add‐on treatment.36

Larger placebo‐controlled studies are necessary to confirm these antiseizure effects in adults and children and we propose to first focus on adults with focal unaware seizures. One main methodologic difficulty is the limited choices for placebos. Most natural fats contain polyunsaturated fats, which may have antiseizure effects. Therefore, triglycerides with pure defined saturated long chain fatty acids would be needed. On the other hand, any addition of extra calories will change macronutrient composition and can therefore affect the metabolism of the body and brain. For example, addition of fats is likely to slow the uptake of carbohydrates and insulin release. Another desirable way forward would be to use powders of MCTs or triheptanoin with largely calorie‐free carriers, such as fiber or silica. The pure carriers may be used as placebo in future trials.

5.4. Comparison to ketogenic diet

Our results from this small trial are similar to those found by a recent meta‐analysis of ketogenic and modified Atkins diets in adults with epilepsy in terms of completion rates. The meta‐analysis critically evaluated 16 prospective open‐label studies with a total of 338 patients showing 62% completion on average in all studies, whereas 56% of 76 patients completed the 5 pure ketogenic diet studies. An average of 53% of people completing the ketogenic and Atkins diet studies showed >50% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.42‐0.63) and 13% (95% CI 0.01‐0.25) >>90% reduction in seizure frequencies.16 Thus, in our small blinded study, the efficacy of the MCT treatment regarding >50% of seizure reduction (45%) is within the CIs of the ketogenic and Atkins diets’ effects. The adverse effects of MCTs were mostly different from those found in the ketogenic and modified Atkins diet studies, in which many adults experienced, often intended, weight loss and dyslipidemia.16 Please note that the MCT treatment here is not considered ketogenic, as we did not find any elevations of ketone levels in serum samples (data not shown). The (ketogenic) MCT treatment developed by the John Radcliffe hospital required 30% of MCTs and 30% long chain fats.39

6. CONCLUSION

This is the first randomized controlled trial of add‐on MCTs vs triheptanoin treatment for drug‐resistant epilepsy in adults. The results show that both treatments are tolerated in this population. Gastrointestinal adverse effects were the most common treatment‐related events observed and could be mitigated by adding MCTs or triheptanoin to food. Larger double‐blind placebo‐controlled studies in adults and children are necessary to assess if seizures can be reduced with MCTs or triheptanoin.

DISCLOSURE AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The study was supported by the Epilepsy Foundation New Therapy Development Program, Parents Against Childhood Epilepsy and Uniquest Pty. Ltd. Dr. Borges filed for a patent regarding triheptanoin in epilepsy and received a license fee payment and research support from Ultragenyx Pharmaceuticals Inc. Research support was also received from Epilepsy Foundation New Therapy Development Program, Parents Against Childhood Epilepsy, Uniquest Pty. Ltd., National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Motor Neurone Disease Research Institute Australia, and funding from the Brain Foundation (Australia). Dr. Terence J O'Brien reports grants and personal fees from UCB Pharma, Eisai, and Zynerba Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. He has also received research grants from the NHMRC, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and the RMH Neuroscience Foundation. Dr. Kwan/his institution received speaker or consultancy fees and/or research grants from Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. He is supported by the Medical Research Future Fund Practitioner Fellowship. He has received research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Research Council, the US National Institutes of Health, Hong Kong Research Grants Council, Innovation and Technology Fund, Health and Health Services Research Fund, and Health and Medical Research Fund. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all participants and caregivers who participated in the study as well as to the referring doctors. We thank Stepan Lipid Nutrition for donating MCTs and manufacturing triheptanoin. We are grateful to Katherine Bartlett, James Pitt, Chris French, Mark Cook, Lucy Vivash, Darren Germaine, Leonid Churilov, Fiona Ellery, and Tina Soulis for support.

Borges K, Kaul N, Germaine J, Kwan P, O'Brien TJ. Randomized trial of add‐on triheptanoin vs medium chain triglycerides in adults with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. 2019;4:153–163. 10.1002/epi4.12308

REFERENCES

- 1. Kuhl DE, Engel J Jr, Phelps ME, et al. Epileptic patterns of local cerebral metabolism and perfusion in humans determined by emission computed tomography of 18FDG and 13NH3. Ann Neurol. 1980;8:348–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan JW, Williamson A, Cavus I, et al. Neurometabolism in human epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(suppl 3):31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dube C, Boyet S, Marescaux C, et al. Relationship between neuronal loss and interictal glucose metabolism during the chronic phase of the lithium‐pilocarpine model of epilepsy in the immature and adult rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:227–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarikaya I. PET studies in epilepsy. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;5:416–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDonald TS, Carrasco‐Pozo C, Hodson MP, et al. Alterations in cytosolic and mitochondrial [U‐(13)C]glucose metabolism in a chronic epilepsy mouse model. eNeuro. 2017;4:e0341‐16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald T, Puchowicz M, Borges K. Impairments in oxidative glucose metabolism in epilepsy and metabolic treatments thereof. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masino SA, Rho JM. Mechanisms of ketogenic diet action In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, et al., editors. Jasper's basic mechanisms of the epilepsies. 4th ed Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Melo TM, Nehlig A, Sonnewald U. Metabolism is normal in astrocytes in chronically epileptic rats: a (13)C NMR study of neuronal‐glial interactions in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alvestad S, Hammer J, Eyjolfsson E, et al. Limbic structures show altered glial‐neuronal metabolism in the chronic phase of kainate induced epilepsy. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Willis S, Stoll J, Sweetman L, et al. Anticonvulsant effects of a triheptanoin diet in two mouse chronic seizure models. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:565–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bartnik‐Olson BL, Ding D, Howe J, et al. Glutamate metabolism in temporal lobe epilepsy as revealed by dynamic proton MRS following the infusion of [U(13)‐C] glucose. Epilepsy Res. 2017;136:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borges K, Sonnewald U. Triheptanoin – a medium chain triglyceride with odd chain fatty acids: a new anaplerotic anticonvulsant treatment? Epilepsy Res. 2012;100:239–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Courchesne‐Loyer A, Croteau E, Castellano CA, et al. Inverse relationship between brain glucose and ketone metabolism in adults during short‐term moderate dietary ketosis: a dual tracer quantitative positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, et al. The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin K, Jackson CF, Levy RG, et al. Ketogenic diet and other dietary treatments for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD001903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu H, Yang Y, Wang Y, et al. Ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy in adults: a meta‐analysis of observational studies. Epilepsia Open. 2018;3:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kverneland M, Molteberg E, Iversen PO, et al. Effect of modified Atkins diet in adults with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy: a randomized clinical trial. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Masino SA, Rho JM. Metabolism and epilepsy: ketogenic diets as a homeostatic link. Brain Res. 2019;1703:26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klein P, Tyrlikova I, Mathews GC. Dietary treatment in adults with refractory epilepsy: a review. Neurology. 2014;83:1978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bach AC, Babayan VK. Medium‐chain triglycerides: an update. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:950–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu L, Zhang GF, Kombu RS, et al. Parenteral and enteral metabolism of anaplerotic triheptanoin in normal rats. II. Effects on lipolysis, glucose production, and liver acyl‐CoA profile. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E362–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hadera MG, Smeland OB, McDonald TS, et al. Triheptanoin partially restores levels of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates in the mouse pilocarpine model of epilepsy. J Neurochem. 2014;129:107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marin‐Valencia I, Good LB, Ma Q, et al. Heptanoate as a neural fuel: energetic and neurotransmitter precursors in normal and glucose transporter I‐deficient (G1D) brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brunengraber H, Roe CR. Anaplerotic molecules: current and future. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:327–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tan KN, Carrasco‐Pozo C, McDonald TS, et al. Tridecanoin is anticonvulsant, antioxidant, and improves mitochondrial function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2035–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan KN, Simmons D, Carrasco‐Pozo C, et al. Triheptanoin protects against status epilepticus‐induced hippocampal mitochondrial dysfunctions, oxidative stress and neuronal degeneration. J Neurochem. 2018;144:431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDonald T, Hodson MP, Bederman I, et al. Triheptanoin increases TCA cycling by improving [U‐13C6]‐glucose incorporation into glycolytic intermediates glucose and increasing activities of pyruvate dehydrogenase and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase in a chronic epilepsy mouse model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim TH, Borges K, Petrou S, et al. Triheptanoin reduces seizure susceptibility in a syndrome‐specific mouse model of generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2013;103:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McDonald TS, Tan KN, Hodson MP, et al. Alterations of hippocampal glucose metabolism by even versus uneven medium chain triglycerides. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Augustin K, Khabbush A, Williams S, et al. Mechanisms of action for the medium‐chain triglyceride ketogenic diet in neurological and metabolic disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gillingham MB, Heitner SB, Martin J, et al. Triheptanoin versus trioctanoin for long‐chain fatty acid oxidation disorders: a double blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40:831–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roe CR, Brunengraber H. Anaplerotic treatment of long‐chain fat oxidation disorders with triheptanoin: review of 15 years Experience. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mochel F, Hainque E, Gras D, et al. Triheptanoin dramatically reduces paroxysmal motor disorder in patients with GLUT1 deficiency. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:550–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borges K. Triheptanoin in epilepsy and beyond In: Masino SA, editor. Ketogenic diet and metabolic therapies: expanded roles in health and disease. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pascual JM, Liu P, Mao D, et al. Triheptanoin for glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D): modulation of human ictogenesis, cerebral metabolic rate, and cognitive indices by a food supplement. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1255–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Calvert S, Barwick K, Par M, et al. A pilot study of add‐on oral triheptanoin treatment for children with medically refractory epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22:1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huttenlocher PR, Wilbourn AJ, Signore JM. Medium‐chain triglycerides as a therapy for intractable childhood epilepsy. Neurology. 1971;21:1097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, et al. A randomized trial of classical and medium‐chain triglyceride ketogenic diets in the treatment of childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwartz RH, Eaton J, Bower BD, et al. Ketogenic diets in the treatment of epilepsy: short‐term clinical effects. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1989;31:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khabbush A, Orford M, Tsai YC, et al. Neuronal decanoic acid oxidation is markedly lower than that of octanoic acid: a mechanistic insight into the medium‐chain triglyceride ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuge Y, Yajima K, Kawashima H, et al. Brain uptake and metabolism of [1‐11C]octanoate in rats: pharmacokinetic basis for its application as a radiopharmaceutical for studying brain fatty acid metabolism. Ann Nucl Med. 1995;9:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ebert D, Haller RG, Walton ME. Energy contribution of octanoate to intact rat brain metabolism measured by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fisher RS, Cross JH, D'Souza C, et al. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types. Epilepsia. 2017;58:531–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson EK, Jones JE, Seidenberg M, et al. The relative impact of anxiety, depression, and clinical seizure features on health‐related quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abetz L, Jacoby A, Baker GA, et al. Patient‐based assessments of quality of life in newly diagnosed epilepsy patients: validation of the NEWQOL. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vockley J. Results from a 78‐week, single‐arm, open‐label Phase 2 study to evaluate UX007 in pediatric and adult patients with severe long‐chain fatty acid oxidation disorders (LC‐FAOD). J Inher Metabol Dis. 2018. 10.1007/s10545-018-0217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The lead author has access to all data, which will be made available on request. The study protocol can be found in the supplementary files.