Abstract

Objective

This study used a nationally representative sample from Tanzania as an example of low-resource setting with a high burden of maternal and newborn deaths, to assess the availability and readiness of health facilities to provide basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) and its associated factors.

Design

Health facility-based cross-sectional survey.

Setting

We analysed data for obstetric and newborn care services obtained from the 2014–2015 Tanzania Service Provision Assessment survey, using WHO-Service Availability and Readiness Assessment tool.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Availability of seven signal functions was measured based on the provision of ‘parental administration of antibiotic’, ‘parental administration of oxytocic’, ‘parental administration of anticonvulsants’, ‘assisted vaginal delivery’, ‘manual removal of placenta’, ‘manual removal of retained products of conception’ and ‘neonatal resuscitation’. Readiness was a composite variable measured based on the availability of supportive items categorised into three domains: staff training, diagnostic equipment and basic medicines.

Results

Out of 1188 facilities, 905 (76.2%) were reported to provide obstetric and newborn care services and therefore were included in the analysis of the current study. Overall availability of seven signal functions and average readiness score were consistently higher among hospitals than health centres and dispensaries (p<0.001). Furthermore, the type of facility, performing quality assurance, regular reviewing of maternal and newborn deaths, reviewing clients’ opinion and number of delivery beds per facility were significantly associated with readiness to provide BEmONC.

Conclusion

The study findings show disparities in the availability and readiness to provide BEmONC among health facilities in Tanzania. The Tanzanian Ministry of Health should emphasise quality assurance efforts and systematic maternal and newborn death audits. Health leadership should fairly distribute clinical guidelines, essential medicines, equipment and refresher trainings to improve availability and quality BEmONC.

Keywords: availability and readiness, obstetric and newborn care, low-income countries

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study in this region to identify factors associated with readiness to provide basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) using the recommended WHO service readiness indicators, and data obtained from a nationally representative sample.

By using a nationally representative sample, this suggests that our findings accurately reflect the current situation regarding availability and readiness to provide BEmONC in low-resource setting such as Tanzania.

The findings were adjusted for clustering effect and weighted to correct for complex sampling procedure and non-response and disproportionate sampling, respectively.

Being a cross-sectional study, causal relationship could not be established. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Misclassification bias, as a result of arbitrary cut-off point set at 50%, this might misclassify readiness of health facilities to provide BEmONC.

Introduction

Despite a global reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality over the past two decades,1 2 approximately 800 women and 7700 new-borns still die every day due to complications related to pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.3 4 It is estimated that 99% of these deaths occur in low-income countries (LICs) and middle-income countries,4 while 85% are contributed by LICs alone.5 6 Tanzania is among the LICs that continuous to experience a high burden of maternal and newborn deaths. This is despite increased coverage of antenatal care provided by skilled providers (96%–98%), facility delivery (50%–63%) and births assisted by skilled providers (51%–64%) between 2010 and 2016.7–10 Recent reports showed a remarkable increase of maternal mortality ratio (MMR) (from 454 to 556 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births), while neonatal mortality ratio (NMR) remained unchanged (26–25 deaths per 1000 live births) between 2010 and 2016.9 10 These estimates remain far from operational targets set by the Tanzanian Ministry of Health through the National Road Map Strategic Plan of 2008. This plan aimed to accelerate the reduction in maternal deaths to 193 per 100 000 live births and neonatal deaths to 19 per 1000 live births in Tanzania by the end of 2015.11 Given recent MMR estimates, one wonders whether Tanzania will be able to achieve targets for Sustainable Development Goal to reduce maternal deaths to less than 70 in 100 000 live births and neonatal deaths to less than 12 per 1000 live births at the end of 2030.12

This slow pace of MMR and NMR reduction observed in LIC including Tanzania, led the WHO to develop and recommend the availability of basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) services in each health facility as a key strategy to narrow disparities in global maternal and newborn deaths.4 13–15 BEmONC is an integrated strategy that aims to equip health facilities to deal with major causes of direct obstetric emergencies which account for the vast majority of maternal and newborn deaths, particularly in high mortality countries.16 17 This strategy comprises a package of seven key obstetric services or ‘signal functions’ including: (1) the ability of the facility to administer parenteral antibiotics, (2) administer uterotonic drugs (parenteral oxytocin), (3) administer parenteral anticonvulsants (eg, magnesium sulfate), (4) perform manual removal of placenta, (5) perform removal of retained products of conception, (6) perform assisted vaginal delivery and (7) perform basic neonatal resuscitation. Evidence has demonstrated that provision of BEmONC by skilled personnel results in better maternal and newborn outcomes18 and Tanzania and other LICs have partially implemented this strategy. However, the majority of health facilities lack some or all seven signal functions of BEmONC.18–20 For example in Tanzania, national BEmONC assessment survey of 2015 revealed that 13% of dispensaries, 28% of all health centres and 62% of hospitals were capable of performing all seven signal functions.21 These estimates are below the target that require all hospitals and at least 70% of health centres and dispensaries to provide BEmONC services.22 Furthermore, it is contrary to the effort made by Tanzanian government on improving maternal and newborn health such as developing number of policies and guidelines, as a response from international and regional policies and agreements (Delhi Declaration of 2005), that targets to reduce MMR and NMR.11 22 23

Countries with low availability of BEmONC services also experienced a high burden of maternal and newborn deaths.1 24 This correlation has been documented by previous studies and many researchers have identified critical gaps on BEmONC that if addressed could reduce the burden of high MMR and NMR in those countries.18 25 However, the majority of previous studies have concentrated on the assessment of services availability and few have assessed the readiness of the facilities to provide BEmONC services.26–30 In addition, these studies found low readiness of the facilities to provide BEmONC. Hence, there is little information regarding factors associated with low readiness of facilities to provide BEmONC in Tanzania. Better understanding of the factors associated with facility readiness to provide BEmONC is crucial to support maternal and newborn health system improvements.

To that end, this study used a nationally representative sample from Tanzania to assess the current extent of availability and readiness of health facilities to provide BEmONC services. Associated factors were also examined according to the type of facility and managing authority by using WHO-Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) manual31 with modification to some questions to fit the study setting.31 The findings from this study will provide a crucial guidance on important factors that need to be addressed to strengthen the BEmONC services for policy-makers, administrators and researchers in Tanzania and other LICs.

Methods

Data source

The analysed data of the current study was drawn from 2014 to 2015 Tanzania Service Provision Assessment (TSPA) survey dataset. The 2014–2015 TSPA was undertaken by Tanzania’s National Bureau of Statistics in collaboration with the Office of the Chief Government Statistician, Zanzibar, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Tanzania Mainland and the Ministry of Health, Zanzibar. Technical support for the survey was provided by ICF International under the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme. The survey assessed the facilities regarding availability and readiness of providing basic and essential health services, including the presence and function of components essential for the delivery of quality service for all aspects including maternal, newborn and child healthcare, family planning and reproductive health services.

Sample and sampling procedure

The sampling procedure used in TSPA survey is reported elsewhere.32 A random stratified sampling of health facilities according to facility type, managing authority and regions was used to select a nationally representative sample of 1200 facilities from the national master facility list contains 7102 health facilities. The selection of desirable health facilities was achieved after excluding seven facilities that refused to participate, four had closed on the interview days and one that could not be reached because of poor infrastructure. Then, a total of 1188 health facilities were assessed in 2014–2015 TSPA survey. However, after excluding 283 facilities that did not meet inclusion criteria (not providing any services related to maternal and newborn health), a total of 905 health facilities were included in the current analysis.

Data collection methods

The 2014–2015 TSPA used four main types of questionnaires during data collection. The current analysis used data collected by the Facility Inventory Questionnaire and one variable regarding staff training from Health Provider Questionnaire. After pre-testing of the questionnaires, the finalised and corrected versions were used in the main 2014–2015 TSPA survey data collection between 20 October, 2014 and 21 February, 2015. Additionally, visits of some facilities that were not covered previously were conducted from March 2 to March 13, 2015. The data collection was performed by 67 nurses who were trained for 4 weeks and were qualified by a series of practical tests and examinations to be interviewers. Following the training, 20 teams were formed (two for Zanzibar and 18 for Tanzania Mainland). Each team consisted of a team leader, three interviewers and a driver. On average, the data collection process lasted 1 day at a small facility (dispensary clinics and some health centres) and two or 3 days for large facilities (mostly hospitals). All collected data regarding the health facility service availability and readiness were provided by the manager, the person-in-charge of the facility, or the most senior health worker responsible for the client services present at the facility. The interviewers observed and verified the presence of valid or functioning reported services or supplies.

Measurement of variables

Based on our research questions, the current study identified two outcome variables which were ‘BEmONC services availability’ and ‘BEmONC services readiness’. These variables were measured by using the WHO methods of assessing facility service availability and readiness. Hence, ‘BEmONC services availability’ in this study is defined as ‘physical presence of the services related with provision of BEmONC’. This was measured based on whether the following seven signal functions have ever been carried out by providers as part of their work within facility at least once during the past 3 months: ‘parental administration of antibiotic’, ‘parental administration of oxytocic’, ‘parental administration of anticonvulsants’, ‘assisted vaginal delivery’, ‘manual removal of placenta’, ‘manual removal of retained products of conception’ and ‘neonatal resuscitation’.

‘BEmONC services readiness’ in this study is defined as the willingness or preparedness of the facility to provided BEmONC. This was measured based on the availability and functioning of supportive items categorised into three domains (groups) as follows: the first domain was staff training which had two indicators—the presence of guidelines and at least one staff who has received any formal or structured in-service training (refresher training) related to the services offered in the last 24 months preceding the assessment. The second domain was diagnostic equipment which had 11 indicators, that is, presence of ‘emergency transport’, ‘sterilisation equipment’, ‘examination light’, ‘delivery pack’, ‘suction apparatus’, ‘manual vacuum extractor’, ‘vacuum aspirator or D&C kit’, ‘neonatal bag and mask’, ‘delivery bed’, ‘partograph’ and ‘gloves’. The third domain was basic medicine and commodities which had 11 indicators contains essential medicines for delivery and newborn, that is, ‘injectable antibiotic’, ‘injectable uterotonic’, ‘injectable magnesium sulfate’, ‘injectable diazepam’, ‘intravenous fluids’, ‘skin disinfectant’, ‘antibiotic eye ointment’, ‘4% chlorhexidine’, ‘injectable gentamicin’, ‘injectable ceftriaxone’ and ‘amoxicillin suspension’. The BEmONC service readiness was then created as a composite score by adding the presence of each indicator, with equal weight given to each of the domains and each of the indicators within the domains. As the expected target was 100%, each domain accounted for 33.3% (100%/3) of the total score. The proportion of each indicator within the domain was equal to 33.3% divided by the number of indicators in that domain. The BEmONC service readiness score for each facility was then calculated by adding the proportions. Given that the readiness score is a relative measurement, then facilities that scored 50% or more were considered to be ready to provide BEmONC services than those scored less than 50% in BEmONC readiness score. This cut-off point of 50% was also used in previous studies.33 34

The outcome variables were examined against selected potential explanatory variables that we proposed as key variables that may potentially influence the availability or readiness of the health facility to provide BEmONC services. These variables were: facility location was coded as ‘0’ for urban and ‘1’ for rural. The facility type was coded as ‘0’ for clinic or dispensary, ‘1’ for a health centre and ‘2’ for a hospital. Managing authority was coded as ‘0’ for a public facility and ‘1’ for the private facility. Duty schedule for 24 hours was coded as ‘Yes’ for the facility that had a duty schedule or call list for 24 hours staff assignment, otherwise, the facility was coded as ‘No’. Quality assurance was coded as ‘performed’ for facility reported to perform quality assurance at least once per year, otherwise the facility was coded as ‘not performed’. Maternal or newborn deaths were coded as ‘reviewed’ for the facility that conducted regular reviews of maternal or newborn deaths or near-misses, otherwise, the facility was coded as ‘not reviewed’. Clients’ opinions were coded as ‘reviewed’ for facility reported having a system of determining and reviewing clients’ opinion, otherwise, the facility was coded as ‘not reviewed’. A number of staff and number of beds per facility remained as discrete quantitative variables.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using STATA V.14 (StataCorp, College Texas). For all the analyses, the ‘svy’ set command in STATA was used to adjust for the complex sampling design employed by TSPA survey. Moreover, as the facilities sampled were not evenly distributed and the response rate might be very different by regions or facility type, then over and under-sampled in the regions with fewer and more facilities respectively were performed before data collection. Therefore, before analysis, facility weight was used to restore the actual representativeness of the facilities sampled.

In the descriptive analysis, continuous variables were summarised using either mean (SD) for normally distributed variables or median (IQR) for non-normal distributed variables. All categorical variables were summarised using proportions and then presented in tables and graphs. Bivariate and multivariable regression models were fitted to assess the existence of the association between the outcome variable (BEmONC service readiness) and the explanatory variables. As the aim was to fit a final model that predicts the association, the objective criterion-based method was used to include or exclude variable in the multiple regression models. A t-test for each of the coefficient in multiple regression model was calculated and used to test for the association. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistically significant association.

Ethics statement

This study was based on an analysis of existing public domain survey data sets that are freely available online with all identifier information detached. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the ICF Macro at Calverton in the USA and by the National Institute of Medical Research Ethics Committee in Tanzania. Informed consent was requested and obtained from participants before the interview.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patient and public were not involved in the analysis of this study.

Results

General characteristics of surveyed facilities

Table 1 presents a summary of the general characteristics of the included health facilities. Out of 1188 facilities involved in the TSPA survey, 905 (76.18%) reported to provide delivery and new-borns care services and therefore were included in the analysis of the current study. More than 80% of the facilities were located in rural area and publicly owned. Less than 30% of the facilities regularly reviewed maternal and newborn deaths or ‘near-misses’ cases that occurred within the facility. Overall, the number of staffs per facility was low with a median (IQR) of 3 (2 - 6).

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of surveyed facilities according to background characteristics, Tanzania Service Provision Assessment 2014–2015 (n=905)

| Variable | n (%) |

| Facility location | |

| Rural | 773 (85.41) |

| Urban | 132 (14.59) |

| Facility type | |

| Clinic and dispensary | 751 (82.98) |

| Health centre | 110 (12.16) |

| Hospital | 44 (4.86) |

| Managing authority | |

| Public | 756 (83.54) |

| Private | 149 (16.46) |

| Duty schedule for 24 hours | |

| Yes | 256 (28.29) |

| No | 649 (71.71) |

| Quality assurance | |

| Performed | 149 (16.46) |

| Not performed | 756 (83.54) |

| Maternal/newborn deaths | |

| Reviewed | 182 (20.11) |

| Not reviewed | 723 (79.89) |

| Clients’ opinions | |

| Reviewed | 272 (30.06) |

| Not reviewed | 633 (69.94) |

| Number of staffs per facility | |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2,6) |

| Number of delivery beds per facility | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.41 (1.02) |

Seven signal functions for BEmONC by type of facility and managing authority

Table 2 shows the distribution of the availability of seven signal function for BEmONC by type of facility and managing authority. Overall availability of these seven signal functions (parental administration of the antibiotic, parental administration of oxytocic, parental administration of anticonvulsant, assisted vaginal delivery, manual removal of placenta, manual removal of retained products of conception and neonatal resuscitation) were consistently higher among hospitals than health centres and dispensaries (p<0.001). Despite the fact that private facilities consistently reported the higher availability of these seven signal functions compared with public facilities, only parental administration of the antibiotic, parental administration of anticonvulsants and neonatal resuscitation were significantly higher in private facilities (p<0.001). Regardless of facility type and managing authority, majority of the facilities reported high availability of parental administration of oxytocic (83.61%), assisted vaginal delivery (69.60%) and neonatal resuscitations (52.14%) while less than half of all facilities reported availability of manual removal of retained products of conception (35.36%), parental administration of antibiotic (34.01%), manual removal of placenta (33.95%) and parental administration of anticonvulsants (13.35%).

Table 2.

Percentage distribution of seven signal functions for basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services by type of facility and managing authority, Tanzania Service Provision Assessment 2014–2015 (n=905)

| Variable | Facility type | Managing authority | Total n (%) |

|||

| Dispensary/Clinic n (%) | Health centre n (%) |

Hospital n (%) |

Public n (%) |

Private n (%) |

||

| Parental administration of antibiotic | 205 (27.32) | 66 (60.01) | 37 (83.95)* | 242 (32.04) | 66 (44.03)* | 308 (34.01) |

| Parental administration of oxytocin | 614 (81.77) | 100 (90.94) | 42 (96.86)* | 633 (83.69) | 123 (83.16) | 756 (83.61) |

| Parental administration of anticonvulsants | 52 (6.96) | 35 (31.59) | 34 (77.56)* | 83 (10.93) | 38 (25.63)* | 121 (13.35) |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 511 (68.00) | 80 (72.85) | 39 (88.94)* | 525 (69.50) | 104 (70.11) | 629 (69.60) |

| Manual removal of placenta | 227 (30.22) | 50 (45.34) | 30 (69.66)* | 248 (32.87) | 59 (39.46) | 307 (33.95) |

| Manual removal of retained products of conception | 234 (31.10) | 56 (51.35) | 30 (68.56)* | 264 (34.88) | 56 (37.79) | 320 (35.36) |

| Neonatal resuscitation | 352 (46.78) | 80 (73.05) | 40 (92.03)* | 383 (50.64) | 89 (59.76)* | 472 (52.14) |

| Number of facilities providing normal delivery services | 751 | 110 | 44 | 756 | 149 | 905 |

*P<0.05 according to type of facility.

The availability of seven functions were based on whether the intervention has been carried out at least once during the past 3 months.

Availability of important supportive items for delivery and newborns care services

Human resources (staff training)

Only (206, 22.75%) facilities reported having at least one staff who had received refresher training in delivery and newborn care. Also, about one-third (270, 29.80%) of facilities reported having recommended guidelines related to delivery and newborn care.

Essential equipment and supplies

Overall, the majority (890, 98.35%) of facilities reported dedicating at least one bed for delivery purposes, (780, 86.24%) had sterile gloves, (760, 84.05%) had delivery packs and (692, 76.48%) had a neonatal bags and masks for resuscitation. However, less than a quarter of facilities reported having suction apparatus (23.14%), sterilisation equipment (20.75%), examination light (14.37%), vacuum aspirator or dilatation and curettage D&C kit (7.51%), or manual vacuum extractor (5.31%).

Medicines and commodities

Regarding availability of essential medicines for delivery, injectable uterotonic (78.81%), skin disinfectant (61.10%) and injectable diazepam (55.23%) were often available, while intravenous fluids (48.15%), injectable magnesium sulfate (40.77%), injectable antibiotic (32.11%) were not widely available. On the other hand, regarding essential medicines for newborn care, more than half of facilities reported availability of amoxicillin suspension (62.90%) and injectable ceftriaxone (56.69%) while less than one-third of facilities reported availability of injectable gentamicin (29.54%), antibiotic eye ointment (28.05%) and 4% chlorhexidine (11.95%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Indicators of readiness to providing basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services, Tanzania Service Provision Assessment 2014–2015 (n=905)

| Indicators | n (%) of facilities in which indicator is available |

| Staff and training | |

| Presence of guidelines | 270 (29.80) |

| Availability of trained staff | 206 (22.75) |

| Equipment and supplies | |

| Emergency transport | 567 (62.54) |

| Sterilisation equipment | 188 (20.75) |

| Examination light | 130 (14.37) |

| Delivery pack | 760 (84.05) |

| Suction apparatus | 209 (23.14) |

| Manual vacuum extractor | 48 (5.31) |

| Vacuum aspirator or D&C kit | 68 (7.51) |

| Neonatal bag and mask | 692 (76.48) |

| Delivery bed | 890 (98.35) |

| Partograph | 520 (57.51) |

| Gloves | 780 (86.24) |

| Medicines and commodities | |

| Essential medicines for delivery | |

| Injectable antibiotic | 291 (32.11) |

| Injectable uterotonic | 713 (78.81) |

| Injectable magnesium sulfate | 368 (40.77) |

| Injectable diazepam | 500 (55.23) |

| Intravenous fluids | 436 (48.15) |

| Skin disinfectant | 553 (61.10) |

| Essential medicines for new-borns | |

| Antibiotic eye ointment | 254 (28.05) |

| 4% Chlorhexidine | 108 (11.95) |

| Injectable gentamicin | 267 (29.54) |

| Injectable ceftriaxone | 513 (56.69) |

| Amoxicillin suspension | 569 (62.90) |

Facility readiness to provide BEmONC services

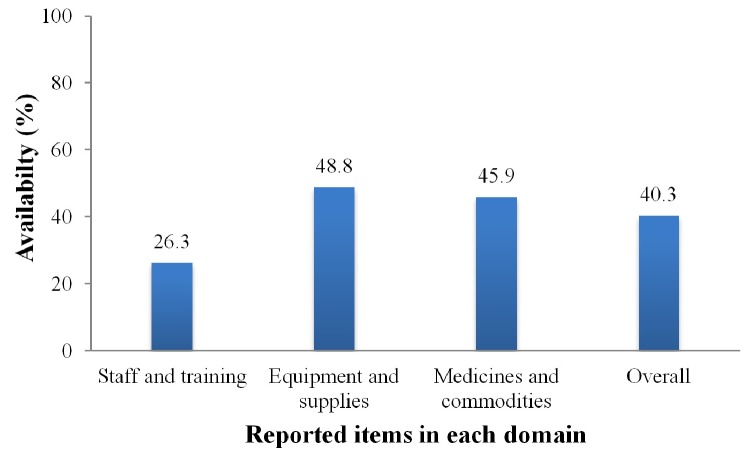

Figure 1 shows the readiness score corresponding to the three domains and the overall index of facility readiness to provide BEmONC. Each of the three domains had an average readiness score of less than 50% based on the indicators suggested by WHO-SARA manual, that yield overall mean readiness score (SD) of 40.3 (17.6)%. However, 267 (29.50%) of all health facilities had overall percentage readiness score of 50% or more, therefore, were considered ready to provide BEmONC services. Overall BEmONC readiness score according to the type of facility and managing authority

Figure 1.

Percentage score of the three domains of readiness to provide basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services.

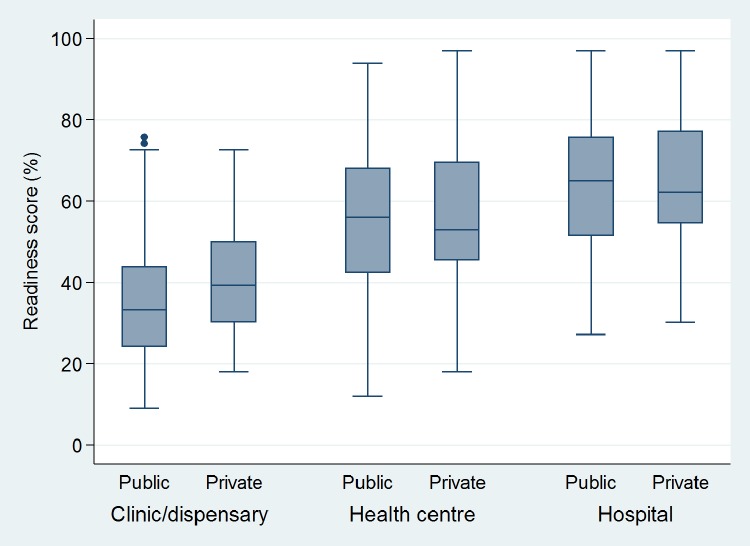

The overall readiness score was found to differ significantly according to the type of facility, with a higher score among hospitals compared with dispensaries (p<0.001). However, there was no difference in the overall readiness score according to the managing authority at each level of facility type (p>0.05) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall readiness score for providing basic emergency obstetric and newborn care according to the type of facility and managing authority.

Factors associated with facility readiness to provide BEmONC services

Table 4 presents the results of the bivariate and multivariate analysis. In bivariate analysis, all explanatory variables showed association with outcome variable ‘BEmONC service readiness’ at p<0.05, therefore, were selected and included in multiple regression models by using objective criterion-based methods to predict their association with readiness to provide BEmONC services. The results of multiple regression analysis showed that the readiness of facility to provide BEmONC services was higher at health centres (11.54% points better than dispensary and clinics), at facilities which performed quality assurance (5.45% points better than those not performed), at facilities reported regular reviewing maternal, newborn deaths or ‘near-misses’ (6.49% points better than those not reviewed), at facilities that reviewed clients opinion about heath facility or its services (4.29% points better than those not reviewed clients opinions) and facility with more delivery beds (2.44% points for each doubling of beds per facility).

Table 4.

Results of unadjusted and adjusted multiple regression models of factors associated with readiness to provide basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services, Tanzania Service Provision Assessment 2014–2015 (n=905)

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient† | SE | |

| Facility location (ref: rural) | ||||

| Urban | 8.64** | 2.29 | 0.20 | 2.08 |

| Facility type (ref: clinic/dispensary) | ||||

| Health centre | 18.15** | 1.24 | 11.54** | 2.02 |

| Hospital | 26.09** | 2.54 | 8.06 | 4.15 |

| Managing authority (ref: public) | ||||

| Private | 8.46** | 1.90 | 3.56 | 1.87 |

| Duty schedule for 24 hours (ref: no) | ||||

| Yes | 12.28** | 1.62 | 0.52 | 2.13 |

| Quality assurance (ref: not performed) | ||||

| Performed | 14.24** | 2.36 | 5.45* | 2.44 |

| Maternal/newborn deaths (ref: not reviewed) | ||||

| Reviewed | 14.76** | 1.76 | 6.49** | 1.89 |

| Clients’ opinions reviewed (ref: no) | ||||

| Yes | 9.90** | 1.74 | 4.29* | 1.68 |

| Number of staffs per facility | ||||

| (as continuous variable) | 0.09** | 0.04 | −0.001 | 0.013 |

| Number of delivery beds per facility | ||||

| (as continuous variable) | 6.28** | 0.58 | 2.44* | 0.83 |

*P<0.05; **P<0.001.

†Adjusted coefficient: each variable in the model has been adjusted by all variables.

Discussion

This study used a nationally representative data from Tanzania as an example of low-resource country to assess the availability and readiness of health facilities to provide BEmONC services among health facilities. The study findings indicate a relatively poor readiness of Tanzanian health facilities to provide BEmONC services. The observed scarcity of human resource (trained providers), essential diagnostic equipment, and basic medicine resulted into poor readiness of the facilities to provide BEmONC. The observed poor facility readiness to provide BEmONC in this study, extend the findings from other studies across different regions of LICs.35 36 These findings continue to highlight essential gaps in delivery maternal and newborn services that are obstacles to universal access to health services.37 Therefore, the findings have greater implications for the improvement of emergency obstetric care in Tanzania and other LICs.

Availability of seven signal functions for BEmONC is crucial to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality.38 The current study found disparities in the availability of these seven signal functions according to the type of facility and managing authority. Despite the fact that private facilities consistently reported higher availability of the seven signal functions compared with public facilities, only three signal functions: parental administration of the antibiotic, parental administration of anticonvulsants and neonatal resuscitation were significantly more reported in privately owned than publicly owned facilities. Similarly, hospitals were found to report significantly greater availability of the signal functions than lower-level facilities (health centres and dispensaries). These findings are in agreement with a study conducted in Haiti in 2014.39 The similarity of the findings of these studies might be due to the similar methodology used; both studies used data from the national representative sample collected by DHS programme. Therefore, the questionnaire used for the interviews were nearly similar. Also, Tanzania and Haiti share socio-economic determinants as these two countries are both LICs.

Furthermore, our results indicate that availability of parental administration of anticonvulsants (magnesium sulfate) is still a challenge and as a result, it compromises the provision of BEmONC in Tanzania particularly in public and lower-level health facilities. A similar finding has been reported in another low-resource setting.28 Inadequate availability of this important component of BEmONC, might led to unnecessary delays to prevent or intervene pre-eclampsia/eclampsia that is one of the three leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality.40 Together with other suboptimal availability of parental administration of antibiotic, manual removal of placenta and retained products of conception suggesting that, despite the increased coverage of antenatal care, facility deliveries, and postnatal care, these efforts alone cannot reduce MMR and NMR without improving the availability of BEmONC services.41 42 The low availability of seven signal functions in the public and lower-level facilities in Tanzania is further impacted by the current long process of ordering and delivering of drugs and medical supplies through a system called integrated logistic system. With this system, facility places its order through District Medical Officer’s office to the Medical Department Store, a body that operates under Ministry of Health responsible for managing all the procurement and supply of medical items concerning public facilities.43 Hence, any faults or delays in the ordering system may result in the low availability of items or services in the facilities. These delays will compromise efforts towards achieving targets set by the Tanzanian government that all hospitals and at least 70% of health centres and dispensaries be able to provide BEmONC services at the end of 2020.22

Facility readiness is an important aspect that demonstrates a facility’s commitment to ensuring cumulative availability of components required to provide a specific service.31 Our analysis identified the significant difference of BEmONC readiness according to the type of facility, in which higher level facilities (hospitals) were found to have high readiness score compared with lower-level facilities (dispensaries/clinics). The suboptimal readiness observed in the lower-level facilities might be due to unclear formula on how to allocate funds in these facilities that may contribute to insufficiencies and inequities in the distribution of medical supplies.43 The strengthening of the lower-level facilities which are usually located in the rural areas and serve about 75% of Tanzanian population is highly needed to address the increasing burden of maternal and neonatal deaths. The finding is in agreement with the previous study conducted in Kenya.30

Quality assurance is a process that aims to promote a high standard of the service provision within healthcare systems.44 The results of this study show that facilities that performed quality assurance were more likely to be ready to provide BEmONC services compared with facilities not engaged in quality assurance activities. This might be due to the fact that, quality assurance involves continuous monitoring and persistent feedback to improve services offered.45 Therefore, based on recommendations from quality assurance teams, these facilities are more likely to improve the availability of services that may result in their high readiness score. However, the uptake of quality improvement and quality assurance activities remains low within the Tanzanian health system as a small number of health facilities regular perform such activities.46

Each maternal or newborn death has a story to tell,47 therefore, review of these deaths is widely recognised as a recommended tool to improve obstetric and neonatal care.48 Our results show that facilities which perform maternal and newborn death reviews were more likely to be ready to provide BEmONC services compared with facilities that did not perform these reviews. It may be that facilities that perform death reviews use that information to improve BEmONC service availability and readiness. Despite the maternal death reviews have been imposed over the past two decades as the national policy to improve the quality of BEmONC services the results show that majority of Tanzania health facilities do not regularly perform such kind of reviews.49 Therefore, the number of facilities miss the opportunity of reflection and direct feedback to improve the BEmONC services.50 51

Also, clients’ opinions are beneficial parameter for judging the availability and readiness of the facility to provide specific services. The results of this study indicate that facilities which review clients’ opinion were more likely to be ready to provide BEmONC services. This might be explained by the fact that clients’ opinions not only reflect the satisfaction with service received but also provide positive and negative feedback towards services provided by facility or health providers.52 This feedback may be used to correct the shortcomings highlighted by patients, hence improve the availability of services that are important aspect to assess the readiness of the facility to provide services. However, we also found low number of health facilities that regularly collect and review clients’ opinion regarding the provision of maternal and newborn services.

Despite on-the-job training creates an opportunity of healthcare providers to receive the up-to-date information and skills required to provide better healthcare.33 The results of this study indicated a low proportion of health facilities with at least one staff member trained in providing delivery and newborn care services. This severe lack of trained staff together with shortage of health workers in health facilities reported in previous studies, may compromise the readiness of the facilities to provide BEmONC in Tanzania.53 54 Although, the Tanzanian government made several efforts to deal with shortage of human resources and other challenges in the health system, yet its heath budgets over decades remained consistently below Abuja target of 15%.54 55 This might explain the observed low readiness of the facilities to provide BEmONC and that the MMR remains high if inadequate budgets are allocated to improve maternal and child health services.

The strength of the current study is that it analysed a nationally-representative sample of health facilities in Tanzania, providing key insight into the BEmONC availability and readiness in the LICs with higher MMR and NMR. It provides important information about the current situation regarding availability and readiness of facilities to provide BEmONC in a resource-constrained environment. Since TSPA survey employed complex sampling procedures, the estimates were adjusted for clustering effect and weighted to correct for non-response and disproportionate sampling. However, this study had some limitations, being a cross-sectional study, causal relationship could not be established. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Also, the study is subjected to misclassification bias due to the use of arbitrary cut-off point set at 50%; this might be misclassified readiness of health facilities to provide BEmONC services. Though, the effect of this bias has been minimised by inclusion of many indicators as suggested by WHO to assess the level of facility readiness.

In summary, the results of this study indicate disparities in the availability of seven signal functions and readiness to provide BEmONC services among health facilities in Tanzania. It also highlighted the gaps in the availability of important supportive items such as refresher training and clinical guidelines for the provision of BEmONC. To improve the quality of BEmONC services, there are key steps that government authorities might consider. These includes:- the emphasis on quality assurance and quality improvement activities and implementation of regular maternal and newborn death audits. In order to improve BEmONC services, the health system leaders should implement strategies to better ensure fair distribution of clinical guidelines, essential medicines, equipment, and refresher training. Additional studies may be useful to ensure effective implementation of government policies to support the readiness of health facilities to provide BEmONC services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA, through DHS programme for permitting us to access the Tanzania SPA 2014-2015 dataset.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: DB conceptualised and designed the study, performed statistical analysis and wrote the first and revised draft of the manuscript. AE involved in the interpretation of data, revised and edited the manuscript. BM provided advice on statistical analysis, interpretation of data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets generated during the current study are available from within the Demographic and Health Survey Program repository: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang H, Bhutta ZA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1725–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:957–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO). Maternal mortality fact sheet. 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/ (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 5. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e323–33. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 2005;365:891–900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016;387:1–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawn J, Mongi P, Cousens S. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns: Africa’s newborns – counting them and making them count. 2006.

- 9. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [Tanzania] and ICF Macro. 2011. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: NBS and ICF Macro. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR243/FR243%5B24June2011%5D.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 10. Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW). The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal, Newborn and Child Deaths in Tanzania (2008-15). 2008. http://www.who.int/pmnch/countries/tanzaniamapstrategic.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 12. United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016: United Nations, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salam RA, Mansoor T, Mallick D, et al. Essential childbirth and postnatal interventions for improved maternal and neonatal health. Reprod Health 2014;11:S3 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S1-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paxton A, Maine D, Freedman L, et al. The evidence for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;88:181–93. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pearson L, Shoo R. Availability and use of emergency obstetric services. 15 Kenya, Rwanda, Southern Sudan, and Uganda., 2005:208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization (WHO), UNFPA, UNICEF and Mailman School of Public Health. Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AMDD). Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhandari TR, Dangal G. Emergency obstetric care: strategy for reducing maternal mortality in developing Countries. Nepal J Obstet Gynaecol 2014;9:8–16. 10.3126/njog.v9i1.11179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holmer H, Oyerinde K, Meara JG, et al. The global met need for emergency obstetric care: a systematic review. BJOG 2015;122:183–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ueno E, Adegoke AA. Skilled birth attendants in Tanzania: a descriptive study of cadres and emergency obstetric care signal functions performed. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Banke-Thomas A, Wright K, Sonoiki O, et al. Assessing emergency obstetric care provision in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the application of global guidelines. Glob Health Action 2016;9:31880–13. 10.3402/gha.v9.31880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. United Republic of Tanzania (URT).. National Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC) Assessment. RCHS, Directorate of Preventive Services, United Republic of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam. 2015.

- 22. Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC). The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Improve Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health in Tanzania (2016 - 2020) (One Plan II). 2016. http://globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/documents/Tanzania_One_Plan_II.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 23. Mkoka DA, Kiwara A, Goicolea I, et al. Governing the implementation of emergency obstetric care: experiences of rural district health managers, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:333 10.1186/1472-6963-14-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koblinsky M, Moyer CA, Calvert C, et al. Quality maternity care for every woman, everywhere: a call to action. Lancet 2016;388:2307–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31333-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otolorin E, Gomez P, Currie S, et al. Essential basic and emergency obstetric and newborn care: from education and training to service delivery and quality of care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;130:S46–53. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Echoka E, Kombe Y, Dubourg D, et al. Existence and functionality of emergency obstetric care services at district level in Kenya: theoretical coverage versus reality. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:113 10.1186/1472-6963-13-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wichaidit W, Alam MU, Halder AK, et al. Availability and Quality of Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016;95:298–306. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roy L, Biswas TK, Chowdhury ME. Emergency obstetric and newborn care signal functions in public and private facilities in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187238 10.1371/journal.pone.0187238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tecla SJ, Franklin B, David A, et al. Assessing facility readiness to offer basic emergency obstetrics and neonatal care (BEmONC) services in health care facilities of west Pokot county, Kenya. J Clin Simul Res 2017;7:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Measure Evaluation PIMA. Health facility readiness to provide emergency obstetric and newborn care in Kenya: results of a 2014 assessment of 13 Kenyan Counties with High Maternal Mortality. Nairobi, Kenya: MEASURE Evaluation PIMA, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Health Statistics and Information Systems, World Health Organization (WHO). Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): an annual monitoring system for service delivery: reference manual, Version 2.2. 2014. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_reference_manual/en/ (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 32. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF International 2015. Tanzania Service Provision Assessm. 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA22/SPA22.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 33. Bintabara D, Nakamura K, Seino K. Determinants of facility readiness for integration of family planning with HIV testing and counseling services: evidence from the Tanzania service provision assessment survey, 2014-2015. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:844 10.1186/s12913-017-2809-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bintabara D, Mpondo BCT. Preparedness of lower-level health facilities and the associated factors for the outpatient primary care of hypertension: Evidence from Tanzanian national survey. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192942 10.1371/journal.pone.0192942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gage AJ, Ilombu O, Akinyemi AI. Service readiness, health facility management practices, and delivery care utilization in five states of Nigeria: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:297 10.1186/s12884-016-1097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kozuki N, Oseni L, Mtimuni A, et al. Health facility service availability and readiness for intrapartum and immediate postpartum care in Malawi: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172492 10.1371/journal.pone.0172492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O’Neill K, Takane M, Sheffel A, et al. Monitoring service delivery for universal health coverage: the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:923–31. 10.2471/BLT.12.116798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang W. Influence of Service readiness on us of facility delivery care: a study linking health facility data and population in Haiti [WP114]. DHS Work Pap 2014;114. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B. Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Semin Perinatol 2012;36:56–9. 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mselle LT, Moland KM, Mvungi A, et al. Why give birth in health facility? Users’ and providers’ accounts of poor quality of birth care in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:174 10.1186/1472-6963-13-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mkoka DA, Goicolea I, Kiwara A, et al. Availability of drugs and medical supplies for emergency obstetric care: experience of health facility managers in a rural District of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:108 10.1186/1471-2393-14-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sikika. Medicines and medical supplies availability report. Using absorbent gauze availability survey as an entry point. A case of 71 districts and 30 health facilities across mainland Tanzania. Sikika. 2011. http://sikika.or.tz/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/medicines-and-medical-and-supply-availability-report.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 44. Busari JO. Comparative analysis of quality assurance in health care delivery and higher medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract 2012;3:121 10.2147/AMEP.S38166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Jonge V, Sint Nicolaas J, van Leerdam ME, et al. Overview of the quality assurance movement in health care. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2011;25:337–47. 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW). In-depth assessment of the medicines supply system in Tanzania. WHO. 2008. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s16503e/s16503e.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 47. Lewis G. Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. Br Med Bull 2003;67:27–37. 10.1093/bmb/ldg009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kongnyuy EJ, van den Broek N. The difficulties of conducting maternal death reviews in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:42 10.1186/1471-2393-8-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW). The National Road Map strategic plan to accelerate reduction of maternal, newborn and child deaths in Tanzania 2008 - 2015. 2008. http://www.who.int/pmnch/countries/tanzaniamapstrategic.pdf (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

- 50. Wagaarachchi PT, Graham WJ, Penney GC, et al. Holding up a mirror: changing obstetric practice through criterion-based clinical audit in developing countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001;74:119–30. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00427-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sorensen BL, Elsass P, Nielsen BB, et al. Substandard emergency obstetric care - a confidential enquiry into maternal deaths at a regional hospital in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:894–900. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gupta KS, Rokade V. Importance of quality in health care sector. J Health Manag 2016;18:84–94. 10.1177/0972063415625527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Manzi F, Schellenberg JA, Hutton G, et al. Human resources for health care delivery in Tanzania: a multifaceted problem. Hum Resour Health 2012;10:3 10.1186/1478-4491-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Afnan-Holmes H, Magoma M, John T, et al. Tanzania’s Countdown to 2015: an analysis of two decades of progress and gaps for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health, to inform priorities for post-2015. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e396–409. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00059-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW). Health sector public expenditure review, 2010/11. 2012. https://www.hfgproject.org/health-sector-public-expenditure-review-201011/ (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.