Abstract

SUMMARY – The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between globus pharyngeus and laryngopharyngeal reflux, as well as between globus and thyroid volume. A two-year prospective study included 56 patients aged 18-75 with globus symptom. Anthropometric, clinical and laboratory data were collected. All patients filled-out the Glasgow Edinburgh Throat Scale (GETS) and then underwent thyroid ultrasound. Morphological changes of the larynx were detected by direct laryngoscopy and classified by the Reflux Finding Score (RFS). If RFS >7, the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux was made and therapy with proton pump inhibitors initiated. According to GETS, there was significant difference between patients with normal volume and those with large thyroid volume. There was no statistically significant difference between patients with RFS <7 and RFS >7. In conclusion, the incidence and severity of globus pharyngeus do not definitely indicate laryngopharyngeal reflux. It is more common in patients with normal thyroid volume.

Key words: Laryngopharyngeal reflux, Pharyngeal diseases, Thyroid gland, Ultrasonography, Proton pump inhibitors, Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Globus pharyngeus is a sensation of having a lump or foreign body in the throat (1, 2). It is a common condition accounting for 3%-4% of new otorhinolaryngology outpatient referrals (3). It is reported by up to 46% of apparently healthy individuals, with a peak incidence in middle age (4, 5). This condition is equally prevalent in men and women (6). Hippocrates first noted it approximately 2500 years ago (7). In the past, globus was described as globus hystericus because of its frequent association with menopause or psychogenic factors (8). In 1968, after discovering that most patients experiencing globus did not have a hysterical personality, the more accurate term ‘globus pharyngeus’ was coined (9). The etiology remains elusive. Although data are limited, previous studies investigated links with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (10-18), esophageal dysmotility (19), abnormalities of the upper esophageal sphincter (20), temporomandibular joint dysfunction (21), pharyngeal inflammation (22, 23), enlarged lingual tonsils (24), upper aerodigestive malignancy (7, 25,) psychological factors, and stress (26, 27). As globus cannot be assessed by clinical examination, there is a validated questionnaire, the Glasgow Edinburgh Throat Scale (GETS) that can appraise with high probability the incidence and severity of globus (28). From the aspect of otorhinolaryngologist, the most important connection of the globus is with thyroid diseases and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). LPR is known as direct irritation and inflammation of the laryngopharynx by retrograde flow of gastric contents (15, 16). Globus pharyngeus appears in 95% of patients with LPR, which is besides throat clearing (98%), persistent cough (97%) and hoarseness (95%), one of the leading symptoms of this disease (29). The Reflux Finding Score (RFS) validates morphological changes of laryngeal mucosa, which occur as the result of LPR and can be demonstrated by direct laryngoscopy. The changes of the larynx can include subglottic edema, ventricular obliteration, erythema/hyperemia, vocal fold edema, diffuse laryngeal edema, posterior commissure hypertrophy, granuloma and thick endolaryngeal edema (30). Each of the mentioned parameters is separately evaluated and the possible score range is from 0 (normal) to 26 (worst possible score). RFS >7 indicates a diagnosis of LPR. Some other diagnostic methods for detecting LPR are contrast radiology, 24-hour pH-monitoring, and multichannel intraluminal impedance (MCII) (31). All these methods are invasive and they are used in cases when empirical treatment fails. The main medication in LPR treatment is proton pump inhibitor (PPI), which diminishes daily production of gastric acid and strengthens sphincter tone. Besides patients suffering from LPR, globus pharyngeus also occurs in 30% of patients with thyroid pathology (1). The patients with globus symptom that underwent thyroidectomy had the following histologic diagnoses: multi-nodular and colloid goiter, follicular adenoma, carcinoma, and thyroiditis. The aim of this study was to investigate the cause-and-effect connection between globus pharyngeus and LPR, between globus and thyroid volume, as well as to compare the results obtained in order to administer appropriate treatment to patients with globus pharyngeus.

Patients and Methods

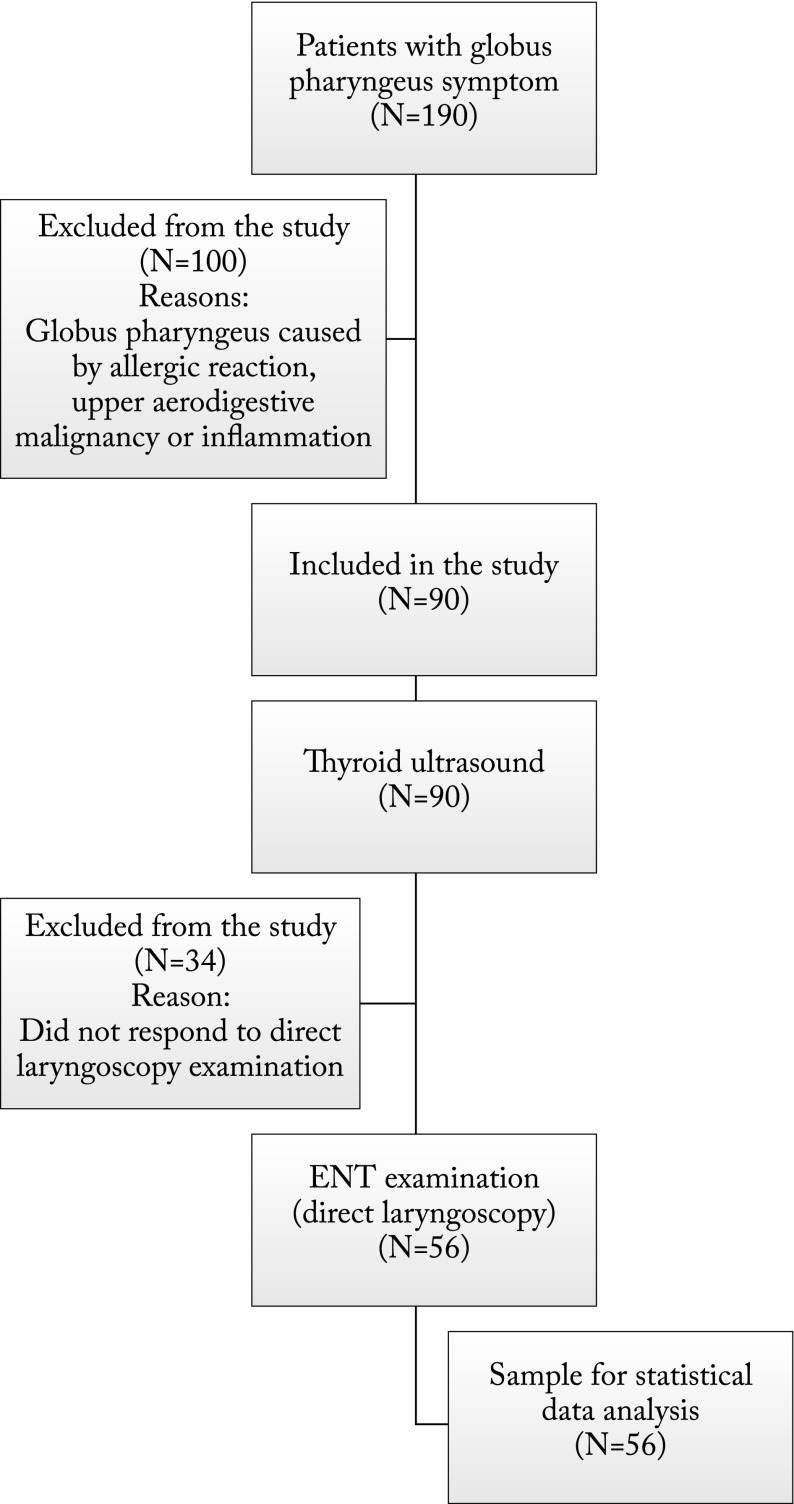

This cross-sectional prospective two-year study was conducted at the University Department of ENT, Head and Neck Surgery and Department of Nuclear Medicine, Split University Hospital Centre in Split. It included 56 patients aged 18-75 referred by their family physician for diagnostic work-up at Department of Nuclear Medicine for globus symptom. The patients who had globus due to allergic reactions, pharyngeal inflammation and upper aerodigestive malignancy were excluded. Anthropometric, clinical and laboratory data were collected. Anthropometric data included patient age (years), sex, neck circumference (cm), body weight (kg), height (m) and body mass index (kg/m2). On assessing the severity of globus symptom, data were analyzed by use of GETS, which the patients filled-out at Department of Nuclear Medicine. Each patient was asked to assess the sensation of globus pharyngeus by completing the 10-item questionnaire about common throat symptoms (28). Symptom intensity is graded by numbers from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 7 (highest symptom intensity). After completing the questionnaire, thyroid ultrasound (Aloka SSD-400 sv, Tokyo, Japan) was performed to determine dimensions of the thyroid (separately left and right lobe and isthmus) in millimeters (mm). The volume of each lobe and isthmus was calculated by the formula: width (cm) × depth (cm) × length (cm) × 0.524 (correction factor) (32). The total thyroid volume was the sum of the right lobe volume, left lobe volume and isthmus volume. At the University Department of ENT, direct laryngoscopy was performed to determine RFS. Patients with RFS ≥7 were diagnosed with LPR and prescribed PPI medication 2x20 mg for at least 3 months (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

The study was approved by the Split University Hospital Centre Ethics Committee and conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. All the participants signed a written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the MedCalc for Windows, version 11.5.1.0 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) statistical software. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were presented as number and percentage.

Results

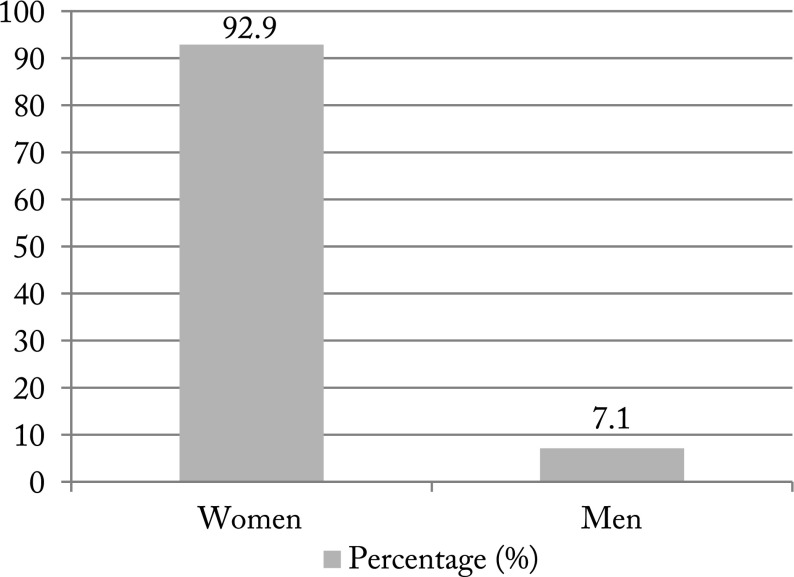

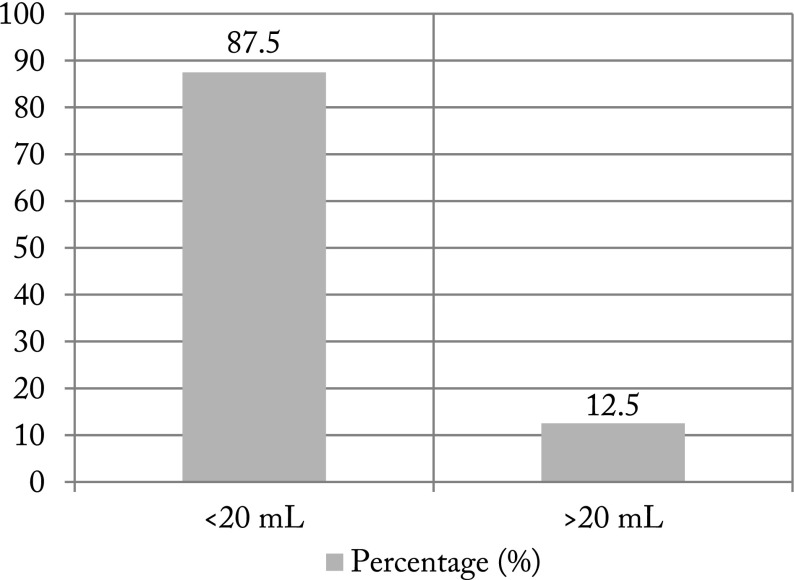

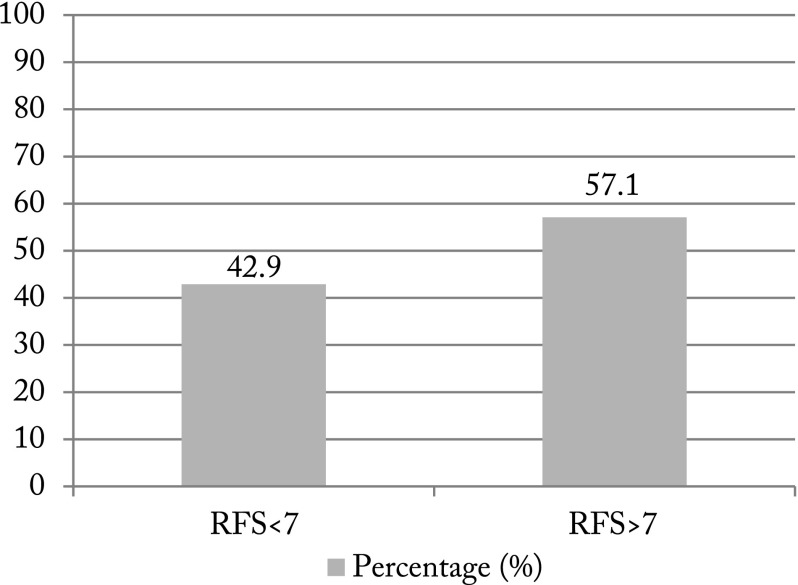

The study included 56 (52 female and four male) patients (Fig. 2). Demographic data of these patients are shown in Table 1. The most prominent symptoms in GETS were “Feeling of something stuck in the throat”, “Want to swallow all the time” and “Difficulty in swallowing food” (Table 2). Results of normal thyroid volume (<20 mL) and increased thyroid volume are shown in Figure 3. Results of patients with RFS <7 and patients with RFS >7, which indicated a diagnosis of LPR, are illustrated in Figure 4. In patients with RFS >7, the most common finding was thick endolaryngeal mucus (n=31), followed by partial ventricular obliteration (n=28), moderate diffuse laryngeal edema (n=24), erythema/hyperemia of arytenoids (n=21) and moderate vocal cord edema (n=20). There was a statistically significant difference between patients with normal thyroid volume and those with large thyroid volume (p<0.001), but there was no such difference between patients with RFS <7 and RFS >7 (p=0.13).

Fig. 2.

Patient distribution according to gender.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study patients.

| Patients (N=56) | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Median (range) |

| Age (years) | 44 (20-78) |

| Height (m) | 1.69 (158-188) |

| Weight (kg) | 70 (38-100) |

| Mean ± standard deviation | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.3±4.01 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 34.5±2.98 |

Table 2. Results on symptoms rated by the Glasgow and Edinburgh Throat Scale.

| Symptom | Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling of something stuck in the throat | 4.70 | 1.98 | 5 | 6 |

| Pain in the throat | 2.37 | 1.31 | 2 | 1 |

| Discomfort/irritation in the throat | 3.37 | 1.96 | 3 | 2 |

| Difficulty in swallowing food | 4.06 | 1.71 | 4 | 3 |

| Throat closes off | 3.88 | 1.97 | 4 | 3 |

| Swelling in the throat | 3.76 | 2.02 | 4 | 3 |

| Catarrh in the throat | 3.80 | 1.95 | 4 | 2 |

| Can’t empty throat when swallowing | 3.60 | 1.44 | 4 | 4 |

| Wanting to swallow all the time | 4.27 | 1.83 | 4 | 5 |

| Food sticking when swallowing | 2.93 | 1.64 | 3 | 3 |

Fig. 3.

Patient distribution according to thyroid volume (mL).

Fig. 4.

Patient distribution according to Reflux Finding Score (RFS) <7 and RFS >7.

Discussion

Although globus pharyngeus often appears as a clinical symptom because of its multifactorial and insufficiently examined etiology, the globus symptom is usually treated inappropriately. Many conditions have been considered in its causation, including cervical osteophytes (33), cricopharyngeal spasm (24), cervical heterotopic gastric mucosa (34, 35) and retroverted epiglottis (36). The importance of this study is in the use of GETS as the subjective expression of the globus severity. It can be used in primary care to identify patients for whom referral to secondary care may be appropriate (37, 38). Ali et al. (37) report that out of ten throat symptoms, globus patients most commonly complained of “Coughing to clear the throat”, “Catarrh down the throat” and “Discomfort/irritation in the throat”. Similar to our results, Deary et al. (28) showed that the commonest throat symptoms were “Feeling of something stuck in the throat”, “Discomfort/irritation in the throat” and “Want to swallow all the time”. One of the aims of our study was to investigate the relationship of the size of the thyroid with the globus symptom. For this purpose, total thyroid volume was observed in all patients. Burns and Timon (1) showed that one-third of patients with a thyroid mass complained of a globus-type symptom preoperatively. Globus symptom improved or resolved in the majority of patients within six months of surgery. For the first time, they demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in globus symptom in patients in which histologic analysis of the removed thyroid specimen showed an inflammatory response. However, resolution was independent of thyroid size. Our results would tend to support these observations, indicating that a minor proportion of patients had enlarged thyroid. Some other reports also conclude that thyroidectomy could improve globus symptoms (39-41). Belafsky et al. (30) have developed the Reflux Finding Score (RFS) as a useful tool for assessment of LPR patients. Based on their analysis, one can be 95% certain that the patient with RFS ≥7 will have LPR. In their prospective study, Patigaroo et al. (42) presented patients diagnosed as LPR cases on the basis of RFS. The most common laryngeal finding was erythema/hyperemia, followed by ventricular obliteration and posterior commissure hypertrophy. Park et al. (15) assessed the validity of RFS as a diagnostic method for LPR among globus patients. They showed that RFS had low specificity, suggesting that it may not be a valid diagnostic tool for LPR in patients with globus. Although we found no statistically significant difference between patients with RFS <7 and RFS >7, we did find that more patients had RFS >7 (57%), meaning that they were diagnosed with LPR. Book et al. (29) confirmed that 94.9% of 157 patients with LPR had globus sensation. Patigaroo et al. (42) showed that globus pharyngeus was the most common symptom present in 74% of patients with LPR.

In conclusion, based on our findings, the incidence and severity of globus pharyngeus do not definitely indicate LPR but it is more common in patients with a normal thyroid volume. Our results should be confirmed in a larger population-based study, especially with more male patients. The problem is inadequate recognition of the globus by general practitioners and the importance of specialist treatment. In further investigations, much more patients with globus pharyngeus should be included and symptoms from GETS put in correlation with thyroid pathology and LPR.

References

- 1.Burns P, Timon C. Thyroid pathology and the globus symptom: are they related? A two-year prospective trial. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:242–5. 10.1017/S0022215106002465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BE, Kim GH. Globus pharyngeus: a review of its etiology, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(20):2462–71. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowley H, O’Dwyer TP, Jones AS, Timon C. The natural history of globus pharyngeus. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1118–21. 10.1288/00005537-199510000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moloy PJ, Charter R. The globus symptom. Incidence, therapeutic response, and age and sex relationships. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:740–4. 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790590062017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. 10.1007/BF01303162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batch AJ. Globus pharyngeus (Part I). J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:152–8. 10.1017/S0022215100104384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harar RP, Kumar S, Saeed MA, Gatland DJ. Management of globus pharyngeus: review of 699 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:522–7. 10.1258/0022215041615092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purcell J. A Treatise of Vapours or Hysteric Fits. 2nd ed. London: Edward Place; 1707. pp. 72-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malcomson KG. Globus hystericus vel pharyngis (a recommaissance of proximal vagal modalities). J Laryngol Otol. 1968;82:219–30. 10.1017/S0022215100068687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill J, Stuart RC, Fung HK, Ng EK, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux, motility disorders, and psychological profiles in the etiology of globus pharyngis. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1373–7. 10.1097/00005537-199710000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chevalier JM, Brossard E, Monnier P. Globus sensation and gastroesophageal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:273–6. 10.1007/s00405-002-0544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JA, Pryde A, Piris J, et al. Pharyngoesophageal dysmotility in globus sensation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:1086–90. 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860330076021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:385–8. 10.1067/mhn.2000.109935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oridate N, Nishizawa N, Fukuda S. The diagnosis and management of globus: a perspective from Japan. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:498–502. 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328313bb69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park KH, Choi SM, Kwon SU, Yoon SW, Kim SU. Diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux among globus patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:81–5. 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1–78. 10.1002/lary.1991.101.s53.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koufman J, Sataloff RT, Toohill R. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: consensus conference report. J Voice. 1996;10:215–6. 10.1016/S0892-1997(96)80001-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokashiki R, Funato N, Suzuki M. Globus sensation and increased upper esophageal sphincter pressure with distal esophageal acid perfusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:737–41. 10.1007/s00405-009-1134-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Färkkilä MA, Ertama L, Katila H, et al. Globus pharyngis, commonly associated with esophageal motility disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:503–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corso MJ, Pursnani KG, Mohiuddin MA, et al. Globus sensation is associated with hypertensive upper esophageal sphincter but not with gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1513–7. 10.1023/A:1018862814873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puhakka HJ, Kirveskari P. Globus hystericus: globus syndrome? J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:231–4. 10.1017/S0022215100104608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batch AJ. Globus pharyngeus: (Part II) [Discussion]. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:227–30. 10.1017/S0022215100104591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JW, Song CW, Kang CD, et al. Pharyngoesophageal motility in patients with globus sensation. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2000;36:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timon C, O’Dwyer T, Cagney D, Walsh M. Globus pharyngeus: long-term follow-up and prognostic factors. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:351–4. 10.1177/000348949110000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cathcart R, Wilson JA. Lump in the throat. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:108–10. 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wareing M, Elias A, Mitchell D. Management of globus sensation by the speech therapist. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 1997;22:39–42. 10.3109/14015439709075313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Kelly SW. Globus pharyngis, personality, and psychological distress in the general population. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:570–7. 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71614-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Harris MB, MacDougall G. Globus pharyngis: development of a symptom assessment scale. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:203–13. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00104-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Book DT, Rhee JS, Toohill RJ, Smith TL. Perspectives in laryngopharyngeal reflux: an international survey. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1399–406. 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI). J Voice. 2002;16:274–7. 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawamura O, Aslam M, Rittmann T, Hofmann C, Shaker R. Physical and pH properties of gastroesophagopharyngeal refluxate: a 24-hour simultaneous ambulatory impedance and pH monitoring study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1000–10. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunn J, Block U, Ruf G, Bos I, Kunze WP, Scriba PC. Volumetric analysis of thyroid lobes by real-time ultrasound. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1981;106:1338–40. 10.1055/s-2008-1070506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maran A, Jacobson I. Cervical osteophytes presenting with pharyngeal symptoms. Laryngoscope. 1971;81:412–7. 10.1288/00005537-197103000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancaster JL, Gosh S, Sethi R, Tripathi S. Can heterotopic gastric mucosa present as globus pharyngeus? J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:575–8. 10.1017/S0022215106001307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alaani A, Jassar P, Warfield AT, et al. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the cervical oesophagus (inlet patch) and globus pharyngeus – an under-recognised association. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:885–8. 10.1017/S0022215106005524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agada FO, Coatesworth AP, Grace AR. Retroverted epiglottis presenting as a variant of globus pharyngeus. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:390–2. 10.1017/S0022215106003422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali KH, Wilson JA. What is the severity of globus sensation in individuals who have never sought health care for it? J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:865–8. 10.1017/S0022215106003380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kortequee S, Karkos PD, Atkinson H, Sethi N, et al. Management of globus pharyngeus. Int J Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:946780. 10.1155/2013/946780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall JN, McGann G, Cook JA, Taub N. A prospective controlled study of high-resolution thyroid ultrasound in patients with globus pharyngeus. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21:228–31. 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1996.tb01731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maung KH, Hayworth D, Nix PA, Atkin SL. Thyroidectomy does not cause globus pattern symptoms. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:973–5. 10.1258/002221505775010760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Consorti F, Mancuso R, Mingarelli J, Pretore E, et al. Frequency and severity of globus pharyngeus symptoms in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a pre-post short term cross-sectional study. BMC Surg. 2015;15:53. 10.1186/s12893-015-0037-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patigaroo SA, Hashmi SF, Hasan SA, Ajmal MR, Mehfooz N. Clinical manifestations and role of proton pump inhibitors in the management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(2):182–9. 10.1007/s12070-011-0253-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]