Abstract

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) degeneration is potentially involved in the pathogenesis of several retinal degenerative diseases. mTORC1 signaling is shown as a crucial regulator of many biological processes and disease progression. In this study, we aimed at investigating the role of mTORC1 signaling in RPE degeneration.

Methods: Western blots were conducted to detect mTORC1 expression pattern during RPE degeneration. Cre-loxP system was used to generate RPE-specific mTORC1 activation mice. Fundus, immunofluorescence staining, transmission electron microscopy, and targeted metabolomic analysis were conducted to determine the effects of mTORC1 activation on RPE degeneration in vivo. Electroretinography, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography, and histological experiments were conducted to determine the effects of mTORC1 activation on choroidal and retinal function in vivo.

Results: RPE-specific activation of mTORC1 led to RPE degeneration as shown by the loss of RPE-specific marker, compromised cell junction integrity, and intracellular accumulation of lipid droplets. RPE degeneration further led to abnormal choroidal and retinal function. The inhibition of mTORC1 signaling with rapamycin could partially reverse RPE degeneration. Targeted metabolomics analysis further revealed that mTORC1 activation affected the metabolism of purine, carboxylic acid, and niacin in RPE.

Conclusion: This study revealed that abnormal activation of mTORC1 signaling leads to RPE degeneration, which could provide a promising target for the treatment of RPE dysfunction-related diseases.

Keywords: RPE degeneration, mTORC1, metabolism

Introduction

RPE is a cuboidal, polarized, and pigmented epithelium situated between the retinal photoreceptors and the choriocapillaris, which forms part of the blood-retinal barrier 1. RPE absorbs light, supplies 60% of the glucose metabolized by the retina, transports ions, water and metabolic end products from the subretinal space to the blood, participates in visual cycle, phagocytizes shed photoreceptor outer segment, and secretes a variety of growth and immunosuppressive factors 1, 2.

Mutations of RPE-expressed genes lead to retinal degenerative diseases, illustrating the importance of RPE function for visual maintenance in human 3, 4. RPE degeneration also plays a key role in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is the leading cause for irreversible vision loss in the elderly population 5, 6. Thus, it is urgent to clarify the pathogenesis of RPE degeneration. Previous studies show that oxidative damage, senescence, and dysregulated RPE metabolism are involved in RPE degeneration 7-9. Despite intensive basic and clinical research, the precise mechanism of RPE degeneration is still unclear.

Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) regulates several important cellular functions, including cell growth, proliferation, migration, and metabolism 10-12. Abnormal mTORC1 activation has been implicated in several diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases and cancers 13. mTORC1 dysfunction has been detected during RPE dedifferentiation in mice 14, 15. Moreover, subcellular localization and function of mTOR is altered in the aged RPE 16. Taken together, these studies have revealed a potential link between mTORC1 signaling and RPE function. In this study, we mainly investigated whether intervention of mTORC1 signaling could affect the development of RPE degeneration. We showed that abnormal mTORC1 activation in mice RPE led to RPE degeneration, choroidal and retinal degeneration. Inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin partially rescued RPE degeneration, suggesting an important role of mTORC1 signaling in regulating RPE function.

Methods

Human primary RPE cell culture

This study was approved by the ethics committee of EYE & ENT Hospital of Fudan University. The informed consent concerning the use of the donated eyes for research was provided by the Shanghai Red Cross Eye Bank. All donors were Han Chinese. The primary RPE cells were isolated within 24 h after death from adult human donor eyes. All procedures were conducted according to the standards for eye donation for research and the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

RPE cultures were performed as previously reported 17. Briefly, after removing the anterior segment, vitreous, and retina, we rinsed the eyecups with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C. The dissociation buffer was gently removed and the eyecup was filled with DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). RPE was gently scraped from the Bruch's membrane by a double bevel spoon blade (3.0 mm). RPE was cultured in DMEM/F12 media with 10% FBS in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37 °C. Cell medium was replaced every 3 days. Primary RPE was cultured without passing for 14 days before experiments.

Mouse breeding and genotyping

All mice were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited specific-pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility (Model Animal Research Center, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) with a 12-h light/dark cycle and had ad libitum access to water and standard mouse chow diet. BEST1-Cre transgenic mice (provided by Prof Joshua L. Dunaief from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) were C57BL/6J background, and the Cre recombinase was controlled by the fragment of human BEST1 promoter (-585 to +38)18. Mice with a loxP-flanked tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1) allele (TSC1 loxP/loxP) with a mixed B6/129 background were a kind gift from Dr. Chun-Sun Dai (State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine, Institute of Toxicology, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) 19. As the BEST1-Cre transgene is expressed in the male germline 18, we generated the genotype (TSC1 loxP/loxP; +/Tg[BEST1-Cre]) (RPE-TSC1-/-) by breeding female BEST1-Cre transgenic mice with male TSC1 loxP/loxP mice (Figure S1A-D). The RPE-TSC1-/- mice served as the experimental group, whereas the TSC1 loxP/loxP littermates served as controls. Both male and female mice were used in this experiment. The gender was randomly selected in this study. Genotyping was carried out by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA isolated from mice tails. Primer sequences were listed in Table S1. All experimental and animal care procedures were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the guidelines on the ethical use of animals of Fudan University.

Immunofluorescence

Eyes were enucleated immediately after sacrifice and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Eyecups were dissected, rinsed with PBS, dehydrated in 30% sucrose for 2 h, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT; Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). The frozen sections of eyecups were cut at 10-µm thickness using a freezing microtome (Leica, Hamburg, Germany). RPE flat mounts were prepared as described previously 14 and then blocked with 5% normal goat serum (NGS)/0.1% Triton X-100/1×PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by the secondary antibodies (Table S2). Nuclei were counterstained with 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:2000, Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were captured with Lecia SP2 microscope (Leica, Hamburg, Germany).

Rapamycin administration

Three-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice and littermate controls were injected daily with rapamycin (3 mg/kg) or vehicle (4% ethanol, 5% Tween 80, and 5% polyethyleneglycol 400) (n = 15 for each group) intraperitoneally for 2 months until sacrifice.

Metabolite analysis by LC/MS-MS

Briefly, isolated RPE-choroid complexes were processed in 80% cold methanol via homogenization and metabolites were analyzed using Shimadzu LC Nexera X2 UHPLC coupled with a QTRAP 5500 LC MS/MS (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved using ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide analytic column (2.1×50 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters) with mobile phase A (water with 10 mM ammonium acetate with pH 8.9) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile/water (95/5) with 10 mM ammonium acetate with pH 8.2) (All solvents were LC-MS Optima grade from Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Chromatographic separation was completed in a total run time of 11min with a gradient as previously described 20, 21. Multiple reaction monitoring was performed for 97 transitions listed in Table S3. MultiQuant 3.0.2 software (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) was used to integrate the extracted peaks and volcano plots were used to analyze the data. Different metabolites and enriched metabolic pathways were identified by MetaboAnalyst software.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS (v19.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used for statistical analysis. For normally distributed data with equal variance, the difference was evaluated by 2-tailed Student's t-test (2‐group comparisons) or 1-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Bonferroni test (multi-group comparisons) as appropriate. For abnormally distributed data and data with unequal variances, the difference was evaluated by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (2‐group comparisons). Data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P< 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Results

mTORC1 signaling activity is altered during RPE degeneration

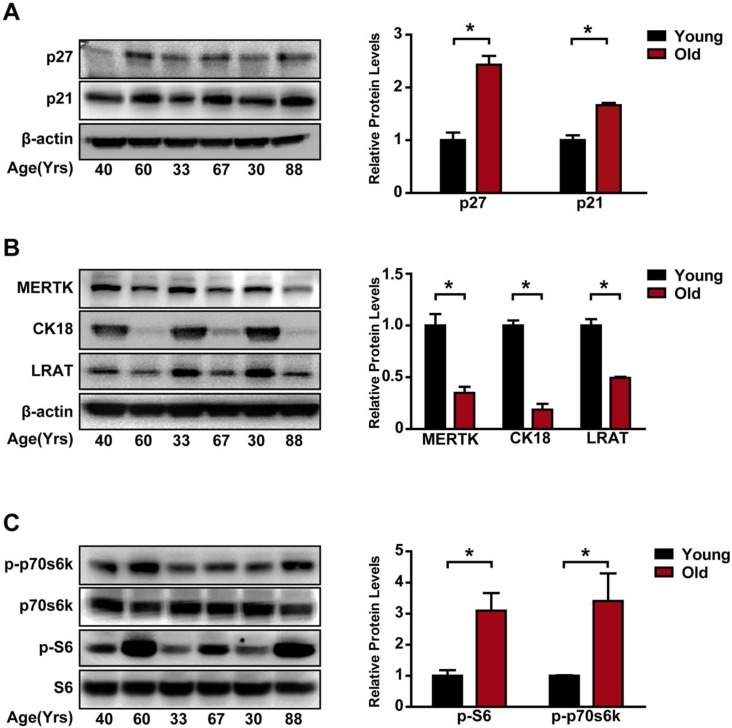

Age is often recognized as a risk factor for RPE degeneration 8. Thus, we compared the difference of mTORC1 activity in primary RPE cells from young (30 years old, 33 years old and 40 years old) and elderly (60 years old, 67 years old, and 88 years old) donors. The expression of aging makers, including p27 and p21, was up-regulated in the elderly group (Figure 1A). By contrast, the expression of RPE specific markers, including the tyrosine-protein kinase Mer (MERTK), kertain18 (CK18), and lecithin retinol acyltransferase (LRAT), was significantly down-regulated in the elderly donors compared to that of the young donors, suggesting that RPE degeneration occurred in the elderly group (Figure 1B). The 70 kDa/S6 ribosomal protein (p70s6K/S6) pathway is regulated by mTORC112. In elderly RPE, we detected increased phosphorylation levels of p70s6KThr389 and S6Ser235/236 (Figure 1C), indicating that mTORC1 activity was significantly up-regulated in the elderly donors. Taken together, these data suggest that mTORC1 activity is altered during RPE degeneration.

Figure 1.

mTORC1 activity is up-regulated in the aged, degenerating human RPE. (A) p21 and p27 expression was detected in the primary RPE isolated from young and elderly donors by Western blots. Statistical result is shown at the right panel (n = 3, *P<0.05, mean ± standard deviation). (B) RPE markers, including MERTK, CK18, and LRAT, were detected by Western blots in the primary RPE isolated from the young and elderly donors. Statistical result is on the right panel (n = 3, *P<0.05, mean ± standard deviation). (C) Phosphorylation levels of S6 Ser235/236 and p70s6K Thr389 protein were detected in the primary RPE isolated from the young and elderly donors. Statistical result is shown at the right panel (n = 3, *P<0.05, mean ± standard deviation).

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to mTORC1 signaling activation in RPE

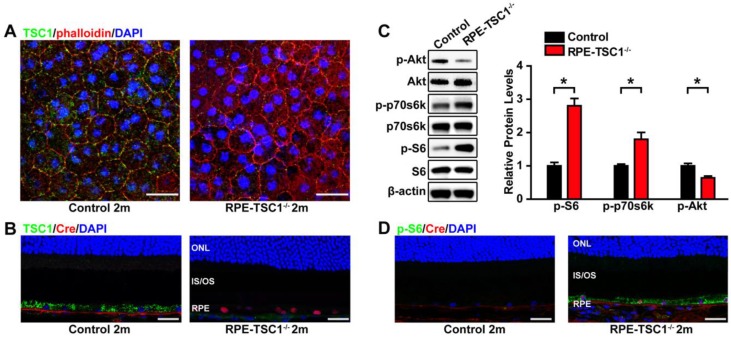

To determine the role of mTORC1 in RPE, we generated a mouse model for RPE-specific mTORC1 activation by deletion of its upstream inhibitor tuberous sclerosis complex 1(TSC1) 22. We crossed TSC1 loxP/loxP (TSC1f/f) mice with BEST1-Cre transgenic mice. TSC1 was deleted at the DNA level as expected (Figure S1D). The BEST1-Cre transgene induced ocular Cre expression postnatally in RPE, which does not cause Cre toxicity in controls 14. We did not detect any abnormity of ERG response, RPE ultrastucture, or fundus in BEST-1 Cre mice (Figure S2). No mutation of rd1 or rd8 was found in these mice (Figure S3). TSC1 knockout by BEST1 Cre-mediated recombination in RPE was also confirmed by immunofluorescence (Figure 2A-B).

Figure 2.

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to mTORC1 activation in mice RPE. (A- B) TSC1 staining of RPE flat mounts (A, Scale bar: 20 μm) and retinal sections (B, Scale bar: 25 μm) indicated the loss of TSC1 protein in the RPE of RPE-TSC1-/- mice. Phalloidin staining was used to outline cell boundaries. (C) Phosphorylated levels of AktSer473, p70s6K Thr389, and S6 Ser235/236 protein in 2-month RPE-choroid complex of RPE-TSC1-/- and control group were detected by Western blots. Statistical results are also shown (n = 3, *P<0.05 versus control, mean ± standard deviation). (D) Retinal sections from the 2-month RPE-TSC1-/- mouse and the age-matched control were stained for p-S6Ser235/236 (green) to determine the activation of mTORC1 signaling. Scale bar: 25 μm. CHO: choroid; IS: inner segment; ONL: outer nuclear layer; OS: outer segment; RPE: retinal pigment epithelium.

To determine whether TSC1 deletion led to the hyperactivation of mTORC1, we examined the phosphorylated levels of S6 and p70s6K. Compared with the controls, the phosphorylated levels of p70s6KThr389and S6Ser235/236 were significantly up-regulated in RPE-choroid complex of RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 2C). We also observed decreased Akt phosphorylation (Ser 473) in the RPE of RPE-TSC1-/- mice, which is consistent with a previous report describing the feedback inhibition by activated mTORC1 23. To determine the specific cell types in which mTORC1 was activated, we performed immunofluorescence staining and found that S6Ser235/236 level was significantly up-regulated in the RPE of RPE-TSC1-/-mice (Figure 2D). Collectively, these results suggest that RPE-TSC1-/- mice exhibit RPE-specific activation of mTORC1 signaling.

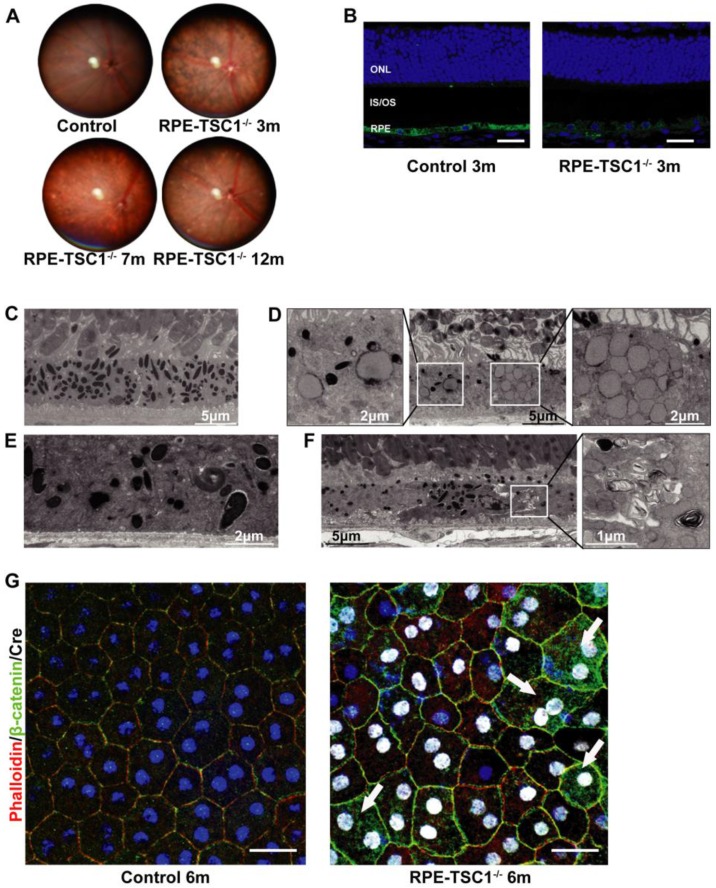

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to RPE degeneration in vivo

To reveal the phenotype of RPE-TSC1-/- mice, we performed in vivo and ex vivo analysis to characterize the morphological and molecular changes. The fundus of RPE-TSC1-/- mice showed a progressive RPE degeneration and the appearance of white spots by 7 months of age (Figure 3A). The white spots might be macroscopic manifestation of lipid buildup 14. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that the expression of RPE65, an important RPE marker, was decreased in RPE-TSC1-/- mice at 3 months of age (Figure 3B). Transmission electron microscopy of 12-month-old control RPE showed the normal monolayer structure, melanosomes distribution, and polarization (Figure 3C). Ultrastructural analysis of RPE-TSC1-/- mice at 6 months revealed intracellular accumulation of lipid droplets and abnormal melanosomes of RPE (Figure 3D). Loss of basal infoldings, a key morphological indicator of RPE polarity, was observed in 7-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 3E). Increased pigmentary changes and accumulation of unprocessed phagosomes were detected in 12-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 3F). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that TSC1-specific deletion in RPE led to the loss of regular cuboidal appearance and increase in heterogeneity of the size and shape of RPE cells (Figure 3G). β-catenin is a marker of RPE adherens junction 24. β-catenin cytoplasmic translocation was detected in a small number of Cre-expressing cells (Figure 3G, arrows). Collectively, RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 induced abnormal RPE morphology, intracellular accumulation of lipid droplets, loss of RPE marker, and abnormal RPE junction structure, suggesting that mTORC1 activation leads to RPE degeneration.

Figure 3.

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to RPE degeneration in vivo . (A) Fundus images of RPE-TSC1-/- mice at different ages are shown. (B) Immunostaining showed that RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 led to decreased RPE65 expression. Scale bar: 25 μm. (C-F) Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe the region of RPE/Bruch's membrane/choroidal junction in 12-month-old control mice (C), 6-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (D), 7-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (E), and 12-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (F). (G) Flat mounts of posterior eye from 6-month-old control and RPE-TSC1-/- mice were stained with phalloidin and β-catenin to show RPE morphological changes. Arrows represent the cytoplasmic translocation of β-catenin. Scale bar: 20 μm.

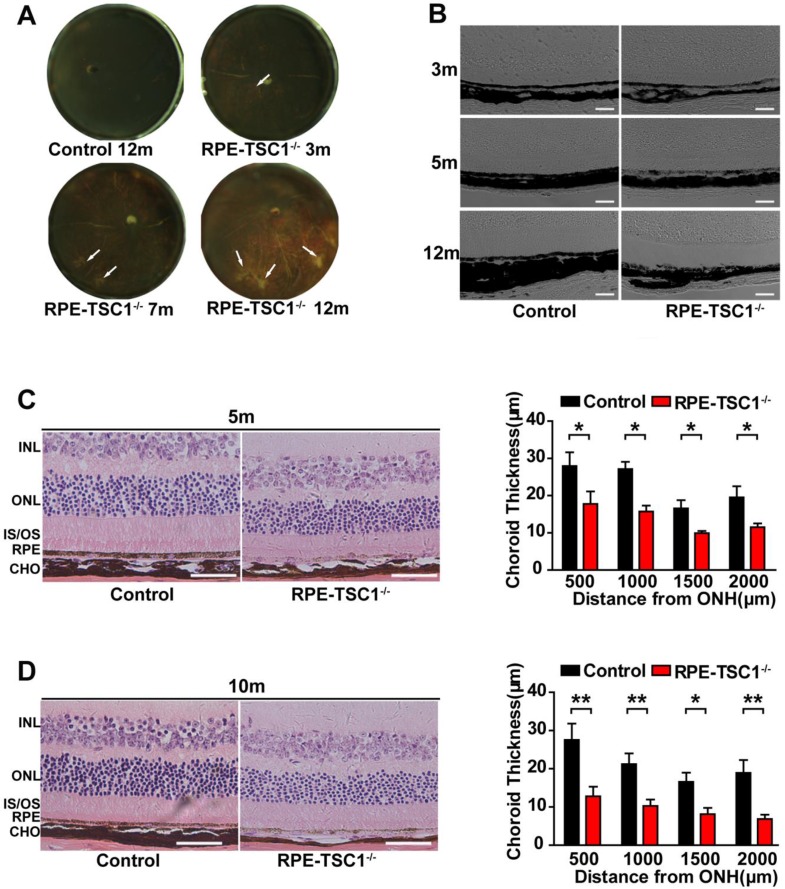

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to choroidal pathology

By the examination of posterior eyecups, the appearance of focal choroidal atrophy was detected in RPE-TSC1-/-mice as early as 3 months of age and the atrophic area increased with age (Figure 4A, arrows). DIC (Digital Image Correlation) examination (Figure 4B) and H&E staining (Figure 4C-D) of RPE-TSC1-/- mice confirmed the posterior eyecup findings of choroidal thinning and atrophy.

Figure 4.

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to choroidal pathology. (A) The eyecups of RPE/choroid from 3- to 12-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice exhibited progressive choroidal thinning (light area; white arrows). (B) The images of DIC captured from 3-to 12-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice showed abnormal melanosome distribution. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C- D) The morphology of retina/RPE choroid and sclera of 5-month-old (C) or 10-month-old (D) RPE-TSC1-/- mice and controls are shown. Scale bar: 50 μm. Choroid thickness was statistically analyzed. ONH, optic nerve head (n = 3, *P<0.05, ** P<0.01). INL: inner nuclear layer.

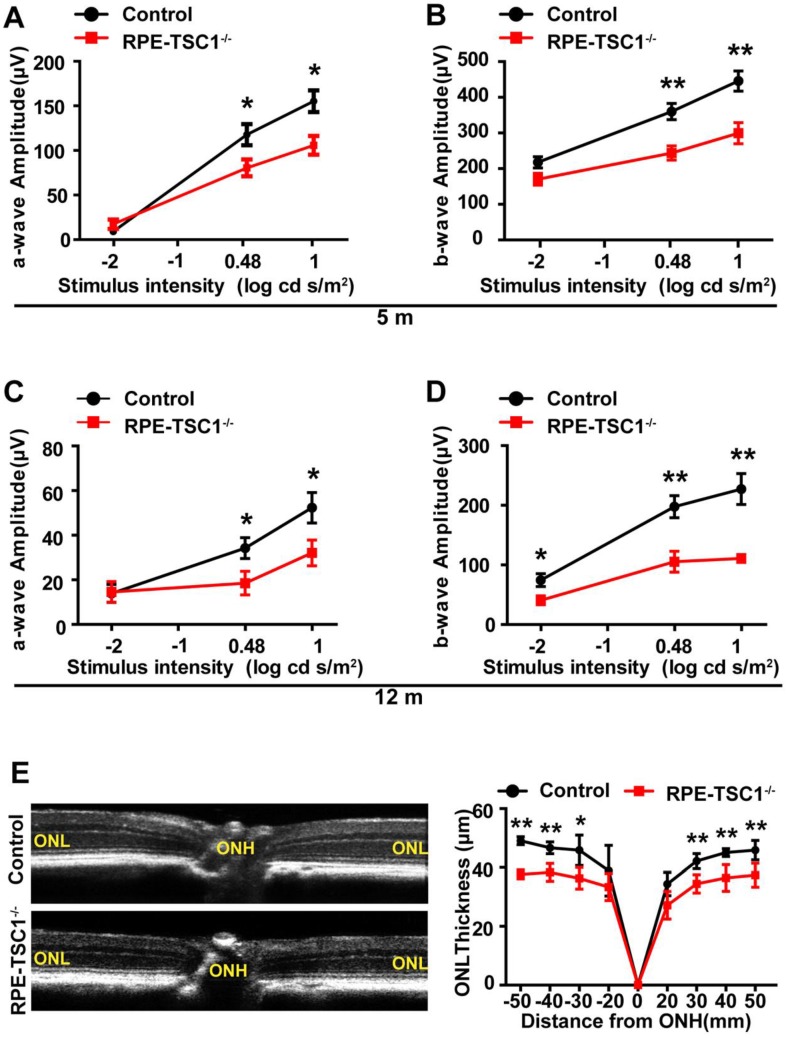

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to progressive retinal degeneration

Retinal degeneration is regarded as the consequence of RPE dysfunction 25. We recorded ERGs of RPE-TSC1-/- mice and controls at 5-month and 12-month age. Dark-adapted RPE-TSC1-/- mice had lower scotopic b-wave and a-wave amplitudes compared with the age-matched controls. At 5-month age, there was approximately 30% reduction in the scotopic b-wave amplitudes in RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 5A-B). At 12-month age, both the scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes were diminished by about 50% (Figure 5C-D). Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography examination showed that the outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was significantly decreased in RPE-TSC1-/-mice (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 leads to progressive retinal degeneration. (A-D) Average intensity-response curves of scotopic a-wave (A and C) and b-wave (B and D) amplitudes of 5-month-old and 12-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice and littermate controls (n = 5, *P<0.05, ** P<0.01). (E) Quantification of the thickness of ONL from SD-OCT images of RPE-TSC1-/- mice and littermate controls at 5 months. ONH, optic nerve head (n = 5,*P<0.05, ** P<0.01 versus control).

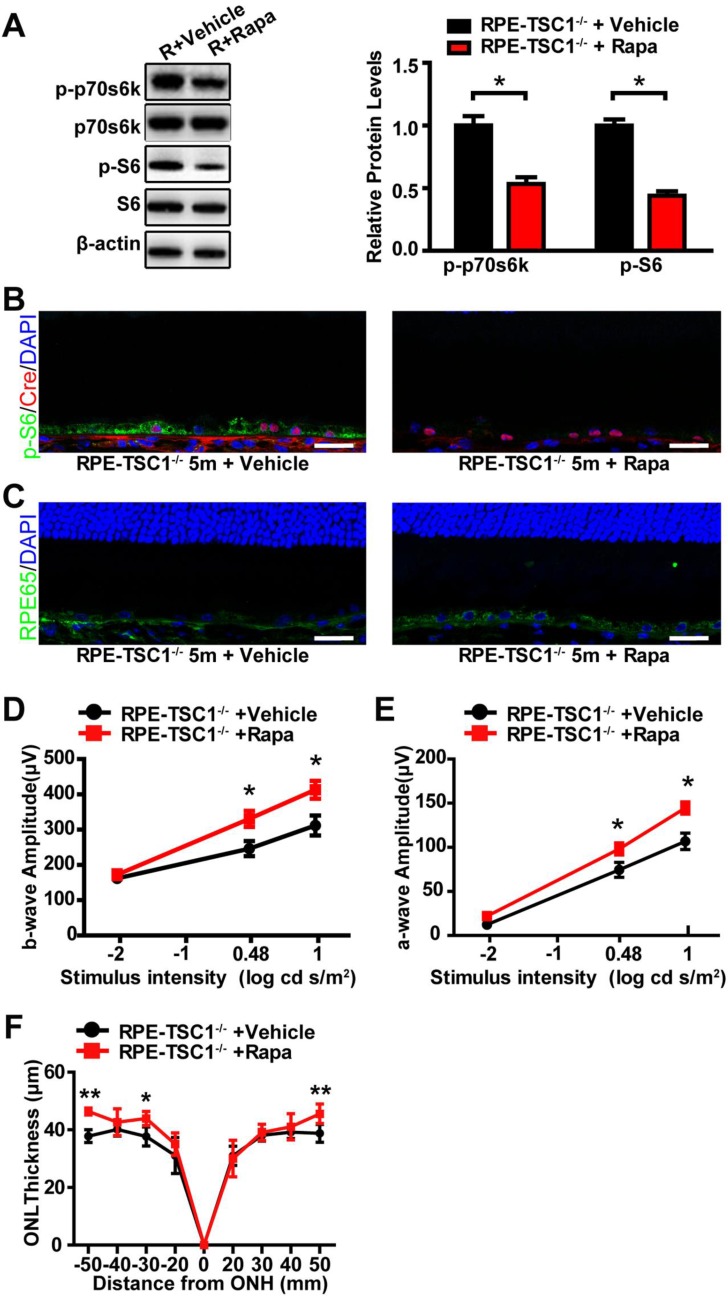

Rapamycin administration partially reverses RPE degeneration

To investigate whether inhibition of mTORC1 signaling could rescue RPE dysfunction, we administrated RPE-TSC1-/-mice and littermate controls with rapamycin (rapa), a specific inhibitor of mTORC1 signaling 26. We found that rapamycin treatment decreased the phosphorylated level of S6Ser235/236 and p70s6K Thr389 in RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 6A). Decreased S6Ser235/236 phosphorylated level was also detected in Cre-expressing RPE (Figure 6B). Increased RPE65 reactivity level was detected in the retinal sections of rapamycin-injected RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 6C). Moreover, RPE-TSC1-/-mice showed improved retinal scotopic ERG response and increased ONL thickness after rapamycin treatment (Figure 6D-F). Thus, rapamycin administration could partially reverse RPE degeneration.

Figure 6.

Rapamycin administration partially reverses RPE degeneration. (A) Western blots showed decreased phosphorylated levels of p70s6KThr389 and S6Ser235/236 in RPE-choroid complex of 5-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice after rapamycin injection (R: RPE-TSC1-/-). (B) Immunostaining for p-S6Ser235/236 (green) and Cre (red) showed decreased p-S6Ser235/236 expression after rapamycin administration. rapa, rapamycin; veh, vehicle; scale bar: 25 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence staining showed increased RPE65 (green) after injection of rapamycin in RPE-TSC1-/- mice (right); scale bar: 25 μm. (D- E) Electroretinography revealed increased scotopic b-wave and a-wave responses in 5-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice after rapamycin administration compared with vehicle-treated RPE-TSC1-/- mice (n = 5, *P<0.05, mean ± standard deviation). (F) SD-OCT analysis revealed increased ONL thickness in 5-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice after rapamycin administration compared with vehicle-treated RPE-TSC1-/- mice (n = 5, *P<0.05, ** P<0.01, mean ± standard deviation).

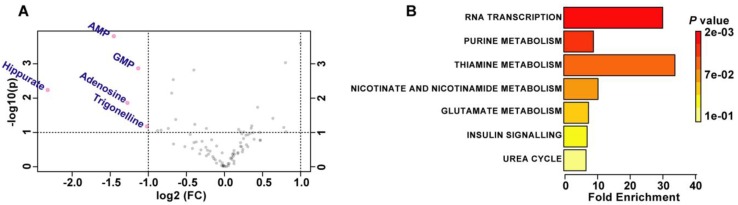

TSC1 deletion leads to abnormal metabolism in RPE

Activation of mTORC1 signaling is correlated with abnormal nutrient uptake and metabolism 32. We speculated that RPE degeneration in RPE-TSC1-/- mice may be caused by dysregulated RPE metabolism. We used the targeted metabolomics to analyze 97 metabolites which were essential for central carbon metabolism in the RPE samples (Table S3). Volcano plot (5 controls and 5 RPE-TSC1-/-mice) analysis revealed the substantial decrease of purine metabolites (AMP, GMP, and Adenosine), carboxylic acid (Hippurate), and the product of niacin metabolism (Trigonellinein) in RPE of 6-month-old RPE-TSC1-/- mice (Figure 7A and Table 1). These metabolites were assessed for the enriched metabolic pathways using the MetaboAnalyst software and 7 potentially enriched pathways were identified. Of them, RNA transcription, purine metabolism, and thiamine metabolism were ranked as the top 3 enriched pathways (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

TSC1 deletion leads to abnormal metabolism in RPE. (A) Important features selected by the volcano plot with fold change threshold (X) 2 and t-tests threshold (Y) 0.1. The red circles represent features above the threshold. Both fold changes and P values were log transformed. (B) Overview of metabolite sets enrichment.

Table 1.

Change of representative metabolites between RPE-TSC1-/- and controls

| Peaks (mz/rt) | FC | log2 (FC) | raw.pval | - log 10(p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | 0.36534 | -1.4527 | 0.00015644 | 3.8057 |

| GMP | 0.45604 | -1.1328 | 0.0013538 | 2.8684 |

| Hippurate | 0.20015 | -2.2309 | 0.0057935 | 2.2371 |

| Adenosin | 0.41343 | -1.2743 | 0.013794 | 1.8603 |

| Trigonelline | 0.49413 | -1.017 | 0.066775 | 1.1754 |

FC: fold change; p: P value; pval: P value.

Discussion

RPE dysfunction is a primary event in the several retinal degeneration diseases. In this study, we show that the aged human RPE exhibit increased activation of mTORC1 signaling. RPE-specific activation of mTORC1 in mice leads to RPE dysfunction which is characterized by the loss of RPE marker protein, compromised cell junction integrity, and intracellular accumulation of lipid droplets. Inhibition of mTORC1 signaling with rapamycin can partially reverse RPE degeneration. This study suggests that abnormal activation of mTORC1 leads to RPE degeneration.

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly conserved kinase that belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related protein kinases (PIKK) family. mTOR participates in two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 regulates energy, nutrients, stress, and growth factors; in response to these stimuli, it drives the growth of cells, organs, and whole organisms 27. mTORC1 plays important roles in the development of degenerative diseases. Various neurodegenerative disorders exhibit dysregulated mTOR signaling, which potentially could be restored by rapamycin 28. Previous studies have shown that mTOR signaling network is involved in cell senescence 8. Inhibition of mTOR confers protection against a growing list of age-related pathologies. In addition to inhibiting mTORC1, TSC1 may affect other signaling pathways. Loss of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to activated GSK3β signaling and decreased melanogenesis-associated transcription factor expression, which causes pigmentation loss via mTORC1 activation 29. This is consistent with the RPE hypopigmentation in RPE-TSC1-/- mice. Loss of TSC1 or TSC2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts leads to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress 30. TSC1 prevents dendritic cells from undergoing apoptosis via repressing mTORC1 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathways independently 31. ROS generation and ER stress have been associated with RPE degeneration 32. Thus, it is not surprising that TSC1/mTORC1 network is involved in the regulation of RPE degeneration.

RPE plays an important role in maintaining the viability of retina 33. RPE-specific deletion of TSC1 results in RPE degeneration and subsequent retinal degeneration as shown by decreased amplitudes of rod-driven ERG responses in RPE-TSC1-/- mice, which is consistent with the clinical features of AMD patients 34. In addition to electrophysiological changes, reduced ONL thickness is shown in RPE-TSC1-/- mice. Photoreceptor abnormalities are likely the secondary response to RPE dysfunction, consistent with other genetic models of RPE-specific dysfunction 35-37. The thinning and atrophy of choroid is also shown in RPE-TSC1-/- mice. Consistently, focal choroidal atrophy exists in the older subjects with posterior pole abnormalities and might also be related to the typical AMD 38, 39.

The mTORC1 pathway is an important regulator of metabolism 40. Abnormal RPE metabolism plays important roles in the pathogenesis of RPE degeneration 41, 42. The metabonomics analysis shows that TSC1 knockout in RPE results in decreased metabolites (Figure 7). Purine metabolites are synthesized by the pentose phosphate pathway, which is regulated by mTOR signaling 43. Purines are the basic building blocks for RNA, DNA and ATP 44. The dysfunction of ATP production in RPE could initiate RPE degeneration 14. Glycine is involved in both purine synthesis and hippurate formation. A gene in glycine metabolism has been implicated in retinal degeneration 45. Trigonelline is involved in NAD metabolism. Mutations of genes in NAD metabolism, such as nicotinamide nucleotide adenylyltransferase1 (NMNAT1) and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), have been found to be associated with retinal degeneration 46, 47. Taken together, mTORC1 signaling activation leads to abnormal metabolism in RPE. Further studies are still required to elucidate the mechanism of dysregulated metabolites during RPE degeneration and evaluate their potential for the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of retinal degenerative diseases.

This study provides important evidence for the role of mTORC1 signaling in RPE degeneration. We, thus, propose a candidacy of mTORC1 signaling as a potential therapeutic target for treating RPE dysfunction-related diseases. Current studies have revealed that the administration of rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTORC1 signaling, could partially reverse RPE degeneration in mice. Constituents of mTOR signaling pathway may provide novel therapeutic targets to enhance the efficacy for treating retinal degenerative diseases.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study shows that mTORC1 signaling is activated in the elderly human RPE. Excessive activation of mTORC1 in mice leads to retinal degeneration features, including RPE degeneration, abnormal RPE metabolism, and degeneration of retina and choroid. Administration of rapamycin partially reverses RPE degeneration. This study reveals that mTORC1 activation is potentially involved in RPE degeneration.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We thank all donors for their donations, and Professor Joshua L. Dunaief from University of Pennsylvania for his technical support. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81525006, 81670864 and 81730025 to C.Z); Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders (2017BR013 to C.Z); National Institutes of Health Grant (EY026030 to J.D, EY026030 and EY025790 to D.V). The funders have no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- CHO

choroid

- CK18

kertain18

- DIC

Digital Image Correlation

- ERG

Electroretinograph

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- LRAT

lecithin retinol acyltransferase

- IS

inner segment

- MERTK

tyrosine-protein kinase Mer

- mTORC1

Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- ONH

optic nerve head

- ONL

outer nuclear layer

- OS

outer segment

- Rapa

rapamycin

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- SD

standard deviation

- SD-OCT

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography

- TSC1

tuberous sclerosis complex 1.

References

- 1.Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:845–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurihara T, Westenskow PD, Bravo S, Aguilar E, Friedlander M. Targeted deletion of Vegfa in adult mice induces vision loss. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4213–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI65157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strick DJ, Vollrath D. Focus on molecules: MERTK. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:786–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson DA, Gal A. Vitamin A metabolism in the retinal pigment epithelium: genes, mutations, and diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:683–703. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2012;379:1728–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta S, Cano M, Ebrahimi K, Wang L, Handa JT. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;60:201–18. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Wang J, Cai J, Sternberg P. Altered mTOR signaling in senescent retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5314–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jun S, Datta S, Wang L, Pegany R, Cano M, Handa JT. The impact of lipids, lipid oxidation, and inflammation on AMD, and the potential role of miRNAs on lipid metabolism in the RPE. Exp Eye Res; 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antikainen H, Driscoll M, Haspel G, Dobrowolski R. TOR-mediated regulation of metabolism in aging. Aging Cell. 2017;16:1219–33. doi: 10.1111/acel.12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao C, Yasumura D, Li X, Matthes M, Lloyd M, Nielsen G. et al. mTOR-mediated dedifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium initiates photoreceptor degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:369–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI44303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saika S, Kono-Saika S, Tanaka T, Yamanaka O, Ohnishi Y, Sato M. et al. Smad3 is required for dedifferentiation of retinal pigment epithelium following retinal detachment in mice. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1245–58. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu B, Xu P, Zhao Z, Cai J, Sternberg P, Chen Y. Subcellular distribution and activity of mechanistic target of rapamycin in aged retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:8638–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonoda S, Spee C, Barron E, Ryan SJ, Kannan R, Hinton DR. A protocol for the culture and differentiation of highly polarized human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:662–73. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iacovelli J, Zhao C, Wolkow N, Veldman P, Gollomp K, Ojha P. et al. Generation of Cre transgenic mice with postnatal RPE-specific ocular expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1378–83. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang L, Xu L, Mao J, Li J, Fang L, Zhou Y. et al. Rheb/mTORC1 signaling promotes kidney fibroblast activation and fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1114–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du J, Linton JD, Hurley JB. Probing Metabolism in the Intact Retina Using Stable Isotope Tracers. Methods Enzymol. 2015;561:149–70. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu S, Yam M, Wang Y, Linton JD, Grenell A, Hurley JB. et al. Impact of euthanasia, dissection and postmortem delay on metabolic profile in mouse retina and RPE/choroid. Exp Eye Res. 2018;174:113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun S, Chen S, Liu F, Wu H, McHugh J, Bergin IL. et al. Constitutive Activation of mTORC1 in Endothelial Cells Leads to the Development and Progression of Lymphangiosarcoma through VEGF Autocrine Signaling. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:758–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun S, Chen S, Liu F, Wu H, McHugh J, Bergin IL. et al. Constitutive Activation of mTORC1 in Endothelial Cells Leads to the Development and Progression of Lymphangiosarcoma through VEGF Autocrine Signaling. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:758–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCrea PD, Maher MT, Gottardi CJ. Nuclear signaling from cadherin adhesion complexes. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;112:129–96. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurihara T, Westenskow PD, Gantner ML, Usui Y, Schultz A, Bravo S, Hypoxia-induced metabolic stress in retinal pigment epithelial cells is sufficient to induce photoreceptor degeneration. Elife; 2016. p. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roohi A, Hojjat-Farsangi M. Recent advances in targeting mTOR signaling pathway using small molecule inhibitors. J Drug Target; 2016. pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M, Vila M. Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:437–52. doi: 10.1038/nrn3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao J, Tyburczy ME, Moss J, Darling TN, Widlund HR, Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis complex inactivation disrupts melanogenesis via mTORC1 activation. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:349–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI84262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozcan U, Ozcan L, Yilmaz E, Duvel K, Sahin M, Manning BD. et al. Loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex tumor suppressors triggers the unfolded protein response to regulate insulin signaling and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2008;29:541–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y, Li W, Yu G, Yu J, Han L, Xue T. et al. Tsc1 expression by dendritic cells is required to preserve T-cell homeostasis and response. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(e):2553. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minasyan L, Sreekumar PG, Hinton DR, Kannan R. Protective Mechanisms of the Mitochondrial-Derived Peptide Humanin in Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in RPE Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1675230. doi: 10.1155/2017/1675230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhutto I, Lutty G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch's membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:295–317. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feigl B, Brown B, Lovie-Kitchin J, Swann P. Cone- and rod-mediated multifocal electroretinogram in early age-related maculopathy. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:431–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramkumar HL, Zhang J, Chan CC. Retinal ultrastructure of murine models of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:169–90. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machalinska A, Lubinski W, Klos P, Kawa M, Baumert B, Penkala K. et al. Sodium iodate selectively injuries the posterior pole of the retina in a dose-dependent manner: morphological and electrophysiological study. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:1819–27. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao J, Jia L, Khan N, Lin C, Mitter SK, Boulton ME. et al. Deletion of autophagy inducer RB1CC1 results in degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium. Autophagy. 2015;11:939–53. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1041699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spaide RF. Age-related choroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:801–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jonas JB, Forster TM, Steinmetz P, Schlichtenbrede FC, Harder BC. Choroidal thickness in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2014;34:1149–55. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Csibi A, Fendt SM, Li C, Poulogiannis G, Choo AY, Chapski DJ. et al. The mTORC1 pathway stimulates glutamine metabolism and cell proliferation by repressing SIRT4. Cell. 2013;153:840–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakkaraju A, Finnemann SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The lipofuscin fluorophore A2E perturbs cholesterol metabolism in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11026–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702504104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu P, Herrmann R, Bednar A, Saloupis P, Dwyer MA, Yang P. et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor deficiency causes dysregulated cellular matrix metabolism and age-related macular degeneration-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4069–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307574110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Y, Gu X, Zhang E, Park MA, Pereira AM, Wang S. et al. Estradiol promotes pentose phosphate pathway addiction and cell survival via reactivation of Akt in mTORC1 hyperactive cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(e):1231. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kondo M, Yamaoka T, Honda S, Miwa Y, Katashima R, Moritani M. et al. The rate of cell growth is regulated by purine biosynthesis via ATP production and G(1) to S phase transition. J Biochem. 2000;128:57–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scerri TS, Quaglieri A, Cai C, Zernant J, Matsunami N, Baird L. et al. Genome-wide analyses identify common variants associated with macular telangiectasia type 2. Nat Genet. 2017;49:559–67. doi: 10.1038/ng.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin JB, Kubota S, Ban N, Yoshida M, Santeford A, Sene A. et al. NAMPT-Mediated NAD(+) Biosynthesis Is Essential for Vision In Mice. Cell Rep. 2016;17:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koenekoop RK, Wang H, Majewski J, Wang X, Lopez I, Ren H. et al. Mutations in NMNAT1 cause Leber congenital amaurosis and identify a new disease pathway for retinal degeneration. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1035–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.