Background

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychosocial treatment that aims to help individuals reevaluate their appraisals of their experiences that can affect their level of distress and problematic behavior. CBT is now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as an add-on treatment for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Other psychosocial therapies that are often less expensive are also available as an add-on treatment for people with schizophrenia. This review is also part of a family of Cochrane Reviews on CBT for people with schizophrenia.

Objectives

To assess the effects of CBT compared with other psychosocial therapies as add-on treatments for people with schizophrenia.

Search Methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study Based Register of Trials (latest March 6, 2017). This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings, with no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Selection Criteria

We selected randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving people with schizophrenia who were randomly allocated to receive, in addition to their standard care, either CBT or any other psychosocial therapy. Outcomes of interest included relapse, global state, mental state, adverse events, social functioning, quality of life, and satisfaction with treatment. We included trials meeting our inclusion criteria and reporting useable data.

Data Collection and Analysis

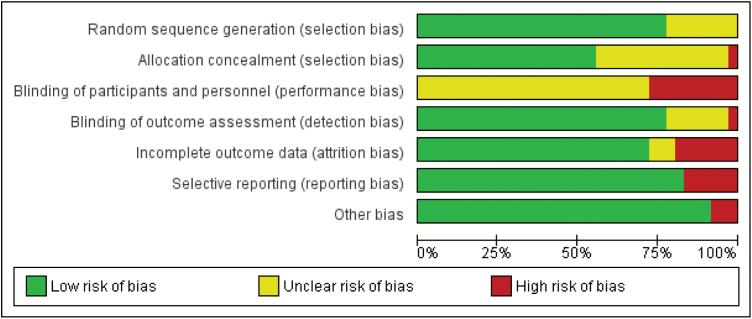

We reliably screened references and selected trials. Review authors, working independently, assessed trials for methodological quality and extracted data from included studies. We analyzed dichotomous data on an intention-to-treat basis and continuous data with 60% completion rate. Where possible, for binary data we calculated risk ratio (RR), for continuous data we calculated mean difference (MD), all with 95% CIs. We used a fixed-effect model for analyses unless there was unexplained high heterogeneity. We assessed risk of bias for the included studies (see figure 1) and used the GRADE approach to produce a “Summary of findings” table for our main outcomes of interest.

Fig. 1.

Risk of bias’ summary: review authors’ judgments about each “risk of bias” item for each included study.

Main Results

The review now includes 36 trials with 3542 participants, comparing CBT with a range of other psychosocial therapies that we classified as either active (A) (n = 14) or nonactive (NA) (n = 14) and are presented in table 1. Trials were often small and at high or unclear risk of bias. When CBT was compared with other psychosocial therapies, no difference in long-term relapse was observed (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.29; participants = 375; studies = 5, low-quality evidence). Clinically important change in global state data were not available but data for rehospitalization were reported. Results showed no clear difference in long-term rehospitalization (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.14; participants = 943; studies = 8, low-quality evidence) nor in long-term mental state (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.01; participants = 249; studies = 4, low-quality evidence). No long-term differences were observed for death (RR 1.57, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.98; participants = 627; studies = 6, low-quality evidence). Only average endpoint scale scores were available for social functioning and quality of life. Social functioning scores were similar between groups (long-term Social Functioning Scale [SFS]: MD 8.80, 95% CI −4.07 to 21.67; participants = 65; studies = 1, very low-quality evidence), and quality of life scores were also similar (medium-term Modular System for Quality of Life [MSQOL]: MD −4.50, 95% CI −15.66 to 6.66; participants = 64; studies = 1, very low-quality evidence). There was a modest but clear difference favoring CBT for satisfaction with treatment—measured as leaving the study early (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99; participants = 2392; studies = 26, low-quality evidence).

Summary of Findings Table 1.

CBT Compared to all Other Psychological Therapies for Schizophrenia

| CBT Compared to “Other Psychosocial Therapies” for People With Schizophrenia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or Population: People With Schizophrenia Setting: Inpatients and Outpatients Intervention: CBT + Standard Care Comparison: Other Psychological Therapies + Standard Care |

||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated Absolute Effectsa (95% CI) | Relative Effect (95% CI) | No. of Participants (Studies) | Quality of the Evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk With All Other Psychological Therapies | Risk With CBT | |||||

| Global state: relapse follow-up: range 8 weeks to 12 months | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.85 to 1.29) | 375 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 463 per 1000 | 486 per 1000 (393 to 597) | |||||

| Global state: rehospitalizationa follow-up: range 70 days to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.82 to 1.14) | 943 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | Data for pre-defined outcome “clinically important change” not reported. | |

| 375 per 1000 | 360 per 1000 (307 to 427) | |||||

| Mental state: General—clinically important change (no improvement) follow-up: range 12 months to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) | 249 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 636 per 1000 | 522 per 1000 (426 to 643) | |||||

| Adverse effect/event: death—any cause follow-up: range 70 days to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.57 (0.62 to 3.98) | 627 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWd,e | ||

| 16 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (10 to 64) | |||||

| Functioning—average scores (Social Functioning Scale, high = good) follow-up: mean 12 monthsa | The mean functioning— average scores (Social Functioning Scale, high = good, long-term) was 128.5 | MD 8.80 higher (4.07 lower to 21.67 higher) | - | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWc,f,g | Data for pre-defined outcome “clinically important change” not reported. |

| Quality of life: average scores (MSQOL, high = good, medium term) follow-up: mean 6 monthsa | The mean quality of life: average scores (MSQOL, high = good, medium-term) was 60.9 | MD 4.50 lower (15.66 lower to 6.66 higher) | - | 64 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWc,g,h | Data for pre-defined outcome “clinically important change” not reported. |

| Satisfaction with treatment—leaving the study early for any reason | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.75 to 0.99) | 2392 (26 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,j | ||

| 247 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 (192 to 256) |

Note: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; MSQOL, Modular System for Quality of Life; MD, mean difference; RR, Risk ratio; GRADE, Working Group grades of evidence; High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect; Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different; Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

aThe risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

bDowngraded by 1 level due to risk of bias: some studies had unclear or high risk of bias with blinding of participants and outcome assessments, as well as attrition issues.

cDowngraded by 1 level due to imprecision: small sample size and wide CI.

dDowngraded by 1 level due to risk of bias: majority of the included studies had unclear risk of blinding of participants and outcome assessments.

eDowngraded by 1 level due to imprecision: small event rate and wide CI around effect estimate.

fDowngraded by 1 level due to risk of bias: high risk of detection bias due to unblinded assessment.

gDowngraded by 1 level due to indirectness: scores from scale were employed as a surrogate index of the intended outcome.

hDowngraded by 1 level due to risk of bias: high risk of allocation concealment bias, and unclear risk around blinding.

iDowngraded by 1 level due to imprecision: small sample size and wide CI which included appreciable benefit and no effect.

jDowngraded 1 level due to indirectness: leaving the study early used to predict satisfaction with treatment.

Authors’ Conclusions

Evidence based on data from RCTs indicate there is no clear and convincing advantage for CBT over other—and sometimes much less sophisticated and expensive—psychosocial therapies for people with schizophrenia. It should be noted that although much research has been carried out in this area, the quality of evidence available is mostly low or of very low quality. Good quality research is needed before firm conclusions can be made. Full details are published in the Cochrane Review.1

Reference

- 1. Jones C, Hacker D, Meaden A, et al. . Cognitive behavioral therapy plus standard care versus standard care plus other psychosocial treatments for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD008712. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]