Abstract

The field of prevention has established the potential to promote child adjustment across a wide array of outcomes. However, when evidence-based prevention programs have been delivered at scale in community settings, declines in implementation and outcomes have resulted. Maintaining high quality implementation is a critical challenge for the field. We describe steps towards the development of a practical system to monitor and support the high-quality implementation of evidence-based prevention programs in community settings. Research on the implementation of an evidence-based parenting program for divorcing families called the “New Beginnings Program” serves as an illustration of the promise of such a system. As a first step, we describe a multidimensional theoretical model of implementation that links aspects of program delivery with improvements in participant outcomes. We then describe research on the measurement of each of these implementation dimensions and test their relations to intended program outcomes. As a third step, we develop approaches to the assessment of these implementation constructs that are feasible to use in community settings and to establish their reliability and validity. We focus on the application of machine learning algorithms and web-based data collection systems to assess implementation and provide support for high quality delivery and positive outcomes. Examples are presented to demonstrate that valid and reliable measures can be collected using these methods. Finally, we envision how these measures can be used to develop an unobtrusive system to monitor implementation and provide feedback and support in real time to maintain high quality implementation and program outcomes.

Keywords: Implementation, Measurement, Evidence-based programs, Parenting, Pragmatic measures, Technology

Introduction

Evidence-based programs (EBPs), particularly those targeting parenting, have demonstrated the ability to prevent or reduce mental health and related problems for children (NRC/IOM, 2009). A narrative review of 46 randomized trials found that these programs had positive impact on a wide range of behavioral health problems and developmental competencies that lasted up to 20 years after program delivery (Sandler, Schoenfelder, Wolchik, & MacKinnon, 2011). However, the potential public health impact of these programs is a function of how well they are implemented when delivered at scale in community settings. Pragmatic measures of implementation, which are both valid and feasible for use in community settings, are needed to maintain program effects (Glasgow & Riley, 2013). This article describes an implementation monitoring system that was developed for a randomized effectiveness trial, the challenges with collecting these data, and future directions for the development of technology to create a pragmatic system that communities can use to monitor their implementation of EBPs.

Defining Terms

Multiple dimensions of implementation have been linked with program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Implementation science is a relatively new, interdisciplinary field, still in the process of determining which dimensions are important and how to define them (Rabin et al., 2012). As such, it is important to define terms and areas of focus. We follow Durlak and DuPre’s (2008) taxonomy in which implementation is a higher order category that subsumes lower order dimensions like fidelity (i.e., the quantity of prescribed curriculum delivered, sometimes referred to as adherence) and quality (i.e., skill in presenting material and connecting with participants, sometimes referred to as competence). Out of the eight domains identified by Durlak and DuPre, we focus on fidelity, quality, and responsiveness because these reflect the interactions that occur within the delivery of the program, and are the most proximal influences on participant outcomes (Berkel, Mauricio, Schoenfelder, & Sandler, 2011). These dimensions are also at high risk of decline when programs are translated from highly controlled efficacy trials to community settings, which may explain the observed drop off in participant outcomes when programs go to scale (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013; Schoenwald et al., 2008).

Achieving public health impact depends on monitoring and providing timely feedback to the delivery system to course-correct as necessary. Traditional methods of assessing implementation have typically either emphasized validity (e.g., independent observations) or feasibility (e.g., self-report), but not both (Schoenwald et al., 2011). Because community agencies lack the time and expertise to use validated approaches, less burdensome, yet valid methods are needed. This article focuses on a trial of the effectiveness of the “New Beginnings Program” (NBP; Sandler et al., 2016; Sandler et al., 2018) as an exemplar to describe how one might use technology to redesign a theory-based, comprehensive implementation monitoring and feedback system developed for research to be used in scale-up. We will first briefly describe the NBP effectiveness trial, the approach used to assess implementation within the trial, and initial results of our ongoing studies to validate the measures. Because of the high costs of collecting these data, we have initiated several projects that will lead towards development of a valid and pragmatic system. We describe how these methods may be used to support ongoing monitoring and quality improvement when programs go to scale.

NBP Effectiveness and Implementation Studies

New Beginnings Program: Translation from efficacy to effectiveness in community delivery settings.

NBP is a manualized, group-format program that targets parenting skills to improve child adjustment following parental divorce (Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, & Winslow, 2007). Each session teaches specific parenting skills related to developing positive parent-child relationships, communication, positive discipline, and shielding children from interparental conflict. Facilitators coach parents on the use of skills in each session and parents are given homework to practice the skills with their children. Home practice is theorized to be the active ingredient leading to change in divorcing families. NBP has been tested in two efficacy trials conducted in the context of a university-based research center (Wolchik et al., 2000). Variability in facilitators’ fidelity to the curriculum in the efficacy trials was low because the program developer selected the facilitators who were then intensively trained and supervised. The long-term efficacy of NBP has been demonstrated in terms of improvements in parenting, reduced rates of diagnosable levels of internalizing disorders and substance abuse (e.g., Wolchik et al., 2013), and reductions in contact with the criminal justice system and mental health services fifteen years after exposure to the program (Herman et al., 2015).

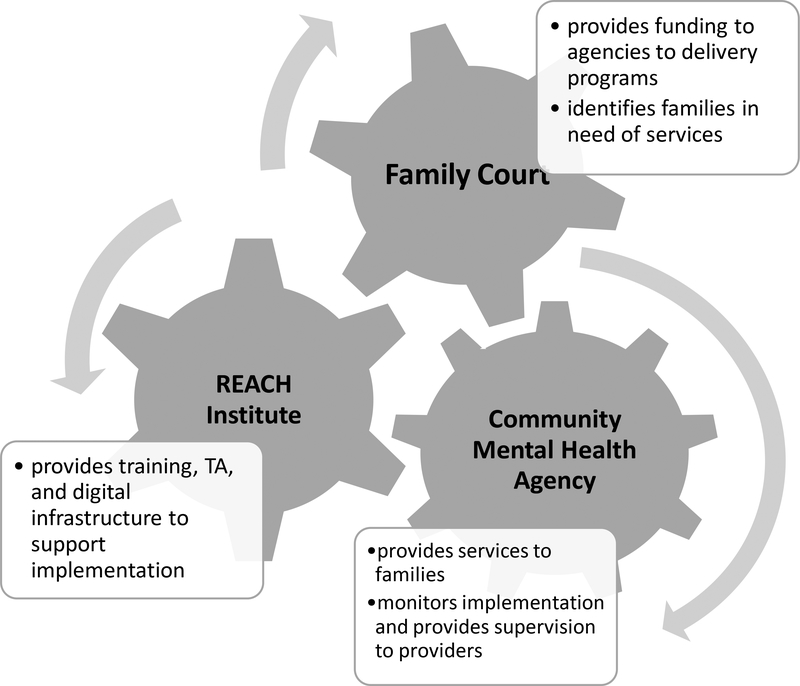

Based on positive results of the efficacy trials, we developed a partnership (see Figure 1) with four county-level family courts to conduct an effectiveness trial of NBP (Sandler et al., 2016; Wolchik et al., 2016). From a public health perspective, the courts are an ideal collaborating agency because they have access to the full population of divorcing and separating parents. The collaboration meets the interests of the courts because it is consistent with their move from a strict, adversarial system to one that facilitates less contentious divorces and mitigates the negative impact on children. Further, the program teaches skills to reduce conflict and may have an impact on relitigation, which is costly to the courts. Because they do not have the infrastructure to deliver a 10-session parenting program, community mental health agencies represented a third partner, selected through the courts’ standard bidding process. Our role as program developers and implementation researchers in this partnership was to train and supervise facilitators within these organizations to implement the program with high levels of fidelity and quality.

Figure 1.

Partnership to Promote Sustainable Implementation of a Parenting Program for Divorcing Families

A comprehensive approach to assessing implementation.

We developed a multicomponent, multi-rater implementation data collection system to assess implementation of NBP in the trial (see Table 1). Measures were selected and developed in accordance with a theoretical cascade model (see Figure 2) which highlights two overarching domains of implementation – facilitator delivery and participant responsiveness (Berkel et al., 2017; Berkel et al., 2011). Two aspects of facilitator delivery are most salient: fidelity and quality. Following Durlak and DuPre (2008), fidelity is operationalized as the quantity of program content delivered. Quality is operationalized as how well facilitators deliver the material, particularly with respect to strategies to engage participants, present the material clearly, and provide constructive feedback. The participant responsiveness side of the model includes indicators of participant engagement, such as attendance, active involvement in sessions, and practice of program skills with children between sessions. Substantial evidence links each of these dimensions with targeted program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

Table 1.

Implementation Measures

| Dimension | Rater | # of Items | Collected based on: | Scale | Example | Mean (SD) | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitator Delivery | |||||||

| Fidelity (%) | IO | 1692 | All 74 activities | No/ Partially/ Yes | Remind parents that Family Fun Time is a very important new tradition for their families | 64% (11%) | -- |

| F | 592 | 29 activities (all 9 Home Practice Review Activities; 10 Didactic Presentations; 10 Skills Practice Activities) | 93% (6%) | -- | |||

| S | 158 | 10 activities (1 per session) for each facilitator’s first cohort of delivery, and ongoing as needed | 88% (9%) | -- | |||

| Quality | |||||||

| -Positive Engagement | IO | 8 | All 74 activities | 1–5 | Reinforce parents for sharing | 3.5 (0.4) | .93 |

| F | 10 activities (1 per session) | 3.8 (0.6) | .95 | ||||

| S | 10 activities (1 per session) for each facilitator’s first cohort of delivery, and ongoing as needed | 3.5 (0.6) | .92 | ||||

| -Skillful Presentation | IO | 9 | Provide helpful examples to clarify program content | 3.4 (0.4) | .92 | ||

| F | 3.9 (0.6) | .95 | |||||

| S | 3.7 (0.7) | .92 | |||||

| -Skillful Feedback | IO | 7 | Tell parents specifically what they did well | 3.2 (0.3) | .88 | ||

| F | 3.8 (0.6) | .96 | |||||

| S | 3.5 (0.7) | .96 | |||||

| Facilitator Support (Moos, 1981) | |||||||

| IO | 9 | 0–3 | The leader went out of his/her way to help [parents] | 2.4 (0.3) | .96 | ||

| S | 0–3 | 2.4 (0.3) | .89 | ||||

| P | 0–3 | 2.7 (0.5) | .86 | ||||

| Participant Responsiveness | |||||||

| Attendance | F | 1 | 10 sessions | No/Yes | Did this parent attend tonight? | 5.1 (3.8) | -- |

| Perceived Engagement | F | 1 | Session 1 | 0–4 | How interested or enthusiastic do you think this parent is about participating in NBP? | 2.7 (1.1) | -- |

| Expected Participation | F | 1 | Session 1 | 0–4 | How confident are you that this parent will go through the entire program? | 2.7 (1.2) | -- |

| Group Cohesiveness (Moos, 1981) | |||||||

| IO | 9 | 0–3 | There is a feeling of unity or cohesion in the group | 2.4 (0.4) | .97 | ||

| F | 0–3 | 2.1 (0.4) | .85 | ||||

| S | 0–3 | 2.1 (0.3) | .90 | ||||

| P | 0–3 | 2.3 (0.5) | .85 | ||||

| Home Practice (Berkel et al., 2016; Schoenfelder et al., 2012): | |||||||

| -Attempts (%) | P (entered by F) | 1 | Each skill assigned each week (# of skills ranged from 1–6) | No/Yes | Based on what you know from the session and/or the worksheet, did this parent do Family Fun Time this past week? | 58% (43%) | -- |

| -Fidelity (%) | P (entered by F) | Depends on the skill assigned | The first two times each skill was assigned | Checklist | Did the parent plan Family Fun Time in advance? | 47% (36%) | -- |

| -Efficacy | P (entered by F) | 1 | Each skill assigned each week (# of skills ranged from 1–6) | 1–5 | How did the parent say Family Fun Time went for each family member? | 3.4 (0.4) | -- |

| -Competence | F | 1 | Each skill assigned each week (# of skills ranged from 1–6) | 1–5 | How do you think the parent did on Family Fun Time this week? | 3.2 (0.5) | -- |

Note. IO: Independent Observer; F: Facilitator; S: Supervisor; P: Parent

Figure 2.

Theoretical Implementation Cascade Model for Evidence-Based Parenting Programs

Facilitator delivery of NBP was assessed using a multi-informant, multi-method design with reports from facilitators, supervisors, independent observers (members of the research team), and parents (see Table 1). Fidelity (Hi-Fi) items were created based on instructions in the manual and scored on a 3-point scale. We asked open-ended questions about additive adaptations to each activity. The quality measure (Hi-Q) was developed using existing measures (e.g., Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2005) and adapted to fit the processes in each of the activity types in the program (i.e., didactic presentation of new skills, role play practice of new skills, and review of home practice). The Hi-Q has three subscales: Positive Engagement assesses facilitator skill in creating rapport and cohesiveness in the group, Skillful Presentation assesses facilitator skill in presenting the material in a clear and natural way that is relevant for participants’ situations, and Skillful Feedback assesses facilitator skill in providing positive and constructive feedback on participants’ use of program skills. Parallel items were created for each reporter, with facilitators self-reporting on their delivery after each session and supervisors rating one activity per session using video recordings. For independent observations, we transcribed all program activities and coded them in NVivo qualitative data analysis software. This process added a level of transparency to the coding; one can go back to the raw data and corroborate the codes, making it ideal for establishing and maintaining interrater reliability. To avoid halo effects, where a rating on one dimension is biased by positive or negative ratings on another dimension (Hogue, Liddle, & Rowe, 1996), separate teams of independent raters were employed to code fidelity and quality.

Participant responsiveness indicators (i.e., attendance, in-session participation, and home practice) were also assessed via a multi-informant design. Multiple indicators of home practice were assessed because of its primary theoretical importance in NBP, as described above (Berkel et al., 2016). Using home practice worksheets, participants reported the following information: whether they attempted the assigned skill in the past week (home practice attempts), the extent to which they followed program guidelines for each skill (home practice fidelity), and each family member’s perceptions of how the skill went (home practice efficacy). These worksheets were used for both research and clinical purposes (i.e., to guide facilitators’ troubleshooting efforts with families). Facilitators transferred participant responses to the online system and returned worksheets to participants with encouragement and suggestions. Based on the worksheets and discussions with parents during the weekly home practice review, facilitators rated participants’ competence in the use of the skills over the previous week (home practice competence).

Implementation Measures

Descriptives.

Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for each implementation measure. Consistent with previous research (Dusenbury, Brannigan, Hansen, Walsh, & Falco, 2005; Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2009), facilitators and supervisors reported higher levels of fidelity than independent observers. It is important to note that the fidelity items assessed content at a very granular level (i.e., an item was created for each instruction in the manual). This approach is better than a macro-level approach for capturing variability and identifying areas to intervene. However, this level of detail may have been difficult for facilitators who were responding to items from memory, rather than reviewing their recording. Average facilitator and supervisor ratings of quality were closer to the midpoint, possibly due to instructions to rate a typical activity at the midpoint and reserve the high end of the scale for activities that they felt could be used in future trainings. Raters were relatively consistent in their assessment of facilitator support and group cohesiveness (Moos, 1981). Parents attended on average half of the sessions, a number that includes parents who never attended, and attempted the assignments 58% of the time. This percent excludes situations where data were missing, e.g., if a parent attended a session when a skill was assigned, but did not return to report on home practice. Those who completed the home practice implemented roughly half of the instructions for each skill. On average, parents’ ratings of home practice efficacy and facilitators’ ratings of home practice competence were at the midpoint of the scales.

Validation.

An important next step was to assess the predictive validity of the implementation measures. Criterion measures were identified using the implementation cascade model (Berkel et al., 2011). Theoretically, we expected that home practice quality would lead to improvements in parenting and child adjustment. We found that average home practice efficacy and competence each predicted improvements in multiple domains of parenting, above and beyond the influence of attendance (Berkel et al., 2016). Home practice competence was also associated with improvements in child mental health symptoms (Berkel et al., 2017). Because home practice competence is relatively feasible to collect, it may be a useful measure to include when monitoring implementation in community settings. Emerging evidence supports the predictive validity of independent ratings of facilitator delivery (Berkel et al., 2017). Fidelity was positively associated with home practice competence, and quality, in particular the positive engagement subscale, was indirectly associated with home practice competence through its influence on attendance.

Towards Feasible Assessment of Facilitator Delivery

Cost of obtaining objective ratings of implementation.

Despite the demonstrated validity of independent ratings of facilitators’ quality and fidelity, multiple logistical issues can create challenges for providing real-time feedback to facilitators (Schoenwald, 2011). Because mechanisms to reimburse supervision time in community agencies are lacking, supervision typically consists of discussions about administrative issues, and sometimes includes problem solving for difficult cases (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006). Supervisors rarely have the opportunity to conduct observations of direct services. An expectation that supervisors would be trained to a minimum level of interrater reliability and participate in ongoing calibration meetings - as is common in a research context - would be even more challenging. Even in research trials, independent observations are often limited to a small sample of sessions (e.g., 10–20%), suggesting that substantial information may be missed in implementation coding. Moreover, a long gap can occur between a facilitator’s delivery of a session and receiving feedback from independent observations, meaning that behaviors inconsistent with the program can become habitual in the interim. This process clearly does not fulfill the delivery system’s need for timely feedback.

Use of machine learning as a practical approach to monitoring implementation.

Technological developments using computational linguistics and machine learning offer an opportunity to assess fidelity and quality in a low burden, timely, and comprehensive manner. Automated ratings of written or spoken language have been used in private sectors and education for three decades (Shermis, Burstein, Elliot, Miel, & Foltz, 2015), and efforts are currently underway to apply these methods to monitor the delivery of EBPs. The overarching theme of computational methods is to exploit linguistic and non-linguistic features that are evidence of fidelity and quality. For example, Atkins, Narayanan, and colleagues have applied automated methods to assess linguistically-based indicators of the quality of Motivational Interviewing (MI) in individual substance abuse therapy (Atkins, Steyvers, Imel, & Smyth, 2014; Can et al., 2016; Imel et al., 2014; Xiao, Imel, Georgiou, Atkins, & Narayanan, 2015). They have found high degrees of sensitivity and specificity (.63-.86) between human ratings and text classification of linguistically based quality indicators, including open-ended questions (e.g., “how do you…?”), reflections (e.g., “it sounds like…”), and empathy (e.g., “it must be hard to…”). Gallo and colleagues (2015, 2016; 2015) have developed computational linguistics methods for measuring quality in parenting EBPs, including strategies to build alliance (kappa with human ratings = .83) and support for parent self-efficacy in implementing program skills (percent agreement with human coders = 94%). Using audio recordings, they have also developed a machine classifier based on automatically extracted speech features such as pitch to assess emotion in spoken speech (Gallo et al., under review). The emotional choices of a program provider can be an indicator of facilitator frustration or negative affect. Validated automated methods to assess indicators of quality and fidelity could reduce the cost of assessment, improve the reliability of assessments, and enable a rapid feedback system to support sustained, high quality implementation when programs are delivered at scale in community settings.

Towards Feasible Assessment of Participant Responsiveness

The second overarching domain of implementation is participant responsiveness (Figure 2), which includes multiple indicators of participants’ engagement with the program (Schoenfelder et al., 2012). The automated coding methods described above to assess facilitators’ delivery may also be applied to participants’ speech to detect their engagement. For example, resistance to program content expressed during the session is to a large extent conveyed verbally and, as a result, can be measured through text mining (Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). Acoustic features in spoken speech can be utilized to detect participant emotions, such as hope or frustration (Gallo, et al., under review).

We found that the quality of parents’ home practice is highly predictive of improvements in parenting and child adjustment (Berkel et al., 2017; Berkel et al., 2016). However, an inefficient paper-and-pencil data collection system led to substantial amounts of missing data. For example, for one skill, 42% of the home practice fidelity scores were missing. Missing data are clearly undesirable from a research perspective, but more importantly are clinically problematic in that they limit facilitators’ ability to help parents solve problems. Engaging in home practice and obtaining complete home practice data depend on several conditions: 1) the participants attending the sessions in which the skill was taught and assigned and understanding the material; 2) the participants having the home practice worksheet on hand to record their practice; 3) the participants attending the session when the home practice is due; 4) the participants remembering to bring the worksheet back to the facilitator; and 5) the facilitator manually entering the data into a database.

Optimization of each of these steps through technology could facilitate both engagement in skills practice and complete data collection, which would improve facilitators’ troubleshooting with the participants and supervisors’ feedback to the facilitators. For example, Condition 1 refers to design features of the intervention itself. Like most parenting programs, NBP is delivered via in-person groups and therefore requires attendance for participants to receive information about the skill and assignments to try the skill. The program delivery system could become more robust by building in strategies to ensure that participants received this information irrespective of whether they were able attend the session. For example, the data collection system might track absences and arrange for a makeup video in advance of the following session to enable time to practice skills prior to the next session. Reminders and online parent forums could also promote engagement with home practice.

Conditions 2–5 refer to the logistics of collecting and uploading data. Parents complete the home practice worksheet and facilitators enter data extracted from the completed worksheets. While participants and facilitators report that worksheets are extremely useful, they often get lost or forgotten. Further, it is burdensome for facilitators to enter participants’ scores into a data system before returning them with comments to the parents. An online system in which participants directly enter responses could have the benefit of 1) serving as a reminder for participants to practice the skills, 2) being more engaging and interactive than a hard copy worksheet, 3) eliminating the requirement of attendance for the participants to update the facilitator how well they are doing with the skills, 4) reducing facilitator burden, 5) reducing the chance of error in transferring information from the worksheet to the database, and 6) giving the facilitator advanced notice when a parent has trouble so that they can identify timely solutions.

Integrated Implementation Monitoring and Feedback System: A Vision for the Future

We describe a proposed technology-based implementation monitoring and feedback system to sustain implementation at scale. As shown in Figure 3, we suggest two types of inputs: automated coding to collect in-session information and online data entry for attendance and home practice. Starting on the left side of the diagram, speech processing tools could be used to identify facilitators’ and participants’ speech in audio-recordings of the session. Text mining could be used to compare the content spoken by the facilitator to that prescribed in the manual, an indication of fidelity. The content and affect of the facilitators’ and participants’ speech, captured through text mining and emotion detection, could serve as indicators of quality and participants’ active in-session participation. Weekly reports summarizing this information could be generated and sent to facilitators and supervisors to identify areas for improvement. If any scores were below an acceptable threshold, the system could alert the supervisor to review specific segments of the recording that appeared to be problematic.

Figure 3.

Dynamic Implementation Monitoring and Feedback System Using Empirically Supported Indicators of Implementation

The right side of Figure 3 describes the collection of attendance and home practice data. There is growing interest in the potential for using mobile technology to collect data on home practice (e.g., Chacko, Isham, Cleek, & McKay, 2016). We propose a system in which participants enter data on their home practice attempts, fidelity, and efficacy. To encourage participants’ use of this system, it must be of value to families, which may be achieved by building in entertainment and social interaction (e.g., allowing children to customize avatars; taking “Family Fun Time” selfies), as well as providing support for their skill use (e.g., instructional videos and peer support). Immediately after each session, facilitators would enter attendance and their evaluations of participants’ competence in doing home practice. A dashboard would exist so facilitators would provide real time access to the data. Reports for facilitators and supervisors would be generated for ongoing supervision. Finally, aggregated reports compiling information from both sources would provide feedback to the program developers and systems involved in program delivery (e.g., in the case of NBP, the court and social service agencies) on ways to improve future iterations of the program. These reports can be included in funding requests to support sustainable program delivery.

Potential Challenges and Future Directions

We described how technology could be used in the creation of a monitoring and feedback system to support implementation when parenting EBPs are translated to community settings. A theoretical implementation cascade model (Berkel et al., 2017) informed the development of a comprehensive implementation battery in an effectiveness trial of NBP, in partnership with family courts and community mental health agencies. While we have found support for these measures as important predictors of program outcomes, the measurement methods were burdensome. The collection of observational ratings of fidelity and quality was a monumental task, taking roughly four years to code all program sessions. A comprehensive system that makes use of automated coding and mobile applications may be the key for providing timely feedback to facilitators and supervisors for quality improvement.

With any new tool, a thorough understanding of the service delivery context will help anticipate and overcome potential challenges to its use. In terms of automated systems for in-session monitoring, one potential constraint may be limited availability of recording devices, especially for agencies that do not currently use sessions recordings for supervision. Privacy issues are of utmost importance for clinical settings and secure systems will be required for uploading and storing data. Consideration must be given to the added cost associated with the technology and the return on investment for stakeholders.

We currently lack evidence to determine how facilitators, supervisors, and participants may respond to a technology-based system for implementation monitoring. We would only expect a system to improve delivery to the extent that key stakeholders trusted and valued the information provided and the real or perceived source of the message (Mohr, Cuijpers, & Lehman, 2011). Some therapists may be skeptical that machines can capture the clinical skills they use to engage resistant participants. On the other hand, one program facilitator mentioned that she would be less anxious and feel less judgment if she were rated by a machine as opposed to by a human observer. A fundamental principle of developing computational methods is that an individual assisted by computational tools can perform better than an individual without such tools (Friedman, 2009). Personal characteristics, such as years of experience or comfort with technology, may influence acceptability and how informative such technology is for the user. A hybrid approach in which supervisors reviewed sections of the sessions flagged by the system and provided feedback based on their clinical expertise may be more palatable for some facilitators than receiving information directly from a dashboard (Brown et al., 2013). There are many indicators of fidelity, quality, and responsiveness that could be displayed on a dashboard, but we do not know which of these users find most informative or which may be most responsive to intervention. If recording sessions is not feasible, we do not know whether other indicators (e.g., home practice) might be sufficient to monitor implementation. To answer these questions, future research should 1) include end users and other stakeholders to fully understand the service delivery context, including needs, preferences, and potential barriers to use; 2) test disaggregated components of the system to empirically identify core components and explore potential moderators to optimize the system; and 3) consider the cost of each component of the system to determine relative cost-benefit.

A final potential concern is that the use of technology in implementation may have the inadvertent result of perpetuating inequities for disadvantaged communities that may have less access to and comfort with technology. While emerging evidence suggests that minority communities may be more receptive to technology-based tools than traditional approaches (Murry, Berkel, & Liu, 2018), more research is needed in this area. Furthermore, for scientific equity it is important to develop and test technology in ways that do not unfairly benefit one portion of the population over another (Perrino et al., 2015). For example, it is important to think about ways to ensure a system like this meets the needs of both English and non-English speakers alike. Addressing these concerns will be necessary to develop a robust system to support the high-quality implementation of evidence-based programs in community settings and promote their public health impact.

Acknowledgments

Funding. Support for the development of this manuscript was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse: R01DA026874 (Sandler), R01DA033991 (Berkel & Mauricio), and competitive funding from the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (Ce-PIM), P30-DA027828 (Brown/Berkel), and Diversity Supplement R01DA033991–03S1 (Berkel/Gallo).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. Sandler is a developer of the NBP and has an LLC that trains facilitators to deliver the program. Remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research Involving Human Participants. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Arizona State University’s IRB and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Reference

- Aarons GA, & Sawitzky AC (2006). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 3, 289–301. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Steyvers M, Imel ZE, & Smyth P (2014). Scaling up the evaluation of psychotherapy: Evaluating motivational interviewing fidelity via statistical text classification. Implementation Science, 9, 49, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Gallo CG, & Brown CH (2018). The cascading effects of multiple dimensions of implementation on program outcomes: A test of a theoretical model. Prevention Science, 19, 6, 782–94. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0855-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, & Sandler IN (2011). Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12, 1, 23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, Mauricio AM, & Jones S (2018). “Home practice is the program:” Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 19, 5, 663–73. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Mohr DC, Gallo CG, Mader C, Palinkas L, Wingood G, Prado G, Kellam SG, Pantin H, Poduska J, Gibbons R, McManus J, Ogihara M, Valente T, Wulczyn F, Czaja S, Sutcliffe G, Villamar J, & Jacobs C (2013). A computational future for preventing HIV in minority communities: How advanced technology can improve implementation of effective programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63, Supp 1, S72–S84. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829372bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can D, Marín RA, Georgiou PG, Imel ZE, Atkins DC, & Narayanan SS (2016). “It sounds like...”: A natural language processing approach to detecting counselor reflections in motivational interviewing. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 3, 343–50. doi: 10.1037/cou0000111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Isham A, Cleek AF, & McKay MM (2016). Using mobile health technology to improve behavioral skill implementation through homework in evidence-based parenting intervention for disruptive behavior disorders in youth: Study protocol for intervention development and evaluation. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 2, 57. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0097-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, & Stange KC (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J, & DuPre E (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury LA, Brannigan R, Hansen WB, Walsh J, & Falco M (2005). Quality of implementation: Developing measures crucial to understanding the diffusion of preventive interventions. Health Education Research, 20, 308–313. 10.1093/her/cyg134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatc MS., Patterso GR., & DeGarm DS. (2005). Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy, 36, 3–13. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80049-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman CP (2009). A “fundamental theorem” of biomedical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 16, 169–170. 10.1197/jamia.M3092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Berkel C, Sandler IN, & Brown CH (2015). Improving implementation of behavioral interventions by monitoring quality of delivery in speech Paper presented at the annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination & Implementation, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Berkel C, Sandler IN, & Brown CH (2016). Developing computer-based methods for assessing quality of implementation in parent-training behavioral interventions Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Li Y, Berkel C, Mehrotra S, Liu L, Benbow N, & Brown CH (under review). Recognizing emotion in speech for assessing the implementing behavioral interventions. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Pantin H, Villamar J, Prado G, Tapia MI, Ogihara M, & Brown CH (2015). Blending qualitative and computational linguistics methods for fidelity assessment: Experience with the Familias Unidas preventive intervention. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 574–585. 10.1007/s10488-014-0538-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, & Riley WT (2013). Pragmatic measures: What they are and why we need them. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45, 237–243. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman PM, Mahrer NE, Wolchik SA, Porter MM, Jones S, & Sandler IN (2015). Cost-benefit analysis of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Reduction in mental health and justice system service use costs 15 years later. Prevention Science, 16, 586–596. 10.1007/s11121014-0527-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, & Rowe C (1996). Treatment adherence process research in family therapy: A rationale and some practical guidelines. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 33, 332–345. 10.1037/0022-006x.76.4.544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Barco JS, Brown HJ, Baucom BR, Baer JS, Kircher JC, & Atkins DC (2014). The association of therapist empathy and synchrony in vocally encoded arousal. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61, 146–153. 10.1037/a0034943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, & Carroll KM (2009). Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 181–193. 10.1080/10503300802688460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, & Lehman K (2011). Supportive accountability: A model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13, e30 10.2196/jmir.1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R (1981). Group Environment Scale Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Berkel C, & Liu N (2018). The closing digital divide: Delivery modality and family attendance in the Pathways for African American Success (PAAS) program. Prevention Science, 19, 5, 642–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0863-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC/IOM. (2009). Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, D.C.: NRC/IOM. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Beardslee W, Bernal G, Brincks A, Cruden G, Howe G, Murry V, Pantin H, Prado G, Sandler I, & Brown CH (2015). Toward scientific equity for the prevention of depression and depressive symptoms in vulnerable youth. Prevention Science, 16, 642–651. 10.1007/s11121014-0518-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, Moser RP, Henton MD, Proctor EK, Brownson RC, & Glasgow RE (2012). Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implementation Science, 7, 119, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Gunn H, Mazza G, Tein J-Y, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Jones S, & Porter MM (2018). Effects of a program to promote high quality parenting by divorced and separated fathers. Prevention Science, 19, 4, 538–48. 10.1007/s11121-017-0841-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandle IN., Schoenfelde EN., Wolchi SA., & MacKinno DP. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329. 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Jones S, Mauricio AM, Tein J-Y, & Winslow E (2016). Effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program (NBP) for divorcing and separating parents: Translation from an experimental prototype to an evidence-based community service In Israelashvili M & Romano JL (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of International Prevention Science (pp. 81–106). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, & Ayers TS (2012). Responsiveness to the Family Bereavement Program: What predicts responsiveness? What does responsiveness predict? Prevention Science, 14, 545–556. 10.1007/s11121-012-0337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK (2011). It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s… fidelity measurement in the real world. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18, 142–147. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01245.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Landsverk JA, Stevens J, Glisson C, Rolls-Reutz J, & The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2008). A survey of the infrastructure for children’s mental health services: Implications for the implementation of empirically supported treatments (ESTs). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35, 84–97. 10.1007/s10488-007-0147-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, & Southam-Gerow MA (2011). Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research, 38, 32–43. 10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shermis M, Burstein J, Elliot N, Miel S, & Foltz P (2015). Automated writing evaluation: A growing body of knowledge. In MacArthur C, Graham S & Fitzgerald J (Eds.), Handbook of Writing Research. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik S, Sandler I, Weiss L, & Winslow E (2007). New Beginnings: An empirically-based program to help divorced mothers promote resilience in their children In Briesmeister JM & Schaefer CE (Eds.), Handbook of parent training: Helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors (3rd ed., pp. 25–62). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchi SA., Sandle IN., Tei J-Y., Mahre NE., Millsa R., Winslo E., Véle C., Porte M., Luecke LJ., & Ree A. (2013). Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 660–673. 10.1037/a0033235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Coatsworth D, Lengua L, Weiss L, Anderson ER, Greene SM, & Griffin WA (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 68, 843–856. 10.1037/0022-006x.68.5.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B., Ime ZE., Georgio PG., Atkin DC., & Narayana SS. (2015). “Rate my therapist”: Automated detection of empathy in drug and alcohol counseling via speech and language processing. PLoS ONE, 10 10.1371/journal.pone.0143055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]